Introduction

For over two decades, the neurodevelopmental hypothesis for schizophrenia (SZ) etiology is the most prominent conceptualization for SZ pathogenesis, supporting the occurrence of early life brain-related developmental abnormalities which might be caused by both genetic and environmental determinants [Reference Weinberger1–3]. Premorbid adjustment (PA) difficulties likely represent an index of neurodevelopmental compromise and have been recognized as a significant risk factor for the development of SZ later in life [Reference Malmberg, Lewis, David and Allebeck4–6]. Longitudinal studies in clinical high-risk populations have provided evidence for increased conversion rates to psychosis among individuals with PA deficits [Reference Nieman, Ruhrmann, Dragt, Soen, van Tricht and Koelman7–9], while poor social PA has been associated with prodromal signs of psychosis [Reference Tarbox-Berry, Perkins, Woods and Addington10]. Impairments in both social and academic PA have been extensively documented in adult patients with SZ [Reference Shapiro, Marenco, Spoor, Egan, Weinberger and Gold6, Reference Cannon, Jones, Gilvarry, Rifkin, McKenzie and Foerster11–17], bipolar disorder [Reference Cannon, Jones, Gilvarry, Rifkin, McKenzie and Foerster11,Reference Bucci, Galderisi, Mucci, Rossi, Rocca and Bertolino18], and patients with first-episode psychosis (FEP) [Reference Payá, Rodríguez-Sánchez, Otero, Muñoz, Castro-Fornieles and Parellada19,Reference Haas and Sweeney20]. Importantly, PA abnormalities among patients with psychotic disorders, particularly social maladjustment, may represent a reliable predictor of unfavorable long-term clinical outcomes and enduring negative symptoms [Reference Monte, Goulding and Compton21–27], cognitive dysfunction [Reference Stefanatou, Karatosidi, Tsompanaki, Kattoulas, Stefanis and Smyrnis28], and inadequate treatment response [Reference Rabinowitz, Harvey, Eerdekens and Davidson29–31].

Previous research has shown that individuals with early-onset SZ are characterized by more pronounced PA deficits than adult-onset cases [Reference Vourdas, Pipe, Corrigall and Frangou32], implying that neurodevelopmental disruptions are responsible for the earlier expression of psychotic symptoms, possibly attributed to genetic risk factors [Reference Owen and O'Donovan33]. A suspected genetic component may be at least in part responsible for the PA deficits observed in patients diagnosed with SZ [Reference Shapiro, Marenco, Spoor, Egan, Weinberger and Gold6,Reference Walshe, Taylor, Schulze, Bramon, Frangou and Stahl34]. Few studies have demonstrated an association between poor PA and the existence of positive family history for psychiatric illness among individuals with SZ [Reference Foerster, Lewis, Owen and Murray35,Reference St-Hilaire, Holowka, Cunningham, Champagne, Pukall and King36], yet opposing findings have also been reported [Reference Goldberg, Fatjó-Vilas, Penadés, Miret, Muñoz and Vossen37]. In addition, a number of family studies have documented PA weaknesses in relatives or unaffected siblings of individuals with SZ [Reference Shapiro, Marenco, Spoor, Egan, Weinberger and Gold6,Reference Bucci, Galderisi, Mucci, Rossi, Rocca and Bertolino18,Reference Vassos, Sham, Cai, Deng, Liu and Sun38,Reference Quee, Meijer, Islam, Aleman, Alizadeh and Meijer39], indicating that genetic risk for SZ may be a contributing factor to premorbid dysfunction. Prior evidence indicate that poor PA could be related with an earlier age at onset (AAO) in individuals experiencing psychosis [Reference Haas and Sweeney20,Reference Monte, Goulding and Compton21,Reference Vourdas, Pipe, Corrigall and Frangou32,Reference Goldberg, Fatjó-Vilas, Penadés, Miret, Muñoz and Vossen37], suggesting that early life neurodevelopmental aberrations might worsen the progression of the clinical syndrome and accelerate the onset of psychotic symptoms. In support of the above view, observations in patients with early-onset SZ and bipolar disorder suggest the involvement of neurodevelopmental pathways in the development of psychosis [Reference Arango, Fraguas and Parellada40,Reference Bombin, Mayoral, Castro-Fornieles, Gonzalez-Pinto, de la Serna and Rapado-Castro41]. Familial effects have been demonstrated for AAO in psychotic disorders [Reference Goldberg, Fatjó-Vilas, Penadés, Miret, Muñoz and Vossen37, Reference Suvisaari, Haukka, Tanskanen and Lönnqvist42,Reference Esterberg and Compton43]; however, negative findings also exist [Reference Kendler, Karkowski-Shuman and Walsh44,Reference Bergen, O'Dushlaine, Lee, Fanous, Ruderfer and Ripke45].

