Left ventricular hypertrabeculation is a cardiac abnormality increasingly recognised by neurologists as well. According to the American Heart Association/European Heart Association guidelines, left ventricular hypertrabeculation, also known as left ventricular non-compaction or non-compaction, is an unclassified cardiomyopathy characterised by a regionally bi-layered left ventricular myocardium distal to the papillary muscles.Reference Maron, Towbin and Thiene 1 The endocardial layer is thicker than the epicardial layer and is characterised by a meshwork of interwoven myocardial strands lined with endocardium. The epicardial layer is thinner than the endocardial layer and is compacted.Reference Stöllberger, Gerecke, Finsterer and Engberding 2 Spaces between trabeculations are perfused from the ventricular side, but the non-physiological flow facilitates thrombus formation. Non-compaction may occur in isolation without other cardiac diseases or together with other cardiac abnormalities – such as hypertrophic, dilated, or restrictive cardiomyopathies – or cardiac malformations – such as Ebstein’s anomaly, tetralogy of Fallot, ventricular septal defect, atrial septal defect, hypoplastic right ventricle, non-compaction of the right ventricle, myocardial bridges, absence of the pericardium, mitral valve prolapse, tricuspid atresia, pulmonary atresia, bi-cuspid aortic valve, congenital aortic stenosis, double-orifice mitral valve, aortic interruption, patent ductus arteriosus, congenital atresia of the coronary arteries, or coronary aneurysms. Non-compaction is usually asymptomatic but can be complicated by cardiac embolism, ventricular arrhythmias with sudden cardiac death, or heart failure.Reference Stöllberger, Blazek, Wegner, Winkler-Dworak and Finsterer 3

The aetiology of non-compaction is unknown, but in the majority of cases it is speculated to result from non-compaction of the myocardium during embryogenesis. This assumption is challenged by patients who are diagnosed with non-compaction in adulthood but do not show non-compaction on previous echocardiographies (acquired non-compaction).Reference Finsterer, Stöllberger and Schubert 4 In addition, 7% of primigravida develop non-compaction during pregnancy, and 25% develop hypertrabeculation, although the differentiation between non-compaction and hypertrabeculation in the latter study is unclear.Reference Gati, Papadakis and Papamichael 5 Non-compaction has also been observed 2 weeks post-partum.Reference Rehfeldt, Pulido, Mauermann and Click 6 A third argument that supports the hypothesis that non-compaction is not only congenital is the observation that athletes develop hypertrabeculation of the left ventricle when performing extreme exercise training.Reference Peritz, Vaughn, Ciocca and Chung 7 In pregnant females, the development of non-compaction was attributed to increased pre-load conditions.Reference Gati, Papadakis and Papamichael 5 Several other speculations such as reduced adhesion of cardiomyocytes, frustrate attempt to overcome a metabolic defect, weak myocardium, micro-infarction, adaptation to increased stroke volumes, or enlargement of the endocardium to improve oxygenation have been raised to explain acquired non-compaction.Reference Finsterer, Stöllberger and Schubert 4 In rare cases, non-compaction may disappear over time.Reference Stöllberger, Kolussi and Hackl 8

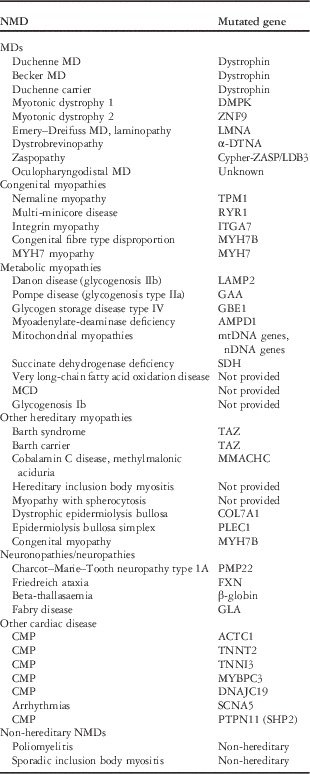

Non-compaction is frequently associated with a variety of different neuromuscular disorders (Table 1),Reference Finsterer, Stöllberger, Brandau, Laccone, Bichler and Laing 9 but no causal relationship between non-compaction and any neuromuscular disorder has been established so far. A strong argument against a causal relationship is that non-compaction occurs only in a minority of patients with neuromuscular disorders, even when they are systematically screened for non-compaction. A further argument against a causal relationship is the large variability of neuromuscular disorders that are associated with non-compaction, suggesting a compensatory rather than a causal mechanism. An argument in favour of a hereditary cause, however, is the familial occurrence of non-compaction.Reference Basu, Hazra, Shanks, Paterson and Oudit 10 As up to 80% of the patients with non-compaction are associated with a neuromuscular disorder,Reference Stöllberger, Finsterer and Blazek 11 it is recommended to screen non-compaction patients systematically for neuromuscular disorders.Reference Stöllberger, Finsterer and Blazek 11 Neuromuscular disorders most frequently associated with non-compaction are the mitochondrial disorders followed by Barth syndrome, Duchenne muscular dystrophy, and myotonic dystrophy 1.Reference Finsterer 12 In addition to neuromuscular disorders, non-compaction is frequently associated with cardiomyopathies other than non-compaction and with chromosomal defects.Reference Finsterer 12

Table 1 Human NMDs and cardiomyopathy associated with LVHT

CMP=cardiomyopathy; LVHT=left ventricular hypertrabeculation; MCD=malonyl coenzyme (COA) decarboxylase deficiency; MDs=muscular dystrophies; NMD=neuromuscular disorder

For the neurologist, it is important to be familiar with non-compaction for two reasons: first, patients with non-compaction are potential neuromuscular disorder patients, and thus they should be thoroughly investigated for overt or sub-clinical neuromuscular disorders. Second, neuromuscular disorder patients frequently present with cardiac involvement, of which non-compaction is one of the possible manifestations. As the presence of non-compaction in a neuromuscular disorder patient has prognostic implications, it is advisable to screen neuromuscular disorder patients for this cardiac abnormality and to institute appropriate therapeutic measures, including oral anticoagulation in case of non-compaction and atrial fibrillation or non-compaction and heart failure or systolic dysfunction, implantation of an implantable cardioverter defibrillator in case of ventricular arrhythmias, or to initiate heart failure therapy or heart transplantation in case of intractable heart failure.