Shortawn foxtail is a winter annual weed of the Poaceae family. This species is native to North America but has invaded other regions throughout the Europe and temperate Asia (Cope Reference Cope1982; U.S. Department of Agriculture Natural Resources Conservation Service 2016). In China, shortawn foxtail is widely spread in the east, south-central, and southwest regions and parts of the Yellow River basin (Guo et al. Reference Guo, Liu, Li, Yuan, Du and Wang2015). It usually grows in low-lying riparian land, along riverbed shores, or in wet soil, and is commonly found in wheat and canola fields (Huang Reference Huang2004; Wang and Qiang Reference Wang and Qiang2007). The life cycle of shortawn foxtail is similar to that of wheat. Generally, it emerges in late October or early November and matures in May to June the following year. An individual plant is capable of producing more than 7,300 seeds on average (Zhang Reference Zhang1995). The seeds are easily detached from the plant and are dispersed by wind or water over long distances. Therefore, its establishment in new areas is dependent on its successful seed germination and seedling emergence.

In many regions of China, shortawn foxtail has become a dominant noxious weed in some overwintering crop fields, especially in canola and wheat fields with a rice (Oryza sativa L.) rotation (Guo et al. Reference Guo, Liu, Li, Yuan, Du and Wang2015). Its strong tillering capacity enhances its competitiveness against wheat seedlings, resulting in significant yield reduction (Liu et al. Reference Liu, Wang and Jiang1992; Morishima and Oka Reference Morishima and Oka1980; Zhang Reference Zhang1995). For example, reductions of 24.2% and 51.9% in wheat yield have been reported with shortawn foxtail at densities of 540 to 675 and 1,197 to 1,560 plants m−2, respectively (Zhu and Tu Reference Zhu and Tu1997). Herbicides, the most economic and effective option for control, have been used for many years to manage this problematic weed. Unfortunately, shortawn foxtail has now evolved a high-level resistance to many herbicides with different mechanisms of action, such as fenoxaprop-P-ethyl and mesosulfuron-methyl (Guo et al. Reference Guo, Liu, Li, Yuan, Du and Wang2015; Xia et al. Reference Xia, Pan, Li, Wang, Feng and Dong2015). Complete eradication of shortawn foxtail is unlikely because of its enormous seed production, its capacity to be dispersed by wind and water, and its evolution of herbicide resistance.

The ability of the initial seeds to germinate and emerge under a wide range of environmental conditions is critical to the successful establishment of weed populations (Chauhan et al. Reference Chauhan, Gill and Preston2006d). Seed germination and seedling emergence are usually influenced by various environmental factors such as temperature, light, pH, soil moisture, and soil salinity (Baskin and Baskin Reference Baskin and Baskin1998; Chauhan et al. Reference Chauhan, Gill and Preston2006a). Of these, temperature is a major environmental factor that affects germination by regulating the enzyme activities involved in germination and by influencing the synthesis of hormones that affect seed dormancy (Baskin and Baskin Reference Baskin and Baskin1998). Light appears to function as a dormancy-breaking signal when deeply buried seeds are moved to the soil surface or a shallower soil depth (Kettenring et al. Reference Kettenring, Gardner and Galatowitsch2006). Water is a basic requirement for germination, and lack of water may delay, reduce, or prevent both seed germination and plant growth (Javaid and Tanveer Reference Javaid and Tanveer2014). Similarly, burial depth can also affect the germination, dormancy, and viability of seeds by influencing the availability of temperature, moisture, and light exposure (Benvenuti et al. Reference Benvenuti, Macchia and Miele2001; Chauhan and Johnson Reference Chauhan and Johnson2010). The information on seedling emergence at various burial depths could be helpful in deciding an optimal tillage system to reduce the emergence of weed seedlings.

Currently, ecological information on shortawn foxtail germination and emergence is scarce in the published literature. A detailed knowledge of the ecological requirements for its germination and emergence would facilitate the development of effective control measures. Therefore, the objectives of this study were to determine the effects of temperature, light, pH, osmotic stress, salt stress, and burial depth on germination and emergence of shortawn foxtail.

Materials and Methods

Seed Collection and Preparation

Mature seeds of shortawn foxtail were collected in May 2014 from several neighboring wheat fields at a traditionally managed farm situated in Taizhou, Jiangsu province, China (32.54°N, 120.05°E). Seeds were randomly collected from at least 300 individuals that belonged to the same naturally occurring population. The fields from which seeds were collected had been under repeated wheat–rice rotation for several decades. The collected seeds were air-dried and stored in paper bags at 4C for 5mo to break dormancy (Ebrahimi and Eslami Reference Ebrahimi and Eslami2012; Tang et al. Reference Tang, Xu, Shen and Chen2015). Individual samples were combined after a preliminary test (conducted 5 mo after collection [unpublished data]) revealed that no differences existed among samples with regard to germination. After being combined, the seeds were stored at room temperature (20 ± 5C) until used. The 1,000-seed weight (with bran) was 310 ± 2 mg.

