VALUE OF ISLANDS FOR INSIGHTS INTO ECOLOGY AND EVOLUTIONARY BIOLOGY

Islands are widely considered to be model systems for studying fundamental questions in ecology and evolutionary biology (MacArthur & Wilson Reference MacArthur and Wilson1967; Vitousek Reference Vitousek2004; Grant & Grant Reference Grant and Grant2011). The study of islands has inspired a multitude of core theories in ecology and evolutionary biology (Warren et al. Reference Warren, Simberloff, Ricklefs, Aguilée, Condamine, Gravel, Morlon, Mouquet, Rosindell, Casquet, Conti, Cornuault, Fernández-Palacios, Hengl, Norder, Rijsdijk, Sanmartín, Strasberg, Triantis, Valente, Whittaker, Gillespie, Emerson and Thébaud2015). Arguably the most pivotal is that of Darwin who, through observation of tanagers on the Galápagos, famously theorized the role of natural selection and specialization to different diets to account for the observed diversity in beak morphology (Darwin Reference Darwin1859).

Islands have also played a role in the birth of historical biogeography. Wallace (Reference Wallace1880), through his extensive fieldwork in the Indo-Pacific, discovered and characterized faunal affinities along distinct western (Asian origin) and eastern (Australian origin) lines, providing enduring insight into the role of historical and geological factors in driving species distributions (Holt et al. Reference Holt, Lessard, Borregaard, Fritz, Araújo, Dimitrov, Fabre, Graham, Graves and Jønsson2013). Likewise, islands have provided insights into the biogeographical imprint of extremely distant events in the Earth's history, connected with the plate-tectonic processes that have seen the break-up of super-continents, as well as the relative role of vicariance and dispersal in colonization history (Rosen Reference Rosen1975).

Islands have also played an instrumental role in the development of several fundamental theories in ecology. They are a key element in one of the most robust generalizations in ecology – the species–area relationship (Arrhenius Reference Arrhenius1921; Preston Reference Preston1960) – which has been used extensively to predict the magnitude of species extinction from habitat loss (e.g. Thomas et al. Reference Thomas, Cameron, Green, Bakkenes, Beaumont, Collingham, Erasmus, De Siqueira, Grainger and Hannah2004). MacArthur and Wilson's equilibrium theory of island biogeography (MacArthur & Wilson Reference MacArthur and Wilson1967) suggested that the species–area relationship manifested from a dynamic equilibrium between immigration and extinction, and that this dynamic was in turn influenced by the effect of isolation and island area on immigration and extinction rates. Diamond (Reference Diamond, Diamond and Cody1975) also used islands to argue that competitive interactions between species could explain non-random patterns of species co-occurrence in communities, arguing for the importance of biotic interactions in shaping local community structures. Associated rules of ‘forbidden species combinations’ and ‘reduced niche overlap’ have sparked more recent debate regarding the formation of appropriate null models (Gotelli & McCabe Reference Gotelli and McCabe2002; Chase & Myers Reference Chase and Myers2011). Likewise, the concept of community nestedness in which the species composition of small assemblages is a subset of larger assemblages drew upon data from islands (Darlington Reference Darlington1957).

Islands have also been important in the development of insights at the interface between ecology and evolution. Thus, the idea of the ‘taxon cycle’ (Wilson Reference Wilson1961), developed with studies of undisturbed island ant faunas in the Moluccas–Melanesian arc, argued that predictable ecological and evolutionary changes proceeded through iterative range expansion and colonization followed by evolutionary specialization within island populations. Ultimately, taxa either went extinct or progressed through a new phase of range expansion, thus renewing the cycle (Wilson Reference Wilson1961). Thus, over the last century, ecological and evolutionary research focusing on multiple facets of islands – from the colonization of species and the development of uniquely evolved biotas, to the predictability of ecosystem development and community assembly over space and time – has shaped our fundamental vision of both pattern and process in ecology and evolutionary biology.

Considering the centrality of islands to fundamental development of these disciplines, we ask: what are the properties of insular systems that make them exceptional, and how are these hallmarks at risk in the Anthropocene? In the following sections, our objectives are threefold: (1) to consider the biological properties of insular systems in order to show how an island-based conceptual framework is usefully applied to situational derivatives of ‘true islands’ formed de novo (e.g. oceanic islands, caves and salt lakes) or by fragmentation (e.g. sky islands and kīpuka); (2) to review how predictions from theory and extensive empirical study can provide solutions to anthropogenic problems facing all island systems; and (3) to summarize a few important consequences of anthropogenic change on islands, but also to highlight where scientific inquiry, at the most fundamental level of exploration of alpha-diversity, is providing a way to catalogue the changing world. Our review of human impacts is necessarily superficial, designed to categorize rather than provide a comprehensive overview. Moreover, specific examples are drawn primarily from the literature on oceanic islands, with which we are most familiar. Our intention is to stimulate broad discourse on the value of, and future challenges to, island environments that have generated so many seminal insights in the fields of ecology and evolution.

BIOLOGICAL PROPERTIES OF INSULAR SYSTEMS

Island characteristics

From a biological perspective, an insular habitat can be defined as any discrete habitat that is isolated from other similar habitats by a surrounding inhospitable matrix (Gillespie & Clague Reference Gillespie and Clague2009). Both the habitat and the isolating matrix are relative to the organism in question. Water bodies present a stark barrier for terrestrial lineages on islands; in the same way, intervening land around water bodies creates a barrier for aquatic organisms (Gillespie & Roderick Reference Gillespie and Roderick2002). Patches of habitat (e.g. characterized by vegetation, soil and/or microclimate) separated by areas of unsuitable terrain are also essentially isolated for species of narrow environmental tolerance. Islands may thus include sky islands, whale falls in the ocean, lakes within a land mass and forest fragments in a matrix of secondary growth, pasture lands or anthropogenic development. Because a greater understanding of the spectrum of island attributes will allow us to compare and contrast the processes playing out on them, we next review four primary attributes that dictate the biological properties of any given insular system: formation history, time, area, and isolation.

