Introduction

More than ten years after the financial crisis, there is still much discussion about the challenges of European banking, such as the fragility of some large commercial banks, and the so-called doom loop between banks and sovereigns.Footnote 1 These challenges show not only that the banking sector and the functioning of the eurozone are closely intertwined, but also that the national level still matters in Europe. In 2020, the European market is still fragmented, while at the same time banking is a very global industry organized around major financial centers. However, a “common market” in banking was supposed to be in place since 1992, as a result of the ambitious plans designed by the European Commission (the Commission) chaired by Jacques Delors in the mid-1980s to relaunch European integration. Moreover, today’s post-Brexit concerns of the British financial industry about the risk of losing its passporting rights, allowing firms to conduct business in the European Economic Area without further authorization from each country, show the at least partial reality of this common financial market. Studying how commercial banks viewed the construction of this common market in banking in the 1970s and 1980s enables us to understand better what banks valued in this project, but also to highlight its partial dimension and the fact that this project was primarily political. This challenges the view that large companies tended to push for more integration.

The idea of a common market in banking in Europe is relatively old. The idea derives from the broader notion of a common market as set out in the 1957 Treaty of Rome establishing the European Economic Community (EEC or Community). The aim of the common market was to reproduce at the European level the same conditions as in a national market.Footnote 2 A common market in banking meant an environment in which banks could freely establish and provide services in the entire Community area, with comparable competitive conditions. The plans to establish a common market in banking, first designed in the mid-1960s, revealed serious challenges. Banking legislations and banking systems were very different, within the Community and elsewhere, and were an integral part of monetary policies at the core of states’ sovereignty.Footnote 3 For commercial banks, by the late 1970s, European affairs attracted at best indifference, sometimes distrust. A little bit more than a decade later, in the late 1980s and early 1990s, the situation had completely reversed, and big commercial banks were devising ambitious plans for adapting to the “horizon 1992” environment. The advent of a common market in banking was the result of work spanning from the late 1970s to the late 1980s, to which commercial banks, first reluctantly and then more enthusiastically, had been closely associated. The eventual result was not quite what was hoped by European policymakers, however, because national structures remained prominent in European banking markets.

Part of the literature has stressed the driving role of companies in the progress of European integration.Footnote 4 Some multinationals such as UnileverFootnote 5 or Fiat,Footnote 6 and some transnational business networks such as the European League of Economic Cooperation or the European Round Table of Industrialists, have been described as active supporters of European integration.Footnote 7 This article takes a different view and shows that the banking sector was not necessarily calling for European financial integration in the form of a common market in banking, partly because in the 1970s, their international interests focused elsewhere rather than on Europe.

In addition, historical studies of European integration have shown the involvement of multinationals since the beginning of European integration for a long time, but industry has received much more attention than banking.Footnote 8 Several studies have analyzed the responses to European integration from the perspective of specific sectorsFootnote 9 of a particular country’s business sector as a whole,Footnote 10 of competition policy,Footnote 11 or of transnational networks of multinationals.Footnote 12 However, little has been done on the world of banking, particularly for the late 1970s to 1980s era, despite this period being crucial in the relaunch of the integration process.Footnote 13 Furthermore, in European studies and European integration historiography in general, state-centered approaches prevail in the literature. Existing studies of the common market in banking and of the European financial single market, as much of the literature on the history of banking regulation, focus on the perspective of the public authorities,Footnote 14 or on the changes induced by European integration on “policy networks” in the financial sector.Footnote 15 Looking at commercial banks, and at business associations such as the British Bankers’ Association (BBA), the Association Française des Banques (French Banks’ Association, AFB), or the European Banking Federation (EBF or the Federation), this article sheds light on the critics, limits, and shortcomings the banking sector formulated about the Commission’s plans.

France and the United Kingdom both had an important banking system, but different profiles. The United Kingdom hosted one of the biggest financial centers in the world, was a late comer to the European Economic Community, and did not join the future Economic and Monetary Union. France, on the other hand, had an important, even if smaller, banking sector and a strong tradition of state intervention. Besides, its leading banks and, from 1982, its entire banking system were state-owned. Finally, France eventually joined the monetary union. Taking into account these two countries helps to understand better the respective role of national contexts and sectoral processes and avoid “exceptionalist” perspectives. Although international banking practices and strategies influenced how each individual firm positioned itself toward a possible European common market in banking, this article primarily focuses on banks’ collective political position through the responses of business associations and federations (the European Banking Federation, the British Bankers’ Association, the French Banks’ Association) and major French and British banks. Therefore, this article focuses more on politics than on commercial practices, although both dimensions influenced each other.

Based on a variety of French, British, and European Union archival sources, including the records of the British Bankers’ Association and of multiple commercial banks from both countries, this article examines how banks responded to the plans for a common market in banking. After a few preliminary remarks on the first initiatives of the European Commission in the 1960s and early 1970s, this article focuses on the period between the first banking directive in 1977, which represented the real starting point of the establishment of a common market in banking, and 1992, the official date when it was claimed the common market in banking would be completed. It shows that French and British commercial banks, although they favored European integration in general, were initially less supportive of European financial and banking integration in the form of a common market in banking for at least three reasons: They doubted the usefulness of such a move; they feared an increase in regulation; and their focus and business activities were domestic or global rather than European. They thus had a somewhat different perspective than the industrial sector, described in the literature as more supportive of integration. In some instances, they fiercely opposed the Commission’s plans. In the French case, banks tended to see the common market as a threat to their own position in their domestic market. However, British and French banks changed their minds in the mid-1980s and became more enthusiastic about it. The proposed regulations of the Commission had themselves changed and now coincided more closely with several recommendations formulated earlier by the European Banking Federation or by national associations. In addition, the political lead induced at the Commission level by Delors and Cockfield, the commissioner for internal market and former British Secretary of Trade in Thatcher’s government who drafted the white paper, created a new impetus. It was somehow more favorable to banks but also more difficult to oppose for them, as it went in hand in hand with more liberal-oriented economic policies adopted at the national level and emerging new standards at the global level, including the United States. Finally, the changes happening at the same time in the financial sector, with the aftermath of the international debt crisis and securitization underway, pushed banks to see European opportunities more positively. Overall, the persistence of national patterns, and the absence of a full-fledged European-wide regulatory and supervisory framework, prevented the emergence of a genuine common market in banking, but the European level became an intermediary strategic playing field for large banks, between national and global markets.

