Rapid tryptophan depletion (RTD) paradigm induces a transient relapse of depressive symptoms in approximately 50% of patients with recently remitted depression treated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) but not in those treated with norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (NRIs) (Reference Delgado, Miller and SalomonDelgado et al, 1999). The RTD does not induce any mood changes consistently in healthy volunteers (Reference Lam, Bowering and TamLam et al, 2000). The RTD probably decreases brain 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) levels in all groups, but only 50% of SSRI-treated patients experience depressive relapse; hence, a decrease in brain 5-HT alone cannot account for a depressive relapse. It is, however, conceivable that a decrease in brain 5-HT levels could induce changes in another component of the 5-HT system, such as the 5-HT2 receptors that determine whether or not a subject experiences depressive symptoms. In this study, we assessed the effects of RTD on brain 5-HT2 receptors in healthy women using positron emission tomography (PET) and 18F-labelled setoperone (18F-setoperone).

METHOD

Subjects

This study was approved by the University of British Columbia human ethics committee. Subjects for the study were recruited through advertisements. They were evaluated by a structured clinical interview for DSM-IV, non-patient version (SCID-NP; Reference Spitzer, Williams and GibbonSpitzer et al, 1992). Because reduction in the rate of 5-HT synthesis is greater in women following RTD (Reference Nishizawa, Benkelfat and YoungNishizawa et al, 1998), we recruited ten women with no life-time history of psychiatric diagnosis and no family history of psychiatric disorders in the first-degree relatives for participation in the study. Subjects' ages ranged from 21 to 47 years, with a mean (s.d.) of 30.3 (7.87) years. All subjects were physically healthy, drug free and gave written informed consent for participation in the study.

Positron emission tomography scanning and RTD protocol

All study subjects had a high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging scan of the head to exclude cerebral pathology and facilitate localisation of brain regions in PET images. The 18F-setoperone was prepared by a modified method of Crouzel et al (Reference Crouzel, Venet and Irie1988), as described by Adam et al (Reference Adam, Lu and Jivan1997). Each subject was scanned on two separate days 5 h after the ingestion of amino acid mixtures. The scanning on one day was preceded by the ingestion of a nutritionally balanced mixture (15 amino acids and 2.3 g of L-tryptophan; control session) and on the other day by the ingestion of a tryptophan-deficient amino acid mixture (15 amino acid drink that contained all the other amino acids but no tryptophan; RTD session). The composition of the amino acid mixture was the same as that used by Delgado et al (Reference Delgado, Miller and Salomon1999). The amino acid mixture was flavoured with chocolate syrup and the unpleasant ingredients were given in a capsule form. The administration of the amino acid mixture was done in a randomised, counterbalanced protocol, with two test days separated by at least 5 days.

Subjects presented to the Mood Disorders Clinical Research Unit at 7 a.m. At 7.15 a.m., an intravenous cannula was inserted and a blood sample was drawn for free tryptophan levels. Behavioural ratings were completed prior to and 5 h after the ingestion of amino acid mixtures. Ratings included a 20-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD) consisting of the 29-item HRSD (Reference Williams, Link and RosenthalWilliams et al, 1991) modified to exclude the nine items that could not be rated within the same day, such as sleep, eating (because patients were fasting), weight and diurnal variation. We also administered the Profile of Mood States (POMS; Reference McNair, Lorr and DroppelmanMcNair et al, 1988) to detect subclinical mood changes. After subjects ingested the amino acid mixture, they stayed in a room for the next 5 h. During this period, subjects were allowed to read magazines. Approximately 5 h later, they had a second blood sample drawn for free tryptophan levels. Following this, the subjects were escorted to the PET suite.

Blood samples were centrifuged immediately for 30 min and an ultrafiltrate of plasma was obtained by additional centrifuge (2000 g) at room temperature for 30 min through a cellulose ultrafiltration membrane system (Amicon Co., Beverley, MA, USA) for assay of plasma free tryptophan levels. The ultrafiltrate samples were frozen at ‒70°C and later assayed using high-performance liquid chromatography with fluorometric detection (Reference Anderson, Young and CohenAnderson et al, 1981).

