1. Introduction and previous historiography

After independence from Spain, most Latin American republics relied heavily on indirect taxes, such as import duties, as their main source of ordinary public revenue,Footnote 1 and on export duties to a lesser extent (Pérez and Herrera, Reference Pérez and Herrera2013). They were easy to collect and monitor, difficult to evadeFootnote 2 and they did not create major social tensions (Bértola and Ocampo, Reference Bértola and Ocampo2013, p. 132; Biehl and Labarca, Reference Biehl, Labarca, Atria, Groll and Valdés2018, p. 90).Footnote 3 Other forms of taxation were perceived as being «deeply unpopular, difficult to administer, and easy to evade» (Bulmer-Thomas, Reference Bulmer-Thomas2003, p. 32; see also Jáuregui, Reference Jáuregui and Jáuregui2006). They were particularly unpopular with the economic elites, who were reluctant to pay direct taxes to fund anything except military expenses and were especially opposed to much needed education or health programmes (Lewis, Reference Lewis and Bethell1986, p. 297; Lindert, Reference Lindert2010; Santilli, Reference Santilli2010).

According to Coatsworth, Spanish colonists and their descendants typically sought minimal direct taxation, relying instead on indirect taxes that they barely noticed (Coatsworth, Reference Coatsworth2008a).Footnote 4 For the powerful, in the highly unequal Latin American societies, «trade taxes and debt, together with inflation and currency debasement, were cheaper and more sensible options to fund the state», as opposed to direct taxes such as income and/or wealth taxes (see also Irigoin, Reference Irigoin and Jáuregui2006; Biehl and Labarca, Reference Biehl, Labarca, Atria, Groll and Valdés2018, p. 92).Footnote 5 We agree with Sokoloff and Zolt (Reference Sokoloff and Zolt2006, pp. 204-205) that extreme political and economic inequality, which was characteristic of all Latin American countries, was largely responsible for the reluctance of their governments to tax income and wealth directly.Footnote 6 Furthermore, early Latin American policy makers were greatly influenced by the fiscal doctrine of European classical economists who advocated for small states with little central government expenditure, and which therefore needed small revenues (Musgrave and Peacock, Reference Musgrave, Peacock, Musgrave and Peacock1958; Musgrave, Reference Musgrave, Auerbach and Feldstein1985).Footnote 7 These ideas were influential in the region, at least until the 1880s (Musgrave, Reference Musgrave, Auerbach and Feldstein1985). Few public goods were to be provided by the early states, other than defence, administration of basic justice, some transport facilities and limited education (Garavaglia and Ruiz, Reference Garavaglia and Ruiz2013).

It has also been argued that direct taxation was avoided in Latin America because of an absence of proper human capital within the state. There were few well-trained bureaucrats to collect taxes, and a lackFootnote 8 of good quality statistical information on properties and/or people to be taxed (Jáuregui, Reference Jáuregui and Jáuregui2006; Pinto Bernal, Reference Pinto Bernal2012).Footnote 9 In 1881, the Chilean finance minister, José Alfonso, made the crucial point that to collect direct taxes the state needed both well-trained officers to set the exact amount of taxes to be paid by either firms or persons (i.e. a rol de contribuyentes or list of taxpayers), but also an additional cadre of skilled bureaucrats to actually collect such taxes.Footnote 10 This is in line with the idea that «states require accurate information about their subject populations, territories, and economies in order to effectively mobilize revenues» (Vom-Hau et al., Reference Vom-Hau, Peres-Cajías and Soifer2021, p. 1). On account of these shortcomings, the economic history of developing countries «is littered with examples of early attempts to introduce income taxation that subsequently failed because of the lack of fiscal capacity to extract sufficient yields» (Aidt and Jensen, Reference Aidt and Jensen2009, p. 161).

The reluctance of the elites to be taxed (i.e. an ideological or political barrier),Footnote 11 and the poor extractive condition of the new states (i.e. a resource constraint), after independence meant that customs duties on foreign trade became «the back-bone of the new fiscal systems» (Hanson, Reference Hanson1936; Ortega, Reference Ortega2005; Jáuregui, Reference Jáuregui and Jáuregui2006; Sokoloff and Zolt, Reference Sokoloff and Zolt2006; Marichal, Reference Marichal, Bulmer-Thomas, Coatsworth and Cortes-Conde2008, p. 448; see also Coatsworth, Reference Coatsworth, Bulmer-Thomas, Coatsworth and Cortes-Conde2008b; Garavaglia, Reference Garavaglia2010). Apart from custom duties, other important sources of revenues were monopoly receipts (called estancos, mainly from tobacco), papel sellado (official paper) and stamps, transport and communication receipts (e.g. from post offices, railways, telegraphs) and some other minor taxes inherited from the colonial period (Garavaglia, Reference Garavaglia2010; Soifer, Reference Soifer2015). Yet, the impact of other taxes (beyond custom duties), in particular that of direct taxes, on fiscal revenues was limited. In those Latin American countries where direct taxes were implemented, they rarely accounted for more than 1.5-2 per cent of total public revenues during the 1820s-1850s.Footnote 12 Among this latter group were the tithes (diezmo), which can be safely labelled as a direct tax since they taxed agricultural income directly (Jáuregui Reference Jáuregui and Jáuregui2006).Footnote 13 Trade and professional licenses (patentes) were also inherited by the new republics, and can also be taken as direct taxes since they taxed either incomes or profits of some professions and firms (Jáuregui, Reference Jáuregui and Jáuregui2006).Footnote 14 Direct taxation in Latin America's new republics was narrowly focussed and reflected the colonial legacy.

This is not to say, however, that other forms of direct taxation, not inherited from the colonial regimen, were unknown during the first decades after independence (despite resistance from local elites or limited extractive capacity), or that all governments in Latin American republics were as rigid and inefficient as Marichal has suggested.Footnote 15 In Chile in 1817, there was a short-lived example of direct taxation, when a new tax was temporarily imposed upon public servants' wages to fund the independence wars (Agostini and Islas, Reference Agostini, Islas and Jaksić2018). The most important early direct tax, however, was a so-called land tax, the catastro, a tax on agricultural market income, introduced in 1832-4 (Soifer, Reference Soifer2015; Llorca-Jaña et al., Reference Llorca-Jaña, Navarrete-Montalvo and Araya2018), which appeared in the fiscal treasury in 1835. It was complemented by the contribución agrícola in 1853, another land tax, which replaced the tithe (Cattaneo, Reference Cattaneo2013).Footnote 16 These Chilean direct land taxes were unusual for the region at this early stage; only Peru had a similar arrangement (Contreras, Reference Contreras, Nugent and Fallaw2020).Footnote 17 According to Bértola and Ocampo (Reference Bértola and Ocampo2013, p. 132), during our period of study there was a «staunch resistance on the part of large landholders to the direct taxation of their main asset: land». However, the land taxes introduced in Chile during the early 1830s, and in operation until the mid-1890s, greatly improved the extractive capacity of the state.

The next attempt to introduce a direct income tax in Chile, in 1865-7, was designed to fund the war against Spain; another temporary income tax was introduced because of falling revenues from import duties (because of the war itself), but it was also short-lived (Marshall, Reference Marshall1939; Agostini and Islas, Reference Agostini, Islas and Jaksić2018).Footnote 18 The main reason for its failure, according to the finance minister in 1866, was that Chileans underdeclared their earnings, or did not declare an income at all.

Thanks to the implementation of these internal taxes, temporary or permanent, direct or indirect, between the 1830s and the beginning of the War of the Pacific (1879), the new Chilean state was developing an improved and extensive tax capacity (Soifer, Reference Soifer2015, p. 163; see also Vom-Hau et al., Reference Vom-Hau, Peres-Cajías and Soifer2021, for a similarly positive interpretation). Chilean bureaucracy gained more relevant experience to pave the way for the implementation of new direct taxes. The «technical» barrier was becoming less of a constraint for the fiscal authority. In fact it was politicians who proved more resistant to change. That said, the urgency caused by a fiscal crisis (whether combined with an international trade crisis or not), such as the one suffered by Chile from the mid-1860s due to a shortage of public revenues (see below),Footnote 19 paved the way to introduce new forms of direct taxation, despite political opposition, since governments needed a minimum level of tax collection to run the state.