General Seed Germination Test

Experiments were conducted at the College of Plant Protection, Shandong Agricultural University, Tai’an, China (36.15°N, 117.15°E) from May to December 2015. Seed germination of shortawn foxtail was determined by placing 30 seeds evenly in a 9-cm-diameter petri dish containing two layers of filter paper (Whatman No. 1, Maidstone, UK) moistened with 5 ml of distilled water or test solution appropriate for the experiment (i.e., test solutions of different pH levels, osmotic potentials, and salt concentrations). All petri dishes were sealed with parafilm to prevent evaporation and then placed in controlled-environment growth chambers set at a constant temperature of 20C with a 12-h photoperiod, unless specified otherwise. Fluorescent lamps were used to produce a photosynthetic photon flux density of 200 μmol m−2 s−1 for all experiments. Seeds with a visible protrusion of the radicle were considered to have germinated (Chauhan and Johnson Reference Chauhan and Johnson2008a). Germinated seeds were counted and removed daily for 21 d from the start of the experiment until the time of the germination stabilization. Germination values were defined as the total number of germinated seeds divided by the total number of seeds placed in the petri dish.

Effect of Temperature on Seed Germination

To evaluate the effect of temperature on germination, seeds were placed in petri dishes incubated at seven constant temperatures of 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, and 35C, and five fluctuating day/night temperatures of 15/5, 20/10, 25/15, 30/20, and 35/25C. These fluctuating temperature regimes were selected to reflect temperature variation during winter to autumn in the Yangtze River valley of China (Lu et al. Reference Lu, Sang and Ma2006). All other experimental conditions were the same as described in the general seed germination test. To identify whether or not the exposure to high temperature would affect seed viability, the ungerminated seeds from the 35 C temperature regime were placed back into the growth chamber with the temperature set at 20C. The number of germinated seeds was counted after 21 d.

Days required to reach 90% germination value (t 90) under different temperatures were estimated using the following equation (Li et al. Reference Li, Zhang, Wei and Cui2012):

where L is the last day before 90% germination was reached, L p is the observed germination percentage on day L, and H p is the observed germination percentage on the day when germination reached or exceeded 90%.

The germination rate (V) under different temperatures was also estimated using the following equation (Li et al. Reference Li, Zhang, Wei and Cui2012):

Germination values (%) resulting from different constant temperatures and alternating temperature regimes were fit to a functional three-parameter sigmoid model (Chauhan and Johnson Reference Chauhan and Johnson2008a). The fitted model was as follows:

where G is the cumulative germination (%) at time t (d), G max is the maximum germination (%), t 50 is the time required for 50% inhibition of maximum germination, and G rate indicates the slope.

Effect of Light on Seed Germination

To determine the effect of light duration on germination, petri dishes containing shortawn foxtail seeds were exposed to 0/24-, 4/20-, 8/16-, 12/12-, 16/8-, 20/4-, and 24/0-h light/dark regimes per 24-h cycle at 20C constant temperature. In the dark treatment, petri dishes were covered with three layers of aluminum foil to prevent any light penetration. Also, addition of water to the petri dishes and daily germination counts were conducted under green safelight in a darkroom. Exposure to dim green light lasted for less than 30 s. In the treatments with 20/4-, 16/8-, 12/12-, 8/16-, and 4/20-h light/dark regimes, petri dishes were left uncovered for 20, 16, 12, 8, and 4 h, respectively, to allow light exposure. Petri dishes assigned to the 24-h light treatment were uncovered to allow continuous light exposure. Other experimental conditions were the same as described in the general seed germination test.

Effect of pH on Seed Germination

To evaluate the effect of pH on germination, seeds were placed in buffered solutions at pH values of 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, and 10. The buffered solutions were prepared according to the method described by Wu et al. (Reference Wu, Li, Xu and Dong2015). The solutions with pH<7 were used to simulate acidic media, and solutions with pH>7 were used to simulate alkaline media. Unbuffered distilled water (pH 7.6) was used as a control. Other experimental conditions were the same as described in the general seed germination test.

Effect of Osmotic Stress on Seed Germination

To investigate the effect of drought stress on seed germination, shortawn foxtail seeds were tested in aqueous solutions with osmotic potentials of 0,−0.1, −0.2, −0.3, −0.4, −0.5, −0.6, −0.8, and −1.0 MPa, which were prepared by dissolving 0, 72.5, 112.2, 143.2, 169.4, 192.6, 213.6, 251.0, and 284.0 g of polyethylene glycol 8000, respectively, in 1 L of distilled water (Michel and Radcliffe Reference Michel and Radcliffe1995). Other experimental conditions were the same as described in the general seed germination test. The remaining ungerminated seeds at the highest water stress were rinsed with running water for 5 min and returned to the growth chamber after 5 ml of distilled water was added. The number of germinated seeds was counted after 21 d.

