1. Introduction

In the 25 years since the publishing of Edge and Richards’ (Reference Edge and Richards1998) landmark discussion of epistemological claims in qualitative applied linguistics research, the volume of published qualitative studies in language education has notably increased (Benson et al., Reference Benson, Chik, Gao, Huang and Wang2009; Lazaraton, Reference Lazaraton2000; McKinley, Reference Mckinley2019; Richards, Reference Richards2006, Reference Richards2009; Zhang, Reference Zhang2019). Within the context of the methodological turn in language education (Plonsky, Reference Plonsky2013), it has become more important than ever for authors, readers, and stakeholders of such research to be able to judge its quality. Assessments of study quality determine whether manuscripts submitted to academic journals are put forward for review (Mahboob et al., Reference Mahboob, Paltridge, Phakiti, Wagner, Starfield, Burns, Jones and De Costa2016) and are central to the peer review process itself (Marsden, Reference Marsden and Chapelle2019). They also play an important role in institutional decision-making concerning what is researched as well as the allocation of funding (Chowdhury et al., Reference Chowdhury, Koya and Philipson2016; Pinar & Unlu, Reference Pinar and Unlu2020). Furthermore, there is a continuing need for qualitative researchers to foreground evidence and claims of legitimacy to counter misconceptions about the concept of good/bad or strong/weak qualitative research and questions about clearly defined criteria for judging its quality that can render the value of such research uncertain (Hammersley, Reference Hammersley2007; Mirhosseini, Reference Mirhosseini2020; Morse, Reference Morse, Denzin and Lincoln2018; Shohamy, Reference Shohamy2004).

Like any sensible process of inquiry, ‘good’ qualitative research should be ‘timely, original, rigorous, and relevant’ (Stenfors et al., Reference Stenfors, Kajamaa and Bennett2020, p. 596), make explicit the grounds on which authors claim justification for their findings (Edge & Richards, Reference Edge and Richards1998), and offer sensitive and careful exploration (Richards, Reference Richards2009). It should be shaped by taking the relevant and appropriate research path, making principled and defensible decisions about aspects of data collection and analysis, generating logical inferences and interpretations, and gaining meaningful insight and knowledge (Mirhosseini, Reference Mirhosseini2020). How qualitative research is communicated necessitates equivalent flexibility, demanding that the research report be engaging, significant, and convincing (Skinner et al., Reference Skinner, Edwards and Smith2021; Tracy, Reference Tracy2010, Reference Tracy2020). Yet, how this is executed in empirical language education research has not yet been examined, unlike in other disciplines (e.g., Raskind et al., Reference Raskind, Shelton, Comeau, Cooper, Griffith and Kegler2019). Therefore, in this meta-research study, we adopt a qualitative approach to examine conceptions of research quality embedded in a sample of qualitative language education articles published in major journals of the field over the past two and a half decades. Specifically, we address the following research question: How do authors of these qualitative studies explicitly attend to quality concerns in their research reports? By gaining greater understandings of how language education scholars foreground quality considerations in qualitative research, we hope to identify opportunities for enhancing how such research is perceived across the field through strengthening our collective methodological toolkit.

1.1 Conceptions of quality in qualitative research

Qualitative research is characterised by its social constructivist epistemological essence (Kress, Reference Kress2011; Pascale, Reference Pascale2011) realised through various methodological traditions and approaches (Creswell, Reference Creswell2007; Flick, Reference Flick2007). The issue of quality in qualitative inquiry has, therefore, been interconnected with diverse understandings of such epistemological and methodological perspectives. Developments in the concern for qualitative research quality can, by some accounts, be divided into different phases across the wider general literature (Morse, Reference Morse, Denzin and Lincoln2018; Ravenek & Rudman, Reference Ravenek and Rudman2013; Seale, Reference Seale1999). Initially (and ironically continuing to this day as a significant stream), authors of social research within language education and beyond have employed terms developed within the positivist scientific and quantitative tradition, notably validity and reliability (Kirk & Miller, Reference Kirk and Miller1986; Long & Johnson, Reference Long and Johnson2000; Mirhosseini, Reference Mirhosseini2020). Under criticisms from interpretive epistemological orientations, new terms specific to qualitative research (e.g., dependability, transferability) were spawned in the 1980s and 1990s (Lincoln & Guba, Reference Lincoln and Guba1985; Seale, Reference Seale1999), sometimes framed as fixed and direct equivalences of quantitative concepts (e.g., Noble & Smith, Reference Noble and Smith2015) or tied to particular paradigms/methodologies (Creswell, Reference Creswell2007).

Consequently, the literature is now replete with concepts posited for judging qualitative study quality (e.g., Edge & Richards, Reference Edge and Richards1998; Lincoln, Reference Lincoln, Atkinson and Delamont2011; Seale, Reference Seale1999, Reference Seale, Atkinson and Delamont2011; Tracy, Reference Tracy2010), ranging from widely used terms such as credibility, dependability, and reflexivity (Lincoln & Guba, Reference Lincoln and Guba1985; Miles & Huberman, Reference Miles and Huberman1994), to ideas that seem to have garnered less traction, including, perspicacity (Stewart, Reference Stewart1998), emotional vulnerability (Bochner, Reference Bochner2000), and resonance (Tracy, Reference Tracy2010). This variety poses difficulties for novice qualitative researchers (Roulston, Reference Roulston2010) and for reviewers of studies submitted to academic journals as well as the audience of qualitative research reports in general. Since no paper, to the best of our knowledge, has explored which particular quality concepts have cascaded down to language education, or the extent to which they vary in prevalence across empirical qualitative studies, there is likely uncertainty (particularly among early career qualitative researchers), over which concepts to foreground in research papers and how.

Inevitably, quality conceptions in qualitative research have amalgamated into frameworks for making claims of and evaluating study worth (e.g., Denzin & Lincoln, Reference Denzin and Lincoln2005; Lincoln & Guba, Reference Lincoln and Guba1985; Morse et al., Reference Morse, Barrett, Mayan, Olson and Spiers2002; Patton, Reference Patton2002; Richardson, Reference Richardson2000; Skinner et al., Reference Skinner, Edwards and Smith2021; Spencer et al., Reference Spencer, Ritchie, Lewis and Dillon2003; Stewart, Reference Stewart1998; Tracy, Reference Tracy2010, Reference Tracy2020). Perhaps the most famous of these is Lincoln and Guba's (Reference Lincoln and Guba1985) notion of trustworthiness, composed of four discernible components: credibility, dependability, transferability, and confirmability. To these, the concept of reflexivity is often added (e.g., Richardson, Reference Richardson2000; Stenfors et al., Reference Stenfors, Kajamaa and Bennett2020), although some see reflexivity as a means of ensuring research findings are credible and confirmable. Such criteria reflect features of how research is conducted (e.g., prolonged engagement, member checking), reported (thick description), or a combination of both (reflexivity, methodological transparency). Consequently, quality in qualitative research can be discerned both from authors' descriptions of how the study was designed and conducted as well as their explicit accounts of how quality was attended to, typically in the methodology section of research articles (Marsden, Reference Marsden and Chapelle2019; Stenfors et al., Reference Stenfors, Kajamaa and Bennett2020). This complexity is, for instance, reflected in the eight ‘big tent’ quality criteria proposed by Tracy (Reference Tracy2010), which encompass design features that authors may need to present explicitly (e.g., time in the field, triangulation), along with more nebulous characteristics inherent to the framing and reporting of the study (research relevance/significance).

