Introduction

It seems clear that a firm needs both to explore new possibilities to ensure profits for tomorrow and to exploit old certainties for profits for today (March, Reference March1991). Although exploration and exploitation are conflicting organizational processes (Benner & Tushman, Reference Benner and Tushman2003) they are not mutually exclusive (He & Wong, Reference He and Wong2004). They are often understood as orthogonal activities (Gupta, Smith, & Shalley, Reference Gupta, Smith and Shalley2006; Uotila, Maula, Keil, & Zahra, Reference Uotila, Maula, Keil and Zahra2009; Russo & Vurro, Reference Russo2010), which interact positively, as both are necessary for the survival and development of an organization. Studies have shown that exploration (searching for new opportunities) and exploitation (refinement of existing competencies) require very different strategies and structures (e.g., O’Reilly & Tushman, Reference O’Reilly and Tushman2008; Boumgarden, Nickerson, & Zenger, Reference Borgatti and Foster2012). In general, it has been shown that exploration is associated with organic structures, path-breaking, and emerging markets and technologies, while exploitation is associated with mechanistic structures, path dependence, and stable markets and technologies (Brown & Eisenhardt, Reference Brown and Eisenhardt1998, Lewin, Long, & Carroll, Reference Lewin, Long and Carroll1999; Ancona, Goodman, Lawrence, & Tushman, Reference Ancona, Goodman, Lawrence and Tushman2001). Although some authors long ago indicated different structures and strategies for exploration and exploitation, there is some ambiguity about the relationship between strategy and structure at two phases in the innovation process (the phase of innovation exploration; and the phase of innovation exploitation) and a shortage of research in this area, especially if companies both explore and exploit at the same time. Therefore, there is a research gap regarding the need to identify the relationship and impact of strategy and organizational structure on each other in these two phases. In particular, I attempt to ascertain how and under what circumstances strategy affects structure, and likewise how and under what circumstances structure affects strategy in both exploration and exploitation innovation. It should be noted here that the relationship between a strategy and an organizational structure seen in this context has not been explored in research to date, which makes it an interesting cognitive issue.

Exploration and exploitation innovation have been widely defined in literature. Exploration innovation is often associated more with breakthroughs or radical innovations, with development of new products, creation of new markets, and the identification of needs for emerging customers and markets (Garcia, Calantone, & Levine, Reference Garcia, Calantone and Levine2003; Mom, Van den Bosch, & Volberda, Reference Mom, Van den Bosch and Volberda2007). In turn, exploitation innovation is associated with incremental technological innovations or innovations intended to respond to current consumer needs, with extensions and refinements to existing products to satisfy customers in known markets, and existing operational processes in the firm (Jansen, Van den Bosch, & Volberda, Reference Jansen, Van den Bosch and Volberda2006; Bierly & Daly, Reference Bierly and Daly2007; Andropoulos & Lewis, Reference Andriopoulos and Lewis2009). In my study, the phase of innovation exploration refers to the pursuit of new opportunities in the spirit of invention and experimentation, while the phase of innovation exploitation relates to extensions and refinements to existing products and operational activities, as these typically evolve around interests of efficiency.

My paper aims to investigate the relationship between strategy and structure in the phase of exploration, and exploitation innovation based on the experiences and their impact as perceived by chief executive officers (CEOs) in high-technology (high-tech) enterprises. The choice of this sector is intentional. High-tech enterprises are innovative (Lazonick, Reference Lazonick2010; Liefner, Wei, & Zeng, Reference Liefner, Wei and Zeng2013) and knowledge based (Kodama, Reference Kodama2006; Yang, Reference Yang2012). In this type of enterprise, structures and strategies should primarily promote innovation and the creation of new knowledge (particularly technological knowledge in the form of patents and inventions); which reflects the exploration phase of innovation (Jayanthi & Sinha, Reference Jayanthi and Sinha1998; Garcia, Calantone, & Levine, Reference Garcia, Calantone and Levine2003; Sidhu, Commandeur, & Volberda, Reference Sidhu, Commandeur and Volberda2007). On the other hand, the exploitation phase of innovation refers to extensions and refinements to existing product–market objectives and the efficiency of organizational structure in implementing them (He & Wong, Reference He and Wong2004; Wadhwa & Kotha, Reference Wadhwa and Kotha2006). Thereby, the two phases of innovation should take place in high-tech enterprises, which allows the discovery of new, mutual relations between their structure and strategies.

It should be emphasized that the high-tech sector is difficult to define because most new, advanced technologies exceed the boundaries of industries according to traditional classifications. It is usually assumed to comprise the sectors with a high dependence on science and technology (National Science Foundation), which rely on the results of processing research results in industry (Bessant, Reference Bessant2003). There is also a widespread understanding to include within the concept of the high-tech sector those industries and products which are characterized by a higher research and development (R&D) intensity compared with other industries and products (Eurostat, 2013). Here, two main approaches are used to identify technological intensity: the sectoral approachFootnote 1 and the product approachFootnote 2 . It should also be pointed out that, in addition to these industries and groups of products, high technologies are sometimes classified in a more aggregated way, namely by placing them into the following five basic categories: information technologies (electronics, information, and communication), biotechnologies, material technologies (mainly nanotechnology), power technologies, and space technologies (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD], Reference O’Sullivan, Giraldo and Roman2013). Moreover, high-tech enterprises are characterized by a short life cycle of goods and processes, a rapid diffusion of innovation, an increasing demand for highly skilled staff, and close scientific and technological cooperation among enterprises and research centers within countries and internationally (NewCronos, 2009). In my study, I assume that high-tech enterprises are companies operating in a field recognized as high technology (according to Statistical Classification of Economic Activities [NACE]; the sectoral approach), combining the features of innovative and knowledge-based enterprises.

To determine the relationship between strategy and organizational structure in exploration and exploitation innovation, I used survey data gathered from 61 high-tech companies based in Poland, which operate either in Poland or in the global marketplace. My study contributes to the research in the field of strategic organizations in two key and specific aspects. First, it expands the current knowledge of the relationship between strategy and organizational structure (e.g., Chandler, Reference Chandler1962; Rumelt, Reference Rumelt1974; Fredrickson, Reference Fredrickson1986; Mintzberg, Reference Mintzberg1990) with the aspect of innovation management by analyzing their mutual relations in the phases of innovation exploration and innovation exploitation (the theoretical contribution of the paper). Second, it indicates, based on CEOs’ opinions, practical propositions on how strategy and organizational structure should be shaped in order to be conducive to high-tech enterprise development (the empirical contribution of the study).

