1. Introduction

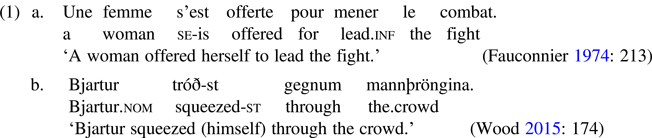

In this article, I argue that reflexive clitics express Voice, a functional head in the extended projection of the verb root, rather than a pronominal element such as D.Footnote 1 Many languages can express referential dependencies using reflexive clitics or affixes, which typically attach to verbs. An example is Romance se/si, illustrated for French in (1a). Here the anaphoric dependency between the external and internal argument roles is expressed using the reflexive clitic se and a DP antecedent, une femme ‘a woman,’ which occupies the surface subject position. Another example of a reflexive clitic is Icelandic -st, shown in (1b), which Wood (Reference Wood2015) describes as expressing an anaphoric dependency between the external argument role and the figure role introduced by a locative pP, in Talmy's (Reference Talmy, Cogen, Thompson, Thurgood, Whistler and Wright1975) sense of figure/ground. Thus, the subject Bjartur is both the agent of squeezing, and the figure being squeezed through the crowd.

Anaphoric clitics or affixes are often referred to as reflexive, although they can also express reciprocal meaning in Romance languages, among many others. Here, for the sake of consistency, I use the term anaphoric clitic to refer to a clitic involved in an anaphoric dependency, while the term reflexive clitic will be used to refer to the morphophonology used to mark anaphoric and other types of clauses.

The formal nature of reflexive clitics has been extensively debated in the literature. In Romance languages, first- and second-person anaphoric clitics (such as French me ‘1sg’, te ‘2sg’, nous ‘1pl’, and vous ‘2pl’) show syncretism with object pronouns, providing prima facie evidence for an analysis that treats them as categorically pronominal, for example as nonbranching DPs (McGinnis Reference McGinnis1998, Reference McGinnis2004; Sportiche Reference Sportiche1998). Similarly, the Icelandic reflexive clitic -st is historically related to the pronoun sik, now sig in modern Icelandic (Anderson Reference Anderson, Maling and Zaenen1990, Ottósson Reference Ottósson1992). On the other hand, anaphoric clitics also show syncretism with non-anaphoric clauses such as middles, inchoatives and unergative activity predicates, raising the issue of whether such morphology is verbal rather than pronominal. The French examples below show a middle (2a) and two inchoatives, one that alternates with a transitive (2b), and one that does not (2c).

Meanwhile, in addition to figure reflexives, Icelandic uses -st productively for unaccusative inchoatives (3a), as well as for some unergative activity predicates (3b). The -st verb in (3a) alternates with a causative transitive form lacking -st, while the -st verb in (3b) is derived from the noun djöfull ‘devil’. The ungrammatical purpose clause in (3a) indicates the absence of an implicit agent, showing that the example is inchoative rather than passive. (3b) is an impersonal passive, which is widely considered to indicate an unergative predicate.

The syntactic distribution of anaphoric clitics differs from that of DP arguments. For instance, anaphoric clitic derivations behave like intransitives in the faire-infinitive construction, as shown in (4) (Kayne Reference Kayne1975; glosses added). When embedded under causative faire, both unaccusative (4a) and unergative predicates (4b) have a postverbal subject unmarked for case, namely son amie in (4a), and Jean in (4b).

By contrast, in a transitive predicate embedded under faire, the postverbal subject is marked with the dative preposition à, as in (5a), here realized as a portmanteau item that also expresses the masculine singular determiner associated with this noun (au juge). Despite its transitive semantics, a predicate with an anaphoric clitic embedded under faire has an unmarked postverbal subject (le juge), suggesting that the predicate is formally intransitive.

The contrasts in (4)–(5) provide evidence against a simple pronominal analysis of anaphoric clitics in French – though not against more sophisticated DP analyses, such as those considered below.

Nevertheless, some arguments have been presented in favour of a DP analysis of reflexive clitics. In particular, Sportiche (Reference Sportiche1998) proposes that anaphoric clitics in French are DPs which must be overtly bound. This account correctly predicts the meaning contrast in (6). This example illustrates a French impersonal construction. The syntactic subject (il) is interpreted as an expletive, while the so-called postverbal subject (beaucoup ‘many’) occupies its base position as an internal argument within the verb phrase. In this position, it can be associated with the partitive clitic en. Sportiche observes that this sentence has a middle reading with an implicit agent, but no reflexive reading. He attributes the contrast to a requirement that the anaphoric clitic must be bound at S-structure. On the analysis that the clitic is generated as an anaphoric external argument, its antecedent (beaucoup) does not c-command it in (6) and thus does not satisfy the binding requirement.

As formulated, this analysis is incompatible with a Minimalist framework, which lacks a distinct level of S-structure and thus cannot impose an S-structure binding requirement. However, a similar Minimalist analysis has been offered for the contrast in (7). A raised subject, as in (7a), can bind an anaphoric experiencer in English, while the associate of a raised expletive, as in (7b), cannot (e.g., see Hornstein et al. Reference Hornstein, Nunes and Grohmann2005). On this analysis, the associate in (7b) does not undergo LF movement to the matrix subject position; instead, matrix T targets it for Agree, which licences Case on the DP and plural agreement on the matrix verb, but does not license anaphor binding.

(7) a. Many students seem to each other [to be in trouble].

b. There seem (*to each other) [to be many students in trouble].

