A critical first step toward building and testing a theory of the property rights gap is constructing a measure of the gap and gathering comparable data on that measure. This is no small feat. It represents one of the largest hurdles to understanding the enormous transformations that have occurred in the rural sector around the world over the last century. In practice, rural dwellers hold a wide panoply of rights over their property – rights that have been at times solidified and at other times radically upended or redefined. Measuring the property rights gap is complicated in good part due to this wide world of property rights.

In highly developed Western countries, the most common prevailing form of private property rights entails individual, formal ownership with few restrictions on the ability to alienate property or to capture rents or benefits from that property. This is coupled with clear property delineation. But this scenario is hardly the norm from a global perspective. Governments also own land. In some cases, they own all of a country’s land and merely lease it to individuals or grant usufruct rights over it. Many landowners around the world hold property collectively or communally rather than individually. In many countries with a private sector, the vast majority of landholders have informal property ownership.Footnote 1 These landholders either lack title to their property – they may have customary rights to property or simply be de facto owners or squatters – or they hold disputed, restricted, or encumbered titles that are not predictably recognized or upheld in courts. Many private landowners face a web of restrictions to alienability in the form of restrictions on the ability to sell, lease, or mortgage property or to use it as collateral for obtaining loans.

Scholarship on property rights reflects this wide variation in property rights. Numerous authors across disciplines as widely varied as economics, law, anthropology, and political science have grappled with making sense of differing property rights regimes and their consequences. Unsurprisingly, therefore, the study of property rights and the definitions that are employed are not monolithic.

The task at hand, however – to systematically measure and gather data on the property rights gap – is a positive rather than a normative one and therefore requires making concrete coding decisions. This in turn requires deciphering a set of common, observable, and consequential distinctions among property rights that are theoretically relevant. In short, it requires identifying a North Star and then using it to draw a map for guidance.

The goal of this chapter is precisely this: to analytically differentiate among property rights over property and then classify property rights gaps according to these distinctions. While coding many distinct dimensions of property rights and gathering data along these many dimensions would be a herculean task and risks losing the forest for the trees, drawing a mere binary distinction between complete and incomplete property rights is both insufficient and unsatisfying. I pursue a middle path that relies on the fact that property rights are a “bundle of rights” (see, for instance, Reference BeckerBecker 1977; Reference MunzerMunzer 1990) and elements within that bundle are frequently correlated.

I focus on several key aspects of property rights in constructing my measures: land formalization, defensibility, and alienability. These core aspects of property rights have been at the center of intense study and theorization of property rights for more than half a century. Focusing on them enables the construction of measures of complete property rights, partial property rights, and an absence of property rights. Property that is not formalized in any way, is indefensible, or is inalienable indicates an absence of property rights. At the other end of the spectrum, land with formal, registered title that has few consequential restrictions on alienability reflects complete property rights. Partial property rights indicate incomplete or imperfect formal ownership, consequential restrictions on alienability, or serious limits to defensibility.

The definitions I employ do not require property to be held individually for property rights to be complete. But if land is held collectively or communally, the group as a whole must at least have the option to decide whether or not its members can alienate their land.

Armed with these definitions, I detail data on both the redistribution of landed property and the property rights held by the beneficiaries of land redistribution for all countries in Latin America over the period from 1920 to 2010. I collected data on land redistribution and property rights separately from one another because property rights over land can and do change over time. These data enable the construction of various, comparable measures of the property rights gap over redistributed land for the first time. They yield the first systematic picture of rural land ownership and property rights to date for any large grouping of countries over a substantial time period.

The coding scheme that I develop for measuring the property rights gap is not unique to the land tenure structure or landholding patterns that prevail in Latin America. In fact, it can be broadly applied to countries around the world. Chapter 8 discusses property rights gaps and their consequences outside of Latin America.

2.1 The Dramatic Evolution of Property Rights in Latin America

Most Latin American countries entered the twentieth century with rural sectors guided largely by private property rights regimes. Land inequality was extreme and shaped broader social and economic inequalities. To a large degree, this was a legacy of colonial-era land grant and forced labor practices such as the hacienda, encomienda, and repartimiento systems. The hacienda system extended ownership to land to a small number of powerful colonizers through grants sponsored by viceroys, governors, and town councils or through purchases from the Crown or indigenous groups. The encomienda and repartimiento systems granted the use of massive pools of indigenous labor to colonizers. Early nineteenth-century independence movements disrupted these systems with varying degrees of success in selected areas. But in many cases the military officers who fought for independence appropriated or were assigned rights to enormous colonial tracts of land (Reference GriffinGriffin 1949, 179).Footnote 2

Frontiers and the share of publicly owned land simultaneously shrank in the nineteenth century. Public lands distribution moved largely in tandem with economic development and population growth as it has in many countries since the nineteenth century (Reference BarbierBarbier 2010).

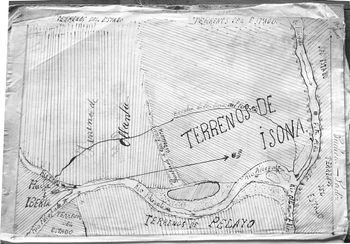

Figure 2.1 is a map that displays a public land concession to a private citizen in the eastern part of the department of Cusco in Peru. As Peru’s population grew in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, especially in the more populated regions of the Andes, individuals started pushing farther and farther down the slopes of the Andes into less settled areas. This dynamic also transpired in Bolivia, Colombia, and Ecuador.

Figure 2.1 Public land grant in Pilcopata, Peru

Note: Map accessed at the Archivo Regional de Cusco, Cusco, February 2018.

Figure 2.1 shows a land concession in the area of Pilcopata, Peru. The plot of interest, labeled terrenos de Isona (“Isona’s lands”), is bordered by several other private landholdings. Those to the left of Isona’s land in the map belonged to a landowner named Ollanta. Land next to Isona’s at the bottom of the map belonged to a landowner named Pelayo. Bordering Isona at the top and right-hand side of this map are state-owned lands (terrenos del estado). Isona was, therefore, located at the frontier of private and public land. These types of grants pushed frontiers farther out over time, often in a sequential, cascading manner as occurred here in Pilcopata, and played an important role in privatizing public lands.

The trend of distributing public lands to private individuals was reinforced by state weakness in parts of Latin America. Several wars, such as the War of the Pacific and the La Plata War, broke out among young Latin American states over boundary disputes, typically in sparsely settled areas. States consequently sought to settle these areas as buffer zones against their neighbors by granting or auctioning off public tracts of land to private individuals.Footnote 3

States also expropriated the Catholic Church and lands held in mortmain at a massive scale in the nineteenth century. The church was a key part of the colonial project and became an enormous landholder in Latin America, allying with or even comprising an important segment of the landed elite (Reference GillGill 1998). In some countries such as Mexico, it was the single largest landowner by the mid-nineteenth century (Reference Otero and ThiesenhusenOtero 1989). Liberal politicians attacked the role of the church in the state in the mid-late nineteenth centuries. The key weapon in their arsenal was expropriating church land (Albertus 2015, Ch. 2; Reference GillGill 1998, 65). In most cases, such as Mexico, governments sold off church lands to private individuals. In a few cases, like Ecuador, it initially retained a substantial portion of these lands and rented them out to private individuals.

