Within our churches we find ourselves shocked by news of abuse – sexual, financial, spiritual, physical, and institutional. We set up committees, independent reviews and projects to prevent further incidents and are again shocked when they are again uncovered. Other unacceptable behaviours are part of the life of our churches in less reported ways also, such as letting people understand that they may no longer contribute, do not belong, are not welcome. These behaviours might even seem to be pragmatically anticipated, with the range of thea/ological perspectives cited as justification.

Among the theological analyses of why unacceptable behaviours occur and continue, there is recognition that words influence our behaviour. While the influence of words on behaviour is clear when we consider commands, invitations, requests and the like, there is a claim that the words we use to and for the divine can promote unacceptable behaviours. From at least Mary DalyFootnote 1 to Gina MessinaFootnote 2, feminist scholars have drawn attention to the link between the traditional words to and for the divine (for example, ‘Father’, ‘Lord’, ‘King’, ‘He’) and the unacceptable behaviours within patriarchy and other controlling ideologies. Yet, despite the scholarly analyses and multiple examples of lived experience, within our churches we continue to use the traditional words; any change is disputed, and alterations put forward by church institutions, however well intentioned, are cosmeticFootnote 3 or take gender-neutral language options but do not challenge hierarchy.Footnote 4

I argue that one of the reasons that we do not change the words we use to and for the divine is that we do not fully understand how words work and how they influence us towards behaviours. It is not enough to notice that words and behaviours are bound together; we must also understand both why it is important to change the words because of how they are bound to behaviours and the extent to which change must occur. I also argue that by better understanding how words and behaviours are linked we can change our usage of words sufficiently to challenge and even break the links that promote unacceptable behaviours, thus contributing towards reducing unacceptable behaviours. I make no claim that understanding of and change in words is the only approach that is required to reduce bad behaviours; philosophy, psychology and social science, and other disciplines all contribute significantly (although even within these fields paying attention to the words remains pertinent).Footnote 5 However, particularly within thea/ology, I argue that such change is more significant than has been widely understood.

While there are other valuable linguistic contributions, I offer here, as a novel contribution to thea/ology, a synthesis of approaches and tools for analysis which concatenate to provide critical and effective understanding of how words and behaviours are connected and of how to change them. Firstly, Teun Van Dijk exposes ways in which ideologies make use of language.Footnote 6 Secondly, Judith Butler indicates the ways in which our identities are constituted within language.Footnote 7 Thirdly, psycholinguistic findings demonstrate how we process language. And, finally, Ludwig Wittgenstein, showing that thought can be led astray by language, indicates the significance of how we use words and that we need to consider how words gain meaning.Footnote 8 These ways of examining language will then be applied to words to and for the divine to show how they influence our behaviour to each other.

How do words influence our behaviour to each other?

Since Destutt de Tracy coined the term ‘ideology’ in 1796 it has provided fertile ground for thought and analysis.Footnote 9 Here, ideology is taken to be a system of ideas having sufficient coherence to be maintained within a community at a given time.Footnote 10 However, and pertinently, ideologies are not only ‘systems of ideas … but also … social practices’.Footnote 11 They are maintained because they have sufficient internal coherence to enable an individual to take on the practices or behaviours of the ideology. It is not that a particular ideology is of interest at this point, but rather that there is a relationship between language and ideology. Ideas are expressed in words and so words and their uses can be examined to reveal the ideologies that inform them. This is explored in detail by van Dijk, who asserts that ‘[o]ne of the crucial social practices influenced by ideologies are language use and discourse’Footnote 12 and that ‘[i]deologies are largely acquired, spread, and reproduced by text and talk’.Footnote 13 These assertions apply to words to and for the divine as much as to other words. While the patriarchal and patrikyriarchal ideologies themselves have been critiqued by feminist thea/ologians,Footnote 14 use of van Dijk's work is helpful because it demonstrates how words are tied into these damaging ideologies and not only express and maintain them but can also challenge and even change them.

