There is no such thing as a single-issue struggle, because we do not live single-issue lives. (Lorde Reference Lorde and Apter1984)

Even the casual observer of US society must take note of the speed and ease with which nonpolitical matters become embroiled in political conflict. Familiar partisan and ideological divisions seem to creep into everything: from dating apps to pandemic behavior; decisions about where to live and what to eat; and deeper value, religious, and moral commitments.Footnote 1 The primacy of left–right conflict calls out for a reconsideration of the nature and meaning of ideological constraint in the US mass public.

Indeed, scholars have come to recognize that political polarization should be understood not simply by the depth of policy differences between political factions, but also by their breadth—the sheer number and variety of issues or controversies that define partisan-ideological conflict (see, for example, Baldassarri and Gelman Reference Baldassarri and Gelman2008; DellaPosta Reference DellaPostaforthcoming). Layman and Carsey (Reference Layman and Carsey2002a, Reference Layman and Carsey2002b) termed this phenomenon “conflict extension,” contrasting it with “conflict displacement.” Under conflict displacement, new issues arise to replace the primary dimension of competition (see, for example, Miller and Schofield Reference Miller and Schofield2003). With conflict extension, new divisions are instead added to existing lines of political conflict. For example, voters who previously disagreed about universal healthcare and the estate tax would also disagree about abortion and race relations.

The level of conflict extension in the mass public speaks to a fundamental trade-off in a pluralistic democracy. On the one hand, the presence of reinforcing policy cleavages—particularly those involving emotional, “high heat” social and cultural matters—changes the tenor of democratic deliberation (Hetherington Reference Hetherington2009). Political competition becomes Manichaean: less transactional and more messianic. This environment fosters partisan-ideological antipathy, resistance to compromise, and other manifestations of affective polarization (see, for example, Enders and Lupton Reference Enders and Luptonforthcoming). However, scholars have also long bemoaned the electorate's inability to organize their political preferences in ideological terms (Converse Reference Converse and Apter1964; Kinder and Kalmoe Reference Kinder and Kalmoe2017). Ideology fosters democratic accountability by providing a heuristic, enabling elites to efficiently communicate with voters and voters to make choices on the basis of low-dimensional ideological proximity (Hinich and Munger Reference Hinich and Munger1994; Stoetzer Reference Stoetzer2019). Conflict extension serves to facilitate ideological thinking in the mass electorate by more clearly connecting policy positions and defining “what goes with what” across a wide range of issues.

This article examines conflict extension and ideological structure in the US mass public over the last forty years. It does so by measuring the degree to which American voters' attitudes on a range of policy issues have become constrained along a common, latent left–right ideological dimension. The key innovation in this article is its use of a dynamic measurement model that explicitly models changes in the mappings between individual issue attitudes and a latent organizing ideological dimension over time. This captures processes such as issue evolution (where issues become more or less “ideological” as a consequence of changes in the political environment) (Carmines and Stimson Reference Carmines and Stimson1989) alongside left–right shifts in public opinion on controversies such as lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, and queer (LGBTQ) rights. This not only provides more credibly comparable measures of voters' ideological positions across time, but also allows us to identify which issues load onto the latent conflict dimension, how strongly, and how these loadings evolve.Footnote 2

Applying this measurement strategy to repeated cross-sectional survey data from the American National Election Study (ANES) Time Series studies between 1980 and 2016 yields a series of important substantive findings. First, there has been a consistent trend toward greater conflict extension in Americans' policy attitudes over the last forty years. Specifically, social/cultural issue attitudes and core value dispositions have been increasingly absorbed into the primary left–right conflict dimension, supplementing rather than displacing economic policy preferences and values on this dimension. In addition, citizens with low and moderate levels of political sophistication are catching up to their highly sophisticated counterparts in terms of ideological constraint. These results provide a more nuanced account of mass political polarization—one where partisan conflict has become more widespread and intense by encompassing a larger, overlapping set of policy disagreements and value differences.

Ideological Structure in US Public Opinion

Across time and space, political elites compete over a single left–right ideological dimension. This dimension of conflict has become especially pronounced in the United States over recent decades. Members of Congress (Poole and Rosenthal Reference Poole and Rosenthal2007), state legislators (Shor and McCarty Reference Shor and McCarty2011), campaign contributors (Bonica Reference Bonica2014), and party activists (Lupton, Myers, and Thornton Reference Lupton, Myers and Thornton2015) all take policy stances that conform to a left–right continuum. Although citizens must grapple with a unidimensional choice set presented by highly constrained elites, to what extent do voters themselves hold attitudes that fit the same left–right structure?

The scholarly dispute over the degree to which Americans are “ideologically innocent” was launched by Converse's (Reference Converse and Apter1964) famous essay. Converse's results unambiguously supported the proposition that only a small proportion of Americans can be characterized as ideological, with the rest lacking a meaningful understanding of ideological terms and holding unstable policy preferences across time. Survey respondents' attitudes also exhibited negligible levels of constraint or systematic organization, namely, the observed correlations between pairs of respondents' issue attitudes were extremely low, rarely greater than 0.3, and often negative.

Popkin (Reference Popkin2006, 233) writes that Converse's essay “is at one and the same time a milestone and a millstone.” Indeed, in the half-century since its publication, it continues to define the subfield (see, for example, Kinder and Kalmoe Reference Kinder and Kalmoe2017), even as its conclusions have been challenged on multiple fronts. For one, many scholars have argued that attitudinal constraint is tied to the amount and clarity of ideological conflict present in the political environment. Indeed, later studies found considerably higher intercorrelations between issue attitudes, and attributed this result to a shift from the relatively ideologically tranquil environment of the 1950s to the more tumultuous period of the 1960s (Nie, Verba, and Petrocik Reference Nie, Verba and Petrocik1979). Greater ideological conflict on salient issues like civil rights and Vietnam seemed to clarify the ideological connections between policy issues for voters.

According to this view, the political environment and the nature of the two-party system promote ideological constraint in the mass public by packaging and communicating competing “menus” of policy positions (Sniderman and Bullock Reference Sniderman, Bullock, Saris and Sniderman2004; Stimson Reference Stimson2015). As Sniderman (Reference Sniderman2017, 43) argues: “[I]t has tacitly been supposed that citizens must organize ideas relying on their own resources. That is not so. The ecology of the party system affords partisans an opportunity to make ideologically coherent choices without exceptional effort on their part.” Parties are certainly not the only political actors involved in defining ideological agendas (see, for example, Noel Reference Noel2013), but they are the most effective channel for communicating ideological distinctions to the electorate.

Contemporary elite-level polarization provides such a clarifying environment for voters. Over recent decades, party leaders, activists, candidates, and other political elites have increasingly taken ideologically consistent positions on a range of economic and noneconomic policy issues. This has served to promote voters' awareness of ideological differences between the parties and—according to elite-centered perspectives—driven partisan sorting (that is, the alignment of partisanship and ideology) in the mass electorate (Abramowitz and Saunders Reference Abramowitz and Saunders1998; Enders and Armaly Reference Enders and Armaly2019; Levendusky Reference Levendusky2009). Several mechanisms—generational replacement, partisan change, and ideological conversion—each contribute to a feedback loop that produces sorting, creates more homogeneous party coalitions, and better signals to voters the connection between partisanship and issues (Carsey and Layman Reference Carsey and Layman2006; Highton and Kam Reference Highton and Kam2011; Stoker and Jennings Reference Stoker and Jennings2008). Comparative work demonstrates that these patterns also work in reverse, for instance, elite depolarization (as began in Britain during the 1990s) produces lower rates of partisan sorting in the mass electorate (Adams, Green, and Milazzo Reference Adams, Green and Milazzo2012).