A parallel analysis can be given for a contrast involving the Hebrew hitpa'el form, which closely parallels the French contrast in (6) (McGinnis Reference McGinnis1998). Reinhart and Siloni (Reference Reinhart, Siloni, Alexiadou, Anagnostopoulou and Everaert2004) describe the hitpa'el form as allowing an unaccusative interpretation, as in (8a), or a reflexive interpretation, as in (8b).

Reinhart and Siloni observe further that hitpa'el unaccusatives allow postverbal subjects, as shown in (9a), as do other unaccusatives and passives, while hitpa'el reflexives allow only preverbal subjects, not postverbal ones, as shown in (9b). McGinnis (Reference McGinnis1998) argues that the contrast in (9) arises because anaphoric hitpa'el clauses involve an anaphoric DP external argument that must be bound by a local c-commanding DP in the syntactic subject position.

Of course, this analysis requires that the anaphoric external argument not block movement of the subject from its base position to the c-commanding subject position.

McGinnis (Reference McGinnis, Pylkkänen, Harley and van Hout1999) makes the same argument regarding Icelandic -st reflexives. In the context of a non-anaphoric use of -st, an expletive-subject construction has a postverbal associate (e.g., sjómann ‘sailors’ in (10a)). If -st has an anaphoric interpretation, the associate must occupy a shifted object position, as in (10b), where the associate einhver ‘someone’ precedes the participial main verb and the VP adverb stundum ‘sometimes’. McGinnis (Reference McGinnis, Pylkkänen, Harley and van Hout1999) argues that this contrast arises because the anaphoric interpretation in (10a) involves a reflexive external argument that must be bound by a c-commanding DP, namely the associate that raises past it from an internal argument position.Footnote 2

Despite this apparent evidence from postverbal subjects, I will argue below that an anaphoric reflexive clitic is actually a Voice head, not an anaphoric external argument DP that needs to be bound by a local c-commanding argument.

A pronominal analysis has also been proposed for reflexive -st in Icelandic. Wood (Reference Wood2014, Reference Wood2015) argues that in reflexive and anticausative contexts, the Icelandic clitic -st realizes an expletive DP that merges in an argument position but cannot bear a thematic role. In a sense, the expletive DP eliminates an argument position – not by means of a lexical operation, but by merging into this position syntactically. On this analysis, the expletive DP merges in the external argument position of an anticausative, yielding an unaccusative-like structure in which the syntactic subject originates in an internal argument position (see also Schäfer Reference Schäfer2008); in a reflexive, the expletive DP merges in a vP-internal argument position (spec-p), yielding an unergative-like structure in which the syntactic subject merges as an external argument in spec-Voice.

Wood (Reference Wood2015) presents evidence that the -st clitic is an expletive argument, as opposed to a Voice head. He notes that -st occupies a different morphological position from the inchoative suffix -na, which Wood analyzes as a realization of Voice. Specifically, while -na appears between the verb root and tense morphology, as in (11a), -st appears after tense morphology, as in (11b).

Wood notes that reflexive morphology in Romance and Slavic languages also involves clitics. If the expletive-argument analysis can be successfully extended to these languages, that would support a DP analysis of anaphoric clitics in general.

However, I argue below that the cross-linguistic evidence actually supports the view that reflexive clitic morphology is verbal, not pronominal. To be specific, it expresses a Voice head in the extended projection of the verb root. I propose that the features of the Voice head underlying reflexive morphology can vary, including both unaccusative and unergative Voice, each allowing both anaphoric and non-anaphoric interpretations.Footnote 3

The remainder of the article is organized as follows. In section 2, I review evidence that anaphoric clitics are associated with an unergative derivation in Icelandic. I then argue that French has both unergative and unaccusative derivations for anaphoric clitics. Finally, I present a Voice analysis of the structures underlying the various reflexive clitic derivations under discussion, as well as the two DP analyses of reflexive clitics noted above, for comparison. In section 3, I argue for a Voice analysis of anaphoric clitics in French and Icelandic, and against the two DP analyses. In section 3.1, I argue for the Voice analysis of French anaphoric clitics, and against the external-argument analysis. I show that the unaccusative/unergative distinction in anaphoric clitic derivations undermines the binding evidence cited above for the external-argument analysis. The Voice analysis also accounts for differences in binding requirements between DP anaphors and anaphoric Voice, including how they interact with c-command and lethal ambiguity (McGinnis Reference McGinnis1998, Reference McGinnis2004). In section 3.2, I argue for a Voice analysis of Icelandic reflexive clitics, as opposed to the expletive-argument analysis in Wood (Reference Wood2014, Reference Wood2015) and Wood and Marantz (Reference Wood, Marantz, D'Alessandro, Franco and Gallego2017). These arguments are based in part on Moser's (Reference Moser2021) finding that not all figure reflexives require a pP or allow an impersonal passive, and in part on the difficulty of extending the expletive-argument analysis to other languages with reflexive clitics. Unlike the expletive–argument analysis, the Voice analysis correctly predicts that anaphoric reflexive clitics are cross-linguistically restricted to referential dependencies involving the external argument (Bouchard Reference Bouchard1984; Marantz Reference Marantz1984; Kayne Reference Kayne1988; Pesetsky Reference Pesetsky1995; McGinnis Reference McGinnis1998, Reference McGinnis2004).

