Background

Multimorbidity, defined as the coexistence of two or more chronic conditions in the same individual (World Health Organization, 2016), is becoming a crucial health issue in primary care. In the past two decades, the prevalence of chronic diseases has doubled, and the proportion of patients with four or more chronic diseases has increased by approximately 300% (Uijen and van de Lisdonk, Reference Uijen and van de Lisdonk2008). However, in contrast, many current health services, models of care, and clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) are usually based on a single disease approach(World Health Organization, 2016), which may not be appropriate for patients with multimorbidity (van Oostrom et al., Reference van Oostrom, Picavet, de Bruin, Stirbu, Korevaar, Schellevis and Baan2014). Caring for patients with multimorbidity requires a reorientation in the health system as they are high utilizers of health care resources (van den Bussche et al., Reference van den Bussche, Schön, Kolonko, Hansen, Wegscheider, Glaeske and Koller2011, van Oostrom et al., Reference van Oostrom, Picavet, de Bruin, Stirbu, Korevaar, Schellevis and Baan2014, Bähler et al., Reference Bähler, Huber, Brüngger and Reich2015). Besides, clinical practice in primary care needs to adapt from the control of specific diseases to more holistic measures such as functional status and quality of life (Wallace et al., Reference Wallace, Salisbury, Guthrie, Lewis, Fahey and Smith2015, Kernick et al., Reference Kernick, Chew-Graham and O’Flynn2017).

Challenges in multimorbidity management in primary care: the ‘interactions’

Evidence suggests that patients with multimorbidity have higher mortality rates (Di Angelantonio et al., Reference Di Angelantonio, Kaptoge, Wormser, Willeit, Butterworth, Bansal, O’Keeffe, Gao, Wood, Burgess, Freitag, Pennells, Peters, Hart, Håheim, Gillum, Nordestgaard, Psaty, Yeap, Knuiman, Nietert, Kauhanen, Salonen, Kuller, Simons, Van der Schouw, Barrett-Connor, Selmer, Crespo, Rodriguez, Verschuren, Salomaa, Svärdsudd, Van der Harst, Björkelund, Wilhelmsen, Wallace, Brenner, Amouyel, Barr, Iso, Onat, Trevisan, D’Agostino, Cooper, Kavousi, Welin, Roussel, Hu, Sato, Davidson, Howard, Leening, Leening, Rosengren, Dörr, Deeg, Kiechl, Stehouwer, Nissinen, Giampaoli, Donfrancesco, Kromhout, Price, Peters, Meade, Casiglia, Lawlor, Gallacher, Nagel, Franco, Assmann, Dagenais, Jukema, Sundström, Woodward, Brunner, Khaw, Wareham, Whitsel, Njølstad, Hedblad, Wassertheil-Smoller, Engström, Rosamond, Selvin, Sattar, Thompson and Danesh2015, Nunes et al., Reference Nunes, Flores, Mielke, Thumé and Facchini2016, Willadsen et al., Reference Willadsen, Siersma, Nicolaisdóttir, Køster-Rasmussen, Jarbøl, Reventlow, Mercer and Olivarius2018) and poorer quality of life (Fortin et al., Reference Fortin, Lapointe, Hudon, Vanasse, Ntetu and Maltais2004, Marengoni et al., Reference Marengoni, Angleman, Melis, Mangialasche, Karp, Garmen, Meinow and Fratiglioni2011, Kanesarajah et al., Reference Kanesarajah, Waller, Whitty and Mishra2018) compared to patients with single diseases. The difficulty occurs because the health services and CPGs usually focus on only a single disease (Kernick et al., Reference Kernick, Chew-Graham and O’Flynn2017). The task of following and incorporating multiple disease-specific guidelines is one of the key complexities of management, potentially leading to inappropriate, burdensome treatment plans. The complexity in incorporating many disease treatment guidelines can be referred to as ‘interaction’. Usually mentioned in terms of interactions between multiple medications (drugs), interactions can more broadly be categorized into three major groups: disease-disease, disease-treatment, and treatment-treatment (Muth et al., Reference Muth, Kirchner, van den Akker, Scherer and Glasziou2014a; Reference Muth, van den Akker, Blom, Mallen, Rochon, Schellevis, Becker, Beyer, Gensichen, Kirchner, Perera, Prados-Torres, Scherer, Thiem, van den Bussche and Glasziou2014b). The word treatment is used instead of the drug to include non-pharmacological treatment, such as exercise and dietary management. A recent study trying to identify disease-treatment and treatment-treatment serious interactions from 12 different National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) CPGs with three index conditions (type 2 diabetes, heart failure, and depression) identified 48 possible serious disease-treatment interactions and 333 potential drug-drug interactions (Dumbreck et al., Reference Dumbreck, Flynn, Nairn, Wilson, Treweek, Mercer, Alderson, Thompson, Payne and Guthrie2015). The details of the three types of potential interactions between diseases and treatments are highlighted below.