If political context conditions mass constraint, we should expect to find that politically aware citizens hold more ideologically constrained preferences. Indeed, this relationship is one of the more robust findings in the study of political behavior. Beginning with Converse (Reference Converse and Apter1964), scholars have demonstrated that citizens with higher levels of education, political knowledge, and political engagement possess better-constrained attitude structures that connect issue positions across policy domains (Jacoby Reference Jacoby1991; Lupton, Myers, and Thornton Reference Lupton, Myers and Thornton2015; Stimson Reference Stimson1975). Recognition of the parties' relative left–right positions—distinctions that have been better clarified in recent decades—is an especially important predictor of attitude stability and ideological consistency (Freeder, Lenz, and Turney Reference Freeder, Lenz and Turney2019; Palfrey and Poole Reference Palfrey and Poole1987). Hence, while aggregate studies are useful in assessing the ideological structure of policy attitudes in the electorate as a whole, such an approach can also mask substantial heterogeneity present under the surface of public opinion. We should expect to find higher levels of attitudinal constraint among politically sophisticated citizens than their less sophisticated counterparts, even if contemporary polarization has served to close the gap by providing clearer ideological cues (Levendusky Reference Levendusky2010; Zingher and Flynn Reference Zingher and Flynn2019).

There have also been sustained methodological challenges to Converse's results and, more generally, the use of issue intercorrelations to measure ideological constraint. Single-issue scales are especially vulnerable to measurement error (for example, due to vague or poorly worded survey instruments), and this downwardly biases observed levels of attitudinal stability and constraint (Achen Reference Achen1975). Aggregating multiple-issue questions—either through simple additive scales or more sophisticated measurement models—serves to correct for measurement error present in individual survey responses (Ansolabehere, Rodden, and Snyder Reference Ansolabehere, Rodden and Snyder2008; Jackson Reference Jackson1983). Consequently, more sophisticated measurement models of public opinion have tended to produce more optimistic conclusions about the degree of ideological structure underlying mass policy preferences (Freeze and Montgomery Reference Freeze and Montgomery2016; Shor and Rogowski Reference Shor and Rogowski2018).Footnote 3

Finally, scholars have become increasingly appreciative of the role that core values and beliefs can serve in constraining citizens' political attitudes. The idea that core values (or “crowning postures”) could serve to link policy preferences along overarching principles also finds its roots in Converse (Reference Converse and Apter1964, 210–11) and has been empirically demonstrated in subsequent work (Feldman Reference Feldman, Sears, Huddy and Jervis2003). Since core values and value hierarchies are universal components of human behavior, they also have the potential to provide accessible gateways to ideological structure. Goren (Reference Goren2013), for instance, shows that both politically sophisticated and unsophisticated citizens derive specific issue attitudes from basic principles concerning the role of government in general policy domains (see also Goren, Smith, and Motta Reference Goren, Smith and Mottaforthcoming).

The constraining effect of core values is contingent, of course, on the degree to which value and partisan-ideological conflict overlap in the political environment. This is an alignment that has indeed grown more pronounced in recent years (Barker and Tinnick Reference Barker and Tinnick2006; Jacoby Reference Jacoby2014), fostered by the rise of symbolic, value-laden “easy” issues (Carmines and Stimson Reference Carmines and Stimson1980) on the political agenda and the use of elite rhetoric that connects core values and party positions (Clifford and Jerit Reference Clifford and Jerit2013; Hetherington and Weiler Reference Hetherington and Weiler2009; Lupton, Smallpage, and Enders Reference Lupton, Smallpage and Enders2020).Footnote 4 Partisans should also be more likely to accept their party's issue policy positions if they believe they share an underlying set of core values and principles, especially when those positions are presented in polarized terms (Druckman, Peterson, and Slothuus Reference Druckman, Peterson and Slothuus2013).

Conflict Extension in the Mass Electorate

We should expect to find higher levels of mass ideological constraint when political parties and other elite actors are simultaneously polarized on a large number of policy issues and core values. Indeed, while most studies of mass polarization focus on changes in the ideological positions of citizens over time, this type of analysis tells only part of the story. Polarization also involves changes in the meaning of the left–right dimension that defines and drives political conflict.

This aspect of polarization presents a deep normative trade-off. As political competition incorporates a wider set of policy and non-policy cleavages, citizens have access to a larger number of pathways to ideological constraint. Political choices are clearer and elections become more meaningful. Moreover, when citizens' policy attitudes conform to the same dimension over which candidates and parties compete, mass–elite representational linkages become more direct. However, when cross-cutting conflicts begin to overlap, the resulting “meta-cleavage” also strains democratic deliberation and consensus in a pluralistic society (Habermas Reference Habermas1996; Hetherington Reference Hetherington2009). Berelson (Reference Berelson1952, 328) warned of the risks associated with “total politics”:

[E]ven at the height of a presidential campaign there are sizable attitudinal minorities within each party and each social group on political issues, and thus sizable attitudinal agreements across party and group lines. Such overlappings link various groups together and prevent their further estrangement. All of this means that democratic politics in this country is happily not total politics—a situation where politics is the single or central selector and rejector, where other social differences are drawn on top of political lines.

The theory of “conflict extension” (Layman and Carsey Reference Layman and Carsey2002a) provides a framework to explain how a diverse set of issues can be absorbed into a single dimension of political competition. Conflict extension places itself in contrast to “conflict displacement,” which posits that as new controversies or buried partisan cross-cutting divisions gain salience, they supplant the dominant dimension of political conflict (Miller and Schofield Reference Miller and Schofield2003; Sundquist Reference Sundquist1983). Partisan-ideological conflict is reorganized around the new cleavage—as was the case with the issue of slavery in the lead-up to the American Civil War—while the parties depolarize on the displaced conflict.

According to the conflict extension perspective, new cleavages need not replace existing ones; rather, parties can simultaneously polarize across multiple policy domains. This process is driven by policy-focused party activists and engaged issue publics, both of whom push the parties toward extreme positions on their principal issue(s) while personally converting on issues they find less salient (see also Bawn et al. Reference Bawn2012; Carsey and Layman Reference Carsey and Layman2006; Layman et al. Reference Layman2010). Although there are some constraints on the universe of feasible configurations of policy positions that party coalitions can realistically adopt (see, for example, Noel Reference Noel2013; O'Brian Reference O'Brianforthcoming; Schickler Reference Schickler2016), parties nonetheless enjoy wide latitude in bundling a set of overlapping conflicts into stable ideological configurations, as the nature of polarization in contemporary US politics has demonstrated.

The process of conflict extension tends to reinforce itself through a positive feedback loop. Overlapping conflicts provide multiple pathways to the same partisan-ideological configuration. Better-sorted voters, in turn, further clarify party differences. Each process feeds into the other, and partisan competition engulfs both a wider set of conflicts and a larger segment of the electorate. Consequently, when the same political opponents repeatedly clash over emotional issues and fundamental values with messianic zeal, it becomes easier to view the other side as evil rather than merely incorrect (Hunter Reference Hunter1991). It is not surprising that compromise becomes more elusive and acrimony more widespread in such an environment (Davis Reference Davis2019; Iyengar and Westwood Reference Iyengar and Westwood2015; Orr and Huber Reference Orr and Huber2020; Rogowski and Sutherland Reference Rogowski and Sutherland2016).

