German operetta of the early twentieth century was part of a transcultural entertainment industry involving cross-border financial and production networks, international rights management, and migrating musicians and performers.Footnote 1 In its production and reception, operetta relates closely to themes that have emerged in recent years concerning the meaning and character of cultural cosmopolitanism, a topic discussed in Chapter 8 of this book. The industrialization of theatrical entertainment was stimulated by an economic boom, and it became clear that a successful operetta could play night after night at one theatre for a year or more, a situation unimaginable for opera.Footnote 2 An industrial ethos also shaped aesthetic response. A ‘great’ stage work was regarded by producers, if not always by theatre critics, as one that ensured a surplus on the theatre’s profit and loss sheet. This industrial aesthetic informs a well-known comment attributed to Igor Stravinsky after George Gershwin asked him for composition lessons. Undoubtedly, the words would have been spoken in jest, but Stravinsky is said to have replied that it was he who needed to take lessons from Gershwin, since Gershwin made more money from composition.Footnote 3

Collaboration networks, in which groups of people worked as a team, were the norm in operetta production. Those who had previously delivered successful products came back together to do so again. The association of operetta production with industrial production was widely recognized.Footnote 4 The partnership of a book writer – responsible for the storyline and dialogue – and a lyric writer was often referred to as a ‘firm’ in Vienna. Examples were Stein and Jenbach, Schanzer and Welisch and, perhaps, the most successful of all, Brammer and Grünwald. Leo Fall’s satirical one-act operetta The Eternal Waltz, composed to an English libretto by Austen Hurgon, satirizes the industrial production of operetta with a plot based on the operations of a waltz factory. What is more, the industry was profitable: Fall signed a contract for this short work that netted him alone £2,500.Footnote 5 That would be equivalent to approximately £235,300 or $305,000 in 2017.Footnote 6 According to Ernst Klein, writing in the Berliner Lokal-Anseiger, Fall went on to earn nearly 4000 marks from its production by the end of April 1912 (£89,630 or $116,000 in 2017).Footnote 7 That income was from the West End production alone, because it was not given on Broadway until 24 March the following year, as the opening show of a new Times Square variety theatre, the Palace. Fall’s one-act operetta was one of several commissioned by Edward Moss for his flagship variety theatre the London Hippodrome (the headquarters of his chain of theatres).Footnote 8

In the early 1910s and again in the 1920s, Berlin, London, and New York were competing for dominance of the musical theatre market, but these cities were also collaborating on the transfer of cultural goods. Cultural traffic went from continental Europe to Britain and the USA, and vice versa. This exchange was happening well before the emergence of the jazzy Broadway musicals of the later 1920s. For example, Gilbert and Sullivan’s The Mikado was produced in Vienna in 1888 (as Der Mikado), and Sidney Jones’s The Geisha was given in Berlin in 1897 (as Die Geisha). The latter proved a major success on the German stage, and was second only to Die Fledermaus in numbers of performances during the first two decades of the twentieth century.Footnote 9 Berlin had become a thriving metropolis for stage entertainment in the early twentieth century. It had experienced a theatre-building boom in the previous century that bore similarity with what had happened in London.Footnote 10 In the 1890s, theatres around Friedrichstrasse were just as eager to put on musical comedies from London, as were West End theatres in the 1910s to mount productions of successful musical stage works from Berlin, such as the operettas of Jean Gilbert). Before the First World War, asserts Marion Linhardt, ‘a dense network of business connections between theatres, music publishers, composers and librettists had evolved in Central Europe, with Berlin and Vienna as centres’.Footnote 11 The full extent of the negative effect of that war on this business is unlikely to come to light, as journalist Henry Hibbert recognized in 1916.

One of the things we shall never know is the loss to English speculators of capital invested in undelivered or now unpracticable Viennese and German music at the time of the war outbreak. For the traffic had swelled to millions.Footnote 12

After the war, the Treaty of Versailles demanded that Germany pay massive reparations, which led to hyperinflation in Germany, and the introduction of the Reichsmark in 1923.Footnote 13 These were not the conditions to encourage the import of goods, but, conversely, they made exports highly desirable. Berlin was where theatre managers and producers from around Europe and North America travelled to view the latest stage successes and buy rights. The Shuberts regularly visited Europe looking for successful pieces and announcing their intentions to produce them.Footnote 14 An operetta hit in the modern city of Berlin was generally thought a more reliable indicator of its potential to succeed elsewhere, than was a warm reception in Vienna. Not until the mid-1920s did Broadway have a theatrical product to rival that of Friedrichstrasse. Before the advent of sound film, the music industry concentrated its attention on two cultural goods that had indisputable international appeal: operetta from the German stage and dance-band music from the USA.

Internationalization was evident in the presence of overseas offices of major Berlin companies associated with the theatre. One such was that of Hugo Baruch, who ran a business in Berlin supplying costumes, stage décor, and props to the major theatres, and had offices in Vienna, London, and New York.Footnote 15 Baruch was the main supplier of scenery and costume for Oscar Straus’s The Chocolate Soldier in London, 1910, and of Jean Gilbert’s The Queen of the Movies on Broadway, 1914. Publisher Felix Bloch Erben dealt with English rights to many operettas from an office in London. Berlin’s Metropol-Theater (now the Komische Oper) registered on London’s Stock Exchange in 1912.Footnote 16 Those involved in the business of music aimed at a global market; this had been true of music publishers since the nineteenth century, and it was now the same for record companies. Meanwhile, as entrepreneurs were building an international business – dealing with foreign agents, managing performing rights, and hiring artists – operetta was stimulating peripheral businesses locally. As theatre-going boomed, there was a financial impact on printers, cabbies, florists, and restaurants. Among the popular West End restaurants, for example, were Romano’s, Gatti’s, Rules, and Kettner’s (the latter being a favourite with those involved in productions).Footnote 17 For anyone interested in making an evening of German culture, the Gambrinus restaurant in Regent Street served German ‘dishes of the day’ and lager.Footnote 18

The Purchase of Rights

Rewards for composers varied, especially at the start of their careers. Lehár sold the publishing rights to Der Rastelbinder for the equivalent of £80, but claimed the publisher made a hundred times that amount from sales.Footnote 19 Even at the height of his success with The Merry Widow, he experienced some financial problems. One involved his original publishing contract, and the other with the fact that the USA was not a signatory to the Berne Convention on copyright. However, a degree of amicable resolution proved possible, as the Daily Mail made clear in its tribute to this operetta, just after the second anniversary of its first performance in Vienna.

The Viennese music publisher Bernhardt Herzmansky has made over £70,000 profit out of the publication of the musical score. He got the concession for very little from the composer, who never expected to see the public buying his music … however, … he generously gave him a new contract with higher royalties. … Franz Lehár has been paid in fees for performances of his opera upwards of £60,000. The librettists have netted nearly £40,000. … In New York the gross receipts at the New Amsterdam Theatre are each week in excess of £4000, and one can only guess how much the sale of the music amounts to. For the composer it was unfortunate that there was no copyright in his music in the United States, but Mr Henry W. Savage, the manager who is running the opera there, is paying full fees on the theatre performances. … In London, fifty thousand copies of the vocal score have been sold by the publishers, and they have supplemented the popularity of ‘The Merry Widow’ by selling two hundred thousand copies of the famous waltz which is danced in the second act.Footnote 20