The study is organized as follows. First, I define ‘strategy’ and ‘organizational structure’ in high-tech enterprises, taking into account modern approaches to strategies and organizational structures, and I show which of them are the most appropriate for high-tech enterprises due to their particular traits, in particular for exploration and exploitation innovation. Second, I determine the strength and direction of the impact of strategy on organizational structure and vice versa in the phases of innovation exploration and of innovation exploitation in high-tech companies. Third, taking into account various dimensions of strategy, the features of organizational structure, and the strength of their mutual influence, I present a pattern that fits strategy and organizational structure for high-tech enterprises, as well as for other less technologically advanced but innovative and knowledge-based enterprises, that is meant to enhance their success. This pattern has been expanded to include managerial implications.

The Multidimensional Nature of Strategy–Structure Relations in High-Tech Enterprises: Concept and Hypotheses

The strategy of high-tech enterprises: Resources and opportunities

The concept of strategy is ambiguous and is interpreted differently in the literature, what is evidenced by numerous schools and approaches to strategy (e.g., De Wit & Meyer, Reference De Wit and Meyer2005; Mintzberg, Ahlstrand, & Lampel, Reference Mintzberg, Ahlstrand and Lampel2009; Galvin & Arndt, Reference Galvin and Arndt2014). Because of this ambiguity and in order to better understand the essence of the strategies of high-tech companies, I carried out an expert survey in 2009. I selected a panel of 15 experts, including 11 well-known academics from Polish universities working in the field of strategic management, two representatives of consulting companies providing business consulting services for the high-tech sector, and two CEOs managing high-tech companies. The experts were asked to express their views (as comprehensively as was practically possible) regarding strategy in high-tech sector companies (I asked them five open-ended questions that focused, among other things, on indicating the most appropriate approach to strategy).

Due to the peculiarity of high-tech enterprises (i.e., their high level of innovation and development of new knowledge, particularly technological), most experts agreed that the two best approaches to strategy in such enterprises are the resource-based view (Smith, Vasudevan, & Tanniru Reference Smith, Vasudevan and Tanniru1996; Barney, Reference Barney2001; Lin, Lin, & Bou-Wen, Reference Lin, Lin and Bou-Wen2010; Lu & Liu, Reference Lu and Liu2013) and the approach based on opportunities (Alvarez & Barney, Reference Alvarez and Barney2007; Bingham & Eisenhardt, Reference Bingham and Eisenhardt2008; Short, Ketchen, Shook, & Ireland, Reference Short, Ketchen, Shook and Ireland2010; Wood & McKinley, Reference Wood and McKinley2010), because they require being flexible and pro-innovative.

The resource-based view assumes that the success of an organization lies within the organization itself, or to be exact – in its valuable, intangible, and not perfectly imitable resources (VRIO condition, ie. Valuable, Rare, costly to Imitate, Organized to capture value) allowing it to achieve a sustainable competitive advantage (Barney & Clark, Reference Barney and Clark2007). Resources are generally defined as ‘all assets, capabilities, organizational processes, firm attributes, information, knowledge, etc. controlled by a firm’ (Armstrong & Shimizu, Reference Armstrong and Shimizu2007; Barney & Clark, Reference Barney and Clark2007). In high-tech enterprises, due to their peculiarity, the most important is the availability of innovative resources, for example, know-how, patents, R&D base (Chen, Reference Chen and Kannan-Narasimhan2012; Pujol-Jover & Serradell-Lopez, Reference Pujol-Jover and Serradell-Lopez2013), the competence, talents, creativity, and innovative skills of employees (Quintana-García & Benavides-Velasco, Reference Quintana-García and Benavides-Velasco2008; Rasulzada & Dackert, Reference Rasulzada and Dackert2009), as well as partnership relationships with outside entities (Willoughby & Galvin, Reference Willoughby and Galvin2005). The development of these innovative resources (especially technological knowledge) allows an enterprise to expand and change both its geographical and product areas, or to sell a specific resource in the form of a license, thus obviating the need to run a production facility.

The development of resource-based view is closely linked to the growing turbulence of the environment, because in the context of its unpredictability, resources and competences are a more stable base on which to generate strategies (Grant, Reference Grant2003). Because the environment in which high-tech enterprises operate is unpredictable and complex (Gavetti, Levinthal, & Rivkin, Reference Gavetti, Levinthal and Rivkin2005; Davis, Eisenhardt, & Bingham, Reference Davis, Eisenhardt and Bingham2009), such enterprises also need to be highly responsive in order to take advantage of opportunities, which require a redundancy of resources (i.e., creating an excess of resources, especially innovative ones). Moreover, the use of emerging opportunities and creation of new ones is possible, in accordance with the network paradigm (Borgatti & Foster, Reference Birkinshaw and Gupta2003), through operation in heterogeneous interorganizational networks (Jarvenpaa & Välikangas, Reference Jarvenpaa and Välikangas2014). Davis, Eisenhardt, and Bingham (Reference Davis, Eisenhardt and Bingham2009) and Eisenhardt and Sull (Reference Eisenhardt and Sull2001) stated that strategy formulation in an opportunity context is best achieved using a strategic management artifact called simple rules. Brown and Eisenhardt (Reference Brown and Eisenhardt1997) indicated that high-tech firms with a moderate number of simple rules (i.e., semistructure) are more flexible and efficient – quickly creating high-quality, innovative products while responding to market shifts – than firms with more or fewer rules. Hence, opportunity strategy focuses on selecting a few strategic processes with deep and swift flows of opportunities and learning simple rules to take advantage of opportunities (Bingham & Eisenhardt, Reference Bingham and Eisenhardt2008).

Taking into account the above views on strategy, it can be concluded that the development of technologies, innovations, and knowledge as resources (the resource-based view approach) provides the foundation for the strategy of high-tech enterprises when attempting to take advantage of fleeting opportunities, which reflects the exploration activities connected with invention, experimentation, and the search for new opportunities (Huff, Floyd, Sherman, & Terjesen, Reference Huff, Floyd, Sherman and Terjesen2009). The exploitation of these opportunities and full use of a firm’s existing competencies determine, extend, and refine the product–market domains expressed most in terms of (1) the specialization and diversification of the product and market; (2) internal and/or external growth; and (3) the scope of vertical integration (Pearce & Robinson, Reference Pearce and Robinson2007; Johnson, Scholes, & Whittington, Reference Johnson, Scholes and Whittington2008), which in turn mirrors exploitation activities.

