In December 2019, several cases of pneumonia appeared in the city of Wuhan, China. Analysis of the genetic material isolated from the virus showed a new β coronavirus, the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The disease is called coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and quickly spread across Chinese territory and the whole world. On 30 January 2020, the WHO declared the disease as a global public health emergency and, on 11 March 2020, as a pandemic with serious health, economic and social impacts(Reference Binns, Low and Kyung1,Reference Zhou, Chen and Chen2) .

In Brazil, the first case of the COVID-19 was confirmed on 29 February 2020. Measures of social distancing are being applied in the country to control the spread of the virus, which involve closing food commercial establishments and controlling access to food retail(3,Reference Oliveira, Abranches and Lana4) .

Consequently, many of the food commercial establishments migrated to take-out and delivery services(Reference Oliveira, Abranches and Lana4–Reference Petetin6) and the use of online food delivery platforms increased in Brazil: during the lockdown, the use of these applications (apps) grew up by 9 % on weekdays and 10 % on weekends(7). However, food services migration to the digital environment and the greater use of these apps by consumers can negatively impact on population’s health since studies prior to the pandemic have characterised the digital food environment as obesogenic by high offer of unhealthy foods(Reference Horta, Souza and Rocha8,Reference Poelman, Thornton and Zenk9) .

Online food delivery platforms also use intensive marketing strategies(Reference Horta, Souza and Rocha8,Reference Granheim, Opheim and Terragni10) , such as photos, discounts, free delivery and combos (a combination of food items and or drinks offered at a discount), mostly directed at unhealthy meals(Reference Horta, Souza and Rocha8). These strategies, especially those that confer some financial benefit to the consumer, can play a prominent role during the COVID-19 pandemic, due to the greater socio-economic vulnerability of the consumer(Reference Abrams and Szefler11,Reference Nicola, Alsafi and Sohrabi12) . In Brazil, during the social distancing period, the pandemic costs are estimated at R$ 20 billion per week(13).

Digital food environment covers social media and the digital marketing(Reference Granheim, Opheim and Terragni10) and changes in this environment can impact on the population health. Thus, understanding the implications of the COVID-19 pandemic under the digital food environment in Brazil can direct policies and actions that promote healthy eating practices during and after this health crisis(Reference Bakallis, Valdramidis and Argyropoulos14).

The present study aims to describe the advertisements published in an online food delivery platform in the twenty-seven Brazilian capitals, during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methodology

This is an analytic study that investigated food advertising in an online food delivery platform in the twenty-seven Brazilian capitals between the 13th and 14th weeks of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The platform under study was created in Brazil in 2011 and is currently the biggest food tech company in Latin America, being present in Brazil, Mexico and Colombia. In Brazil, at the time of the present study, this platform was the only that served all the Brazilian capitals. In 2019, the platform delivered an average of 13 million orders per month and this number reached 39 million during March 2020, when more than 1·5 million downloads of the app were registered. Inside this platform, consumers can access the menus of the registered restaurants and order ready-to-eat meals. Their orders are forwarded to these food outlets and once ready, meals are delivered to customers by couriers working. Payment method includes meal vouchers or debit/credit cards. Food advertising can be shown on the home page of the app aiming to access all consumers that use the app or inside restaurant menus aiming to access the specific public that is interested in a restaurant.

In our study, all the advertisements (n 7005) available on the home page of the app were recorded. We did not include the advertisements made available only inside a restaurant menu.

Data collection was carried out on two non-consecutive days, 1 d of the week and 1 d of the weekend and comprised lunch (11.00–13.00 hours) and dinner time (18.00–21.00 hours). These meals were chosen because they represent, in addition with breakfast (03.00–10.00 hours), the main meals in terms of daily total energy intake contribution in Brazil(Reference Gombi-Vaca, Sichieri and Verly15).

A sample of 25 % of the advertisements (n 1754) was selected by a randomisation process stratified by the day of the week, the mealtime and the city. Therefore, the selected sample represents the universe of food advertising inside the food delivery app home page according to the Brazilian’s capitals, day of the week and mealtime.