Effect of Salt Stress on Seed Germination

To examine the effect of salt stress on germination, seeds of shortawn foxtail were incubated in sodium chloride (NaCl) solutions of 0, 20, 40, 80, 120, 160, 200, 240, and 280 mM. Other experimental conditions were the same as previously stated. To distinguish between the effects of saline ion and NaCl osmotic stress, the ungerminated seeds at highest NaCl concentration were rinsed with running water for 5 min and returned to the growth chamber after 5 ml of distilled water was added. The number of germinated seeds was counted after 21 d. If these seeds germinated after being rinsed with distilled water, then the seed germination was assumed to have been inhibited by NaCl osmotic stress, and not attributable to saline ion effects (Ungar Reference Ungar1991).

Germination values (%) at different NaCl concentrations and osmotic potentials were fit to a functional three-parameter sigmoid model (Chauhan and Johnson Reference Chauhan and Johnson2008a). The fitted model was as follows:

Where G is the total germination (%) at NaCl concentration or osmotic potential x, G max is the maximum germination (%), x 50 is the NaCl concentration or osmotic potential required for 50% inhibition of the maximum germination, and G rate indicates the slope.

Effect of Burial Depth on Seed Germination

The effect of seed burial depth on seedling emergence was studied in controlled-environment growth chambers. The soil (38% clay, 26% silt, and 36% sand, pH 7.1, 1.7% organic matter) used for this experiment was autoclaved and passed through a 3-mm sieve before the experiment was conducted. Thirty seeds were placed on the soil surface (0-cm depth) or covered with soil at depths of 0.2, 0.5, 0.8, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, and 10 cm in 15-cm-diameter plastic pots. Pots were watered every other day to maintain adequate soil moisture. All the pots were placed randomly inside a growth chamber at 20/15C with a 12-h photoperiod. The seedlings were considered to be emerged when the coleoptile was visible above the soil surface. Emergence was counted weekly for 42 d until no further emergence was recorded, and the seedlings were removed after the weekly counts. At the end of the experiment, pots with no plant emergence were checked to identify whether the coleoptile failed to reach the soil surface or the seeds failed to germinate. Simultaneously, the ungerminated seeds buried at deepest depth were spread on the soil surface to determine whether they were dead or simply in an unfavorable environment.

The seedling emergence values (%) obtained at different burial depths were fit to a three-parameter sigmoid model (Mahmood et al. Reference Mahmood, Florentine, Chauhan, McLaren, Palmer and Wright2016). The fitted model was as follows:

where E is the ultimate seedling emergence (%) at burial depth x, E max is the maximum seedling emergence (%), x 50 is the depth to reach 50% of maximum seedling emergence, and e indicates the slope.

Statistical Analysis

All experiments were arranged in a randomized complete block design with four replications. Experiments were repeated over time, and the second run of experiments was started within a month of termination of the first run. Data sets from repeated experiments were subjected to ANOVA with the general linear model procedure using SPSS software (v. 19.0, IBM, Armonk, NY). There was no statistically significant (P > 0.05) trial by treatment interaction for any experiment, and the data were therefore pooled across runs and used for subsequent analyses. Regression analysis was conducted where appropriate using SigmaPlot software (v. 12.5, Systat Software, Point Richmond, CA), and mean comparison was performed using Fisher’s protected LSD test at P ≤ 0.05.