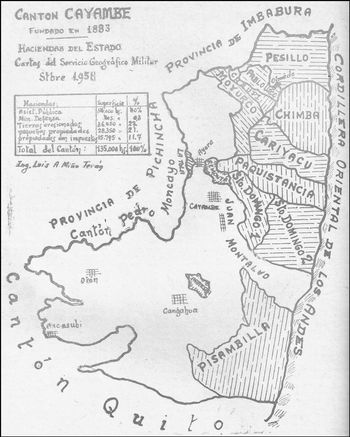

Figure 2.2 displays a map of the extent of church lands expropriated in the canton of Cayambe in the highlands of Ecuador. These lands, in the shaded areas, covered nearly half of the canton’s land area. Expropriations began in 1908 under President Eloy Alfaro’s Ley de Manos Muertos. The government confiscated clerical property and initially rented it to wealthy farmers (Reference Haney and HaneyHaney and Haney 1987, 2). The 1918 Civil Code abolished debt peonage and tied labor a decade later. The state came to control nearly 20 percent of the Sierra as a consequence of these reforms. It held the land in haciendas comprising what was known as the Asistencia Social. Older, feudal labor relations were primarily transformed into the more flexible, semifeudal huasipungaje system, whereby tenants received usufruct rights to a subsistence plot of land in exchange for a work obligation on the hacienda. Later, in the 1960s, these lands began to be distributed through land reform programs.

Figure 2.2 Expropriated church lands in Cayambe, Ecuador

Note: Map is from Reference MunicipioMunicipio de Cayambe (1970). Shaded areas are former church lands.

In some countries, particularly those where indigenous populations were large, such as Mexico, Peru, and Bolivia, private property regimes existed alongside substantial communal property structures that had evolved from precolonial systems such as the ejido or allyu. The predominantly indigenous communities that lived under these structures were progressively pushed to the margins of their economies. Landholding inequality actually became more extreme in the late 1800s as a major commodity boom spurred private landowners to appropriate indigenous lands that were increasingly valuable due to growing transportation links to external markets (Reference CoatsworthCoatsworth 2008). This dovetailed with the spread of ranching on extensive tracts of land to meet the growing European and North American demands for meat consumption and clothing. Ranchers pushed numerically smaller and sometimes seminomadic indigenous groups off more sparsely populated grasslands and wetland regions such as the Pampas of Argentina and the Pantanal in Brazil.

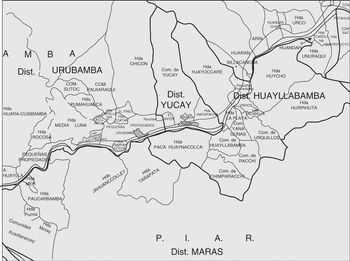

Figure 2.3 is a map that exemplifies haciendas pressing in on indigenous lands. The map displays the bimodal distribution of land in the districts of Urubamba, Yucay, and Huayllabamba in the Peruvian department of Cusco in the mid-1960s. Large haciendas ran up and down the valley in a fashion typical of the time, flanking the road that bisected them (haciendas are indicated with the abbreviation “Hda.” in the map). Narrowly squeezed between these haciendas were disparate indigenous communities (labeled “comunidades” and abbreviated “com.”) and smaller properties (labeled pequeñas propiedades). Members of these communities and smaller properties were part and parcel of the hacienda economy. Their livelihoods, security, and freedom of movement were impacted by the hacienda owners. Other communities were physically encircled by or incorporated within hacienda land.

Figure 2.3 Haciendas, indigenous communities, and small private properties in Cusco, Peru

Note: Map is a reproduction of the original, which was produced by the Ministerio de Agricultura, Oficina de Ingeniería y Catastro. Accessed from the Centro Bartolomé de las Casas, Cusco, June 2014.

To be sure, the private property rights that prevailed across much of Latin America at the outset of the twentieth century were often poorly documented and enforced by powerful landholders rather than courts. This is in part because many powerful private landholders had obtained or expanded their lands in the nineteenth century by appropriating and enclosing the lands of indigenous communities (Reference SaffonSaffon 2015). Private smallholders in most countries had relatively weak protections of their property rights or merely had de facto possession of state-owned land or private land held by larger landowners.

Beginning in the early twentieth century, however, numerous countries in Latin America undertook enormous programs of land reform that radically shifted the distribution of property ownership and upended prevailing property rights regimes. Land reform accelerated during the Cold War and in the wake of President Kennedy’s 1961 Alliance for Progress.

The most high-profile land reform programs centered on land redistribution: the undercompensated or uncompensated expropriation of land from the private sector and its redistribution to the land-poor. Regimes such as postrevolutionary Bolivia, Chile under Allende, Cuba under Castro, Mexico under the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), and Peru in the 1970s under military rule seized the property of large landowners and redistributed it to peasants. Several other governments implemented less radical programs of land negotiation: the acquisition of land from the private sector with market-value compensation or above and its subsequent transfer to the land-poor. Examples include Brazil after 1993, Costa Rica beginning in the 1960s, and Venezuela from the 1960s to the early 1990s. Still others, such as Colombia and Ecuador, focused on public land distribution: the state-directed transfer of state-owned land to settlers.

Many governments implemented several types of land reform simultaneously. For example, Colombia purchased a significant amount of privately owned land for redistribution alongside its larger program that distributed public lands.

Programs of land redistribution and land negotiation induced the biggest shock to existing property rights in Latin America. Part of this is due to their scope. Between 1920 and 2010, 167 million hectares of land transferred hands through these two types of land reform. This represents 9 percent of Latin America’s total land area. But because most land redistribution and negotiation focused on cultivable regions, as opposed to, say, jungle land deep in the Amazon or arid deserts, the total amount of land transferred through these two reform policies comprises approximately 43 percent of all cultivable land in the region.

Of equal importance, however, land reform programs introduced new property rights regimes on a massive scale. In most countries this entailed an enormous spike in informal ownership and a sort of property rights twilight zone. The private property rights regime that prevailed among large landowners was quickly wiped out but not immediately replaced by clear, stable systems of property rights. Instead, a host of provisional, partial, or informal forms of ownership and usufruct arose.

When governments put in place more stable property rights regimes, they often deviated substantially from the property rights regimes they replaced. What were these new property rights regimes? In broad terms there were four principal types: cooperative ownership with some degree of local control, communal ownership structures, direct state ownership and management with individual shares in production or wage labor, and individual ownership either without formal title or with provisional title.

Land reform beneficiaries that lived in cooperatives engaged in joint production and received a share of joint profits. Cooperative rules determined activities and benefits, and these rules in turn were created by cooperative members, the state, or both. Land could not be bought and sold by individuals within these cooperatives. In many cases, cooperatives had limited influence on precisely who constituted their membership. If the state, for instance, demanded that a cooperative incorporate new members, it was often compelled to do so. One example is the cooperatives created by Peru’s military regime in the 1970s from the land they expropriated from private landowners. Another example is the asentamiento cooperative structure that emerged in Chile from the land reform under presidents Frei and Allende.

Communal ownership structures differed from cooperatives in that land itself was held communally and its use and allocation were determined by the community. This meant that in some communities the bulk of land could be exploited individually with all or part of those profits kept individually. Typically, however, some portion of land was reserved for community use for activities like grazing animals or common farming. Land and profits could be reallocated through community decision-making. And in most cases, informal norms governed farming and other activities, such as the sharing of labor during harvests and the requirement to give a portion of time toward community service. One example of this arrangement was the ejido system in Mexico under the PRI.

In contrast to these previous scenarios, at times the state took direct ownership of private land acquired through land reform and directly managed this land with little input or decision-making from private individuals. Land reform beneficiaries in these cases were individuals who were employed on state farms and either were given some share of production revenue or were paid a wage for their labor. Examples include Cuba’s state farms created in the wake of the Cuban Revolution and the state farms created in the early 1980s by the Sandinista government in Nicaragua.

