Crime scene photography, originally intended solely as legal proof for judge and jury, has since the 1960s saturated visual media, first in newspapers, then in television and film. The genre is now familiar: the disarranged and lifeless room, the bloodstains or body, the clues. The images fascinate because they are macabre, both as cool, objective, forensic documents and as unsettling emotional scenes in which events that took place outside the frame must be decoded. Studying the development of the techniques, practices, and legal status of crime scene photographs in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century offers a way to understand the complex nature of photography and the process of sight itself. While the police and judicial practices of pre-1960 crime scene photography in England emphasized their objectivity and instrumentality, the photographs themselves reveal references to a much wider visual vocabulary indebted to contemporary aesthetic trends like film noir, documentary photography, and amateur photography. Photography's dual nature as a direct transcription of reality and a human representation was also reflected in its legal status as evidence. While Anglo-American courts ruled that photographs were the product of scientific processes that accurately represented the world, they required them to be authenticated by a knowledgeable witness who could be cross-examined.Footnote 1 As Jennifer Mnookin has argued, “From the first perspective, the photograph was viewed as an especially privileged kind of evidence; from the second perspective, the photograph was seen as a potentially misleading form of proof.”Footnote 2 Crime scene photography's ambiguity as a forensic document highlights the need for historians, as Julia Adeney Thomas contends, to examine historic photographs with a “dual vision” that encompasses both their objective and affective nature and highlights the process of looking and our own position as viewers.Footnote 3 The observable ambiguity of legal photographs allowed them to reveal a range of plausible truths in the courtroom, as Erika Hanna has shown in the context of photographs taken during the Irish Troubles; they contain a wealth of forensic, social, and cultural clues about the scenes they sought to preserve.Footnote 4 The visual effect of the murder crime scene photograph in particular has been memorably defined by Ralph Rugoff, now director of the Hayward Gallery in London, as the “forensic aesthetic.”Footnote 5 This article examines the development of the forensic aesthetic of crime scene photography in the twentieth century through four pairs of English murder crime scene photographs between 1904 and 1958, their combination of visible clues to the crime that was being prosecuted, and aesthetic resonances with other photographic media of their time period. Crime scene photographs also demonstrate a remarkable shift in how photography was used on location as part of the wider twentieth-century revolution in forensic technologies and techniques identified by Neil Pemberton and Ian Burney, and they reveal a collection of ordinary domestic and pastoral scenes at the moment when an act of violence made them extraordinary.Footnote 6

Photography and Truth

Photography's ability to objectively capture and record images from the natural world was heralded from its earliest invention and reflected in books such as Fox Talbot's 1844 Pencil of Nature. Photography's ability to capture likenesses led, by the 1860s, to their routine admission as legal evidence in American and British courts in cases of forgery, to prove the identities of criminals, and later as pictorial evidence of the scene of the crime.Footnote 7 In the 1890s, Alphonse Bertillon at the Parisian Prefecture created standardized systems for photographing criminals and crime scenes, which he exhibited at the 1889 Paris Exhibition and the 1893 World's Columbian Exhibition in Chicago. Bertillon's systems were enormously influential in the fields of both detective policing and professional photography.Footnote 8 The accepted purpose of the crime scene photograph was to record the scene, and the photographs were introduced in court as descriptive evidence, like plans or maps, “accompanied by the testimony of a witness who could testify to their accuracy and authenticity, and who could also be cross-examined.”Footnote 9 In this way, photographs could be made to fit existing evidentiary standards. Photography was used in the Anglo-American legal system to preserve, as Elizabeth Edwards describes it, “pure fact without and beyond stylistic convention,”Footnote 10 informed by the viewer's ability to recognize significant clues. Photography aimed to show the physical nature and position of objects, and to “make images that are uninflected by the process of making the images,” that is, that appeared natural and direct.Footnote 11 Similarly to other scientific uses of photography, crime scene photography “linked the eye to broader scientific systems of knowledge” in which evidence could be preserved and projected into the future.Footnote 12 The judicial assertion of the jury's a posteriori ability to objectively analyze identification photographs and crime scenes photographs has been reinforced by current research into the cognitive neuroscience of vision, which asserts that the visual recognition of faces and of complex visual scenes is precognitive and intuitive. In a process described in visual advertising as “preattention,” what we see is based on visual inferences that depend on the priors imbedded in the neural circuity of the visual cortex.Footnote 13 This visual imagery of crime presented in twentieth-century English courtrooms offered jurors and judges a new sense of accessibility to the crime scene. Just as cheap Victorian pornographic postcards made pornography available to those without the tools of literacy and education, so crime scene photographs allowed those in the courtroom to “read” the photographs in what they saw as a rational and commonsensical way.Footnote 14

Yet legal photography's claim to truth-telling and objectivity was more an epistemic exercise in police investigative authority than a reflection of its legal or forensic status. While courts ruled that photographs were the product of scientific processes and that they were accurate representations, they also required them to be authenticated by a knowledgeable witness, usually the police photographer. After the First World War, new police photographic departments recruited civilian men already knowledgeable about photography directly into what became a separate stream of police training and promotion in the London Metropolitan Police. As experienced photographers, these men were influenced by contemporary aesthetic currents in documentary photography, film noir, and professional portrait and advertising photography. They had some freedom on how to frame and focus the images and how to arrange the resulting photographs in court exhibition volumes. The subjective nature of photographs was reflected in British legal copyright statutes that protected them from 1862 on, and in a series of court decisions that acknowledged that the emotive and visceral nature of crime scene photographs could be prejudicial to jurors.Footnote 15 Barristers’ memoirs also suggest that the objective nature of crime scene photographs was contested in court; J. D. Casswell recalled that in his defense of Mrs. Rosina Cornock for the murder of her husband at the Bristol Assizes in 1947, he managed to blunt the “prejudicial” effects of the photographs of Cornock's head by obtaining an admission that the type of film used would make the bruises appear darker than they actually were.Footnote 16 Crime scene photographs therefore functioned as what Elizabeth Edwards has called “tools of reassurance”; their claim to be informational evidence was largely about asserting the authority of the bureaucratic institutions that produced and archived them.Footnote 17

