Background

The transition to first-time or subsequent fatherhood necessitates a change from a familiar existing reality to an unfamiliar new reality, where fathers need to balance family and work life, care for a new-born infant, and adjust to relationship changes with their partner (Genesoni and Tallandini, Reference Genesoni and Tallandini2009; Glasser and Lerner-Geva, Reference Glasser and Lerner-Geva2018). In general, the changes experienced during the transition are positive and lead to personal growth; however, fathers can also experience adverse mental health such as stress, anxiety, and depression (Cameron et al., Reference Cameron, Sedov and Tomfohr-Madsen L2016; Philpott et al., Reference Philpott, Leahy-Warren, FitzGerald and Savage2017, Reference Philpott, Savage, FitzGerald and Leahy-Warren2019). For the majority of fathers who experience adverse mental health, their responses are transient and adaptive in nature; however, for a small but significant number of fathers, non-adaptive symptomatology may contribute to the development of new or a re-emergence of mental health concerns and/or diagnosis (Pinto et al., Reference Pinto, Figueiredo, Pinheiro and Canário2016; Seah and Morawska, Reference Seah and Morawska2016). The most commonly researched adverse paternal mental health outcome during the early postnatal period is depression (Cameron et al., Reference Cameron, Sedov and Tomfohr-Madsen L2016); however, more recently, stress and anxiety have also begun to emerge as significant mental health concerns (Leach et al., Reference Leach, Poyser and Cooklin2016; Philpott et al., Reference Philpott, Leahy-Warren, FitzGerald and Savage2017).

Stress symptoms

Lazarus and Folkman (Reference Lazarus and Folkman1984) in their Transactional Model of Stress and Coping defined stress as ‘a particular relationship between the person and the environment that is appraised by the person as taxing or exceeding his or her resources and endangering his or her well-being’ (p. 19). During the early postnatal period fathers face many new stressors arising from their new-born's needs (Hildingsson and Thomas, Reference Hildingsson and Thomas2014) and relationship changes (Kamalifard et al., Reference Kamalifard, Hasanpoor, Babapour, Kheiroddin, Panahi, Payan and Bayati2014). To date one systematic review has investigated paternal stress and reported that fathers' stress symptoms increased from the antenatal period to the time of birth and early postnatal period, with a decrease in stress in the later postnatal period (Philpott et al., Reference Philpott, Leahy-Warren, FitzGerald and Savage2017). Based on screening tools, Philpott et al. (Reference Philpott, Leahy-Warren, FitzGerald and Savage2017) in their systematic review reported a prevalence of stress symptoms among fathers during the perinatal period between 6% and 8.7%. Besides stress, other paternal mental health adverse outcomes that have been researched include anxiety.

Anxiety symptoms

Spielberger (Reference Spielberger1972, p. 12) in his State–Trait Anxiety theory defined anxiety as ‘as an emotional response to stimulus perceived as dangerous’. In Spielberger's theory, anxiety facilitates the avoidance of danger and is a normal adaptive response; however, anxiety becomes maladaptive when it interferes with functioning, becomes overly frequent, severe, and persistent (Spielberger, Reference Spielberger1972; Beesdo et al., Reference Beesdo, Knappe and Pine2009). During the early postnatal period fathers face many new anxieties arising from the need to balance family and work life (Koh et al., Reference Koh, Lee, Chan, Fong, Lee, Leung and Tang2015), supporting their partner and caring for their infant (Mahmoodi et al., Reference Mahmoodi, Golboni, Nadrian, Zareipour, Shirzadi and Gheshlagh2017). Similar to stress symptoms, a recent systematic review reported that fathers' anxiety symptoms increased from the antenatal period to the time of birth and early postnatal, with anxiety decreasing in the later postnatal period (Philpott et al., Reference Philpott, Savage, FitzGerald and Leahy-Warren2019). Based on screening tools, Philpott et al. (Reference Philpott, Savage, FitzGerald and Leahy-Warren2019) in their systematic review reported that the prevalence rate for anxiety symptoms ranged between 3.4% and 25.0% during the antenatal period and between 2.4% and 51% during the postnatal period. While there is increasing research interest in paternal anxiety, the predominant focus has been on depression (Leach et al., Reference Leach, Poyser and Cooklin2016).

Depression symptoms

Depression is ‘a state of low mood, with symptoms such as sadness, fatigue, loss of interest, and loss of appetite’ [World Health Organisation (WHO), 2017, p. 7]. While fathers can experience many of these depression symptoms during the perinatal period (Cameron et al., Reference Cameron, Sedov and Tomfohr-Madsen L2016), for the majority their symptoms are transient and are linked to stresses associated with the transition to fatherhood, or the arrival of subsequent children. To date, two systematic reviews have been undertaken to assess paternal depression symptoms (Paulson and Bazemore, Reference Paulson and Bazemore2010; Cameron et al., Reference Cameron, Sedov and Tomfohr-Madsen L2016). Based on screening tools, both Paulson and Bazemore (Reference Paulson and Bazemore2010) and Cameron reported the 3–6 month postnatal period as having the highest prevalence estimate of depression; however, Cameron et al. (Reference Cameron, Sedov and Tomfohr-Madsen L2016) reported a much lower prevalence rate of 13.0% compared to Paulson and Bazemore (Reference Paulson and Bazemore2010) who reported a rate of 25.6%.

To date there has only been one Irish study that has assessed paternal perinatal mental health. Philpott and Corcoran (Reference Philpott and Corcoran2018) assessed depression symptoms in 100 fathers up to 1 year postnatally and reported prevalence rates of 12% for major depression [Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) cut-off score of ⩾12) and 28% for minor depression (EPDS cut-off score of ⩾9]. Studies assessing paternal perinatal mental health have reported wide variations in reported prevalence rates. This wide variation may be attributed to diverse settings, sample size, recruitment strategies, inclusion and exclusion criteria, assessment timepoints, cut-off scores, the use of different measurement tools, and the cultural setting of the study. The sociocultural context of fatherhood can potentially have an impact on perinatal mental health. For example, in cultures where patriarchy is the dominant ideology, and emphasis is placed on the fathers' role as a ‘breadwinner’ and provider (Firouzan et al., Reference Firouzan, Noroozi, Farajzadegan and Mirghafourvand2019), it has been reported that fathers are more susceptible to stress and anxiety. For fathers in patriarchal societies, worry about family finances and the cost linked with having a baby can act as a catalyst for increased stress and anxiety (Genesoni and Tallandini, Reference Genesoni and Tallandini2009, Darwin et al., Reference Darwin, Galdas, Hinchliff, Littlewood, McMillan, McGowan and Gilbody2017). While fathers in Ireland are expected to play an equal role in caring for their infant, similar to international studies, Irish research shows significant gender differences in involvement in care for children, with fathers spending significantly less time on childcare than mothers (Smyth and Russell, Reference Smyth and Russell2021).