Evaluative criteria, which may illuminate how ‘good’ qualitative research is conducted and reported, are being increasingly adopted by academic publications (Korstjens & Moser, Reference Korstjens and Moser2018; Richards, Reference Richards2009; Rose & Johnson, Reference Rose and Johnson2020). Yet, the prevailing view held by qualitative scholars from a social constructivist standpoint (Kress, Reference Kress2011), that we would align ourselves with, is that the idea of foundational criteria (i.e., fixed and universal) against which the quality of qualitative research can be judged is flawed (Barbour, Reference Barbour2001; Hammersley, Reference Hammersley2007; Lazaraton, Reference Lazaraton2003; Richards, Reference Richards2009; Shohamy, Reference Shohamy2004; Tracy, Reference Tracy2020). Evaluative criteria for any form of research are underscored by value judgements that shape different research approaches and methods, how and where the results are reported, and who ‘good researchers’ are (Lazaraton, Reference Lazaraton2003). Calcifying good practice into immovable criteria is considered fundamentally at odds with the guiding philosophy of qualitative research (Bochner, Reference Bochner2000; Pascale, Reference Pascale2011; Shohamy, Reference Shohamy2004), which stresses creativity, exploration, conceptual flexibility, and freedom of spirit (Seale, Reference Seale1999). Furthermore, as Tracy (Reference Tracy2010) highlights, notions such as quality, like any social knowledge, are not temporally or contextually fixed.

As such, dialogues of what constitutes effective qualitative research should be considered as unresolved. Indeed, the prevailing postmodern turn has ripped apart the notion of agreed criteria for good qualitative research (Seale, Reference Seale1999), leading some authors to adopt anti-foundational perspectives (e.g., Bochner, Reference Bochner2000; Shohamy, Reference Shohamy2004), albeit rejecting shared notions of ‘good’ research risks undermining the credibility and relevance of qualitative research (Flick, Reference Flick2009). Within this complex climate, a moderate practical position is sometimes adopted in different fields including language education (Chapelle & Duff, Reference Chapelle and Duff2003; Mahboob et al., Reference Mahboob, Paltridge, Phakiti, Wagner, Starfield, Burns, Jones and De Costa2016). It tends to balance the need for agreement over what constitutes ‘goodness’ in qualitative research and respecting authors’ desire for interesting, innovative, and evocative research based on their sociopolitical agendas (Bochner, Reference Bochner2000; Lazaraton, Reference Lazaraton2003; Spencer et al., Reference Spencer, Ritchie, Lewis and Dillon2003). On this basis, in research reporting, there is an expectation that authors both implicitly and explicitly attend to study quality, albeit research articles in language education, as elsewhere, are subject to (often restrictive) publication word limits (Marsden, Reference Marsden and Chapelle2019).

1.2 Quality in qualitative language education research

Increasing scholarly attention is being paid to matters of quality in qualitative language education research, usually through chapters in books dedicated to qualitative research in the field more broadly (see Mirhosseini, Reference Mirhosseini2020; Richards, Reference Richards2006) and theoretical reviews/perspective pieces (Davis, Reference Davis1992, Reference Davis1995; Duff & Bachman, Reference Duff and Bachman2004; Holliday, Reference Holliday2004; Johnson & Saville-Troike, Reference Johnson and Saville-Troike1992; Mirhosseini, Reference Mirhosseini2018; Shohamy, Reference Shohamy2004), as well as occasional journal guidelines for authors of prospective manuscripts (Chapelle & Duff, Reference Chapelle and Duff2003; Mahboob et al., Reference Mahboob, Paltridge, Phakiti, Wagner, Starfield, Burns, Jones and De Costa2016). The latter are particularly salient for the present study since they constitute both a set of evaluative criteria on conducting and reporting qualitative research in language education, as well as addressing how and why it is important for researchers to attend to quality. In several instances, such features overlap, as in this instance from TESOL Quarterly: ‘Practice reflexivity, a process of self-examination and self-disclosure about aspects of your own background, identities or subjectivities, and assumptions that influence data collection and interpretation’ (Chapelle & Duff, Reference Chapelle and Duff2003, p. 175).

For the purposes of author and reviewer clarity, Chapelle and Duff's (Reference Chapelle and Duff2003) guidelines are wedded to discrete, fixed depictions of research methodologies. Their original iteration outlined quality considerations for case studies and ethnographic research, with a clear epistemological distinction between qualitative and quantitative research, highlighting (perhaps unnecessarily) paradigmatic divisions (Bochner, Reference Bochner2000; Shohamy, Reference Shohamy2004). More recently (Mahboob et al., Reference Mahboob, Paltridge, Phakiti, Wagner, Starfield, Burns, Jones and De Costa2016), this distinction has been revisited, likely out of recognition that, for the purpose of comprehensiveness, researchers increasingly gather data drawing on both paradigmatic traditions (Hashemi, Reference Hashemi2012, Reference Hashemi, McKinley and Rose2020; Hashemi & Babaii, Reference Hashemi and Babaii2013; Mirhosseini, Reference Mirhosseini2018; Riazi & Candlin, Reference Riazi and Candlin2014). In terms of quality concepts, Mahboob et al.'s (Reference Mahboob, Paltridge, Phakiti, Wagner, Starfield, Burns, Jones and De Costa2016) guidelines are orientated towards rich rigor and credibility. Regarding the former, they advise ethnographers to show evidence of ‘residing or spending considerable lengths of time interacting with people in the study setting’ and ‘triangulation’, and to ‘practice reflexivity’ (p. 175). It also informs qualitative researchers to triangulate ‘multiple perspectives, methods, and sources of information’ and employ illustrative quotations that highlight emic (i.e., participant) ‘attitudes, beliefs, behaviors, and practices’ (p. 175). They illustrate such principles through sample studies, albeit it might be argued that this practice further serves to narrow research into fixed acceptable forms followed prescriptively by would-be scholars in a bid for successful publication.