In 1924, Eduard Künneke was engaged by the International Copyright Bureau, located in the Haymarket, London, to compose four operettas for the Anglo-American market. He visited New York, where he was to work for the Shubert brothers. He adapted and arranged music of Offenbach, and added some of his own, for The Love Song at the Century Theatre, 1925; he composed Lover’s Lane to a libretto by Arthur Wimperis und Harry M. Vernon for production in London; and he then set to work on Mayflowers for the Forrest Theatre, New York (1925) and Riki-Tiki for London’s Gaiety Theatre (1926). In January 1927, however, Künneke signed a highly disadvantageous contract with Ernest Mayer, the manager of the International Copyright Bureau. He did so in return for £100, which he needed at a time of financial difficulty. There had been massive inflation in post-war Germany, and in 1924 the Reichsmark had replaced the Papiermark – one Reichsmark being worth 1000,000,000,000 of the latter. Künneke already had an agreement in place with his regular librettists Haller and Rideamus to split royalties 70/30 in their favour. Now he signed an agreement with Mayer that, with respect to six operettas, allocated to the Bureau half of his 30 per cent performance royalties, as well as a share of his publication royalties, until a figure of £200 was reached. By this means, the firm, during 1928–39, was to make around £1,300 for their initial outlay of £100.Footnote 21

The buying of rights was one of the most important activities of the entrepreneur. George Edwardes had secured the American rights as well as the British rights to Die lustige Witwe, and was therefore able to sell the American rights to Henry W. Savage. The operetta still made a fortune for Savage, and exceeded 5000 performances when the production went on tour.Footnote 22 Nevertheless, the lesson was learned, and Savage was quick to seize the opportunity to purchase the exclusive right to produce Kálmán’s operettas in any English-speaking country.Footnote 23

Fred C. Whitney jumped in early – even before the Vienna premiere – to buy the rights of Straus’s Der tapfere Soldat for production as The Chocolate Soldier on Broadway. Rudolf Bernauer and Leopold Jacobson had based their libretto on George Bernard Shaw’s Arms and the Man (1894), but Whitney had cared less about annoying Shaw than did Edwardes. He was, nevertheless, disappointed by its Viennese reception, and decided to have a try-out in Philadelphia. Finding that it was a hit there, he arranged for 250,000 copies of an enthusiastic New York Times review to be published and distributed in New York. He then made arrangements with Philp Michael Faraday, manager of the Lyric Theatre, London, for the Broadway version to be performed there, produced by its librettist, Stanislaw Stange. Beneath the title on the programme, the audience read the following: ‘With apologies to Mr BERNARD SHAW for an unauthorized parody on one of his Comedies.’

Faraday profited from The Chocolate Soldier and Gilbert’s The Girl in the Taxi at the Lyric Theatre, but lost money on other pieces. He was declared bankrupt in 1914 but was able to discharge his debts over the next six months. He also had touring companies bringing out-of-town profits. Herbert Carter, the general manager for tours of Faraday’s principal companies, organized six tours of The Chocolate Soldier, as well as tours of The Girl in the Taxi and Edmund Eysler’s The Girl Who Didn’t (Der lachende Ehemann). Inquiries about booking touring companies could be made at the appropriate London theatre, or correspondence could be directed to the Manager’s Club, 5 Wardour Street. Tours were usually undertaken by the London company after the production closed in that city, but, before that happened, some theatres sent out touring companies to the provinces and abroad. The same was true of New York, where the Shuberts lost no time sending out successful productions on tour. It did not always work out as expected: between May and September, Straus’s The Last Waltz made a total net profit of $34,717.65 at the Century Theatre but lost heavily on performances by the touring company.Footnote 24

Joseph Sacks, a theatrical entrepreneur of Polish or Russian Jewish descent (he was unsure himself), bought the UK rights to The Lilac Domino (Der Lila Domino) and produced it at the Empire, Leicester Square, in 1918. On Broadway, The Lilac Domino had enjoyed good press notices, but low box-office returns. When he bought the rights from the Smith brothers, he rejected as too risky their offer to sell their entire interests for a small sum.Footnote 25 This proved fortunate for the brothers, but galling for Sacks, because the operetta ran for 747 performances in London. Sacks was responsible for the first production of a new Lehár operetta after the First World War, The Three Graces (Der Libellentanz), again at the Empire (1924).

Copyright and Performing Right

Operetta, as a transnational genre, required international copyright protection for business to flourish, and this protection had been lacking or proven inadequate in the nineteenth century. Symptomatic of that were the problems Gilbert and Sullivan suffered with piracy in the USA; it was probably an ironic coincidence that their first attempt to establish an incontestable American copyright was with The Pirates of Penzance. The Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works (1886, and later revisions) played an important role in stimulating the European entertainment business. The USA, although not a signatory to that agreement, offered a measure of copyright protection to selected nations in the Chace Act of 1891, and signed acceptance of the Buenos Aires Convention, a copyright treaty of 1910. The UK’s Copyright Act of 1911, the first important legislation since 1842, had been made necessary by the desire to implement the terms of the Berne Convention. International copyright agreements built up the confidence of transnational financial institutions.Footnote 26 Performances of operetta in England, France, and the USA brought the biggest royalties.Footnote 27

Provision was made for a performing right (in addition to copyright) in the UK’s 1842 Act, but it was seldom enforced by publishers. In France, performing rights were collected from 1851 on, including those from performances of French works in the UK. The English Performing Right Society (PRS) was not founded until 1914 but, from then on, argued that all public venues where music was performed should hold licences for music and fees should be collected. It was, in the end, the sudden drop in royalties from record sales, seemingly caused by radio broadcasts, that clinched the argument. No provision for broadcasting had been made in the 1911 Act. The PRS came to an arrangement with the BBC and the Postmaster General whereby owners of wireless sets (that is, radios) paid for a licence, and the PRS received a fee from the BBC based on the number of licences issued. Music publisher Frederick Day became the PRS’s Director in 1926. Royalties collected were normally distributed in three equal parts to author, composer, and publisher. In the USA, in 1924, there was a proposal before Congress for a change in copyright law that would mean authors and composers would receive no payment for their productions when they were broadcast by radio. Harry B. Smith, the distinguished operetta librettist, was part of a delegation sent to Washington to protest by ASCAP (the American Society of Composers, Authors, and Publishers, founded in 1914).Footnote 28 Some singers were slow to understand the profits record royalties could bring. Richard Tauber’s wife Diana claimed that he earned royalties on only 66 of the 700-odd records he made, and that he sold the rights of his massive international hit ‘You Are My Heart’s Delight’ to Odeon Records for an outright sum of £80.Footnote 29

Theatres in London and New York

The most important theatres for musical comedy and operetta in London were the new Gaiety (1903), Daly’s (1893), the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane (the present building dates back to 1812), the Lyric (1888), and the Shaftesbury (1888). Daly’s Theatre, situated at the junction of Cranbourne Street and Leicester Square, was the most celebrated of West End operetta theatres, especially under the management of George Edwardes. It was the first theatre in London built for an American, Augustin Daly, although Edwardes was involved from the start, because he owned the lease to the land on which it was erected, having originally hoped to build his own theatre. Cranbourne Street was at the time a dilapidated neighbourhood. The building of this theatre is an early example of using the arts to regenerate a rundown urban area, something more associated with the 1990s than the 1890s. It was designed by architects Spencer Chadwick and C. J. Phipps with an Italian renaissance exterior and a plentiful assortment of cupids inside. The old Gaiety was a joint-stock company in the 1890s, with Alfred de Rothschild holding the majority of shares, but it was replaced by a new theatre of the same name in 1903, designed by Ernest Runz, and built at a cost of £88,000.Footnote 30 It was situated at the corner of Aldwych and the Strand and survived until 1938, when London County Council’s demand for £20,000 worth of alterations was considered uneconomic.Footnote 31

