Introduction

The Peruvian Constitutional Tribunal (CT), created by the 1993 Constitution, is currently a key institutional actor in Peruvian politics. In a country where the judiciary has always been a second-class and subordinate branch, the CT has gained authority in the years since 2002 by exercising its constitutional adjudication powers in an independent manner.Footnote 1 This activity is controversial. Lauded by some for increasing horizontal accountability and the rule of law, the CT is criticised by others for what they see as an excess of judicial activism. What both defenders and critics agree upon, however, is that an independent constitutional court, capable of ruling in accordance with its own preferences and with the power to regulate the activity of the other branches of government, is an exception in Peru's republican history.Footnote 2

The above mentioned exercise of constitutional control not only contrasts with the Supreme Court and lower-level Peruvian courts, but also with two previous versions of constitutional courts in Peru. The current independence of the Tribunal differs markedly from the CT's predecessor established by the 1979 Constitution, the Tribunal of Constitutional Guarantees (TCG). During the 1979 transition, a Constitutional Assembly gave the TCG the power to rule that laws passed by Congress were unconstitutional. The framers of the Peruvian constitution opted for a new institution to act as guardian of constitutional principles in light of the historical distrust in the ability of the Peruvian Supreme Court to act as an effective check upon the other branches of government. Although established during a period of democratic pluralism (1982–1992), the TCG failed to gain institutional prestige and exercise its constitutional powers. When in April 1992 President Alberto Fujimori and the military closed the Peruvian Congress and the Supreme Court, the TCG was also dismissed.

The activity of the present CT also contrasts with a previous scenario, that defining the role of the CT during the Fujimori regime from 1996 to 2000. After the CT started its work in June 1996, institutional and political restrictions imposed by the dominant Fujimorista majority in Congress stopped the CT from exercising its constitutional mandate. The impeachment of three of its members in May 1997, in response to a ruling in which the judges opposed President Fujimori's re-election plan, was the last in a series of retaliatory actions taken by the Congressional majority to prevent the CT from acting as an independent body. Until the democratic transition of 2000, the CT remained incapable of performing its constitutional duties.

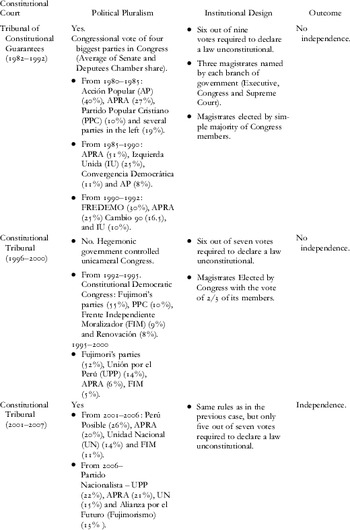

What explains the success of the CT compared to the failure of the two previous experiences? What are the lessons that these three cases provide for our knowledge of the emergence of independent courts in democracies? By comparing the recent history of the CT with its own role during the Fujimori regime, as well as with the case of the TCG during the eighties and early nineties, I examine in this article diverse theories that aim to explain the emergence of independent courts. The variation in the courts' independence found across time in the three Peruvian cases offers a unique opportunity to explore how changes in political and institutional factors explain these different outcomes. Here, I argue that these cases lend support to theories that highlight the importance of political pluralism as a necessary condition for the emergence of independent courts. The current independence of the CT is explained by the existence of a plural political context in which Congress is fragmented and elections are competitive. By contrast, during Fujimori's hegemonic government the CT was impeded from exercising its constitutional authority. However, the case of the TCG in the eighties and early nineties illustrates that political pluralism by itself is not sufficient for a court to achieve independence, as an institutional design that ‘mirrors’ this pluralism is likewise crucial in achieving such an outcome. Table 1 presents these political and institutional conditions from 1980 to 2007. I will conclude by briefly discussing what this analysis suggests for the likelihood that the current independence of the CT will be maintained in the future.

Table 1. Constitutional Courts in Perú: Political and Institutional Conditions

What Explains the Emergence of Independent Courts?

During the last decades of the twentieth century, old and new democracies alike witnessed a considerable increase in the political relevance of courts acting as guarantors of constitutional principles. This process, described by some as the ‘expansion of judicial power’, has gained considerable scholarly attention in the last decade, especially regarding the role these independent courts may play in the consolidation of new democracies.Footnote 3 As discussed by several commentators, Latin America has been no exception to this global trend.Footnote 4

As shown in Table 2, three theories have aimed to explain the current relevance of courts. A first theory to explain the emergence of independent courts, very popular in legal schools, is the ‘diffusion’ theory. Following the Second World War, a growing global conscience emerged with the belief that the Executive and the Legislature, left to themselves, would behave in oppressive ways against minorities. As a consequence, beginning with some European countries and later spreading into many other regions of the world, the US tradition of an independent judiciary armed with judicial review to protect the Constitution spread throughout the globe. In European countries, however, the responsibility to exercise constitutional adjudication was not given to the existing judicial high courts – at the time discredited by their association with authoritarian governments – but to Constitutional courts with abstract review powers.Footnote 5 The heightened importance of independent courts in national politics, then, naturally follows from the spread of this idea.Footnote 6

Table 2. Theories of the Emergence of Judicial Review

Other theories responded to ‘diffusion’ theory by stressing its limitations to account for those cases in which the adoption of judicial review did not lead to its effective exercise by independent courts. According to these theories it is the interests of political actors and their strategic choices that explain the emergence of independent courts. Two perspectives can be distinguished: ‘hegemonic preservation’ theory, as proposed by Ran Hirschl, and a set of theories that can be described as ‘political pluralist’. Tom Ginsburg's ‘insurance’ model will be presented as a paradigmatic example of this second set.Footnote 7

Hirschl's ‘hegemonic preservation’ model predicts that judicial review will be adopted in societies in which dominant actors are afraid of the future effects of democratisation on their interests.Footnote 8 These fears, shared by powerful political and business elites will lead these actors to find a way to ‘entrench’ their preferences, insulating them from the dangers of democratic and egalitarian politics. Negative constitutional rights will be the vehicles used to insulate these preferences from majoritarian interests, and courts with powers of judicial review will be the selected guardians.Footnote 9 Although Courts appear to defend the interests of citizens in new egalitarian societies, they are for Hirschl just a cover-up, unfit to encroach upon entrenched class interests. The power of courts in democracies, then, comes from the decisions made by the threatened but still strong elites.