2. Method

2.1 Data retrieval

Although this study is qualitative in nature, our first step was similar to other reviews of research in the field (e.g., Lei & Liu, Reference Lei and Liu2019; Liu & Brown, Reference Liu and Brown2015), that is, determining a principled, representative, and accessible domain of empirical research for the investigation of study quality. We decided to include only academic journal papers in the dataset, based partly on the assumption, also held elsewhere (e.g., Plonsky & Gass, Reference Plonsky and Gass2011), that journals constitute the primary means of disseminating high-quality empirical language education research. We also thought that comparisons of study quality would be more meaningful within a single publication format, instead of bringing in longer formats (e.g., books, theses), where authors have significantly greater scope for ruminating on matters of study quality. Furthermore, empirical studies presented in book chapters were excluded on the grounds that the final set of included studies would have been unbalanced, being heavily skewed towards journal articles (Plonsky, Reference Plonsky2013). We then consulted several meta-research studies in the field as sources of reference for selecting high-quality language education research journals while we were conscious that the nature of our analysis would be different from those mostly quantitative studies (e.g., Lei & Liu, Reference Lei and Liu2019; Plonsky, Reference Plonsky2013; Zhang, Reference Zhang2019). We decided not to include specialist journals (such as Applied Psycholinguistics, Computer Assisted Language Learning, Studies in Second Language Acquisition), as well as journals that do not typically publish primary research (ELT Journal). Our final selection included seven venues renowned for publishing robust primary research in language education: Applied Linguistics, Foreign Language Annals, Language Learning, Language Teaching Research, Modern Language Journal, System, and TESOL Quarterly.

Informed by prior literature (e.g., Thelwall & Nevill, Reference Thelwall and Nevill2021), and with reference to various theoretical discussions of quality in qualitative research (discussed earlier in this article), we devised a series of inclusionary search terms (such as qualitative, narrative, ethnography, phenomenology, and grounded theory; with possible additional lemmas) to generate a representative sample of empirical qualitative research. The terms were applied to the title, keyword, and abstract fields in Scopus to determine and retrieve a more consistent body of results (rather than querying the different journal publishers directly). Such an approach naturally hinges on authors explicitly positioning their study as, say, ‘qualitative’ or ‘ethnographic’, which in light of the diversity and complexity of ways to communicate research, we acknowledge as a limitation. Moreover, we did not include approaches that cut across paradigmatic traditions (such as feminist approaches and participatory action research).

Exclusionary terms (like quantitative, experiment, statistic, mixed method, and control group; with possible additional lemmas) were applied to reduce the size of the sample and the amount of manual checking required to eliminate irrelevant studies. To obtain an indicative body of recent and older qualitative research, we decided the publication period of the included studies to be between 1999 and 2021 and chose the year 1999 as a cut-off owing to the publication of Edge and Richards’ (Reference Edge and Richards1998) seminal work on knowledge claim warrants in applied linguistics research. We should also add that this meant that more recently established journals that publish qualitative research (such as Critical Inquiry in Language Studies and Journal of Language, Identity and Education) could not be included. Additional filters in Scopus were applied to the results, removing works not written in English and those not labelled by Scopus as ‘articles’, and limiting article versions to ‘final’ rather than ‘in press’.

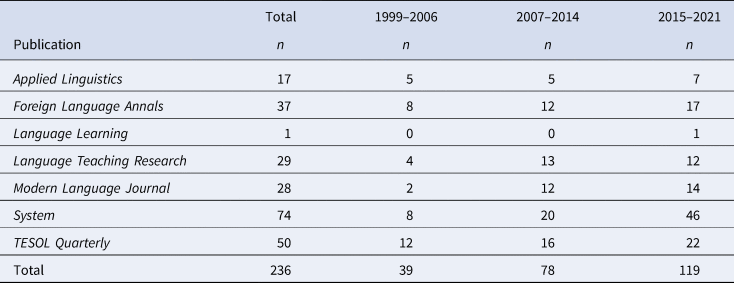

Search processes generated records for 741 studies, the bibliometric records for which were downloaded and imported into Excel. With the articles arranged chronologically and then alphabetically by publication, every alternate record was excluded for the purposes of further reducing the sample. Article abstracts were then manually checked by the researchers to ensure each entry constituted qualitative research. Uncertainty was addressed through retrieval and verification of the article's full text involving, when necessary, discussion between the researchers. At this stage, 134 studies were eliminated primarily because they encompassed mixed methods, were not in fact qualitative, or did not constitute an empirical study. As shown in Table 1, the studies were not evenly distributed across journals or timeframe. The majority of research studies (56%) constituted single-author works, followed by 35% for two-author, and 8% for three-author works. Full texts for the final sample of 236 studies were retrieved directly from the journal publishers as PDFs and imported into NVivo 12 for data analysis by both researchers.

Table 1. Distribution of the included studies

2.2 Data analysis

In order to explore how the authors of the retrieved reports addressed matters of study quality, we chose to conduct qualitative content analysis of texts’ manifest content (Mayring, Reference Mayring2019; Schreier, Reference Schreier and Flick2014), that is, statements rather than implied between-the-lines meanings (see, Graneheim & Lundman, Reference Graneheim and Lundman2004). Although this approach may in a sense be a limitation of our analysis, it was adopted because we were interested in how the authors themselves explicitly addressed and positioned quality in their research. Additionally, we found it difficult to analyse texts latently without (a) encountering notable uncertainty whether information was being included for the purposes of quality claims (or not), and (b) taking an explicitly evaluative position towards research (including on ‘under the hood’ design issues that we were clearly not equipped to comment on).

