A. Gender in Sociology of Law

What is the role of gender in sociology of law, and what is the relevance of sociology and law for gender? Law has traditionally been made by men, and even if today women and others are included in the lawmaking process, this demands a critical view of legal norms from a gender perspective. Among other goals, this Article aims to provide that view by raising questions and identifying where empirical and theoretical socio-legal research can and has contributed to the lawmaking process. For example: Does law do justice to all? Are legal regulations fair? In terms of such queries, empirical and sociological research can help to find deficits and discrepancies. Further questions include: In what way does sex or gender matter in legal professional work? Are there differences in acting and decisionmaking? In this regard, sociological theory can help explain power relations and bring previously unseen gender effects to the attention of society.

The operation of sex and gender in society, and their influence on law and vice versa, is not only the subject of socio-legal teaching and research, but also of performance and transformation in arts, along with providing a basis for political action and social measures. Given the historical development and circumstances, this activist element is particularly important and strong.

Speaking about gender in Germany needs a clarification in terminology. We use the term “Geschlecht” to refer to the biological sexes, the socially constructed gender, the genitals, and the ancestry or old family. The word “sex” is about sexual intercourse. As AngloAmerican scholars and politicians were trailblazers and influenced the discussion in Europe, the English word “gender” became common in German academia, being used for sex and gender issues. The result of this was confusion and friction across the population at large, who neither understood the term nor the concept. This, further, had the effect of weakening action for gender equality, and providing a fertile ground for antigenderist movements and polemics. The picture has since become ever more complex as—beyond the initial dichotomy of the sexes, with men on one side and women on the other—trans- and intersex—that is, diverse sexes and genders—now have to be included.

B. A Personal Account of the Beginnings, the 1960s and Early 1970s

Sociology of Law became a study subject in German law faculties in the course of the students’ movement of the 1960s—now colloquially referred to as the “68 movement.” In 1969 or 1970, I attended the first seminar in the sociology of law at the Chair of Andreas Heldrich at the University of Münster. The first socio-legal paper I heard was by Klaus ZiegertFootnote 1 on Podgorecki, and I also remember a paper on “Divorce in Ticino and Comasco,” which was just about the procedure, and not about either men’s or women’s specific problems, within divorce proceedings. Gender and women’s issues were still largely absent. Particular note should be made of the social context at that time; if families could afford it, then women—usually middle class women—were housewives in charge of the “interior” life of the family while men were the breadwinners and the family’s agent in the outside world.

Research on Knowledge and Opinion about Law (KoL) in the 1960sFootnote 2 had delivered empirical data on a general remoteness of women from the law—for example, women had been to law courts less often than men, had fewer contacts with lawyers, and would try to avoid legal action—noting what was referred to as women’s “negative legal consciousness.”Footnote 3 There were few female law students: In the early 1960s, only ten to fifteen percent of the law students were female, rising to seventeen percent by 1970. When women—with their higher voices—were asked to talk in a lecture, a loud laughter of many male throats resonated through the room, with the effect of—intentionally or not—creating doubt about the competence of the speaker. The result of this was that in seminars, women rarely raised their voices—a situation that has been described as “women´s classroom silence.”Footnote 4

It can thus be said that the law had neglected women’s particular needs and had yet to catch up with the gradually modernizing roles in society. For example, in the 1960s and early 1970s, there were hardly any women in Parliament. Until 1987, their share was less than ten percent. The law professors were men—often old—who naturally taught from a male perspective—that is to say, with male roles and behavior as the standard. Even more problematically, these professors had a habit of employing oldfashioned gender stereotypes in the usual madeup cases through which law is taught in Germany—scenarios that often diminished women.Footnote 5 Female legal academics, by contrast, were few and far between; the first woman law professor, Anne Eva Brauneck, a criminologist, was only appointed to a Chair in 1965—a year before I started to study. Female law students therefore felt estranged in their studies much more than men.Footnote 6 In terms of my own selfreflection on that time, I can say that I too found the usual dogmatism rather dull, as what I had to learn had nothing to do with my life, and this made me unhappy. With a view to changing this state of affairs I took seminars in English law, French law, comparative law, and the reception of law, all of which gave me a perspective on German law from the outside, and not only led me to compare legal regulations, that is, positive law, but also societies more generally, and their history. It helped me to come to terms with my legal education.

This was a time of critical thinking about society, which, in Germany, was coupled with an impetus to overcome the Nazi past and to create a better—in other words, a politically leftwing—society. This movement was fueled by U.S. students and the civil rights movement. It was predominantly about class and race barriers, however, which meant that gender—as an important socially interpretative category—was still absent. Pictures of students’ demonstrations in Germany at that time show men; of the very, very few women, many of those basically had the role of making the tea.