From Distrust to Interest

The first step toward a common market in banking was taken in 1965, when the Commission undertook a study of banking legislation in EEC countries with a view to harmonization.Footnote 16 The realization of a common market in banking implied harmonizing the rules governing the access to the activity of banking, and suppressing the obstacles to the freedom to establish and to provide services in the Community. A first directive issued in 1973, after eight years of work by the Commission, entailed the principles of freedom to provide services and the freedom of establishment. For the Commission, it was the first step in the establishment of a common market in banking. In practice, it was of minimal impact because of restrictions of capital movements and the absence of harmonization between banking legislations.Footnote 17 However, it revealed the complex relationship between harmonization and liberalization in the construction of a common market in banking, which would be discussed all along in the 1980s. For instance, even if the freedom to establish was fully liberalized, a German bank willing to set up a branch in Italy would probably have a regional authorization only, whereas an Italian bank opening a branch in Germany could operate in the entire German territory.Footnote 18 Freedom of establishment could thus create competition issues and therefore called for coordination between banking legislations. This lack of coordination is also a reason why the 1973 directive had little impact and triggered little reaction from banks, even though they had been involved in its drafting through the European Banking Federation.Footnote 19

There was thus a harmonization dimension and a liberalization dimension to the common market in banking. Harmonization meant some degree of convergence between banking legislations. Liberalization meant the suppression of restrictions to the establishment or the provision of services in the Community, which could take many forms, from restrictions based on nationality to special requirements for foreign banks or controls on capital movements. Originally, harmonization was considered as a stage toward the unification of banking legislations in the EEC, as explained by Charles Campet, in charge of the banking division at the European Commission in 1974.Footnote 20 The Commission conceived harmonization as a necessary complement to the suppression of restrictions to free banking in the EEC. In the context of widely heterogeneous banking legislations in the EEC, the suppression of restrictions could create distortion of competitive conditions, in particular because of the multiplicity of legislations to comply for banks. These measures were enacted through directives, which were legally binding regulations requiring member states to transpose them in their national regulatory framework. However, harmonization proved much more difficult to achieve than was originally hoped for by the Commission. In particular, the British banks and government considered that if their system, traditionally informally regulated, was to be harmonized with that of the continent, that would amount to an increase of regulation and would undermine the attractiveness of London as an international financial center. As will be explained in the next pages, the Commission shifted its overall regulation philosophy from the 1970s to the 1980s, from an ambitious harmonization program (failed first banking directive proposal), to a more gradual harmonization approach (first banking directive), and finally to an approach based on mutual recognition (second banking directive).

For commercial banks, a common market in banking was not a clear and exciting idea, and many of them were losing their interest in Europe during the 1970s. In 1970, during a meeting between delegates from the EBF and the European Commission, Paul Fabre, from the Association Française des Banques, asked what exactly did a common market in banking mean, and he was skeptical about the need for harmonization.Footnote 21 He stated that banks could already establish in other European Economic Community countries if they wanted. In the early 1970s, European activities of big commercial banks concentrated on the setting up of banking clubs, a kind of flexible, cooperative arrangement between a few chosen partners. As these clubs were limiting competition between their members, they were somehow at odds with the idea of a common market in banking, which, on the contrary, aimed at enabling banks to freely compete on the EEC countries’ markets.Footnote 22 Even the Commission’s officials, such as Marcel Campet, recognized that the 1973 directive was esoteric and included subtleties of extraordinary sophistication.Footnote 23 British banks followed European affairs more closely than French banks, but this was so because they were distrustful of European institutions and its style of regulation. In 1979, an internal note at Société Générale mocked the “administrative machine of the EEC” and its wish to pursue international business conferences in which European banking clubs had been involved in 1977 and 1979.Footnote 24 The European banking club of the Société Générale and Midland Bank, European Banks’ International Company (EBIC), decided in June 1979 to limit as much as possible its involvement in European Economic Community initiatives.Footnote 25 In 1980, EBIC was relating its own disappointing results and history to the lack of progress in European affairs compared to the 1960s: “The probability that the political, economic and monetary conditions, necessary to create a large European unit, would be fulfilled, receded ever further beyond the horizon, while at the same time a genuine desire for such a unit had disappeared from the minds of our banks’ top management.”Footnote 26

At the turn of the 1980s, the idea of a common market still left banks very skeptical. However, most important, their international activity centered more on lending to developing countries through the Eurodollar market: Their international concerns were more global than European.Footnote 27 An international financial center such as London, more than a possible regulatory place such as Brussels, attracted the banks’ attention.Footnote 28

The 1977 first banking directive was a response to the initial challenges posed by the 1973 liberalization directive and intended to harmonize the conditions for conducting banking activities in Europe. Its first draft had been fiercely opposed by the British Bankers’ Association, who did not want to change their informally regulated banking system.Footnote 29 Besides, the economic and monetary crisis in 1973–1974 hampered European efforts toward convergence of banking legislations.Footnote 30 The directive eventually issued was therefore of modest importance. For the French, it implied almost no change at all in the already existing legislation, partly because they already had the licensing requirements that the directive was rendering mandatory, and partly because they were already used to a formally regulated system.Footnote 31 For the British, the introduction of a licensing system was the only substantial change but had actually been favored by the BBA as a way to prevent another secondary banking crisis.Footnote 32 The BBA saw it as a means to prevent access to the banking profession from imprudent “cowboy” banks.Footnote 33 The 1979 UK Banking Act would actually go further than the EC directive, as British banks started to doubt its efficiency.Footnote 34 Once enacted, the first banking directive did not trigger much reaction from bankers, even though they had strongly influenced it, because they considered it more as a starting point than as a move with concrete impact.Footnote 35 The first banking directive indeed called for other directives in various fields of banking, which would be the story of the 1980s. Among those projects, the plans for a second general directive complementing the first one emerged quite early.

