I. Introduction

Around 330 BC in a port on the northern Black Sea, a Greek speaker named Oreos composed a letter to Pythokles, his business associate. Oreos conveyed greetings, then turned to pressing business: Pythokles is to send a himation for Oreos’ personal use, and two Ionian himatia to sell for profit. Along with the clothing, Pythokles must take a slave named Charios and deliver him to Diodoros the helmsman for transport by ship. Oreos bids Pythokles farewell, and begins a second message to a man named Kerkion: space is available on Diodoros’ boat, he writes, for saltfish.

Of the merchant Oreos, his associates Pythokles and Kerkion, the enslaved Charios and Diodoros the helmsman, nothing more is known: we have only this snapshot of their lives, preserved on a thin lead tablet from Myrmekion, an ancient port city of Crimea’s Bosporan Kingdom (Fig. 1).Footnote 1 Yet we know of other persons like them, other slaves and other helmsmen, from this same region. Consider a contemporary lead tablet that emerged in the necropolis of Pantikapaion, some 4 km southwest of Myrmekion. This second text curses a helmsman named Neumenios and the slaves of Xenomenes, all of whom were implicated in a trial in the law courts.Footnote 2 Studied together, these tablets provide a glimpse of social and economic life in a small corner of the Bosporan Kingdom, a seascape teeming with traders and slaves, with luxury textiles, fish and ships. Here are the organized merchants, adept at record keeping and letter writing, if colloquial in speech; here, too, the wives of merchants, the helmsmen and the enslaved persons trafficked as human cargo.

Fig. 1. The Black Sea.

This article investigates the ways in which early literacy was thoroughly entwined with commerce in Greek communities of the northern Black Sea from the sixth through fourth centuries BC. Analysing different genres of documentary text, especially mercantile letters and curse tablets, it is possible to reconstruct the broader economic and social networks of individuals engaged in commerce in Pontic cities. Not only was literacy driven by commerce, but literacy and commerce are shown to have been very much interwoven, and to have developed in parallel with one another and with civic and social institutions within these port communities. Inscribed letters, commercial texts and curses document similar groups of individuals, persons who often slip through the cracks of historical sources and figure minimally in discussions of regional economies and literacy. Especially in the northern Black Sea, where these texts provide a sizeable data set and illuminate mercantile communities, social and economic histories have much to gain from placing these documents in dialogue with one another. This article demonstrates how regional trade could drive written literacy in non-elite circles of the northern Black Sea, and surely within other Greek settlements whose economies were grounded in commerce.

These arguments are advanced in three parts. First, the state of the evidence is assessed and current research introduced, including recent textual editions, forthcoming projects and reports of unpublished inscriptions. Second, the study calls for north Pontic letters and receipts to be analysed together with curse tablets; these regional corpora engage the same groups of individuals, and illuminate a particular social world grounded in commerce. Indeed, Shelomo Goitein noted over 50 years ago that ‘social and economic history, especially of the middle and lower classes, can hardly be studied without the aid of documents such as letters, deeds, or accounts that actually emanated from people belonging to these classes’.Footnote 3 Growing numbers of lead and ceramic inscriptions from the northern Black Sea help fill these historical lacunae, casting light upon the persons from whom they emanated and populating communities on the edges of the Greek oikoumenē. Finally, this article uses these texts to assess literacy and epigraphic habits in non-elite circles, with a focus on traditions of so-called mercantile literacy. These inscriptions document communities of striking economic sophistication, where commerce connected Greeks to other Greek and non-Greek persons across the Black Sea and beyond. Merchants and members of their households (wives, children, slaves) inhabited a world in which written communication was deeply beneficial, if not required, for regional and long-distance commerce.

II. Private letters and correspondence

In the diverse communities of the northern Black Sea, network dynamics galvanized connectivity and interactions of various kinds, from commerce to marriage. A Pontic ‘cultural koinē’ has been identified as emerging from these interconnections, and the exchanges captured in letters, curses, receipts and other commercial documents (see, for example, the slave tag of Phaulles below) bear witness to social and economic life in these frontier apoikiai. Footnote 4 The majority of published documentary texts from the Black Sea littoral come from the northern coast, an area that for our purposes encompassed the Greek cities between Histria (Istros) in the west and Gorgippia in the east, including those of the Bosporan Kingdom in eastern Crimea and on the Taman Peninsula (Fig. 1). At the time of writing, some 36 commercial letters dating from 550–300 BC are known from this stretch of coast. The total number is surely higher than this, however; the proliferation in recent years of metal-detector wielding ‘treasure hunters’ has catalysed the illicit removal of many lead tablets, most of which are neither reported nor published.Footnote 5 These texts document communications along local, regional and long-distance networks; most include orders, instructions and pleas for intervention between two or more persons. Commercial conflicts are well represented in these texts, several of which describe the transport and seizure of commodities, both persons and goods. One of the oldest such letters comes from the island of Berezan (ancient Borysthenes, ca. 530 BC) and claims that the sender himself has been wrongfully seized and enslaved by a certain Mατασυς, a man with a non-Greek name seemingly embroiled in a feud with the letter’s addressee.Footnote 6 Written in the present tense throughout, the text conveys urgency in pressing the recipients to clarify the sender’s status: Achillodoros is a free man, not a slave, and accordingly not liable to confiscation:Footnote 7

Exterior:

Achillodoros’ lead, to his son and Anaxagoras.

Interior:

Protagoras, your father sends instructions to you: He is being wronged by Matasus, for he is enslaving him (δολο͂ται) and has deprived him of his cargo. Go to Anaxagoras and tell him the story, for he [Matasus] says that he [Achillodoros] is the slave of Anaxagoras, claiming: ‘Anaxagoras has my property, slaves, both male and female, and houses’. But he [Achillodoros] disputes it and denies that there is anything between him and Matasus and says that he is free and that there is nothing between him and Matasus. But what there is between him and Anaxagoras, they alone know. Tell this to Anaxagoras and his wife. Besides, he sends you these other instructions: take [your] mother and brothers, who are among the Arbinatai, to the city. Euneoros himself, having come to him, will go down to Thyora.

