I. Introduction

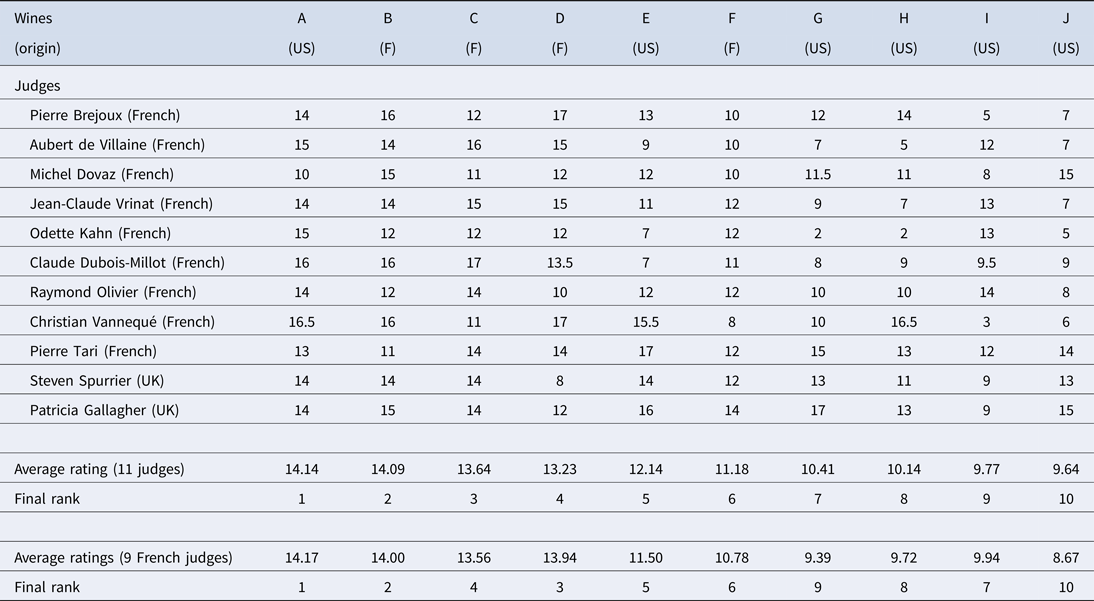

On May 24, 1976, Steven Spurrier, a British wine merchant, and his colleague Patricia Gallagher of the Académie du Vin, organized a blind tasting of ten red wines in Paris.Footnote 1 They gathered nine French judges,Footnote 2 who were acknowledged experts, to taste the ten wines: four Bordeaux and six Californian Cabernet Sauvignons. Wines were graded on a scale between 0 and 20, and the grades were simply added to compute the final ranking. Table 1 reports the data. As can be seen, the winner was the 1973 Stag's Leap Wine Cellars S.L.V. Cabernet Sauvignon (Stag's Leap Cabernet Sauvignon in what follows), a Californian wine from Napa Valley, while celebrated Bordeaux—Château Mouton-Rothschild, 1970, Château Haut-Brion, 1970, Château Montrose, 1970, and Château Léoville Las Cases, 1971—trailed after Stag's Leap Cabernet Sauvignon (positions 2, 3, 4, and 6).

Table 1. The Paris 1976 wine tasting: Judges and ratings

Notes: Each column gathers the ratings from the nine official (French) judges, and the two non-official judges for the ten red wines. The last rows provide the aggregate ratings and the corresponding ranking that resulted from them when taking all 11 judges or only the 9 official (French) judges. The wines are: A: Stag's Leap Cabernet Sauvignon, 1973, B: Château Mouton-Rothschild, 1970, C: Château Montrose, 1970, D: Château Haut-Brion, 1970, E: Ridge Vineyards Monte Bello Cabernet Sauvignon, 1971, F: Château Léoville Las Cases, 1971, G: Heitz Wine Cellars Martha's Vineyard Cabernet Sauvignon, 1970, H: Clos du Val Cabernet Sauvignon, 1972, I: Mayacamas Vineyards Cabernet Sauvignon, 1971, J: Freemark Abbey Winery Cabernet Sauvignon, 1969.