For political pluralist theories ‘judicial independence correlates with competitiveness in a polity's party system’.Footnote 10 From this perspective judicial independence emerges when political actors foresee that they will be sharing power in the near future: the winners of today may be the losers of tomorrow and vice-versa. Tom Ginsburg's ‘insurance’ model stresses political pluralism as the key factor in explaining the emergence of independent courts in political regimes. The theory can be divided into two parts. First, Ginsburg explains the adoption of judicial review in new democracies as the instrument implemented by incumbent political actors to ‘insure’ certain of their key electoral and political interests. The way incumbents insure these interests is to negotiate with the emerging actors in order to achieve a balance in which none are permitted to dominate and fair competition for power is guaranteed. The prospect of future pluralism makes political groups behave as rational negotiators, entrenching minimal and fundamental values in the Constitution and accepting an independent court as an adequate means of protecting their interests.Footnote 11 In addition to establishing judicial review, negotiating parties must include certain institutional assurances to enhance the court's independence and prevent future political majorities from controlling it: independent budgets, easy access, adequate appointment processes, limits to disciplinary and political actions against the justices, and secured terms in office.Footnote 12 Conversely, for those countries in which a party dominates the constitutional design process, Ginsburg predicts that courts will be granted ‘a more limited scope of authority and be more difficult to access’.Footnote 13

Simply adopting judicial review, however, may not produce any change if certain conditions do not persist. The second part of Ginsburg's theory focuses precisely on the necessary conditions for judicial independence to emerge; namely, that the pluralist political environment must be maintained.Footnote 14 According to this, political actors should be interested to protect independent courts as impartial forums where their present or future interests can be defended even if overridden in the political arena.Footnote 15 If this pluralism does not exist, because either a past hegemonic party regains control or an emerging party becomes hegemonic and trumps democratic rules, it is highly unlikely that courts will find the institutional space to develop. This paper tests the adequacy of these general theories – ‘diffusion’, ‘hegemonic-preservation’ and ‘insurance’ – to the Peruvian case.

Before proceeding, however, it is useful to discuss a fourth way in which a court with judicial review powers can be adopted, and even function independently for a while. The creation of the Egyptian Supreme Constitutional Court discussed by Tamir Moustafa shows that contrary to the prediction of theories that stress political pluralism as a necessary condition for the emergence of an independent court, hegemonic parties sometimes provide courts with considerable institutional independence even if these parties do not expect to lose power in the short term.Footnote 16 Moustafa convincingly argues that one motivation for the Egyptian dominant one party system in creating a court with judicial review powers was to make a ‘credible commitment’ towards external actors. The inclusion of a formally strong Court was intended to represent the government's commitment towards foreign investors, and to demonstrate the regime's willingness to subordinate itself to the authority of an independent third party enforcer. In this way, the Court was able to start acting in an independent – albeit limited – way, reinforcing with its actions the regime's interest in economic policy, but opposing its political interests by broadening civil and political rights. When the Court affected the electoral interests of the government, however, it was deactivated. Ultimately, then, this case confirms the second part of Ginsburg's theory: without a pluralist political environment it is highly unlikely that courts can become independent actors.

Can any of these three theories explain the variation in judicial independence we find across time in our three Peruvian cases? I argue, first, that diffusion plays a more important role for the adoption of formally independent courts with judicial review powers in nascent democracies than is accepted by theories that focus on the strategic choices of political actors, such as Hirschl's or Ginsburg's. The cases, however, confirm the limitations of diffusion in explaining the emergence of independent courts that effectively exercise their constitutional powers. Instead, my analysis of the CT validates theories that stress a plural political environment as a necessary precondition for the emergence of independent courts. During Fujimorismo, a hegemonic government impeded the work of the CT. Starting in 2001, under conditions of political pluralism, the CT became an independent actor in Peruvian politics. However, the case of the TCG also shows that this plural environment is not sufficient for independence to emerge: political pluralism must be supplemented with a reasonable institutional design. The cases show that two aspects of this institutional design deserve special consideration: the rules for the appointment of justices and the number of votes required to declare laws unconstitutional.

The Tribunal of Constitutional Guarantees, or the Failure of Judicial Independence under Political Pluralism (1982–1992)

After eleven years of military government, the 1979 Peruvian Constitution marked the birth of a new democracy. A Constitutional Assembly, composed of diverse political parties from the Left to the Right, drafted a Constitution that included profound democratic reforms. In 1980 a new democratic government was elected in what was perceived as a promising democratic transition. Fernando Belaunde, formerly deposed by the 1968 military coup, ran as the candidate of Acción Popular (AP) and was re-elected as President.Footnote 17

Amongst the constitutional changes agreed to by the Assembly was the granting of judicial review powers to the judiciary for the first time in Peruvian history.Footnote 18 In the past, Peruvian constitutions have given to the Executive and the Legislative the duty to protect citizen rights and liberties. Opting for a ‘mixed’ model as found in other countries in the region, the 1979 Constitution allowed for two systems of judicial review to co-exist: diffused/concrete review and centralised/abstract review. On the one hand, every court in Peru, from lower courts to the Supreme Court, could refuse to apply in concrete cases laws they considered unconstitutional, in line with the US model. On the other hand, following the European model, a special constitutional body was created with the power to declare laws unconstitutional: the Tribunal of Constitutional Guarantees (TCG).Footnote 19 Why was the TCG adopted in the 1979 Constitution? Was it the result of a pact amongst all the parties taking part in the Constitutional Assembly in order to guarantee their interests in the future, as suggested by Ginsburg? Was it a way for business groups, judicial elites and parties from the right to defuse redistributive social demands, as proposed by Hirschl? Or did the members of the Assembly see it as a requirement of new democracies, given the international experience of democratisation and protection of human rights, as suggested by the diffusion theory?