Premorbid maladjustment is postulated to reflect disrupted neurodevelopmental trajectories [Reference Haas and Sweeney20], likely predisposing a subgroup of vulnerable individuals to develop psychotic symptoms lying in the SZ-spectrum or affective psychoses diagnostic entities [Reference Cannon, Jones, Gilvarry, Rifkin, McKenzie and Foerster11,Reference Parellada, Gomez-Vallejo, Burdeus and Arango12] and is often documented among first-episode psychotic patients [Reference Monte, Goulding and Compton21–23]. Herein, we aimed to amalgamate and analyze demographic and clinical data collected from well-characterized unrelated cases diagnosed with FEP and SZ in an attempt to investigate the potential moderating role of familial liability to psychosis and parental socioeconomic status (SES) on aspects of PA and AAO. Family history of psychosis (FHP) is considered a proxy phenotype of genetic risk [Reference van Os, Pedersen and Mortensen46,Reference Binbay, Drukker, Alptekin, Elbi, Aksu Tanık and Özkınay47], while parental SES denotes an index of socioeconomic position associated with PA [Reference Tarbox, Brown and Haas48] and represents an environmental risk factor for psychosis-spectrum disorders [Reference Wicks, Hjern, Gunnell, Lewis and Dalman49–51] that might interact with genetic liability to further increase the likelihood of developing SZ [Reference Binbay, Drukker, Alptekin, Elbi, Aksu Tanık and Özkınay47,Reference Wicks, Hjern and Dalman52]. Prompted by recent evidence implicating deviant PA and early AAO in treatment resistance in SZ [Reference Legge, Dennison, Pardiñas, Rees, Lynham and Hopkins31], early response to antipsychotic medication in FEP cases and treatment resistance in SZ cases were also evaluated.

Methods

Participants

First-episode psychosis patients

A total of 130 FEP cases (mean age: 25.5 ± 7.3 years; age range: 16–45 years) were assessed in five mental health services throughout the metropolitan area of Athens, as part of an ongoing longitudinal research project aiming to investigate the involvement of genetic and environmental determinants on psychosis risk. National legislation dictates that adult mental health care and hospitalization is provided to all patients above the age of 16 years. Sample eligibility criteria and detailed clinical information are reported elsewhere [Reference Xenaki, Kollias, Stefanatou, Ralli, Soldatos and Dimitrakopoulos53]. Exclusion criteria included: (a) age at psychosis onset <16 years, (b) the presence of psychotic symptoms due to an organic cause or acute intoxication, (c) history of serious neurological disorder, (d) intelligence quotient <70, and (e) belonging to the ultra-high-risk phenotype [Reference van Os and Linscott54]. At admission, 75% of cases were either drug-naïve or had received medication for a single day (Table S1). All cases were screened using the Diagnostic Interview for Psychoses (DIP) [Reference Castle, Jablensky, McGrath, Carr, Morgan and Waterreus55], a standardized semi-structured interview which generates diagnoses according to different diagnostic algorithms, on the basis of the Operational Criteria Checklist for Psychotic Illness (OPCRIT) [Reference McGuffin, Farmer and Harvey56]. According to the International Classification of Diseases 10th Revision (ICD-10), 83.2% of cases were diagnosed with nonaffective psychotic disorder (ICD-10 codes: F20-29). Written informed consent was obtained after a detailed description of the research objectives and the study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Eginition University Hospital.

Schizophrenia patients

We recruited 115 male inpatients (mean age: 33.2 ± 8.6 years; age range: 19–50 years) who met the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV) diagnostic criteria for SZ (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). SZ cases were examined by trained psychiatrists (E.K., N.S.) and a clinical psychologist (P.S.) during their hospitalization at the secured psychiatric ward for adult male individuals in Eginition University Hospital (Athens, Greece). All patients were clinically evaluated using the DIP diagnostic interview [Reference van Os and Linscott54] and at the time of assessment were receiving drug treatment with either conventional or atypical antipsychotics (Table S1). Among cases, the mean years of illness were 11.2 ± 8.5. Exclusion criteria included (a) the presence of mental retardation, (b) history of serious neurological disorder, (c) illness onset preceding completion of the 16th year of age, and (d) unavailability of close relatives to provide valid information related to premorbid functioning. All patients provided signed informed consent before entering the study.

Assessments

Premorbid adjustment

The Cannon-Spoor Premorbid Adjustment Scale (PAS) [Reference Cannon-Spoor, Potkin and Wyatt57] was administered to assess PA in both SZ and FEP cases. The PAS retrospectively examines aspects of premorbid functioning across four developmental stages: childhood (up to 11 years), early adolescence (12–15 years), late adolescence (16–18 years), and adulthood (19 years and beyond); and across two domains: academic (scholastic performance, adaptation to school) and social (sociability/withdrawal, peer relationships, and socio-sexual functioning). Detailed information with regard to early life functioning was obtained by trained psychiatrists via semi-structured interviews with both patients and their family members (i.e., parents or siblings). Social PA was estimated through the items of peer relationships and sociability/withdrawal at each age period. Academic PA was estimated through the items of scholastic performance and school adaptation at each developmental stage. All cases included in this study had an illness onset >16 years and completed only childhood and early adolescence PAS subscales to minimize the possibility that behavioral aspects related to the prodromal phase of the illness are captured [Reference Strauss, Allen, Miski, Buchanan, Kirkpatrick and Carpenter15]. In accordance with previous studies, premorbid period was defined as ending 1 year before the emergence of positive psychotic symptoms [Reference Barajas, Usall, Baños, Dolz, Villalta-Gil and Vilaplana58,Reference van Mastrigt and Addington59]. For each developmental stage, academic and social domain PAS scores were estimated, with higher score denoting poorer PA.