In another set of cases, land reform paved the way for individual ownership but without formal title or with provisional title. Sometimes land reform beneficiaries received land without receiving any sort of title. Other times they received land with a certificate or property title that was not linked in any way to a property registry or land cadaster. Still other times they received a provisional title that could only be converted into a formal title without liens or encumbrances after a certain time period had elapsed (typically several decades) or after they had paid a certain amount to the state for their property. Many times individuals did not comply with these regulations and transferred their land in informal markets, rendering the new owner fully to the informal sector. One example of individual land grants without formal title is Venezuela’s land reform program in the 1960s and 1970s.

Even among these broadly different types of ownership there was often blending and evolution over time. In some cases, states held the formal title to cooperatives, and in other cases, cooperative members held formal or provisional title. Sometimes title was transferred between them. States at times managed cooperatives or manipulated their membership or production decisions even when cooperatives held title. In many cases of communal ownership, communities lacked formal title to their lands. Furthermore, if and when cooperatives and communal ownership structures were broken up by the state, members often transitioned into holding land informally. Individuals in many of these cases later bought and sold land without titles.Footnote 4

In several cases, such as Colombia, the property of expropriated private landowners was transferred to land reform beneficiaries along with private property rights. But governments more typically granted former land reform beneficiaries private property rights years or decades after these individuals had initially received land – if they did so at all. In some countries, the shift of the land reform sector toward private property rights occurred after the initial land reform recipients had died off or moved to growing urban centers. In other cases, like Peru in the 1990s, informal rural transfers had occurred and states remained weak so that they had trouble extending property rights to former land reform beneficiaries. In still other cases, like Mexico in the 1990s and 2000s, property rights were strengthened but there was never a broad shift to more individual forms of ownership.

2.2 Identifying and Defining Relevant Dimensions of Property Rights

The previous section points to many different forms of property rights over redistributed land as well as changes to these property rights over time. How can we make sense of these trends in a parsimonious manner?

The key to making headway is to distill several discernible and distinct dimensions of property rights that will both capture key dynamics of the theory and aid in building empirical measures of property rights and the property rights gap. Toward that end, I now turn to unpacking the different relevant dimensions of property rights distinctions conceptually. The property rights distinctions and definitions I utilize are common and built from a longstanding literature including authors such as Reference DemsetzDemsetz (1967), Reference Feder and FeenyFeder and Feeny (1991), Reference LibecapLibecap (1993), and Reference OstromOstrom (1990).Footnote 5 It is important to note, however, that these definitions are hardly monolithic, as important scholarship in fields such as law, sociology, and anthropology makes clear (see, for example, Reference EllicksonEllickson 1993; Reference NettingNetting 1981; Reference RadinRadin 1987; Reference Rose-AckermanRose-Ackerman 1985; Reference StarkStark 1996). Neither have the definitions I employ always been historically dominant.Footnote 6

Nonetheless, coding and comparison requires that I use clear definitions and rules. It is also important from an empirical perspective not to change my property rights definitions over time. Doing so could bias empirical tests of the theory. While notions of property rights and their completeness have shifted over time, ideas regarding what constitutes “full” property rights as I engage with them have been around since before the beginning of the time period of analysis. The political consequences of incomplete property rights have also been present throughout the period regardless of how politicians form or project ideas about rights.

I begin by following Reference CommonsCommons (1968) and define a property right as an enforceable authority to undertake particular actions in a specific domain. Property rights define the actions regarding a specific item that individuals can take in relation to other individuals. The rights of certain individuals entail commensurate duties on the part of others to observe that right (Reference OstromOstrom 2003).

The specific item of interest here is land among land reform beneficiaries. Property rights over land vary in several key dimensions that this chapter will explore in depth: whether rights are privately or publicly held, whether rights are formal and defensible, whether rights are alienable, and whether rights are collective or individual in nature. To be sure, these are hardly the only dimensions of property rights over land. Rights can also vary in other ways such as how long they endure (Reference BarzelBarzel 1997), the degree to which they generate externalities by encouraging certain forms of resource use (Reference LibecapLibecap 1993), and whether enforcement is centralized or decentralized (Reference Ostrom, Schroeder and WynneOstrom, Schroeder, and Wynne 1993b).

Nonetheless, I focus on the key dimensions previously enumerated for two reasons. First, these dimensions of property rights are central to the theory and to assessing it empirically. Second, these dimensions of property rights have been debated and discussed for many decades and are at the core of some of the most influential scholarship on property rights.

Private Versus Public Ownership

A first and critical dimension over which property rights vary is whether property and the rights over it are vested in the government or in private individuals. Public ownership prevails when the government formally owns land either by constitutional stipulation or formal title and has the authority to conduct a full range of activities over land including accessing land, managing who else has access and what that access entails, withdrawing resources, and regulating and managing use. By contrast, full private ownership prevails when private individuals or groups of individuals have formal title, possess this range of rights, and have the authority to sell or lease these rights. Private property need not be held by private individuals in order to possess a full range of rights: private land can be held collectively by communal groups or cooperatives as well.

The distinction between government and private property should not be confused with public versus private goods or resources. Different types of property regimes at times have similar operational rules with respect to resource access and use (Reference Feeny, Berkes, McCay and AchesonFeeny et al. 1990). At the same time, a single type of good or resource can be governed and managed under different property regimes. Common-pool resources, for instance, can be owned and managed by government, private individuals, communal or cooperative groups, and voluntary associations (Reference Bromley, Mckean, Gilles, Oakerson and RungeBromley et al. 1992).

The rights of private owners, even if “complete,” are never absolute or unbounded. They have responsibilities to avoid harming the rights of others at a minimum (Reference DemsetzDemsetz 1967). More typically, there are additional restrictions such as the necessity of ceding property for the purposes of eminent domain. Restrictions go even further in some cases without causing direct injury to private property holders. For instance, as in contemporary South Africa, a government may legislate that the state has a right of first refusal when certain groups of private owners (such as large landowners) sell land without impinging upon the ability of sellers to name their price.

Although the distinction between public and private property is a clear one theoretically, the lines can blur at times as governments and private citizens tussle over, ignore, or encroach upon the property rights of one another. Sometimes private landowners effectively have their property rights stripped by the state. Take for instance Cuba. The government passed two major agrarian reform laws in 1959 and 1963 in the wake of the Cuban Revolution. These laws nationalized foreign-owned land, led to the state purchase of other private lands, and expropriated millions of hectares of other privately owned land and redistributed it to a new set of small private landowners. The private plots that land beneficiaries received, however, were not divisible and could only be sold to the state or transferred by inheritance (Reference ThomasThomas 1971), effectively dismantling private property rights. Another example is Venezuela’s ongoing land reform program. Individuals who successfully apply for land grants are given provisional title over their land subject to submitting a production plan to the land reform agency and undergoing a follow-up assessment that the plan has been put into place (Reference AlbertusAlbertus 2015b). However, in many cases the bureaucracy does not conduct a timely assessment, leaving land reform recipients in a state of legal limbo vis-à-vis the government for years.

In other scenarios, private property rights are effectively extended over state lands – and at times evolve into “complete” private property rights. States themselves can encourage this transformation by setting policies to privatize state lands through adverse possession or through grant-making or auction procedures. One example comes from Colombia. Colombia used frontier settlement of public lands (baldíos) beginning in the 1800s to relieve pressure on established landholdings in the Andes and Caribbean coast by encouraging surplus landless laborers and the land-poor to claim property by cultivating virgin lands. From 1900 to 2012, the state granted nearly 23 million hectares of land to petitioners through some 565,000 adjudications (Reference Villaveces and FabioVillaveces and Sánchez 2015, 23–24).

