Introduction

Historically, health technology assessment (HTA) and improvement of healthcare quality are distinct processes. HTA has been focusing on the systematic evaluation of health technologies regarding its properties, effects, and impact, and aims to inform policy decision making (1), whereas improving the quality of health care has been important to ensure the proper use of the best available knowledge concerning the use of health care in order to improve health outcomes (Reference Friedman2). Although the purpose of these two worlds are distinct, they depend on each other and are in some cases closely aligned (Reference Luce, Drummond, Jonsson, Neumann, Sanford Schwartz and Siebert3). For example, similar data sources are used, where information from randomized clinical trials are important to inform HTA decision making but are also used in the development of clinical guidelines for quality improvement (4). Additionally, in HTA, the use of real-world data, which may originate from clinical practice, is increasingly used to complement data from clinical trials (Reference Wilk, Wierzbicka, Skrzekowska-Baran, Moćko, Tomassy and Kloc5) and also provide input on quality of care. This indicates that some overlap in the information used for quality improvement and HTA decision making seems to exist.

In both HTA and quality improvement, evidence traditionally focused in part on clinical data, including objective information on mortality and morbidity. However, patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) are becoming increasingly important in HTA (Reference Facey, Hansen and Single6) and in quality improvement (Reference Prodinger and Taylor7), because these capture outcomes that are relevant to patients and cannot be obtained through clinical measures. PROMs focus more on the patient perspective, including patients’ perspective on adverse events (AEs) or how their health-related quality of life (HRQoL) is affected due to their disease and/or treatment. The International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement (ICHOM) has developed so-called standard sets that contain lists of standardized outcomes, which they claim are relevant to patients, for a specific indication. These standard sets include both clinical data and PROMs. ICHOM could, therefore, be an initiative that could support further alignment between the worlds of quality improvement and HTA in health care.

To measure the quality of care, three different types of measures can be distinguished, namely, structure measures, process measures, and outcome measures (Reference Donabedian8). For quality improvement, all three types of measures are important; however for HTA and in ICHOM standard sets, outcome measures are most important and possibly most relevant to patients (Reference Donabedian8). Therefore, to be able to determine whether further alignment may be possible between HTA and quality of care, we will need to focus on outcome measures. This study aimed to assess the agreement between outcome measures that are collected for quality improvement in health care and for HTAs, and how both align to the outcome measures recommended by ICHOM.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional comparative analysis of ICHOM standard sets and publicly available healthcare quality measures and HTA reports published by two national healthcare institutes based in the Netherlands (NL) and the United Kingdom (UK). We selected these institutes because they are both involved in healthcare quality improvement and conducting HTAs, which is currently rare in the rest of the Western world. We specifically focused on oncology, due to the development of many new oncology treatments in recent years, the substantial uncertainty regarding the relevance of these treatments for patients, the increased toxicity that often accompanies these treatments, and the considerable costs for these treatments.

On 10 January 2020, a total of five ICHOM standard sets were identified that focus on oncological indications. These standard sets include colorectal cancer, breast cancer, lung cancer, localized prostate cancer, and advanced prostate cancer and can be accessed via the Web site of ICHOM (https://www.ichom.org/standard-sets/).

Quality measures are independently developed by the stakeholders involved, such as healthcare professionals and patients. These measures are subsequently published on the Web sites of both the Dutch National Health Care Institute (ZIN) and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). The most recently published quality measures on the Web sites of ZIN (www.zorginzicht.nl) and NICE (www.nice.org.uk) were extracted in March 2020 when these related to colorectal cancer, breast cancer, lung cancer, and prostate cancer (Supplementary Table 1). On the Web site for ZIN, quality measures are described on the so-called transparency calendar, whereas, on the Web site for NICE, quality measures are described in the quality standards published on the Web site. Since these quality measures have been developed by stakeholders, and not by ZIN or NICE, we will refer to these quality measures as published in the NL and the UK.