2. The Voice analysis

In this section, I review evidence that anaphoric clitic derivations in Icelandic are syntactically unergative, and that French has both unaccusative and unergative anaphoric clitic derivations. I then present a Voice analysis of the various uses of reflexive clitics in these languages, along with the two DP analyses – the external-argument and expletive-argument analyses – for comparison.

Icelandic provides evidence that natural language permits unergative clauses with an anaphoric clitic. It has been argued that Icelandic allows impersonal passives with unergatives, like (12a), but not with unaccusatives, like (12b) (Zaenen and Maling Reference Zaenen, Maling, Maling and Zaenen1990, Sigurðsson and Egerland Reference Sigurðsson and Egerland2009).

We saw in the previous section that unergative activity predicates marked with -st can also occur in an impersonal passive. Moreover, Icelandic figure reflexives allow impersonal passives (Wood Reference Wood2014, Reference Wood2015). The example in (1b), repeated here as (13a), has an external argument, while (13b) is an impersonal passive, with an expletive subject, a passive auxiliary and a participial verb form.

The availability of the impersonal passive supports the analysis that figure reflexives are unergative.Footnote 4 As Wood (Reference Wood2015) notes, further evidence that anaphoric clitic derivations in Icelandic are unergative is that these derivations always have a structurally case-marked subject, even though other types of -st clauses can have a dative subject (Jónsson Reference Jónsson and Thráinsson2005: 401). This suggests that while the subject of other -st clauses can originate in an internal-argument position, the subject of anaphoric -st verbs originates in spec-Voice. On the other hand, as we will see in section 3.2, some Icelandic figure reflexives disallow impersonal passives, and thus may have an unaccusative derivation (Moser Reference Moser2021).

As noted in the previous section, French clauses with an anaphoric clitic have been argued to have an unaccusative-like derivation, in which the subject originates in a vP-internal position and moves to a position where it can bind an anaphoric external argument. However, some researchers (e.g., Labelle Reference Labelle2008) have argued instead that anaphoric clitics are associated with unergative syntax in French, as shown above for Icelandic. For example, consider the analysis of impersonal constructions with a partitive clitic and a postverbal subject, like the one in (14), based on Reinhart and Siloni (Reference Reinhart, Siloni, Alexiadou, Anagnostopoulou and Everaert2004: 172). As noted above, these allow a middle reading with an implicit agent, as in (14a), but not an anaphoric reading, with a referential dependency between the external and internal arguments of laver ‘wash’, as in (14b).

According to Labelle (Reference Labelle2008), the contrast between the two readings in (14) arises, not because the postverbal subject cannot bind a reflexive external argument (Sportiche Reference Sportiche1998), but because the anaphoric derivation has an unergative structure.

Unergatives and unaccusatives in French behave differently with respect to postverbal subjects. An unaccusative clause allows en-cliticization from a postverbal subject, as shown in (15a), but the subject of an unergative clause like (15b) resists the postverbal position and disallows en-cliticization.

If anaphoric clitics in French are associated with an unergative structure, the ill-formedness of the anaphoric reading in (14b) is explained, since this unergative structure would be incompatible with en-cliticization from a postverbal subject.

Intriguingly, Labelle (Reference Labelle2008: 870, footnote 27) observes that although the anaphoric reading is ruled out in examples like (14), it is available in superficially identical examples, as shown in (16) and (17).

The examples in (6) and (14) contrast with those in (16) and (17), suggesting that French anaphoric clitic derivations fall into two types. I propose that the first type (involving the verbs raser ‘shave’ and laver ‘wash’) is syntactically unergative, as Labelle (Reference Labelle2008) maintains. By contrast, the second type (involving présenter ‘present/introduce’ and offrir ‘offer’) is syntactically unaccusative, with a derived subject (Marantz Reference Marantz1984; Pesetsky Reference Pesetsky1995; McGinnis Reference McGinnis1998, Reference McGinnis2004; Sportiche Reference Sportiche1998). The reflexive interpretation of both unergative and unaccusative structures arises, not from a dependency between two DP positions, but from the relation between a single DP and an anaphoric Voice head, which expresses that the eventuality described by the verb phrase is self-directed.Footnote 5

The unergative structure seems to be associated with verbs classified as naturally reflexive in a variety of other languages, including Dutch and Hebrew (Everaert Reference Everaert1986, Reinhart and Siloni Reference Reinhart, Siloni, Alexiadou, Anagnostopoulou and Everaert2004). However, this does not distinguish it from the unaccusative structure, since at least for présenter, the reflexive use is also preferred to the non-reflexive use (Haiden Reference Haiden2019). Both structures also involve eventive, agentive verbs. Thus, it remains unclear what underlies the split between the two types of examples, and I leave this obviously important issue for further research. The key point, as I argue in the next section, is that the existence and properties of unergative and unaccusative anaphoric clitic derivations in French motivates a Voice analysis of anaphoric clitics.

In particular, I argue below that reflexive clitics are realizations of a Voice head. Reflexive clitic derivations are divided into two main syntactic types, unaccusative and unergative.Footnote 6 There are several subtypes of unaccusative structures. These include inchoatives, which lack both a causing eventuality and an external argument; middles, which have a causing eventuality but lack an external argument; and anaphoric unaccusatives, which have a causing eventuality and lack an external argument, but involve a semantic dependency between an internal argument and the thematic role introduced by Voice. Unergatives have both a causing eventuality and an external argument; they also allow either anaphoric or non-anaphoric Voice. In both unaccusative and unergative anaphoric clauses, the DP that enters a relation with anaphoric Voice is interpreted as participating in a self-directed eventuality.