While conflict extension has been most pronounced at the elite level, to date, there has been only limited evidence that voters are also bringing their attitudes on economic, social, and racial issues into greater unidimensional alignment (Layman and Carsey Reference Layman and Carsey2002a, Layman and Carsey Reference Layman and Carsey2002b). This article offers an updated assessment of mass constraint by developing a method that directly measures changes in the mappings between specific issues and a latent ideological dimension in the mass electorate, and applying it to survey data over the last forty years. This provides a novel way to model the dynamics of ideological constraint and conflict extension among voters.

The Bayesian Dynamic Ordinal Item Response Theory Model

To address this question, I develop an adaptation of the two-parameter item response theory (IRT) model designed specifically to measure changes in the level of ideological constraint and conflict extension in the US electorate. The two-parameter IRT model has become a popular alternative to factor analysis in studies of mass ideology over the last decade (see, for instance, Caughey and Warshaw Reference Caughey and Warshaw2015; Hill and Tausanovitch Reference Hill and Tausanovitch2015; Jessee Reference Jessee2012; Treier and Hillygus Reference Treier and Hillygus2009; Zhou Reference Zhou2019). IRT models have a long lineage in psychological and educational testing, where they are used to derive estimates of subjects' latent ability and information about the test items. Specifically, the two-parameter IRT model estimates two item-specific quantities: the difficulty parameter (which indicates the difficulty of the test item) and the discrimination parameter (which measures how well the test item distinguishes correct and incorrect answers on the basis of subjects' estimated ability).

The IRT model has been adapted in political science by substituting both ideology for ability and issue positions (measured through indicators such as roll-call votes and public opinion survey questions) for test items. For instance, an issue that is only weakly related to the ideological dimension would have a discrimination parameter with a low (absolute) value, while an issue that is closely connected to the ideological divide (for example, private versus government healthcare) would have a discrimination parameter with a high (absolute) value. The sign on the discrimination parameter simply indicates whether higher scores on the ideological dimension correspond to an increase or decrease in the probability of answering with an affirmative response (for example, a “yea” roll-call vote). Likewise, the difficulty parameter provides information about how conservative or liberal a respondent must be in order to be classified as supporting a given policy position. The ability parameter (which represents subjects' latent ability in the field being tested in traditional IRT modeling) indicates the estimated ideological position of each respondent.

The article adopts a Bayesian implementation of the two-parameter IRT model (Martin and Quinn Reference Martin and Quinn2002) based on the following considerations. First, the Bayesian framework offers a flexible approach to estimate latent quantities, especially when those quantities are dynamic. In our context, we wish to estimate survey respondents in a shared ideological space (which provides some degree of comparability between ideal points), but we also recognize that the mappings between issues and latent ideology evolve over time. The Bayesian implementation uses random-walk priors to facilitate estimation of the dynamic item parameters (that is, the mappings between issue attitudes and positions on the latent dimension). This hierarchical structure ensures that the issue mappings smoothly evolve over time, as estimates from the previous survey year serve as prior information that enters into the subsequent period. This strategy produces more efficient estimates of the item parameters than static methods (see, for example, Reuning, Kenwick, and Fariss Reference Reuning, Kenwick and Fariss2019, 508).

The Bayesian IRT model also allows uncertainty to propagate throughout the model. This uncertainty is automatically reflected in the posterior estimates, and the resulting uncertainty bounds are readily interpretable in terms of probabilities. Finally, this implementation accommodates the ordinal nature of most public opinion survey data (for example, Likert and issue scales).Footnote 5 Adding these components together gives us the Bayesian dynamic ordinal IRT (DO-IRT) model.Footnote 6

To more formally develop this model, let z ij represent the choice by respondent i (i = 1, …, n) on issue j(j = 1, …, p). Each issue j provides a total of C response categories (c = 1, …, C). In the standard two-parameter IRT setup, the latent response ![]() $z_{ij}^\ast $ is modeled using Equation 1. The item difficulty parameter (α jc) provides the C − 1 cut points between the response categories, while the item discrimination parameter (α jc) represents the loading of issue j onto the latent ideological dimension. The respondent ideal points are denoted by θ i, and β j is the item discrimination parameter. The error term, ɛ ij, is assumed to be normally distributed and the errors to be independent and identically distributed:

$z_{ij}^\ast $ is modeled using Equation 1. The item difficulty parameter (α jc) provides the C − 1 cut points between the response categories, while the item discrimination parameter (α jc) represents the loading of issue j onto the latent ideological dimension. The respondent ideal points are denoted by θ i, and β j is the item discrimination parameter. The error term, ɛ ij, is assumed to be normally distributed and the errors to be independent and identically distributed:

The probability of respondent i providing response c (c = 1, …, C) to issue j at time t is modeled using the standard normal cumulative distribution function, shown in Equations 2–4. As in standard ordered logit/probit, the cut points (α jc) are ordered consecutively:

and

To examine changes in the ideological structure of US public opinion over time, I add a dynamic component to this model. Specifically, I index the item parameters α j (the issue difficulty parameter) and β j (the issue discrimination parameter) by time t (t = 1, …, T). The respondent ideal points (θ i) are not indexed by t since no respondent participates in more than one survey. Hence, in this model, the probability of respondent i (i = 1, …, N) choosing response category c (c = 1, …, C) for item j (j = 1, …, q) is provided in Equations 5–7:

and

Indexing the item parameters by t allows for changes in the ways issues map onto the underlying ideological dimension over time. Changes in the discrimination parameter β jt, for instance, signal whether issues have become more or less strongly linked to the ideological dimension. In this model, normal priors are used for θ i, β jt, and α jct, with diffuse gamma priors placed on the precision terms of the time-varying item parameters.Footnote 7 At timet > 1, the priors for α jct and β jt are centered at the value of those parameters at t − 1. The use of “normal-walk priors” in dynamic spatial voting models is adopted from Martin and Quinn (Reference Martin and Quinn2002) and intuitively appealing: our best estimate of the value of α jct and β jt is its value at the previous time point. Permitting the meaning of the recovered ideological dimension to smoothly evolve places the model in line with path-breaking dynamic measurement methods in political science, such as Poole and Rosenthal's (Reference Poole and Rosenthal2007) DW-NOMINATE procedure and Martin and Quinn (Reference Martin and Quinn2002) scores of Supreme Court justice ideology. The approach here is simply to switch which parameters vary over time (those associated with the items rather than the legislator/voter ideal points).Footnote 8

In sum, the Bayesian DO-IRT model provides an appropriate measurement method to study changes in the meaning of the ideological dimension underlying voters' issue attitudes. Specifically, it accounts for the ordinal nature of survey responses, estimates uncertainty bounds for the latent variables, and allows the mappings between issues onto the ideological dimension to evolve across survey years.Footnote 9 The results from this model allow for a richer understanding of the nature of mass polarization in the US electorate in two ways. First, the discrimination parameters indicate the degree to which citizens' policy attitudes fit a unidimensional ideological structure. This provides information about the number and types of policy disputes encompassed by a single dimension of ideological conflict. Secondly, a dynamic measurement model produces ideological scores for survey respondents that are more directly comparable over this period because it does not assume that the issue mappings are static. Policy controversies can become more or less ideological over time, while shifts in public opinion on other issues (for example, LGBTQ rights) mean that a “liberal” response to a particular survey item in 2016 might indicate something quite different than the same response given in 1988. I empirically demonstrate this in the following.