Thus, apart from the permanent patentes and the land taxes (catastro and contribución agrícola),Footnote 20 the next serious attempt to introduce a permanent direct tax in Chile was a set of taxes introduced in 1879 during an ongoing fiscal crisis experienced by Chile: a joint income and wealth tax (contribución de haberes)Footnote 21 and an inheritance tax (contribución sobre herencias). The contribución de haberes consisted of a 0.3 per cent tax on wealth (e.g. estates, capital invested in shares, bonds, loans, etc.) and a 3 per cent personal income tax on the salaries of public servants and private employees (Marshall, Reference Marshall1939; Cattaneo, Reference Cattaneo2011).Footnote 22 According to Sotomayor, a Chilean senator, the land taxes and the contribución de haberes, taken together, were equivalent to the British income tax (cited in Cattaneo, Reference Cattaneo2013, p. 18). By the late 1870s, Latin American economic authorities were well informed about the modernisation of taxation in Europe (Pinto Bernal, Reference Pinto Bernal2012).Footnote 23

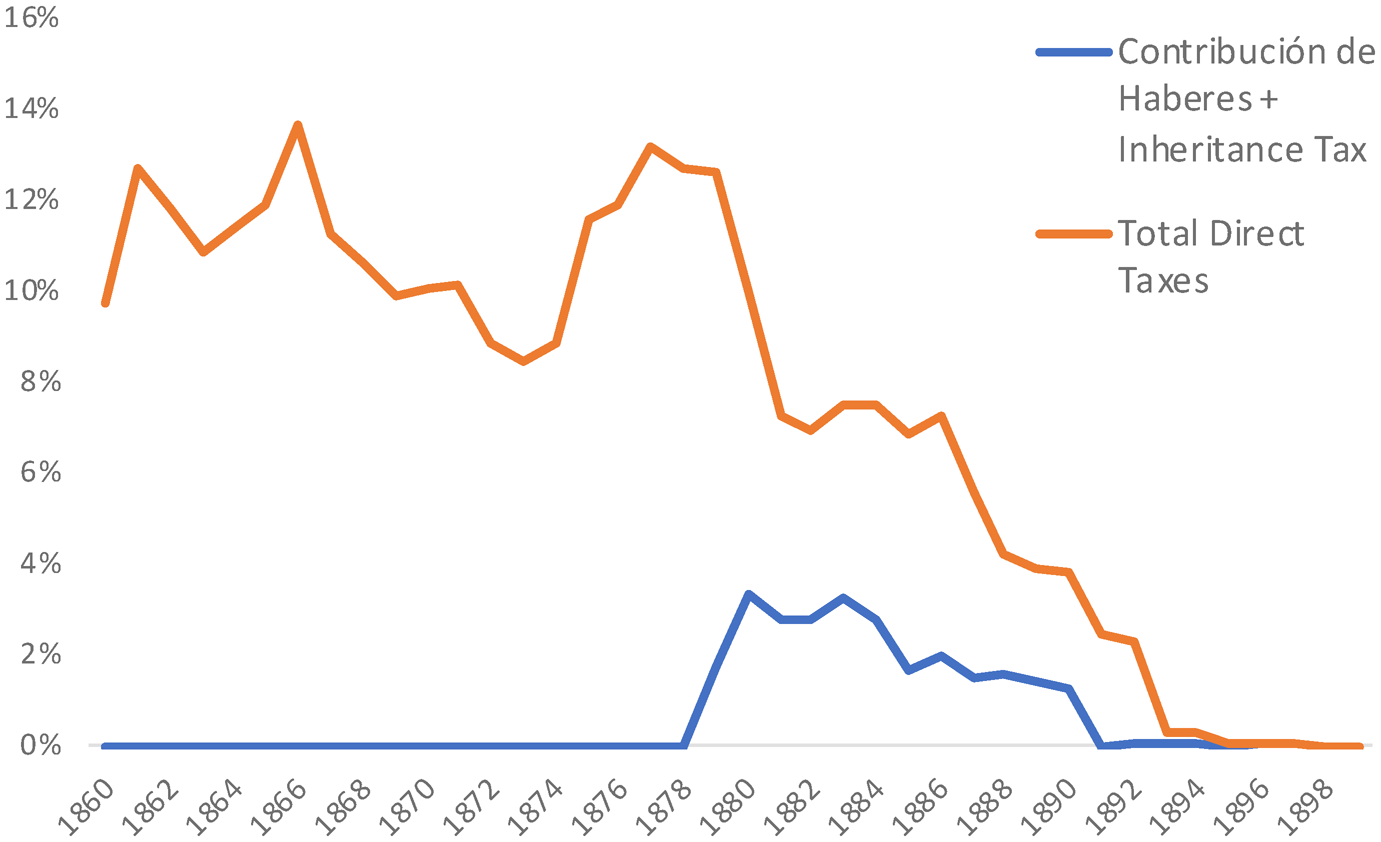

By 1880, these two new direct taxes (i.e. the income/wealth and inheritance taxes) accounted for as much as 3.3 per cent of ordinary public revenues, of which the most important was the contribución de haberes. This rate was above the share reached by direct taxes in most other previous attempts in Latin America. So significant and immediate was its impact that Augusto Matte, the Chilean finance minister in charge of implementing it, declared in 1879 that the much needed, and now achieved, equilibrium in Chilean public accounts of 1880 «se debe principalmente … a las dos fuentes de recursos creadas últimamente con la promulgación de la ley de impuesto sobre los haberes mobiliarios i de la ley que grava las herencias».Footnote 24 The urgency triggered by the fiscal crisis no doubt helped the government and parliament to decide to introduce these new direct taxes, but many necessary conditions had already been put into place making it possible; part of the economic and political elites was prone to direct taxation, while the state had enhanced its extractive capacity during the previous decades.

Despite its importance for total public revenues, as well as its political implications, this Chilean experiment has received little attention in the historiography on direct Latin American taxation (except for Sater, Reference Sater1976), which is overwhelmingly concentrated on 20th century developments.Footnote 25 In perhaps the most popular Latin American economic history textbook, it was argued that it was only from the 1930s-1940s that «countries made a major effort to raise revenue from direct taxes» (Bulmer-Thomas, Reference Bulmer-Thomas2003, p. 246). This idea has been replicated by other important scholars such as Cortés-Conde (Reference Cortes-Conde, Bulmer-Thomas, Coatsworth and Cortes-Conde2006, p. 228), who argued that it was only the 1929 crisis which triggered a tax reform, including the implementation of taxes on wealth. Other authors have also linked the implementation of direct taxation to external shocks such as WWI, the Great Depression and WWII, which greatly affected world trade and therefore customs duties collection in Latin America (Biehl and Labarca, Reference Biehl, Labarca, Atria, Groll and Valdés2018, pp. 92-95). Although we agree that it was mainly from the 1920s-1950s that a wide range of tax reforms, in which direct taxation played a major role, were introduced in Latin America (Jáuregui, Reference Jáuregui and Jáuregui2006; Bértola and Ocampo, Reference Bértola and Ocampo2013, p. 162; Contreras, Reference Contreras, Nugent and Fallaw2020; Rodríguez Weber, Reference Rodríguez Weber, Llorca-Jaña and Miller2021), there were also previous attempts worth examining, such as the tax reform introduced in Chile in the late 1870s.

