The fox knows many things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing.

The philosopher and intellectual historian Isaiah Berlin began his best-known essay by quoting the line above, a fragment of the seventh-century b.c. Greek poet Archilochus. Berlin takes the words figuratively, applying them to divisions between human thinkers. For him, “hedgehogs” are those people “who relate everything to a single central vision, one system, less or more coherent or articulate, in terms of which they understand, think, and feel,” while the “foxes” are “those who pursue many ends, often unrelated and even contradictory, connected, if at all, only in some de facto way, for some psychological or physiological cause, related to no moral or aesthetic principle” (Berlin Reference Berlin2013:2).

As metaphors for scholars, the fox and the hedgehog have become common shorthand not only for the contrast between broad generalists (foxes) and deep specialists (hedgehogs), but also for fundamental, antithetical ways of approaching knowledge. Those who strive to give reality a unifying shape are the hedgehogs, and those who are content to recognize the parts, rather than the whole, are the foxes.

Classicists more interested in Archilochus's poetry than in Berlin's metaphorical use of it have asked: why the pairing of the hedgehog and the fox (Bowra Reference Bowra1940:26–27)? More specifically, why is the hedgehog described as “crafty” in the same way as the fox? Some scholars argue that the word rendered “thing” in the quotation above should be translated specifically as “trick,” and that the fox's many tricks are defeated by the hedgehog's one big trick—rolling itself into a ball to elude the fox (e.g., Davenport Reference Davenport1963:53). In fact, a literal rendering of the fragment specifies neither thing nor trick, saying only: “Fox knows many / But Hedgehog one big one” (Campbell Reference Campbell1982:7[103]). Regardless of whether the comparison is about knowing things or knowing tricks or knowing something else altogether, what is of most interest to us is the fact that the meanings of particular animals, and the appropriate associations between them for Archilochus in the seventh century b.c., continue to prompt reflection among his twentieth- and twenty-first-century readers.

In this article, we examine what might be considered the fox and the hedgehog's New World counterparts: the (gray) fox and the armadillo. Specifically, we attempt to sketch out some Classic Maya categorizations of the animal world, using these two species as focal points. We highlight some characteristics of both animals that seem to have been salient, while mapping out their relations to one another and to other kinds of beings. There are two reasons for our choice of foxes and armadillos. The first is to explore in detail Maya representations of two animals that have been relatively understudied (by contrast to, say, deer [Looper Reference Looper2019], centipedes and snakes [Boot Reference Boot1998; Kettunen and Davis Reference Kettunen and Davis2000; Taube Reference Taube and Ruíz2003a], or sharks [Borhegyi Reference Borhegyi1961; Newman Reference Newman2016]). The second is to ask the kinds of questions about animal and human natures incited by the poetic fragment of Archilochus. How do foxes and armadillos appear in Classic Maya art? What kinds of observation and knowledge about those animals do text and imagery convey? What literal, metaphorical, or moral meanings might such representation express?

Science historian Lloyd (Reference Lloyd2012:2) has written: “We may not be able to understand jaguars as others understand them, but we can begin to understand the significance of what people have believed about jaguars for their ideas both about the world and about how to live.” In examining the fox and the armadillo, as explicitly named or illustrated in Maya art and according to the terms by which they are depicted, our goal is indeed to tease out some of the significance they may have held for people in the past, but it is to further highlight the limits (and limitations) of Western animal categories and biological taxonomies in approaching that kind of understanding (see, e.g., Kitcher Reference Kitcher1984; Rogers Reference Rogers2008; Schiebinger Reference Schiebinger1993).

We are fully aware of the methodological dilemma we face in applying our own ideas and concepts to Classic Maya art and text, but we are convinced that we cannot altogether avoid using the tools we have, even if we may be bound to distort ancient systems of classification in doing so. Our approach draws on locally rooted descriptions of particular animals and their behaviors wherever possible—privileging knowledge gained through specific human–animal encounters over more distant, generalizing, and standardized statements about what animals are and do that are common to zoological guides and textbooks. We additionally draw on evidence found in Mayan languages, historical records, and ethnographic studies. Our use of those sources is not intended to suggest an unbroken line of cultural practices from the past to the present—the claims we make about Classic Maya “animal” classifications are quite different from any later examples we reference—but rather to highlight that there are and have been real, distinct alternatives to Western categories that are often assumed to be universal and self-evident.

THE FOX

The fox depicted in Classic Maya art and identified in Classic Maya texts is probably not the one that comes to mind most readily to scholars from the United States or Europe. In contrast to the large, red fox (Vulpes vulpes) known throughout most of the Northern hemisphere, the gray fox (Urocyon cinereoargenteus), is smaller, with stout legs, a narrow face, and long tail. Diego de Landa, first bishop of Yucatan, found it wanting: “There are foxes,” he wrote in his sixteenth-century Relación de las cosas de Yucatán, “in everything like those here [in Spain] except that they are not so large nor do they have such a good tail” (Tozzer Reference Tozzer1941:204).

The Gray Fox

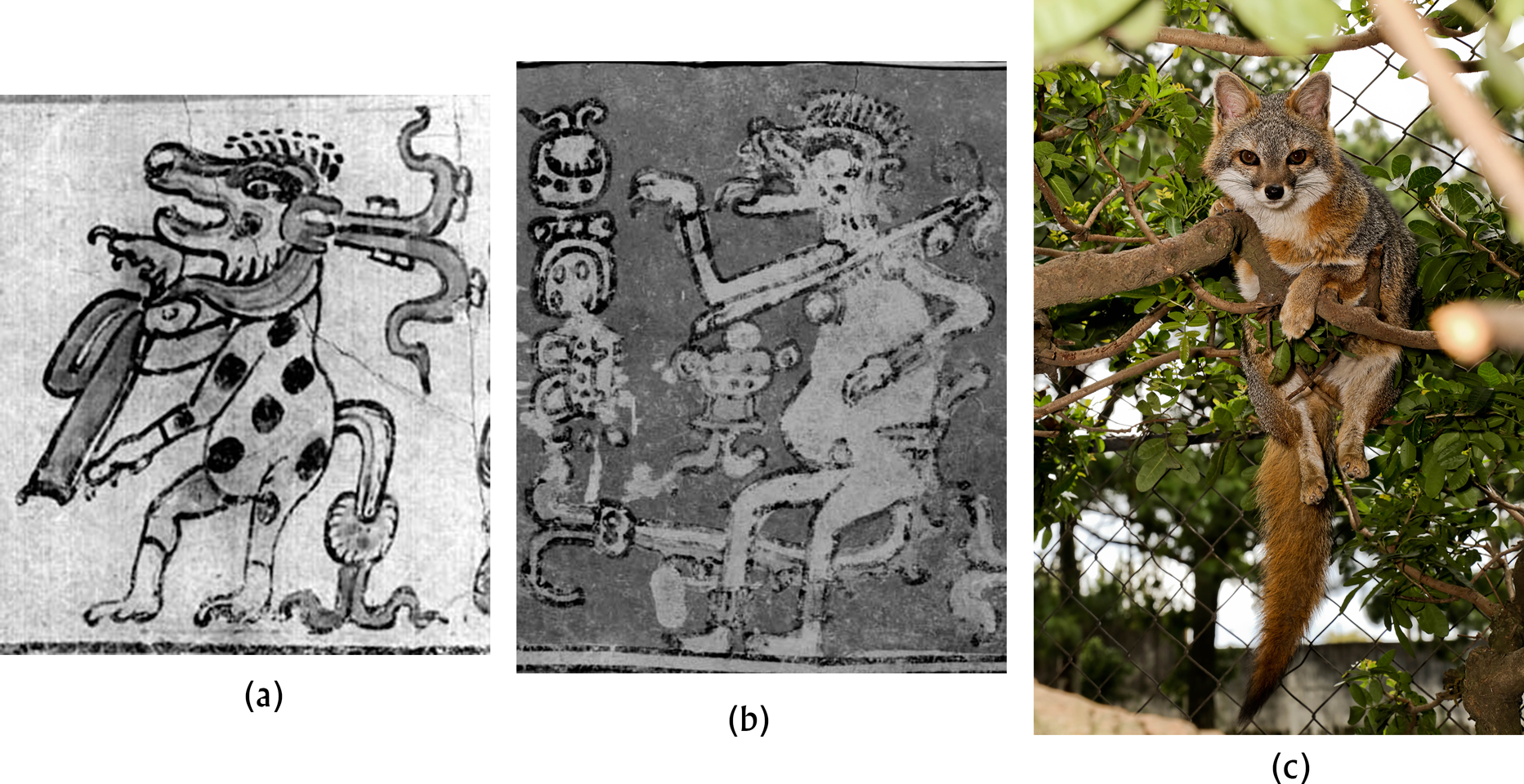

Most zoologists would disagree with Landa's assessment that Urocyon cinereoargenteus is simply a smaller version of Vulpes with a lesser tail. Visually, gray foxes are more muted in color than red foxes: a grizzled gray, with the neck, sides, and legs sometimes highlighted by reddish-brown. Their distinctive white cheeks, muzzle, and throat did not go unnoticed by Classic Maya artists. Gray foxes are marked by a conspicuous black stripe, which forms near the center of the back and extends into a black mane of coarse hair to the end of the tail, with its “coal-black tip” (Starker Leopold Reference Starker Leopold1959:408; see also Fritzell and Haroldson Reference Fritzell and Haroldson1982:1)—another characteristic feature highlighted in ancient imagery (Figure 1).

Figure 1. (a) Gray fox (Urocyon cinereoargenteus). Photograph by Erick Flores, FLAAR Photo Archive of Fauna; (b) Classic Maya representation of a gray fox. Note the white muzzle, throat, and cheeks (with a thin line of darker fur just below the eye, indicated by a series of small black dots on the Maya vase) and the black-tipped tail. Photograph © Justin Kerr, detail from K1901.

Despite their preference for underground dens and burrows, gray foxes are avid and adept tree climbers—a rare ability that, among canids, they share only with the tanuki (also known as the Asian raccoon dog). Gray foxes have sharp, recurved, and semi-retractile claws that allow them to climb even vertical trunks without branches. Those distinctive claws may be highlighted in some Classic-period depictions of foxes on painted pottery (Figures 2a and 2b). They are able to rotate their forearms as much or more than any other canid as an adaptation for climbing (Fritzell and Haroldson Reference Fritzell and Haroldson1982:2). “To escape a pack of hounds,” wrote the naturalist Starker Leopold in his Wildlife of Mexico, “a gray fox often will scramble up a tree and hide in the upper branches … More than once a fox has been observed sunning itself comfortably in the fork of a limb” (Starker Leopold Reference Starker Leopold1959:410; see also Hellmuth Reference Hellmuth2021:11; Figure 2c).

Figure 2. Depictions of gray foxes in Classic Maya art. As in Figure 1, note the characteristic white markings around the face, but also the recurved claws (with one digit shown lifted for emphasis). Photographs by Justin Kerr, details from (a) K3312 and (b) K5084. The recurved claws, along with other adaptations, allow foxes to climb trees—even vertical trunks without branches; (c) a gray fox hanging from tree branches in Guatemala City's La Aurora Zoo. Photograph by Nicholas Hellmuth, FLAAR Photo Archive of Fauna.