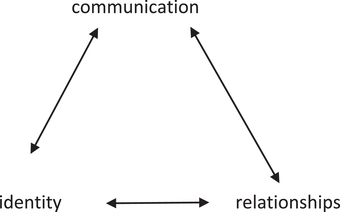

Secondly, Althusser drew attention to the ways that dominant ideologies maintain their power structures by using words to form people who will support those power structures.Footnote 15 This process he called interpellation, and Butler takes this idea and expands on it to show that we are ‘constituted in language’.Footnote 16 While accepting that we are physical bodies, there is a significant sense in which we become ourselves in and through language.Footnote 17 The words used to us and about us provide us with an identity – a way of being in the world that affects how we relate to each other, particularly when power relations are given in the words. We may to a greater or lesser extent accept the identities given/assigned to us or become ourselves in contradistinction to them. While Butler has established this influence in terms of words used to us and about us, I propose that words we use to and for others also constitute us. This occurs because of the interactions between communication (including the words we use), relationships and identities. This interaction is indicated in the model at Figure 1.Footnote 18 As we use words to and for others, we indicate something of the relationship we hold with that other and something of the identity we have within that relationship. The significance of this approach is that it indicates that the words we use to and for others, including the divine, will constitute us into identities and relationships, thus influencing our behaviours through the social practices encouraged by the ideologies expressed and maintained in those words.

Figure 1. Communication, identity, relationships model from Metcalfe, (2020) p.142.

I have used these first two approaches to examine the significance of words for our behaviour to each other because of the ways in which we are formed by words and called into social practices (patterns of behaviour) by words. I have used the third and fourth approaches to show how words can become unnoticed, to indicate some reasons that changing words can be difficult and to remind us that our uses of words are in themselves a behaviour. The third approach draws on findings within psycholinguistics concerning the processes that occur as we hear and use language. Our processing of language is extremely fast and largely subconscious.Footnote 19 We become aware of the need to work at understanding words when technical vocabulary with which we are only just familiar is used or when we use a second language in which we are not fully fluent. However, with familiarity, language processing eases remarkably quickly. This indicates the significance of familiarity and frequency for processing words because when words are familiar and heard or used frequently, we process them quickly and fluently without need for specific attention to them.Footnote 20 We also tend to maintain the use of familiar and frequent words.Footnote 21

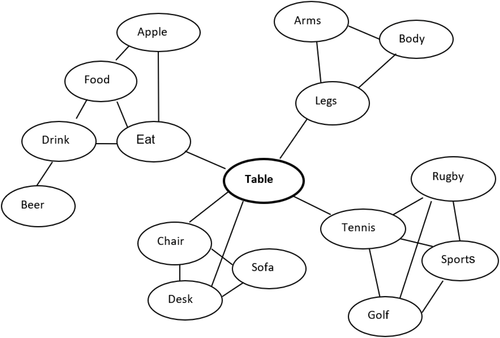

Words are not used in isolation; so, as we hear and use words frequently, we hear and use them in association with other words. Some of these associations will become familiar and almost assumed (as indicated by pairs of words, for example, fish and chips, table and chair, hot and cold). Such associations may be with related words, as seen in these examples, but may be with words often used together (for example, health and service, block and flats, climate and change). Associations can depend on context, for example, in the British parliamentary system ‘Lord’ is associated with members of the upper chamber but in the Christian faith ‘Lord’ is associated with Jesus Christ, with God, with Father, and, as in the liturgical texts for Holy Communion, with Holy Spirit.

These associations can be mapped and represented within a network. An oversimplified network is offered at Figure 2 for the word ‘table’.Footnote 22 This shows some of the variety of links and associations that can be revealed, given the ways we use words. However, this tool can also help reveal ideological influences at work in words, as will be seen when the tool is applied to words to and for the divine. Ideological influences are particularly relevant for the words to and for the divine that are familiar and used frequently because these are used almost automatically, thus maintaining the uses and their influences.

Figure 2. A simplified semantic network for the word ‘table’ based on Lerner et al., (2012).

Many of the words used to and for the divine are metaphors. There are two key findings from psycholinguistics which contribute to our understanding of metaphors alongside other approaches.Footnote 23 Firstly, Rachel Giora found that the literal meanings of words are activated prior to metaphorical meanings.Footnote 24 Secondly, Sam Glucksberg suggests that there is a sense in which metaphors can be taken literally.Footnote 25 Using the often-implied structure of metaphors (‘X is a Y’), he proposes that we understand metaphors through the creation of ‘categorical assertions’ which link X and Y, showing what is common between them. Consideration of the categorical assertions for metaphors helps indicate what is understood when metaphors are used.