The Growth in Mass Ideological Constraint, 1980–2016

In this section, I test the theory of conflict extension in the mass electorate by assessing changes in the level of unidimensional ideological constraint in voters' policy attitudes over the last forty years. Specifically, I examine the loading of fifteen political issues onto a single latent ideological dimension among respondents from the 1980 through 2016 ANES. These issues include: traditional New Deal economic and social welfare policies; more postmaterialist concerns, such as environmental protection; social/cultural controversies involving abortion, LGBTQ rights, and gun control; and issues that tap into racial attitudes, such as aid to black people and immigration.Footnote 10 I delete respondents who provide responses to less than three survey items, leaving 24,059 respondents in the analysis.Footnote 11

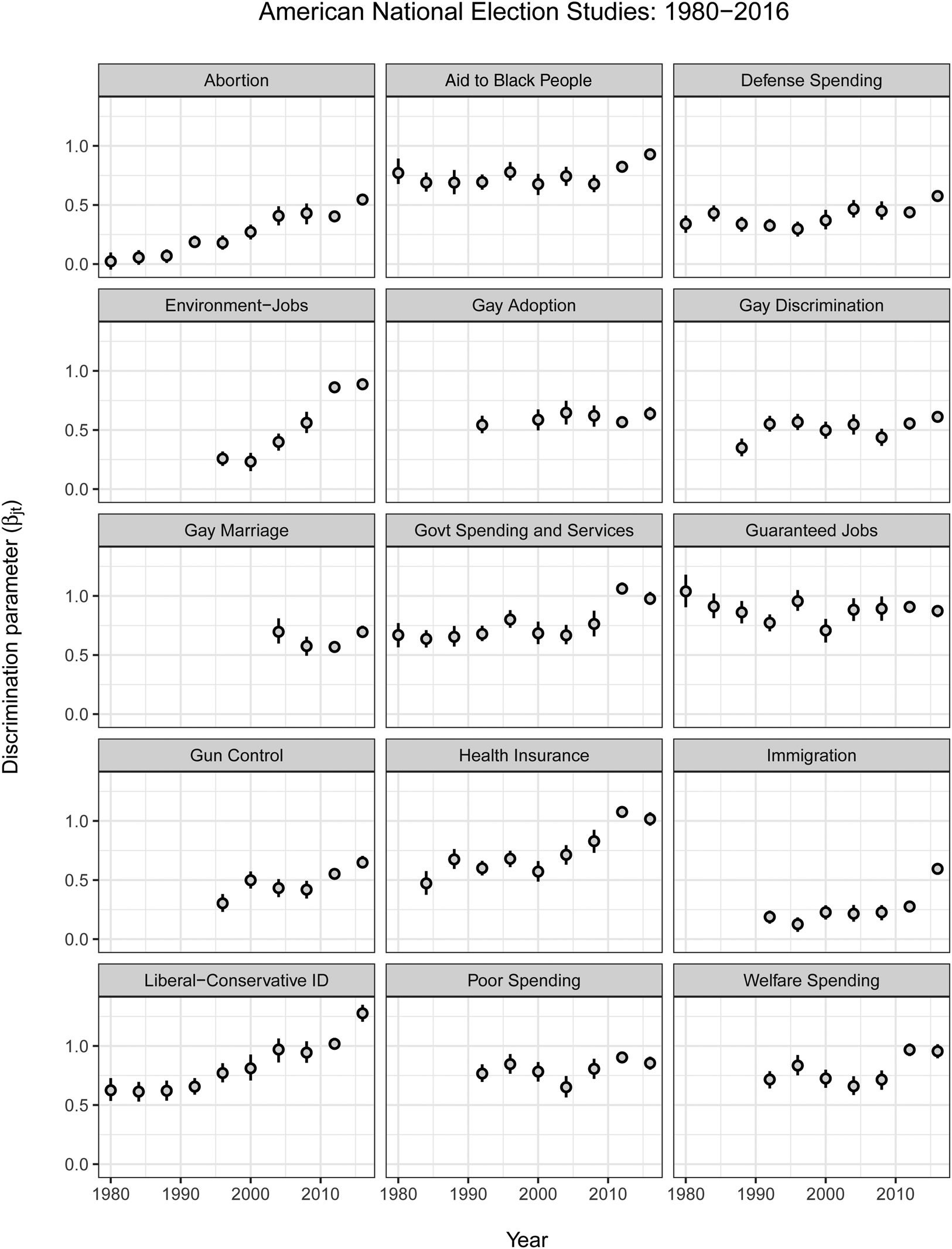

I begin by analyzing the issue discrimination parameters over the period between 1980 and 2016. Figure 1 plots the means and 95 per cent credible intervals of the posterior distributions of the discrimination parameters for each of the fifteen issues. Recall that larger discrimination parameters indicate that the issue loads more strongly onto the latent dimension.Footnote 12

Figure 1. Issue discrimination parameters (β jt) from the Bayesian DO-IRT model.

Note: Bars show 95 per cent credible intervals.

Source: 1980–2016 ANES.

Consistent with the theory of conflict extension, none of the fifteen issues have become less attached to the underlying ideological dimension during this period. Quite the opposite, we see meaningful increases in the discrimination parameters of the abortion, environment–jobs trade-off, gun control, government–private health insurance, immigration, and liberal–conservative identification items. The growth in constraint on issues such as abortion, environmental protection, and health insurance are particularly striking. Abortion attitudes are now about as ideologically constrained as attitudes on defense spending, while environmental protection and health insurance have discrimination parameters on a par with the traditional social welfare issue scales of guaranteed jobs and government spending and services. Moreover, Figure 1 shows that ideological self-identifications have become a considerably better indicator of respondents' operational policy preferences since 1980.

Figure 1 provides scant evidence that newer social/cultural policy conflicts are displacing long-standing disagreements over economic and social welfare issues. While the latent dimension has increasingly absorbed such social/cultural issues as abortion and gun control, the discrimination parameters of economic/social welfare items (that is, government spending and services, guaranteed jobs and income, government–private health insurance, federal spending on the poor, and federal spending on welfare) have all remained stable or increased over this period. Of these, health insurance attitudes have seen the most dramatic increase in constraint (with much—though not all—of this change occurring between 2008 and 2012).Footnote 13 To the extent that the government aid to black people item taps into economic preferences, the stability of its discrimination parameter since 1980 also speaks to the continued relevance of economic issues in defining ideological conflict.

Although the discrimination parameters of three items relating to LGBTQ rights (adoption, job discrimination, and same-sex marriage) do not exhibit a marked increase over this period, citizens' attitudes on these issues already fit within a unidimensional ideological structure since their introduction in the ANES. At the same time, attitudes on abortion—which throughout the 1980s had a discrimination parameter of virtually 0—have become increasingly constrained by the ideological dimension over this period. Consequently, cultural and moral conflict in US society is well manifested in the contemporary ideological divide. Far from being relegated to a secondary dimension, Americans' social/cultural attitudes are an increasingly important component of the ideological fabric of US public opinion. Since liberal–conservative identification also taps into citizens' broad social/cultural postures (Conover and Feldman Reference Conover and Feldman1981; Stimson Reference Stimson2015), the increase of its discrimination parameter is consistent with this claim.

It is also noteworthy that respondents' immigration attitudes (that is, their desired level of immigration) become more ideologically constrained between 2012 and 2016. Immigration provides a recent example of a deeply symbolic, “easy” issue that became salient and clearly differentiated the parties in the 2016 presidential election (Reny, Collingwood, and Valenzuela Reference Reny, Collingwood and Valenzuela2019; Sides, Tesler, and Vavreck Reference Sides, Tesler and Vavreck2019). During this span, its discrimination parameter increases from minimal to modest, placing it in line with social/cultural controversies such as abortion, gun control, and LGBTQ rights. Moreover, as with other issues, the results show that immigration has supplemented rather than replaced other policy disputes on the ideological conflict dimension.