Furthermore, «light personal income taxes still characterize the fiscal pact of many Latin American countries» (Biehl and Labarca, Reference Biehl, Labarca, Atria, Groll and Valdés2018, p. 110), even nowadays. A new tax reform project has just been rejected by the Chilean parliament (mid-March 2023): it aimed to introduce important changes regarding direct taxation (e.g. to fund increases in basic pensions and in public health programmes) but encountered fierce opposition from the most conservative members of Chile's parliament. Its rejection has even been labelled as «una involución conservadora» (El Mostrador, 15 March 2023). Many of the arguments given recall our case study of the 1870s-1890s. It is, then, important to understand the politics of direct taxation throughout Chilean history. We provide the first in-depth study of an important tax reform, albeit short-lived, in one of the most interesting countries in Latin America, with regard to political stability and tax discipline. Our study pays special attention to the contribution of the new taxes to total public revenues, as well as to parliamentary discussions, and why these taxes were derogated, despite their initial success and immediate positive impact on the public coffers. This is important because «there is a scarcity of studies on the politics of tax reform in Latin America… the literature has traditionally ignored its political, historical, or institutional underpinnings» (Sánchez, Reference Sánchez2011, pp. 4-5).

The economic elites of Chile did not all avoid direct taxation, despite the well-known political stability of the country (Centeno, Reference Centeno2002). Some members of this elite wanted to introduce direct taxation and were knowledgeable about modern economic theory and fiscal doctrine. Secondly, despite the difficulties of introducing and collecting a new direct tax, the Chilean state was better able than its neighbours to do so. The new direct taxes introduced in the late 1870s accounted for over 3 per cent of ordinary public revenues within the first 2 years of implementation. Within Latin America, Chile was an exceptional case with regard to the availability of economic statistical information, which was needed in order to tax wealth and income (Vom-Hau et al., Reference Vom-Hau, Peres-Cajías and Soifer2021). In 1832-4, the country managed to complete a comprehensive nationwide agricultural census (including all the nation's rural plots),Footnote 26 well before most European countries had managed to do so (Llorca-Jaña et al., Reference Llorca-Jaña, Navarrete-Montalvo and Araya2018); this was the basis of the land taxes that operated in the country for many decades to come. Between the 1840s and the 1870s, the Chilean state greatly increased its tax capacity (Brambor et al., Reference Brambor, Goenaga, Lindvall and Teorell2020; Vom-Hau et al., Reference Vom-Hau, Peres-Cajías and Soifer2021). According to the best available data (Mamalakis, Reference Mamalakis1989), average annual direct taxation grew from US$222k during the 1830s to US$1,055k during the 1870s, increasing nearly fivefold.

Third, the subsequent derogation of these important direct taxes during the late 1880s and early 1890s, mainly explained by the nitrate boom (which provided the country with easy-to-collect export duties), is the more remarkable given the lucidity of some members of the economic elite, who advocated keeping direct taxation as a means of diversifying the sources of public revenues and thus diminishing the risks of unwanted fluctuations in public revenues caused by international trade cycles. Alberto Edwards (an MP many times, as well as a minister under many presidents) made the point that, in reference to direct taxation in Chile: «Hay quienes estiman que ella debe desaparecer con la guerra y las circunstancias extraordinarias. La justicia social y el buen orden de las finanzas exigen que no sea así» (Edwards, Reference Edwards1917, p. 354). Justiniano Sotomayor, finance minister of Chile in 1889, warned that «no debe perderse de vista en las modificaciones de impuestos que la renta del salitre puede sufrir graves perturbaciones y que el país debe contar en todo caso con recursos bien garantidos para atender a la satisfacción de sus gastos ordinarios».Footnote 27 Finally, we must mention that another reason to keep direct taxation, despite increasing public revenues coming from nitrate, was to give the country the opportunity to reform and expand the public sector, and/or to fund additional public expenditure in crucial areas such as health and education. Yet, there was not much political demand for so doing from most of the Chilean elites at the time.

Our primary sources of information are Chile's parliamentary discussions, the Finance Ministry's Annual Accounts (Memorias del Ministerio de Hacienda), Chilean newspapers and other selected sources. The article deals with four topics: the economic and fiscal crisis of the second half of the 1870s (which paved the way for the introduction of new direct taxes); the creation of new direct taxes (where we explain the nature of these taxes); the challenge to collect new direct taxes, 1879-1890 (where we analyse the difficulties of collecting taxes and the solutions found by the government); and the detrimental impact of nitrate's export duties on direct taxation, 1884-1891, where we explain how the nitrate boom meant the final nail in the coffin for direct taxation in Chile.

2. The context: the economic and fiscal crisis of the second half of the 1870s

In the historiography of the new Latin American republics (c.1810s-1860s), Chile has often been prized as an example of both political stability and fiscal solidity. Chile, together with Brazil, are perhaps the only two examples of early Latin American polities that managed to collect enough taxes to ensure decent wages for governments and to avoid sizeable public deficits during the first decades after independence (Marichal, Reference Marichal, Bulmer-Thomas, Coatsworth and Cortes-Conde2008, p. 449; López, Reference López2014). However, the situation started to change from the 1860s, when a notorious deficit in Chilean fiscal accounts became too evident, becoming particularly serious between the mid-1860s and the mid-1870s, as can be seen from Figure 1.

Figure 1. Chile's public sector surplus or deficit (per cent of GDP), 3-year moving average, 1834-1899.

Source: Own elaboration based on data from Díaz et al. (Reference Díaz, Luders and Wagner2016).

According to Pastén (Reference Pastén2017), by the 1860s the Chilean Treasury started to suffer because of a lack of revenues, which triggered higher dependence on external debt and/or asset confiscation (see also Soifer, Reference Soifer2015).Footnote 28 This was exacerbated later by the economic crisis of the 1870s, arguably the most severe economic downturn faced by the new republic up to that point, and which was almost global in nature. For Gabriel Palma, «Chile had been experiencing economic crisis since 1873; and towards the end of the decade this crisis was fast becoming unmanageable» (Palma, Reference Palma, Cárdenas, Ocampo and Thorp2000, p. 217). Its detrimental impact on custom duty collection was evident, triggering a fiscal crisis and calling for the implementation of new direct taxes in Chile to diminish dependence on foreign trade duties (González, Reference González1889; Sater, Reference Sater1976; Ortega, Reference Ortega2010; Agostini and Islas, Reference Agostini, Islas and Jaksić2018).Footnote 29

In 1877, a group of MPs pressed hard to reinstall a previously introduced project of inheritance tax (abandoned during the late 1860s), as well as another scheme for a permanent income and wealth tax.Footnote 30 This urgency was unsurprising as direct taxes, including income tax, are more likely to be adopted in times of fiscal spending pressures (Aidt and Jensen, Reference Aidt and Jensen2009). However, in Chile, in the late 1840s, many members of the economic elite were campaigning for the introduction of new taxes beyond custom duties, including the influential finance minister, Manuel Camilo Vial, who argued that the government did badly by continuing to trust unstable customs duties (cited in Cattaneo, Reference Cattaneo2013, p. 89). From the 1840s onwards, there were voices from the economic and political elite calling for the introduction of direct taxes, in line with Europe's fiscal doctrine of the time.

3. A taxation revolution: the creation of two new direct taxes

In the history of Chile's fiscal accounts (Mamalakis, Reference Mamalakis1989), as the tithe had been abandoned by the mid-1850s, by 1878 the only direct taxes in operation in Chile were the land tax and the «trade and professional licenses» (patentes), which were highlighted even by contemporaries (Edwards, Reference Edwards1917). The land levy (then called Impuesto Agrícola) was taxed at 9 per cent of the annual rent (renta) of all agricultural plots with an annual rent above $100. In 1880, this threshold was lowered to $25, thus incorporating around 30k from new rural properties in tax, which meant that a new agricultural census (catastro) had to be produced by the Chilean state. This was a Herculean task for a small nation whose entire population was slightly above 1 million people (Díaz et al., Reference Díaz, Luders and Wagner2016).

The patentes, a long-established direct tax which was expanded and reformed in 1866, taxed selected professions and firms at either 2 per cent of their annual income or a fixed amount established by the fiscal authority, whichever the taxpayer chose. It also showed that the Chilean state had a significant tax capacity. The final list of those who had to pay patentes was produced by a departmental commission appointed by the local governor, and it included a fiscal employee, a local businessman and a local resident (Anguita, Reference Anguita1912, vol. II, p. 429).

