1. Cultural frameworks for improvisation

Derek Bailey argues that improvisation ‘pre-dates any other music’, writing that, ‘mankind’s first musical performance couldn’t have been anything other than a free improvisation’ (Bailey 1992: 83). Improvisation, then, could be considered a ‘basic instinct, an essential force in sustaining life’ (Bailey 1992: 140). Yet, musical improvisation is not identical across cultures. There are aesthetic imperatives in improvisation that are shaped by the ‘cultural value ascribed to its practice’ (Blackwell and Young Reference Blackwell and Young2004: 125). Frameworks for an improvisatory musical practice reveal much about cultural aesthetics of sound, the relationship between the individual and the broader social milieu and the higher purpose of music at large (Fischlin, Heble and Monson Reference Fischlin, Heble and Monson2004).

Exploring different cultural frameworks for improvisation has been a driving force in my own musical practice: I have explored improvisation in genres ranging from Indian classical music, post-rock, dub, free jazz, trip-hop, IDM, the blues, West African drumming, world fusion, noise and nu-folk. With each new improvisatory framework, there are new cultural values to understand and embody: the importance of a particular note, how rhythmic phrasing changes mood, which sounds are cliché and trite and which sounds are efficacious. For example, when I began studying Indian classical music, I had to unlearn most of my knowledge of tonality and try to understand the concept of raga, an aesthetic gestalt rather than a scale or key. At another extreme, when I began performing in ‘free’ improvisation contexts, I was shocked to be told that the best thing to do was to avoid recognisable melody or rhythm altogether.

It seems then reductive to suggest, as Bailey has argued, that improvisation “across all cultures” can be situated within two “basic” categories of idiomatic and non-idiomatic. As a performer of both Indian classical and electroacoustic music, I find this division between idiomatic (structured) and non-idiomatic (unstructured) forms of improvisation problematic. Bailey writes that idiomatic improvisation is ‘mainly concerned with the expression of that idiom … and takes its identity and motivation from that idiom’ (Bailey Reference Bailey1982: xi). For example, in the case of Indian classical music, while improvisation accounts for the majority of a performance structure, the music must strictly follow the correct ‘grammar’ of the raga.Footnote 1 Idiomatic improvisation might be defined as a ‘highly controlled improvised performance’ and quite distinct from ‘freer creative music-making’ (Blackwell and Young Reference Blackwell and Young2004: 125). Some examples of idiomatic improvisation practice include Baroque organ, the blues, more traditional jazz, maqam, Indian classical music, flamenco and Indonesian gamelan. Most non-idiomatic improvisation ‘is not usually tied to representing an idiomatic identity’ and is in a sense reactive to the establishment of idioms, rejecting the traditional musical values of the surrounding cultural environment (Bailey 1992: xii). Non-idiomatic improvisation might be defined as the musical ‘pursuit of change’, or perhaps even as the ‘unthinkable event-horizon of the possible’ (Fischlin Reference Fischlin2009: 3 and 5). Western harmony, melody, rhythm and pre-determined temporal structures are often avoided (or at least discouraged) in much non-idiomatic improvisation. The sonic framework is soluble and malleable to the personal whims of the individual artist or improvising ensemble. Non-idiomatic improvisation, according to Bailey, is predominantly a Western-centric phenomenon and includes genres such as free jazz, free improv, noise and electroacoustic improvisation.

In Bailey’s categorisation, it seems that there is little evidence of non-idiomatic or ‘free’ improvisation in a non-Western music.Footnote 2 I have spent considerable energy investigating the potential of applying the principles of North Indian raga to Irish traditional music (Noone Reference Noone2016) and more recently in exploring the performance possibilities of an electroacoustic North Indian-style lute dubbed the sarode na suíll; much of my interest has been in how to transcend this dualistic understanding of improvisation and explore what ‘free’ improvisation with an Indian classical instrument might entail. Despite the limitations of Bailey’s definition, it is important to acknowledge that there is certainly a tension between performing a ‘non-Western’ and improvised style, such as Indian classical music, and more Western-orientated ‘free’ forms of improvisation. As a performer coming from a background in Indian classical music, the freedom of electroacoustic improvisation can sometimes be almost overwhelming. Drawing from my experience learning the sarode, the organisational structures of Indian classical improvisation are what guides the performer, where all musical inspiration originates and what constitutes the main part of the teacher’s transmission to a student. In electroacoustic improvisation, there is no explicit and discernible ‘top-down’ ordinance or guidance; rather, there is a ‘limitless universe of sound’ (Young Reference Young1996: 73). The improvisation structures of Indian classical music can sometimes feel too rigid and prescriptive within a ‘free improv’ context. It also feels disingenuous to play in a ‘free’ improvisation context and simply reproduce repertoire that comes directly from my Indian classical training. As I have discussed at length elsewhere (Noone Reference Noone2020a), there are thorny ethical issues to navigate when a non-Western instrument is utilised in electroacoustic music; the danger is that the non-Western instrument simply becomes an exotic sound source in the electronic palette.