Disease-disease interaction

Diseases can interact in many ways. Having multiple diseases could result in difficulty in evaluating symptoms interfering with the typical clinical presentation or laboratory interpretation, complicating the differential diagnosis. More than one disease can contribute to one non-specific symptom or health event. This is well illustrated in older adults, especially in the frail population. Geriatric syndromes, a group of clinical signs or symptoms, occur from multiple etiologies and pathologies, which lead to difficulty in diagnosis and treatment (Mitty, Reference Mitty2010). Also, one disease can be a precipitating or a predisposing factor to another, or disease pathology can be shared, which might worsen the patient’s condition. This is usually found in diseases involving cardiovascular risks, such as diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and cardiovascular events. Thus, the progression of one disease can accelerate other diseases’ progression or lead to other conditions (Prados-Torres et al., Reference Prados-Torres, Poblador-Plou, Calderón-Larrañaga, Gimeno-Feliu, González-Rubio, Poncel-Falcó, Sicras-Mainar and Alcalá-Nalvaiz2012). Also, disease-disease interaction is not only found between physical health problems. Interaction with mental health disorders has been frequently reported (Cohen, Reference Cohen2017). For example, cardiovascular diseases may trigger, or mechanisms of disease progression may also contribute to mental disorders. On the other hand, stress and depression can trigger disease exacerbation or contribute to disease development (Stein et al., Reference Stein, Benjet, Gureje, Lund, Scott, Poznyak and van Ommeren2019). A study extracting data from a medical database in Scotland found more than one-third of people with multimorbidity have at least one mental health issue (Barnett et al., Reference Barnett, Mercer, Norbury, Watt, Wyke and Guthrie2012).

Disease-treatment interaction

More diseases lead to more prescriptions and an increased risk of interactions with treatment. Drugs recommended for one condition could be contraindicated in another or should be avoided, and treatment might mask or alter the sign of some conditions. For example, in a patient with hypertension and diabetes, the beta-blocker prescribed for the treatment of hypertension may mask the initial sign of hypoglycemic symptoms. Some disease-treatment interactions could worsen a patient’s condition, such as sedative/hypnotic/anticholinergic drugs for the cognitively impaired patient. Other disease-treatment interactions may cause new symptoms from an adverse drug event. Unawareness of the possible side effects and interactions from prescribed medication, physicians may prescribe more medication for these symptoms. This is called a prescription cascade (Rochon and Gurwitz, Reference Rochon and Gurwitz2017), which is the process of prescribing a new medication to treat a side effect from another medication, which does not provide a true benefit to the patient.

Moreover, non-pharmacological treatment options for one disease, such as exercise or dietary control, must also be carefully considered when dealing with multimorbidities. For example, exercise and physical activity is an important component in controlling most chronic conditions (de Souto Barreto, Reference De Souto Barreto2017); however, it should be prescribed to patients based on their overall conditions. Options for patients with poorly controlled diabetes with osteoarthritis of the knee or chronic lung conditions should be different from the patient with well-controlled diseases with no physical limitations.

There is also some evidence of positive interactions between disease-treatment, which can be classified as a synergistic treatment effect (Muth et al., Reference Muth, Kirchner, van den Akker, Scherer and Glasziou2014a). For example, some medications could be used appropriately or effectively for treating more than one condition, such as alpha-blockers for controlling symptoms of benign prostatic hypertension and treating high blood pressure. On the other hand, some medications are not recommended for both conditions, such as some NSAIDs in a patient with chronic kidney disease and heart disease.

Treatment-treatment interaction

Multiple medications, sometimes referred to as polypharmacy, can increase the chance of drug-drug interaction (Marengoni and Onder, Reference Marengoni and Onder2015, Molokhia and Majeed, Reference Molokhia and Majeed2017). Potentially serious interactions between drugs recommended by clinical guidelines are common (Dumbreck et al., Reference Dumbreck, Flynn, Nairn, Wilson, Treweek, Mercer, Alderson, Thompson, Payne and Guthrie2015). This can change the therapeutic effects of the medication or can cause adverse effects and lead to undesirable outcomes. Moreover, complex regimens – multiple dosing and time – could reduce medication adherence (Ingersoll and Cohen, Reference Ingersoll and Cohen2008). Some non-pharmacologic treatments can interrupt compliance to medication prescription. For example, in end-stage kidney disease, patients have to restrict their fluid intake while they usually have several medications to take orally with water for the comorbid conditions. Another example is a lifestyle modification prescription for a frail older adult patient who has malnutrition with uncontrolled diabetes and dyslipidemia. It is important to improve his/her nutrition by increasing caloric intake. However, if he/she is too strict to the specific disease guidelines for those two latter conditions improving their nutrition is nearly impossible. Therefore, the doctor should balance the treatment plan, maximizing benefit from existing treatments and stopping the treatments with limited benefits (Kernick et al., Reference Kernick, Chew-Graham and O’Flynn2017).

Given the complexities of the three types of interactions in multimorbidity management described above, the narrative review sought to explore evidence on how to advance multimorbidity management, with a focus on primary care where a large number of patients with multimorbidity are managed and are considered to be the gatekeepers in many health systems (Cassell et al., Reference Cassell, Edwards, Harshfield, Rhodes, Brimicombe, Payne and Griffin2018).

Methods

Search strategy

We conducted a narrative review (Ferrari, Reference Ferrari2015) of the literature using four major electronic databases consisting of PubMed, Cochrane, World Health Organization database, and Google scholar using variations of the following keyword search and MeSH terms

Search terms:

-

1. (multimorbid*) AND (Primary care) + filter: human, English

-

2. (multimorbid* OR (multiple chronic diseases)) AND (Primary care) AND (Guide* OR recommend*) + filter: human, English

-

3. (multimorbid* OR (multiple diseases)) AND (multidisciplinary* OR interprofessional*) AND (primary care) + filters: human, English

-

4. (multimorbid* OR (multiple diseases)) AND (family OR career OR (caregiver)) AND (primary care) + filters: human, English

-

5. (multimorbid* OR (multiple diseases)) AND (community OR public OR social) AND (primary care) + filters: human, English

Article selection and data synthesis

Only articles published in English were reviewed. In the first round of reviews, priority was given to review papers (including systematic reviews, narrative reviews, and reports) summarizing the current issues and challenges in the management of multimorbidity. Thematic analysis using an inductive approach was used to build a framework on how to advance management (Castleberry and Nolen, Reference Castleberry and Nolen2018). This was done by creating key themes and subthemes based on the information gathered from the first round of reviews. The second round of reviews focused on original articles providing evidence within the primary care context (Figure 1). There were no exclusion criteria on the type of study design used. We included intervention studies, epidemiological studies, and implementation studies. The reference lists of all review articles were searched for additional studies. The evidence found from the second round of review based on the original articles was also used to reiterate the proposed framework obtained from the thematic analysis of review papers. A summary of the 32 original articles used as evidence to support the framework proposed in the review is included in Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Table 2.