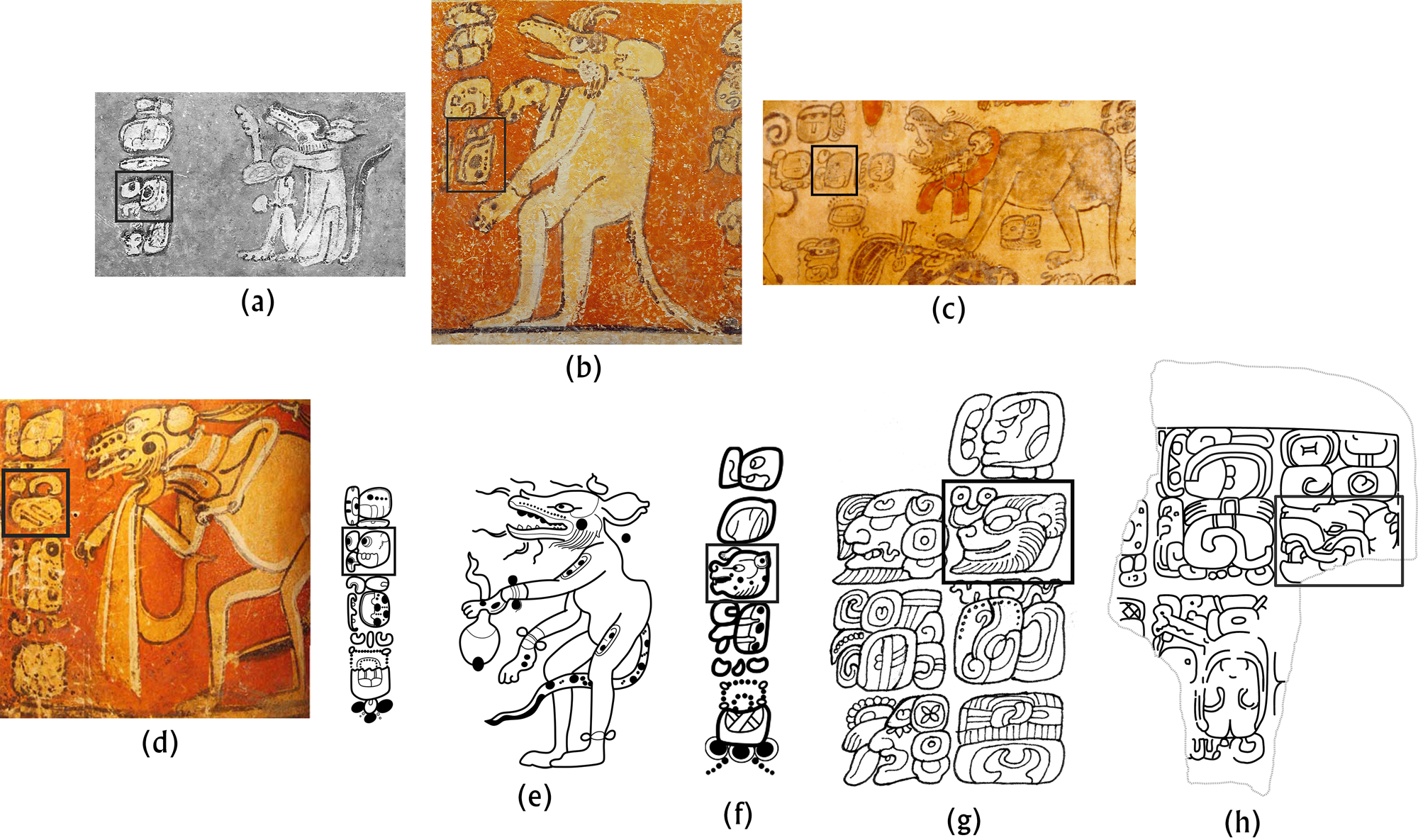

For the Classic Maya, the gray fox was waax—a term most often written using the syllabic spelling wa-xi, sometimes wa-xa (Figures 3a–3e), but also as a rare logograph, WA[A]X (Prager Reference Prager2021; Figure 3f). The word survives in several modern Mayan languages, including Ch'ol (Aulie et al. Reference Aulie, de Aulie and Scharfe de Stairs2009:106), Tzeltal (Hunn Reference Hunn1977:218), Chuj, Q'anjob'al, and Akateko (Kaufman Reference Kaufman2003:568). Another possible term, ch'amak, might be used on a well-known ballcourt marker from Tikal (Figure 3g), which features a glyph that appears to be the head of a fox with the phonetic complement ch'a. Ch'amac is the term given for “fox” in multiple colonial dictionaries of Yukatek, as well as in the colonial histories recounted in the Yukatekan Book of Chilam Balam of Tizimin (Edmonson Reference Edmonson1982:68, 150). Colonial renderings of this term did not use an apostrophe to indicate a glottal stop. Rather, a double h (chhamac) is used to indicate the sound. Our use of ch'amac here follows Edmonson (Reference Edmonson1982); ch'amak reflects current orthographic conventions for the Yukatekan language. In the late sixteenth-century reports to the Spanish Crown known as the Relaciones de Yucatán, “chamac” is also used for fox, explained as animals that “are foxes that destroy the hens, which, as they are close to the bush, they [the foxes] come to the village at night and do harm to the chickens and the eggs” (Asensio Reference Asensio1898:302). The possible CH'AMAK at Tikal is used as the name of a particular individual from Teotihuacan. The ch'a complement, the fox-like face, and the existence of the Yukatekan term have suggested ch'amak as a possible reading, perhaps as a loan word from Yukatek. Another dialectal word for fox, weet, has been proposed for a fox-head logograph (WEET) found on a sandstone slab from Toniná (Houston and Davletshin Reference Houston and Davletshin2021; Figure 3h).

Figure 3. Foxes identified in glyphic text captions using syllabic spellings of waax (“fox”). Photographs by Justin Kerr, details from (a) K1901 (wa-xi), (b) K1379 (wa-xi), (c) K927 (wa-xi), and (d) K90898 (wa-xa); (e) vessel in private collection (wa-xi). Drawing by Christian Prager; (f) a rare logograph, WA[A]X (“fox”), from an unprovenanced vessel in a private collection. Drawing by Christian Prager; (g) a portion of the text on from the Marcador (“ballcourt marker”) monument from Tikal, with the combination ch'a-CH'AMAK, read as “CH'AMAK” for “fox.” Drawing by Linda Schele, © David Schele; (h) fragments of a sandstone slab from Toniná, with the logograph WEET (“fox”). Drawing by Newman after Houston and Davletshin Reference Houston and Davletshin2021:Figure 2.

Skins and Spirits: Human–Fox Relationships

Foxes were hunted by the ancient Maya, although probably not as favored game. Borrowing methods developed in forensic science, a study from northern Guatemala analyzed protein (blood) residues recovered from arrow points and found that small obsidian projectiles were likely used to hunt gray foxes (along with other fauna) during the Postclassic and Contact periods (Meissner and Rice Reference Meissner and Rice2015:72). Contemporary Tzeltal Maya hunters in Tenejapa use slingshots, shotguns, traps, and dogs to opportunistically catch a variety of small and medium-sized game, primarily rabbits, raccoons, pacas, and opossums, but also gray foxes, weasels, pocket gophers, and large ground-dwelling birds (Hunn Reference Hunn1977:13). Deadfall traps, constructed with logs, are sometimes used to kill medium-sized mammals, including foxes (Hunn Reference Hunn1977:110). Starker Leopold (Reference Starker Leopold1959:410) describes Mexico's gray foxes as “surprisingly gentle and confiding, showing no fear of man even in broad daylight” when they have not been pursued or shot at. When they are regularly hunted or chased by dogs, however, “they become as wary and secretive as the proverbial foxes of nursery tales.”

The Relaciones de Yucatán lists foxes alongside ferrets and skunks as animals that are not eaten (Asensio Reference Asensio1898:302; see also Feldman Reference Feldman1971:Tables 8 and 16), but foxes are hunted and consumed by many contemporary Maya hunters. According to Laughlin (Reference Laughlin1975:117, 121, 126, 160, 168, 368), in Zinacantán, Chiapas, foxes (vet in the local Tzotzil language) are eaten seasoned with coriander and their flesh is considered “cold” (see Classen Reference Classen1993:122–126; Maffi Reference Maffi, Gragson and Blount1999; Messer Reference Messer1987), like that of many other comestible species (e.g., white-tailed and brocket deer, peccary, armadillo, squirrel). In nearby Tenejapa, however, Hunn's informants ate fox (known as waš in Tzeltal, but also as wet, a rare loanword from Tzotzil), but considered the meat to be “hot,” like that of the opossum, rabbit, squirrel, coati, raccoon, and jaguarundi (Hunn Reference Hunn1977:203, 205, 219, 222). Geographer Wilson (Reference Wilson1972:404) reported that, for his K'ekchi' informants, “eating yakl [fox] meat is said to incite an appetite for meat of all sorts.” The remains of gray foxes are found only rarely in faunal assemblages from archaeological sites throughout Mesoamerica, usually constituting less than 1 percent of the total number of specimens recovered (e.g., Emery and Brown Reference Emery, Brown, Chacon and Mendoza2012:Table 6.3; Götz Reference Götz2008:Table 1; Paris et al. Reference Paris, Bravo, Pacheco and George2020:Table 1; Sharpe and Emery Reference Sharpe and Emery2015:Table A1; Thornton and Demarest Reference Thornton and Demarest2019:Table 4; but cf. Sharpe et al. Reference Sharpe, Saturno, Emery, Arbuckle and McCarty2014:Table 4.1). As zooarchaeologist Montero López and her colleagues (Montero López et al. Reference Montero López, García, Varela Scherrer and Stuardo2016:12) note, the “minuscule” proportions of gray fox remains in archaeological assemblages are more likely to reflect their uses in ritual or their inclusion in activities other than subsistence.

Beyond their meat, gray foxes have long been hunted for their furs, despite their muted coloring and the warmth of most climates where they can be found. In Guatemala during the fifteenth to eighteenth centuries a.d., foxes were part of an extensive pre-Columbian trade network in furs and hides (Feldman Reference Feldman1971:176, Table 16). In contemporary Tenejapa, Hunn (Reference Hunn1977:218) describes fox skins being used as “toys” during Carnival celebrations, while Laughlin (Reference Laughlin1975:368) reports that, in Zinacantán, a fox skin is stuffed and used on the fiesta of St. Sebastian to represent the president of Mexico. A small assemblage of teeth recovered from Group 2, Building B, Room 2 at the site of Holmul, Guatemala, first classified as shark teeth and later re-analyzed and identified as those of a gray fox, could be the remains of an ancient mortuary assemblage involving a fox pelt, as teeth and claws are the only bones that might be preserved from animal skins (Borhegyi Reference Borhegyi1961:276).

There is evidence for other forms of interactions between humans and gray foxes. In Tenejapa, Hunn reported that some of his informants recognized two varieties of fox—gray and red—the red being an animal spirit, or lab (Hunn Reference Hunn1977:218). Based on conversations with a Tzeltal-speaking shaman and villagers from the town of Cancuc, in Chiapas, ethnographer Pitarch describes the lab as a particular type of soul: one that can be a “real” creature that lives in the outer world, but also a kind of mirror-image vapor inside the human heart. Although virtually any animal can be the lab of a person, certain kinds of animals are known to intervene in events that affect people, whether in dream or during wakefulness. The fox (tsajal wax) is among these (Pitarch Reference Pitarch2010:40). In Laughlin's (Reference Laughlin1975:123) dictionary of the Tzotzil language, the word čon is used in ritual speech by a shaman referring to a companion animal spirit, when that companion animal—of which possibilities listed include jaguarundi, jaguar, mountain lion, raccoon, coyote, skunk, or gray fox—has been wounded. Holland (Reference Holland1963:103), in a study of traditional medicine in highland Chiapas, states that the Tzotzil think of foxes as weaker, less desirable companion animals than felines (jaguar, ocelot, or puma) or coyotes. One of Laughlin's (Reference Laughlin1975:368) informants in Zinacantán reported that “[f]oxes are said to be the companion animal spirits of stupid people, especially Chamulas,” a statement confirmed in part by a Chamula Tzotzil shaman, who explained the hierarchy of animal souls to anthropologist Gossen (Reference Gossen1975:456) by stating, “the opossum, the weasel, and the fox are on the first level. They are weakest. The first level is for the souls of people who don't know how to cure.”

