Introduction

Substantial progress has been made in the standardization of nomenclature for paediatric and congenital cardiac care. Reference Abbott1–Reference Tretter and Jacobs108 In 1936, Maude Abbott, of McGill University in Montréal, Québec, Canada, published her Atlas of Congenital Cardiac Disease, which was the first formal attempt to classify congenital heart disease. Reference Abbott1 The International Paediatric and Congenital Cardiac Code ( IPCCC ) is now utilized worldwide and is the paediatric and congenital cardiac component of the Eleventh Revision of the International Classification of Diseases ( ICD-11 ). Reference Franklin, Béland and Colan105,Reference Lopez, Houyel and Colan106 The most recent publication of the IPCCC was in 2017. Reference Franklin, Béland and Colan105 This manuscript provides an updated 2021 version of the IPCCC , which is now the paediatric and congenital cardiac component of ICD-11 .

Congenital cardiac malformations are the most common types of birth defects. Before the introduction of current diagnostic modalities, such as echocardiography, the estimated incidence of CHD ranged from five to eight per 1000 live births. With improved diagnostic modalities, many more patients with milder forms of CHD can now be identified, so that contemporary estimates of the prevalence of congenital cardiac disease now range from eight to twelve per 1000 live births. 109–Reference Hoffman112 . About one-quarter of neonates and infants with a congenital cardiac defect undergo surgery or catheter-directed intervention in their first year of life. 109 Survival after surgery for congenital heart defects has increased over the past decade, especially for the most complex operations. Reference Jacobs, He and Mayer113 The aetiology of this improvement is obviously multifactorial, but the ability to compare and benchmark risk-stratified and risk-adjusted outcomes at individual programs to national and international aggregate benchmarks has certainly facilitated these improved cardiac surgical outcomes over time. This benchmarking and improvement in quality requires standardization of the nomenclature and classification of paediatric and congenital cardiac disease, as described in this manuscript.

This manuscript presents the latest edition of The International Paediatric and Congenital Cardiac Code ( IPCCC ), which has been integrated into the paediatric and congenital cardiac component of the Eleventh Revision of the International Classification of Diseases ( ICD-11 ). This article will discuss the following topics:

-

The International Paediatric and Congenital Cardiac Code (IPCCC)

-

The Eleventh Revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11)

-

Clinical Nomenclature versus Administrative Nomenclature

This article will then present the following three Tables of IPCCC ICD-11 Nomenclature for Congenital Cardiac Diagnostic Terms in the ICD-11 Foundation

-

Table 1. IPCCC ICD-11 Diagnostic Hierarchy

-

Table 2. IPCCC ICD-11 Definitions

-

Table 3. IPCCC ICD-11 Codes

The version of the IPCCC that was published by ISNPCHD in 2017 Reference Franklin, Béland and Colan105 has evolved and is now updated with the 2021 version published in this manuscript. In the future, ISNPCHD will again publish additional updated versions of IPCCC , as IPCCC continues to evolve.

The International Paediatric and Congenital Cardiac Code (IPCCC)

As already emphasised, the development of classification schemes specific to the congenitally malformed heart began with Maude Abbott’s pioneering work in the early 1900s. Reference Abbott1,Reference Franklin, Béland and Colan105 Her landmark publication in 1936, entitled “Atlas of Congenital Cardiac Disease”, was the first formal attempt to classify the lesions seen when the heart is congenitally malformed. Reference Abbott1,Reference Franklin, Béland and Colan105 It was not until the 1990s that efforts were made to create a truly international system of nomenclature and classification to support paediatric and congenital cardiac care. Prior to these efforts of the 1990s, multiple systems of nomenclature and classification were used at hospitals across the world. These various systems of nomenclature were the basis of internal, national, and even international registries and databases of paediatric and congenital cardiac care. Reference Franklin, Béland and Colan105

Aided by advances in information technology that facilitate the exchange of information, two independent international collaborations began in the 1990s, resulting in the publication of two separate international paediatric and congenital cardiac systems of nomenclature and classification:

-

The European Paediatric Cardiac Code (EPCC) of The Association for European Paediatric and Congenital Cardiology (AEPC) Reference Franklin, Anderson and Daniëls2,3

-

The nomenclature system of the International Congenital Heart Surgery Nomenclature and Database Project of The Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) in North America, The European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS), and The European Congenital Heart Defects Database of The European Congenital Heart Surgeons Foundation (ECHSF) – (renamed The European Congenital Heart Surgeons Association [ECHSA] in 2003). Reference Mavroudis and Jacobs4–Reference Joffs, Sade, Mavroudis and Jacobs37

During the 1990s, both ECHSF and STS created databases to assess the outcomes of congenital cardiac surgery. Beginning in 1998, EACTS, ECHSA, and STS collaborated to create the International Congenital Heart Surgery Nomenclature and Database Project. As a result of this project, by 2000, a common nomenclature, along with a common core minimal dataset, were adopted by EACTS, ECHSA, and STS, and published in The Annals of Thoracic Surgery as a 372-page free standing Supplement. Reference Mavroudis and Jacobs4–Reference Joffs, Sade, Mavroudis and Jacobs37 In parallel, in 1996, the AEPC created a Coding Committee to produce a set of diagnostic and procedural codes that would be acceptable and adopted within both the European paediatric cardiology and European paediatric cardiac surgical communities. As a result of this project, in 2000, the EPCC was published in Cardiology in the Young as a 146-page free standing Supplement. Reference Franklin, Anderson and Daniëls2,3