Integrating and transcending multiple cultural frameworks for musical improvisation is a challenge. There are inevitable tensions between the cultural rules of an idiom and the desire to push the boundaries of an instrumental practice.Footnote 3 Resolving this tension has been a large part of my journey towards more experimental performance styles such as ‘free’ improvisation and electroacoustic music. In this article, I would like to answer several interconnected questions that have arisen from my own practice-based research: How do we go beyond the idiomatic sounds of our instrument? How to push the boundaries of musical expression and find new ways to say something? How do other performers of a non-Western instrument from an idiomatic tradition approach electroacoustic improvisation? Is there a way to improvise that goes across cultures – a transcultural approach to electroacoustic improvisation? Fischlin raises similar concerns when he asks, ‘how does improvisation approximate unspeakable and inexpressible, yet fundamental and defining, conditions of being human?’ (2009: 2) This line of inquiry relates to what Fischlin has described as the spiritual or ‘unspeakable component that so many scholarly studies of improvisation avoid’ (2009: 2). To address this, Fischlin asks, ‘[w]here does improvisation really come from? What does improvisation signify, especially as a shared cultural practice deeply embedded in all human histories?’ (2009: 2). In my own work, I have been seeking an approach to improvisation that can transcend yet also resolve idiomatic concerns; to find a way to improvise that goes beyond or perhaps even before culture.

2. Synchronic and diachronic dimensions of culture

To answer these questions, I suggest that first we expand our cultural view of improvisation beyond the debate for idiomatic vs. non-idiomatic and include two other dimensions: the synchronic and the diachronic. The synchronic dimension operates on a horizontal axis. Along this axis, we can discuss the transcultural elements of improvisation, investigate how improvisation operates across cultures and examine the movement and exchange of musical ideas. Arguably, much of the inspiration for Western improvisation has emerged out of this synchronic, cross-cultural impulse (Gluck Reference Gluck2008). Many early American electroacoustic composers and improvisers drew upon images and musical structures from non-Western cultures, most notably Terry Riley and Pauline Oliveros.Footnote 4 As Collins writes, it was an interest in ‘sustained textures, drones and modal just-intoned harmonics [which] led both Riley and Oliveros into deeper investigation of non-Western music and culture’ (Collins Reference Collins, Collins and d’Escriván2017: 46). In the case of Riley, this interest led to an exploration of North Indian vocal music and with Oliveros, a combination of Buddhist and Taoist philosophies. This synchronic nature of electroacoustic improvisation has continued unabated into the postmodern era. As Gluck writes, ‘reaching across cultures in search of inspiration, musical materials and forms, and new ideas is not a new one, but it is occurring now with greater frequency’ (2008: 141).

