Older people are not a homogeneous social group. Their needs and abilities, and the costs associated with providing for their well-being, vary with their socioeconomic status, gender, geographic location and health status, among other relevant dimensions of difference. It should come as no surprise, then, that older adults are not a politically homogeneous bloc, either. In public and policy conversations there is very often a tendency, however, to assume that older people are a singular pressure group that will act through the political system to secure a distribution of societal resources that primarily benefits them – as retirees, health care consumers, people without young children in the house, and the like. If governments fail to invest in policies that can promote well-being across the life-course, and instead focus on maintaining social expenditure on the current generation of older people by squeezing current workers/future retirees, the story goes, it is because most governments are subject to greater pressure from older voters than from younger citizens, because the former vote at higher rates and are represented by powerful lobby groups. This argument was memorably summarized by the late British journalist Henry Fairlie, writing in The New Republic in 1988, as a problem of ‘greedy geezers’ living well at the expense of the young (Reference FairlieFairlie, 1988).

This chapter evaluates the argument that governments implement packages of policies that are favourable to older people, but that are societally sub-optimal, because of political pressure from older voters. It begins by laying out the core premises of the ‘greedy geezer’ narrative: because pension transfers, high-cost medical care and policies that protect transferable assets like housing are highly salient to older people and to their advocates, intense preferences for these types of policies communicated to politicians and policymakers will eventually crowd out other, more societally optimal policies. Examples of this narrative in national-level political debates in the UK, Germany, Italy and the USA are presented alongside evidence that many international organizations have also largely accepted the narrative’s premises. The chapter next evaluates empirical evidence for and against the core claims of this narrative, drawn mainly from Western European countries where roughly similar party systems and policymaking environments have allowed for systematic analysis that transcends individual country and party cases. Weighing this evidence, the chapter concludes that older people and their organized representatives (e.g. pensioner parties, pensioner unions and advocacy groups) in some contexts do push for policies that are ‘greedy’ in the sense of being beneficial for older voters and/or their own children, but not for society as a whole. However, this phenomenon is far from universal: it is especially pronounced in the USA and the UK, but much less so in other national contexts.

The chapter goes on to demonstrate that the policy packages adopted by national governments are generally motivated by concerns other than appeasing older voters. Our core argument is that governments do not implement packages of policies that are favourable to older people but societally sub-optimal (because they lead to under-investment in younger people, health inequalities and higher health care spending) as a result of pressure from ageing voters and their organized representatives. This is an attribution error – albeit an understandable one, given that many scholars as well as policymakers and members of the public mistakenly assume that social policy choices result primarily from demands from the electorate. But several core features of democratic politics explain why this presumption is incorrect: most people don’t usually vote in their own interests; there is a difference between voting for parties and voting for policies; parties say one thing as marketing but often propose policies that are quite different; and parties’ manifesto promises are often different from what they actually do. The chapter concludes by arguing that characterizing older people as uniformly ‘greedy’ obscures the fact that inequality among older adults means that many need more support than they actually receive – a point that we take up in much greater detail later in this volume.

3.1 The ‘Greedy Geezer’ Narrative

The idea that older voters are responsible for imbalances in social spending priorities that benefit mainly current retirees is itself, well, old. While Fairlie’s 1988 New Republic article introduced the phrase ‘greedy geezers’ to the English-speaking world’s punditry, scholars had been making more sober claims about the influence of older people on social policy since the mid-1970s. In one of the first cross-national analyses of social spending in OECD countries in 1975, for example, University of California Professor Harold Wilensky argued that increasing allocation of social resources to older adults was a result of ageing populations that created not only a need for more welfare spending (mainly in the form of pensions), but also a political constituency to fight for that spending (Reference WilenskyWilensky, 1975). The 1980s saw the development of similar arguments by other welfare state scholars: Reference Pampel and WilliamsonPampel and Williamson (1989) found that in democratic countries the ‘political pressure of a large aged population’ was an important influence on spending; and Reference Thomson, Johnson, Conrad and ThomsonThomson (1989) posited the ageing of a politically powerful ‘welfare generation’ as the driving force behind the growing emphasis of welfare states on programmes for older people versus programmes for children from the 1970s onward. (Thomson would go on to assert more polemically that the ‘selfish generation’ that reached adulthood just after the Second World War had tailored welfare state spending for its own purposes, and at the expense of the young (Reference Thomson, Bengtson and AchenbaumThomson, 1993).)

Whether older people desire social programmes that benefit them directly, or because they want to protect their assets in order to pass them down to their children, the ‘greedy geezer’ narrative posits that welfare policy mixes emphasizing win-lose solutions – short-term benefits for older people at the expense of longer-term social investment – come about because of political pressure from older voters. Clements (2018) describes such a narrative in the UK, a country where rhetoric blaming older people has been particularly harsh: ‘Whether it’s the nasty sentiment that Brexit voters are a bunch of selfish old bigots whose demise can’t come too soon, or that Baby Boomers have been piling up problems for moaning Millennials, or that old people are just getting in the way with their “bed-blocking” and their unreasonable expectation that younger folk should subsidise their state pensions, free bus passes, TV licences and winter fuel allowances – again and again, we see generational disdain for older people’ (Reference ClementsClements, 2018). But even in other countries where the age cleavage is less politicized, similar public pronouncements are common. For example, a 2013 opinion piece in the Washington Post titled ‘Payments to our elders are harming our future’ (Reference Holzer and SawhillHolzer & Sawhill, 2013) was part of ‘A meme that has been bubbling up in the media for months’ and that ‘goes something like this: The elderly have it too good. They claim too much of the country’s financial resources and will eat their children’s—and grandchildren’s—breakfast, lunch, and dinner unless Social Security and Medicare are cut. The country can no longer afford to give seniors so much’ (Reference LiebermanLieberman, 2013). In Germany, meanwhile, recent reporting claims that ‘the data shows that young people feel they’ve been saddled with the problems of their parents and grandparents – and that their political future has been determined by an older generation […] “The politics we have now here in Germany are more for middle-aged people, Baby Boomers – not for the younger generation,” said Aaron Hinze, a 24-year-old working in health care in Berlin’ (Reference SchultheisSchultheis, 2018).