Subjects had a transmission scan done to correct PET images for attenuation. Following this, subjects were given 148-259 MBq of 18F-setoperone intravenously. The radioactivity in the brain was measured with the PET camera system ECAT 953B/31 (CTI/Siemens, Knoxville, TN, USA). The spatial resolution of images is about 5 mm. We performed 15 frame dynamic emission scans on each subject for a total of 110 min. The numbers and durations of the frames were as follows: 5 × 2 min (10 min), 4 × 5 min (20 min), 4 × 10 min (40 min) and 2 × 20 min (40 min). The subjects underwent the same protocol 5-7 days later, so that by the end of the second test session the subjects had 18F-setoperone scans preceded by an RTD session and control test sessions. At the end of each test session, subjects were assessed clinically. None had any substantial changes in mood.

Data analysis

A multipurpose imaging tool (Reference Pietrzyk, Herholz and FinkPietrzyk et al, 1994) was used to draw regions in frontal, temporal and parietal cortex and cerebellum. When time-activity curves were plotted, they showed that the cortex/cerebellum ratio was constant between 70 and 110 min, indicating the occurrence of pseudo-equilibrium during this time period for the tracer. Hence, the PET data obtained during this period were used for comparing the differences in binding between the RTD and control sessions.

If it is assumed that there is no specific binding to 5-HT2 receptors in the cerebellum and, furthermore, that non-specific binding is the same in cerebellum as in cortex, the ratio of binding in cortex (Cx) to cerebellum (Cb) is given by:

where B max is the total number of receptors, K d is the equilibrium dissociation rate constant of the ligand-receptor complex and f2 = 1/[1 + (k5/k6)], where k5 and k6 are the transfer coefficients for association to and dissociation from non-specific binding sites. The ratio B max/K d is known as the specific binding potential. Because the time course of 18F-setoperone accumulation in cerebellum is not affected by saturating doses of the 5-HT2 blocker ketanserin (Reference Blin, Sette and FiorelliBlin et al, 1990), it is reasonable to assume that specific binding in the cerebellum is negligible. However, recently, Petit-Tabou et al (Reference Petit-Tabou, Landeau and Barre1999) have shown that the non-specific binding is lower in cortex than that in cerebellum in humans. Under circumstances where non-specific binding in cerebellum differs from that in cortex, the ratio of binding in cortex to that in cerebellum is given by:

where f2cb is the value of f2 derived using cerebellar values for the transfer coefficients k5 and k6, whereas (k5/k6)cx is evaluated using cortical values for k5 and k6. Assuming that non-specific binding is not affected by tryptophan depletion, the change in Cx/Cb between the baseline and depleted sessions is given by:

where Δ(B max/K d) is the change in specific binding potential.

An alternative approach would be to employ a change in the ratio of regional to mean global cortical setoperone concentration to obtain a value that is proportional to the change in local binding potential between conditions (see Reference Yatham, Liddle and DennieYatham et al, 1999), for details). This method has the advantage of circumventing the uncertainty surrounding the differences in non-specific binding between cortex and cerebellum. This method, however, is only valid provided that the mean global binding potential does not vary substantially between conditions. Our data suggest that the mean (s.d.) global binding potential was significantly lower in the RTD session (1.56965 (0.38850)) than in the control session (1.64726 (0.35139)) (P<0.01) and hence this method cannot be used to compare the differences in binding between the sessions.

We therefore employed the method based on the ratio of cortical to cerebellar binding to derive a measure of change in 5-HT2 receptor binding potential for each voxel from the measured change in cortex/cerebellum ratio (employing Equation (3)), assuming that the non-specific binding in cortex and cerebellum did not vary significantly between the RTD and control sessions. Furthermore, it should be noted that the quantity that is determined for each subject is not the change in binding potential itself, but is f2cbΔ(B max/K d). None the less, under the assumption that non-specific binding is not affected by tryptophan depletion, this quantity can be regarded as a measure of change in binding potential.

Statistical Parametric Mapping (SPM96) software (Friston et al, Reference Friston, Frith and Liddle1991, Reference Friston, Holmes and Worsley1995) was used to align PET images, co-register them to magnetic resonance images and transform the magnetic resonance images (and PET images) into the standard coordinate frame used for templates in SPM96. Then an 18F-setoperone binding image was created by dividing each pixel in the RTD and control session realigned normalised mean images by that image's average cerebellar value. A mean activity value from two large regions of interest (one on the right and one on the left) drawn on three contiguous cerebellar slices was used as that image's average cerebellar value. The binding images were smoothed by applying a 12-mm full width at half-maximum (FWHM) isotropic Gaussian filter to improve the signal-to-noise ratio.