The Early Years of Crime Scene Photography: Tarrington, Herefordshire, 1904

The incidental survival of crime scene photographs creates an archive of happenstance. In contrast to fingerprint and identification photographs, which were organized into registers and filed in cabinets for rapid retrieval, only cases in which a suspect was identified and brought to trial led to photographs being printed. Crime scene photographs assumed a judicial spectator; they were printed in multiples and mounted in exhibit albums to be examined first by police detectives, then by the director of public prosecutions, then presented at the committal hearings and seen by the defense counsel, defendant, and the magistrates.Footnote 18 When the case proceeded to trial, they were viewed by the judge and members of the jury.Footnote 19

The act of looking at the crime scene photographs took place in a social context that mediated their importance, notably in institutional offices and the courtroom, whose functions were to prosecute crime. Because archived case records for the Assize and Central Criminal Court from this era do not include court transcripts, we can only extrapolate from the pre-trial depositions how they were referred to and used during trials. The photographers’ depositions generally included statements to the effect that “These photographs are produced from the untouched negatives that are in my possession,” linking the negative to the chain of evidence that had to be preserved instead of discussing what had been moved or altered in the room before the photograph had been taken.Footnote 20 Depositions of police officers rarely refer to the photographs, except to note the position of objects or rooms. Likewise, there is little information about the reaction of the jury, judge, or defendant to the photographs. Newspaper reports sometimes make note of a particularly strong emotional reaction on the part of the jury, such as the revulsion of the jury seeing photographs of the dismembered body of Emily Kaye in the murder case against Patrick Mahon at the Lewes Assizes in 1924.Footnote 21 Generally, however, the files are silent on the courtroom use of these photographs.

Many of the archived cases that refer to photographs in the exhibitions listings no longer retain them in the file, and most of those that tend to survive in the pre-1960 period are from the Central Criminal Court files, taken by the London Metropolitan Police. These surviving photographs are not representative of the wider incidence of crime in London, especially the gender of victims. While the London Metropolitan Police Registries of Deaths by Violence record almost twice as many adult females as adult males murdered between 1933 and 1953, the proportions represented in the accessible archived crime scene photographs are roughly equal between male and female.Footnote 22 After the 1950s, crime scene photographs are more likely to appear in the Assize and Central Criminal Court files and in their original albums. In borough police forces, individual detectives or photographers sometimes kept their own copies of an exhibition album and later donated them to archives, where they have few contextual documents and remain mostly unidentified.Footnote 23

The National Archive collection of crime scene photographs is one of the few twentieth-century collections in the world to retain its archival linking to assize and Central Criminal Court depositions and police files. The collection as a whole, and the following sample images, point to the interrelatedness of criminal investigations, technologies, legal practices, and aesthetic context. Crime scene photography developed as an important tool in twentieth-century English police investigations of suspicious deaths and as part of the forensic shift from the laboratory to the crime scene.Footnote 24 Yet the earliest of these photographs were not necessarily forensic outside of their presentation as court exhibits, since they were usually taken by local civilian photographers, and the contents of the images retain a visual opacity in which the significant clues are unclear. In the earliest English deposed photographs, the forensic ideal of a preserved crime scene was not met or even simulated.

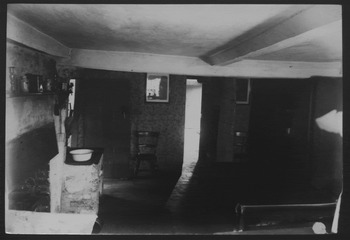

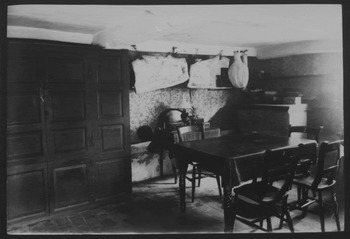

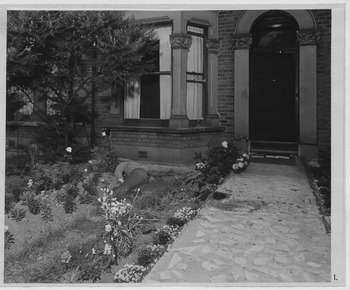

The first set of archived interior crime scene photographs in the National Archives collection are from a 1904 case at Sollars Court Farm, Tarrington, Herefordshire.Footnote 25 John Powell, a depressed farmer recovering from influenza, shot and killed his cousin Ada Meek, who owned the farm and lived there with Powell, his wife, and the housekeeper. That morning, the four of them had sat down together for breakfast in the kitchen. While Meek was washing and drying the dishes and Powell was sitting in a chair by the fire, the gun he was holding went off, and Meek was killed. There was no clear motive or family disagreement. Four of the five photographs that accompany the depositions depict from various angles the room where the crime occurred. Although the technology of flash powder, a mixture of magnesium powder and potassium chlorate ignited by hand in a pan to produce bright light explosions, had been in use since the late 1880s, these photographs relied instead on the natural light coming from the window and the open kitchen door to provide enough illumination for the long exposure. The effect is of someone coming from outside, shedding light onto the scene of the crime. The light is focused on the washing-up bowl on a table by the hearth, where, according to the depositions, the shooting had taken place (figure 1). Another photograph shows the chairs rearranged neatly around the table, numbered on the print to show where each person had sat for breakfast an hour before the shooting. Signs of domestic prosperity crowd the background: a lamp, a houseplant, and what appear to be a ham and sides of beef hanging from the ceiling (figure 2).