However, in some cases individuals squat on or enclose public lands illegally and over time exert effectively private property rights over such lands. This is especially common where states are weak and either cannot enforce their own property rights or cannot distinguish them. Alongside legal public land settlement in Colombia, land speculators and large landowners systematically and illegally enclosed public lands in frontier regions dating at least back to the mid-nineteenth century. They did so by leveraging their resources and political clout to illicitly obtain private land titles (Reference LeGrandLeGrand 1986; Reference SaffonSaffon 2015). Subsequent titles have built on these.

A similar dynamic played out in Brazil. There was no law regulating land access between Brazil’s independence in 1822 and 1850. The result was widespread frontier land squatting and land claiming. Brazil passed a major land law (the Lei de Terras) in 1850, which gave legal titles to all land privately occupied by 1854, including pre-independence land grants. The law simultaneously mandated that all land not yet occupied by private parties would “devolve” back to the state. Land policy was decentralized to Brazil’s newly created states when the country became a republic in 1889. Policy was thereby handed to gubernatorial administrations, which were effectively in cahoots with local agricultural elites. Many states incorporated land policy laws similar to the 1850 Land Law into their constitutions (Silva 1996). In practice, however, large, politically connected landowners continued to occupy new land that was meant to have devolved back to the state. Local power holders (coronels) selectively enforced the land law with the help of corrupt state officials and fake land titles. They prevented new smallholders from obtaining land while at the same flouting the law by occupying public lands and resisting the establishment of functioning land cadasters. Brazil’s states have at times struggled in recent decades with separating public versus private lands (via ação discriminatória) for the purposes of land reform. In some exceptional cases, such as São Paulo in the mid-1990s, state governments attempted to acquire and distribute longtime “private” lands that were judged as terras devolutas by the courts through “reclamation” (Meszaros 2013, 47), to which landowners raised quick and stiff resistance.

For the purposes of measuring the property rights gap and building and testing the theory, I seek to determine whether the beneficiaries of land redistribution programs have private property rights over their land or whether these rights are vested in, consequentially infringed upon, or withheld or underprovided by the state. This task is more straightforward than discriminating between state and private ownership over lands that have long been occupied through dubious or corrupt means outside of the land reform sector.

Importantly, when the state withholds or infringes upon the property rights of private citizens, it gains leverage over them. Activities such as investing in land, selling harvests, passing land down to heirs, obtaining loans, and even maintaining land access can all come to depend on the cooperation and support of the state – which often comes with a political price.

Formalization and Defensibility

A second dimension of variation in property rights is whether property holdings and the rights tied to them are formalized. Formalization is at the root of many conceptions of property rights, especially in economics (Reference De SotoDe Soto 2000; Reference Feder and FeenyFeder and Feeny 1991; Reference NorthNorth 1981). The formalization of land gives it legal recognition and delineates in a clear-cut fashion the nature and delimitations of property as well as the rights associated with it. This diminishes uncertainty and risk around alternative claimants or rights that may or may not be associated with holding property, such as withdrawing resources or making improvements.

Formalization is closely tied to property rights in part because of the historical and conflicting panoply of entitlements that characterize land possession and use in most countries. As the United Nations and World Bank frame it, there are often overlapping claims between the “statutory or customary, primary or secondary, formal or informal, group or individual” rights of individuals and communities to land as well as state “ownership” claims of lands for which the government itself may not fully know the extent, location, or actual use (FAO et al. 2010, 2–3). These institutions advocate sorting out and reconciling these claims through a process of adjudication and formalization, which includes “(i) the identification of all rights holders” and “(ii) legal recognition of all rights and uses, together with options for their demarcation and registration or recording” (FAO et al. 2010, 2).

The most common mechanism for formally delineating and enforcing property rights is a system of land titling supported by a public land registry and a land cadaster. Formal land titles are legal documents that serve as evidence of ownership and that delineate the physical boundaries of a parcel and the rights associated with it. Delineating and enforcing ownership also requires ensuring that more than one party does not have a legal claim to the same plot of land. Land registries address this issue by systematically recording land titles and relevant details associated with a property such as the owner’s name and the property’s location and size.

Cadasters take land registration one step farther by systematically and exhaustively cataloging both public and private landholdings and landowners through establishing and adjoining in a single record (i) the location and boundaries of landholdings and (ii) interests in landholdings, including rights and obligations. Most modern cadasters are cartographic, meaning that they record landholdings in maps. These records make land parcels and associated property rights legible to the state (Reference ScottScott 1998, 35–36).

Some of the earliest cadasters were constructed to distinguish state lands from private ones, to identify resources for making potential improvements, and to interest possible land purchasers (Reference Kain and BaigentKain and Baigent 1992, 332–33). But the broader development of the cadaster in many European countries was closely associated with the emergence of capitalist landowning and more individualized agrarian systems.

Much of the literature considers the establishment of land cadasters as expensive, complicated, and dependent on state capacity (Reference OnomaOnoma 2009; Reference SoiferSoifer 2013). Some scholars have suggested using the extent and quality of land cadasters as a proxy for state capacity (e.g., Reference D’Arcy and NistotskayaD’Arcy and Nistotskaya 2017). But in perhaps the broadest and most systematic review of land cadasters, Reference Kain and BaigentKain and Baigent (1992) demonstrate that land cadasters are actually quite old and can be created with relatively simple tools. Even the Roman Empire had created a fairly comprehensive cadaster. Partial cadasters were fairly widespread in Europe in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and the systematic mapping of rural lands was completed in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. As these authors write, “Though possession of the technical capability to survey and map individual properties at a large scale is an obvious prerequisite of state mapping, there is no case reviewed in this book where mapping was prevented by lack of skilled personnel or equipment” (Reference Kain and BaigentKain and Baigent 1992, 342).

Linking property registers to land cadasters and keeping both up to date is much more administratively complex and costly. It entails coordination between local and central administrators and a system for recording and updating ownership as land is bought, sold, subdivided, and otherwise transferred or reclassified. As Reference OnomaOnoma (2009, 36) puts it, “Once these [cadastral] surveys are carried out, hiring, training, and paying professionals with the technical ability to register and keep proper and easily accessible records on titles and deeds is… expensive. Creating tribunals to adjudicate land disputes and marshaling institutions to monitor and enforce rights across a country are also costly.” To a much larger degree than creating a cadaster in the first place, this requires infrastructural state power – the ability to penetrate society and implement policy evenly across territory (Reference MannMann 1984).

Land titles need to be not only clear but also defensible for land formalization to provide property rights security and effectively diminish uncertainty and risk associated with holding and transferring property. Those who hold legally recognized land titles need to be able to effectively call on the state for the enforcement of their rights. This requires the state to be a responsive and effective enforcer, a role it may not be able or willing to play (Reference HollandHolland 2017). It also requires disputants to recognize the legitimacy of the state as a third-party arbiter. As Reference Feder and FeenyFeder and Feeny (1991, 137) put it, “If private property rights are not viewed as being legitimate or are not enforced adequately, de jure private property becomes de facto open access.”