Statistical analysis

Statistical parametric mapping (SPM96) software was used to determine the change in cortex/cerebellum ratio (hereafter referred to as the 5-HT2 binding potential: 5-HT2BP) between the RTD and control sessions. The grey matter threshold was determined using a multipurpose imaging tool (Reference Pietrzyk, Herholz and FinkPietrzyk et al, 1994) and was set at 1.3 times the mean global cerebral image intensity, to exclude non-grey matter voxels in the analysis. For each voxel, the Z value corresponding to the t statistic for the difference in 5-HT2BP between the RTD and control sessions was computed. We also computed the Z value for each voxel for the difference in 5-HT2BP between the first and second scans for each subject to examine the order of scanning effects. In estimating the significance of change in individual voxels, the method developed by Worsley (Reference Worsley1994) as implemented in SPM was used to correct for multiple comparisons, taking into account the correlation between voxels. In addition, we also computed the significance of change in clusters of contiguous voxels exceeding a threshold of Z = 2.33, as implemented in SPM96 based on the method of Poline et al (Reference Poline, Worsley and Evans1997).

Behavioural and plasma free tryptophan data were analysed using paired and unpaired t-tests and repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) with time and session as intrasubject factors. Data are presented as mean (s.d.) and all tests were two-tailed, with significance set at P<0.05. All analyses were performed on a personal computer using the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) software, version 7.5 (SPSS, 1996).