In January 1980, the assistant secretary of the BBA circulated to the BBA’s executive committee a discussion paper prepared by the Inter-Bank Research Organisation (IBRO) on the Commission’s plans for a common market in banking.Footnote 36 The main point of the paper, which represented the British commercial banking sector’s view, was to wonder whether harmonization was worth the costs it entailed in terms of increase in regulation. It stressed that the Commission should focus more on removing the real obstacles in intracommunity banking, in particular exchange controls, withholding taxes on bank interest paid to nonresidents,Footnote 37 and the obstacles to free banking existing within each country, such as the privileges granted to specific financial institutions in the agricultural sector or elsewhere.Footnote 38 Furthermore, it stressed that there existed national and structural barriers to banking integration not directly linked to banking legislation, such as language, the legal system, taxation, currencies, the ownership of local banks, the degree of concentration or specialization in banking, and the closeness of the relationship between local banks and their customers. It further argued that the actual degree of interpenetration was quite limited, foreign EEC banks totalling less than 2 percent of personal deposits in France and less than 2 percent of total assets in Germany, a country where banks from the United States were more numerous than banks from other EEC countries.Footnote 39 Even in London, where foreign and EEC banks were well established, activities were mostly offshore, and IBRO estimated that foreign EEC banks had not much more than 2 percent of total sterling bank lending to the UK private sector, way behind American banks. In this context, the Eurodollar market had played a role of compensation of a poorly integrated banking and capital market in the Community. However, IBRO considered it would be difficult to change the situation in the retail banking area and suggested that the Commission should focus on other areas. This situation probably explained why the banking sector was less openly supportive of a common market in banking, even if it was supportive of European integration in general, than the industry: In January 1981 the Confederation of British Industry (CBI) had published a report in which, despite also urging for a reordering of harmonization priorities, it expressed its full support to the European Economic Community, which was the destination of 42 percent of British exports.Footnote 40 At least in the British case, the business derived from European activities was more substantial for the industry than for banking.

In October 1981, officials from the Directorate General (DG) XV of the Commission, responsible for financial institutions and taxation, informed the BBA delegates of the Commission’s plans for a second banking directive.Footnote 41 DG XV wanted to have banks’ views on what should be included in such a directive. The BBA delegates considered that the Commission wanted to issue new regulatory elements in order to advance its integration agenda. Businesses could thus be a political resource for gaining legitimacy in this perspective. Returning from a visit to the Commission in March 1981, a BBA delegate wrote: “The impression was gained that DG XV were rather searching for tasks in respect of banking. When it was mentioned that the Federation hoped to put forward a paper explaining ways in which the banks felt the Commission might move forward, it was immediately welcomed and regarded as particularly relevant at the start of a new Commission.”Footnote 42 The second banking directive would aim to refine the areas touched by the first one, in particular, the notion of own funds.Footnote 43 Indeed, the first banking directive required banks to have “adequate minimum own funds” without providing a precise definition of it.Footnote 44 Also, the project of the second banking directive would aim at removing the remaining obstacles to the establishment of representative offices and branches in other member states, such as local capital requirements in Germany. On the occasion of their visit to the Commission, Troberg, Banking Advisory Committee secretary and member of DG XV, told the BBA delegates that he welcomed banks’ views on what else should be included.Footnote 45 This invitation from the Commission toward banks to be more active highlights that the common market in banking was politically driven. In this perspective, businesses could be used as a resource to mitigate governments’ objections, a strategy that had long been used by the Commission.Footnote 46

In December 1981, the Commission issued a first document, titled “Plans for a Second Council Directive for Credit Institutions” (XV/253/81).Footnote 47 Overall, banks severely criticized the preliminary proposals for a second banking directive.Footnote 48 The BBA was not very enthusiastic about the consultative paper and considered that “harmonisation within the E.E.C. should seek only to eliminate significant obstacles to integration; harmonisation should not be pursued as an end in itself and should aim at providing only a minimum level of regulation.”Footnote 49 It also added that “some of the Commission’s proposals appear to represent an unnecessary and undesirable intensification of the regulatory process.” The EBF was along the same lines.Footnote 50 The BBA, in particular, criticized the attempt to impose requirements for branches to have their own capital. However, an internal note written in preparation for a visit in October 1982 stated that “the B.B.A. wholeheartedly supports the Commission’s avowed long-term aim to establish a common market in banking with minimal regulation by the home country authority.”Footnote 51 In sum, two different views of the common market in banking were emerging: that of freedom to operate, and that of common rules. Although all recognized that liberalization and harmonization somehow had to go together, the Commission pushed the second element, and commercial banks preferred the first one. On the French side, their limited interest in European affairs also related to different issues than those expressed most vocally by the BBA: In particular, the wish to maintain their strong domestic positions was not triggering much excitement about the advent of a European common market in banking, but also the shock of the 1982 nationalizations made them focus on domestic affairs.Footnote 52

Even if a diversity of views existed within the Banking Federation, the EBF gave clear preference to the liberalization of all the aspects of banking in Europe, from establishing in another country to capital movements. This was particularly the case of British banks, who considered their country as less regulated than other EEC countries and did not wish to see harmonization on the continental level. British banks perceived harmonization as an attempt to create new regulations. Most important, the EBF saw harmonization as a threat to the national systems in place, which banks did not necessarily want to change. The views of the banking community resembled, to some extent, those of the industry, in the sense that the Union des Industries de la Communauté Européenne (UNICE) had also stated harmonization should only be pursued where there was an identified need for it.Footnote 53 However, UNICE recognized the importance of harmonization for the development of the EEC to a larger extent than the EBF.