From 1971 to 1973, I spent two years at what is now the German University of Administrative Sciences in Speyer. It is worth noting that Niklas Luhmann had been working in Speyer for some years during the 1960s, and by the early 1970s, his systems theory was already widely read and cited. There, I attended a seminar in Sociology of Law with Hans Ryffel, presented a paper on “Rechtstatsachenforschung,”a paper about the forerunners of the sociology of law, such as Arthur Nussbaum and Eugen Ehrlich, and studied administrative sciences and sociology with the sociologist Renate Mayntz, the first woman ever to teach in Speyer. I also started an empirical research project on Freedom of Establishment for Lawyers in Europe. While interviewing Frederic A. Mann—an emigrated, high-profile lawyer—in London, he criticized me, alleging my approach to be unwissenschaftlich (“unscientific”) and far from reasonable jurisprudence. Pregnant at the time, upon leaving the room, I started to cry and wondered whether he would have said the same thing to a man.

A glance through the contents of older texts on sociology and the sociology of law confirms my recollection that the prominent scholars of the time paid little heed to issues of or concerning women, women rights, or gender. For example, Niklas Luhmann’s Sociology of Law Footnote 7 makes no mention of either women or gender, nor does Jakobus Wössner’s Introduction to Sociology Footnote 8—at the time, a very popular student text. Fischer’s Dictionary of Sociology Footnote 9 includes no article explicitly on gender. But gender is briefly referred to in an article on “institution,” which makes the argument that status in societies depends on sex/gender and age, and that there is a separation of work between the sexes. In its article on social change, it is mentioned that population movement is influenced by birth and death, to which questions of gender distribution and age distribution have to be added. Continuing along these lines: In Walter Rüegg’s Funk Kolleg Sociology,Footnote 10 there are brief remarks on gender roles in society, mainly in connection to “primitive societies” and anthropology; Rudolf Wiethölter’s Funk Kolleg Jurisprudence,Footnote 11—at the time, a mustread for all young critical jurists—only touches upon “Geschlechtsverkehr” (sexual intercourse) between engaged couples, in the context of discussing some amazing reasonings within judgments of the Highest Federal Court. In fact, with the exception of Susanne Baer’s recent textbook,Footnote 12 the terms “Geschlecht,” “gender,” “female,” or “woman” are not featured in Germanpublished books on the sociology of law.

C. Developments in the 1970s and 1980s

I. Women’s Rights and Women in Law

As a result of the first wave of the women’s movement in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, by 1918, women got the right to vote. Only thirty years later, after the second World War, in 1949, a gender equality clause was included in the new Constitution of the Federal Republic. However, this did not automatically abolish gender deficits and disparities in the law; the private law, for example, was still lagging behind. The first Gender Equality Law of 1957 abolished some of these deficits, notably the rule that a husband—with permission of the guardianship court—could terminate his wife’s employment if it affected the “marital interests.” Furthermore, until 1978—and the coming into force of the act on the adaptation of family law, Familienrechtsänderungsgesetz of 1977—the common family model accorded to a conservative ethos, that is to say, that the wife was in charge of the household, while the husband had to go to work and thus secure the family means.Footnote 13

By and by, however, women lawyers—many of them organized in the German Women Lawyers Association (Deutscher Juristinnenbund)—dealt systematically with these disadvantages and discriminations, taking cases in which the gender equality clause was infringed to the Federal Constitutional Court, and working on proposals for legislative change.Footnote 14 It was not an easy task, as some fields of law had no, or very few, female legal experts engaging with a gendered perspective—for example, social security law and tax law. Moreover, this task needed a thorough analysis of social reality. There were still few women in Parliament, legal academia, and legal practice, which in turn meant almost no female law professors and very few women in positions in the higher courts. From 1949 till 1987, out of sixteen judges at the Federal Constitutional Court, there was just a single female judge.

In the early 1970s, the women’s movement gained in momentum, in what became known as its “second wave.” It began with the famous article “I Have Aborted,” in the journal STERN on June 6, 1971, in which 374 women—some of them prominent and many in higher occupations—confessed that they had infringed the applicable law by terminating a pregnancy. This was the starting signal for women’s own “march through the institutions,” with the aims of: Undermining and destabilizing traditional gender concepts, making the private public, making women more visible, breaking men’s power monopolies, and implementing alternative female counterprojects to existing and dominant male worldviews. In research and science, these aims demanded critique, a radical “breaking [of] the [traditional] disciplines,”Footnote 15 a call for interdisciplinarity,Footnote 16 and a renewed commitment to systematically involving women’s issues in research and science.

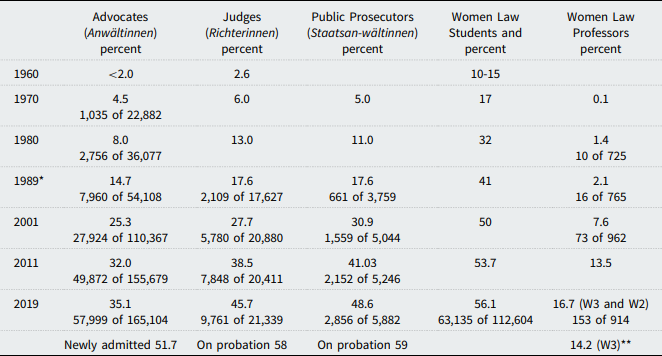

The following table shows the meager participation of women in law until well into the 1980s, juxtaposed with the current proportion of women in legal studies, the judiciary, in legal practice, and the legal academy, where the number of women is still strikingly lowFootnote 17.