On another plane, we could expand our understanding of culture in a vertical, temporal or historical manner. This backwards movement of cultural knowledge could be described as the diachronic dimension of culture. To explore the transcultural then could be a journey that goes backwards and forwards in cultural time as well as horizontally across. While many electroacoustic improvisers have looked across cultures for inspiration, others have investigated early historical cultural frameworks, or what Davis describes as ‘premodern ways of thinking’ (Davis Reference Davis1998: 12). In fact, Bach argues that there is a parallel history of electroacoustic improvisation that ‘pre-dates the advent of the computer’ (Bach Reference Bach2003: 8). By reaching back in cultural time, Bach suggests that there is potential for electroacoustic improvisers to redraw ‘connections with myths and cultural beliefs that existed long before’ (2003: 8). Ed Sarath writes that improvisers are uniquely equipped to explore the historical and diachronic dimension of culture, as ‘the improviser experiences time in an inner-directed or “vertical” manner’ (Sarath Reference Sarath1996: 1). In a phenomenological sense, he argues that improvisers are adept at experiences of a heightened, time-altering consciousness. In fact, heightened performance states of improvisation are ‘characterized by experiencing the present as a localized point … in which the sense of past-present-future is subsumed within an eternal sense of presence’ (Sarath Reference Sarath1996: 3). Improvisation is perhaps one of the most powerful musical vehicles for accessing the creative intersection of the synchronic and diachronic dimensions of culture. Fischlin writes that improvisation ‘brings together diachronous and synchronous histories … and allows for simultaneous consonance and dissonance, unexpected hybridities, provocative and productive cacophonies’ (Fischlin Reference Fischlin2009:7).

In my own search for a transcultural framework for improvisation, I have explored both synchronic and diachronic dimensions of culture. In all my experiences, the commonality was often not cross-cultural musical sympathies, the similarities were not predominantly along the synchronic dimension. More often, the common thread in my musical experiences have been of a diachronic nature, something that went downwards, internal and arguably before culture. I have described these experiences elsewhere as ‘transcendent’ connections in ‘the world of feeling’ (Noone Reference Noone, Bussey and Mozzini-Alister2020b), similar to Sarath’s description of the ‘eternal sense of presence’ or Fischlin’s (2009) focus on the ‘unnameable’ component of improvisation. While musical improvisation might not be a cultural universal, the desire for transcendent experience is a core, perhaps primal, human need. If the impulse to transcend is a universal human need, then perhaps musical improvisation is a method to create a spark for transcendent experience. Improvisation then could be understood as a conflux of the synchronic–diachronic dimensions of cultural time, a transcultural and transcendent state of musical being. Surely the transcendent impulse, manifested through the practice of musical improvisation, existed long before our concerns over idiomatic or cultural frameworks. If we can identify the origins of this transcendent impulse, how might it be possible to imagine it forward?

3. Improvisation and the metaphysical imaginary

Musical improvisation has been intimately intertwined for thousands of years with some of our most important metaphysical concerns. Music, particularly of an improvised nature, was an intrinsic part of humanity’s earliest religious experience. The development of rhythmic entrainment and pitch improvisation gave humans the ability to ‘think at a distance’ and engage in ‘transcendental social’ interaction (Tomlinson Reference Tomlinson2015: 288). This is because musical improvisation is a ‘unique activity in the degree to which it highlights somatic experience while structuring it according to the complex and abstract’ (2015: 289). Tomlinson labels this dimension of musical experience as the ‘metaphysical imaginary’ (2015: 272). The metaphysical imaginary is a phenomenology of the transcendent or heightened spiritual experience.Footnote 5 It is that heightened state of affect, sense of Other-ness, rapture or transcendence that music is so potent in manifesting. Much like the preceding conception of the synchronic and diachronic, the metaphysical imaginary ‘enables the movement of the mind upwards and downward, as well as outward through lateral expansion’ (2015: 272). As Tomlinson writes, the metaphysical imaginary is the ‘transcendental social’ function of music that enabled our ancestors to ‘enter the sphere of the transcendence [and] posit a source for all supersensible percepts’ (2015: 272).

