I. Introduction

Law relies on language, and language is nothing but the practical use of its constituent words, noted the German philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein in one of his most famous philosophical treatises, the Philosophical Investigations ([1953] Reference Wittgenstein and Schulte2003, § 43). When lawyers interpret some text, a statute, for example, they use other texts as contextualization cues. Their methods of interpretation are qualitative, based on introspective inquiry into their particular knowledge about law. But what does it mean to ground interpretation (only) in introspection? With the number of legal texts growing day by day, how can we keep track of the “most relevant” legal texts and not just, for example, the most cited ones? How can we check our implicit assumptions and inferences in legal interpretation and make them (more) transparent (see Stein and Giltrow forthcoming)? How can we reduce ambiguity in drafting legal texts?

This article introduces computer-assisted legal linguistics (CAL2), an area of study ranging from computer-supported qualitative analysis of legal texts to legal semantics and legal sociosemiotics based on big data. It requires an interdisciplinary cooperation between lawyers, (computational) linguists, and computer scientists. In the following sections, after a short characterization of jurisprudence as a text-based institution (Section II), we argue that corpus linguistics can help to analyze legal discourse based on empirical data (Section III). We illustrate how certain research areas could benefit from, and simultaneously test the practical potential of, this approach (Section IV). We then present a number of existing corpora of legal texts worldwide and discuss their limitations (Section V). Then, we introduce a new set of legal reference corpora, namely, the CAL2 Corpus of German Law (Juristisches Referenzkorpus, JuReko) and the CAL2 Corpus of British Case Law, both of which lay the foundation for a CAL2 Corpus of European Law (Section VI). We conclude by summarizing the potentials and pitfalls of CAL2 and by suggesting further research directions (Section VII).

II. Legal Linguistics

A. Legal Norms Are Created, Not Found

Linguistics and legal studies, taken at face value, are different disciplines, but both, in fact, work with language, differing merely in their respective focus: linguists explore language for its own sake, that is, to describe texts and to model linguistic phenomena. Lawyers, instead, use language to negotiate legal norms, that is, they seem to employ texts—statutes, opinions, and so forth—only as a “vehicle” for legal norms. This implicit “saucepan conception” of language has long been derided as overly simplistic (Busse Reference Dietrich1992, 14). The kinship between law and language is actually more complex and more fundamental.

“Our law is a law of words” (Tiersma Reference Tiersma1999, 1), and the opposite of a law of words is not a voiceless law, but one of violence, of “might makes right.” Modern constitutional democracies bar violence, so law is predominantly text and language. It forms a fabric of intertextual cross-references (Müller, Christensen, and Sokolowski Reference Müller, Christensen and Sokolowski1997; Morlok Reference Morlok, Blankenagel, Pernice and Kotzur2004), woven by lawyers who use language as their working instrument and who connect texts that carry specific institutional functions (Funktionstexte) with other such texts from various domains: statutes with prior court decisions, academic treatises, opinions of nonlegal experts, and, of course, texts describing the alleged real facts at stake.

Legal language, as a professional variety, differs from language used in everyday life (see Jeand'Heur Reference Jeand'Heur, Hoffmann, Burkhardt, Ungeheuer, Wiegand, Steger and Brinker1998; Tiersma Reference Tiersma1999). Critics often complain about what they see as the incomprehensibility of legal language and emphasize that law has to be intelligible to all (see Adler Reference Adler, Tiersma and Solan2012), but these critics underestimate the specific function of legal language: it is the medium to transform nonlegal subjects and schemata—vague cognitive concepts about everyday life—into legal thinking, argumentation, and working procedures (see the discussion in the Washington University Law Quarterly 1995).

Legal norms are not abstract entities in a metaphysical sphere, but are instead subject to individual decision makers’ intuitions. What European scholars call “subsuming” (Latin for taking under) cases “under” a law or normative text is, in fact, a work of processing texts. Norms have to be “performed” by concrete actors, and have to be construed actively by working with and on statutory (or preceding judicial) texts. Compare this to the art of sculpting (Hamann forthcoming): even though Michelangelo is quoted as saying that he merely freed preexisting angel figurines from their marble confines, the creative and constructive nature of his art can hardly be denied. Similarly, legal interpretation requires human work, individual actions, habitus, attitudes, stereotypes, and so forth. Legal norms are complex cognitive concepts and are not just contained “inside” a statute or judgment. Lawyers actively construct norms by contextualizing words with related lexical items, phrases, and passages to make them meaningful (Hörmann Reference Hörmann and Kühlwein1980; Gumperz Reference Gumperz1982, 131). In other words, they “ascribe a norm to a legal text” (Vogel Reference Vogel2015, 7).

B. A Constructionist Model of Legal Interpretation

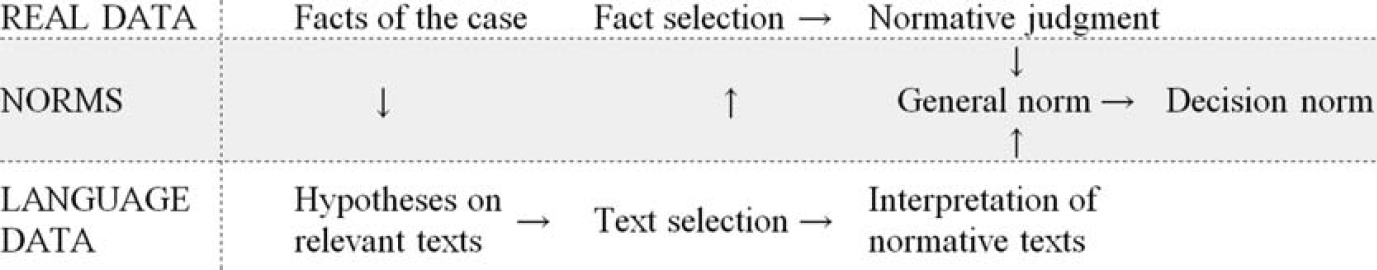

In Europe, especially when working with statutory law, this view on constructing law and legal norms challenges traditional positivist theories. Many legal scholars disagree with legal linguists’ talk about the active role of interpreters, and with their call for heightened methodological self-reflection (and therefore transparency) in legal argumentation. They seem to equate “norm construction” with advocacy for arbitrary meanings that replace the authority of “the” statute. Such fundamentalist criticisms, and an alternative model for the process of ascription, were addressed in detail in an influential theory on the interaction of law and language that originated in Germany in 1963 and has since infused legal theorizing in France, Spain, South Africa, and Brazil while still claiming to be a “work in progress”: Friedrich Müller's ([1984] Reference Müller1994) Structuring Legal Theory (Strukturierende Rechtslehre). It distinguishes three epistemological realms connected by the structural model in Figure 1 (Hamann forthcoming).