Both the EPCC and the International Congenital Heart Surgery Nomenclature and Database Project included a comprehensive Long List, with thousands of terms, and a Short List designed to be used as part of a minimum data set for multi-institutional registries and databases. Both Long Lists mapped fully to their respective Short Lists. The nearly simultaneous publication of these two complementary systems of nomenclature led to the problematic situation of having two systems of nomenclature that were to be widely adopted, with the potential risk of duplicate or inaccurate coding within institutions, as well as the potential problem of invalidating multicentric projects owing to confusion between the two systems. Reference Franklin, Béland and Colan105

Hence, on Friday, October 6, 2000, in Frankfurt, Germany, during the meeting of ECHSF prior to the 14th Annual Meeting of EACTS, representatives of the involved Societies met and established The International Nomenclature Committee for Paediatric and Congenital Heart Disease , which was to include representatives of the four societies (AEPC, STS, ECHSF, and EACTS), as well as representatives from the remaining continents of the world – Africa, Asia, Australia (Oceania), and South America. Reference Franklin, Jacobs, Tchervenkov and Béland41–Reference Franklin, Jacobs, Tchervenkov and Béland45,Reference Béland, Franklin and Jacobs47,Reference Franklin, Béland and Colan105 Over four years later, in January, 2005, The International Nomenclature Committee for Pediatric and Congenital Heart Disease was constituted and legally incorporated as The International Society for Nomenclature of Paediatric and Congenital Heart Disease ( ISNPCHD ).

At the meeting in Frankfurt in 2000, an agreement was reached to collaborate and produce a reconciliatory bidirectional map between the two systems of nomenclature. The feasibility of this project was established by the creation of a rule-based bidirectional crossmap between the two Short Lists, using the six-digit coding system already established within the EPCC as the common link between the two nomenclature lexicons. This bidirectional crossmap between the two Short Lists was created and published by The International Working Group for Mapping and Coding of Nomenclatures for Pediatric and Congenital Heart Disease , also known for short as the Nomenclature Working Group ( NWG ), which was the original committee of The International Nomenclature Committee for Paediatric and Congenital Heart Disease and the subsequent ISNPCHD Reference Béland, Jacobs, Tchervenkov and Franklin44,Reference Franklin, Jacobs, Tchervenkov and Béland45,Reference Béland, Franklin and Jacobs47

Over the next 8 years, the NWG met 10 times, over a combined period of 47 days, to achieve the main goal of crossmapping the two comprehensive Long Lists to create the IPCCC, which has two dominant versions Reference Franklin, Béland and Colan105 :

-

The version of the IPCCC derived from the European Paediatric Cardiac Code of AEPC

-

The version of the IPCCC derived from the International Congenital Heart Surgery Nomenclature and Database Project of EACTS, ECHSA, and STS.

These two versions of the IPCCC are crossmapped to each other by means of the six-digit coding system Reference Franklin, Jacobs and Krogmann63 and have the following abbreviated short names:

-

EACTS-STS derived version of the IPCCC

-

AEPC derived version of the IPCCC

The NWG therefore crossmapped the nomenclature of the International Congenital Heart Surgery Nomenclature and Database Project of EACTS, ECHSA, and STS with the EPCC of AEPC, and thus created the IPCCC, Reference Franklin, Jacobs and Krogmann63 which is available for free download from the internet at [https://www.IPCCC.net]. Additional systems of nomenclature, for paediatric cardiology and cardiac surgery, which were mapped to the common six-digit code spine, include the Boston-based Fyler codes, and the Canadian nomenclature system. There is also mapping to the ninth and tenth revisions of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-9, ICD-10), usually in a many to one fashion, given the limitations of these earlier versions of ICD.

Most international databases of patients with paediatric and congenital cardiac disease now use the IPCCC as their foundation. This common nomenclature, the IPCCC, and the common minimum database data set created by the International Congenital Heart Surgery Nomenclature and Database Project, are now utilized by multiple databases and registries of paediatric and congenital cardiac care across the world. The following databases all use the EACTS-STS derived version of the IPCCC:

-

The Society of Thoracic Surgeons Congenital Heart Surgery Database (STS CHSD), Reference Maruszewski, Lacour-Gayet and Elliott39,Reference Gaynor, Jacobs and Jacobs40,Reference Kurosawa, Gaynor and Jacobs46

-

The European Congenital Heart Surgeons Association Congenital Heart Surgery Database (ECHSA CHSD), Reference Maruszewski, Lacour-Gayet and Elliott39,Reference Gaynor, Jacobs and Jacobs40,Reference Kurosawa, Gaynor and Jacobs46

-

The Japan Congenital Cardiovascular Surgery Database (JCCVSD), Reference Maruszewski, Lacour-Gayet and Elliott39,Reference Gaynor, Jacobs and Jacobs40,Reference Kurosawa, Gaynor and Jacobs46 and

-

The World Database for Pediatric and Congenital Heart Surgery (WDPCHS). Reference St Louis, Kurosawa and Jonas114

Several national and institutional databases in Europe use the AEPC derived version of the IPCCC for collection of data, including:

-

Germany,

-

the Netherlands, and

-

the United Kingdom and Republic of Ireland National Congenital Heart Disease Audit.