These findings from psycholinguistics (the impact of familiarity and frequency, examination of associations in semantic networks, and understandings of metaphors) contribute to our analysis. They show that frequent and familiar words tend to become used without reflection and are thus maintained, making the ideological influences that are present more difficult to notice.

The fourth and final approach to language comes from Wittgenstein's later work. In this article I contribute a specific application of Wittgenstein's insights to words to and for the divine, rather than a focus on the broader theological reflection provoked by his work.Footnote 26 Wittgenstein holds that language exists as a social phenomenon, alongside but not linked to that about which we speak.Footnote 27 Words gain meaning in use rather than in themselves; words on their own cannot give us much of an idea of what they mean.Footnote 28 For example, the word ‘table’ could be used to warn us to avoid a table, ask us to lay a table for a meal, instruct us to draw a mathematical table, encourage us examine the water table – or in many other ways. The meaning is not clear unless the word is heard or seen in use. Another aspect of the use of words is that the ways in which words are used are, in themselves, behaviour. This is not to reduce the significance of abusive or exclusory behaviour but to recognise that word use is behaviour both because speaking is a physical act and because words are used to achieve or ‘do’ something, either in the conversation or beyond it.Footnote 29

A further insight from Wittgenstein is that the pictures in the words we use suggest the ways in which we are to use them.Footnote 30 We learn to use words within our communities and the pictures in the words we learn incline us towards using them in particular ways, at least most frequently.

Wittgenstein's understanding of meaning being found primarily in use is not the only approach to understanding how words gain and convey meaning. An alternative is to understand words as representative, as ‘standing in’ for things in the world and as providing meaning in themselves, inclining towards an understanding of words as giving us access to things in the world as they are.Footnote 31 When a representational understanding of how words gain meaning is held, the reasons for reflection are not only further reduced but also discouraged because the words give us our understanding of the world. Representational understandings reduce the need for examination of words and maintain uses of words. They also help dominant ideologies of oppression appear less obvious by ‘making them seem inevitable’Footnote 32 because the words are likely to be seen as representing reality.

From these four approaches, I argue that some words and the ways in which they are used influence our behaviour to each other because they are ideological tools, constituting us into identities and relationships and giving us patterns of behaviour. Many words escape notice because they are used almost automatically, the pictures in them cohering with the ways they are used to make their use and meaning seem clear and obvious.

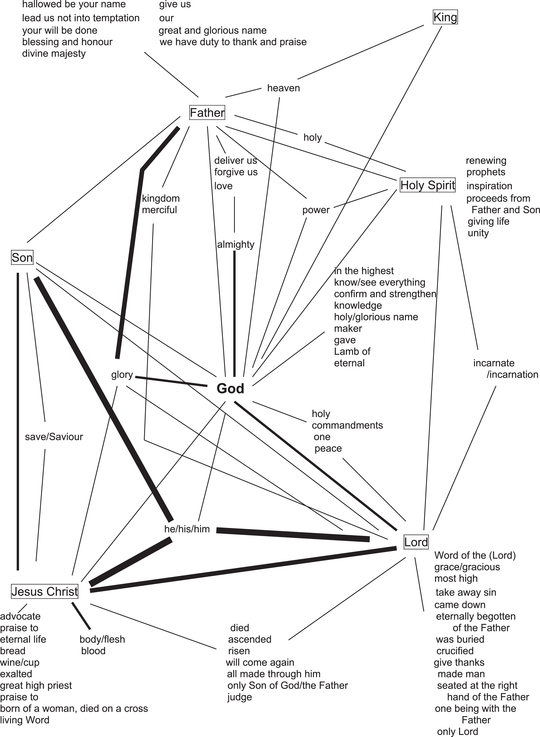

Having described the tools for analysis and briefly indicated some of the interactions between them, I will now show what they reveal when applied to words to and for the divine. Since the focus of this work is words to and for the divine, and, since, following Wittgenstein, it is important to examine language in use, I chose to study texts frequently used in worship in the Church of England: the liturgical texts for Holy Communion.Footnote 33 In the established church, these texts and so, the words to and for the divine within them, are familiar, accepted and used without reflection at the central Christian celebration.Footnote 34 To identify the most common words used to and for the divine within the liturgical texts for Holy Communion, the frequency analysis within the WordSmith application was used with the texts. This shows that the most common words are ‘Lord’, ‘God’, ‘Father’, ‘Jesus Christ’, ‘Son’, and the male pronouns.Footnote 35 I will refer to these as the traditional words to and for the divine. In this article, the liturgical texts are the resource of words to study rather than the focus of study themselves.

