We should be fully aware of the role of the internet in national management and social governance.

(Xi Jinping, 2016)The use of social media helps reduce costs for …resource-poor grassroots organizations without hurting their capacities to publicize their projects and increase their social influence, credibility and legitimacy.

(Zengzhi Shi, 2016)China's online population more than tripled in the past decade, exceeding 800 million in 2018. Concurrently, social media has not only become a popular means of communication among Chinese citizens, but also expanded the medium for communications between the government and ordinary people, and among citizens themselves. Even before the advent of microblogs (weibo 微博) such as Sina and Tencent Weibo in 2009, the emergence of cyber-communities led early observers to declare that the internet and civil society were developing in a co-evolutionary manner in China.Footnote 1

Since then, Weibo has become the dominant public platform that netizens (wangmin 网民) use for expressing opinions about various domestic and international issues.Footnote 2 Some scholars thus view Weibo as a new public space for online deliberation with potential for setting policy agendas.Footnote 3 Others concur that Weibo facilitates online political participation, and believe it may improve governance, if not promote democratization. Guobin Yang, for example, regards online activism as “a microcosm of China's new citizen activism” that constitutes unofficial expression of “grassroots, citizen democracy.”Footnote 4

Amid these sanguine assessments of social media's liberalizing impact, this article analyses online micro-philanthropy projects that have garnered national attention, but with differential effects on the central government's policy agenda. On social media, micro-charity campaigns or “charitable crowdfunding” (gongyi zhongchou 公益众筹) refer to mobilization of individual donations for projects without expectation of material rewards or financial re-payment.Footnote 5 To identify concerns with potential policy implications, this study focuses on Weibo campaigns launched on behalf of social causes or the public good rather than individual needs (for example, one person's hospital bill). Furthermore, unlike topics that incite periodic waves of cyber-sentiment (for example, a foreign policy incident), charitable crowdfunding campaigns concern domestic policy issues that motivate citizens to donate personal funds. The latter arguably signals deeper commitment to a public cause than online venting without monetary support, however modest the nominal amount.Footnote 6

Issues that attract domestic donations in China are particularly meaningful given that charitable giving is at a nascent stage. Out of the 144 countries analysed in the Charities Aid Foundation (CAF)’s World Giving Index 2018, China ranks 142.Footnote 7 Despite this low ranking, the volume of domestic donations is rising steadily. According to the China Charity Alliance (CCA), in 2017 charitable donations reached 150 billion yuan (US$22.1 billion), an increase of 7.68 per cent from 2016.Footnote 8 By comparison, online contributions increased by 118.9 per cent during the same period. While funds mobilized through the three largest platforms (Alipay, Taobao, and Tencent) accounted for only 1.6 per cent of China's total domestic donations in 2016, the fact that hundreds of millions of netizens donated at least 2.59 billion yuan (US$380.9 million) warrants further investigation.Footnote 9 In particular, beyond the financial value of these contributions, to what extent are charitable crowdfunding campaigns making a difference to China's policy environment?

At the most successful end of the spectrum, the Free Lunch for Children campaign raised 128 million yuan in small individual donations between April 2011 and February 2015. These funds enabled 440 schools in impoverished areas to serve hot lunches.Footnote 10 The campaign inspired county governments in multiple provinces to launch free lunch programmes – and culminated in a national initiative to alleviate malnutrition among rural schoolchildren. Most micro-charity efforts have not yielded such swift and linear policy impact. Nonetheless, some have contributed to raising public awareness of specific issues and demonstrated agenda-setting influence. To develop a better estimation of the relative policy influence of charitable crowdfunding, we constructed an original database of campaigns listed on Weibo platforms from 2011 to 2017. In addition to regression analysis, we conducted case studies of select campaigns to understand the circumstances under which their issue areas have reached the national policy agenda (or not).

Analytically, our findings address long-standing concerns in the study of media and politics, with implications for understanding the responsiveness of authoritarian regimes to citizens in the digital age. What are the channels through which grassroots/digital advocacy are translated into public policy issues? Under what circumstances do issues highlighted in social media inspire constructive governmental responses? Addressing these questions is especially complex in non-democratic settings where formal institutions circumscribe sanctioned forms of political participation, yet in practice, scope for individual expression and collective action remains. Political scientists have observed that the parameters of this space in China may be tolerated to bolster regime legitimacy.Footnote 11 But the expansion of societal participation may be unintended, due to incomplete regulation, weaknesses in policy enforcement, or “boundary spanning” challenges by activists and NGOs.Footnote 12 These possibilities are facilitated by China's multi-layered and fragmented bureaucratic structure.Footnote 13 Building on these observations, this study considers the extent to which charitable crowdfunding on social media represents an emergent medium for policy advocacy in contemporary China.

The article proceeds as follows. The first section combines insights from agenda-setting theory with scholarship on “responsive authoritarianism” in China to explore the policy potential of social media in non-democratic contexts. The second part reviews the state of online charitable giving in China; explains the research methodology for this project; and summarizes findings from our database of 188 charitable crowdfunding campaigns active on Sina Weibo as of 2017. Our analysis indicates that the vast majority of campaigns have not had explicit policy aspirations. Among those pursuing policy objectives, however, nearly two-thirds have had either agenda-setting influence or contributed to policy change. Based on field interviews, case studies of the four largest micro-charities – Free Lunch for Children, Love Save Pneumoconiosis, Support Relief of Rare Diseases, and Water Safety Program of China – are presented to highlight factors contributing to their variation in national impact. All four programmes mobilized the largest volume of funds in their sectoral categories on Weibo and also experienced an initial phase of “viral” online support; yet they differed in agenda-setting and policy influence. Overall, we observe that impactful online campaigns complement and amplify, rather than challenge existing government priorities. Furthermore, the case studies and regression analysis both indicate that substantive support (versus superficial hosting) of a micro-charity by a government entity is necessary, but not sufficient for agenda-setting or policy impact.