Figure 1. Structural Model of Three Epistemological Realms

This model emphasizes that legal cases cannot be (and are not) decided on the grounds of preexisting normative notions. Instead, normative guidance derives from a multistep procedure oscillating between two types of text, one describing the real events, and the other prescribing rules, until it settles on a norm stated specifically enough to apply to the case (for a similar analytical distinction between texts and norms, see Shecaira Reference Shecaira2015). The model thus attributes paramount importance to the language involved and to the role of argumentation in each of these steps, thereby letting judgment depend on linguistic usage patterns. This is true for the continental European system of applying general statutes to specific cases, just as it is true for the Anglo-American system of applying precedents to later cases (Müller Reference Müller2000, 426). Both systems “apply” normative notions they derive from the aforementioned epistemological oscillation, even if this is not usually made explicit.

C. Legal Linguistics as a Trans-Discipline

The relationship between law and language both on a systematic and a pragmatic level is the mainstay of legal linguistics (for an overview, see Müller Reference Müller1989, Reference Müller2001; Tiersma Reference Tiersma1999; Lerch Reference Lerch2004, Reference Lerch2005; Tiersma and Solan Reference Tiersma and Solan2012; Freeman and Smith Reference Freeman and Smith2013; Mattila Reference Mattila2013; Felder and Vogel forthcoming). This is a trans-discipline of law and linguistics that has recently started to receive institutional support from the International Language and Law Association (ILLA; see www.illa.online). Its members occasionally have degrees in both linguistics and law, and they explore how language constitutes law in legislation, adjudication, administration, and jurisprudence (research and teaching). Some of its topics include history of and variation in the lexicon, text and genre of law, law as a structure of multimodal signs and a network of texts, legal interpretation methods, implicit speech theories in legal practice, discourse in the courts, improving the comprehensibility of legal texts, methods and language of conflict resolution (e.g., mediation or arbitration), and linguistic human rights (for a comprehensive overview, see Tiersma and Solan Reference Tiersma and Solan2012; Vogel forthcoming b).

This notion of legal linguistics overlaps with the competing expression “forensic linguistics,” especially in Anglo-Saxon research contexts. In German-speaking countries, forensic linguists (forensische Linguisten) analyze the usage of everyday speech varieties to inform (mostly criminal) court proceedings and policing, often as expert witnesses, for example, for author identification or comparison (see Kniffka Reference Kniffka2007; Fobbe Reference Fobbe2011). Despite the fact that both research directions can and should benefit from each other, we prefer to distinguish them analytically and to exclude forensic linguistics in this narrow sense from our review.

III. Computer-Assisted Legal Linguistics

While the interrelation between law and language has long been analyzed theoretically, both disciplines have witnessed a recent surge in empirical methods. The empirical approach to law and language is a crossroads between at least two major avenues of research (Hamann and Vogel forthcoming).

One avenue departs from the camp of linguists and media theorists. Having traditionally been a stronghold of reflective thinkers of the Chomsky or McLuhan variety, the rise of modern Internet media gave linguists a powerful new research tool: For the first time ever, huge masses of text have become available in digital formats, with software powerful enough to analyze this wealth of material. Text has become data, and the qualitative approach to intuitive semantics has found its complement in the quantitative approach to usage patterns. This is reflected in the computer linguistics movement with its offspring corpus linguistics (Kučera et al. Reference Kučera, Nelson Francis, Freeman Twaddel, Bell, Carroll and Marckworth1970; ICAME News 1978; Fillmore Reference Fillmore1992; Teubert Reference Teubert2005), specifically geared toward analyzing large bodies of text. With several journals now dedicated to this field (e.g., International Journal of Corpus Linguistics, Corpora, Corpus Linguistics and Linguistic Theory), most of its infrastructure has been in place for about twenty years (the International Journal of Corpus Linguistics was established in 1995, and McEnery and Wilson published their textbook in 1996; see also Lüdeling and Kytö Reference Lüdeling and Kytö2008). This research has also made its way into studies of law (Bhatia, Langton, and Lung Reference Bhatia, Langton, Lung, Connor and Upton2004; Kredens and Goźdź-Roszkowski Reference Kredens and Goźdź-Roszkowski2007; Goźdź-Roszkowski Reference Goźdź-Roszkowski2011; Mouritsen Reference Mouritsen2010, Reference Mouritsen2011; Vogel Reference Vogel, Felder, Müller and Vogel2012a, Reference Vogel2015; Vogel, Christensen, and Pötters Reference Vogel, Christensen and Pötters2012), thus intersecting with another new strand of research.

This other strand, protruding from the fortress of legal scholarship, emancipates from classical dogmatic lawyering in much the same way that corpus linguists try to complement work by the sages of media theory. Whereas lawyers traditionally relied on an intuitive grasp of social reality, the new legal empiricists turn to data and statistical analysis. After early attempts—such as legal realism in the United States and legal sociology (Rechtssoziologie) in Germany—which failed to develop a sustainable policy impact, the new legal realism and empirical legal studies movements (for an overview, see Suchman and Mertz Reference Suchman and Mertz2010; for current perspectives, see Zeiler Reference Zeiler2016) have established a considerable foothold in legal academia. With the Journal of Empirical Legal Studies (JELS) shooting to prominence within very few years since its inception in 2004, and the eponymous society (SELS) and its annual conference (CELS) now in the twelfth installment and extending overseas (CELS Europe in Amsterdam in 2016, CELS Asia in Taipei in 2017), and with a proliferation of textbooks and handbooks (Cane and Kritzer Reference Cane and Kritzer2010; Lawless, Robbennolt, and Ulen Reference Lawless, Robbennolt and Ulen2010; Chang Reference Chang2013; Epstein and Martin Reference Epstein and Martin2014; Leeuw and Schmeets Reference Leeuw and Schmeets2016), this new field is rapidly maturing. It, too, has arrived at the crossroads with big data linguistics rather recently (Evans et al. Reference Evans, McIntosh, Lin and Cates2007; Macey and Mitts Reference Macey and Mitts2014; Fagan Reference Fagan2015, Reference Fagan2016; Hamann Reference Hamann and Vogel2015; Law forthcoming; Solan and Gales forthcoming).

