Scientific Classification

Domain: Eukaryota

Kingdom: Plantae

Phylum: Spermatophyta

Subphylum: Angiospermae

Class: Dicotyledonae

Order: Gentianales

Family: Apocynaceae

Subfamily: Asclepiadoideae

Tribe: Asclepiadeae

Subtribe: Tylophorinae

Genus: Vincetoxicum Wolf

Species 1: nigrum (L.) Moench

Synonyms: Cynanchum louiseae Kartesz & Gandhi, Cynanchum nigrum (L.) Pers.

EPPO Code: CYKNI

Species 2: rossicum (Kleopow) Barbarich

Synonyms: Cynanchum rossicum Kleopow, Cynanchum rossicum (Kleopow) Borhidi, Vincetoxicum officinale var. rossicum (Kleopow) Grodz.

EPPO Code: VNCRO

Name and Taxonomy

Vincetoxicum comes from the Latin vinco (to conquer or subdue) + toxicum (poison), for the supposed use of these plants as an antidote for poison (DiTommaso et al. Reference DiTommaso, Lawlor and Darbyshire2005b). The specific epithet rossicum is a Latinized reference to the presumed origin of V. rossicum in Russia, whereas nigrum is Latin for “black” in reference to the flower color of V. nigrum. The identities of North American specimens of V. nigrum and V. rossicum were confirmed by Gaina Konechnaya and Nikolai Tsvelev, Institute of Botany, Russian Academy of Sciences, St Petersburg, Russia (personal communication). In addition to the two invasive Vincetoxicum species, a third species, Vincetoxicum hirundinaria Medik. [syn.: Cynanchum vincetoxicum (L.) Pers., Vincetoxicum officinale Moench], occupies a large native range in Eurasia but appears only to be a rare garden escape elsewhere, not showing invasive tendencies like V. rossicum and V. nigrum. Some workers have considered V. rossicum to be a dark-flowered form of the V. hirundinaria species complex (Gleason and Cronquist Reference Gleason and Cronquist1991; Lauvanger and Borgen Reference Lauvanger and Borgen1998) as hybrids between the two are known (Markgraf Reference Markgraf1971).

The common name pale swallowwort (or the more widely used hyphenated form “pale swallow-wort,” both used in the United States) for V. rossicum may be confusing because the pink or maroon flowers of V. rossicum are paler than the dark purple flowers of V. nigrum, but darker than the cream-colored flowers of V. hirundinaria (DiTommaso et al. Reference DiTommaso, Lawlor and Darbyshire2005b). Alternate common names for V. rossicum include European swallowwort (for its region of origin), dog-strangling vine (for its ability to form dense mats, Canada), dompte-venin de Russie (Canada), and russesvalerot (Norway). Common names for V. nigrum include black swallowwort (or black swallow-wort, United States), Louise’s swallowwort (based on one of its synonyms), black dog-strangling vine (Canada), and dompte-venin noir (Canada). In addition to white swallowwort, common names for V. hirundinaria include German ipecac, poison-rope swallowwort (Canada), white dog-strangling vine (Canada), and common vincetoxicum (Belgium) (references in Global Biodiversity Information Facility 2021, 2022a, 2022b).