When tools from psycholinguistics are applied to the words to and for the divine, the frequency analysis is of note, as is the exploration of associations.Footnote 36 By representing these words within a semantic network, see Figure 3, (with the frequency of associations indicated via lines of different thickness), we can see that the text gives us a predominantly powerful divine, with relatively little love.Footnote 37 The frequency of use indicates the words that are particularly familiar and therefore processed quickly and easily when heard in relation to the divine. This network helps to reveal what is understood when traditional words to and for the divine are used. These patrikyriarchal words, familiar and maintained in use outside as well as within the texts, when put alongside van Dijk's observations of the ideological influences on language, begin to demonstrate the ways in which dominant ideologies retain significance within a church community. The ideological influences are embedded in the familiar and frequent uses of words that have become almost automatic, enabling ongoing uses of the words, thus maintaining the influences. Such ongoing use has a basis within the processing of language as well as in other theological perspectives. These words also indicate the identities and relationships of dominance and submission into which worshippers are constituted. While these are clearly not the only identities and relationships at work for any particular individual, for people attending worship regularly, they will be significant, at least within the context of church belonging.

Figure 3. Semantic Network for God in the liturgical text for Holy Communion. Elizabeth, (2016), p. 54.

From the psycholinguistic contribution to understanding metaphors, Giora's finding that the literal meanings of words are activated prior to metaphorical meanings shows that the literal meanings of, ‘Father’, ‘Lord’ and ‘King’, will be active when accessing the metaphoric meanings. This embeds associations of male and (particularly with ‘Lord’ and ‘King’) of male hierarchy and power as these words are processed. Glucksberg's work on categorical assertions shows that many of the traditional metaphors used to and for the divine contain understandings of male authority and of power understood as power-over.Footnote 38

As an aside here, it may be argued that, however we understand the words, we must always remember that words to and for the divine are analogous. While I do not offer an argument against analogy as a way of understanding words to and for the divine, when the traditional words receive reflection on their ‘highest’ sense, such reflection will predominantly be on words indicating male power. This further embeds patrikyriarchal understandings and influences. While the category of analogy is useful as a way of understanding how we can speak of the divine at all, reflection remains needed on the words used, their frequency, their ideological basis and the identities and relationships into which they constitute us.

Applying Wittgenstein's understanding of language reminds us that in common with all other words, words to and for the divine gain and convey meaning through being used. This perspective is to be held alongside the ways that pictures in words incline us to use them in certain ways. In many of the frequently used traditional words to and for the divine (particularly, ‘Father’, ‘Lord’, and ‘King’) and their associations (for example, ‘almighty’, ‘majesty’, ‘great and glorious’, ‘power’, ‘most high’), male power is present. Given these pictures it is hardly surprising that the liturgical texts for Holy Communion use words to and for the divine to proclaim authority (for example ‘In the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit’, ‘This is the word of the Lord’) and to assume a response of obedience because commandments are given by ‘Lord Jesus Christ’. Other uses are to appeal for forgiveness, to command the congregation, for the congregation to show obedience to the priest's command, to show obedience to Christ, and to set parameters for life.Footnote 39 This gives a further indication as to how dominant ideologies are maintained, because the words show us how to use them (further supporting the use of the words becoming almost automatic). Familiarity of use will incline us to maintain those uses outside the context of the texts as well as within them.

Alongside these ways that language functions, if a representational understanding of language is held, words are understood as providing meaning in themselves and this leads to understanding words to and for the divine as giving us access to the divine as the divine is. This is another part of indicating why change in the words (and therefore the behaviours) is difficult because raising words to and for the divine for reflection, can be seen as disputing the being of the divine. With representational understandings of language, when the divine is called ‘our Father’, a belief can grow that the divine actually is our Father.Footnote 40 Such an understanding leads to resistance to change because if the words change, we will be speaking of a different divine. Our understandings of language and of how words gain meaning, particularly when unexamined, can be part of how we react to proposals of change from the traditional words to and for the divine. I suggest that ideologies of dominance and oppression might be well-served by representational understandings of language.