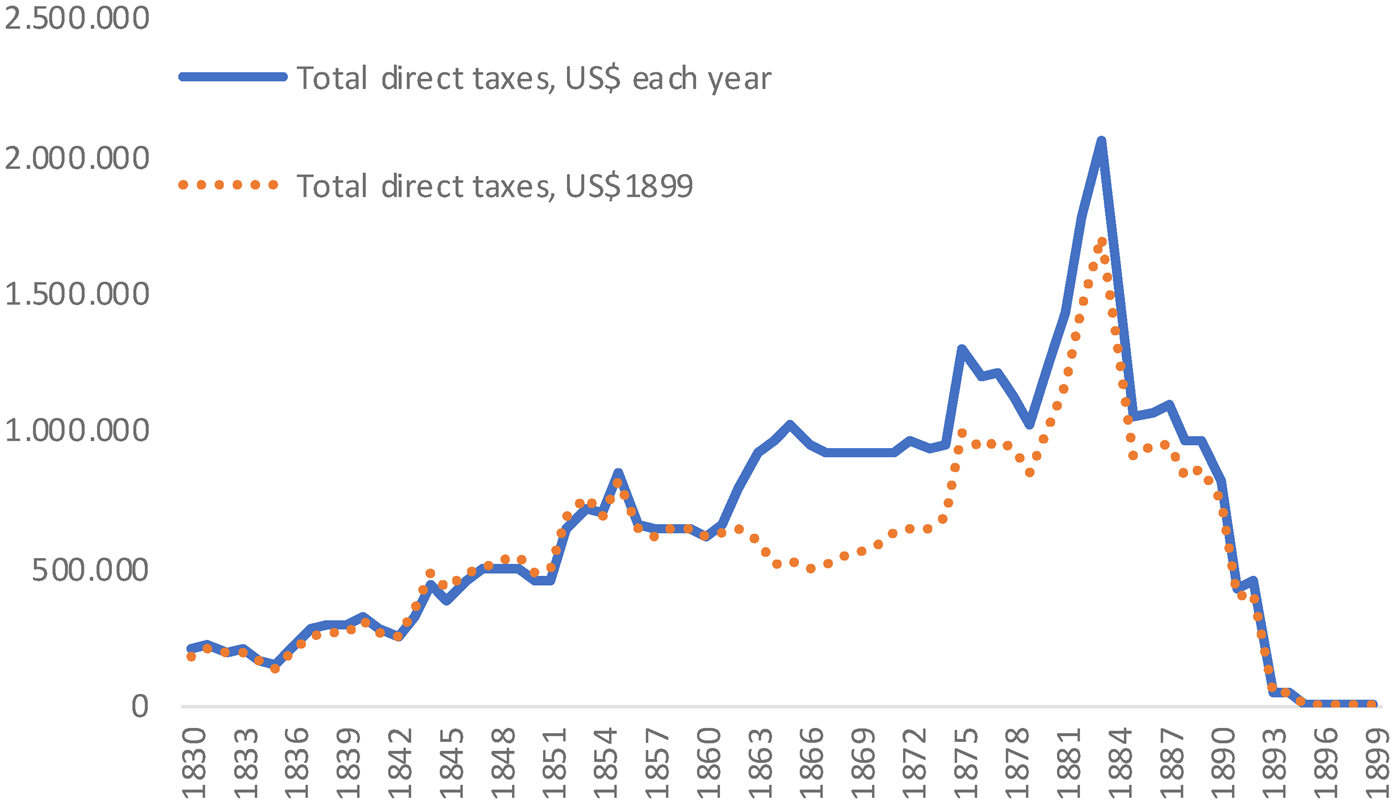

Thanks to these two old direct taxes, and those that preceded them, direct tax collection had increased steadily from the 1830s to the mid-1870s (reaching a peak of US$1.3 million in 1876). This was in part due to a more efficient tax collection system, and in particular to a massive increase in land tax collection from 1875 following the updating of the catastro in 1874.Footnote 31 However, by 1879 total direct taxation had gone down to US$1.0 million (Figure 2), from an all-time peak of $1.3 million in 1875. Urgent action was needed to provide a decent revenue for the state, especially as customs duty collection had also declined, from a peak of US$7 million in 1873 to US$4.5 million in 1879 (Mamalakis, 1989),Footnote 32 increasing the nation's reliance on foreign borrowing and aggravating the fiscal deficit (Figure 1).

Figure 2. Total direct tax revenues in Chile (US$ of each year and US$ of 1899), 1830-1899.

Source: Own elaboration from Mamalakis (Reference Mamalakis1989), Díaz et al. Reference Díaz, Luders and Wagner2016 (exchange rates) and CPI for the US from Officer and Williamson (Reference Officer and Williamson2023).

In response to this fiscal crisis, as well as to the imminent war against Peru and Bolivia (the War of the Pacific),Footnote 33 which required urgent funding,Footnote 34 two new direct taxes were implemented by the Chilean parliament and appeared in public revenues from 1879. According to senator Eulogio Altamirano's retrospective assessment, it was only the imminent beginning of the War of the Pacific that led to the Chilean Congress approving these new taxes:

Fue necesario que llegara un momento solemne para el país, que nos viéramos amenazados por una guerra extranjera y que esa guerra nos sorprendiera desarmados y sin recursos, para que un proyecto sobre contribución mobiliaria se abriera camino y fuera ley de la república… No era porque hasta entonces no se hubiera visto la enorme injusticia de que los millonarios que tiene su fortuna en bonos o dinero dado a interés escaparan del impuesto. No; todos reconocían esa injusticia y, sin embargo, no pudo ponérsele remedio. Fue necesario, como digo, que tuviéramos sobre nosotros una guerra.

The first new direct tax was an inheritance tax, which taxed the value of the inherited assets at between 1 and 8 per cent, according to the kinship between the deceased and the heir.Footnote 35 The government's target for this first new tax was to collect $400k per annum (some US$267k at that time).

More important, as far as public revenues are concerned, was the star of this process: the introduction of the Contribución de Haberes, which has been labelled as the first serious trial of a permanent income tax in Chile (Agostini and Islas, Reference Agostini, Islas and Jaksić2018). It taxed both financial assets (e.g. bonds, shares) and the urban estates of wealthier property owners at 0.3 per cent. The value of the assets to be taxed was self-declared by the taxpayers.Footnote 36 It also taxed the salaries of both public servants and private employees who earned above a certain threshold at 3 per cent (i.e. it excluded low earners). It was therefore a sui generis blend of «income and wealth» tax, although highly unbalanced; revenue collection from salaries was far more important (about two-thirds of the new tax collection came from income tax, and a third from the wealth tax).

The establishment of these two new progressive taxes and their combined relative importance within government total revenues must be taken as a landmark in the history of taxation for Latin America:

though customs revenues continued to dominate state income, these other taxes represented a significant expansion in the state's ability to extract taxes directly from its citizens. Thus, by 1880, the Chilean state taxed wealth, income, inheritance, and the sale of properties; this constellation of revenue sources in the form of direct taxation reflected a massive expansion of extractive capacity; nothing less than the emergence of the modern tax state. (Vom-Hau et al., Reference Vom-Hau, Peres-Cajías and Soifer2021, p. 8)

For the first time the owners of urban estates were paying taxes on their assets,Footnote 37 which only landowners had done previously.

In quantitative terms, in 1883 the Chilean government managed to collect US$2.1 million in direct taxes, of which nearly US$900k (over 40 per cent) came from these two new taxes introduced in 1879. During the 1840s, on average, the Chilean government collected US$1.6 million annually from custom duties, its main source of income at that time. In 1883, the US$900k collected from these two new direct taxes was equivalent to 57 per cent of the revenues collected from the main source of income of the Chilean state in the 1840s (i.e. customs duties). In 1917, reflecting on the importance of total direct taxes, Edwards stated that «el sistema tributario de Chile tendía hacia 1880 a acercarse al de países de civilización muy superior» (Edwards, Reference Edwards1917, p. 343).