Very progressively, the position of the EBF was evolving, however. In 1981, the European Banking Federation issued a discussion paper drafted by the BBA and aiming at “a more positive and constructive approach by the European banking community to the Commission’s activities.”Footnote 54 The paper, greatly influenced by the 1980 IBRO study previously mentioned, stressed that local supervisory requirements still represented serious barriers to branch opening in a member state and that absolute harmonization was not a satisfactory solution. It suggested two particularly important items: first, that central banks from member states should trust each other enough to authorize the establishment of branches from foreign banks without any other formalities than those existing in the home country; second, that there should be enough harmonization so that banks from one member state would not be favored compared to the banks from other member states.Footnote 55 The European Banking Federation explicitly prioritized the reduction of regulation over harmonization, which was to be pursued only when necessary for the removal of significant obstacles to integration. National differences were to be preserved. The paper listed several obstacles, the first of which were barriers to transborder flows of capital and income, such as exchange controls.Footnote 56 The proposal that central banks recognize each other’s procedures was close to the mutual recognition principle, which was coming out of the 1979 Cassis de Dijon case and would later become the integration philosophy of the Commission, even if a reference to this case has not been found in the records of that time.

Between 1982 and 1985, the Commission focused on own funds, which were partially linked to a common market in banking, as harmonization in this area was meant to ensure equal competition, but also had to do with other concerns such as financial stability. The observation work conducted in this area by the Banking Advisory Committee, a new EEC expert committee created by the 1977 directive, attracted all the attention, and its progress was instrumental in any development in the second banking directive. The topic of own funds was increasingly under pressure from the work conducted in the same area at the Group of Ten level at the Bank for International Settlements, within the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, which included major players such as Japan and the United States.Footnote 57 Little by little, the issue of own funds became the subject of a directive in itself.

In parallel, the Commission issued in 1983 a document enclosing an ambitious plan for furthering financial integration in Europe.Footnote 58 This document was, here again, not strictly speaking about the common market in banking but addressed issues related to it, such as the liberalization of capital flows. Overall, the EBF welcomed the paper and its objectives. The Banking Federation supported the proposals for examining whether restrictions on capital movements should be allowed to continue.Footnote 59 The AFB had been asking for the removal of exchange controls for a long time and very much favored the removal of capital controls altogether.Footnote 60 When the paper addressed the harmonization of banking regulation, the Federation supported the aim of a gradual emergence of a common market in banking but stressed the practical difficulties involved. Finally, the EBF argued against the use of uniform banking ratios such as solvency as a regulatory tool and disputed the argument that an increased competition would reduce borrowing costs, stating that international banking was already very competitive.Footnote 61 However, for European commercial banks, the Commission’s ideas were going in the right direction.

From Interest to Enthusiasm

The issuance of the 1985 white paper and the following signature of the Single European Act introduced major changes, as they set a precise regulatory agenda in the field of banking, even though those plans had been devised for several years. Shortly before the white paper was issued, the ambitious plans of the Delors Commission were known and supported by British banks. In a letter to another member of the BBA in preparation of an upcoming meeting with the head of the British delegation in Brussels in March 1985, Robin Hutton, from the BBA executive committee (and a former Commission official), stated that the BBA should support the political objectives of the Delors Commission.Footnote 62 He considered that “the banks should support all efforts of the Commission to reduce barriers to cross-frontier services business, no matter whether the immediate beneficiary is insurance, investment or any other service: all freedom of services directives are valuable building blocks against national protectionism and towards a common market in banking and finance.”Footnote 63 More particularly, Hutton argued that the future of banking was less about opening branches than about technological innovations and international electronic operations, which did not require a physical presence in another country but the freedom to provide services from the home country. Therefore, the BBA welcomed the freedom to provide the services principle encompassed in the common banking market plans, as well as, more generally, the new Delors Commission’s reported intention to focus on the internal market and on service industries. Hutton explained that British banks had changed their mind about the EEC: “There has been a pretty fundamental change in the outlook of the British banks over the recent past, of which Sir Michael should be aware. From a (2) posture basically negative to EEC initiatives, the BBA has moved towards a more open-minded approach on such matters as banking legislation, credit information exchange, accounting standards, and monetary cohesion.”Footnote 64 This change of opinion from the British banks resulted from the change in the international economic environment, marked by the international debt situation in many developing countries’ markets and the securitization of the banking industry. This context induced a sharp decline in international lending, and made regulatory changes in the area of securities more important, and therefore the new political impetus given by the Delors Commission more welcome.Footnote 65 However, the change of approach by the Commission, from harmonization to mutual recognition, was also a major reason why banks, who had themselves called for such a change, became more supportive of a common market in banking. A few days after the white paper came out, Tom Soper, EEC advisor at Barclays Bank wrote to the deputy chairman, Quinton: “Lord Cockfield is in the news as he has just issued a Commission White Paper on a single internal market in the Community. This is obviously something we shall be discussing with him over lunch on 24th September, 1985.”Footnote 66 A note was then circulated in August 1985 to about ten members of staff at the European Economic Community Unit in Barclays to ask for their views on the white paper so that these views could be transmitted to Tom Soper before his September meeting.Footnote 67

The banking community welcomed the direction taken by the white paper. In its comments from November 1985, the EBF welcomed the white paper and vigorously supported its objectives.Footnote 68 It pointed out that most suggested measures were not new but supported the political impetus of the document. It reaffirmed its preference for liberalization over harmonization and stressed that liberalization was a necessity for furthering the integration, while the need for harmonization should not be exaggerated. Precisely, the white paper claimed that harmonization should not always be considered as a necessary first step, as was the case in the past, in particular in the field of banking supervision.Footnote 69 This point reflected the Commission’s move away from harmonization toward mutual recognition, and was very close to the 1981 EBF paper suggesting that authorities from member states should trust each other’s authorization procedures in order to facilitate banks’ establishment in member states countries. Therefore, this part of the white paper was particularly welcomed by the EBF.