Results and Discussion

Effect of Temperature on Seed Germination

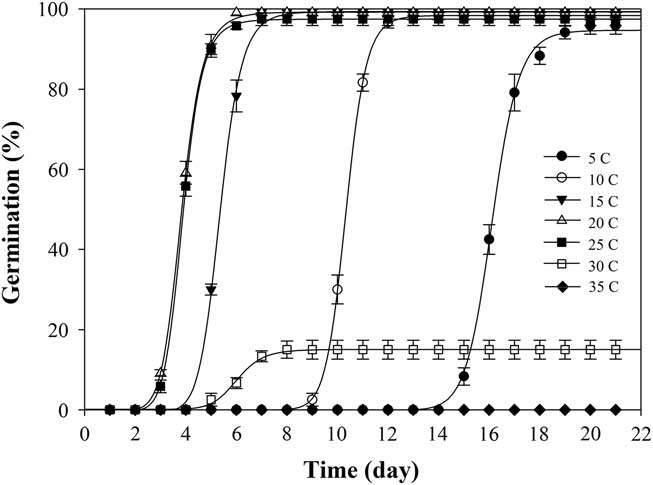

Under constant temperature, shortawn foxtail germinated over a wide range of temperatures between 5 and 30C (Table 1). Germination values were all greater than 95% from 5 to 25C, and no germination was observed at 35C. The highest (100%) seed germination was obtained at 20C, whereas the lowest (15%) was attained at 30C. Increasing the temperature from 5 to 20C did not significantly affect the germination values but gradually reduced the time to onset of germination and the time to achieve 90% germination (t 90) (Figure 1; Table 2). Haferkamp (Reference Haferkamp, Karl and MacNeil1994) reported that a low-temperature environment did not affect total germination value. Shortawn foxtail may germinate within 3 d at 20 or 25C, but 15 d were needed for germination to occur at 5C (Table 1). This result may be attributable to the effective accumulated temperature being reached more quickly at 20 or 25C. Conversely, germination was limited at higher temperatures (e.g., 30C), suggesting that even though the effective accumulated temperature was reached, shortawn foxtail failed to germinate. These results support the finding of Chauhan and Johnson (Reference Chauhan and Johnson2008a) that temperature is an important factor influencing weed seed germination. When ungerminated seeds from the 35C temperature regime were transferred to the 20C temperature regime, mean germination was 95%. This suggests that exposure to the higher temperature for 21 d had not adversely affected seed viability.

Figure 1 Effect of seven constant temperatures (5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, and 35 C) on germination of shortawn foxtail seeds after incubation with a 12-h photoperiod for 21 d. Vertical bars represent standard error of the mean and logistic sigmoidal regression fit to the data.

Table 1 Germination percentages and days required to reach 90% germination (t 90) for shortawn foxtail seeds exposed to seven constant temperatures and five alternating temperatures.Footnote a

a Abbreviations: T, time to onset of germination; t 90, days required to reach 90% germination value; V, germination rate under different temperatures; NA, not available because germination value did not reach 90% in all replications.

b Means followed by the same letter are not significantly different according to Fisher’s protected LSD at P≤0.05.

c Calculated as described in Equation 1: t 90=(H p−L p)−1+L, where L is the last day before 90% germination was reached, L p is the observed germination percentage on day L, and H p is the observed germination percentage on the day when germination reached or exceeded 90%.

d Calculated as described in Equation 2: V=1/t 90.

e The numbers in parentheses represent the mean temperature.

Table 2 Parameters of the functional three-parameter sigmoid modelFootnote a used to fit the germination values (%) resulting from different constant temperatures and alternating temperature regimes.

a G(%)=G max/{1+exp[−(t−t 50)/G rate]}, where G is the cumulative germination (%) at time t (d), G max is the maximum germination (%), t 50 is the time required for 50% inhibition of maximum germination, and G rate indicates the slope.

b ND, not determined because germination did not occur at 35 C.

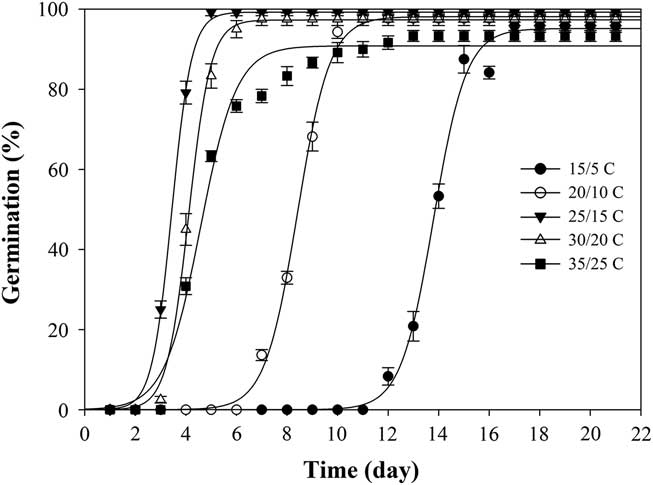

When exposed to fluctuating temperatures, seed germination values were beyond 90% at all the tested temperature regimes (Table 1). As expected, seeds took a longer time to reach 90% germination (t 90) at 15/5C compared with the other four alternating temperature regimes (Figure 2; Table 2). The germination values and germination rates of all the constant temperature treatments were compared with those of all the alternating temperatures. Compared with constant temperature, the same mean alternating temperatures did not significantly improve the germination values, except 35/25C, for which germination was 93% (Table 1). Nevertheless, at the mean temperatures of 10, 15, 20, and 25C, alternating temperatures reduced germination rates compared with constant temperatures. The higher germination rate under the stable temperature regimes could be due to the longer exposure of seeds to suitable temperatures than was the case with fluctuating temperatures. Similar results have been previously reported for field brome (Bromus arvensis L.) (Li et al. Reference Li, Tan, Li, Yuan, Du, Ma and Wang2015). Conversely, germination of Asia minor bluegrass (Polypogon fugax Nees ex Steud.) is favored by fluctuating temperatures (Wu et al. Reference Wu, Li, Xu and Dong2015).

Figure 2 Effect of five alternating temperature regimes (15/5, 20/10, 25/15, 30/20, and 35/25 C) on germination of shortawn foxtail seed after incubation with a 12-h photoperiod for 21 d. Vertical bars represent standard error of the mean and logistic sigmoidal regression fit to the data.