Inscribed on lead, the text suggests that Matasus’ distressing seizure of Achillodoros, the letter’s composer, was retaliatory. At some prior time, Matasus’ own property, male and female slaves and houses (δόλος καὶ δόλας κοἰκίας), had been seized by Anaxagoras. Matasus apparently thought that Achillodoros was a slave of Anaxagoras, a confusion which perhaps stemmed from the fact that Achillodoros’ family, if not Achillodoros himself, resided in the hinterland among the Ἀρβιναται, a regional indigenous group. Achillodoros’ letter documents both the prominence and precariousness of north Pontic commerce, in addition to the private forms of redress adopted by merchants embroiled in commercial disputes in the late sixth century. Enslaved persons, estates, moveable property and even free merchants could be seized without warning, in this case in response to a previous seizure of goods and property, part of an extrajudicial undertaking known as sula/sulē (reprisal by seizure).Footnote 8

Other letters connected Greek merchants to agents in the field; such texts document the commodities, persons and payments implicated in north Pontic commerce. Thus, in a letter from Patraeus (Patrasys), Pistos asks a merchant named Aristonymos to exact a gold stater and slave (ἀνδράποδον) from a (Thracian?) man named Σαπασις, while another from Gorgippia orders that an axe (πέλϵκος) be given to a slave in connection with agricultural work.Footnote 9 A lead letter from the Olbian hinterland directs a horse to be delivered from the chōra to the letter’s sender in the astu; already the horse had been given to Zopyrion by one Kophanas, to whom τὰ γράμματα, some sort of written documents, were then to be given.Footnote 10 In a text from sixth-century Olbia, Apatourios tells Leanax that the total value of goods seized, at least some of which included enslaved persons, is 27 staters; he implores Leanax to send records (διφθέρια) in order to save the cargo.Footnote 11 An ostrakon recently found in Nikonion is addressed ‘to those at home’ by a man named Dionysios; it communicates information concerning the emptying of sand out of a boat, large quantities of barley (nine medimnoi) in the keeping of one Possikrates and the procurement (κ[ό]μισαι) of a half-stater from the Thoapsoi (παρὰ τῶν Θοαψων), seemingly an indigenous inland group, in exchange for a himation. Strikingly, editors point out that once the letter switches to the singular (from ll. 2–3), its primary addressee is female.Footnote 12

Additional examples can be brought to bear, but the picture is clear enough: this private correspondence documents business dealings with fine-grained detail: the exchange of goods in money and kind, the movement of persons and property, the dissemination of registers and receipts. It reveals the centrality of written text in commercial ventures, by individuals who might be called traders or merchants. At minimum, these letters required a basic degree of literacy to compose and to read; they suggest that already by the sixth century, some north Pontic traders and those in their circles (wives, children, enslaved persons, field agents) were indeed literate, and reliant upon written communication for their commercial ventures.

These letters are also striking in terms of their form. Many contain language unique to the epistolary genre, such as the application of χαίρϵιν in greeting.Footnote 13 So opens a fourth-century letter from Olbia, in which one Artikon sends greetings to those at home: Ἀρτικῶν τοῖς ἐν οἴκωι χαίρϵιν. Dionysios writes similarly from Nikonion, as noted above: Διονύσιος τοῖς ἐν οἴκω[ι] χαίρϵιν.Footnote 14 These messages contain both prescript and clause, with the body of text expressed in the first person. Such letters might include the sender’s name in the nominative with recipient(s) in the dative, as in the letter of Achillodoros (Ἀχιλλοδώρō τὸ μολίβδιον παρὰ τόμ παῖδα κἀναξαγόρην), or employ ὑγιαίϵιν as a formula valetudinis or ἔρρωσο in a formula valedicendi.Footnote 15 Letters from the sixth and fifth century often exhibit only some of these features but, over time, more formal elements were included as literacy spread and the genre became standardized.

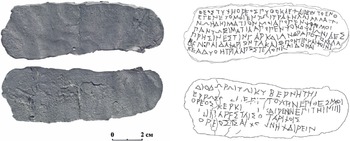

Let us look in detail at one such letter, and the light it sheds on economic and social histories of the northern Black Sea, especially the Bosporan Kingdom: the self-declared letter (ἐπιστολήν) of Oreos with which the article opened.Footnote 16 The tablet was recovered in 2017 in the Crimean port city of Myrmekion; it emerged beneath the wall of a later villa alongside ceramic sherds, animal bones and deer antlers in a context dating from 330–320 BC. The letter was found unrolled and open, suggesting that it had been read in antiquity.Footnote 17 I provide the edited Greek text in full, as subsequent discussion draws heavily upon the language therein (Fig. 2):Footnote 18

Fig. 2. Lead letter of Oreos from Myrmekion: Dana 2021, no. 46. Tablet once kept in the Eastern Crimean Historical and Cultural Museum-Preserve, KM 191604, Inv. 8706. Drawing and photograph courtesy of M. Dana, with kind permission.

God! Fortune! Oreos sends greetings to Pythokles. I had a problem with my neck then, but now I can open my mouth. Send me a himation for my personal use, and above all send me two Ionian himatia for sale. There is also a slave to take: the boy Charios; [take] these [goods] and the Pontic one (i.e. the slave) and two or three purple textiles, and give them to Diodoros the helmsman. Farewell! Dispatch the following letter for me. Oreos sends greetings to Kerkion. On the ship [---] is present for you (space) for saltfish. Oreos sends greetings to Saicho[-]ine (?).

Much is remarkable about this tablet, but in many ways the text is also representative of the wider corpus of north Pontic epistles. As the editors note, the Θϵός Τύχη heading drew upon inscriptions in the public realm; the formula was common by this time in business correspondence (trade contracts, sales agreements) as it was in civic decrees and votive dedications.Footnote 19 Thereafter we find the formulaic language of epistolary genres of communication: the text is now one of the oldest documents to so employ it. Oreos’ letter demonstrates that a stable epistolary format was crystallizing by 330 BC, even in private correspondence with decentralized modes of circulation.Footnote 20 The text contains the following elements, all of which came in later centuries to exemplify classical genres of letter writing: (1) prescript and greeting formula, which included the name of the sender (nominative), the name of the recipient (dative) and χαίρϵιν as an expression of greeting, followed by (2) an account of Oreos’ health. Here the description is personal, tailored to describe a prior ailment that had since been resolved; such discursion would later be replaced by a formula valetudinis, often the stark ὑγιαίνϵιν. There was then (3) the primary message, issuing instructions for action, followed by (4) the formal closing, Ἔρρωσο.