Figure 1. Flow diagram of articles

Articles were screened and reviewed by four authors; all are practicing family physicians with experience in multimorbidity management. Each article is screened by at least two reviewers. If there is a discrepancy, it was resolved by consensus in consultation with the senior author, who is a family physician with postgraduate training in population health and over ten years of experience in public health. The thematic analysis was led by two co-authors with experience in qualitative research.

Results

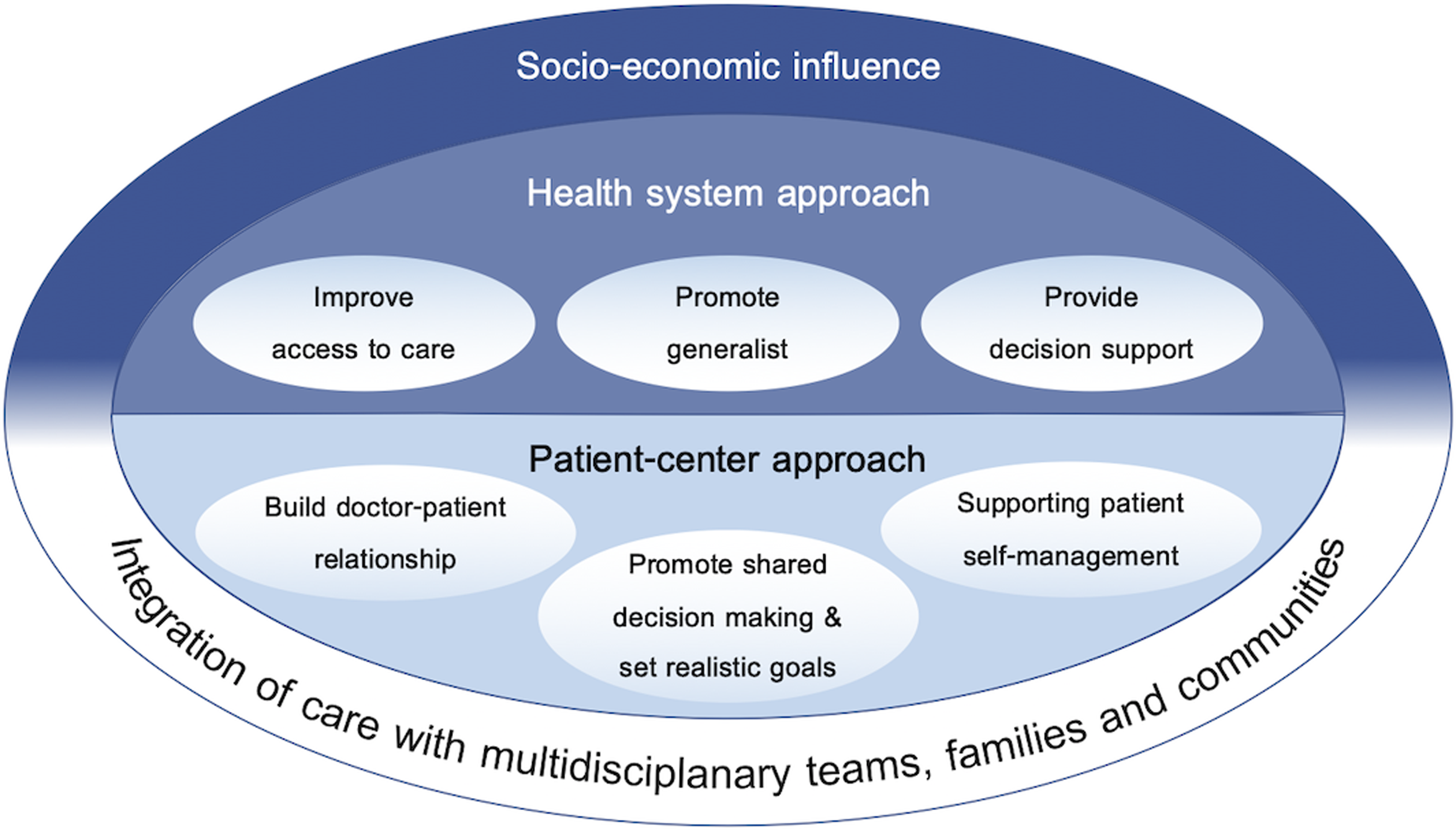

Based on our searches, evidence suggests that advancing multimorbidity management in primary care requires both a health system-based approach to reorientate health services and a more patient-centered approached for providers to support the complexities of care for patients with multimorbidity is needed (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Framework for advancing multimorbidity management in primary care

Advancing multimorbidity management through health system-based approach

It is important to note that improving the health system for better patient care and care delivery may not cover all aspects of multimorbidity management. Many populations are at higher risk and are more vulnerable to the impacts of multimorbidities, such as those with lower socioeconomic status (Barnett et al., Reference Barnett, Mercer, Norbury, Watt, Wyke and Guthrie2012, Pathirana and Jackson, Reference Pathirana and Jackson2018, Andrew Wister et al., Reference Andrew Wister, Shashank, Byron Walker and Schuurman2020), underlying the need to address the social determinants of health. Nevertheless, to advance multimorbidity management in primary care, the literature suggests three major areas that need to be addressed: i) improve access to care, ii) promote generalism, and iii) provide a decision support system. Addressing these three areas should help reduce the fragments of services and responsibility and drive the medical system to provide accountable, accessible, comprehensive, and coordinated care for those with multimorbidity.