For all terms within the two versions of the IPCCC, a unique six-digit code corresponds to a single entity, whether it be a morphological phenotype, procedure, symptom, or genetic syndrome. Reference Franklin, Béland and Colan105 The mapped terms in each of the two versions are synonymous. Reference Franklin, Béland and Colan105 By 2013, there were 12,168 terms in the IPCCC Long List version derived from the European Paediatric Cardiac Code, and 17,176 terms in the IPCCC Long List version derived from the International Congenital Heart Surgery and Nomenclature Database Project. These Long Lists include hundreds of qualifiers, some specific, such as anatomical sites, and others generic, such as gradings of severity.

It is primarily the Short Lists, rather than the Long Lists, of the two crossmapped versions of the IPCCC that have been used for analyses of multi-institutional and international outcomes following operations and procedures for patients with congenitally malformed hearts. Over a million patients are now coded with the IPCCC in registries worldwide. Reference Franklin, Béland and Colan105 Both versions of the IPCCC Short Lists have been used to develop empirical systems for the adjustment of risk following surgical procedures, based on the operation type and comorbidities, for the purposes of quality assurance and quality improvement. Reference O’Brien, Clarke and Jacobs115–Reference Jacobs, O’Brien and Hill119 Both risk adjustment systems depend upon the IPCCC for all variables, to ensure a common nomenclature between institutions submitting data, and both perform better than the systems based on the subjective assessment of risk. Reference Franklin, Béland and Colan105

The history of ISNPCHD and the development of IPCCC have been previously published. Reference Béland, Jacobs, Tchervenkov and Franklin44,Reference Franklin, Jacobs, Tchervenkov and Béland45,Reference Béland, Franklin and Jacobs47,Reference Franklin, Béland and Colan105,Reference Cohen and Jacobs107,Reference Tretter and Jacobs108 The International Working Group for Mapping and Coding of Nomenclature for Paediatric and Congenital Heart Disease was also known as the Nomenclature Working Group or NWG and was the first committee of The International Society for Nomenclature of Paediatric and Congenital Heart Disease ( ISNPCHD ). The initial 12 members of Nomenclature Working Group represented multiple subspecialties and continents:

-

Vera Aiello, University of São Paulo Medical School, São Paulo, Brazil

-

Marie J. Béland, The Montreal Children’s Hospital, Montréal, Québec, Canada

-

Steven Colan, Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, United States of America

-

Rodney C. G. Franklin, Royal Brompton & Harefield Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, London, United Kingdom

-

J. William Gaynor, The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States of America

-

Jeffrey P. Jacobs, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida, United States of America

-

Otto N. Krogmann, Heart Center Duisburg, Duisburg, Germany

-

Hiromi Kurosawa, Tokyo Women’s Medical University, Tokyo, Japan

-

Bohdan J. Maruszewski, Children’s Memorial Health Institute, Warsaw, Poland

-

Giovanni Stellin, Universita di Padova, Italy

-

Christo I. Tchervenkov, The Montreal Children’s Hospital, Montréal, Québec, Canada

-

Paul Weinberg, The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States of America

The Presidents of The International Society for Nomenclature of Paediatric and Congenital Heart Disease ( ISNPCHD ) are listed below, along with the terms of their Presidency:

-

Martin J. Elliott (2000–2009)

-

Christo I. Tchervenkov (2009–2013)

-

Rodney C. G. Franklin (2013–2017)

-

Jeffrey P. Jacobs (2017–2021)

-

Steven D. Colan (2021–2025)

Although both the Short Lists and the comprehensive Long Lists of each version of IPCCC have been crossmapped, the two Short Lists emanating from their respective Long-List versions are not the same in terms of structure or content. Reference Franklin, Béland and Colan105 ISNPCHD recognized this disparity, and believed that the creation of a congenital cardiac subset within ICD-11 would accomplish several goals:

-

help resolve the differences between the Short List of the EACTS-STS derived version of the IPCCC and the Short List of the AEPC derived version of the IPCCC

-

present a single common comprehensive and hierarchical Short List of diagnostic terms that could serve all communities involved with paediatric and congenital cardiac care

-

harmonize the administrative nomenclature for paediatric and congenital cardiac care with the clinical nomenclature for paediatric and congenital cardiac care.

Hence, ISNPCHD created, organized, and defined the terms of IPCCC in order to standardize nomenclature for paediatric and congenital cardiac care and promote accurate coding, sharing of information, and analysis of data. Reference Franklin, Jacobs, Tchervenkov and Béland41–Reference Franklin, Jacobs, Tchervenkov and Béland45,Reference Béland, Franklin and Jacobs47,Reference Franklin, Béland and Colan105 ISNPCHD believed from the start that the concept of “illustration” of the terms would be very important to advance these goals. Reference Giroud, Aiello, Spicer and Anderson87–Reference Aiello, Spicer, Jacobs, Giroud and Anderson90,Reference Spicer, Jacobs, Giroud, Anderson and Aiello93,Reference Jacobs, Giroud, Anderson, Aiello and Spicer94,Reference Seslar, Shepard and Giroud102 Concurrent with its involvement in developing ICD-11, as described in detail below, ISNPCHD began creating the IPCCC ICD-11 Congenital Heart Atlas to illustrate the terms listed in the “Structural developmental anomaly of heart or great vessels” section of ICD-11. In addition to the terms, definitions, and data about coding that is published in ICD-11, the IPCCC ICD-11 Congenital Heart Atlas is currently being built to contain drawings, photographs of anatomical specimens, images and videos from various imaging modalities, and intraoperative photographs and videos, all designed to help health care professionals better select the correct designation for the cardiac phenotypes listed in ICD-11. The IPCCC ICD-11 Congenital Heart Atlas will, of course, also fulfill multiple educational purposes. The IPCCC ICD-11 Congenital Heart Atlas will be freely accessible on the ISNPCHD website: [https://www.IPCCC.net]. The IPCCC ICD-11 Congenital Heart Atlas will also be freely accessible via hyperlinks from:

-

Heart University [https://www.heartuniversity.org/], and

-

The World University for Pediatric and Congenital Heart Surgery [https://www.wupchs.education]

The Eleventh Revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11)

The history of The International Classification of Diseases ( ICD ) dates back to the late 1800s (Figure 1):

-

In 1891, the International Statistical Institute commissioned a committee chaired by Jacques Bertillon (1851–1922), Chief of Statistical Services of the City of Paris, to create what became the Bertillon [International] Classification of Causes of Death, with associated sequential numeric codes. Reference Franklin, Béland and Colan105 Over the following decades, this classification scheme was adopted by many countries in the Americas and Europe, with conferences for revision occurring roughly every 10 years to update the system, which became known as The International Classification of Diseases ( ICD ).

-

In 1893, Bertillon presented the (International) Classification of Causes of Death at the meeting of the International Statistical Institute in Chicago, where it was adopted by several cities and countries.

-

In 1898, the American Public Health Association recommended its adoption in North America, and that the classification be revised every 10 years.

-

In 1900, the First International Conference to revise the Bertillon Classification of Causes of Death was held in Paris.

-

In 1909, non-fatal diseases, in other words, morbidity, were added.

-

From 1948 until now, the World Health Organization (WHO) has promoted and managed ICD, starting in 1948 with the sixth revision of the International Classification of Diseases, Injuries and Causes of Death.

Figure 1. The International Classification of Diseases (ICD). This bar chart documents the time interval between each Revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD), 1900–2021. The horizontal lower bar indicates the number of terms related to congenital heart disease (CHD) listed in each ICD version.

According to WHO , “ICD is the foundation for the identification of health trends and statistics globally, and the international standard for reporting diseases and health conditions. It is the diagnostic classification standard for all clinical and research purposes. ICD defines the universe of diseases, disorders, injuries and other related health conditions, listed in a comprehensive, hierarchical fashion” [https://www.who.int/standards/classifications/classification-of-diseases]. The ICD-11 development mission was “To produce an international disease classification that is ready for electronic health records that will serve as a standard for scientific comparability and communication”. Reference Franklin, Béland and Colan105 ICD-11 was officially launched on-line by the WHO in June 2018 and endorsed by the World Health Assembly on 25 May 2019. The WHO states that ICD-11 is to be “The global standard for health data, clinical documentation, and statistical aggregation”, that it is “scientifically up-to-date and designed for use in the digital world with state-of-the art technology to reduce the costs of training and implementation”, and that its “multilingual design facilitates global use” [https://www.who.int/classifications/classification-of-diseases]. The purpose of ICD-11 “is to allow the systematic recording, analysis, interpretation, and comparison of mortality and morbidity data collected in different countries or areas and at different times”. Reference Franklin, Béland and Colan105 The ICD-11 project began in earnest in 2007. Importantly, ICD-11 incorporates textual definitions. With the creation of ICD-11, for the first time, the revision process moved away from reliance on large meetings of national delegations of health statisticians, wherein those who voiced their opinion strongest would dominate the content of the paper-based output – “decibel” diplomacy. In contrast, the ICD-11 revision process is dependent upon international expert clinicians, with digital curation, the incorporation of wide peer review, and extensive field testing. “ICD-11 has been adopted by the Seventy-second World Health Assembly in May 2019 and comes into effect on 1 January 2022” [https://www.who.int/standards/classifications/classification-of-diseases].

The task of creating ICD-11 was divided into content specific Topic Advisory Groups, with related Working Groups led by Managing Editors and chaired by specialist clinicians with an intentionally wide geographic spread. From 2009 through to 2016, the Managing Editor coordinated a series of meetings, some face-to-face, but mostly teleconferences, beginning with the hierarchical structure and terms within ICD-10, and initially producing an evolving alpha draft. In 2012, a beta draft was published online [https://icd.who.int/dev11/f/en], coinciding with the authoring process moving to a web-based platform for its entire content. Reference Franklin, Béland and Colan105 The tool allows online global peer review and submission of comments by both the authors and worldwide interested parties in the field-testing stage.

From the start, clinicians involved in the Topic Advisory Groups have been encouraged to enlist the advice of specialist Societies to aid the process, thus ensuring that the content was both up-to-date and had Societal endorsement. This process has resulted in a huge increase in the number of individual terms within ICD-11, with secondary expansion of the hierarchical structure when compared with ICD-10.