Formation history

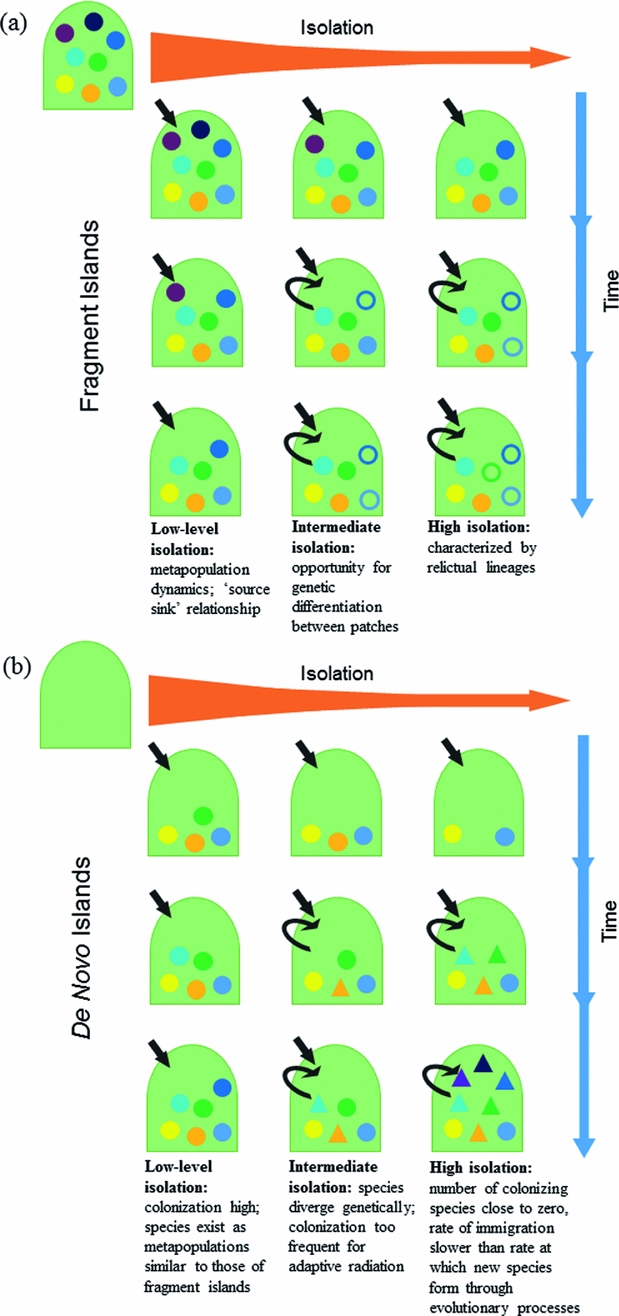

It was the view of Darwin (Reference Darwin1859) that biota on de novo islands were a product of colonization from continents followed by in situ evolutionary change. In contrast, Wallace (Reference Wallace1880) studied islands in Indonesia, which were fragments of continents, and so his ideas revolved around the faunal affinities of islands relative to their source pools. Insular systems that are formed de novo can only gain species initially by colonization, and the biota grows through colonization or speciation (Warren et al. Reference Warren, Simberloff, Ricklefs, Aguilée, Condamine, Gravel, Morlon, Mouquet, Rosindell, Casquet, Conti, Cornuault, Fernández-Palacios, Hengl, Norder, Rijsdijk, Sanmartín, Strasberg, Triantis, Valente, Whittaker, Gillespie, Emerson and Thébaud2015). Thus, it is an island's degree of isolation that dictates how much subsequent species accumulation will be a consequence of in situ diversification (neo-endemics) (MacArthur & Wilson Reference MacArthur and Wilson1967; Lomolino Reference Lomolino2000; Rosindell & Phillimore Reference Rosindell and Phillimore2011). In contrast, insular fragments created by submergence or changes in climate of surrounding areas are formed with a full biotic complement, and lose species during their formation through relaxation (Wilcox Reference Wilcox1978; Terborgh et al. Reference Terborgh, Lopez, Nunez, Rao, Shahabuddin, Orihuela, Riveros, Ascanio, Adler and Lambert2001). Given a long period of time on fragment islands, distinct species may form (paleo-endemics). Thus, the history of island formation is key to the biological characteristics of a given insular community (Fig. 1).

Figure 1 Evolutionary assembly of de novo and fragment islands at varying levels of time and isolation. Differently shaded shapes represent species as they accumulate through colonization and through the formation of new species by both processes of anagenesis and cladogenesis. Black arrows indicate whether species are primarily accumulated by colonization (incoming arrow) or genetic divergence (arching arrow). (a) Fragment islands begin with biota similar to source. The number of species will decrease over ecological time as a result of relaxation and simply because of reduced area. Over evolutionary time, species diverge from original stock through anagenesis (unfilled circles), with the formation of paleo-endemics. (b) De novo islands are formed without life, thus the ecological space is open and available when they first appear. Over time, species increase through both colonization and the formation of new species by cladogenesis (triangles). At high isolation, multiple neo-endemics may form through adaptive radiation.

Time

In general, older islands have more species when the effects of formation history, area and latitude are removed (Wilcox Reference Wilcox1978). Time can make up for isolation by allowing for more time for immigration and/or speciation on de novo islands (Willis Reference Willis1922; Borges & Brown Reference Borges and Brown1999; Gruner Reference Gruner2007). On fragment islands, the primary effect of time is greater paleo-endemism (Gillespie & Roderick Reference Gillespie and Roderick2002).

Area

Species richness has long been recognized to scale as a log-linear function of area (Arrhenius Reference Arrhenius1921; Rosenzweig Reference Rosenzweig1995). One of MacArthur and Wilson's (Reference MacArthur and Wilson1967) key insights was that larger areas have the potential to support larger populations of species, thereby reducing extinction rates from demographic stochasticity and thus leading to greater species richness. Larger populations also lead to greater standing genetic diversity, which may enhance rates of evolutionary change (Frankham Reference Frankham1996). Area is also broadly correlated with other aspects of the landscape that promote speciation, including habitat diversity and heterogeneity and the potential for allopatric barriers (Losos & Parent Reference Losos, Parent, Losos and Ricklefs2009).