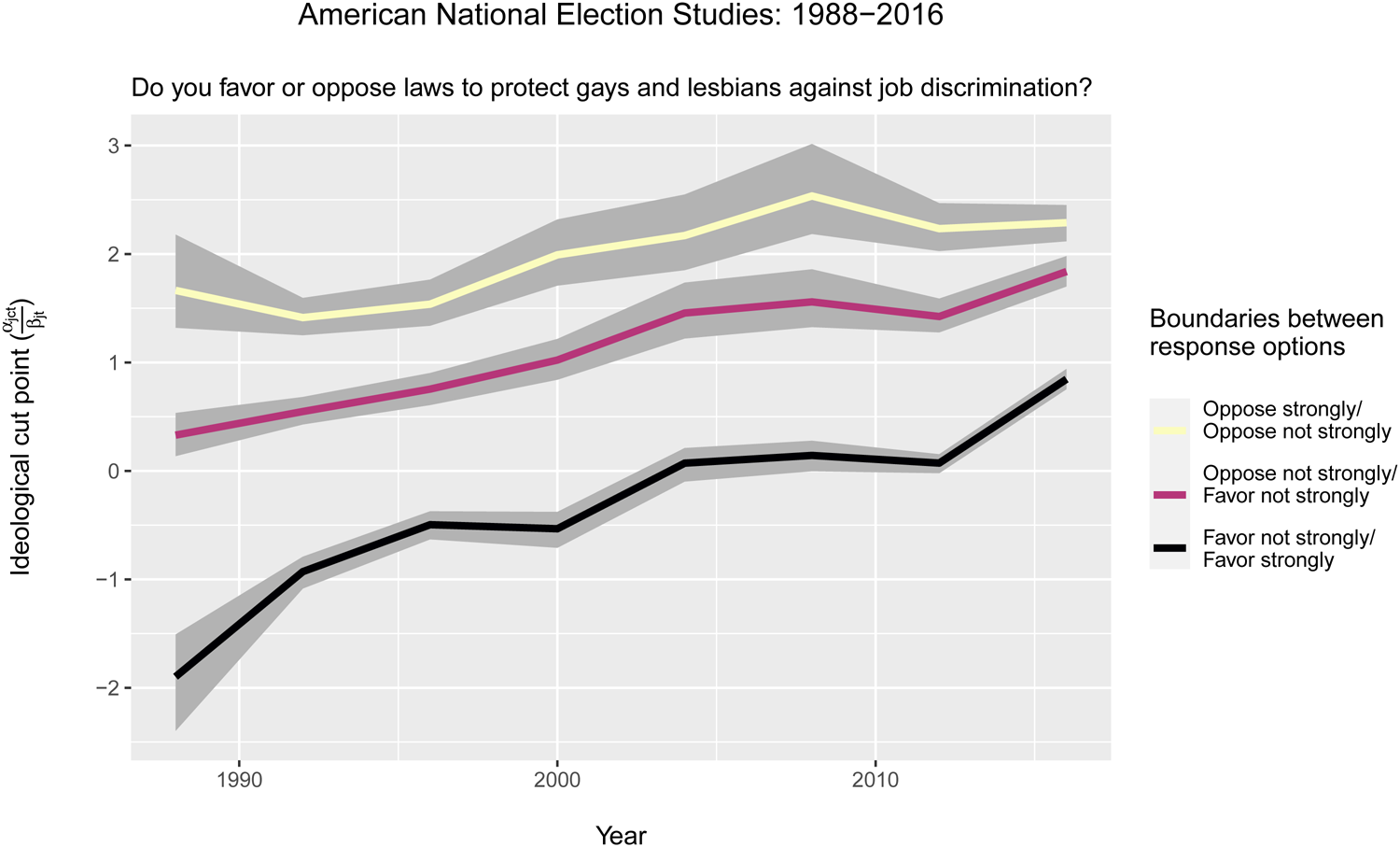

Finally, in addition to tracking how issue loadings evolve over time, the DO-IRT model also captures changes in the way issues divide the ideological continuum via the item difficulty parameters. These parameters represent how liberal or conservative a respondent must be to have a predicted response on a given issue, and hence shifts in what constitutes a “liberal” or “conservative” response over this period. LGBTQ rights offers a prime example of such an issue where public opinion has shifted dramatically between 1988 (when relevant questions were first introduced in the ANES) and 2016. Figure 2 shows the estimated cut points between response options for one such item concerning laws to protect gays and lesbians from job discrimination.Footnote 14 The results show that a respondent in 1988 would need to be on the far-left end of the ideological dimension (with an ideal point less than −2) to be modeled as answering that they “strongly” favor such laws. The thresholds track steadily rightward in the space, such that by 2016, all ideologically centrist and many conservative respondents are predicted to favor (either “strongly” or “not strongly”) laws against gay and lesbian job discrimination. Of course, this has also been the case for political candidates and legislators, hence the need for dynamic ideal-point models. Simply put, responses to survey items like these mean different things at different times, and the changing meanings of specific policy positions appear to be identified by the DO-IRT model.

Figure 2. Cut points for gay discrimination from the Bayesian DO-IRT model.

Note: Shade regions show 95 per cent credible intervals.

Source: 1988–2016 ANES.

Differences in Constraint by Level of Political Sophistication

The results outlined earlier showed evidence of increased ideological constraint in the US electorate as a whole, but how do these trends vary among subsets of survey respondents? In particular, to what extent have changes in ideological constraint been conditioned by political sophistication? In this section, I modify the DO-IRT model to allow for random effects in the difficulty (α jct) and discrimination (β jt) parameters between three levels of political sophistication. The coding scheme for political sophistication is adopted from Lupton, Myers, and Thornton (Reference Lupton, Myers and Thornton2015): three indicators (self-reported interest in the campaign, participation in campaign activities, and interviewer assessment of respondent knowledge) are standardized and the mean is used as the sophistication score.Footnote 15 Respondents are then divided into three sophistication tertiles (low, medium, and high) by year based on their score.