A review of the debates of the Constitutional Assembly and the process by which the TCG was included in the Constitution helps to answer these questions. The constitutional debates show that judicial review was a topic of discussion in the Assembly from the outset.Footnote 20 The decision that had to be made was whether the control of the constitutionality of laws would be given to a new independent body with concentrated review powers as in the European model, or to a strengthened Supreme Court with stare decisis power following the US diffuse model.Footnote 21 To leave constitutional control solely in the hands of the Supreme Court was unpopular amongst some assembly members, who saw this institution as incapable of defending the Constitution. There was not only historical distrust, but also political resistance, as the court had been manipulated and subordinated in previous years by the military government.Footnote 22 These considerations led the assembly to opt for the creation of the TCG as the body in charge of exercising the abstract review of laws.

The first proposal discussed in the Constitutional Assembly presented an ambitious model for the TCG. It included strong review powers and a plural composition, including justices elected by civil society institutions.Footnote 23 This project was strongly criticised by some political representatives, as well as by members of the Supreme Court, leading to its rejection. They claimed that the proposal did not create an arbiter of the three branches of government, but subordinated them to a new and powerful institution that may act against their independence.Footnote 24 These criticisms stimulated a new proposal, ultimately included in the Constitution, of a much more limited TCG. First, the ruling by which the TCG could declare a law unconstitutional would have no immediate effects, but would have to be sent to Congress so this body could reform the law according to the ruling. The TCG was to consist of nine judges, three elected by each of the branches of government (Executive, Judiciary and Congress), for terms of six years. Three of these judgeships, one from each branch, would expire every two years, with an option for re-election.Footnote 25 The TCG was also given the authority to revise writs of individual rights protection (amparo, habeas corpus), but just as an instance of review (Casación), and only if the Supreme Court had rejected the plaintiff's claim.

One aspect of the design that aimed to guarantee a plural composition of the TCG involved the constitutional rules for the periodic election of new magistrates. The six-year term of these Judges did not coincide with the five-year term of a particular Executive or Congress. This allowed the new political branches, during their term in office, to name two groups of judges to join elected by the previous government. This mechanism was aimed at guaranteeing future plurality between past and present Executive and Congress majorities. Reasonable conditions of access to the courts for political minorities, other constitutional bodies and citizens were also adopted.

The limited institutional design finally included in the Constitution, and the absence of references in the debate demonstrating that the parties understood the TCG as ‘insurance’ for their interests, suggests that political actors were not acting in the mood suggested by Ginsburg. Most political parties seemed to see the TCG more as a threat to their policy-working freedom than as an insurance against an abusive political majority. Nor can one find evidence that parties from the right saw the TCG as a restraint to redistribution as suggested by Hirschl. Furthermore, if the main objective of the negotiating parties was to create either an independent tribunal that would guarantee their interests as eventual political minorities or be a guardian of class interests, how can we explain their relegation of some of the court's more important characteristics to be established in laws promulgated by the next elected Congress? In May 1982, when the law establishing how the TCG was to operate was voted in Congress, it required a supermajority of six votes out of nine to declare a law unconstitutional. This number proved to be excessive, preventing the TCG from reaching decisions and leading to an absurd outcome: most of the TCG ‘rulings’ consisted of a collection of individual opinions with no legally binding power, as they failed to reach the six votes requirement.Footnote 26 Later, in September 1982, the rules for the election of the constitutional judges were approved by Parliament. The rules established that judges would be elected by a majority vote in both chambers of Congress. In practice, this gave a party with a simple majority the power to name all of the Congress's representatives in the court, thus failing to guarantee the interests of political minorities.Footnote 27

The case of the TCG, then, shows that the adoption of judicial review in transitional countries may not be related to strategic negotiations between political forces, but be seen by political actors as a necessary component in new democracies. These findings challenge the lack of importance given by theories such as Ginsburg's or Hirschl's to diffusion theory. Courts seem to be perceived as bodies that necessarily have to be reinforced in transitional countries if the promises of pluralism, equality and liberty are to be achieved. Interestingly, this commitment to judicial independence amongst the members of the assembly was not enough to check their own interests and provide the TCG with an adequate institutional design. Ginsburg's model does not ignore diffusion theory, but merely uses it to explain why courts, rather than other institutions, are nowadays selected to ‘insure’ the respect of minorities. In Ginsburg's theory the political actors' strategic choices are what explain the adoption of judicial review and the enhancement of judicial independence.Footnote 28 What we see in the Peruvian case are actors that adopt judicial review, but without adherence to the insurance model. Actors are better described as cautious about the way in which the court may affect their interests in the future.