Isolation

De novo islands close to a source of migrants are expected to reach an equilibrium species diversity with continuous turnover (MacArthur & Wilson Reference MacArthur and Wilson1967). Increasing isolation leads to speciation playing a larger role in species accumulation, with anagenesis giving way to cladogenesis (Rosindell & Phillimore Reference Rosindell and Phillimore2011) and adaptive radiation on the most remote islands (Gillespie & Roderick Reference Gillespie and Roderick2002). Fragment islands are generally less isolated than oceanic islands. However, those that are very isolated for extended periods can also serve as a background for adaptive radiation, presumably facilitated by fluctuations in land area and climate opening ecological opportunities for new colonists (Yoder et al. Reference Yoder, Campbell, Blanco, dos Reis, Ganzhorn, Goodman, Hunnicutt, Larsen, Kappeler and Rasoloarison2016).

Island dynamics

The formation history, time, area and isolation are not static. Geologic and climatic processes are dynamic: islands are formed, and area and isolation may change over time through cycles of fusion and fission of land masses (Price & Elliott-Fisk Reference Price and Elliott-Fisk2004). The relative temporal scales of these processes will determine the interplay of area and isolation, which in turn will influence the biological properties of insular environments (Gillespie et al. Reference Gillespie, Rominger, Lim, Scheiner and Mindell2017). For example, the relative abundance of different habitats on geologically ancient islands such as Madagascar has varied through time due to climatic oscillations, giving rise to a biota with both paleo-endemic and neo-endemic elements (Yoder et al. Reference Yoder, Campbell, Blanco, dos Reis, Ganzhorn, Goodman, Hunnicutt, Larsen, Kappeler and Rasoloarison2016).

Over shorter timescales, the geologic life cycle of oceanic ‘hotspot’ islands, from subaerial emergence to their eventual erosional demise, strongly affect the tempo of evolutionary radiation and decline on islands (Borregaard et al. Reference Borregaard, Amorim, Borges, Cabral, Fernández-Palacios, Field, Heaney, Kreft, Matthews, Olesen, Price, Rigal, Steinbauer, Triantis, Valente, Weigelt and Whittaker2017). The sequential formation of the Hawaiian archipelago has played host to multiple rapid species radiations that slowed with increasing age and declining island area (Lim & Marshall Reference Lim and Marshall2017). In hotspot archipelagos with defined geological ‘life cycles’ (Whittaker et al. Reference Whittaker, Triantis and Ladle2008; Lim & Marshall Reference Lim and Marshall2017), there tends to be a progression of lineages colonizing from older to younger islands (Wagner & Funk Reference Wagner and Funk1995; Shaw & Gillespie Reference Shaw and Gillespie2016), and the composition of the biota shifts over geological time from primarily colonizing species on the youngest islands to those dominated by endemic species arising in situ (Rominger et al. Reference Rominger, Goodman, Lim, Armstrong, Becking, Bennett, Brewer, Cotoras, Ewing, Harte, Martinez, O'Grady, Percy, Price, Roderick, Shaw, Valdovinos, Gruner and Gillespie2016). This sequential formation within an archipelago serves as a chronosequence; each island can be conceptualized as a trial in an experiment, with each new island a younger replicate of one of these experiments (Simon Reference Simon1987; Gillespie Reference Gillespie2016).

On yet shorter timescales, climate cycles play a role as ‘species pumps’, driving repeated changes in habitat isolation and thus promoting diversification. For example, changes in sea level have repeatedly isolated and reconnected the islands of the Galápagos, which may have enhanced species diversity (Grant & Grant Reference Grant and Grant2016). Alternating periods of warming and cooling have resulted in iterated episodes of isolation facilitating differentiation and endemism in Caribbean crickets (Papadopoulou & Knowles Reference Papadopoulou and Knowles2015). Other drivers of fusion and fission cycles, such as lava flows that periodically isolate forest patches (‘kīpuka’) on a geological landscape mosaic, may act as ‘crucibles’ for evolution (Carson et al. Reference Carson, Lockwood and Craddock1990).

Ecological assembly

The equilibrium theory of island biogeography (ETIB) (MacArthur & Wilson Reference MacArthur and Wilson1967) proposed that species richness on an island is a balance between immigration, which decreases with increasing distance from a mainland source, and extinction, which decreases with increasing island size. Subsequent work demonstrated how isolation affects extinction (in addition to immigration) through the ‘rescue effect’ (Brown & Kodric-Brown Reference Brown and Kodric-Brown1977). The ETIB, though developed for de novo oceanic islands, has been applied to diverse insular systems, most notably to examine the conservation implications of fragmentation on species diversity (Triantis & Bhagwat Reference Triantis, Bhagwat, Ladle and Whittaker2011). In addition, the ETIB fortified concepts of meta-populations, in which the colonization–extinction dynamics of a population of populations are modelled in ecological time (Levins Reference Levins1969), and these concepts were later extended for communities (Leibold et al. Reference Leibold, Holyoak, Mouquet, Amarasekare, Chase, Hoopes, Holt, Shurin, Law and Tilman2004).