Both popular electronic music and electroacoustic music in various forms have often been linked to transcendence and the metaphysical (Richard Reference Richard1997; Till Reference Till, Deacy and Arweck2009; Lykartsis 2013). A number of electroacoustic artists have explored the metaphysical imaginary in improvisation strategies, through shamanism (Kendall Reference Kendall2010, Reference Kendall2011), Buddhist philosophies of impermanence (Bossis Reference Bossis2008), Indian classical music (Bahn Reference Bahn2010) and even the inter-cultural transcendence of self (Frisk Reference Frisk2020). In a South-East Asian context, Lippit has investigated how Indonesian electroacoustic ensembles are exploring the metaphysical, ‘at the edge of more popular genres such as punk, metal … incorporating traditional and indigenous musical influences’ (Lippit Reference Lippit2016: 72). The Javanese noise band, Senyawa, ‘combines various indigenous Indonesian art forms with a hard-edged noisy sound’ (Leinhart in Lippit Reference Lippit2016: 74). The members of the group refer to direct influences from trance-inducing forms of traditional Indonesian singing such as Raego and ritualistic Javanese horse dance called Jaranan (2016: 73). Lippit describes that, ‘Senyawa’s performances simulate Jaranan’s intense build up of energy followed by a gradual release. This dramaturgy combined with fast riffs played at ear-splitting levels and ecstatic screams is explosive’ (2016:74). In a more subdued manner, Komungo player Jin Hi Kim explicitly draws upon the metaphysical nature of traditional Korean music in her electroacoustic improvisation. She describes her work to be ‘inspired by Korean aesthetics of Buddhism and Shamanism’ (Kim Reference Kim2020). Kim writes that she sometimes has a ‘shamanistic experience in [her] computer programs’ when playing electric komungo using MAX/MSP. Kim outlines that, ‘the computer extends my limit [and] goes beyond [the] norm of acoustic komungo. Time is expanded with my electric komungo. So for me the evolution of the instrument is like [a] butterfly metamorphosis’ (Kim Reference Kim2020). In a similar way to Buddhist precepts, Kim constructs eight parameters in her exploration of the improvisation moment:

-

1. Empty mind (so new sound can burst out from the empty space).

-

2. Follow the sound coming to you (do not control the sound around you).

-

3. Listening more than playing (accepting others).

-

4. No boundary (accept differences and go beyond comfort zone).

-

5. Perceive a field of sound rather than cells of tone and rhythm.

-

6. Observe the sonic filed with your intuition rather than knowledge of sonic materials (awareness of collective creativity rather than individuality).

-

7. Aesthetic balance between yin and yang (stability within free form, calm energy inside busting motion).

-

8. Momentary virtue (inspiration to improvisers and listeners).

In a similar manner, I have explored electroacoustic music improvisation as a vehicle for ‘spiritual transcendence’ drawing on the principles of Indian classical music (Noone Reference Noone2020a: 121). In my piece For Here There is No Place, I questioned how Indian spiritual concepts such as nada and shruti might be applied to electroacoustic music. This improvisation did not follow the rules of Indian classical music; rather, it drew on the metaphysics of Indian aesthetics through what I described as a process of ‘live evolving drones based on improvised tones’ (2020a: 124). In my own work and the other examples described previously, the use of metaphysical or spiritual metaphors are flights of imagination, or what Abrams describes as the way the senses throw themselves ‘beyond what is immediately given’ (Abrams Reference Abrams1997: 58). The use of metaphors, such as the metaphysical imaginary, can be used in electroacoustic improvisation as a way to go beyond, ‘in order to make tentative contact with the other side of things that we do not sense directly, with the hidden or invisible aspects of the sensible’ (Abrams Reference Abrams1997: 58).

4. The Metaphysical Imaginary as Metaphor

Derek Bailey states that much ‘free’ improvisation requires some level of structure or intention. ‘Myths, poems, political statements, ancient rituals, paintings, mathematical systems; it seems that any overall pattern must be imposed to save music from its endemic formlessness’ (1992: 111). Tomlinson describes the metaphysical imaginary in a similar fashion, defining it as a ‘cognitive anchor’ for ‘easing the difficulties we have in conceiving of the supernatural’ (2015: 276). My use of the metaphysical imaginary as a creative metaphor is a continuation of the tradition of employing the metaphoric to give meaning to electroacoustic work. Young argues that one of ‘the most powerful potentials of recognisable real-world sounds in electroacoustic music lies in the creation of symbols’ (1996: 73): ‘The concept of the symbol has arisen in humans as a way of imbuing recognisable objects with associations that go beyond the immediate object (the sign) in order to convey ideas or feelings about aspects of our existence that are difficult to express in straightforward terms’ (1996: 79–80). Lakoff and Johnson state that a work of art allows humans to develop ‘new experiential gestalts and, therefore, new coherences’ (Lakoff and Johnson Reference Lakoff and Johnson1980: 235); creating metaphors in electroacoustic music is an attempt at ‘imposing gestalts that are structured by natural dimensions of experience’ (1980: 235). Examples of the use of metaphor in electroacoustic music include Jin Hi Kim’s ‘Living Tones’ concept (Kim Reference Kim2019), the use of new language to describe electronic sounds (Smalley Reference Smalley and Emmerson1986), applying system dynamics as an aesthetic structure (Whalley Reference Whalley2000) and imbuing geographical place and objects in nature with sonic agency (Mcauliffe Reference Mcauliffe2017).