This analysis differs in a variety of ways from other proposals in the literature. In contrasting it with approaches that treat reflexive clitics as pronouns, I focus principally on two alternative analyses. The first treats the clitic as an anaphoric external argument DP (McGinnis Reference McGinnis1998, Reference McGinnis2004). This DP is analyzed as lacking abstract Case, and thus ineligible both to move to the subject position, and to block movement of a lower DP to subject. As a local anaphor, it must be bound by the derived subject. The analysis stipulates that a Caseless DP can only be projected as an external argument, thus restricting reflexive clitics to dependencies involving this thematic role.

Adapting the external-argument analysis to the framework adopted here, we can represent it as in (18). The reflexive clitic spells out a DP external argument merged in the specifier of the Voice head, which introduces the thematic role implied by the vP. Because it lacks Case, this DP is inaccessible for movement to the subject position, and a lower DP moves to [Spec,TP] instead, where it binds the anaphoric external argument.

(18)

This analysis makes different predictions from the Voice analysis proposed here, as discussed in section 3.1 below. The Voice analysis postulates both unaccusative and unergative anaphoric clauses, making it possible to account for the evidence that some clauses with anaphoric clitics behave like unergatives. Moreover, since the Voice analysis does not postulate a binding dependency between two DP anaphors, it does not require an antecedent to c-command an anaphoric external argument in [Spec,VoiceP]. The current analysis also offers an account of the observation that well-formed anaphoric clitic derivations are exempt from a restriction on binding known as lethal ambiguity, while DP anaphors are not exempt (McGinnis Reference McGinnis1998, Reference McGinnis2004).

I also distinguish the Voice analysis of reflexive clitics from a second pronominal analysis, which treats Icelandic -st as an expletive argument DP. As noted above, this would be an expletive merged in an argument position but unable to bear a thematic role (Wood Reference Wood2014, Reference Wood2015; Wood and Marantz Reference Wood, Marantz, D'Alessandro, Franco and Gallego2017). Wood (Reference Wood2015) analyzes two types of -st clauses, which he refers to as figure reflexives (19a) and anticausatives (19b). Examples like 1b, repeated here as (19a), appear to involve a referential dependency between the external argument and an internal argument which is interpreted as the figure located relative to the ground described by a PP, while examples like (19b) appear to have a single argument, the syntactic subject.

For examples like (19a), Wood analyzes -st as an expletive argument merged in spec-p, which he takes to be the position associated with a figure role introduced by p in the environment of a suitable PP complement, as in (20). However, since -st is an expletive DP, it cannot bear the figure role. In Wood's analysis, compositional interpretation passes this unsaturated role up the tree to the next argument in VoiceP, which is the external argument. The external argument of a figure reflexive thus receives two thematic interpretations, effectively establishing a referential dependency between these two roles without binding or Agree. Since the sole argument of the clause is introduced in spec-Voice, the structure resembles an unergative clause. However, there is also an internal syntactic argument, the expletive DP, which has no semantic interpretation. The expletive -st encliticizes to the verb.

(20)

For unaccusative examples like (19b), Wood's analysis maintains that expletive -st merges in [Spec,VoiceP], as shown in (21). In this case, there is no way to pass the external argument role to a higher DP within VoiceP, so generally the sentence is interpretable only if the Voice head introduces no thematic role.Footnote 7 The resulting structure resembles an unaccusative clause, with an internal argument that merges below Voice and moves to the subject position. However, the syntactic external argument position is filled by expletive -st, which has no semantic interpretation.

(21)

The Voice analysis makes different predictions from this expletive-argument analysis of -st, as I will review in section 3.2. For one thing, the Voice analysis offers a unified account of the heterogeneous behaviour of Icelandic figure reflexives identified by Moser (Reference Moser2021). It also offers a unified analysis of reflexive clitic derivations in Icelandic and French, including an account of the key cross-linguistic generalization that a dependency involving anaphoric clitics always includes the external argument.

3. Evidence for a Voice analysis of reflexive clitics

In this section I lay out evidence for the proposed Voice analysis of reflexive clitics, contrasting it with the external-argument and expletive-argument analyses. I then briefly discuss the surface position of Icelandic reflexive clitics, a potential challenge for the Voice analysis.

3.1 Contrasting the Voice analysis with the external-argument analysis

I now turn to evidence for the Voice analysis as opposed to the external-argument analysis, including structural differences between DP binding and Voice anaphora, the absence of lethal ambiguity effects in well-formed anaphoric clitic derivations, and the interpretation of focused subjects in anaphoric clauses.

The most straightforward evidence against the external-argument analysis of anaphoric clitics is that some anaphoric clitic derivations are unergative. This was demonstrated in section 2 for Icelandic figure reflexives, which allow impersonal passives like (13b), repeated here as (22), and for certain French anaphoric clitic derivations, which disallow en-cliticization from the postverbal subject of an impersonal clause, as in (14), repeated here as (23). Both of these observations can be captured by postulating that the anaphoric derivations in question are unergative.

As reviewed in section 1, an alternative account has been proposed for the ungrammaticality of postverbal subjects in Hebrew, Icelandic and (some) French anaphoric clauses (Sportiche Reference Sportiche1998; McGinnis Reference McGinnis1998, Reference McGinnis, Pylkkänen, Harley and van Hout1999) – namely, that the subject must raise to spec-T in order to bind an anaphoric DP in the external argument position. However, we also saw that there are parallel well-formed counterparts from French, such as (16), repeated here as (24), which are incompatible with this analysis. These examples show that an anaphoric dependency can be constructed even when the subject remains in situ.