The organizational structure of high-tech enterprises: An ambidextrous approach

The organizational structure of high-tech enterprises should make it possible for employees to perform creative tasks oriented toward the development of new knowledge (Nonaka & Takeuchi, Reference Nonaka and Takeuchi1995; Hagel & Brown, Reference Hagel and Brown2005), yet it should also enable them to perform routine actions efficiently (Daft, Reference Daft2007). Moreover, high-tech enterprises should also be able to explore innovations and combine the optimal performance of operational units with the exploitation of innovations (Bessant, Reference Bessant2003). In light of this, the ambidextrous organizational design is the best approach for such enterprises, and arguments in support of this approach for innovative companies are well established in the literature (e.g., He & Wong, Reference He and Wong2004; O’Reilly & Tushman, 2004; Andriopoulos & Lewis, Reference Andriopoulos and Lewis2009; Cantarello, Martini, & Nosella, Reference Cantarello, Martini and Nosella2012; Chandrasekaran, Linderman, & Schroeder, Reference Chandrasekaran, Linderman and Schroeder2012). Duncan (Reference Duncan1976) was the first who used the term ‘organizational ambidexterity.’ He argued that for long-term success, firms needed to consider dual structures, with different structures to initiate and to execute innovation. In this view, also called ‘temporal’ or ‘sequential’ ambidexterity, exploitation and exploration are separated in time, with the organization moving from one prevailing approach to the other (Markides, Reference Markides2013; O’Reilly & Tushman, Reference O’Reilly and Tushman2013). Over the years, scholars have identified other forms of ambidexterity known as: structural, contextual, and leadership (Nosella, Cantarello, & Filipini, Reference Nosella, Cantarello and Filippini2012; Birkinshaw & Gupta, Reference Boumgarden, Nickerson and Zenger2013; O’Reilly & Tushman, Reference O’Reilly and Tushman2013). In this study, I focus on structural ambidexterity, which allows the organization to explore and exploit innovations simultaneously (O’Reilly & Tushman, 2004; Gilbert, Reference Gilbert2005; Jansen, Tempelaar, Van den Bosch, & Volberda, Reference Jansen, Van den Bosch and Volberda2009), but demands different organizational architectures for these activities. Exploration requires decentralized structures, loose work processes, and a focus on experimentation, while exploitation needs highly structured roles and responsibilities, centralized procedures, and a focus on efficiency (Chen & Kannan-Narasimhan, Reference Chen2015). High-tech enterprises need structures that promote both exploration and exploitation innovation and cannot afford to be forced to choose either one or the other.

According to structural ambidexterity, exploration and exploitation are separated and coordinated by senior management (O’Reilly & Tushman, 2004). Organizations create spatial separation, referred to as structural separation (Raisch & Birkinshaw, Reference Raisch and Birkinshaw2008), at the business unit or corporate level. There are two types of subunit in the organization, one focusing primarily on exploration (e.g., R&D), another on exploitation (e.g., manufacturing), with their integration occurring at the level of the entire organization (Benner & Tushman, Reference Benner and Tushman2003; Jansen et al., Reference Jansen, Van den Bosch and Volberda2009; Kortmann, Reference Kortmann2012).

The literature frequently describes organizational structures conducive to innovative and knowledge-based companies through the prism of their features, such as specialization, standardization, configuration, centralization, formalization, and flexibility (e.g., Myers, Reference Myers1996; O’Sullivan, Giraldo, & Roman, Reference O’Reilly and Tushman2010; Zelong, Yaqun, & Changhong, Reference Zelong, Yaqun and Changhong2011; Mahmoudsalehi, Moradkhannejad, & Safari, Reference Mahmoudsalehi, Moradkhannejad and Safari2012; Arora, Belenzon, & Rios, Reference Arora, Belenzon and Rios2014). Discussing the organizational structure features in accordance with the structural ambidextrous approach, numerous studies (e.g., Alder & Borys, Reference Alder and Borys1996; Jansen, Van den Bosch, & Volberda, Reference Jansen, Tempelaar, Van den Bosch and Volberda2005; Wei, Yi, & Yuan, Reference Wei, Yi and Yuan2011) recommend that enterprises adopt low formalization, high decentralization, and a flat hierarchy in the phase of innovation exploration, and to have an organic structure with little standardization and specialization. However, in the phase of innovation exploitation, the structure can be more bureaucratic; in this phase, the structure can have greater standardization and specialization, a higher level of formalization and centralization, and a taller hierarchy. These opposite structural features of exploration and exploitation subunits require integration at the senior level of management.

Besides organizational structure features, sometimes particular forms of organizational structure are indicated. For instance, Hedlund (Reference Hedlund1994) proposed an N-form corporation for knowledge-based firms. He added, however, that ‘radical innovations are not achieved by (re)combination and experimentation only, and these innovations can be achieved through specialization, abstract articulation, and investment outside present competences’ (Hedlund, Reference Hedlund1994), that is through M-form structures. Daft (Reference Daft2007) also indicated that elements of design, process, and network structures are appropriate for innovative and knowledge-based companies. Specifically, the latter are characteristic of high-tech companies (Rank, Rank, & Wald, Reference Rank, Rank and Wald2006; Bertrand-Cloodt, Hagedoorn, &Van Kranenburg, Reference Bertrand-Cloodt, Hagedoorn and Van Kranenburg2011; Helena Chiu, & Lee, Reference Helena Chiu and Lee2012), because the newest technologies require close cooperation, since today the success of one product depends on the contributions of many experts in different fields. In addition, gaining access to knowledge and the ability to innovate are often the primary aims of the creation and operation of interorganizational networks (Nambisan & Sawhney, Reference Nambisan and Sawhney2011; Chunlei, Rodan, Fruin, & Xiaoyan, Reference Chunlei, Rodan, Fruin and Xiaoyan2014). Therefore, the key feature of organizational structures in the modern economy is networking, understood as participation in interorganizational networks and the ability to reconfigure the systems of these networks (Moensted, Reference Moensted2010; Mukkala, Reference Mukkala2010; Van Geenhuizen & Nijkamp, Reference Van Geenhuizen and Nijkamp2012).