Theatres that promoted operetta in New York were of more recent build, although the Casino had been built specifically for operetta in 1882 and opened with Strauss Jr’s Queen’s Lace Handkerchief. Other important theatres for operetta were the Knickerbocker (1893, called the Abbey until 1896), the New Amsterdam (1903), the Century (1909), the Globe (1910, now the Lunt-Fontanne), and the Shubert (1913). The New Amsterdam in West 42nd Street was the flagship of the Abraham Erlanger theatrical empire.Footnote 32 Its façade was beaux arts (French neo-classical), but its interior was art nouveau. It was New York’s first building to embrace that new cosmopolitan style. With a seating capacity of 1702, the New Amsterdam was Broadway’s largest theatre at the time of its opening. In October 1907, The Merry Widow was given there, and at the end of December it was reported that the production was ‘likely to make an unparalleled profit of one million dollars by the end of the Broadway season’.Footnote 33

There was an entertainment boom in the first decade of the twentieth century in New York, and the entrepreneurial Shubert brothers began building lavish theatres. They leased their first, the Herald Square, in 1900. Sam Shubert had worked his way into theatre management from humble beginnings as a ticket taker and, being rewarded with some success, his older and younger brothers took interest. The Shuberts soon acquired other theatres, among them the Casino and the Lyric (both in 1903). They cooperated initially with the Theatrical Syndicate headed by Erlanger but began to feel it was too controlling. Erlanger was someone who liked to have his own way; P. G. Wodehouse and Guy Bolton refer to him as ‘the Czar of New York theatre’, but his anxiety about competition from ‘the up-and-coming Shuberts’ increased in the 1910s.Footnote 34 Sam had died in a train crash in 1905, leaving his brother Lee to take charge of finances, and Jacob (always known as J. J.) to deal with productions. Cars and taxi-cabs were replacing the horses and carriages of Times Square, and it was a Horse Exchange property that Sam and J. J. chose to convert into their Winter Garden Theatre, which architect William Albert Swasey modelled on the Wintergarten in Berlin. It opened in 1911 and held an audience of over 1500. It was a home to spectacle and revue, from 1912 hosting the long-running series of summer revues called The Passing Show. Yet Eysler’s Vera Violetta was produced in the first year of opening, and Kálmán’s The Circus Princess (Die Zirkusprinzessin) was given there in 1927.

Theatre productions of various kinds rose to nearly 200 in the 1921–22 New York season. One reason was the number of new theatres opening, so that there were now 55 Broadway theatres. Nonetheless, some plays failed quickly.Footnote 35 Broadway was booming almost out of control in 1925–26, with around 260 productions, of which 42 were musical plays. At the height of their success in 1927, the Shuberts owned 104 theatres, and booked performances into more than 1000 theatres throughout the USA.Footnote 36 Sam and Lee had opened a London theatre, the Waldorf, in 1905, which became the Strand Theatre in 1909. It was bought by F. C. Whitney in 1911, who sold it two years later to Louis B. Mayer (before the latter turned his attention to film). Today it is the Novello Theatre.

The brothers’ flagship theatre, the Shubert, was built in 1913. Its sgraffito exterior, designed by Henry B. Herts, and the plasterwork and series of panels in the interior, painted by J. Mortimer Lichtenhauer, gave considerable distinction to this edifice. One of the theatre’s triumphs was Kálmán’s Countess Maritza, starring Yvonne d’Arle and Walter Woolf, which opened there in September 1926, in a version by Harry B. Smith. Additional numbers were provided by Sigmund Romberg and Al Goodman. The architect Herbert J. Krapp, who had trained under Herts’s supervision, became a key designer for the Shubert theatre enterprise from 1916 on. It was to him the Shuberts turned when, in 1917, they built the Broadhurst and the Plymouth theatres, which strengthened their presence in the 44th and 45th Street area. Krapp was to be involved in the construction of many more, including the Ambassador, which opened in February 1921, and was home to the hugely successful Blossom Time in September that year, and the Imperial, which opened in December 1923. Despite all the brothers’ business acumen, however, the Shubert Theatre Corporation went into receivership in October 1931, in the aftermath of the Wall Street Crash. A meeting of creditors was arranged in December 1931 to discuss the problem of raising money to continue business, after discovering that the Corporation had been losing over $21,000 weekly since the receivership.Footnote 37 Surprisingly, in April 1933, when a sale of their theatres took place, the Shubert brothers were able to buy many of them back.Footnote 38 In 1937, the Imperial was the location for Frederika (Friederike), the final production of a new Lehár operetta by the Shuberts until after the Second World War, when Yours Is My Heart (Das Land des Lächelns) was given its belated first Broadway outing in 1946 at the Shubert Theatre.

Theatre Finances: A Short Case Study of Daly’s

A sense of the complexity of theatre finances can be gleaned from the income and expenditure of Daly’s in London. In the years before the First World War, Edwardes would spend an average of £1500 a week on the salaries of those performing on stage, and £1600 for some 200 other staff.Footnote 39 These included clerks, scene shifters, lighting technicians, prompters, dressers, a wardrobe mistress, a wig maker (Willie Clarkson), a commissionaire (Mr Robinson held this position for 35 years), cleaners (both for the theatre and for costumes), programme sellers, and, importantly, a rat catcher. There were additional expenses relating to rent and taxes, and there was greater expenditure on scenery and costumes in London than in Vienna. The Daly’s orchestra was reputed to be ‘one of the most expensive in Europe’,Footnote 40 even if Lehár was disappointed to find 28 players for The Merry Widow, when he had asked for 34 (the Daly’s orchestra later grew to 40 strong).Footnote 41 If the rise in value of the pound between 1909 and 2017 is assessed alongside the rise in the RPI in the UK and the CPI in the USA, then the weekly spending on staff alone would be equivalent in 2017 to £148,600 ($193,000) for performers, and £158,500 ($205,000) for other staff.Footnote 42 A particular problem in financing operetta productions is that they are subject to the ‘law of Baumol’ because they stand apart from the normal rules of labour productivity: it is not easy for a manager to engage fewer performers than the operetta requires, and performers are not in a position to become more efficient and productive as the weeks pass.Footnote 43

The costs of production presented no difficulty if the theatre enjoyed a runaway success. The Merry Widow, for example, played for two years at Daly’s, and was seen by approximately 1,167,000 people, which brought in box office receipts in excess of £1 million (£99 m and $128 m in 2017).Footnote 44 On 31 January 1909, a dinner was held at the Hotel Cecil to celebrate its achievement. Forbes-Winslow had no doubt that, eventually, the gross receipts ‘ran into many millions sterling’.Footnote 45 However, profits such as these were the exception. Edwardes regarded box office returns of £2000 a week as ‘moderately good business’, although an income at this level meant that production expenses could not be covered for weeks.Footnote 46 He summed up his opinion of the theatre business as follows:

London is not a source of profit to the producer of musical plays, because the salaries and rents are so enormous. That is my experience. It pays, of course, to produce in London, because the advertisement given to the piece by people who have seen it gives an enormous help to the companies I send to the provinces, America, Africa and Australia.Footnote 47

It might be added that Edwardes sent companies to both North and South America, and to India, too.Footnote 48 For a long time, The Merry Widow was bringing in £2000 a week in the provinces,Footnote 49 where touring companies avoided the huge expenses of the capital.