Midway between politics and scholarship, international organizations have themselves both bought into and promoted the ‘greedy geezer’ narrative, albeit more subtly. While older adults themselves are generally not blamed explicitly for hijacking the welfare state, population ageing is portrayed as a cataclysmic event for society because of the presumed-inevitable drain that ageing must place on social systems. The World Bank’s landmark 1994 report on pension policy, for example – a report that would go on to inform the Bank’s pension policy proposals for Eastern Europe and much of the developing world – was titled ‘Averting the Old Age Crisis’ (World Reference BankBank, 1994). The ‘crisis’ of demographic change, according to the report’s Foreword, ‘threatens not only the old but also their children and grandchildren, who must shoulder, directly or indirectly, much of the increasingly heavy burden of providing for the aged’ (World Reference BankBank, 1994, xiii). If this framing seems like a relic of the first, panicky decades in which population ageing emerged as a policy issue, though, consider that the International Monetary Fund stated in their 2004 World Economic Outlook, focused on demographic change, contained the caption ‘The last train for pension reform leaves in … ’ above a figure showing the year at which older voters would surpass 50 per cent of the electorate (IMF, 2004, 165). As recently as 2017, the OECD warned that ‘In order to implement the needed reforms popular and political support is needed. Cutting benefits, increasing contributions or raising the retirement age, however, are unpopular. Given the significant political clout of older age groups, pension reforms that limit benefits paid over longer periods might be difficult to pass’ (OECD, 2017, 17).

European-level intergovernmental organizations, too, have adopted this narrative. For example, in 2009 the European Commission’s Directorate General of Employment, Social Affairs and Equal Opportunities requisitioned a Flash Eurobarometer poll on intergenerational solidarity. The poll prompted respondents to consider a variety of ‘greedy geezer’ tropes, including ‘Young people and older people do not easily agree on what is best for society’, ‘Because there will be a higher number of voters decision makers will pay less attention to young people’s needs’, and ‘Older people are a burden for society’ (Gallup Reference OrganisationOrganisation, 2009). While the Commission’s intention was surely not to stoke intergenerational conflict, the fact that they were concerned enough to ask these questions in a public opinion poll suggests that their own framing of the issue of demographic change was influenced by a narrative that emphasizes the potential for intergenerational conflict resulting from the excessive demands of older adults.

What is the logic underlying the ‘greedy geezers’ narrative? We can think about social policy priorities, like other goods, as being produced following an interaction between demand and supply. In this case, demand for policies comes from voters and organized interests, while the supply-side of the equation stems from politicians’ desires to gain or remain in office. The ‘greedy geezers’ narrative starts with a demand-side assumption that social policies such as pensions, medical care and policies that protect transferable assets like housing and financial wealth are so salient to older people and their advocates that they tend to crowd out other social policy preferences that might exist in the electorate. If this assumption is correct, then we would expect to see differences in public opinion and political mobilization between older and younger voters when it comes to key social and economic policy issues. We would expect older people to support policies that are in their immediate interest, and not in the interests of younger people. Organized interests acting on behalf of retirees – for example, pensioners’ unions, pensioner parties or lobby groups representing seniors – would also be expected to advocate for win-lose policies that protect the immediate financial interests of current elders, including protecting their assets so that they can be passed down to their descendants.

The supply of policies, in this logic, depends on politicians being exquisitely sensitive to the perceived electoral power of older voters. Politicians may themselves be indifferent about whether win-win or win-lose policies are best, but they cater to the wishes of older people because the latter vote at higher rates than the young and/or because senior lobbies are perceived to pose a threat if angered. The notion of old-age Social Security pensions constituting the ‘third rail’ of American politics – ‘touch it, you’re dead’, electorally – exemplifies this aspect of the ‘greedy geezers’ narrativeFootnote 1. If this assumption is correct, we would expect to see parties with more older voters advocating more win-lose policies; evidence that political parties, candidates and ministers make win-lose policies in response to perceived pressure from older voters; and politicians seeking to minimize the visibility of their actions to older voters when they must go against their preferences.

The ‘greedy geezer’ narrative draws on some objective political realities, but it ignores others. As a result, it is partly correct, but also misleading. The remainder of this chapter demonstrates this by drawing on the recent published empirical work in political science. It is true that as populations age, older voters make up a larger share of the electorate, and many of them do place a higher priority on some policies that will benefit older people. In some cases, this may lead to sacrificing some policies that will benefit younger people. However, older voters also hold many policy preferences that are similar to those of younger people. Moreover, older people do not tend to vote as a bloc or to mobilize politically on behalf of win-lose policy issues that benefit them alone. These findings from recent political science research cast doubt on the demand-driven explanation for policymakers’ tendency to enact win-lose rather than win-win policies. Factors affecting the supply side – for example, the structure of politics and policymaking, and the preferences of other actors such as politicians and peak organizations of business and labour – play a much larger role than the demographics of the electorate in determining the policy mix pursued by governments.

3.2 The Demand-Side Explanation for Win-Lose Policies: Partially, but Only Partially, Correct

The ‘greedy geezer’ narrative rests on two assumptions: that older people are likely to prefer win-lose social spending on generous pensions and medical care over the expansion of benefits such as education, child care or preventive health; and that when older people make up a large share of the electorate and have strong organized interests working on their behalf, their policy preferences will tend to dominate those of the young. While much of the received wisdom on the political challenges of ageing populations, particularly connected to the welfare state, begins with these assumptions, empirical scholarship on public opinion and voting behaviour offers only partial support for them.