In collaboration with WHO , ISNPCHD developed the paediatric and congenital cardiac nomenclature that is now within the eleventh version of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11). Reference Franklin, Béland and Colan105 This unification of IPCCC and ICD-11 is the IPCCC ICD-11 Nomenclature and is the first time that the clinical nomenclature for paediatric and congenital cardiac care and the administrative nomenclature for paediatric and congenital cardiac care have been harmonized. Reference Franklin, Béland and Colan105 The resultant congenital cardiac component of ICD-11 was increased from 29 CHD diagnostic terms codes in ICD-9 and 73 CHD diagnostic terms in ICD-10 to 318 codes submitted by ISNPCHD through 2018 for incorporation into ICD-11. Reference Franklin, Béland and Colan105 After these 318 terms were incorporated into ICD-11 in 2018, the WHO ICD-11 team added an additional 49 terms, some of which are acceptable legacy terms from ICD-10, while others provide greater granularity than the ISNPCHD thought was originally acceptable, such as individual codes for the various types of isolated branches of the aortic arch or branches of the aortic arch having an aberrant origin. Thus, the total number of paediatric and congenital cardiac terms in ICD-11 is now 367. (Tables 1–3). Populating ICD-11 by the content-specific Topic Advisory Groups was not always without controversy, with at times, for example, heated and prolonged discussions between the Rare Diseases Topic Advisory Group and several Internal Medicine Topic Advisory Workings Groups, including the Cardiovascular Working Group, over the hierarchy and content to be included or excluded. Tables 1 and 2 present the diagnostic hierarchy (Table 1) and definitions (Table 2) of the 318 codes submitted by ISNPCHD to compose the IPCCC ICD-11 Nomenclature, as well as the additional 49 scientifically correct or legacy terms added by the WHO ICD-11 team. As these additional 49 entities have now been added to IPCCC, ISNPCHD has provided the needed definitions for these terms (as presented in Table 2). Other legacy and scientifically incorrect terms inserted into the ICD-11 Foundation by the WHO ICD-11 team were judged by ISNPCHD to be obsolete or meaningless. These obsolete or meaningless terms, such as “Transposition of the aorta” and “Accessory heart”, have been highlighted to WHO and have been made ‘obsolete’ within the system, meaning that these terms are retained for legacy purposes but will not be visible nor easily searchable. Tables 1–3, therefore, present the 367 terms that are part of IPCCC and also the paediatric and congenital cardiac component of ICD-11. Consequently, IPCCC and ICD-11 are a system of nomenclature that will, for the first time ever, harmonize the administrative nomenclature for paediatric and congenital cardiac care with the clinical nomenclature for paediatric and congenital cardiac care. This important goal will be achieved with the implementation of ICD-11.

Another of the aims of WHO for ICD-11 is to have the entirety of ICD-11 translated into different languages. The achievement of this objective will enhance the global uptake and utility of ICD-11 for international comparisons of outcomes and initiatives of quality improvement. Currently WHO list 22 languages which are at least partially complete. Knowing this fact, members of ISNPCHD have already translated the IPCCC ICD-11 Nomenclature into French Reference Béland, Harris, Marelli, Houyel, Bailliard and Dallaire120 and Portuguese. Reference Aiello and Mattos121 ISNPCHD has submitted the French version into ICD-11 via their translation tool platform. Unfortunately, it has become apparent that much of the translation work has been delegated by WHO to national governmental designated translation teams, without input from clinicians. This suboptimal strategy has led to some clinically unusable translations in the field of congenital cardiac care in ICD-11. For example:

-

English IPCCC term currently in ICD-11: Double outlet right ventricle with non-committed ventricular septal defect

-

ISNPCHD French translation: Ventricule droit à double issue avec communication interventriculaire sans relation avec les deux gros vaisseaux

-

WHO translation (done without ISNPCHD input): Ventricule droit à double sortie avec anomalie septale ventriculaire à distance

-

English equivalent to WHO translation: Double exit right ventricle with ventricular septal anomaly at a distance

An anglophone clinician would probably understand what is meant by Double exit right ventricle”, but clearly “ventricular septal anomaly at a distance” does not convey the same information as the phrase “non-committed ventricular septal defect”. This suboptimal translation and other similar errors need to be corrected. Fortunately, WHO have recently agreed to facilitate members of the ISNPCHD French translation team to work with the French government translation team to resolve these important issues.

The Foundation Component of ICD-11 (ICD-11 Foundation)

The full ICD-11 content is known as the ICD-11 Foundation , which represents the entire ICD-11 universe, divided into 26 sections, and can be accessed digitally [https://icd.who.int/dev11/f/en#/http%3a%2f%2fid.who.int%2ficd%2fentity%2f455013390]. The 318 diagnostic terms for CHD that were submitted by ISNPCHD in 2018 reside in the Foundation Component of ICD-11, within the Developmental Anomalies section, with the parent term “Structural developmental anomaly of heart or great vessels”, along with the additional 49 terms added to IPCCC by the WHO ICD-11 team since 2018.

The ICD-11 Mortality and Morbidity Statistics version (ICD-11 MMS)

Another feature of ICD-11 is that it is designed to be explicitly stratified to cater to different users, such as primary care, traditional medicine, and public health, producing so-called linearizations or “Tabular Lists”. The initial and most important overall linearization of ICD-11 was that published in July 2018 as the Mortality and Morbidity Statistics version , known as ICD-11-MMS , with a ‘blue’ website: [https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en], which is separate from the ‘orange’ ICD-11 Foundation website: [https://icd.who.int/dev11/f/en#/http%3a%2f%2fid.who.int%2ficd%2fentity%2f455013390].