The gap between legality and legitimacy is part of the reason why informal property enforcement mechanisms can sometimes be equally or even more effective than formal ones at protecting landholders (Reference Goldstein and UdryGoldstein and Udry 2008).Footnote 7 This is typically the case where customary ownership is longstanding and uncontested, communities are tight-knit and stable, the state is a distant, new, or inconstant presence, and land transactions are limited. For instance, in many sub-Saharan African states where customary ownership is the norm, a relatively stable lineage of chiefs may rule in a particular area and reinforce patterns of land use. This likely helps to account for the finding that formal land titling has muted social and economic effects in many parts of Africa (Reference Brasselle, Gaspart and PlatteauBrasselle, Gaspart, and Platteau 2002).

Longstanding and uncontested informal ownership is empirically rare in Latin America. Indigenous landholders were uprooted and expropriated at a massive scale during the colonial era. This process continued, and in some places accelerated, in the postcolonial era with events such as the late nineteenth-century commodity boom and railroad penetration. Consequently, it is implausible to assume any quick reinstallation of credible, stable, and predictable informal property rights on the back of both the longstanding violation of those rights in preceding centuries followed by the violation of the rights of private landowners who were expropriated for the purposes of land redistribution back to the putatively original owners.Footnote 8

Land titles may also lack defensibility for more pedestrian reasons. Sometimes titles are not linked to a land registry; sometimes land registries are incomplete or multiple in number and partially overlapping but not updated; sometimes land registries are not linked to a land cadaster; and sometimes a land cadaster does not exist. These are abiding issues throughout much of Latin America. The question in these cases is not only one of whether the state will enforce a property right but also how the state will enforce that right. For instance, if an individual holds a land title that is not linked to any land registry, then whether it is valued more highly than any other piece of paper depends on how local courts or recorders will view it.Footnote 9 If property registers are local but there are disputes over administrative boundaries, then partially overlapping land registries can proliferate. Landowners may be subject to claims by individuals who are recorded in an alternative registry as possessing the same land if registries are not kept up to date. If land titles and land registries rely on the physical description of boundary demarcations such as trees and streams rather than on maps with geographic coordinates or simply on survey coordinates, and if the trees in question die or a stream is rerouted, then property boundary disputes can more easily arise.

This discussion suggests that land formalization and defensibility are to some extent a matter of degree. Individuals or groups in Latin America during this time tended to have private property rights that are formal and secure, rights that are imperfectly formal or that provide some degree of security while not eliminating significant uncertainty and risk, or a lack of property rights due to a lack of land title, the lack of a connection between a land title and any recording system, or the lack of any property rights enforcement.

Partial property rights, informal property rights, and indefensible property rights all provide hooks for states that seek to manage and manipulate land reform beneficiaries. The promise of economic security tied to newfound land ownership can be quickly rendered chimerical by a state that chooses not to enforce one’s property against a counterclaimant. By contrast, toeing the party line can bring complementarities to property ownership such as more predictable enforcement, agricultural credits and loans through government programs that could not be accessed through a private bank given impartial property rights, and preferential access to improvement projects such as irrigation systems.

Alienability

Alienability gives landholders the flexibility to transfer or leverage their property for a wide range of purposes. I follow Reference OstromOstrom (2003, 250) and define alienability as the right to sell or lease exclusion, management, or withdrawal rights. What are these subsidiary rights? Exclusion rights to land entail the right to determine who can or cannot gain access to land, what the nature of that access encompasses, and how that right may be transferred. Management rights entail the right to regulate internal land use patterns such as production decisions and to transform property by making improvements, such as building fences or irrigation systems. Withdrawal rights entail the right to obtain products from the land such as harvests.

The right to alienate land does not imply that individuals will exercise this right. Landowners may choose to retain their land and pass it down to the next generation rather than sell it. These same landowners, however, may want to leverage their property in ways that would not be possible without the right to alienate it. For instance, a landowner may want to migrate abroad temporarily or work elsewhere on a seasonal basis and lease their land while they are away. Or a landowner who has a bad harvest may face depleted savings and want to turn to a bank for a loan to buy seed and fertilizer or to make improvements for the next year. Land is a particularly attractive form of collateral because it is immobile and does not easily depreciate rapidly. These activities would not be possible without alienation rights over land.

Alienability facilitates liquid land markets by enabling individuals and groups to sell and lease their land. It can also contribute to wealth accumulation (Reference Alston, Libecap and MuellerAlston, Libecap, and Mueller 1999; Reference LibecapLibecap 1993) as land can be leveraged for investing in improvements and transferred to individuals who will exploit it efficiently (Reference DemsetzDemsetz 1967).Footnote 10

Alienability can also pose risks to property holders. Some land recipients may prefer inalienability as a protection from dispossession by wealthier actors or savvy competitors (see, for example, Reference Boone, Bado, Dion and IrigoBoone et al. 2019b; Reference SaffonSaffon 2015).Footnote 11 And in some group-based settings, a property transfer can harm others more than it benefits parties to the transaction (Reference EllicksonEllickson 1993, 1376).

Nonetheless, strict inalienability renders land reform beneficiaries subject to potential state manipulation. Inalienability can debilitate rural land markets as land reform beneficiaries that want to either sell or lease their land must forego this opportunity, simply abandon what they have, or try as many do to illegally sell or lease their property in informal markets (Reference DeiningerDeininger 2003). Inalienability also prevents land reform beneficiaries from using their land as collateral to obtain private-sector loans. This can stunt private credit markets and generate underinvestment in agricultural production and improvements to land with attendant negative consequences for agricultural earnings (Reference DeiningerDeininger 2003). These problems, which can mean the difference between making ends meet and absolute poverty for rural families, encourage land reform beneficiaries to turn to the state to resolve these issues for them. The state can then condition the resolution of these problems on political reciprocity or quiescence. Consequently, in many cases, land reform beneficiaries who received inalienable lands later sought the advantages of alienability when they had the option to do so.

Individual Versus Collective Ownership

Land can be held either individually or collectively among groups of individuals such as communities. Many conceptions of property rights, especially in economics, view individual ownership as a more “complete” property right than collective ownership (e.g., Reference De SotoDe Soto 2000). This view builds from a long and influential literature detailing issues linked to moral hazard and resource appropriation associated with common property regimes (Reference DemsetzDemsetz 1967; Reference North and ThomasNorth and Thomas 1973). Individual ownership, by clearly delineating who owns what, defining what rights that ownership entails, and enabling individuals to make determinative choices over decisions such as alienation or withdrawal, endows owners with a more complete and enforceable set of rights than collective ownership.

This view, however, has been successfully challenged in a host of literature. As Reference OstromOstrom (2003) makes clear, common property resources and collective property rights should not be conflated. Collectives can hold a full bundle of property rights in equal form to private individuals. It is the status and organization of the holder of property rights, as opposed to the rights themselves, that differ between private individuals and collectives.

In practice, individuals and groups often weigh the scale of property rights to land against factors such as production possibilities and risks. Reference EllicksonEllickson (1993), for instance, shows how environmental and personal security risks impacted the conversion of jointly held land to individual land at different rates in New England, Bermuda, and Utah. In a similar vein, Reference NettingNetting (1976, Reference Netting1981) shows in a study of Swiss peasants that “the attributes of the resource affected which property-rights systems were most likely for diverse purposes.” A single peasant community would often divide agricultural land into distinct family-owned parcels while simultaneously organizing grazing lands on the steep Alpine hillsides into communal property systems. In short, collective ownership may be more efficient than individual ownership under certain circumstances.

The upshot is that there is not a clear mapping between the scale of ownership and how “complete” a property right is.Footnote 12 To be sure, many forms of collective ownership have historically prevented their members from exercising full property rights. But this need not be the case. In the data I have collected I can distinguish among differences in the degree of property rights held by collectives.