In my own work, I have adopted the metaphysical imaginary as a metaphor for capturing the common spiritual dimension of my diverse performance experiences. Glenn Bach has utilised a similar approach in his practice, exploring a deepening of spiritual associations within electroacoustic music ‘through the embrace of metaphor’ (2003: 8). Using a computer interface in electroacoustic music, as Bach writes, is a kind of ‘back and forth’ journey between the diachronic and the synchronic dimension of cultural time and space, or ‘a threshold, a crossing and the interzone between this world and the other’ (2003: 5). The digital interface can potentially be understood as a metaphor for spiritual journey, a quest for new sounds that transcend temporal and cultural frameworks. The ‘interzone’ of the computer may be conceived as a metaphysical space and the electroacoustic interface a material metaphor for accessing the metaphysical imaginary. ‘[T]he laptop is a means of undertaking profound shamanic journeys back and forth from the audible to inaudible realms, and everywhere in between. Software is the peyote that the shaman ingests to access the other world’ (2003: 5).

5. The metaphysical as cognitive anchor

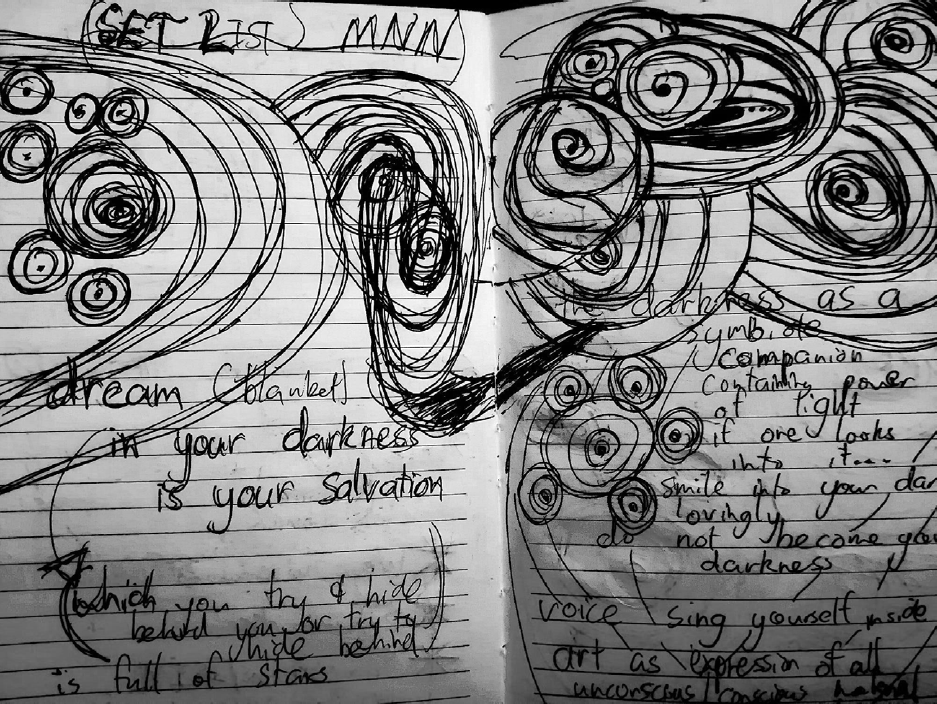

In my electroacoustic improvisations, I am attempting to reach deeper into this ‘interzone’ of the digital world through applying Tomlinson’s concept of the metaphysical imaginary in novel and intuitive ways. To explain, I will give a brief account of two performances that outline the development of my use of the metaphysical imaginary as a metaphoric framework. First, in 2019 I was invited to perform at a free improv venue in Minneapolis. I consciously decided to avoid any pre-rehearsed material and recognisable repetitive rhythmic or melodic structures. At the same time my intention was to try to manifest a similar kind of affective state from my experiences with Indian classical music. Uneasy about an entire lack of set list, I made one concession and used a rough sketch from my dream journal from the previous night as my ‘score’. The subconscious images were spirals and circles no doubt taken from my developing interest in Irish megalithic artwork (Figure 1). In this performance, I used the dream sketch as a kind of subliminal graphic score. Rather than simply trying to match sounds to the spirals and circles, I used the images as a catalyst for entering into a meditative state that mirrored the feeling of the previous night’s dream. From this place of stillness, I would tentatively play acoustic material on the sarode through randomised patches of custom effects, pursuing an enveloping sound world that would replicate my inner state. The outcome, while not perfect, made it clear that improvising solo in a non-idiomatic fashion for an extended period is possible using the sarode and electronics. I was eager to develop this approach further, sensing that it was especially important to have some kind of metaphoric or subconscious ‘anchor’ to help channel the music.

Figure 1. Score for improvisation performance.