Perhaps the most unique aspect of Oreos’ letter is that the text does not end after the first set of instructions for the assemblage of goods, nor even after the closing farewell. Rather, a second letter follows. Sharing the same support as the first, this second epistle begins with instructions to ‘transmit (this) letter for me’, and is intended for a new recipient, a man named Kerkion. It is probable that the letter’s first addressee, Pythokles, would have dispatched the object or its message to the second addressee, whose cargo was to join Pythokles’ on Diodoros’ ship. Pythokles and Kerkion were, after all, connected by way of both Oreos and Diodoros. Alternatively, the helmsman Diodoros may have been responsible for delivering the second message or the tablet itself to Kerkion; Diodoros was a common denominator between the two men, and would have interacted with both as his ship carried goods from each. The final line of text on side B carries no instructions whatsoever, only a greeting to a woman whose non-Greek name may have been Saichoine or something similar.Footnote 21 Quite possibly this person had connections with indigenous groups of the Crimean interior, but resided with Kerkion as wife, mother, child or commercial liaison. Oreos undoubtedly knew her well enough to greet her by name, and this direct form of address may suggest that she was a relative (it would otherwise be unusual for a man to mention the name of an unrelated woman in this context). At least one other Pontic letter refers to the wife of the addressee, though not so directly as here with χαίρϵιν.Footnote 22 The final line suggests that Oreos was dealing with familiar people; these were cordial business relations, agents with whom Oreos had previously and amiably worked, possibly even relatives.

Oreos’ letter thus circulated to several individuals, all within his network and probably based in or near Myrmekion. The individuals to whom the letter was addressed were meant to contribute cargo to Diodoros’ ship; it is unclear whether they were paid up front or after the final sale of the products. Oreos was an organized, meticulous merchant who operated with considerable foresight in his transactions. He knew the order in which individuals had to be contacted, and the letter’s route of circulation from one agent (Pythokles) to the next (Kerkion). He took care to specify commodities with precision (the number, colour and style of himatia,Footnote 23 the ἀνδράποτον named Charios), and knew just how these goods would fit in Diodoros’ ship. Here was a merchant adept at communication between different persons and workshops, and who was fluent in the contours of epistle writing, as required by the nature of his work. Within the parameters of a loosely fixed genre, Oreos wrote clearly but colloquially, in phrases drawn from everyday speech (for example, τὸ ἔνθ’ ἐγένϵτό μοι ἐν τῶι τραχήλωι). The spelling of some terms was confused, with additional letters inserted (ἀπόπϵνψ<ι>ον, πάντω<ι>ς, χαίρϵ<ν>ιν) or words needlessly repeated (μοι ἀπόπϵνψόν μοι), but the text nonetheless displays familiarity and facility with written communication. The object reminds us that ancient literacy, or literacies, might best be framed along a spectrum, with individuals not necessarily ‘all in’ or otherwise illiterate.Footnote 24 Oreos’ letter also demonstrates the ways in which commerce drove written literacy in mercantile circles, propelled by communications with kin, field agents, fishermen, craftspersons, helmsmen and artisans over time and space.

III. Trades and industry in north Pontic letters

Oreos’ letter sheds precious light on the world of north Pontic merchants, individuals who procured and shipped commodities over sizeable distances, and whose professions demanded proficiency in written correspondence. Of great value to the historian, this document also illuminates the cargo of one Greek trading vessel that plied the busy straits between the Sea of Azov and the Black Sea during the fourth century BC. Here Oreos asks Pythokles to prepare several items for shipment, including textiles, a slave and saltfish; the object’s archaeological context also sheds light on the presence in Myrmekion of a bone-carving workshop, the site in which the letter ultimately ended its journey. Many of these commodities appear elsewhere in regional correspondence and, in the case of helmsmen and enslaved persons, also in curse tablets. The prominence of these goods yields data on the workings of local economies in the fourth-century Bosporan Kingdom.

i. Textiles

Prominent in Oreos’ letter are high-end textiles, if in small quantities. Three himatia or ‘cloaks’ are requested, two of which are distinguished as ‘Ionian’ in style and destined for sale; the ‘two or three’ φοινίκϵα mentioned in lines 6–7, mantles coloured with purple dye, surely refer back to these himatia. References to himatia and additional items of clothing emerge in other regional letters, including a contemporary missive from Nikonion in which a himation is recorded as being used in a monetary deposit or exchange.Footnote 25 If these items were indeed manufactured in the region, rather than imported, they may point to a little-known Pontic export which has left no trace in the archaeological record: textiles. Textiles were a form of wealth in Archaic and Classical Greece, and raw wool or flax may have come from the chōra of a Crimean polis like Myrmekion. Excavations at Myrmekion and neighbouring Pantikapaion have yielded numerous loom weights, confirming the presence of textile production within these coastal settlements (namely, the weaving of spun thread into clothing and various other textiles, which could have included, for example, sails).Footnote 26

ii. Enslaved persons

Dozens of enslaved persons like the boy Charios are documented in the regional corpus of commercial letters, as the Black Sea was an active feeder of the slave trade by the sixth century BC. Indeed, Polybius would later write that the magnitude of persons enslaved in the region exceeded that of anywhere else (4.38.4–5).Footnote 27 Much of the regional traffic in slaves, perhaps including Charios’ own journey,Footnote 28 would have begun in the steppes of the Scythian interior. From there, enslaved persons were transported down major river systems (in Scythia, the Bug and Dnieper; in Thrace, the Ister/Danube) to settlements on the Pontic coast. Berezan and Olbia were particularly well situated to collect these riverine cargoes, with upstream sites of intense slave trading directly linked to these coastal cities.Footnote 29 From such intermediary ports, enslaved persons were trafficked to other parts of the Black Sea, including the cities of the Bosporan Kingdom. A lead tablet from ca. 500 BC, possibly a slave tag, documents part of this passage.Footnote 30 Recovered just across the straits from Myrmekion in the city of Phanagoria, the tablet records the sale of a man named Φαύλλης in Borysthenes (Berezan), and his subsequent journey in captivity across the north Pontic coast to the Taman Peninsula:

This slave here has been sold out of Borysthenes, his name is Phaulles. We wish that everything … be returned.