One illustrative example of variation in property rights despite stasis in the collective scale of ownership comes from the ejido system in Mexico. Ejido lands distributed to communities as a whole by the PRI prior to 1992 had highly incomplete property rights. These lands were not formally titled with their distribution and ejidatarios could not legally sell, lease, partition, or mortgage their property, even with support from the community as a whole. Land could be reallocated among members of the community with sufficient community support.

The Mexican government began a land titling effort in 1992 through the Program for the Certification of Ejido Rights and Titling of Urban Plots (PROCEDE). PROCEDE granted formal and complete property rights to ejidatarios, even for the vast majority of those in ejidos who decided to maintain collective ownership of their land. It offered ejidos registration, plot delineation, and separate title to members over house plots, farm plots, and a share in the value of common lands. PROCEDE allowed ejido lands to be sold within the ejido and leased to members within or outside the ejido. It also recognized ejidos as legal bodies able to enter into contracts and joint ventures and it allowed for the full privatization of ejido land through a two-thirds vote of the ejido’s General Assembly. Given these advantages, the vast majority of ejidos voted to join PROCEDE.

2.3 Data Sources for Land Reform and Property Rights

I collected data on land redistribution, initial property rights over redistributed land, and subsequent changes in property rights through land titling and associated programs. I gathered these data directly from land reform agencies through fieldwork and from primary and secondary sources. Every country in Latin America has had at least one land reform agency or other government entity such as a Ministry of Agriculture dedicated to land reform. Land reform agencies typically collect very detailed data on land transfers and the nature of land titling. Importantly, the land titling data I collected match the theoretical focus of this book in that they capture the titling of and property rights over land allocated via land reform rather than overall land titling.Footnote 13

For some countries – Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Mexico, Peru, and Venezuela – I collected individual-level land transfer and titling data or disaggregated data at the provincial or municipal level directly from land reform agencies through fieldwork. I obtained similarly detailed transfer-level data from Brazil through an official data request to its national land reform agency. In Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, and Venezuela, fieldwork entailed working directly with bureaucrats in existing land reform agencies to learn about the process of land reform and the nature of the data that they manage and to make official data requests.Footnote 14 In Chile, Mexico, and Peru, I collected data from land reform archives housed in contemporary ministries of agriculture and agencies devoted to either property formalization or agrarian reform. In these latter cases, I met many career bureaucrats working in the land reform archives who had formerly worked for either the country’s land reform agency or Ministry of Agriculture and were therefore intimately familiar with the nature of the land reform data and the process of land grant-making.

These are the countries that had the most active and longstanding land reform programs and that consequently merited the most careful attention to data collection. Together they comprise 84 percent of all of the land redistribution recorded in Latin America from 1920 to 2010. Land reform was smaller scale and more episodic in nature elsewhere in the region, often occurring in a short, well-documented burst preceded and followed by no land redistribution at all.

For the other countries in Latin America, I collected national-level statistics or sub-national statistics from land reform agencies and ministries of agriculture, agency publications, or other government publications. This was accomplished through an official data request for Uruguay. In other cases, I obtained government documents through a wide range of libraries and archives.

Data from countries where I collected disaggregated statistics enabled comparison to national-level data in order to verify the aggregate data generation process. Finally, I used secondary sources in all cases to check the validity of government publications.

The raw data on land redistribution and land titling, while paramount, are rarely sufficient in themselves to construct measures of the property rights gap. This is because information on the nature of property rights is often embedded in law. Raw data on land transfers or land titling themselves are often not enough to assess whether those who are receiving land are also gaining each of several key property rights tied to land: formalization, defensibility, and alienability.

Generating data on property rights gaps therefore required reading and assessing legal documents associated with property rights over land. Information on the nature of property rights to land reform beneficiaries is enshrined in most cases in land reform laws that guide land redistribution and sometimes land titling. These laws may outline limits to alienability for land reform beneficiaries, may vest ownership in the state, in collective structures, or in individuals, and can outline any number of other aspects of property rights. In other cases, property rights may be defined in associated legislation. And subsequent legislation and law can of course change the nature of property rights for former land reform beneficiaries.

Creating metrics of the property rights gap also required reading literature on the role of the state in rural areas. Land beneficiaries may receive formal property rights that are serially ignored by the state, eroding defensibility. Property rights may not be registered or property registries may be highly incomplete or not linked to a land cadaster. In short, tracking the property rights of land reform beneficiaries over time requires attention to disparate types of evidence.

The data employed here represent the first systematic coding of land transfers and property rights over transferred land in a way that is cross-country comparable and which spans a considerable time period. Later in the chapter, I provide several specific examples of how I translated the data I collected into the construction of property rights gap metrics.

2.4 Constructing the Property Rights Gap

I construct two main measures for the property rights gap. One is annual and the other marks cumulative gaps over time. Each measure distinguishes between two broadly different degrees of property rights in the data: (i) the property rights gap between distributed land and at least partial property rights (i.e., partial or complete rights) over that land, as well as, separately, (ii) the gap between distributed land and complete property rights over that land. As discussed previously, property need not be individually held under the property rights definitions I employ. Full property rights can also be established over collectively held lands.

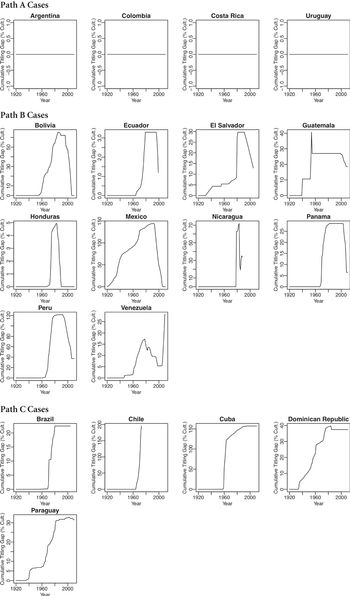

This section proceeds in several steps. I first turn to distinguishing between an absence of property rights, partial property rights, and complete property rights. I also explain why, for this period in Latin America, focusing on a partial property rights gap is more relevant than a complete property gap. Next, I detail the construction of the partial and complete property rights gap variables (annual and cumulative) and the constituent component variables that comprise these property rights gap measures: land redistribution and land titling. The latter variable, land titling, captures not only the formalization of property rights but also the set of rights that titles endow their owners. Along the way, I provide a summary and overview of the data as well as a classification of where each country in Latin America fits into the three canonical paths of property rights gaps.

Coding Degrees of Property Rights over Redistributed Land

Consider first an absence of property rights. Land that is distributed but not titled is coded as not having either partial or full property rights. The same is true of titles that are not recognized or legally defensible. One example would be titles that are not linked to any property registry or cadaster. I also code land with titles that do not allow individuals or collectives to rent, lease, sell, or mortgage their lands under any circumstances as having an absence of property rights.

Next consider partial property rights. Partial property rights entail a formal land title from the state that endows recipients with specified rights. But these titles are often imperfect or incomplete. Property may not be entirely alienable, and instead face consequential restrictions on the ability to sell, lease, partition, or mortgage property. For instance, land sales may be prohibited for a certain period of time within receiving the land or until recipients pay a specified amount for the land. Alternatively, property may be alienable but the lack of an orderly property registry or land cadaster makes it difficult in practice to defend land claims or use land as collateral. For instance, a land cadaster may not exist and property registries may be outdated or decentralized, giving rise to a panoply of overlapping land claims.