The main aspect of the ETIB used for conservation comes out of the ‘single large or several small’ debate (Simberloff & Abele Reference Simberloff and Abele1976). Because larger and less isolated areas support more species, emphasis is placed on mitigating the effects of habitat fragmentation to allow habitats to be as large and as contiguous as possible (Whittaker et al. Reference Whittaker, Araújo, Jepson, Ladle, Watson and Willis2005). While there is a tremendous body of research that supports these overall premises (Warren et al. Reference Warren, Simberloff, Ricklefs, Aguilée, Condamine, Gravel, Morlon, Mouquet, Rosindell, Casquet, Conti, Cornuault, Fernández-Palacios, Hengl, Norder, Rijsdijk, Sanmartín, Strasberg, Triantis, Valente, Whittaker, Gillespie, Emerson and Thébaud2015), there are two key elements in the ETIB that are still debated, namely equilibrium (Harmon et al. Reference Harmon, Harrison and Price2015) and turnover (Shaw & Gillespie Reference Shaw and Gillespie2016). For example, it has been argued that communities are rarely at equilibrium, either because there has not been sufficient time to reach an equilibrium state or because the rate of temporal change to habitats or islands outpaces that of biological processes (Chambers et al. Reference Chambers, Negron-Juarez, Marra, Di Vittorio, Tews, Roberts, Ribeiro, Trumbore and Higuchi2013). Moreover, the idea of continual species turnover contrasts strikingly with the phenomenon of priority effects, in which an early colonizing species in an area has an advantage over subsequent colonizers (Fukami Reference Fukami2015) and can lead to patterns of endemism over evolutionary timescales (Shaw & Gillespie Reference Shaw and Gillespie2016). Understanding the transition between ecological and evolutionary processes is a promising new avenue for research using island chronosequences, which allow the study of communities over ecological and evolutionary time (Rominger et al. Reference Rominger, Goodman, Lim, Armstrong, Becking, Bennett, Brewer, Cotoras, Ewing, Harte, Martinez, O'Grady, Percy, Price, Roderick, Shaw, Valdovinos, Gruner and Gillespie2016).

Both concepts of turnover and equilibrium have key relevance to conservation. For instance, given the time required for evolution, the interplay between colonization and speciation will necessarily be modified through disturbance, whether geological or ecological, natural or anthropogenic. Disturbances may effectively ‘reset’ a community to a more simple species composition, opening it to colonization by available propagules, with the time required to reach an equilibrium depending on propagule availability. On isolated islands, native communities are largely the product of within-archipelago colonization and, associated with the paucity of colonizers, speciation. With the advent of humans and associated commensals, the availability of propagules has greatly increased. Thus, based on the arguments above, the impact of the increased extra-archipelago propagule pressure will depend on local disturbance, ecological turnover and biotic resistance (Florencio et al. Reference Florencio, Rigal, Borges, Cardoso, Santos and Lobo2016).

Ecosystem function

Ecologists have long debated the relationship between diversity and the functioning of ecosystems (Hooper et al. Reference Hooper, Chapin, Ewel, Hector, Inchausti, Lavorel, Lawton, Lodge, Loreau and Naeem2005). At one level, species have been thought to make singular, unique contributions to the ecosystems. A famous analogy likened species to the rivets in a plane, their combined loss eventually causing the entire structure to fall apart (Ehrlich & Ehrlich Reference Ehrlich and Ehrlich1981). Alternatively, species have been viewed as redundant in a system, with multiple species performing similar functional roles and so systems are resilient to some loss of species (Walker Reference Walker1992). Others have said that the role of specific species in a community is context dependent, and the effect following their removal is individualist or unpredictable (Lawton Reference Lawton1994). Thus, effects of disturbance and species loss or gain may be more easily studied on islands, and understanding of the factors leading to increased vulnerability across island systems is invaluable.

HUMAN IMPACT ON INSULAR SYSTEMS

The need for local understanding of how the biodiversity and the associated environment have been impacted by anthropogenic introductions (Kueffer et al. Reference Kueffer, Daehler, Torres-Santana, Lavergne, Meyer, Otto and Silva2010), and what trajectories they will follow given current and future extinctions and climate change (Kueffer et al. Reference Kueffer, Drake and Fernández-Palacios2014), are particularly critical on islands. Islands often have limited biological and human resources, are isolated and are exposed to storms and sea level rise, and therefore have limited resilience to new perturbations. Further, island economies that rely on the quality of their natural environment, notably through tourism, fishing and subsistence farming, are deeply affected by degradation of their environment (Connell Reference Connell2013). Some islands, including Great Britain and many Mediterranean islands, have had a long history of human influence, such that it is difficult to discern natural from anthropogenic influences. In contrast, the impacts of humans have generally been more recent on remote island systems. Here, paleontological studies have helped discern where natural processes or human impacts, whether direct or indirect, have triggered prehistoric turnover in dominant vegetation types (Burney et al. Reference Burney, James, Burney, Olson, Kikuchi, Wagner, Burney, McCloskey, Kikuchi, Grady, Gage and Nishek2001; Crowley et al. Reference Crowley, Godfrey, Bankoff, Perry, Culleton, Kennett, Sutherland, Samonds and Burney2017). Reasons for high extinction rates include the vulnerability of narrowly endemic species associated with their smaller population sizes, combined with their evolutionary isolation. Body size appears also to influence vulnerability to extinction, with larger species being more extinction-prone (Terzopoulou et al. Reference Terzopoulou, Rigal, Whittaker, Borges and Triantis2015). The introduction of new species and other forms of disturbance, including climate change, which weaken ecological and spatial barriers, may lead to hybridization as opposed to extinction, particularly among certain lineages of plant species, given that strong post-zygotic isolating barriers are poorly developed in island plants (Crawford & Archibald Reference Crawford and Archibald2017). These extinction factors, combined with global change phenomenon, have led to the loss of many island endemic lineages. For example, up to 2000 species of birds, mostly flightless rails, were lost following human colonization in Melanesia, Micronesia and Polynesia (Steadman Reference Steadman1995). Likewise, achatinellid tree snails in the Pacific Islands, with estimated densities of up to 500 per tree in 1903 in the Hawaiian lowlands, have largely disappeared in the last 100 years (Hadfield et al. Reference Hadfield, Miller and Anne1993). However, the overall accumulation of extirpated species might be mediated by the taxonomic disharmony on isolated islands, where introduced species are more likely to play unique or under-represented functional roles than on the mainland (Cushman Reference Cushman, Vitousek, Loope and Adsersen1995).