This study was undertaken in the early postnatal period which is considered one of the most challenging times for fathers due to the need to balance the numerous demands placed on them (Genesoni and Tallandini, Reference Genesoni and Tallandini2009; Glasser and Lerner-Geva, Reference Glasser and Lerner-Geva2018). Furthermore, it is a significant time for fathers as they begin to build their bond with their infant and redefine their relationships with their partner and wider society. The importance of optimum adaptation and well-being during the early postnatal period is of paramount significance given the potential negative outcomes of poor adaptation and wellbeing for fathers, their partner, and infant including excessive fatigue, adverse maternal mental health, and a variety of psychological and developmental disturbances in later childhood (Fisher, Reference Fisher2017). Currently in the literature there are different timeframes used to define the early postnatal period ranging from immediately after birth to 30 days postnatally (World Health Organisation, 2010; Yuan et al., Reference Yuan, Li and Shorey2021). In this study the infants were 0 to 4 days old.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to assess the prevalence and associated factors of stress, anxiety, and depression symptoms in the early postnatal period with data generated from the same population. The simultaneous analysis of associated variables more readily assesses fathers' real-world experience, where they are likely to encounter multiple factors associated with stress, anxiety, and depression. Given the lack of clarity around the prevalence and associated factors of paternal stress, anxiety, and depression symptoms in the early postnatal period this study is both timely and warranted.

Methods

Aim of the study

The aim of this study was to investigate the prevalence of and associated factors for paternal stress, anxiety, and depression symptoms in the early postnatal period.

Research design

A quantitative, descriptive correlational design was used.

Sampling and participants

Fathers regardless of parity, who were aged ⩾18 years, able to read and write English, and who were visiting their partner following the birth of their new-born infant at one large regional maternity hospital in the southern region of Ireland were invited to take part in the study. Fathers completed the paper-based questionnaire at the maternity hospital. Fathers whose infant had a diagnosis of a birth defect, were admitted to the neo-natal unit, or who were stillborn were excluded. Non-probability, convenience sampling was used to recruit fathers.

A pilot study (n = 20) was undertaken at the maternity hospital to ascertain the time that it took to complete the questionnaire, to ensure the clarity of the questions, and the effectiveness of the instructions (Parahoo, Reference Parahoo2014). Fathers who completed the pilot study did not highlight any questions as unclear and none of them made any suggestions about removing any of the questions; therefore, no changes were made to the questionnaire following the pilot study. For the majority of fathers, it took around 10 min to complete; however, one father commented that the questionnaire took him over 20 min to complete. With regards to logistics and feasibility of collecting data, no major issues arose during the pilot study. The data from the pilot study were included in the final analysis.

Measurement tools

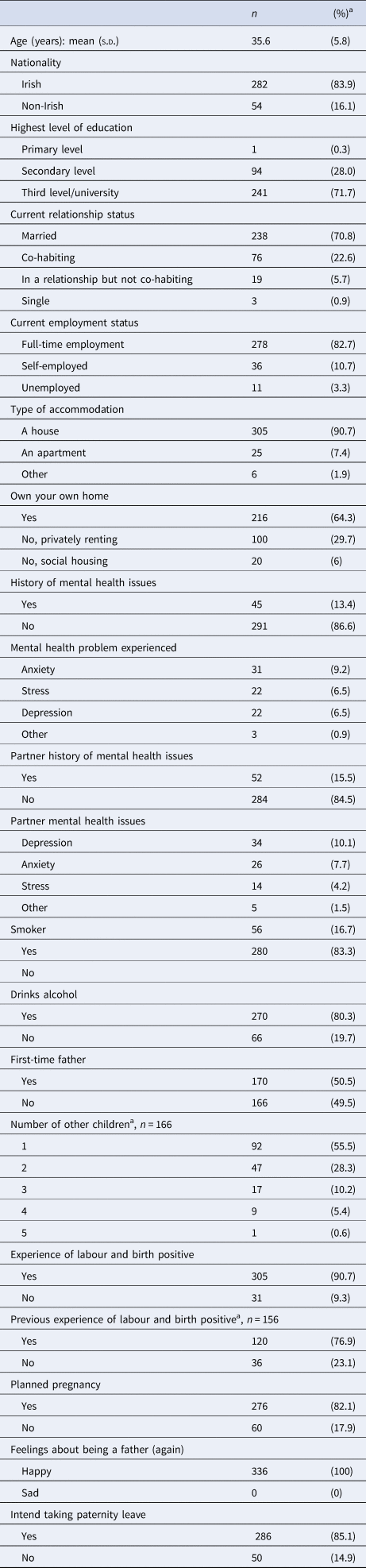

The paper-based questionnaire consisted of two sections. The first section consisted of questions regarding fathers' demographic information, their own mental health and that of their partner and their pregnancy, birth and labour history and experience (see Table 1). The second section consisted of three screening instruments used to assess paternal stress, anxiety, and depression symptoms (Cohen et al., Reference Cohen, Kamarck and Mermelstein1983; Spielberger et al., Reference Spielberger, Gorsuch, Lushene, Vagg and Jacobs1983; Cox et al., Reference Cox, Holden and Sagovsky1987).

Table 1. Demographic characteristics and self-reported mental health history, n = 336a

a For non-first-time fathers.

The Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) (Cohen et al., Reference Cohen, Kamarck and Mermelstein1983) was used to measure stress symptoms. The 10 items on the scale are rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from ‘Never’ to ‘Very often’. Scores can range from 0 to 40 with higher scores indicating higher perceived stress. Scores were categorised into low perceived stress (0–13); moderate perceived stress (14–26), and high perceived stress (27–40) (Swaminathan et al., Reference Swaminathan, Viswanathan, Gnanadurai, Ayyavoo and Manickam2016). In this study the scale demonstrated high reliability with a Cronbach's alpha value of 0.85.