Socioeconomic status

Parental SES classification was based on available information related to parental academic achievement and occupational status, as well as total household income per year. Both cases and their accompanying relatives (mainly parents) were interviewed in order to obtain reliable information. Three SES groups (i.e., high, middle, and low) were generated as follows: High SES group included cases with high parental educational level (university or college degree) and occupational activity (i.e., professionals, senior officials, high grade employees, managers), while the annual family gross income exceeded the average family gross income reported for the years 2011–2017 by the Hellenic Statistical Authority (ELSTAT); middle SES group included cases with intermediate level of parental education (high-school terminated, technical school diploma) and occupation status (i.e., low-level employee, technician), while the annual family gross income was similar or slightly lower from the country’s average (up to 20% below national average) reported by ELSTAT; low SES group included the remaining cases and those cases that reported family gross income equal or below the country’s poverty threshold, irrespective of the parental educational/occupational level. Valid SES data were obtained from 202 cases (100 FEP; 102 SZ), as a small number of cases or family members denied to provide relevant information or their responses deemed untrustworthy.

Family history

The occurrence of psychotic illness among biological relatives was determined using the Family Interview for Genetic Studies [Reference Maxwell60]. Cases reporting that a first or second degree relative was diagnosed with affective or nonaffective psychotic disorder were marked as having positive FHP (details in supplementary text). Positive FHP has been considered a proxy phenotype for increased genetic risk of psychosis [Reference van Os, Pedersen and Mortensen46,Reference Binbay, Drukker, Alptekin, Elbi, Aksu Tanık and Özkınay47], supported by molecular genetic evidence demonstrating that individuals with positive FHP are characterized by higher polygenic loading for SZ [Reference Bigdeli, Ripke, Bacanu, Lee, Wray and Gejman61,Reference Taylor, Asabere, Calkins, Moore, Tang and Xavier62].

Age at onset

In both patient groups, we recorded the age at which psychotic symptoms (principally positive symptoms) appeared for the first time (OPCRIT item 4), as part of the DIP diagnostic interview [Reference Castle, Jablensky, McGrath, Carr, Morgan and Waterreus55] on the basis of information gathered from both the patient and his/her family members. Cases with an AAO greater than 16 years were considered for further analysis.

Response to treatment

Administration of clozapine (34 SZ cases) was used as a proxy measure of treatment resistance in SZ cases [Reference Legge, Dennison, Pardiñas, Rees, Lynham and Hopkins31]. Treatment response assessment in FEP cases was based on Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) scores obtained at admission (baseline assessment) and 4 weeks later (follow-up assessment). Symptomatic remission was determined according to the Andreasen’s consensus remission criteria [Reference Andreasen, Carpenter, Kane, Lasser, Marder and Weinberger63]. Cases not fulfilling the above criterion for clinical remission were defined as nonresponders to antipsychotic medication (36 FEP cases). Prior evidence suggests that greater than 80% of FEP cases who do not initially respond to first-line antipsychotic treatment will develop treatment resistance [Reference Demjaha, Lappin, Stahl, Patel, MacCabe and Howes64].

Statistical analyses

Socio-demographic and clinical characteristics were compared between FEP and SZ patient groups using χ 2-tests for dichotomous variables and analyses of variance for continuous variables. Linear regression analyses were performed to assess the impact of FHP status (negative FHP set as reference) and parental SES (high parental SES set as reference) on PA domain scores and AAO, adjusting for gender, age, and psychiatric site at admission. Further, as the analyses were conducted in a mixed sample of FEP and SZ cases, we adjusted all models for diagnostic status, while separate analyses were performed in each patient group. PA domain scores were standardized before analysis and a log-transformation was applied to AAO to account for positive skewness. The association between PA domain scores and AAO was examined using linear regressions and logistic regressions were performed to test associations with treatment resistance, adjusting for the same covariates as above. Sensitivity analyses were also performed to account for possible confounding effect related to medication exposure at baseline. Multiple regression models were fitted to investigate interaction effects between FHP and parental SES status on PA domains, AAO and treatment resistance, including both the main effects of each individual predictor (FHP, parental SES) and their interaction term. An interaction on the additive scale was declared if the estimated effect size of the interaction term was greater than the sum of individual effect sizes of each predictor. It has been suggested that the presence of additive statistical interaction most likely designates a factual biological mechanism [Reference Rothman65]. Adjusted R-squared (R 2) estimates were calculated to assess the proportion of the explained phenotypic variance. As in principle, this study aimed to provide external validity to previously reported findings and the analysis of joint effects between predictors (interaction models) was deemed exploratory, the level of statistical significance was set at p < 0.05 (two-tailed). All statistical analyses were conducted using R v3.5.0 (http://www.r-project.org).