The words we use to and for the divine place us in relationship with the divine, providing an identity in relation to that divine. If the divine is Lord, we are servants; if the divine is Father, we are children; if the divine is King, we are subjects. These are relationships of dominance and submission. The words also place us in relationship with each other in our corporate relationship with the divine and give us identities in relation to each other. These identities and relationships influence our behaviour to each other. Farley examined the word ‘servant’ in terms of the way it is used for women and for men and the impact of it on behaviour.Footnote 41 She shows that there are not only hierarchies of dominance and submission between the divine and people, but also, and significantly for our behaviour to each other, among people. Farley's work was developed by Catherine LaCugnaFootnote 42 and is reflected in the examination of women and preaching by Elizabeth Shercliff.Footnote 43

Within the patrikyriarchal ideologies expressed and maintained in the traditional words to and for the divine, the relationships are predominantly of dominance and submission within hierarchies of power. Behaviours will be shaped by these hierarchies, proposing that powerful men can exert authority over others who are expected to submit. The degree to which individuals are constituted by the ideologies will lead to different sorts of behaviours, but dominance and submission are the expected pattern seen in a variety of ways, as given in the examples from feminist thea/ologians and others.Footnote 44

How do words to and for the divine influence our behaviour to each other?

I have argued that words influence our behaviour through the interactions between the four approaches, modified through the communication-relationships-identity triangle. This influence is also true for words to and for the divine. The traditional words to and for the divine that largely represent patrikyriarchal ideological values, are familiar and used frequently and therefore are processed so quickly as to usually be used without reflection. Through hearing and using these words we are constituted into relationships of dominance and submission, both with the divine and with each other. The frequent use of these damaging words is facilitated by the ways language is processed because familiar words and their associations have strong, almost automatic pathways that both facilitate ease of understanding and promote ongoing use. The pictures in these words also promote dominant or submissive uses of the words and contribute to maintaining patrikyriarchal influences on behaviour.

Use of the traditional words persists, partly because of the ways in which language functions, despite the evidence from feminist scholarship that the traditional words contribute to negative experiences and relationships. While there is no mechanical influence from words to behaviour,Footnote 45 and so no mechanical influence from words to and for the divine to behaviour, the traditional words to and for the divine constitute us into patrikyriarchal ideologies promoting behaviours of submission and dominance.Footnote 46 Despite these often harmful hierarchical relationships, reflection on the traditional words to and for the divine that challenges their use is uncomfortable to the point of being resisted, partly because if the words change, our identities and relationships will change, and any sense of certainty about ourselves, others and the divine can be destabilised. Theological arguments against change from the traditional words to and for the divine have been made, resisting the concerns raised by feminist scholars.Footnote 47 I am focussing on language, the ways in which word use influences behaviour, the ways in which change from the traditional words is resisted, and the ways in which, by understanding how the words influence behaviour, change in the words and therefore in the behaviours can be encouraged.

Using alternative words to and for the divine offers hope for challenging the dominant ideologies because ‘social power abuse, such as racism and sexism, is … resisted by text and talk’.Footnote 48 Since language is significant for learning and maintaining ideologies, changes within language have the potential to bring change in the ideologies.Footnote 49 Our ability to use words provides a reason for hope because word use can be a locus of resistance. There is also hope because individuals, to use Butler's word, ‘exceed’ the identities they are given by ideologies, highlighting the potential for the ‘saying of the unspeakable … speaking in ways that have never yet been legitimated’.Footnote 50 Language offers an insight into the vulnerability at the heart of any ideology and, as Butler points out, the key structure of interpellation is also vulnerable because ‘[t]he workings of interpellation may well be necessary, but they are not for that reason mechanical or fully predictable’.Footnote 51

Neither in findings within psycholinguistics nor in insights from Wittgenstein is there any reason to prevent change in words to and for the divine, as is seen in the development of new words in thea/ological reflection.Footnote 52 While patrikyriarchal ideologies are maintained by continuing the use of words, including the traditional words to and for the divine, words are used within communities and can be changed. As Butler comments, ‘[l]anguage ranks among the concrete and contingent practices and institutions maintained by the choices of individuals and, hence weakened by the collective actions of choosing individuals’.Footnote 53 This makes word change an act that is possible for anyone who so chooses because word use is a choice and a choice to be made by everyone using words. Even Christianity, as a religion and thus said to be supporting the ideological systems in which it belongs,Footnote 54 is primarily communicated and maintained in words; words can be changed, bringing new identities and relationships to challenge the dominance of patrikyriarchal ideologies.