3.2.1 Older People Do Make Up a Large Share of Voters

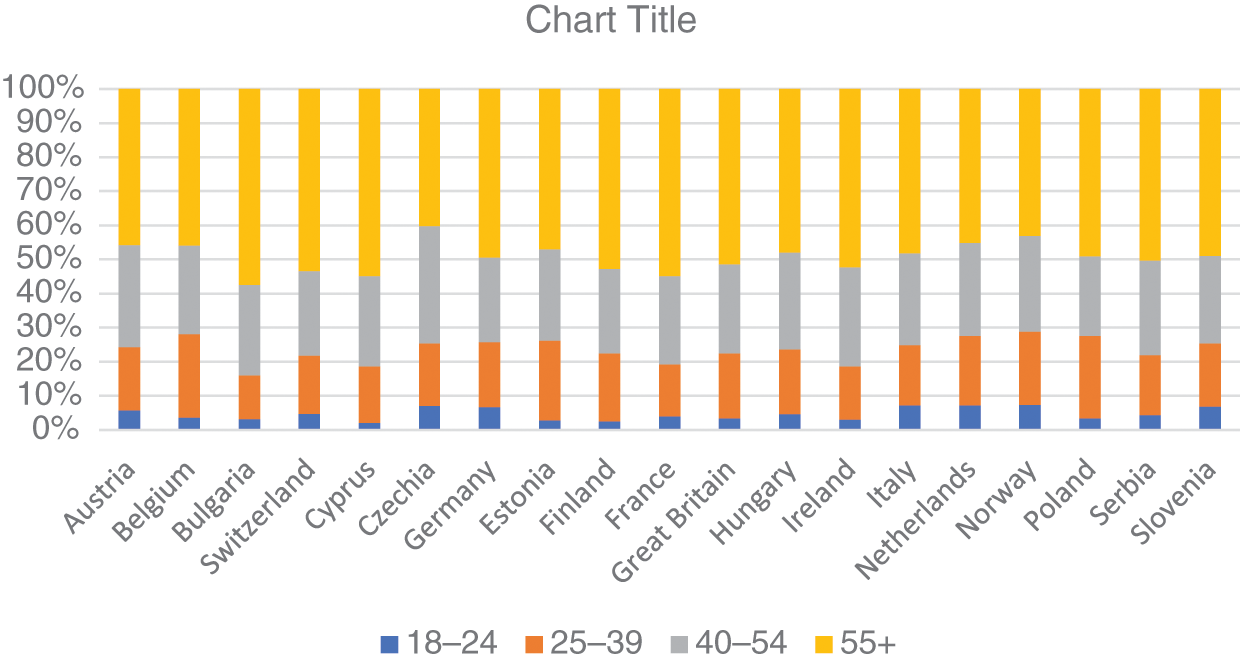

Older people are indeed a growing share of the electorate, both because of their increasing share in the population, and because they have a higher propensity to vote than do younger age groups (Figure 3.1). In most European countries the share of adults who report having voted in the previous election rises with age until around age 70 (Reference Bussolo, Koettl and SinnottBussolo et al., 2015, 265). In some countries a combination of local demographic conditions, voting behaviour and first-past-the-post electoral systems make the older share of the electorate seem particularly relevant. For example, in the 2010 UK general election, half of the constituencies in England, Scotland and Wales had electorates in which voters aged 55 and up constituted a majority (Reference ChaneyChaney, 2013, 458)Footnote 2.

Figure 3.1 Share of the electorate in the last national election by age group, European countries.

The reasons why older people vote at higher rates than younger people may be related strictly to age: by virtue of having spent more of their lives at or above the voting age, older people may be more strongly habituated to voting (Reference GoerresGoerres, 2007). However, high voting rates among older adults may also be a result of period or cohort effects: today’s older people have a stronger normative attachment to voting because of their political socialization in the immediate post-war period (Reference GoerresGoerres, 2007), while post-Baby Boom generations vote at lower rates than earlier cohorts (Reference Bhatti and HansenBhatti & Hansen, 2012, 271). If very high voting rates are unique to people socialized in the immediate post-war period, differences in turnout rates between age groups may well decline in future elections. Such an outcome is predicted for Germany (Reference Konzelmann, Wagner and RattingerKonzelmann et al., 2012, 259), although empirical analysis for many other countries is not available.

3.2.2 Sometimes Older Adults Prefer Win-Lose Policies, and Act Politically to Try to Get Them

If older people are likely to rise as a share of the electorate, at least in the near term, it may be that politicians will be inclined to pay particular attention to their interests. There is a correlation between the share of older people in the population and among voters (Reference Krieger, Chen, Coull, Waterman and BeckfieldKrieger et al., 2013; Reference Sanz and VelázquezSanz & Velázquez, 2007; Reference SheltonShelton, 2008; Reference Tepe and VanhuysseTepe & Vanhuysse, 2010). But one cannot conclude from this that social spending priorities are the outcome of political pressure from older voters. One reason is that to a certain extent, pension spending is mechanically related to population ageing: as long as the average benefit level remains constant or rises, more beneficiaries will mean more aggregate spending. Moreover, if the budget for total social spending is fixed or shrinking, increased pension spending will translate into less spending on other kinds of social benefits, including education and child benefits. Thus, a higher share of spending on older people is very likely to occur in ageing populations even without any political pressure from older voters.