Finally, consider complete property rights. Land titles are formal and property is alienable in this case. Property is registered by the state. Property delimitations are generally clear and land titles rarely overlap. These latter stipulations are typically achieved by cadastral mapping, and often by linking cadasters with property registries.

Partial property rights over distributed land are much more common historically in Latin America and elsewhere than complete property rights over land. This is in part due to decentralized and disorderly land registers (for instance, registers that are partially overlapping, outdated, or incomplete) and land cadasters that failed to clearly and consistently delimit property in coordination with registers. And it is in part due to the wide range of restrictions to property rights for land reform beneficiaries.Footnote 15 Partial property rights provide some degree of independence from the state – though hardly complete independence – to beneficiaries. Given these considerations, I construct separate variables that capture the property rights gap between distributed land and at least partial property rights (i.e., partial or complete rights) over that land, and the property rights gap between distributed land and complete property rights over that land.

Constructing an Annual Property Rights Gap Measure

I create two principal variables, one annual and one cumulative, that capture the property rights gap using data on partial and complete property rights. Both of these variables focus on the establishment of property rights over land that the state has redistributed. The first variable is the Yearly Titling Gap. This is a “flow” variable that captures the annual difference between the amount of land redistributed and the amount of land over which partial or, separately, complete property rights are established.

The constituent components used to construct the annual property rights gap variable, as well as the cumulative property rights gap variable defined later in the chapter, capture the extent of land redistribution and land titling. These building blocks therefore merit discussion first in order to better understand how the property gap measures are constructed and what they capture.

Land redistribution data are constructed according to the physical area (in hectares) of private landholdings acquired by the state in a given country-year for redistribution to the land-poor. Land redistribution in Latin America, as elsewhere, has often been implemented through land ceilings that set thresholds for the maximum legal size of property holdings, or through the requirement that property serve a “social function” defined by efficient exploitation criteria and the prohibition of certain forms of tenure relations. I code the redistribution of all private land regardless of compensation structure. This encompasses both land redistribution and land negotiation (see Albertus 2015). In most cases, such as Cuba under Castro, Nicaragua under the Sandinistas, and Peru under military rule in the 1970s, redistributed land was expropriated at much less than market value or wholesale confiscated. In other cases, such as Brazil after 1993, market prices were paid to landowners. Both policies have been redistributive in nature, even if to a different degree.

As Chapter 3 outlines, the process of land reform is similar for land redistribution with full compensation and for land redistribution without compensation or with below market compensation. While the latter may entail more coercion to obtain property, both processes are institutionally exacting and require executive, legislative, judicial, bureaucratic, and often military support. And at the end of the day, such reforms require physically dispossessing landowners and often require the organized settlement of new laborers on former landowners’ property.Footnote 16

Land redistribution with full compensation can reduce landowner resistance. But there are still many cases in which large landowners resist such reforms.Footnote 17 This is because landholding can deliver large landowners benefits that extend beyond simply possessing a valuable asset. Historically, large landowners were able to use their position at the pinnacle of rural social relations to manipulate and pressure workers to vote for favorable candidates (thereby delivering favorable policy) and to suppress rural wages (thereby increasing landowners’ income) (Reference MooreMoore 1966; Reference Huber and SaffordHuber and Safford 1995; Reference Rueschemeyer, Stephens and StephensRueschemeyer, Stephens, and Stephens 1992; Reference ZiblattZiblatt 2009). At the same time, the wealthy have often used landholding as a hedge against inflation in unstable economies (Reference EllisEllis 1992). Consequently, land expropriation – even with full compensation – can spur lengthy and costly legal battles and trigger substantial short-term (and in some cases long-term) disruptions to income on the part of landowners.

I do not include the distribution of public lands in the construction of the land redistribution data. This is because the colonization of public lands is guided by a different theoretical logic than the one that will be detailed in Chapter 3. Land colonization does not have strong redistributive implications and does not involve seizing property from large landowners. It therefore faces less resistance from large landowners than the redistribution of private land, and it is administratively and institutionally easier to implement as a result (see Albertus 2015).Footnote 18 Governments may also pursue land colonization to grow the tax base or to populate frontier zones to protect against foreign incursions. Finally, land colonization often requires less direct interaction between the state and beneficiaries and occurs in frontier zones where state power is more peripheral by definition, giving the former fewer opportunities to exert credible leverage over the latter through the underprovision of property rights.Footnote 19

Since countries have different sizes and geographical topographies, and therefore different endowments of land that may be used for agricultural purposes, the land redistribution variable is normalized by total cultivable land to generate comparable cross-country data. Cultivable land area data is taken from the Food and Agriculture Organization (2000). Land redistribution is therefore ultimately measured as the percentage of cultivable land redistributed in a calendar year. Land redistribution ranges from 0 percent to 62.84 percent (the latter corresponding to Nicaragua in 1979). It has a mean of 0.90 percent and a standard deviation of 3.76 percent.

To better illustrate how the land redistribution variable is coded, consider the cases of Mexico and Colombia. In Mexico, the National Agrarian Registry (RAN), housed within the Agrarian Reform Secretariat (SRA) and centered in Mexico City, manages a detailed database called the Padrón e Historial de Núcleos Agrarios on all of Mexico’s over 30,000 land reform communities that received land communally as ejidos dating back to the time of the Mexican Revolution. For each ejido there are data on the date the community received its land grant from the government, its location, land area, the size of the community holding the land, the amount of land dedicated to housing versus personal family plots versus commonly used areas, and other information tied to ejido changes such as whether a community split into two or acquired additional adjacent land.

I used these data to calculate annual figures for the number of hectares of privately held land that were expropriated and granted to land reform petitioners. Because the theoretical focus in this book is on property rights over land that the government grants anew to land reform beneficiaries, I do not include the recognition or confirmation of what were typically indigenous communities that already had de facto, relatively autonomous control of their property. I also exclude the colonization of public lands. Between the revolution and 2010, Mexico’s government redistributed 51 million hectares of land.Footnote 20

Land reform in Colombia, in contrast to Mexico, has long centered on the distribution of vacant national lands (tierras baldías) to settlers (Reference AlbertusAlbertus 2019). However, the Colombian government has also engaged in a series of land redistribution programs dating back to the 1930s. Based in part on Law 74 of 1926, the government began a small parcelization program in the early 1930s to purchase productive estates affected by property or work contract disputes and divide them between the tenants and squatters on the estate (Reference LeGrandLeGrand 1986, 137–141). Land purchases for subsequent parcelization continued in the 1940s in areas with particularly acute land conflicts, albeit at a slower pace, and even into the 1950s during La Violencia, a brutal social upheaval that pit Liberals against Conservatives and left 200,000 people dead.

Data on the extent of land redistributed through these programs on an annual basis are garnered from various sources prior to the establishment of a land reform agency in Colombia, including Reference LeGrandLeGrand (1986) for the early 1930s, annual publications of the Ministry of Industry’s Anuario estadístico covering 1934 until 1940, records of the Banco Agrícola Hipotecario from the early 1940s, Reference MachadoMachado (2009) for the late 1940s, and Reference SánchezSánchez (1991) for the 1950s. This range of sources reflects the institutional instability of land redistribution programs and the lack of a dedicated land reform agency. The administration of the parcelization program changed frequently, from the Ministry of Agriculture in the 1930s to the Ministry of National Economy to the Institute of Parcelization, Colonization, and Forestry, to the Institute of Colonization and Immigration in the mid-1950s and then to the Caja Agraria in 1956. In most years during this period, the government would purchase a small number of relatively large private properties for redistribution, making these data fairly easy to track and verify despite institutional turnover.