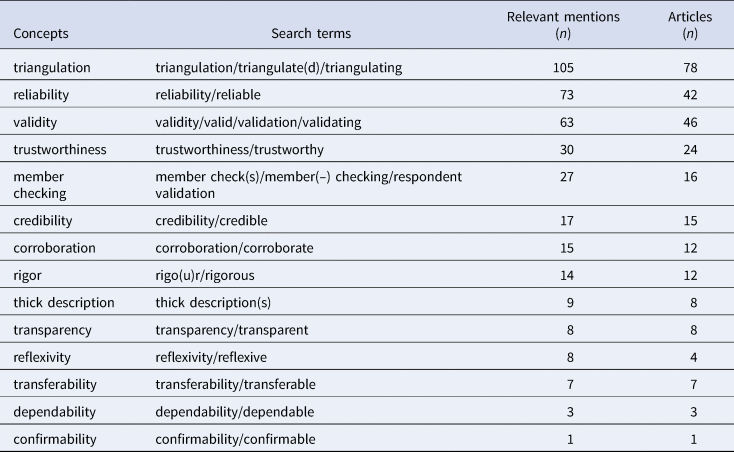

We limited the scope of manifest content to a discrete array of quality concepts synthesised across various frameworks developed for qualitative research (mainly including Denzin & Lincoln, Reference Denzin and Lincoln2005; Edge & Richards, Reference Edge and Richards1998; Mirhosseini, Reference Mirhosseini2020; Richardson, Reference Richardson2000; Spencer et al., Reference Spencer, Ritchie, Lewis and Dillon2003; Stewart, Reference Stewart1998; Tracy, Reference Tracy2010), outlined in Table 2. The two terms validity and reliability, while not concepts interpretive researchers would recognise as epistemologically appropriate to apply to qualitative research, were included since much qualitative research still makes references to these notions (as indicated in our sample in Table 2). It was not feasible to incorporate qualitative concepts that could be linguistically operationalised in very diverse ways, such as prolonged engagement, evocative representation, and contextual detail, which we acknowledge somewhat reduces the nuance of the analysis. We should also mention that the terms member reflection and multivocality were included in the search process but generated no hits and are thus excluded from the search results.

Table 2. Quality concepts investigated in the retrieved literature

Article full texts were searched in NVivo for lemma forms of the identified concepts (provided in Table 2). We captured concepts within their immediate textual surroundings, which we delineated as our meaning units for the present study (Graneheim & Lundman, Reference Graneheim and Lundman2004), using NVivo's ‘broad context’ setting to ensure we could analyse authors’ sometimes lengthy descriptions and explanations. The textual extracts that included the 801 mentions of the different variants of the search terms were exported into Word files for manifest content analysis (Graneheim & Lundman, Reference Graneheim and Lundman2004). Initially, the extracts were subject to cleaning to (a) attend to instances where the contextual information either preceding or following the quality concept was missing and to manually amend them, (b) remove the relatively large number of occurrences that did not refer to research quality but were used in a general sense of the word (prevalent with the terms, validity, reliability, credibility, reflexivity, transparency, rigor, and corroboration), and (c) exclude examples where lemma constituted a heading or cited source title. We then coded the clean data (overall 380 instances of the search terms, as seen in Table 2) for each keyword in turn with short labels that aligned with the express surface-level meaning conveyed by the authors. Together, we looked for meaningful patterns across codes (within discrete keywords) that could be constellated into themes, paying attention to the need for both internal homogeneity and external heterogeneity (Patton, Reference Patton2002). The final ten themes emerging from our data are presented in the next section along with quoted extracts from the articles that are provided to illustrate claims, although we refer to authors and articles using a numbered system to establish a degree of anonymity.

As for our own study, we attended closely to its quality based on an interpretive epistemological view. Given the nature of the data and the approach to the analysis of manifest article content, reflexivity was a particularly significant consideration of ours. We were cognizant of our subjectivities and our own positions as researchers in the field with regard to the work of fellow researchers and the possibilities and limitations of expressing issues of quality within the limits of journal articles, hence our decision (and, in a sense, struggle) to stay focused on the manifest content of explicit propositions about research quality in the examined articles rather than reading between-the-line latent content (Graneheim & Lundman, Reference Graneheim and Lundman2004). Moreover, through our constant exchange of ideas and discussion of disagreements and differences of interpretation about realisations of quality concepts in these articles, we practiced our customised conceptions of researcher triangulation and corroboration. We also consciously provided as much detailed description of our data retrieval and analytical procedures as possible and tried to transparently reflect them in our writing, hoping that this will all add up to a rigorous inquiry process to the highest extent meaningful in a qualitative study.

3. Findings

3.1 Triangulation

Triangulation (as the most frequent term related to qualitative research quality) in the examined texts primarily referred to the mere collection of multiple types of data. Applying it as a well-known set of procedures, most researchers appear not to find it necessary to specify how triangulation was undertaken or how it enhanced research quality. They often only describe how they used ‘varied sources’ [671], ‘multiple collection methods’ [657], or ‘thick data’ [137] to ‘ensure triangulation of the data’ [337] or ‘achieve an element of triangulation’ [717]. A diversity of data sources and data collection procedures are mentioned in the overall bulk of the examined articles, with no clear patterns in the types of data being triangulated: ‘participant observation, in-depth interviews with key informants, and the analysis of textual documents including field notes, teaching materials, and student assignments’ [369]; ‘questionnaires, think-aloud protocols, gaming journals, and debriefing interviews’ [137]; ‘policy documents, media reports, and academic papers’ [199]. The quotes below are examples of how this general conception of triangulation is reflected in our data:

• We triangulated the results from data obtained in various ways: the pre-departure questionnaires, semi-structured pre-departure interviews, field notes from naturalistic observations, reflective journals, and the semi-structured post-sojourn interviews … [455].

• The use of the various data-gathering techniques, including the self-assessment inventory, the think-aloud task, and the open-ended interviews, allowed for triangulation of the data collected [673].

There are also many articles that do hint at researchers’ views of how triangulation contributed to the quality of their research. A few of these articles referred to triangulation as a way ‘to ensure the trustworthiness’ [1 & 619], ‘to strengthen the rigour and trustworthiness’ [119], or to strive ‘for enhanced credibility’ [543] of their studies. However, the authors of most of this category of published works turned to traditional positivist terminology in this regard. They relied on triangulation, in their own words, ‘to address reliability’ [81], ‘to increase the validity of evaluation and research findings’ [321], or ‘to ensure the validity and reliability of the data and its analysis’ [337]. Helping with more profound insights into the data is a further specified role of triangulation, as reflected below:

• In order to ensure reliability and validity of the study, I employed several forms of triangulation … [553].

• The triangulation of inferences from session transcripts, interview transcripts, and field notes shed light on complex connections between learning and practice and on the rationale behind teachers’ instructional choices … [67].

Other perceptions of the role of triangulation are also found to underlie these published studies. By some accounts, it is a mechanism of testing and confirming researchers’ interpretations, as they use data from different sources for the purpose of ‘confirming, disconfirming, and altering initial themes’ [715] and in order to ‘confirm emergent categories’ [589] or ‘reveal and confirm or refute patterns and trends’ [227]. It is also relied on as a strategy ‘to minimize drawbacks’ [621] in data collection and analysis and ‘to avoid the pitfall of relying solely on one data source’ [119]. Accordingly, ‘the lack of triangulation of the findings through other instruments’ [569] is seen by some researchers a shortcoming or limitation of their research. Finally, a particularly intriguing image of the versatile notion of triangulation and its connection with researcher reflexivity is presented through the introduction of novel concepts in one of the studied articles: ‘our collaborative analytical process allowed us to triangulate inferences across our different stories, enhancing both believability and possibility’ [31].