It is often said that the Judgment of Paris gave worldwide visibility to American wines. George Taber, a journalist working for Time magazine, published a book on the event (Taber, Reference Taber2005). In a segment for National Public Radio News he is quoted saying that the Judgment of Paris “turned out to be the most important event, because it broke the myth that only in France could you make great wine. It opened the door for this phenomenon today of the globalization of wine.” Maria Godoy (Reference Godoy2016), the senior science and health editor and correspondent for National Public Radio News in charge of that segment, punned that this was “the blind taste test that decanted the wine world.”

The outcome of the Paris tasting was, nevertheless, controversial. Ashenfelter and Quandt (Reference Ashenfelter and Quandt1999) stated that tasters should have ranked the wines instead of rating them, to guarantee that each judge had the same influence on the outcome. This slightly changed the rankings, but Stag's Leap Cabernet Sauvignon remained first. Hulkower (Reference Hulkower2009) noted that Château Haut-Brion would have been first if the votes had been aggregated via the so-called Borda rule.Footnote 3 Ginsburgh and Zang (Reference Ginsburgh and Zang2012) and Gergaud, Ginsburgh, and Moreno-Ternero (Reference Ginsburgh2021) studied other voting protocols, which also changed the outcomes of the Judgment.

In this short paper, we follow another path and check whether the number one position of Stag's Leap Cabernet Sauvignon (as well as the position of the other nine wines) has remained stable over time. As we shall see, we find that Stag's Leap Cabernet Sauvignon is far from being first in most subsequent years. This may be due to one of the two following possibilities: (a) judges overrated the wine in 1976; or (b) Stag's Leap Cabernet Sauvignon was an outlier in 1973.

A. Analysis

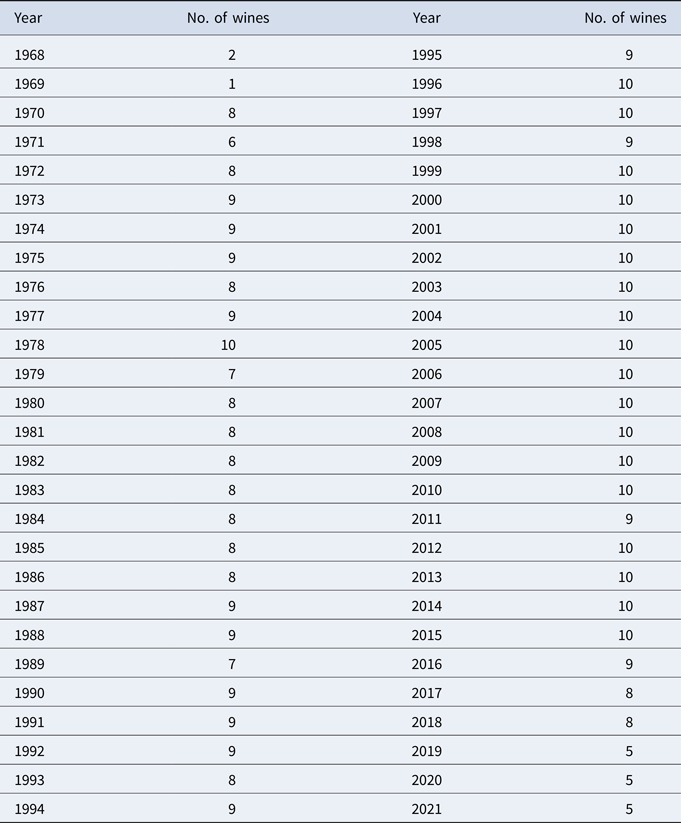

To track the quality assessments of these ten wines over time, we collected the ratings of experts (such as Wine Spectator, Wine Enthusiast, Wine Advocate, Revue du Vin de France, Jancis Robinson, James Suckling, and others) between 1968 and 2021.Footnote 4 Table 2a shows how many wines and their ratings could be retrieved between 1968 and 2021. Table 2b shows the frequencies of available ratings for the ten wines. In 19 cases (years), it was possible to collect the ratings of all ten wines; in 14 cases, this was possible for nine wines, etc. As will be seen, we also need the average rating of wines produced in the five regions in which the ten wines are grown: California, Pauillac, Pessac-Léognan, Saint-Estèphe, and Saint-Julien.Footnote 5

Table 2a. Number of available ratings per vintage

Notes: Table 2a shows how many wines and their ratings could be retrieved between 1968 and 2021 from Wine Searcher.