Furthermore, beyond substantially increasing fiscal revenues, an important development in itself, the political and fiscal significance of enhancing direct taxation was evident on two other fronts: the Chilean state diversified its sources of income, while also adding more stability to its revenues, and the new taxes, ceteris paribus, also reduced income and wealth inequality. This is more important given «the historic pattern of relatively light tax burdens borne by the elites in this part of the world long marked by high levels of inequality» (Sokoloff and Zolt, Reference Sokoloff and Zolt2006, p. 276). Bértola and Ocampo (Reference Bértola and Ocampo2013, p. 132) noted that direct taxation «was a particularly attractive option for some liberal thinkers» during the late 19th century in Latin America, as a means of reducing this income inequality, and Chile was no exception (Ortega, Reference Ortega2005, pp. 378-379).Footnote 38 The previous tax system, not only in Chile, but elsewhere in the region,Footnote 39 was over-reliant on indirect taxes, that «fell disproportionately heavily on the poor» (Bulmer-Thomas, Reference Bulmer-Thomas2003, p. 278), thus giving the fiscal system a regressive character (Bulmer-Thomas, Reference Bulmer-Thomas2003; Sokoloff and Zolt, Reference Sokoloff and Zolt2006; Garavaglia, Reference Garavaglia2010; Pérez and Herrera, Reference Pérez and Herrera2013). This unjust system was clearly perceived and denounced by many Chilean MPs, including the liberal Isidro Errázuriz, for whom in Chile, before 1879, «desde luego casi todos los tributos pesan sobre los hombres de trabajo y sobre los industriales, no sobre los ricos».Footnote 40

Or, as Colin Lewis succinctly explained, «in as much as tariffs were applied mainly to imports and represented a tax upon consumption, the burden of revenue provision fell disproportionately upon poorer members of the community» (Lewis, Reference Lewis and Bethell1986, p. 297). Writing from London on the eve of the tax reform of the late 1870s, Charles Lambert, the famous Anglo-French entrepreneur who previously resided in Chile for many decades, made this point eloquently, albeit in Spanish:

El rico paga como el pobre, pero nada paga por la prosperidad o fortuna de que goza, y sin embargo éste es el que más grita cuando se le amenaza con un aumento de contribuciones. Existe acaso en Chile un Profits Tax, House Tax, Income Tax, y diez o veinte otros Taxes, ¡Ninguno! ¡Una miseria que no pagan en cada una de estas cubriría el miserable déficit que existe! Las contribuciones de los paisanos tan gastadores y tan patriotas de boca no alcanzan ni para vestir decentemente a los soldados y policiales ¡Vaya amigo que incomoda hablar de estas cosas! Para Bailes, para el juego, para lujos, hay plata, para la Patria no hay nada! Footnote 41

Although these two new direct taxes were successfully introduced, there was fierce opposition from some sectors of the parliament, and even from inside the government.Footnote 42 For example, Augusto Matte, then finance minister, was initially opposed to the tax reform and deployed weak arguments against it, provoking a strong response from the liberal MP Luis Aldunate:

Señor, si para no imponer nuevas contribuciones, si para no alarmar ni herir intereses individuales, sino para no atacar al gran capital, en una palabra, hemos de continuar viviendo de prestado y apelando hoy, mañana y siempre al eterno y peligrosísimo recurso de los empréstitos, me parece que voluntaria y conscientemente nos dejaríamos arrastrar a un abismo.Footnote 43

Eventually both the inheritance tax and the Contribución de Haberes were approved, first by the Cámara de Diputados (lower chamber), and in November 1878 by the Chilean senate (upper chamber of parliament). Chile was setting a good example within Latin America on how to increase and diversify tax revenues, and how to improve social justice.

4. The challenges to collect the two new direct taxes, 1879-1890

There are many challenges to introducing direct taxation in developing countries. It is imperative to acquire accurate information on both taxpayers and their incomes/assets, as well as to have sound institutions (including honest and efficient tax officers) in place to collect taxes. In 1866, when an income tax was trialled in Chile, Alejandro Reyes, the finance minister, recognised that the government did not have «exact information to calculate how much would enter to the fiscal coffers with a 5% income tax».Footnote 44 Apart from these challenges, for direct taxation to become an important source of revenue for a country it is necessary to have honestly maintained accounting records; voluntary compliance (and honesty) on the part of taxpayers; and an absence of economic elite groups with political power to block or hinder direct tax collection whenever they consider a threat to their position (Tanzi, Reference Tanzi1966, p. 157; see also Soifer, Reference Soifer2015, p. 181).

In the early 1880s, soon after both the Contribución de Haberes and the inheritance tax had been introduced, the Chilean government decided to re-organise part of the Finance Ministry the better to collect these two new taxes. This reorganisation included the creation of the Treasury Directorate (mainly in charge of centralising the treasury administration and its resources) and the Accountancy Directorate (empowered with the supervision of all financial offices and keeping up-to-date fiscal records). One of the aims of these reforms was to have an accurate record of those to be taxed (either firms or persons).Footnote 45 After all, «some basic knowledge about the demographic characteristics, wealth, and whereabouts of individuals and their households and businesses is required in order to tax effectively» (Vom-Hau et al., Reference Vom-Hau, Peres-Cajías and Soifer2021, p. 3). A second goal was to supervise the work and integrity of tax collectors.Footnote 46 This is unsurprising as whenever any 19th-century Latin American government tried to collect direct taxes, «economic actors competed to woo tax officials and political patrons for preferential treatment» (Biehl and Labarca, Reference Biehl, Labarca, Atria, Groll and Valdés2018, p. 105).Footnote 47 A third objective was to replace the state's tax-extractive capacity that had been partially impaired because of the derogation of the tobacco estanco (see below), which meant that many tax offices were closed throughout the republic. Thanks to the reforms of the early 1880s, new and modern tax offices were opened and new tax officers were deployed in the totality of the 70 Chilean departments,Footnote 48 signalling the beginning of a new era in the country's history of tax collection.Footnote 49

Yet, despite these reforms, there were many specific additional challenges to be faced by fiscal authorities when collecting the contribución de haberes. This tax had two components, since it taxed both wealth and income. Wealth taxation was perceived as less problematic by the finance minister since the state had secure ways to oversee and to value the main financial assets to be taxed (by using bank reports, company reports, official share information), but also because this small tax (0.3 per cent on the value of the asset) was widely accepted by most members of the local business community perhaps because it was perceived as rather low (in particular if compared to the proposed rate in the original project).Footnote 50 After all, the lower the tax, the lower the evasion.

The role of income tax as part of the Contribución de Haberes is a different story. Here the state faced evasion and political opposition. This was unfortunate since direct taxes on income «presuppose consent and trust. They require people to fill tax returns and let their incomes be assessed» (Biehl and Labarca, Reference Biehl, Labarca, Atria, Groll and Valdés2018, p. 93). The issue here was that this income tax was mainly based on the taxpayers' own and voluntary declarations. For a contemporary, Velsué, this was the greatest drawback to this tax since «se confía demasiado en la honorabilidad del ciudadano» (Velsué, Reference Velsué1880, p. 10). For public servants this was not an issue, since the state had an accurate record of the salaries paid to them, and therefore a comprehensive list of those who were and were not required to pay taxes. The national public budget, freely available, contained this information (Barría et al., Reference Barría, Llorca-Jaña and Sepulveda2021).

Thus, the potential for evasion came mainly from private employees many of whom excluded themselves from the tax, arguing that their contracts were on a daily or weekly basis and that by law only those with monthly or annual contracts had to pay this tax.Footnote 51 This trick reduced the pool of private employees contributing to this tax substantially. Although it was widely known that the largest portion of those who had, in theory, to pay this tax were private employees (rather than public servants), as much as two-thirds of total tax collection for this item came from public servants,Footnote 52 unfortunately for the state. This also led to complaints from public servants about being unfairly treated by their own state. After all, our willingness to pay income taxes improves if we perceive that personal income taxation is a fair system that applies to the many rather than the few. In the words of Levi: «even when people prefer to pay, they still require assurances that others also are paying» (Levi, Reference Levi1988, 67).