Two important consequences follow from these observations. First, if the French example in (23), and its counterparts in Hebrew and Icelandic, disallow postverbal subjects because they are unergative, this eliminates the key evidence for an anaphoric external argument in reflexive clitic derivations. Secondly, the well-formed anaphoric dependency in (24) provides direct evidence against the external-argument analysis. In (24), the postverbal subject beaucoup is not in a position to c-command and bind an anaphoric external argument. In fact, if such an anaphor did occupy [Spec,VoiceP], it would c-command the postverbal subject, which would thus be predicted to violate Principle C. For comparison, we can consider examples that clearly involve two DPs, as in (25). The postverbal DP many students cannot bind a reflexive or reciprocal anaphor in (25a), but if it raises to spec-T, it c-commands the anaphor and binding is possible, as shown in (25b).

(25) a. There seem (*to each other) [to be many students in trouble].

b. Many students seem to each other [to be in trouble].

The contrast between the ungrammatical binding dependency in (25a) and the grammatical dependency in (24) constitutes evidence against an external-argument analysis of anaphoric clitics. On the Voice analysis, by hypothesis, (24) is grammatical because the postverbal subject enters an Agree relation with anaphoric Voice; unlike an anaphoric DP, anaphoric Voice does not appear to require a c-commanding antecedent. In other words, the structural conditions on an anaphoric dependency between Voice and a DP are different from those on an anaphoric dependency between two DPs. I postulate that anaphoric Voice targets the closest accessible DP via Agree, and establishes an anaphoric dependency with it. This DP must be in the search domain of Voice, which I assume can target the nearest eligible DP it c-commands, or failing that, a DP that merges in its specifier. Crucially, the DP that establishes a dependency with anaphoric Voice need not c-command it. By contrast, a DP can establish a dependency with an anaphoric DP only by c-commanding it.

Another argument for the anaphoric Voice analysis is that well-formed anaphoric clitic derivations appear to be exempt from lethal ambiguity (McGinnis Reference McGinnis1998, Reference McGinnis2004; see also McGinnis Reference McGinnis, Kan, Moore-Cantwell and Staubs2009, Huijsmans Reference Huijsmans2015a). Lethal ambiguity is a constraint on binding that interacts with A-movement. Specifically, if one DP (X) c-commands another (Y), but Y can undergo A-movement that skips over X without entering into a multiple-specifier configuration with it, Y can bind X. This accounts for the well-formedness of a raised subject binding an anaphoric experiencer in English, as in (25b). On the other hand, if Y can only undergo A-movement over X by leapfrogging through a multiple-specifier configuration with it, then Y cannot bind X. This second case is illustrated by long passives in Albanian (Massey Reference Massey1992), described below.

In the Albanian double object construction in (26a), the indirect object (IO) c-commands the direct object (DO), so a possessive pronoun contained in the IO cannot be bound by a quantified DO. In the passive counterpart of (26a), however, the DO raises to the subject position, where it c-commands the IO, as shown in (26b). The DO bears nominative case and can bind a possessive pronoun contained in the IO. Although the raised DO in (26b) can bind a pronoun contained in the IO, it cannot bind the IO itself (27). This follows from lethal ambiguity. In order to move over the IO, the DO must leapfrog over it via a multiple-specifier configuration. This configuration blocks binding.

If lethal ambiguity applies to clitic anaphors as well, this would account for the effects of Rizzi's (Reference Rizzi and Borer1986) Chain Condition (McGinnis Reference McGinnis1998, Reference McGinnis2004). For example, consider the contrast between Italian passive double-object constructions with a full IO anaphor, which can be bound by the subject, as in (28a), and those with a clitic IO, which cannot, as in (28b). In (28a), the IO is generated below the DO and marked with the dative preposition a, so the DO can raise to subject position without leapfrogging over the IO. In (28b), however, the reflexive is an anaphoric dative clitic generated above the DO. In order for the DO Gianni to become the subject in (28b), it must leapfrog through a multiple-specifier configuration with the IO clitic, which rules out binding.

Lethal ambiguity is problematic for the external-argument analysis of anaphoric clitic derivations, especially on a theory where Voice is a phase head, and movement out of a phase must pass through a specifier of the phase head (Chomsky Reference Chomsky and Kenstowicz2001). If a reflexive external argument occupied [Spec, VoiceP] in well-formed examples, it is not clear how the lower argument could raise past it to the subject position without leapfrogging through a multiple-specifier configuration with the external argument. Even if the external argument lacked Case, locality considerations would force the lower argument to move to subject position via a specifier at the edge of the phase headed by Voice,with the external argument in another specifier of the same head.

Thus, under the external-argument analysis, the absence of lethal ambiguity effects for anaphoric external arguments is a mystery. However, it is expected if anaphoric clitics realize anaphoric Voice, not DP. Under this view, the derivation of grammatical anaphoric clitic clauses does not involve the lethal ambiguity configuration – two coindexed DPs in specifiers of the same head – but rather a DP-head relation. Thus, the absence of lethal ambiguity effects in the context of anaphoric Voice provides evidence for the Voice analysis of anaphoric clitics, and against the external-argument analysis.