The TCG began its work in November 1982 and was closed in April 1992. There is unanimous opinion that it was a complete failure.Footnote 29 Out of just 15 acciones de inconstitucionalidad on which the TCG ruled, it only declared a law as unconstitutional for the first time in 1990, and the law in question was concerned with an expropriation with no political relevance. In its last two years, as discussed below, four laws were declared partially unconstitutional. In writs of habeas corpus, where only five votes were required to reach a decision, the numbers also reveal the weak activity of the TCG – especially considering the context of internal violence and human rights abuses experienced during the eighties in Peru. Out of 1,635 writs of habeas corpus presented from January 1983 to July 1992 in the Peruvian courts – and even though the majority of these petitions were denied – only 99 reached the TCG. Worse still, until 1990 the TCG only reversed two petitions.Footnote 30

What accounts for this failure in the exercise of the court's constitutional duties? Political pluralism was not the problem: as shown in Table 1, four parties (Acción popular, APRA, Partido Popular Cristiano and the alliance Izquierda Unida) were important actors during the eighties. More importantly, APRA and Izquierda Unida, minority parties in the opposition between 1980 and 1985, were the winners of the 1985 election. In effect, that year APRA achieved a narrow majority in both chambers and Izquierda Unida became the second political force. All the conditions highlighted by pluralistic theories of judicial independence, then, were present for the TCG to have become a relevant institutional actor. Why did this not happen?

The answer for this failure is to be found principally in the TCG's institutional design. The above mentioned requirement of six votes to declare a law unconstitutional, combined with the rules concerning the appointment of judges, allowed the Executive to gridlock the TCG. In effect, the Executive was not only able to elect three judges, but due to the way the election process was conducted in Congress (simple majority), they were assured at least one more judge in the original election process, because the parties in the Executive (Acción Popular in alliance with the PPC 1989–1985 and APRA alone from 1985–1990) were able to control a narrow majority of Congress. The point to underscore is that the Executive party did not need to elect all the judges named by Congress to be sure that the TCG would not act against them: given the six out of nine vote requirement, four judges were enough to gridlock the court. Additionally, the possibility of re-election created a pervasive incentive for the judges to remain dependent on the institutions that elected them instead of putting their loyalty in the TCG. One explanation for the TCG's submission to the Supreme Court decisions in habeas corpus and amparo rulings, for example, was the dependence of three justices on the Supreme Court for their re-election.Footnote 31

Manuel Aguirre Roca, one of the TCG magistrates and later a member of the CT, described to the Congressional Commission in charge of drafting the CT articles in the 1993 Constitution how the politicisation of the TCG constrained its independence. According to him,

‘We faced uncomfortable situations when we were unable to attain six votes in constitutional demands or five in Amparo writs, when we were eight magistrates. (During this time a magistrate had retired due to illness.) The Tribunal was a little politicised. To attain eight votes was almost impossible, save in those cases that the issue in play was to benefit the government’.Footnote 32

Yet, it is worth noting that the TCG had opportunities to achieve greater power.Footnote 33 For example, an important test confronted the TCG in 1984, when the opposition parties in Congress (APRA and Izquierda Unida) demanded that it rule as unconstitutional the electoral law for the 1985 election that had ‘interpreted’ the Constitution in such a way as to benefit the incumbent party. The ruling was given in February 1985, two months before the election, and once again the TCG was unable to reach a decision about the constitutionality of the law.Footnote 34 After 1984 and for the rest of the decade, due to its inability to reach decisions and its exceedingly narrow and formalistic reasoning, the TCG was seen as an ineffective body to defend the interests of political minorities.

A month before the 1990 election, Mario Vargas Llosa, leader of an alliance of right wing parties that included AP and Partido Popular Cristiano (also referred to as FREDEMO), was perceived as the sure winner of the Presidency. In the last weeks before the election however, Alberto Fujimori, an outsider, emerged to finish in second place (27 per cent), barely five percentage points behind Vargas Llosa. Two months later Fujimori beat Vargas Llosa in the run off.Footnote 35 No party achieved a majority in the new Congress: FREDEMO, Fujimori's Cambio 90, APRA and some small leftist parties shared power. With the help of his advisor, Vladimiro Montesinos, Fujimori built a close alliance with the Military. From the outset of his term, Fujimori launched a strong attack on political parties and the judicial system, blaming them for Peru's economic and political crisis.Footnote 36

It was in this context that the TCG, at last, put up a fight. To respond to an unprecedented economic crisis, the new government, supported by FREDEMO, started an ambitious process of market reform. This led to a situation in which left wing and centrist parties presented acciones de inconstitucionalidad against a number of the reforms. The previously submissive TCG began to exercise its authority by resolving claims against various laws and legislative decrees on economic issues. During 1991 and until March 1992, a TCG composed mainly of judges elected by the defeated parties in the 1990 election declared four pieces of legislation concerning economic matters partially unconstitutional. The four pieces included one law reforming the labour regime of state employees and three legislative decrees (given by the Executive) liberalising public transport, reforming the economic regime as specified in the Constitution and diminishing labour rights.Footnote 37 These decisions were not complete reversals of norms, but the arguments used in them made it clear that the ongoing economic reforms had to be accomplished under certain restraints, given the social character of the 1979 Constitution. As one can imagine, these decisions – and the short period of time in which they were given – were perceived as a threat to the process of economic liberalisation. The magistrates were accused by the Executive and its sympathisers of acting with political intent and with an ideologically leftist bias.Footnote 38

These decisions were the TCG's first and last shows of courage. When Fujimori closed the Peruvian Congress with the support of the military in April 1992 he also intervened in the Supreme Court and terminated the TCG.Footnote 39 It is worth noting that, due to its recent activity, when the TCG was closed, 12 new acciones de inconstitutionalidad, mostly related to the market reform process, were awaiting a ruling. This is almost as many cases as it had ‘decided’ throughout its ten year history.Footnote 40

The failure of the TCG teaches us that pluralism may not be enough for the existence of political independence. In order to act independently, courts also need at least some institutional guarantees that allow them to ‘mirror’ this pluralism and prevent control from political actors. This case shows that two aspects appear fundamental: the rules of appointment of magistrates combined with the high vote requirement to declare laws unconstitutional. Ginsburg's insight on this point is correct, but he centres his discussion on what kinds of institutional design should provide, in the abstract, more independence for the courts. In order to complement Ginsburg's account we need a discussion of institutional design that stresses not so much how certain designs are better than others in the abstract, but how these designs relate to the political environment of the country and whether they allow for certain veto players to control the court.