The organizational structure of high-tech enterprises that adopt a structural ambidextrous approach can be described as eclectic or hypertext (Nonaka & Takeuchi, Reference Nonaka and Takeuchi1995; Menguc & Auh, Reference Menguc and Auh2010). During innovation exploration, when new ideas are generated and new technologies are developed, the structure should be adaptable and have organic qualities (Galbraith, Downey, & Kates, Reference Galbraith and Kazanjian2002). Conversely, during innovation exploitation, when production, trade, and financial tasks of a repetitive and routine nature are performed, the features of the organizational structure need to be more bureaucratic to ensure high efficiency (Hatch, Reference Hatch1997; Daft, Reference Daft2007). Such a model of an ambidextrous organizational structure corresponds mainly to a high-tech company that runs both its own inventions and production and/or provides high-tech services (such enterprises were the subject of the research). In companies operating as research laboratories with external commercialization, the organizational structure covers mainly the exploration phase.

The strategy–structure nexus in the phases of innovation exploration and innovation exploitation

The relationship between strategy and organizational structure continues to be a significant and valid issue in strategic management (Galan & Sanchez-Bueno, Reference Galan and Sanches-Bueno2009). Chandler (Reference Chandler1962), who advanced the thesis that structure follows strategy, was a forerunner in research on this relationship. Numerous subsequent studies have supported Chandler’s proposition that strategic decisions and choices have a strong impact on and bring about changes in organizational structure (e.g., Rumelt, Reference Rumelt1974; Galbraith & Kazanjian, Reference Galbraith, Downey and Kates1986; Hill & Jones, Reference Hill and Jones1992; Lament, Williams, & Hoffman, Reference Lament, Williams and Hoffman1994). However, others have argued that this relationship can be reversed, so that ‘strategy follows structure’ (e.g., Ansoff, Reference Ansoff1979; Hall and Saias, Reference Hall and Saias1980; Fredrickson, Reference Fredrickson1986; Mintzberg, Reference Mintzberg1990; Russo, Reference Russo and Vurro1991).

Due to the interaction between the strategy and the organizational structure and considering the differences between exploration and exploitation innovations, I propose two hypotheses.

Hypothesis 1: During the phase of innovation exploration, the impact of organizational structure on strategy is stronger than the impact of strategy on organizational structure.

In this phase, the organizational structure has to be organic to develop technologies, innovations, and knowledge as resources, and enhance the organization’s ability to take advantage of opportunities (related to strategic exploration).

On the assumption that the foundation of the strategy of high-tech firms in the exploration phase of innovation consists of the development of technologies, innovations, and knowledge as resources, and the ability to take advantage of opportunities, the organizational structure ought to be conducive to such development. High flexibility in the organizational structure in the phase of innovation exploration can lead to greater motivation and more opportunities to generate new ideas (March, Reference March1991; Raisch, Birkinshaw, Probst, & Tushman, Reference Raisch, Birkinshaw, Probst and Tushman2009; Bergfors & Lager, Reference Bergfors and Lager2011). This is because the organic structural features – a loose hierarchy, low standardization, nonfixed assignment of tasks, high decentralization, and low formalization – can lead to an increase in the creativity of employees and the development of talents and abilities to develop new knowledge (Andriopoulos & Lewis, Reference Andriopoulos and Lewis2009; Tushman, Smith, Wood, Westerman, & O’Reilly, Reference Tushman, Smith, Wood, Westerman and O’Reilly2010).

Conversely, the lack of flexibility in the organizational structure (i.e., a more bureaucratic structure) in the phase of innovation exploration can inhibit creativity and reduce innovation and entrepreneurship (Hagel & Brown, Reference Hagel and Brown2005; Daft, Reference Daft2007), thereby counteracting the development of a pool of redundant key resources that are required to take advantage of fleeting opportunities.

It can be concluded that such a strategy, understood as a continuous and dynamic process of making choices in conditions of uncertainty and of maintaining redundant development potential in order to take advantage of opportunities, requires organic and flexible organizational structures at the initial stage. However, it is the maintenance of this flexibility as the firm develops and grows that becomes a determinant of the implementation of such a strategy. An inappropriately rigid organizational structure may restrict strategic changes, reducing the firm’s adaptive capacity and thus its ability to take advantage of opportunities; hence in this phase the impact of structure on strategy would appear to be greater than the impact of strategy on structure.

Hypothesis 2: During the phase of innovation exploitation, the impact of strategy on organizational structure is stronger than the impact of organizational structure on strategy.

The emergent product–market strategy forces changes to particular features of the organizational structure, which are conducive to operational efficiency and the performance of routine tasks.

A product–market strategy is determined, extended, and refined by the full use of a firm’s existing competencies and results from a company’s exploitation of resources and taking advantage of opportunities. In this case, the strong impact of strategy on organizational structure is evident (Chandler, Reference Chandler1962), and it becomes necessary to implement appropriate structural changes. On the other hand, the effect of organizational structure on strategy manifests itself in the capacity of the structure to make these changes (Mintzberg, Reference Mintzberg1990). Therefore, the subunit of the organizational structure concerned with innovation exploitation and the performance of routine activities (i.e., financial, production, trade, etc.) must also have a degree of flexibility and adaptability, even though its main task is to stabilize the business and achieve operational efficiency.

Different in nature, the phases of innovation exploration and exploitation result in various impacts of strategy on organizational structure and vice versa. It should be also noted that many exogenous and endogenous factors influence the relationship between the elements of strategy and of organizational structure in high-tech enterprises. These factors affect each of these two elements individually as well as their interrelations with each other. This paper focuses specifically on the latter, namely, the impact that the elements of strategy and structure have on each other. In order to test the above hypotheses in relation to high-tech enterprises, a survey was conducted of 61 selected companies in Poland in 2011. The following section describes the sample and the methods of data collection and analysis.

Methods

Sample

For the study, I selected participants on the basis of two criteria

-

∙ That the company belonged to the high-tech enterprise sector (according to the OECD classification – sectoral approach, i.e., high-tech industries as manufacturers of basic pharmaceutical products and pharmaceutical preparations, manufacturers of computers, electronic and optical products, and manufacturers of air, spacecraft, and related machinery; and high-tech knowledge-intensive services as telecommunications, computer programming, consultancy, and related activities, information service activities, scientific R&D (High-technology and knowledge based services aggregations based on NACE Rev.2., 2012).

-

∙ That the company was classified as a medium (over 49 employees) or large enterprise (over 249 employees) (the act on freedom of economic activity, Polish legislation, 2004). Medium and large enterprises were selected because their organizational structures are more complex and formal.

I selected the companies from the Teleadreson databaseFootnote 3 on the basis of these criteria. From a total of 689 medium and large high-tech enterprisesFootnote 4 , I invited 180 companies to take part in the surveyFootnote 5 . In total, 61 agreed to participate: 24 from the information technology and telecommunications industries, 13 from the pharmaceutical industry, and 24 from other segments in the high-tech sector. In total, 47 of these companies were classified as medium enterprises and 14 as large enterprises. All 61 companies were based in Poland during the study period; 29 operated solely in Poland, and 32 operated globally. Each of the companies had a R&D department. The companies were characterized by a high level of innovation, rapid of innovation, and a high proportion of scientific and technical staffFootnote 6 ; in short, they shared many characteristics of high-tech enterprises (NewCronos, 2009).