Results

Comparisons between socio-demographic characteristics

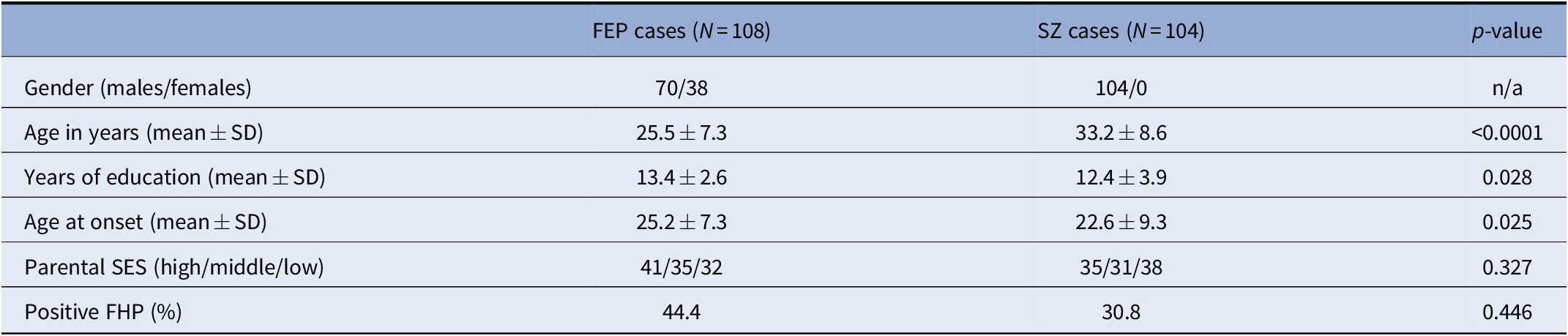

In total, 212 cases were included in our analyses (108 FEP, 104 SZ; 174 males, 38 females). Valid information on parental SES was acquired from 202 cases (100 FEP, 102 SZ; 166 males, 36 females). Compared to SZ cases, FEP cases had lower mean age (F = 52.5; p < 0.0001), more years of education (F = 4.92; p = 0.028) and a later AAO (F = 5.07; p = 0.025), while they did not differ in terms of family history for psychosis (FHP) (χ 2 = 0.582; p = 0.446) and parental SES (F = 0.965; p = 0.327). Our analyses did not provide evidence that cases with positive FHP were characterized by lower parental SES (χ 2 = 2.24; p = 0.135) or an earlier AAO (F = 0.00; p = 0.985), yet we confirmed an earlier AAO among males (F = 14.0; p = 0.0002) and a higher prevalence of positive FHP among females (χ 2 = 6.41; p = 0.011). Moreover, the presence of lower parental SES did not significantly correlate with AAO (F = 1.20; p = 0.275). Females were more likely to exert social PA difficulties in childhood compared to males (F = 4.41; p = 0.037), whereas no differences were observed in early adolescence (F = 1.01; p = 0.316). Similarly, FEP and SZ cases did not differ in terms of academic or social PA in both developmental periods (Table S2). Associations between socio-demographic variables in SZ and FEP cases are depicted in Table 1.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of the examined clinical samples.

Abbreviations: FEP, first-episode psychosis; FHP, family history of psychosis; SES, socioeconomic status; SZ, schizophrenia.

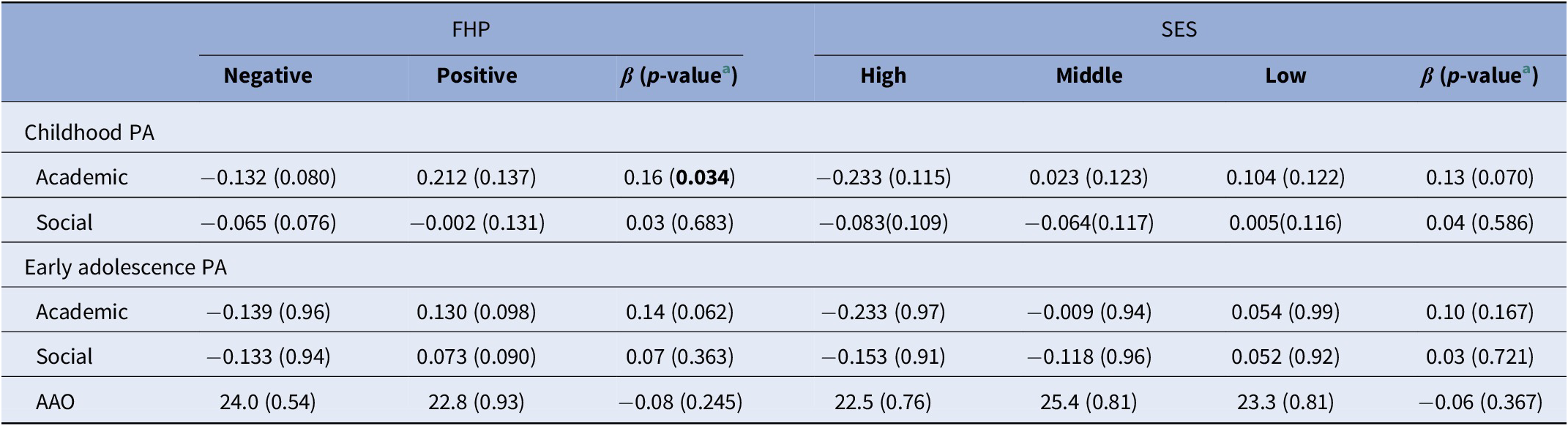

Effects of FHP and parental SES on PA domains and treatment response

In all, 57 cases reported positive FHP and showed worse academic PA during childhood (β = 0.16; p = 0.034) compared to negative FHP cases (n = 155), whereas no noticeable differences in childhood social PA (β = 0.03; p = 0.683) or early adolescence PA domains were observed, even though a trend was found for academic PA (β = 0.14; p = 0.062) (Table 2). With regard to parental SES, we classified cases in three separate groups, namely high SES (n = 74), middle SES (n = 63), and low SES (n = 65). There was no evidence for association between parental SES and academic or social PA in childhood and early adolescence. Likewise, neither FHP (OR = 1.15; 95% CI = 0.57–2.31; p = 0.706) nor parental SES (OR = 0.86; 95% CI = 0.60–1.24; p = 0.424) was associated with response to antipsychotic treatment.

