Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is defined by fat accumulation in the liver in the absence of excess alcohol consumption. Described histologically, NAFLD may range from simple steatosis (non-alcoholic fatty liver (NAFL)), where there is fatty infiltration but no evidence of hepatocellular injury, to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), where there is evidence of inflammation and ballooning, with or without fibrosis(Reference Chalasani, Younossi and Lavine1). Although the early stage of NAFL is often considered benign, 25 % of patients will progress to more serious disease(Reference Diehl and Day2,Reference Nasr, Ignatova and Kechagias3) . NAFLD is now the second most common cause of chronic liver disease among individuals listed for liver transplantation in the USA(Reference Cholankeril, Wong and Hu4). In the UK and Europe, the number of NAFLD-related liver transplantation has increased dramatically within the past 10 years(Reference Williams, Aspinall and Bellis5). Significantly, there are presently no licensed pharmaceutical agents specific for the treatment of NAFLD, although several agents, including dietary supplements, are in Phase 2 and Phase 3 clinical trials(Reference Wong, Chitturi and Wong6). Given the close association between NAFLD and obesity, weight loss through dietary and lifestyle intervention is the mainstay of present clinical management(Reference Chalasani, Younossi and Lavine1,7,8) .

Diagnosis

Presently available diagnostic tools (liver enzymes, imaging and biopsy) are either non-specific, expensive, or invasive. The lack of an acceptable, inexpensive diagnostic tool makes large-scale population studies difficult(Reference Schwenzer, Springer and Schraml9). Elevated liver enzymes (aspartate and alanine transaminases) are often used to define ‘suspected NAFLD’ at a population level. However, the majority (79 %) of individuals diagnosed with NAFLD by MRI in a large population study had normal transaminase levels(Reference Browning, Szczepaniak and Dobbins10), so relying on this measure significantly underestimates the burden of disease. Imaging is non-invasive but, in the case of MRI or magnetic resonance elastography, it can be expensive and not accessible to all. Alternatively, in the case of ultrasound and transient elastography (fibroscan), it can be somewhat insensitive for the staging of NASH and fibrosis. While liver biopsies are the gold standard for staging of NASH and fibrosis, required for licencing purposes in pharmacological trials(Reference Sanyal, Brunt and Kleiner11), biopsies have their limitations, including issues with inter-rater reliability, sampling error, cost and acceptability for monitoring the condition in the long term.

NAFLD is closely associated with obesity and metabolic disorders. In a large meta-analysis of eighty-six studies, with a sample size of more than 8·5 million persons from twenty-two countries, more than 80 % of individuals with NASH and 51 % of individuals with NAFL were obese. Type 2 diabetes co-occurred in 47 % of NASH cases and 23 % of NAFL cases; metabolic syndrome was found in 71 % NASH patients and 41 % of NAFL patients(Reference Younossi, Koenig and Abdelatif12). For these reasons, clinical guidelines for NAFLD diagnosis(Reference Chalasani, Younossi and Lavine1,7,8) do not advocate general population screening, but stress that NAFLD is to be suspected in individuals with type 2 diabetes or the metabolic syndrome; defined as three or more of five risk factors for CVD and type 2 diabetes: hypertension, hypertriacylglycerolaemia, lowered HDL cholesterol, raised fasting glucose and central obesity defined by increased waist circumference(Reference Alberti, Eckel and Grundy13).

Prevalence

Given the challenges of NAFLD diagnosis, the prevalence of NAFLD can only be estimated and estimates vary depending on the diagnostic tool used. Nonetheless, it is clear that the prevalence of NAFLD varies by region and ethnicity, and the global prevalence of NAFLD is estimated to be 24 %(Reference Younossi, Anstee and Marietti14). The highest reported rates are in the Middle East (32 %) and South America (31 %), followed by Asia (27 %), the USA and the UK (24 and 23 %)(Reference Younossi, Anstee and Marietti14). Recent reviews of the epidemiology of NAFLD have highlighted surprising high prevalence in Asia (27 % pooled estimate(Reference Younossi, Koenig and Abdelatif12)), with country-specific estimates ranging from 15 to 40 % for China, 25–30 % for Japan and 27–30 % for Korea and India(Reference Fan, Kim and Wong15). Prevalence estimates in North America have ranged from 11 to 46 % dependent on diagnostic modality and population studied; a recent meta-analysis with random effects model concluded a pooled average of 24 % (19–29 %) by ultrasound but only 13 % by blood testing(Reference Younossi, Koenig and Abdelatif12). Prevalence in the USA also depends on ethnicity with Hispanic Americans at highest risk (53 %) relative to Caucasians (44 %) and African Americans (35 %)(Reference Browning, Szczepaniak and Dobbins10); while American Indians have a prevalence as low as 13 %(Reference Bialek, Redd and Lynch16). Genetic variability, discussed in detail later, likely explains some, but not all of the differences in risk. The heritability of liver fat and fibrosis has estimated to be 39–52 and 50 %, respectively(Reference Schwimmer, Celedon and Lavine17,Reference Loomba, Schork and Chen18) , underscoring that the environment also plays a large role in NAFLD development. Estimates of global NASH prevalence range from 1·5 to 6·5 %(Reference Younossi, Anstee and Marietti14), with estimates of 6 and 2 % prevalence for NASH and NASH-related cirrhosis in the USA(Reference Diehl and Day2). In sum, NAFLD is a common chronic liver disease worldwide.

Natural history

As with prevalence, defining the natural history of disease progression in NAFLD has been hampered by the reliance on liver biopsies. While only recently the disease was perceived as progressing somewhat linearly from NAFL to NASH, then to NASH plus fibrosis, and then to cirrhosis and end-stage liver disease requiring transplantation, including occasionally hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)(Reference Moore19); this perspective continues to evolve as outlined (Fig. 1). While simple steatosis in the absence of fibrosis is generally thought to have a more benign course of disease in terms of liver-specific outcomes and mortality(Reference Ekstedt, Hagstrom and Nasr20,Reference Hagstrom, Nasr and Ekstedt21) , some patients with NAFL, so-called ‘rapid progressors’ can progress towards well-defined NASH with bridging fibrosis within a very few years(Reference Pais, Charlotte and Fedchuk22). In addition, as diagrammed (Fig. 1), based on present data it cannot be excluded that in some cases, perhaps dependent on genetic susceptibilities, a NASH liver may arise from a normal liver(Reference Cohen, Horton and Hobbs23). Moreover, an increasing number of studies suggests that HCC can develop in a non-cirrhotic liver, further altering the early linear model of NAFLD natural history (Fig. 1)(Reference Piscaglia, Svegliati-Baroni and Barchetti24–Reference Stine, Wentworth and Zimmet26). Increased risk for HCC in NASH likely relates to body weight, as 80 % of patients with NASH are also obese(Reference Younossi, Koenig and Abdelatif12). A recent population-based cohort study of 5·24 million UK adults has demonstrated large increases in risk (hazard ratio 1·19 per 5 kg/m2 increase in BMI) for liver cancer occurring in a linear fashion with increasing BMI(Reference Bhaskaran, Douglas and Forbes27).