This brief account of finances is enough to reveal the complexity of the dealings in which Edwardes was involved, although he did not have to cope entirely on his own. Fred King was his assistant manager, and, for many years, his main business assistant at Daly’s was Emilie Reid, who, after he died, was hired by Alfred Butt for Drury Lane. The estate debt after Edwardes’s death in October 1915 was £80,000, but the profits generated by the success of The Maid of the Mountains during its three-year run (1917–20) paid that off comfortably.Footnote 50

Edwardes’s successors at Daly’s were James White, who became chairman of directors, and Robert Evett, who took over as managing director. Evett went to Berlin looking for something to produce and was recommended to see Straus’s Der letzte Walzer. He recognized the attraction of the music but realized ‘certain revisions would have to be made in order to bring it into line with British requirements’.Footnote 51 It is significant that he chooses the word ‘requirements’ and not ‘taste’, thus implying practicalities rather than aesthetic sensibilities. He discovered that this operetta had been bought by an American syndicate for film adaptation (silent film at this time).Footnote 52 He contacted them and secured the rights to produce it in London in December 1922. Next on his itinerary was Vienna, but, the evening before his departure, Jean Gilbert arrived at his hotel and played him selections from his new operetta Die Frau im Hermelin, which became The Lady of the Rose in London, ten months before the production of The Last Waltz. When Evett reached Vienna, he went to see Das Dreimäderlhaus, but he considered that ‘the interest was too local’ to warrant his purchasing it for the London stage.Footnote 53 He acknowledged later that, as Lilac Time, it was a great success, but he put that down to William Boosey’s having asked George Clutsam to re-arrange the music.

In 1922, to Evett’s shock, White bought Daly’s at a price rumoured to be over £200,000.Footnote 54 Unfortunately, the annual costs of this theatre in the 1920s were running at a similar figure.Footnote 55 White came from a poor background in Rochdale but his business acumen had made him wealthy. He was no stage director, even if he sometimes sat in the stalls at rehearsals and passed comments. José Collins remarks that there was as much knowledge of the theatre in Evett’s little toe ‘as there was in the whole of Jimmy White’s anatomy’.Footnote 56 Evett soon left Daly’s and began producing at the Gaiety. White decided to revive The Merry Widow in 1923 and was delighted to see it achieve a run of 238 performances. That success encouraged comedian George Graves to promote another revival at the Lyceum a year later.Footnote 57 At first, the hot summer threatened the success of the Lyceum revival, which opened at the end of May, but the good weather did not continue. Sunshine must be considered a negative factor for summer productions indoors (it badly affected theatre attendance in the West End in 1925), although, conversely, it is vital to the success of open-air stage performances. Like Edwardes, White was a gambler, but one who took one too many risks. On 29 June 1927, he committed suicide, leaving a note confessing, ‘I have been guilty of the folly of gambling, and the price has to be paid’.Footnote 58

Although sympathetic to his fate, Graves was scornful about White. The actor-manager was in decline in the 1920s and, although London’s leading theatre impresarios, such as Alfred Butt, had been involved with theatres for many years, there were others attracted to theatre simply as a commercial business opportunity.Footnote 59 Graves clearly thought White was only interested in personal profit, and declared that White was ‘about as competent to run a theatre in succession to George Edwardes’ as he himself would be deputizing for Albert Einstein in a BBC talk ‘on the velocity of light-waves’.Footnote 60 On the other hand, according to Graves, Solly Joel the diamond millionaire who bought Drury Lane Theatre showed an interest that ‘was never purely financial’.Footnote 61 Another person who entered the theatre business primarily as a financial backer of productions – but was generally liked – was William Gaunt.Footnote 62 He owned several West End theatres in the 1920s, including the Gaiety.

The next manager of Daly’s was Harry Welchman, who had performed many leading roles in operettas. Two months after taking up his post in early 1929, he resumed his role as Colonel Belovar in a revival of The Lady of the Rose, advertised as the work of Harry Welchman Productions Ltd. He was disappointed to find that he was unable to make the theatre profitable and concluded that, with a seating capacity of around 1225, it was too small to compete with the larger cinemas and their cheaper seats.Footnote 63 There had been a boom in cinema building during the 1920s: the number of cinemas controlled by circuit groups (such as Associated British Cinemas and Gaumont) was 862 in 1927, 1382 in 1932, and 2252 in 1938.Footnote 64 George Grossmith commented on the competition theatre faced in 1929:

In these days when musical entertainment is provided not only by theatres, music-halls and cinemas, but also by hotels, restaurants, cafés, riverside resorts, to say nothing of the gramophone and the wireless, five or six months may be looked upon as a healthy run.Footnote 65

Worse was to come because, unlike theatres, cinemas began opening on Sundays in the 1930s. The cast of a West End production would normally have given a matinee performance as well as an evening performance on Saturday, so a day of recuperation was needed.

Theatres in the Great Depression

South African millionaire Isidore W. Schlesinger bought Daly’s for a sum in excess of £230,000 in June 1929, but financial misery was around the corner. The London Stock Exchange crashed on 20 September, and on 29 October came the Wall Street Crash. This was the twentieth century’s worst international financial crisis, and the following Great Depression affected cities in the USA, Western Europe, and further afield until 1934. The flow of international capital was reduced, and a deflationary spiral began, leading to a decline in industrial production and a rapid rise in unemployment. As the world economy took a downward turn, exports and investment in new projects became difficult and consumers were worried about spending money.

In Vienna and Berlin, the situation was worse than in the war years, when Die Csárdásfürstin, Die Rose von Stambul, and Das Dreimäderlhaus all played to full houses.Footnote 66 In the early 1930s, when audience numbers could not be relied on, Berlin’s biggest theatrical entrepreneurs, the Rotter brothers, devised various marketing tricks to lure people into theatres, such as leaving half-price vouchers in cigarette shops, hairdressers, and bars.Footnote 67 The Charell revues at the city’s largest theatre, the Großes Schauspielhaus, helped to stem the decline of theatre attendance at the turn of the decade. Theatres in Vienna were seeing profits fall in the late 1920s, and with harsh consequences: in 1929, the Carltheater, second place only to the Theater an der Wien for operetta productions, was the first to close its doors. Two years later, the Johann-Strauß-Theater became the Scala Cinema, although it was occasionally used for theatrical performances. The Theater an der Wien was not doing well, either, and faced bankruptcy in 1935 (under Hubert Marischka’s management). It became, for most of the time, a cinema in 1936, but closed down completely in 1938 just before the Anschluss. In 1939, operetta was found only at the Raimund-Theater and, occasionally, the Volksoper.

Adding to the problems brought on by the Depression in the USA, was the Eighteenth Amendment, passed in January 1920, which made it illegal to sell alcoholic drinks or produce them for sale. Drinking them was not itself illegal, and the production of wine and cider (not beer) for consumption in the home was permitted. Bootlegging became common by 1925. In that year, Graves was invited to New York by the Shuberts, who wanted him to take the comedy role in The Student Prince. Having last been there in 1907, he noticed how much the city had changed following Prohibition. Racketeers and gangsters appeared to be undermining municipal, state, and federal politics, and the welcoming hospitality he was given was ‘mixed up with furtive mumblings about bootleggers and speakeasies’.Footnote 68 In 1930, when Oscar Straus was in Hollywood, he was one of many hiding bootleg liquor in an office cupboard.Footnote 69 Prohibition persisted until December 1933.

Burns Mantle described the 1928–29 season as one of the worst within living memory, and managers and producers (now lacking the presence of the astute Henry Savage, who had died during the previous season) were unsure what direction to take.Footnote 70 The chief cause was the threat of competition from film ‘talkies’ but there were also concerns about theatre immorality and anxiety about patrons and speculators. Fear of the talkies subsided somewhat in the next season, when it was discovered that successful plays could be resold to Hollywood ‘at extravagant figures’.Footnote 71 Nevertheless. theatre profits were not what they once were, and there was a drop in productions. The Shuberts mounted revivals of operettas by Victor Herbert, who had died in 1924. This was the season before the economic Depression; in that next season, takings fell steeply and two theatres known for operetta, the Casino and the Knickerbocker, were both demolished in 1930. Financial misery continued in 1931–32, which Mantle judged ‘commercially, the worst year the theatre has suffered in its recent history’.Footnote 72 The dust that followed in the wake of the Wall Street Crash was settling, however, and the rivalry between Erlanger and the Shuberts was attenuated by the newly organized American Theatre Society and the mutual protection offered by the combined booking office.