The Social Agrarian Reform Act of 1961 (Law 135) established Colombia’s first land reform agency, the Colombian Institute for Agrarian Reform (Incora). Incora mainly dedicated its efforts to the continued colonization of public lands. But it also conducted measured land redistribution. There were two chief modes: land expropriations from the private sector (expropiaciones) and negotiated purchases from the private sector (adquisiciones/compras directas), both dedicated for subsequent redistribution. There were also two other modes of land acquisition that I do not include in my data because they either do not entail direct state action in redistribution or because they do not involve reallocating land from private landowners to the land-poor. The first are donations and grants from private individuals and corporate or legal entities to the government (cesiones). These are in any case very small in number. The second are property reversions to the state (extinción de dominio). These can occur when a landowner does not exploit their land in accordance with the law. Most property reversions occur on formerly public lands that are granted to but then abandoned by settlers or on privately held lands that are abandoned (Reference MachadoMachado 1994, 106). In a small number of cases reversions occur when land is seized from armed groups that are using it illicitly. These lands revert to the national land bank as public lands.

Annual data on land redistribution from the 1960s through the 1990s are from Incora’s records. The government briefly shut down Incora in the early 2000s and restarted the agency as the Colombian Institute of Rural Development (Incoder). Annual data on land redistribution in the 2000s, mainly through the purchase of private properties for subsequent redistribution, are from Incoder. I conducted several episodes of fieldwork with Incoder to better understand the nature of the data that they manage and made data requests accordingly. Colombia’s government redistributed approximately 2.3 million hectares of land from the 1930s, when the parcelization program began, until the end of the 2000s.

What about the broader panorama of land redistribution in Latin America? Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Guatemala, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, and Venezuela all redistributed more than 20 percent of land relative to cultivable land area. Some of these countries, such as Cuba, Bolivia, Nicaragua, and Peru, redistributed considerably more than 20 percent. Argentina, Costa Rica, Ecuador, and Honduras all redistributed less than 10 percent of cultivable land area. Every country implemented some land redistribution. Land redistribution also exhibits considerable temporal variation. Far from being simply a Cold War phenomenon, numerous countries engaged in land redistribution prior to the Cold War (for example, Mexico and Paraguay) and others redistributed land well after the close of the Cold War (for example, Brazil and Venezuela).

The second building block for the property rights gap variables is land titling. Land titling captures the annual percentage of cultivable land, previously or concurrently redistributed only, that is titled with either partial or, separately, complete property rights. For instance, if 5 percent of cultivable land was redistributed, and it is then all titled, land titling would take a value of 5 percent. This variable has a mean of 0.45 percent and a standard deviation of 2.23 percent.

To illustrate how this variable was coded in greater detail, return to the examples of Mexico and Colombia from above. These cases demonstrate the importance of analyzing the legal framework around land redistribution and land titling in order to assess the nature of property rights that land reform beneficiaries hold as well as how those rights fit into the conceptual framework of property rights laid out earlier in the chapter.

Mexico’s 1917 constitution embedded land reform in Article 27. While ejidos were granted communally to villages as a whole, Article 27 initially opened the door to the possibility that subsequent laws could enable splitting up ejido lands and perhaps even alienating them.Footnote 21 But such laws did not transpire in the following decades. To the contrary, the first complete Agrarian Code that was established in 1934 legislated the complete inalienability of ejido lands by proscribing sales and rentals.Footnote 22 Ejido members that did not personally work their plots for two consecutive years would lose their land.Footnote 23 And ejidos were not permitted to use lands as collateral for mortgages.Footnote 24 In addition to these significant limitations to property rights, the vast majority of ejido members also lacked any formal land title certificates.Footnote 25

On top of the fact that many ejido members violated the agrarian code by renting their parcels to other ejido members or hiring help to work their land for personal or economic reasons (Reference MorettMorrett 1992, 81–88), risking land forfeiture per the law, the lack of title contributed to the indefensibility of landholding. Indefensibility was further compounded by the fact that the Agrarian Code authorized various government entities such as the Agrarian Department, the Secretary of Agriculture, and the Agrarian Bank to directly intervene in numerous ejido affairs, including land disputes.Footnote 26

Government control over property rights in the land reform sector became hard-wired into federal policy. Laws regulating ejidos were vested in the federal government and ejidos were registered in the Agrarian National Registry. The lack of property rights in the land reform sector was not reflective of an overall ideological antagonism to property rights in Mexico. Private property was guided by state-level civil codes and registered in state-level property registers and notary archives. At the same time that the government tightened its grip over the land reform sector by hobbling property rights, it simultaneously engaged in efforts to generate a more robust, parallel property rights regime in the private sector by granting some private landowners safeguards against expropriation via certificados de inafectabilidad starting in 1938, shortly after the passage of the Agrarian Code.

Limitations to alienability, formalization, and defensibility hampered property rights in the land reform sector and endured from the time of Mexico’s revolution until the early 1990s. Legislation in the intervening period, such as the 1971 Federal Law of Agrarian Reform, did not change fundamental property rights restrictions. I consequently code zeroes for the land titling variable in Mexico throughout this period.

Mexico began granting secure and complete property rights to ejidos and their members beginning in the 1990s under PROCEDE. This followed from a major 1992 modification of Article 27 of Mexico’s constitution and the passage of the 1992 Agrarian Law to replace the 1971 federal agrarian law. Both laid the legal groundwork for providing former land reform beneficiaries with greater property rights. PROCEDE then offered ejidos formal land registration in an orderly, centralized registry, plot delineation, and separate title to members over house plots, farm plots, and a share in the value of common lands. It allowed ejido lands to be sold within the ejido and leased to members within or outside the ejido. PROCEDE also recognized ejidos as legal bodies able to enter into contracts and joint ventures and allowed for the full privatization of ejido land through a two-thirds vote of the ejido’s General Assembly.

I accessed data from the Agrarian Reform Secretariat on the number and physical land area of ejidos that received formal legal certification through the PROCEDE program on an annual basis in order to construct the land titling variable figures for Mexico beginning in the 1990s. I code the property rights granted through PROCEDE as complete property rights.

The property rights granted to land reform beneficiaries in Colombia contrast sharply with those granted to land reform recipients in Mexico. From the outset of land redistribution in Colombia in the 1930s, the government granted land to individuals rather than collectives. Property delimitations were surveyed and recorded and individuals were given property titles as part of the administrative procedure granting land itself.

Land grants did, however, come with some restrictions. Starting with Law 200 of 1936 and continuing with Law 100 of 1944, Law 135 of 1961, and Law 1 of 1968, recipients of redistributed private lands were required to repay the government for the costs of land acquisition, surveying, and any land improvements that the government made.Footnote 27 Once the payments were completed, typically over a period between 10 and 20 years, land beneficiaries would no longer face encumbrances to the title of their land. There were further property rights restrictions following Law 135 of 1961. For example, land beneficiaries needed to clear land sales and rentals, and in some cases mortgaging, in advance with the land reform agency Incora.Footnote 28 Violations of these stipulations could enable Incora to repurchase the farm from its owner at the appraised value if it chose to do so, though there are few well-documented cases of this occurring. Several of these restrictions were loosened over time, especially following Law 160 of 1994, which dropped many of the circumstantial restrictions on selling or transferring land provided that the land received was smaller than a specified threshold (one “agricultural family unit”). In short, while land reform beneficiaries always had a path to alienate their land if they chose, it was not always a clear, easy, and immediate path.