The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) (Spielberger et al., Reference Spielberger, Gorsuch, Lushene, Vagg and Jacobs1983) was used to measure anxiety symptoms. The STAI consists of two distinctive scales. The Anxiety-State Scale (S-Anxiety) measures how people currently feel with the Anxiety-Trait Scale (T-Anxiety) measuring how people feel in general. Each scale consists of 20 items rated on a 4-point Likert scale. Scores on each scale can range from 20 to 80 with higher scores representing increased anxiety symptoms. A cut-off score of 40 (⩾40) was used for screening anxiety symptoms (Julian, Reference Julian2011; Emons et al., Reference Emons, Habibovic and Pedersen2019). In this study the STAI demonstrated excellent reliability with each scale having a Cronbach's alpha value of 0.93.

The EPDS (Cox et al., Reference Cox, Holden and Sagovsky1987) was used to measure depression. The 10 items on the scale are rated on a 4-point Likert scale. Scores range from 0 to 30 (Cox et al., Reference Cox, Holden and Sagovsky1987). A cut-off of 9 (⩾9) was used to identify fathers at risk of minor depression with a cut-off of 12 (⩾12) for major depression (Matthey et al., Reference Matthey, Barnett, Kavanagh and Howie2001; Massoudi et al., Reference Massoudi, Hwang and Wickberg2016). In this study the scale demonstrated high reliability with a Cronbach's alpha value of 0.86.

Data analysis

A data-coding framework was developed prior to data collection, so that answers obtained from the questionnaire could be transferred into IBM SPSS Statistics (version 25.0, IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA). Returned questionnaires were reviewed for completeness. Following screening and cleaning of the data file, questionnaires were entered into IBM SPSS Statistics and statistical analysis was performed. Continuous variables were described using mean and standard deviation (s.d.) when normally distributed and median and interquartile range (IQR) when non-normally distributed. Categorical variables were described using frequencies and percentages. The majority of independent variables were classified as categorical data; however, there were continuous data including age, and how many children subsequent fathers had. Ninety-five per cent confidence intervals (95% CIs) for prevalence were calculated using a binomial distribution (Clopper–Pearson exact method). Univariable and multivariable logistic regression was used to investigate factors associated with PSS, SATI, and EPDS. In the multivariable analysis, forward stepwise regression was used to identify the best predictors (only variables that were significant in the multivariate analysis are reported in Tables 2–5). Unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and their corresponding 95% CIs are presented. All tests were two-sided and a p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Missing scores for individual items on the scales were replaced with the mean score of the non-missing items within the scale if at least 80% of the items had been answered.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was obtained from the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Cork Teaching Hospitals (CREC) prior to commencing the study.

Findings

Demographic characteristics and mental health history

In the study, fathers' infants ranged from 0 to 4 days. The majority of fathers in the study were Irish (n = 282, 83.9%), educated to third/university level (n = 241, 71.7%), married (n = 238, 70.8%), and in full-time employment (n = 278, 82.7%). The age of fathers ranged from 19 to 65 years with a mean (s.d.) of 35.6 (5.8) years. Just over half (n = 170, 50.5%) of the fathers were first-time fathers. Forty-five fathers (13.4%) self-reported having a history of adverse mental health including anxiety (n = 31, 9.2%), stress (n = 22, 6.5%), depression (n = 22, 6.5%), obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) (n = 1), bipolar disorder (n = 1), and not specified (n = 1). Over 15% (n = 52, 15.4%) of respondents had a partner with a history of mental health problems. Depression was the most common mental health problem experienced (n = 35, 10.4%) followed by anxiety (n = 27, 8%) and stress (n = 15, 4.4%). Five respondents stated that their partners had a different mental health problem including OCD (n = 2), postnatal depression (n = 1), MS (n = 1), and not specified (n = 1). There were 14 couples (4.1%) where both the father and his partner had a history of adverse mental health outcomes (see Table 1).