Human impacts on island systems can be grouped into five categories, recognizing these categories are neither independent nor comprehensive: climate change, habitat modification, direct exploitation, invasion and disease. The relative importance of these varies across islands, and many island systems face multiple anthropogenic pressures simultaneously and synergistically (Fig. 2).

Figure 2 Examples of major threats to island ecosystems, with illustrations from the Hawaiian Islands and Micronesia. (a) Urban development. Aerial photo of Honolulu, showing the entirely modified urban environment of Waikiki. The initial wetlands were first modified in the mid-15th century to cultivate wetland taro and for fishponds, then they were drained in the 1920s with construction of the Ala Wai Canal to mitigate mosquito-borne human disease with further urbanization. Photo credit: George K. Roderick. (b) Crops. Pineapples, with sugar, were major plantation crops in Hawaiʻi starting in the mid-1800s (Perroy et al. Reference Perroy, Melrose and Cares2016). Acreage in pineapple and sugar halved between 1980 and 2015 and Maui Land and Pineapple Company (shown here) closed in 2009. Currently, many plantations lie idle and weed ridden, with an uncertain future. Photo credit: George K. Roderick. (c) Pasture. Cattle were introduced into the Hawaiian Islands in the 1790s, and ranching started in the early-to-mid-1800s, and patches of native forest became increasingly restricted to inaccessible gulches, as shown in this photo of Hakalau Forest National Wildlife Refuge. Recent efforts are restoring areas of degraded pasture and forest, such as those at Auwahi on Maui (Cabin Reference Cabin2013). Photo credit: George K. Roderick. (d) Climate change. The many atolls that make up Micronesia now suffer frequent inundation as a result of sea level rise, as illustrated in this photo of Majuro in the Marshall Islands, which has become a vocal participant in global climate change discussions (Labriola Reference Labriola2016). Many low-lying island nations of the Pacific are buying tracts of land on higher islands (Green Reference Green2016). Photo credit: George K. Roderick. (e) Invasions. One of the most insidious invaders of native ecosystems in the Hawaiian Islands is kahili ginger, Hedychium gardnerianum (The Nature Conservancy of Hawaii 2011), as shown: the left side shows a monotypic stand of ginger, the right a relatively pristine forest. The fence in front of the ginger, marking the boundary of the Waikamoi Preserve, in no way inhibits the spread, which is controlled to the extent possible by the diligence of The Nature Conservancy of Hawaii employees. Photo credit: George K. Roderick. (f) Disease. Studies, such as that which is shown here at Hakalau Forest National Wildlife Refuge, show that native honeycreepers such as the ʻapapane are vulnerable to pox and malaria (LaPointe Reference LaPointe2008) and might be affected by upslope expansion of avian diseases (Camp et al. Reference Camp, Pratt, Gorresen, Jeffrey and Woodworth2010). Photo credit: George K. Roderick. (g) Direct exploitation. In the Hawaiian Islands, the strongest evidence of direct exploitation is the use of native bird feathers in capes. Perhaps most dramatic was the ‘Oʻo, which was common in the 1800s, but was extinct by the mid-1900s, and was exploited for a small tuft of yellow shoulder feathers (Lovette Reference Lovette2008). Photo credit: Honolulu Museum of Art.

Climate change

The human inhabitants of oceanic islands are already dealing with the reality of climate change, as is particularly reflected in rising sea levels (Shenk Reference Shenk2011). Governments of smaller islands have already purchased land on larger islands as a final effort for human survival (Caramel Reference Caramel2014). In terms of direct effects of climate, mean annual temperatures are expected to rise on oceanic islands despite buffering effects from surrounding oceans; in addition, slightly greater annual precipitation is predicted for the majority of islands in the future, with an increasing trend towards the end of the century, although large-scale precipitation projections might disregard the influence of island topography on precipitation patterns at smaller scales (Harter et al. Reference Harter, Irl, Seo, Steinbauer, Gillespie, Triantis, Fernández Palacios and Beierkuhnlein2015). Likewise, the projected increase in intensity of extreme weather events (e.g. droughts, storm surges and hurricanes) has the potential for greater damage in delicate island habitats (Seneviratne et al. Reference Seneviratne, Nicholls, Easterling, Goodess, Kanae, Kossin, Luo, Marengo, McInnes, Rahimi, Field, Barros, Stocker, Qin, Dokken, Ebi, Mastrandrea, Mach, Plattner, Allen, Tignor and Midgley2012; Nurse et al. Reference Nurse, McLean, Agard, Briguglio, Duvat-Magnan, Pelesikoti, Tompkins, Webb, Barros, Field, Dokken, Mastrandrea, Mach, Bilir, Chatterjee, Ebi, Estrada, Genova, Girma, Kissel, Levy, MacCracken, Mastrandrea and White2014).

Habitat modification

The modification of habitats for human habitation, agriculture, livestock and other resource extraction is a major global conservation concern that is not limited to islands (Foley et al. Reference Foley, DeFries, Asner, Barford, Bonan, Carpenter, Chapin, Coe, Daily and Gibbs2005). However, the insular nature and smaller geographic size of islands can lead to two distinct consequences. First, the biota are more vulnerable to reductions in habitat for simple demographic reasons, as population sizes are usually small, coupled with the higher uniqueness – or endemism – of the biota. Second, islands that are independent nations often have a very limited economic base; thus, of the 48 countries on the UN's list of Least Developed Countries, nine are islands (five in the Pacific and four in the Indian Ocean). Poverty itself places tremendous demands on resources, leading to further exploitation and habitat modification.

Direct exploitation

Linked to habitat modification, direct exploitation of natural resources has had a major historical impact on island species, perhaps most notably flightless birds (Steadman Reference Steadman1995). In the Pacific, ancestors of the Polynesians spread across most island groups in Oceania, clearing forests, cultivating crops, raising domesticated animals and hunting megafauna to extinction (Steadman & Martin Reference Steadman and Martin2003). Currently, direct exploitation is most apparent on economically poorer islands, such as Madagascar (Golden et al. Reference Golden, Bonds, Brashares, Rasolofoniaina and Kremen2014), where there are substantial pressures on the natural resources on which people depend for day-to-day survival (Connell Reference Connell2013).