The genus Vincetoxicum N.M. Wolf (1776) is placed within the subtribe Tylophorinae in the tribe Asclepiadeae in the subfamily Asclepiadoideae in the family Apocynaceae. The incorporation of the former family Asclepiadaceae into the Apocynaceae was required to make the Apocynaceae monophyletic (Endress and Bruyns Reference Endress and Bruyns2000). The family Asclepiadaceae was not reduced to a tribe or subfamily, as erroneously reported (DiTommaso et al. Reference DiTommaso, Lawlor and Darbyshire2005b). Instead, the five subfamilies in the revised family Apocynaceae include three subfamilies (Periplocoideae, Secamonoideae, and Asclepiadoideae) that were formerly included in the Asclepiadaceae and two subfamilies (Rauvolfioideae and Apocynoideae) that were already present in the Apocynaceae (Endress et al. Reference Endress, Liede-Schumann and Meve2007; Endress and Bruyns Reference Endress and Bruyns2000). Within the Asclepiadoideae (tribe Asclepiadeae), the subtribe Tylophorinae is closely related to the subtribe Cynanchinae, which contains the genus Cynanchum L. (Fishbein et al. Reference Fishbein, Livshultz, Straub, Simões, Boutte, McDonnell and Foote2018). The relationship between Vincetoxicum and Cynanchum has historically elicited controversy (DiTommaso et al. Reference DiTommaso, Lawlor and Darbyshire2005b; Liede Reference Liede1996), but it is now clear that these two genera should be separated (Endress et al. Reference Endress, Liede-Schumann and Meve2007, Reference Endress, Liede-Schumann and Meve2014).

The subtribe Tylophorinae initially included several genera (Endress et al. Reference Endress, Liede-Schumann and Meve2007; Liede et al. Reference Liede, Täuber and Schneidt2002), most of which were subsequently merged with Vincetoxicum (Endress et al. Reference Endress, Liede-Schumann and Meve2014; Liede-Schumann and Meve Reference Liede-Schumann and Meve2018). The combined group, Vincetoxicum sensu lato, contains at least 140 species native to Africa, Asia, and Europe (Liede-Schumann et al. Reference Liede-Schumann, Khanum, Mumtaz, Gherghel and Pahlevani2016; Liede-Schumann and Meve Reference Liede-Schumann and Meve2018). Over evolutionary time, the species V. rossicum, V. nigrum, and V. hirundinaria emerged from a clade (Vincetoxicum sensu stricto) that expanded northwest along the Asian mountain chains to Europe (Liede-Schumann et al. Reference Liede-Schumann, Khanum, Mumtaz, Gherghel and Pahlevani2016).

The duplicate genus Vincetoxicum T. Walter (1788) (Bullock Reference Bullock1967) was erected for North American species, resulting in several illegitimate synonyms under the name Vincetoxicum. These species are properly placed in the genera Matelea Aubl. and Gonolobus Michx. within the subtribe Gonolobinae (Endress et al. Reference Endress, Liede-Schumann and Meve2014; USDA-NRCS 2021).

Description

Unless otherwise noted, the following information is drawn from the descriptions of North American V. rossicum and V. nigrum presented by DiTommaso et al. (Reference DiTommaso, Lawlor and Darbyshire2005b). These species are perennial herbs or small vines (Figure 1). Although not rhizomatous (Averill et al. Reference Averill, DiTommaso, Mohler and Milbrath2011), they have short, horizontal, semi-woody rootstalks and slightly fleshy roots (Figure 1). Root-to-shoot ratios are often high, particularly in V. rossicum (Milbrath Reference Milbrath2008). Stems are usually 60- to 200-cm long in V. rossicum and 40- to 200-cm long in V. nigrum, but occasionally longer (particularly when climbing up shrubs). Stems are pubescent with the hairs in longitudinal bands (especially in V. rossicum, which also has denser hairs on peduncles and pedicels). Leaves are largest in the middle of the stem, opposite, entire-margined, and pubescent on margins and major veins of the lower surface. Leaves of V. rossicum are ovate to elliptic, acute at the tip, and typically 7 to 12 by 5 to 7 cm with 5- to 20-mm petioles. Leaf bases are often truncate or slightly cuneate. Leaves of V. nigrum are oblong to ovate and typically 5 to 12 by 2 to 6.5 cm with 10- to 15-mm petioles. Leaf bases are often emarginate or cordate in V. nigrum.