Chronicle of a Death Foretold: the Failure of the ‘First’ Constitutional Tribunal (1996–2000)

Shortly after the 1992 coup, the Organisation of American States (OAS) adopted a resolution condemning Fujimori's actions, and recommending measures to democratise the country. In May Fujimori agreed to OAS demands and acquiesced to hold elections for a Constitutional Democratic Congress (CDC) in October that year (later the date was changed to November).Footnote 41 The CDC would act both as Constitutional Assembly in charge of drafting a new constitution to be approved in a national referendum and as Congress until the end of Fujimori's term in 1995.

The regime's main goal in the CDC was to include the possibility of Presidential re-election in the new constitution in order to allow Fujimori to run for a second term.Footnote 42 Fujimori supporters won a comfortable majority in the CDC (55 per cent), allowing them to draft the Constitution according to their interests. A pattern emerged in the CDC that would perpetuate until the fall of the regime in November 2000: a submissive majority in Congress – sometimes supported by minority groups – was used to gain control of horizontal accountability institutions in the country, with the exception of the National Ombudsman Office.Footnote 43

During the debates in the CDC, the discussion about constitutional justice focused on whether or not to maintain a constitutional court with abstract review powers. Responding to a first constitutional draft presented in January 1993, the majority in Congress rejected this option. Instead, a Constitutional Chamber in the Supreme Court with the capacity to produce stare decisis jurisprudence in particular cases was given the responsibility to act as constitutional guarantor. Giving the Supreme Court this responsibility would have been convenient for the interests of the regime, as it was seen as subservient – especially after being purged during the April coup. By the second constitutional draft, however, the Constitutional Tribunal (CT) was identified as the body in charge of abstract constitutional control.Footnote 44 This proposal finally achieved consensus.

Those articles of the 1993 Constitution referring to the CT reveal a very different institution to that of the TCG. Clearly, some of the design problems of the previous Tribunal were taken into consideration and corrected. The Constitution included dispositions stipulating that the CT would have seven magistrates, all of them to be elected with a two-third vote of the legal number of congressmen in the new one-chamber Congress. In this way, political negotiation was required to reach an agreement, making it more likely that the candidates elected would be independent ones. The CT rulings would derogate a particular law if declared unconstitutional and the magistrates were to stay in office for five years, with no possibility for re-election. The CT was to be the third and final instance in writs of individual rights of protection (hábeas corpus and amparo), after a first instance court and a Superior Court. Excluding some very particular situations, the Supreme Court no longer held a role in these constitutional actions, considerably reducing its adjudication duties. And in respect to access, the CT was even more open than the TCG had been.

How can we understand the pro-governmental majority's approval of a Tribunal with these characteristics? Why did they not opt for a weak Court, as suggested by Ginsburg's theory, and insist on placing this competence in the Constitutional Chamber of a submissive Supreme Court? One explanation is to give some of the members credit for having a real commitment to democracy and a separation of powers, and choosing to design a CT that (at least formally) seemed to protect minorities and allow for easier access. This is certainly true of some of the members of Fujimori's majority: two influential congressmen of the majority – Carlos Ferrero and César Fernandez Arce – actively supported the creation of the CT.Footnote 45 However, the truly powerful actors in the governing alliance were outside Congress (primarily the President, the military and the Intelligence Service) and most congressmen were faithful to these interests. Allowing for a CT with these characteristics would seem an unnecessary risk.

A second explanation is that, knowing that the Constitution was already widely criticised, the majority tried to reduce the points of contention that could assist a ‘no’ option win in the referendum process by which the Constitution was to be adopted.Footnote 46 The main contention against the Constitution, however, was related to changes in the previous economic model towards a market oriented one as well as other controversial issues, such as presidential re-election. The debate about the CT, even if important for civil society organisations and academics, seems not to have been a point of great contention or interest for most of the population.

A better explanation for the adoption of the CT can be found in the interest of the regime to make a credible commitment to international actors and the political opposition that the democratisation process was authentic. The CT was not the only body created in the new Constitution that was purported to be a means of fostering democracy. The Magistrates National Council was a new body in charge of appointing judges in courts of all levels, leaving no role for political branches in the process. A National Ombudsman Office, given the responsibility of defending human rights and preventing state abuses, was also established. Finally, diverse institutions were included to allow for the exercise of direct democracy in political decisions. All these measures were framed by the government as signs of a ‘real’ democracy, for the benefit of the people and against traditional party elites.Footnote 47 Moustaffa's ‘credible commitment’ explanation in the case of the Egyptian Supreme Court appears as a plausible one to explain the adoption of the CT, though the motivation of the regime was democratic rather than economic.

Given the power of hegemonic parties, such unilateral commitments constitute a weak mechanism for the creation of truly independent courts. As in the case of the TCG, the approved constitutional articles lacked a crucial dimension: the number of votes required to declare a law unconstitutional. When the CCD, now acting as Congress, voted on the first law regulating the work of the CT in January 1995, it became clear that the regime never had a real commitment to create an independent constitutional court that might control it. In this law it was stated that, in order to declare a law unconstitutional, six votes were required. Six out of seven votes is an almost impossible majority to reach, as the previous case of the TCG, in which the votes were merely six out of nine, had already demonstrated. In April 1995, President Fujimori was re-elected with a substantial proportion of the vote (64 per cent) and his party also won a majority in Congress (52 per cent). This majority became more powerful due to the extreme fragmentation of opposition groups and the easy cooptation, by legal and illegal means, of other minority parties.