The white paper contained plans for the removal of exchange controls and liberalization of capital movements, which were not solely related to the common market in banking as they were much broader in scope, but which triggered internal discussions at the EBF on the respective balance of harmonization and liberalization. Overall, the EBF vigorously supported the liberalization of capital movements. In June 1986, Robert Pelletier, a former member of the main French employer organization (Conseil national du patronat français, CNPF) and secretary general of the Association Française des Etablissements de Crédit,Footnote 70 considered the European move as a major change for the French financial system.Footnote 71 Although this change was not unwelcome, as it pushed France to reduce its strict control on banks, Pelletier regretted that the French tradition of state intervention would penalize French banks in international competition.Footnote 72 This explains why not all bankers agreed on the rhythm and conditions of the planned changes. During the October 1986 meeting of the EBF, two main opinions were expressed on the liberalization of capital movements.Footnote 73 Those countries (France, Italy, Spain, Ireland, Greece) where controls were still in place insisted upon a gradual removal of existing regulations on capital movements, whereas others (United Kingdom, Belgium, Germany, Portugal) favored rapid progress, stating that the areas where harmonization was necessary were limited.Footnote 74 A general concern of the EBF was to ensure fair competition. Together with the liberalization of capital movements, the EBF gave priority to the harmonization of taxation, as the freedom of capital flows was expected to increase international competition. French banks were particularly keen on stressing the urgency of this matter but were opposed by British, Luxembourg, and German banks.Footnote 75

To some extent, in any case, commercial banks were changing their minds about the EEC initiatives in the field of banking because these were getting much closer to their own demands: liberalization of capital movements (even though there were different opinions concerning the rhythm of this liberalization) and mutual recognition of a national regulatory system as a way to avoid the harmonization approach which had been that of the Commission until then. An additional difference to the 1970s proposals was the cumulation of many planned directives in the field of banking and finance: The proposed changes concerned the liberalization of capital movements, and the freedom to provide services, and to establish, banking, insurance, and capital markets operations more or less at the same time. This showed the determination of the Commission to move forward with the completion of the internal market. Given the new support of several member states, and in particular of the French government, to this ambitious program, commercial banks could only realize that the political impetus at both EEC and national level was here and that they could not escape it.Footnote 76 The strong support of the government was particularly important for redirecting French banks’ interest toward Europe. For instance, according to Barclays’s observers, the Crédit Lyonnais’s ambitious European strategy was also a decision of the French Treasury and a substitute to privatization.Footnote 77 Quite logically, because EEC commercial banks had themselves called for some of the proposed changes, and because it was following an international trend toward liberalization, they chose to embrace it.

Without the section on own funds, which had become the subject of specific directives, the second banking directive could focus on the conditions for opening branches and conducting banking activities in the Community. The first proposal for a directive was issued in February 1987.Footnote 78 It encompassed the change in philosophy from the Commission, departing from an objective of total harmonization to the mutual recognition of each other’s regulatory framework, and gave a prominent role to home authorities in the control of their banks. The paper proposed some harmonization in the definition of activities subject to supervision, in authorization procedures for opening a branch, and for the suppression of a minimum capital requirement for branches.Footnote 79

In February 1987, C. J. Oort, the Dutch president of the EBF, introduced the official comments of the EBF on the second banking directive proposal by saying that it “entirely agree[d] with the main thrust of the directive.”Footnote 80 The EBF had become enthusiastic about the plans for a common market in banking. C. J. Oort stressed a few issues, however, saying that the implementation of the principles of the white paper required “a sufficient degree of harmonisation of solvency ratios, and free access by credit institutions to the same activities in all Member States.”Footnote 81 He also stressed that the problems of “approximation of tax legislation and convergence of economic and monetary policies” had to be resolved to prevent distortions of competition. In defining the scope of activities covered by the proposed directive, the Commission suggested shifting from an institutional to a functional approach, because of the ongoing changes in banking activities and the blurring of the distinction between different financial activities such as banking, insurance, and securities operations. This meant that the directive would apply to identifiable types of activities instead of specific institutions.

The banking sector was anxious to preserve its independence from industry in its negotiation on the second banking directive. When UNICE set up a financial services working group, which was expected to express views on various initiatives of the Commission, including the Second banking directive, it was badly perceived. An internal note at Société Générale stated that “one can fear that compromises imposed by the manufacturing sector too much influences the views of this working group.”Footnote 82 The AFB and the EBF took the view that UNICE was legitimate to represent the services industries in the GATT (General Agreement on Tarrifs and Trade) discussions, but could not become the Commission interlocutor on banking matters, which were the exclusive competence of the Banking Federation.Footnote 83 In general, the banking community wished to keep some degree of autonomy from other economic sectors as a way to preserve its bargaining power, especially on technical matters.

The scope of the directive remained controversial within the EBF. The BBA had a different view from other national associations. The latter agreed with the Commission to have a wider definition than the one of the first banking directive because they wanted to subject banks’ competitors to equivalent Community regulation. The BBA, on the other hand, noted that “the advantage of the 1977 definition when combined with the List of services is that banks will be entitled to conduct a wide range of business across the EEC whereas their competitors will not.”Footnote 84 The BBA also had an issue with the list of activities covered by the directive, as it included types of investment business such as securities business. This would allow European banks to undertake these activities in the United Kingdom without being authorized by specific institutions such as the Securities and Investment Board or the self-regulatory institutions. On the other hand, it would benefit British banks operating in Europe, and the BBA believed that on balance, the British banks would gain from this list. However, the British government was not clear about this issue, to which the BBA raised attention by a letter to the Bank of England.Footnote 85

At its October 1987 meeting in Athens, the EBF discussion on the second banking directive focused on a recent change in the Commission’s proposal excluding securities business from the list of activities associated with banking. These activities would, therefore, not be subject to mutual recognition.Footnote 86 This move triggered the protest of the EBF because banks’ securities business was sharply growing at that time, and regulators were striving to adapt their regulatory framework accordingly, sometimes incoherently. The Federation agreed to press the Commission, which eventually accepted, to include securities business in the mutual recognition list, and to appeal to national authorities to rationalize their attitude in the field.Footnote 87 It also decided to bring up the matter with the Basel Committee meeting at the Bank for International Settlements, because discussions there involved the United States and Japan and securities business was best managed at the global level.