Figure 1. (A) Seedlings and small juveniles of Vincetoxicum rossicum. (B) Individual Vincetoxicum rossicum plant. (C) Individual Vincetoxicum nigrum plant. (D) Cross-section of a Vincetoxicum rossicum root system. (E) Two connected rootstocks of Vincetoxicum nigrum (southeastern New York, USA). (Photo credits: (A–C and E) Jeromy Biazzo; (D) Scott Morris.)

Reproductive traits show much more interspecific variation than vegetative traits. Vincetoxicum rossicum flower buds are ovoid to conoidal with pointed apices, whereas V. nigrum flower buds are globose with rounded apices. Petals are twisted before opening in V. rossicum. Flowers are produced in umbelliform cymes in leaf axils, with 5 to 20 flowers in V. rossicum and 4 to 10 flowers in V. nigrum. Peduncles of the inflorescences are pubescent and longer (1.5 to 4.5 cm) in V. rossicum than in V. nigrum (0.5 to 1.5 cm). Flowers are five-parted with diameters of 5 to 7 mm (V. rossicum) or 5 to 8 mm (V. nigrum). Calyx segments (1 to 1.5 mm) are more straplike in V. rossicum and closer to triangular in V. nigrum. Vincetoxicum rossicum and V. nigrum are usually easy to distinguish by corolla characteristics, especially color: pink, red-brown, or maroon in V. rossicum and dark purple to blackish in V. nigrum (Figure 2A and C). However, white-flowered individuals of V. rossicum are known from Ontario, Canada, and New York State, USA (S Darbyshire and L Milbrath, personal observation; Figure 2A). Vincetoxicum rossicum petals (3- to 5-mm long) are ovate-lanceolate to lanceolate, hairless, and only slightly fleshy. In contrast, V. nigrum petals (1.5- to 3-mm long) are ovate to deltoid, finely hairy on the inner surface, and fleshy. Both species have fleshy coronas that typically share the corolla color. The V. rossicum corona is more deeply lobed. The gynostegium (anthers fused with the stigmatic disk) is pale yellow to pale green. Fruits are smooth follicles, 4- to 7-cm long in V. rossicum and 4- to 8-cm long in V. nigrum. Vincetoxicum rossicum follicles are slender, and V. nigrum follicles may be slender or plump (Figure 2B and D). Two follicles may be formed per flower (more frequently in V. rossicum). The seeds of V. rossicum (4 to 6.5 by 2.4 to 3.1 mm) are light to dark brown, obovoid to oblong, and convex on one side. Vincetoxicum nigrum seeds are larger (6 to 8 by 3 to 4.7 mm), dark brown, ovoid to obovoid, and flattened on both sides. Seeds have membranous marginal wings (wider in V. rossicum, up to 0.25 mm) and a large coma (2 to 3 cm). Seedlings of V. rossicum and V. nigrum are not easily distinguishable. The cotyledons and first leaves are ovate to elliptic and may have slightly pointed apices. Cotyledons are not typically visible (Figure 3). Because V. nigrum has larger seeds, V. nigrum seedlings are initially larger than V. rossicum seedlings (Milbrath Reference Milbrath2008).

Figure 2. (A) Vincetoxicum rossicum typically has pink, red-brown, or maroon flowers but also occurs in a white-flowered mutant form. (B) Vincetoxicum rossicum follicles are slender. (C) Vincetoxicum nigrum flowers are dark purple to blackish. (D) Vincetoxicum nigrum follicles may be slender or plump. (Photo credits: (A) Stephen Darbyshire; (B) Larissa Smith; (C and D) Jeromy Biazzo.)

Figure 3. Cotyledons of Vincetoxicum nigrum (and V. rossicum) do not typically emerge from the seed. At the right, a seed has been manually dissected. (Photo credit: Scott Morris.)