Fig. 1. The dynamic spectrum of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). The liver can accumulate fat (non-alcoholic fatty liver (NAFL)) in the absence or presence of inflammation (non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH)) and fibrosis. These processes are reversible as indicated by the dashed arrows. Poor and over-nutrition can influence the development and progression of NAFLD as indicated by the red arrows; whereas weight loss and a healthy diet is the mainstay of successful NAFLD treatment as indicated by the green arrows. Evidence from clinical trials in NAFLD suggest even fibrosis can regress. Questions remain about whether the development of steatohepatitis is an independent maladaptive process from the development of steatosis; and whether hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) can develop directly from NAFL and NASH without the development of fibrosis.

Progression to severe liver disease in adults is in the order of decades(Reference Diehl and Day2,Reference Younossi, Koenig and Abdelatif12,Reference D'Avola, Labgaa and Villanueva28) . Multiple large retrospective cohort studies (>600 patients, mean follow-up 20 years) have now demonstrated that it is fibrosis, rather than NASH, on index biopsy that is associated most strongly with increased risk of mortality and liver-related outcomes such as decompensation or transplant(Reference Hagstrom, Nasr and Ekstedt21,Reference Angulo, Kleiner and Dam-Larsen29) . This work suggests NAFLD activity score is not clearly prognostic(Reference Angulo, Kleiner and Dam-Larsen29), and time to development of severe liver disease is dependent on fibrosis stage at presentation. Approximately 22–26 years for F0–1, 9·3 years for F2, 2·3 years for F3 and 0·9 years to liver decompensation in F4 fibrosis(Reference Hagstrom, Nasr and Ekstedt21). However, the risk of selection bias for follow-up liver biopsy in single-centre studies is substantial, and rates of progression may thus be overestimated in the general population. Some have expressed concern about the risk of overdiagnosis in screening and monitoring individuals for NAFLD, when the majority will not develop advanced liver disease(Reference Rowe30).

Conversely, a recent population study (n 3041 adults >45) assessed fibrosis by transient elastography and demonstrated clinically relevant fibrosis in the community was a concerning 5·6 %(Reference Koehler, Plompen and Schouten31). Furthermore, modelling indicates the burden of NASH, end-stage liver disease (decompensated cirrhosis, HCC) and liver-related deaths will continue to grow(Reference Estes, Razavi and Loomba32). Importantly, while severe liver outcomes may be the third rather than the primary cause of death in NASH patients, worryingly the primary and secondary causes of death are CVD and extra-hepatic cancers(Reference Angulo, Kleiner and Dam-Larsen29). A growing body of evidence suggests the effects of NAFLD extend beyond the liver, and NAFLD precedes and/or exacerbates the development of type 2 diabetes, hypertension and CVD(Reference Lonardo, Nascimbeni and Mantovani33). From a public health perspective, NAFLD, in particular NASH, cannot be ignored.

Pathogenesis

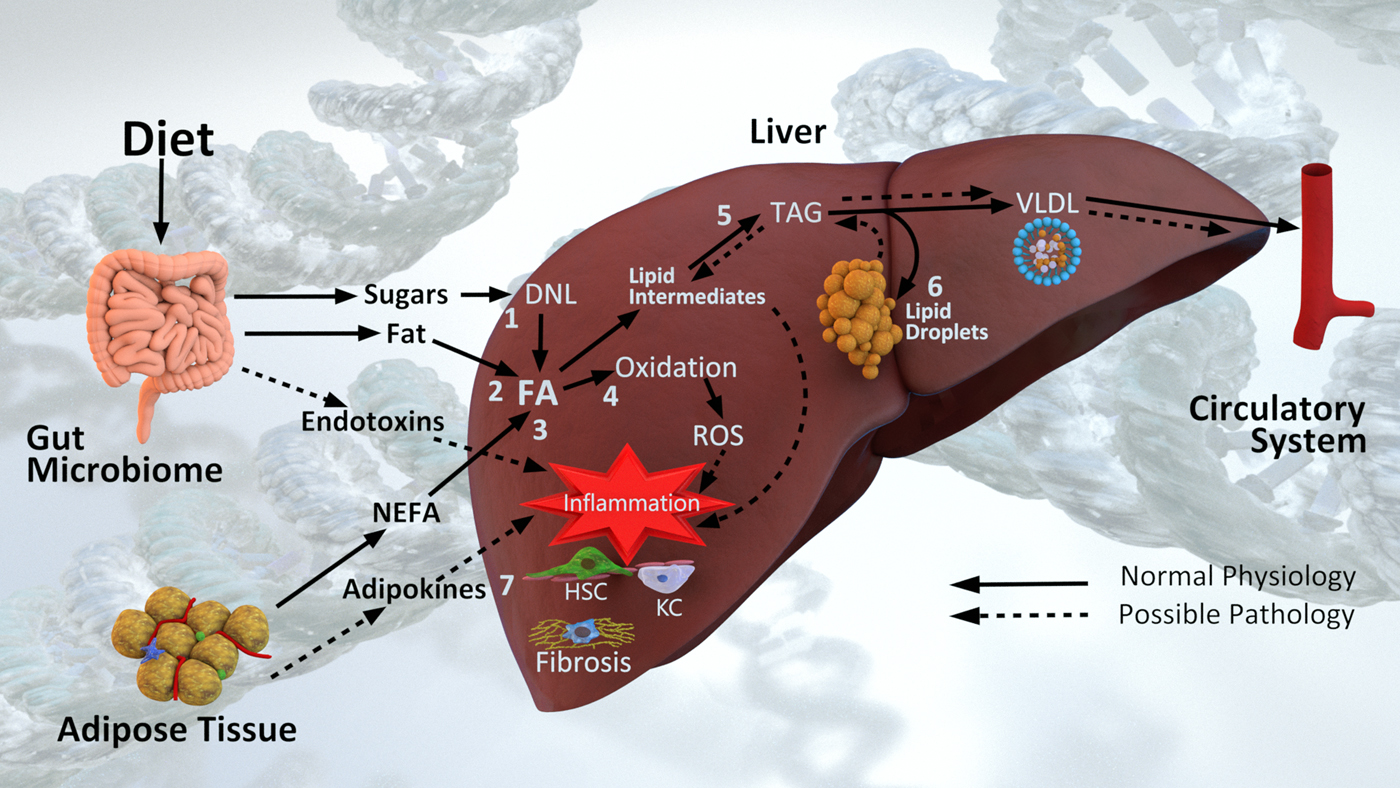

NAFLD is a complex phenotype that arises from dynamic interactions between diet, lifestyle and genetic factors, and involving crosstalk between multiple organs and the intestinal microbiome. Mechanistically, NAFLD pathogenesis can be viewed as an imbalance between lipid accumulation and removal (Fig. 2). Fatty acids (FA) arise in the liver from either the diet (dietary fats delivered via chylomicrons or dietary sugars converted via de novo lipogenesis), or from the circulating NEFA pool. Under normal circumstances FA are either oxidised for energy or packaged into TAG for export and circulation in VLDL.