Both ZIN and NICE conduct HTAs of drugs, but sometimes also of other health technologies such as diagnostics and medical devices, in order to support policy decision making. To identify HTA reports, the Web sites of ZIN and NICE were searched in January 2020. The following keywords were used: colon cancer, colorectal cancer, breast cancer, lung cancer, and prostate cancer. The two most recent HTA assessments for colorectal cancer, breast cancer, lung cancer, and prostate cancer published by ZIN were extracted (Supplementary Table 1). The corresponding HTA assessments published by NICE were subsequently collected. Both ZIN and NICE conduct a relative effectiveness assessment (REA) and a cost-effectiveness assessment (CEA). NICE conducts a CEA for each reimbursement assessment, whereas ZIN conducts only a CEA when a REA indicates an added value for the new drug. The objectives of the REA and CEA are different: the REA focuses on establishing the net therapeutic benefit of an intervention (9) and the CEA allows prioritization of interventions based on the greatest improvements in health for the least cost (10). Consequently, there may be a difference in the outcome measures used, and they have, therefore, been collected separately for the REA and CEA. In this study, we refer to ZIN and NICE as HTA-NL and HTA-UK, respectively.

From all included ICHOM standard sets, quality measures and HTA reports data were extracted, and an overview of the outcome measures used was created. We considered the extraction of outcome measures to be straightforward; therefore, only one author (RK) was involved in creating this overview. From the ICHOM standard sets, all outcome measures recommended in the outcomes table were extracted. All outcome measures mentioned in each of the HTA reports were collected separately for the REA and CEA sections of the report. Regarding quality measures, outcome measures for curative and palliative care were collected as well as outcome measures regarding patient satisfaction. Outcome measures used for quality improvement that focused on prevention (e.g., smoking cessation, public awareness) were excluded.

Results

The same survival estimate was recommended in all ICHOM standard sets as used in all HTAs, namely overall survival (Table 1). In addition, ICHOM recommended the collection of other survival data, such as the cause of death and death attributed to breast cancer (Table 1). In the HTA for lung cancer, the collection of post-progression survival was additionally used (HTA-UK and HTA-NL). To measure quality improvement, survival estimates were suggested only for breast cancer (quality-UK) and lung cancer (quality-NL and quality-UK), and these included survival rates, mortality, and the percentage of deceased patients (Table 1).

Table 1. Survival estimates used for quality improvement (NL, UK), in HTA (NL, UK), and recommended by ICHOM standard sets

CEA, cost-effectiveness assessment; HTA, Health Technology Assessment; ICHOM, International Consortium of Outcome Measures; NICE, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; NL, the Netherlands; REA, relative effectiveness assessment; UK, the United Kingdom; ZIN, National Health Care Institute.

a The standard sets of advanced and localized prostate cancer are reported under prostate cancer.

b For the pharmaco-economic analysis of ZIN, the assessment of palbociclib was used because the assessment of ribocliclib and abemaciclib was referred to as the cost-effectiveness of palbociclib (Reference Lam, MacLennan, Willemse, Mason, Plass and Shepherd11).

c Information on the mortality from breast cancer was to be collected.

d The proportion of deaths among PFS events and TTD was collected.

e Information on death attributed to breast cancer was to be collected.

f The percentage of patients deceased due to lung cancer within 30 days after resection and the percentage of patients with non-small cell lung cancer deceased during or within 90 days of being treated with concurrent chemoradiotherapy was to be collected.

g Information on post-progression survival was collected.

h Information on treatment-related mortality was to be collected.

i Information on cause-specific survival was to be collected.

Different estimates for progression were used in HTAs, ICHOM standard sets, and for quality improvement (Table 2). In all HTA reports, progression free survival (PFS) was used for both REAs and CEAs, which was also used in the ICHOM standard set for colorectal cancer. Additionally, time to progression was used in the HTAs for breast cancer (HTA-UK) and prostate cancer (HTA-NL). ICHOM recommended the collection of recurrence free survival (RFS) for breast cancer and colorectal cancer, and several progression estimates for prostate cancer. As a quality measure only in the UK, the collection of progression estimates was suggested, specifically for breast cancer and colorectal cancer (Table 2). This included the proportion of people with rectal cancer with local disease recurrence and breast cancer recurrence.

Table 2. Progression estimates used for quality improvement (NL, UK), in HTA (NL, UK), and recommended by ICHOM standard sets

CEA, cost-effectiveness assessment; HTA, Health Technology Assessment; ICHOM, International Consortium of Outcome Measures; NICE, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; NL, the Netherlands; PFS, progression free survival; REA, relative effectiveness assessment; RFS, recurrence free survival; UK, the United Kingdom; ZIN, National Health Care Institute.

a The standard sets of advanced and localized prostate cancer are reported under prostate cancer.

b For the pharmaco-economic analysis of ZIN, the assessment of palbociclib was used because the assessment of ribocliclib and abemaciclib was referred to as the cost-effectiveness of palbociclib (Reference Lam, MacLennan, Willemse, Mason, Plass and Shepherd11).

c Information on breast cancer recurrence was to be collected.

d The proportion of people with rectal cancer with local disease recurrence was to be collected.

e Information on the procedures needed for local progression, biochemical recurrence, development of metastasis, symptomatic skeletal event, and development of castration-resistant disease was to be collected.