ICD-11-MMS is the nearest equivalent to previous ICD versions. ICD-11-MMS includes a printed copy of top-level terms, and is designed to collect global data at a level of detail sufficient to capture important trends in the causes of death and prevalence of major disease entities. It is also the likely diagnostic coding system that will be used by nations for billing purposes. To achieve this objective, WHO in effect top-sliced the ICD-11 Foundation level content to include relevant higher-level terms, although not always with the input of clinicians. In addition, and consistent with previous ICD versions, the WHO has added two additional generic terms in each subsection of the ICD-11-MMS :

-

1. “Other specified … disease” (Y-codes). For example: LA89.Y Other specified functionally univentricular heart

-

2. “Disease…, unspecified” (Z-codes), which are equivalent to Not Otherwise Specified (NOS) in previous ICD versions. For example: LA89.Z Functionally univentricular heart, unspecified. Of note is that LA89 itself is the MMS code for Functionally univentricular heart.

Another example of the Y and Z codes is provided below:

-

1. Other specified … disease” (Y-codes). For example: LA87.0Y Other specified anomaly of tricuspid valve

-

2. “Disease…, unspecified” (Z-codes). For example: LA87.0Z Congenital anomaly of tricuspid valve, unspecified. Of note is that LA87.0 itself is the MMS code for Congenital anomaly of tricuspid valve.

These Y and Z codes do not appear in the ICD-11 Foundation . Y and Z codes are unique to the ICD-11-MMS version, as will be described in the following discussion. For example, the term “Straddling tricuspid valve” can be found in ICD-11 Foundation , but is not listed in ICD-11 MMS . If coding with ICD-11 MMS , the code LA87.0Y should be used to indicate that a more specific diagnosis is known.

For CHD, of the 367 paediatric and congenital cardiac terms currently in the ICD-11 Foundation , a subset of 104 terms have been retained and will appear in the ICD-11-MMS linearization. As the ICD-11-MMS is likely to be the first component of ICD-11 to be adopted by countries worldwide, ISNPCHD has created a many-to-one unidirectional map of the CHD ICD-11 Foundation level content to the CHD ICD-11-MMS content within Developmental Anomalies (Chapter 20). This many-to-one unidirectional map of the CHD ICD-11 Foundation level content to the anticipated 2022 version of the CHD ICD-11-MMS is provided in Table 3 of this manuscript.

Clinical nomenclature versus administrative nomenclature

Several studies have examined the relative utility of clinical and administrative nomenclature for the evaluation of quality of care for patients undergoing treatment for paediatric and congenital cardiac disease. Evidence from four investigations suggests that the validity of coding of lesions seen in the congenitally malformed heart via the 9th Revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-9) is poor. Reference Strickland, Riehle-Colarusso and Jacobs65,Reference Pasquali, Peterson and Jacobs91,Reference Cronk, Malloy and Pelech122,Reference Frohnert, Lussky, Alms, Mendelsohn, Symonik and Falken123

-

First, in a series of 373 infants with congenital cardiac defects at Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin, investigators reported that only 52% of the cardiac diagnoses in the medical records had a corresponding code from the ICD-9 in the hospital discharge database. Reference Cronk, Malloy and Pelech122

-

Second, the Hennepin County Medical Center discharge database in Minnesota identified all infants born during 2001 with a code for congenital cardiac disease using ICD-9. A review of these 66 medical records by physicians was able to confirm only 41% of the codes contained in the administrative database from ICD-9. Reference Frohnert, Lussky, Alms, Mendelsohn, Symonik and Falken123

-

Third, the Metropolitan Atlanta Congenital Defect Program of the Birth Defect Branch of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention of the United States government carried out surveillance of infants and fetuses with cardiac defects delivered to mothers residing in Atlanta during the years 1988 through 2003. Reference Strickland, Riehle-Colarusso and Jacobs65 These records were reviewed and classified using both administrative coding and the clinical nomenclature used in the Society of Thoracic Surgeons Congenital Heart Surgery Database. This study concluded that analyses based on the codes available in ICD-9 are likely to “have substantial misclassification” of congenital cardiac disease.

-

Fourth, a study was performed using linked patient data (2004-2010) from the Society of Thoracic Surgeons Congenital Heart Surgery (STS-CHS) Database (clinical registry) and the Pediatric Health Information Systems (PHIS) database (administrative database) from hospitals participating in both in order to evaluate differential coding/classification of operations between datasets and subsequent impact on outcomes assessment. Reference Pasquali, Peterson and Jacobs91 The cohort included 59,820 patients from 33 centres. There was a greater than 10% difference in the number of cases identified between data sources for half of the benchmark operations. The negative predictive value (NPV) of the administrative (versus clinical) data was high (98.8%-99.9%); the positive predictive value (PPV) was lower (56.7%-88.0%). These differences translated into significant differences in outcomes assessment, ranging from an underestimation of mortality associated with truncus arteriosus repair by 25.7% in the administrative versus clinical data (7.01% versus 9.43%; p = 0.001) to an overestimation of mortality associated with ventricular septal defect (VSD) repair by 31.0% (0.78% versus 0.60%; p = 0.1). This study demonstrates differences in case ascertainment between administrative and clinical registry data for children undergoing cardiac operations, which translated into important differences in outcomes assessment.

As discussed below, these challenges and problems persist with the 10th Revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10). Several potential reasons can explain the poor diagnostic accuracy of administrative databases and codes from ICD-9 and even ICD-10:

-

accidental miscoding;

-

coding performed by medical records clerks who have never seen the actual patient, in other words, coding performed by personnel not involved in the care of the patient;

-

contradictory or poorly described information in the medical record;

-

lack of diagnostic specificity for congenital cardiac disease in the codes of ICD-9 or ICD-10

-

inadequately trained medical coders.

