Introduction

The outer coast of north-western North America can be unforgiving to those unfamiliar with the perils of the ocean. Unprotected by larger coastal islands, storms blowing across open water can appear without warning, sending wind and waves crashing over rugged, rocky shore-lines, and strong currents can quickly pull mariners off course and into treacherous waters. While difficult and often dangerous to access, outer coast archipelagos support a diverse range of marine resources, many of which were important and desirable for ancient peoples. Indeed, these areas were probably some of the first places inhabited by the earliest Indigenous occupants of North America (Waters Reference Waters2019; Braje et al. Reference Braje2020). Understanding how ancient peoples utilised these outer shores is important for documenting the lives of early mariners, but also for understanding how Indigenous coastal cultures thrived—and continue to thrive today—on these challenging landscapes (McMillan & McKechnie Reference McMillan and McKechnie2015).

The Moore Islands Paleoenvironments and Archaeology Project is a research partnership between the Department of Archaeology at Simon Fraser University, the Gitga'at First Nation and Kitasoo Xai'xais First Nation. The project explores the human and environmental histories of a small group of offshore islands in north-central British Columbia (Figures 1–3). Despite their remoteness relative to other islands and fjords of the Northwest Coast, the Moore Islands are attested in Indigenous oral histories as being culturally and economically important through deep time. The islands, known as Laxnuganaks or ‘Ngwünaks are known through the adawx (oral histories) of the Ts'msyen Indigenous Peoples as the origin place for a major lineage—the Gitnuganaks—that now exists between several Ts'msyen Nations (including the Gitga'at, Kitasoo and Gitxaała). Drawing on guidance from the Gitga'at and Kitasoo concerning their oral histories and cultural knowledge in their asserted territories, we employ palaeolandscape reconstruction and archaeology to document persistent and intensive use of the remote Moore Islands, and to search for evidence of the earliest occupation of the region.

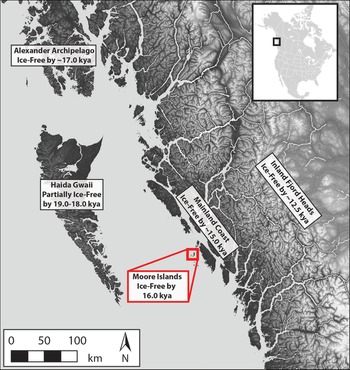

Figure 1. Map indicating the location of the Moore Islands and minimum ages of post-glacial ice retreat for selected areas (for a more detailed discussion of north coast deglaciation and for references for the ages indicated for different areas on this map, see Letham et al. (Reference Letham, Lepofsky and Greening2021)) (mapping by B. Letham).

Figure 2. The Moore Islands are small and at low elevation (photograph by B. Letham).

Figure 3. Research vessels moored in a sheltered bay. The shorelines of the Moore Islands are rocky and crenulated (photograph by I. Sellers).

Palaeoenvironmental context

The Moore Islands are situated at an important location for understanding Late Pleistocene palaeoenvironments and early human occupation of the Northwest Coast. In general, the outer coast was the earliest to be deglaciated following the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), as ice sheets retreated west–east towards the mainland (Figure 1; Clague et al. Reference Clague, Harper, Hebda and Howes1982). Furthermore, thinner ice cover away from the mainland during the LGM means that the Moore Islands were subject to lower degrees of relative sea-level (RSL) change through isostatic depression (McLaren et al. Reference McLaren2014). Thus, their shorelines have remained relatively stable for millennia, increasing the potential for preserved archaeological deposits from deep in the past (McLaren et al. Reference McLaren, White, Rahemtulla and Fedje2015).

We gathered samples for palaeoenvironmental and RSL reconstruction by coring lakes, bogs and lagoons on the islands. Radiocarbon dates on plant material and marine shells from these cores indicate that the area was ice-free and supporting marine shellfish by at least 16 000 years ago—a minimum of 1000 years earlier than the mainland coast—and dates on wood indicate that the islands were vegetated by at least 15 500 years ago. The cores’ sedimentary sequences indicate that RSL has indeed been relatively stable on the islands since deglaciation; for at least the last 15 500 years, shorelines have been subtly fluctuating above and below modern sea-level elevation. These data indicate that the Moore Islands were hospitable to humans following the LGM well before much of the Northwest Coast, and that archaeological remains of early occupation of the islands should survive close to the modern shoreline.