This implies that in order to confirm the ‘greedy geezer’ narrative that policies favouring older people result from demand from an ageing and selfish electorate, we must at the very least show that older voters and lobby groups want and demand something different from younger voters and the organized interests that represent them. What does the best available evidence tell us in this regard? Several studies of age-based social policy preferences in Europe have found that older adults or retired respondents are on average more supportive of increasing pension spending than they are of increasing public education spending (Reference Busemeyer, Goerres and WeschleBusemeyer et al., 2009; Reference Mello, Schotte, Tiongson and WinklerMello et al., 2017; Reference SørensenSørensen, 2013). One study also finds that Swiss people over age 50 are four percentage points more likely than people aged 30–49 to prioritize health spending over education spending (Reference Cattaneo and WolterCattaneo & Wolter, 2009, 234).

Moreover, there is some evidence that on average older people do not only hold different social policy preferences than younger people, but also vote on the basis of those preferences. It can be difficult to tell why voters in different age groups vote for particular parties or candidates, and hence hard to assess whether voters are expressing their policy preferences (rather than for example their preferences on other issues, their long-term partisan affiliations or their general ideological orientations) when they vote. However, a study of voting patterns in Swiss referenda on specific social policy initiatives between 1981 and 2004 found that even after controlling for ideology, ‘Older generations not only massively approve[d] improvements in the benefits they receive, but they also tend[ed] to reject social policy proposals aimed at improving the situation of the actively employed and of young families’ (Reference Bonoli and HäusermannBonoli & Häusermann, 2009, 13). While voting for pensioner parties is rare – pensioner parties have had very little success in most European countries (Reference Hanley and TremmelHanley, 2010, 2013) – support for pensioner parties may also be interpreted as being linked to policy preferences favouring retirees. One study found that Dutch pensioner parties have captured voters who wish to advance their relatively well-protected position in the welfare state (Reference Otjes and KrouwelOtjes & Krouwel, 2018, 41–2).

Beyond voting, the interests of the seniors may be represented outside of the electoral arena by pensioners’ unions and advocacy groups. While few advocacy groups for older people in Europe have the political clout of the Association for the Advancement of Retired Persons (AARP) in the USA, organizations working on behalf of older adults and retirees can have an important role in policy, especially where pensioners’ unions or civil society groups are incorporated into the policy process via neo-corporatist or other consultation processes (see Reference Anderson and LynchAnderson & Lynch, 2007; Reference Campbell and LynchCampbell & Lynch, 2000; Reference ChiariniChiarini, 1999; Reference LambeletLambelet, 2011).

3.2.3 Social Policy Preferences of Older and Younger People Are Often Not As Different As We Expect

While on some issues and in some countries some older voters may prefer different policies than do younger ones, the most recent large-scale survey of social policy preferences reveals a complex relationship between age, retirement and social policy preferences once political ideology and other potential confounds are controlled for. Instead of the predicted cleavage in social policy preferences, Reference Busemeyer, Garritzmann, Neimanns and NeziGarritzmann et al. (2018) find that across eight Western European countries retirees, like younger people, strongly support social investment policies such as early childhood education, job training and higher education spending, while they oppose more generous passive transfers such as pensions, early retirement and unemployment benefits. In this study, the exceptional group preferring more generous passive transfers is people aged 50–59, not retirees. This study echoes the abundant literature on social policy preferences that finds that age, cohort or retirement status per se generally have very little, if any, predictive power above and beyond left-right political ideology, gender, country of residence, etc. (see Reference Busemeyer, Garritzmann, Neimanns and NeziBusemeyer et al., 2018; Reference Busemeyer, Goerres and WeschleBusemeyer et al., 2008; Reference Goerres and TepeGoerres & Tepe, 2010; Reference Kohli and TorpKohli, 2015; Reference Komp, Komp and AartsenKomp, 2013; Reference Krieger, Chen, Coull, Waterman and BeckfieldKrieger et al., 2013; Reference Lynch and MyrskyläLynch & Myrskylä, 2009; Reference Mello, Schotte, Tiongson and WinklerMello et al., 2017; Reference SørensenSørensen, 2013; Reference Walczak, van der Brug and de VriesWalczak et al., 2012).

One reason for the consistent finding of only minor differences in social policy preferences according to age is that ‘older people’ are in reality a diverse group. Older voters differ from the young in terms of their political socialization and their personal ideologies and preferences (on average today’s older adults are somewhat further to the left on most economic and welfare policies than are the young or middle-aged (Reference Caughey, O’Grady and WarshawCaughey et al., 2019; Reference Ferguson and de WeckFerguson & de Weck, 2019)), but they also differ amongst themselves in ways that are likely to affect their policy preferences. Age (young-old versus old-old), class and the specific features of the social, economic and policy context in different countries have all been found to predict important differences in social policy preferences among older voters (Reference Busemeyer, Goerres and WeschleBusemeyer et al., 2008; Reference FairlieFairlie, 1988; Reference Fernández and Jaime-CastilloFernández & Jaime-Castillo, 2013; Reference Goerres, Vanhuysse, Vanhuysse and GoerresGoerres & Vanhuysse, 2012; Reference Komp and van TilburgKomp & van Tilburg, 2010; Reference NaumannNaumann, 2014; Reference Sabbagh and VanhuysseSabbagh & Vanhuysse, 2010; Reference Tosun, Williamson and YakovlevTosun et al., 2012; Reference Vidovičová and HonelováVidovičová & Honelová, 2018). These findings are, of course, consistent with core findings of the broader political science literature that (a) many demographic characteristics are strongly associated with public opinions and political behaviours, and (b) existing institutions and policies have an independent effect on opinions and behaviours.