The second performance was in the same year at another improv venue in Brooklyn. I was a research fellow at Princeton University working to deepen my understanding of the music software ChucK. Overwhelmed by screen time and the mental fatigue of coding, I spent my evenings reading Tomlinson’s (2015) work about the pre-historic mind, stone tools and the metaphysical imaginary. These two worlds, the pre-historic and the digital, began to meld in my subconscious and my dream journal became filled with a mixture of Neolithic rock spirals and ChucK code. Again, when I planned my solo set, I resolved to improvise in a non-idiomatic manner. Based on my previous experiences and Tomlinson’s conception of the importance of a ‘cognitive anchor’ in musical transcendence, I knew that I needed something to ground the improvisations. As Young writes, establishing ‘psychological threads that can meaningfully link sonic materials’ is of crucial importance to electroacoustic artists (1996: 76). For this performance, I used four elementals as the catalyst for this performance: ‘Stone/Air/Wood/Steel’ (Sound example 1). For ‘Wood’ I used a drumstick as an exploratory medium for making sound on my instrument; ‘Air’ was an exploration of the voice and breathing through the internal microphone of the instrument; ‘Steel’ was an invitation to explore the metallic fretboard of the instrument with the steel strings; and ‘Stone’ was an improvisation based on extended technique using a rock I had brought with me from Ireland. The success of this second performance in particular led me to delve deeper into the diachronic dimension of improvisation through exploring the transcendent musical experiences of the pre-historic world. In particular, based on my experience using spirals and circles as a kind of graphic score, I wondered if there was any parallel in the ancient world. I began to further investigate early rituals of transcendence in the Neolithic world and the role that improvisation played in manifesting the metaphysical. This path of inquiry led me to the world of archaeoacoustics and in particular the megalithic tombs of the Boyne Valley in Ireland.

6. The metaphysical and the megalithic

Archaeoacoustics ‘focusses on the role of sound in human behaviour from earliest times’ (Scarre and Lawson 2006: viii). It explores the sonic dimension of pre-history to gain insight into early human experience and cognition. Archaeoacoustics investigates the use and meaning of pre-historic sonic artefacts, such as instruments and built structures, using ‘material culture as material metaphor’ (Coward and Gamble Reference Coward, Gamble, Malafouris and Renfrew2010: 47). Some archaeoacoustic research explores the sonic landscape of Neolithic people through investigations of stone monuments, generally known as megalithic passage tombs. Footnote 6 These passage tombs were built across Western Europe, particularly in the UK and Ireland, throughout the Neolithic period. Footnote 7 Most research has focused on identifying the resonant frequencies of the inner chambers of the tombs. Amongst their findings, scholars have noted a recurring pattern of frequency around 110 Hz, leading to the conclusion that they were designed particularly for amplifying the natural frequency of the male voice (Jahn, Devereux and Ibison Reference Jahn, Devereux and Ibison1996; Devereux Reference Devereux2001;). By extension, scholars have argued that the chambers may have been used for ritualistic purposes including some kind of music, such as chanting (Devereux Reference Devereux2001: 88–9).