RESULTS

Effects of RTD on plasma free tryptophan levels and mood

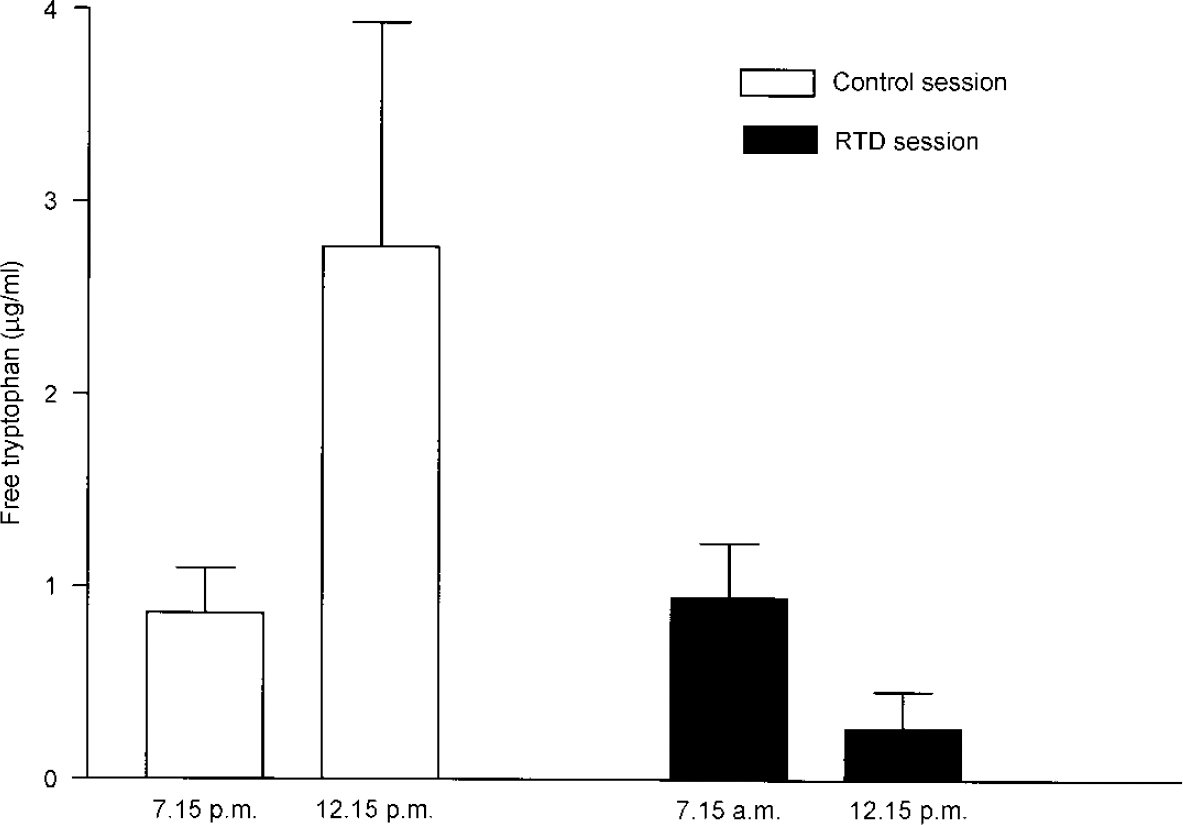

Figure 1 shows the plasma free tryptophan levels during the RTD and control sessions. Baseline mean (s.d.) plasma free tryptophan levels did not differ significantly between control (0.86 (0.07) μg/ml) and RTD (0.95 (0.09) μg/ml) sessions (t=-0.72, d.f.=18, P=0.47). As expected, the RTD session significantly reduced plasma free tryptophan levels (to 0.27 (0.19) μg/ml, 71.5% decrease) (t=7.76, d.f.=9, P<0.0001), whereas in the control session there was a significant increase in plasma free tryptophan levels (to 2.76 (1.16) μg/ml; t=-5.51, d.f.=9, P<0.0001). Moreover, repeated-measures ANOVA showed a significant session × time interaction effect (F=46.2, d.f.=1, 9, P<0.0001), indicating that RTD led to a significant reduction in the plasma free tryptophan level when compared with the control session. With regard to behavioural rating, none of our study subjects became depressed during either session, as shown by no significant changes in the HRSD and POMS ratings (not shown; data available from L.N.Y. upon request).

Fig. 1 Mean (s.d.) plasma free tryptophan levels during rapid tryptophan depletion (RTD) and control sessions in ten healthy subjects.

Effects of RTD on brain 5-HT2 receptors

The 5-HT2BP was decreased significantly following the RTD session compared with the control session. Analysis with SPM showed an extensive cluster of voxels embracing frontal, temporal, parietal and occipital cortical regions (Fig. 2). The reduction in 5-HT2BP in this cluster was highly significant even after correcting for multiple comparisons (P<0.0001) (Table 1). The cluster included 28 106 voxels and this corresponds to about 39% of the volume of grey matter that was in the field of view. The mean reduction in 5-HT2BP was 7.9% for the entire cluster. There were 134 voxels within this cluster that satisfied the criteria for significance for individual voxels.

Fig. 2 Statistical parametric maps of t values displayed as maximum intensity projections on the sagittal (upper left), transverse (lower left) and coronal (upper right) renderings of the brain. These projections show regions of decreased 18F-setoperone binding following an RTD session. Voxels for which Z exceeds 2.33 are shown in shades of grey (range 2.33-4.67).

Table 1 Cluster size, P and Z values, and coordinates with P and Z values, for brain regions with significant decreases in 18F-setoperone binding in ten healthy subjects following a rapid tryptophan depletion (RTD) session

| Cluster | Voxels | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Size | Z value | Corrected P value | Z value | Corrected P value | Coordinates | Brain region | ||

| x | y | z | ||||||

| 28 106 | 4.67 | 0.000 | 4.67 | 0.004 | -56 | -38 | -22 | Left fusiform gyrus |

| 4.51 | 0.008 | -38 | -20 | 4 | Left insula | |||

| 4.50 | 0.008 | -56 | -30 | 14 | Left superior temporal gyrus | |||

| 4.18 | 0.029 | -24 | 56 | 10 | Left superior frontal gyrus | |||

The location and Z value for change in 5-HT2BP at local maxima where Z exceeded 4.00 (P<0.025 after correction for multiple comparisons) are given in Table 1). The areas that showed the most significant decrease in 5-HT2BP included the left fusiform gyrus, left insula, left superior temporal gyrus and left superior frontal gyrus (Table 1 and Fig. 3).

Fig. 3 Sagittal renderings of the brain showing areas of significant decreases in 18F-setoperone binding indicated by arrows (1, left superior temporal gyrus; 2, left fusiform gyrus; 3, left insula; 4, left superior frontal gyrus; 5, left superior frontal gyrus) in ten healthy subjects following an RTD session.

There was no difference in 5-HT2BP between first and second scans, indicating that scanning order had no systematic effect on 5-HT2BP.

DISCUSSION

This is the first study to measure the effects of RTD on brain 5-HT2 receptors in living humans using PET and 18F-setoperone. Our findings indicated that RTD led to a significant widespread reduction in 5-HT2BP in various cortical regions bilaterally. The reduction in 5-HT2BP was particularly prominent in the left fusiform gyrus, left insula, left superior temporal gyrus and left superior frontal gyrus.