The negotiations – to name the first group of judges – that followed lasted for more than a year after the 1995 election due to the lack of agreement in Congress, and especially owing to the efforts of the majority to name a controversial ex-minister of the regime, Augusto Antonioli, as a judge.Footnote 48 After the majority withdrew this candidate's name, five relatively prestigious judges were appointed. However, two candidates, proposed and defended as non-negotiable by the majority, were also appointed. These two members were clearly beholden to the regime and its military allies, one of them being an ex-chaplain of the Armed Forces.

Finally the Constitutional Tribunal commenced its work in June 1996, coexisting with an authoritarian government that progressively undermined institutions in the country. Even if, as predicted by pluralist theories, we could not say that the CT acted as an independent body, some rulings declaring laws partially unconstitutional were achieved in these first months. Most of these were related to issues of little relevance for the regime, but others did affect some of the ruling party's interests and some blatantly unconstitutional dispositions were dismissed. For example, some articles of a law giving special powers to intervention commissions in the judiciary and the National Prosecutors Office were dismissed (Case.1-1996-AI).Footnote 49 Also, decrees restricting the rights of pensioners adopted by recommendation of the Ministry of Economics and Finance were partially reversed (Cases.7-1996 AI and 8-1996 AI). Out of 16 acciones de inconstitucionalidad, presented from June 1996 to May 1997, the CT declared five partially unconstitutional.Footnote 50 It is worth noting that the legislative majority reacted to most of these rulings by submitting new laws that still maintained, with a different wording, the content of the original ones.

Crucial to explaining this failure, then, is the non-plural political environment during Fujimori's government. The CT lacked the necessary political support from other actors to challenge the majority. There were neither strong opposition parties nor independent constitutional institutions. Even an important contingent of the press was manipulated by the secret services. Also vital, the CT seemed incapable of overcoming the gridlock imposed by the two members elected by the majority when ruling on particularly sensitive issues. It would be unfair, however, to depict the CT as a body only restricted by two of its members. In just two of its 16 decisions during this period, the vote was five to two. In two other rulings we find three dissenting votes from those magistrates who were seen as more independent. However, in many of the cases in which the demands were rejected, all the magistrates voted in favour, most notably in the particularly sensitive case of an amnesty law passed by Congress affecting the perpetrators of human rights violations.

The major crisis for the CT emerged in 1997, when the Court was asked to review the constitutionality of a law allowing for a second re-election of President Fujimori. The Constitution allowed only two Presidential terms, but the government argued that it must be understood that Fujimori's second government was really his first one under the new Constitution. The case was so blatantly unconstitutional that even the Judges appointed by the regime found an excuse to evade participating in the ruling. This meant that, with only five members, no decision could be reached; by excusing themselves, those two judges rendered a ruling unattainable.

However, three of the members of the CT ruled against the law in January 2007 in a creative but very controversial way. They declared that this general law was not applicable in the ‘concrete’ case of President Fujimori. This meant that the justices were using their mandate to rule by simple majority in writs of individual rights protection, but in a process of acción de inconstitucionalidad, which refers to general laws. The other two members of the Court excused themselves from voting as well, mentioning previous opinions given publicly about the issue, so the three votes turned out to be a majority view. This strange decision caused confusion and an immediate reaction from the two magistrates loyal to the government. Some hours later, they wrote a second decision stating that the first decision was invalid, as the ruling did not attain the required six votes to declare a law unconstitutional. Both of these ‘rulings’ were published in the official newspaper, and the first decision was immediately disregarded by the official party.Footnote 51 Less than five months later (in May 1997), the three constitutional magistrates were impeached by Congress. The accusation was not directly related to their decision, but to an alleged procedural error while handling the case. The impeachment left the Court unable to review the constitutionality of laws.Footnote 52

Fujimori achieved re-election in a widely criticised electoral process in 2000. Even if Fujimori did not win a majority in Congress (42 per cent), his advisor, Vladimiro Montesinos, bribed elected opposition congressmen to become part of the Fujimorista majority. As a result, when the new government was inaugurated in July, Fujimori again controlled a majority in Congress (55 per cent). Just five months after this inauguration, however, Fujimori's regime fell abruptly due to corruption scandals and internal disputes.Footnote 53 Valentín Paniagua, a congressman from Acción Popular, was elected President of Congress in November 2000. Just a few days later, after Fujimori and his Vice Presidents resigned, Paniagua became President of a transition government in charge of conducting new elections for the following year. The new elections were won by Alejandro Toledo, candidate of Perú Posible, who had been the most serious challenger to Fujimori in the 2000 election. The government of President Alejandro Toledo commenced in July 2001. It was able to attain a narrow majority in Congress by allying with a smaller political group. Given the weak governing coalition and the existence of two other significant political groups in Congress – APRA and the right wing party Unidad Nacional – we can describe the political environment as pluralist.

Shortly after the fall of Fujimorismo, complying with a ruling of the Inter American Court of Human Rights and in response to what had been one of the most important banners against the regime, Congress reinstated the three impeached constitutional magistrates to their positions. Later a law was passed to allow them to preside until 2004, by excluding from their terms the three years they were out of the CT. Starting in January 2001, the CT set about reviewing constitutional demands.

In September 2001, Congress passed a law reducing from six to five the number of votes required by the CT to declare a law unconstitutional.Footnote 54 It is interesting to see how the same magistrates, including three of the four submissive magistrates that stayed in the Court after the impeachment of their colleagues, were able to rule on 20 constitutional demands in this plural environment.Footnote 55 Until May 2002, when the four magistrates that stayed in the Tribunal were replaced, they ruled four norms unconstitutional, and in another nine rulings they declared the norms partially unconstitutional. In many of these cases unanimous decisions of its six members were attained. As predicted by pluralist theories, the same magistrates that could not act as a body during their first years on the CT were now, in a plural political environment, able to exercise their review powers in quite an independent manner.