Data collection and measurements

I conducted the survey using an interview method and within it a standardized interview technique. I used a standardized interview questionnaire (closed questions) as the research tool. The interview technique made it possible for the interviewed participants and I to come to an agreement as to the understanding of various concepts and phenomena (Zikmund, Babin, Carr, & Griffin, Reference Zikmund, Babin, Carr and Griffin2013). The respondents were CEOs and the company was the level of analysis. I interviewed a number of CEOs (two to three persons) who expressed their opinions (sometimes varying) in relation to the questions asked. However, in their interaction with me, they agreed on a common position, which I marked in a prepared questionnaire. Therefore, the answers given do not reflect the opinion of a single CEO, but opinions of the board and top management in the company.

The interview questionnaire included 65 alternative, disjunctive, and conjunctive questions on the following five areas:

-

1. the characteristics of the company as a high-tech enterprise and an assessment of the conditions of its development;

-

2. the identification of features of the company’s strategy;

-

3. the identification of features of the organizational structure;

-

4. the identification and assessment of the relationship between strategy and organizational structure; and

-

5. the CEO’s assessment of the management of the strategy–structure relationship.

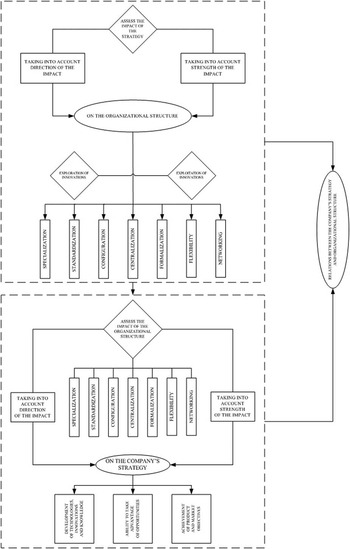

This paper presents an analysis of the survey results regarding the fourth area under consideration (i.e., the relationship between strategy and organizational structure). The algorithm used to identify the interrelations between strategy and organizational structure is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 The algorithm used to identify the relations between strategy and organizational structure

The extant literature suggests that organizational structure has multiple features and it is through the lens of these features, and not the specific types, that the organizational structures of high-tech companies were studied. Researchers from Aston University in Birmingham (Pugh & Hickson, Reference Pugh and Hickson1976) identified the features of organizational structure as specialization, standardization, configuration, centralization, and formalization. Damanpour (Reference Damanpour1991) provides an extensive list of such features, including specialization, functional differentiation, professionalism, formalization, centralization, vertical differentiation, and other culture-, process-, and resource-related variables. Mintzberg (Reference Mintzberg1993) recognizes such key issues that have to be addressed in organization design as vertical and horizontal work specialization, unit (job/department) groupings, planning, control and liaison systems, vertical and horizontal decentralizing, and coordinating the company’s employees’ work. Germain (Reference Germain1996) uses specialization, decentralization, and integration to evaluate the role of organizational structure in the adoption of logistics innovation. The Strategor (2001) group employ specialization, coordination, and formalization to represent the features of organizational structure. Nahm, Vonderembse, and Koufteros (Reference Nahm, Vonderembse and Koufteros2003) hypothesize five structural dimensions as follows: the number of layers in the hierarchy, the level of horizontal integration, the locus of decision making, the nature of formalization, and the level of communication. Thus far, the literature on features of organizational structure varies widely. There is no universal agreement on the features that should be used to conceptualize organizational structure, and researchers sometimes have named similar features differently. In this study, I follow the Aston group measures (Pugh & Hickson, Reference Pugh and Hickson1976) and consider the following five of the most commonly mentioned features:

-

1. specialization, which means the sophistication level of tasks and knowledge;

-

2. standardization, which means the typicality of actions, repeatability of procedures, unwritten habits;

-

3. configuration, which means the degree of diversification of roles and positions vertically and horizontally, and coordination methods;

-

4. centralization, which means the degree of centralization of decision-making authority; and

-

5. formalization, which means the number of formal documents, rules and procedures.

Due to the dynamics of the environment and the networking paradigm (Borgatti & Foster, Reference Birkinshaw and Gupta2003; Fowler & Reisenwitz, Reference Fowler and Reisenwitz2013), I propose and add two new variables:

-

6. flexibility, which means quickness and ease of introducing changes (Verdu & Gomez-Gras, Reference Verdu and Gomez-Gras2009; Bahrami & Evans, Reference Bahrami and Evans2011; Dunford, Cuganesan, Grant, Palmer, Beaumont, & Steele, Reference Dunford, Cuganesan, Grant, Palmer, Beaumont and Steele2013);

-

7. networking, which means participation in interorganizational networks and the ability to reconfigure the systems of these networks (Moensted, Reference Moensted2010; Mukkala, Reference Mukkala2010; Van Geenhuizen & Nijkamp, Reference Van Geenhuizen and Nijkamp2012).

Based on the information from the interview and with the CEOs’ consent, I determined these structural features by assigning each of them a single variant (state), separately for the innovation exploration and innovation exploitation phases. For the sake of simplicity, I assumed two possible variants (states) for each feature, namely (1) specialization: broad or narrow, (2) standardization: high or low, (3) configuration: predominantly vertical or predominantly horizontal, (4) centralization: high or low, (5) formalization: high or low, (6) flexibility: high or low, (7) networking: independence or participation in interorganizational networks. It should be noted here that the organic structural features are reflected by broad specialization, low standardization, predominantly horizontal forms of task integration, low centralization and formalization, high flexibility (Burns & Stalker, Reference Burns and Stalker1961), and participation in interorganizational networks. The opposite states of organizational structure features reveal bureaucratic structures (Daft, Reference Daft2007).

Using the algorithm shown in Figure 1, the impact of strategy on structure was assessed in the phases of innovation exploration and innovation exploitation, in accordance with the adopted structural ambidexterity approach (O’Reilly & Tushman, 2004). I took into account both the strength of the impact and its direction, that is, the direction toward which these seven specific features of the organizational structure evolved as a result of the strategic decisions made (e.g., whether formalization increased or decreased).