3.3 Older Voters Do Not Vote As a Bloc

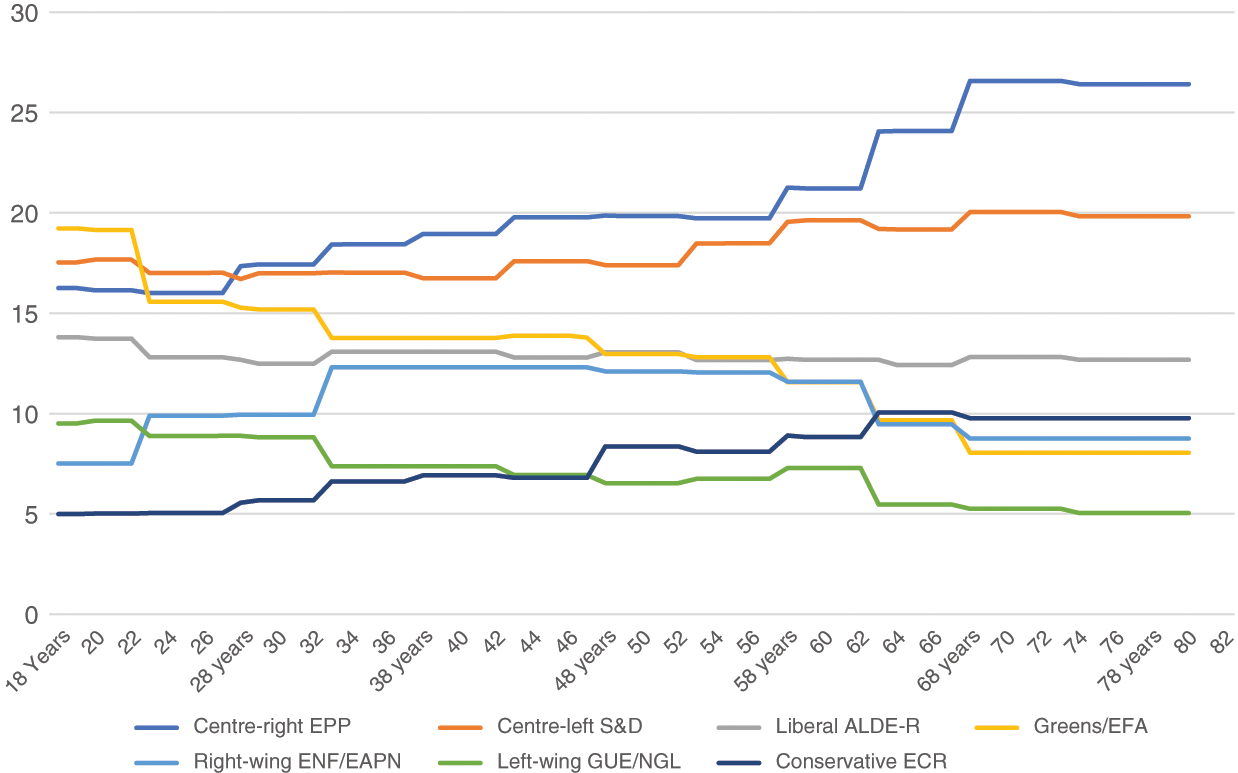

Age is associated with patterns of voting for one party versus another in many European party systems, as well as at the European level. For example, exit polling during the 2019 European Parliament elections showed that as compared to voters under the age of 35, older voters were markedly less likely to vote for a Green Party candidate and more likely to vote for a centre-right (EPP) or conservative (ECR) candidate (see Figure 3.2).

Figure 3.2 Vote shares of party groups by age, 2019 European Parliament elections.

However, belonging to the category of ‘the elderly’ does not generally translate into distinctive voting patterns once one takes into account the sociodemographic factors that are associated with both age and party choice. Analysis of European Social Survey data shows that after controlling for factors such as gender, household income, social class, religiosity, rural residence and ideological orientation, it is possible to predict party choice based on belonging to the 55+ age group for only a small number of cases of parties in Europe – fewer parties, in fact, than would be predicted by chance alone (see the Appendix to this chapter for details of the analysis). The fact that some of the very few parties that do receive disproportionate support from older voters – for example the Conservative Party in the UK – are unusually prominent in the minds of English-speaking analysts likely drives a perception that membership of the ‘elderly’ age group matters more than it actually does for voting.

Even in those cases where differential voting by age group does occur, it is not always clear that the consolidation of support among older voters has an effect on the policy outputs of governments. This is a consequence of the demographic diversity of older people: while they may form a large voting group, they do not necessarily act as a group, and hence may have difficulty translating even those policy preferences that they share into effective political pressure. As Goerres (2008) explains, ‘A political cleavage is a line of conflict along which parties mobilize their constituents, meaning that that conflict becomes politically decisive. There are three stages in the development of a cleavage: (1) social groups can differentiate among each other by a set of social characteristics that are somehow socially constructed and accepted; (2) political parties exist that use these social features to frame their messages; (3) voters of a given social group use their own social definition as a shortcut to vote for the party representing their group, thereby politically reinforcing the division line. If age were a political cleavage, we would need to see at least one party popular among the old and another party popular among the young.’ Yet this differential partisan mobilization by age is unlikely in many contexts both because parties (and unions) have traditionally managed the demands of multiple generations (Reference KohliKohli, 1999), and because older voters are generally among the least likely to switch their institutional affiliations (Reference GoerresGoerres, 2009). As of 2003, even in the USA and the UK, where the age cleavage was relatively strongly represented by advocacy organizations not linked to parties, voters did ‘not tend to vote as an interest group’ (Reference VincentVincent, 2003, 10).

The period since 2010, which has witnessed much greater electoral volatility in Europe, presents an opportunity for a realignment of party systems around an age cleavage, but it is too soon to tell if that has happened. Even if parties were to focus on an age cleavage, which is unlikely, an age cleavage is unlikely to have the permanence of other cleavages such as race, ethnicity or class, for the simple reason that we all age. Parties may try to build coalitions around age for a decade or two, but today’s older voters will not be around for much more than that, and in a decade or two middle-aged voters will be older themselves. Nationality, race and class reproduce across generations; generations obviously cannot.