Invasion

On oceanic islands, more extinctions have been attributed to introduced species than to habitat loss alone (Brooks et al. Reference Brooks, Mittermeier, Mittermeier, Da Fonseca, Rylands, Konstant, Flick, Pilgrim, Oldfield, Magin and Hilton-Taylor2002). Humans have eroded biogeographical barriers by mediating dispersal of species into new regions where they can naturalize and cause ecological damage. A global database of 481 mainland and 362 island regions shows that, in total, 13 138 plant species (3.9% of extant global vascular flora) have become naturalized somewhere on the globe as a result of human activity (van Kleunen et al. Reference van Kleunen, Dawson and Maurel2015), with the Pacific Islands showing the fastest increase in species numbers with respect to land area. Although the relative vulnerability of continents and islands to biotic invasions has long been debated (Elton Reference Elton1958), it is generally held that the severity of invasive species impacts has been greater in isolated insular systems (D'Antonio & Dudley Reference D'Antonio, Dudley, Vitousek, Loope and Adsersen1995).

The impact of invasive species can become more profound due to their ability to modify the environment (so-called ‘ecosystem engineers’), which can lead to facilitation with other non-natives (Borges et al. Reference Borges, Lobo, Azevedo, Gaspar, Melo and Nunes2006). In plants, characteristics such as prolific seed production, dispersal ability, shade tolerance, nitrogen fixation and the production of allelopathic compounds can cause dramatic ecosystem-level effects. For example, the Macaronesian nitrogen-fixing tree Morella faya appears to facilitate subsequent invasions by enhancing nitrogen availability in nutrient-poor soils (Vitousek et al. Reference Vitousek, Walker, Whiteaker, Mueller-Dombois and Matson1987). Such facilitation demonstrates the potential for ‘invasional meltdown’ (Simberloff & Von Holle Reference Simberloff and Von Holle1999), with synergistic impacts being greater than with either species alone. Likewise, endangerment and extinction of native species may precipitate co-extinctions of mutualists (Cox & Elmqvist Reference Cox and Elmqvist2000).

Disease

Introduction of non-native species (including humans) to islands has frequently been accompanied by diseases that find targets in naïve species and cause rapid extinction events. Among indigenous peoples, catastrophic declines in population sizes associated with the arrival of mainland human populations in the 1800s are well known in islands ranging from the offshore Scottish islets of St Kilda (Keay & Keay Reference Keay and Keay1994) to the remote islands of the Pacific (Kunitz Reference Kunitz1996), and are generally attributed to the effects of disease as a function of the susceptibility of the population. Native species have suffered similar impacts. Thus, in the Marquesas Islands, the endemic genus of Pomarea flycatchers appear to have succumbed to malaria, while the more recently arriving Marquesan reed warblers may be resistant (Gillespie et al. Reference Gillespie, Claridge and Goodacre2008). In Hawaiʻi, avian malaria has been linked to the decline or extinction of 60 endemic forest bird species (Sodhi et al. Reference Sodhi, Brook, Bradshaw, Levin, Carpenter, Godfray, Kinzig, Loreau, Losos, Walker and Wilcove2009).

The impacts of disease are closely tied with other anthropogenic effects such as non-native species and climate change. Thus, avian malaria and avian pox, which have been important agents in the extinction of many endemic island birds and have also caused substantial population change and range contraction (Ralph & Fancy Reference Ralph and Fancy1994), rely on the introduced mosquito vector Culex quinquefasciatus for transmission. Likewise, global warming is expected to increase the occurrence, distribution and intensity of avian malaria and to threaten high-elevation refugia (LaPointe et al. Reference LaPointe, Atkinson and Samuel2012).

UNDERSTANDING AND ADDRESSING CONSERVATION CHALLENGES

It is clear that islands vary widely in biophysical properties. Therefore, as biologists, significant challenges are: (1) to identify and catalogue biological diversity and characterize its structure across diverse landscapes and archipelagos; and (2) to assess the nature of interactions with other taxa in order to predict the attributes of susceptible versus resilient communities in the face of abiotic and biotic change.