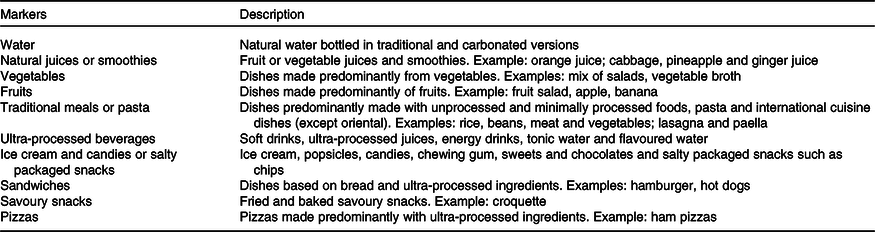

Foods announced in advertisements were classified into the following food groups: water; natural juices and smoothies; vegetables; fruits; traditional meals (dishes predominantly made with unprocessed and minimally processed foods very typical in Brazil) and pasta; ultra-processed beverages; ice cream and candies and salty packaged snacks; sandwiches; savoury snacks; pizzas (Table 1). These food groups were defined based on a previous research that characterised food availability and advertising inside online food delivery platforms in Brazil(Reference Horta, Souza and Rocha8) and are aligned to the NOVA food classification system(Reference Monteiro, Levy and Claro16,Reference Monteiro, Cannon and Levy17) and the Brazilian Dietary Guidelines(18).

Table 1. Description of eating markers

The marketing strategies investigated in each advertisement were free delivery, discounts, use of photos, combos (a combination of food items and or drinks offered at a discount) and messages of healthiness, economy and tasty and pleasure.

Double coding of all advertisements was run in an Excel spreadsheet by two independent assessments with eight researchers completing this work. The coding was checked for agreement, and all divergences were solved by a researcher not involved in data collection.

Data analysis was performed using Stata software (version 14.0). Advertisements were rated for the presence of food groups and marketing strategies participation and were described on the weekdays (Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday and Friday) and on the weekend (Saturday and Sunday) as well as at lunch and dinner and according to the regions of the country (North/Northeast/Midwest and South/Southeast). The differences were tested by applying Pearson’s χ 2 test at a 5 % significance level (P < 0·05). This test was also performed to compare the participation of marketing strategies in the presence of food groups advertising.

Results

Advertisements were published equally between the days of the week (weekday: 51·4 %; weekend: 48·6 %) and were concentrated on dinner (58·3 %; 41·7 % at lunch).

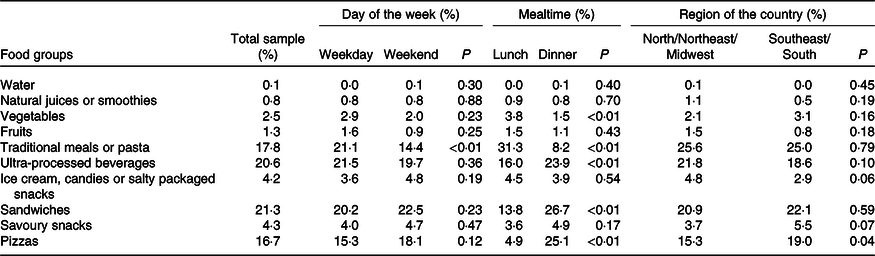

Sandwiches, ultra-processed beverages, traditional meals or pasta and pizzas were the most common food groups shown in the advertisements. The other food groups were present in less than 5 % of the sample. Vegetables and traditional meals or pasta were more advertised at lunch (P < 0·01). The latter were also more exhibited on the weekday advertising (P < 0·01). In contrast, ultra-processed beverages, sandwiches and pizzas were more advertised at dinner (P < 0·01). Pizzas were also more frequent in advertisements for the Southeast and South regions (P = 0·04) (Table 2).

Table 2. Participation of food groups on advertisements in an online food delivery platform in accordance with the day of the week, mealtime, and region of the country

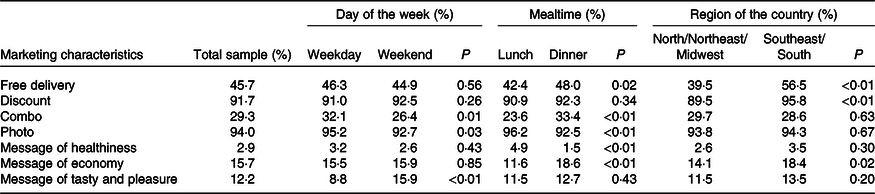

Almost all advertisements used photos or discounts and about half of the sample used free delivery. Combos (P = 0·01) and photos (P = 0·03) were more common on the weekdays advertising, while tasty and pleasure messages prevailed at the weekend (P < 0·01). Free delivery (P = 0·02), combo (P < 0·01) and messages of economy (P < 0·01) were more common on advertisements spread at dinner, while the use of photos and healthiness messages were more frequent at lunch advertising (P < 0·01). In addition, free delivery (P < 0·01), discount (P < 0·01) and economy messages (P = 0·02) were more frequent in the Southeast/South advertising (Table 3).