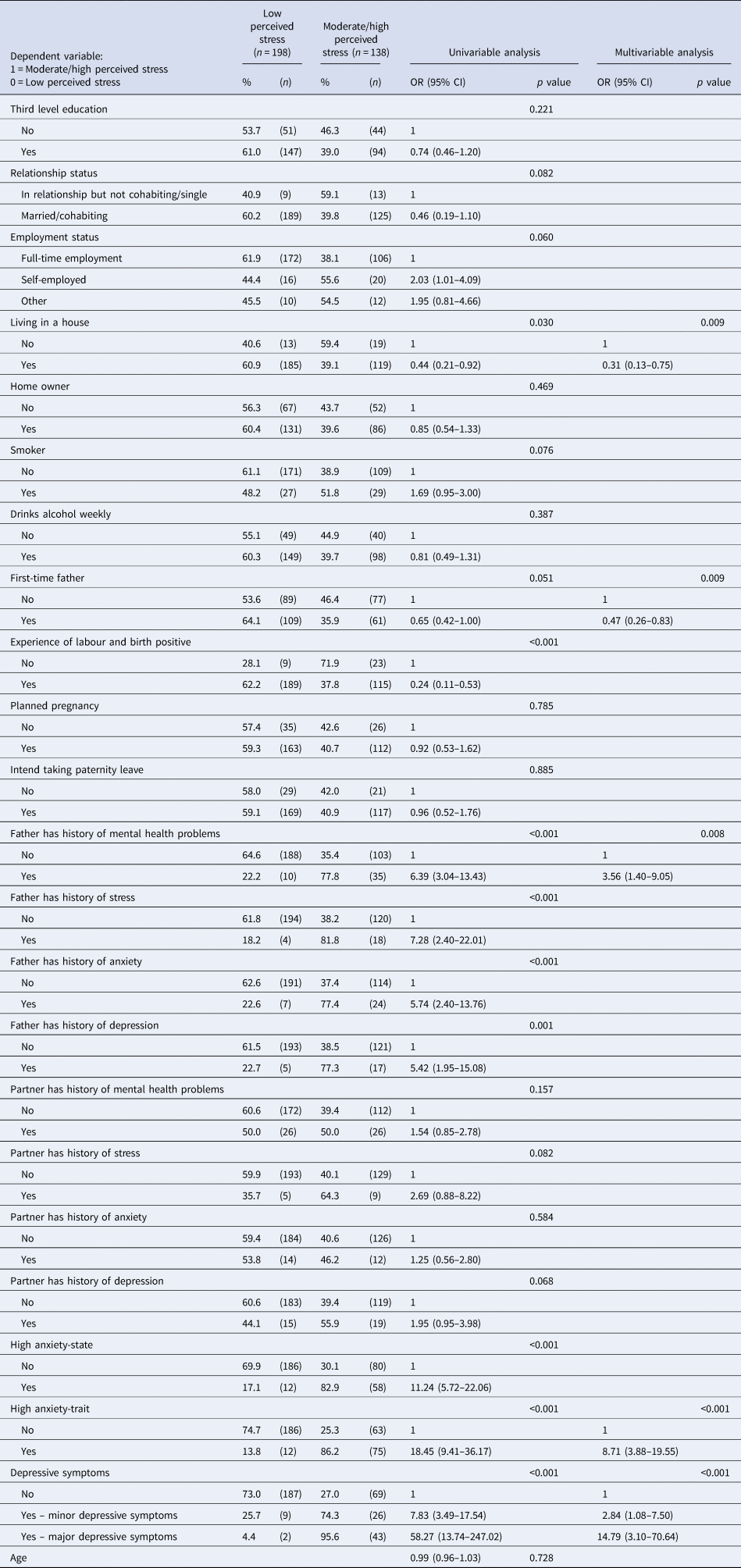

Stress symptoms

The prevalence was 58.9% (95% CI 53.5–64.2) for low stress symptoms, 39.9% (95% CI 34.6–45.3) for moderate stress symptoms, and 1.2% (0.3%–3.0%) for high stress symptoms. Based on the multivariable analyses, factors statistically significant for moderate/high stress symptoms were having an adverse mental health history (p = 0.008), a trait anxiety sore ⩾40 (p < 0.001), an EPDS score ⩾9 (p < 0.001), as well as not living in a house (p = 0.009) and being a subsequent father (p = 0.009) (see Table 2).

Table 2. Univariable and multivariable analyses to investigate relationships between fathers' characteristics and perceived stress, n = 336

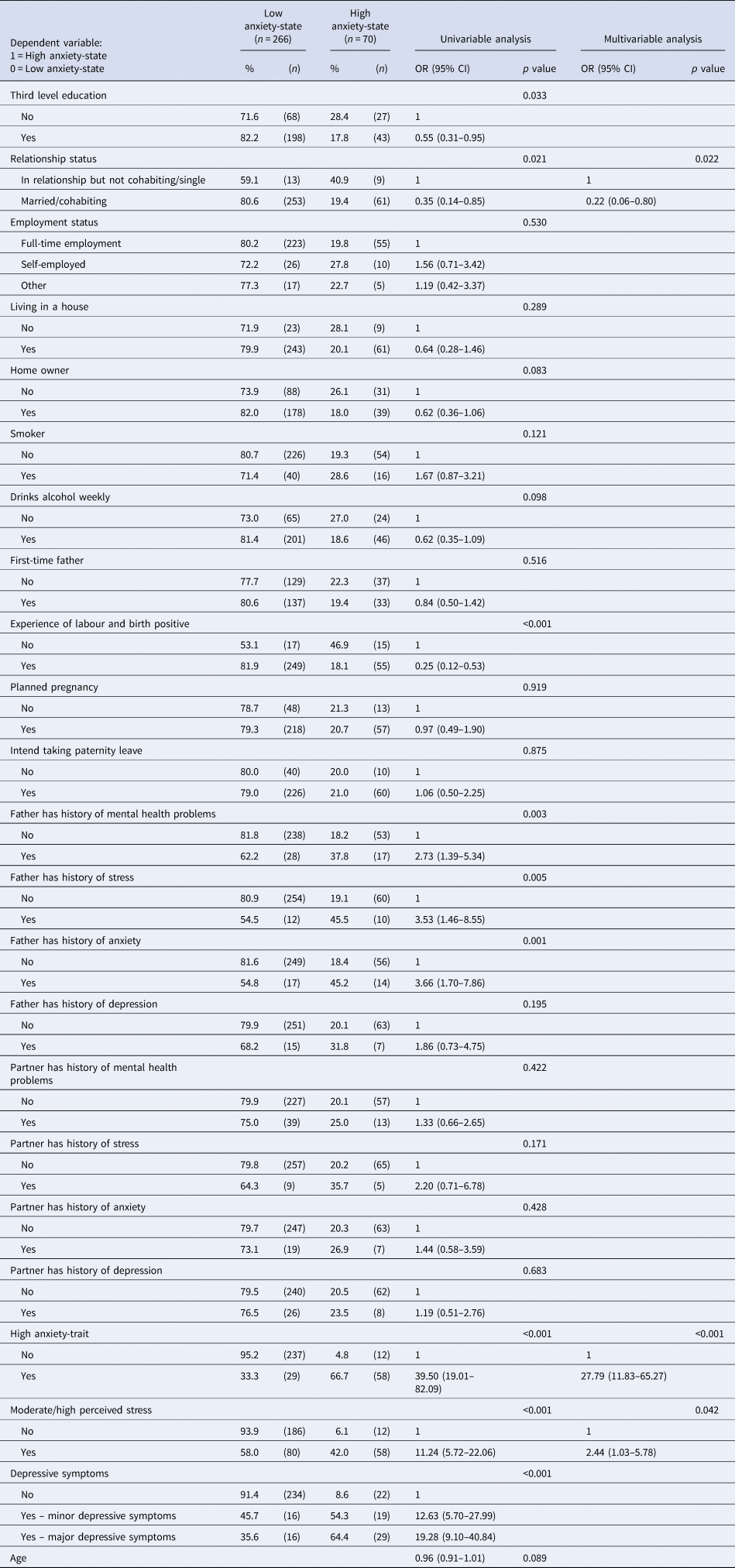

State anxiety symptoms

The prevalence of state anxiety symptoms was 20.8% (95% CI 16.6–25.6). In the multivariable analysis factors statistically significant for a high state anxiety score ⩾40 included being single/not cohabiting (p = 0.022), a high trait anxiety score ⩾40 (p < 0.001), and a moderate/high stress score ⩾14 (p = 0.042) (see Table 3).