Preliminary archaeological findings

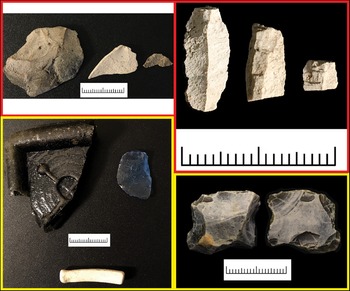

Our archaeological survey of the Moore Islands has been guided by our RSL reconstruction, and our preliminary work demonstrates that far from being a lightly used, remote outer locale, people have occupied the area persistently and intensively for at least the last 11 000 years. Following identification of landforms with high archaeological potential on a lidar Digital Terrain Model on both the modern shoreline and palaeoshorelines, we surveyed 16 locations, discovering 11 archaeological sites. At three locations associated with palaeoshorelines above modern sea level there are Early and Mid-Holocene components with basal ages dating between 11 000 and 9500 cal BP. These are rich with lithic artefacts, including microblades and bifaces (Figure 4). From a single 0.35 × 0.35m shovel test at one site, we recovered nearly 250 lithic flakes and flake tools (including microblades) in only 0.20 vertical metres. The striking density of archaeological material at these sites indicates that the Moore Islands were consistently used by large groups of people. These data provide an exciting window into the lifeways of outer coast inhabitants during the poorly known Early Holocene. Furthermore, while these sites are not the earliest documented on the Northwest Coast (see Fedje et al. Reference Fedje, Mackie, Lacourse and McLaren2011; Braje et al. Reference Braje2020), we have identified tantalising evidence for even older but as-yet undated archaeological components, at elevations that our RSL reconstruction suggests could be several thousand years earlier.

Figure 4. Johnston Reece, a member of the Gitnuganaks lineage, holds a 10 500 year-old biface fragment (photograph by J. Earnshaw).

Additionally, there is a rich suite of archaeological sites from the Middle and Late Holocene, including camps and small villages, stone-walled fish traps, petroglyphs and culturally modified trees (Figure 5). Many of these sites have evidence for millennia-long occupation. Such evidence includes artefacts and faunal remains that will further our understanding of the islands’ long-term occupation, and place these outlying habitations within the broader settlement system in ancestral Ts'msyen territories, which would have been more widely connected to the mainland shores and even people living in the interior.

Figure 5. A village site with both ancient and recent remains. Cleared canoe runs are highlighted in blue (photograph by B. Letham).

Bridging the Indigenous past and present

On the edge of the archipelago, associated with a sheltered anchorage on what is otherwise one of the most exposed of the Moore Islands, our Gitga'at collaborators guided us to the remains of an otherwise unrecorded ancient village site. Some Elders speculate/assert that this village is the Laxnuganaks—one of the village sites from where the Ts'msyen House Group derives its origins. While buried shell-midden deposits at this location indicate human occupation dating to at least 4000 years ago, these deposits are entangled with roots of live spruce trees that have been cut by Indigenous peoples for kindling and sap collection over the last century. The beach is marked with cleared rows within the cobbles and boulders that formed runways to drag canoes up to the village. Yet within these ancient rock clearings are strewn artefacts left behind by Ts'msyen families living here over the past 200 years: clay pipe stems, knapped glass and a gun flint (Figure 6). Eroding from the midden are bones of Rhinoceros auklets; the area today is known to have been an important harvesting location for auklets and other sea birds.

Figure 6. Examples of artefacts from the deep (red highlight, 10 500–9500 BP) and more recent (yellow highlight, 100–200 years ago) past: top left) biface reduction flakes; top right) microblades; bottom left) glass fragments (including knapped glass) and a clay pipe stem; bottom right) gun flint for a rifle (scales in cm; photographs by A. Dyck).

Locations like this, where ancient archaeological remains are associated with more recent occupation at areas known as origin places in Indigenous oral histories, and which figure prominently in the memories and cultural consciousness of Indigenous communities, are testament to the power of Indigenous connections to place and the role of place-making in structuring history (e.g. Lepofsky et al. Reference Lepofsky2017). Our archaeological research around Laxnuganaks allows us to continue exploring the bridges between past and present at these important locations.

Acknowledgements

We thank Simone Reece, Chris Picard, Donald Reece, Marven Robinson, Bruce Reece, Rosie Child, Doug Neasloss, Vern Brown, Dana Lepofsky, Rasha Elendari, Kim-Ly Thompson, Natalie Ban, Hayden Keating, Becky Wigen, Angela Dyck, Chris Hebda, Duncan McLaren and an anonymous reviewer for their support, for field and lab assistance, or for expert guidance with the project or with this article. We also thank the Hakai Institute for providing lidar data for the project.

Funding statement

The Moore Islands Project has been funded by a National Geographic Society Early Career Grant, a Wenner-Gren Post-PhD Field Work Grant, SSHRC Insight Development Grant #430-2019-01029, and in-kind contributions from the Gitga'at Nation. Bryn Letham is supported by a Banting Postdoctoral Fellowship and a MEOPAR Postdoctoral Fellowship.