An Independent Constitutional Tribunal (2002–2007)

This last case shows how in a pluralist environment, coupled with better institutional rules that allowed this pluralism to be ‘mirrored’ in the CT's composition, this body has exercised its authority in an independent way. During President Toledo's administration and President Alan Garcia's second government (2006-present) the CT has become an impartial and influential actor in Peruvian politics. In May 2002, when the term in office of the four judges that stayed in the CT ended, four new magistrates were appointed. To attain the required two-thirds vote, the four majoritarian groups in Congress arrived at an agreement that allowed each of them to name a magistrate. There were some protests for what the press and minority political forces perceived as a mediocre and politicised election, and many predicted that the CT would start acting according to the interests of majority groups in Congress. This did not happen because in order to reach the two-thirds requirement for the candidates' appointment, parties were careful to nominate candidates that were acceptable to all of the political groups. Even if the four judges could be linked to a particular political group, they were individuals with personal prestige as politicians or lawyers. In addition, these four judges joined the three independent magistrates still in the court, which permitted a plural mixture of past and new magistrates. Once on the bench, these magistrates with different political and ideological views needed to compromise in order to reach their decisions. Political quotas, then, did not lead in this case to a submissive CT as feared, but to an independent one. From this moment on, the CT became an influential and independent actor in Peruvian Politics.

One competing explanation to that proposed here is that the enhancement of the CT's independence is the result of the difference between the new and old magistrates. It could be argued that the elected magistrates in 2002, as well as those elected in successive elections (2003, 2004 and 2007), are better than the previous ones in the CT and those elected for the TCG. From this perspective, the CT's independence is based on a meritocratic selection of judges rather than on political or institutional determinants. It is certainly true that the magistrates elected in this period were better qualified than the previous ones, although a review of their vitas shows that, in most cases, this difference should not be exaggerated: out of eleven elected judges elected from 2002 to 2007, only two can be counted as prestigious constitutional scholars and just one as an influential politician. This ‘meritocratic’ argument, however, is short-sighted as it does not take into account what led to the better election of judges in the first place. My contention is that a plural political environment also engendered this improved selection, as the required supermajority forced groups in Congress to negotiate and appoint constitutional judges who would be reasonably acceptable to all the parties. The independence of the court, then, can not be attributed to the personal credentials of the judges, but rather to the effects of political pluralism and better rules of appointment which make it more likely that the court will act independently. The pressure that the press and civil society organisations exerted on Congress for the elected magistrates to not be political cronies also helped to reach this outcome.Footnote 56

What evidence permits us to conclude that the CT has become an independent actor in Peruvian politics? Unlike the previous cases, opposition parties, authorities and other institutions with legal standing have come to see the CT as an impartial arena where legislation given by Congress or the Executive can be questioned. As Table 3 shows, the demands presented to the CT have increased considerably from 2002, in what demonstrates its growing legitimacy as a mechanism for dispute resolution.

Table 3. Number and Type of Processes Presented to the Constitutional Tribunal (1996–2007)

Source: Constitutional Tribunal (November 2007).

However, these numbers merely tell us part of the story. The best evidence of the CT's independence is that the tribunal has been able to rule in cases in which political branches or other constitutional bodies had strong interests. The range of cases decided by the CT includes issues concerning freedom of expression, access to information, social and economic rights, the jurisdiction of military courts, municipal matters, pension laws and constitutional reform, amongst others.Footnote 57 A decision given in January 2003 reveals the level of independence that the CT has attained. In what can be considered its most important decision to date, the case involved laws issued during the previous decade in the context of the internal war against terrorism, which dealt with such delicate issues as the past judgement of civilians by military courts.Footnote 58 The issue was brought to the CT by 5,000 citizens, many of them relatives of prisoners being held on charges of terrorism. The CT ruled many of the articles of these laws unconstitutional and, amongst other decisions, ordered new trials for all those that had been condemned by military courts. These included more than 800 cases of convicted members of the Shining Path and other subversive groups, and the ruling even applied to the leaders of these organisations. The decision, widely criticised by politicians and largely decried by the public, was nevertheless accepted, and new trials have got under way.

The CT has sometimes ruled in favour of political minorities in Congress. In other cases, it has supported the Executive in its claims against regional governments, or ruled in favour of local governments in their claims against Congress or the Executive. The Supreme Court and the National Prosecutor's Office have also obtained some institutional victories against Congress in the CT. In other instances, the CT has supported municipal governments and the Executive by reversing abusive and corrupt Amparo decisions granted by the judiciary, in an effort to bring more order to public transport, increase safety conditions in private businesses or prevent tax eviction. More recently, in 2007, NGO's, supported by the National Ombudsman Office, were able to attain a favourable ruling against a law approved by APRA and Fujimori's political group that aimed to control the use of NGO's international funds. The same actors that might lose a case in the CT on one occasion can achieve a victory in it on another, which makes the institution susceptible to both praise and criticism.

There are many other cases in which the CT risked a political and public opinion backlash, such as Amparo petitions presented by criminals or corrupt ex-officials in which the CT has ruled in favour of the plaintiffs. However, there are other cases in which, by overturning Congress and the Executive, the CT has been praised by the media and received the support of the public as a champion against widely unpopular political institutions. This growing confidence has made the CT include in its rulings admonitions to and severe criticisms of Congress and the Executive. In a very controversial case in 2005, for example, when two Regional Governments ‘legalised’ the coca leaf crop as part of their local traditional heritage, the Executive demanded that both norms be declared unconstitutional. The CT ruled in favour of the Executive and considered the regional laws as intrusive on its constitutional sphere, but also severely criticised the Executive and Congress for lacking a coherent national narcotic policy. Similar admonitions have been made in cases related to political corruption.