What unites both approaches from different fields is, in substance, their joint interest in institutions and how power originates in language and discourse, and, methodologically, their conversion from eminence- to evidence-based thinking (Hamann Reference Hamann2014a, Reference Hamann2014b). Joining forces, these approaches have resulted in a new subfield that is best described as computer-assisted legal linguistics (CAL2) (Vogel et al. Reference Vogel, Hamann, Stein, Abegg, Biel and Solan2012; Hamann, Vogel, and Gauer Reference Hamann, Vogel and Gauer2016) and analyzes law—that is, its language, semantics, knowledge structure, and discourse patterns—as a social practice, employing both corpus-driven (exploratory) and corpus-based (inferential) strategies (see Vogel Reference Vogel2015). Practical examples of such work were discussed at two international conferences in 2016: in March, a conference on “Discovering Patterns Through Legal Corpus Linguistics” at Heidelberg, Germany (see Section VI), and in April, the inaugural “Law and Corpus Linguistics Conference” at BYU Law in Provo, Utah (see lawcorpus.byu.edu). These conferences led to follow-up events in 2017: on February 3, the “Symposium on Law and Corpus Linguistics,” again at BYU Law, and on September 8, the ILLA session on “Corpus Linguistics and Hermeneutics in Legal Linguistics” at Freiburg, Germany (see Section VI).

CAL2 connects the micro perspective of individual cases and legal arguments with the macro perspective of normative structure and patterns in legal argumentation, using both qualitative and quantitative analysis. It does not, however, attempt to read law as a cybernetic circuit or to convert legal rules into machine-readable algorithms. Instead, it explicitly restricts the role of computers to assisting, not replacing, hermeneutic inquiry. As a result, CAL2 helps to promote better understanding of the fundamentals of law and language, to improve lawyering in the courts, and to inform legislators on how best to draft regulations.

IV. Applications in Adjudication, Education, Research, and Legislation

The suggested potential of CAL2 is best illustrated by looking at specific areas of application. The following sections present a selected sample (but are not intended as an exhaustive list) of applications.

A. Semantics and Legal Interpretation

A recurring issue in statutory interpretation all over the world is that of determining a statute's meaning. In virtually all legal systems, “the law” consists first and foremost of a body of black-letter print that has been granted authority (Geltung) as a result of being formally enacted by some orderly procedure. But what do any such authoritative letters and the resulting words and sentences mean? The linguistic challenges plaguing this inquiry are legion (see Solan Reference Solan, Tiersma and Solan2012, 87). Setting aside the additional question of which vantage point in time is relevant for interpreting a text (the originalism debate—for a corpus-related account, see Phillips, Ortner, and Lee Reference Phillips, Ortner and Lee2016; Solan Reference Solan2016), we basically find three approaches for determining meaning among the judiciary (Hamann Reference Hamann and Vogel2015; Solan and Gales forthcoming).

One approach is unfettered intuition. Judges, by virtue of being native speakers, may feel legitimized to “sense,” if you will, the meaning of any printed word (Hoffman Reference Hoffman2003). In some instances, they may even feel compelled to do so under what is known as the “plain meaning rule.” This rule may have been most clearly stated in the case of Connecticut National Bank v. Germain (1992, 253–54): “canons of construction are no more than rules of thumb that help courts determine the meaning of legislation, and in interpreting a statute a court should always turn first to one, cardinal canon before all others … courts must presume that a legislature says in a statute what it means and means in a statute what it says there. When the words of a statute are unambiguous, then, this first canon is also the last: ‘judicial inquiry is complete.’” The plain meaning rule thus forbids reference to evidence outside the judge's language intuition, that is, external evidence (Tiersma Reference Tiersma1999, 126; Mouritsen Reference Mouritsen2011, 163). Given that judges are participants and never observers of their language community, this approach inevitably involves an arbitrary element. The case has often been made (Lamm Reference Lamm2009; Bindman and Monaghan Reference Bindman and Monaghan2014; Hamann Reference Hamann and Vogel2015) and barely needs repeating that judges are a small minority of language users, selected from a particular pedigree, a particular professional elite, and a particular income stratum, with no privileged access to “the language” of their entire people.

Another, seemingly more objective, approach to determining the meaning of legal texts is to use dictionaries (e.g., Scalia and Garner Reference Scalia and Garner2013) or, more generally speaking, static texts that are intended to fix or ascertain the meaning of other texts. This description already reveals the inherent circularity of this approach. Unsurprisingly, an entire cottage industry (“a robust literature, almost entirely critical,” Solan and Gales forthcoming) revolves around analyzing the use of dictionaries in courts, never failing to criticize their limitations and ultimate uselessness for the task of determining meaning (Solan Reference Solan1993; Randolph Reference Randolph1994; Aprill Reference Aprill1998; Thumma and Kirchmeier Reference Thumma and Kirchmeier1999; Hoffman Reference Hoffman2003; Lobenstein-Reichmann Reference Lobenstein-Reichmann and Müller2007; Mouritsen Reference Mouritsen2010; Hobbs Reference Hobbs2011; Brudney and Baum Reference Brudney and Baum2013, Reference Brudney and Baum2015; Calhoun Reference John2014). By now, even senior federal judges have acknowledged this criticism (e.g., Judge Posner in United States v. Costello 2012, 5–7). In Germany, where similar attacks abound, Hamann (Reference Hamann and Vogel2015, 199) mocked the continued reliance on dictionaries as a form of pseudo-linguistic cookbook epistemology: “[Dictionaries] do not allow for any assessment of the ‘commonness’, ‘ordinariness’ or ‘normality’ of usages. If you wanted to derive from dictionaries more than a vague indication of how people might use language, you might just as well try to derive from cookbooks what people [actually] eat for lunch: Almost everything that the cookbook contains will be eaten somewhere, and many popular dishes will be missing. But the culinary ‘standard’ is of such little concern to cookbook authors that they sort dishes not by popularity, but by course-type. Or alphabetically—just like a dictionary.”