Foxes are rare in contemporary and historical Maya mythology. Thompson's (Reference Thompson1970:249) catalog of myths includes only one example, in which the fox plays a central role in the discovery of maize (see also Burkitt Reference Burkitt1920:211–227). In that story, which, according to Thompson, circulated among Mopan speakers of San Antonio, Belize, as well as among K'ekchi' and Pokomchi speakers, maize kernels were hidden beneath a great rock, known only to leaf-cutting ants who could pass through a small crack in the boulder. One day, the fox found some maize kernels that had been dropped by the ants on their way back to their nest. The fox ate them, found them delicious, and followed the ants back to the rock, eating all the grains they dropped. When the fox returned among the other animals, he broke wind, and the other animals wanted to know what he had eaten that it smelled so sweet. The fox tried to hide his discovery, but he was eventually followed secretly by the other animals. The animals asked the ants to fetch them more grains from beneath the rock, which they did at first, but the animals quickly became too greedy for the ants to keep them all supplied with maize. When the ants refused to bring out any more kernels, the animals eventually had to give man the secret of the wonderful food. Man asked for help from the thunder gods. With the help of the woodpecker, who tapped the rock to find its weakest point, the oldest and greatest of the thunder gods split the rock with his thunderbolt. Although all the maize originally had been white, the thunderbolt burnt some grains, turning them red, smoked others, turning them yellow, and charred some, turning them black.

Despite their limited appearances in myth, gray foxes (and their distinctive barks) are widely considered to be omens. In Chiapas, the fox announces the rainy or foggy season for both Tzotzil speakers in the city of Venustiano Carranza and Tojolabal speakers in the municipality of Las Margaritas (Serrano González et al. Reference Serrano González, Martínez and Velázquez2016:33). According to Laughlin's (Reference Laughlin1975:368) dictionary of Tzotzil, a gray fox's bark “is believed to announce disputes, sickness, broken bones, or murder on the road.” For Wilson's (Reference Wilson1972:72) K'ekchi' informants in Alta Verapaz, Guatemala, a fox seen by day near one's house is likewise an omen of death or disease.

Ancient depictions of foxes on painted pottery highlight their roles as animal spirits or companions, as wahy (the Classic-period analog to contemporary Tzeltal's lab). Wahy are malevolent beings, manifestations of animate, dark forces capable of causing disease and misfortune (Grube and Nahm Reference Grube, Nahm, Kerr and Kerr1994; Just Reference Just2012:126–132). They are sometimes understood to leave the body while it sleeps, often to perform sinister tasks. Humans and their wahy share consciousness: nighttime dreams are said to be the waking experience of one's co-essence (Houston and Stuart Reference Houston and Stuart1989:2). Epigrapher Stuart describes them as “the demonic manifestation of sorcery—the spells and enchantments themselves” (Stuart Reference Stuart2005). The general idea of wahy is rendered in hieroglyphs as a stylized human face half-covered by a jaguar pelt (Houston and Stuart Reference Houston and Stuart1989).

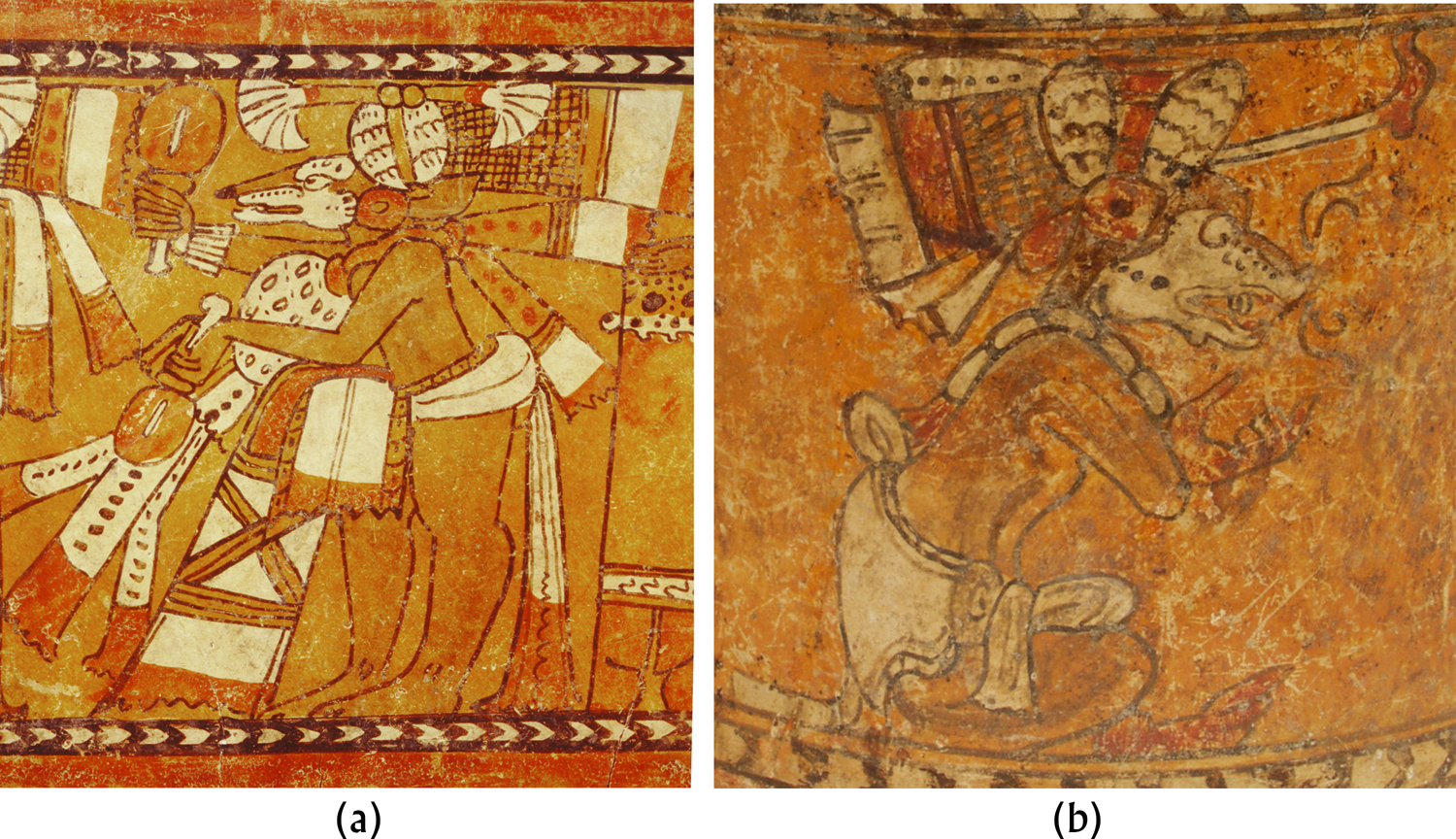

Wahy usually can be distinguished from non-wahy creatures by their visual characteristics. They are frequently depicted as composite beings (often the body of one animal—tapir, peccary, monkey, for example—combined with the paws, ear, and/or tail of a jaguar) or shown breathing fire or wearing collars or necklaces of eyeballs. Specific wahy are also named in hieroglyphic texts, such as the fire-mouthed bat (k'ahk' ti' suutz') or the fire-tailed coati (k'ahk' neh tz'utz'ih). A vase from a private collection depicts a composite being with the head and body of a fox, but the paws and the tail of a jaguar. The creature is labeled syllabically as a waax (“fox”) in the accompanying text, but also given a specific name: Chak Tahn Waax or “Red Chest[ed] Fox” (see Houston and Scherer Reference Houston and Scherer2020)—perhaps an early echo of Hunn's informants’ distinction between the red fox as a lab and the gray fox as an ordinary animal? Its limbs are marked with the AK'AB sign for darkness or night, it stands upright, and holds a hanging, disarticulated eyeball (see Figure 3e). Chak Tahn Waax is identified on other vessels (e.g., Figure 3c), as is another named wahy, K'ahk' Hiix Tahn Waax, the “Fiery Cat Chest[ed] Fox,” which, as its name suggests, appears with jaguar spots on its body and fiery whiskers and tail (Grube and Nahm Reference Grube, Nahm, Kerr and Kerr1994:700; see Figure 2a).

Foxes are relatively rare in Classic Maya texts and imagery, archaeological faunal assemblages, and historically and ethnographically attested myths. Yet those occasional appearances reveal physical attributes of foxes that were noted and depicted by ancient artists, as well as aspects of the relationships among humans, foxes, and more-than-fox wahy.

THE ARMADILLO

The armadillo figures prominently in early European accounts of the Americas. Novel and strange, many attempted to describe it through associations with more familiar animals. In his Relación, Bishop Landa, for example, explained the “little armored one” (the literal translation of the Spanish “armadillo”), called wech by local Yukatekan speakers, through a series of comparisons:

There is another little animal like a very small pig lately born, especially in its forefeet and snout, and it is a great rooter. This animal is all covered with pretty shells so that it looks very like a horse covered with armor, with only its ears and fore and hind feet showing and with its neck and forehead covered with the shells. It is very tender and good to eat (Tozzer Reference Tozzer1941:204).