Focus constructions provide further evidence against the external-argument analysis of reflexive clitics. When the subject of an anaphoric clause is focused using seul ‘only’, as in (29), it implicitly denies a set of alternatives, which can then serve as contradictions. These alternatives can covary in both thematic roles involved in the anaphoric dependency, as in (30a), but cannot vary only in the internal role, as in (30b) (Sportiche Reference Sportiche2014, Haiden Reference Haiden2019).

These findings are problematic for the external-argument analysis of anaphoric clitics. On this analysis, the focused subject would originate as an internal argument, then raise to [Spec,TP], binding an anaphoric external argument in [Spec,VoiceP]. In (30b), the contradiction varies from the assertion in (29) only in the choice of internal argument; if the focused subject is the internal argument of a semantically transitive predicate, the contradiction is expected to be felicitous. Since it is not felicitous, the external-argument analysis appears to be incorrect.

Moreover, according to Haiden (Reference Haiden2019), if the clause has an agentive subject, the implied alternatives also cannot vary only in the external argument, as illustrated by the infelicity of (31). The facts in (30)–(31) indicate that the predicate is not semantically transitive at all, but an intransitive self-directed eventuality, of which the subject is the sole argument.

These observations follow from the Voice analysis, in which (unergative or unaccusative) anaphoric Voice effectively converts a transitive predicate into an intransitive self-directed eventuality.Footnote 8

To summarize, the Voice analysis of anaphoric clitics accounts for a number of observations more successfully than the external-argument analysis does. These include the ability of postverbal subjects with en-cliticization to establish an anaphoric dependency with the external argument thematic role, despite not being in a position to bind an anaphoric external argument; the absence of lethal ambiguity effects in well-formed anaphoric clitic derivations; and the impossibility of obtaining an internal-argument reading for a focused subject. In short, the Voice analysis is empirically supported.

3.2 Contrasting the Voice analysis with the expletive-argument analysis

Like the external-argument analysis, the expletive-argument analysis treats reflexive clitics as DPs – in this case, semantically empty DPs. In this section, I argue against this approach and in favour of the Voice analysis of reflexive clitics. The Voice analysis makes different predictions regarding the argument structure of Icelandic figure reflexives, which appear to be supported (Moser Reference Moser2021). It also successfully generalizes across languages, correctly capturing the generalization that an anaphoric dependency in a reflexive clitic derivation always involves the external argument – a result that the expletive-argument analysis predicts for Icelandic figure reflexives, but which cannot be maintained in contexts where reflexive clitics have a broader distribution, as in French and other Romance languages.

Let us consider the argument structure of figure reflexives. On the expletive-argument analysis, figure reflexives have the expletive (-st) merged in spec-p, and an external argument merged in spec-Voice. Since the figure role is not saturated by the expletive -st, it passes up the tree instead. The external argument is then interpreted as saturating both the figure role introduced by p and the agent role introduced by Voice. This analysis predicts that figure reflexives will have an obligatory PP, since this is where the figure role originates. It also predicts that they will allow impersonal passives, since the structure is essentially unergative. While some figure reflexives do indeed have these characteristics, not all do (Moser Reference Moser2021).

For example, several of the verbs on Wood's list of figure reflexives have an optional PP, including troðast ‘squeeze’, böðlast ‘struggle’, dröslast ‘drag’, læðast ‘prowl/sneak’, skrönglast ‘move reluctantly’, and þvælast ‘wander’ (Moser Reference Moser2021). An example is shown in (32), where the presence of the PP gegnum mannþröngina ‘through the crowd’ is optional. The example expresses directed motion even in the absence of the PP.

Moreover, some figure reflexives disallow an impersonal passive. These include laumast ‘sneak’, ryðjast ‘barge/shove’, and klöngrast ‘clamber’ (Moser Reference Moser2021). Example (33a) shows a well-formed active clause with laumast, and (33b) the corresponding ill-formed impersonal passive.

On the expletive-argument analysis, it is not clear how to account for the facts in (32)–(33). On the Voice analysis, however, the PP does not play a critical role in licensing the figure reflexive interpretation. Instead, this interpretation is licensed by anaphoric Voice. Moreover, anaphoric Voice can be unergative or unaccusative. Thus, examples like (33) may disallow an impersonal passive because they are unaccusative.

Another challenge of the expletive-argument analysis is the difficulty of extending it to languages beyond Icelandic. One particular issue is how to account for the widely observed generalization that the referential dependency in a non-active reflexive always involves an external argument (Kayne Reference Kayne1975, Marantz Reference Marantz1984, Burzio Reference Burzio1986, Rizzi Reference Rizzi and Borer1986, Pesetsky Reference Pesetsky1995, inter alia). For example, Italian allows an impersonal si passive of a double object construction, with the DO raising to subject position past the pronominal dative IO clitic, as in (34a). However, an anaphoric clitic in this context is impossible, as shown in (28b), repeated here as (34b) (Rizzi Reference Rizzi and Borer1986).

The empirical generalization is that a well-formed anaphoric clitic derivation must involve a dependency with the external argument. As noted in section 3.1, replacing the pronominal clitic in (34a) with an anaphoric one yields a lethal ambiguity, and the derivation crashes (McGinnis Reference McGinnis1998, Reference McGinnis2004). On the Voice analysis, the referential dependency in a well-formed anaphoric clitic derivation arises from an Agree relation between anaphoric Voice and a DP. The external argument role introduced by the Voice head is referentially linked to this DP, and the resulting intransitive predicate is interpreted as a self-directed eventuality. Such a derivation would also be unavailable for (34b), which lacks an external argument.