Vincetoxicum hirundinaria, a widespread species in Eurasia and possible occasional garden escape in North America, is most easily distinguished from V. rossicum and V. nigrum by its white, yellow, or greenish-white flower petals (except in the case of white-flowered V. rossicum mutants). Petals may or may not be hairy (Cullen et al. Reference Cullen, Knees and Cubey2011). Otherwise, V. hirundinaria appears similar to V. rossicum and V. nigrum, according to descriptions from Eurasia (Bojnanský and Fargašová Reference Bojnanský and Fargašová2007; Cullen et al. Reference Cullen, Knees and Cubey2011). Disagreements arise as to what constitutes a species or subspecies within the highly variable and widespread V. hirundinaria complex (Markgraf Reference Markgraf1972; Pobedimova Reference Pobedimova1952, Reference Pobedimova1978). As noted earlier (see “Name and Taxonomy”), V. rossicum has been included under the name V. hirundinaria (Gleason and Cronquist Reference Gleason and Cronquist1991; Lauvanger and Borgen Reference Lauvanger and Borgen1998). These taxonomic disagreements, combined with the white-flowered mutant form of V. rossicum, have likely contributed to erroneous reports of invasive V. hirundinaria in North America.

In North America, V. rossicum is diploid (2n = 2x = 22) and V. nigrum is tetraploid (2n = 4x = 44) (Bon et al. Reference Bon, Guermache, Rodier-Goud, Bakry, Bourge, Dolgovskaya, Volkovitsh, Sforza, Darbyshire and Milbrath2013); hybridization between the two species in North America is therefore considered unlikely. Vincetoxicum rossicum is also reported to be diploid in its native range (Russia), and V. nigrum to be tetraploid in its native range (southern France; Bon et al. Reference Bon, Guermache, Rodier-Goud, Bakry, Bourge, Dolgovskaya, Volkovitsh, Sforza, Darbyshire and Milbrath2013). However, V. nigrum has been reported to be diploid in Spain (references in DiTommaso et al. Reference DiTommaso, Lawlor and Darbyshire2005b). Vincetoxicum hirundinaria is diploid in its native range (Guermache et al. Reference Guermache, Bon, Jones and Milbrath2010). Genome sizes (mean 2C values ± STD) are reported to be 0.71 ± 0.02 pg for V. rossicum and 1.44 ± 0.03 pg for V. nigrum and appear to be similar between the native and introduced ranges (Bon et al. Reference Bon, Guermache, Rodier-Goud, Bakry, Bourge, Dolgovskaya, Volkovitsh, Sforza, Darbyshire and Milbrath2013). For V. rossicum and V. nigrum, genetic diversity is much lower in North America than in Europe (Bon et al. Reference Bon, Jeanneau, Jones, Milbrath, Sforza and Dolgovskaya2010; Douglass Reference Douglass2008), with the majority of North American populations apparently derived from one major European genotype per species (Bon et al. Reference Bon, Jeanneau, Jones, Milbrath, Sforza and Dolgovskaya2010). The source population for V. rossicum has been identified in Ukraine (Sforza et al. Reference Sforza, Augé, Jeanneau, Poidatz, Reznik, Simonot, Volkovitch and Milbrath2013a).