Given the flaws of these previous approaches, corpus linguistics can serve as an additional method that is more reliable and reproducible as well as linguistically adequate to determine meaning in statutory interpretation. Having been explicitly used by the US federal judiciary for the first time in the case of FCC v. AT&T (2011) following an insightful amicus brief (Goldfarb Reference Goldfarb2011), corpus methods have subsequently been discussed and shown to be an appropriate means of statutory interpretation (Mouritsen Reference Mouritsen2010, Reference Mouritsen2011; A. C. J. Lee in State v. Rasabout 2015, paras. 40–134; Solan and Gales forthcoming).

Recently, corpus analysis was even approved and used by a major US court, as the Michigan Supreme Court's majority held that “[l]inguists call this type of analysis corpus linguistics, but the idea is consistent with how courts have understood statutory interpretation” (People v. Harris 2016). In this case, even the dissenters acknowledged corpora as a “truly remarkable and comprehensive source of ordinary English language usage,” disagreeing merely over the interpretation of the data thus obtained (Justices Markman and Viviano, ibid. n14).

Cases like this show that judges are apt and eager to familiarize themselves with the new technology, being occasionally supported by linguist-trained clerks (e.g., A. C. J. Lee by clerk Mouritsen) and expert amici curiae (e.g., Goldfarb Reference Goldfarb2011 and others at www.lawnlinguistics.com/briefs), as well as a growing body of literature on which to rely. As judges and linguists become aware of and increasingly familiar with the practical overlap in their interpretative methods, as more and larger samples of human language become available in digital formats, as the growing power of computers allows for sophisticated analyses and new digital infrastructures, a large-scale deployment of such technologies to judges and scholars becomes easier and ever more likely.

B. Legal Education

Various studies in all professional fields discuss the use and value of corpora in structured education (see Hafner and Candlin Reference Hafner and Candlin2007, 304–05). In particular, corpora may be useful as part of computer-assisted language learning (CALL) and data-driven learning (DDL) programs (e.g., Sinclair Reference Sinclair2004). For instance, law students in Malaysia were taught to use prepositions correctly using a DDL (corpus-based) approach (Yunus and Awab Reference Yunus and Awab2012). Yet, apart from using law students as subjects, such studies bear little substantive relation to the law. What role can corpora play in legal skill acquisition, such as legal reasoning and argumentation (see Vogel forthcoming a)?

A study by Hafner and Candlin provided students attending a legal writing course with a corpus of 114 legal cases and a concordancer tool “to gain a better understanding of how particular problematic legal constructions are used in their characteristic legal context” (2007, 306). A more recent study using a 400,000-word corpus of business law demonstrated how curriculum materials can be developed for “teaching the vocabulary of legal documents” (Breeze Reference Ruth2015). Such studies use the corpus as an enhanced and strictly usage-based dictionary or encyclopedia. This approach requires students to have previous methodological skills, while the corpus is an additional useful tool (an affordance in the language of Hafner and Candlin Reference Hafner and Candlin2007) for further imitation learning. Thus, corpus tools merely, though usefully, provide secondary support to the primary methodology of acquisition through class instruction. This secondary function could be strengthened by “using existing legal databases as a corpus resource,” especially when enriched with “corpus-based, language related feedback on queries in existing legal databases” (Hafner and Candlin Reference Hafner and Candlin2007, 317).

Corpora could, however, also play a primary role in legal education: they could help students acquire the requisite methodological skills by revealing the structure of legal argumentation. Much like the case method used in common law jurisdictions, corpus-based education would work from the bottom up, learning from prior examples of proper (or improper) usage. Elementary rhetorical skills such as using the canons of legal interpretation, distinguishing from precedents, determining the ratio decidendi, and thinking analogically can be learned directly from considering the commonalities of various cases, and such commonalities are the centerpiece of any corpus analysis. The teaching of law would thus shift from top-down substantive instruction to bottom-up inference extraction from patterns of language usage: “Such a language-based approach could infuse the materials with a framework, a thread of continuity, based more on language (i.e., not exclusively on legal) aspects of legal writing … by grounding them in research and evidence-based linguistic and discursive analysis of legal language” (Candlin, Bhatia, and Jensen Reference Candlin, Bhatia and Jensen2002, 309, 316).

C. Citations Analysis

So far, one of the most prominent applications of legal corpora has been in citations analysis. Although this approach is commonly associated with natural sciences, where Eugene Garfield and his Institute for Scientific Information revolutionized the way science is conducted, analyzed and evaluated (Garfield Reference Garfield1955, Reference Garfield1970, Reference Garfield1979), citations analysis actually originated in jurisprudence: after early endeavors in eighteenth-century Britain, Frank Shepard compiled a citations index as early as in 1873, which later inspired Eugene Garfield's foray into citations analysis for the natural sciences, while simultaneously vanishing into oblivion within the legal academy (Shapiro Reference Shapiro1992, 338).

Having been rediscovered in the 1980s, citations analysis in law has progressed rapidly: notably, Fred R. Shapiro, a librarian and lecturer at Yale Law School, published numerous original studies and developed the field (Shapiro Reference Shapiro1985, Reference Shapiro1996, Reference Shapiro2001b; Shapiro and Pearse Reference Shapiro and Pearse2012), hence being called “the founding father of a new and peculiar discipline: ‘legal citology’” (Balkin and Levinson Reference Balkin and Levinson1996, 843). Meanwhile, citations analysis has gained footholds in legal research overseas, for example, in Austria (Geist Reference Geist2009), Germany (Hamann Reference Hamann2014c), the Netherlands (Winkels et al. Reference Winkels, Boer, Vredebregt and vanSomeren2014), and for European case law at the ECJ (Panagis and Sadl Reference Panagis and Sadl2015).

While the merits of citations analysis in law have always been disputed (Austin Reference Austin1993; Landes and Posner Reference Landes and Posner1996; Ayres and Vars Reference Ayres and Vars2000), at least four major conferences on the subject attest to its impact and perceived importance: “Trends in Legal Citations and Scholarship” (Chicago-Kent Law Review 1996), “Empirical Evaluations of Specialized Law Reviews” (Florida State University Law Review 1999), “Interpreting Legal Citations” (Journal of Legal Studies 2000), and “The Next Generation of Law School Rankings” (Indiana Law Journal 2006). Though no methodological consensus has yet emerged, citations analysis is increasingly used to identify the influence of scholarship, “not because influence necessarily follows quality as its just reward, but because disproportionate influence constructs our very notions of what good quality scholarship is” (Balkin and Levinson Reference Balkin and Levinson1996, 844). In this spirit, legal citations analysis in the United States has resulted in rankings of the most-cited journal articles (Shapiro and Pearse Reference Shapiro and Pearse2012), journals (Shapiro Reference Shapiro2000a), books (Shapiro Reference Shapiro2000b), academic scholars (Shapiro Reference Shapiro2000c), and law faculties (www.leiterrankings.com/faculty).