It is not clear why an anaphoric option would be available for Voice but unavailable for other argument-introducing heads, such as the high applicative head Appl, which has also been argued to head a phase (McGinnis Reference McGinnis, Jensen and Herk2002, Reference McGinnis2004). Interestingly, a related restriction is found in reflexive-marked clauses whose external argument has an arbitrary interpretation. For example, Italian has two types of arbitrary si (Cinque Reference Cinque1988). One is restricted to the subject position of a finite clause as in (35a), while the other can occur in both finite and non-finite clauses, but must express the external argument role, as in (35b). On the analysis proposed here, these two types of si can be regarded as a nominative DP si and a Voice si, respectively. Clauses with nominative si show third-person singular finite verb agreement with the impersonal subject, as in (35a), while clauses with Voice si show agreement with the internal argument, as in (35b). The example in (35b) can be analyzed as a middle, with unaccusative Voice and no external argument, but a causative (agentive) interpretation for little v.

Given that impersonal arguments in non-finite clauses are restricted to the external argument role, it seems that the arbitrary interpretation licensed by Voice is not found with other argument-introducing heads, such as Appl – exactly as is the case for the anaphoric interpretation licensed by Voice. This difference between Voice and Appl may be related to the fact that Appl is typically associated with optional, non-core arguments. Appl also shows other characteristics of defectiveness, such as Person-Case Constraint effects, which are restricted to clauses involving an applied argument (Hanson Reference Hanson2003), arguably because of defective person-licensing features on Appl (Adger and Harbour Reference Adger and Harbour2007; McGinnis Reference McGinnis2017a, Reference McGinnis2017b).Footnote 9

It is difficult to account for this external-argument restriction under an expletive-argument analysis. No problem arises in Icelandic, where Wood (Reference Wood2014, Reference Wood2015) postulates only two positions for the merger of the expletive argument (-st): [Spec,Voice], where it bears no thematic role; and [Spec,pP], where it bears the figure role. As noted in section 2, the expletive-argument analysis maintains that when -st merges in [Spec,pP], the figure role is passed up the structure to the next higher DP, namely the external argument. Thus, the external argument generalization is maintained.

However, any attempt to extend this analysis to Romance languages faces difficulties. In Romance languages, anaphoric clitic derivations permit the external argument role to establish a referential dependency with the complement of the verb, as in (36a), or with a higher applied argument, if any, as in (36b). On the Voice analysis, these possibilities are predicted, because the anaphoric dependency arises from an Agree relation between anaphoric Voice and the most local DP in its search domain.

On the other hand, if we were instead to extend the expletive-argument analysis to French, these examples would be analyzed as involving an expletive argument in the position of the direct object in (36a), or the indirect object in (36b). Since an expletive argument cannot saturate a thematic role, the thematic role associated with the direct or indirect object position would be passed up the tree and saturated by the next DP argument, namely the external argument, yielding an anaphoric dependency between the two roles.

The problem with this analysis is that it would permit a dependency between two internal arguments as well. The thematic role that the expletive argument cannot saturate passes up the tree as a result of compositional interpretation, so in principle it could take place between any local pair of argument positions within VoiceP. Thus, for example, if an expletive argument could merge as the direct object in (37), or in (34b) above, the thematic role that it could not saturate would be passed up the tree and assigned to the indirect object, along with the role assigned by Appl. Yet, as has been widely noted, such dependencies are ruled out.

Of course, it would be possible to maintain that the expletive-argument analysis is the best analysis for Icelandic -st, and that Romance reflexive clitics simply have a different analysis. This view is reasonable to the extent that reflexives in the two languages have clearly distinct properties that would be accessible during language acquisition. For example, if it were the case that anaphoric -st in Icelandic is associated with a PP and unergative syntax, while anaphoric se in French has a wider distribution and unaccusative syntax, the two types of anaphoric clitics could plausibly be given different analyses. However, the distinction between the two languages turns out not to be so clear-cut: both languages appear to have both unergative and unaccusative anaphoric clitic derivations, and not all Icelandic figure reflexives appear to require a PP. This suggests that a more unified analysis of reflexive clitics in the two languages is desirable.

That said, there is a class of Icelandic verbs that behaves as predicted by the expletive-argument analysis, including brjótast ‘break (into/out of)’, dröslast ‘drag’, and staulast ‘totter (along)’ (Moser Reference Moser2021). On a directed-motion reading, such verbs require a PP, as shown in (38a), and allow an impersonal passive, as in (38b).

On the expletive-argument analysis, the PP in these examples is required in order to generate the figure role underlying the figure reflexive reading. However, as we have seen, with other verbs the figure reflexive reading can exist in the absence of a PP. Thus, it is possible that the PP is required with this class of verbs for some other reason. For example, some verbs may require a path to be specified in order to obtain a directed-motion reading (McGinnis and Moser Reference McGinnis, Moser, Hernández and Emma Butterworth2020). Perhaps it is the contribution of a path component, and not the contribution of a figure role, that makes the PP obligatory in these cases. Prima facie, it seems plausible that a root meaning ‘break’, as in (38), would require a path PP for a directed-motion reading, while roots meaning ‘prowl’ (32) and ‘sneak’ (33) would be sufficient to license this reading without a path PP.