Agenda-Melding Media and Authoritarian Responsiveness

Research on media and politics traditionally emphasizes the concept of “agenda-setting,” meaning the ways issues are brought to public awareness.Footnote 14 In particular, everyday media can play a pivotal role in converting the concerns of citizens into issues on the public agenda. Bernard Cohen noted, “The press may not be successful much of the time in telling people what to think, but it is stunningly successful in telling its readers what to think about.”Footnote 15 Media also influences policy-agenda setting by affecting public preferences and the views of decision-makers.Footnote 16 Due to advances in technology, traditional forms of vertical media such as print media, radio, television, and film no longer monopolize communications. The spread of horizontal mediaFootnote 17 and virtual media (including SMS, and internet-based platforms) has pluralized the creation and transmission of information.Footnote 18 As a result, agenda-setting theory has given rise to studies of “agenda-melding,” which is defined by “the personal agendas of individuals vis-à-vis their community and group affiliations.”Footnote 19 Online communities enable ordinary citizens to define new agendas, consume information more selectively, and increase interactions with those who share their values and beliefs. Relatedly, the wireless technology supporting agenda-melding has enhanced the organizational capacity of issue and identity-based groups to engage in collective action. This was illustrated vividly during the Arab Spring movements, starting in 2010 with Tunisia's Jasmine Revolution.

It is in this context that the impact of media on policy agendas in authoritarian regimes, including China, has become fertile ground for research. Some emphasize party-state monitoring and restriction of online activity. Anne Marie Brady observes, “For all but the most tech-savvy Netizens in China, the global Internet is actually experienced as a de facto China-based Intranet.”Footnote 20 Because all forms of media are subject to some degree of censorship, the party-state “dictates public opinion”Footnote 21 through numerous propaganda channels, including paid online commentators (called the “50 Cent Party” wu mao dang 五毛党).Footnote 22 Even before intensification of cyber-repression under Xi Jinping 习近平, a broader content analysis of different types of media found that online public opinion does not have an agenda-setting effect on public policy; instead, “the government is still the major agenda setter in China.”Footnote 23

Yet critical discourse persists online. China's netizens have devised assorted forms of “digital resistance,” including use of proxy servers, coded language and political satire.Footnote 24 One study of 1,400 social media platforms found that censorship is not as prevalent as widely believed, though posts indicating potential for offline group mobilization are swiftly removed.Footnote 25 Consistent with the logic of agenda-melding, others point to salient instances of popular outrage as evidence of social media's mounting influence on the public agenda.Footnote 26 As Danielle Stockman noted in her work on “responsive authoritarianism,” commercialization of media has expanded the space for “issue publics” to express strongly held attitudes about particular topics, albeit circumscribed in ways intended to preserve the Party's monopoly over political power. Along with other forms of “managed participation,” such as petitions and “disguised collective action,” social media may thus be regarded as an input institution that facilitates, rather than undermines, authoritarian resilience.Footnote 27 Indeed, field experiments on digital governance in China find that local governments in more developed areas are responsive to constituency requests for information; moreover, local governments can be equally receptive to citizen preferences expressed through the internet as through formal institutions. Within social media, charitable crowdfunding arguably represents an emerging medium for Chinese netizens to converge as issue publics and exert policy pressure within the scope of responsive authoritarianism. Our study represents an initial effort at gauging the circumstances under which crowdfunding campaigns have had agenda-setting and/or actual policy influence.

Despite expansion of research on social media's political impact, none has systematically focused on digital micro-philanthropy in China. Some case studies, for example, of Project HopeFootnote 28 and relief efforts following the 2008 earthquake in Wenchuan, Sichuan,Footnote 29 touched upon online mobilization of volunteers and donations. Others have noted examples of grassroots non-governmental organizations (NGOs) that started out as online communities.Footnote 30 More recent research examines what motivates people in China to donate to micro-charities,Footnote 31 and the relationship between online and offline civic activism.Footnote 32 But China scholars have yet to conduct an integrative analysis of all the micro-charity campaigns on Weibo with the objective of assessing their relative effectiveness in agenda-setting influence and policy impact. As detailed next, to address this lacuna we created a dataset of micro-charity campaigns on Weibo and conducted in-depth case studies of projects in various issue areas.

Methodology for Assessing China's Charitable Crowdfunding Environment

Online donations are collected through a variety of wireless media, including websites, IM/QQ, internet bulletin board systems (BBS), third-party payment platforms, and microblogs. In 2014, 68 per cent of online donations were collected through mobile devices (versus PCs), which accounted for over 70 per cent of total online donations. Within this category, Alibaba-related crowdfunding (Alipay and Taobao), Sina and Tencent dominate the charitable crowdfunding market.Footnote 33 This project focuses on Sina and Tencent because Alipay, China's largest online payment platform, operates according to a different model from the other two. Alipay's E-Philanthropy site hosts domestic foundations pro bono, and its One Foundation Monthly Donation programme enables automatic deductions from Alipay accounts. Taobao's mode of mobilizing donations is similarly tied to commercial transactions. By contrast, Sina and Tencent's micro-charities are linked with their public Weibo microblogs, launched in 2010. These platforms host virtual communities where members publicly share information, express opinions and debate various topics. Hence, our working assumption was that Weibo donors feel more strongly about an issue than consumers who incidentally pledge money while shopping online.