Table 1. Proportion of women in the legal professions

* The increase in numbers after 1989 is due to reunification. The data before is only for West Germany.

**W3 are the fully equipped Chairs.

II. Sociology of Law Still Ignoring Gender Issues

At the beginning of the 1970s, discussions of a reform of legal education in Germany were started, which resulted in models of singlephase legal education with an integration of theory and practice, and an interdisciplinary approach with a stronger integration of the socalled foundation subjects. Alongside the sociology of law, there was also legal history, legal philosophy, legal theory, and law and economics. Even under these reformed educational models (Reformmodell), however, neither women’s rights nor gender issues were explicitly on the agenda, although the number of female law students had slowly started to rise. These models, which were to lead to the creation of several new law faculties throughout the country, lasted from 1971–1984.

In 1976, I went to the first meeting of the Vereinigung für Rechtssoziologie, now the Association for Law and Society, in Munich. To name a few of the other attendees: Gunther Teubner was there talking about autopoiesis, Klaus Röhl asking what added value autopoiesis could provide for his students, Erhard Blankenburg and Hubert Rottleuthner were the rising stars, and Thomas Raiser was also present. I had the opportunity to make the acquaintance of Blankenburg, with whom I shared a strong empirical inclination.Footnote 18 Gender issues were, however, absent from the academic program.

Ten years later, at the same association’s biannual meeting in 1987, I recall similarly few female contributors. I presented on “German Advocates: A Highly Regulated Profession,” my contribution to the large international comparative project “Lawyers in Society,”Footnote 19 and Vera Slupik presented her dissertation on the decision of the German Constitution for Parity in Gender Relation.Footnote 20 As far as I remember, we were the only women to present and were both given a brief time slot in the workinprogress, nonthematic panel. Also in attendance was Jutta Limbach, who was the fifth woman to get a Chair in a law faculty in West Germany and—at the time—the only female law professor who specialized in sociology of law, but there was no stream, section, or panel for either genderrelated topics or women’s issues more broadly. This brief exposition is simply to characterize the value which was given to gender subjects and to give some sense of the general atmosphere for women in legal academia at the time,Footnote 21 where—of course—only a few had elevated positions. Unfortunately, this remains much the case to this day; there are few women law professors who specialize in sociology of law, and gender has remained largely absent in both socio-legal teaching and in the teaching of law, although—and to a limited extent—this is arguably not the case in either criminology or sociology.Footnote 22

III. The First Gender Chairs in Law Faculties

In the 1980s, the former reform faculty of Bremen set up a first Chair in “law of gender relations.” The faculty was afraid of its own courage, as a dismal recruitment process started and was then stretched over several years,Footnote 23 affecting several prominent women. For example, Jutta Limbach, who—since 1972—had a Chair for civil law at the Free University in Berlin, went on to be the Senator of Justice in Berlin and the first female President of the Federal Constitutional Court in Germany. Another example is Ninon Colneric, who became President of the State Labor Court in SchleswigHolstein and one of the first female judges at the European Court of Justice; Ute Gerhard got the first Chair in Women and Gender Studies and Research in Germany—in the sociological faculty—in Frankfurt in 1987, and initiated the foundation of the Cornelia Goethe Centrum for Women and Gender Studies at the University of Frankfurt in 1997. Finally, in 1991, Ursula Rust got the Chair. In 2001, the denomination was changed to Gender Law, Labor Law, and Social Law, reducing the importance of gender. In 2007, Konstanze Plett was additionally appointed Professor of Gender and Law.Footnote 24

Doris Lucke, a sociologist who has published widely on gender issues in law, was appointed Titular Professor at the Institute for Political Sciences and Sociology in Bonn, in 1998.Footnote 25 She has a habilitation but never got a regular Chair.

In 1986, the FernUniversität in Hagen had been offered a Chair for a law professor in the context of the newly created Women’s & Gender Research Network NRW, which was to initiate and strengthen teaching and research on gender issues in all faculties in NorthrhineWestphalia.Footnote 26 The faculty wanted the Chair—which was paid out of a special fund—but not the gender expert. A long quarrel started, the idea of a Chair on women’s or gender issues in law got lost, and in 1993—finally—a man got the Chair. He was later the leading head in destroying my program on women’s rights, a kind of irony of fate. In 1997, Katharina von Schlieffen became the first female law professor at the law faculty. For some time, her Chair had sociology of law in its denomination. Currently, the Network consists of 160 professors and 249 scientists, but there is no special Chair in gender and law, and only one law professor has a Chair in criminal law and criminology that is connected to it.Footnote 27