Improve access to care

Multimorbid patients require more medical attention resulting in a higher rate of health care contact compared to the non-multimorbid population (Bähler et al., Reference Bähler, Huber, Brüngger and Reich2015). Some patients are unable to maintain regular health care visits due to barriers in access to care (Moffat and Mercer, Reference Moffat and Mercer2015, Wallace et al., Reference Wallace, Salisbury, Guthrie, Lewis, Fahey and Smith2015). Evidence identified two major barriers in accessing health care in multimorbid patients: i) the ability to pay and ii) the ability to reach necessary health services (World Health Organization, 2016, Foo et al., Reference Foo, Sundram and Legido-Quigley2020)

The ‘ability to pay’ can be dealt with by providing access to universal health coverage. Appropriated universal health coverage has been shown to improve access to care and improve health outcomes (World Health Organization, 2013). The World Health Organization also suggests universal health coverage as one of the important steps toward improving care in multimorbidity (World Health Organization, 2016). This can be done briefly by giving a high priority to achieving full population coverage of an affordable package of services through publicly governed, mandatory financing mechanisms and sustained political commitment from the highest level of government (David Nicholson et al., Reference David Nicholson, Warburton and Fontana2015).

The ‘ability to reach’ can potentially be dealt with by allocating primary care sites closer to the community (Glass et al., Reference Glass, Kanter, Jacobsen and Minardi2017). While evidence specifically assessing the multimorbid population and access to primary care is lacking, existing evidence suggests that better access to primary care has proven successful in improving health outcomes for many different conditions (Kravet et al., Reference Kravet, Shore, Miller, Green, Kolodner and Wright2008, Bynum et al., Reference Bynum, Andrews, Sharp, McCollough and Wennberg2011, Shi, Reference Shi2012). Also, improving geographical reach alone may not be able to handle the complex needs of multimorbid patients. Necessary health services must also be presented at the working sites. A potential way to improve reach to necessary health services is to provide a policy that emphasizes health resource allocation and systems for consultation and referrals (Hsieh et al., Reference Hsieh, Gu, Shin, Kao, Lin and Chiu2015). In addition, due to the COVID pandemic, telemedicine and telehealth have been used to help improve access to care (North, Reference North2020, Sinsky, Reference Sinsky2020). While a conceptual model for telehealth and chronic disease management has been proposed (Salisbury et al., Reference Salisbury, Thomas, Cathain, Rogers, Pope, Yardley, Hollinghurst, Fahey, Lewis, Large, Edwards, Rowsell, Segar, Brownsell and Montgomery2015), limited evidence has been published on specifically assessing its impact on the multimorbid population. A quasi-experimental study from Spain suggested that the use of telemedicine in primary care can help improve health outcomes, such as better disease control and reduce emergency hospitalization among those with chronic conditions (Orozco-Beltran et al., Reference Orozco-Beltran, Sánchez-Molla, Sanchez and Mira2017). A recent review has summarized that while the telehealth approach has been proven successful for the management of common chronic diseases, there is high heterogeneity in the technology use, and further clinical studies are needed to provide robust evidence on clinical efficacy and safety (Omboni et al., Reference Omboni, Campolo and Panzeri2020).

Promote generalism

The complexity of multimorbidity often requires some degree of coordination between different specialists and often leads to fragmentation and disruption of care (Moffat and Mercer, Reference Moffat and Mercer2015, Wallace et al., Reference Wallace, Salisbury, Guthrie, Lewis, Fahey and Smith2015). Fragmented care results in poorer care quality, poor resource utilization, and a higher hospitalization rate of ambulatory care sensitive conditions – conditions that, ideally, primary care should be able to prevent (Frandsen et al., Reference Frandsen, Joynt, Rebitzer and Jha2015). Impacts of disruption of care include poorer clinical outcomes, such as increased hospitalizations and mortality rates and higher treatment costs.

Generalism is a concept of seeing a person as a whole and providing broad and holistic health care deliveries that are relevant to the patient’s problems (Howe, Reference Howe2012). The concept itself aims to better understand patients’ disease-illness and context, widen the spectrum of care, improve coordination of care, reduce fragmentation of care, and improve continuity of care. Generalism would also reduce care disruption and improve multimorbidity management (May et al., Reference May, Montori and Mair2009, World Health Organization, 2016, Vishal Ahuja and Staats, Reference Vishal Ahuja and Staats2020).

Promoting generalism within the health care system can be done in several ways. Evidence suggests that generalists and family physicians are trained to provide medical care comprehensively and holistically (World Health Organization, 2016), which is a key component in promoting generalism (2011). Also, training health workers to provide comprehensive medical services with nurse managers or care managers (Suriyawongpaisal et al., Reference Suriyawongpaisal, Aekplakorn, Leerapan, Lakha, Srithamrongsawat and von Bormann2019) while adjusting the health delivery system to promote task sharing and task shifting between providers in primary care could help improve the continuity of care while reducing fragmentation and disruption of care among patients with multimorbidity.