Christopher Parmenter has argued that the majority of persons enslaved in the north Pontic region were, like Φαύλλης, ‘more likely than not to remain in the Pontus’.Footnote 31 Indeed, the northern Black Sea is portrayed by classical writers as teeming with slaves, and Oreos’ letter adds to a sizeable body of documentary evidence supporting such claims, while giving a name to one such individual. It is unknown where Charios’ journey ended, but his captivity aboard Diodoros’ ship, trafficked as another man’s cargo, herded (ἀνδράποτον) alongside fine clothing and saltfish, is surely representative of other such passages along the Pontic coast.

iii. Saltfish

As noted above, Oreos’ letter carries a second message with an additional addressee: a very uncommon feature of ancient Greek letters. After Pythokles’ instructions concerning the himatia and Charios, Oreos greets someone named Kerkion and informs him of the availability of space on (presumably) Diodoros’ ship for dried salted fish. Dried saltfish was another popular north Pontic export, with at least one other regional letterFootnote 32 referring to τάριχος: ‘Apatourios to Neomenios: bring home the saltfish’. The northern Black Sea and Sea of Azov were important regions of saltfish production and export during the Classical period; recycled amphoras and large crates or baskets known as σαργάναι were used for the maritime transport of tarichos, and Kerkion’s shipment may also have been layered in such containers.Footnote 33 Various species were associated with the northern Black Sea, including the anchovy (which could comprise up to 80 per cent of commercial catches in the Sea of Azov), mackerel, mullets, sprats and shads; these were sold according to the degree of salt preservation: lightly salted, semi-salted, etc.Footnote 34 Myrmekion and other cities of the Bosporan Kingdom controlled some of the most productive fisheries in the Greek oikoumenē. Ephraim LytleFootnote 35 has suggested that fishing rights within these waters were subject to leasing agreements, the purchase of which would have required considerable expenditures of capital. Great quantities of fish bones dating from the sixth through first centuries BC have emerged in excavations of Myrmekion, in significantly higher percentages than found in other Bosporan cities; this suggests that Myrmekion was an especially popular site for the docking and unloading of fishing boats, and the processing, consumption and export of fish.Footnote 36 Trade with the Hellenized coast of the northern Black Sea, especially the Bosporan Kingdom, fuelled the demand for saltfish in Athens and other major urban centres (Miletus, Hellespontine cities), and brought great wealth to the Pontic merchants who facilitated these commercial undertakings, some of whom were Scythian elites.Footnote 37 It is against this backdrop that Kerkion’s saltfish joined the cargo of Diodoros’ ship, which was but one of many carrying saltfish, textiles, enslaved and free persons, and, of course, large quantities of grain by the fourth century BC.Footnote 38

Two or three himatia, one enslaved boy and an unspecified quantity of saltfish: apart from the fish, the quantity of goods exported by Oreos in Diodoros’ ship was fairly small. Writing from elsewhere, Oreos knew the venders operating at Myrmekion, in addition to the markets at which Pythokles’ textiles were to be sold. He was also aware of the availability of space on Diodoros’ ship for different types of cargo, some of which was small and easily portable but costly (fine textiles, Charios), while others would have been bulkier, smellier and cheaper (saltfish). The careful recording of such information, from registries of trade goods to the agents to whom they were entrusted, is representative of the type of highly functional, mercantile literacy possessed by Oreos and surely other traders in the region.

iv. Bone working

The context in which the letter emerged sheds further light on its circulation in ancient Myrmekion. The object was recovered in a large pit alongside 17 ‘bone artefacts with traces of handiwork’, including a rounded pyxis lid. The deposit included bone and antler fragments with evidence of ‘carving, sawing, and lathing’; this assemblage marks the largest cache of bone-carving waste known to date from Myrmekion, and both the quantity and quality of the worked bone suggests the presence of a bone-carving workshop.Footnote 39 Such an atelier could produce small prestige items like statuettes, furniture pieces, combs, weaving implements (needles, spindles), jewellery, musical instruments, fibulae (dress pins) and clothing ornaments, in addition to pyxides. Another such workshop is known from Tyras, pointing to the presence of craftsmen specialized in bone carving across the north Pontic littoral.Footnote 40 The inflow of raw materials from the Pontic interior, combined with a high degree of regional and long-distance trade, would have incentivized the concentration of such artisans within these port communities. Oreos’ letter appears to have ended its journey in the hands of someone affiliated with fine bone working; possibly Pythokles, Kerkion, Saichoine or even Diodoros bore some connection to this workshop or its products.

Oreos’ letter provides a glimpse of vibrant commercial life in fourth-century Myrmekion, documenting the commodities and persons that drove regional trade and brought wealth to these bustling port cities, from bone-carving workshops to textile production to the sale of fish and enslaved persons. The tablet also demonstrates how a documentary text can shed new light on local social and economic histories, while raising broader questions about the nature and significance of the epistolary genre itself in the northern Black Sea. Beginning in the sixth century BC, communications like that of Oreos were not uncommon in this part of the Greek world: far from it. The recovery of some 36 letters from this region is significant, and exceeds that of all other areas; in fact, more letters are known from Berezan and Olbia during these years than from all of Attica, despite Attica’s greater size and population, and the fact that Attica benefits from a higher degree of systematic excavation (not to mention a robust epigraphic habit). Footnote 41 What conclusions might be drawn from these data? Were Greek speakers of the northern Black Sea exceptionally literate, or particularly prone to committing their communications to writing? At least one clue lies in the fact that this region hosted high levels of local, regional and long-distance trade. Merchants needed to communicate with field agents, business associates, helmsmen and family members, sometimes over great distances, with regard to dealings that often required substantial capital investment;Footnote 42 such persons required, and were capable of, strikingly precise communication, record keeping and commercial organization, and their professions were well served by the technology of writing. The robustness of local (inland agricultural, pastoral, maritime), regional and long-distance commerce, combined with the density of Greek port cities along the north Pontic coast, helps account for the abundance of regional letters. Indeed, these documents were the means through which trade could occur.

Furthermore, sailing in general was risky in the ancient world, and seaborne commerce especially so. Trade in goods like grain or saltfish not only exposed merchants to the uncertainties of shipping over great distances, but also the volatility of seasonal harvests and catch variability.Footnote 43 Written communications conveyed information precisely, and could reach persons and places that the sender himself could not. In multilingual communities like Myrmekion, a fixed text might be consulted multiple times by different individuals in separate locations, as the letter of Oreos neatly demonstrates. Written text also created accountability for those to whom such messages were delivered, and served as proof of transaction; in Demosthenes’ Against Phormio, for example, Phormio is accused of intentionally withholding ἐπιστολάς entrusted to Chrysippos’ slave and business associate in the Bosporan Kingdom (34.8). Again, written communication and commerce were very much interwoven for Greeks in Pontic frontier cities.