3.2 Reliability

Reliability is the second most frequent term related to research quality in the body of data that we investigated. Unlike triangulation, that projects an understanding of research quality congruent with qualitative research epistemology and methodology, the frequency and nature of referring to reliability can raise questions about prevailing conceptions of qualitative research quality. Uses of this term depict either a rather broad and vague image of rigor and robustness of research or refer to the idea of consistency close to its traditional positivist conception, in some cases even indicated by numerical measures. Moreover, sometimes, the absence of any measures undertaken to ensure this kind of consistency is mentioned as a limitation and weakness of the reported study.

Relatively frequent mentions of reliability (in some cases along with the word ‘validity’) seem to be in a general sense as an equivalent to high quality and rigorous research: ‘By augmenting our perspectives … , we think we have increased the reliability of our diagnosis’ [729]; ‘all attempts have been made to minimize the effects of the limitations of the study to increase the validity, reliability … of the study’ [549]. In addition, authors of a few of the studied articles appear to subsume strategies like triangulation and member checking under an attempt to take care of reliability (and validity) in their purportedly qualitative studies. In one of these cases, member checking is said to have been done in follow-up interviews, but it is described as a ‘technique’ employed ‘to ensure the validity and reliability of the data and its analysis’ [337]. The quote below is a similar example:

• In order to ensure reliability and validity of the study, I employed … triangulation by collecting multiple sources of data … [and] a member check … [553].

Apart from such instances, reliability is most obviously used in relation to coding, featuring overtly positivist terminology. Authors of many of the examined articles describe how they conducted their qualitative data analysis in more than one round or by more than one person to ensure or strengthen ‘inter-coder reliability’ [155, 157, 173, 549] or ‘inter-rater reliability’ [21, 81]. Some of these articles link these attempts to broader research quality concepts like trustworthiness and rigor: ‘To increase trustworthiness, first, intercoder reliability was negotiated via researchers independently coding the data … ’ [51]; ‘Two researchers independently analyzed the data to enhance reliability and rigor … ’ [35]. More specifically, there are instances of providing numerical figures of ‘interrater agreement’ [153] or ‘inter-coder/interrater reliability’ [57, 415] in percentages. But what we find particularly significant and ironic is that in several articles, statistical measures like ‘Cronbach's Alpha Test for Reliability’ [721] and ‘Cohen's kappa’ [173, 391] are used to compute reliability in an explicitly quantitative sense. The following are two examples in a blunt statistical language:

• Cohen's Kappa coefficients were calculated to assess inter-coder reliability on each of the four categories: 0.84 (assessment context), 0.84 (assessment training experience) … , suggesting satisfactory intercoder reliability. [203].

• Reliability was computed by submitting the independent ratings of the two researchers to a measure of internal consistency. Cronbach's alpha coefficient was computed … [693].

Other than agreement on data coding, a few researchers consider increased reliability through other procedures and approaches like collecting multiple data sources and data triangulation: ‘drawing on data collected from multiple sources, allows useful comparisons across the multiple cases and increases reliability’ [449]; ‘For enhanced reliability, data were collected through multiple written sources’ [543]. With these conceptions of reliability and measures undertaken to calculate and ensure them, the absence of such measures is expectedly acknowledged by some researchers as shortcomings and limitations of their research. As an instance, one article suggests that findings ‘should be taken with a grain of salt’ [467] because ‘inter-rater reliability’ was not calculated. In other cases, ‘the reliability of the recall procedure’ is considered a ‘limiting factor’ [173], and ‘a larger sample size and integration of qualitative and quantitative methods’ is suggested as a way to provide findings ‘in a more valid and reliable way’ [569].

3.3 Validity

The term validity is used in a variety of senses in the examined body of studies. Among these generally vague conceptions, perhaps the broadest and most difficult to interpret is the use of the term to indicate a kind of internal validity roughly meaning robust research. Here is a typical example also quoted in the section on reliability: ‘ … all attempts have been made to minimize the effects of the limitations of the study to increase the validity, reliability, authenticity, as well as the ethics of the study’ [549]. Other than such general statements about attempts ‘to improve the reliability and validity’ [721] of research and to attain ‘greater validity’ [7], there are indications of different measures purportedly undertaken to enhance validity. A frequently mentioned procedure used for this purpose is triangulation, which is said to have been used to ‘increase’ [321], ‘ensure’ [337], ‘address’ [81], or ‘demonstrate’ [83] validity, or to ‘to retain a strong level of validity’ [563]. ‘Enhance’ is another word to be added to this repertoire, as seen in the following example:

• To enhance the internal validity of the study, a number of strategies and techniques were employed by the teacher-researcher. One such technique was the triangulation of multiple data sources … [609].

Little idea is provided in these cases about what the authors mean by validity and how they employed triangulation to boost it. The same is true about the employment of member checking for the purpose of validity. It is named in several articles as an adopted procedure for this purpose but it usually remains rather broad and vague: ‘member checks … helped increase the validity of my interpretations’ [369]; ‘various member checks were performed … as a means of further validating the data’ [321]; ‘member checking … strengthened the validity of the final analysis’ [251]. There are also a few even more difficult-to-interpret cases in which conducting multiple rounds of coding is stated as a mechanism of ensuring validity. Below are two examples, the first of which oddly refers to the notion ‘inter-rating process’ in relation with validity:

• Regarding the interview data, we were both responsible for analysis to ensure the validity of the inter-rating process [125].

• To increase validity, however, a research assistant and the researcher separately read a portion of one interview transcript to develop codes [175].

Moreover, in two unique instances, the authors report that ‘the survey was piloted’ [35] with a small number of participants, and ‘the constant comparison technique’ [331] was employed in order to take care of validity. Along with this conceptual mix of the term validity, in a few articles, concerns and gaps related to a still fuzzy idea of this notion are stated as limitations of the reported research. In two cases, ‘self-reported data’ [227] and ‘overreliance on self-report verbal expressions’ [57] are seen as sources of potential limitations and threats in terms of validity, and in one case, long time research engagement, focusing on real-life contexts, and collaborative work are mentioned as important issues concerning ‘the ecological validity’ [263] of research. Finally, in one instance that may raise further epistemological questions about positivist/constructivist foundations of quality in qualitative inquiry, ‘larger sample size and integration of qualitative and quantitative methods’ are mentioned as requirements for ‘a more valid and reliable’ study [569].