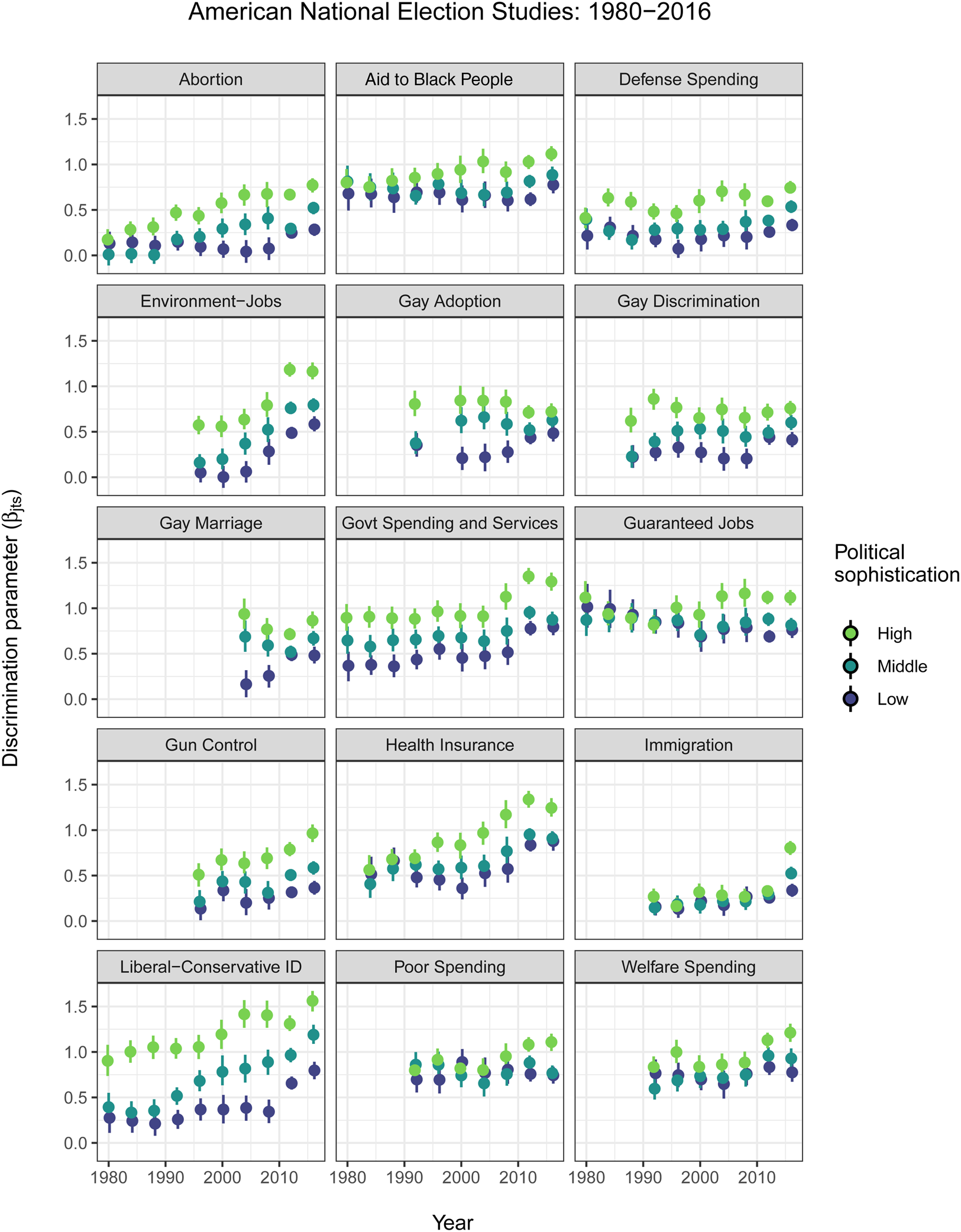

Figure 3 tracks changes in the issue discrimination parameters of ANES respondents by level of political sophistication. As in Figure 1, higher values indicate a stronger relationship between the issue and the latent ideological dimension. Not surprisingly, Figure 3 shows that attitudinal constraint across issues is generally higher among more politically sophisticated respondents. However, on most issues, all of the political sophistication groups see meaningful increases in their discrimination parameters over this period. On policy items as varied as abortion, environment–jobs, and health insurance, the ANES 2016 respondents with low levels of political sophistication exhibit levels of ideological constraint on a par with their highly sophisticated counterparts in the 1980s and 1990s. The effects of conflict extension do not appear to be confined to the most politically engaged voters, but rather cut across the electorate and reach even citizens who have minimal interaction with the political system.

Figure 3. Issue discrimination parameters (β jts) from the Bayesian DO-IRT model by level of political sophistication.

Note: Bars show 95 per cent credible intervals.

Source: 1980–2016 ANES.

To be certain, there remains a clear gradation in the level of attitudinal constraint exhibited by high-, middle-, and low-sophistication voters. On the issue of immigration, for instance, the discrimination parameter for the least politically sophisticated respondents remained low through the 2016 election, while the discrimination parameters for moderately and (especially) highly sophisticated respondents spiked. It seems reasonable to suspect that the influence of changes in the political environment on attitudinal constraint simply take longer to make their way to the least attentive voters, though future work should investigate this conjecture.

Nonetheless, the results presented in this section substantiate a long-theorized benefit of polarization: voters—even relatively disconnected voters—are adopting better-structured political preferences in line with the ideologically constrained choice set presented to them (see, for example, American Political Science Association, 1950). Elite polarization has compelled partisan-ideological sorting among voters across levels of political sophistication by clarifying policy differences between the parties (Levendusky Reference Levendusky2010; Zingher and Flynn Reference Zingher and Flynn2019). My findings suggest that it has also fostered somewhat greater unidimensional ideological constraint among voters classified at low, medium, and high levels of political sophistication. Recognition of partisan differences on policy matters appears to be the most important specific mechanism driving sorting, and awareness of these distinctions has steadily increased across the electorate since the 1980s (Freeder, Lenz, and Turney Reference Freeder, Lenz and Turney2019; Sniderman Reference Sniderman2017).Footnote 16 Indeed, when reproducing Figure 3 by instead dividing respondents based on correct/incorrect ideological placement of the parties, the results (provided in the supplementary materials, available online) show that the growth in mass ideological constraint has been nearly entirely concentrated among citizens who are able to correctly identify the relative ideological positions of the two major parties. Elite polarization has placed this task within the reach of less politically sophisticated voters.

The Sources of Increased Ideological Constraint

The previous analysis documented how mass attitudes on a wide array of policy issues have become increasingly structured along a single latent ideological dimension over the last forty years. In this section, I examine the sources of the growth of unidimensional ideological constraint over this period. In particular, I assess the extent to which the left–right dimension has incorporated core values and party identification alongside voters' policy preferences.

Past work—especially the literature on sorting in the mass electorate—shows that the linkages between ideology, partisanship, and vote choice have grown stronger over recent decades (Bafumi and Shapiro Reference Bafumi and Shapiro2009; Baldassarri and Gelman Reference Baldassarri and Gelman2008; Levendusky Reference Levendusky2009).Footnote 17 Less clear—but no less consequential—is how the relationship between core value dispositions and political attitude structures has evolved in a polarized political environment. It is well established that core values influence attitudes on specific political issues and divide partisans in the contemporary mass electorate (Goren Reference Goren2013; Jacoby Reference Jacoby2014), but are citizens' basic value dispositions related to changes in the ideological structure of US public opinion? The theory of conflict extension leads to the expectation that the latent ideological dimension I measure in this article has increasingly encompassed core values and beliefs relating to economic and social policies over the last forty years. Stated otherwise, basic value postures toward both economic and social behavior should be increasingly connected to the primary dimension structuring competition in contemporary US politics.