The selection criteria for our database of micro-charity projects were as follows.Footnote 34 First, to target campaigns with more enduring appeal, only “branded projects” (pinpai gongyi juankuan 品牌公益捐款) were included rather than “individual projects” (geren gongyi juankuan 个人公益捐款). Initiated by foundations with registered names, so-called “branded projects” (in Chinese) are more appropriately called “public interest projects” (in English), because they encourage ongoing contributions from supporters to address a widely shared issue. By contrast, individual projects specify a monetary funding goal to help a private citizen and such projects terminate when the requested amount is raised. Our database focused on projects posted on the Sina Micro-Online Donation platform (2011 to 2017) because there are more public interest projects on Sina than Tencent, and the Tencent projects overlap with those on Sina. Second, the database only included projects that are national in scope and relate to a public issue subject to (potential) regulation by the central and/or local governments. As of 1 November 2017, all of the 188 branded/public interest projects on Sina Weibo met the criteria for inclusion in the database (Table 1).Footnote 35

Table 1: Descriptive Summary of 188 Public Interest Projects on Sina Weibo, 2011–2017

Source:

Sina Weibo, 1 November 2017.

The descriptive data recorded for each project includes: name; initiation date; sponsoring foundation; issue area; number of donors; donation size; total amount mobilized (on Weibo, from other online sources, and offline); and number of project supporters (zhichi 支持) and microblog followers or “fans” (fensi 粉丝).

The next step assessed whether projects had explicit policy aspirations. This entailed content analysis of self-reported objectives on the Weibo listing and was coded dichotomously. Although all of the branded/public interest projects concern needs that could plausibly be addressed by public policy measures, many campaigns simply raise funds for people affected by the issue rather than trying to enlist government support or lobby for policy changes. The One More Dish for Children and Additional Food with Love projects, for example, seek to improve the nutritional status of rural children. Unlike Free Lunch for Children, however, neither project suggested that the government should participate in this mission or has the responsibility to attend to children's nutrition.

For projects with policy aspirations, evaluating each project's public impact involved: i) content analysis of official news through the Xinhua search engine to measure the frequency that particular issues are covered; and ii) process-tracing developments in particular issue areas by reviewing policy statements from government bureaus and ministries. The following three-point scale was used to code public impact: 1–no government response, 2–agenda-setting influence, and 3–policy impact. Agenda-setting influence is indicated by the following: 1) whether deputies to the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC) and National People's Congress (NPC) have demonstrated willingness to submit proposals or already submitted proposals for consideration at the annual meetings of the CPPCC and NPC; and 2) the extent to which governmental entities at the local or central level acknowledge the existence and severity of the problem, have publicly expressed commitment to addressing it, or taken initial efforts to address the issue in collaboration with relevant NGOs. Policy reform is indicated by reform of existing policies, the introduction of new institutions or policies, and/or enhanced budgetary commitment to addressing the issue.Footnote 36

Overview of Charitable Crowdfunding on Sina Weibo

As shown in Table 1, out of the 188 public interest micro-charity projects on Sina Weibo, over half concern either children's welfare (56 projects) or education (39 projects). Health care (18 projects) and environmental protection (16 projects) are the next two most popular categories. Based on the total value of donations mobilized, the top three categories are children's welfare (7.5 million yuan), environmental protection (2.9 million yuan), and veteran's welfare (2.8 million yuan). In terms of the aggregate number of donors, children's welfare, veteran's welfare, and healthcare and diseases are the three most popular programmes, respectively. As for the scale of individual donations, veteran's welfare mobilized the largest average size (553,520 yuan), which is nearly three times larger than the next largest average donation, mobilized by environmental protection projects (180,502 yuan). The five projects devoted to veteran's issues also attracted the largest average number of donors.