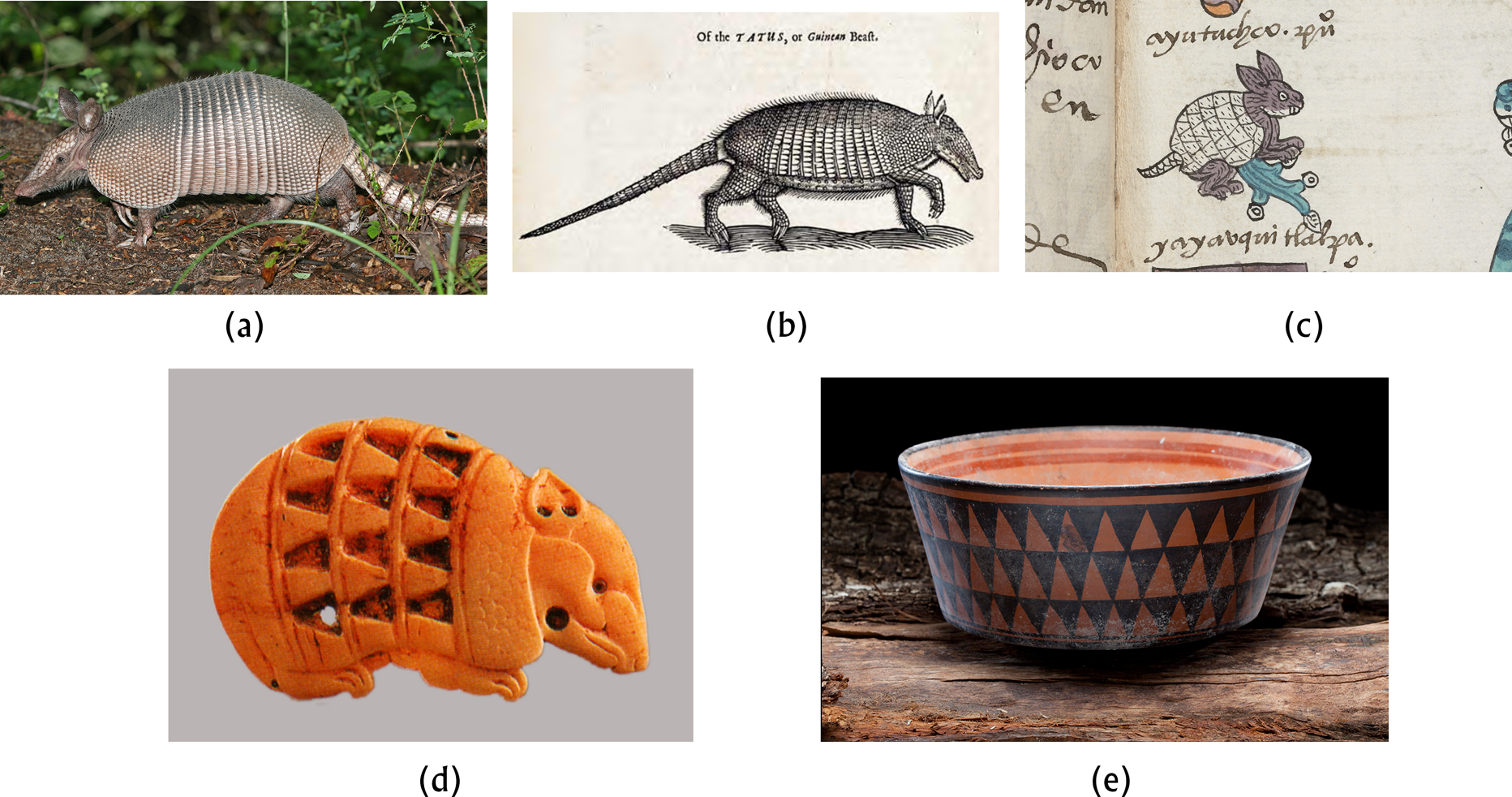

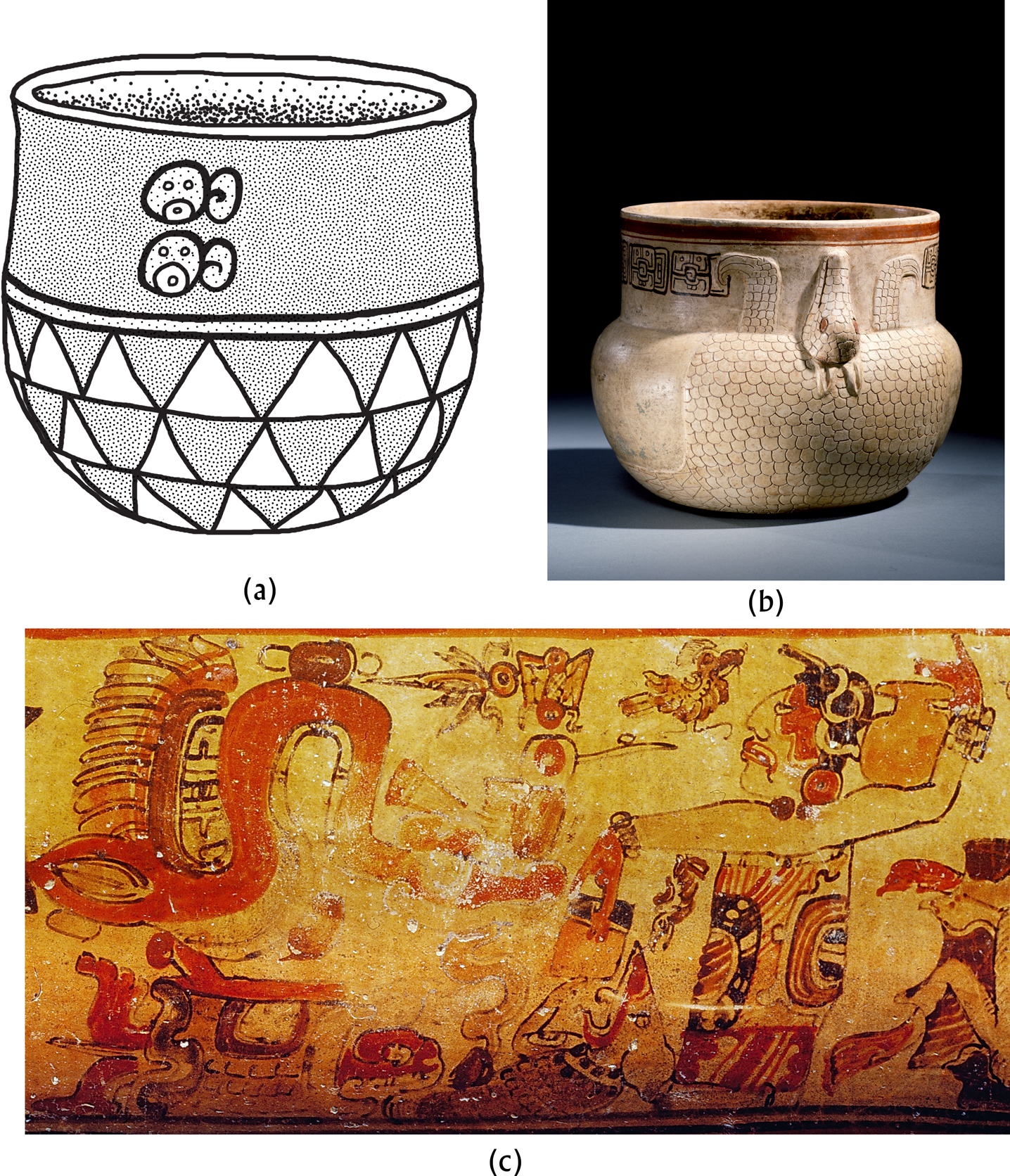

Most likely describing the local nine-banded armadillo (Dasypus novemcinctus; Figure 4a), Landa's characterization of the creature as a blend of pig and armored horse reflects not only how the armadillo historically troubled European categories of classification, but also Landa's world in the midst of violent colonizations and the infamous “Columbian Exchange” (Crosby Reference Crosby1972), well under way by the mid-sixteenth century. His likening of the armadillo to a pig may be a morphological comparison or it may be a reference to the taste of the armadillo's “tender” meat. Even centuries later, however, Kipling's Just So Stories also explained the armadillo by conflating two animals—a hedgehog and a tortoise (Kipling Reference Kipling2010 [1912]:114). Kipling clearly saw a behavioral similarity between hedgehogs, native throughout his European homeland, but not to the Americas, and armadillos (an association also made by earlier naturalists; see Figure 4b). Specifically, he pointed to the tendency of some armadillos to defensively curl into a ball (though nine-banded armadillos do not exhibit that behavior; Talmage and Buchanan Reference Talmage and Buchanan1954:6). Kipling's comparison of the armadillo with the tortoise is based on swimming ability: armadillos swim, or at least float, by inflating their stomachs and intestines with air. They are able to hold their breath for up to six minutes and will occasionally walk across river bottoms, clinging to the ground with their claws (National Wildlife Federation 2020).

Figure 4. (a) Nine-banded armadillo (Dasypus novemcinctus). Photograph by www.birdphotos.com, licensed under CC BY 3.0; (b) woodcut illustration of armadillo, published in 1658, with the accompanying description: “I take it to be a Brafilian Hedge-hog. It is not much greater then [than] a little Pig” (Topsel Reference Topsel1658:546 [a copy of Gesner Reference Gesner1551–1587:20]). Image courtesy of Special Collections, University of Houston Libraries, licensed under CC 1.0; (c) an armadillo used as part of the glyph for Ayotochco from the Codex Mendoza (f. 51r). Photograph © Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford; (d) Classic Maya representation of an armadillo, Offering 10, Yaxha, Guatemala. Note the bands of repeating triangles on the shell, the claw-like feet, leafish ear, and downturned nose. Image after Castillo Reference Castillo1999:30; (e) Ceramic vessel with schematic armadillo hide represented as a set of banded triangles. Vessel 16 (Early Classic Maya, Tzakol 3), Burial 10, Xultun, Guatemala. Photograph courtesy of Proyecto Regional Arqueológico San Bartolo-Xultun.

The difficulty of fitting armadillos into extant taxonomies was not restricted to European invaders, however. Even within the animal's native habitat range, it straddled categorical boundaries. For example, in Central Mexico, the Nahuatl term for the animal was ayotochtli/ayotochin, literally “turtle or tortoise-rabbit,” from ayotl for “turtle” and tochtli or tochin for “rabbit” (Figure 4c), a dualizing name that would eventually shape its currently accepted scientific designation, Dasypus novemcinctus.

Europeans initially adopted the word tatú to describe the armadillo (Figure 4b), which comes from a Tupi-Guaraní word for the animal (most species of armadillo are found in South America). Seler (Reference Seler, Comparato, Thompson and Richardson1996 [1909]:206) still used Tatu novemcinctum, “nine-banded Tatu,” to refer to the nine-banded armadillo (the most prevalent species in Central America) in the early twentieth century. The term Dasypus, however, was first used in reference to the American nine-banded armadillo in the late sixteenth century by Hernández de Toledo, court physician to the Spanish crown, in his Natural History of New Spain (Hernández de Toledo Reference Hernández De Toledo1651). Dasypus is a loan word to Latin from an ancient Greek term literally meaning “hairy-foot” (δασύπους), used (infrequently in Greek) to refer to a “hare” or a particular type of hare (Ayac 2014), and by Pliny, in his Natural History, to refer to a creature thought by many to be a type of rabbit (e.g., Riley Reference Riley1855:bk. 8, ch. 81). Hernández, who spent most of the 1570s on a scientific expedition to the Americas, returned to Spain in 1577 to produce his own Natural History (of the Americas) and a Spanish translation and commentary of Pliny's Natural History (Chabrán et al. Reference Chabrán, Chamberlin and Varey2000).

Hernández's two intellectual endeavors intersected in the case of the armadillo. Hernández apparently drew from a Spanish translation of the original Nahuatl description of ayotochtli (“turtle/tortoise rabbit”) in the Florentine Codex (Book 11), in which the translator seems to have confused the Nahuatl term ayotl, “turtle,” with ayohtli, “gourd.” The Nahuatl description of the animal reads:

Ayotochtli: It lives in the forest; it is a forest dweller. Thus [its name] means “turtle rabbit.” It is called “ayotochin” because [its head] is just like a rabbit's head: it has pointed, flat ears and a stubby muzzle. And its legs are just like a rabbit. It has a shell; its shell is like a turtle's shell (see Ayac 2014).

The Spanish column of text translates as: “There is a creature in this land that is called ayotochtli, which means ‘gourd-like rabbit.’ It is entirely armored with shells; it is the size of a rabbit. The shells with which it is armored resemble pieces of shells of gourds, very hard and strong” (see Ayac 2014). Clearly already familiar with Pliny's obscure term, Dasypus, by the time he was writing his Natural History of New Spain, Hernández used Dasypus cucurbitinus, “gourd-like rabbit,” to describe the armadillo—a combination drawn from the influences of both Sahagún's (Reference Sahagún1950–1982) Florentine Codex and Pliny's Natural History.

The most distinguishing element of the armadillo is its shell or “armor.” A patch of epidermal armor scales extends down the top of the head and covers the tail as scutes. The armor's central bands (of which there actually may be anywhere from seven to eleven, despite the “nine-banded” name) occur at the midsection of the armadillo's shell, constituting a flexible component connecting its scapular and pelvic shields (National Wildlife Federation 2020). Up close, these bands call to mind a pattern of alternating triangles, which is the defining feature of most representations of armadillos in Maya art (Figure 4d). At times, that pattern was abstracted on certain Classic Maya pottery to serve as a decorative motif unto itself, a way of “quoting” armadillo hide in a ceramic medium (Houston Reference Houston2014:42–43; Figure 4e).