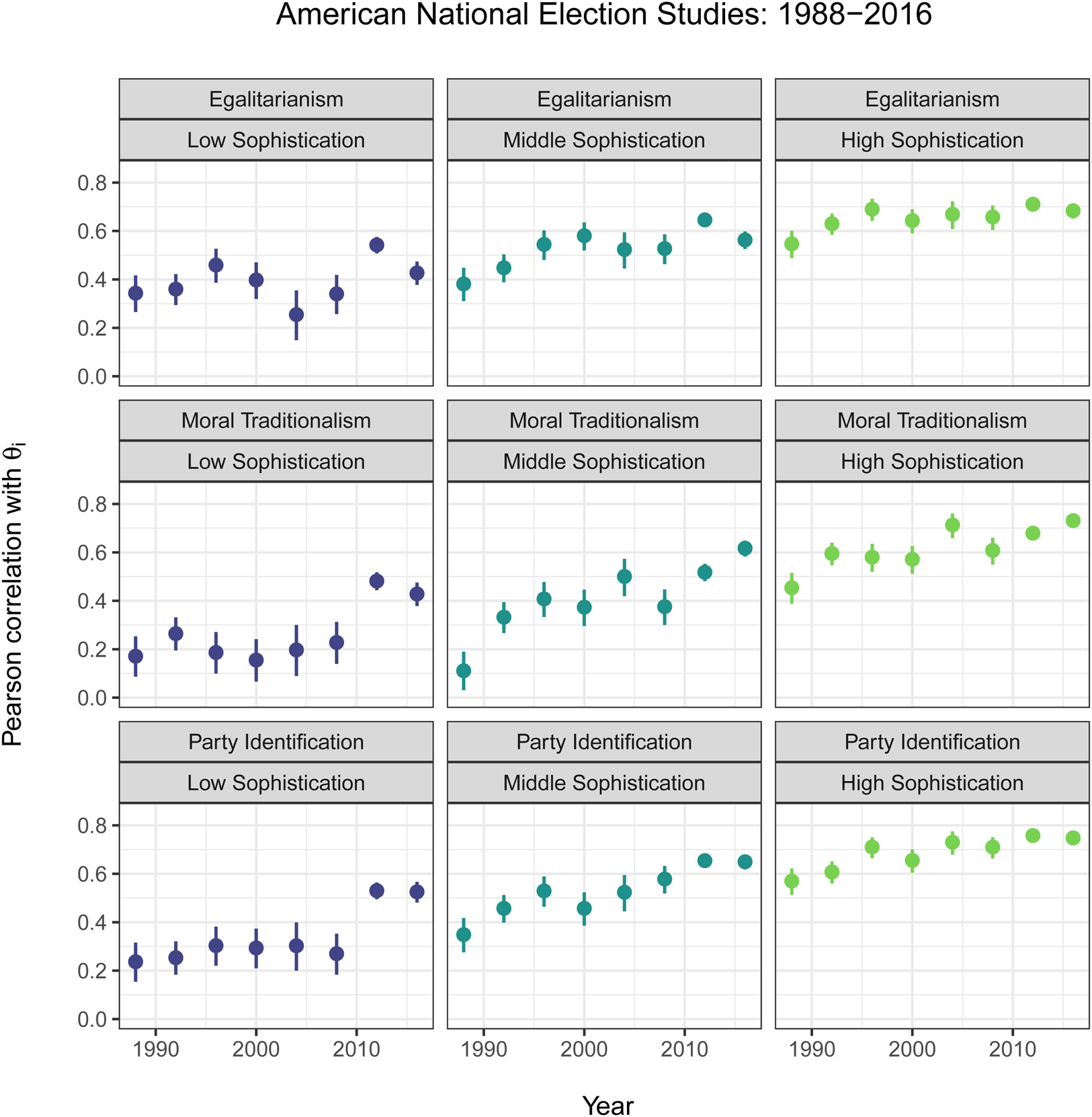

I first consider this relationship by shifting to the other set of parameters estimated by the DO-IRT model: the respondent ideal points (θ i) on the recovered ideological dimension. Figure 4 shows the over-time simple Pearson correlations between ANES respondents' ideological ideal points and three fundamental political dispositions: party identification, economic egalitarianism, and moral traditionalism.Footnote 18 As before, I consider respondents with low, medium, and high levels of political sophistication separately.

Figure 4. Correlations between respondent ideal-point estimates (θ i) and core values and partisanship by level of political sophistication.

Note: Bars show 95 per cent credible intervals.

Source: 1988–2016 ANES.

The results closely parallel those from the previous section, which examined changes in ideological constraint by level of political sophistication. In particular, Figure 4 reveals that more politically sophisticated respondents possess more meaningful unidimensional attitude structures, in this case, holding ideological positions that are more tightly connected to partisanship and both core values. Among highly politically sophisticated respondents, correlations generally range between 0.5 and 0.7 on the egalitarianism and moral traditionalism scales, and between 0.6 and 0.8 on party identification.

However, voters' ideological, partisan, and value dispositions have become more tightly interwoven among all three political sophistication groups. Moderately politically sophisticated respondents have seen the largest increases in the correlations between their ideal points and each of these dispositions, especially on the moral traditionalism index (rising from r = 0:18 in 1988 to r = 0:65 in 2016). Indeed, by the end of this series, the correlations among moderate-sophistication respondents only slightly lag those of their highly sophisticated counterparts. Moreover, as in the previous section, low-sophistication respondents in the 2010s closely resemble high-sophistication respondents during the 1980s.