A potential source of artefactual result must be considered before ascribing the decrease in 5-HT2BP to a true decrease in 5-HT2 receptor density. The estimates of 5-HT2BP might have been confounded by changes in endogenous 5-HT levels that would have occurred following RTD. Several studies in recent years have suggested that the in vivo measurement of neurotransmitter receptors is affected by changes in the levels of endogenous neurotransmitter. This has been demonstrated very elegantly in the case of D2 receptors by manipulating endogenous dopamine levels (Reference Breier, Su and SaundersBreier et al, 1997; Reference Laruelle, D'Souza and BaldwinLaruelle et al, 1997). These studies have shown that increasing the synaptic dopamine concentration with amphetamine or methylphenidate reduces, whereas decreasing the synaptic dopamine concentration with dopamine synthesis inhibitor α-methyl-p-tyrosine (AMPT) increases, the striatal D2 receptor binding as measured with 11C-raclopride (Reference Breier, Su and SaundersBreier et al, 1997) or 123I-iodobenzamide (IBZM) (Reference Laruelle, D'Souza and BaldwinLaruelle et al, 1997). It is, therefore, conceivable that the changes in endogenous 5-HT levels could affect the estimates of 5-HT2 receptor binding with PET. However, RTD is expected to decrease rather than increase brain 5-HT levels. This should leave a greater number of 5-HT2 receptors unoccupied. In such a situation, one would expect to see an increase in 5-HT2BP as measured with 18F-setoperone. Because we found a decrease in 5-HT2BP, this is unlikely to be due to a confounding effect of a decrease in brain 5-HT levels.

Is the decrease in 5-HT2BP due to a change in 5-HT2 receptor affinity or density?

The methods used in this study provide a semi-quantitative estimate of 5-HT2BP but do not permit an independent determination of B max (density) or K d (affinity). Therefore, we cannot tell whether the decrease in 5-HT2BP observed in the study subjects following RTD was due to a decrease in B max or an increase in K d. However, most (Reference Peroutka and SnyderPeroutka & Snyder, 1980; Reference Kellar and StockmeierKellar & Stockmeier, 1986; Reference Paul, Duncan and PowellPaul et al, 1988; Reference Mason, Walker and LittleMason et al, 1993; Reference Klimek, Zak-Knapik and MackowiakKlimek et al, 1994; Reference Hensler and TruettHensler & Truett, 1998), although not all (Reference Blackshear and Sanders-BushBlackshear & Sanders-Bush, 1982), studies that examined the acute or chronic effects of antidepressants or electroconvulsive shock on various 5-HT receptors in rats reported an alteration in B max and not K d; this would suggest that pharmacological or somatic interventions commonly lead to changes in B max and not K d. Hence, the decrease in 5-HT2BP observed in our study subjects is more likely to be due to a decrease in B max than to an increase in K d.

Could 5-HT2 receptors down-regulate rapidly?

Another issue that needs to be considered before ascribing the decrease in 5-HT2BP to a decrease in B max and hence to a decrease in 5-HT2 receptor density is whether receptor density could change within a 6-7 h time period following an intervention. Indeed, animal studies have shown that 5-HT2 receptor density was significantly reduced 48 h after a single dose of mianserin (Reference Blackshear and Sanders-BushBlackshear & Sanders-Bush, 1982; Reference Hensler and TruettHensler & Truett, 1998). Similarly, rats that received injections of 5-HT2 agonist DOM (4-methyl-2,5-dimethoxyphenylisopropylamine) every 8 h showed a significant decrease in 5-HT2 receptors in frontal cortex following the second injection (Reference Leysen and PauwelsLeysen & Pauwels, 1990). Other studies have shown that treatment with imipramine, amitriptyline and desipramine for 2-7 days also led to a reduction in 5-HT2 receptor density (Reference Paul, Duncan and PowellPaul et al, 1988; Reference Mason, Walker and LittleMason et al, 1993). A single dose of fluoxetine decreases 5-HT1A receptor density within a 24-h period (Reference Klimek, Zak-Knapik and MackowiakKlimek et al, 1994), therefore it is feasible that RTD could lead to a rapid reduction in 5-HT2 receptor density.

Should tryptophan depletion cause an up-regulation rather than a down-regulation of 5-HT2 receptors?