Table 2. Mean (±SEM) values for PA domain scores and AAO for all cases after stratification for FHP and parental SES status.

Abbreviations: AAO, age at onset; FHP, family history of psychosis; PA, premorbid adjustment; SES, socioeconomic status.

a Results from linear regression analyses, adjusted for sex, age, psychiatric site, and diagnosis status. p-value <0.05 is indicated in bold.

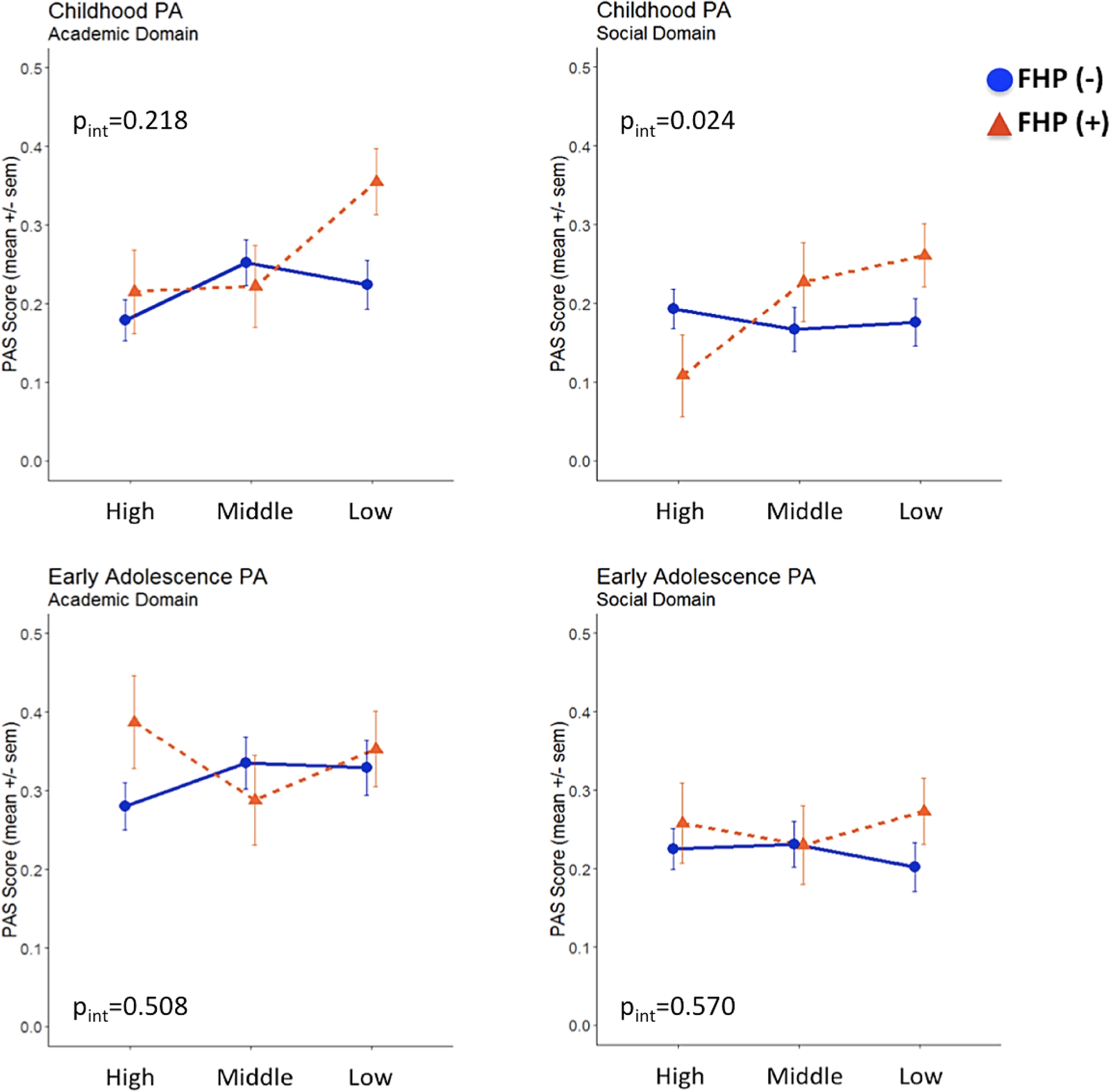

Interplay between FHP and parental SES influences social PA in childhood

We further fitted multiple linear regression models to test departure from additivity, which would be an indication that FHP and parental SES could jointly impact on PA domains and AAO. A statistically significant additive interaction between FHP and parental SES status on childhood social PA was detected (β interaction = 0.194; p = 0.024; adjusted R 2 = 0.021) (Figure 1), as the effect size of the interaction (FHP × SES) term was greater than the sum of the individual effect sizes of FHP and parental SES (Table S1). We observed that cases with both positive FHP and low parental SES reported more pronounced social PA impairments during childhood compared to the remaining cases. Additionally, since a “cross-over” interaction was revealed, cases with positive FHP belonging to the high parental SES subgroup had better social PA within the entire sample, indicating that parental socioeconomic position may moderate early social PA among cases with increased familial loading for psychosis. The interaction effect for academic PA did not reach statistical significance (β interaction = 0.106; p = 0.218; adjusted R 2 = 0.003). No evidence for significant FHP × parental SES interactions was detected for early adolescence PA and AAO.