It is not just the stone chambers that have been of interest to archaeoacoustic scholars but also the intricate art on many of the passage stones, particularly in Ireland’s most famous ancient monument Newgrange. The ubiquitous nature of megalithic geometric motifs has led many to question their meaning. Some argue that they are astronomical observations (Brennan Reference Brennan1994), others that they are anthropomorphic deities (Jones Reference Jones2013) or even that they are representations of hallucinations experienced by participants in Neolithic rituals (Devereux Reference Devereux2001). Robert Jahn has suggested that there are ‘similarities of certain sketches with resonant sound patterns characterizing these chambers’ (Jahn et al. Reference Jahn, Devereux and Ibison1996: 657). Jahn and his research team noted that a number of the designs featuring concentric circles, eclipses or spirals ‘are not unlike the plan views of the acoustical mappings’ of megalithic chambers (Jahn, Devereux and Ibison Reference Jahn, Devereux and Ibison1995: 9). Jahn especially notes that, ‘two zig-zag trains etched on the corbel at the left side of the west sub-chamber of Newgrange have precisely the same number of “nodes” and “antinodes” as the resonant standing wave pattern we mapped from the chamber center out along the passage’ (1995: 9).

It is important to note that theories on the sonics of Neolithic Ireland are speculative. Devereux concedes that at first glance, the idea that, ‘these enigmatic carvings [are] related to the acoustical environment in the monument at ritual times … seems an unlikely proposition’ (2001: 89–90). The main problem is attempting to understand how ‘the Stone Age ritualists at Newgrange’ could have imagined soundwaves (2001: 90). Footnote 8 Most electroacoustic music which draws upon archaeoacoustics is not an attempt at reconstruction of ancient practice but rather an ‘experimental and contemporary approach to interpreting ephemeral qualities of the archaeological record; an attempt to create new art from the residue of ancient craft’ (Crewdson and Watson Reference Crewdson, Watson and Banfield2009: 5). Swedish improviser and composer Fawcus has explored this in his work, which draws inspiration from megalithic art. Fawcus describes his performances as ‘the creation of music as a live “ritual” or spiritual process involving emotional intensity and elements of uncontrolled or partially steered creativity’ (2012: 23).

Electronic music is, for me, similar to the use of sound in the prehistoric cave or megalithic construction, particularly in the relationship between the composer, her sound material and sonic tools. There is a certain directness that is common to the creation of electronic music and for manipulating the acoustic properties of a cave or building to create a soundscape or composition. (2012: 16)

Watson states that creative practice has been central to his research process, ‘because archaeological methods tend to only investigate certain kinds of experiences, and often have the effect of silencing the past’ (2020). Watson works in multimedia performance to challenge the conventions of traditional archaeology by introducing much more challenging approaches, which account for ‘the breadth of human sensory experience’ (2020). Watson’s performances work on three principles: ‘evidence, interpretation and creative composition’ (Crewdson and Watson Reference Crewdson, Watson and Banfield2009: 9). His work is ‘inspired and informed by a combination of empirical evidence, extrapolation, experimentation and theoretical interpretation’, utilising the ‘collection of a sound palette of Neolithic instruments via recordings of reconstructed or newly-built instruments and raw materials collected from the landscape … followed by reconstruction of the acoustic environments of the monuments’ (2009: 9). Footnote 9

7. Stones make the mind

In my own work drawing on archaeoacoustics, I am not attempting to recreate Neolithic soundscapes. My intention is to engage with the ephemeral qualities of archaeological record as a metaphor for the metaphysical imaginary. As Thomas writes, the archaeological artefact, such as a stone, is not simply an object but also ‘a thing to think with’ (1991: 184). By extension, perhaps we could consider that the stone is also a thing to listen with, which has many interesting applications for improvisation. My improvisations using this material reach back in cultural time while also pulling an artefact of time (the stone) into the electroacoustic present. The use of stones allows me to reach across cultures without feeling restricted by idiomatic or non-idiomatic concerns; unlike my instrument, a stone does not have cultural baggage, yet is literally a grounding material. Exploring the metaphysical imaginary is also a grounding metaphor for improvisation and it allows me to set an intentionality that is spiritual in nature. This spirituality could be encapsulated in the idea that sound can be harnessed for transcendent purposes. There are also parallels between the metaphysical qualities of Neolithic rituals and electroacoustic music as some of the examples discussed previously. In the electronic world, sounds are treated at a metaphysical remove from our everyday existence. In the pre-historic world, acoustic sounds from nature were often heard as the voices of spirits or ancestors. Both ways of hearing draw upon a metaphysical imaginary, that core need for heightened experience, transcendence or the supersensible.