The response of shortawn foxtail to various temperatures in this study was neatly dovetailed with its distribution in China and corresponding seasonal temperatures. Shortawn foxtail widely occurs in the east, south-central, and southwest China, which have a mean temperature range of 5 to 25C from mid-October to late December (Lu et al. Reference Lu, Sang and Ma2006). According to Zheng et al. (Reference Zheng, Yin and Li2010), more than 70% of China’s land area lies within a temperate, subtropical, or tropical zone. The annual average temperature is 8C in the temperate zone, and it is higher in the subtropical and tropical zones. Given that shortawn foxtail can germinate across the wide range of 5 to 30C, it has great potential to spread into most regions of China and thus become a problematic weed in these areas in the future.

Effect of Light on Seed Germination

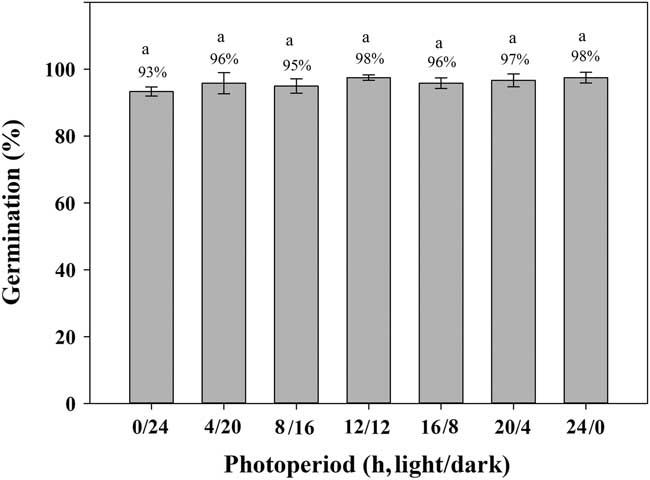

Exposure to light had limited effect (P>0.05) on the germination of shortawn foxtail (Figure 3). Under continuous dark (0/24 h) conditions, germination was 93%, whereas exposure to continuous light (24/0 h) increased germination to 98%. A high percentage of albinotic seedlings was observed under continuous dark conditions (unpublished data). Germination values were all ≥95% with exposure to alternating light and dark conditions. Germination was >90% in either continuous light or dark or in alternating light and dark conditions, suggesting that shortawn foxtail is not sensitive to photoperiod. These results indicate that shortawn foxtail may germinate in soil and under a plant canopy. This non-photoblastic characteristic of shortawn foxtail helps to explain why it has become a serious weed in wheat fields. Seeds can still germinate in late winter when the winter crops, such as wheat, have already covered the whole ground. This important feature may enhance its invasiveness.

Figure 3 Effect of light on germination of shortawn foxtail seeds incubated at 20 C with different photoperiods for 21 d. The vertical bars represent standard error of the mean. Bars with the same letters are not significantly different according to Fisher’s protected LSD at P ≤ 0.05.

Varied responses of germination to light have been reported among different weed species. Similar to our results, Singh et al. (Reference Singh, Ramirez, Sharma and Jhala2012) expressed that tall morningglory [Ipomoea purpurea (L.) Roth] seeds did not require light for germination. Similarly, it has been found that the germination of many other weed species, such as American sloughgrass [Beckmannia syzigachne (Steud.) Fernald] (Rao et al. Reference Rao, Dong, Li and Zhang2008), Japanese brome (Bromus japonicus Thunb. ex Murr.) (Li et al. Reference Li, Tan, Li, Yuan, Du, Ma and Wang2015), bird’s-eye cress (Myagrum perfoliatum L.) (Honarmand et al. Reference Honarmand, Nosratti, Nazari and Heidari2016), tropical signalgrass [Urochloa distachya (L.) T. Q. Nguyen] (Teuton et al. Reference Teuton, Brecke, Unruh, MacDonald, Miller and Ducar2004), and Tausch’s goatgrass (Aegilops tauschii Coss.) (Fang et al. Reference Fang, Zhang, Wei, Huang and Liu2012), are not affected by light. However, Ohadi et al. (Reference Ohadi, Mashhadi and Tavakol-Afshari2011) found that turnipweed [Rapistrum rugosum (L.) All.] seeds are photosensitive.