IV. North Pontic curse tablets

Let us now turn to a second group of private texts that were committed to lead and ceramic media in the northern Black Sea: curse tablets. By the fourth century BC, Pontic curse tablets also illuminate a world populated by merchants, helmsmen and slaves, providing another body of texts through which regional histories (or microhistories) might be advanced. Whereas the oldest Pontic letters emerge around 550 BC, the earliest curse tablets appear soon after 400 BC, but in higher volumes: the poleis between Istros and Gorgippia have yielded some 75–80 inscribed curses.Footnote 44 This estimate is derived from combining curse tablets from regional corpora with recent ‘one-off’ publications from Pontic sites, and then factoring in tablets that have been unearthed but not yet unrolled or published, and curse tablets that are known to have been illicitly removed by metal detectors from north Pontic sites.Footnote 45 Of this loose corpus of curses, most date from the fourth century BC.

The majority of Pontic curse tablets with recorded provenience come from graves;Footnote 46 at least four fourth-century Olbian curses (both inscribed lead tablets and a painted ceramic lid) have also emerged in a shrine or cult site located at the edge of the necropolis,Footnote 47 suggesting that depositional practices in the Black Sea mirrored those of other Greek poleis. All tablets for which the circumstances of composition are known are judicial in nature, occasioned by trials or legal disputes. These texts illuminate the regional importance of law courts, robust institutions about which little is otherwise known, and reveal that in the northern Black Sea, curse tablets found first (and frequent) use in litigation contexts. This is unsurprising, as the needs of the commercial port encouraged not only the development of written documentation, demonstrated by the abundance of north Pontic letters, but also judicial institutions, required to regulate commerce and adjudicate the conflicts that arose from regional trade and industry. The violent and costly methods of pursuing private redress in the mid-sixth century, evident in the extrajudicial seizure of Achillodoros,Footnote 48 for example, must have driven the development of centralized legal institutions within these commercial havens during the fifth and fourth centuries BC. The region’s many judicial curse tablets probably reflect this evolution, and the prominence of litigation in daily life. Consider, for example, one of the oldest Pontic curses, unearthed in the necropolis of Olbia in 1912. Inscribed on ceramic, the early fourth-century text ‘bind[s] down the tongues of the court opponents and witnesses’, καταδέω γλώσσας ἀντιδίκων καὶ μαρτύρων (DefOlb 18 = IGDOlbia 105). A slightly later lead curse from Olbia carries a list of nominative names on one side and, on the other, seemingly targets μ[αρτυρίας καὶ δί]κας (DefOlb 17 = IGDOlbia 107). Curse-writing rituals were used in these Pontic cities by Greek speakers in legal contexts, markers of ‘Greekness’ employed in quintessentially Greek institutions, the law courts.

Finally, while the majority of north Pontic curse tablets were inscribed on lead, several were written on terracotta sherds and bowls; this mirrors broader epigraphic preferences in the region, attested in the corpus of commercial correspondences (many of which were also incised on ceramic).Footnote 49 The fact that individuals were committing private text to lead as early as the mid-sixth century demonstrates that written literacy and social conventions for incising text (that is, a form of epigraphic preference) were established for well over a century when curse practice first emerged in the region.Footnote 50 This helps to explain why ritualized cursing took root so seamlessly across the northern Black Sea, becoming widespread by the fourth century. Many Pontic Greeks, especially persons involved in commerce, possessed some degree of written literacy, and were long accustomed to writing private texts on lead and ceramic objects.

Of the 75–80 curse tablets known from the northern coast of the Black Sea, the majority, some 36–40 inscriptions, come from the city and chōra of Olbia. Founded by Milesian settlers on the southern coast of modern Ukraine, Olbia has also yielded the region’s oldest curse tablets, which date from the early fourth century BC. While such claims to age and corpus size may reflect nothing more than Olbia’s long history of excavation relative to other Pontic sites, it is clear that Olbia was particularly abreast of cultural trends in the broader Greek world, from Orphic rites to didactic exercises in the Ilias parua (the latter may preserve the oldest recorded version of a circulating literary text, composed by a schoolboy, no less).Footnote 51 Alexey Belousov’s new edition of Olbian defixiones (DefOlb) includes 25 curse inscriptions, all of which were previously published; the majority of these comprise lists of names (12 curses) and elaborations thereon. Another early Olbian curse is DefOlb 14 (IGDOlbia 101), composed soon after 400 BC. The text was incised on a rectangular lead sheet, folded once and deposited in a grave in Olbia’s necropolis:Footnote 52

Eoboulos son of Moiragores, Dorieos son of Nymphodoros, Apollonides son of Timotheos, Apatοurios son of Hypanichos, Ietrodoros the son of Hekatokles and all those who go along with him [Eoboulos].

This Olbian curse carries a list of five male names in the nominative, all of which are accompanied by a patronymic; most of these individuals bear characteristically Ionian names (Mοιραγόρϵς, Ἀπατο̄̄ριος, Ἰητρόδωρος, Ἑκατοκλέος).Footnote 53 The judicial nature of the curse is revealed by the concluding phrase τὸς αὀτῶι συνιόντας πάντας, ‘and all those who go along with him’. The precise meaning of συνιέναι is unclear, but probably signifies the supporters and witnesses of the opposing litigant at trial.Footnote 54 The phrase finds a parallel in a contemporary judicial curse from Histria, which registers a group of men with patronymics, and then proceeds to curse those ‘going together with Diogenes’, καὶ τῶν συνϵπιόντων μϵτὰ Διογένϵ[ος], surely Diogenes’ witnesses, co-advocates and supporters at trial.Footnote 55 The presence of συνϵπιόντων and συνιόντας in these two curses probably captures a regional colloquialism, used in reference to one’s law court entourage. As observed in the letter of Oreos, mercantile groups could adopt and spread colloquial language, and texts composed by such persons often exhibit cross-linguistic features like idioms and use of the vernacular.

The world of north Pontic merchants is again illuminated in a fourth-century curse tablet from the necropolis of Pantikapaion, another Milesian apoikia sited just 4 km southwest of Myrmekion:Footnote 56

A

Col. I: I bury down (κατορύσσω) Neumenios, and Demarchos, and Charixenos, and Moirikon, and Neumenios the helmsman, and Aristarchos in the presence of Hermes Chthonios and Hekate Chthonia, and in the presence of Pluto Chthonios and Leukothea Chthonia, and in the presence of Persephone Chthonia, and in the presence of Artemis Strophaia.