Data on Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQoL) was recommended in all ICHOM standard sets and reported in all HTAs (Table 3). HRQoL was also suggested for quality improvement for breast cancer, colorectal cancer, and prostate cancer for quality-NL, and for lung cancer for quality-UK. However, we observed a substantial difference between the use of generic and disease-specific HRQoL questionnaires between HTA, quality measures, and ICHOM. HTA agencies prefer generic HRQoL measures as these allow the calculation of utilities needed for CEAs. For the CEA of breast cancer and colorectal cancer, generic HRQoL questionnaires were used, whereas, for lung cancer and prostate cancer, only disease-specific HRQoL questionnaires were available. These disease-specific questionnaires were used to calculate generic HRQoL utility values by using the method of mapping. For REAs, on the other hand, data from both generic- and disease-specific HRQoL questionnaires was used.

Table 3. Health-related quality-of-life questionnaires used for quality improvement (NL, UK), in HTA (NL, UK), and recommended by ICHOM standard sets

CEA, cost-effectiveness assessment; EORTC QLQ-C30, the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire C30; EQ-5D, EuroQol-5 Dimension; HRQoL, health-related quality of life; HTA, Health Technology Assessment; ICHOM, International Consortium of Outcome Measures; NICE, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; NL, the Netherlands; REA, relative effectiveness assessment; UK, the United Kingdom; ZIN, National Health Care Institute.

a The standard sets of advanced and localized prostate cancer are reported under prostate cancer.

b For the pharmaco-economic analysis of ZIN, the assessment of palbociclib was used because the assessment of ribocliclib and abemaciclib was referred to as the cost-effectiveness of palbociclib (Reference Lam, MacLennan, Willemse, Mason, Plass and Shepherd11).

c The EORTC QLQ-C30 and QLQ-LC13 were used to map EQ5-D utility values.

d The FACT-P was used to map EQ5-D utility values.

HTAs preferred generic HRQoL for CEAs, whereas for quality improvement and, in all ICHOM standard sets, disease-specific HRQoL questionnaires were preferred (Table 3). Disease-specific questionnaires may be more sensitive in detecting change in HRQoL and allow a more detailed insight into specific aspects relevant for a given disease. Often, the disease-specific HRQoL questionnaire recommended by ICHOM was also used in the clinical part of the HTAs and as quality measure, for example, for breast cancer (Supplementary Table 2). However, in ICHOM standard sets, more questionnaires were recommended than used in HTAs or as quality measures, except for lung cancer where HTA-UK used three additional disease-specific HRQoL questionnaires for HTA (Supplementary Table 2). For lung cancer, it was not stated which questionnaire should be used to collect information for quality improvement (quality-UK) or in HTA, specifically REA (HTA-NL). For quality improvement of colorectal cancer (quality-NL), it was also not stated which questionnaire should be used as a quality measure.