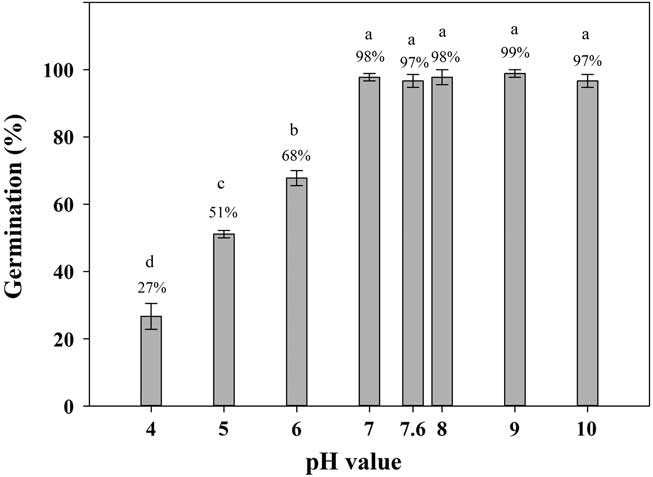

Effect of pH on Seed Germination

Shortawn foxtail seeds had ≥27% germination values over a pH range of 4 to 10 (Figure 4). The highest (99%) and lowest (27%) germination percentages occurred at a pH of 9 and a pH of 4, respectively. Over the pH range of 7 to 10, seed germination was >95%. These results suggest that shortawn foxtail can germinate over a wide range of pH levels. This characteristic is common for many weed species, such as American sloughgrass (Rao et al. Reference Rao, Dong, Li and Zhang2008), Tausch’s goatgrass (Fang et al. Reference Fang, Zhang, Wei, Huang and Liu2012), and Japanese brome (Li et al. Reference Li, Tan, Li, Yuan, Du, Ma and Wang2015). The ability of shortawn foxtail to germinate over a wide range of pH levels indicates that soil pH is not a limiting factor in germination, and it can adapt to a wide range of soil conditions. In China, shortawn foxtail mainly occurs in the Yangtze delta region (Huang Reference Huang2004; Wang and Qiang Reference Wang and Qiang2007), where the soil pH ranges from 4 to 9 (Cheng et al. Reference Cheng, Pan, Cang, Yang and Wang2000; Huang et al. Reference Huang, Jiao, Zong, Zhou, Zheng and Sass2002). More acidic pH conditions greatly reduced germination (Figure 4), which indicates that alkaline soil conditions facilitate shortawn foxtail germination. Such soil pH conditions are common throughout China (Lu et al. Reference Lu, Sang and Ma2006). This may facilitate this weed invading diverse habitats.

Figure 4 Effect of buffered pH on germination of shortawn foxtail seeds incubated at 20 C with a 12-h photoperiod for 21 d. Vertical bars represent standard error of the mean. Bars with the same letters are not significantly different according to Fisher’s protected LSD at P ≤ 0.05.

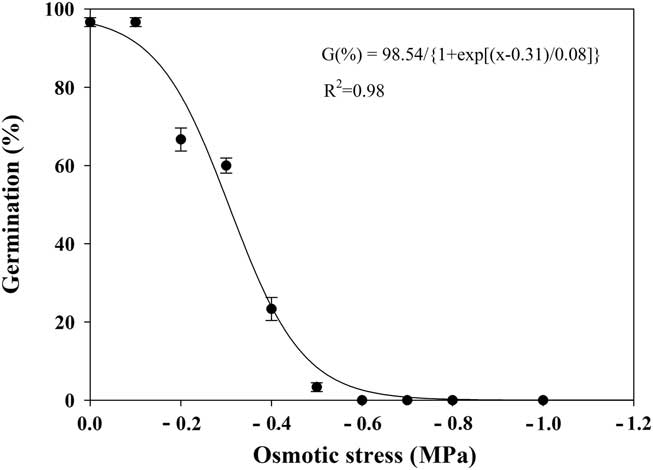

Effect of Osmotic Stress on Seed Germination

The seed germination of shortawn foxtail was greatly affected by the osmotic potential, as shown by a three-parameter sigmoid model (Equation 4; Figure 5). Seed germination decreased from 97% to 3% as osmotic potentials decreased from 0 to −0.5 MPa, and no germination was observed at −0.6 MPa. The osmotic potential necessary for a 50% reduction of maximum germination was estimated at approximately −0.31 MPa. These results suggest that shortawn foxtail seeds were sensitive to high osmotic deficit. Similar results were reported for several other weed species, such as annual sowthistle (Sonchus oleraceus L.) (Chauhan et al. Reference Chauhan, Gill and Preston2006b), American sloughgrass (Rao et al. Reference Rao, Dong, Li and Zhang2008), tall morningglory (Singh et al. Reference Singh, Ramirez, Sharma and Jhala2012), and eclipta [Eclipta prostrata (L.) L.] (Chauhan and Johnson Reference Chauhan and Johnson2008b). Conversely, turnipweed (Chauhan et al. Reference Chauhan, Gill and Preston2006c) and Japanese brome (Li et al. Reference Li, Tan, Li, Yuan, Du, Ma and Wang2015) were more tolerant to extreme water stress.

Figure 5 Effect of osmotic potential on germination of shortawn foxtail seeds incubated at 20 C with a 12-h photoperiod for 21 d. Vertical bars represent standard error of the mean and logistic sigmoidal regression fit to the data.