Provide decision support

CPG is one form of decision support that guides patient care. However, the methodology for developing CPGs is usually based on evidence or research studies that focus on specific diseases (Tinetti et al., Reference Tinetti, Bogardus, Joseph and Agostini2004, World Health Organization, 2016). This causes concern about how CPGs should be applied to patients with multiple comorbidities. A couple of studies that tried applying CPGs in hypothetical multimorbid patients resulted in an excessive number of drugs and lifestyle modifying prescriptions. Such practice could cause a burden to the patients and introduce risks of unexpected adverse health effects from drug interactions, resulting in the patient’s poor treatment adherence and poor treatment outcomes. (Boyd et al., Reference Boyd, Darer, Boult, Fried, Boult and Wu2005, Okeowo et al., Reference Okeowo, Patterson, Boyd, Reeve, Gnjidic and Todd2018). The evidence points out a need to create CPGs for patients with multiple comorbidities. A framework for the development of CPGs that consider multimorbidity has been developed (Uhlig et al., Reference Uhlig, Leff, Kent, Dy, Brunnhuber, Burgers, Greenfield, Guyatt, High, Leipzig, Mulrow, Schmader, Schunemann, Walter, Woodcock and Boyd2014), but CPGs regarding how to provide particular treatments given a particular set of multiple comorbidities are still limited (World Health Organization, 2016). From our review, to date, BMJ Best Practice is one of the few sources for CPGs that incorporate the concept of multimorbid (BMJ Best Practice). However, the online guideline tools, first launched in September 2020, are still limited to common acute conditions such as COVID-19 and acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and require an access fee.

Since the early 2000, with the advancement in computer technology, CPGs have been formatted as computer-interactable guidelines (CIGs). This enables the development of CIG-driven clinical decision support systems (CDSSs). Many CIG-based CDSSs have been developed to detect interactions between CIGs to support physician’s care delivery. However, there is still a huge gap until they are applicable in an actual clinical setting as they are not easily adaptable, generalizable, or re-usable in their current state and still have many limitations in real-life situations (Bilici et al., Reference Bilici, Despotou and Arvanitis2018).

Many CDSSs have been developed to detect potential adverse drug reactions in a patient with multiple drug prescriptions from the electronic medical record (EMR). A study regarding the effectiveness of EMR-enabled CDSSs in specifically multimorbid populations is lacking. EMR-enabled CDSSs were proven to be most effective in reducing potentially inappropriate medications in the hospital setting, less effective in an ambulatory care setting, and borderline effective in residential aged care facilities (Scott et al., Reference Scott, Pillans, Barras and Morris2018). The population in the studies is not limited to the multimorbid patient but mostly are elderly with a high prevalence of multimorbidity. The results might be applicable to the multimorbid population.

Advancing multimorbidity management through a patient-centered approach

In addition to advancing health systems factors to promote multimorbidity management, for providers directly involved in patient care, evidence suggests that the core principles of patient-centered medicine (PCM) (Muth et al., Reference Muth, van den Akker, Blom, Mallen, Rochon, Schellevis, Becker, Beyer, Gensichen, Kirchner, Perera, Prados-Torres, Scherer, Thiem, van den Bussche and Glasziou2014b, Wallace et al., Reference Wallace, Salisbury, Guthrie, Lewis, Fahey and Smith2015) and the chronic care model (CCM) (Boehmer et al., Reference Boehmer, Abu Dabrh, Gionfriddo, Erwin and Montori2018) are crucial towards advancing care for a patient with multimorbidity. The following PCM and CCM components should be embedded in multimorbidity management in primary care

Building and maintaining a good doctor-patient relationship as a partnership

Primary care providers usually prioritize having a doctor-patient relationship as an important factor in successful treatment outcomes (Damarell et al., Reference Damarell, Morgan and Tieman2020). A good partnership and trust will help towards agreement or the willingness of patients to follow the care plan and increase the chance of better health outcomes (McGilton et al., Reference McGilton, Vellani, Yeung, Chishtie, Commisso, Ploeg, Andrew, Ayala, Gray, Morgan, Chow, Parrott, Stephens, Hale, Keatings, Walker, Wodchis, Dubé, McElhaney and Puts2018)

To build and maintain a good doctor-patient relationship, the primary care provider needs to understand the patient as a whole person (psychological, social, and spiritual aspects). The ability to provide for a patient over a long period of time is beneficial for knowing the history of patients’ diseases and illness experience, the life context of a career, specific life circumstances, and spiritual aspects (Damarell et al., Reference Damarell, Morgan and Tieman2020). Asking and listening to patient/family concerns not only show that the provider care for the patient and build a partnership (Poitras et al., Reference Poitras, Maltais, Bestard-Denommé, Stewart and Fortin2018) but also could provide insights into an aspect of the patient’s personal and social circumstance which might impact the therapeutic acceptance and success (Damarell et al., Reference Damarell, Morgan and Tieman2020). Knowing patients’ resources and limitations assists the provider to create an individualized care plan for each patient’s unique circumstances and illness experience (Bogner and de Vries, Reference Bogner and de Vries2008, Poitras et al., Reference Poitras, Maltais, Bestard-Denommé, Stewart and Fortin2018) which is essential for patients with multimorbidity (Bogner and de Vries, Reference Bogner and de Vries2008, McGilton et al., Reference McGilton, Vellani, Yeung, Chishtie, Commisso, Ploeg, Andrew, Ayala, Gray, Morgan, Chow, Parrott, Stephens, Hale, Keatings, Walker, Wodchis, Dubé, McElhaney and Puts2018).