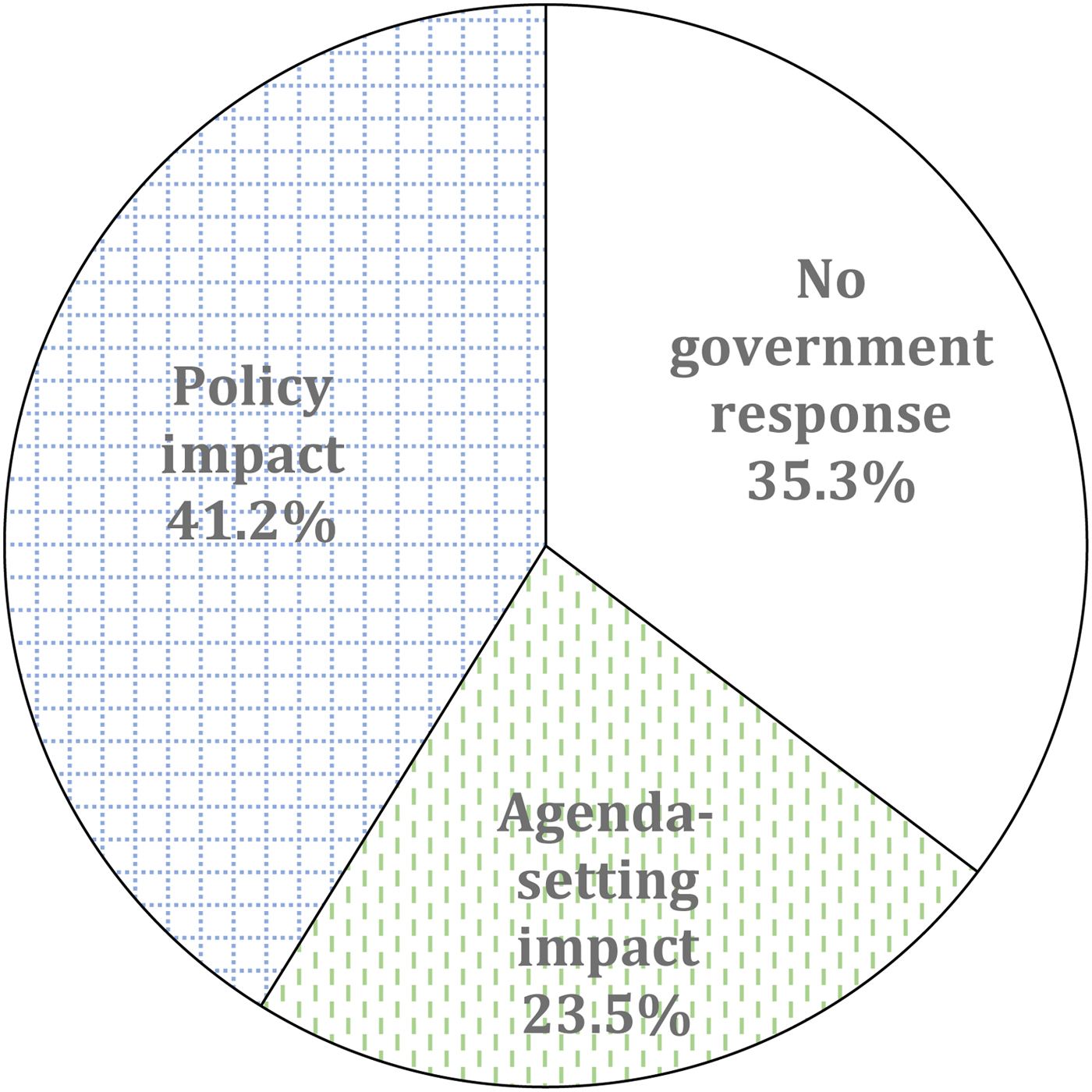

Among the 188 public interest projects on Sina Weibo, 34 (18%) have policy aspirations.Footnote 37 Table 2 shows that the plurality of impactful projects concern children's welfare (38%) followed by environmental protection (23.5%) and healthcare (14.7%), respectively. Crowdfunding campaigns relating to education, animal protection and children's health issues each account for less than three per cent of the long-term projects. Figure 1 shows that among the 34 programmes with public policy objectives, 14 resulted in some degree of official policy reforms/initiatives (41.2%), 12 raised public awareness but without eliciting any governmental response (35.3%), and eight have had agenda-setting influence by receiving public support from CPPCC or NPC deputies, but without concrete policy reform (23.5%).

Figure 1: Relative Impact of 34 Long-term Charitable Crowdfunding Projects on Sina Weibo, 2011–2017

We also conducted regression analysis to identify which types of programmes are more likely to have policy aspirations and public impact, respectively (see Appendix B). The analysis revealed a statistically significant correlation between issue salience in the media and the likelihood that a micro-charity would seek policy reform. Specifically, public interest topics covered by news media in the seven days preceding the launch of a crowdfunding campaign in the same field is positively correlated with policy aspirations, ceteris paribus. The mechanism underlying the salience effect is that widespread media coverage enhances popular awareness about an issue, which in turn, emboldens crowdfunding organizers to specify policy objectives.

Table 2 shows that among the 14 campaigns that have had tangible policy impact, all are concentrated in children's welfare, environmental protection and poverty alleviation. Furthermore, eight out of the 14 projects with policy impact were initiated by public foundations with ties to government entities, which provides them with “within establishment” (tizhinei 体制內) allies in policy advocacy efforts.Footnote 38 For example, the Water Cellar for Mothers campaign – devoted to building water cellars for those facing acute water shortage in western China – was initiated by the China Women's Development Foundation, which is registered with the Ministry of Civil Affairs (MCA), approved by the People's Bank of China and sponsored by the All-China Women's Federation.Footnote 39 By contrast, the dozen projects that have failed to garner government attention for their issues (coded “1” in Table 2) have generally been championed by grassroots organizations lacking meaningful connections to public officials or institutions.Footnote 40 Projects lacking policy impact thus far are disproportionately concentrated in healthcare and disability-related areas, accounting for eight out of the 12 projects.

Table 2: Impact of 34 Public Interest Projects with Policy Aspirations, 2011–2017

Source:

Sina Weibo, 1 November 2017.

Notes:

a. # indicates rank in project initiation date. Projects are sorted by relative impact (3–policy impact, 2–agenda-setting impact, 1–public awareness without government response); initiation sequence (# column); and amount mobilized. Definition of this three-point scale is provided in the last paragraph of “Methodology.”

b. Support Relief of Rare Diseases (see case study below) is not included among these 34 public interest projects because it ended its online fundraising on Sina Weibo in 2016. Its sponsors indicated that they terminated the campaign due to insufficient staff to manage the online campaign, and they wanted to target resources in a more focused manner. Since our database includes cases running from 2011 to 2017, we did not include Support Relief of Rare Diseases in this section's analysis.

Case Studies

To understand the circumstances under which charitable crowdfunding campaigns have agenda-setting or policy impact, we conducted four case studies of projects ranking among the top ten in mobilized funds on Weibo: Free Lunch for Children [Free Lunch (mianfei wucan 免费午餐)], Love Save Pneumoconiosis [Love Save (da'ai qingchen 大爱清尘)], Support Relief of Rare Diseases [Rare Diseases (zhuli hanjianbing, yiqi dongqilai 助力罕见病,一起冻起来)] and the China Water Safety Project (Zhongguo shui anquan jihua 中国水安全计划). The selection criteria of these projects were that they represent the most popular micro-charities in their categories on Sina Weibo in the monetary amount mobilized. We also selected a popular public interest project (Rare Disease) that had already delisted from Sina Weibo to trace its advocacy activities beyond the crowdfunding phase. Although all four campaigns are hosted by national foundations, they had differential impact on the central government's policy agenda as of late 2017. Free Lunch was exceptionally successful. Love Save encountered political resistance during its initial phase, but eventually attracted attention from central governmental entities and stimulated public legislative discussion. Rare Disease raised the most money from Weibo out of all the micro-charity projects posted to date, which helped to generate both popular support and emergent central governmental attention to its concerns. While Water Safety was initiated at the same time as Free Lunch and also raised significant funds, its advocacy efforts have yet to yield meaningful impact on policy agenda-setting. Process-tracing the origins and evolution of these campaigns provides insight into their variation in impact.