Table 3. Univariable and multivariable analyses to investigate relationships between fathers' characteristics and anxiety-state, n = 336

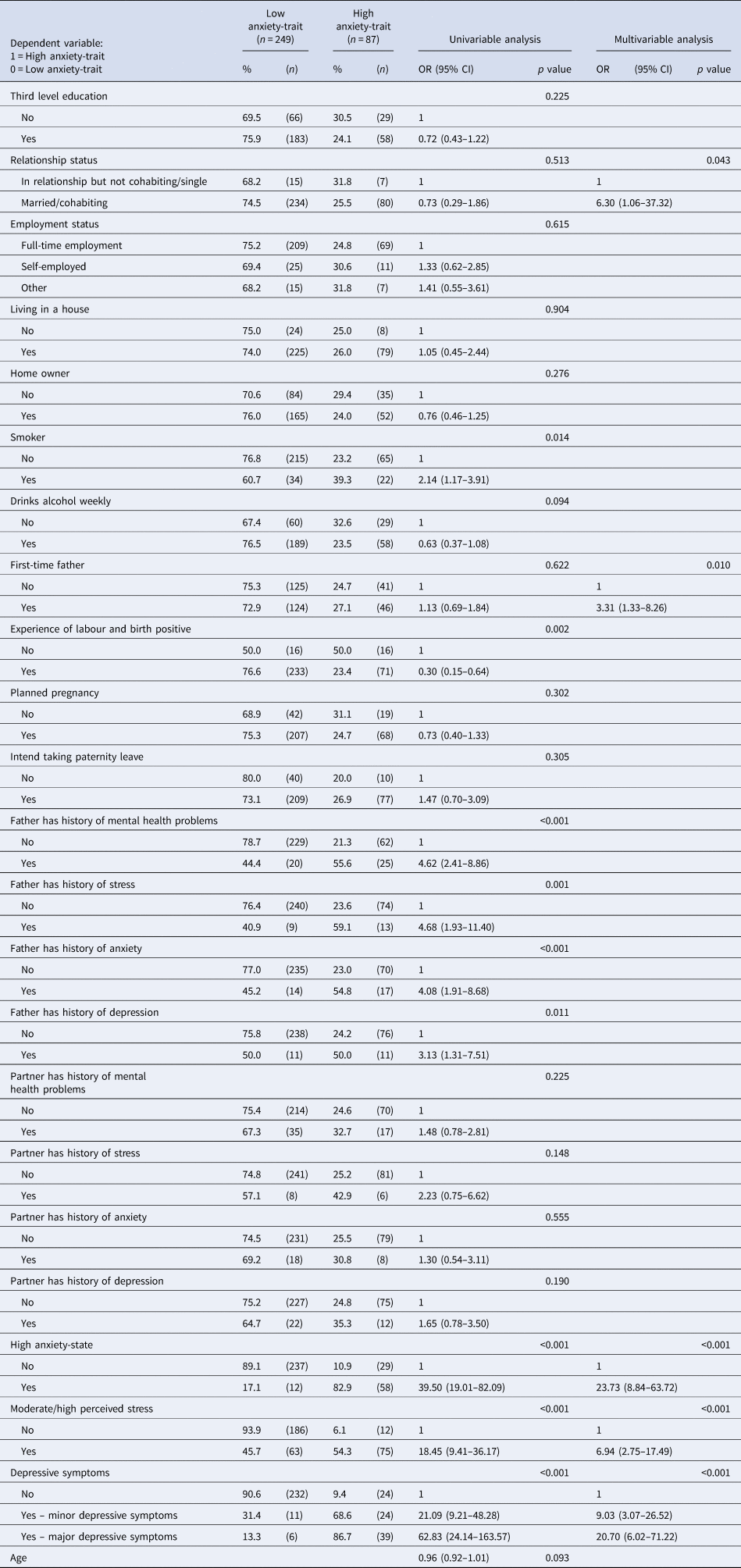

Trait anxiety symptoms

The prevalence of trait anxiety symptoms was 25.9% (95% CI 21.3–30.9). The statistically significant factors for a high trait anxiety score ⩾40 in the multivariable analysis were being a first-time father (p = 0.010), being married/cohabiting (p = 0.043), a high state anxiety score ⩾40 (p < 0.001), a moderate/high stress score ⩾14 (p < 0.001), and an EPDS score ⩾9 (p < 0.001) (see Table 4).

Table 4. Univariable and multivariable analyses to investigate relationships between fathers' characteristics and anxiety-trait, n = 336