Table 3. Participation of marketing strategies on advertisements in an online food delivery platform in accordance with the day of the week, mealtime and region of the country

Finally, free delivery prevailed in advertisements of ice cream, candies or salty packages snacks and pizza (P < 0·01) and was less common among advertisements about sandwiches (P = 0·02). Combos were more frequently shown in the advertising of natural juices or smoothies, ultra-processed beverages, sandwiches and pizzas (P < 0·01). However, combos were less commonly used when the advertisement was about traditional meals or pasta (P < 0·01). Photos were more commonly used in ice cream, candies or salty packages snacks (P = 0·03) advertisements, while this strategy was less common in ultra-processed beverages advertisements (P = 0·04). Messages about healthiness were more seen among natural juices or smoothies, vegetables and traditional meals and pasta advertisements (P < 0·01). In contrast, these messages were rarer in sandwiches (P = 0·02) and pizza advertisements (P < 0·01). Economy messages were less seen in advertisements of traditional meals or pasta (P < 0·01) and more seen in ultra-processed beverages (P = 0·03) and ice cream, candies or salty packages snacks (P < 0·01) advertisements. Tasty and pleasure messages were more present in sandwiches and savoury snacks advertisements (P < 0·01) while less common in ultra-processed beverages (P = 0·03) and pizzas (P < 0·01) ones (Table 4).

Table 4. Participation of marketing strategies on advertisements in an online food delivery platform in accordance with the food groups

Discussion

The digital food environment represented by an online food delivery platform proved to be obesogenic in Brazil due to the expressive presence of unhealthy foods advertising during the COVID-19 pandemic. Characteristics related to the day of the week, mealtime and region of the country differentiated the advertisements.

The study described for the first time the profile of advertisements in a food delivery app in all Brazilian capitals in a moment when food commercial establishments were closed and the digital food environment represented an important way of acquiring ready-to-eat meals(Reference Oliveira, Abranches and Lana4). The study showed that unhealthy foods prevailed in the advertisements, mainly due to the presence of ultra-processed beverages and sandwiches, while the healthy foods, mainly represented by traditional meals and pasta, were advertised less frequently. Marketing strategies were more directed to advertisements containing unhealthy foods and prevailed the use of photos, discounts and free delivery.

In other words, when the digital food environment becomes one of the main means of acquiring ready-to-eat meals in the world(Reference Galanakis5,Reference Petetin6,Reference Rodrigues, Matos and Horta19) , advertisements promoted by restaurants registered in a food delivery app in Brazil were mostly focused on unhealthy meals and used marketing strategies in order to persuade the consumer to purchase these products.

Study conducted in 2019 described the use of photos and discounts and the menus of the restaurant registered in two online food delivery platforms in a Brazilian capital: ultra-processed beverages were present in 78·5 % of the restaurant menus, while water and natural juices and smoothies appeared in 49 and 27 % of the menus, respectively. Sandwiches, pizzas and fried snacks were options in 39, 13·8 and 16·6 % of the menus, while traditional meals were checked in 20·4 % of restaurant menus and vegetables in 16·9 %. The use of photos and discounts were more frequent in menus that offered meals containing unhealthy food groups compared with meals containing unprocessed and minimally processed foods(Reference Horta, Souza and Rocha8).

The frequent use of marketing strategies in food delivery platforms aims to persuade the consumers to buy inside the apps at the same time they are having a great experience of shopping. The literature has pointed out some potential drivers of online food delivery service: convenience, usage usefulness and hedonic motivations(Reference Yeo, Goh and Rezaei20–Reference Bates, Reeve and Trevena22). The marketing strategies used by the online food delivery platform under study aim to confer these characteristics to the digital environment.

The intense desire for convenience food is a result of rising household incomes, urbanisation and a reduction in the time available for activities such as cooking. More generally, reasons given for consuming meals prepared away from home include the desire for fast and filling meals, the cost and effort of cooking at home and a lack of time. Also, the usage usefulness of the food delivery apps is related to the costumers’ interest on technology that can provide saving time and effort. Thus, the website must be user friendly and be able to process the customer’s request as quickly as possible(Reference Yeo, Goh and Rezaei20–Reference Bates, Reeve and Trevena22). Combos strategy, for example, can help individuals chose a meal in an extremely fast way. Having certain discounts or promotions may also attract price-sensitive consumers, as they are likely to choose the channel which provides them the best value for money(Reference Yeo, Goh and Rezaei20–Reference Bates, Reeve and Trevena22). However, the time-saving factor is not the only motivation for using online food delivery platforms. Shopping motivations can also come from values and pleasure that consumer seeks from shopping(Reference Yeo, Goh and Rezaei20–Reference Bates, Reeve and Trevena22). Using photos and messages of healthiness or tasty and pleasure can enhance the hedonic experience of the consumer when shopping online.