Figure 1. Academic and social premorbid adjustment domain scores in childhood and early adolescence following stratification for family history of psychosis and parental socioeconomic status.

Deviant social PA predicts an earlier onset of psychosis

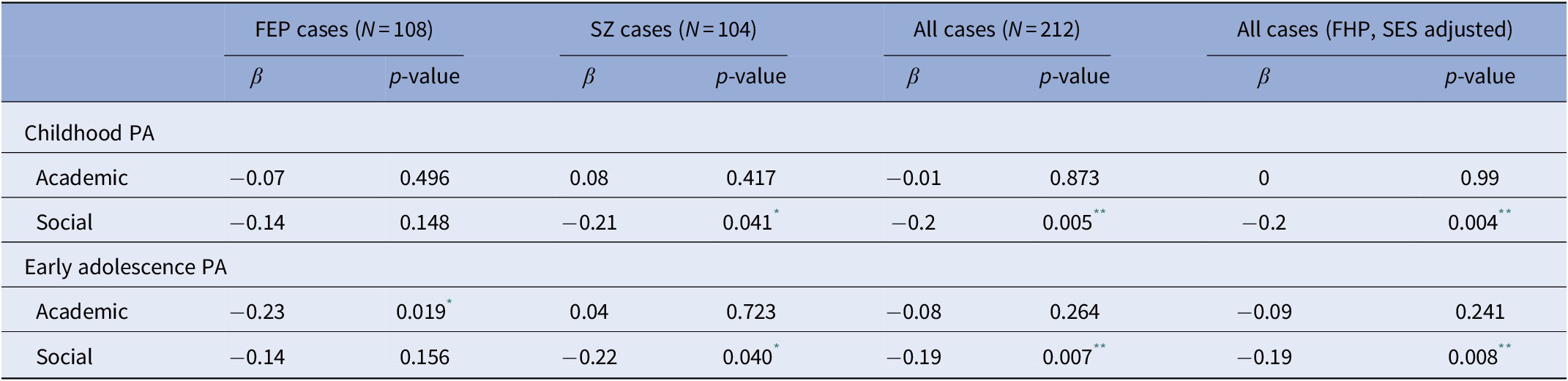

We next sought to confirm previous findings indicating that PA abnormalities predispose to an earlier onset of psychotic symptoms [Reference Payá, Rodríguez-Sánchez, Otero, Muñoz, Castro-Fornieles and Parellada19, Reference Walshe, Taylor, Schulze, Bramon, Frangou and Stahl34–36] and further explore the potential moderation by FHP status and parental SES. An inverse correlation was observed between AAO and poor social PA during childhood (β = −0.20; p = 0.0047) and early adolescence (β = −0.19; p = 0.0073), whereas academic PA did not significantly impact AAO (Table 3). In subsequent analyses, FHP status and parental SES were added as additional plausible confounders in multiple linear regression models and the association effect sizes were compared with those of the primary unadjusted models. As shown in Table 3, no major differences were detected in the association between AAO and social PA.

Table 3. Results of the association between PA domain scores and AAO in FEP and SZ cases.

Abbreviations: AAO, age at onset; FEP, first-episode psychosis; FHP, family history of psychotic disorder; PA, premorbid adjustment; SES, socioeconomic status; SZ, schizophrenia.

* p value <0.05.