Although one might anticipate some improvement in diagnostic specificity with the adoption of ICD-10, it is still substantially deficient compared to that currently achieved with the clinical nomenclature used in clinical registries. In this regard, ICD-9 has only 29 congenital cardiac codes while ICD-10 has only 73 congenital cardiac codes. It will not be until there is implementation of the paediatric and congenital cardiac components of ICD-11 that harmonization of clinical and administrative nomenclature will be achieved. The implementation of ICD-11, therefore, will resolve many of these challenging issues.

Summary

The art and science of outcomes analysis and quality improvement for paediatric and congenital cardiac care continue to evolve. The IPCCC nomenclature is utilized in multi-institutional registries and databases all over the world. 124,125 In this manuscript, we have presented the 2021 version of IPCCC, a global system of nomenclature for paediatric and congenital cardiac care that unifies clinical and administrative nomenclature.

Tables of IPCCC ICD-11 nomenclature for congenital cardiac diagnostic terms in ICD-11 Foundation

-

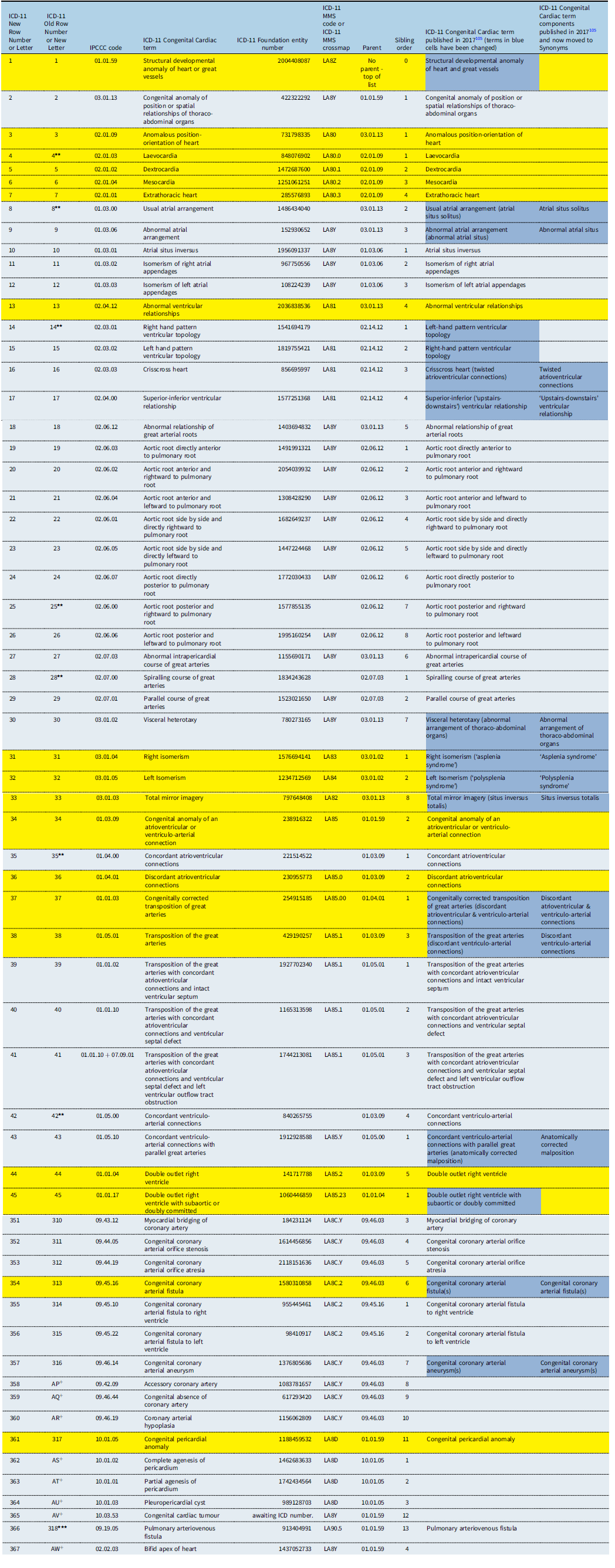

Table 1 presents the diagnostic hierarchy of the paediatric and congenital cardiac terms in the ICD-11 Foundation . Terms that appear in the ICD-11 MMS are presented in rows highlighted in yellow.

-

Table 2 contains the definitions, commentary, synonyms, and abbreviations for these terms of the paediatric and congenital cardiac terms in the ICD-11 Foundation . Terms that appear in the ICD-11 MMS are presented in rows highlighted in yellow.

-

Table 3 contains the various IPCCC ICD-11 Codes, including the IPCCC codes as well as the ICD-11 Foundation entity numbers and the ICD-11 MMS codes.

In the Tables:

-

+ = New terms added by the WHO ICD-11 team since the original 318 terms contained in the publication Reference Franklin, Béland and Colan105 from 2017

-

** = Terms that code normal human anatomy, but are important to specify when part of a complex congenital cardiac malformation

-

*** = Terms that are not located in the paediatric and congenital cardiac section of ICD-11

-

Rows with numbers in the second column labelled “ICD-11 Row Number or Letter” contain terms in the original 318 terms contained in the publication Reference Franklin, Béland and Colan105 from 2017.