D. Institutionalization of Gender Equality Politics

In the 1970s, the need to catch up on equality for women was internationally discussed and gradually gained wide recognition. The United Nations (UN) declared 1975 the International Year of Women. In 1979, the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) was adopted by the UN General Assembly. Gender equality issues also became part of European politics. The EEC Treaty of 1957 had a clause on equal pay for men and women—Article 119 EEC Treaty, later Article 141 ECTreaty—which aimed less at achieving gender equality and closing what was later called the gender pay gap, but rather to counterbalance competition imbalances between the member states. The ECC passed the Equal Pay Directive in 1975, and in 1976, the Equal Treatment Directive regarding access to employment, vocational training and promotion, and working conditions—76/207/EEC—was passed.Footnote 28 In Germany, after long deliberations, the Equal Treatment Directive was only incompletely transformed into national law in 1980. It had to be adapted, but gradually led to changes in labor law—often only initiated after court decisions.Footnote 29 In 1989, the Women’s Advancement Act was passed in Northrhine-Westphalia, introducing the first legal gender quota regulation. However, this is a soft quota which is only applicable in the civil service. Its impact was more symbolic, as it was difficult to prove equal qualification, particularly for higher positions. Therefore, the number of cases that have appeared in the German courts is limited.Footnote 30 As it turns out, the quota rule has proven highly effective, as it kept discussions about equal rights going, in spite of the widereaching disapproval it caused.

In the course of the 1980s equality politics was institutionalized. Some regretted this “socialization process of the women’s question” (Verstaatlichung der Frauenfrage), as they feared that women’s activism would lose in force as a consequence. However, change happened in the creation of the first positions for equal opportunities officers, for example. The Green Party was founded in 1980 and had gender as a core topic of interest. Initially, it had a strong conservative wing with ecofeminism, which subscribed to “difference models” of gender. In 1987, a Mothers’ Manifesto was published, favoring a model of society which cared for living together with children. After this, handicrafts and knitting became popular throughout Germany. The social democrats, and later the left party, reinforced the socialist tradition of the fight for women’s rights. In other words, women’s politics were professionalized, but women’s and gender issues were still absent in mainstream socio-legal teaching and teaching of law.

The institutionalized movement for gender equality, equal status, and standing gained momentum in the 1990s as the Federal and State Gender Equality Acts were passed.Footnote 31 In the 2000s, Gender Equality Offices had a solid legal and—more or less—solid financial basis in universities and throughout the civil service more generally. The Ministries for Women—established in the 1990s—disappeared again in the course of the first decade of the 2000s after the introduction of the gender mainstream strategy, which made gender issues a crosssectional task for all Ministries. Women’s issues found their way into coalition agreements between the Social Democrats and the Green Party, money was available for research, and teaching and activist projects on women’s rights flourished. The rising number of female politicians, members of Parliament in ministries, and members of the German Women Lawyers Association pushed the discussion of women’s and gender issues, and demanded necessary reforms in the law. In spite of all adaptations of legal regulations to the gender equality clause in the constitution, a lot remained to be done. The Ministry for Women in Northrhine-Westphalia commissioned four comprehensive handbooks for equal opportunities officers: Women and Law 2003, Images of Women 2004, Women and Demographic Change—The City, the Women and the Future 2006, and Women Change EUROPE Changes Women 2008. The first and the last had more legal foundations and a strong political stance; the other two had a focus on body perceptions, politics, and social change—a truly interdisciplinary project. For each, I assembled a host of authors: Mainly women, a few men—amongst them, scholars, practitioners, artists, and activists.Footnote 32 This helped me widen my meanwhile huge network of gender specialists on which I could draw for various projects.

E. Gender and Sociology of Law in the 1990s

Throughout the course of the 1990s, a few Chairs in sociology of law started to disappear when those who had held them retired. In line with international development, sociology of law shifted to a broader concept of law and society in Germany,Footnote 33 and with it, the duality of socio-legal research in sociology and the socio-legal research in law extended. Initially, there may have been curiosity between the disciplines. Now, it happened more often that sociologists criticized lawyers for a lack of theory, and the lawyers worried about complex theoretical concepts and incomprehensible language.

Interdisciplinary cooperation was on the agenda of the BAR (Berliner Arbeitskreis Rechtssoziologie),Footnote 34 which was founded in 2001 by a small group of scholars in social sciences and legal academics, all of whom were looking for an outlet for their research beyond the traditional disciplines. The longstanding institutions were the aforementioned German Association for Sociology of Law, which used to be dominated by lawyers. It changed its name, in 2010, to the “Association for Law and Society.”Footnote 35 There is also the small “Section Sociology of Law” of the German Sociological Association,Footnote 36 which mainly represents sociologists. The involvement of both in gender issues is still low. There are almost no links of the Section Sociology of Law to the Section “Women and Gender Research,” and gender issues are only occasionally dealt with in single presentations at meetings of the Association for the Sociology of Law.

Teaching sociology of law became obligatory within the law curriculum—for example, Section 11 (3) Law Education Act of Northrhine-Westphalia: “The compulsory subjects [for the first state examination] include their references to European law, taking particular account of the relationship between European law and national law, their philosophical, historical and social foundations, as well as the legal methods and methods of legal advisory practice.” However, gender is not explicitly mentioned. Socio-legal contents are usually offered by public law Chairs in which some gender competence is accumulated, as the interpretation of the equality clause—Article 3, Section 2 in the German Constitution—is a necessary part of teaching constitutional law and antidiscrimination law. Some reflections on gender can be taught by Chairs of criminal law and criminology—in the context of abortion, sexual and domestic violence, female genital mutilation, and more—but still, no foundations of gender are included in the German legal curriculum.