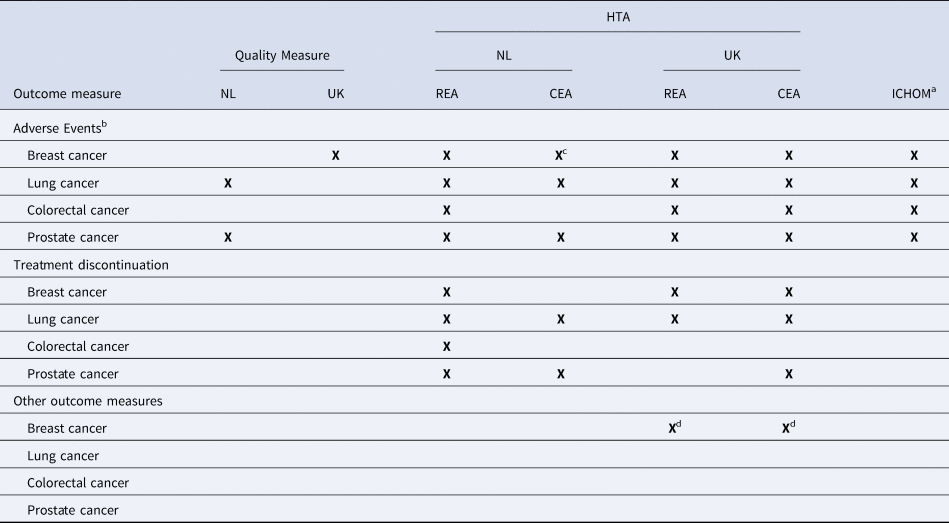

AEs or complications were included as outcome measures in the HTAs conducted by HTA-NL and HTA-UK, for both the REA and CEA, in ICHOM standard sets and as a quality measure in the UK for breast cancer, and in the NL for lung cancer and prostate cancer (Table 4). Information on treatment discontinuation was used by HTA-NL for the REAs of all included indications, whereas HTA-UK used it only in the REAs of breast cancer and lung cancer. Both HTA-NL and HTA-UK used treatment discontinuation in some CEAs, including breast cancer (HTA-UK), lung cancer (HTA-UK and HTA-NL), and prostate cancer (HTA-UK and HTA-NL). Treatment discontinuation was not recommended in any of the ICHOM standard sets, nor included as a quality measure in either the NL or the UK.

Table 4. Information on unfavorable outcomes used for quality improvement (NL, UK), in HTA (NL, UK), and recommended by ICHOM standard sets

CEA, cost-effectiveness assessment; HTA, Health Technology Assessment; ICHOM, International Consortium of Outcome Measures; NICE, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; NL, the Netherlands; REA, relative effectiveness assessment; UK, the United Kingdom; ZIN, National Health Care Institute.

a The standard sets of advanced and localized prostate cancer are reported under prostate cancer.

b In ICHOM standard sets and for quality improvement in the Netherlands, it is recommended to collect information regarding complications.

c For the pharmaco-economic analysis of ZIN, the assessment of palbociclib was used because the assessment of ribocliclib and abemaciclib was referred as to the cost-effectiveness of palbociclib (Reference Lam, MacLennan, Willemse, Mason, Plass and Shepherd11).

d For breast cancer, NICE also used information on the treatment emergent adverse events leading to deaths for the REA and safety measures for the CEA.

Other outcome measures were reported to a lesser extent, including response rate, margin status, resection, prostate-specific antigen, and patient satisfaction (Supplementary Table 3). Information on resection, for example, was mentioned only for colorectal cancer as a quality measure in the NL and UK, and in the HTAs of HTA-NL (CEA) and HTA-UK (REA and CEA), but not in the ICHOM standard set.

Discussion

Although there are differences in the specific outcome measures used in quality improvement and HTA, there is agreement in the domains applied. Information on survival, progression, HRQoL, and unfavorable outcomes seems to be important in both HTA and quality improvement. Additionally, these domains are also incorporated in ICHOM standard sets, and, therefore, may potentially be important to patients. More specifically, both in HTA and ICHOM standard sets, overall survival is used as a survival estimate, and this type of information is also important for quality improvement, although different estimates are used. Different estimates for progression are used in HTA, quality improvement (quality-UK), and ICHOM standard sets. When assessing HRQoL, there is some overlap in the disease-specific HRQoL questionnaires used; however, only in HTA, the use of generic HRQoL questionnaires is specified. Regarding unfavorable outcomes, the terms complications and AEs seem to be used interchangeably. Although there already is some alignment between HTA, quality improvement, and ICHOM, this may be further increased by using the same outcome measures for survival, progression, and unfavorable outcomes. For example, in HTA, PFS is used for colorectal cancer whereas ICHOM recommends RFS and as a quality measure in the UK, the proportion of people with local disease recurrence is suggested.

In a comparison between the outcome measures used for quality improvement in the NL and the UK, differences are apparent. For example, for breast cancer in quality-NL, the collection of HRQoL estimates is suggested (Table 3), whereas for quality-UK, the importance of AEs and patient satisfaction is stressed (Table 4 and Supplementary Table 3). Although for lung cancer, there is agreement between the two sets of quality measures on the importance of survival estimates (Table 1), for quality-NL, the collection of AEs is suggested as an addition (Table 4), whereas for quality-UK, HRQoL and patient satisfaction are added (Table 3 and Supplementary Table 3). We also show a difference in outcome measures between indications, where for instance resection estimates are suggested in both quality-NL and quality-UK for colorectal cancer, but not for any other indication included (Supplementary Table 3). These differences may be indication specific or are due to a variety of stakeholders being involved in developing these quality measures, because stakeholders will have different insights, opinions, and priorities (Reference Williamson, Altman, Blazeby, Clarke, Devance and Gargon12). Also, the role of patients in development of quality measures may be a factor , where some indications (e.g., breast cancer) may have more active patient organizations compared with others (e.g., lung cancer), or patient involvement may be limited (Reference Armstrong, Herbert, Aveling, Dixon-Woods and Martin13). This suggests that outcome measures used for quality improvement seem to be less standardized than those used in HTA. It also raises the question which outcome measures truly reflect patient preferences, as both ICHOM standard sets and measures for quality improvement have been developed with input from patient representatives (Reference Armstrong, Herbert, Aveling, Dixon-Woods and Martin13). Yet, the degree of convergence is not optimal.