** p value <0.01.

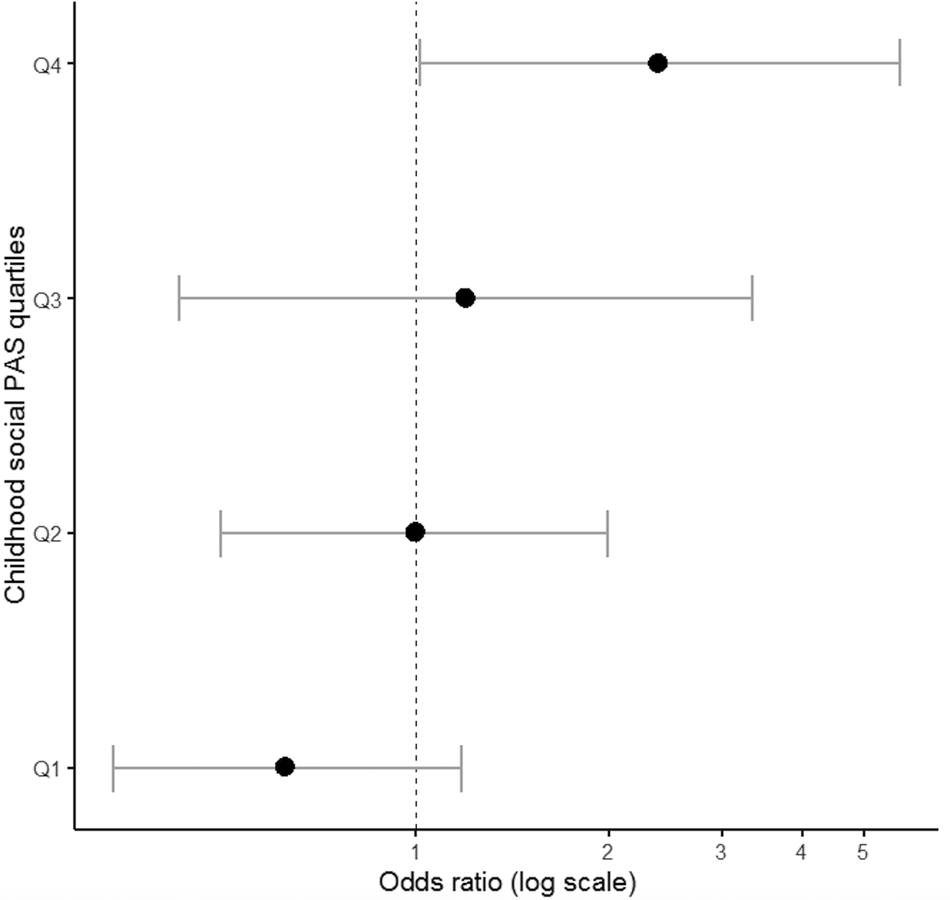

Evidence implicating poor social PA to treatment resistance

To explore the contribution of PA and AAO to antipsychotic treatment response, SZ cases receiving clozapine (treatment resistant cases) and FEP cases not responding to short-term antipsychotic treatment [Reference Andreasen, Carpenter, Kane, Lasser, Marder and Weinberger63] were grouped together (total n = 70) forming a nonresponders group of cases and compared with the remaining cases (treatment responders, n = 142). It is outlined that treatment response was independent of minimal exposure to medication at baseline (Table S1) in a subset of FEP cases (OR = 1.05; 95% CI: 0.63–1.77; p = 0.845). Nonresponders to treatment were characterized by poorer social PA during childhood (OR = 1.37; 95% CI: 0.99–1.89; p = 0.059) and an earlier AAO (OR = 0.47; 95% CI: 0.21–1.08; p = 0.075), which approached statistical significance. Exploratory analyses showed that cases with the highest (i.e., worse) social PA scores in childhood (upper quartile of the distribution) were more likely to be classified as nonresponders (OR = 2.46; 95% CI: 1.04–5.80; p = 0.04) (Figure 2). The above associations remained unchanged following adjustment for FHP, parental SES, and medication exposure at baseline (Table S3). Academic PA in childhood as well as early adolescence PA had no impact on treatment response (all p > 0.2).

Figure 2. Association between social premorbid adjustment domain score in childhood and treatment response to antipsychotic medication.

Discussion

Our findings provide evidence that familial loading for psychosis, most likely reflecting an increased genetic predisposition [Reference Bigdeli, Ripke, Bacanu, Lee, Wray and Gejman61,Reference Taylor, Asabere, Calkins, Moore, Tang and Xavier62], individually or jointly with an environmental component such as parental socioeconomic background may moderate premorbid functioning among individuals who will later develop a psychotic disorder. Family-based studies have previously reported adjustment difficulties in relatives of psychotic patients, suggesting the involvement of presumed genetic influences [Reference Shapiro, Marenco, Spoor, Egan, Weinberger and Gold6,Reference Bucci, Galderisi, Mucci, Rossi, Rocca and Bertolino18,Reference Walshe, Taylor, Schulze, Bramon, Frangou and Stahl34,Reference St-Hilaire, Holowka, Cunningham, Champagne, Pukall and King36]. However, no evidence has emerged for synergism between genetic risk and environmental exposures on PA in psychotic disorders, which has been recently implicated in SZ [Reference Guloksuz, Pries, Delespaul, Kenis, Luykx and Lin66]. The present study corroborates the influence of FHP on premorbid academic adjustment [Reference Walshe, Taylor, Schulze, Bramon, Frangou and Stahl34] and further revealed that parental socioeconomic profile moderates the impact of familial risk for psychosis on early social adjustment. This observation is in agreement with previous studies indicating that familial loading for mental illness and environmental risk factors for psychosis (i.e., urbanicity, social disadvantage, childhood adversity, cannabis use) may act in synergy to increase disease liability [Reference van Os, Pedersen and Mortensen46,Reference Agerbo, Sullivan, Vilhjálmsson, Pedersen, Mors and Børglum51,Reference van Os, Hanssen, Bak, Bijl and Vollebergh67–70]. Moreover, population-wide analyses underscore the contribution of upbringing locale, likely related with socioeconomic profile, to psychosis manifestation and the modifiable role of genetic liability in the incidence of psychotic disorders [Reference Fan, McGrath, Appadurai, Buil, Gandal and Schork71].

We observed that individuals with presumably higher genetic risk for psychosis and growing up in families of lower SES could be more vulnerable to social maladjustment in childhood. Epidemiological evidence from Swedish national registers suggests that positive FHP in adopted children may act in synergy with social disadvantage to increase risk for psychotic disorders [Reference Wicks, Hjern and Dalman52]. Consistent with the above findings, our results imply that genetically predisposed children from families of lower socioeconomic background might exhibit social PA deficits in childhood, which precede the onset of psychotic illness typically in young adulthood. Nevertheless, it is acknowledged that our results do not reveal a causative relationship between poor social PA and the presentation of psychosis, therefore additional validation in independent clinical samples is required to delineate the contribution of G × E on premorbid social functioning. We also note that as a “cross-over” interaction effect was evident, higher parental SES appeared to exert a protective role on social adjustment among cases with positive FHP, indicating that socioeconomic advantage likely increases resilience and eventually prevents the development of PA deviations linked to psychosis expression [Reference Elbau, Cruceanu and Binder72]. It is of interest that recent observations point toward a positive association between downward parental income and greater risk for SZ [Reference Hakulinen, Webb, Pedersen, Agerbo and Mok73], highlighting parental socioeconomic profile as a key environmental determinant involved in SZ etiology.