In general, neurotransmitter receptors upregulate following depletion of a neurotransmitter or administration of an antagonist, and down-regulate following the administration of an agonist. However, it is well known that the regulation of brain 5-HT2 receptors does not follow the classical receptor regulation model because both 5-HT2 agonists as well as antagonists consistently down-regulate 5-HT2 receptors (Reference LeysenLeysen, 1990). Also, some animal studies have shown that experimentally induced 5-HT neuronal lesions that deplete 5-HT cause either no change (Reference Butler, Pranzatelli and BarkaiButler et al, 1990) or a decrease in brain 5-HT2 receptors (Reference Leysen, Geerts and GommerenLeysen et al, 1982). These studies indicate that the regulation of 5-HT2 receptors is peculiar and cannot be predicted based on the classic receptor regulation model. Thus, the finding of a decrease in 5-HT2BP following RTD is consistent with what is known about the regulation of this receptor and with the findings of previous animal studies.

Could a change in 5-HT2 receptor density determine whether or not a subject experiences depressive symptoms following RTD?

Our finding of no mood changes in healthy volunteers following RTD is consistent with the findings of previous studies in healthy volunteers (see Reference Lam, Bowering and TamLam et al, 2000, for a review). Could a decrease in 5-HT2 receptor density in our subjects following RTD explain the lack of mood changes? A number of animal studies have indeed shown that most, but not all, antidepressant medications down-regulate 5-HT2 receptors (Reference Peroutka and SnyderPeroutka & Snyder, 1980; Reference Blackshear and Sanders-BushBlackshear & Sanders-Bush, 1982; Reference Cross and HortonCross & Horton, 1988; Reference Paul, Duncan and PowellPaul et al, 1988; Reference Hrdina and VuHrdina & Vu, 1993; Reference Klimek, Zak-Knapik and MackowiakKlimek et al, 1994). Furthermore, we have shown recently in a PET study that patients with depression show a significant decrease in brain 5-HT2 receptors following treatment with desipramine (Reference Yatham, Liddle and DennieYatham et al, 1999). Taken together, these observations may indicate that reduced 5-HT2 receptor density may be potentially a critical event in the prevention and relief of depressive symptoms.

If this were true, only those subjects that fail to down-regulate their brain 5-HT2 receptors following RTD or those that do not have down-regulated 5-HT2 receptors should show a transient relapse of depressive symptoms. Animal studies have shown that desipramine (an NRI) consistently down-regulates 5-HT2 receptors (Reference Peroutka and SnyderPeroutka & Snyder, 1980; Reference Goodnough and BakerGoodnough & Baker, 1994), whereas SSRIs such as fluoxetine do not appear to have consistent effects on 5-HT2 receptors (Reference Peroutka and SnyderPeroutka & Snyder, 1980; Reference Hrdina and VuHrdina & Vu, 1993). The fact that patients treated with NRIs do not relapse following RTD is in keeping with this hypothesis because these patients already would have down-regulated 5-HT2 receptors. This hypothesis would predict that patients treated with SSRIs would be vulnerable to RTD-induced depression because they would not be expected to have down-regulated 5-HT2 receptors. However, only 50% of SSRI-treated patients relapse following RTD; possibly these are the patients that cannot down-regulate their 5-HT2 receptors to prevent relapse of symptoms. There are no PET studies to date that measured the effects of RTD on brain 5-HT2 receptors in patients with depression. However, a recent PET study that examined brain glucose metabolism reported a decrease in the middle frontal gyrus, orbitofrontal cortex and thalamus in those patients who relapsed following tryptophan depletion but not in those who did not relapse (Reference Bremner, Innis and SalomonBremner et al, 1997). This would support the argument that some SSRI-treated patients may be able to mount a compensatory mechanism to prevent the relapse of depressive symptoms. This hypothesis, however, needs to be tested in patients with recently remitted depression before any firm conclusions can be drawn.

Clinical Implications and Limitations

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS

-

▪ A decrease in brain 5-HT2 receptors may be critical in determining whether or not subjects experience depressive symptoms following tryptophan depletion.

-

▪ Brain 5-HT2 receptors may be an important target for an antidepressant effect.

-

▪ A decrease in brain 5-HT levels alone may not cause depressive symptoms.

LIMITATIONS

-

▪ Because this study did not use kinetic modelling, it is not possible to tell whether the decrease in setoperone binding observed in subjects was due to changes in receptor density or affinity.

-

▪ Because none of the subjects experienced depressive symptoms, the study does not answer the question of whether or not the response of 5-HT2 receptors to rapid tryptophan depletion differs between those who become depressed and those who do not.

-

▪ We interpret the observed changes in 5-HT2 receptors as a possible compensatory process that protects against depression, but this study cannot tell us whether 5-HT2 receptors play a role in the pathophysiology of major depression.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by grants from the Medical Research Council of Canada and the Canadian Psychiatric Research Foundation to L.N.Y.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.