Importance

Vincetoxicum rossicum and V. nigrum are listed as noxious or prohibited weeds across much of the northeastern United States and eastern Canada (Supplementary Table S1). In North America and other invaded regions, such as Norway, these weeds threaten both unmanaged and managed ecosystems by outcompeting resident and desirable species (Bjureke Reference Bjureke2007; DiTommaso et al. Reference DiTommaso, Lawlor and Darbyshire2005b). They can grow in dense near-monospecific stands (Figure 4), altering ecosystem structure and function (DiTommaso et al. Reference DiTommaso, Lawlor and Darbyshire2005b; Douglass et al. Reference Douglass, Weston and DiTommaso2009). In such stands, stem densities are often 100 to 200 stems m−2 (>10-cm tall) and >1,400 stems m−2 (<10 cm) under high light (Milbrath et al. Reference Milbrath, Davis and Biazzo2018; Sheeley Reference Sheeley1992; Smith et al. Reference Smith, DiTommaso, Lehmann and Greipsson2006). In southern Ontario, Livingstone et al. (Reference Livingstone, Isaac and Cadotte2020a) found that invasion by V. rossicum significantly decreased plant community diversity. Invasion also increased total productivity; however, productivity tended to increase with the richness of the remaining resident community. Changes to species diversity are associated with changes to functional diversity (Livingstone et al. Reference Livingstone, Isaac and Cadotte2020a; Sodhi et al. Reference Sodhi, Livingstone, Carboni and Cadotte2019). Vincetoxicum rossicum reduces plant community diversity by limiting resource availability to all residents and severely restricting resource availability to residents in particular niches (Sodhi et al. Reference Sodhi, Livingstone, Carboni and Cadotte2019). That is, V. rossicum acts as an ecological filter, causing the nonrandom exclusion of some resident species (Sodhi et al. Reference Sodhi, Livingstone, Carboni and Cadotte2019). In addition to competing with resident species, V. rossicum may drive plant diversity loss through ecosystem modification (such as changes to soil characteristics; Carboni et al. Reference Carboni, Livingstone, Isaac and Cadotte2021). Vincetoxicum invasion is particularly concerning in rare habitats such as alvar ecosystems (Kricsfalusy and Miller Reference Kricsfalusy and Miller2010; O’Brien et al. Reference O’Brien, Holzworth, Otis, Belding and Robert2010) and not necessarily prevented by high initial biodiversity in the invaded community (Kricsfalusy and Miller Reference Kricsfalusy and Miller2010). Dibble et al. (Reference Dibble, White and Lebow2007) included V. nigrum in the complex of introduced species that may enhance fire risks in forests and overgrown fields of the northeastern United States.

Figure 4. (A) Field infestation of Vincetoxicum rossicum in New York, USA. (B) Forest infestation of Vincetoxicum rossicum in New York, USA. (C) Emerging shoots of Vincetoxicum nigrum in New York, USA. (Photo credits: (A) Jeromy Biazzo; (B and C) Kristine Averill.)

In addition to reshaping resident plant communities, Vincetoxicum invasion effects changes at other trophic levels. For example, V. rossicum can have significant impacts on soil fungal and bacterial communities (Bongard et al. Reference Bongard, Butler and Fulthorpe2013a; Bugiel et al. Reference Bugiel, Livingstone, Isaac, Fulthorpe and Martin2018; Greipsson and DiTommaso Reference Greipsson and DiTommaso2006). Malloch et al. (Reference Malloch, Tatsumi, Seibold, Cadotte and MacIvor2020) reported interactive effects of V. rossicum invasion and urbanization on microarthropod communities in leaf litter. Ernst and Cappuccino (Reference Ernst and Cappuccino2005) reported reduced arthropod communities on invasive V. rossicum compared with native old-field plants and mixed grass communities, accounting for both stem- and ground-dwelling species of all feeding guilds. This finding is consistent with reports that V. rossicum and V. nigrum are seldom damaged by phytophagous arthropods in eastern North America (Carpenter and Cappuccino Reference Carpenter and Cappuccino2005; Milbrath Reference Milbrath2010). Livingstone (Reference Livingstone2018) suggested that pollinator richness and abundance are lower in ecosystems highly invaded by V. rossicum. Because invasive Vincetoxicum harbor very few arthropods, they are unlikely to be a reservoir for arthropod crop pests. Vincetoxicum species may be more problematic as reservoirs for fungal pathogens. For example, research in northern and southern Europe has demonstrated that V. nigrum and V. hirundinaria can serve as alternate hosts for Cronartium flaccidum (Alb. & Schwein.) G. Winter, a rust fungus that causes disease in pines (Pinus spp.) (Bon and Guermache Reference Bon and Guermache2012; Kaitera et al. Reference Kaitera, Hiltunen and Samils2012, Reference Kaitera, Hiltunen, Kauppila and Hantula2017). In an outdoor experiment in Switzerland, leaves of V. rossicum and V. nigrum became infected with the fungal pathogens Ascochyta sp. and Cercospora sp. (Ascomycota), respectively (Weed et al. Reference Weed, Gassmann and Casagrande2011a). There is some evidence that the fungal communities associated with V. rossicum in North America could have positive effects on V. rossicum and negative effects on native plants (Day et al. Reference Day, Dunfield and Antunes2016; Dickinson et al. Reference Dickinson, Bourchier, Fulthorpe, Shen, Jones and Smith2021).