3.4 Trustworthiness (credibility, dependability, confirmability, transferability)

Trustworthiness, as conceptualised by Lincoln and Guba (Reference Lincoln and Guba1985) and discussed in the context of applied linguistics by Edge and Richards (Reference Edge and Richards1998), is the next theme in our findings. As a broad concept, used almost synonymous with quality, this term is predominantly employed to explain authors’ efforts and adopted strategies for the enhancement of the quality and strength of the reported research. Different measures undertaken for increasing trustworthiness are explained, including ‘triangulation’ [e.g., 1, 119], ‘member checking’ [e.g., 175, 619], ‘thick description’ [e.g., 257, 473], and ‘corroboration’ [e.g., 7, 51, 525]. It is also more specifically used to refer to an outcome of the four components of Lincoln and Guba's (Reference Lincoln and Guba1985) model (credibility, dependability, confirmability, and transferability): ‘This study followed the set of alternative quality criteria – credibility, transferability, dependability, confirmability … to maintain the trustworthiness of this study … ’ [45].

These four components also feature as separate aspects of research quality in the examined body of articles. Credibility, as the most frequent one, is primarily used in relation with ‘prolonged engagement with the participants’ [295] and establishing trust and in-depth familiarity and understanding: ‘four years of “prolonged engagement” with the participants ensured the credibility of the findings’ [155]. Member checking is the second strategy applied ‘to establish credibility of the research method’ [173] and ‘to enhance credibility of findings’ [467]. In one case, member checking is even equated to credibility: ‘ … for purposes of member-checking (credibility) … ’ [329]. Moreover, several authors mention procedures like thick description and triangulation used for the specific purpose of establishing credibility rather than general trustworthiness:

• Credibility was established through the use of anonymized multiple data sources … with an emphasis on thick descriptions to develop conceptual themes … [21].

• This situation was addressed through a process of triangulation, which is central to achieving credibility … [385].

The term transferability is also observed in several texts. As a way of contributing to the quality (trustworthiness) of qualitative research, it is said to be strengthened through increasing the number and the diversity of participants [333, 653], ‘member checking’ [373], and ‘thick description’ [473]. In one case, the researcher specifically highlights the interface of transferability and generalisability: ‘The study results are specific to this context and are not generalizable to other contexts, although they may be transferable … ’ [87]. Moreover, there are a few instances of the word dependability, again in connection with triangulation, member checking, and general trustworthiness. As an example, one author's conception of the term can be placed somewhere between member checking and triangulation: ‘ … the dependability of my findings was verified by my inclusion of a group interview, where I asked the students to comment on and discuss some of the themes that had emerged in their individual interviews’ [523]. Finally, ‘confirmability’ appears only once in our data (in the quote at the end of the first paragraph of this section above [45]) along with the other three components as an aspect of the broader conception of trustworthiness.

3.5 Member checking

Authors describe how they carried out member checking and how it can serve research quality in their studies. Sending researchers’ draft analyses and interpretations to be verified and authenticated by participants [121, 125, 619]; conducting group interviews for member checking [683]; additional interviews for this purpose [435, 467]; ‘interviews and subsequent email exchanges’ [251]; ‘having respondents review their interview transcripts’ [609]; and asking the participants ‘to respond to a draft of the paper’ [553] are some of the adopted procedures. As for purposes, member checking is said to be undertaken ‘to enhance credibility of findings’ [467], to strengthen ‘the validity of the final analysis’ [251], to make sure that ‘analysis and interpretation is accurate and plausible’ [553], and ‘to ensure that the views, actions, perceptions, and voices of the participants are accurately portrayed’ [609]. There is also an individual case that considers member checking as a data collection source in its own right [7], and one that mentions the absence of member checking as a limitation of the study [465].

3.6 Corroboration

The conception of corroboration reflected in the examined research articles hardly resembles the way Edge and Richards (Reference Edge and Richards1998) conceptualise it. In our data, it is used in almost the same sense as data triangulation. The small number of instances of this term in these texts mostly refer to how certain bodies of data are used to corroborate ideas gained from other data sources. For example, ‘questionnaires, interviews, and field notes were used to corroborate the analysis’ [227]; ‘observation notes and video-recordings were used as complementary data, mainly in order to corroborate interview comments’ [431]. There are only two cases in which the meaning of corroboration is similar to that of Edge and Richards (Reference Edge and Richards1998). In one of them member checking is said to have been used ‘to corroborate the accuracy, credibility, validity, and transferability of the study’ [373]. In the other one, corroboration is mentioned in relation with how the research is reported: ‘Verbatim quotes were used frequently in presenting the study's findings in order to corroborate the researcher's interpretations’ [525].

3.7 Rigor

Instances of the term rigor in the studied articles show perhaps the least coherence in terms of its different intended meanings and ideas. There are some cases of broad emphasis on the importance of ‘a systematic and rigorous process’ [375] in qualitative inquiry, and the application of the term rigorous as a general positive adjective, for instance in claiming the implementation of ‘rigorous analytical procedures’ [471] or more specifically, ‘rigorous thematic analysis’ [449]. In addition, various procedures are said to have been adopted to strengthen rigor, like independent analysis of data by two researchers, ‘to enhance reliability and rigor’ [35] or the application of both deductive and inductive approaches to thematic analysis, ‘to ensure further rigor’ [7]. The triangulation of different data sources and the combination of various data types are also described in a few articles [97, 119] as the adopted practical procedures of taking care of rigor in these qualitative studies. Finally, one of the studied articles refers to a complex mechanism adopted in favour of transparency and rigor: ‘In order to be as transparent and as rigorous as possible in testing the analyses and interpretations, eight tactics were adopted … ’ [711].

3.8 Thick description

Thick description did not frequently appear in the body of examined research articles. The small number of instances, however, depict the potentially important role that it can play in enhancing the quality of qualitative research through not just telling the reader what was done, but how. The importance of looking at a phenomenon in-depth and holistically, going beyond surface-level appearances, featured several times as an explicit strategy to position research as complementing existing knowledge, including:

• This study has obtained and provided thick descriptions of the participant's perceptions, behaviors and surrounding environment. These thick descriptions could create a transparency and assist the reader in judging the transferability of the findings … [473].

• Through a thick description of various classroom tasks used by the teachers, the study has provided a useful reference for EFL teachers in Vietnam and similar settings … [47].

Moreover, researchers reportedly employed thick description ‘to add lifelike elements’ [31] to the interpretive narrative, and ‘to develop theoretical arguments’ [377] based on contextualised details. In other cases, the scope of the matters typically associated with thick description – history, context, and physical setting (Mills et al., Reference Mills, Durepos, Wiebe, Mills, Durepos and Wiebe2010) – were not explicated, with the concept foregrounded as a means of facilitating a higher-order feature of qualitative research quality such as ‘credibility’ [21] and ‘reflexivity’ [257]. Our codes also include clues as to researchers’ awareness of the tension between ‘in-depth thick description’ [301] and the size of the recruited sample. In such cases, illustrating contextual peculiarities through ‘the creation of a “thick description” … of the situation’ was framed as the goal of research, ‘instead of generalizability’ [475].