Although often miscategorized as toothless because of their lack of incisors and canines, nine-banded armadillos have around 30 undifferentiated cheek teeth. They typically give birth during the Mesoamerican dry season (February to April) and are among the only known animals to give birth to same-sex quadruplets from the same embryo. Armadillos are renowned burrowers, using their legs and foreclaws to rapidly dig into the earth (Schaefer and Hostetler Reference Schaefer and Hostetler2017).

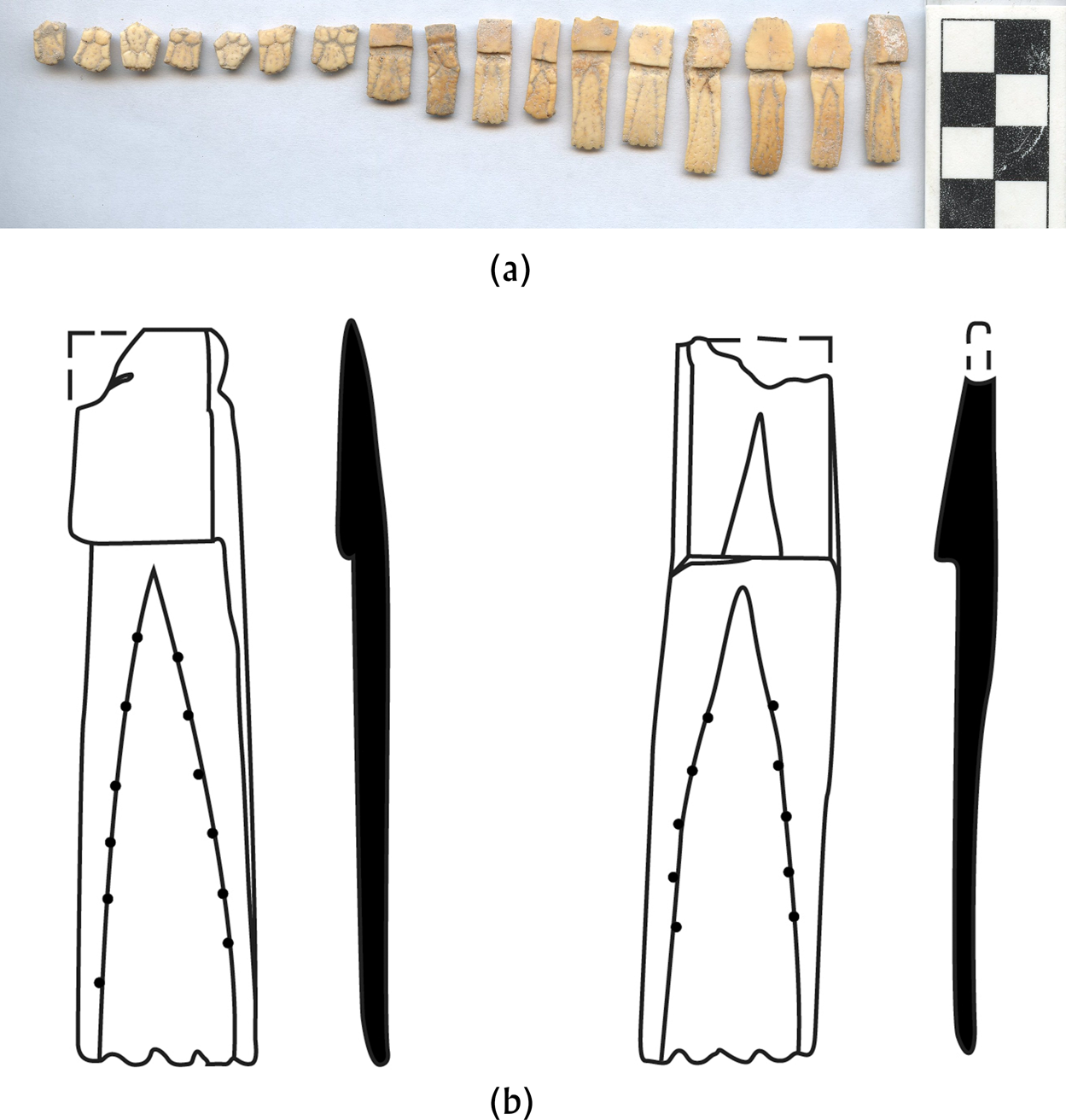

Many an archaeologist working in the Maya area may have heard colleagues refer to looters as huecheros (though see Matsuda Reference Matsuda1998, for a discussion of that designation's complicated connotations) and scattered looters’ tunnels in architecture as hueche—terms that derive directly from the Yukatekan Mayan wech, for armadillo. The looters’ tunnels—excavated quickly, messily, and often at night—are likened to enlarged versions of armadillo burrows. In fact, armadillos sometimes re-use the tunnels abandoned by huecheros, and armadillo scutes are a common find within collapsed tunnels. Their scutes often can be mistaken for artifacts due to their thin, regular shapes and the appearance of being punctured with small holes (Figure 5). Even famed archaeologist Kidder mistook 230 armadillo scutes found in a burial at the site of Uaxactun, Guatemala, as “bone ornaments,” carefully reproducing an example with its profile and speculating as to their unknown function:

… apparently of bird bone … closely alike, exactly 2.3 cm long, with four notches at the thinner end, an incised V in which were tiny drilled punctuations, the thicker end plain or with a smaller V. As they have no suspension holes, they could not have been strung as a necklace; and their curving backs and thin ends render them unsuitable for inlays. Nothing similar has been recorded (Kidder Reference Kidder1947:57, Figure 46; see Figure 5b).

Figure 5. (a) Armadillo scutes found in archaeological contexts at Xultun, Guatemala. Photograph by Franco D. Rossi; (b) misidentification of armadillo scutes found in archaeological excavations in Kaminaljuyu, Guatemala (labeled as “Bone Ornaments. Twice natural size.” in original publication). Drawing by Newman after Kidder Reference Kidder1947:Figure 46.

Squash Meat and Stools: Human–Armadillo Relationships

Bishop Landa made it a point to note the pleasant taste and consistency of armadillo meat in his sixteenth-century account, an opinion that seems to have been long shared by the people he described in his Relación who frequently hunted armadillos. In one of the few naturalistic Classic period Maya representations of an armadillo, a polychrome vessel depicts a hunting party, seemingly returning from a successful outing (Figure 6a). One of the hunters holds atlatl darts in one hand and an armadillo in the other, grasping the little creature by its tail. The Postclassic period Madrid Codex contains scenes in which armadillos are caught in deadfall traps—one of which features a hunting deity approaching the trapped animal (Figures 6b and 6c).

Figure 6. (a) A hunter covered in black body paint carries his armadillo prey by the tail. Photograph by Justin Kerr, detail from K1373. (b) A black-painted figure with a spear approaches an armadillo in a deadfall trap. The top row of the text includes a logograph (whose phonetic value is unknown) for the animal atop a KIN-ni, “day” or “sun” glyph. Photograph by Joaquín Otero, Museo de América, Madrid, detail from the Madrid Codex, f. 91a. (c) An armadillo caught in a deadfall trap. The first glyph in the horizontal row atop the image again includes a logograph (phonetic value unknown) for the animal. Photograph by Joaquín Otero, Museo de América, Madrid, detail from the Madrid Codex, f. 48a.

Archaeological remains further attest to the fact that armadillos were caught and consumed. Even accounting for the inflationary effect of armadillo scutes on archaeological measures (a single armadillo's shell consists of hundreds of the bony scutes overlaid with scales), armadillo remains are found at nearly all ancient Maya sites. Zooarchaeologist Kitty Emery, for example, includes armadillos among the “dominant vertebrates” from sites in the Petexbatún region, alongside turtles, deer, domestic dogs, and other commonly consumed species (Emery Reference Emery2003). Armadillos are a favored prey among opportunistic garden hunters throughout the Americas (Linares Reference Linares1976:338). The term for armadillo meat in Tzeltal Maya is mayil ti'bal or “squash meat.” For Tzotzil speakers, armadillos are sometimes called mayil chon or “squash animal.” Laughlin (Reference Laughlin1975:168, 225) explains that the term is invoked during the hunt to ensure good-tasting meat, which is often eaten “seasoned with Mexican tea.”

The significance of armadillo meat extends beyond its taste and caloric value. Like fox meat, Tzotzil Maya speakers in Zinacantan say that armadillo meat is “cold,” which Laughlin (Reference Laughlin1975:309) reports as signifying that it should not be eaten by women in the initial months after giving birth. Armadillo tails are used by Tzotzil people in healing: to cause an embedded thorn to fall out, one should burn the tail of an armadillo, grind it into powder, and apply it to the wound (Laughlin Reference Laughlin1975:168). Among some Tzeltal Maya communities, where armadillo meat is likewise categorized as cold, it is considered an effective treatment against dysentery (Hunn Reference Hunn1997:233). For Mixe speakers in Oaxaca, armadillo meat is understood as dangerous because it is believed that the animal eats venomous snakes, which, in turn, poison the meat. Before eating an armadillo, they cut open its stomach to check for recently consumed snakes (Miller Reference Miller1956:208).

Armadillos are as important symbolically as they are for subsistence. Linguistic anthropologist Stross traced metaphorical understandings of the armadillo as a stool or footstool in languages and artifacts across and even beyond the limits of Mesoamerica (Stross Reference Stross2007). The Tzotzil Maya word for armadillo is tz'omol chon, or “stool animal” (Laughlin Reference Laughlin1975:100), referencing a mythological role that the animal plays as the sitting stool or footstool for the Earth Lord (see also Gossen Reference Gossen1974:339). In Yucatán, dreaming of a k'anche, a type of low stool, portends that one will see an armadillo (Bruce Reference Bruce1979:177). In fact, wech, the same Mayan term for armadillo that is often applied to illicit excavators, survives in regional Spanish terms for “bench, stool, or taboret” across parts of Tabasco, Chiapas, and Yucatán (Stross Reference Stross2007:3). Versions of the Earth Lord, an underworld deity, and his subterranean home—where armadillo burrows lead—exist across indigenous Mesoamerican traditions, and armadillos routinely serve as that deity's seat or stool (e.g., Bruce Reference Bruce1979:319; Munch Reference Munch1983; Stross Reference Stross2007; Vásquez Dávila and Hipólito Hernández Reference Vásquez Dávila and Hernández1994:158–159; Figure 7).

Figure 7. A metonymic stone footstool carved into the shape of an armadillo. National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution (7274). Photograph by NMAI Photo Services.

In an example from a Lacandón Maya narrative, the armadillo's role as a stool is connected to one of the creature's lesser-known but notable behaviors. To startle or injure predators, armadillos can leap upward forcefully, sometimes as high as four or five feet into the air. One version of the Lacandón story tells of the armadillo's origin in a practical joke played on two fire lords by the chief deity, Hachakyum: The fire lords, one a sacrificer for the rain god and the other a god of war, were invited to a ceremony and seated on two traditional benches. Suddenly Hachakyum changed the benches into the first armadillos. The creatures leapt into the air and knocked down the two fire lords, humiliating them in front of the chief deity. The armadillos then “scampered off into the brush to become progenitors of their kind” (Gilbert Reference Gilbert1995:142; see also Stross Reference Stross2007:4).

Another story, a Tzotzil tale called Our Father's Footstool, told by Manuel López Calixto to anthropologist Gary Gossen in Chamula, adds additional nuance to Maya perceptions of armadillos and their origins:

The armadillo was the footstool of Our Father long ago. When he rested, Our Father sat on him. When he sat on him, little armadillos came out of the ground all around. He gave souls to all useful animals, so that they could be eaten (Gossen Reference Gossen1974:339).