I assessed also the strength and direction of the impact of the seven specific features of the organizational structure on company strategy regarding

-

1. the development of technologies, innovations, and knowledge as resources;

-

2. the ability to take advantage of opportunities; and

-

3. the product–market strategy.

This assessment also determined whether the impact of these features was positive or negative (i.e., whether the level of centralization was conducive to the development of technologies, innovations, and knowledge as resources, or whether it inhibited such development).

When I was measuring the interaction of strategy and organizational structure, I used the 5-point Likert scale (1=‘very low impact;’ 5=‘very high impact’). I used this scale to assess (1) the strength of impact of the strategy and structure on each other, (2) the strength of impact of the strategy on the highlighted features of the organizational structure, and (3) the strength and direction of the impact of the features of the organizational structure on the highlighted dimensions of the strategy. In contrast, I measured the direction of impact of the strategy on the organizational structure through the lens of the changes in the distinguished features of the organizational structure.

A comprehensive analysis of how the CEOs assessed the strength and direction of the impact of these seven features on the three areas of strategy provided a broad picture of the relationship between the strategy and the organizational structure perceived by top management.

It should be noted that, in order to account for the time factor in the evaluation of the impact of strategy on structure and vice versa, the respondents were asked to answer the questions from the perspective of at least 3 years of operation.

Analysis

The interviews conducted using the questionnaire resulted in the accumulation of a large volume of data that were subsequently organized, grouped, and analyzed. I used the statistical factors and descriptive statistics, as well as a Spearman’s correlation, the Kruskal–Wallis tests, Mann–Whitney tests, Friedman tests, and χ2testsFootnote 7 as the methods of analysis, the application of which allowed me to identify significant differences in the answers of CEOs according to the high-tech industry and company size.

It should be noted that reliance on the subjective assessments of the respondents constitutes a certain limitation (Podsakoff & Organ, Reference Podsakoff and Organ1986) with respect to the obtained results.

However, because the respondents were CEOs, it is reasonable to assume that their responses reflect the situation in their respective companies to the greatest possible extent. Moreover, I often conducted the interviews in groups of two or three CEOs, who viewed the investigated phenomena subjectively but in the course of discussion reached a common viewpoint, which I took as the variable characterizing the given issue.

Results and Discussion

First, the overall impact of strategy on structure and structure on strategy was assessed for (1) the phase of innovation exploration, and (2) the phase of innovation exploitation (Table 1). My aim here was to learn about the general feelings and opinions of the CEOs regarding the strength of the impact of the two elements, strategy and structure.

Table 1 The chief executive officers’ (CEOs) assessment of the strength of the impact of strategy on organizational structure and of the impact of structure on strategy in the phases of innovation exploration and innovation exploitation

Note. CEOs were asked to assess the strength of the impact using the 1–5 Likert scale (1=‘very low impact’; 5=‘very high impact’).

M=median; Q=quantities deviation;

![]() $${\mib{\bar{x}}} $$

=average.

$${\mib{\bar{x}}} $$

=average.

A statistically significant difference was found between respondents’ assessments concerning the mutual influence of strategy and organizational structure in the exploration and exploitation phases of innovation in the surveyed firms (H=22.321; p<.001). The pairwise comparison of the results showed the difference in results for the exploration phase of innovation to be significant at an error level of p<.01. The impact of structure on strategy (M=4) was significantly stronger than the impact of strategy on structure (M=3). In turn, in the innovation exploitation phase strategy has a stronger impact on structure (M=4) than structure on strategy (M=3). In this case, the difference is found to be significant at a higher error level (p<.05). A comparison was also made of the size of the impact of strategy on structure in the two analyzed phases, which showed that the impact was greater in the exploitation phase than in the exploration phase (M=4 vs. M=3), the difference being statistically significant (p<.05). Similarly, the comparison of the impact of structure on strategy in these two phases also revealed a statistically significant difference (p<.01) – here the impact was found to be significantly stronger in the exploration phase of innovation than in the exploitation phase (M=4 vs. M=3).

The results of the Kruskal–Wallis tests showed that there were no significant differences according to industry type and company size, which means that, irrespective of the size of the firm and the sector in which it operates, respondents always assessed the impact of structure on strategy as higher in the exploration phase of innovation, and the impact of strategy on structure as higher in the exploitation phase.

To check whether there were significant relationships between the assessments of the strength of impact of strategy on organizational structure and of structure on strategy in the exploration and exploitation phases of innovation, Spearman’s correlations were obtained (Table 2).

Table 2 Spearman’s correlations between the strength of the impact of strategy on organizational structure and of the impact of structure on strategy in the phases of innovation exploration and innovation exploitation

Note. R≥0.28 is essential with minimum p<.05 identified by bold values.

The results of the analysis showed that several relationships were significant (p<.05) and positively correlated. The strongest correlation was between the impact of strategy on organizational structure in the exploitation phase of innovation, and the impact of structure on strategy in the exploration phase (R=0.50). This means that if the impact of strategy on structure in the exploitation phase was rated as strong, then the impact of structure on strategy in the exploration phase was also rated as strong. There is also a strong positive correlation between the impact of strategy on structure in the exploration phase of innovation and its impact in the exploitation phase (R=0.49), and between the impact of organizational structure on strategy in the exploration phase and its impact in the exploitation phase (R=0.46). This means that if a respondent considered strategy to have a strong impact on organizational structure in the exploration phase of innovation, the respondent also considered its impact to be strong in the innovation exploitation phase of innovation. Similarly, if CEOs considered the impact of organizational structure to be strong in the exploration phase of innovation, that impact would also be rated as strong in the exploitation phase.

The above leads to the conclusion that in the exploration phase of innovation, even when there is a strong impact of strategy on structure, the impact of structure on strategy is stronger; conversely, in the exploitation phase of innovation, even when there is a strong impact of structure on strategy, the impact of strategy on structure is stronger. Therefore, the obtained results confirm the first part of the proposed hypotheses.

In the case of innovation exploration, the impact of strategy on the features of the organizational structure (specialization, standardization, configuration, centralization, formalization, flexibility, and networking) was greatest on the structural features of centralization, flexibility, and networking. In the case of innovation exploitation, strategy had the greatest impact on the structural features of specialization, configuration, centralization, formalization, and flexibility. Differences between the innovation exploration and innovation exploitation phases proved statistically significant in the case of specialization (χ2=13.496; p<.01), configuration (χ2=9.167; p<.05), formalization (χ2=43.928; p<.001), and networking (χ2=36.277; p<.001). This is shown in Table 3.