Free Lunch for Children

In April 2011 the investigative journalist Deng Fei 邓飞 co-founded Free Lunch for Children through the China Social Welfare Foundation, a national public fundraising foundation registered with the MCA since 2005.Footnote 41 The micro-charity encouraged supporters to donate three yuan per day to help schools serve warm meals to students in impoverished localities. With the support of hundreds of journalists and dozens of domestic media outlets, within the first month of the Free Lunch campaign, over 100,000 netizens had contributed over one million yuan. From inception, Free Lunch explicitly indicated that its strategy was to work with “the government, enterprises, public interest organizations and individual donors, and to constantly facilitate public policies.”Footnote 42

This call for local governmental action was received with initial scepticism, as seen in the following post by a local Finance Department official in May 2011:

Who will take the responsibility for food safety and transparency of information? If anything goes wrong with this project, who should be blamed? Most schools are located in such remote and poor areas that donating merely three yuan to every student will not comprehensively solve the whole problem. Also, while three yuan per person may not be a large amount, if you triple the number of eligible students, then that would become a huge burden for government expenditures.Footnote 43

Other government officials expressed similar concerns through comments posted on the Free Lunch site.Footnote 44

The tide turned, however, as various local governments in Hunan, where Deng Fei's investigative reporting was well known, started indicating public support and taking action. Already designated as a “national poverty county,” Xinhuang county was the first to pledge its commitment to alleviating malnutrition among rural schoolchildren:

After only one month of publicity, the Xinhuang county government has decided to cooperate with the Free Lunch program to guarantee that all pupils in Xinhuang county have a nutritious meal at least once a day with the county's budgetary assistance.Footnote 45

Following Xinhuang's declaration of support, which was extensively shared on Weibo, several counties in Guangxi, Guizhou and Henan provinces sought to collaborate with Free Lunch. In addition to establishing special funds, supportive counties enacted disciplinary measures to ensure the provision of free lunches. Within two years of the launch of Free Lunch, dozens of local governments either collaborated with Free Lunch or independently introduced similar programmes.

The central government joined in support. On 26 October 2011, the PRC State Council announced a plan to provide lunch to 2.6 million students residing in 699 pilot localities by committing 16 billion yuan in national funds annually.Footnote 46 In November 2011, the State Council followed up with guidelines for the Rural Compulsory Education Nutrition Improvement Program. To complete the process – characteristic of China's iterative, multi-pronged mode of policymaking – in May 2012, 15 central departments jointly issued detailed provisions for implementing the programme. Free Lunch achieved national policy impact in a remarkably short period of time.

Love Save Pneumoconiosis

While Free Lunch was inspired by the plight of malnourished schoolchildren, Love Save Pneumoconiosis concerns an occupational health hazard afflicting rural migrant workers. Public awareness of pneumoconiosis (black lung disease) came to light in 2009 when a migrant worker, Zhang Haichao 张海超, from Henan, opted for invasive thoracic surgery to confirm its diagnosis. Caused by long-term inhalation of fine dust particles, symptoms of pneumoconiosis include difficulty breathing, pulmonary tissue fibrosis and irreversible organ damage. The PRC National Health and Family Planning Commission (NHFPC) reports that pneumoconiosis accounts for 90 per cent of all occupational diseases in the country, with a 22 per cent mortality rate.Footnote 47 As an occupational disease, employers are responsible for the treatment of affected employees. However, few companies have offered sufficient financial assistance for medical care, leading to the incapacitation of workers with pneumoconiosis and extreme hardship for their families.

At the beginning of 2010, the editorial team of journalist Wang Keqin 王克勤published an investigative article in China Economic Times about a “pneumoconiosis village” in Gansu where nearly all of its adult male population had developed black lung disease after working in gold mines for many years. Frustrated by the lack of government attention on the health crisis facing miners and other migrant workers, Wang Keqin reposted news articles about pneumoconiosis on his Weibo account with a request for help.Footnote 48 His Weibo posts were promptly shared thousands of times and elicited a following of concerned netizens. Wang Keqin then launched the Love Save Pneumoconiosis charitable crowdfunding campaign on 15 June 2011. With the backing of the China Social Assistance Foundation, a national public-fundraising foundation governed by MCA, the mission of Love Save is to mobilize societal and governmental support for an estimated six million workers suffering from pneumoconiosis, and to improve the working environment conditions of miners to prevent the disease.

Between June 2011 and June 2014, Love Save attracted over 13.7 million yuan in donations, which helped over 1,000 patients receive medical care, and enabled children from 600 pneumoconiosis families to continue their studies.Footnote 49 Amid this outpouring of netizen support for pneumoconiosis patients and Weibo postings criticizing the working conditions leading to the disease, the initial governmental response was repressive. In rural Liaoning, cadres threatened volunteers investigating pneumoconiosis, and local police detained those unwilling to suspend their inquiries.Footnote 50

Although the central government has not issued any policy statements to reduce the incidence of black lung disease or assist its victims, Love Save has since achieved moderate success in policy advocacy at both the national and sub-national levels of government. Starting in 2012, the NHFPC, MCA and other central government departments organized symposiums with Love Save on how to support pneumoconiosis patients and their families. Furthermore, thus far 16 deputies of the NPC and delegates to the CPPCC have articulated the plight of pneumoconiosis patients publicly and at the two annual conferences. Moreover, an increasing number of local governments are cooperating with Love Save to develop institutional solutions for assisting affected families.Footnote 51 For example, both Meitan county in Guizhou and Anhua county in Hunan hired Wang Keqin in 2015 as a “pneumoconiosis prevention and treatment consultant.” The partnership between Love Save and various counties has had the stabilizing effect of convincing petitioners to drop their grievances against local governments for failing to ensure safe working conditions. At the national level, in December 2017 the NHFPC established a Pneumoconiosis Diagnosis and Treatment Committee to provide policy suggestions and offer technical support to the NHFPC. For these reasons, as of 2018, we regard the Love Save campaign as having achieved agenda-setting influence, but without impact on national labour policies that would reduce the incidence of pneumoconiosis, or national health or social welfare policies that assist affected workers and their families.