This story serves not only as a refrain for the armadillo's mythical (foot)stool association, but also calls attention to many of the creature's salient characteristics: their underground domains, their edible meat, and even their high—seemingly spontaneous—reproduction rate.

Armadillos’ connection to fertility was likely due to that tendency to proliferate rapidly, much like cross-cultural associations of rabbits with reproduction (e.g., Abraham Reference Abraham1963:589), but further bolstered by the fact that armadillos make their homes in the fertile earth (Cordry Reference Cordry1980:187). As symbols of fertility, armadillos were often incorporated into dances and rituals associated with agricultural fecundity. In a study of dance masks from Mexico, ethnographer and artist Cordry documented a variety of armadillo masks worn in fertility dances near El Limón, Guerrero, including an armadillo-hide mask worn as a helmet and a face mask evoking an older man with pieces of armadillo hide attached in different places (Figure 8a). An unprovenanced Classic-period vessel featuring an armadillo with a human head recalls the armadillo-hide masks from Guerrero, with its exaggerated lips and cheeks and an emphasis on the forehead covered with armadillo armor (Figure 8b). Other “masks” used in Guerrero include an armadillo carving with a hole cut in its middle that could be worn around the hips like a ballplayer's yoke (Cordry Reference Cordry1980:185–190). The use of armadillo masks in dances is likewise attested on Classic-period Maya vases (Figure 8c). Cordry noted the relevance of agricultural growth cycles in the performance of armadillo dances, which began on May 6 and were carried out every Sunday during the month, while corn was planted (Cordry Reference Cordry1980:187).

Figure 8. (a) Armadillo masks from Guerrero. Photograph by Donald B. Cordry. Benson Latin American Collection, LLILAS Benson Latin American Studies and Collections, University of Texas at Austin; (b) Maya container in the form of an armadillo, with the head of a human or deity, in what is known as “potbelly” style (McInnis Thompson and Valdez Jr. Reference McInnis Thompson and Valdez2008). Photograph by Justin Kerr, K8178; (c) a “Chama-style” Maya vessel depicts individuals dancing while wearing armadillo masks. Photograph by Justin Kerr, K3041.

Actual armadillo shells were frequently used in planting crops across Mesoamerica. Anthropologist Starr (Reference Starr1908) noted the use of an armadillo carapace as a container for seed corn when Tzotzil, Mazatec, and Nahuatl speakers were sowing their milpa fields. Tzeltal speakers in Tenejapa use them to carry seeds for planting, in addition to making purses for other uses out of them (Hunn Reference Hunn1977:232). Working among Huichol communities at the turn of the twentieth century, Norwegian ethnographer Lumholtz (Reference Lumholtz1900:186) reported that “peculiar to certain rain-making feasts are a stick and a dried armadillo, which form the paraphernalia of the clown.” Lumholtz further describes how the bones and intestines of the dried armadillo were removed and the “front part” of the creature partially sewn up again, so that, in use, “the animal hangs down at one side of the clown, being suspended in a horizontal position by a loop which passes over his shoulder.”

Ceramics suggest that armadillo shells might have been similarly used by the Classic-period Maya. Although the contents of Maya vessels bearing armadillo shell patterns (e.g., Figure 4e) are usually irretrievable, one unprovenanced vessel provides a hint. That pot is marked with a particular logograph (known as T533 [Thompson Reference Thompson1962:145]) that epigrapher Tokovinine (Reference Tokovinine2012:294) suggests may represent a squash seed (Figure 9a). The use of armadillo shells as containers for crop seeds and Tzotzil and Tzeltal references to armadillos as squash-related animals help to shed light on the co-occurrence of seemingly disparate iconographies on this particular vessel. Another unprovenanced Classic-period vessel features an inverted appliqué armadillo wrapped around a container. The body of the armadillo and the body of the container merge at the shoulder of the pot, perhaps a visual expression of the full cycle of agricultural production, from the seeds carried in the fertile armadillo's shell to the harvested crops transformed and served in the container (Figure 9b; see also Houston Reference Houston2014:43, for an additional example of an armadillo bowl). On one enigmatic painted vessel (Figure 9c), a dying armadillo is shown handing a pottery vessel to a young woman standing above him—perhaps a nod to the fact that he will soon become a vessel himself?

Figure 9. (a) An unprovenanced vessel in a private collection displays an armadillo shell motif and repeated T533 logograph, possibly a sign for “squash seed.” Drawing by Franco D. Rossi; (b) a vessel wrapped by an inverted, appliqué armadillo. Photograph by Justin Kerr, K4919, Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University, Washington, DC; (c) a dying armadillo hands a cylindrical vessel to a woman. Photograph by Justin Kerr, detail from K1254.

For the ancient Maya, the armadillo's associations with fertility could tend toward lechery. The armadillo is sometimes considered an avatar of the underworld deity commonly known as God L, who wears a cape that mirrors the design of the armadillo's shell (Kerr and Kerr Reference Kerr and Kerr2006). On an unprovenanced Late Classic molded vessel, God L is depicted as both a human figure and as a clothed armadillo, illustrating the transformation of the one into the other (Figure 10a). God L, sometimes in his armadillo form, is often shown holding or fondling younger women (Taube and Taube Reference Taube, Taube, Halperin, Faust, Taube and Giguet2009). In one pair of such scenes, a young woman sits before a figure who ties a bracelet onto her wrist. In one instance the figure is an armadillo wearing human clothing (Figure 10b), in another it is God L wearing his cape with the armadillo shell design (Figure 10c).

Figure 10. (a) Molded ceramic vessel with God L in human and armadillo forms. Photograph by Justin Kerr, K514; (b) an armadillo dressed as a human ties a bracelet onto a young woman's wrist. Photograph by Justin Kerr, detail from K1227, Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University, Washington, DC; (c) God L, wearing a garment with the design of an armadillo shell, ties a bracelet onto a young woman's wrist. Photograph by Justin Kerr, detail from K511; (d) a young goddess, although shown with a dog, is named as yatan ibak', the “armadillo's wife,” in the accompanying text. From Dresden Codex 21b (Förstemann Reference Förstemann1880); (e) a Postclassic version of God L, again wearing an armadillo shell cape, caresses a young woman's chin. From Dresden Codex 23c (Förstemann Reference Förstemann1880); (f) a young goddess is shown with her armadillo husband. Photograph by Joaquín Otero, Museo de América, Madrid, detail from the Madrid Codex, f. 92d.

God L/the armadillo, paired with a young woman, can be found on a number of painted pottery vessels, as well as in the Dresden and Madrid Codices. Yet the armadillo is never named or depicted as a wahy, which seem bound to distinct human personalities rather than deities. The only glyphic reference currently known for the Classic Maya term for armadillo, ibak', comes from the Dresden Codex D21b, where a young earth goddess is identified as yatan ibak', the “armadillo's wife” (Figure 10d). This passage occurs on the pages immediately preceding a section of the codex known as the “conjugal almanacs,” which feature another image of the young goddess with an armadillo-cape-clad God L (Figure 10e). A correlate to the Dresden almanacs occurs in the Madrid Codex (M92-93; Knorosov Reference Knorosov and Coe1982:24), and, as in the Dresden Codex, the page that immediately precedes them (M92c) references a young woman and an armadillo, as an image rather than a text (Figure 10f). Knorosov (Reference Knorosov and Coe1982:63) insightfully suggested that these sections dealt with “women's portents,” and in general, these almanacs are thought to situate “conjugal activities”—copulation, marriage, childbearing—within the calendar, with agricultural metaphors used in glyphic descriptions of different outcomes (Bricker and Bricker Reference Bricker and Bricker2011:674–679). It is worth noting that both within the conjugal almanacs and the page preceding them, the agricultural terminology used in association with the armadillo and God L scenes is positive (Vail and Hernandez Reference Vail and Hernandez2018).

Thompson's (Reference Thompson1970:364–365) catalog of myths records several Mopan and K'ekchi' versions of a story that may be related to the Postclassic “conjugal almanacs.” In one of them, the male sun and female moon played a trick on the rain god, Chac, and fled together. Enraged, Chac hurled a thunderbolt at them as they were escaping. Sun turned into a turtle to evade the bolt, while Moon tried to slip into an armadillo shell. Moon, unfortunately, was struck. Afterward, her blood was gathered in 13 pottery jars. When they were opened 13 days later, 12 contained snakes and noxious insects, but the thirteenth held Moon. Upon releasing Moon from the jar, “Sun cohabited with her, the first sexual intercourse in the world.”

There is much to unpack in this story, but the prevalence of the number 13 is important, as it is both a base cycle for the 260-day Mesoamerican ritual calendar, long thought to approximate the human gestational period, and the average age (in years) at which a young woman might become concerned with “women's portents.” The conjugal almanacs of the Dresden and Madrid codices are oriented to the same ritual calendar. An unprovenanced Classic-period plate suggests that mythic associations of armadillos with human procreation extend back into the Classic period as well. The plate depicts a young, nude woman with long, loose hair in a “hocker pose”—a squatting, birth-giving position (Miller Reference Miller2005:66)—atop an inverted armadillo (Figure 11).

Figure 11. A nude woman squats atop an inverted armadillo on a painted Classic Maya plate. Photograph by Justin Kerr, K3876, Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University, Washington, DC.

In contrast to the gray fox, armadillos were a central source of protein, myth, and metaphor. They are readily found in Classic Maya texts and imagery, archaeological contexts, and historic and ethnographic accounts, shedding light on their varied associations with the underworld and fertility.

KNOWING MANY THINGS: THE “FOX,” THE “ARMADILLO,” AND ANCIENT MAYA CLASSIFICATIONS

The world depicted in Classic Maya art is, perhaps surprisingly, a world with very few animals at all (if by the term “animals” we mean simply non-human creatures found in Western natural taxonomies). Although certain naturalistic aspects in imagery incite the use of seemingly equivalent terms for common Western species, zoomorphic beings in Maya art rarely correspond to straightforward generic terms such as “deer,” “jaguar,” or “peccary.” Rather, the animals on pots are illustrations of specific beings, more akin to Wile E. Coyote and the Roadrunner (see also Houston and Scherer Reference Houston and Scherer2020). As we have shown, they are often named wahy individuals (like the “Red Chest[ed] Fox”) or depictions of creatures’ particular activities or behaviors, such as “the cuckolding deer” (Looper Reference Looper2019:73–94; Zender Reference Zender2017), the monkey scribe (Baker Reference Baker1992:223–225; Coe Reference Coe and Hammond1978), or the lascivious armadillo/God L, rather than an animal in its own right. The few naturalistic portrayals of non-human animals often seem to foreground these creatures as either companions to humans (like dogs) or as the quarry of human hunters, who are themselves commonly depicted dressed as animals.