Let us tentatively adopt this hypothesis, and postulate that figure reflexives that require a PP have the same structural analysis as other anaphoric unergatives: the subject merges as the specifier of an anaphoric unergative Voice head, expressing that the eventuality denoted by the vP is self-directed. The internal argument found with transitive uses of the verb, like blýöntunum ‘the pencils’ in (39), is simply not projected.

As for the figure reflexives that are incompatible with the impersonal passive, like laumast in (33b), I leave a full account of these for further research. If they are unaccusative, as suggested here, then their subject moves from an internal argument position. If this is possible, then there is no clear account of why anaphoric -st clauses never have dative subjects, as noted in section 2 above. The distribution of the various kinds of reflexive-marked Voice would also need to be lexically restricted, since reflexive clitic derivations are not highly productive in Icelandic, as they are in French and other Romance languages. For example, an unaccusative -st reflexive (in this case, with a middle reading) cannot be based on a transitive verb like myrtist.

While several aspects of the analysis require further investigation, there are compelling reasons to support a Voice analysis of reflexive clitics in Icelandic and French. First, it explains how the structural conditions on referential dependencies in anaphoric clitic derivations differ from the conditions on referential dependencies between DPs. Second, it accounts for the distinction between unaccusative and unergative anaphoric clitics, which cuts across languages and thus supports a cross-linguistically unified analysis.

3.3 A potential challenge for the Voice analysis

One argument that has been advanced against a Voice analysis of reflexive clitics (Wood Reference Wood2015, Moser Reference Moser2021) is that the clitic sits outside tense and agreement morphology, as illustrated in (11b), repeated here as (41a). Past-tense marking and phi-agreement with dyrnar ‘the door’ is reflected in the verbal suffix -ðu, which is followed by the reflexive clitic -st. Note that dyrnar triggers plural agreement because it is formally plural. By contrast, the anticausative suffix -na, which Wood analyzes as a Voice suffix, precedes tense and agreement marking, as shown in (11a), repeated here as (41b).

Since Voice structurally intervenes between the verb and the inflectional heads associated with tense and agreement, it is not immediately obvious how a Voice analysis of -st would account for the morpheme order in (41a). Wood notes that for some speakers, -st can also sit outside a second-person imperative weak pronoun (Kissock Reference Kissock1997, Thráinsson Reference Thráinsson2007: 285).

On the assumption that a complex verb is formed by local head-to-head movement or morphological merger, a pronominal analysis of -st provides a more straightforward account of its position than a Voice analysis does. A Voice analysis would either involve cliticizing the -st head to a higher position before movement of the root-verb complex [√root-v] to T, or else head-movement yielding the complex head [√root-v-Voice-T], followed by Voice cliticization to the right edge of the complex head. I am unaware of any motivation for either of these analyses. On the other hand, clitics do often have idiosyncratic ordering properties that a syntactic analysis alone cannot capture (Auger Reference Auger1994, Bonet Reference Bonet1995, Huijsmans Reference Huijsmans2015b).

A detailed analysis of French and Icelandic reflexive clitic morphology is beyond the scope of this article. However, if this morphology realizes a Voice head, it makes an interesting comparison to Turkish passive morphology (Perlmutter Reference Perlmutter, Jaeger, Woodbury, Ackerman, Chiarello, Gensler, Kingston, Sweetser, Thompson and Whistler1978, Özkaragöz Reference Özkaragöz, Slobin and Zimmer1986). Turkish has double passives, in which both the external argument and an internal argument have an impersonal interpretation. The passive suffix is doubled, with allomorphy distinguishing the final consonants of the two suffixes, as in (42). Note that both suffixes come between the verb root and the suffix indicating tense and agreement. Nevertheless, it has been argued that only one of these suffixes realizes a Voice head, while the other is an impersonal pronoun (Legate et al. Reference Legate, Akkuş, Šereikaitė and Ringe2020, Zhaksybek Reference Zhaksybek2021).

Given the similar semantics of impersonal pronouns and passive Voice, it seems likely that the morphology expressing them is susceptible to historical reanalysis, leading to structures that may look like Voice but involve a pronoun, as in Turkish – or may look like a pronoun but involve Voice, as suggested in section 3.2 for Italian impersonal si in non-finite clauses. If Voice also has anaphoric varieties, as proposed here, then we would expect the same tendency for reanalysis to occur between reflexive pronouns and anaphoric Voice, again leading to morphologically opaque structures. In other words, while reflexive clitics in Icelandic and French may not occupy typical positions for Voice morphology, this is arguably not a fatal problem for the Voice analysis, but simply a direction for further research.

4. Conclusions

In this article I have presented an analysis of reflexive clitics that treats them as realizations of unaccusative or unergative Voice, not as anaphoric or expletive DPs. I have argued that this analysis successfully predicts a range of observations, including the possibility of an anaphoric dependency between the external argument role and a postverbal subject in French; the absence of lethal ambiguity effects in well-formed anaphoric clitic derivations; the existence of unergative anaphoric clitic derivations; the interpretation of focused subjects in anaphoric clitic derivations; the existence of Icelandic figure reflexives that lack a PP or disallow impersonal passives; and the restriction of anaphoric clitics to dependencies involving an external argument. French, Icelandic, and Hebrew reflexive clitic derivations are all analyzed as including both non-anaphoric unaccusatives and anaphoric unergatives; French and (to a more limited extent) Icelandic are also analyzed as having unaccusative anaphoric clitic derivations. The proposed analysis offers an account of reflexive clitics that captures both their diverse uses within a given language, and their parallel uses across languages.