Support Relief for Rare Diseases

During the summer of 2014, the Ice Bucket Challenge went viral on social media in the US: people posted videos of themselves dumping ice water over their heads, and challenged others to do the same within 24 hours or make a donation to support research on amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), a rare neurodegenerative disorder also known as Lou Gehrig's disease. The Ice Bucket Challenge attracted self-dunking videos by several high-profile figures, including Justin Bieber, George W. Bush, Lady Gaga, Bill Gates and Mark Zuckerberg.

Riding this wave of digital enthusiasm, on 17 August 2014 the Support Relief for Rare Diseases crowdfunding project was launched on Sina Weibo by the China-Dolls Center for Rare Disorders (CCRD), a foundation under the China Social Welfare Education Foundation.Footnote 52 One day later, the CEO of mobile phone maker Xiaomi, Lei Jun 雷军, introduced the Ice Bucket Challenge to Weibo. Gu Yongqiang 古永锵, the CEO of Youku.com and Tudou.com (China's equivalents of YouTube), praised Ice Bucket as “a fantastic way to publicize rare diseases,” poured two pails of ice water on himself, and challenged Alibaba's CEO Ma Yun 马云 to do the same.Footnote 53 Within its first five days, the Rare Diseases campaign mobilized over 5.9 million yuan – more than it had raised during the entire year of 2013. Concurrently, netizens read about the Ice Bucket Challenge over 2.9 billion times and posted over 1.6 million comments about ALS on Weibo.

Emboldened by the surge in popular attention, on 28 August, CCRD issued a report urging the government to provide institutionalized support for ALS patients. By 30 August, Rare Diseases had raised 8.14 million yuan, of which 7.28 million was donated through its Sina Weibo micro-charity platform. Several organizations, including the China ALS Association, accused CCRD of opportunistically leveraging the attention generated by Ice Bucket to support patients with Osteogenesis Imperfecta (OI or brittle bone disease), which represented the focus of CCRD prior to the Rare Diseases campaign.Footnote 54 In response, CCRD indicated that out of the 8.14 million yuan mobilized though the Rare Diseases campaign, 5.57 million yuan (68.4%) was dedicated to ALS, while the remaining 2.57 million yuan was donated towards rare diseases in general.Footnote 55 CCRD opted to allocate the latter amount towards developing ALS-related NGOs and policy advocacy.

Ultimately, Rare Diseases mobilized 99.5 per cent of total raised funds within its first two weeks on Weibo.Footnote 56 Despite the brevity of concentrated popular interest, by 2016, CCRD had achieved incremental progress in a number of areas. First, on 4 January, the NHFPC established the Commission of Experts on Rare Disease Diagnosis and Protection (hanjianbing zhenliao yu baozhang zhuanjia weiyuanhui 罕见病诊疗与保障专家委员会) to support the basic medical needs and rights of Chinese citizens with rare diseases.Footnote 57 Second, in February, CCRD's founder, Wang Yi'ou 王奕鸥, became the General Secretary of the newly established Illness Challenge Foundation, which represents China's first foundation devoted to assisting people with rare diseases and mobilizing policy advocacy and legislation at the national level.Footnote 58 Third, on 26 February, the China Food and Drug Administration (CFDA) issued “Suggestions on Prioritizing the Approval of Backlogged Drug Applications” (zongju guanyu jiejue yaopin zhuce shenqing jiya shixing youxian shenping shenpi de yijian 总局关于解决药品注册申请积压实行优先审评审批的意见), indicating that priority would be given to drug approval applications relating to seven types of medical conditions, including rare diseases.Footnote 59 Meanwhile, CPPCC member Ding Jie 丁洁 has been an outspoken advocate in focusing national attention on rare diseases and incorporating the treatment of rare diseases into the national health care system.Footnote 60 Resulting from these efforts, the National Committee for Disease Control, Treatment and Prevention is compiling an official catalogue of approximately 100 rare diseases whose treatment will be covered by health insurance.Footnote 61 While CCRD and other NGOs representing rare diseases had been lobbying for policy measures since the mid-2000s, it was not until the Ice Bucket Challenge and Rare Disease micro-charities spawned intense popular support that the NHFPC and other central authorities began to embrace the inclusion of rare diseases on their policy agendas.

China Water Safety Project

Launched on Sina Weibo in 2013 by the founder of Free Lunch, Deng Fei, the China Safety Water Project (CWSP) is hosted by the China Social Assistance Foundation and aims to promote cooperation among governmental, corporate and societal organizations in monitoring and treating polluted bodies of water. As of 15 November 2017, CWSP had raised 1,223,311 yuan from 40,775 donors, making it the largest micro-charity related to environmental protection listed on Sina Weibo to date. CWSP's project goals include:

• establishing an electronic national map of water sewage to increase public awareness about the location and sources of water pollution;

• inspiring activism in reporting polluted water and protecting water supplies;

• supporting victims of water pollution through financial subsidies, legal assistance, and environmental public litigation;

• enhancing the capacity of businesses to treat water pollution; and

• raising water safety standards at the national level.