Fig. 2. Diet and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease pathogenesis. Fatty acids (FA) arise in the liver from (1) de novo lipogenesis (DNL) of dietary sugars, (2) dietary fat via chylomicrons and (3) the NEFA pool derived primarily from adipose tissue. In the context of normal physiology, FA are either (4) oxidised for energy or (5) esterified into TAG and exported in VLDL particles into circulation. In the context of excess energy, (6) TAG is stored in lipid droplets. Lipid intermediates, reactive oxygen species (ROS), endotoxins and adipokines all contribute to (7) inflammation and hepatic stellate cell (HSC) and Kupffer cell (KC) activation leading to liver fibrosis. Pathogenesis is also influenced by underpinning genetic and epigenetic mechanisms, and additionally is influenced by the microbiome.

The seminal view of NASH pathogenesis was one of ‘two hits’(Reference Day and James34), where steatosis was followed by oxidative stress leading to lipid peroxidation and inflammation. Layers of complexity, and ‘multiple hits’ are now recognised around these pathways; including genetic susceptibility, biological environment, behavioural factors, metabolism and the intestinal microbiome(Reference Buzzetti, Pinzani and Tsochatzis35,Reference Eslam, Valenti and Romeo36) . In particular over the past decade, the roles of lipotoxic intermediates(Reference Neuschwander-Tetri37,Reference Marra and Svegliati-Baroni38) and hepatic FA trafficking(Reference Mashek39) in NAFLD pathogenesis has come to be appreciated (Fig. 2). Intermediates in the synthesis of TAG (lysophosphatidic acid, phosphatidic acid, lysophosphatidyl choline, ceramides and diacylglycerols) are now recognised to contribute to altered insulin signalling(Reference Neuschwander-Tetri37). In addition, lipotoxic intermediates are released via extracellular vesicles also activating hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) and other parenchymal cells driving inflammation and fibrosis(Reference Marra and Svegliati-Baroni38).

The dynamics of lipid droplet formation(Reference Gluchowski, Becuwe and Walther40), and the role of autophagy in fat mobilisation(Reference Martinez-Lopez and Singh41) are also very active areas of research. Identification of the genetic risk variants described later, has underscored that lipid droplets are not merely inert bundles of TAG; they contain other lipid species, such as cholesterol esters, and are associated with a diverse array of proteins. Notably, lipolysis of TAG from both adipocyte and hepatocyte lipid droplets is more dynamic and complex than previously envisioned, and lipid droplet-associated proteins play a role in NAFLD pathogenesis(Reference Greenberg, Coleman and Kraemer42).

The progression of NAFLD involves an interplay of multiple cell types residing in the liver (Fig. 2). Lipotoxic intermediates, reactive oxygen species, endotoxins and adipokines, all drive recruitment and signalling of immune cells, including Kupffer cells; along with the activation of HSCs (Fig. 2). Activated HSCs become fibroblasts, producing fibrogenic factors and collagen, and through apoptosis drive cirrhosis development(Reference Schuppan, Surabattula and Wang43). The chronic oxidative metabolism observed in NAFLD enhances reactive oxygen species production creating a pro-oxidative state(Reference Sunny, Parks and Browning44). This overall increase in pro-oxidative/pro-inflammatory state leads to intracellular damage, activating repair mechanisms that can become hyperactive, further driving fibrosis(Reference Schuppan, Surabattula and Wang43).

Genetic risk factors

Initially identified through genome-wide association scanning as contributing to individual and ethnic differences in hepatic fat content and susceptibility to NAFLD(Reference Romeo, Kozlitina and Xing45); a missense mutation, leading to an isoleucine to methionine substitution at position 148, in the patatin-like phospholipase domain containing 3 protein (PNPLA3; I148 M variant, rs738409), has now been independently verified as associated with NAFLD severity in multiple populations. Individuals who are homozygous for this allele have markedly increased steatosis levels compared with non-carriers(Reference Romeo, Kozlitina and Xing45) and the minor allele frequency correlates positively with steatosis across populations(Reference Younossi, Anstee and Marietti14). This genetic variant is estimated to account for 30–50 % of high-risk progression of NAFLD towards fibrosis, cirrhosis and HCC(Reference Anstee, Seth and Day46). In addition, it has also been linked to alcoholic(Reference Tian, Stokowski and Kershenobich47) and viral(Reference Trepo, Pradat and Potthoff48) liver disease severity as well as HCC(Reference Liu, Patman and Leathart49). This suggests the PNPLA3 variant is not specific to NAFLD, but more generally influences susceptibility to liver disease with environmental factors (viral or toxin exposure, nutrition/diet, microbiome) playing an integral, and perhaps deterministic role. Subsequent biochemical work has demonstrated that the PNPLA3 protein is associated with lipid droplets and has hydrolase (lipase) activity against TAG in hepatocytes and against retinyl esters in HSC(Reference He, McPhaul and Li50–Reference Pirazzi, Adiels and Burza52). Disruption of PNPLA3 function leads to accumulation of TAG in hepatocytes; and the rs738409 risk allele is associated with the severity of a variety of liver diseases(Reference Trepo, Romeo and Zucman-Rossi53).

Three other common genetic variants have also been robustly associated with the development and progression of NAFLD and other liver diseases(Reference Eslam, Valenti and Romeo36). Intriguingly, these genes all encode proteins involved in the regulation of hepatocyte lipid metabolism and are linked to the severity of multiple liver diseases. In particular the rs58542926 variant of the transmembrane 6 superfamily member 2 protein results in a loss-of-function, inducing higher liver TAG content and lower circulating lipoproteins(Reference Kozlitina, Smagris and Stender54) through disrupted hepatocyte secretion of TAG and VLDL. Somewhat paradoxically, carriers of this mutation are at greater risk of liver disease but lower risk of cardiovascular events(Reference Dongiovanni, Petta and Maglio55). In addition, a common polymorphism (rs641738, C > T) variant in the membrane-bound O-acyltransferase domain-containing 7 gene has also been recently associated with alcoholic liver disease(Reference Buch, Stickel and Trepo56), NAFLD severity(Reference Luukkonen, Zhou and Hyotylainen57,Reference Mancina, Dongiovanni and Petta58) and HCC(Reference Donati, Dongiovanni and Romeo59). The variant reduces protein expression and alters phosphatidylinositol concentrations in the liver(Reference Luukkonen, Zhou and Hyotylainen57). Variation in the glucokinase regulator gene, which regulates de novo lipogenesis by controlling the influx of glucose in hepatocytes, has also been associated with NAFLD in multiple studies(Reference Speliotes, Yerges-Armstrong and Wu60–Reference Petta, Miele and Bugianesi62). The associated variant (rs780094) appears to be in linkage disequilibrium with a common missense loss-of-function glucokinase regulator mutation (rs1260326) that effects its ability to negatively regulate glucokinase, resulting in an increase in hepatocyte glucose uptake and glycolytic flux, promoting lipogenesis and hepatic steatosis(Reference Beer, Tribble and McCulloch63).