-

Rows with letters in the second column labelled “ICD-11 Row Number or Letter” contain new terms added by the WHO ICD-11 team since the original 318 terms contained in the publication Reference Franklin, Béland and Colan105 from 2017.

MMS coding notes for Table 3:

-

1) The column titled “ICD-11 MMS code or ICD-11 MMS crossmap” contains the alphanumeric codes for terms listed in ICD-11 Mortality and Morbidity Statistics (highlighted in yellow). For the terms that are not highlighted (not in ICD-11 MMS), the column contains the alphanumeric codes of higher order MMS terms to which they have been crossmapped. For example, “Complete agenesis of pericardium” (not listed in MMS), has been crossmapped to MMS term “Congenital pericardial anomaly” (LA8D).

-

2) Several terms in MMS have two additional versions (not published here) with distinct alphanumeric codes (either ending in “Y” [Other specified] or “Z” [unspecified]). For example, in addition to the term “Congenital anomaly of coronary artery” (LA8C), the following terms also exist: “Other specified congenital anomaly of coronary artery” (LA8C.Y) and “Congenital anomaly of coronary artery, unspecified” (LA8C.Z). When available, the non-highlighted terms in Table 3 have been crossmapped to the “Y” version of higher order MMS terms, since it conveys the added information that a more specific diagnosis is known, but that the more specific term does not exist in MMS. For example, “Accessory coronary artery” has been crossmapped to LA8C.Y instead of LA8C.

-

3) The first term of Table 3, “Structural developmental anomaly of heart or great vessels”, is listed in MMS but does not have an MMS alphanumeric code. If wanting to code for this term in MMS, one must use either “Structural developmental anomaly of heart or great vessels, unspecified” (LA8Z), or “Other specified structural developmental anomaly of heart or great vessels” (LA8Y). Several non-highlighted terms in Table 3, such as “Bifid cardiac apex”, have been crossmapped to LA8Y, when no appropriate higher order term exists in MMS.

Table 1. IPCCC ICD-11 diagnostic hierarchy

Table 2. IPCCC ICD-11 Definitions

Table 3. IPCCC ICD-11 Codes

Acknowledgements

We thank all members of The International Society for Nomenclature of Paediatric and Congenital Heart Disease ( ISNPCHD ) for their tremendous dedication, leadership, and support of this initiative. We also thank Professor Robert H. Anderson, MD, PhD (Hon) and Professor Richard Van Praagh, MD for their decades of dedication to paediatric and congenital care and advancing the art and science of cardiac morphology and cardiac nomenclature. The creation of The International Paediatric and Congenital Cardiac Code ( IPCCC ) would not have been possible without their tremendous contributions.

Financial support

Over the past two decades, The International Society for Nomenclature of Paediatric and Congenital Heart Disease ( ISNPCHD ) and the creation of The International Paediatric and Congenital Cardiac Code ( IPCCC ) have been supported by the following organizations listed alphabetically:

-

American College of Cardiology, Chicago, Illinois, United States of America

-

“Andy Collins for Kids Fund”, Montreal Children’s Hospital Foundation, Montréal, Québec, Canada

-

“Angela’s Big Heart for Little Kids Fund”, Montreal Children’s Hospital Foundation, Montréal, Québec, Canada

-

Association pour la Recherche en Cardiologie du Fœtus à l’Adulte (ARCFA), Service de Cardiologie Pédiatrique et de Chirurgie Cardiaque Pédiatrique, Hôpital Necker–Enfants Malades, Paris France

-

Boston Children’s Heart Foundation and The Marram and Carpenter Fund, Boston, Massachusetts, United States of America

-

Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Canada

-

“Cardiac Kids Foundation of Florida” [https://cardiackidsfl.com/], Florida, United States of America

-

Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young of the American Heart Association, United States of America

-

Division of Cardiovascular Surgery, The Montreal Children’s Hospital of the McGill University Health Centre, Montréal, Québec, Canada

-

Children’s Mercy Hospital, Kansas City, Missouri, United States of America

-

Division of Pediatric Cardiology, The Montreal Children's Hospital of the McGill University Health Centre, Montréal, Québec, Canada

-

Drs. Ivan and Milka Tchervenkov Endowment Fund, Montreal Children’s Hospital Foundation, Montréal, Québec, Canada

-

Filiale de Cardiologie Pédiatrique et Congénitale de la Société Française de Cardiologie, France

-

Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children, London, England, United Kingdom

-

Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, Canada

-

Heart of a Child, Children's Hospital of Michigan Foundation, Detroit, Michigan, United States of America

-

Hôpital Marie-Lannelongue - M3C, Paris, France

-

Japan Research Promotion Society for Cardiovascular Diseases, Japan

-

Montreal Children’s Hospital Foundation, Montréal, Québec, Canada

-

Nicklaus Children’s Hospital Heart Program, Miami, Florida, United States of America

-

Secretaria da Cultura e Governo do Estado do Amazonas, Brazil

-

Sociedade Brasileira de Cardiologia - Departamento de Cardiologia Pediátrica e Cardiopatias Congênitas, Brazil

-

The Children’s Heart Foundation [https://www.childrensheartfoundation.org/], United States of America

-

Tokyo Women’s Medical University, Tokyo, Japan

-

University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota, United States of America

-

University of Padova, Padova, Italy

-

Ward Family Heart Center, Children’s Mercy Kansas City, Kansas City, Missouri, United States of America.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national guidelines on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.