If mainstream parties have not reorganized around an age cleavage, neither have pensioner parties successfully replaced them as representatives of older voters. Pensioner parties have emerged in several European countries but have gained parliamentary representation in only two (the Netherlands and Luxembourg) and are generally negligible political forces (Reference Bussolo, Koettl and SinnottBussolo et al., 2015; Reference Gilleard and HiggsGilleard & Higgs, 2009; Reference GoerresGoerres, 2008; Reference Hanley and TremmelHanley, 2010). Nor have the older people influenced policy as a bloc through other modes of political participation beyond voting. While nonconventional forms of participation like protesting, demonstrating and petitioning are rising in younger age groups (Reference AlbaceteAlbacete, 2014; Reference TiberjTiberj, 2017), older adults are significantly less active than young or middle-aged people when it comes to non-electoral forms of participation (Reference Goerres and TepeGoerres & Tepe, 2010; Reference Melo and StockemerMelo & Stockemer, 2014, 45–6). Senior advocacy groups can be effective mouthpieces for the interests of older people as a bloc, but even when large these groups are not always effective (Reference GoerresGoerres [2008] notes that the VDK Deutschland, an older persons’ interest organization with 1.4 million members, has had little influence on policy). And Reference Campbell and LynchCampbell and Lynch (2000) find that very large, powerful interest groups like the AARP and Italian pensioners’ unions have professionalized staffs that are often motivated to moderate the demands of pensioners in order to ensure the long-term sustainability of the welfare state, blunting the potential impact of ‘greedy geezers’ on policy demands.

If older people hold policy preferences that are often indistinguishable from those of younger voters, if they have not aligned themselves with mainstream parties in order to function as a voting bloc, and if their organized representatives are either impotent or disinclined to pursue a win-lose policy strategy of increasing benefits for seniors at the expense of social investment, then it should not come as a surprise that ‘the elderly are not successful in setting a political agenda. They do not influence the party manifestos, the electoral debate […]. Compared to groups who are much smaller, for example the farmers, gun owners, or policemen, they are relatively ineffective. And even taking into account their difficulties of physical mobility and resources, older people do not mobilise militant support in the manner of road protesters, animal rights, or disabled activists. While pensioners organisations are able to hold mass meetings, marches and lobbies they do not attract the attention or the political clout that the numbers of older people in the community suggest they might’ (Reference VincentVincent, 2003, 10).

3.4 The Supply-Side Explanation for Win-Lose Policies Is Also Partly, but Only Partly, Right

The logic of the ‘greedy geezers’ narrative, in addition to resting on a partially incorrect assumption that older people hold social policy preferences that are distinct from the young and vote in a bloc to express those preferences, requires that politicians supply the policies that they do in response to pressure from older voters or interest groups. In this essentially pluralist and representational logic, policymakers respond to external pressures from competing groups in the electorate, and only to those external pressures. Decades of political science research on the welfare state and policymaking have shown that this model, while compelling as a heuristic, does not capture the full range of influences on policy outputs, many of which come from the supply side rather than the demand side of politics. This section first examines evidence for the responsiveness of politicians to pressure from groups of older people in the electorate, and then explores other influences that might affect the supply of win-win vs. win-lose social policies.

3.4.1 There Is Some Evidence of Politicians Responding to Demands from Older Voters When Making Social Policy Choices

If older people make up a large group in the electorate, are not locked in to voting for a particular party and have distinctive policy preferences, then we can expect politicians to supply policies that appeal to this group in an effort to court their votes. The UK offers an example of this dynamic: Chaney’s analysis of election manifestos in the UK during the post-war period revealed an increase in the salience and detail of policies directed at older adults. But it is not clear how widespread this pattern is across European democracies (Reference ChaneyChaney, 2013). It is possible that the first-past-the-post electoral system and a high concentration of older voters in particular districts in recent decades make the UK an unusual case, and there have been few empirical studies of the responsiveness of parties or politicians to seniors.

One area in which parties and politicians are often presumed to be quite sensitive to the preferences of older voters is in the area of pension reform, and narrative accounts of pension reform often include references to a ‘backlash from pensioners’ (Reference WisensaleWisensale, 2013, 25), governments fearing to ‘ace their electorates’ (Reference CaseyCasey, 2012, 260), or unspecified ‘electoral pressures’ (Reference Weaver, Torp and TorpWeaver & Torp, 2015, 76). Indeed, Pierson’s ‘new politics’ theory (Reference PiersonPierson, 1994, Reference Pierson1996) predicts that the politics of contemporary social policy will be marked by a distinct age dimension. According to Pierson, politicians seek to claim credit for expanding social benefits, and to avoid blame for withdrawing them. In the context of mature welfare states, the limited scope for expansion is mainly to cover previously excluded groups and ‘new social risks’ (Reference Armingeon and BonoliArmingeon & Bonoli, 2007) that have emerged with the breakdown of lifetime employment and the male-breadwinner family model – most of which could be categorized as win-win policy, and much of which is aimed at children and working-age people. Meanwhile, the targets of contraction in mature welfare states are likely to be the beneficiaries of large, well-established, expensive social programmes whose costs are driven even higher by population ageing: pensions and medical care. The ‘new politics’ of the welfare state, then, can be expected to have an age dimension: when politicians seek to claim credit for expanding social benefits, it should be with younger voters, and their primary relationship with older voters should be one of blame avoidance.

However, more recent empirical literature on blame avoidance generally finds limited support for the most simplistic formulations of the theory that posit a direct relationship between policy proposals and perceived electoral pressure. Indeed, in their comprehensive study of pension politics in Western European countries, Reference Immergut, Anderson, Immergut, Anderson and SchulzeImmergut and Anderson (2009) find only rare instances – for example in the Netherlands – where the electoral system, the distribution of the electorate and the structure of the pension system combine to make politicians keenly sensitive to electoral pressures from the older voters.