Figure 1 Sollars Court Farm kitchen, view from window, TNA ASSI 6/39/6.

Figure 2 Sollars Court Farm kitchen, view from door, TNA ASSI 6/39/6.

These photographs illustrate the transitional nature of early crime scene photography in England. The room had been already cleaned, and John Powell had admitted the shooting, and there is no evidentiary reference to the photographs in the depositions.Footnote 26 The outcome of the trial is also unknown, as the Herefordshire indictment records for the autumn of 1904 were destroyed by enemy action in the Second World War.Footnote 27 The table photograph (figure 2) seeks to reconstruct the moments before the crime rather than the aftermath, as well as to suggest the emotions hidden beneath the disrupted domestic routine. As Ross Gibson has argued, while forensic activity is “a cool, slow, and deliberate process of making meaning,” crime scene photographs are suffused with feelings that must be part of their historical interpretation.Footnote 28 These photographs can be seen “not as a series of documents, but as a series of sensory emotional enablers in which the indexical and forensic on the surface of the object are also merely the surfaces of possible meaning.”Footnote 29 The photographs are also transitional in that, rather than a police officer or detective, the photographer was a local man, Frederick Richard Tainton. He was listed in the 1901 census as an “artist: photographic” and was scheduled to testify at the Hereford Assizes.Footnote 30 His photographic technique is visibly influenced by the Pictorialists, the first fully international group of advocates and practitioners of photographic art, who developed a distinctive soft-focus aesthetic to make photos seem more like paintings or drawings.Footnote 31 The rural setting of the farmhouse and its old-fashioned kitchen also reflect Pictoralism's typical subject material. Identifying both the contemporary photographic aesthetics and the criminalistic search for clues shows the complex nature of legal evidence as well as the early development of forensic tools.

The photographs also reflect the Herefordshire Constabulary's enthusiastic interest in the legal use of new photographic technology. As Stefan Petrow observed, police photography had by the 1890s become “a useful supplement to personal files, a measure to build confidence, a symbol of efficiency and professionalism … a symbol of a systematic approach to investigating crime and criminals,” even though it had yet to be formally introduced as a police specialization in England.Footnote 32 After the First World War, amateur photographic knowledge began to be consolidated into the larger English police forces by the recruitment of amateur photographers into specialized photographic departments. In 1901, the London Metropolitan Police began a six-month trial in which members of the Fingerprint Branch of the Criminal Investigation Department took photographs themselves rather than hire professionals. In this period, 162 negatives were taken and 996 copies made, at an average cost of one-fourth of the fee charged by professional photographers. The in-house photography “saved time in production and ensured secrecy,” and the excellent results were “owing to PC Deacon's knowledge and economy in the use of the various chemicals and generally to his efficiency as a photographic operator.”Footnote 33 New equipment for the nascent Photographic Branch had to go through a laborious system of requests and Home Office approvals. In 1905, the Criminal Investigation Department requested funds for the purchase of a seven-inch focus Goerz lens, which cost £7.10. By 1916, the covert photographing of suffragettes required the purchase of a reflex camera, which could be focused in a split second rather than relying on tables to tabulate distance. By 1931, this camera had worn out and was replaced by a Thornton Pickard Ruby Reflex camera. Prints were dried on a line in front of the fire until 1932, when the increasing volume of large prints necessitated the purchase of a commercial photo dryer.

Police Photographic Expansion: Soho Square, 1933

In the 1930s, police photography in England began to expand rapidly, with published guides to current techniques emphasizing its objective forensic and judicial uses. In the 1930s, the courts and the police viewed photographs of crime scenes as similar to drawn plans, with equivalent truth-telling properties. In a chapter on photography in Teignmouth Shore's 1931 collection on crime and its detection, Captain W. J. Hutchinson, chief constable of Worcester, argued for the evidentiary interchangeability of photographs, sketches, and plans, which all provide both impressionist and perspectival information about the crime scene.Footnote 34 A few years later, Metropolitan Police Inspector J. O'Brien, in the 1936 article “Simple Photography for Policemen,” also implied that the truth-telling properties of forensic photographs were not always apparent on the surface and that they should be taken and recorded as taken immediately: “Any attempt to reconstruct a scene must obviously destroy the value of any photographs taken, and it is quite certain that they will not be admitted as evidence.”Footnote 35 The evidentiary value of the photographs was not in what they themselves contained in the frame but rather in their importance as a verifiable document of the scene in the aftermath of a crime.

At the same time, the development of distinctive local visual styles in crime scene photographs points to the importance of wider visual culture. English murder cases in general also developed a specific genre, typified by wide-angle side shots of the room or outdoor scene, and a reticence in depicting details of the body and particularly the face of both male and female victims. Full-body and close-up facial photographs of the victim's body rarely appear until the 1950s, and then only in accompanying morgue photographs. Unlike early American crime scene photographers, English police also tried to keep both spectators and detectives out of the photographic frame. Likewise, while American newspapers published increasingly explicit photographs of crimes and violence in the 1930s and 1940s, in Britain the publication of crime scene photographs remained fairly restrained.Footnote 36 British newspaper photographers were rarely close to the actual scene of crime before the 1960s, and most English newspapers instead printed portrait photographs of murder victims in life. Russell Roberts has shown how the Daily Herald’s editors cropped and enhanced portraits to infuse the images with a new pathos in the context of crime reporting between 1935 and 1962.Footnote 37 English daily newspapers also depicted the outside of houses or areas near where crimes took place as visual illustrations of the type of crime depicted. Detectives or pathologists arriving or leaving the scene of crime were also photographed. In the notorious case of wealthy divorcée Elvira Barney's shooting of her lover Michael Stephen in July 1932, the Daily Mirror featured a photograph of Superintendent Hambrooke of Scotland Yard leaving the house while police photographers and fingerprint experts were at work inside.Footnote 38 In at least one case, a freelance journalist stole a book of exhibition photographs from a counterfeiting trial at the Central Criminal Court, claiming he had found them on the floor, and three of the images were published in the Daily Express on 10 July 1937.Footnote 39 Both he and news editor James Wilson claimed they had not seen the stamp “Central Criminal Court” on the cover of the exhibition album. While English newspapers did not publish graphic crime scene photographs as in America, they recognized that crime sells. As the Carlisle Conservative Newspaper Co. Ltd. told the Royal Commission on the Press in 1947, “Much as we deplore it, the fact remains that the public, as a whole, revels in stories of crime and the more sordid stories of human tragedy.”Footnote 40