Aside from descriptive rankings, legal scholars turn to citations analysis to answer both epistemological and purely practical questions, such as:

-

• Are established academics more productive than younger colleagues (Landes and Posner Reference Landes and Posner1996)?

-

• Does the increased availability of full-text databases impact on the perception of printed articles (Lowe and Wallace Reference Lowe and Wallace2011) or help less-reputed journals (Callahan and Devins Reference Callahan and Devins2006)?

-

• Is legal scholarship out of touch with practical jurisprudence, or does it still bear on judicial decision making (Harner and Cantone Reference Harner and Cantone2011)?

-

• How many copies of any journal should libraries purchase (Brown Reference Brown2002)?

Citations analysis can even help to promote understanding of what constitutes discursive authority and to reveal how majority opinions arise from the white noise of arguments pro and con.

However, legal citations analysis suffers from a lack of available resources. In the United States, Fred Shapiro ruefully admitted that for some of the most interesting questions, “compiling … lists would be prohibitively difficult” (Shapiro Reference Shapiro2001a, vi), and a pioneering study in Germany (where the only prior law journal ranking had been based on expert survey: Gröls and Gröls Reference Gröls and Gröls2009) was described as “requiring a three-digit number of working hours and an effort close to what a single individual can handle at all,” owing mostly to the meager availability and quality of usable digital data (Hamann Reference Hamann2014c, 533). Such challenges have fueled work on new comprehensive research corpora, as outlined below in Section VI.

D. Legislation

Norm construction and speech practices of different actors in the court system were extensively researched in the early days of legal linguistics (e.g., Atkinson and Drew Reference Atkinson and Drew1979; Hoffmann Reference Hoffmann1983; Solan Reference Solan1993; Felder Reference Felder2003). However, little was known about the text construction processes in the context of legislation. Legislation is not only “subsumption ex ante” by the government or “the” Parliament. It is a complex process of text creation involving different actors like ministry officials (lawyers or functionaries, most without linguistic education), interest groups, scientists, politicians, and so on (see Vogel Reference Vogel2012b). As has been shown earlier (Section II.B), these different stakeholders interact with the world of things, the world of norms, and the world of texts.

The “world of things” refers to different opinions and assumptions about “the” world—how social and natural environments work, which problems should be resolved, how they should be (“technically”) resolved and why. Similarly, there are almost always different assumptions about the “world of legal norms,” which includes the state of “the” law (on the books or in action) as well as the rules governing the practical workings of law (canons of construction, institutional structures, etc.).

Both conceptual worlds, that of things and that of norms, have to be constituted by or negotiated through the world of texts. Statutes are only the visible tip of the conceptual iceberg. Therefore, drafting a statute means that the actors (legislators) have to observe the current and to anticipate the future (legal) language use: How will future lawyers, courts, administrators, and nonlegal actors contextualize the new texts? When should one create a new word/phrase, when better use an existing and established speech pattern to prevent misunderstandings?

These questions are already very difficult in the context of one nation or legal culture. They become even more difficult in the context of inter- and transnational law with different legal cultures and different traditions of legal language and interpretation methods (e.g., the twenty-four official languages of the European Union). Hence, these questions cannot be answered by lawyers and practitioners of legislation alone, but only with the help of legal linguists.

Against this backdrop, an increasing number of legal linguists have become involved in legislation over the last twenty years. Best practice examples of lawyers and linguists cooperating in legislation are the central language services (Zentrale Sprachdienste) at the Swiss Federal Chancellery (see Nussbaumer Reference Nussbaumer, Eichhoff-Cyrus and Antos2008; Nussbaumer and Bratschi forthcoming) and the editorial office for legal language (Redaktionsstab Rechtssprache) at the German Federal Ministry of Justice and Consumer Protection (see Schade and Thieme Reference Schade, Thieme and Moraldo2012; Thieme and Raff forthcoming). However, there is a lack of freely available large corpora of legal texts as well as of empirical methods to control introspection in legislation. According to Baumann (Reference Baumann and Vogel2015, 268–69; see also Vogel forthcoming a), there are several questions that could best be answered with the help of empirical studies and a free legal reference corpus:

-

• How was language (vocabulary) used in the past and today, in different areas of law?

-

• How often, by who, and where are particular expressions used, and what meaning is attributed to them?

-

• Which speech patterns have special meanings within the legal community?

-

• Which words tend to cluster within a particular expression (co-occurrences)?

-

• Which expressions apply to similar yet different contexts (quasi-synonyms) and must be defined specifically in statutes?

Carefully prepared legal reference corpora with graphical user interfaces (GUIs) would allow legislators to use computer-assisted analysis methods in an interdisciplinary working environment. Such a toolkit (currently being prepared by one of the authors in Germany under the moniker legisstant) will interact with several corpus-generated metrics about pattern frequencies on different expression levels of legal language. It will not only show the relevant texts, connected explicitly by citation references (on legal recommender systems, see Winkels et al. Reference Winkels, Boer, Vredebregt and vanSomeren2014), but also allow the user to explore the draft of a statute online, with meta-information about the currently used phrases and potential alternatives.

V. Existing Specialized Legal Corpora

We now turn to existing corpora of legal texts that document specialized legal vocabularies used in several languages around the world. Good overviews of existing legal corpora can be found in Marín Pérez and Rea Rizzo (Reference Marín, José and Rizzo2012) and Pontrandolfo (Reference Pontrandolfo2012). They listed corpora in several languages and for various purposes: Pontrandolfo (Reference Pontrandolfo2012, 127, 131) focused on English, Spanish, and Italian corpora aimed at translation studies, while Marín Pérez and Rea Rizzo (Reference Marín, José and Rizzo2012, 133–34) reviewed corpora with English sections for research in professional language learning. More recently, Goźdź-Roszkowski and Pontrandolfo (Reference Goźdź-Roszkowski and Pontrandolfo2015) concisely reviewed the state of the art of “corpus-based applications” in legal phraseology as part of a special journal issue collating different original research.