3.4.2 Policy Is Mainly a Response to Factors Other Than Pressure from Older People

In far more country cases, Reference Immergut, Anderson, Immergut, Anderson and SchulzeImmergut and Anderson (2009) found, politicians were motivated in their pension reform attempts by their ideological beliefs about social programmes (Reference Schumacher, Vis and van KersbergenSchumacher et al., 2013, 17); by their perception of the need for immediate system change; by the demands of unions, whose social policy preferences were more or less friendly to current retirees depending on their role in managing the pension system and/or on their organizational structure; by pressure from specific groups of current or retired workers, such as farmers or public sector employees, who enjoyed special pension privileges; by influence from international organizations like the OECD, World Bank, IMF or European monetary regulators; and by powerful financial market actors with a stake in pension system organization (see also Reference NaczykNaczyk, 2013). In other words, pension policy resulted from a complex mix of politicians seeking to avoid blame or claim credit from numerous constituencies.

Another reason why older voters do not drive an agenda tailored to ‘greedy geezers’ is that in most polities, policy is only partially a product of electoral demands. The institutional landscape presented by electoral and governance systems also has an important impact on social policymaking. The Swiss system, with its frequent recourse to policymaking by referendum, is very likely an outlier. But even there a recent study found that on average the policy preferences of parliamentarians were closest to those of the young and furthest from those of older voters (Reference Kissau, Lutz and RossetKissau et al., 2012, 74–5). And ministries and their staffs are generally even further removed than are parliaments from the pressures of the electorate. In countries where inclusion of the social partners and/or civil society groups in policymaking is customary, the preferences of atomized voters may have even less of an impact on legislation.

Where electoral politics does matter for social policymaking, it is very often not in the form of a simple equilibrium balancing demand from voters with supply of policy solutions by politicians. Instead, just as in health care, the providers (in this case politicians) often over-supply particular goods in response to other incentives. Reference LynchLynch (2006) showed that the dominant mode of political competition (particularistic or programmatic) in a country, rather than electoral pressure from senior or youth organizations, determined politicians’ choices about how to structure social policies, and that these choices in turn resulted in different age-orientations of social spending in OECD countries as populations aged. Similarly, Reference Immergut, Anderson, Immergut, Anderson and SchulzeImmergut and Anderson (2009) found that expansion or contraction of pension entitlements in Western European countries depends in part on the intensity of political competition, which is determined by a combination of the electoral system, the party system and whether the geographic distribution of preferences in the electorate aligns with districts in a way that provokes politician responsiveness.

The contemporary politics of social policy is also determined to a very large extent by actual or perceived fiscal constraints. A combination of pressures from population, low employment and the Maastricht Treaty (which formalized debt and deficit criteria for entry into the EMU in 1992) prompted strong efforts at budgetary control in many continental European governments, which affected social policy programmes as well as other areas of public spending. In some instances, as in Italy, the Netherlands, Germany, and France, this contributed in the 1990s and 2000s to tipping the balance of social spending somewhat away from passive social policies benefiting primarily older workers and future retirees, and towards a greater emphasis on benefits for the young, such as cash transfers for lone parents, early childhood education and job training for unemployed youth. Pressures for budgetary restraint also encouraged some governments in the higher-spending continental social-insurance-based systems to seek cost savings in health care. These efforts affected health care users by increasing out-of-pocket payments (often exempting older people and those with low incomes, however) and, in some instances, diverting health sector resources to less costly preventive services and health promotion. On balance, fiscal pressures, at least in continental Europe and prior to the crisis, may have stimulated a politics of turning ‘vice into virtue’ (Reference LevyLevy, 1999) that resulted in a recalibration of social policy systems to include more win-win policies. Budgetary politics since the global financial and Eurozone crises, however, have resulted (especially in Southern Europe) in more indiscriminate cuts to social services and health systems that are likely to have a more negative impact on younger people.

3.5 Weighing the Evidence

3.5.1 Are Older People ‘Greedy’, Rationally Demanding, or Deserving?

On some issues, and in some contexts, older adults do mobilize politically in defence of their interests as older people and in order to protect their assets or income. But there is considerable variation across both issues and contexts. In terms of contexts, it seems to be in the UK and the USA that the most pronounced generational or age cleavage appears in support for a range of issues from school funding to housing policy to pensions (see e.g. Reference Lynch and MyrskyläLynch & Myrskylä, 2009 on pension income as a determinant of preferences in the UK as compared to other European countries). This may be related to the fact that these liberal welfare states provide fewer protections for their citizens overall. A scarcity of social resources may lead older people to be more assertive in protecting the transfer payments on which they rely and the assets that they have accumulated and that may be an important source of financial security for them and their children.

Some issue areas may also be more apt than others to generate age-based differences of opinion and political mobilization. I have examined age-based attitudes mainly in the arena of income transfers and social services, and in these domains older people have often been protected from immediate cutbacks by ‘grandfather’ clauses or age-based exemptions from user fees, even as younger people also continue to enjoy access to benefits. It is perhaps not surprising, then, that there is broad societal consensus on the desirability of continued state provision of many forms of transfers and services. However, when asset-based welfare supplants direct provision of social benefits, older people may develop sharper interests in taxing, zoning, financial regulation and other policies that protect accumulated wealth. To the extent that older people have lived through periods where there were opportunities for asset accumulation while younger people have not, their preferences may on average diverge. Even so, under these circumstances some younger adults may have a shared interest in policies that protect the assets of their parents, which they may expect to inherit.

The interests that older people have in policies that protect their incomes and/or assets may be rationally demanding, rather than unreasonable or greedy, to the extent that they are needed to ensure their wellbeing in the context of broader social policy arrangements. Indeed, such policy preferences may be supported by society at large if they are perceived as necessary for ensuring an equitable distribution of resources to a group that might otherwise be poor. Policies favouring older adults may also be supported by social narratives that cast older people as especially ‘deserving’ because of their past contributions to overall economic development and/or social insurance programmes, or because of their status as respected elders. These social narratives might even help to explain how governments could produce a win-lose policy mix: if working-aged adults (and their children) are seen as especially undeserving of social support relative to older people, investments in early stages of the life-course may be crowded out by policies that benefit mainly current seniors.