The amateurism of early crime scene photography was displaced in England and elsewhere by professionalization by the 1930s. Aided by advances in photographic technology and inspired by Bertillon, the practice of institutional crime scene photography developed simultaneously in London, New York, Sydney, Mexico City, and other major centers.Footnote 41 Technological advances in cameras allowed the introduction of wide angles and a proliferation of images, while separate tracks developed for forensic photography as a field of work. Police photographers developed different tools and aesthetic techniques for specific crimes, such as the use of photographic filters and ultraviolet light to detect forgery, close-up photographs of tool marks in burglary cases, and images of buckets, bandages, and beds in cases of suspected criminal abortion.Footnote 42 Crime scene photographers shared technical, aesthetic, and teleological languages, while at the same time developing their own local styles, reflecting the twentieth-century development of global and imperial police relationships identified by Georgina Sinclair and Chris A. Williams.Footnote 43 The international exchange in the genre and form of police photography was made possible by articles in professional publications such as the Police Journal and the Metropolitan Police College Journal, and at conferences such as the International Criminal Police Congress in Monaco in 1914.

For example, New York Police Department photos in the 1910s and 1920s were attributed to several detectives in the Criminal Investigation Department. They used a wide-angle 25 mm lens and, to take overhead shots, a three-legged metal tripod, its legs visible in many of the surviving photos.Footnote 44 In Scotland, forensic photography developed as part of criminal and civil investigations carried out through the forensic departments of the University of Edinburgh and the University of Glasgow.Footnote 45 John Glaister Sr. and John Glaister Jr., University of Glasgow Forensic Medicine and Public Health regius professors and medico-legal examiners for the Crown from 1898 to 1962, did much to popularize the use of photography in forensic investigation, and their archives include over 300 photographs taken at the scenes of crimes and during post-mortem examinations.Footnote 46 As Nick Duvall has argued, forensic photography was a point of intersection between forensic medicine and police practice; many of the photographs shown in court in Scotland were subsequently destined to circulate in other contexts: projected as lantern slides in the Glaisters’ lectures, published in newspapers and as figures in books, and displayed in the Forensic Science Department's museum.Footnote 47

The rise in the number of crime scene photographs in the courts in the 1930s mirrored the increasing saturation of visual images in British popular culture: “Advertising hoardings brought images onto the street, the cinema offered hours of visual entertainment, and cheap illustrated publications achieved unprecedentedly large circulation.”Footnote 48 These photographs were largely mechanical images in black and white: snapshots, newsreels, newspaper and magazine illustrations, and feature films. Black-and-white photography was strongly associated with documentary truth, order, and classification and was used for scientific research to record evidence in the fields of medicine, botany, and the natural sciences, including anthropology, archeology, sociology, and astronomy.Footnote 49 So powerful was the association of black-and-white images with documentary truth that it influenced fine art, such as Picasso's newsreel evocation in Guernica, and Second World War propaganda.Footnote 50 Black-and-white photography was also associated with the medium's documentary and truth-telling functions.Footnote 51 In the Victorian period, photography was seen as objectively recording what was placed in front of it, as “innately and inescapably performing a documentary function.”Footnote 52 For instance, in England, the late Victorian photographic survey movement sought to create a photographic record of vanishing churches, cottages, and folk customs for future generations.Footnote 53 As the historical concept of “documentary” photography evolved in the 1930s and 1940s, documentary photographers sought to create photographs that would act “as both conduit and agent of ideology, purveyor of empirical evidence and visual ‘truths.’”Footnote 54 London photographers George Davison Reid, Margaret Monck, Wolfgang Suschitzky, Cyril Arapoff, and Bill Brandt used their photographs to comment on the vitality of London street life, including urban poverty and illicit sexuality.Footnote 55 As Stephen Brooke has shown in his analysis of the London street photography of Roger Mayne, mid-century documentary photography often used the technique of juxtaposition, such as the movement of children playing against the static lines of streetscapes, or images expressing the dichotomy between social classes.Footnote 56