Table 2b. Frequencies of available ratings

Notes: Table 2b shows the frequencies of available ratings. In 19 cases (years), it was possible to get ratings for all 10 wines; in 14 cases, this was only possible for 9 wines, etc.

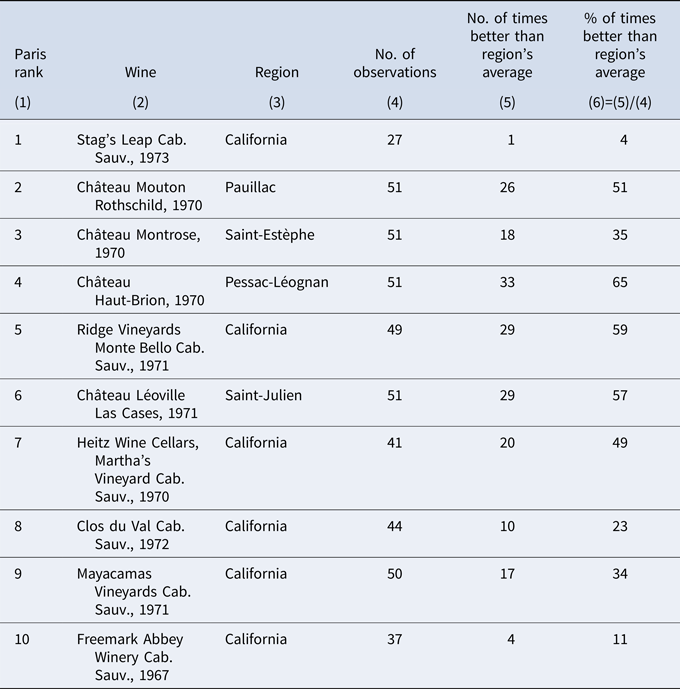

Table 3 provides some analytics for the ten wines. Column (4) shows the number of times each of them was observed (or rated); Column (5) contains the number of times the rating of each individual wine was higher than the rating of the wine's region (again, California, Pauillac, Pessac-Léognan, Saint-Estèphe, and Saint-Julien). As can be seen, Stag's Leap Cabernet Sauvignon did better than the average rate of all Californian wines only once in the 27 years for which there was information, while, as shown in Column (6), Château Mouton-Rothschild, Château Haut-Brion, Ridge Vineyards Monte Bello Cabernet Sauvignon, and Château Léoville Las Cases did better than the average rate of the region more than half the time. The Californian wine Heitz Wine Cellars Martha's Vineyard Cabernet Sauvignon is close with 49 percent. The fact that Stag's Leap Cabernet Sauvignon has moved below their peers might not be a sign of deteriorating wines but may also reflect that Napa, as a new wine region, has seen a surge of outstanding wineries.

Table 3. Number of available ratings per wine and success of wines

Notes: The first three columns list the 1976 Paris rankings (1), names (2), and regions (3) of each wine. Column (4) the number of times each of them was observed in our data; Column (5) lists the number of times the rating of each individual wine was higher than the rating of the wine's region. Column (6) lists the corresponding ratios from the entries in Column (5) and Column (4).