3.5.2 Social Policies Generally Result Mainly from Considerations Unrelated to Demand from Voters

While it is tempting to assume that in representative democracies demand from (different groups in) the electorate explains whether politicians and policymakers provide win-win versus win-lose policy mixes, the supply of policies is in fact very often due to other factors. Decades of research into patterns of social policy provision have highlighted several factors as particularly relevant to the supply of win-win policy.

Policy drift results when politicians and policymakers fail to update policies to keep up with larger social, demographic or economic changes that affect the outputs of policies (Reference HackerHacker, 2004). Reference LynchLynch (2001, Reference Lynch2006) found that the age-orientation of social spending in OECD countries is due not to politicians responding in real time to demands from the electorate, but rather to politicians’ differential propensity to update social welfare systems to compensate for demographic trends in political systems characterized by different types of political competition.

Provider groups can also be an important source of political pressure for social policies whose interests may either diverge from or amplify the voices of the consumers of social policy. For example, Reference GiaimoGiaimo (2002) highlights the role of doctors and Reference PereraPerera (2018, Reference Perera2019) the role of public sector social service providers in demanding expanded service provision; and Reference NaczykNaczyk (2013) and Reference AndersonAnderson (2019) show how the financialization of pension systems in recent years has led to a growing influence of financial market actors on pension policymaking.

A commitment to evidence-based policymaking can provide a pathway for scientific research to influence policy, especially when there is a strong consensus in the research community about the costs and benefits of certain policy approaches. As we outline in Chapter 2, there is abundant evidence of the benefits of win-win policies for population health, equity and financial sustainability. However, institutional, professional and political barriers can stand in the way of evidence being taken up in policy, and may help to explain variation in the passage or implementation of policies that are widely believed to be promising (Reference SmithSmith, 2007, Reference Smith2013).

Pressure from international actors – from bond traders to the European Commission to the World Health Organization – can also affect the behaviour of domestic policymakers. Financial market actors and European regulators may exert pressure to constrain the growth of public spending (Reference MosleyMosley, 2000) and/or open up markets for financial and other services to international competition (Reference Greer, Fahy, Rozenblum, Jarman, Palm, Elliott and WismarGreer et al., 2019; Reference KoivusaloKoivusalo, 2014). The EU, WHO and other international organizations may also play a role in stimulating policy development through soft law mechanisms such as the open method of coordination (Reference Barcevicius and WeishauptBarcevicius & Weishaupt, 2014) or policy initiatives like Health For All (Reference LynchLynch, 2020).

Finally, in the current political and economic environment, fiscal constraints may be the most important determinant of social policy development. Whether acting through bond market yields, imposed from above during European Semester negotiations, and/or undertaken voluntarily by domestic party-political actors, the rhetoric and practice of austerity shape the possibilities open for policymakers to pursue investments in human capital across the life-course.

3.6 Conclusion

This chapter has shown that the narrative of the ‘greedy geezer’ or ‘selfish generation’ imposing their political will and preventing investments in win-win social policies is largely a figment of our collective imagination. There are circumstances in which older voters may act ‘selfishly’ on behalf of their children, for example by seeking to protect their investments in housing that they plan to pass down to future generations, and too rigidly restricting redistribution to within families, rather than across them to support the neediest, is deleterious not only for health but for social justice. Even so, there is considerable space for demands from older voters that would be socially desirable. Not only the most deprived elderly (who cannot rightly be called ‘greedy’ if they ask for more than they are getting), but all those who stand to benefit from policies that promote healthy and active ageing should be encouraged to advocate for these policies that benefit the whole of society.

3.7 Appendix

For the analysis of the distinctiveness of elderly support for particular parties we estimated a series of binomial logit models for each European party, country and year (wave) in the most recent two full waves of the ESS dataset (corresponding to 2014 and 2016). The quantity of interest was the binomial regression coefficient on the age group 55+, which represents the increment in support for a party among that age group as compared to the reference group of people aged 25–39. We selected age 25–39 as the reference category to allow for maximum potential contrast, since those aged 40–54 have been found to have ageing-related policy preferences more similar to those of the ‘elderly’ (aged 55+). We limited the sample of parties to those receiving at least 5 per cent of the national vote in the election immediately preceding the relevant wave of the survey. We excluded countries in which more than 30 per cent of respondents in any age group (25–39, 40–54, 55+) was missing data on household income, as well as all respondents below the age of 25 (due to a high degree of missingness on income in that age group). Remaining missing data for household income and other variables were multiplied using multivariate imputation by chained equations (mice routine in R) and predictive mean matching method based on all other variables included in the models. Among all respondents from a given country and wave, we predicted the propensity to vote for each party in the system based first on age group alone, and then additionally controlling for age in years, gender, primary education, tertiary education, household income (in deciles of the national income distribution), household income mainly from pensions (including disability, old-age and widow/ers’ pensions), religiosity, current or former union membership, living in a rural area, belonging to a group that is discriminated against in the respondent’s country, and self-placement on the left-right ideological spectrum. We ran a total of 445 (221 for 2014 and 224 for 2016) fully controlled models on thirty-eight countries (nineteen for each wave), and found a total of sixteen parties (four for 2014 and twelve for 2016) for which belonging to the 55+ age group was a significant positive predictor of voting in the previous national election at the standard .05 per cent confidence level. No party had a significant effect of belonging to the 55+ age group in both 2014 and 2016. The magnitude and significance of the coefficient on the 55+ age group in each party model is reported in Table A1.