In our study, the majority of the advertisements that contained marketing strategies, except for healthiness messages, was mainly directed to unhealthy food groups which is especially undesirable during the COVID-19 pandemic, as several studies have shown associations between the increased risk of mortality from this disease in obese patients and those with diabetes and hypertension(Reference Dietz and Santos-Burgoa23,Reference Kassir24) . Thus, in addition to the problem of stimulating an unhealthy diet for a population that is currently 55·4 % overweight and 20·3 % obese(25), increasing body weight in this epidemiological moment is linked to a worse prognosis for the COVID-19(Reference Dietz and Santos-Burgoa23,Reference Kassir24) .

The study has also pointed out differences in the profile of advertisements and marketing strategies use according to the mealtime, day of the week and region of the country. This differentiation is in line with the dietary pattern present in the country and the operational logic of commercial food establishments. For example, during lunch and during the week we noticed a greater promotional offer of traditional meals and vegetables. In Brazil, the consumption of vegetables at lunchtime is twice the amount consumed at dinner(Reference Canella, Louzada and Claro26) and, the Brazilian, in comparison with other populations, preserves the habit of having traditional meals, as well as the consumption of rice and beans(27–Reference Louzada, Martins and Canella29). In addition, self-service or kilo food restaurants operate during lunch hours, while pizzerias and hamburgers shops operate more prevalently at night and on weekends.

A greater participation of free delivery, combos and economy messages was also more noted for the dinner, when the presence of unhealthy foods advertising is higher. In contrast, the greatest use of photos and healthiness messages was found during the lunch period, which is the period of greatest supply of healthy food groups. Additionally, the tasty and pleasure messages were more common on the weekend period. Considering the regionality, restaurants of the North, Northeast and Midwest regions used less marketing strategies than the restaurants of the Southeast and South of Brazil. The profile of food acquisition in the North, Northeast and Midwest is characterised by a greater participation of unprocessed or minimally processed foods and a lower share of ultra-processed foods(27), which may explain the lesser incentive to consume unhealthy food groups in these regions.

Finally, it is worth highlighting the role that food delivery apps can exert for guaranteeing access to food during the COVID-19 pandemic. The predominance of using the digital media for acquiring food will remain after the pandemic as a safety measure to reduce all types of transmission of viral diseases(Reference Bakallis, Valdramidis and Argyropoulos14). In spite of this, the relative newness of the online food delivery platforms put them as a new route to the market as they do not fit into the categories of foodservice outlet, food retail outlet or manufacturer, which is a factor in its absence from public health policies(Reference Bates, Reeve and Trevena22).

In this regard, food delivery apps can be improved, for example, by including the list of ingredients and the nutritional information of the announced meals and reformulating portion size(Reference Bates, Reeve and Trevena22). In addition, these platforms need to be regulated by specific legislation in line with the known impact of food marketing on the health profile of the population, in order to not become another marketing space for unhealthy foods(Reference Bakallis, Valdramidis and Argyropoulos14,Reference Buchanan, Kelly and Yeatman30) . The present study contributes to this discussion by providing a description of the food advertising in an online food delivery platform in Brazil during the COVID-19 pandemic and points out possibilities for regulation so that this digital food environment is healthier for the population during and after this sanitary context.

Despite being unprecedented and relevant to the current health context in Brazil, the study has limitations that need to be highlighted. First, data collection involved all advertisements made by restaurants in the country’s twenty-seven capitals between the 13th and 14th weeks of the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, data collection occurred in an initial moment of the pandemic and by the absence of previous data describing the profile of advertisements in food delivery apps, it is not possible to state that the data described here represent a different scenario than the one before the installation of the pandemic. Despite this, data collection occurred at a time when the food delivery apps use had boosted in Brazil(7).

Furthermore, due to the fact that the study is not longitudinal and, therefore, did not describe all the advertisements published throughout the COVID-19 pandemic in Brazil, it is not possible to state that the scenario described represents the profile of advertisements throughout the installation of the pandemic in the country. The present group of researchers is addressing this issue by studying the profile of food advertisements published in delivery apps in a Brazilian capital during the months that followed the beginning of the pandemic.

Still, the study focused on the description of advertisements spread in a food delivery app, which does not refer to the totality of what is offered by the restaurants registered on this platform. Furthermore, other food delivery companies also operate online and characterise the digital food delivery environment in Brazil. In this way, the results of this investigation portray exclusively the advertising strategies that restaurants registered in a food delivery app used to boost sales during the pandemic of the COVID-19 in Brazil.

Ethical statement

The present study does not involve human participants.

Acknowledgements

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

P. M. H. participated in project preparation, data analysis and manuscript writing. J. P. M. participated in project preparation, database construction and critically revised the manuscript; L. L. M. participated in project preparation and critically revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final article.

There are no conflicts of interest.