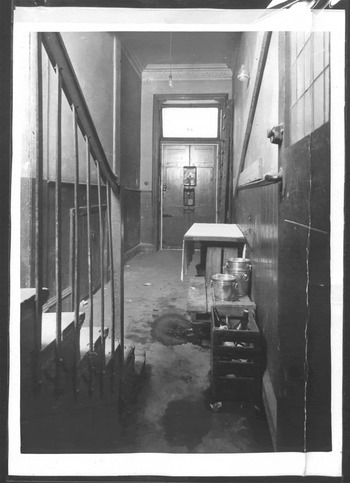

Cinema also provided a visual language of stark morality and emotional tension in the 1930s. By then, there was one cinema seat for every fifteen inhabitants in Britain, with a market second in size only to that of the United States.Footnote 57 Popular American gangster films like Little Caesar (1930), The Public Enemy (1931), and Scarface (1932) depicted a criminal underworld where evil is narrated but ultimately punished.Footnote 58 British film noir, pioneered by Alfred Hitchcock, focused more on psychological tension. In his early films, Hitchcock used the camera to mimic characters’ points of view, and close shots and rapid editing to maximize fear, empathy, and anxiety in the viewer. His early films The Lodger (1927), Blackmail (1929), and Sabotage (1936) used London landmarks as integral elements of the suspense.Footnote 59 Noir style was more generally associated with unbalanced compositions, low-key lighting, vertiginous angles, night exteriors, extreme deep focus, and a wide-angle lens.Footnote 60 Film noir also depended for its locales on tightly concentrated urban spaces, recognizable to police and criminals. Noir scenes, like crime scene photographs, were set in buildings, streets, roadways, landmarks, and passages of all kinds.Footnote 61 Crime scene photography borrowed from the stark graphic pictorial quality and emotional tension of these cinematic genres, as seen in the tightly framed and high-contrast photograph of the back staircase in Soho Square (figures 3, 4). Black-and-white images were also regarded as more authentic than color photographs, which were associated with advertising and entertainment: travelogues, musicals, cartoons, show cards, calendars, magazine and paperback covers, and billboard advertisements.Footnote 62 The portrait photographer Yevonde wrote that although the technology of color film was well advanced by the 1930s, color photographs were not popular: “People had become so used to photographs in black and white that a color photograph seemed to them to be an error in taste.”Footnote 63

Figure 3 Rear of Bellometti's Restaurant, Soho, view from staircase, TNA CN 27/10.

Figure 4 Rear of Bellometti's Restaurant, Soho, view from door, TNA CN 27/10

The forensic aesthetic in England continued to evolve and diversify with the technical advances in photography and the proliferation of police photographic departments. From the 1930s, the 181 separate forces in England and Wales began to develop more specialized professional techniques and departments. Clive Emsley has argued that this shift towards detection and forensics came about partly in response to Home Office pressure and the campaigning of A. L. Dixon's 1930s Departmental Committee on Detective Work for England and Wales, which advocated photography courses for detectives and photographic equipment for both large and small forces.Footnote 64 With no formal training except a brief introductory course at Hendon, police photographers had to enter the force as skilled operators and also learn on the job. The development of photography in provincial forces depended on local funding and on the local presence of a forensic science laboratory or other specialized college.Footnote 65 The Bradford Technical College, for example, in the 1930s provided research staff and equipment that allowed the Bradford police to use ultraviolet and infrared rays to detect forgery; the Bradford City Police force was the only one in 1936 to regularly use color photography.Footnote 66 Likewise, an expanded headquarters for the Manchester City Police Department in 1937 allowed space for the developing and drying equipment necessary for a new Photographic Department, which in 1938 took 1,695 photos and prepared 15,158 prints.Footnote 67

In the London Metropolitan Police, the Photographic Branch developed first as part of Criminal Investigation Department at Scotland Yard Headquarters, and then, with an increased workload, moved to C3 as a section of Fingerprint Branch in 1934.Footnote 68 In 1933, the Photographic Department took 45,522 photographs, and in 1934 the number increased to 70,218.Footnote 69 In 1934, police photographers recorded 251 crime scenes in London and attended court 322 times. The Photographic Branch developed a separate path of entry and promotion; applicants had to possess “a thorough knowledge of photography” and had to pass a technical exam to advance in rank. Police photographers had to be knowledgeable about contemporary equipment and the various uses, genres, and aesthetics of photography.Footnote 70

The surviving archived photographs suggest that photography, while not used in all cases of serious crime in the London Metropolitan area in the 1930s, was used in high-crime neighborhoods such as Soho in C Division. Soho had a reputation for respectable entertainments in theatres, restaurants, and nightclubs, but also for organized and haphazard criminal activities such as illegal gambling clubs, protection rackets, homosexuality, and prostitution.Footnote 71 For instance, one of the arguments the Metropolitan Police Photographic Branch made for the purchase of a new three-light camera unit in 1934 was that the flash powder previously used had twice set fire to the drapery in the “bohemian rendez-vous” the Caravan Club on Endell Street.Footnote 72 In the police raid on the club, Inspector O'Brien of the Photographic Department found it was too crowded to photograph the patrons and so took pictures of the empty interior after they had left.Footnote 73 The police reports describe the outrageous sexual and drunken behavior of male and female patrons, but all of this escaped the camera. Instead, photographs of the exotic and shabby interior had to represent in court the debauchery that had taken place. The contrast between what Judith Walkowitz has described as “the decorous front stages of Soho's food industry and its gritty back region” also emerges in a case featuring Bellomettis’ restaurant in Soho Square in 1933.Footnote 74 Varnavas Loizi Antorka, a Cypriot silver washer who had been fired by chef Boleslav Pankowski earlier in the day, returned with a revolver and shot at Pankowski three times as he came down the back staircase of the restaurant.Footnote 75 Two of the bullets entered his body, while the third ricocheted off the floor and hit another waiter in the leg. The other waiters overpowered Antorka, took the gun, and handed both over to police. Pankowski survived until the next day in hospital but did not regain consciousness. Two crime scene photographs were taken by the police photographer, likely that evening or the next morning. One depicts the scene looking out from behind the dingy back staircase towards the closed outer door. Nestled behind the trestle table are rubbish bins (figure 3). The bloodstain in the center of the floor is echoed by other stains and the mess of the cans and empty bottles. Another less defined stain in the foreground could be from the injured waiter. The second photograph shows the same scene from the open outer door, from the point of view of Antorka as he would have entered the room (figure 4). Here the eye is drawn to the white tablecloth on the table, which hides the bottles. Its ghostly movement in the current of air from the open door suggests a life that is absent in this cramped, narrow frame.Footnote 76 The photographs expose the claustrophobic closeness of the atmosphere, the grim textural detail of the dirt and debris on the floor, and the dark bloodstain. The shabbiness of the scene and the pool of blood correspond to the visual language of urban poverty and crime represented in the drawings in the “yellow press” and publications like the Police Gazette of the late nineteenth century, as well as early documentary photography, which would have been understood by the Central Criminal Court judge and jury to whom they were shown on 27 June 1933.Footnote 77 The dramatic framing of the two perspectives on the stairway and the doorway would also have heightened the theatricality of the other evidence and deepened the impact of Antorka's crime.