Since ideologies are maintained in words, if words other than the traditional words are chosen and regularly used within a community, the traditional words will be weakened, and the ideologies informing them will be challenged. Wittgenstein comments that ‘if we clothe ourselves in a new form of expression, the old problems are discarded along with the old garment’.Footnote 55 While the significance of ideologies is not to be underestimated and the predominance of patriarchy is undoubted and multiply woven into society, yet patriarchy is an ideology, subject to the structural vulnerabilities of all ideologies which can be exploited against it.

The hope I offer is that word production is not predetermined, and choice is available. Even words that appear to be automatically produced are only a different form of control.Footnote 56 This hope is not rhetorical or distant but incarnate in our constitution in words and our abilities to use words. It is small and practical because words are available to all of us, but words can reveal questions that in turn reveal the injustices in the only sufficient coherence of patrikyriarchy.

If we can learn to become aware of the familiar and frequent words that are used, the ways in which they are used, and the ideologically influenced identities and relationships into which we are constituted by them, we will be better able to explore change in words to and for the divine. Given the community use of language, change will need communities to understand and work with possibilities. A community willing to reflect together could begin by considering behaviours they wish to encourage, reflecting on the identities and relationships within which these behaviours would flourish, the ideologies that create such identities and behaviours and the words that reflect these ideologies.Footnote 57 This approach can be applied to and beyond words to and for the divine and clearly must extend beyond gender-based analyses. Racism and heterosexism are obvious applications and have begun to be discussed in terms of words to and for the divine: at least ableism and classism (much less discussed) must also be considered.Footnote 58

Accepting the significance of communities, I propose that it is not only communities who can contribute to changing words to and for the divine from ideologies of dominance and submission to ideologies of flourishing and possibility. Individuals involved in writing and teaching thea/ology also have a role to play in changing our praxis. By becoming aware of the significance of ideology within language, the identities and relationships into which some words constitute us, the ways in which words and their associations are used and the ways in which words gain meaning, assumptions can be revealed and questioned, and proposals assessed. I argue that thea/ologians have a responsibility to ask how the words they use or propose for the divine will constitute the readers / hearers and users of those words and what behaviours would be encouraged or sanctioned by their words. I do not argue for a specific name or set of names to be used, partly because ‘the divine names are innumerable’,Footnote 59 partly given the significance of intersectionalityFootnote 60 and partly because language is used within communities with variety between communities, at least to some extent, in associations and semantic networks. I do not believe that it is appropriate for one person to recommend words to and for the divine that are to be taken and used universally, particularly this white, middle class, middle aged, non-disabled, and cis gender thealogian. Instead, I would hope that multiplicities of life-affirming words could be proposed or developed and shared within and between communities, offering each other resources for prayer and praxis to open new possibilities that we cannot discover independently. I welcome the specificities of writers such as DalyFootnote 61, McFagueFootnote 62, and JohnsonFootnote 63 alongside the exploratory possibilities of Esther McIntoshFootnote 64 but do not seek to limit word use to any particular suggestion.

Work for change in words to and for the divine also has implications for wider thea/ological practice. Change in these words that takes account of ideological influences and how they are represented in word use will lead to reflection not only on the being of the divine but also at least on our understandings of Christology, pneumatology, thea/ological anthropology, soteriology, ecclesiology, thea/ological ecology, and eschatology.

I maintain that alongside the range of work that must be done to understand and reduce abusive, alienating and otherwise unacceptable behaviours, changing words to and for the divine from the traditional words to a diversity of open, liberatory words is a priority for thea/ologians and for Christian communities. Behaviours are influenced by word use and so word use, including but not limited to words to and for the divine, must be carefully examined to see how unacceptable behaviours are maintained and can be changed. There is much work to be done and it will not be easy but as we begin to analyse, understand, and reflect on the words we use so that behaviours are influenced positively, the possibilities are life-giving and transformative.