Despite these challenges, between 1879 and 1883 the government managed to collect increasing amounts of revenues under this tax category, jumping from US$131k in 1879 to US$785 in 1883. Thus, the implementation of this new tax was perceived as a success, given the country's history. Yet, in mid-1884 an unexpected blow came directly from inside parliament. The liberal MP Julio Zegers (who happened to be the former finance minister) argued that the state was now collecting handsome revenues from nitrate exports, and that inflation was affecting the real income of both private and public employees. Zegers thought that it was the right time to derogate the income tax part of the Contribución de Haberes, making a formal proposal to the Congress.Footnote 53 Thus, with around two-thirds of the votes, the part of the Contribución de Haberes coming from income taxes was derogated.Footnote 54 This was the first of many more upsets to come with direct taxation in Chile. It was the beginning of a complete collapse of the system of direct taxes and signalled a return to the old, even more primitive, tax system which was over-reliant on indirect taxes mainly linked to foreign trade. The incident shows that, as far as the introduction and/or keeping of direct taxes is concerned, rather than some factors being more important than others, at least two factors were necessary conditions: a minimum level of tax extractive capacity by the state and a minimum support from part of the political elite.

Although inheritance tax was (in theory) less problematic to collect, the government fell short of its intended target, never collecting the $400k per annum it had envisaged back in 1879.Footnote 55 The maximum amount collected in any year was $245k, collected in 1886. In 1889, the finance minister blamed the huge delay between the date of the death of the person owning the goods to be inherited and the date that the probate process was fully completed, as well as the usual practice of undervaluing the assets included in the will.Footnote 56 The government tried to enforce a maximum period of 12 months between the beginning of the succession process and its eventual completion. However, this was difficult to put into practice as there were many legal loopholes available to those who wanted to avoid paying inheritance taxes. Often the richest Chilean families, who were called on to be the largest contributors, when faced with the death of the family business leader intentionally delayed the partition process, continuing business as usual for as long as possible to avoid paying inheritance tax (Nazer and Llorca-Jaña, Reference Nazer and Llorca-Jaña2022).

Despite these difficulties, between 1880 and 1884, the Chilean state managed to collect a sizeable amount of revenues with these two new taxes, especially the Contribución de Haberes. As can be seen in Figure 3, between 1880 and 1884 as much as 3 per cent of all ordinary public revenues came from these new two taxes (inheritance and haberes); the amount decreased gradually from 1885. This relatively successfulFootnote 57 process, albeit for the short period 1880-1884, was «clearly a consequence of the information capacity» the Chilean state «had developed in the preceding decades» (Vom Hau et al., Reference Vom-Hau, Peres-Cajías and Soifer2021, p. 9), in particular thanks to the previous collection of other taxes such as the agricultural tax and the tobacco estanco. For example, the changes introduced from 1874 to increase the land tax (see above) is a good example of this, as well as the changes to improve patentes from 1866, which increased patentes tax collection almost fivefold within a few years.Footnote 58

Figure 3. Share of direct taxes over total ordinary fiscal revenues in Chile, 1860-99.

Source: Own elaboration from Mamalakis (Reference Mamalakis1989).

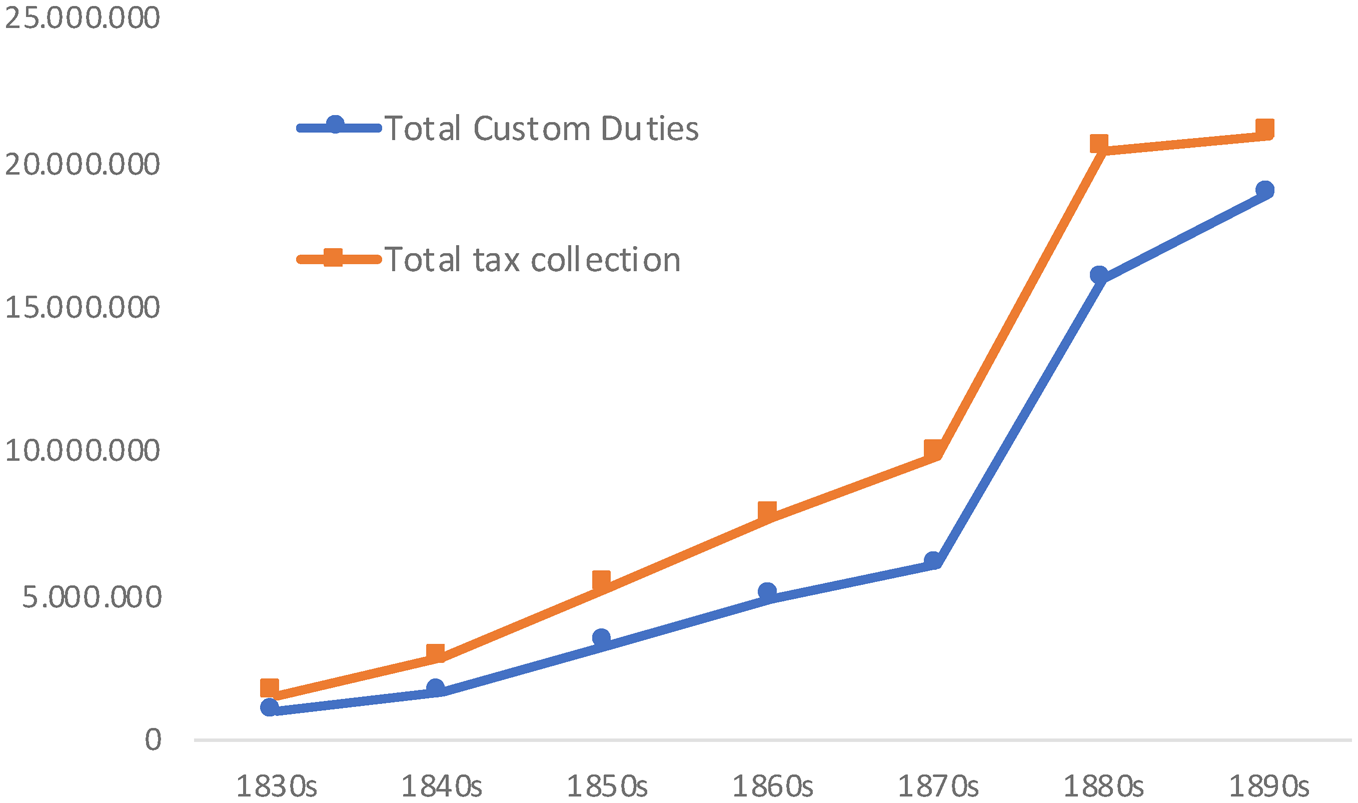

5. The detrimental impact of export duties on nitrate on direct taxation, 1884-1891: another export boom shaping taxation

Chile's victory over Peru and Bolivia in the War of the Pacific (1879-1884) reshaped the national economy, not only because the export basket was transformed, but also because the size of the country expanded dramatically. After the peace treaties signed with both Peru (1883) and Bolivia (1884), Chile secured the large northern provinces of Antofagasta and Tarapacá, which contained rich nitrate deposits. Chile started to enjoy a global monopoly of this natural fertiliser, marking the beginning of the so-called nitrate era in Chilean history, c.1880s-1930s (Miller, Reference Miller, Llorca and Miller2021; Peres-Cajías et al., Reference Peres-Cajías, Torregrosa-Hetland and Ducoing2022). This provided a dramatic boost to the export economy; in 1878 total exports were US$23 million, but by 1890 they had increased to US$52 million (Díaz et al., Reference Díaz, Luders and Wagner2016). One of the first decisions on fiscal policy taken by the newly expanded Chilean state was to impose an export duty on nitrate; it was a fixed amount per 100 kg exported (and collected in gold), rather than an ad valorem rate. It was regarded by Chilean authorities as an intelligent decision since it was an indirect tax that relied mainly on foreigners as all nitrate was consumed abroad.Footnote 59 The impact this had on Chile's public finances can be seen in Figure 4; total ordinary revenues during the 1880s were double those of the 1870s.

Figure 4. Chile's ordinaryFootnote 61 public revenues, annual averages per decade, 1830s-1890s (US$): customs revenues vs total revenues.