Erlanger, who had controlled over 700 theatres at the height of his power, was suffering badly and saw the necessity of ending his rivalry with the Shuberts by agreeing to combine subscription audiences and work amicably together in the American Theatre Society. Unfortunately, he died in 1930 before witnessing much progress, but an important subsequent change was an end to conflict and unfair competition when sending plays on tour, which sometimes left audiences facing the clash of a successful New York revue and a well-received musical comedy on the same evening.Footnote 73 Broadway business began to rally in 1932–33, although Mantle claimed it was surviving on ‘half rations’, because only half the theatres were open, and revivals represented nearly a third of the total number of productions.Footnote 74

On West 44th Street, Erlanger’s Theatre had been lost in the Depression and was now the St James Theatre. Mantle sums up the effects of the Depression on Broadway:

Its leading producers had lost all their money. Its more dependable angels were in a state of bankruptcy. Its better playwrights and its better actors had deserted to the motion pictures. Its theatre properties were, for the most part, in the hands of mortgage bankers who could not, for the life of them, think of anything to do with them.Footnote 75

The gloom had not abated when the new season began in August 1933, but, remarkably, in October, the theatre began to recover. Mantle offers three reasons: first, there was curiosity on the part of a younger public brought up on the movies and eager for a change; second, actors that had deserted the theatre for Hollywood were returning to the stage; and, third, audience enthusiasm was stimulated by the quality of some of the early-season plays.Footnote 76 Mantle concedes that the repeal of laws prohibiting alcohol consumption may have had an effect on theatre attendance but adds that New York ‘was never exactly athirst in the driest days of prohibition’.Footnote 77 What is more, the introduction of bars into the theatres was consistently refused by ‘liquor boards’. During 1934–35, the Depression was abating, and large numbers of motion picture talent scouts flocked to the Broadway theatres. Some film producers sponsored productions.Footnote 78 The biggest single operetta success of the season was The Great Waltz (Walzer aus Wien), the first theatrical enterprise of the Rockefellers at the large Center Theatre. Alan Jay Lerner was clearly premature in dating the end of operetta to ‘the last days of the twenties’.Footnote 79

At the end of the 1935–36 season, which featured no premieres of operettas from the German stage, Hollywood producers took umbrage at the provisions in a new contract made between play producers and the new Dramatists’ Guild-League of New York Theatre. It divided the money paid for rights to a play into 60 per cent for the author and 40 per cent for the producer, and, even if a film producer had financed the play, the film rights were still to be offered on the open market.Footnote 80 This was the first season in which the WPA (Works Progress Administration) sponsored the Federal Theatre Project, allocating government funding to unemployed artists, writers, and directors, in recognition of the impact of the economic crisis. The vision was the establishment of a national theatre, but that was never realized. In the next Broadway season, there was an inevitable reduction in interest from Hollywood because of the new contractual conditions. However, Warner Brothers were obliged under the terms of an old contract, to help finance, together with the Rockefellers, the extravagant production of Ralph Benatzky’s White Horse Inn at the Center Theatre in October 1936.Footnote 81 Any worries must have soon dissipated when the box office recorded a second-night gross of $7,240.Footnote 82

In London, Daly’s financial difficulties became evident in 1932, when, in a desperate attempt to balance the books, it put on a non-stop variety season and, at the end of the year, a pantomime. The curtain came down for last time at Daly’s on 25 September 1937, and on that sad occasion there was no celebration, just a simple tribute paid by the manager Cecil Paget. The last operetta to be performed there had been Offenbach’s The Grand Duchess of Gerolstein (from the end of April to the middle of June). The last production of all was of Emmet Lavery’s play The First Legion. The theatre was bought by Warner Brothers for some £250,000,Footnote 83 and demolished in order to build a cinema.Footnote 84

Selecting a Suitable Operetta for Production

In 1904, the impresario Oswald Stoll employed renowned theatre architect Frank Matcham to build the London Coliseum Theatre of Varieties. It was an opulent free baroque design with lavish interiors and a huge auditorium. Stoll owned a chain of variety theatres but always wanted this one to be special. It was renovated and renamed simply the Coliseum Theatre in 1931, and Stoll sought a spectacular show for the reopening. With a seating capacity of nearly 2500, it was London’s second largest theatre (Drury Lane had just over 2500 at this time), so he looked at what was on offer at Berlin’s Großes Schauspielhaus, which held an audience of over 3000. The size of these theatres meant that they were able to ward off competition from large cinemas, provided they offered something exciting. Erik Charell’s production of Im weißen Rössl, with music by Benatzky, Stolz, and others, had been a runaway success, and so, despite the gloomy economic climate, Stoll decided to bring it to London and to hire Charell to direct it personally.Footnote 85 Under the title White Horse Inn, it was the most elaborate production ever seen on the West End stage and cost Stoll around £50,000.Footnote 86 Nevertheless, once the first reviews appeared, there were bookings for £60,000 worth of seats.Footnote 87 The Play Pictorial describes the stage spectacle:

A handsome, comfortable looking Inn on one side of the stage, and facing it a substantial looking chalet, from whence issue yodelers, foresters, cowherds, Alpine guides, dairymaids; and at the back gorgeous mountain views, mountain lakes, mountain places of refreshment. Tyrolese dancers, shepherds and shepherdesses, all gay in colours, some pinky in their nethermost ‘altogether’. A revolving stage that revolves all this wonderful scenery before us like a solid presentation of the Transformation scenes of our youthful pantomimes.Footnote 88

Stoll wanted the production at the Coliseum to resemble closely that at the Großes Schauspielhaus, even to the extent of having scenery overlap into the auditorium.

The foyers of the theatre have been made to resemble the corridors of an inn, and on each side of the proscenium, in the shape of boxes, part of ‘The White Horse’ is built up to the ceiling, and on the opposite side is a Tyrolean house.Footnote 89

Although the spectacle of White Horse Inn was admired, one critic described the music offhandedly as having ‘a jolly ring, moving generally to the hearty thumping of beer mugs on tables’.Footnote 90

The programme for the production advertises the availability of Edison Bell records of the most popular items, at one shilling and sixpence each, and The Play Pictorial issue devoted to White Horse Inn contains an advertisement for Columbia records featuring Jack Payne and His BBC Dance Orchestra (Figure 3.1).

Operetta was not just a theatrical medium, it was intermedial, and records were an important and profitable media platform. The subject of operetta and intermediality is taken up in Chapter 6. Technology, which played an important role in this production, especially in stage lighting, is discussed in Chapter 7.

Theatre Tickets

By adding new theatres to his business, Stoll was operating in a manner known as horizontal integration. Ticket agent Keith Prowse adopted a similar strategy, by opening new branches.Footnote 91 Keith Prowse also moved into related businesses (vertical integration). The firm had traded in sheet music and musical instruments in the previous century, but in the 1920s they were selling records and gramophones, and supplying bands and concert parties for various social functions.Footnote 92 When, the advertisement shown in Figure 3.2 appeared, the Keith Prowse ticket agency had become the largest in London, with dozens of branches, some of them located in hotels (such as the Grosvenor, Claridge’s, and the Savoy). Their strapline was: ‘YOU want Best Seats. WE have them’.

Figure 3.2 Advertisement from the programme to the Coliseum production of White Horse Inn, 1931.

The cost of tickets is not given in Figure 3.2, but a year later for Casanova, Charell’s next production at the Coliseum, prices were six shillings to fifteen shillings for reserved seats (approximately £20/$28, and £49/$64 in 2017) and two shillings and sixpence for unreserved (approximately £8/$13 in 2017).Footnote 93 Matinee performances had slightly cheaper reserved seats (four shillings to twelve shillings and sixpence).Footnote 94 In February 2017, ticket prices in the stalls and dress circle at the London Coliseum for The Pirates of Penzance ranged from £20 to £105 ($25 to $132 at that month’s exchange rate), plus a booking charge per ticket of £1.50. It is evident that, in relative terms, seats at the Coliseum for an operetta performance were more expensive in 2017 than in 1932.