Gender issues became overall more accepted in research and teaching since the 1990s. However this did not mean that they spread throughout universities or became popular in law faculties. I was part of an initiative led by Klaus Röhl and taught women’s rights at the law faculty in Bochum. After eight years, I stopped teaching due to a lack of interested students signing up for the class—a fate shared by courses in the sociology of law. Women’s rights and gender subjects were seen, with suspicion, as sectarian, and judged as irrelevant for the dogmatic contents of the legal state examination. At the same time, I held seminars in the humanities faculty in Essen, which were (more than) well attended.

Since the late 1980s, equal opportunities officers and women’s groups invited me to innumerable lectures to empower them in legal questions and to motivate them to stand up for, and to promote legal change. However, they often could only gather small groups of attendees. A stable increase in participants has occurred only in the last decade.

In 1991, the first big international socio-legal meeting took place in Amsterdam—a milestone to remember. Gender was one of the central topics and was dealt with in plenaries. U.S. feminist legal academics “had impacted the philosophy of American Law since the 1980s to bring about new legal ideas (“memes”) and causes of action that reframed women’s issues and new interpretations of mainstream legal concepts.”Footnote 37 We, the continental European women, listened intensely. A postconference meeting with many of our American colleagues was organized in Bremen, giving motivation and impulses to gender in teaching and research. In 1995, Ursula Rust organized a Symposium called “Women Jurists at Universities—Women and Law in Research and Teaching” (Juristinnen an den Hochschulen—Frauenrecht in Forschung und Lehre) in Bremen, which brought together just about all women in legal academia interested in gender issues.

F. Gender in Socio-Legal Teaching and Research

I. Theoretical Underpinnings

The second wave feminist movement—in the 1980s—was influenced by gender difference theory, which—like the first women’s movement—assigned women genderspecific characteristics, be they cultural or biological. The leading idea was that women have “another voice” and are morally as good or even better than men.Footnote 38 The problem with this theory is that it drifts towards the “patriarchal dilemma,” reinforcing those men who always knew that “women are different”—meaning weaker.

In the 1990s, German feminist mainstream was dominated by sociologistsFootnote 39 and political scientists, committing itself to structuralism and the deconstruction of gender. Its aim was to overcome social gender—with its traditional gender roles and character constructed by the patriarchyFootnote 40—criticizing or even despising difference theoristsFootnote 41 as backwards and deprecatingly labelling them as essentialist, although many feminists cherished a “we, the women” rhetoric, which in itself presupposes difference. There was a change in paradigm from women’s rights to gender equality, in line with gender mainstreaming, which had been introduced as a strategy of European equality politics at the fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing, in 1995. Gender mainstreaming was integrated in the Treaty of Amsterdam 1997/1999 and adopted as a guiding principle by the German federal government in 1999. Women’s offices and councils were renamed gender equality bodies (Gleichstellungsstelle). Additionally, women’s committees and other women’s institutions were kept to safeguard women’s particular interests and protect women against discrimination.

After the turn of the millennium, theories stressing diversity prevailed. This put the focus on the individual, with his or her complex bundle of qualities, character traits, and different biographical factors—including age, education, financial situation, family status, political views, health, sexual orientation, and more—sex being just one factor among others. The problem with individualistic theories is that it is difficult to build research hypotheses on them, and it is further complicated by intersectional discrimination.Footnote 42

In the past two decades, it has become evident that the binary twosex model did not fit accepted social reality anymore, that legal adaptations were necessary, and that the gender perspective was opened to include queer. Rüdiger Lautmann, a trained lawyer and professor of sociology and sociology of law in Bremen, had already set up a department on Gender and Sexual Relationship in the Institute for Empirical and Applied Sociology in 1988. Further, in 1995, he founded the first center for gaylesbian studies in Germany. There were only loose connections and almost no cooperation between Lautmann and the women who specialized in gender and law. In 2006, an Institute for Queer Theory was founded.Footnote 43 In recent years, the theoretical concepts were further expanded, and concepts of masculinities were included in legal gender work.

II. The First Comprehensive Program on Women and Law

In 1985, I got the chance at my university to organize a series of lectures on “Women and Law.” There were still hardly any women in the faculties; the first female professor, a psychologist, had just got a Chair. At the time, I was head of the didactics unit for the law faculty in a central didactic facility. The university, in a reform model, aimed to offer higher education to disadvantaged groups who could not attend onsite teaching: “[W]orkmen, women, disabled persons, [and] prisoners.” Teaching occurs through a combination of written course materials, new media, and via the internet.