Source: Own elaboration from Mamalakis (Reference Mamalakis1989) converted into US dollars using exchange rates from Díaz et al. (Reference Díaz, Luders and Wagner2016).

The buoyant export economy of the nitrate era, which came together with the establishment of the above-mentioned export duties on nitrates and with increasing total fiscal revenues, led to the collapse of Chile's preceding tax structure, and in particular of direct taxation (Agostini and Islas, Reference Agostini, Islas and Jaksić2018; Biehl and Labarca, Reference Biehl, Labarca, Atria, Groll and Valdés2018, p. 97). Chile made the same political mistake as Peru during Lima's guano era (Contreras, Reference Contreras and Jáuregui2006).Footnote 60 As in the guano boom in Peru, «a country whose population was the recipient of public spending but not the source of its revenues» (Contreras, Reference Contreras, Nugent and Fallaw2020, p. 48), taxpayers witnessed a massive reduction in their tax loads.

After all, it was the easier course of action: «taxing nitrate deposits was technically relatively easy and inexpensive» (Gallo, Reference Gallo, Bräutigam, Odd-Helge and Moore2008, p. 181). By derogating direct taxes, as well as indirect internal taxes, and instead relying too heavily on nitrate export duties, the Chilean state could avoid «the difficult political question of burdening other taxpayers by taking its revenues [solely] from mining rents» (Cortes-Conde, Reference Cortes-Conde, Bulmer-Thomas, Coatsworth and Cortes-Conde2006, p. 212). Government income from nitrate export duties became so abundant, compared with the previous decades, that there was no need to resort to permanent direct taxes (Thorp, Reference Thorp1998). Customs duties (now mainly based on export duties)Footnote 62 increased from US$4.5 million in 1879 to over US$20 million per annum during both 1882 and 1883 (Mamalakis, Reference Mamalakis1989).

Nonetheless, some authors have argued that despite increasing public revenues, there was also more expenditure and social demand which needed to be covered, and which could not be funded solely with nitrate export duties (Pastén, Reference Pastén2017). Thanks to nitrate export duties, increasing fiscal revenues allowed Chile to modernise many state institutions; to expand the size of the state (including hiring more public employees); to invest in new public goods such as public buildings, ports and many other public works; and to invest in education by expanding school enrolment in primary, secondary and tertiary education (Barría, Reference Barría2018). Furthermore, increasing fiscal revenues also allowed Chile to reconvert its external debt to diminish the burden of interest payments (Millar, Reference Millar1994).

«Blessed with such a windfall, the governments of Chile from 1881 to 1891 systematically reduced the burden of non-nitrate taxes» (Bowman and Wallerstein, Reference Bowman and Wallerstein1982, p. 448); one by one most other taxes were derogated (Mamalakis, Reference Mamalakis1976; Centeno, Reference Centeno2002). For example, in 1881 the monopoly receipts (especies estancadas) were derogated.Footnote 63 Although during the later years of Domingo Santa María's presidency (1881-1886) there was a short hiatus in this tax reformation process, mainly because the government compromised in order to stabilise the exchange market (which needed fiscal resources),Footnote 64 the process soon resumed. In 1888, the excise and duties on sales of real estate (alcabala e imposiciones) were derogated.Footnote 65 That same year, the trade and professional licenses (patentes) were transferred to local councils.Footnote 66 By 1888, central government had ceased to receive any income from patentes (Mamalakis 1989).

The transfer of some tax revenues from central government to local councils can be explained. An important initial aim of Santa María's successor, José Manuel Balmaceda, was to alleviate local councils' accounts. The councils' (municipios) finances were in a poor state, characterised by high debt and low revenues, receiving little financial support from central government. By 1886, when Balmaceda took office, the councils' debt had peaked at US$3.4 million (Nazer, Reference Nazer1999). Balmaceda sent a project to the congress, whereby a new council tax was to be paid by urban properties (0.5 per cent), but it also contemplated transferring 100 per cent of the patentes' revenues and 20 per cent of the Impuesto Agrícola to local councils.Footnote 67 Balmaceda's original plan was to support local councils, although to a limited extent; central government was to retain the lion's share of tax revenues. Another complementary proposal was to waive the councils' debts (except for Santiago and Valparaiso), which was eventually approved in January 1889 (Anguita, Reference Anguita1912, vol. II, p. 98).

More important for us, once the transfer of patentes to local councils had been approved by the Congress in 1888, many further discussions took place in parliament about continuing to dismantle the tax structure in an effort to go beyond Balmaceda's proposal. It is not possible here to summarise all the parliamentary discussions, but a telling intervention was made by Justiniano Sotomoyar in 1889, then finance minister, who argued that «la situación holgada del Erario Nacional permite acometer la revisión completa de nuestro sistema tributario para perfeccionarlo corrigiendo los defectos de que adolece».Footnote 68 He was advocating the derogation of all direct taxes. Two years later, another finance minister, Pedro Montt, made a similar point, campaigning to abolish both the inheritance tax and the contribución de haberes, arguing that both had been created during an exceptional economic crisis which no longer existed:

creo que el dinero no se encuentra en ninguna parte colocado con más provecho que en el bolsillo de los contribuyentes y mientras la administración marche tranquila y regularmente, mientras las obras públicas emprendidas puedan continuarse sin tropiezo y podamos a la vez suprimir parte de los gravámenes que pesan sobre el pueblo, nuestro pueblo se encontrará bien resguardado y, en ninguna parte, repito, colocado el dinero con más provecho que en el bolsillo de los contribuyentes.Footnote 69

In 1891, the emblematic inheritance tax, a matter of pride for so many liberals in Chile, was also derogated. Furthermore, that same year the Contribución de Haberes, which had already been severely damaged in 1884 by excluding the income tax section, was modified and fully transferred to local governments (councils) after the promulgation of the Ley de Comuna Autónoma (Edwards, Reference Edwards1917, p. 344; Gallo, Reference Gallo, Bräutigam, Odd-Helge and Moore2008; Bernedo et al., Reference Bernedo, Camus and Couyoumdjian2014; Barría, Reference Barría2018; Rojas, Reference Rojas2019), a law that was far more radical than the original plan envisaged by Balmaceda.Footnote 70 Indeed, this law was only approved after Balmaceda's government had been defeated.

Part of the transfer of some direct taxes from central government to local councils, intended to alleviate the councils’ poor finances, was also the result of the political tensions between Balmaceda and his opponents (mainly at the Congress) that started to escalate from the second half of 1889 (Barría, Reference Barría2013), ending with the Civil War of 1891. At the centre of this political dispute was the extent of control of both tax collection and tax expenditure, which resulted in this additional transfer of taxes from central to local government, to the benefit of the councils and to the detriment of the president. The aim of those advocating as many transfers as possible was to diminish the economic power of President Balmaceda as much as possible (Barría, Reference Barría2013). This idea came mainly from the conservative leader Manuel José Irarrazabal, one of the main opponents of Balmaceda (Salas, Reference Salas1914, p. 227).

After the derogation of so many taxes, or their transfer from central to local government, Chilean central government became, once again dependent on customs duties as its main source of income (Marshall, Reference Marshall1939; Miller, Reference Miller, Llorca and Miller2021). A slight difference if compared to previous periods was that the emphasis was now on export duties rather than import taxes. In 1892, the land tax, the main source of income for the central government in Chile for a long period, was also modified and then transferred to local councils. By 1895, direct taxes provided no income whatsoever for central government finances in Chile (see Figure 2): «la riqueza estaba exenta de impuestos fiscales de todo género» (Edwards, Reference Edwards1917, p. 345). For a quarter of a century, until 1916, 100 per cent of government revenues came from a few indirect taxes (Marshall, Reference Marshall1939; Palma, Reference Palma, Cárdenas, Ocampo and Thorp2000, p. 251; Sokoloff and Zolt, Reference Sokoloff and Zolt2006, p. 225). Apart from customs duties, the only other tax to survive was on stamps. This is a clear example of a commodity boom shaping taxation, but for the worse; the Chilean state dismantled its tax apparatus as resources from nitrate flowed in (Soifer, Reference Soifer2015). Half a century earlier, in Peru during the guano export boom, direct taxation had been completely derogated (Contreras, Reference Contreras and Jáuregui2006). Latin American policy makers made the same mistakes as the neighbouring authorities.