Owing to shortawn foxtail’s inability to germinate under low osmotic potential conditions, its spread is possibly restricted to moist soils. Our finding is consistent with its hygrophilous nature, distributed in bottomland, riverbed, and wet soil (Huang Reference Huang2004; Wang and Qiang Reference Wang and Qiang2007). In the Yangtze delta region, annual precipitation is more than 1,000 mm, with moist soils in fall that are suitable for the germination of shortawn foxtail. Whereas the humid regions in southern China have much higher temperatures in the fall, the dry regions in the north of China have lower annual precipitation, ranging between 500 and 800 mm, which may inhibit its germination and spread. In summary, benign temperatures and abundant precipitation in the Yangtze River region may explain why this weed mainly occurs in this area.

In our study, when ungerminated seeds were removed from −1.0 MPa osmotic potential and placed in distilled water, mean germination was 94%. This indicates that exposure to lower osmotic potential conditions for 21 d did not adversely affect seed viability and that seeds in dry conditions may wait until moist conditions are available before germinating.

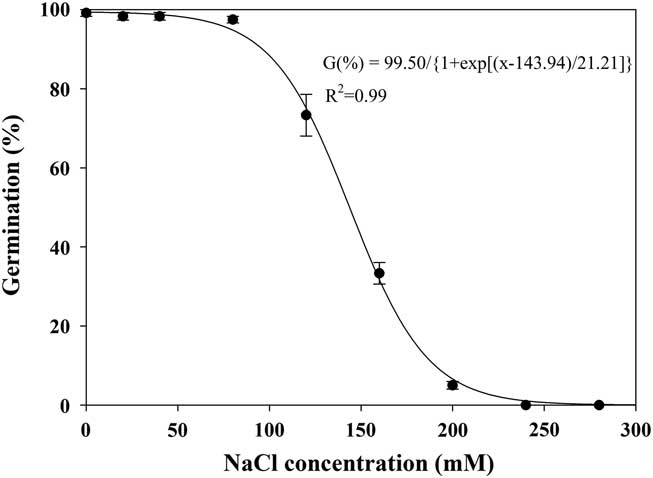

Effect of Salt Stress on Seed Germination

The germination of shortawn foxtail seeds was inversely related to the NaCl concentration, and a three-parameter logistic model (Equation 4; Figure 6) was fit to the final germination values at different NaCl concentrations. Germination values decreased from 99% to 5% as NaCl concentrations increased from 0 to 200 mM, and no germination was observed at 240 mM. The NaCl concentration required for 50% inhibition of germination was estimated at 144 mM. These results suggest that shortawn foxtail was fairly tolerant to salt stress. Because most shortawn foxtail seeds can germinate even at high NaCl concentrations, the plant is highly adaptable to and can spread into saline areas. Similar weed species, including African mustard (Brassica tournefortii Gouan) (Chauhan et al. Reference Chauhan, Gill and Preston2006c), American sloughgrass (Rao et al. Reference Rao, Dong, Li and Zhang2008), and bird’s-eye cress (Myagrum perfoliatum L.) (Honarmand et al. Reference Honarmand, Nosratti, Nazari and Heidari2016), can also germinate at high NaCl concentrations.

Figure 6 Effect of NaCl concentration on germination of shortawn foxtail seeds incubated at 20 C with a 12-h photoperiod for 21 d. Vertical bars represent standard error of the mean and logistic sigmoidal regression fit to the data.

Osmotic stress is caused by solutes in the environment that lower the osmotic potential to a point where seed germination or plant growth is inhibited, while a specific ion effect is due to the chemical toxicity of a given ion and not an osmotic stress caused by that ion (Ungar Reference Ungar1991). Enforced seed dormancy and plant growth inhibition due to osmotic effect can be alleviated after seeds or seedlings are removed from a saline environment. In this study, when nongerminated seeds at 280 mM NaCl were rinsed and placed in distilled water, mean germination was 93%, indicating that the saline solutions had not adversely affected seed viability. This suggests that enforced seed dormancy was due to an osmotic stress as opposed to a specific ion effect. Shortawn foxtail seeds in saline conditions may not germinate until favorable conditions prevail. Additionally, shortawn foxtail seeds were intolerant to osmotic stress but tolerant to salt stress, suggesting that shortawn foxtail germination is more dependent on an irrigation event or precipitation for germination in the field. The effects of water and salt stress on seed germination were examined separately in this study. Combination of these two factors in the field may have more complex effects on seed germination of shortawn foxtail.