Extending and updating these previous reviews, we describe a number of existing corpora that have been used in earlier research (for a summary, see Table 1). We cannot provide an exhaustive list of all legal text corpora in existence. Instead, we seek to illustrate the variation seen hitherto. Our focus lies on synchronic corpora that have been specially processed for research use, not merely proprietary databases for targeted text retrieval (e.g., Westlaw or Lexis) or even free interface-enhanced legal text collections (e.g., the Free Law Project: www.free.law), even though they can be very useful for linguistic research.

Table 1. Legal Corpora

| Content | Size | Language | Literature | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| American Law Corpus (ALC) | Academic journals, textbooks, briefs, contracts, legislation, and opinions | 5.5 million words | English | Goźdź-Roszkowski (Reference Goźdź-Roszkowski2011) |

| Bononia Legal Corpus (BoLC) | Directives and judgments of the European Community from 1968 until 1995 | 20 million words | Italian, English | Favretti, Tamburini, and Martelli (Reference Favretti, Tamburini, Martelli and Teubert2007) |

| British Law Report Corpus (BLaRC) | Law reports from Northern Ireland, Scotland, England, and Wales from 2008 until 2010 | 1,228 texts | English | Marín Pérez (Reference Marín and José2014) |

| CAL2 Corpus of European Law | Statutes, academic texts, decisions, and opinions, most from ca. 1980 until today | 1 billion words | German, English | See Section VI |

| Corpus of Historical English Law Reports (CHELAR) | English law reports from 1535 until 1999 | Half a million words | English | López-Couso and Méndez-Naya (Reference López-Couso, Méndez-Naya and Vázquez2012); Rodríguez-Puente (Reference Rodríguez-Puente2011) |

| Corpus de Sentencias Penales (COSPE) | Criminal judgments from 2005 to 2012 | 782 texts with 6 million tokens | English, Spanish, Italian | Pontrandolfo (Reference Pontrandolfo, Fantinuoli and Zanettin2014, 142) |

| Corpus of US Supreme Court Opinions | Decisions by the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) from 1790s to present | 32,000 texts, 130 million words | English | corpus.byu.edu/scotus |

| DS21 corpus | Swiss legal texts from the early Middle Ages to 1798 | 4 million words | German, French, Italian, Rhaeto-Romanic, Latin | Höfler and Piotrowski (Reference Höfler and Piotrowski2011) |

| EUCLCORP | Case law of the Court of Justice of the European Union and the constitutional/supreme courts of the member states | In progress | Multilingual | llecj.karenmcauliffe.com |

| House of Lords Judgments Corpus (HOLJ) | Judgments by the House of Lords from 2001–2003 | 188 texts | English | Grover, Hachey, and Hughson (Reference Grover, Hachey and Hughson2004) |

| JRC-Acquis | Texts from EU legislation | 463,792 texts | 22 EU languages | Steinberger et al. (Reference Steinberger, Pouliquen, Widiger, Ignat, Erjavec, Tufi and Varga2006) |

| LEGA | Legal-administrative texts | 1 million words | Galician, Spanish | Gómez Guinovart and Sacau Fontenla (Reference Gómez Guinovart and Sacau Fontenla2004) |

| Lindroos (corpus study) | Criminal judgments from 2010 to 2013 | 120 texts, 1,000+ print pages | German, Finnish | Lindroos (Reference Lindroos2015, 31–36) |

| Old Bailey Corpus | Proceedings of London's Central Criminal Court from 1674–1913 | 197,745 texts | English | Huber (Reference Huber2007) and www.oldbaileyonline.org |

| Swiss Legislation Corpus (SLC) | Legislative writings of the Swiss Confederation | 5,745 texts | German, French, Italian | Höfler and Piotrowski (Reference Höfler and Piotrowski2011) |

Research corpora have several advantages over legal databases or collections: they provide greater flexibility (unrestricted by predesigned user interfaces), allow for precisely balanced sampling of texts by various meta-data, and they make texts accessible for statistical processing (like calculating which words frequently accompany one another, so-called collocations, or presenting frequency distributions over various combinations of meta-data). Also, annotation layers can be added that enable new search capabilities, such as retrieving multiword expressions or syntactic structures.

Legal corpora may incorporate different text types. Court opinions are often preferred over other genres (“partly because of their easy accessibility,” Hafner and Candlin Reference Hafner and Candlin2007, 307), but a number of corpora also include other text types, such as articles from academic journals and textbooks. Most corpora are compiled within the context of a linguistic research project to serve one research question, and are thus rather small and not always publicly available.

The British Law Report Corpus (BLaRC) contains law reports from Northern Ireland, Scotland, England, and Wales (Marín Pérez 2014, 55–56). It includes 1,228 records of juridical decisions from 2008 until 2010 from various legal fields.

Another corpus with texts from the British juridical system is the House of Lords Judgments Corpus (HOLJ), which was developed at the University of Edinburgh (Grover, Hachey, and Hughson Reference Grover, Hachey and Hughson2004). It consists of 188 judgments pronounced by the House of Lords from 2001 until 2003. Several annotation layers were added to support automatic summarization.

The American Law Corpus (ALC) was created by Goźdź-Roszkowski (Reference Goźdź-Roszkowski2011, 27) and its 5.5 million words cover different text types like academic journals, textbooks, briefs, contracts, legislation, and opinions, with the aim of studying linguistic patterns and phraseology. At more than twenty times this size, The Corpus of US Supreme Court Opinions compiled by Mark Davies and unveiled at the 2017 BYU Symposium (see III. above) contains some 32,000 SCOTUS decisions since the 1790s, currently comprising about 130 million words (corpus.byu.edu/scotus).

Most legal corpora containing languages other than English are not monolingual, but comparative or parallelized in multiple languages used for translation studies. For example, the Corpus de Sentencias Penales (COSPE) contains 782 criminal judgments from 2005 to 2012 with some 6 million tokens, split equally between English, Spanish, and Italian (Pontrandolfo Reference Pontrandolfo, Fantinuoli and Zanettin2014, 142). Possibly the biggest multilingual legal corpus, though not just created for research, is JRC-Acquis (http://www.islrn.org/resources/821-325-977-001-1), which includes texts from EU legislation, parallelized in twenty-two languages (see Steinberger et al. Reference Steinberger, Pouliquen, Widiger, Ignat, Erjavec, Tufi and Varga2006). In its current version 3.0 it comprises 463,792 texts, ranging from 20.9 to 62.1 million words per language (48 million on average).