Col. II: Also in the presence of Demeter Chthonia and the Chthonic Heroes: May none of these gods release (this curse), nor the daimones, not even if Maietas asks this as a favour, nor if they set up (offerings of) thigh bones!

Col. III: ------------------------

B

Col. I: I bury down Xenomenes, and the works of Xenomenes, and the slaves of Xenomenes, near Hermes Chthonios, and in the presence of Hermes Chthonios, and in the presence of Ploutodotos Chthonios, in the presence of Praxidika Chthonia, and in the presence of Persephone Chthonia. From these gods let there be no release for Xenomenes, not for him, nor for his children, nor for his wife.

Col. II: … in the presence of the Chthonic Heroes and Demeter Chthonia

Col. III: ------------------------

Like the letter of Oreos, this tablet captures a vignette of social and commercial relations in the Bosporan Kingdom during the fourth century BC. Though Pantikapaion was a Milesian (Ionian) colony, the text exhibits some Doric features (Ἑρμᾶν, Ἑκάτα[ν], A.I.5). That a bustling port like Pantikapaion hosted Greek speakers of different dialects is not surprising; nor is the presence of a helmsmen like Neumenios unexpected in this seaside city. In addition to a ship’s captain, the reference to the slaves of Xenomenes (B.I.3) suggests that this curse concerned commercial matters, probably maritime trade and the property at stake in the cargo, much like Oreos’ letter, though from a different perspective. Conflict grounded in maritime commerce would explain the cursing of the helmsman Neumenios, in addition to the works and slaves of Xenomenes; it could also contextualize the invocation of the sea goddess Leukothea, a popular deity in the port cities of the Black Sea.Footnote 57 The presence of the goddess who aided sailors in distress in a text citing a helmsman and slaves, deposited in the commercial hub of Pantikapaion, suggests a conflict based in shipping and the transport of cargo. Greek law played a role in enslaving persons in the northern Black Sea, with law courts regulating (and legitimizing) the processes through which the slave trade could operate.Footnote 58 Commercial conflicts involving enslaved persons and other sea-bound cargoes would have been adjudicated in the law courts, important social and administrative institutions in these outlying Greek communities. Commercial transactions, especially those involving lucrative cargoes, could give rise to conflict over ownership claims, debts and seizures of property. Clashes such as these are captured over the centuries in private letters from the northern Black Sea and, as the above curse suggests, could often result in trial in the law courts. I suspect that the prominent place of trade in north Pontic cities, and the role of the law courts in adjudicating commercial disputes by the early fourth century, helps account for the region’s many judicial curses, as it does for the abundance of private letters, and that many curse tablets stemmed from commercial conflicts in the courts. SGD 170, discussed above, is one discursive example.

V. Documentary texts and microhistories

As scholars have previously noted, several formal elements of commercial letters and curse tablets invite comparison.Footnote 59 Both were inscribed on lead and ceramic supports; both document exchanges between private individuals and request services. Both follow genre-determined formats, whether prescripts and formalized greetings in letters, or the binding down of tongues in curses. The prominence of kin groups in both corpora also reveals the centrality of the family to trade and exchange in these communities. Furthermore, these texts exhibit parallels in terms of composition and emotional content: many were written in moments of perceived crisis, as noted by Esther Eidinow and Claire Taylor.Footnote 60

Yet more can be done with these corpora in terms of fine-grained regional histories, from the study of onomastics to legal institutions, especially in the northern Black Sea, where these documents provide a sizeable data set and feature non-elite groups (enslaved persons, helmsmen, women, merchants and individuals associated with non-Greek indigenous groups). The common themes that emerge can then be contextualized against broader historical backdrops, and used to emphasize the small group unit and how individuals functioned in the day-to-day, thus approaching a ‘microhistorical’ line of inquiry.Footnote 61 Indeed, recurring figures and themes emerge across the corpora, and the remainder of the article calls attention to four of these in turn: onomastics and prosopography, enslaved persons, local law courts and traditions of mercantile literacy. Several of these points were addressed in discussions above, but are here thematically engaged to show how the two corpora can advance regional histories of Pontic communities.

i. Onomastics and prosopography

With economies grounded in maritime trade and inland agriculture, the coastal communities of the northern Black Sea were sites of frequent interaction between Pontic Greeks, non-Pontic Greeks, Thracians, Scythians, Persians and other indigenous groups of the Euxine interior. Their kaleidoscopic relations are captured in Pontic letters and curses, as various persons with non-Greek names are shown in close proximity to ostensibly Greek individuals. Of course, ‘non-Greek’ names do not always signal non-Greek identity and cannot be understood to indicate the origins of their bearers (though sometimes, they surely did); often they do signal, at the very least, some sort of relationship with the designated group or place, however, and in this capacity document exchange and interaction between different communities in the northern Black Sea. Some such names may point to kin associations or ties of friendship, or, as names were regularly passed down within families, may commemorate a non-Greek father or grandfather, for example. We observed in the letter of Oreos how a woman with a non-Greek name was greeted in association with the saltfish exporter Kerkion; Marakates, too, is a person with a non-Greek name shown interacting with Greek speakers in the letter from Nikonion.Footnote 62 As noted above, one of the oldest Greek letters from Berezan documents the seizure of Achillodoros by a merchant with the Persian or Indo-Arian name Mατασυς.Footnote 63 Presumed by Matasus to have been the slave of another, Achillodoros’ own family lived (and perhaps identified) with the Arbinatai in the north Crimean interior; this was the indigenous group into which Achillodoros had apparently married, and with whom he interacted often. A fragmentary curse tablet purportedly from Pantikapaion may document interactions between Bosporan Greeks and Paphlagonians,Footnote 64 while a letter from Crimean Kerkinitis refers to a payment made to a community of the Scythian interior, a group with whom the letter’s sender and addressee must have had some contact.Footnote 65