This study closely relates to our previous research, comparing outcome measures used in regulatory guidelines, HTA guidelines, and ICHOM standard sets, where we showed that outcome measures relevant to patients are also relevant for regulatory and reimbursement decision making. However, some differences were apparent, because in regulatory decision making, some outcome measures (e.g., intermediate outcomes) were more easily accepted than in reimbursement decision making (Reference Kalf, Delnoij, Bouvy and Goettsch14). ICHOM standards sets may, therefore, not only help align outcome measures used in regulatory and reimbursement decision making, but also increase the alignment with outcome measures used for quality improvement. This could potentially benefit each process, as well as ensuring that information is used for multiple purposes.

Our previous study focused on outcome measures recommended in HTA and regulatory guidelines (Reference Kalf, Delnoij, Bouvy and Goettsch14); however, these may be different from the outcome measures actually available for decision making. With regard to HTA, in the guidelines of HTA-NL and HTA-UK, both overall survival and PFS are recommended. Our current study shows that both outcome measures were also provided in the HTA assessment. When focusing on HRQoL, both HTA-UK and HTA-NL recommend the use of the EQ-5D questionnaire in their guideline to conduct CEA. However, as shown in the current study, this was not always available in practice. In those cases, both HTA-NL and HTA-UK used mapping methods to calculate the EQ-5D utility values using disease-specific questionnaires. Regarding unfavorable outcomes, both HTA-UK and HTA-NL take these into account in their HTA decision making, although this is not specifically mentioned in the HTA-UK guideline. In addition, when specific outcome measures are unavailable for HTA decision making, additional data collection may be requested to allow a reassessment when more mature data are available, such as a recommendation within the Cancer Drugs Fund by HTA-UK. However, in practice, HTA agencies seem to rely on the outcome measures that are available (e.g., PFS) to allow reimbursement decision making, even when outcome measures recommended in their guidelines are unavailable (e.g., OS).

A limitation of this study is the focus on HTA-UK and HTA-NL, whereas other European countries also conduct HTAs and assess quality improvement. However, we think that this comparison is a valid start because, in other countries, HTA and assessing quality of care is done in different institutes, which makes a comparison more challenging. In addition, it is important to note that other types of measures used to determine the quality of care were excluded, that is, structure measures and process measures. Although structure and process measures asses the value to patients regarding the organization of the care process, and are important to determine the quality of care, these aspects are generally not taken into account for HTA. To illustrate, structure measures may include “the number of certified oncological surgeons working at the hospital location who treated breast cancer patient in the year of reporting,” and process measures may include “the proportion of people with rectal cancer who are offered a preoperative treatment strategy appropriate to their stage of local disease recurrence.” Because these measures are only relevant for quality improvement, we excluded these from our analysis. Finally, although we considered the extraction of outcome measures to be straightforward, having only one author involved in the extraction process could potentially lead to bias in the data collection.