These crime scene photographs are examples of the institutional framing of one scene as part of wider criminal neighborhood. Like Eugene Atget's mysterious landscapes of Paris at night, “dead-end streets in the outlying neighborhoods [that] constituted the natural theater for violent death, for melodrama,” the crime scene photographs’ image of back stairs squalor aligned the defendant with a criminal class and possibly ethnic type.Footnote 78 Like the photographs of the Caravan Club, the depopulated frame suggests the crime scene photograph's ability to go literally behind the scenes to reveal hidden rooms and stories, and to stand metaphorically for the crimes that took place therein. While the photographer used the camera to objectively record the staircase and bloodstain for the judge and jury, his framing and stylistic techniques also reveal links to the visual languages of film noir and the documentary tradition. The bloodstain in the center of both frames unites both the objective search for clues and the decoding of affect in the aftermath of the murder. Antorka was found guilty but recommended to mercy by the jury, as they argued he had not intended to shoot Pankowski when he returned home to change clothes and plead for reinstatement until he saw the revolver in his drawer and decided to bring the gun to scare the chef.Footnote 79 Justice Humphreys pronounced the death sentence, against which Antorka unsuccessfully appealed. He was executed at Pentonville Prison on 10 August 1933.Footnote 80

Postwar Crime Scene Photography and the Expansion of the Forensic Aesthetic

After the Second World War, the use of crime scene photography expanded to more English police forces as one technique to deal with diminished police manpower after the war. For example, in 1939, the London Metropolitan Police Force numbered 19,500 men. By the end of the war this number had dropped to 12,000, and even with recruiting drives the total strength of the force remained abysmally low at 14,000 in 1946.Footnote 81 Fewer men and a shifting population led the Metropolitan Police to develop new investigative techniques, with increased training in specimen collection and the re-establishment of the Hendon Police Laboratory in New Scotland Yard Headquarters at Westminster in 1948.Footnote 82

Postwar suspicious death investigations highlight the effects of psychological trauma, austerity, and migration in the larger atmosphere of exhaustion, anxiety, and difficult adjustment to peacetime life. The best practices of forensic photography extended to including more types of cases, more stringent techniques, and the application of new technological advances. In 1948, Jack Augustus Radley, a forensic document examiner, published the first book solely on the topic of photography in crime detection, including material on microphotography and photography using ultraviolet radiation and infrared.Footnote 83 The book also set out a more stringent view of how the crime scene of a murder should be photographed, including views of the scene itself, points of entry and exit, any traces of the crime, and the point of view of any witnesses.Footnote 84 While Radley argued that “no police officer would attempt to dogmatise on what should and what should not be photographed in a murder case,” other postwar lectures, courses, and seminars offered in the United States and Britain sought to do just that.Footnote 85 New editions of forensic textbooks also suggested how the practices of police photography were evolving. First published in Sweden in 1949, Crime Detection: Modern Methods of Criminal Investigation by Chief Superintendent Arne Svensson of the Criminal Investigation Department Laboratory in Stockholm and Superintendent Otto Wendel discussed the best ways in which science and technology could be used in support of the police. In the 1955 English edition, the authors gave instructions for a photographic process that applied “a systematic scrutiny from all angles.” For instance, “A house where the murder has been committed will generally be photographed from the outside to show the roadway, garden, outside doors and outhouses” to illustrate how the felon gained entry and exit.Footnote 86

North Ilford, 1952

After the war, the archived crime photographs of the Metropolitan London Police included more scenes of suburban crime, expanding the pre-war focus on urban poverty. Wartime photojournalism, heavily censored, had emphasized the mutual bonds and affection of the family, including the sleeping shelterers in London tube stations captured by Bill Brandt for the Ministry of Information, family embraces at railway stations distributed to newspapers through agencies like Topical Press, Keystone Press, or Fox Press, and similar photojournalist essays for Picture Post.Footnote 87 This turn away from modernism to more traditional themes was mirrored in the larger visual culture of the 1940s and 1950s. While wartime film shortages and paper rationing had meant a constriction of advertising, the postwar birth of a new consumer culture led to a shift marked in London in 1951 by the Festival of Britain and by the International Advertising Conference, with thirty-eight national participants.Footnote 88 To sell goods in an increasingly saturated market after 1954, advertisers turned to photographic naturalism, the use of human drama, and the expanding use of color.Footnote 89 They were aided by large libraries of stock photographs that catered to magazines, newspapers, and other foci of middle-class taste and included popular images of babies, children, animals, families, and domestic scenes.Footnote 90 The expansion of this type of advertising photography in the 1950s was also part of the emergence of new cultures of consumer capitalism in an age of postwar affluence.Footnote 91 Likewise, the increasing affordability of the personal camera meant that by the end of the war amateur photography was commonplace, with more families able to photograph themselves and collect and display their photographs. Annebella Pollen has argued for the complex personal significance and social value of family albums and mass photography; this focus on images of the family and the home also forms a backdrop for crime scene photography.Footnote 92 Advertising and amateur images of the happy family are the implicit foil to the scenes of domestic murder captured in postwar crime scene photography.