Ticket speculators were not the problem in the West End that they were on Broadway. Arthur Hammerstein blamed the premature closure of Kálmán’s Golden Dawn in 1928 on speculators and ticket touts, and accused some agencies of deliberately diverting patrons from this production as a reprisal for his activity against various brokers.Footnote 95 The 1930–31 season witnessed a sustained attack on their practices when the League of New York Theatres was created. This body aimed to control sales via accredited brokers, who were not permitted to charge more than 75 cents above the ticket price for their service. The non-accredited brokers claimed their trade was perfectly legitimate and fought back with an injunction against the League. The battle ended when the Postal Telegraph Company offered to sell tickets at no more than a 50-cents mark-up at all its branches (which numbered around 160). The League immediately accepted.Footnote 96

Music Publishers

Businesses involved with theatre were never single-mindedly focused on the stage. The Savoy was famed not only as a theatre but also as a hotel and restaurant. Music publishers knew the value of investing in theatres, since these were places in which their wares were promoted, and they were keen to be involved in the purchasing of rights. In London, Chappell, a major publisher of operetta with branches in New York, Toronto, and Melbourne, held shares in both the Gaiety and the Adelphi, and later shared a half-lease of the Lyric and a part-lease of the Savoy.Footnote 97 Chappell published the music of the two biggest West End operetta successes, The Merry Widow and Lilac Time, and it was Chappell’s managing director, William Boosey, who bought the rights to the latter (Das Dreimäderlhaus) in Vienna and produced at the Lyric in partnership with Alfred Butt. He was unaware that another English-language version was already being performed on Broadway as Blossom Time.Footnote 98 In New York, the Shuberts were involved with two companies publishing sheet music.Footnote 99

The world of publishing was cosmopolitan, and an intermingling of personnel among the various houses was common. The brothers Max and Louis Dreyfus revived New York’s ailing firm of T. B. Harms in the early twentieth century and struck a partnership deal with London’s Francis, Day, and Hunter in 1908. Harms parted with Francis, Day, and Hunter in 1920 because Chappell did a deal with Louis and Max that allowed them to take over Chappell in New York, in return for Chappell’s taking over the Harms agency in London. Francis, Day, and Hunter then did a deal with Leo Feist in New York. Louis Dreyfus later became Managing Director of Chappell in London, while his brother Max took charge of Chappell in New York, which had Walter Eastman as Managing Director. Eastman then moved to London to take up the same position at Ascherberg, Hopwood & Crew.Footnote 100 The first manager of Chappell in New York (in 1891) had been George Maxwell, who went on to work for Ricordi in the USA. Chappell in New York had sufficient autonomy to pay $40,000 for the English rights to Lehár’s Eva in 1911.Footnote 101

Copyright law facilitated arrangements between publishers, so that, for example, Die Dollarprinzessin was available in Vienna from Karczag, in Berlin from Harmonie, and in English versions from Ascherberg, Hopwood & Crew in London, and Harms in New York. The tightening of copyright law and the tougher penalties for infringement had dealt a blow to piracy. Publishers no longer felt the need to introduce heavily discounted editions to combat piracy, although that policy had tended to affect single songs, rather than vocal scores. In fact, the price of vocal scores remained stable for many years: from 1910–30 the typical cost would be 6 shillings (or 8 shillings, cloth bound) in the UK and $2 (or $2.50, cloth bound) in the USA. Individual songs were usually two shillings in the UK and sixty cents in the USA. Covers were generally pictorial, being designed to catch the eye of the customer (Figure 3.3). There were lots of arrangements of operetta for other media platforms, recital rooms, dance halls, park bandstands, and so forth (see Chapter 6).

Figure 3.3 Front cover of the vocal score of The Count of Luxembourg, published in 1911.

Theatre and Fashion

An easily forgotten attraction of operetta is costume, which fed into fashion and consumerism on the High Street. Leading fashion designers were involved with operetta, from Lucile and The Merry Widow in 1907, to Norman Hartnell and Paul Abraham’s Viktoria and Her Hussar in 1931. One of the most admired costume designers of the early twentieth century was Attilio Comelli. Alongside his work as house designer of the Royal Opera House from the late 1880s to the early 1920s, he was responsible for a number of costumes for operettas at Daly’s Theatre.Footnote 102

Lucile acknowledged that the hat she created for Lily Elsie to wear in the London production of The Merry Widow ‘brought in a fashion which carried the name of “Lucile” … all over Europe and the States’ (Figure 3.4).Footnote 103 The ‘Merry Widow’ hat kept increasing in width and, by Spring 1908, there were versions available with spans of three feet or more.Footnote 104 Lucile was a prominent fashion designer, whose formal name in London society was Lady Duff Gordon. She claimed to have invented the fashion show with the ‘mannequin parades’ held at her London shop.Footnote 105 Her career was nearly cut short when she booked a trip on the Titanic in April 1912, but she was fortunate to be one of the survivors, and was back in October designing Shirley Kellogg’s dresses for Kálmán’s The Blue House at the London Hippodrome.Footnote 106

Figure 3.4 Lily Elsie as Sonia, wearing the ‘Merry Widow’ hat, from The Play Pictorial, vol. 10, no. 61 (Sep. 1907).

The stage acted as a shop window for costume design. The Times commented that Lily Elsie, as the merry widow, made ‘an unusually beautiful picture in Parisian and Marsovian dresses’,Footnote 107 and, regarding The Count of Luxembourg at Daly’s, informed readers that the ‘accessories in dresses and wearers of dresses were as sumptuous as ever’.Footnote 108 In an age of conspicuous consumption, the spectacle of glamorous costume was an enticement to the purchase of similar garments that would function as a display of status.Footnote 109 The Play Pictorial was sure to carry photographs of the costumes worn. It gave a detailed description of the Lily Elsie’s gown as the bride, hidden from the Count of Luxembourg’s view by a screen (see Figure 3.5):

Most elaborately embroidered in silver and white, the lower part was a cascade of silver bugle fringes and little crescents of pink and blue flowers peeping in and out around the hem of the skirt. There seemed to be two or three transparent skirts, the overdress, just giving a tantalizing glimpse where it opened at the side.Footnote 110

The cost of such gowns is rarely mentioned but high prices were involved. José Collins documented that the white gown she wore in the second act of Sybil (1921) was designed by Reville and cost £1000 (the equivalent commodity value of around £42,000 or $54,000 in 2017). It was covered in feathers, each set with an emerald.Footnote 111

Fashion was not of interest only to women. Men began taking notice when, in musical comedies of the 1890s, smart suits replaced the formerly eccentric clothes given to male characters. George Grossmith Jr, who performed in musical comedy and operetta before becoming a producer, acquired a reputation as ‘an acknowledged fashion leader’.Footnote 112 Sometimes a cynical eyebrow was raised at costumes: of the lavish production of A Waltz Dream, the Times reviewer declared, ‘At no Court in the world, least of all that of a German prince, do they wear so many spangles’.Footnote 113

Costume continued to be an attraction in the 1930s, when Theodor Adorno remarked that the fashionable dresses he saw around him in Frankfurt appeared to have been stolen from operettas.Footnote 114 In London, the dresses designed by Professor Ernst Stein for White Horse Inn at the Coliseum created a sensation.Footnote 115 A eulogy appeared on The Times ‘London Fashions’ page:

The greatest dress spectacle of all is White Horse Inn, in which the unending change of scene provides a wonderful grouping of colours … In this production constant use is made of greens, reds, yellows, and blues, and also of brown, a colour not much in favour with producers but which is introduced with excellent effect in the skirts of the women and the suits of the men.Footnote 116