Thus far, funds raised by CWSP have enabled creation of an electronic map showing water pollution,Footnote 62 and sponsorship of environmental public interest litigation. However, it has not made much progress in other stated goals, as its crowdfunding campaign lost momentum. The water pollution map has not been updated since August 2014, CWSP's information page on programme implementation has not been updated since May 2015, and 99.3 per cent of the funds donated to CWSP were raised by November 2015.Footnote 63 An interviewee explained, “Frankly, the governance of CWSP is dysfunctional. Its executive board struggles with daily operations, management is a mess, and there are not enough officers.”Footnote 64 Meanwhile, CWSP's Weibo and WeChat public accounts issue messages infrequently, and its official website has experienced technical difficulties, all of which limits their digital mobilization capacity.

Beyond these organizational issues, CWSP has faced difficulties in advancing its mission of increasing the accountability of key stakeholders in the production and monitoring of water pollution. Few factories have reformed their practices due to complaints about inadequate funds and technology for eradicating pollution. Likewise, most local governments have either ignored or responded defensively to CWSP's requests for partnership. Shandong province, for example, initially resisted CWSP proposals but then invited Deng Fei's assistance. However, Shandong's Bureau of Environmental Protection subsequently accused Deng Fei on Weibo of presenting an inaccurate account of a water pollution incident in Shandong.Footnote 65 Although water pollution is among China's most visible and widely experienced public problems, CWSP's crowdfunding campaign has yet to achieve agenda-setting, much less national policy influence.

Explaining differential impact

Taken together, aggregate analysis of Weibo micro-charities and the four case studies provide insight into the conditions under which issue-based crowdfunding on social media has contributed to agenda-setting or actual policy impact. Table 3 summarizes the policy goals and outcomes of the case studies.

Table 3: Summary of Charitable Crowdfunding Case Studies: Policy Goals and Outcomes

Source: Compiled by the authors.

Above all, successful campaigns have partnered substantively with government entities from the outset even if they were initiated by grassroots NGOs. This is evident in all 14 out of the 34 projects that achieved policy impact. Furthermore, among the 14 campaigns that have had tangible policy impact, all are concentrated in the areas of children's welfare, environmental protection and poverty alleviation. The 14 success cases are meaningfully supported – not just nominally hosted (guamin 挂名) – by public foundations with ties to the party-state. For example, the Left Behind Children's Partner Project, a programme that supports children who are not residing with their parents, was initiated by the China Foundation for Poverty Alleviation under the State Council's supervision. Various members of the foundation are retired cadres. Sub-national allies can be equally helpful, as seen in the Clean Water for Rural Children campaign initiated by the Sichuan Technology Foundation.

As earlier studies observed, many domestic social organizations in China seek to be co-opted by government-affiliated entities to enhance their visibility and legitimacy, a strategy Kevin O'Brien calls “entwinement.” NGOs operating in the “non-critical realm” of civil society do not threaten the party's political authority.Footnote 66 Hence, they may even serve as effective partners with the government in providing public services. During the government of Hu Jintao 胡锦涛 and Wen Jiabao 温家宝, private foundations and social service providers grew rapidly, and starting in 2010 exceeded the number of public foundations. Since private foundations are prohibited from “raising funds from the public,” NGOs seeking to launch micro-charities on Weibo need to be sponsored by public ones. The accessibility of public foundations for NGOs reflects the “ecology of opportunity” of their leaders.Footnote 67 The prospects of having agenda-setting or policy impact is enhanced to the extent that sponsorship by public foundations reflects genuine support for its mission rather than mere expediency.

Second, crowdfunding campaigns that amplify existing policy priorities with concrete proposed solutions are more likely to elicit a constructive governmental response than politically sensitive issues. Free Lunch represents the least controversial campaign. Improving the nutrition of rural schoolchildren is consistent with the central government's commitment to poverty alleviation. Prior to the launching of Free Lunch, Beijing had already dispatched investigative teams to rural areas to understand the developmental health risks of impoverished children.Footnote 68 The resulting internal reports were shared with senior leadership. Subsequent outpouring of cross-provincial, local government support for Free Lunch spurred the central government to accelerate consideration of a national rural nutrition programme.

By contrast, issues resulting from corporate and/or governmental negligence – for example, in the case of occupational diseases – are more likely to encounter resistance. Love Save initially elicited a defensive reaction from local governments with large pneumoconiosis populations due to concerns about social instability. Demands for remediating occupational safety violations and compensating affected households felt adversarial and threatening to local finances. Once local governments realized that supporting Love Save could mollify petitioners, however, initial reticence gave way to partnership. Appealing to political pragmatism is more effective than political confrontation.

Third, initial viral support for a charitable crowdfunding campaign may mobilize public concern – but is not sufficient – for garnering governmental action. China Dolls leveraged the popular Ice Bucket Challenge into support for its Rare Disease project on Weibo. Although most of Rare Disease's funds were donated within the first two weeks of the campaign, China Dolls invested them towards the establishment of a private foundation dedicated to rare disease research, treatment, and policy advocacy. Water Safety similarly attracted most of its Weibo contributions during the campaign's initial phase but floundered in the absence of sustained and organized commitment from its leaders. Even when a campaign rouses popular fervour and possesses sympathetic allies within the party-state, effective communications and management are required for project implementation.