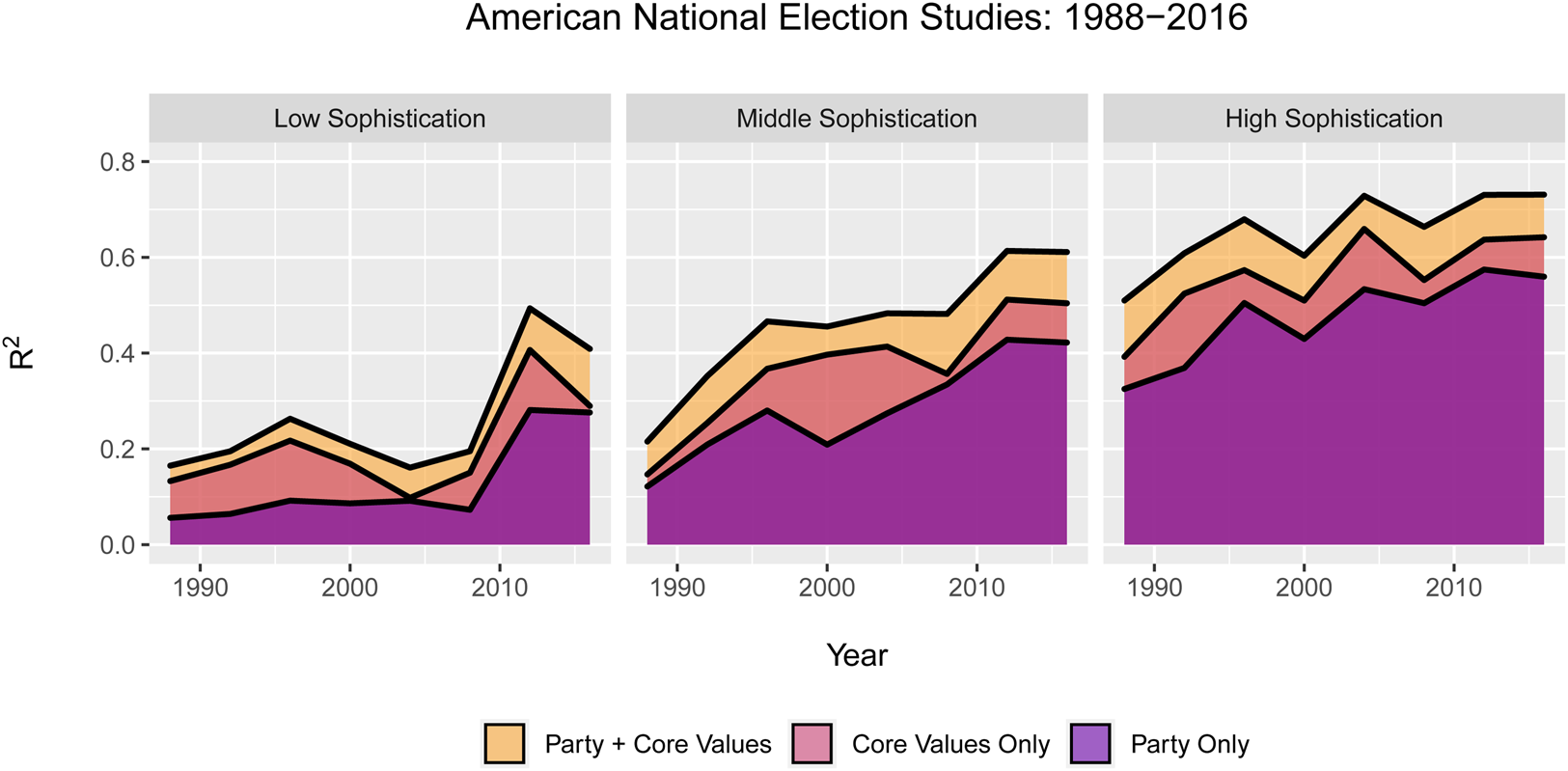

Collectively, the egalitarianism and moral traditionalism value dispositions explain a slightly larger proportion of the variance in voters' ideological positions than party identification across years and political sophistication levels. Figure 5 demonstrates this by plotting R 2 values from linear regressions of the respondent ideal-point estimates (θ i) on different combinations of the value and partisan dispositions.Footnote 19 In all cases, the core values model provides greater explanatory power than the party identification model, though the combined model (party + core values) outperforms both. The results indicate that the growth in mass ideological constraint is not simply a product of partisan-ideological sorting; rather, core values have also come to increasingly explain voters' left–right positions. By 2016, the combined model achieves R 2 values of 0.41, 0.61, and 0.73 for low-, medium-, and high-sophistication respondents, respectively.Footnote 20

Figure 5. Fit of regression models of respondent ideal-point estimates (θ i) on combinations of core values and partisanship by level of political sophistication.

Note: Core values include egalitarianism and moral traditionalism indices.

Source: 1988–2016 ANES.

Taken together, Figures 4 and 5 indicate that conflict extension in the mass electorate has not been confined to specific issue attitudes, but also encompasses core values and party identification. Consistent with the results presented in the previous section, social values (that is, moral traditionalism) have supplemented rather than displaced economic values as a correlate of mass ideology over the last forty years. Indeed, economic egalitarianism has become more strongly related to ideology during this period. These results suggest that voters have not engaged in blind sorting over recent decades, but are adopting ideological positions increasingly in line with core values and partisan dispositions. As with the changes in the issue loadings documented in the previous section, the growing influence of values and party identification on ideology have occurred among voters across levels of political sophistication.

Consequently, in the contemporary US electorate, ideology has come to reflect divisions over both economic and social matters. However, it is important to emphasize that ideological divides not only encompass specific economic and social policy controversies, but also run deeper to fundamental value cleavages over private and public morality, as well as the extent to which society should promote economic equality. The results are consonant with Jacoby's (Reference Jacoby2014, 24) assertion that, “In the past, values were regarded as an alternative to ideology, providing organizational parsimony for political attitudes among people who did not conceptualize the world in abstract terms (Feldman Reference Feldman1988). In contrast, the present findings suggest that value orientations actually reinforce ideological distinctions.” On this front too, polarization has served to shrink the gap between politically active citizens and the remainder of the electorate (especially between moderately and highly sophisticated citizens) (Levendusky Reference Levendusky2009, Levendusky Reference Levendusky2010; Zingher and Flynn Reference Zingher and Flynn2019). The results suggest that both partisanship and core values serve as gateways to ideological reasoning for voters at all levels of political sophistication.

Discussion

One of the curious things about political opinions is how often the same people line up on opposite sides of different issues. The issues themselves may have no intrinsic connection with each other…. Yet the same familiar faces can be found glaring at each other from opposite sides of the political fence, again and again…. A closer look at the arguments on both sides often shows that they are reasoning from fundamentally different premises. These different premises—often implicit—are what provide the consistency behind repeated opposition of individuals and groups on numerous, unrelated issues. (Sowell Reference Sowell2007, 3)

This article offers separate methodological and substantive contributions to the study of ideological constraint in the US electorate. The development of a Bayesian DO-IRT model with time-varying item parameters offers a method to measure mass ideology that accounts for changes in public opinion over time. Substantively, the application of this model to public opinion survey data collected over the last forty years provides considerable evidence substantiating the existence of mass conflict extension (Layman and Carsey Reference Layman and Carsey2002a, Layman and Carsey Reference Layman and Carsey2002b). Indeed, the results show that much of the conflict extension literature understates the degree to which citizens' policy attitudes have collapsed onto a single ideological dimension. Mass ideology is not strictly unidimensional, but the two main dimensions (economic and social/cultural) have become increasingly intertwined over the past forty years (see also Stoetzer and Zittlau Reference Stoetzer and Zittlau2020). The largest growth in unidimensional constraint has occurred among respondents with low and moderate levels of political sophistication, somewhat narrowing the knowledge gap in ideological thinking.

Combustible social/cultural issues that speak to moral and religious divides have been increasingly folded into already-contentious divides over economic and social welfare policies, but this has not been the only important change to the ideological structure of US public opinion. Fundamental cleavages involving values like economic egalitarianism and moral traditionalism have also been absorbed into the same dimension. The primary ideological dimension underlying political attitudes increasingly reflects both policy and value divisions on both economic and social/cultural matters. This is an important but often overlooked aspect of political polarization: the meaning of the ideological dimension and the structure of political competition—what partisans are fighting about—surely shapes the nature of ideological and partisan conflict in US politics. These results indicate that polarization in the US electorate has increased in two respects: existing policy and value cleavages have calcified; and more conflicts have been absorbed into the ideological dimension.

Normatively, these findings are something of a mixed bag. On the one hand, democratic theorists and political scientists alike have long bemoaned the lack of structure in voters' policy attitudes and choice, stemming in large part from Converse's (Reference Converse and Apter1964) landmark essay. After all, there is widespread agreement that US political elites operate in unidimensional ideological space (see, for example, Bonica Reference Bonica2014; Poole and Rosenthal Reference Poole and Rosenthal2007). That voters'—especially less politically sophisticated voters'—attitudes are better mapped onto this same space means that they are also better equipped to connect their policy preferences to such political behaviors as party identification and vote choice (see also Levendusky Reference Levendusky2010).

At the same time, the presence of reinforcing cleavages in US public opinion presents potential dangers for the health of a pluralistic democracy, with the same groups continually engaging in multiple (and often emotional) policy and value conflicts. It seems only natural that partisans would like each other less, view the other side as illegitimate, and be less amenable to compromise (Davis Reference Davis2019; DellaPosta Reference DellaPostaforthcoming; Iyengar and Westwood Reference Iyengar and Westwood2015; Mason Reference Mason2018). Future work should (and undoubtedly will) continue to sort out the feedback processes between the policy and affective components of political polarization, as well as explore the consequences of conflict extension on more extreme varieties of affective polarization, such as political dehumanization and the rejection of democratic norms.

Changes in the structure and content of voters' ideological divisions are an essential feature of partisan conflict in contemporary US politics. In particular, the US political system has long relied on citizens who are less passionate about politics to rein in ideological conflict (Fiorina, Abrams, and Pope Reference Fiorina, Abrams and Pope2011). That this group has also experienced substantial growth in ideological constraint impedes an important obstacle to deeper polarization.

Supplementary Material

Online appendices are available at: https://doi.org/10.1017/S000712342100051X

Data Availability Statement

Replication data for this article can be found in Harvard Dataverse at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/ZURHQA

Acknowledgments

I thank Jim Adams, Ben Highton, Adrienne Hosek, Bill Jacoby, Brad Jones, Jeff Lewis, Bob Lupton, Keith Poole, Howard Rosenthal, and four anonymous reviewers for their helpful feedback and comments.

Financial Support

None

Competing Interests

None