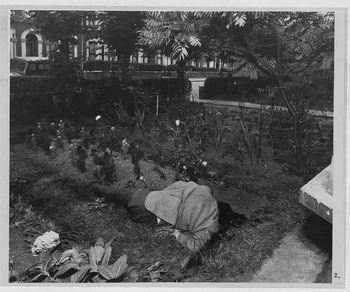

The crime scene photographs in next example were taken in a North London suburb in 1952. They disrupt the familiar postwar image of home and family: a tidy front garden with carefully set flowers and lace curtains at the window has a dead body crumpled face-down on the lawn (figure 5). Three uncollected newspapers and the open door hint at the disruptions in the household that led up to this moment. As Alexa Neale's research has shown, crime scene photographs present a perversion of the established genre of the domestic.Footnote 93 Thomas and Elizabeth Hodges had been unhappily married at 74 Elgin Road, Seven Kings in Ilford, Northeast London.Footnote 94 Elizabeth had been having an affair with fellow teacher Bill Moore and was on the point of leaving Thomas. On Friday, 8 September, Thomas had gone to Beachy Head to commit suicide, leaving a letter for Elizabeth. Finding that he could not go through with it, he returned to convince her to stay but found her suitcase packed and by the door and Bill on the way over. Thomas put a chopper knife under his coat, and when Bill arrived in the front garden, stabbed him in the head. The crime scene photograph captured the aftermath: the murdered lover lying in the flower bed and dirt scuffed onto the path (figure 6). After the police were called, Thomas went inside to sit on the bottom of the steps, saying, “I wouldn't have done it if he hadn't walked out with my wife and a suitcase.”Footnote 95 As the story unfolded, the ideal middle-class domestic front suggested by the neat front garden continued to unravel. When the couple married in 1947, Elizabeth was pregnant with an American sailor's child, whom Thomas treated as his own. He was a manager at the Commonwealth Bank, where he had been embezzling funds to buy his wife gifts to regain her affection. He had tried to win the money back by gambling but failed. The body in the tidy flower beds visually narrated the implosion of three middle-class milieus: home, marriage, and career, bringing the forensic aesthetic to a respectable suburban neighborhood. Perhaps because of his attempts to preserve his marriage in the face of his wife's infidelity, Hodges was found guilty at the Central Criminal Court of manslaughter instead of murder and sentenced to seven years in prison.Footnote 96

Figure 5 74 Elgin Road, Ilford, view from door, TNA CRIM 1/2248.

Figure 6 74 Elgin Road, Ilford, view from street, TNA CRIM 1/2248.

Crime scene photography, like advertising photography, invested the home and the human face and form with emotional significance, but in mirror image to signify loss and disruption. The police photographer, according to the contemporary conventions, has also been careful to show the victim's body turned away from the camera so as not to show his face. This reticence to display the face or nude body of male or female victims at the scene of the crime was, after the 1950s, undermined by the courtroom exhibition of a book of mortuary photographs. These images showed the unclothed body of the victim during the postmortem, with a visual emphasis on the wounds that led to death, and one of the images showed the body of Bill Moore.Footnote 97 The contrast between reticence and scientific openness reflected long-held beliefs about the acceptable motives and arenas for displaying the naked human body; as Philippa Levine observes, “Unclothedness for properly aesthetic or for neutrally scientific ends is permissible and even to be encouraged, while pornography is an undesirable and a dangerous category.”Footnote 98 In the 1950s, public reticence around showing bodies and crime scenes began to shift in the wake of the discovery of the serial murders of John Reginald Christie at 10 Rillington Place in Notting Dale, London. Frank Mort has shown how crime scene photographs taken by Chief Inspector Percy Law from Scotland Yard's Photographic Department, documenting the discovery of six female bodies in Christie's flat and back garden, were seized upon by print journalists as a powerful new visual language of crime. Images of the bodies found in the house were published in daily newspapers as part of a new style of aggressive reporting, in articles titled “House of Death,” “House of Murder,” and “Garden of Death.”Footnote 99

Bridgewater Canal, 1958

The 1953 Rillington Place murders heralded a change in English press coverage that gave the crime scene new forensic and journalistic visibility.Footnote 100 The increasing emphasis on the visual depiction of crime meant that the demands of police photographic departments continued to increase. In 1957, the Photographic Section of the London Metropolitan Police visited 588 scenes of crime compared to 425 in 1956, and more students were attending fingerprinting and photography courses.Footnote 101 The branch now had twenty-three cameras, but only five were useful for crime scenes and often on loan, so that “on several occasions the photographing of the scene of the crime had to be deferred until the following day through lack of a suitable camera.”Footnote 102 The number of photographs taken at each scene increased, and the types of photographs also changed, as reflected in forensic textbooks. In the revised 1965 American edition of Svensson and Wendel's book, now titled Techniques of Crime Scene Investigation, the authors set out a much more elaborate process of crime scene photography, in which photographs were taken from the inside out but arranged for the courts “in a series which illustrate[s] the events of a crime in a logical sequence,” showing “the overall village, the way to the house, detailed views of the scene, and evidence and the escape path.”Footnote 103 The increasingly intricate and narrative focus of crime scene photography was reflected in changes in how the photographs were seen and archived.