The derogation, modification and/or transfer of direct taxes to local councils in Chile during the nitrate era can only be seen as «una política financiera fácil y paternal, un manejo negligente de los intereses fiscales» (Edwards, Reference Edwards1917, p. 355; see also Miller, Reference Miller, Llorca and Miller2021). As far as public revenue is concerned, we could think that more revenue collection is always better than less, at least for those states that face huge social demands and the need to provide basic public goods, such as Chile at that time. Yet history is plagued with examples of rulers and governments that do not maximise state revenues (Levi, Reference Levi1988), being our object of study a case in point. This was unfortunate for the bulk of the population since public expenditure requirements during this period were extensive; the state could have funded more public education, more provision of public infrastructure and could have met many other needs, had it had more resources. More importantly, «despite the enormous revenues derived from nitrate taxes, a budget deficit was recorded in almost every year during this period» (Palma, Reference Palma, Cárdenas, Ocampo and Thorp2000, p. 235, and our Figure 2). There is no economic logic to suffering from a budget deficit and at the same time deciding to reduce your revenues. During the parliamentary discussions of 1889, when it was evident that all direct taxes were to be derogated, the MP Alberto Gandarillas observed that «si suprimimos una por una las contribuciones existentes, vamos a decapitar nuestro sistema tributario y dar lugar a que se presente tal vez una gran crisis económica».Footnote 71 Time proved him right.

This public deficit, in part due to the derogation of both the old and the new direct taxes, made of the post mid-1880s tax reform an outrageous economic policy. It was effectively a transfer of resources from the state to the economic elites, with public revenues dependent on an unstable external sector (Palma, Reference Palma, Cárdenas, Ocampo and Thorp2000). This was the result of bad policies under an unequal society: «extreme inequality can result in elites minimizing their relative tax burdens» (Sokoloff and Zolt, Reference Sokoloff and Zolt2006, p. 205), even if that meant damaging the state. It is even more surprising since high-ranking government officials were fully aware of this situation. In 1882, Pedro Lucio was the finance minister when direct taxation was still in force and provided handsome revenues for the government. He made it clear that indirect taxes (such as customs duties) did not have

la elasticidad tan conveniente para graduar los recursos con las necesidades de la nación, en tiempos de prosperidad y de paz, como en los de escasez y guerra. A fin de poder equilibrar, en todas épocas, las entradas con los gastos públicos, es preciso conservar, mejorándola, la contribución mobiliaria, i aun extender el impuesto directo a toda la propiedad raíz. Solo de esta manera llegaremos a regularizar nuestro sistema fiscal sobre bases justas y convenientes para los intereses de todos.Footnote 72

This reminds us of what would happen in many Latin American countries a few decades later, when the detrimental impact of the First World War «forced the state to impose domestic taxes on its elites to survive … with the underlying agreement that world demand for natural resources would recover, thus making domestic taxation unnecessary» once the war had ended (Biehl and Labarca, Reference Biehl, Labarca, Atria, Groll and Valdés2018, p. 91). The fact that the derogation of direct taxes during the nitrate era in Chile was a gross mistake was proved a decade later. Many of the derogated taxes, together with new ones, were swiftly introduced or reintroduced to assuage the unchecked fiscal deficit that was proving too damaging for the entire economic system (Hanson, Reference Hanson1936; Soifer, Reference Soifer2015, pp. 172-173).

6. Conclusions

We have shown in this article that an important tax reform was implemented in Chile during the late 1870s, when the country was suffering a severe economic and fiscal crisis, on the eve of the War of the Pacific. At the end of this multifarious crisis period, in 1879, the Chilean government introduced a new set of direct taxes which resulted in a significant increase in tax revenues. They were a tax on inheritance, and more importantly, a blended income and wealth tax, both of which were successfully introduced despite the historic resistance of most of the economic elites to direct taxation in a highly unequal society. In 1878, a few months before these direct taxes were eventually introduced, Blest Gana, a highly influential Chilean intellectual and diplomat, wrote from Paris to the former Chilean president, Aníbal Pinto, showing his scepticism regarding the actual implementation of these taxes:

Veo por los diarios que el señor Ministro de Hacienda se ocupa de estudiar un proyecto de contribución sobre la renta. Ese sería, indudablemente, un medio salvador si llegase a ponerse en planta. Mas, ¿cuántas demoras, cuántos obstáculos va a encontrar ese valiente propósito? No se necesita, me parece, estar dotado de una perspicacia excepcional para vaticinar que serán infinitos.Footnote 73

Perhaps Blest Gana, being resident in France, had not perceived that some important changes had, gradually, taken place in his own country during the previous decades, which could be labelled as important pre-conditions; the Chilean state had enhanced its tax extractive capacity, while some sectors of the political elites were now devotees of direct taxation.

Indeed, this tax reform also shows many interesting features of Chile's economy and internal politics. First, the economic elite was not fully homogenous, as is usually thought, regarding resistance to direct taxation. It is true that an important part of the economic elite remained reluctant to increase direct taxation, but an economically liberal sector of the same elite was influential enough to introduce two new direct taxes. While the imminent War of the Pacific was a factor (i.e. the elite had no choice), the Congress had at their disposal many other alternatives, such as increasing indirect taxes.

Second, despite other challenges faced by any developing country to extract taxes from its population (e.g. the lack of both proper information and human capital), during c.1879-1884 the process of tax collection from these two new direct taxes can be regarded as successful, at least regarding the country's own history. Direct taxation increased substantially during this short period of time, and this was mainly due to the improved extractive capacity of the Chilean state, which had been slowly built up during the preceding decades.

Yet, despite this temporary success, from the mid-1880s the whole reform was gradually eroded by the most conservative element of the economic elite, and by the mid-1890s all direct taxes (new and old) had been either derogated or transferred to local government (in some cases after being modified). Once the fiscal crisis had been left behind, taxation underwent a counter-revolution, with important consequences for social justice. Once again, Chilean central government depended entirely on a small number of indirect taxes with export duties on nitrate being the most important. The government certainly did not behave as a maximiser of revenues.

Nitrate provides a good example of an export boom shaping taxation for the worse; rather than increasing and diversifying the sources of revenue (to fund social needs and/or public goods), a dominant and retrograde sector of the Chilean economic elite decided to stop paying direct taxes altogether and to make the state entirely dependent on the cycles of the international economy, as well as condemning the government to run chronic public deficits. However, part of the economic elite was aware of the wide range of benefits of both introducing and keeping direct taxation, even though they were defeated: social justice, financial health and less vulnerability to trade cycles were some of the benefits to be enjoyed. Unfortunately, the balance of power inclined in favour of elite groups with enough power to hinder direct taxation and to increase income and wealth inequality. As regards the derogation of all direct taxes between the mid-1880s and the early 1890s, Alberto Edwards’ judgement remains visionary:

Tengo la íntima convicción de que la falta de impuestos fiscales directos sobre la riqueza ha sido una de las causas determinantes del desorden financiero que nos llevó hace pocos años al borde de la bancarrota. No se gobierna con discursos y buenas palabras: los hombres necesitan de frenos más eficaces (Edwards, Reference Edwards1917, p. 346).

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to Rory Miller, Elvira López, José Díaz-Bahamonde, Diego Barría and Javier Rivas.

Sources and official publications

Congreso Nacional de Chile. Cámara de Diputados. Diario de Sesiones, 1876, 1877, 1878, 1879, 1884, 1888, 1889.

Congreso Nacional de Chile. Cámara de Senadores. Diario de Sesiones, 1878, 1879, 1888, 1890.

Memorias del Ministerio de Hacienda, 1865, 1866, 1879, 1880, 1881, 1882, 1883, 1884, 1886, 1889.

El Mercurio de Valparaíso, 1879 and 1889.

Charles Lambert to Jorge Huneeus. London, 16 January 1877.

Alberto Blest Gana to Aníbal Pinto. Paris, 3 May 1878.