Table 3 The chief executive officers (CEOs) assessment of the strength of the impact of the strategy on the features of organizational structure in the phases of innovation exploration and innovation exploitation

Note. CEOs were asked to assess the strength of the impact using the 1–5 Likert scale (1=‘very low impact;’ 5=‘very high impact’). Sorting was carried out in such a way that all scores 1 and 2 for a particular relationships were classified as poor impact, score 3 as moderate impact, and scores 4 and 5 as strong impact.

N=number of companies.

Taking into account the direction of this impact (Table 4), it can be stated that in the case of innovation exploration a statistically significant difference was recorded in the impact of strategy on different variables related to structure (p<.001). Strategy mainly increased the flexibility of the organizational structure through greater specialization, less hierarchy, and more decentralization. In the case of innovation exploitation, the impact of strategy on organizational structure was very diverse, making the structure more flexible and giving it more organic qualities, as well as making it more bureaucratic. Here too, the differences in the impact on different features of structure proved statistically significant (p<.001), although the relationships were weaker. However, in many companies, the CEOs stated that the particular features of the organizational structure studied in this paper did not change as a result of the implemented strategy. Rather, the CEOs argued that the elements (strategy and structure) were matched and there was no need to change the organizational structure. Respondents indicated here that small changes were taking place in their firms all the time, but these were not significant enough to cause a radical change in any particular features of the organizational structure.

Table 4 Direction of the impact of strategy on the features of organizational structure in the phases of exploration innovation and exploitation of innovation

Note. Ep=phase of innovation exploration; Es=phase of innovation exploitation; N=number of companies.

The comparison of the direction of changes in the phase of innovation exploration with changes in the phase of exploitation revealed statistically significant differences in terms of increased flexibility of structure through a less constant division of tasks in the exploration phase (χ2=10.614; p<.01), narrower specialization of tasks in that phase (χ2=8.325; p<.05), and significantly greater flexibility of structure (χ2=8.781; p<.05).

From the analysis of the strength and direction of the impact of the features of organizational structure on strategy (Table 5), the following can be stated:

-

1. The CEOs indicated that all the features of organizational structure affected strategy.

-

2. Structure exerted the strongest impact on the development of technologies, innovations, and knowledge as resources, in particular through the structural features of specialization and flexibility (M=4). Only in isolated cases was the development of these resources hindered by structural conditions, in particular by high centralization of decisions and formal documents, rules, and procedures.

-

3. The ability to seize opportunities was improved to the greatest extent by the structural feature of flexibility, whereas high levels of centralization and formalization greatly restricted this ability.

-

4. The weakest impact of structure was observed in relation to product–market strategy. According to the interviewed CEOs, too much formalization hindered the implementation of this strategic aspect.

Table 5 The strength and direction of the impact of the features of organizational structure on strategy

Note. Chief executive officers were asked to assess the strength and direction of the impact using the scoring scale from −5 to +5, where −5=‘very high negative impact;’ −1=‘very low negative impact;’ 0=‘no impact;’ +1=‘very low positive impact;’ +5=‘very high positive impact.’ Due to the small number of companies where the impact of studied features of the organizational structure on strategy was assessed as being negative, calculation of an average and median is not methodologically correct. Therefore, in these cases only the numbers of companies were given. Moreover, the companies where there has been no impact (‘0’ score) were excluded from these calculations, which is why the numbers of companies differ in the case of networking.

Cn=centralization; Co=configuration; Fl=flexibility; Fr=formalization; M=median; N=number of companies; Nt=networking; Q=quantities deviation; Sp=specialization; St=standardization;

![]() ${\mib{\bar{x}}} $

=average.

${\mib{\bar{x}}} $

=average.

I carried out Mann–Whitney tests at this point, taking into account the states of individual features of organizational structure in the innovation exploration and innovation exploitation phases (Table 6), and the assessment of the strength and direction of the impact of individual features on the selected dimensions of strategy. It should be noted that individual structural features in the exploration phase were tested together with the evaluation of their impact on the development of technologies, innovations, and knowledge as resources, as well as on the organization’s ability to take advantage of opportunities (as these dimensions describe the strategy in this phase). The organizational structure features in the innovation exploitation phase were tested along with the evaluation of their impact on the strategy, as reflected by product–market goals.

Table 6 The chief executive officers’ (CEOs) assessment of the features of organizational structure in the phases of innovation exploration and innovation exploitation

Note. During the interview, CEOs answered individual questions about the features of organizational structure separately for the innovation exploration and innovation exploitation phases. Subsequently, I determined these features based on the obtained information and with the acceptance of the CEOs, by assigning each of them a separate single variant (state) for the innovation exploration and innovation exploitation phases.

N=number of companies.

The results of individual analyses showed statistically significant differences (p<.05) in the case of a vast majority of examined relations, which made it possible to draw the following conclusions:

-

1. The more organic the structural features (low levels of standardization, centralization, formalization, predominantly horizontal configuration, high flexibility, and participation in interorganizational networks), the more the impact of organizational structure on the development of technology, innovation, and knowledge as resources was seen as stronger and more positive.

-

2. The more organic the structural features were (broad specialization, low level of standardization, centralization, formalization, predominantly horizontal configuration, high flexibility, and participation in interorganizational networks), the more the impact of organizational structure was seen as stronger and more conducive to taking advantage of opportunities.

-

3. The greater the flexibility of organizational structure was (other features were not statistically significant, at p>.05), the more its impact on the realization of product–market goals was seen as stronger and more positive.

Overall, this study shows that in CEOs’ opinions strategy leads to changes in structure and structure leads to changes in strategy. These findings have already been presented by many other researchers (e.g., Chandler, Reference Chandler1962; Ansoff, Reference Ansoff1979; Mintzberg, Reference Mintzberg1990). However, the new approach to the problem presented here results from the specificity of the high-tech sector and the necessity to analyze these relations from the perspectives of the exploration and exploitation of innovations. Moreover, the strategy of these high-tech companies is not based on a long-term plan (this long-term plan was considered in Chandler, Reference Chandler1962). Instead, their strategy is defined in terms of strategic resources (Barney, Reference Barney2001) and the ability to take advantage of opportunities (Eisenhardt & Sull, Reference Eisenhardt and Sull2001; Davis, Eisenhardt, & Bingham, Reference Davis, Eisenhardt and Bingham2009) during the innovation exploration phase, and in terms of product–market choices in the innovation exploitation phase. In addition, the organizational structure of these companies can be characterized as structurally ambidextrous, which makes it possible for such companies to be more successful if the structure is organic in the phase of innovation exploration, and more bureaucratic in the phase of innovation exploitation (O’Reilly & Tushman, 2004; Jansen, Van den Bosch, & Volberda, Reference Jansen, Tempelaar, Van den Bosch and Volberda2005).