My position opened up the possibility to deal with “nonconventional” subjects. However, in spite of reform ideas, in the 1980s, didactics of law became a subject doomed to a shadowy existence until well into the 2000s. Law faculties in Germany have a very traditional teaching culture. There is no stringent curriculum leading to the examination—just a catalog of subjects relevant for the examination, which is defined by the Ministries of Justice of the Federal States, who also organize the examination.Footnote 44

As I was in charge of media work, the lectures on women and law were videorecorded and presented in our university TV series, which gave a lot of visibility and high prestige to the project.Footnote 45 The aim of the lectures was to inform about legal questions relevant for women: To find deficits, articulate critique, make proposals for law reform, and lobby for reform. Over ten years, the lectures mapped the areas of law with—at the time—the most important inequalities: Disadvantages and discrimination in family law, social law, labor law and quota regulations, pension and tax law, problems of nonmarital partnerships, violence against women, the medieval procedural code against witchcraft, abortion, invitro fertilization, women migrants and the law, male legal language, the masculinity of the legal profession, and the impact of the constitutional reform after reunification on women’s rights. Presenting were practitioners, members of Parliament, the first female federal Minister of Justice, scholars, activists, high judges, leading politicians, and the few female law professors dealing with women and gender questions in law—in other words, the most knowledgeable women on questions of women’s rights, who—at the time—were still quite rare. They were all lawyers, as the focus was on law reform, but with a solid empirical foundation. The few law professors included were Jutta Limbach, who taught civil law, Heide Pfarr, who taught labor law, and Monika Frommel, who taught criminal law. We were pioneers and felt like it. Meeting decades later, as grayhaired women, we still remember the importance of our project.

Based on the collected material, I set up a oneyear certification program of further education on Women and Law which became increasingly used by the growing number of equal opportunities officers as proof of qualification. I had no special resources for the program except my enthusiasm. The rector was my mentor; when he left in 1993, I was considered to be “masterless”—putting me in a vulnerable position. In 1987, the allmale law faculty at FernUniversität in Hagen decided to abolish “Frauen im Recht” on the grounds that “[w]e do not have these problems anymore.” I had been watched suspiciously as one who was questioning the legal system and organizational structures: A dangerous woman with dangerous, inconvenient knowledge. The few female professors at FernUniversität in Hagen—there were still none in law—had been afraid to fill the gap and jump in to support a contested program.

I received a big grant for virtual international gender studies from the government, supported by the NRW Ministry for Research, between 2000–2004. This funding and recognition enabled me to bring my subject back into the conversation and the university. In the framework of the project, I set up a qualification for equal opportunities work. As gender and law deals with issues in all fields of law, I had to draw on the expertise of many authors who specialized in different subjects. I had to be creative in keeping the program going. I managed this through obtaining money from additional small research projects and making use of other publications in which I was involved.

III. Gender Recognized as Element for Quality of Teaching

Since the 2000s, measures to strengthen the quality of teaching (“Qualität der Lehre—QdL”)Footnote 46 have called for gender content to be included in teaching. Highquality teaching should be designed to be gender- and diversityfriendly. Corresponding guidelines are anchored in women’s promotion plans and equality policies of universities; some universities have specific gender portals. In the accreditation of degree programs, which was introduced as part of the Bologna process, the criterion “equal opportunities” is also used to check whether sufficient gender content is offered in teaching. In the legal field, this concerns the bachelor’s and master’s in business law. As already stated, classical law studies are exempt from accreditations. Overall, the offer of gender content in law faculties is still sparse.Footnote 47

In the mid2000s, my university was undergoing restructuring, and this put my course for equal opportunities at risk. I returned in 2008, after thirty years, to the faculty which had—in the meantime—changed its structure. Men and women had Chairs, and I had the chance to offer a module on gender in the master’s of laws. In the accreditation for the master’s, the demand had explicitly been put forward to add gender in teaching law. For the first time in my life, I was received—more or less—with open arms in the faculty. Meanwhile, teaching on gender and appointing women to a Chair had also become success factors at universities, which gave the faculty extra funding until I retired in 2014. In 2016, limited for five years, the faculty had the chance to appoint a gender Chair. For two years, Ulrike Lembke held it; and since then, Anja Böning has held it.

IV. A Gender Curriculum

In 2008, I contributed a gender curriculum for law to a gender curricula website of the “Network for Women’s and Gender Research,”Footnote 48 which I updated in 2012.Footnote 49 In the introduction, I stated: “In classical teaching, gender aspects are negated or overlooked. In the past decade, in the course of a shortening of legal education, the dogmatic training came to the fore and a clear tendency towards positivism (an orientation of the teaching to the applicable law and its application) was ascertained.”Footnote 50

I further characterized my approach as follows:

The … proposals for imparting legal gender competence follow the ideas of a critical jurisprudence. In the course of feminist criticism of science, a fundamental curriculum revision would be required, which would lead to a different structuring and weighting of the course content. Abstract theoretical interpretation of the law would take a back seat in favor of practical knowledge and application transfer. This would also remove the distinction between substantive law and formal procedural law. It is important to strengthen legal didactics and to ultimately rethink traditional ideas about the goals of law studies and the methods of mediation.Footnote 51

As the gender aspect is a crosscutting issue, I proposed that it should be a focus of study in the basic subjects: Introduction to law, legal history, legal sociology, and legal philosophy and methodology. In addition, the gender perspective should be an integral part of all courses with regard to justice issues and legal criticism. In addition, a special module on women/gender and law could be offered. Although I tried to publicize the draft widely—and asked for comments and additions—in all these years, only one colleague contacted me, but just to ask me for advice in relation to her teaching.