Possessing multiple risk alleles increases risk severity for NASH, fibrosis(Reference Koo, Joo and Kim64) and HCC(Reference Donati, Dongiovanni and Romeo59). While it is hoped that in the near future polygenic risk scores may improve clinical stratification and management, there is undoubtedly genetic complexity yet to be elucidated. For example, only in March 2018, Regeneron scientists reported their identification of splice variant rs72613567 (T > A) in the hydroxysteroid 17-β dehydrogenase 13 gene and its association with reduced levels of alanine transaminase and protection against chronic liver disease(Reference Abul-Husn, Cheng and Li65). The association was identified by exome sequencing of 46 544 participants with corresponding electronic health records, and then replicated in four independent cohorts. The rs72613567 variant results in a truncated protein with loss of enzymatic function that is associated with reduced risk of NASH and fibrosis, but not steatosis, suggesting the variant allele protects against progression to more clinically advanced stages of chronic liver disease. Interestingly, previous work had identified 17-β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 13 as overexpressed from hepatic lipid droplets from fatty liver patients and shown that adenovirus driven overexpression in mice induced a fatty liver phenotype(Reference Su, Wang and Jia66). The physiological substrate(s) for the enzyme remains unknown, but in vitro it has activity against numerous steroid and bioactive lipids (e.g. leukotriene B4)(Reference Abul-Husn, Cheng and Li65). These data highlight again the role of lipid intermediates and lipid droplet dynamics in the pathogenesis of NAFLD, and open the possibility of targeting hydroxysteroid 17-β dehydrogenase 13 therapeutically.

Nutrition and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

While genetic mechanisms continue to be described, it is important to acknowledge the interplay between genetic background and environmental factors. Although genetic risk for NAFLD influences pathogenesis, the phenotypic threshold is strongly influenced by environmental factors such as adiposity, insulin resistance and diet(Reference Eslam, Valenti and Romeo36). For example, recent work has demonstrated that for three of the aforementioned risk variants (PNPLA3, transmembrane 6 superfamily member 2 protein, glucokinase regulator), adiposity as measured by BMI greatly amplified the genetic risk(Reference Stender, Kozlitina and Nordestgaard67). With NAFLD disease progression linked closely to obesity and type 2 diabetes, it is clear that diet and lifestyle are key modifiable risk factors.

Weight loss for the treatment of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

Hyper-energetic diets, containing high levels of saturated fat, refined carbohydrates and sugar-sweetened beverages, are strongly implicated in NAFLD pathogenesis. Weight gain and obesity are closely associated with NAFLD progression, therefore dietary and lifestyle changes aimed at weight loss are fundamental to all clinical management guidelines for NAFLD(Reference Chalasani, Younossi and Lavine1,7,8) . This includes eating a healthy diet and increasing physical activity to prevent and resolve NAFLD, regardless of BMI, as advised by both the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence(8) and the European Association for the Study of the Liver(7). Significant reduction in steatosis and hepatic markers of NAFLD have generally been observed with 5–10 % weight loss (Reference Kenneally, Sier and Moore68,Reference Heymsfield and Wadden69) ; although weight reductions of >10 % may be required for resolution of NASH and reducing fibrosis and portal inflammation(Reference Vilar-Gomez, Martinez-Perez and Calzadilla-Bertot70). In general, combining dietary and physical activity interventions appears most effective, as are interventions of longer duration and greater intensity (multicomponent; more contact time, ≥14 times in 6 months); although trial heterogeneity can confound systematic review(Reference Kenneally, Sier and Moore68,Reference Heymsfield and Wadden69,Reference Katsagoni, Georgoulis and Papatheodoridis71) . Because achieving and maintaining 5–10 % weight loss is a significant challenge for many(Reference Heymsfield and Wadden69,Reference Franz, Boucher and Rutten-Ramos72) , a pertinent question is whether or not improving the nutritional quality of the diet and/or increasing physical activity may improve NAFLD in the absence of weight loss(Reference Eslamparast, Tandon and Raman73).

While the focus of this review is the role of nutrition and dietary modification, increasing physical activity is an important component of lifestyle change aimed at weight loss and clinical improvement of NAFLD. Randomised clinical trials assessing the effects of resistance training, aerobic exercise or a combination of both have reported improvements in liver enzyme levels and reduced intrahepatic TAG measured by magnetic resonance spectroscopy(Reference Kenneally, Sier and Moore68,Reference Sargeant, Gray and Bodicoat74) . Positive effects have been reported in patients engaging in physical activity only once weekly(Reference Zelber-Sagi, Nitzan-Kaluski and Goldsmith75), and meta-analysis shows this to be independent of significant weight change(Reference Sargeant, Gray and Bodicoat74). Mechanistically this is plausible, as exercise has potent anti-inflammatory effects and protects against many chronic inflammatory diseases(Reference Gleeson, Bishop and Stensel76,Reference Carson77) . Nonetheless, meta-analysis also suggests benefits are substantially greater with weight loss, particularly where weight loss exceeds 7 %; with meta-regression demonstrating reductions in liver fat proportionally related to the magnitude of weight loss induced(Reference Sargeant, Gray and Bodicoat74).

Macronutrient composition and the Mediterranean diet

The benefits of altering macronutrient composition and dietary patterns in NAFLD have been explored. In particular the Mediterranean diet is attractive given the body of evidence suggesting this dietary pattern reduces metabolic risk factors and CVD risk(Reference Rees, Hartley and Flowers78–Reference Estruch, Ros and Salas-Salvado82). On this theoretical basis and only one randomised trial(Reference Ryan, Itsiopoulos and Thodis83) in twelve NAFLD subjects at the time, the European Association for the Study of the Liver Clinical Practice Guidelines made a strong recommendation that, in addition to aiming for a 7–10 % weight reduction, ‘macronutrient composition should be adjusted according to the Mediterranean diet’(7).

Primarily a plant-based diet characterised by high intakes of vegetables, legumes, fruit, nuts and whole grains, along with olive oil as the main source of added fat; the Mediterranean diet is typified by low intakes of dairy and meat products, higher intakes of fish and seafood, and moderate (red) wine consumption. In terms of macronutrients it tends to be much higher in fibre (>33 g/d), lower in carbohydrates, higher in total and monounsaturated fat (approximately 37 % and 18 %, respectively), but lower in saturated fat (9 %) than typical Western diets(Reference Zelber-Sagi, Salomone and Mlynarsky81). As reviewed in detail by Zelber-Sagi(Reference Zelber-Sagi, Salomone and Mlynarsky81) the evidence base for the Mediterranean diet and NAFLD remains limited and largely observational. Nonetheless, the data to date are consistently in favour of a beneficial effect from the Mediterranean diet for treating NAFLD, even without accompanying weight reduction.