Prioritization of health problems, promoting shared decision-making, and setting realistic goals

Based on the potential interactions and disease trajectories, prioritization of health problems in a patient with multimorbidity needs to take into account the patient’s concerns, values, goals, and preferences along with the multiple clinical and disease-specific interactions and risk factors. To help understand and prioritize these complex issues and problems that patients with multimorbid may have, simple questions such as ‘What is bothering you most?’ or ‘What would you like to focus on today?’ may be used to help elicit first responses (Damarell et al., Reference Damarell, Morgan and Tieman2020).

Involving patients in the decision-making process results in better outcomes such as increased patient satisfaction, better adherence to treatment regimens, improved functional status, and optimized self-management (McGilton et al., Reference McGilton, Vellani, Yeung, Chishtie, Commisso, Ploeg, Andrew, Ayala, Gray, Morgan, Chow, Parrott, Stephens, Hale, Keatings, Walker, Wodchis, Dubé, McElhaney and Puts2018; Rijken et al., Reference Rijken, Struckmann, van der Heide, Hujala, Barbabella, van Ginneken, Schellevis, Richardson and van Ginneken2017). With multimorbidity problems, a longer consultation time is needed. Thus, using available shared decision-making tools may help support the process (Damarell et al., Reference Damarell, Morgan and Tieman2020). An example of such a decision-making tool is the three-step talk: step 1) ‘choice talk’, making sure that patients know that reasonable options are available, step 2) ‘option talk’, providing more detailed information about options, and step 3) ‘decision talk’, supporting the work of considering preferences and deciding what is best and effective in primary care (Wallace et al., Reference Wallace, Salisbury, Guthrie, Lewis, Fahey and Smith2015).

A thorough interaction assessment of the patient’s conditions, treatments, consultation, and context can lead to multiple treatment goals, which may include targeting symptoms, functional ability, quality of life, desired patient outcomes, etc. (Palmer et al., Reference Palmer, Marengoni, Forjaz, Jureviciene, Laatikainen, Mammarella, Muth, Navickas, Prados-Torres, Rijken, Rothe, Souchet, Valderas, Vontetsianos, Zaletel and Onder2018). For individualized care planning, the provider should find agreement with the patient and/or family members (with the patient’s permission for members to be involved) on the responsibility for coordination of care, agreement of goal and timing of follow-up, and how to access urgent care and arrangement for more frequent follow-up as needed especially for those with complex disease management (Kernick et al., Reference Kernick, Chew-Graham and O’Flynn2017). Furthermore, in each follow-up consultation, the individualized care plans should be reviewed and modified at each reassessment (Palmer et al., Reference Palmer, Marengoni, Forjaz, Jureviciene, Laatikainen, Mammarella, Muth, Navickas, Prados-Torres, Rijken, Rothe, Souchet, Valderas, Vontetsianos, Zaletel and Onder2018).

Supporting patient self-management

For a patient with multimorbidity, promoting self-management is a key factor because patients often have numerous conditions to monitor simultaneously, many of which affect the other comorbidities. Also, the intervention of care and treatment usually requires lifestyle changes. Therefore, active involvement of the patient is crucial to achieving expected health outcomes (Palmer et al., Reference Palmer, Marengoni, Forjaz, Jureviciene, Laatikainen, Mammarella, Muth, Navickas, Prados-Torres, Rijken, Rothe, Souchet, Valderas, Vontetsianos, Zaletel and Onder2018, Poitras et al., Reference Poitras, Maltais, Bestard-Denommé, Stewart and Fortin2018). Several key success factors that can promote self-management include using the participatory approach, understanding the patient’s situation, enhancing the patient’s motivation, reinforcing adherence, providing educational resources and skills, and developing peer support through group meetings (Poitras et al., Reference Poitras, Maltais, Bestard-Denommé, Stewart and Fortin2018). The evidence shows that self-management education programs can help patients with single chronic diseases as well as those with multimorbidity (Lynch et al., Reference Lynch, Liebman, Ventrelle, Avery and Richardson2014). Additional patient self-management support materials should be provided, such as CDs, videos, booklet, or other written material, and self-monitoring devices appropriate to their condition (Katon et al., Reference Katon, Lin, Von Korff, Ciechanowski, Ludman, Young, Peterson, Rutter, McGregor and McCulloch2010, Mercer et al., Reference Mercer, Fitzpatrick, Guthrie, Fenwick, Grieve, Lawson, Boyer, McConnachie, Lloyd, O’Brien, Watt and Wyke2016, Angkurawaranon et al., Reference Angkurawaranon, Papachristou Nadal, Mallinson, Pinyopornpanish, Quansri, Rerkasem, Srivanichakorn, Techakehakij, Wichit, Pateekhum, Hashmi, Hanson, Khunti and Kinra2020). For example, the CARE Plus intervention, which is a whole-system primary area-based complex intervention, provided mindfulness-based stress management CDs and a cognitive-behavioral therapy-derived self-help booklet about the intervention (Mercer et al., Reference Mercer, Fitzpatrick, Guthrie, Fenwick, Grieve, Lawson, Boyer, McConnachie, Lloyd, O’Brien, Watt and Wyke2016). In a self-monitoring program for a patient with depression and diabetes or coronary heart disease, patients received blood pressure or blood glucose meters (Katon et al., Reference Katon, Lin, Von Korff, Ciechanowski, Ludman, Young, Peterson, Rutter, McGregor and McCulloch2010).