The main controversial area of the second banking directive concerned a reciprocity clause dealing with the conditions for authorization for banks from non-EEC countries. Both the British banks and government opposed the reciprocity clause, as they feared it would damage the attractiveness of the City as an international financial centre. Continental banks were more supportive and sometimes strongly in favor of this principle.Footnote 88 The French banks were particularly favorable to introducing such a clause in order to obtain leverage over other countries. They played an important role in convincing the French authorities to bring the matter to Brussels, in particular through a report on the question by De Croisset from the Crédit Commercial de France.Footnote 89 In April 1987, the AFB circulated a note on the matter to the Board and Central Committee of the European Banking Federation.Footnote 90 The French association stated that the increased competition to be expected from the 1992 completion of the single market would also occur vis-à-vis non-EEC countries, and would not concern authorization procedures only, but banking activities in general. It particularly pointed out the separation between commercial and investment banking or wealth management in several non-European countries, whereas continental Europe often had universal banks. These universal banks often encountered difficulty in accessing these different types of banking activities. This was particularly the case in Japan, where many French banks complained that they faced several obstacles in their commercial banking activities. In particular, the AFB considered it was extremely difficult and slow for banks that had a commercial banking license to obtain an investment banking license as well. The AFB was also concerned about recent revelations in the press, according to which the Japanese authorities delivered investment banking licenses in Tokyo in strict accordance to the number of licenses pursued by Japanese banks in Europe.Footnote 91 Until then, reciprocity issues had been resolved on the basis of bilateral agreements, but the AFB believed European banks would have more leverage if these negotiations were carried out at the Community level. Finally, the AFB considered that it was time for the EBF to raise the attention of the Commission to this issue because new negotiations at the GATT level were starting and were for the first time including the sector of financial services.Footnote 92 The access to the European market by non-EEC banks was thus an important and controversial element of the common market in banking in construction.

The reciprocity clause was rigorously opposed by both the British banks and the British government. During a meeting of the City Liaison Committee in July 1988, Sir Jeremy Morse, president of the BBA and of Lloyds Bank, stated that “the BBA were at one with the UK Government in seeking clear deregulation of markets and in seeking to avoid the erection of barriers round the “European Community.”Footnote 93 Sir Nicholas Goodison, chairman of the International Stock Exchange, agreed with Morse and “expressed deep concern about the line the European Commission were taking on the question of reciprocity.”Footnote 94 The question of reciprocity became a highly political one. At the September 1988 meeting of the central committee of the EBF, the AFB stressed that this concern was particularly acute in the sense that major Japanese and American banks were already established in the EEC and would, therefore, benefit from both mutual recognition and freedom to provide services within the EEC.Footnote 95 The United Kingdom was the only country categorically opposed to the reciprocity clause.Footnote 96 According to a French banker from the AFB, the battle on that question was resolved at a very high level.Footnote 97 Eventually, a flexible approach to reciprocity was adopted: Member states’ authorities had to inform the Commission of authorizations and majority participation in Community credit institutions granted to non-EEC banks, but no strict limitation was enacted.Footnote 98

From Enthusiasm to Action

The second banking directive was eventually issued in December 1989, while several other directives had already been issued or were issued around the same time. In June 1988, the liberalization of capital flows had been enacted, and in April and December 1989, the definition and requirements of banks’ capitalization were harmonized by two directives. Other directives had been adopted or were being discussed at the same time in the field of insurance and capital markets, which were growing areas of activities for banks, too. The main difference with the first banking directive was that the mutual recognition principle had practical implications. In addition, this second directive was part of a set of several directives, which, together, implied serious change for European banking, whereas the first one had very limited practical consequences. The commercial banks had therefore been much more involved in negotiating their details to defend their interests. Combined with the liberalization of capital flows and common capital adequacy rules, the second banking directive enabled banks to establish freely in the Community through the principle of mutual recognition, but also to freely provide services without having to be physically present in another country, in a more homogeneous competitive environment. That was the cornerstone of a common market in banking, even though this market was far from complete. The objective to implement most of these directives by 1992 triggered much discussion on the “Horizon 1992.”

However, even if the EBF had become much more supportive of European efforts in the financial sector, the enthusiasm of French banks was still partly hindered by the fact they felt threatened by the advent of the common market in banking: They considered that the liberalization of capital movements or the establishment of harmonized capital ratios would favor the incursion of foreign banks.Footnote 99 In an interview given in January 1993, the European delegate of Paribas, Charles Hammer, declared, “Why would a company protected by a highly regulated market want to risk the dive into the unknown and the danger of competition?”Footnote 100 What made them accept the process was the direction taken by their own authorities, who had firmly committed to the liberalization of capital movements and the opening of financial markets, together with the opportunities French banks started to see—slowly, according to Hammer—in European integration, and the desire to be not be seen as lagging behind in international banking. In interviews given in late 1992 and early 1993, French bankers from AFB, Paribas, and Crédit Commercial de France all stressed that French bankers had long distrusted the Commission’s initiatives, had lacked involvement in European Economic Community matters, or had been slow to react.Footnote 101