Regional curse tablets also feature individuals with non-Greek names, the targeting of whom probably documents conflicts between Greek and non-Greek residents of the northern Black Sea. Three persons with probable Scythian names, Καφακης, Θατορακος and Aταης, are targeted alongside men with Greek names in a judicial curse tablet from fourth-century Olbia; all of the named victims, Greek and non-Greek alike, opposed the curse writer in a looming trial (DefOlb 15). Two curse tablets from the hinterland of Chersonesos target men with the Iranian names Αριακος and Αρσατης.Footnote 66 The proper name Mαιήτας, invoked in SGD 170, also has a local flavour, recalling the indigenous group east of the Bosporan straits on the Taman Peninsula, the Maïtai or Maiotai, who shared their name with the sea north of Pantikapaion (in antiquity, ἡ Mαιῶτις λίμνη). The Maïtai are frequently referred to in mid- to late fourth-century dedications from Pantikapaion, which suggests that persons identifying as Maiotian, or who were characterized in the community by interactions with Maiotian groups, formed a recognizable demographic presence within the polis.Footnote 67 Considered together, these inscriptions document the interaction and coexistence of Greek and non-Greek persons in cities across the north Pontic littoral. The presence of non-Greek individuals in cities like Olbia has long been known from literary sources (especially Herodotus 4), private votive dedications (the dedication of one Igdampaies to Hermes: SEG 30.909; the dedication of Anaperres, a non-Greek Scolotian, to Apollo the Healer: SEG 53.788), grave stelai (that of Leoxus, the son of Molpagoras, which depicts a youth clad in Scythian clothes on one side: SEG 41.619) and other forms of material culture.Footnote 68 At least some of the non-Greek names preserved in regional letters and curses reveal the interactions of these individuals with Greek speakers, and the sorts of activities that brought them together, from commerce to kinship to litigation.

Any inquiry into north Pontic communities would also benefit from a rich prosopography, driven by a wealth of epigraphic data. Prosopographical study of recurring names in private letters and curse tablets, especially when combined with other, contemporary epigraphical sources (votive dedications, grave stelai, graffiti, etc.), can advance understandings of interregional mobility and broader networks of communication. Consider for example the individual named Apatourios in a judicial curse from Olbia (Ἀπατο̄̄ριος Ὑπανίχō, DefOlb 14). In addition to the presence of an Apatourios in a second contemporary Olbian curse tablet (DefOlb 16), an individual with this same name occurs in two commercial letters from Olbia and Kerkinitis,Footnote 69 the latter of which dates to the same years as the Olbian curses, and involves the transport of saltfish and a payment to the Scythians, commercial and financial dealings that might land in the courts. Some of these inscriptions may document the activities of the same individual, who would come into still sharper focus with the addition of a kylix fragment also inscribed with the name Apato(u)rios from fifth-century Olbia (SEG 32.802). Not only could this reveal regional mobility patterns but also, in this instance, the prominence of the cult of Aphrodite Apatouros in the Bosporan Kingdom.Footnote 70 A connection with the Panionian Apatouria festival proves difficult to ignore, and the regional popularity of the name may highlight broader assertions of Ionian, especially Milesian, identity.

Prosopographic inquiries can also be made of individuals named Agatharchos in fourth-century Olbia, Dionysios at Olbia (in no fewer than six curse tablets), Nikonion and Chersonese in the late fourth century BC, Neomenios/Neumenios in Kerkinitis and Pantikapaion in the early fourth century BC, Aristokrates in Hermonassa and Olbia in the fourth century BC, Dorieos at Olbia and Chersonesos, and so on.Footnote 71 With commerce so important to north Pontic economies, it is possible that some of these texts document the same individuals, whose regional networks can then be analysed. Work in this area has recently been undertaken by Belousov in regard to the prosopography of Olbian magical inscriptions (in Russian), and will be expanded in future years to include that of curse tablets from the Bosporan Kingdom.

ii. Enslaved persons

The regional traffic in enslaved persons can also be studied by way of north Pontic letters and curse tablets.Footnote 72 Phaulles’ journey from the Scythian interior to Berezan to Phanagoria documents a distinct type of interaction between Pontic Greeks and non-Greeks: that of enslavement, and the regional circulation of human capital.Footnote 73 The forced transport in Diodoros’ ship of Charilos, shipped on the order of Oreos around (and perhaps beyond) the Bosporan Kingdom, speaks to this same phenomenon: the north Pontic trade in enslaved persons. The slaves of Xenomenes (παίδων τῶν Ξϵνομένους), cursed in SGD 170 above, quite probably shared similar journeys in captivity, and similar hardships. Even within a small sample of north Pontic texts, the vocabulary used to refer to enslaved persons is expansive; we encounter the terms δοῦλος, ἀνδράποδον, ὁ/ἡ παῖς, ἡ παιδίσκη, οἰκιητέων (‘domestic slaves’) and τὸ παιδίον, all of which suggest the regional prominence of the slave trade. Slaves were lucrative exports, sold at both local and regional markets, in addition to those further afield at Byzantion, Miletus and Athens.Footnote 74 References to enslaved persons emerge in no fewer than nine north Pontic letters, 25 per cent of the regional corpus, a strikingly large proportion.Footnote 75 By contrast, the contemporary corpus of private letters from the Gulf of Massalia, while also sizeable and concerned with commercial matters (citing helmsmen, merchants, ships, cargo (vases, oil), money, weights and measures), contains only one certain (later) letter that refers to slaves (third/second century BC).Footnote 76 The traffic in enslaved persons operated on a significant scale in the northern Black Sea from the sixth through fourth centuries BC.

iii. Law courts

The coordinated study of both corpora also coalesces around the law courts, institutions crucial for adjudicating disputes that arose in relation to the high degree of regional trade and commerce. Citing evidence from private letters, Parmenter has argued that the law courts played an active role in the enslavement of Greek and non-Greek persons in the Black Sea: ‘As the letters show, not only were judicial or pseudo-judicial proceedings in Greek colonies an important mechanism for enslavement, but non-Greeks themselves often had access to them as plaintiffs’.Footnote 77 If the courts did adjudicate conflicts related to the trade in enslaved persons, then it is probable that some of the region’s many judicial curses stemmed from such disputes, as discussed above; this would explain the presence of Xenomenes’ slaves (παίδων, B.I.3) and Neumenios the helmsman (κυβϵρνήτην, A.I.3–4) in SGD 170 from Pantikapaion. Many crises documented in north Pontic letters may have played out in the law courts, from the seizure of persons and goods by Matasus at Berezan and Herakleides at Olbia to the eviction of Artikon’s household at Olbia.Footnote 78 A case in point is a lead letter from Pantikapaion, which documents the preparation of enslaved persons, wood, a cable and maybe a coffin.Footnote 79 The text refers to monetary transactions on a large scale: sums of money assessed in drachmas and talents are thrice mentioned in the lacunose text, with the references to talents signalling that lucrative dealings were afoot. Should complications emerge in such exchanges, the dispute could move to the courts, a process which could then, in turn, prompt curse-writing. The region’s grounding in commerce drove the development of both a centralized judiciary system and private curse rituals. The courts obviated the need for private, vigilante retaliations and confiscations, like that documented in the letter of Achillodoros, which could be violent in nature. Shifting the process of seeking justice from the private to the public realm no doubt improved civic life within these frontier poleis, even if there were still private interventions by way of curse-writing rituals. Indeed, the regional abundance of judicial curse tablets points to the prominence of the courts as adjudicators of conflict by the fourth century.