Surviving English exhibition albums in murder trials by the 1950s were longer and often multiple. For example, in cases of manslaughter by abortion, the earliest archived photographs of that decade show only the empty rooms where suspected abortions had taken place. But by the mid 1960s, exhibits included photographs of every room in the flat of the suspected abortionist, as well as full-length nude photographs of the victims, often with close-ups of their faces and, in at least one case, of the fetus.Footnote 104 Such photographs, unconnected to forensic evidence, derived their evidentiary impact from the depiction of the vulnerable face and bodies of the young women. Photographic conventions shifted in infanticide cases in this period as well. The Infanticide Acts of 1922 and 1938 had reduced the offense of a mother convicted of killing her infant from murder to manslaughter if the “balance of her mind was disturbed.”Footnote 105 In order to prove that the mother had killed her child, photographs from infanticide cases from the 1930s and 1940s almost always depicted wounds on the infant body. By the 1950s, the photographic frame was widened to include the setting in which the infant had died. In the 1958 case of twenty-seven-year-old Mary Bracken, who had jumped into the Bridgwater Canal at Sale in Cheshire with her seven-week-old son John, the exhibition album was arranged to show the trajectory of her journey, with two photographs of the canal path down which she walked (figure 7). The photographer stood on a hill focusing on a long view of the path and river; this vantage point unites the graveyard in the left of the frame with the path and the river on the right. The following photograph focuses more narrowly on the fence seen from above in the previous photograph, showing the empty perambulator by a gap in the boards and the edge of the canal where Mary was rescued but John drowned (figure 8).Footnote 106 This evocative photograph compresses the loss of the child into one image: the empty perambulator facing the viewer, the gap in the wall, and the wide river behind. The image is elegiac, haunting, and beautiful. It reflects the compassion shown to Mary by her husband, who detailed their former happiness and her increasing illness, and ended his deposition with the assertion, “I am prepared to stand by my wife.”Footnote 107 The policeman who arrested Mary and charged her with infanticide and attempted suicide (the latter charge was dropped) also noted, “I have found this family to be of the very highest quality, and the accused comes from good stock, I have met the husband quite frequently and he has done all he could in this particular case.”Footnote 108 Because of the family's respectability and support, because she had pleaded guilty, and because of the clear evidence of mental illness, Mary was found guilty but released into the care of her husband.

Figure 7 Bridgwater Canal, view from hill, TNA ASSI 84/242.

Figure 8 Bridgwater Canal, view from path, TNA ASSI 84/242.

These particularly poignant crime scene photographs reflect a wider shift in postwar landscape photography. While nineteenth-century photographs of landscape were primarily topographical, as in the work of Roger Fenton or Francis Firth, Bill Brandt's postwar landscapes, taken between 1945 and 1950 and published in Lilliput, Harper's Bazaar, and Picture Post and collected as Literary Britain in 1951, were the first twentieth-century landscapes to imbue the land with an elegiac sense of loss amidst natural beauty.Footnote 109 Brandt was more concerned with feelings evoked in landscapes of 1940s than an accurate record of the view; this emotional resonance would be echoed in the later landscape photographs of Ingrid Pollard, Eric de Maré, and John Davies.Footnote 110 In the final crime scene photograph in this set, the pastoral river scene is depopulated, empty, and saturated with a sense of loss.Footnote 111 The focus on the bleak landscape evokes an emotional response of compassion for the mother as well as the child. This image in particular illustrates that crime scene photographs, like the museum photographic collections discussed by Elizabeth Edwards, should be read not only as “a series of documents but as a series of sensory emotional enablers in which the indexical and forensic on the surface of the object are also merely the surfaces of possible meaning.”Footnote 112 Our observations and attempts to decode them emphasize their doubled nature and our ambivalent position as witnesses. As Julia Adeney Thomas noted about the postwar work of Japanese photographer Ihei Kimura, looking at these photographs demands a dual consciousness, as “one not only sees the objects in the frame but also grasps oneself as the bearer of sight, the witness not only of the image but of oneself as a witness.”Footnote 113 For historians of crime and forensics, this self-reflexive witnessing emphasizes our inability to definitively solve the inherent mysteries in the study of historical crime, while at the same time it encourages us to keep looking.

Conclusion

From the 1960s, police photography had to adapt rapidly to the proliferation of new film techniques, processes, and operators. A report for the Metropolitan Police from January 1980 charted the rapid changes in the use of photography from 1963 to 1980: “At its inception, the section consisted entirely of police officers and their work was almost entirely related to scenes of crime. They used straightforward equipment to take black-and-white still photographs and were responsible for developing and printing them in a simple darkroom.”Footnote 114 But in seventeen years, the photographic section of B12, then C3, doubled in size and increasingly employed professional civilian staff to operate more sophisticated technical equipment.Footnote 115 By 1980, police photography was used not only in the traditional evidentiary areas of fingerprints, prisoner photographs and copying services, scene of the crime photographs, and Ciné film but also increasingly in other departments such as Public Information, the Metropolitan Police and City Fraud Department, Hendon College, the Police Laboratory, Special Branch, C11 Criminal Intelligence, and Traffic Areas. The report detailed the continuing debates over color processing, concerns about the unsupervised use of Polaroid photography, and the promising new area of video-camera recording surveillance. While the report recommended a tightening of departmental control over the photographic processes and equipment spread across the force, its approval of a further shift to civilian photographic staff also pointed to the end of an era of police photography as a branch of police detection.

The increased police use of crime scene photographs after 1945 also demonstrates the heightened importance of photography as visible forensic evidence presented to the judge and jury. The images represented in crime scene photographs became an increasingly vital component in the prosecution and reporting of crime, just as the cinematic depictions of policing in postwar films and television programs became central to public perceptions of crime and its investigation. Crime scene photography attracted amateur photographers to the police force, and crime scene photographs demonstrate how police photographers borrowed from or reacted against other visual genres, including Bertillonesque criminalistics, Pictorialism, documentary photography, and postwar landscape photography. The idealized images of the domestic and the family in advertising were an invisible foil for cases of family rupture and violence, while cinema and art photography provided examples of how to convey emotional tension visually. Even though the ideal of police photography, as expressed in forensic textbooks and policing articles, was to provide a direct and objective transfer of facts to the courtroom, its legal status as evidence that had to be substantiated by a witness, as well as its inferential visual nature, demonstrate that crime scene photographs were also allusive, subjective, and evocative. As historical sources, crime scene photographs are constantly remade by the context of their viewing and the eye of the viewer; they remind us as historians that our own sight may perceive forensic truths on the surface but that we can never definitively fix and stabilize the shifting layers of affective meaning underneath.