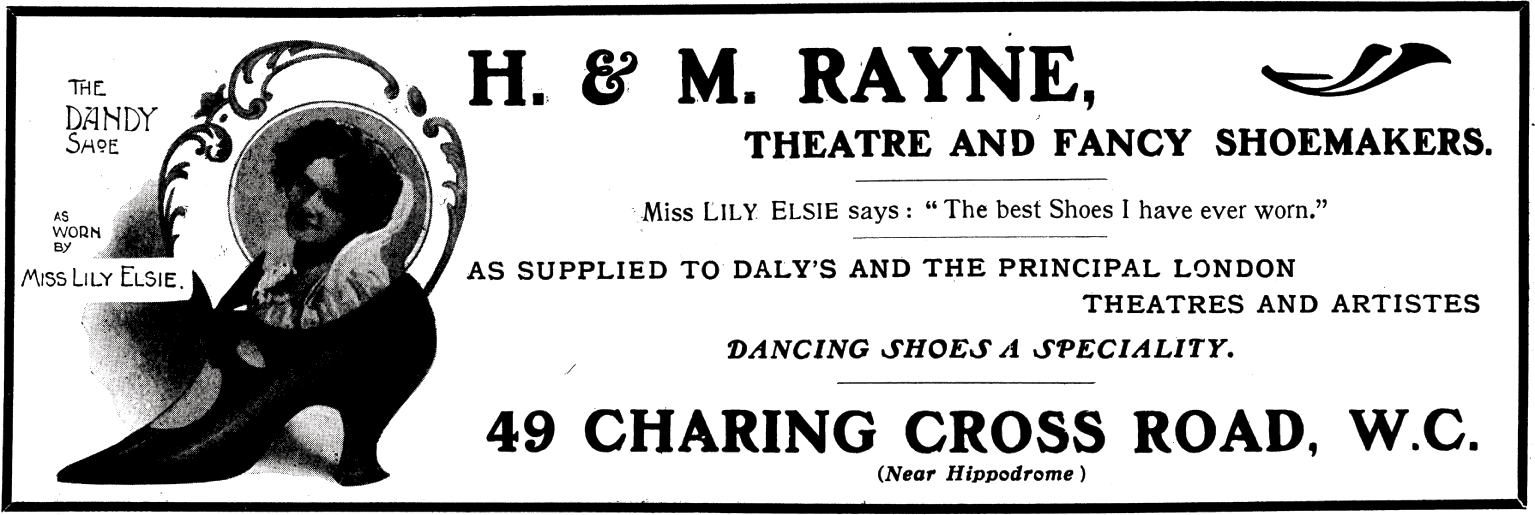

It was not only the frocks and suits that caught the eye but also hats and shoes. Gamba advertised that their shop on Shaftesbury Avenue sold the sandal shoes supplied for the production of White Horse Inn.Footnote 117 H. & M. Rayne of Charing Cross Road had boasted back in 1907 that they supplied shoes to the principal theatres of London. They also knew the value of an endorsement from a star (Figure 3.6). Women operetta stars were often called upon, for an appropriate fee, to appear in advertisements endorsing a variety of commodities related to the body, from corsets to cosmetics.

Figure 3.6 Advertisement for Rayne shoes, The Play Pictorial, vol. 10, no. 61 (Sep. 1907).

In New York, the Shuberts ran an in-house design company for their stage costumes, and made frequent use of a dozen designers, among whom Cora MacGeachy and Homer B. Conant were most prominent.Footnote 118 This side of the Shuberts’ interests was picked up by the reviewer of Fall’s The Rose of Stamboul in 1922:

This is the newest of those large-scale entertainments – part operetta, part burlesque show and part fashion parade – which the Shuberts have fallen into the habit of staging at the Century.Footnote 119

Costume was not only a matter for the stage. The foyers and auditoriums of West End and Broadway theatres were spaces where members of an audience could flaunt their fashionable dress and social standing. As Thorstein Veblen remarked in his Theory of the Leisure Class, money spent on clothes has an advantage over other methods of expenditure for display, in that ‘our apparel is always in evidence and affords an indication of our pecuniary standing to all observers at the first glance’.Footnote 120