One strength that can be identified in this study is the inclusion of ICHOM standard sets to assess outcomes that are believed to be relevant to patients. ICHOM standard sets indicate that several measures are important to collect, this includes measures regarding the case-mix, treatment, and outcomes. For the purpose of this study, we included all outcome measures (e.g., HRQoL, AEs, survival) reported in each ICHOM standard set. The extent to which these standard sets are patient relevant may be questioned, however, because some outcome measures recommended in ICHOM standard sets were developed with limited patient involvement (Reference Wiering, de Boer and Delnoij15). In addition, it may be difficult to convert standardized outcome measures to routinely collect these in practice (Reference Meregaglia, Ciani, Banks, Salcher-Konrad, Carney and Jayawardana16), yet ICHOM standard sets have been successfully implemented already (Reference Lagendijk, van Egdom, Richel, van Leeuwen, Verhoef and Lingsma17;Reference Niazi, Spaulding, Vargas, Chauhan, Nordan and Vizzini18). Finally, other standardized sets of outcome measures, such as ICHOM, have been developed as well. These are often referred to as core outcome sets and are reported in the Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials Initiative (COMET) database. However, these core outcome sets are not always interchangeable. For example, in the COMET database, the ICHOM standard set for breast cancer is reported, which focuses on breast cancer in general (Reference Ong, Schouwenburg, van Bommel, Stowell, Allison and Benn19). Two other core outcome sets for breast cancer are also listed in the COMET database, but one specifically focuses on outcomes relevant for autologous fat grafting in breast reconstruction and another on laboratory biomarkers (Reference Agha, Pidgeon, Borrelli, Dowlut, Orkar and Ahmed20;Reference Vanalli and Rio21). Some core outcome sets from the COMET database are comparable to the ICHOM standard sets, such as for localized prostate cancer, where some similarities and differences are apparent. More specifically, both the ICHOM standard set and one other core outcome set for localized prostate cancer recommend collecting information on OS and urinary function for example, but only the ICHOM standard set recommends outcomes related to bowel irritation and hormonal symptoms, whereas the other core outcome set recommends anxiety and depression outcomes (Reference Lam, MacLennan, Willemse, Mason, Plass and Shepherd11;Reference Martin, Massey, Stowell, Bangma, Briganti and Bill-Axelson22). Such differences may be due to the involvement of different stakeholders or stakeholders from different countries.

We observed a difference between the use of generic and disease-specific HRQoL questionnaires. HTA agencies generally prefer generic measures to conduct CEAs; however, when these are unavailable for an assessment, HTA agencies may use mapping methods to calculate utilities based on disease-specific questionnaires (10). HTA agencies do not prefer these mapping methods due to several methodological issues (10). It may, however, be possible to improve such methods or develop new methods to calculate utilities based on disease-specific questionnaires (Reference Arnold, Rowen, Versteegh, Morley, Hooper and Maskell23). This would further increase the level of alignment, because ICHOM and quality improvement mainly recommend the use of disease-specific measures. Alternatively, generic HRQoL measures may also be included in ICHOM standard sets and for quality improvement. However, these processes have different contexts and purposes, which may necessitate some differences in the outcome measures used. Our results show a multitude of HRQoL disease-specific questionnaires recommended in ICHOM standard sets, which may increase respondent burden (Reference Sharp and Frankel24). Developing a way to limit the number of questionnaires but retaining the same level of reliability may be an option to mitigate this. Our results also show that, in some cases, a few questions from a specific questionnaire were recommended, such as the recommendation to use single items of the FACT-ES for breast cancer by ICHOM, which may play a part in solving this. It is, however, unclear why only a few questions were selected and whether this would be sufficient to actually measure HRQoL. When HTA, quality improvement, and ICHOM more often recommend the same HRQoL questionnaires, it may contribute to an evidence ecosystem where the same outcome measures are used by several stakeholders.

Developing an evidence ecosystem is important to reduce costs, resources, and burden of registration in health care, as well as increase the relevance and reliability of evidence collected. It is envisioned that decision support, including guidelines and HTAs, will support clinicians, patients, and policy makers in decision making, but also inform the implementation and evaluation of healthcare improvement (4;Reference Vandvik and Brandt25). In addition, data accrued from clinical practice is more often being used in HTAs as complementary evidence (Reference Wilk, Wierzbicka, Skrzekowska-Baran, Moćko, Tomassy and Kloc5), and the same type of data could inform quality improvement as well as other parts of the evidence ecosystem. A greater level of alignment is imperative, however, to ensure that data from clinical practice needs to be collected only once and allow its use for several purposes. This may only be possible with a greater collaboration between the HTA and quality improvement societies. In addition, quality improvement may benefit from increasing consistency between outcome measures used for different oncological indications, especially when these outcome measures seem important for patients (e.g., survival, progression, unfavorable outcomes, and HRQoL) and, therefore, are arguably also important to assess regarding quality of care. Some discrepancies may remain due to the different objectives of healthcare quality improvement and HTA. These different objectives, however, seem to justify the need of outcome measures from the same domains for HTA and quality improvement. Therefore, because outcome measures from the same domains seem important for both quality improvement and HTA, a greater level of alignment may be possible. ICHOM could provide input on standardized outcome measures to support an evidence ecosystem, where quality improvement and HTA make use of the same evidence.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266462321000520.

Funding

Funding was received from the Dutch National Health Care Institute (Zorginstituut Nederland).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.