Another corpus of European law, focused on ECJ case law (EUCLCORP), is currently being developed at the University of Birmingham (llecj.karenmcauliffe.com), with proof-of-concept funding by the European Research Council (ERC) having started on July 1, 2016.

LEGA is a subcorpus of the Linguistic Corpus of the University of Vigo (CLUVI) that contains parallelized Galician-Spanish legal texts (see Gómez Guinovart and Sacau Fontenla Reference Gómez Guinovart and Sacau Fontenla2004).

The Bononia Legal Corpus (BoLC) consists of Italian and English texts with 10 million words as the smallest target per language (Favretti, Tamburini, and Martelli Reference Favretti, Tamburini, Martelli and Teubert2007, 14) and it contrasts two different legal systems. It covers the text productions of the European Community from 1968 until 1995, the text types being directives and judgments. It was developed at the University of Bologna to serve as a guide for lexicon builders and translators.

The Swiss Legislation Corpus (SLC) gathers the current Swiss federal law (Höfler and Piotrowski Reference Höfler and Piotrowski2011). This parallel corpus consists of 5,745 texts in German, French, and Italian, the official languages in Switzerland. It is considered domain-complete since it comprises all the legislative texts of the Swiss Confederation (Höfler and Piotrowski Reference Höfler and Piotrowski2011, 83). The texts are annotated and enriched with meta-data.

Most of the legal corpora focus on newer texts, but there are also a few historical collections. For example, the DS21 corpus contains Swiss legal texts from the early Middle Ages until 1798 (Höfler and Piotrowski Reference Höfler and Piotrowski2011), and the Old Bailey Proceedings Online project collected the historical proceedings of London's Central Criminal Court from 1674 to 1913, including almost 200,000 trials (see Huber Reference Huber2007; www.oldbaileyonline.org).

The Corpus of Historical English Law Reports (CHELAR) focuses on the diachronic perspective of legal texts, containing material from 1535 until 1999. It was originally compiled as part of the ARCHER project (A Representative Corpus of Historical English Registers), a historical multigenre corpus of British and US English. According to López-Couso and Méndez-Naya (Reference López-Couso, Méndez-Naya and Vázquez2012, 16), the Corpus of Historical English Law Reports as a subcorpus of ARCHER “is probably too limited for an in-depth analysis of the characteristics of legal language.” Therefore, they planned to expand it in collaboration with Paula Rodríguez-Puente (Reference Rodríguez-Puente2011) to half a million words.

In Germany, various corpora were assembled by the contributors to this article: Hamann (Reference Hamann2014c, 512–16) compiled a corpus of research articles from academic law journals for citations analysis. The corpus included roughly 35,000 texts from legal areas such as criminal law, public law, and business law. Vogel, Christensen, and Pötters (Reference Vogel, Christensen and Pötters2015) collected 9,000 court decisions from 1954 until 2012 to examine the usage of the term “employee” (Arbeitnehmer) in German jurisprudence. For an earlier study, Vogel (Reference Vogel, Felder, Müller and Vogel2012a) gathered 4,200 decisions from the German Federal Constitutional Court to investigate recurrent patterns in juridical discourse about “human dignity” (Menschenwürde).

A more recent corpus study compared German and Finnish criminal judgments at the lowest tier of the respective judicial hierarchies (where formulaicity of legal language was assumed to be greatest), assembling by hand a corpus of 57 German and 63 Finnish judgments from 2010 to 2013, with a reported size of over one thousand print pages (Lindroos Reference Lindroos2015, 31–36).

VI. The Cal2 Corpus of German Law (JUREKO): Toward New Resources for Legal Linguistics

As a recent addition to the infrastructure of legal linguistics, our international research group CAL2 (www.cal2.eu) has systematically developed corpora since 2013. Funded by the Academy of Sciences in Heidelberg (Germany), we have created a large corpus of relevant text types of German law from three main domains:

-

• Federal statutes (legislation, 2015);

-

• Decisions by federal courts and select lower courts (case law, 1951–2015);

-

• Articles published in major law journals (academic texts, 1980–2015).

We collected texts from all legal areas—finance law as well as labor law and constitutional law—to establish a representative reference corpus (CAL2 Corpus of German Law, abbreviated in German as JuReko). This corpus follows a different approach from most of the ones presented above: instead of tailoring the corpus to fit one particular research question, JuReko gathers materials to serve as a reference for the legal genre and to allow multiple types of analysis, which makes it a versatile infrastructure for legal linguistic research.

Using XSL transformations, all texts were converted to TEI P5 conformant XML—a de facto standard with “comprehensive guidelines … and a large helpful community” (Stührenberg Reference Stührenberg2012, 10). We extracted meta-data (like title, date, court instance, etc.) and stored them in a relational MySQL database. Citation information in footnotes and references (especially of academic texts) were marked in our source files with the help of TEI tags. Besides footnotes and meta-data, we dealt with text sections that are peculiar to the legal genre: for instance, in court decisions, we annotated the statement of factual findings (Tatbestand) and the reasons—or grounds—for the decision (Urteilsgründe), using hypertext tags in our source material and recurring formulae in the template of German judgments. We also added part-of-speech (POS) information to the main texts, that is, a text layer where words are reduced to their basic forms, as a means of linguistic normalization to cancel the noise caused by grammatical inflection.