Recent work suggests that switching to either an isoenergetic low-fat or Mediterranean diet for 12 weeks, even ab libitum, can reduce liver fat (25 % in low-fat and 32 % in the Mediterranean diet; P = 0·32) and alanine transaminase levels with minimal weight loss (1·6–2·1 kg). The Mediterranean diet did have better adherence and additional cardiometabolic benefits with improvements seen in total cholesterol, serum TAG, haemoglobin A1c and the Framingham risk score(Reference Properzi, O'Sullivan and Sherriff84). While the intervention was not designed for weight loss, and there was no difference in the energetic intakes measured at baseline and 12 weeks, both groups lost a small (2 %) amount of weight, lower than that typically associated with NAFLD improvement. Although no differences were observed in the reductions of liver fat and body weight between the dietary groups, improvements in total cholesterol, plasma TAG and haemoglobin A1c levels were observed in the Mediterranean diet group.

Saturated fat

What both low-fat (<35 %) and the Mediterranean diet often have in common, is reduced (<10 %) saturated fat relative to the Western diet. Although dietary sugars, in particular fructose discussed in the next section, have been scrutinised for their role in driving de novo lipogenesis and NAFLD pathogenesis(Reference Moore, Gunn and Fielding85,Reference Moore and Fielding86) , overfeeding saturated fat is more metabolically harmful to the liver(Reference Luukkonen, Sadevirta and Zhou87). Specifically, using stable isotopes in combination with MRI, Luukkonen and colleagues showed that 3 weeks of overfeeding (4184 kJ/d (1000 kcal/d)) with saturated fat, simple sugars or unsaturated fats increased liver fat by 55, 33 and 15 %, respectively. Furthermore, overfeeding saturated fat-induced insulin resistance and endotoxemia, and increased multiple plasma ceramides(Reference Luukkonen, Sadevirta and Zhou87). The recent focus on the negative metabolic effects of a high sugar diet has led to debate over historical dietary guidelines, which recommend low-fat and low saturated fat diets for the prevention of CVD(Reference Wise88,Reference Teicholz89) . It bears noting that low-fat is considered <35 % of daily energy from fat with an ‘acceptable distribution’ of 20–35 % and low-saturated fat is considered 7–10 % of total energy. In the USA(90) and the UK(Reference Roberts, Steer and Maplethorpe91) adults consume an average of 34–35 % of daily energy intake from fat. As highlighted by Maldonado and colleagues(Reference Maldonado, Fisher and Mazzatti92), neglected in the often polarised debates around sugar or fat(Reference Clifton93,Reference Lim94) , is the fact that at a population level, identifying individual culpable nutrients is problematic. The vast majority of adults in developed countries consume excess energy from foods high in both sugar and fat, fundamentally contributing to increasing obesity and NAFLD. Where low-fat v. low-carbohydrate has been examined in a NAFLD context, the results are similar to that seen in the meta-analysis of weight loss trials in diabetes(Reference Franz, Boucher and Rutten-Ramos72); whereas low carbohydrate may induce a greater weight loss in the short term (12 weeks), in the longer term (≥12 months) the net weight loss tends to be similar to that from low-fat(Reference Kenneally, Sier and Moore68,Reference Katsagoni, Georgoulis and Papatheodoridis71) .

Fructose and dietary sugars

Nonetheless, given the excessive consumption of sugar in general(Reference Moore and Fielding86), messages of reducing sugar-sweetened beverages and added sugars, consuming ‘healthy’ (e.g. complex) carbohydrates alongside lowering saturated fat intakes and consuming more ‘healthy fats’ (e.g. monounsaturated and n-3 FA) seem highly prudent. It is noted that beyond the obvious culprits of sugar-sweetened beverages, biscuits and sweeties or candies, even foods with healthful components such as yoghurts can have surprisingly high amounts of added sugars(Reference Moore, Horti and Fielding95). Lowering intakes of fructose and high glycemic index foods in the diet have been shown to have beneficial effects in NAFLD patients(Reference Mager, Iniguez and Gilmour96, Reference Volynets, Machann and Kuper97). Whereas the European Association for the Study of the Liver Clinical Practice Guidelines specifically suggest ‘exclusion of NAFLD-promoting components (processed food, and food and beverages high in added fructose)(7); the UK guidelines cited a lack of scientific studies meeting their inclusion and exclusion criteria, in not yet making specific recommendations(8). Fructose has been scrutinised because fructose consumption has risen in parallel with obesity, it is metabolised differently by liver and, at high experimental doses, exacerbates obesity and NAFLD(Reference Moore, Gunn and Fielding85). Furthermore, genetic predisposition may make some populations more susceptible to fructose consumption and liver disease than others(Reference Goran and Ventura98).

However, it remains challenging to separate out the effects of specific monosaccharides from the effects of excess energy. The experimental doses typically shown to be lipogenic (20 % total energy) far exceed the population median amounts consumed and individuals rarely consume single sugars in isolation(Reference Moore and Fielding86). When excess energy has been carefully controlled for in randomised controlled human feeding trials, no differential effects are seen between the lipogenic effects of fructose and glucose(Reference Johnston, Stephenson and Crossland99). A systematic review of controlled fructose feeding trials with NAFLD-related endpoints examined thirteen trials in total, including seven isoenergetic trials where fructose exchanged for other carbohydrates and six hyperenergetic trials; diet supplemented with excess energy (21–35 % energy) from high-dose fructose (104–220 g/d)(Reference Chiu, Sievenpiper and de Souza100). It concluded that in healthy participants isoenergeetic exchange of fructose for other carbohydrates does not induce NAFLD changes, however, extreme doses providing excess energy increase steatosis and liver enzymes; in agreement with computational modelling of hepatocyte lipogenesis in response to excess glucose and fructose, described in more detail later(Reference Maldonado, Fisher and Mazzatti92).

There is worldwide agreement on the need to reduce the consumption of dietary sugars to prevent obesity and in particular reduce the consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages to reduce the incidence of type 2 diabetes(Reference Moore and Fielding86). Whereas strict restriction of free sugars (to <3 % of total energy) for 8 weeks has recently been shown to decrease hepatic steatosis in adolescents(Reference Schwimmer, Ugalde-Nicalo and Welsh101), it is not clear in the context of the prevention or treatment of NAFLD, whether public health messages focusing on fructose monosaccharides rather than free sugars and total energy is useful. An overall message should be that given the majority of populations worldwide are consuming too much total sugar, and given the dramatic increase in NAFLD and type 2 diabetes, reducing free sugar intake and choosing a more healthful diet in terms of macro- and micronutrients will be beneficial. Sugar-sweetened beverages in particular, convey an additional risk for type 2 diabetes, most especially in young people, and should be restricted for the prevention of obesity and eliminated altogether in the treatment of existing NAFLD.

Supplemental nutrients: n-3 PUFA, vitamin E and vitamin D

A variety of vitamins and micronutrients have been implicated in NAFLD pathogenesis. This is either because of epidemiological data associating a deficiency with disease or because of plausible anti-steatotic, anti-inflammatory or anti-fibrotic mechanisms that (a supplemental dose of) dietary nutrients or other components may confer in a disease state.