Merchandizing

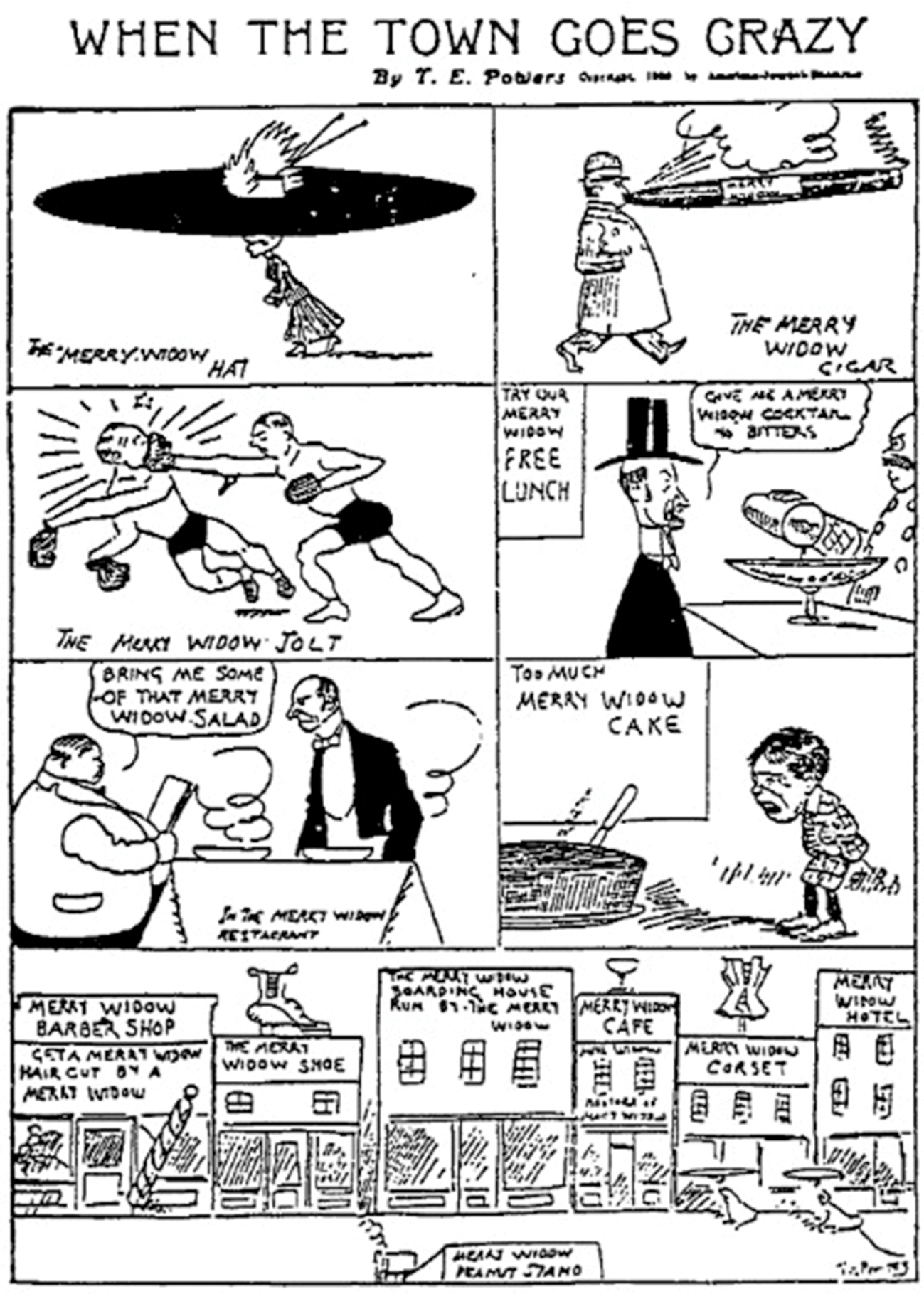

Operetta could be used to promote sales of various goods by coordinating its production with media advertising and other sales strategies that fall under the general classification of merchandizing. Stars provided many opportunities for this practice, for example, as images on picture postcards, cigarette cards, and sheet music title-page lithography. The manufacture and marketing of operetta is linked in Adorno’s mind with modern consumerism, and he likened the success of Die lustige Witwe to that of the new department stores.Footnote 121 In the UK, as in the USA, the success of this operetta led to merchandizing on a huge scale, including ‘Merry Widow’ hats (of broad width), chocolates, beef steaks, a ‘Merry Widow’ sauce, and even a corset.Footnote 122 A cartoon in The Evening American satirizes the craze for products carrying the ‘Merry Widow’ brand (Figure 3.7). The impact of the ‘Merry Widow’ brand was seen to extend beyond the world of merchandizing, when Sonia, the title character’s name in the English version, became popular for baby girls.Footnote 123

Stage Photography and Theatre Periodicals

Foulsham and Banfield, the most admired firm of stage photographers in London, made at least £600 out of press pictures of The Merry Widow.Footnote 124 They also launched the craze for picture postcards of star performers. In the early twentieth century, the market for postcards bearing a photograph of a celebrity grew enormously. Phyllis Dare claims to have signed between 75,000 to 100,000 picture postcards during 1904–7, years in which she was still in her teens (Figure 3.8).Footnote 125 In New York, two of the most frequent firms involved in stage photography during this period were the White studio, which developed the flash pan and flare for this kind of work, and the Vandamm organization.Footnote 126 Wide-range shots were generally taken at dress rehearsal.Footnote 127

Photographs were also a prominent feature of the theatre periodicals, such as The Play Pictorial and Theatre World in London, and Theatre Magazine and Dramatic Mirror in New York. Theatre magazines sold in large numbers, especially if there was a production gaining special attention. For the issue of Play Pictorial concentrating on The Count of Luxembourg, 50,000 copies were ordered from the printer, as well as 1000 additional copies of the coloured cover illustration.Footnote 128 There was also a market for books about the lives of theatre stars. Phyllis Dare wrote her autobiographical From School to Stage (with the assistance of Bernard Parsons) at the remarkably young age of 17. The term ‘stars’ was being used regularly in the first decade of the century to describe well-known and admired performers. At this time, it was often enclosed in quotation marks, indicating its colloquial usage.Footnote 129

Agencies, Associations, and Entrepreneurs

A variety of agents was involved in the promotion of operetta. There were advertising agents, such as the Theatrical and General Advertising Company, which, by the 1930s, became the sole agent for advertising in the programmes of the major West End theatres (with the exception of the Savoy). There were publishers acting as agents for other publishers: Ascherberg, Hopwood & Crew, for example, relied on the agency of Chappell for the sale and distribution of their publications in Australia and New Zealand. Most importantly, there were entrepreneurial agents involved in the selling of rights. After marrying the widow of Felix Bloch, publisher and manager of a Berlin theatrical agency, Adolf Sliwinski [Śliwiński] built an international reputation by handling the rights to Die lustige Witwe and many other operettas. William Boosey, who, as previously mentioned, was Chappell’s managing director, pressed George Edwardes to secure the English rights to The Merry Widow from Sliwinski, after having persuaded Edwardes to go with him to Vienna to hear this operetta.Footnote 130 The English version was then published by Chappell. The Bloch agency, which also had Leo Fall and Oscar Straus on its list, dominated the German operetta market, and dealt with English rights through its London office. There was a little competition from others, such as Karczag in Vienna. Lehár joined the latter after falling out with Felix Bloch, but when Karczag went into liquidation in 1935, he founded his own press, Glocken Verlag. It was an act of vertical integration that allowed him to take control of both the production and distribution of his music. Glocken Verlag later became affiliated to Josef Weinberger’s publishing house.

In Berlin, Fritz and Alfred Rotter were among the most important contacts for foreign entrepreneurs after the death of Sliwinski in 1916.Footnote 131 The Rotter brothers, who ran the Metropol Theater, were always good at spotting a potential success. After the enthusiastic reception of Abraham’s Viktoria und ihr Husar at the July 1930 operetta festival in Leipzig, they lost no time in producing it at the Metropol. Unfortunately, they became a casualty of the Great Depression, and their theatre empire ended in bankruptcy. An arrest warrant was issued against them on 22 January 1933.Footnote 132 The Rotters took off for Liechtenstein, but soon found, being Jewish, they had not escaped Nazi persecution.Footnote 133 Alfred Rotter and his wife died in a car crash in highly suspicious circumstances while being pursued in the mountains of Liechtenstein in April 1933.

The Theatrical Syndicate was formed in New York in 1896 by Abraham Erlanger, Marc Klaw, Charles Frohman, and Al Hayman to centralize the booking system, but then began to control theatres by dictating terms. In 1909 the Theatre Managers’ Association was founded at Erlanger’s New Amsterdam Theatre.Footnote 134 Unsurprisingly, Erlanger was chosen President. Some important figures, such as Henry W. Savage, President of the National Association of Producing Managers, began to rebel against Erlanger’s dominance, and irritation grew on the part of Sam Shubert (a committee member of the Theatre Managers’ Association).Footnote 135 In 1919, Klaw sold his theatre interests to the Shuberts, after splitting with Erlanger, and this forced the latter to join the Shubert controlled United Booking Office.Footnote 136

Charles Frohman’s theatrical entrepreneurship was not limited to the USA; he was a theatre manager in London, having leased the Duke of York’s Theatre in 1897. A few years later, he was involved with the building of the Aldwych and Hicks’s Theatres, both for Seymour Hicks. The latter said of him that nobody ever produced plays ‘with so little thought of the financial side of their success’.Footnote 137 When visiting London, Charles Frohman travelled on the Lusitania, a luxury ocean liner, with wireless telegraph and electric lighting, launched by Cunard in 1906 as part of an effort to challenge the German dominance of transatlantic travel. It had a speed of 29 miles per hour (25 knots) – four miles an hour faster than the SS Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse. It made a total of 202 transatlantic crossings before being sunk by a torpedo from a German submarine on 7 May 1915, killing 1198 passengers and crew. Frohman was among those who died.

In the early 1930s, impresario Stanley H. Scott specialized in the import of German stage entertainments into the West End. It was Scott who first brought Tauber to the UK, although he was relatively inexperienced in theatrical production at that time. Tauber was to appear in the West End premiere of The Land of Smiles, and this helped Scott win the consent of George Grossmith, general manager of Drury Lane, to produce the operetta there in May 1931. The theatre had not been faring too well since producing the Broadway successes Rose-Marie and The Desert Song. It was a time of economic depression, and the previous manager, Alfred Butt,Footnote 138 had left earlier in 1931. Unfortunately, the production of The Land of Smiles was blighted by Tauber’s recurring throat problems. Scott had more success with Maschewitz and Mackeben’s revision of Millöcker’s Gräfin Dubarry, which he brought to His Majesty’s Theatre as The Dubarry the following year. Yet, once again, its star performer, Anny Ahlers, was the cause of its closing before time. Performers form a significant part of the subject matter of Chapter 4, and both Tauber’s throat trouble and the death of Ahlers are discussed there. In addition, the activities of stage directors and stage designers receive attention. A little overlap with the present chapter is inevitable, however, given that some entrepreneurs and managers also took part in directing.Footnote 139