Art historians and anthropologists tend to categorize beings in Maya art according to what they fundamentally are (e.g., as a monkey, even if that monkey is depicted on all fours and with deer hooves and antlers). Maya artists, however, seem more concerned with what beings do (e.g., their diurnal or nocturnal natures, walking or sitting upright, playing musical instruments, offering tribute). The people in the past who painted or sculpted the epigraphic and iconographic sources we draw on in this article made use of what they knew about animals to encode messages and meanings for purposes other than the communication of natural historical knowledge (though there is also ample evidence for what might be called natural historical knowledge on the part of the Classic-period Maya and other ancient pre-Columbian peoples; see, among others, Mayor Reference Mayor2005; Newman Reference Newman2016; Sugiyama et al. Reference Sugiyama, Valadez, Pérez, Rodríguez and Torres2013). In attempting to take seriously the many and multi-faceted zoomorphic, anthropomorphic, and anthropoeic aspects of animals on display in Classic Maya art, we are fully aware of the methodological dilemmas we face, not only in applying our own ideas about biological species and taxonomy to Classic Maya art and writing, but also in the rather narrow, in some ways arbitrary, and incomplete corpus to which we apply them. We argue, however, that it is precisely through what Viveiros de Castro (Reference Viveiros de Castro2004:5) has dubbed “controlled equivocation” (“controlled” in the sense that walking might be said to be a controlled way of falling), that we can learn something new about ancient categories. The Western taxonomic labels such as “fox” and “armadillo” that we employ here should be thought of and used only as provisional interpretations. That is, the demands of language require us to speak or write of “foxes” or “armadillos,” but what we mean by such terms (in relation to Classic Maya art) are actually suites of visual characteristics that for the time being we are calling “fox” or “armadillo”—much like archaeologists employ names for ceramic types and varieties even as they recognize that such labels had no meaning in the past (e.g., Philipps et al. Reference Philipps, Ford and Griffin1961:66).

What, then, are the distinctions between the “animals” recognized and identified in Classic Maya art by Western scholars and the kinds and categories of beings represented by ancient Maya artists? In Mayan languages, “animals” are classified as such by their means of locomotion or position—usually the fact that they walk on all fours. Houston and Scherer (Reference Houston and Scherer2020) have documented varieties of the term kot for “animal” in several Mayan languages, each in reference to quadrupedalism. Humans, it seems, might imitate (perhaps become?) animals by disguising their bodies with scents, feathers or fur, body paints, masks or animal prostheses, and by assuming the kot position. Hunters mingling with their prey, captives demeaned and dehumanized, or sacrificial victims all can be seen taking up animal forms and postures (Figure 12). On the other hand, animals shown as winik, or “persons,” often wear human clothing and take human poses, walking upright or sitting cross-legged.

Figure 12. Humans “becoming” deer by assuming the kot position and physical deer attributes. (a) Costumed hunters trying to trick their prey with costumes and whistles. Plate from Yucatan in the Museo Nacional, Mexico City. Drawing by Rossi after Pohl Reference Pohl and Pohl1985:Figure 9.1; (b) a humiliated and degraded captive dressed and defecating as a deer. Photograph by Justin Kerr, K728; (c) a sacrificial victim on all fours, his hair coiffed to resemble deer ears. Photograph by Justin Kerr, detail from K2781, Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University, Washington, DC.

Distinctions are rarely clear-cut, however, and the logic underlying the translation from imagery to “identification” in Western taxonomic systems can quickly become circular. Take, for example, epigrapher Kettunen's (Reference Kettunen, Mattila, Ito and Fink2019) distinctions among anthropomorphic, zoomorphic, and animal entities to catalog the kinds of beings in ancient Maya iconography. For Kettunen, anthropomorphic beings are animals having human characteristics or human beings/humanlike figures having animal characteristics; zoomorphic is a category which includes all non-human and non-anthropomorphic creatures that cannot be securely identified as “factual animals”—“unidentified animals, identified animals with unidentified zoomorphic attributes, or compositions of two or more identified animals” (Kettunen Reference Kettunen, Mattila, Ito and Fink2019:283). Beings designated as animals refer to those that “can be more or less securely identified,” or “a given (unidentified) animal figure [that] is rendered in a fairly realistic manner” (Kettunen Reference Kettunen, Mattila, Ito and Fink2019:285), as well as creatures that are rendered in a relatively realistic manner, but portrayed with imaginary features (e.g., personified wings). Kettunen further clarifies that in his classification system, composite beings are identified according to their bodies first, and then by their heads. Thus, an “anthropomorphic monkey” has a human or human-like body, but a monkey or simian-like head, while a “simian anthropomorph” has a monkey-like body with a human or human-like face. A “cervine monkey” combines a deer's body with a monkey-like face. The ordering is subjective and somewhat unstable, however: the “cervine monkey” is shown in a deer's quadrupedal position, but also has a monkey's prehensile tail (Figure 13). Kettunen's classifications are helpful in providing a clear and consistent system for parsing the wide variety of beings featured in Classic Maya art, but they ultimately rely on the characteristics that appear salient for a contemporary observer and a hierarchy rooted in contemporary Western taxonomies.

Figure 13. Beings according to Kettunen's (Reference Kettunen, Mattila, Ito and Fink2019) classification system. (a) An anthropomorphic monkey. Photograph by Justin Kerr, detail from K505; (b) a simian anthropomorph. Photograph by Justin Kerr, detail from K5152; (c) a cervine monkey. Photograph by Justin Kerr, detail from K927.

As noted above, the armadillo famously and cross-culturally tends to function as what Aristotle called a “dualizer”—an animal that falls under two classifications depending on which of its features is being explained (other examples include the ape and the bat; see Witt Reference Witt and Inwood2012:n5). Among the Maya, the animal likewise blurred categorical boundaries. So, too, did foxes. Perhaps most surprisingly, these two seemingly unrelated species—the fox and the armadillo—were sometimes connected to one another in Classic Maya art.

Feline Foxes

In Western biological taxonomy, foxes are members of the Canidae family, along with wolves, coyotes, jackals, and domestic dogs. The gray fox is not closely related to any other canid groups, having diverged from other canids around 8–12 million years ago (Castelló Reference Castelló2018:274). Tzeltal speakers in Tenejapa, Chiapas considered the gray fox part of what Hunn (Reference Hunn1977:215–222) calls the “covert complex: dog” (a group defined by perceived horizontal relationships of similarity or relatedness), but that group is more inclusive than the Western system's Canidae family. The Tzeltal dog complex incorporates not only domestic dogs and coyotes, but also raccoons, coatis, and kinkajous (of the Western Procyonidae family); otters, tayras, and weasels (of the Western Mustelidae family); skunks (of the Western Mephitidae family); and the jaguarundi (of the Western Felidae family). Hunn (Reference Hunn1977:222) notes, however, that the boundaries of the complex are “confused,” as house cats are closely associated with foxes (more so than domestic dogs).

In fact, gray foxes seem to be more commonly associated with felines than canines in several Maya taxonomies. Atran (Reference Atran, Medin and Atran1999:Figure 6.3), in his analysis of the mammal taxonomy provided to him by an Itzaj Maya woman, highlights the closest perceived “folkbiological” connection (the lowest taxonomic distance) among mammals as between the gray fox and the jaguarundi. That pair is then understood as less closely related to other members of the Western Felidae family (cat, margay, ocelot, jaguar, mountain lion, etc.), and still less closely related to Western canids (coyotes and dogs). Among K'ekchi' speakers in Alta Verapaz, Guatemala, feral house cats are said to have evolved into foxes (Wilson Reference Wilson1972:72–73). Moreover, the perceived similarity of the gray fox to the Western felid family is not strictly an indigenous perspective. The Relaciones de Yucatán also describes the gray fox as “like a big cat” (Asensio Reference Asensio1898:86), while in many parts of Mexico and Guatemala today, the gray fox, sometimes along with other small members of the felid family, is better known as the gato de(l) monte or gato montés (“wildcat”) than by the Spanish term zorro/zorra (“fox”).

Although the evidence is limited, Classic-period imagery suggests that foxes were closely associated with cats by the ancient Maya as well. The group that we have thus far called “fox” includes beings explicitly identified in texts as waax (Figure 3). It also includes creatures that are not mentioned in glyphic captions, but which share key visual characteristics with foxes that are explicitly identified: white cheeks and muzzles, a thin line of dark fur along the snout, prominent facial whiskers, recurved claws (Figure 14). Some of the creatures that similarly occupy the “fox” category, however, are labeled as a particular “fox” wahy, and simultaneously labeled with the logograph for “cat” or “feline,” HIIX, and, in some cases, depicted with feline spots or body parts (e.g., Figure 2a). One vessel, however, depicts a creature seated in an anthropomorphic position who shares the characteristic markers for waax, but is labeled in the accompanying caption only as HIIX (Figure 15)—that is, the “fox” is captioned simply by its generic grouping, as a “cat” or “feline.”

Figure 14. Uncaptioned foxes in Maya art (both “Chama-style” vessels) identifiable by their characteristic “fox” features. (a) Photograph by Justin Kerr, detail from K3040; (b) HM1177, William P Palmer, III Collection, Hudson Museum, University of Maine.

Figure 15. An anthropomorphic “fox”, labeled in the accompanying text as HIIX (“feline”). Photograph by Justin Kerr, detail from K3410.

Other images further bolster the ancient understanding of the fox as a member of the feline category. On another vase, a veritable menagerie of animals appears, each presenting its own cylindrical vessel as tribute (Figure 16). The vase is painted in an uncommon style and heavily restored, but the surviving portion of what appears to be a fox includes the distinctive recurved claw unknown to any other American canid. It appears in the first register, directly facing the deity to whom the gifts are being presented—a position that it shares with just two other felines, the crouching puma and standing jaguar on either side. The interpretation is speculative, but to us the vessel suggests an expression of the fox's closer relationship to the cats than to the other creatures depicted.

Figure 16. Animals presenting vases as tribute to a floating deity (God D). A (partially repainted) probable fox is shown, depicted upright, with a prominent recurved claw between a crouching puma and standing jaguar. Photograph by Justin Kerr, K3413, Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University, Washington, DC.

Armadillos of the Earth, Water, and Air

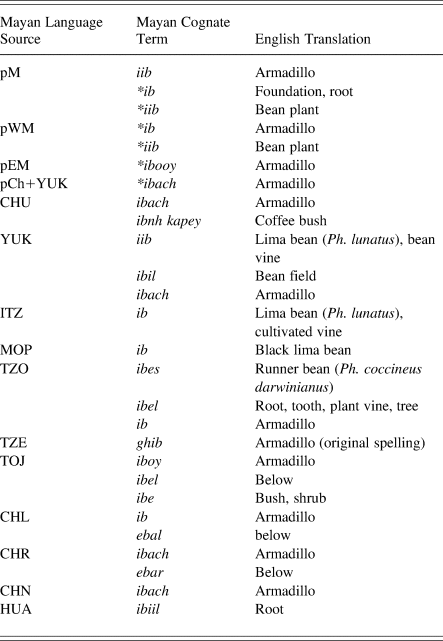

Armadillos exist both above and below the earth. Their ability to move between those worlds is not only encountered in Maya myths, narratives, texts, and imagery, but likewise observed in the conceptual relationships expressed when tracing the forms and meanings deriving from the proto-Mayan term for armadillo, iib (see Table 1). Armadillos are considered pests in suburban and agricultural areas, where they can quickly dig up large areas of land and cause extensive damage to crop roots by burrowing beneath them. Across Mayan languages, ib deals with the places where armadillos make their homes (“below,” “foundation,” “tree”), and with particular plants (“bean plant,” “lima bean;” Tokovinine Reference Tokovinine2014), or with terms that bridge those ideas, such as “root.” Taken together, the terms for ib in disparate Mayan languages convey a sense of place—an entire ecology of cultivated fields, where things like beans and shrubs grow above and roots and armadillos are busy below.

Table 1. Possible cognates of the ib gloss in hieroglyphic Mayan (after Tokovinine Reference Tokovinine2014:Table 1).