V. Research and Teaching on Gender and Law

In 2002, Susanne Baer got a Chair at Humboldt University in Berlin for public law and gender studies. Between 2003–2010, she founded and organized a gender competence center and was subsequently also cofounder and first head of the Gender Studies Association, founded in Berlin in 2010. In 2011, she was elected to be a judge at the Federal Constitutional Court. Her work combines—in a unique way—gender with socio-legal competence, and she has written a study book on Sociology of Law as an introduction to interdisciplinary legal research, which includes feminist perspectives.Footnote 52 Her Chair, which is represented during her term at the court by Ulrike Lembke,Footnote 53 is the Centre for Manifold Activities and Research Projects on Gender Issues. Attached to the Chair is the Humboldt Law Clinic for Basic and Human Rights (HLCMR), which takes a feminist stance.

An active group of young women from Berlin and Hamburg—among them, DanaSophia Valentiner and Selma Gather, linked to the German Women Jurists Association—is dealing with feminist demands for improving legal education,—that is, the use of gender neutral language and gender adequate and sensitive construction of cases used in training, tests, and examinations.Footnote 54 The various offers on gender issues in law show a clear north/south divide, however. Financing options have an impact, which means that some programs which emerged will disappear again. A center for research and teaching on gender and law has been set up in Frankfurt, connected to the Chair of Ute Sacksofsky and the Cornelia Goethe Centrum for Women and Gender Studies. At the University of Hamburg courses are offered in Legal Gender Studies, (also at the University of Vienna connected to Elisabeth HolzleithnerFootnote 55 and the University of Basel connected to Andrea MaihoferFootnote 56, and Gesine Fuchs in LuzernFootnote 57). At the University of Marburg a “Mobile Study Day Feminist Law” is held regularly, individual courses and courses on gender issues in law are offered at the Universities of Bremen, Bielefeld, Frankfurt,Footnote 58 and a few others in Germany. Lectures on relevant topics are offered by a number of faculties—for example, connected to the Chair of Friederike Wapler in Mainz, Eva Kocher in Frankfurt/Oder, and Katharina Mangold at the newly founded European University in Flensburg, which—it should be noted—has no law faculty, prioritizing business studies.Footnote 59

While there is little in the mainstream legal literature on gender issues in law, there are some publications on women’s rights, law and gender, and anthologies and monographs: For example, the study book Feminist Law, published by Lena Foljanty and Ulrike LembkeFootnote 60; the collection of sources Legal Gender Studies, published by Andrea Büchler and Michelle CottierFootnote 61; the feminist legal journal STREIT; and the journal of the German Women Lawyers’ Association djbZ.Footnote 62

In spite of the limited institutionalization in law faculties, a lot of gender research is done in individual single projects within the forty-three law faculties in Germany. In the past two decades, almost all socio-legal conferences—except for those on special subjects—have had sessions on gender issues. Impressive evidence of it has been given at meetings of the socio-legal scholars in the Germanspeaking countries in the past ten years, where gender issues were dealt with in several streams, giving impulses to new socio-legal research.

The socio-legal blogFootnote 63 that Klaus Röhl runs provides an inexhaustible source of inspiration—tracking the developments in law and society and discussions on gender. An entry, for example, of the 8th of November 8, 2019, is titled “Feminist Legal Studies have Arrived at the Center of Jurisprudence” and deals with some of the contributions to a section on “Broadening Perspectives Through Gender Research in Law” in the 2019 yearbook of public law.Footnote 64 There are, however—as is obvious from the names cited—few men who engage in gender issues beyond the interpretation of the gender equality clause in constitutional law.

After the turn of the millennium, with the introduction of gender mainstreaming strategy, gender education became obligatory in the civil service and the judiciary. For a couple of years, gender training was arranged, which encountered incomprehension and objection.Footnote 65 It was then included as a mandatory requirement in guidelines for further education, functioned as fig leaves, and was forgotten after some time. This was partly compensated by the growing number of women involved as trainers, who included gender issues in their regular teaching, and acceptance was reinforced by the growing number of women in leading positions.