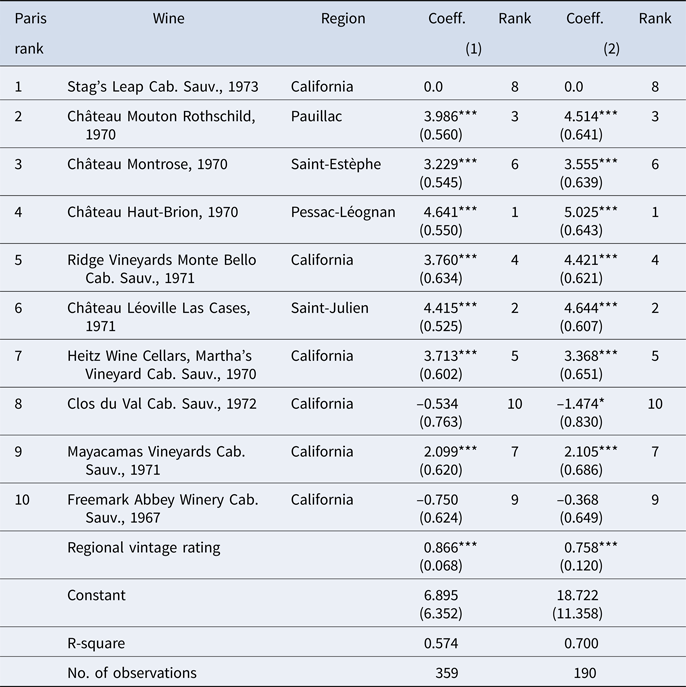

Table 4 displays the results of two regressions. We restrict the sample size to vintages after 1976 (the year of the Judgment) and before 2017 to ensure that each rating is based on a reasonable set of expert ratings.Footnote 6 One regression is based on 359 observations for which the score of the wine and the average score of the region are available. The other one is based on 190 observations that are complete (ten wines times 19 years). The reference category is Stag's Leap Cabernet Sauvignon. The two regressions can be written as:

where R ijt is the rating of wine i in region j and year t, winei is a dummy equal to 1 for this wine and 0 otherwise, xjt is the average wine score in region j and year t, which is assumed to account for weather (and other) conditions in region j and year t; α i, β, and γ are parameters. Estimates α i account for the differences between xjt and R ijt. They can be interpreted as being the number of points that deviates from the regional vintage rating of the region. Château-Mouton-Rothschild, for example, has 3.986 points more than the average rating of the whole Pauillac region. Note also that in both cases (359 or 190 data points), the rankings are identical.

Table 4. Paris ranking and later rankings

Notes: Robust standard errors in parentheses; *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.01. The first three columns list the 1976 Paris rankings (1), names (2), and regions (3) of each wine. The next two columns list the coefficients, and the corresponding rank, for the regression based on 359 observations for which the rating of the wine and the average rating of the region are available. The last two columns list the coefficients, and the corresponding rank, for the regression based on the 190 observations that are complete (from the 19 years in which the 10 wines were rated).

The winners are Château Haut-Brion, Château Léoville Las Cases, Château Mouton-Rothschild, and Ridge Vineyards Monte Bello Cabernet Sauvignon, while Stag's Leap Cabernet Sauvignon, Clos du Val Cabernet Sauvignon, Mayacamas Vineyards Cabernet Sauvignon, and Freemark Abbey Winery Cabernet Sauvignon are ranked at the bottom.

The results shown in Tables 3 and 4 are very similar. In both regressions, seven parameters are significantly different from 0 at the 1 percent level. The standard errors show that there is little, if any, difference in quality between the French wines and two Californian wines (Ridge Vineyards Monte Bello Cabernet Sauvignon and Heitz Wine Cellars Martha's Vineyard Cabernet Sauvignon). Stag's Leap Cabernet Sauvignon is ranked number 8; the parameters αi are not significantly different from those of Freemark Abbey Winery Cabernet Sauvignon or Clos du Val Cabernet Sauvignon.

II. Concluding comments

Our analysis shows that, based on ratings given by a large number of experts over 40 years after the Judgment, Stag's Leap Cabernet Sauvignon was never competitive enough to beat French wines and some other Californian wines such as Ridge Vineyards Monte Bello Cabernet Sauvignon and Heitz Wine Cellars Martha's Vineyard Cabernet Sauvignon. We stress that our results, based on a large set of data and ratings, are arguably more solid than those from the (one-shot) Judgment of Paris in the year 1976.

This leads us to conclude that either the 1973 Stag's Leap Cabernet Sauvignon was overrated by the experts who tasted it in 1976, or that the 1973 vintage was an outlier in this winery.

Note that (a) if judge Christian Vannequé had given 15 instead of 16.5 points to Stag's Leap Cabernet Sauvignon in the Paris tasting, its average rating (when considering the 9 French judges only) would have dropped to the average rating that Château Mouton-Rothschild obtained; and (b) in our world, there are as many first prizes as there are competitions, but the success that winners enjoy is often short-lasting. This is so for books, movies, or musical contests. See, among others, English (Reference English2005) and Ginsburgh (Reference Gergaud, Ginsburgh and Moreno-Ternero2003).

However, Stag's Leap Cabernet Sauvignon is “still going strong.” In 2022, a 1973 bottle was sold for $12,300, the highest price for the vintage, and three times the previous largest price (La Gazette Drouot, Reference Drouot2022).

Acknowledgments

We thank Karl Storchmann (editor of this Journal) and an anonymous referee for helpful comments and suggestions.