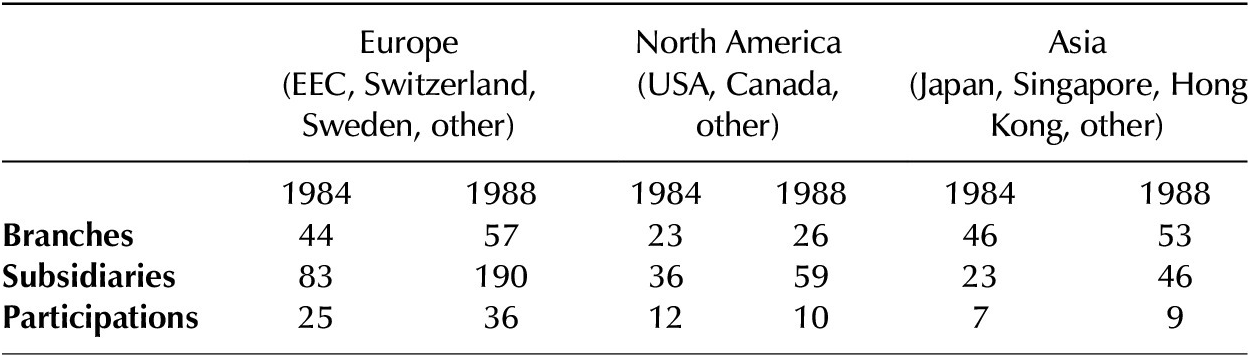

The perspective of a single banking market for 1992 became a widely debated topic in both France and the United Kingdom, particularly from 1988 onward. In both countries, banks and authorities expected increased competition and conducted several studies to examine the respective strengths and weaknesses of their banking system compared to those of other member states. In France, the perspective of the single market in 1992 triggered a sharp surge in banks’ establishment in other countries from the EEC. As shown in Table 1, by 1989, Europe was by far the most popular area where French banks had increased their presence. This move reflected the internationalization strategy of many banks, not only in France, often relying on new acquisitions of subsidiaries and mergers.Footnote 102 Not all credit institutions favored the coming single market to the same extent, however: The savings banks, in particular, were wary of excessive competition and of losing their local links with their clients and their local identity.Footnote 103 The Savings Banks Group of the EEC, therefore, advocated cooperation as a way to cope with the 1992 challenges.

Table 1 International expansion of French banks between December 31, 1984, and December 31, 1988

Note: Adapted from BFA, 1749201013/5, “Présence des banques françaises à l’étranger et des banques étrangères en France,” note from the French Banking Commission, November 27, 1989. Branches: foreign establishments legally depend from the home institution. Subsidiaries: foreign establishments legally independent from the home institution. Participations: holdings of capital in a foreign banking institution.

In London, the regulatory implications of the 1986 Single European Act prompted a revival of the City Liaison Committee, a coordination body chaired by the Bank of England and meant to defend the interests of the City, which had been on standby for a few years.Footnote 104 In January 1988, the governor of the Bank of England wrote to the members of the City Liaison Committee about the implications for the City of the proposals for the completion of the internal market by 1992: “One step which I believe must be taken very soon is to take detailed soundings of a large number of City practitioners.”Footnote 105 The governor reckoned that much attention had been given recently to domestic issues because of the “Big Bang” in the financial markets in late 1986.Footnote 106 However, he considered that the time had come for a careful examination of the challenges and opportunities of the completion of the internal market, and how the City could ensure to maintain and reinforce its status of international financial center. His remarks pointed to another challenge for European banking integration in Europe: the competition between financial centers. If London was by far the leading center in Europe, France was striving to make Paris supplant or rival London, and so was Frankfurt.Footnote 107 However, international financial centers had to be global, not European, to be competitive. Financial integration in Europe thus encompassed close links with globalization. In the field of banking supervision, the Bank of England governor was particularly worried that Community legislation reflected the legalistic approach of most continental European countries, as opposed to the more informal approach of the United Kingdom.Footnote 108 Still, the participants in the City Liaison Committee meeting overall supported the renewed activity of the Commission in the financial sector. Jeremy Morse thought “it was difficult not to be excited by the sense of movement” and “overall … saw the creation of the single market as a ‘plus sum’ game.”Footnote 109 A questionnaire, circulated to the British banks for the occasion, revealed different opinions and interests toward the completion of the internal market, however.Footnote 110 The report noted that domestic-oriented banks still had little interest in Europe and had not really considered the effect of mutual recognition on their activities in the United Kingdom. The British banks were therefore split between those with European plans and those intending to stay on a UK-based business. This feature was not specific to the United Kingdom.

The strategic reaction of big commercial banks was the third stage in their response to the advent of a common market in banking, after indifference and enthusiasm. If these strategies differed from one bank to another, by 1987, and even more by 1988, all big banks were taking measures to adapt to the “Horizon 1992.” The cases of Barclays and Crédit Lyonnais, who were competing, together with Deutsche Bank, for the leadership on the European market, can illustrate a few key elements of big commercial banks’ response to the advent of a common market in banking. First, archival evidence shows that business opportunities were not so clearly assured as the Commission wished to see: Both Barclays and the Crédit Lyonnais identified few areas where expansion could be pursued.Footnote 111 The Lyonnais stated that Europe tended to be already “overbanked,” although both Barclays and the Lyonnais recognized that internal expansion, that is the development of the banking network through direct establishment of branches or creation of wholly owned subsidiaries, was risky and costly because it faced the local characteristics of markets. Even the Crédit Lyonnais, which claimed to be the most European of the French banks with the largest European network, and depended heavily on foreign establishments for its development because of its strong retail banking profile, reckoned that physical expansion in Europe was difficult and risky.Footnote 112 Most banks preferred to acquire a participation in a joint venture with a local partner, a fact confirmed by Umberto Burani, head of the EBF, in 1992.Footnote 113 The market for large corporate clients was already global, while that for small and medium companies was considered by Barclays as too locally rooted to provide access for foreign banks.Footnote 114 Banks recognized the importance of the coming common market in banking, but in some precisely identified areas only, depending on each bank specialization.