Additionally, this study validates a significant correlation between poor social PA and an earlier onset of psychotic symptoms, which has been previously reported in patients diagnosed with FEP or SZ [Reference Haas and Sweeney20,Reference Legge, Dennison, Pardiñas, Rees, Lynham and Hopkins31] and underscores the clinical value of assessing premorbid functioning—particularly social behavior—in the context of early intervention strategies for psychotic disorders in high-risk populations. However, it remains to be determined whether the observed correlation could be attributed to genetic or environmental risk factors. In our cohort, the relationship between social PA and AAO was independent of familial risk, suggesting that genetic liability may not be a determinant of AAO. Previous studies have shown that precipitation of psychosis onset is highly probable due to the involvement of environmental risk factors, such as cannabis use and birth complications [Reference Dekker, Meijer, Koeter, van den Brink, van Beveren and Kahn74,Reference Scherr, Hamann, Schwerthöffer, Froböse, Vukovich and Pitschel-Walz75]. We found that positive FHP could not predict an earlier AAO, consistent with previous observations from family-based studies indicating that an earlier AAO in SZ cases may not be the result of an increased genetic liability within relatives, instead it may be determined by unique familial environmental influences for each individual and/or random developmental defects [Reference Esterberg and Compton43,Reference Bergen, O'Dushlaine, Lee, Fanous, Ruderfer and Ripke45]. Other groups have reported an association between familial liability and an earlier AAO in FEP and SZ cases [Reference St-Hilaire, Holowka, Cunningham, Champagne, Pukall and King36, Reference Bombin, Mayoral, Castro-Fornieles, Gonzalez-Pinto, de la Serna and Rapado-Castro41,Reference Suvisaari, Haukka, Tanskanen and Lönnqvist42], which could not be confirmed in our cohort possibly owing to the limited number of cases examined. We noted, however, that FEP cases had a later AAO compared to SZ cases which could be possibly attributed to the small number of females included in the FEP group that has been reported to develop psychosis at a later age than males [Reference Castle, Sham and Murray76,Reference Angermeyer and Kühn77]. Female cases were also more likely characterized by positive FHP, which is in line with previous studies [Reference Goldstein, Faraone, Chen, Tolomiczencko and Tsuang78,Reference Maier, Lichtermann, Minges, Heun and Hallmayer79].

More recently, analyses in a large UK clinical sample of individuals with psychotic disorders implicated poor social PA and younger AAO to treatment resistance [Reference Legge, Dennison, Pardiñas, Rees, Lynham and Hopkins31]. We provide independent confirmation of the association between social PA aberrations in childhood and inadequate response to antipsychotic medication in FEP cases and treatment resistance in SZ cases. Together, the UK and our studies support the notion that social maladjustment in childhood may be seen as a risk marker for conversion to an early-onset psychosis with adverse clinical course (i.e., treatment resistance). Furthermore, in our substantially smaller sample of cases an earlier AAO was noticed among nonresponders to treatment, which is in accordance with the results of the UK study but requires further exploration since it falls short of statistical significance.

The current study postulates that the interplay of familial determinants, as well as socioeconomic environment could contribute to premorbid maladjustment among individuals who convert to psychosis. As transition to psychosis has been related to social PA dysfunction, the observed joint effect of familial risk and parental socioeconomic position on social PA could possibly imply the involvement of gene-by-environment interaction in SZ pathogenesis [Reference Guloksuz, Pries, Delespaul, Kenis, Luykx and Lin66], even though it is stressed that familial liability do not only mirror increased genetic susceptibility and direct genetic implications could not be interrogated. The negative effect of social PA deficits on age at illness onset and treatment response may also be of important clinical relevance. Social PA impairment has been previously linked to early psychosis onset [Reference Legge, Dennison, Pardiñas, Rees, Lynham and Hopkins31,Reference Vourdas, Pipe, Corrigall and Frangou32] and poor response to antipsychotic treatment [Reference Strous, Alvir, Robinson, Gal, Sheitman and Chakos14,Reference Legge, Dennison, Pardiñas, Rees, Lynham and Hopkins31,Reference Kelly, Feldman, Boggs, Gale and Conley80] therefore early detection strategies targeting premorbid social adjustment in high-risk individuals could facilitate early intervention efforts aiming to delay illness onset and may also inform about potential resistance to treatment.

Acknowledgments.

The authors would like to thank all the patients and their relatives for participating in this research project, and the clinical personnel at Eginition University Hospital, in particular, Evangelia Psarra, Nikos Nianiakas, Vasilis Spatharas, Manolis Kalisperakis, and Vasia Garyfalli for their valuable assistance during patient recruitment.

Financial Support

The current work was supported by research funding from the Theodor-Theohari Cozzika Foundation (Athens, Greece).

Conflict of Interest

The authors have declared that there are no conflicts of interest in relation to the subject of this study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request. Restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for this study. Data could be made available from the authors with the permission of Eginition Hospital Ethical Committee.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1192/j.eurpsy.2020.41.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.