3.9 Transparency

The notion of transparency does feature in our data as an aspect of quality in qualitative studies but is not frequent. Apart from some general reflections of researcher concern about a broadly perceived, ‘more transparent and accountable...research process’ [39], transparency in the articles that we examined is mostly linked to authors’ perspectives towards the processes and procedures of data analysis. Researchers state that they attempted ‘to be as transparent and as rigorous as possible in testing the analyses and interpretations’ [711] and explain how their adopted approach ‘makes transparent to readers the inductive processes of data analysis’ [719]. The need for transparency is explained by one researcher because ‘I see myself as a major research instrument’ [539], while for another, the ‘off the record’ nature of the qualitative data collection methods employed necessitated ‘render[ing] more transparent and accountable the research process’ [133]. There is also a single case indicating that thick description was used to ‘create transparency and assist the reader in judging the transferability of the findings’ [473]. Moreover, a particular conception of transparency is reflected in viewing overall trustworthiness, ‘as well as reflexivity’ of research as a way ‘to ensure the transparency of the possible researchers’ bias’ [45]. In one instance that reflects this conception, the transparency of researcher positioning appears to be a central concern: ‘As an ethnographer, I see myself as a major research instrument, and believe it is essential to be as transparent as possible in my positions and approaches so that readers can make their own interpretations’ [539].

3.10 Reflexivity

As noted above, conceptions of transparency can be closely connected with reflexivity. The understanding of the researcher bias and research transparency in relation with reflexivity is explicitly projected in the very small number of examined articles that specifically mentioned reflexivity as a significant consideration in their research process. However, there was rarely an overt indication of if/how reflexivity was understood in connection with qualitative research quality. One article referred to the ‘powerfully reflexive’ [39] nature of the methodological frameworks and approaches that they adopted, while another stated that data analysis was viewed as a ‘reflective activity’ but did not specify the purpose, nature, or features of this reflexivity: ‘We viewed analysis as an ongoing, cyclical, and reflexive activity’ [11]. Instead, connections with study quality could only be discerned on the two occasions when authors stressed that heightened reflexive awareness, stemming from the processes of conducting action research, allowed them to be more attuned to the needs of their learner-participants.

4. Discussion and conclusions

4.1 No explicit quality criteria

The notion of quality in qualitative research is complex, requiring authors to address certain fundamental epistemological and methodological issues that compare with quantitative research as well as producing a creative, engaging, and convincing report (Bridges, Reference Bridges2017; Flick, Reference Flick2007; Mahboob et al., Reference Mahboob, Paltridge, Phakiti, Wagner, Starfield, Burns, Jones and De Costa2016). Among the 236 studies that we investigated, three broad orientations were apparent in authors’ approaches to attending to research quality in language education research. The first (and most ambiguous) was where little explicit consideration of research quality could be uncovered. We would obviously not interpret this necessarily as an indication of weak or weaker research. It could be that authors did indeed imbue their articles with the qualities examined in the respective study but took quality for granted or understood it as an aspect of research embedded in how it is conducted without feeling the need to explicitly describe and explain their approach(es). It could also be that they employed more linguistically varied concepts that were missed in our analysis (e.g., ‘collecting different types of data’ instead of ‘data triangulation’).

While we acknowledge the necessary fluidity and creativity of qualitative research and do not seek to constrain authors’ approaches, we feel there are good reasons why researchers ought to explicitly foreground attention to quality. The first argument stems from a concept familiar to many researchers, that of methodological transparency (Marsden, Reference Marsden and Chapelle2019; Mirhosseini, Reference Mirhosseini2020; Tracy, Reference Tracy2020). This encompasses not a call for greater procedural objectivity (Hammersley, Reference Hammersley2013), but rather, the provision of a fuller description of the nuances and complexities of the processes that feature implications for study quality (Mills et al., Reference Mills, Durepos, Wiebe, Mills, Durepos and Wiebe2010), allowing greater retrospective monitoring and assessment of research (Tracy, Reference Tracy2010), enhancing trustworthiness (Hammersley, Reference Hammersley2013), and facilitating ‘thick interpretations’ of the nature and value of the research at the broadest level (Mills et al., Reference Mills, Durepos, Wiebe, Mills, Durepos and Wiebe2010). For the second reason, we invoke the centrality of argumentation to the ‘truth’ of qualitative research (Shohamy, Reference Shohamy2004). Greater explicit attention to quality may bring to the foreground additional relevant research evidence, providing a more secure foundation for scholars’ warrants (Edge & Richards, Reference Edge and Richards1998; Usher, Reference Usher, Scott and Usher1996). This could particularly help a manuscript's prospects at peer review, given that journals are increasingly utilising criterion-referenced checklists for reporting qualitative research (Korstjens & Moser, Reference Korstjens and Moser2018), and because inexperienced reviewers may struggle to assess the rigor of qualitative research (Spencer et al., Reference Spencer, Ritchie, Lewis and Dillon2003), or owing to pressure on their time, be positively disposed towards concise, explicit explanations of research quality (Cho & Trent, Reference Cho, Trent and Leavy2014).

4.2 Positivist views of quality

The study found that the terms validity and reliability predominantly associated with positivist traditions were prevalent across qualitative language education research, even among recent studies. In a number of instances, it was evident that authors were adopting reliability in alignment with the positivistic sense of ‘the measurement method's ability to produce the same results’ (Stenbacka, Reference Stenbacka2001, p. 552). This was apparent in the attention paid to the reliability of coding data by multiple researchers, indicative of an underlying belief in the identification and mitigation of researcher bias (Barbour, Reference Barbour2001; Kvale, Reference Kvale1996) and a singular meaning or truth being embedded within a given transcript (Terry et al., Reference Terry, Hayfield, Clarke, Braun, Willig and Rogers2017). Indeed, the provision of a figure for the proportion of the dataset that had been re-coded at random along with an interrater reliability statistic, such as Cohen's kappa, indicated arithmetic intersubjectivity (Kvale, Reference Kvale1996), evidence that some authors had – consciously or otherwise – adopted a stronger positivistic philosophy.