Integration of care with multidisciplinary teams, families, and communities

Integration is a group of methods and models designed to promote connectivity and reduce boundaries between ‘cure’ and ‘care’ sectors (Kodner, Reference Kodner2002). Integrated care is likely needed to improve quality of care and quality of life, especially in people with complex care needs (Leutz, Reference Leutz1999). It is defined as the search to connect the health care system with another human service (Leutz, Reference Leutz1999). For patients with multimorbidity, integration with a multidisciplinary team and their family/community is essential to advance multimorbidity management

Multidisciplinary working is the cooperation across service providers by conjugating knowledge, skills, and best practice to explore extraordinary problems and reach the best solution for patients with complex care needs (Susan Swientozielskyj et al., Reference Susan Swientozielskyj, Palmer, Palmer, Kohn, Daniel, Carey, Sevak, Nightingale, Kenwood, Westwood, Stamp, Blower, Murgatroyd, Baggaley, Bryant, Cooper and Nwosu2014). To care for patients with multimorbidity, a collaboration between physicians, nurse case managers can play an essential role in the area of providing a central and continuous point of contact, as well as promoting patient’s self-health management (eg, person-centered assessment, assisting the patient to set the goal of care, enhancing patient and caregiver education, delivering preventive care, monitoring patient’s status, together with providing patient’s partnership) (Sommers et al., Reference Sommers, Marton, Barbaccia and Randolph2000, Hogg et al., Reference Hogg, Lemelin, Moroz, Soto and Russell2008, Katon et al., Reference Katon, Lin, Von Korff, Ciechanowski, Ludman, Young, Peterson, Rutter, McGregor and McCulloch2010, Boult et al., Reference Boult, Reider, Leff, Frick, Boyd, Wolff, Frey, Karm, Wegener, Mroz and Scharfstein2011). Examples of successful programs include the participation of psychiatrists to help provide psychological support, pharmacological treatment, and mental monitoring for mental health support (Barley et al., Reference Barley, Walters, Haddad, Phillips, Achilla, McCrone, Van Marwijk, Mann and Tylee2014), having a nurse or social worker as a case manager to evaluate the patient in the home (Sommers et al., Reference Sommers, Marton, Barbaccia and Randolph2000). Several studies have shown that the collaboration of pharmacists in the role of medication reviewer and assisted care plan manager in the primary care team benefits the outcomes of disease control, preventive care, and medication safety (Krska et al., Reference Krska, Cromarty, Arris, Jamieson, Hansford, Duffus, Downie and Seymour2001, Hogg et al., Reference Hogg, Lemelin, Dahrouge, Liddy, Armstrong, Legault, Dalziel and Zhang2009, Howard-Thompson et al., Reference Howard-Thompson, Farland, Byrd, Airee, Thomas, Campbell, Cassidy, Morgan and Suda2013, Köberlein-Neu et al., Reference Köberlein-Neu, Mennemann, Hamacher, Waltering, Jaehde, Schaffert and Rose2016). Moreover, co-working with health educators, dietitians, home-care specialists, and social workers has also shown to be an effective disease control strategy in patients with multiple chronic conditions (Bogner and de Vries, Reference Bogner and de Vries2008, Lynch et al., Reference Lynch, Liebman, Ventrelle, Avery and Richardson2014, Köberlein-Neu et al., Reference Köberlein-Neu, Mennemann, Hamacher, Waltering, Jaehde, Schaffert and Rose2016).

Families and communities of patients may also need to be involved to reach the best health care (World Health Organization, 2016). Family support is one of the essential resources for a patient with multimorbidity. Family members or caregivers help navigate the health care system to obtain services (Zulman et al., Reference Zulman, Jenchura, Cohen, Lewis, Houston and Asch2015). A qualitative study revealed that family caregivers can fill the gaps in the fragmented medical system. They play multiple roles, including coordinating care across transitions, accessing and coordinating medical care services, communicating with physicians and services, and providing information regarding patients’ medical history (Levine et al., Reference Levine, Reinhard, Feinberg, Albert and Heart2003–2004, Bookman, Reference Bookman2007). Family caregivers can also assist in motivating patients to make behavioral changes (Naganathan et al., Reference Naganathan, Gill, Jaakkimainen, Upshur and Wodchis2016) and share in medical decision-making (Kernick et al., Reference Kernick, Chew-Graham and O’Flynn2017).

Community-based integrated care is the combined terms of community-based care and integrated care. Community-based care is a health system that is designed and driven by community health needs, beliefs, and values which promotes engagement and compliance of communities that are driven by their system. Since integrated care mainly focuses on the reduction of fragmentation in health care delivery, community-based integrated care provides an outlook on the way the various rationalization strategies could be combined by taking the reduction of fragmentation in health care delivery and a consistent focus on the health of the community as the starting point (Plochg and Klazinga, Reference Plochg and Klazinga2002). Older adults with multimorbidity may face disability, functional impairment, and chronic disease burden. Access to care is now challenged by environmental factors and social determinants of health. For example, the Richmond Health and Wellness Program is a collaboration of health professionals from schools of nursing, pharmacy, medicine, social work, allied health, and psychology which was initiated to develop the strategy to reduce barriers to access to care. This community-based partnership was contributed by the cocreation of the program with residents, students, providers, community agencies, and institutional leaders. By having support in shaping policy, securing grants, and offsetting negative social determinants of health, these partnerships bring positive outcomes (Parsons et al., Reference Parsons, Slattum and Bleich2019).