NAFLD patients have been shown to have lower intakes of fish(Reference Zelber-Sagi, Nitzan-Kaluski and Goldsmith102) and n-3 PUFA(Reference Musso, Gambino and De Michieli103) in comparison with controls and therefore PUFA supplementation has been explored. Two independent groups have systematically reviewed controlled intervention trials that examined n-3 FA supplementation for the treatment of NAFLD(Reference Musa-Veloso, Venditti and Lee104,Reference Yan, Guan and Gao105) . Both meta-analyses included eighteen independent trials with >1400 participants and concluded that supplementation of n-3 PUFA reduced steatosis as measured by ultrasound or MRI, and liver enzymes(Reference Musa-Veloso, Venditti and Lee104,Reference Yan, Guan and Gao105) . Disappointingly, in the four trials that examined histological markers, n-3 PUFA supplementation did not improve inflammation, ballooning or fibrosis(Reference Musa-Veloso, Venditti and Lee104). Strikingly, responders and non-responders to supplementation that correspond to improvements in liver markers were clearly evident in the well-designed trial by Scorletti and colleagues(Reference Scorletti, Bhatia and McCormick106). As discussed later, personalised nutrition for the prevention of chronic disease in the near future might account for such inherent (through genetic, epigenetic or microbiome mechanisms) inter-individual variation.

Vitamin E is a powerful antioxidant that helps protect cells against free radical damage, one of the pathogenic insults that drives NAFLD progression. There have now been several well-designed multi-centre trials in both adults and children examining vitamin E supplementation at pharmacological doses that could not be obtained through diet(Reference Perumpail, Li and John107). Several meta-analyses show benefit from supplemental vitamin E on steatosis, inflammation and ballooning in NASH, although the extent to which vitamin E benefits fibrosis remains unclear(Reference Singh, Khera and Allen108–Reference Said and Akhter110). Consequently, UK, EU and US clinical guidelines indicate vitamin E as a therapeutic option once a patient is in second or tertiary care for NASH(Reference Chalasani, Younossi and Lavine1,7,8) , but with the awareness of potential risks for long-term vitamin E supplementation(Reference Perumpail, Li and John107). Recommended doses are typically 800 IU/d as opposed to recommended nutrient intakes of ≤15 mg/d (22·4 IU/d) in the UK. While the American guidelines specify vitamin E only for NASH patients without diabetes(Reference Chalasani, Younossi and Lavine1), the UK guidelines consider vitamin E an option for patients with and without diabetes(8).

A growing body of research suggests a relationship between vitamin D deficiency and chronic liver disease, in particular NAFLD, with low levels of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D strongly associated with hepatic inflammation(Reference Kitson and Roberts111–Reference Eliades, Spyrou and Agrawal113). Low levels of dietary vitamin D(Reference Gibson, Lang and Gilbert114) and serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D are widespread, and vitamin D deficiency and insufficiency have been observed in pediatric NAFLD(Reference Gibson, Quaglia and Dhawan115). In addition, polymorphisms within vitamin D metabolic pathway genes associate with the histological severity of pediatric NAFLD(Reference Gibson, Quaglia and Dhawan115). However, the results of oral vitamin D supplementation trials on adult NAFLD patients are conflicting(Reference Barchetta, Cimini and Cavallo116,Reference Sharifi and Amani117) . Some studies have demonstrated a correlation between NAFLD and NASH severity and lower levels of vitamin D(Reference Nelson, Roth and Wilson118). However, others, including a meta-analysis with 974 adult patients find no such relationships(Reference Bril, Maximos and Portillo-Sanchez119,Reference Jaruvongvanich, Ahuja and Sanguankeo120) .

The determinants of 25-hydroxyvitamin D bioavailability are complex; genetic variation determines serum levels of vitamin D binding protein thus influencing bound and free 25-hydroxyvitamin D(Reference Powe, Evans and Wenger121). Inter-individual vitamin D concentrations are highly variable and the degree to which they change over the decades through which NAFLD may progress, is unknown. The mechanisms behind the role of vitamin D in NAFLD pathogenesis are not yet fully understood and there are likely to be both hepatic and extra-hepatic mechanisms involved. Interestingly, vitamin D has been shown to have antifibrotic effects in both rodent(Reference Abramovitch, Dahan-Bachar and Sharvit122,Reference Ding, Yu and Subramaniam123) and human(Reference Beilfuss, Sowa and Sydor124) HSCs. While there are clearly likely to be multiple pathways to fibrogenesis in NAFLD(Reference Skoien, Richardson and Jonsson125), together these studies show a role for vitamin D in liver disease pathogenesis and suggest common polymorphisms influencing vitamin D homeostasis may be relevant to NAFLD. Although supplementation with vitamin D has not been demonstrated an effective intervention in the limited studies done in adult patients with NAFLD to date; further research is warranted into whether targeted supplementation, either in genetically susceptible or pediatric populations may be indicated.

While data from large well-controlled trials are limited, it may be that classical intervention trials for single nutrients are doomed to fail in light of the high inter-individual genetic variation in the metabolism of many of these nutrients; in combination with individual epigenetic, microbiome and environmental, namely dietary, effects. As illustrated for n-3 supplementation(Reference Scorletti, Bhatia and McCormick106), population studies will include non-responders that may mask the positive (or negative) effects of dietary supplements in others. As will be discussed, the goal of personalised nutrition is to stratify dietary intervention according to such genetic, ‘omic’ and clinical information in the first instance to maximise therapeutic benefit.

Systems biology

Systems biology is the application of mathematical or computational modelling to biological systems, and has evolved as a complementary method of understanding a biological organism. Reflecting its roots in mathematical graph theory, cybernetics and general systems theory; within systems biology, biological systems, whether a signalling network, a cell, an organ, or an organism, are visualised and modelled as integrated and interacting networks of elements from which coherent function emerges(Reference Moore and Weeks126). As illustrated in Fig. 3(a), from a systems point of view, a human may be deconstructed into a series of networks at organ, cellular and the molecular or genetic levels; equally, human subjects are parts within larger social networks. Underpinning systems biology are advanced mathematical theory and computational approaches that aim to model organism function and predict behaviour. Early in its evolution, computational systems biology was envisioned as working best if integrated into an iterative cycle of model development and prediction, with experimental (‘wet lab’) investigation and model refinement (Fig. 3(b))(Reference Kitano127). This iterative cycle moves from hypothesis-led experiments generating data that can both yield biological insights, and can be further utilised in the reconstruction of mathematical network models (such as the extended Petri net model of insulin signalling illustrated in Fig. 3(c)) for predictive simulation, model refinement and more biological insight that informs further experimental hypotheses.

Fig. 3. Systems biology and systems medicine. (a) Human subjects may be deconstructed into a series of networks at genetic, molecular, cellular and organ levels; equally, human subjects are places within larger social networks. (b) Systems biology ideally is an iterative cycle from hypothesis-led experiments generating data that can both yield biological insights, and can be further utilised in the reconstruction of mathematical models for predictive simulation, model refinement and more biological insight that informs further experimental hypotheses. (c) A kinetic network model of insulin signalling reconstructed in a Petri net formalism, reprinted with permission(Reference Maldonado, Fisher and Mazzatti92). Coloured ovals highlight modules used by Kubota and colleagues(Reference Kubota, Noguchi and Toyoshima152). (d) Systems medicine and systems pharmacology integrate genetic, clinical and ‘omic’ data into network models, representing an in silico human, that can yield emergent insights. For example, simulations may predict responders/non-responders to a drug or identify mechanisms of action underpinning drug off-target effects.