My improvisation drawing on archaeoacoustics is entitled Stone makes the mind. The piece uses ‘physical’ stones as a catalyst for mindful improvisation and electronically re-imagines the resonant qualities of the Newgrange stone tomb. Tomlinson suggests that the objects humans use to make art shape our consciousness. In a Neolithic framework, he argues that ‘stone makes the mind’ (2015: 276). Likewise, interpolating a pre-modern musical framework for improvisation in electroacoustic music also shapes aesthetic thought in interesting ways. In Neolithic times, instruments and tools such as stones were ‘used to break open bone to access marrow’ (Coward and Gamble Reference Coward, Gamble, Malafouris and Renfrew2010: 50). In my music, utilising the stones is a way to try and ‘break open’ my approach to improvisation; it is an attempt to access the ‘marrow’ or synchronic–diachronic dimension of my own playing through an imagined metaphysical framework. In this improvisation, I use several stones of personal significance as the catalyst for extended technique using the sarode. The acoustic material is digitally treated through a MIDI pad running various ChucK codes. These patches are generated randomly and feature a variety of processes such as granular synthesis, pitch shifting, delays, arhythmic loops and heavily gated filters.

My second improvisational strategy involved exploring the reverb properties of the inner chamber of Newgrange. Inspired by the work of previous scholars, I was given permission to make my own audio recordings of the inner chamber. First, these recordings afforded me the opportunity to have a physical sense of how sound feels inside the monument. Second, I was able to use the recordings to create my own convolution reverb that replicated the resonance of the passage. Extrapolating on Jahn’s ideas about the ‘interactive resonances of the three sub-chambers’ (Jahn et al.Reference Jahn, Devereux and Ibison1995: 10), I experimented with feedback using an internal microphone in the sarode and three different versions of constructed digital reverb of the Newgrange chamber. The improvisational element was manipulation and attempted control of the pitch, timbre and volume of the feedback (Sound example 2).

My performance approach for this piece draws on Indian classical music in the way I emotionally conduct myself. Similar to the first of Jin Hi Kim’s aforementioned ‘eight parameters’, my first step in this improvisation is an emptying of the mind. To assist in this important preparatory step, and drawing on my experience with Indian classical music, I say a small blessing when I pick up the instrument and internally acknowledge my teachers. However, in this piece my understanding of who my teachers are is expanded to include a diachronic dimension, reaching back to Ireland’s pre-historic inhabitants and their relationship to the organic and supersensible world. In a way, the stones are a kind of ritualised offering to the instrument and an invitation to explore new sonic matter. The stones also offer a counterbalance to technology, particularly the presence of a computer. Rather than looking at a screen, this improvisation starts with turning my attention to nature, the energy of my body in relation to the tactile moment. Using organic materials (such as a stone) brings me back to my feeling body and helps to still thought processes. The act of picking up the stones is a chance for meditative reflection on the material itself. I am reminded of the history and provenance of the stones and become attuned to their physicality. The tactile engagement of a stone in my hand, its texture, shape, temperature, composition, all bring me back to a sensual being-in-the-world. This also positions the improvisation beyond the construction of culture as a simple embodied act of presence. To paraphrase Tomlinson, the stone offers not just a ‘cognitive anchor’ but also a sensual, embodied reference which allows for greater flights of the metaphysical imaginary.

8. Listening Back and Listening Forward

Stones make the mind demonstrates my exploration of the metaphysical imaginary as a metaphor for electroacoustic improvisation, as a matter of imaginative rationality that I hope may be of use for other artists. More broadly, I would also like to offer the metaphysical imaginary as meditation on discovering what is most meaningful and potent in our lives, for the imaginary is a powerful tool of revolution and potential change. As Kristeva writes, there are ‘rebellious potentialities that the imaginary might resuscitate in our innermost depths’ (2002: 13). This brings into question the role of the artist on the margins of or in between cultures as provocateur or seer, in which insight is gained through transcendent experience. Perhaps the world of archaeoacoustics and the metaphysical imaginary have the potential to inspire other improvisers to listen both backwards and across cultured time and see what sounds and selves it may help bring forward.