Second, both Barclays and the Lyonnais repeatedly stressed the role of the global level for international strategies. Barclays, in fact, considered Europe as a platform for global competition.Footnote 115 In September 1987, even after the Single European Act, its international committee stated without any hesitation that “preference for any major merger or acquisition was the United States [over Europe] because of common language, the coherence of the U.S. market place and its links with the Far East.”Footnote 116 Haberer, head of the Crédit Lyonnais, stated in October 1990 that “no big bank will sacrifice its global and worldwide strategy for its European strategy.”Footnote 117 The Lyonnais started considering Europe as an emerging intermediary level, between national and global markets in banking.Footnote 118 Barclays, too, believed Europe had now to become its home market.Footnote 119 Third, when big commercial banks decided to act, they did so well in advance of the 1992 deadline, and went somewhat faster than the EEC legislative process, through a sharp surge in participation in joint ventures and in acquisitions of foreign banks, together with internal restructuration. Barclays stressed the desirability of creating a distinct European culture and structure in well-defined areas.Footnote 120 In 1988, it reorganized the management structure of its European operations, separating corporate and retail banking and appointing new managers.Footnote 121 In 1990, the Crédit Lyonnais created a structure managing all the non-French European activity into a single entity.Footnote 122 In all cases, banks expected new threats in their home market and new opportunities in Europe, but in a highly competitive context.

Banking clubs’ restructuring was another response of big commercial banks to the expected changes of the “Horizon 1992,” even if most of them eventually did not survive the post-1992 era. In 1989, Commerzbank, member of Europartners together with the Crédit Lyonnais, the Banco di Roma, and the Banco Hispano Americano, circulated to its partner banks a report entitled “The Europartners: Developing a Joint Strategy for the Single European Market.”Footnote 123 In this report, Commerzbank viewed Europartners as a useful structure for facing challenges to come, such as offering Pan-European financial know-how covering the entire European Economic Community, and increasing competition between banks but also between near-banks and nonbanks. In 1991, the Crédit Lyonnais initiated discussions with Commerzbank for exchanging shares, which represented for the Lyonnais a unique chance to penetrate the German market, which was difficult to access.Footnote 124 The completion of the common market in banking also triggered renewed dynamism at EBIC, which gathered the Société Générale, Midland Bank, and Deutsche Bank, among others. In 1987, they issued a “Restatement of Direction” in which they welcomed and supported progress in the realization of a “free European financial market by 1992,” and suggested restructuring their club.Footnote 125 In 1989, they issued a “Draft of a European ‘Doctrine’” in which they stressed the role of their club in fostering the technical progress of European banking and mentioned its various initiatives such as a common banking database, a Euro-netting project developed with ABECOR (Associated Banks of Europe Corporation, the club of Barclays, BNP, and others), and a proposed Market Data Exchange.Footnote 126

The forthcoming common market in banking was not complete, however, a feature that bankers did not fail to notice. In December 1992, Umberto Burani, secretary general of the European Banking Federation, published in the journal of the AFB, Banque, a paper in which he expressed a balanced view on the new European banking environment.Footnote 127 He argued that national interests were to play an essential role in this common market in banking for a long time. First, because even though no limit to foreign banks’ establishment or participation was expressed in the second banking directive, he could hardly see how a country would let its entire banking system be controlled by foreign institutions. In France, he further argued, authorities had limited foreign acquisitions in the wake of the privatization of banks in the late 1980s, and the Commission had not complained. Second, he considered that direct establishment was a costly and challenging exercise for a bank, which had to adapt to local habits. Therefore, banks tended to prefer to operate through merger and acquisition of existing banks. Third, disparities would subsist in the common market in banking because rules in the European Union just set a minimum level, meaning that a member state could still enact stricter measures. As a consequence, national banking supervisors would have considerable responsibilities in ensuring that their banks enjoyed comparable competitive conditions with their European competitors. Indirectly, Umberto Burani was pointing to the national champions issue in the EU, which ran counter to the principle of a common market in banking.

Conclusion

This article showed that, contrary to what is sometimes suggested in the literature, businesses were not necessarily key drivers of integration. In the case of the common market in banking, banks took time to embrace the idea and kept a balanced enthusiasm toward the project. In addition, the British and French banking sectors mainly supported the liberalization part of the common market in banking program. Their position suggests that the common market in banking was primarily political, for at least three reasons. First, banks did not ask for it, they had more a reactive than a proactive position in this matter, even if they were actually influential in the process, both at the request of the Commission and at their own initiative. Second, the big change came with the ambitious program set out by the white paper and the ensuing Single European Act, in which political actors like Delors, Cockfield, and member states governments played a key role in unlocking the financial integration of Europe with numerous directives. Third, banks were actually skeptical about the possibility of ever having a true common market in banking in Europe, given the differences in financial systems and the difficulty to penetrate local business. In some cases, such as the harmonization dimension, the BBA in particular was fiercely opposed to the integration program of the Commission.

However, the BBA, the EBF, and the big French banks changed their minds on the European integration process for a variety of reasons. First of all, Europe largely aligned on their demands, such as liberalization of capital flows and mutual recognition. Furthermore, the cumulation of many directives in the financial sector made clear both the political determination of the Commission and of member states, and the actual change that the European process would bring. In addition, several banks realized that European integration could bring opportunities, such as an easier access to new member states’ markets, like Greece, Spain, or Portugal. French banks considered that European integration deserved support because it could help defend European interests, for instance on reciprocity issues, even if their initiative in this field mostly failed. Part of the change of position toward Europe was also circumstantial: The 1970s international credit boom had turned international banks away from Europe, but the early 1980s international debt crisis and its aftermath, together with the securitization trend in banking, brought them back to the old continent. Finally, the regulatory changes happening at the national and global level made some initial resistance vanish, in particular in the field of harmonization of capital ratios, which were being requested by the United States. A major change in the regulatory environment was accepted, as it was progressively recognized as both inescapable and desirable.