Systems medicine and personalised nutrition

Systems pharmacology and systems medicine are subtypes of systems biology underpinning present efforts in what has been alternately termed stratified, personalised or precision medicine(Reference Stephanou, Fanchon and Innominato128). Emerging out of the genomics revolution, came the recognition that whereas presently used pharmaceuticals are based on clinical trials involving large cohorts, these neglect the underlying genetic and environmental heterogeneity represented within the population. This heterogeneity explains the existence of responders and non-responders to drug intervention, as well as drug off-target effects. Precision medicine aims for the stratification of patients into tightly molecularly defined groups (based on multiple types of ‘omics’ data), with effective interventions or treatments defined for each(Reference Nielsen129). While presently used stratified medicines are largely within the cancer field and rely on genetic testing of a relatively limited number of genes, ultimately it is envisioned that the integrative analyses of different types of data: clinical, genomic, proteomic, metabolomic; will yield system insights (Fig. 3(d)). Beyond the genomic vision of stratified medicine, systems medicine in its grandest vision, has been described as personalised, predictive, preventive and participatory medicine (4P medicine) and intriguingly perhaps for Nutritional Scientists, has an aim of quantifying wellness in addition to understanding disease(Reference Hood, Heath and Phelps130,Reference Hood and Flores131) .

Arguably, the Nutritional Sciences are ideal for the use of systems approaches given the complex, dynamic nature of diet where small effects may be magnified on a chronic time scale; and furthermore, occur against a backdrop of tremendous genetic diversity both of human subjects and their intestinal microbiomes(Reference de Graaf, Freidig and De Roos132). The vision and aim of personalised nutrition mimics that of personalised medicine, e.g. tailoring diets in a way that optimises health outcomes for the individual based on their ‘omics’ data(Reference Ordovas, Ferguson and Tai133). Presently it is estimated only 40 % of a cohort may respond to a dietary intervention; analogous to observed nonresponse or off-target effects to pharmaceutical compounds. This is attributed to inter-individual variation in a host of variables (sex, habitual dietary habits, genetics, epigenetics and gut microbiota) effecting individual absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion of compounds and metabolites(Reference de Roos and Brennan134). Personalised nutrition therefore, presents both grand opportunities and challenges; e.g. how to capture small, accumulative factors that only manifest into disease over a matter of years, while distinguishing differential effects of one nutritional component from hundreds of others(Reference Grimaldi, van Ommen and Ordovas135).

Modelling liver metabolism

In more recent years, systems biology approaches have been applied to human metabolism at the genome scale. Genome-scale metabolic networks (GSMNs) may be thought of as essentially an organised list of metabolic reactions derived from all available data of an organism's metabolism into a mathematically structured network. Constraint-based flux balance analysis is used to predict metabolic fluxes in silico, while the GSMN is constrained mathematically based on experimental data sets. The liver as an organ is central to both human metabolism and overall homeostasis; and the first liver-specific GSMNs were published in 2010(Reference Jerby, Shlomi and Ruppin136,Reference Gille, Bölling and Hoppe137) . While one of these was derived from a generic GSMN by automated methods integrating tissue-specific datasets(Reference Jerby, Shlomi and Ruppin136); the HepatoNet1 model presented by Gille and colleagues(Reference Gille, Bölling and Hoppe137) was based on exhaustive manual curation of transcript, protein, biochemical and physiological data and contains 2539 reactions and 777 individual metabolites.

More recently, the liver-specific iHepatocytes2322(Reference Mardinoglu, Agren and Kampf138) was reconstructed, comprising 7930 reactions, 2895 unique metabolites in eight different compartments mapped to 2322 genes. This was done in semi-automated fashion but, significantly, utilised proteomics expression data from hepatocytes from the Human Protein Atlas(Reference Uhlen, Oksvold and Fagerberg139) to establish tissue specificity. This incredibly comprehensive reconstruction paid particular attention to manual curation of reactions involving lipids. Both the HepatoNet1 and iHepatocytes2322 GSMNs have been utilised in the context of NAFLD related research. While GSMNs continue to evolve as powerful tools, it is important to note that metabolism is only one of the many networks considered in systems biology (Fig. 3(a)) and flux balance analysis is limited in being static and not reflecting the dynamic metabolic response to altered cell signalling. A very active area of systems research is focused on developing novel tools and algorithms for integrating and simulating models at multiple scales and linking GSMNs to gene regulatory networks and/or physiologically based pharmacokinetic models in systems pharmacology/toxicology and kinetic signalling networks(Reference Fisher, Plant and Moore140–Reference Maldonado, Leoncikas and Fisher142).

Application of systems approaches to non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

It has only been in very recent years that GSMNs have been used along with relevant omics data in the context of NAFLD. The aforementioned iHepatocytes2322(Reference Mardinoglu, Agren and Kampf138) was reconstructed specifically to interrogate liver transcriptomic data from nineteen healthy subjects and twenty-six patients with varying degrees of NAFLD. Using a metabolite reporting algorithm, a pair-wise comparison was used to identify reporter metabolites. Network subgroup analyses predicted disruptions in the non-essential amino acids: serine, glutamate and glycine (along with others), along with metabolites in the folate pathway related to the interconversion of serine, glycine and glutamate. Phosphatidylserine, an essential component of lipid droplets was also identified as disrupted, with the mRNA for enzymes involved in its synthesis found downregulated in the NASH patients. Similarly, several enzymes that either use serine as substrate or produce it as a product were transcriptionally downregulated. Collectively, the authors inferred an endogenous serine deficiency and suggested serine supplementation as a possible intervention in NASH. Chondroitin and heparin sulphate levels were also identified as potential NAFLD biomarkers, although these have not yet been independently validated.

Impressive follow up work from the same group has now shown in an untargeted metabolomics analysis of individuals with either low (mean 2·8 %, n 43) or high (mean 13·4 %, n 43) liver fat as measured by MRI, decreased levels of plasma glycine and serine, along with betaine and N-acetylglycine associated with higher levels of steatosis(Reference Mardinoglu, Bjornson and Zhang143). In addition to the metabolomic measurements, in vivo VLDL kinetics were measured via stable isotope infusion in seventy-three of the individuals. These experimentally measured VLDL secretion rates along with individually defined NEFA uptake rates (based on body composition and secretion rates of NEFA from adipose and muscle) were used to constrain the iHepatocytes2322 GSMN. The resulting personalised GSMNs were then simulated using the secretion rate of VLDL as an objective function in order to identify hepatic metabolic alterations between individuals with high and low steatosis. Liver fluxes were predicted for each subject and several reactions, consistent with an increased demand for NAD+ and glutathione, correlated to steatosis and net fat influx.