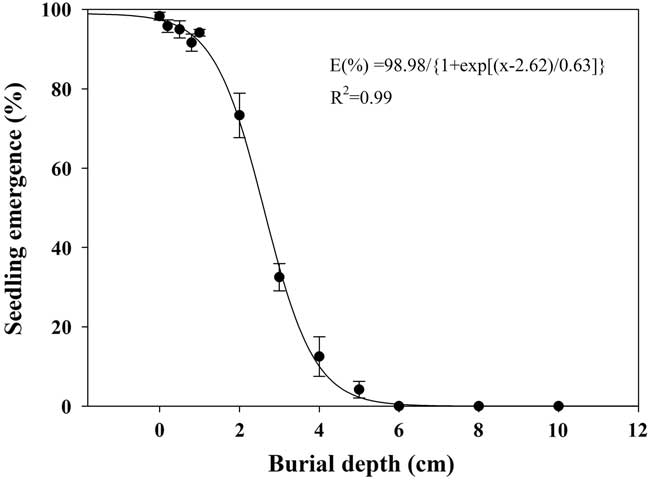

Effect of Burial Depth on Seed Germination

Seedling emergence of shortawn foxtail was inversely affected by increased burial depth, and a three-parameter logistic model (Equation 5; Figure 7) was fit to the seedling emergence data from 0- to 10-cm burial depths. As light is not necessary for seed germination (Figure 3), shortawn foxtail is able to germinate following deep burial. Maximum seedling emergence (98%) was observed for the seeds placed on the soil surface, and emergence decreased as planting depth increased. Seedling emergence slightly decreased as planting depth increased from 1 to 2 cm but decreased sharply when seeds were planted deeper than 2 cm. Minimum seedling emergence (4%) occurred with seeds sown at a depth of 5 cm, and no seedlings emerged from seeds buried at a depth of 6 cm. According to the fitted model, the depth required for 50% inhibition of the maximum seedling emergence was estimated to be 2.62 cm. Similar to our results, decreased seedling emergence due to increased burial depth has been reported in many weed species (Benvenuti et al. Reference Benvenuti, Macchia and Miele2001; Li et al. Reference Li, Tan, Li, Yuan, Du, Ma and Wang2015; Rao et al. Reference Rao, Dong, Li and Zhang2008; Schutte et al. Reference Schutte, Tomasek, Davis, Andersson, Benoit, Cirujeda, Dekker, Forcella, Gonzalez-Andujar, Graziani, Murdoch, Neve, Rasmussen, Sera, Salonen, Tei, Tørresen and Urbano2014).

Figure 7 Effect of seed burial depth on emergence of shortawn foxtail seedlings incubated inside a growth chamber at 20/15C with a 12-h photoperiod for 42 d. Vertical bars represent standard error of the mean and logistic sigmoidal regression fit to the data.

In this study, shortawn foxtail seedling emergence was inversely related to burial depth. Wu et al. (Reference Wu, Li, Xu and Dong2015) also reported that burial depth greatly influenced seedling emergence of Asia minor bluegrass, with seedlings planted more deeply failing to emerge because the small seeds could not provide enough nutrition for the coleoptiles to reach the soil surface. Because of the absence of light, seedling emergence behavior of seeds buried at increasing depths may completely depend on seed reserves (Mennan and Ngouajio Reference Mennan and Ngouajio2006). However, the present study found that the failed emergence of shortawn foxtail was mainly the result of depth-imposed dormancy rather than fatal germination. Moreover, most of the seedlings (94%) emerged when the seeds initially buried at 6 cm were brought to the soil surface. This mechanism of germination inhibition may be an important survival strategy, leading to a perpetual seedbank for shortawn foxtail (Benvenuti et al. Reference Benvenuti, Macchia and Miele2001).

In addition, maximum seedling emergence occurred when seeds were placed on the soil surface, indicating that shortawn foxtail is likely to be favored in no-till and minimum-till farming systems, because these systems leave most of the weed seeds on the soil surface after crop harvest. Because no seedling can emerge from a depth of 6 cm, deep-tillage operations that bury seeds below this depth could be an option to limit the germination of this weed. Subsequent tillage operations would need to be shallow to avoid bringing the buried seeds back to the soil surface.

Overall, results of this study indicate that shortawn foxtail was adapted to germinate under a wide range of environmental conditions commonly found in the Yangtze delta region. This may partially explain its successful infestation of this area. Measures should be taken to control the weed in late fall when temperatures are favorable for germination. Shortawn foxtail is sensitive to water stress, indicating that low osmotic potential is a limiting factor for its further spread in dry conditions. Reducing the osmotic potential at the right time may be an effective measure to prevent germination. Seedling emergence was optimal with seeds sown in the top 2 cm of the soil layer, making this species a problematic weed in no-till and minimum-till farming systems. Deep tillage to bury the seeds below their maximum depth of emergence would be a possible management option for establishing a crop in fields infested with shortawn foxtail.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the Special Fund for Agro-scientific Research in the Public Interest (No. 201303031). We thank editor Bhagirath Singh Chauhan and anonymous reviewers for useful and insightful comments on draft versions of the article. We thank the Charlesworth Group for their professional English language editing services.