iv. Epigraphic habits and mercantile literacy

Private letters and curse tablets document the interaction and mobility of persons, goods and information within and across the north Pontic poleis. Let us conclude by reflecting on written literacy and the so-called epigraphic habit in the northern Black Sea during the sixth through fourth centuries BC. In one description of long-distance maritime commerce, letter writing is portrayed as crucial for the transmission of time-sensitive information related to lucrative trade dealings. The Demosthenic speech Against Dionysodorus demonstrates how merchants were able to communicate over long distances using letters; these written texts facilitated commerce, and helped maximize profits for Athenian traders ([Dem.] 56.8):

Those then who stayed here were sending letters (ἔπϵμπον γράμματα) to those abroad advising them of the prevailing prices, so that if grain was costly in your market, they might bring it here, and if the price should fall, they might put in to some other port. This was the chief reason, men of the jury, why the price of grain increased; it was on account of such letters (ἐπιστολῶν) and collusions.

The development of mercantile literacy is well documented from the sixth through fourth centuries, and was linked to long-distance commerce and the need to give business communications, receipts and contracts a static but motile form. As demonstrated by Jean-Paul Wilson for traders of the Archaic period in sites as disparate as Pech Maho (Aude, France) and Corcyra, commercial demands required that merchants be able to read and write, however basically (or at least, merchants who had mastered these skills enjoyed significant trade advantages).Footnote 80 Indeed, some of the oldest Pontic letters make reference to the written records used by merchants and their agents in the field; Apatourios orders Leanax to send διφθέρια, records probably written on leather, as proof of ownership for seized property around 500 BC.Footnote 81 These διφθέρια likely included receipts of goods and services, replete with numbers and measures like those found in letters from Olbia (‘27 staters’, ‘drachmas’, ‘talents’) and Nikonion (‘nine medimnoi of barley’, ‘a half-stater’). Dating from the fourth century BC, a letter from the hinterland of Olbia refers to documents, τὰ γράμματα, destined for a certain Zopyrion: καὶ δότω [αὐ]τ̣ῶι τὰ γρά<μ>ματ̣α, ‘and give the documents to him’.Footnote 82 These were exchanges in which written text was common. Such literacy did not require polished grammar or syntax, or the ability to read or compose verse or literary prose. Rather, it made use of calculations and colloquialisms, and exhibits great numerical competence. Information was clearly conveyed. Many Pontic letters, receipts and curses have a practical starkness to them, and were composed without the use of articles or semantic elaboration; these texts were created and read by persons possessing functional levels of literacy, whose livelihoods had frequent need for written communication.Footnote 83

Recent scholarship in the field of sociolinguistics has shown that mercantile communities, among which Olbia, Myrmekion, Pantikapaion and other north Pontic cities can be included, are often important loci of linguistic change and innovation. Such populations possessed degrees of ‘mercantile’ or ‘pragmatic literacy’, and contributed to what Rosalind Thomas has called a ‘literate environment’. Footnote 84 In these commercial havens, change was continuously driven by fluid, progressive language policies, which stemmed from multilingual communities and large interconnected networks; in the northern Black Sea, this included interactions within and across apoikiai, metropoleis and native inland communities. Professionals with the greatest geographic mobility, such as the merchant Oreos and the helmsmen Diodoros and Neumenios, also tended to have the widest social networks. These groups could adopt and spread certain types of literacy along with innovative linguistic forms. Mercantile texts exhibit cross-linguistic features, from language mixing to use of the vernacular to code-switching (the use of more than one linguistic variety in a manner consistent with the syntax and phonology of each variety), and we have seen aspects of these in the documents above.Footnote 85 In north Pontic letters and curse tablets, such hallmarks of mercantile literacy could include idiomatic expressions and colloquialisms (τὸ̣ ἔνθ᾿ ἐγένϵτό μοι ἐν τῶι τραχήλωι, ‘something happened into my neck/throat’; καὶ τὸς αὀτῶι συνιόντας πάντας, ‘and all those who go along with him’; Mα]τάσυ⟨ι⟩ δὲ τί αὐτῶι κάναξαγόρη αὐτοὶ οἴδασι κατὰ σφᾶς αὐτōς, ‘what there is between Matasus and Anaxagoras, they alone know’) and various dialectal forms (the Doricisms in SGD 170 and SEG 55.859). One Olbian curse tablet may also bear evidence of code-switching.Footnote 86 The regional prominence of commerce cultivated a broad range of functional literacy within a subset of the population that was also highly mobile. This further propelled the diffusion of written communication and literacy among these groups.

In the study of Greek history, merchants like Oreos and helmsmen such as Diodoros and Neumenios often remain nameless to us, their lives confined to the background of more dramatic historical narratives. Yet trade was the lynchpin of many historical processes in the ancient Greek world: commerce propelled new ideas and technologies across time and space, sometimes over vast distances, as it did persons and objects. In the northern Black Sea, these movements and interactions are documented by private letters and curse tablets, both of which were inscribed on sheets of lead and, occasionally, on ostraca or bowls. In this article I have endeavoured to survey and synthesize these bodies of documentary text, providing overviews of both corpora along with recent editions. Considered in tandem, private letters and curse tablets document the ways in which commerce could galvanize broader social and economic developments within Greek port communities, from written literacy to judicial institutions. Together, these texts advance studies of onomastics, prosopography, regional economies, trade, law and literacy across the northern Black Sea. They illuminate agents and interactions that often pass unmentioned in ancient source material and modern discussions of Greek history.

Acknowledgements

I thank the Editor, Lin Foxhall, for her valuable comments on this article, in addition to the anonymous JHS reviewers. Alexey Belousov and Madalina Dana offered valuable discussions about north Pontic inscriptions, while Denise Demetriou and Matthew Simonton improved earlier versions of this text: I thank them warmly. This article was completed in 2020 (indeed, before Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine again transformed, and upended, the region under discussion), and with a few exceptions, reflects bibliography up to that date.