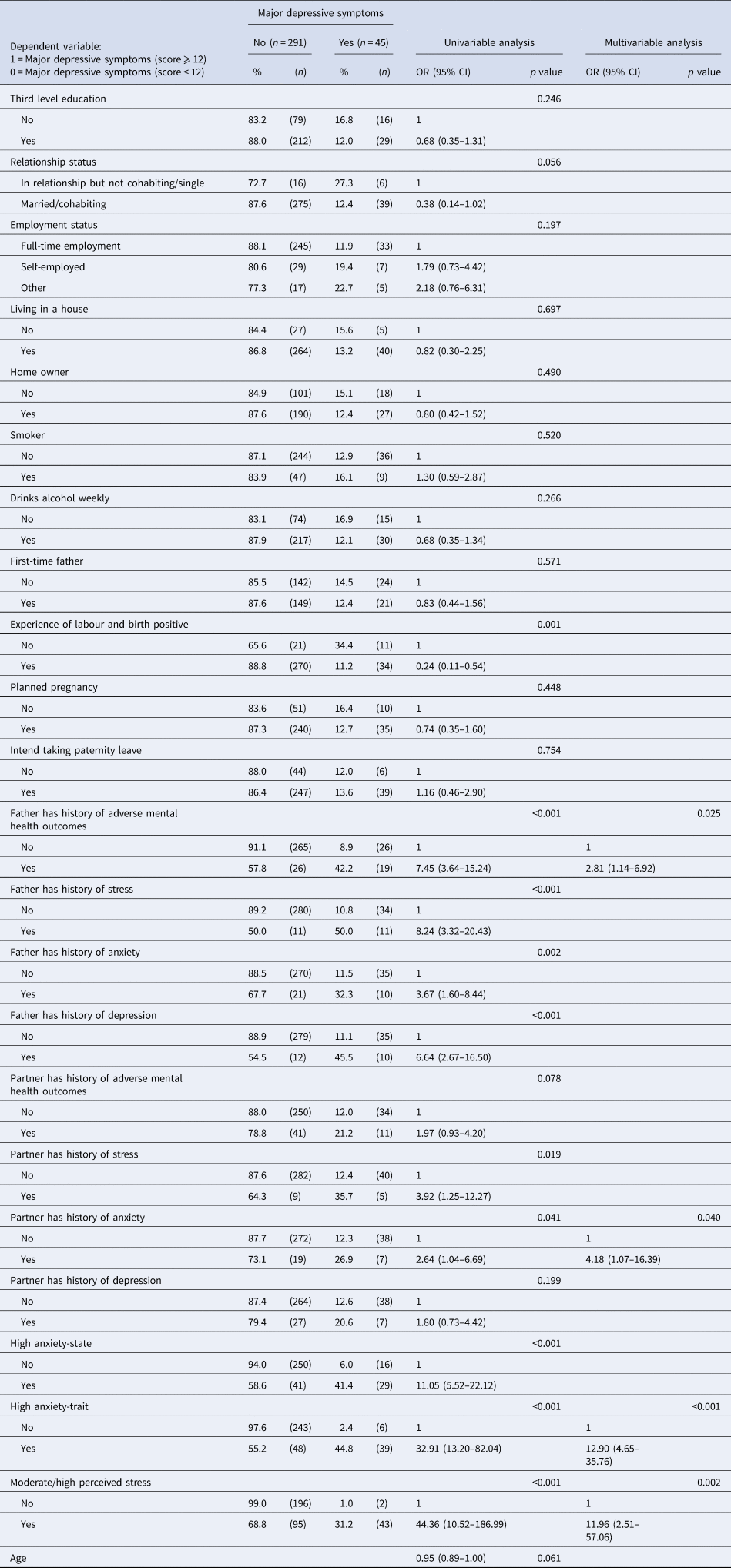

Depression symptoms

The prevalence of minor or major depressive symptoms (EPDS score ⩾9) was 23.8% (95% CI 19.4–28.7) and the prevalence of major depressive symptoms (EPDS score ⩾12) was 13.4% (95% CI 9.9–17.5). In the multivariable analysis, having a history of adverse mental health (p = 0.025), a partner with a history of anxiety (p = 0.040), a high trait anxiety score ⩾40 (p < 0.001), and a moderate/high stress score ⩾14 (p = 0.002) were statistically significant for an EPDS score ⩾12 (see Table 5).

Table 5. Univariable and multivariable analyses to investigate relationships between fathers' characteristics and major depressive symptoms, n = 336

Discussion

The aim of this study was to investigate paternal stress, anxiety, and depression symptoms in the early postnatal period. The average age of fathers in the study was 36 years which is similar to the national average age of new fathers in Ireland which is estimated at 35 years [Central Statistics Office (CSO), 2017]. The trends over the past decade in Ireland and across the developed world suggest that the age of new fathers is increasing (CSO, 2017; Halvaei et al., Reference Halvaei, Litzky and Esfandiari2020). Changing patterns of education, employment, postponement of marriage, increased life expectancy, and improved success with assisted reproductive technologies have been contributing to increased paternal age (Halvaei et al., Reference Halvaei, Litzky and Esfandiari2020). The fathers in the study were highly educated with nearly three quarters educated to third level. The national average for third level education in Ireland is just under half; however, nearly two-thirds of men aged 18–40 years possess a third level qualification (CSO, 2017). The findings suggest that the fathers in our study in terms of age, nationality, education, and employment are similar to the national average for new fathers (CSO, 2017).

In this study, stress was common with just under half of the fathers having moderate/high symptoms. Paternal stress in the early postnatal period is an important indicator of well-being, as excessive stress demonstrates evidence that parenting demands exceed one's ability to comfortably meet those demands (Koester and Petts, Reference Koester and Petts2017). Increased stress during this period highlights the demands of adjusting to early parenting (specifically, those associated with sleep and feeding) and altered relationships (Darwin et al., Reference Darwin, Galdas, Hinchliff, Littlewood, McMillan, McGowan and Gilbody2017). The early postnatal period is relatively soon after the stressful life events of labour and childbirth (McKelvin et al., Reference McKelvin, Thomson and Downe2020) and is marked by much change, the absence of routine, and the need to balance many responsibilities (Shorey et al., Reference Shorey, Dennis, Bridge, Chong, Holroyd and He2017). All these factors, have the potential to increase stress (Shorey et al., Reference Shorey, Ang and Goh2018), which can impact negatively on a fathers' ability to parent effectively and on his relationship with his partner during this critical time in the early postnatal period (Kamalifard et al., Reference Kamalifard, Hasanpoor, Babapour, Kheiroddin, Panahi, Payan and Bayati2014, Bakermans-Kranenbur et al., Reference Bakermans-Kranenburg, Lotz, Alyousefi-van Dijk and van IJzendoorn2019).

Trait anxiety was more common than state anxiety. According to Spielberger (Reference Spielberger1972), individuals with high levels of trait anxiety are more susceptible to stress and respond to situations as if they are dangerous or threatening. Furthermore, individuals with high levels of trait anxiety show state anxiety reactions more frequently and with greater intensity than those with low trait anxiety. Perhaps this should be expected as labour and birth have been reported as stressful life events by fathers (Darwin et al., Reference Darwin, Galdas, Hinchliff, Littlewood, McMillan, McGowan and Gilbody2017), and the early postnatal period is marked by many potential stressors such as the need to balance numerous demands including personal and work commitments, economic pressures, and fatigue (Genesoni and Tallandini, Reference Genesoni and Tallandini2009; Glasser and Lerner-Geva, Reference Glasser and Lerner-Geva2018). The link between stressful life events and the origin and development of anxiety has been investigated in populations outside the perinatal period and provides evidence for supporting the association (Gold, Reference Gold2015; Phillips et al., Reference Phillips, Carroll and Der2015; Zuo et al., Reference Zuo, Zhang, Wen and Zhao2020). Indeed, as fathers perceive labour, childbirth, and the early postnatal period as stressful, the potential risk for anxiety is increased (Etheridge and Slade, Reference Etheridge and Slade2017; Philpott et al., Reference Philpott, Leahy-Warren, FitzGerald and Savage2017).

A considerable number of fathers had an elevated EPDS score. Indeed, the true prevalence of depressive symptoms may be even greater given that masculine gender norms where depression is perceived as emotional weakness leads to under reporting and under detection (O'Brien et al., Reference O'Brien, McNeil, Fletcher, Conrad, Wilson, Jones and Chan2017). Additionally, while men and women express depression as low mood with reduced activity, depression in men is often masked with externalising behaviours and disorders such as substance abuse, avoidance behaviour, and anger (Chhabra et al., Reference Chhabra, McDermott and Wendy2020). Masked depression, resulting in externalising symptoms such as physical illness, alcohol and drug abuse, and domestic violence, is likely to lead to under detection (Marcus et al., Reference Marcus, Yasamy, van Ommeren, Chisholm and Shekhar2012; Chhabra et al., Reference Chhabra, McDermott and Wendy2020).