Discovery and taxonomic characterization of biodiversity

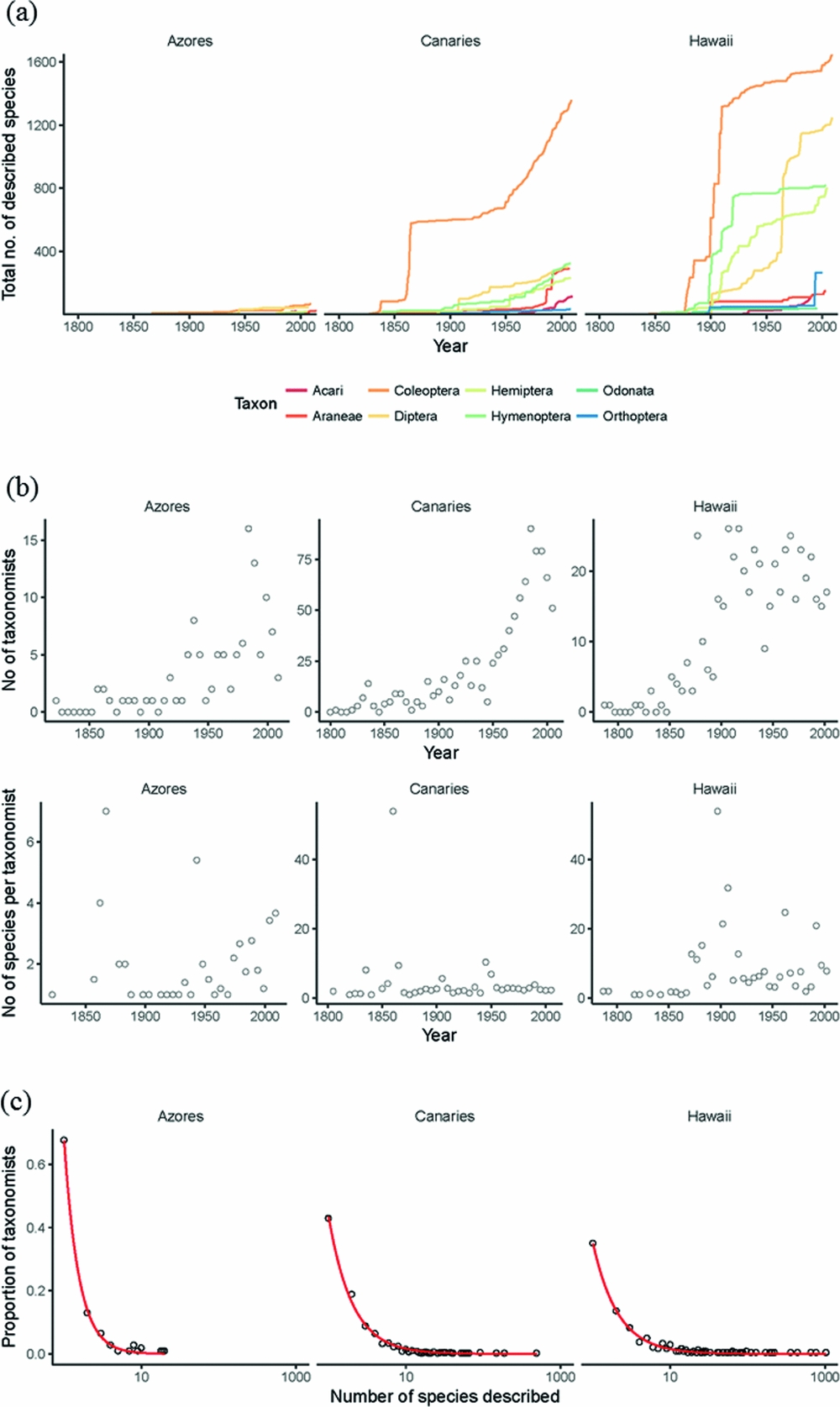

One of the first challenges is to recognize (and then close) the taxonomic impediment gap on islands. Islands have higher proportions of endemic species (Kier et al. Reference Kier, Kreft, Lee, Jetz, Ibisch, Nowicki, Mutke and Barthlott2009), but bear a disproportionate burden of global extinctions (Manne et al. Reference Manne, Brooks and Pimm1999). In order to gauge more closely the relative impact of anthropogenic change on island systems we need an accurate picture of both richness and endemism on islands, yet, considering that archipelagos such as Hawaiʻi and Macaronesia are relatively well studied with regards to eco-evolutionary theory, a surprising portion of island diversity remains undescribed (Fig. 3(a)). This shortfall varies between archipelagos, but can be substantial, and variation in taxonomic effort within and between archipelagos has the potential to obscure biogeographic patterns in species richness (Gray & Cavers Reference Gray and Cavers2014). For example, the Azores (Portugal) may have so few of its extant species described that reliable quantitative estimates of its true diversity are not possible (Lobo & Borges Reference Lobo, Borges, Serrano, Borges, Boieiro and Oromí2010). This taxonomic impediment is especially worrying given the multitude of threats that island biotas face; much diversity may have gone or will go extinct without ever being taxonomically described. These anthropogenic extinctions are already likely masking pre-human biogeographic patterns of diversity (Cardoso et al. Reference Cardoso, Arnedo, Triantis and Borges2010).

Figure 3 Temporal trends in taxonomic description and taxonomic effort. (a) Cumulative number of described species over time for various arthropod orders for the Azorean, Canarian and Hawaiian archipelagos. Data were obtained from recent arthropod checklists (Nishida Reference Nishida2002; Borges et al. Reference Borges, Cunha, Gabriel, Martins, Silva and Vieira2005). (b) Trends over time (5-year bins) in the number of taxonomists and the number of species described per taxonomist. (c) Distribution of species descriptions among taxonomists. Most taxonomists describe few species, but there are fewer singletons (taxonomists that describe only one species) on Hawaiʻi. The lines represent non-parametric smoothed best-fit lines (LOESS regression).

There are, however, some promising signs. Using comprehensive taxonomic checklists for the arthropod biotas of three archipelagos (Nishida Reference Nishida2002; Borges et al. Reference Borges, Cunha, Gabriel, Martins, Silva and Vieira2005), the rate of species description does not appear to be abating (Fig. 3(b)). In particular, the rate of growth in the number of taxonomists working on Canary Island arthropods appears to be increasing (Fig. 3(b)). This trend of increasing numbers of taxonomists also appears to be true globally for a variety of taxonomic groups (Joppa et al. Reference Joppa, Roberts, Myers and Pimm2011). Further, the species-to-taxonomist ratio appears not to be declining (Fig. 3(b)), suggesting that the declining pool of undescribed species (through cumulative taxonomic effort and/or species extinctions) has yet to limit the pace of current taxonomic efforts (cf. Joppa et al. Reference Joppa, Roberts, Myers and Pimm2011; Costello et al. Reference Costello, May and Stork2013). It is unclear for how long this trend of unabating taxonomic description will be sustained. Hawaiʻi appears to show a decreasing trend in numbers of taxonomists despite greater taxonomic efficiency, perhaps because most Hawaiian taxonomic effort is driven by proportionally fewer people (Fig. 3(c)).