Abbreviations: pM, proto-Mayan; pWM, proto-Western Mayan; pEM, proto-Eastem Mayan; pCh, proto-Ch'olan; CHU, Chuj; YUK, Yukatek; ITZ, Itzaj; MOP, Mopan: TZO, Tzotzil; TZE, Tzeltal; TOJ, Tojolabal; CHL, Ch'ol; CHR, Ch'orti'; CHN, Chontal; HUA, Wastek

With their ability to cross bodies of water (either by inflating their stomachs and floating across or by holding their breath and walking below) and their armored shells, armadillos are often related to turtles or tortoises in Mesoamerican thought (as in the Nahuatl term for armadillo, “turtle/tortoise rabbit” [ayotochtli]). Tenejapan Tzeltal people consider armadillos to be related to both turtles and snakes (Hunn Reference Hunn1977:59, 231). One unprovenanced Maya pot features the clear body of an armadillo combined with a shell that blends aspects of an armadillo's with those of a turtle's. The shell features the armadillo's distinctive bands of triangles, but also a turtle-like plastron (lower shell), which armadillos do not have (Figure 17a). On the vessel illustrated in Figure 16, where a variety of animals present God D with tribute and gifts, an armadillo participates in the procession, raising a cylindrical pot above its arms (Figure 17b). Again, the shell features the triangles and bands, but is illustrated encircling the creature's entire body like a turtle, rather than like an armadillo.

Figure 17. (a) An unprovenanced vessel illustrates a turtle-like shell in combination with the triangular bands, long ears, and unwebbed digits of an armadillo. Drawing by Franco D. Rossi; (b) an armadillo presenting God D with a cylindrical vessel is similarly shown with a shell covering its entire body like a turtle's (detail from K3413). Drawing by Franco D. Rossi after Taube Reference Taube, Gómez-Pampa, Allen, Fedick and Jiménez-Osorio2003b:Figure 26.5.

Armadillos, along with bats, are excluded from the general mammal category by Tzeltal speakers in Tenejapa. For them, bats fly, thus resembling birds. Armadillos, which appear to lack hair, resemble reptiles (Hunn Reference Hunn1977:63). Tzotzil speakers in Zinacantán, on the other hand, believe that armadillos are transformations of turkey buzzards, perhaps because of their aged appearance (Laughlin Reference Laughlin1975:168). One Classic-period vessel suggests that some kind of relationship between armadillos and turkey vultures likewise may have been perceived in the past, with the bird shown hovering just above an emerging armadillo (Figure 18).

Figure 18. An armadillo emerges from its burrow beneath an iconographic hill. What appears to be a turkey vulture floats above, resting on an unidentified object (perhaps a lima bean?). Note that the armadillo's rodent-like incisors are unusual: they are not true to life, nor are they characteristic of most Classic Maya representations of armadillos (they are, however, a prominent element of the rabbit in the Aztec rabbit-turtle glyph for armadillo; see Figure 4c). Photograph by Justin Kerr, detail from K1254.

The seeming paradoxes of armadillos’ existence—burrowing, floating, and walking; appearing old yet spawning many young; looking like both a turtle and a rabbit (and perhaps a turkey vulture)—likely contributed to the rich and diverse symbolism and narrative corpus associated with the creature. For the Classic Maya, it appears to have confounded easy classification, just as it would do for later Europeans who attempted to fit it into their new reality.

Night Dancers

Foxes and armadillos are both nocturnal or crepuscular creatures, a fact that was sometimes highlighted by Classic Maya artists. One “Chama-style” vase shows a fox marked with the glyphic sign for darkness or night, AK'AB (Stone and Zender Reference Stone and Zender2011:144–145; Zender Reference Zender2007; Figure 19a). Another vessel features a seated armadillo against a dark background, which visually suggests not only a nighttime scene, but an underworldly one. The suggestion is furthered by the skeletal creatures that flank the armadillo and a nearby peccary that seems to be in distress (Figure 19b). In the Popol Vuh, the lords of Xibalba (the underworld) request that the disguised Hero Twins dance the armadillo dance, along with the dances of the weasel and the whippoorwill (all three are nocturnal animals).

Figure 19. (a) Classic Maya fox with an infixed AK'AB (darkness or night) sign in its forehead, a reference to the fox's nocturnal nature. Photograph by Justin Kerr, detail from K4339; (b) vessel depicting an armadillo and other nighttime creatures surrounding a peccary. Photograph by Justin Kerr, K2759.

A series of scenes, all from “Chama-style” vases, connects the armadillo to the fox through a specific local myth, dance, or procession. One vessel (Figure 20a) features both animals in a dark, black-background scene, marching and playing instruments in a line with a rabbit and a peccary, all dressed in human clothing. Although peccaries and rabbits are not nocturnal, they are most active at dawn and dusk, transitional times during which foxes and armadillos also tend to be active. Three of the four scenes in the “Chama-style” series are set against a yellow-to-orange background, which may suggest they are taking place during dawn or dusk—heightened periods of activity for the animals illustrated in them.

Figure 20. A series of “Chama-style” vessels depicting a procession of varied animals, which always include a drum-playing armadillo, a rattle-playing fox, and a carapace-carrying rabbit. Photographs by Justin Kerr, (a) K3041, (b) K3040, (c) K3332, and (d) K5104.

All four of the vessels illustrate what is clearly the same event, albeit with slight variations in its participants. In each, the fox plays a pair of rattles and the armadillo a drum, and the rabbit usually carries a turtle carapace. Although other animals sometimes appear in the scenes—a peccary, a deer, a jaguar—the armadillo, the fox, and the rabbit are the only ones consistently featured. The armadillo and the fox are always shown in immediate succession (Figures 20b–20d).

What exactly is transpiring in these similar scenes is unknowable, at least with the information we have at present. We can, however, acknowledge some things with certainty. These vases illustrate the same procession of “animals”: beings who walk upright, wear human clothing, and play musical instruments. But those simple observations raise a number of questions: Are these animals? More-than-animal persons? Humans dressed as animals? Is this a depiction of an actual historical event, a series of processional events, or are they simply a local mythological narrative from the Chama region in the eighth-century a.d.? Is it implied that all the animals visible in Figures 20c (K3332) and 20d (K5104) are also part of the processions portrayed in Figures 20a and 20b? What is it about the armadillo, the fox, and the rabbit that relate them to one another and make them necessary to the scene? Is it some characteristic of the animals themselves or of their activities (the specific instruments played by each one)?

There is clearly an observable logic underpinning these scenes, but it is impossible to know the world or system of thought that governs what we are seeing. Yet they are undeniably about something: they represent some kind of object (other than the representation itself), even if that object is opaque or ultimately inaccessible (Keane Reference Keane2013:186; see also Carrithers et al. Reference Carrithers, Candea, Sykes, Holbraad and Venkatesan2010:160). Even if the reality represented in Classic Maya art is not fully intelligible or translatable, we can still catch a glimpse of that world—one that is filled with “Red Chest[ed] Fox” demons, turkey vultures transformed into armadillos, and a raucous band of burrowers.

CONCLUSIONS

Deciphering the meaning of ancient texts and imagery is a difficult challenge. Little testing and winnowing of meaning can occur. Classicists have pointed to instances of ontological dissonance even in seemingly familiar literature from the Western canon: Homer used the word chloros to describe the color of both green grass and yellow honey, described the sky as iron or bronze, perhaps because of its solid fixity, and called the sea “wine-faced” to allude not to its tint, but presumably to its shine, just like the liquid inside a cup (Sassi Reference Sassi2017; see also Newman Reference Newman2019:141). Where Sir Isaac Newton saw seven colors in a rainbow, Aristotle saw only three (Lloyd Reference Lloyd2007:12). The ancient Maya experience of non-human animals is even more difficult to grasp for Western scholars. Populated by demons, susceptible to transformations between seemingly distinct beings (human, animal, and otherwise), and characterized by relations that blur the boundaries of biological classifications understood in the West as real, there is no neutral vocabulary for description or discussion, no point of communication without misunderstanding between the radical alterities of one world and another. Yet anthropologists carry on in our discipline without falling into despair and, indeed, enough understanding can be gained to recognize other ontologies and, at times, point out where they differ from our own (Lloyd Reference Lloyd2020:52–53).

In this article, we have highlighted such points of ontological difference by examining in detail two seemingly disparate and relatively minor species in Classic Maya art: foxes and armadillos. Although we began with salient physical characteristics that provide points of overlap between Western biological taxonomy and ancient Maya representations, we have asked how those beings are illustrated in Classic Maya imagery and described in accompanying texts, rather than simply asking if those beings are depicted and considering them identifiable. We have “taken seriously” (see Candea Reference Candea2011; Viveiros de Castro Reference Viveiros de Castro2011:131–133) those illustrations, so that what we might have otherwise labeled as a “fox,” becomes a specific more-than-fox, the “Red Chest[ed] Fox,” or rather, a bipedal, rattle-playing, fox-like being. An “armadillo,” likewise, becomes the transformation of another creature or a specific god, a husband, or a bipedal, drum-playing, armadillo-like being. By taking those creatures as more than generalized examples of particular kinds (i.e., simply “a fox” or “an armadillo”), we have traced how they enter into and shape relations with and among humans, animals, plants, deities, and other entities. That exercise reveals not only that Western taxonomic labels such as “fox” and “armadillo” are merely provisional terms that we employ for a suite of visual characteristics and their intended meanings, but that those beings are perhaps not so disparate and minor as they seemed at the start. In particular, the events depicted on “Chama-style” vases from the Alta Verapaz region of Guatemala suggest that some kind of connection existed between the “fox” and the “armadillo” in the past, even if we cannot know the specifics of those relations.

Like Archilochus's fox and hedgehog for Isaiah Berlin, the intended meanings behind Classic Maya representations of the gray fox and the armadillo, whether separately or together, are opaque. Yet, also like the fox and the hedgehog, they invite viewers to rethink both animals, humans, and the many beings in between those seemingly distinct categories.

RESUMEN

Este artículo investiga cómo los mayas clásicos entendían dos especies de animales: el zorro (gris) y el armadillo. Usamos estas dos especies como un punto de entrada al sistema de conocimiento con el cual los mayas clásicos categorizaban el mundo de animales no-humanos.

Comenzando con el zorro gris, presentamos las características físicas esenciales que parecen haber sido enfatizadas por los antiguos artistas mayas, incluyendo, por ejemplo, el hocico blanco del zorro y su distintiva garra curva para trepar árboles. Discutimos el término general para el zorro en la escritura jeroglífica, waax, que se escribía tanto silábicamente como con un logograma poco usado. También revisamos los nombres específicos dados a criaturas wahy parecidas a zorros, como el “Zorro de Pecho Rojo”. Luego exploramos cómo los zorros han sido cazados y comercializados, percibidos simbólicamente, y entendidos como espíritus compañeros en relatos históricos y etnografías contemporáneas.

Pasando al armadillo, discutimos cómo la criatura fue entendida como un “dualizador” (un ser que cruza categorías), tanto por los indígenas mesoamericanos como por los europeos. Además del papel del armadillo como un importante y deseable recurso alimenticio, examinamos tradiciones míticas ampliamente compartidas según las cuales un Señor de la Tierra usa el armadillo como su escabel, y también diversa evidencia arqueológica y etnográfica que resalta las asociaciones cercanas del armadillo con la reproducción y la fertilidad, tanto humana como agrícola.

Finalmente, sugerimos que en lugar de aceptar las imágenes y los textos antiguos como ejemplos generalizados de tipos particulares (es decir, en este caso, como “un zorro” o “un armadillo” sin más), deberíamos preguntarnos cómo referencian seres específicos. Estos seres incluyen a menudo individuos con nombres propios, que se involucran en comportamientos particulares y se relacionan con otras entidades (tanto humanas como no humanas) de formas distintas. Utilizamos una serie de vasijas de “estilo Chama” en las que un zorro gris y un armadillo ocupan un lugar destacado para llamar la atención a las limitaciones de aplicar taxonomías occidentales a otros sistemas de conocimiento, pero también para mostrar algunas posibilidades de cómo podemos vislumbrar formas de organizar un mundo radicalmente diferente.