VI. Research on Women/Gender in the Legal Profession(s)

My own research is focused on women and gender in the legal profession. It was only loosely connected to my work at FernUniversität in Hagen, and is more of a private passion. In 1994, I became head of a Women in the Legal Profession Group, a subgroup of the Working Group on Comparative Studies of Legal Professions.Footnote 66 This led to several workshops, a triad of three big comparative international publications,Footnote 67 and several special issues in the International Journal of the Legal Profession.Footnote 68 We also organized a collaborative research network on gender and judging in the framework of the American Law and Society Association. The next project will be on Women in Customary Law and Proceedings.Footnote 69

In 2008, I received a grant from the Ministry of Justice in NorthrhineWestphalia for empirical research on women in leading positions in the judiciary—or rather, why there were so few of them.Footnote 70 In 2011, I received a governmental grant from the funding line “Women to the Top” for nationwide research into the dismal situation of female law professors,Footnote 71 who still—in 2020—hold only about sixteen percent of the Chairs. In the framework of the project, I set up a website on Gender and Law, with video interviews of experts on gender issues in law and with personality portraits of female law professors, for which I was awarded some additional funding.Footnote 72

G. Problems for Institutionalizing Gender in Socio-Legal Teaching and Research

Why is it so difficult to institutionalize gender in teaching and research in law faculties and gain recognition for it? As mentioned above, legal education is resistant to change, and gender is not part of traditional law faculty culture. Women’s and gender issues have been regarded as representing special interests not deserving to be consolidated as concrete study subjects.

Another problem is the divides between actors in gender equality teaching, research, and practice. In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, there was a divide between the bourgeois and the socialist women. The moderate and the radical wing of the women’s movement had different focuses: The former with a focus on women’s roles as housewives and mothers, the socialist women feeling closer to the male labor movement, but both with a positive evaluation of motherliness and femininity, united in their striving for women’s access to education and professional work. Today, it is the gulf between conservative and progressive women. Gender specialists differ in their standpoints and political stances, and differing opinions are not always treated with tolerance.

Some of the gender experts in law and sociology of law selfidentify as feminists. For scholars in the AngloAmerican world, it is common, while continental—particularly German—lawyers shy away from the word feminist, as -isms may signal ideological attitudes. Some of the women label themselves as women’s rights lawyers (Frauenrechtlerin), which sounds somewhat oldfashioned. The question is whether these labels—which signal a preoccupation with women’s issues—still fit in times when the focus of gender has opened to include masculinities and when the boundaries between the sexes and genders have been dissolved, and equal rights and fair treatment of the multiple sexes and genders are discussed.

The big divide is that between social sciences and law. Gender research is mainly anchored in the humanities, sociology, and cultural sciences, and has started to boom in the past fifteen years. Sociology dominates theory building within the field of gender studies. Many gender Chairs were established in the disciplines, and many more Chairs got an additional denomination, “gender.” Innumerable gender conferences are held. The rising number of women in politics and in higher positions in ministries—backed up by left, socialdemocratic, and green prowomen, and later “gender” party politics—created possibilities for funding of research, teaching projects, and Chairs. There is only a limited cooperation with the small number of women in the legal academy who are engaged in women’s and gender issues. Except for a handful of us, women legal academics rarely present at gender conferences in Germany. The concepts and language used in social sciences—often with many anglicisms, particularities, aloof issues, and conferences in the English language when maybe just one participant does not speak German—have created a special segment in academia, which of course is necessary, but remote from the usages in law which has a strong orientation to practice. This causes frictions.

Additionally, there is a funding dilemma for socio-legal research. The Ministries of Justice, and the federal and state ministries, have very limited resources. The Ministry for Research and Education BMBF would rather fund projects in the humanities, sociology, and cultural sciences,Footnote 73 and the law has no culture of externallyfunded projects.Footnote 74

There is a comparable divide between the academic gender research, and the institutionalized women’s movement and gender work in equal opportunities offices, despite many of the EO officers in the civil service and public administration having a degree in sociology or political sciences. Theoretical concepts do not help them in their daily work, although they need impulses and ideas from outside.Footnote 75 To bridge the gap, since 2006, I have been editing—with Sabine Berghahn—a legal handbook for equal opportunities officers with regular supplements and a website.Footnote 76

One of the biggest obstacles is, however, that overall gender equality is still considered a women’s project, and that in spite of all the political support, most men have not accepted it as their task—by and large, they stand on the margins and avoid being involved.

H. Where to?

Considering equal rights for women, and the political and economic situation of women in society, a lot has been achieved.Footnote 77 The development in the past decades has been breathtaking. Of course, the balance for gender justice is sensible; society changes, gender arrangements are modernizing, and with it, the perceptions and demands of people change. The development has to be carefully observed and the law always needs readjustment. There are still battles left to be fought, and there are always issues to be discussed critically. As described, scholars and practitioners of the German Women Lawyers’ Association—but also women in legal academia and social science—played a leading role in the process of change. Since 2005, the government has commissioned gender equality reports to which they have contributed.Footnote 78 The reports give an account of the status of society and the identified needs of further change. The first one, “New Ways—Equal Opportunities. Equality Between Women and Men in Their Life-Course,” was published in 2011. The second, on “Shaping and Implementing Employment and Care Work,” was published in 2017. The work on the third one has started.

This means that socio-legal perspectives of gender are as important as ever, and they have to be included in regular teaching. But gender cannot be seen separate from other aspects of diversity. For example, of growing importance is ethnicity due to increased migration. In the end, the aim is that theory has to find answers for the question: What is the life we—men, women, trans, intersex, and nonbinary people—want to have? Therefore, politics needs to build on socio-legal empirical evidence.