The study also investigated statistically significant factors for stress, anxiety, and depression symptoms. Two factors were unique for increased stress symptoms in this study. The first unique factor was being a subsequent father. This factor is interesting as much of the research to date has focused on the challenges experienced by first-time fathers (Márquez et al., Reference Márquez, Lucchini, Bertolozzi, Bustamante, Strain, Alcayaga and Garay2019; Ngai and Lam, Reference Ngai and Lam2020). The results reported from previous studies relating to increased stress symptoms for subsequent fathers are inconclusive (Hildingsson et al., Reference Hildingsson, Haines, Johansson, Rubertsson and Fenwick2014; Wee et al., Reference Wee, Skouteris, Richardson, McPhie and Hill2015). Despite the inconclusive findings, it is suggested that past experiences can provoke a paternal stress reaction due to a previous negative birth experience, caring for an unsettled infant or difficulties in repositioning themselves in relation to their partner, child, and work (Darwin et al., Reference Darwin, Galdas, Hinchliff, Littlewood, McMillan, McGowan and Gilbody2017; Shorey and Chan, Reference Shorey and Chan2020). Subsequent fathers also have the added stress of caring for more than one child (Darwin et al., Reference Darwin, Galdas, Hinchliff, Littlewood, McMillan, McGowan and Gilbody2017). Although subsequent fathers can gain reassurance from knowing that many of the challenges that they face are transient, the demands of meeting the needs of more than one child can trigger a stress response and increase stress symptoms. It has been reported that there is an expectation that subsequent fathers are better prepared by virtue of their previous experiences and as a result they are often overlooked in clinical practice (Shorey et al., Reference Shorey, Dennis, Bridge, Chong, Holroyd and He2017). The findings of this study suggest that the lack of focus on subsequent fathers is an oversight; however, it is widely reported that the mental health of both first-time and subsequent fathers is generally overlooked, and their needs are often unmet (Baldwin et al., Reference Baldwin, Malone, Sandall and Bick2019) and there are currently no specialised supports provided by the government in Ireland for fathers experiencing adverse mental health during the perinatal period (Health Service Executive, 2017).

The second unique factor for increased stress symptoms was not living in a house. While apartment living has been standard in most mainland European cities and many other countries across the globe, Irish culture has continually associated apartments with the first step on the property ladder or a downsize equity in later years. As a consequence, it has been suggested that there is a significant shortage of apartments suited to family occupation in Ireland (Mooney, Reference Mooney2016). In Ireland, apartments only account for 12% of all households (Central Statistics Office, 2016). The majority of fathers in this study who did not live in a house, lived in an apartment, with only six fathers living in another type of accommodation. This factor is a new finding as it has not been reported in previous studies that assessed paternal stress. It is also an important finding as it is during this critical time in the early postnatal period when fathers can become aware of the restricted living space and lack of recreational spaces associated with apartment living (Kopec, Reference Kopec2006; Barton and Rogerson, Reference Barton and Rogerson2017). It is suggested that reduced space associated with apartment living affects the overall well-being and comfort of the occupants (Kopec, Reference Kopec2006; Hu and Coulter, Reference Hu and Coulter2017) and can lead to living dissatisfaction, discomfort, and adverse mental health (Hu and Coulter, Reference Hu and Coulter2017). The relevance of this finding is highlighted by the fact that cities across the world are becoming more densified which will result in more people living in apartments with reduced space (Griffiths et al., Reference Griffiths, Lamb and Pelosi2017). Therefore, addressing the impact that such living spaces have on paternal, and family mental health well-being becomes more urgent and crucial.

A statistically significant factor for trait anxiety was being married/cohabiting, while a statistically significant factor for state anxiety was being single/not cohabiting. These findings are important as they seem to highlight that as well as a fathers' relationship status, the quality of his relationships and the support network associated with such relationships may play an important role in determining his mental health (Gao et al., Reference Gao, Chan and Mao2009; Mao et al., Reference Mao, Zhu and Su2011; Koh et al., Reference Koh, Lee, Chan, Fong, Lee, Leung and Tang2015; Chhabra et al., Reference Chhabra, McDermott and Wendy2020). Previous research has tended to focus on relationship status rather than on relationship quality (Chhabra et al., Reference Chhabra, McDermott and Wendy2020), with marriage been identified as a protective factor; however, in a small number of studies, relationship quality and marital distress have been reported as risk factors for adverse mental health (Bergström, Reference Bergström2013; Koh et al., Reference Koh, Lee, Chan, Fong, Lee, Leung and Tang2015; Nishimura et al., Reference Nishimura, Fujita, Katsuta, Ishihara and Ohashi2015). Distress in a marital relationship can diminish partner support and is likely to add to the anxiety related to the birth of an infant (Bergström, Reference Bergström2013; Nishimura et al., Reference Nishimura, Fujita, Katsuta, Ishihara and Ohashi2015). Previous research has highlighted that single fathers experience diminished co-parenting support and social support which have been identified as a risk factor for adverse mental health in the postnatal period (Gao et al., Reference Gao, Chan and Mao2009; Mao et al., Reference Mao, Zhu and Su2011; Koh et al., Reference Koh, Lee, Chan, Fong, Lee, Leung and Tang2015).

Many statistically significant factors for depressive symptoms were identified and included a self-reported adverse mental health history and a partner's history of anxiety. Other studies have also reported an adverse mental health history as a risk factor for depression during this period (Nishimura and Ohashi, Reference Nishimura and Ohashi2010; Wee et al., Reference Wee, Skouteris, Richardson, McPhie and Hill2015). Adverse mental health whether recurring or newly developed in the early postnatal period has a deleterious impact on fathers, their parenting behaviours and their relationships (O'Brien et al., Reference O'Brien, McNeil, Fletcher, Conrad, Wilson, Jones and Chan2017). There is a correlation between paternal and maternal adverse mental health, which in turn escalates the risk of infant and child emotional and behavioural problems (Pilkington et al., Reference Pilkington, Milne, Cairns, Lewis and Whelan2015). In this study, a partner's history of anxiety was an associated factor for increased depressive symptoms. Couples who are experiencing adverse mental health are more likely to face conflict or distress in their relationship and less likely to be able to communicate the difficulties and experiences they are facing (Chhabra et al., Reference Chhabra, McDermott and Wendy2020). Furthermore, when a mother experiences adverse mental health it can negatively impact on her ability to take care for her infant, which may add increased roles and responsibilities on fathers (Chhabra et al., Reference Chhabra, McDermott and Wendy2020). Given the potential adverse consequences for a father and his family, there is a compelling argument for focusing on identifying and supporting fathers who are experiencing adverse mental health in the early postnatal period.