The adopted approach made it possible to identify new interrelations between strategy and structure. Although the sample was deliberate, making it impossible to generalize conclusions from the survey, the conducted research strongly suggests that, according to CEOs’ opinions, ‘strategy follows structure’ during the phase of innovation exploration. That is to say, structure influences the development of key resources and the ability to take advantage of opportunities in high-tech companies. The more organic the features of the organizational structure, the greater the impact of structure on strategy. Conversely, Chandler’s thesis that ‘structure follows strategy’ works in the phase of innovation exploitation, a phase that includes the performance of routine business activities. This is so because the features of organizational structure are more bureaucratic in this phase. Nevertheless, the organizational structure has to have some flexibility in order to be able to adapt to take advantage of the identified and subsequently exploited opportunities, which can in turn change the product–market objectives. Therefore, the proposed hypotheses are supported by the survey results.

Conclusion and Implications for Management Practice

An inadequate organizational structure can frustrate efforts related to development activities. In the case of high-tech enterprises, which focus on innovation and scientific and technological progress, it is often observed that the organizational structure lags behind the mission and strategy (Daft, Reference Daft2007). Hence, successful high-tech enterprises attempt to implement an organizational structure that will make it possible, on the one hand, to ensure that their employees have the necessary independence and freedom to generate new ideas and, on the other, to have the necessary control over the entire enterprise (Menguc & Auh, Reference Menguc and Auh2010). This could be achieved by separating structural subunits for exploration and exploitation, and as O’Reilly and Tushman (Reference O’Reilly and Tushman2013) suggested, each with its own alignment of people, structure, processes, and cultures, but with targeted integration to ensure the use of resources and capabilities. These different subunits should cooperate, and being integrated at the high management level, the senior team should manage the conflicts and interface issues that such a design entails (O’Reilly & Tushman, Reference O’Reilly and Tushman2008). How leaders balance the pressures of different organizational architectures and manage interfaces between exploration and exploitation is not a subject of this study. Although some scholars have taken up this issue (e.g., Lubatkin, Simsek, Ling, & Veiga, Reference Lubatkin, Simsek, Ling and Veiga2006; Jansen, Vera, & Grossan, Reference Jansen, Vera and Grossan2009; Binns, Smith, & Tushman, Reference Binns, Smith and Tushman2011) it is still an interesting direction for future research (Cao, Simsek, & Zhang, Reference Cao, Simsek and Zhang2010; O’Reilly & Tushman, Reference O’Reilly and Tushman2013).

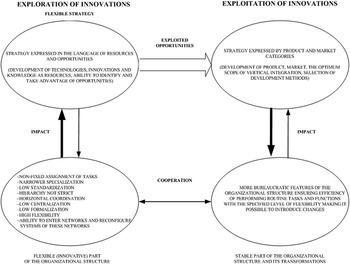

On the basis of the results of the survey (CEOs’ perceived mutual impact of structure and strategy), I propose a pattern for fitting and shaping the relations between strategy and organizational structure in high-tech companies (Figure 2), which may also be applicable for other innovative companies.

Figure 2 Pattern for shaping the strategy and organizational structure relations in high-technology enterprises

As indicated in Figure 2, in the phase of innovation exploration, strategy is expressed in terms of resources (Barney & Clark, Reference Barney and Clark2007) and opportunities (Alvarez & Barney, Reference Alvarez and Barney2007; Wood & McKinley, Reference Wood and McKinley2010). Such a strategy should be very flexible. The company must have the ability to experiment and generate ideas, have a redundancy of resources (especially technologies, innovations, and knowledge), and be able to identify and take advantage of opportunities. This type of strategy must coexist with a flexible structure characterized by highly organic features. The organic structure has been identified as fundamental in exploring and exploiting new opportunities to innovate in hypercompetitive environments (Volberda, Reference Volberda1996; Hatum & Pettigrew, Reference Hatum and Pettigrew2006). To a large extent, maintaining this flexibility determines the implementation of such a strategy (as stated above, structure has a stronger impact on strategy at the phase of innovation exploration) and promotes the development of the company. The ideas generated and accepted are then implemented and the exploited opportunities affect the product–market strategy.

In the phase of innovation exploitation, the structure can be more bureaucratic, making it possible to ensure that routine activities are performed in a highly efficient way (O’Reilly & Tushman, Reference O’Reilly and Tushman2011). However, this structure cannot be fixed because it would be difficult to make any further changes that might be necessary as a result of the emerging and exploited opportunities. Moreover, the larger, more diverse, and more complex the enterprise, the greater the need for flexibility is.

The resulting basic managerial implications for CEOs can be summed up in the following points:

-

1. Both strategy and organizational structure in high-tech enterprises should be determined from the perspective of exploration and exploitation activities.

-

2. In the exploration phase of innovation, organizational structure should have very organic features, because this strongly determines the formation of flexible resource- and opportunity-oriented strategies, rather than product–market goals.

-

3. In the exploitation phase of innovation, the strategy expressing the product–market goals, resulting from the opportunities taken, strongly determines the organizational structure, which may be more bureaucratic to ensure the efficient implementation of activities.

-

4. CEOs should continually monitor and improve the alignment of the strategy and organizational structure by implementing the necessary changes in the dynamic perspective, as well as reconcile tensions arising between exploration and exploitation activities (Raisch et al., Reference Raisch, Birkinshaw, Probst and Tushman2009), which will ensure their further development.

The discussion presented here does not cover all the issues related to the concept of strategy–structure relations, and the study has its limitations. First, the impact of strategy on structure and of structure on strategy was determined based on the opinions of CEOs, which are subjective by nature. Second, the data concern CEOs opinions, so we can only discuss the perceived mutual impact of strategy and structure. Thus, further research could be conducted into these identified relations by using additional, more objective instruments, and longitudinal analysis. It would also be interesting to undertake research on the impact of other variables (e.g., environment, size, age, life cycle, culture, technological advancement, and so on) on the direction and strength of the interrelations between strategy and organizational structure.

In conclusion, I hope that this paper will provide inspiration for continuing research on strategy, organizational structure, and strategy–structure relations as sources of innovation in high-tech companies, which are crucial to ensuring the competitiveness of particular regions and nations.

Acknowledgement

This research was supported by Ministry for Science and Higher Education Grant NN115 128434 awarded to Agnieszka Zakrzewska-Bielawska.