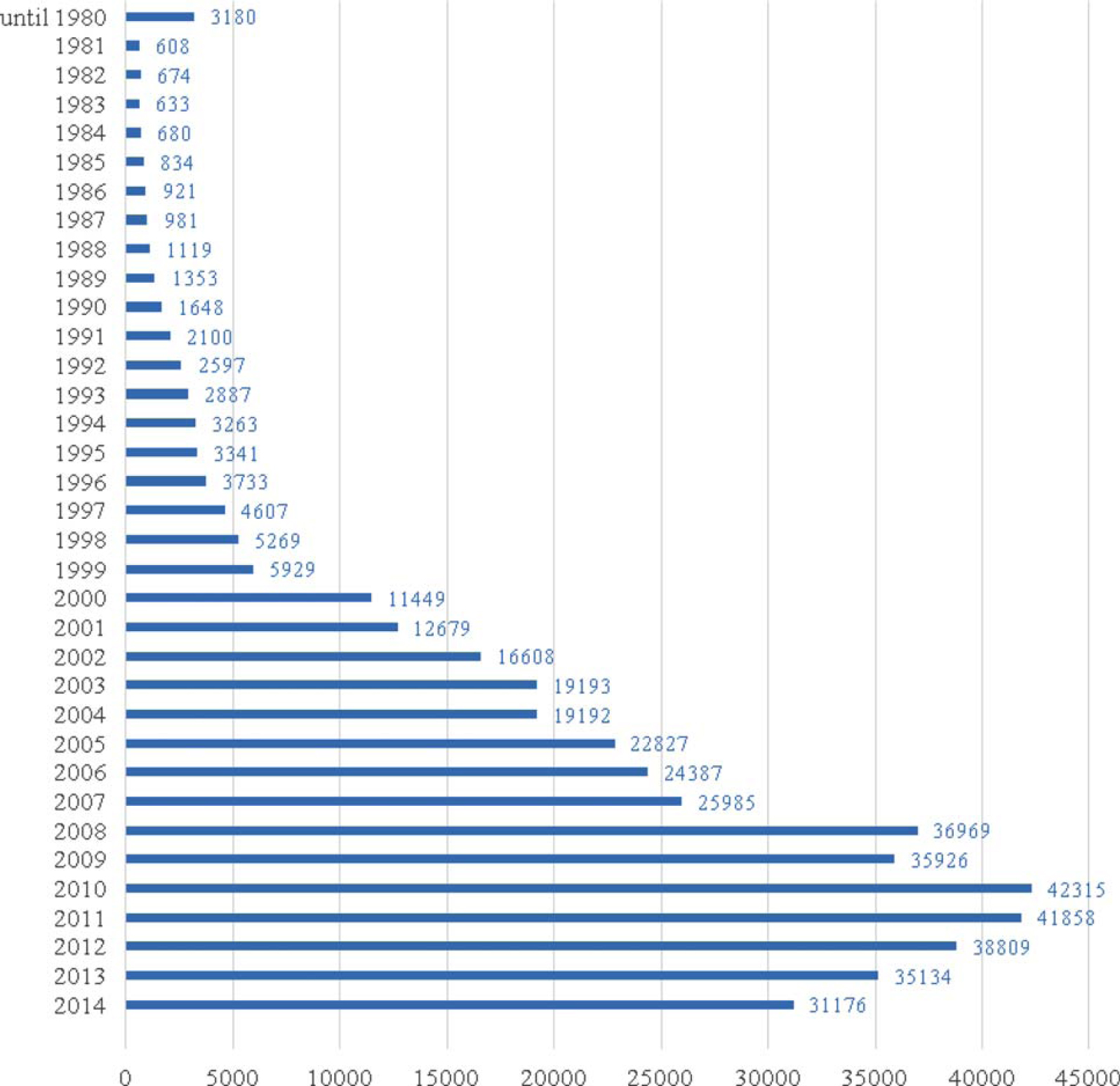

Currently, the CAL2 Corpus of German Law includes more than 43,000 academic papers (approximately 150 million words), about 370,000 case law texts (approximately 800 million words), and about 6,300 statutes (approximately 2.3 million words). The target size is about 1 billion words as a static corpus, which will be updated in the future. For more information, see Figure 2.

Figure 2. Number of Texts per Year Currently Contained in the CAL2 Corpus of German Law [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

The CAL2 Corpus of German Law is the first large-scale representative corpus for computer-assisted analyses of German legal language. In September 2015, we started to build a similar corpus of British case law to compare speech patterns of German and British labor law and to explore commonalities and differences in the European legal languages. Both corpora are currently merged into a unified CAL2 Corpus of European Law for comparative studies in legal linguistics.

To accompany this development, the first international conference was held in March 2016 at the Heidelberg Academy of Sciences: The two-day event, titled “The Fabric of Law and Language: Discovering Patterns Through Legal Corpus Linguistics,” brought together preeminent scholars of law and corpus analysis, whose discussion “touched on some of the essential epistemological issues of interdisciplinary research and evidence-based policy, and marks the way forward for legal corpus linguistics” (Vogel et al. Reference Vogel, Hamann, Stein, Abegg, Biel and Solan2016).

Select papers presented at the conference will be published in the International Journal of Language and Law (JLL) in 2017, and the CAL2 group will host another session on “Corpus Linguistics and Hermeneutics in Legal Linguistics” at the ILLA Relaunch Conference, to be held September 7–9, 2017 in Freiburg, Germany (see www.illa.online).

VII. Conclusions

In this article, we introduced CAL2 as an approach to analyze, describe, and improve legal practice. We see potential applications in various fields, such as analyzing legal semantics, improving legal interpretation in the courtroom, as well as in legislation, and expanding education for new lawyers, as well as citations and network analysis. Such applications need new corpora of structured data, especially of digitized legal texts. To move beyond specialized corpora that are only generated for single project studies, the CAL2 research group develops legal reference corpora for all relevant domains.

A limitation of this approach should be noted: even corpus research cannot automate adjudication or provide an ontology of transcendental rules for producing “objective” decisions (by some truth standard). Since the 1970s, with the rise of computer engineering, various research groups (from Rave, Brinkmann, and Grimmer Reference Rave, Brinkmann and Grimmer1971 to Raabe et al. Reference Raabe, Wacker, Oberle, Baumann and Funk2012) have attempted to develop “subsumption automata.” These attempts failed because machines only work with predefined information structures, and cannot review information in a context of discordant views, semantic struggles, and the general relativity of ways to describe the world. Computers may be able to determine the occurrence of, but they cannot decide, social conflicts (see Kotsoglou Reference Kotsoglou2014). Hence, CAL2 relies on computers expressly for assistance, not automation. Even where we criticize introspection as the sole source to discover linguistic meaning, we do not seek to replace it with algorithms. Interpretation and “application” of legal texts will always be cognitive processes of contextualization using sensory input and background knowledge. Therefore, empirical data and computer algorithms can only support legal decision making and provide a new instrument for the legal “toolbox,” which still needs wielding by a competent hand.

The quality of CAL2 depends on the quality of successful interdisciplinary research by linguists, lawyers, and computational scholars both in theory and practice. This requires a common (meta) language as well as an intercultural understanding of the interests, basic theoretical backgrounds, methods, and limitations of each of these disciplines. Besides technical issues, this will be the biggest challenge in years to come.