Use of molecular methods may enhance the ability to identify cryptic species and stimulate subsequent taxonomic description. For example, molecular evidence suggests that the notoriously low endemism of the Azorean biota may be due to cryptic diversity (Schaefer et al. Reference Schaefer, Moura, Belo Maciel, Silva, Rumsey and Carine2011), and it is increasingly recognized that cryptic species may be a significant part of island biotas (Crawford & Stuessy Reference Crawford and Stuessy2016). Advances in rapid biodiversity assessment techniques (e.g. meta-barcoding) now allow rapid and bulk recovery of molecular sequences from pooled community samples or environmental DNA, which may help elucidate community structures from samples that would otherwise be limited by traditional taxonomic approaches (Rees et al. Reference Rees, Maddison, Middleditch, Patmore and Gough2014; Papadopoulou et al. Reference Papadopoulou, Taberlet and Zinger2015).

Community resilience in the face of change

Given that islands harbour high species diversity, local endemism and particular niche affinities, a key challenge is to understand how communities of organisms will respond to human-mediated change in both biotic and abiotic variables. With regards to climate, recent approaches now incorporate the role of climatic cycles and associated changes in ocean currents, in conjunction with changes in area, isolation and elevation, all of which may have shaped biodiversity on many islands in the past (Fernández-Palacios et al. Reference Fernández-Palacios, Rijsdijk, Norder, Otto, de Nascimento, Fernández Lugo, Tjørve and Whittaker2016). For instance, there is clear evidence that communities are under pressure from changing climate, from the islands of the Mascarenes, Greece (Triantis & Mylonas Reference Triantis, Mylonas, Gillespie and Clague2009), the Azorean Islands (Ferreira et al. Reference Ferreira, Cardoso, Borges, Gabriel, de Azevedo, Reis, Araújo and Elias2016) and Bermuda (Glasspool & Sterrer Reference Glasspool, Sterrer, Gillespie and Clague2009). Small, low-elevation, topographically homogeneous islands are least resilient to climate change pressures as a result of rising sea levels, and in many instances local habitat alteration interacts synergistically with novel abiotic perturbations, causing even greater consequences for island communities (Harter et al. Reference Harter, Irl, Seo, Steinbauer, Gillespie, Triantis, Fernández Palacios and Beierkuhnlein2015).

Another challenge is to determine how communities will change from additions and deletions of species. Existing communities may be compiled of well-established non-native taxa currently playing similar functional roles to those species that have become extirpated (Davis et al. Reference Davis, Chew, Hobbs, Lugo, Ewel, Vermeij, Brown, Rosenzweig, Gardener and Carroll2011). Network theory is providing an increasingly robust framework to understand species interactions and to predict the consequences of disturbance at a community level (Traveset et al. Reference Traveset, Tur, Trøjelsgaard, Heleno, Castro-Urgal and Olesen2016b), showing both how alien species infiltrate receptive communities and how and to what extent they can impact and modify the structure of such communities (Romanuk et al. Reference Romanuk, Zhou, Valdovinos, Martinez, Bohan, Dumbrell and Massol2017). Combining plant–pollinator networks with islands as model systems serves to identify quantitative metrics that can describe changes in network patterns relevant to conservation (Traveset et al. Reference Traveset, Tur, Trøjelsgaard, Heleno, Castro-Urgal and Olesen2016b). Some metrics may be suitable indicators of anthropogenic changes in pollinator communities that may allow assessment of structural and functional robustness and integrity of ecosystems (Kaiser-Bunbury & Blüthgen Reference Kaiser-Bunbury and Blüthgen2015). In some cases, native pollinators may be more resistant to exotic fauna than predicted by theory (Picanço et al. Reference Picanço, Rigal, Matthews, Cardoso and Borges2017).

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Beyond the anthropogenic pressures impinging upon the ecological and evolutionary study of islands, human institutions may at times impede fundamental research and environmental conservation. Research may be hindered on islands due to confusion in political jurisdiction, as islands often are managed on a regional basis by multiple institutions or countries. Additional institutional challenges include: mobilizing and accessibility of natural history collections and associated data; balancing public stakeholders with conservation objectives (e.g. hunting lobby vs. eradication); and navigating national and international funding agencies. Paradoxically, often the best economic health for islands is provided by programmes such as tourism and agriculture that, when managed poorly, may be dilapidating to the future of island ecosystems.

Current discourse analyses how island systems negotiate with the challenges of balancing development with sustainability (Connell Reference Connellin press), incorporating indigenous and local knowledge to improve island environmental futures (Lauer Reference Lauerin press) and harnessing environmental education on islands (Fumiyo in press). Strides towards uniting researchers across disciplines for the study of island biology and conservation are now evident. The fledgling Society for Island Biology (SIB), founded at the summer 2016 Island Biology meeting in the Azores (Gabriel et al. Reference Gabriel, Elias, Amorim and Borges2016), is one such example. There have been cross-disciplinary conferences organized around current research for island biology (Kueffer et al. Reference Kueffer, Drake and Fernández-Palacios2014) and special issues of journals focusing on the discourse of such symposia (Traveset et al. Reference Traveset, Fernández-Palacios, Kueffer, Bellingham, Morden and Drake2016a). A working group of researchers has put together a survey of the 50 fundamental questions in island biology (Patiño et al. Reference Patiño, Whittaker, Borges, Fernández-Palacios, Ah-Peng, Araújo, Ávila, Cardoso, Cornuault, de Boer, de Nascimento, Gil, González Castro, Gruner, Heleno, Hortal, Illera, Kaiser-Bunbury, Matthews, Papadopoulou, Pettorelli, Price, Santos, Steinbauer, Triantis, Valente, Vargas, Weigelt and Emerson2017). Such open dialogue will help to uncover the similarities in island systems and find suitable solutions that may be applied across islands and the mainland for anthropogenic disturbance. Moreover, the characteristics of islands that make them both exquisite study systems for fundamental ecology and evolution and the archetypal endangered systems on the leading edge of global change also position islands as the irreplaceable testing grounds for conservation solutions.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

An early version of this manuscript benefitted from critical comments by Ian J. Wang, Jeffrey Frederick, Michael L. Yuan, Drew Hart, Guinevere O. Wogan and Emma Steigerwald.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None.

FUNDING

The research was supported by the National Science Foundation (D. S. Gruner, DEB 1240774) and (R. G. Gillespie, DEB 1241253).