Based on the framework and evidence mentioned in this review, a simple checklist has been made to help summarize the key assessments that should help primary care providers manage patients with multimorbidity. (Table 1 Simple Multimorbidity Assessment Checklist for Primary Care – SMAC)

Table 1. Simple Multimorbidity Assessment Checklist for primary care

Discussion

The review found that the literature on the implementation of programs for advancing multimorbidity management within primary care is still relatively scarce and is mostly from developed countries (Wallace et al., Reference Wallace, Salisbury, Guthrie, Lewis, Fahey and Smith2015, Rijken et al., Reference Rijken, Hujala, van Ginneken, Melchiorre, Groenewegen and Schellevis2018). As evident in the review process and this review, many published literature (Harris et al., Reference Harris, Dennis and Pillay2013; Wallace et al., Reference Wallace, Salisbury, Guthrie, Lewis, Fahey and Smith2015; Rijken et al., Reference Rijken, Hujala, van Ginneken, Melchiorre, Groenewegen and Schellevis2018) and agencies, such as the European Union (Rijken et al., Reference Rijken, Struckmann, van der Heide, Hujala, Barbabella, van Ginneken, Schellevis, Richardson and van Ginneken2017) and NICE (Kernick et al., Reference Kernick, Chew-Graham and O’Flynn2017), have published guidelines on multimorbidity management. While many aspects between the reports and our review may overlap, the scope of this narrative review was to provide a framework and evidence on how to advance multimorbidity management with a particular focus on primary care, thus integrating multimorbidity management guidelines with concepts of PCM and the CCM. This simple integration provides an overarching framework for advancing the health care system by connecting to the processes of individualized care plans and integration of care with other providers, family members, and the community (Figure 2).

It is also important to note that multiple issues and difficulties come with implementing frameworks to advance multimorbidity management (Damarell et al., Reference Damarell, Morgan and Tieman2020). In Europe, getting all the care packages required for the management of multimorbidity into a basic insurance package has faced difficulties (Rijken et al., Reference Rijken, Struckmann, van der Heide, Hujala, Barbabella, van Ginneken, Schellevis, Richardson and van Ginneken2017). In Thailand, finding sustainable sources of financing and training primary care teams is a major concern as the sustainability of primary care development relies mainly on partnerships, international financial support, and expertise from overseas (Suriyawongpaisal et al., Reference Suriyawongpaisal, Aekplakorn, Leerapan, Lakha, Srithamrongsawat and von Bormann2019). A lack of computer skills among care professionals and patients, inadequate ICT infrastructure, and inadequate funding for structural implementation and innovation in supportive eHealth tools are also important barriers when implementing electronic decision support systems (Rijken et al., Reference Rijken, Struckmann, van der Heide, Hujala, Barbabella, van Ginneken, Schellevis, Richardson and van Ginneken2017, Dornan et al., Reference Dornan, Pinyopornpanish, Jiraporncharoen, Hashmi, Dejkriengkraikul and Angkurawaranon2019). Traditional norms, values, and work processes can become a barrier to the implementation of patient-centered integrated care due to a lack of managerial vision of patient centeredness in care organizations (Wallace et al., Reference Wallace, Salisbury, Guthrie, Lewis, Fahey and Smith2015; Rijken et al., Reference Rijken, Struckmann, van der Heide, Hujala, Barbabella, van Ginneken, Schellevis, Richardson and van Ginneken2017). For family members and/or caregivers who have a responsibility in caring for patients with multimorbidity, literature has documented that some have trouble with accessing helpful information, assessing the quality of services, understanding what information is necessary to get services, and anticipating what will be needed (Bookman, Reference Bookman2007). As these difficulties are documented, more evidence is needed to share the lessons learned and how to overcome such barriers to advance multimorbidity management in primary care.

With the knowledge of multimorbidity management in primary care in its infancy, especially for developing countries, we proposed a number of pressing research questions cross-cutting these themes in both clinical science and implementation sciences perspectives. These questions include: How can we improve evidence base for management of patients with multimorbidity while incorporating patient perspectives? What role(s) can para-health professionals play in scaling up and scaling out (reach) of management of multimorbidity? What training and education for (para) health professionals are needed to advance multimorbidity care toward a patient-centered approach? What sustainable funding models are needed to deliver improvements in multimorbidity care? How can technology-based platforms be integrated into health systems at scale to support clinical decision-making and long-term management of multiple chronic conditions?

Conclusion

The review provides a framework and evidence to support a framework for advancing multimorbidity management in primary care. Advancing multimorbidity management in primary care requires both a health system approach to help improve the access, delivery, and quality of care as well as a patient-centered approach so that necessary components of PCM and the CCM are incorporated into the management of patients with such complex conditions. Based on the review, a Simple Multimorbidity Assessment Checklist for Primary Care has also been proposed to help guide providers provide management for those with multimorbidity. However, as it has not been validated, future studies on its clinical usefulness are required. Finally, with multimorbidity management in its infancy, especially for most developing countries, we have proposed a number of pressing research questions cross-cutting these themes.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1463423622000238

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Authors’ contributions

ChanA, YC, SK, and CA conceived the project, YC and KP compiled the search strategies. ChanA, YC, WJ, NW, KP, PM and CA conducted the literature review. ChanA, WJ, NW and CA extracted the data. ChanA, YC, WJ, KP, and CA were involved in the initial draft of the manuscript. All authors (ChanA, YC, WJ, NW, KP, PM, SK and CA) critically reviewed and revised the subsequent drafts. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Financial support

The research was partially supported by Chiang Mai University. The funder had no role in the design, execution, analyses, interpretation and decision to publish.

Conflicts of interest

None.