Conclusion

Online charitable crowdfunding in China represents an increasingly popular medium for netizens to mobilize awareness and financial support of various issues.Footnote 69 Some observers refer to such campaigns as “subversive charities” and believe they represent a novel form of political participation:

[M]icro-donations – made online – cast “votes” of support for the cause at hand and are a cover for an implicit rebuke of the government…these campaigns have evolved beyond being simple charity projects into outlets for democratic exercise and citizen empowerment.Footnote 70

Our analysis of public interest micro-charity projects on Sina Weibo found that less than 20 per cent are associated with explicit policy aspirations. But among those policy-oriented projects, over two-thirds have had either agenda-setting influence and/or policy impact thus far. This is a higher rate of influence than anticipated at the outset of the study; and it is conceivable that some of the remaining 32 per cent of projects lacking impact could eventually make progress by attracting the attention of local governments, CPPCC and NPC delegates and/or relevant bureaucratic ministries. The case studies indicate that charitable crowdfunding has increased the transparency and responsiveness of the government in certain issue areas. By triggering an upsurge of public support and elevating issues prioritized by the government, micro-charities may serve as an input institution in the spirit of “responsive authoritarianism.” Both the Free Lunch and Rare Disease campaigns created a sense of urgency for a policy response. While these findings could be interpreted as evidence of social media's pluralizing effect on China's policy process, we do not believe that charitable crowdfunding has expanded the actual space for civil society. The rationale for this guarded assessment is as follows.

First, our database of 188 public interest projects on Sina Weibo represents issues that lie within the increasingly circumscribed boundaries of politically permissible topics. There is selection bias by research design. If a project reaches the point of being listed on Weibo, then it is by regulatory necessity hosted (guamin) by a public foundation, thereby signalling some degree of official approval, or at least lack of censorship. Hence, in China's authoritarian context, projects operating in the critical realm of civil society will not appear among the branded/public interest projects on Weibo.

One such example is Food Delivery Party or FDP (songfandang 送饭党), which crowdfunds to support family members of political prisoners, including those of Xiao Yong 肖勇, Xu Wanping 许万平, and the late Liu Xiaobo 刘晓波. Co-founded in 2011 by blogger Rou Tangsen 肉唐僧 (“Meaty Monk”) and rights activist Guo Yushan 郭玉闪, FDP raised donations from over 100,000 supporters through its Butcher Shop on Taobao.Footnote 71 In October 2013, however, Beijing Public Security placed Guo Yushan under criminal detention, and both the Taobao Butcher Shop and related Weibo accounts were suspended. FDP is indeed a “subversive charity,” but both online and offline security agents catch up swiftly with individuals and organizations contesting regime authority.

Meanwhile, less overtly threatening campaigns are censored well before they could become listed as public interest micro-charities. For example, in March 2016, Weibo started suspending accounts with usernames including the term nüquan (女权), which translates directly as “women's rights” and denotes “feminism” (nüquan zhuyi 女权主义).Footnote 72 The Feminist Action Group, Delicious Feminist Movement and several other Weibo blogs were terminated or had their posts deleted. This username restriction then extended to micro-charities on Weibo. That same month Zhang Leilei from Guangzhou initiated a crowdfunding project entitled, “I am an advertising board, marching to protest sexual harassment” (woshi guanggao pai, xingzou fan saorao 我是广告牌,行走反骚扰). Her campaign received over 40,000 yuan within two months before Sina Weibo suspended it as well.

The advent of Weibo may have emboldened multiple societal interests to engage in charitable crowdfunding and policy advocacy, but they too are constrained by boundaries of the political moment. Thus far, the 14 micro-charities that have succeeded in promoting policy reforms have all been in the fields of children's welfare, environmental protection and poverty alleviation. Several of these have been led by investigative reporters who are able to frame issues in terms that appeal to the common goal of improving governance. Maria Repnikova describes the “relationship between critical journalists and central authorities as a fluid, state-dominated partnership characterised by continuous improvisation.”Footnote 73 Anthony Spires similarly observes that the party-state relates to service-oriented NGOs in a delicate condition of “contingent symbiosis,” meaning that local officials permit unregistered grassroots groups to operate when they serve mutual objectives. On Weibo, however, implementation of real-name registration requirements makes it more challenging for groups to blog about sensitive issues, and the guamin requirement for charitable crowdfunding signals the parameters of politically acceptable versus unacceptable topics. The latter crowdfund through Taobao using creative means, such as selling one-page “thank you notes” for 1 yuan. Others resort to posting individual projects that lack broader mobilizational intention and capacity.

Finally, although this study identified several successful cases of agenda-setting micro-charities, social media is only one of the channels through which issues become defined as public policy concerns. Online activism and fundraising complement, rather than substitute for, offline activism in contemporary China. Certain campaigns may go viral in a concentrated period, but after the frenzy, they still require in-person negotiations with relevant agencies and officials for effective implementation. Meanwhile, campaigns that go viral in a politically concerning manner become censored. Going forward, further research is warranted to understand the evolving relationship among netizens, central and local governments, and the private internet companies that provide (or deny) the space for those engagements.

Acknowledgement

Research for this project was supported by a General Research Fund grant (#16602916) from the Hong Kong SAR Research Grants Council. The authors gratefully acknowledge the research assistance of Warren Wenzhi Lu, and constructive feedback from Yongshun Cai, Franziska Keller, Warren Wenzhi Lu, Jeff Wasserstrom, participants at the International Workshop on Governance in China held at University of Duisberg-Essen, and three anonymous reviewers on earlier drafts of this paper.

Biographical notes

Qingyan WANG is a graduate student in the Division of Social Science at Hong Kong University of Science and Technology. Her research focuses on media politics in China.

Kellee S. TSAI is dean of humanities and social science and chair professor of social science at Hong Kong University of Science and Technology.

Appendix A: Anonymized List of Interviewees

Appendix B: Regression Results

Table B1: Potential Variables Predicting Policy Aspiration

Table B2: Potential Variables Predicting Policy Impact