While analysts do need to pay careful attention to faithfully representing the meanings conveyed by their participants (Krumer-Nevo, Reference Krumer-Nevo2002), there is hardly any sympathy in qualitative research literature for the position that analysts need to disavow their own perspectives in the search for objective truth (Kress, Reference Kress2011). Instead, qualitative analysis must always be meaningful to the researcher, who endeavours to capture their own interpretations of the data, as opposed to ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ (Terry et al., Reference Terry, Hayfield, Clarke, Braun, Willig and Rogers2017), and to account for the unique perspectives they bring to the analysis through reflexive insights into the process. We agree with the position of Barbour (Reference Barbour2001) in that double coding of transcripts offers value more in how the content of coding disagreements and the discussions that follow alert coders to alternative interpretations and shape the evolution of coding categories, rather than to indicate the exact degree of intersubjectivity. Nonetheless, such insights were absent across our data, possibly resonating limitations imposed upon authors by some journals, but also indicating still lingering positivist mentalities among qualitative researchers in applied linguistics and language education.

In other instances, it was evident that validity and reliability were being used more qualitatively, such as providing participants with the final say through member checking to enhance a conception of study reliability (and validity) equated to consistency (Noble & Smith, Reference Noble and Smith2015). However, owing to the lack of thorough description and explanation, a point we remark on later, in several examples it was entirely unclear what precise conception of validity or reliability language education researchers were drawing upon. In such cases, a burden was varyingly placed upon the reader to interpret the mechanism(s) through which the stated quality measures enhanced the study (and according to what epistemological perspective). This was particularly the case with validity, which was usually conceived of from a holistic, whole-study perspective, rather than addressing discrete forms of data collection and analytical techniques.

Where usages of the terms validity and reliability were not explained, it appeared that language education researchers seem content using the language of positivist inquiry, perhaps as part of a conscious effort to improve the credibility and legitimacy of the study for a more successful peer review (Patton, Reference Patton2002), since not all reviewers are adept at judging qualitative research using interpretive concepts (Spencer et al., Reference Spencer, Ritchie, Lewis and Dillon2003), or some still hold the perspective that ‘anything goes’ in qualitative research (Mirhosseini, Reference Mirhosseini2020). However, as it was beyond the scope of the study to query authors directly on their use of such terms, we cannot judge if such representations indicate qualitative language education scholars adhered to positivist or critical realist traditions, or even that they are explicitly aware that validity and reliability carry significant epistemological baggage (since explicit discussion of epistemological views underlying research methods is not always a component of research methodology courses and texts). Indeed, the use of such terms could constitute an effort to bring the interpretive and positivist traditions together by emphasising the universality of research quality conceptions (Patton, Reference Patton2002).

4.3 Interpretive quality conceptions

It appeared that many authors opted for diverse interpretivist concepts and strategies in which to foreground claims of qualitative research quality. However, it was exceedingly rare for authors to explicitly situate consideration of research quality fully within any one theoretical framework. Just one study made complete use of Lincoln and Guba's (Reference Lincoln and Guba1985) componential model of trustworthiness, with several other authors drawing upon one or more strands in order to enhance rigor. It would appear, consciously or not, that the vast majority of authors adopted a flexible position on quality, engaging the reader with an overarching argument for research relevance, originality, and rigor (Shohamy, Reference Shohamy2004), rather than elaborating a more foundationalist exercise in quality control. It also reflects the subjective, interpretive nature of the provision of adequate warrants for knowledge claims, a comprehensive undertaking likely beyond the modest length limitations afforded to authors in journals that publish qualitative manuscripts (Tupas, Reference Tupas and Mirhosseini2017). No studies were found to formally adhere to other well-known quality frameworks (e.g., Richardson, Reference Richardson2000; Spencer et al., Reference Spencer, Ritchie, Lewis and Dillon2003; Stewart, Reference Stewart1998; Tracy, Reference Tracy2010), suggesting a failure of such models to permeate the language education literature for reasons beyond the scope of the present study.

The preference for author argumentation over criterion-referenced explication was visible in authors’ selection of eclectic quality assurance measures and rationales. Researchers adopted a range of strategies, albeit triangulation and member checking prevailed. No clear patterns emerged in the selection of procedures to enhance study rigor specific to particular methodological approaches, (e.g., Creswell's ‘Five approaches’), in spite of much ‘research handbook’ guidance that aligns particular strategies to methodologies (see Creswell, Reference Creswell2007). This would further indicate that qualitative language education researchers value creativity and flexibility in constructing an argument of study quality, and that quality assurance strategies are judged on their conceptual and theoretical ‘soundness’, rather than as a requirement to align to a given methodology.

It is also important to note that attention to quality using either positivist or interpretivist concepts was usually presented descriptively and procedurally, with authors seldom engaging in deeper philosophical discussions of research quality. This may be as a result of the many well-meaning guidelines on qualitative research, where issues of quality are often presented procedurally for easy comprehension and implementation (Flick, Reference Flick2007; Maxwell, Reference Maxwell2013). Procedural information helpfully verified that certain techniques had been adopted or processes followed, albeit questions or uncertainties that (we felt) warranted further discussion were often apparent (we again acknowledge the constraints imposed upon authors in this regard). Facileness in attention to quality particularly encompassed the triangulation of sources and methods, the possible role of disconfirming evidence (across sources, methods, and participants), and the outcomes of respondent validation. While attention to quality certainly encompasses a procedural dimension, we also feel that notions of research quality constitute part of the broader epistemological argument running through the reporting of a research study. In this way, researchers need to present a convincing case explaining the basis for selecting the various approaches and how they enhanced study rigor.

We recognise that existing publishing constraints (like word limits) are hardly helpful in elaborately addressing issues of research quality. Indeed, in reporting our own findings here, we were limited in the level of nuance and detail that we were able to convey, for example, concerning our positionality and epistemological stance. However, we believe it can benefit qualitative research in the area of language education if authors reflexively address the complexities involved in attending to various dimensions of research quality, as reflected in the ten thematic notions illustrated in this paper. Although these diverse dimensions were not strongly projected in all the research articles that we examined, visible in our data were reflections upon how study quality could be enhanced in future research, which could offer alternatives to how authors in our field address matters of research quality.

Competing interests

The author(s) declare none.

Seyyed-Abdolhamid Mirhosseini is an Associate Professor at The University of Hong Kong. His research areas include the sociopolitics of language education, qualitative research methodology, and critical studies of discourse in society. His writing has appeared in journals including Applied Linguistics; Language, Identity and Education; Critical Inquiry in Language Studies; and TESOL Quarterly. His most recent book is Doing qualitative research in language education (Palgrave Macmillan, 2020).

William S. Pearson is a lecturer in language education at the School of Education, University of Exeter. His research interests include candidate preparation for high-stakes language tests, written feedback on second language writing, and meta-research in language education. His works have appeared in Assessing Writing, the Journal of English for Academic Purposes, Lingua, and ELT Journal.