The early postnatal period is a pivotal time for fathers in terms of bonding with their infant and redefining their relationship with their partner. It is also often a challenging time for fathers (Glasser and Lerner-Geva, Reference Glasser and Lerner-Geva2018); however, their mental health is generally overlooked, their needs are often unmet (Baldwin et al., Reference Baldwin, Malone, Sandall and Bick2019), and there are currently no specialised supports provided by the government in Ireland for fathers experiencing adverse mental health during the perinatal period (Health Service Executive, 2017). It is also during this critical period that fathers have contact with healthcare professionals (HCPs) such as midwives and doctors at the maternity hospital and public health nurses (PHNs) and general practitioners in the community. These contacts provide HCPs with a window of opportunity to identify fathers who are at risk of adverse mental health and to support them achieve optimum adaptation and well-being through increased awareness and discussions about their mental health (Huusko et al., Reference Huusko, Sjöberg, Ekström, Herfelt Wahn and Thorstensson2018). Midwives, doctors, and PHNs due to their contact with fathers in the early postnatal are well positioned to incorporate paternal mental health information and education into existing antenatal classes and reinforce the information in the hospital after birth, during well baby check-ups and immunisations. However, at both the maternity hospital and in the community, fathers are not considered clients of the HCPs; therefore, midwives, PHNs, and doctors are potentially limited in the support that they can provide. Nevertheless, the Health Service Executive (HSE) in Ireland has adopted a health behaviour framework to ‘Make Every Contact Count’ between HCPs and those who engage with the health service in order to empower and provide support so that positive health outcomes can be achieved (HSE, 2017). By using this framework as a catalyst for action, contacts between HCPs and fathers during the early postnatal period could be used to increase awareness about the support resources that are available and to advise fathers about adverse mental health.

As fathers have highlighted the challenges that they experience trying to gain information and support while engaging with the maternity services (Hambidge et al., Reference Hambidge, Cowell, Arden-Close and Mayers2021), social media and online interventions could potentially serve as effective channels through which mental health awareness and supports could be promoted. Previous research has found that fathers seek health and support information online (Jaks et al., Reference Jaks, Baumann, Juvalta and Dratva2019). The benefits of online education may be especially critical for fathers during the early postnatal period as they attempt to balance the numerous demands placed upon them and have limited time to attend in person education and support sessions (Letourneau et al., Reference Letourneau, Duffett-Leger, Dennis, Stewart and Tryphonopoulos2011; Wynter et al., Reference Wynter, Di Manno, Watkins, Rasmussen and Macdonald2021). Furthermore, interactive web sites can help reduce the feelings of shame and stigma that men feel when seeking help from HCPs in traditional settings (Thorsteinsson et al., Reference Thorsteinsson, Loi and Farr2018).

Future research

Paternal mental health during the perinatal period continues to be under-researched. Longitudinal studies are needed to build a more comprehensive picture of the paternal mental health throughout the perinatal period. Such studies will allow for a greater understanding of the variability and changes in mental health across the perinatal period. The existing research assessing paternal perinatal mental health has been predominately quantitative (Shorey and Chan, Reference Shorey and Chan2020). Fewer studies have explored men's experiences of their own perinatal mental health (Darwin et al., Reference Darwin, Galdas, Hinchliff, Littlewood, McMillan, McGowan and Gilbody2017). More qualitative research is needed to examine the views and experiences of first-time and subsequent fathers concerning their perinatal mental health, their perceptions of what makes perinatal mental health resources accessible and acceptable, the type of support fathers want, how this is provided, who provides it, and when would be the optimal time in the perinatal period to offer support. There is currently a paucity of research with diverse populations of fathers. Young fathers, gay fathers, unemployed fathers, non-resident fathers, stay at home fathers, fathers from ethnic diverse backgrounds, and lower socioeconomic groups are all under-represented in research on paternal perinatal mental health well-being (Baldwin et al., Reference Baldwin, Malone, Sandall and Bick2019).

Limitations

In this study, the population was homogenous, with most fathers Irish, educated to third/university level, married, and in full-time employment. Therefore, the generalisability of the findings is limited. Another limitation is that a cross-sectional design was used. The cross-sectional design only identified associations. Longitudinal follow-up studies are necessary to identify causal inferences (Setia, Reference Setia2016). Due to practical considerations for administering the instruments in a clinical setting, diagnostic measures were not used; therefore, the results were not objectively validated with a clinic interview. Data were collected at one site only and convenience sampling was used in the study which could potentially have led to the under-representation or over-representation of particular groups within the sample (Jager et al., Reference Jager, Putnick and Bornstein2017). In the current sample, the participants were predominantly married, employed, Irish, and had a university level education. These sample characteristics thus make it difficult to generalise the current study findings to men from more diverse backgrounds and minority groups. The manifestation of stress, anxiety, and depression symptoms might be different in a sample from more diverse and sociological backgrounds as the challenges they face might be different. In the multivariable analysis, forward stepwise regression was used to identify the best predictors of stress, anxiety, and depression symptoms. Limitations of this method of analysis have been identified (Tabachnick and Fidell, Reference Tabachnick and Fidell2019); however, it was used in this study as it is an appropriate analysis method when there are many variables, and the researcher is interested in identifying a useful subset of associated factors (Thayer, Reference Thayer2002). Furthermore, the study had a very large number of independent variables (some of which were highly correlated), compared to a relatively small sample size; therefore, stepwise forward regression was an appropriate method for selecting the independent variables to be included in the model. Finally, 71% of the population in the study were educated to third/university level, which is a considerable portion of the population; however, as there was no breakdown of their qualification level i.e. PhD, masters, or degree, it was not possible to find out if there were differences within this large group.

Conclusion

As the early postnatal period is filled with uncertainty and new challenges, it is often a challenging time for fathers. Understanding paternal mental health during this period is important, as it is a critical time for fathers as they develop their bond with their infant and redefine their relationships with their partner and wider society. This study builds on the previous body of literature related to paternal perinatal mental. A notable percentage of fathers experienced stress, anxiety, and depression symptoms which suggests that the early postnatal is a time of increased risk for adverse mental health. The findings from this study highlights that the current focus on depression does not accurately represent the substantive risk to paternal mental health wellbeing in the early postnatal. The study identified statistically significant factors associated with stress, anxiety, and depression including being a subsequent father, not living in a house, having a history of adverse mental health, and having a partner with a history of anxiety. If these results are replicated consistently in future research, they may assist HCPs identify and support fathers at risk of adverse mental health outcomes.

Financial support

No funding was received for this study.

Conflict of interest

We have no conflict of interest to declare.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.