With this increase in activity, critiques of the CT have likewise escalated. The most common criticism in these years has concerned the Tribunal's rulings on economic issues, which – relying on the social character of the 1993 charter – have questioned some of the liberal economic reforms (pension reform, labour laws).Footnote 59 Critics have pointed to the scant technical knowledge of the CT regarding some of these issues. Politicians have also started to criticise the CT. Its harshest critic during the last years has been the current Minister of Defence and former President of Congress, Ántero Florez Araoz. Since 2006 Florez has denounced the CT justices for allegedly acting outside their constitutional jurisdiction.Footnote 60 Influential congressman of the incumbent APRA party, Mauricio Mulder, even proposed the elimination of the CT.Footnote 61 These skirmishes show how the CT counts on the support of a substantial proportion of the influential press, NGOs and professional associations. The fact that the CT was able to respond to Congress on more or less equal footing constitutes a novelty in the institutional history of the country.

Thus we can see how in a pluralist environment, and with certain changes to the institutional design concerning its operation, the CT has been able to exercise its constitutional powers in an independent way. As argued, this success is explained by the combination of political and institutional conditions. The need of a plurality of political groups to come to agreement through obtaining the number of votes required for the appointment of judges, coupled with a more reasonable vote requirement to declare laws unconstitutional, has led to an independent court.

Conclusion

The Peruvian cases, then, allow us to test theories about the emergence of independent courts. First, the decision to create the TCG was not accompanied by a commitment to assure its independence as expected by pluralist or ‘hegemonic preservation’ based theories. The diffusion of judicial power provides us with a better understanding of why a constitutional court was included in the 1979 Constitution. However, without other incentives, the belief that constitutional adjudication bodies are necessary to guarantee the respect of constitutional principles does not necessarily translate to a political commitment to create an independent court. Second, the TCG, though it existed in a pluralist environment, failed to exercise its constitutional duties due, mainly, to a lack of independence stemming from its poor institutional design. Two key aspects in this failed institutional design were the rules of appointment of justices and those of operation in regards to declare a law unconstitutional. The combination of these institutional features allowed the Executive to gridlock the court. Third, the case of the CT shows that it was in the interest of the authoritarian Fujimori regime to make a democratic commitment by including a formally strong constitutional court in the 1993 Constitution. After its creation, however, the regime delayed implementation until 1996, undermined its institutional design by giving the CT unreasonable rules with regard to its operation, and ultimately impeached three of its judges in 1997. This case confirms the crucial importance of political pluralism for courts' ability to act independently. Finally, after the 2000 democratic transition, under conditions of political pluralism and better institutional rules that ‘mirror’ this pluralism – an appointment process that requires political negotiation and realistic rules concerning the number of votes required to rule a law unconstitutional – the CT started to act in an independent manner.

What are the broader implications of these findings for the study of judicial independence in Latin America? First, the Peruvian cases confirm that, as concluded by diverse authors, judicial independence in the region is strongly linked to political pluralism.Footnote 62 The activity in the last decades of the Colombian Constitutional Court and the Brazilian Supreme Court indicate the importance of political pluralism to foster the activity of courts in the region. Both these courts have institutional designs that allow for a plural composition as well as reasonable vote requirements to rule laws unconstitutional. Conversely, judicial independence is not likely to emerge in countries where strong executives with dominant congressional majorities are in power, regardless of the court's institutional design. The current submission of the Venezuelan Supreme Court to Hugo Chavez represents the clearest case of this pattern. More recently, presidents Evo Morales of Bolivia and Rafael Correa of Ecuador have also clashed with, and defeated, the Constitutional Courts of their countries. These courts are currently irrelevant political actors in both countries.

Second, the failure of the TCG due to its poor institutional design opens an interesting avenue of research. In countries where political pluralism exists, an institutional design that does not ‘mirror’ this pluralism may be impeding -or restraining- the emergence of judicial independence. The case of the Mexican Supreme Court seems relevant in this regard. This court has a long history of submission to the dominant Partido Revolucionario Institucional (PRI). In 1994 the court gained considerable independence when a constitutional reform conceded it judicial review powers and institutional protections from majoritarian threats.Footnote 63 However, the vote requirement for the court to exercise its review powers and declare a law null and void is quite high: eight out of eleven votes. If just a majority vote is achieved the ruling only affects the parties in that particular case, but the law remains valid for the rest of the population. Even under conditions of political pluralism this high vote requirement seems to restrain the court from exercising a broader constitutional control.Footnote 64

A question that remains open is whether the Peruvian CT has achieved enough independence to ensure that it will remain influential in the future. In the US and Europe, we have seen how with courts in place and political actors using them to resolve their conflicts, a progressive process of legitimisation was initiated in which, carefully and case by case, courts entrenched their authority. Is the Peruvian case a good example that, as suggested by some commentators, we are currently witnessing a similar process by which horizontal accountability and the rule of law are enhanced in Latin American democracies?Footnote 65 Democracy certainly seems to be healthier than in previous historical moments in Peru. And it is true that the CT has already proven that it can be a competent institutional adversary in constitutional clashes. However, my analysis points to a much more cautious conclusion with regard to the entrenchment of judicial independence: the strong variation in judicial independence found in my cases over short intervals show how sensitive constitutional courts have been to changes in their political and institutional environment.Footnote 66 The independence of the CT is strongly related to a set of necessary political and institutional conditions, and any variation will very likely affect this independence. With weak political parties, a wide distrust of institutions and the threat of the emergence of a new plebiscitary outsider, as seen in the recent 2006 election, it seems too soon to conclude that the CT has achieved a strong position in Peru.