Relating this back to amino acid precursors and the lower levels of plasma serine and glycine, in a proof-of-concept study in six subjects with obesity, Mardinoglu and colleagues observed both a decrease in liver fat (mean 26·8 to 20·4 %) and aspartate and alanine transaminase levels after 14 d of serine supplementation (about 20 g of l-serine, 200 mg/kg/d)(Reference Mardinoglu, Bjornson and Zhang143). The authors suggest serine could be combined with N-acetylcysteine, nicotinamide riboside and l-carnitine as a supplement to aid in mitochondrial FA uptake and oxidation and increased generation of glutathione may have benefit for either the prevention or treatment of NASH. While pilot trials have examined N-acetylcysteine(Reference Pamuk and Sonsuz144,Reference Khoshbaten, Aliasgarzadeh and Masnadi145) and l-carnitine(Reference Malaguarnera, Gargante and Russo146,Reference Somi, Fatahi and Panahi147) supplementation in NAFLD separately with mixed results, they have not been examined in combination. Amino acid disturbances, particularly to glutamate, serine and glycine continue to be explored in relation to NAFLD liver disease severity in different populations(Reference Yamakado, Tanaka and Nagao148,Reference Gaggini, Carli and Rosso149) . Returning to the ideas of systems medicine and personalised nutrition, and the example of responders and non-responders to n-3 supplementation, an open question is whether or not a subgroup of NAFLD patients are likely to benefit (respond) to such intervention more than others. It is hoped with advances in systems biology the identification of such patient subgroups will be feasible in the near future.

Other work has also integrated transcriptomic data with experimentally measured in vivo flux measurements from NAFLD patients(Reference Hyotylainen, Jerby and Petaja150) utilising a GSMN. Hyötyläinen and workers used Recon1 and measured flux ratios of metabolites and bile acids across the hepatic venous splanchnic bed in nine subjects with NAFLD that were fasted and then underwent euglycemic hyperinsulinemia. The work developed a metabolic adaptability score and found steatosis is associated with overall reduced adaptability. Steatosis induced mitochondrial metabolism, lipolysis and glyceroneogenesis; plus, a switch from lactate to glycerol as a substrate for gluconeogenesis. In this, and the work of Mardinoglu and colleagues, GSMNs were utilised for the mechanistic interpretation of clinical (transcriptomic and metabolomic) NAFLD data. However, these models are static, reflecting liver adaptation at an endpoint and do not give insight into the dynamic reprogramming of global metabolism and metabolic adaptation to maintain homeostasis in response to stimulation as recently addressed by Maldonado and colleagues(Reference Maldonado, Fisher and Mazzatti92).

Building on their previous work establishing the use of quasi-steady state Petri nets to integrate and simulate gene regulatory networks and/or physiologically based pharmacokinetic models with constraint-based GSMNs(Reference Fisher, Plant and Moore140–Reference Maldonado, Leoncikas and Fisher142); the group has developed novel multi-scale models to predict the hepatocyte's response to fat and sugar(Reference Maldonado, Fisher and Mazzatti92). In one case, from experimental -omics data and the literature, they manually curated a comprehensive network reconstruction of the PPARα regulome. Integrated to the HepatoNet1(Reference Gille, Bölling and Hoppe137) GSMN, the resulting multi-scale model reproduced metabolic responses to increased FA levels and mimicked lipid loading in vitro. Adding to the conflicting literature on the role of PPARα in NAFLD, the model predicted that activation of PPARα by lipids produces a bi-phasic response, which initially exacerbates steatosis(Reference Maldonado, Fisher and Mazzatti92). The data highlight potential challenges for the use of PPARα agonists to treat NAFLD and illustrate how dynamic simulation and systems approaches can yield mechanistic explanations for drug off-target effects. While the PPARα regulome module was sufficiently large to preclude complete deterministic parameters for every reaction; illustrating the flexibility of quasi-steady state Petri nets, the authors also simulate a kinetic multi-scale model of monosaccharide transport and insulin signalling integrated to the HepatoNet1 GSMN. Interestingly, while the model predicted differential kinetics for the utilisation of glucose and fructose, TAG production was predicted to be similar from both monosaccharides. This finding is supported both by the author's experimental data presented alongside the simulations(Reference Maldonado, Fisher and Mazzatti92), as well as other clinical and intervention data(Reference Johnston, Stephenson and Crossland99,Reference Chiu, Sievenpiper and de Souza100) . These data imply that it is the quantity, not type of sugar that drives fat accumulation in liver cells and NAFLD per se.

The focus here has been on reviewing recent work applying the simulation of GSMNs in NAFLD-related research. Computational approaches and network reconstructions are rapidly evolving and present models have strengths and weaknesses that will resolve in future iterations. More work is needed comparing results from different reconstructions and establishing the best choice(s) of objective functions for human applications. Integrating constraint-based analyses of GSMNs with whole body physiologically based pharmacokinetic models or gene regulatory and signalling network models in multi-scale fashion for dynamic simulations and insights into pathogenesis over time is a present research goal.

Conclusions

The interdisciplinary methods of systems biology are rapidly evolving and have recently been applied to the study of NAFLD. Technology too is quickly advancing and a not too distance future is envisioned where individual genetic, proteomic and metabolomic information can be integrated computationally with clinical data. Ideally this will inform personalised nutrition and precision medicine approaches for improving prognosis of chronic diseases such as NAFLD, obesity and type 2 diabetes. Several genetic variants mediating susceptibility to liver diseases have been identified and validated, opening up possibilities for the use of polygenic risk scores to stratify patients once the disease is identified. Progression of NAFLD is dependent on environmental factors and it should be stressed that NAFLD is reversible through lifestyle change. As has recently been argued for type 2 diabetes, a systems disease requires a ‘systems solution’(Reference van Ommen, Wopereis and van Empelen151). While intervention studies demonstrate that high-intensity combination interventions, including behaviour change alongside dietary and lifestyle change, are most efficacious for treating NAFLD; undoubtedly, broader societal systems-level changes are urgently required to reduce the present burden and prevent obesity and related morbidities such as NAFLD and type 2 diabetes going forward.

Acknowledgements

The author is grateful to both Dr Anna Tanczos, for her translation of author's vision for these figures, and Dr James Thorne, for his critical review of this manuscript in its final stages. A special thank you goes to Dr Elaina Maldonado for both the Petri net in Fig. 3(c) and multiple conversations over many years that contributed to the realisation of Fig. 2 and several discussion points made herein. In addition, the author wants to sincerely thank all the students, early career researchers and collaborators with whom the author has had the pleasure of working with over the past 10 years.

Financial Support

Some of the work reviewed here from J. B. M. was made possible through funding from the UK Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council, including a studentship grant (BB/J014451/1 for Dr Elaina Maldonado) and the project grant (BB/I008195/1). The support of both the University of Surrey and the University of Leeds is also acknowledged.

Conflict of Interest

None.

Authorship

J. B. M. had sole responsibility for all aspects of the preparation of this paper.