Vincetoxicum infestations may harm monarch butterfly (Danaus plexippus L.) populations by acting as an oviposition sink or by competing with milkweeds. If D. plexippus females oviposit on these plants rather than on milkweeds (Asclepias spp.), the larvae do not survive (Haribal and Renwick Reference Haribal and Renwick1998). This mortality risk is reduced by the preference of D. plexippus females for Asclepias over Vincetoxicum hosts. Some experiments have shown a very strong preference for Asclepias, although this outcome may have resulted from using laboratory-reared insects (Alred et al. Reference Alred, Haan, Landis and Szűcs2022a; DiTommaso and Losey Reference DiTommaso and Losey2003; Mattila and Otis Reference Mattila and Otis2003). Other work has shown some to substantial oviposition on Vincetoxicum plants under field conditions (Alred et al. Reference Alred, Haan, Landis and Szűcs2022a; Casagrande and Dacey Reference Casagrande and Dacey2007; Milbrath Reference Milbrath2010). If oviposition on Vincetoxicum occurs at a significant rate, this rate likely depends on the ratio of Vincetoxicum to Asclepias plants at a landscape level. It has been suggested that Vincetoxicum species may do more damage to D. plexippus populations by outcompeting desirable Asclepias hosts than by serving as oviposition sinks (DiTommaso et al. Reference DiTommaso, Lawlor and Darbyshire2005b; DiTommaso and Losey Reference DiTommaso and Losey2003). As the two genera are related (in the same tribe, Asclepiadeae), and Vincetoxicum species tend to suppress native vegetation, the competitive effects of Vincetoxicum species on Asclepias species are likely to be substantial; however, these effects are difficult to measure in natural systems (MacIvor et al. Reference MacIvor, Roberto, Sodhi, Onuferko and Cadotte2017). Jackson and Amatangelo (Reference Jackson and Amatangelo2021) suggested that V. rossicum is a poor competitor against common milkweed (Asclepias syriaca L.) on an individual basis at low densities but gains a competitive advantage as its density increases (Allee effect). Because the effects of Vincetoxicum invasion on D. plexippus oviposition and Asclepias survival and performance appear to be context dependent, it is not entirely clear how the negative effects of Vincetoxicum species on D. plexippus compare with other threats to this species (Malcolm Reference Malcolm2018; Wilcox et al. Reference Wilcox, Flockhart, Newman and Norris2019).

Vincetoxicum rossicum and V. nigrum can be problematic in North American agricultural systems with low disturbance. For example, these species have been reported in no-till field crops and Christmas tree farms (DiTommaso et al. Reference DiTommaso, Lawlor and Darbyshire2005b; Douglass et al. Reference Douglass, Weston and DiTommaso2009; Lawlor Reference Lawlor2003). Horse pasture owners have also reported severe infestations, sometimes leading to abandonment of the pasture (DiTommaso et al. Reference DiTommaso, Lawlor and Darbyshire2005b; Douglass et al. Reference Douglass, Weston and DiTommaso2009). In addition to competing with desirable species, Vincetoxicum plants may overgrow and thereby reduce the effectiveness of electric fences (Tewksbury et al. Reference Tewksbury, Casagrande and Gassmann2002). These species are thought to be toxic to mammals (DiTommaso et al. Reference DiTommaso, Lawlor and Darbyshire2005b; Hess Reference Hess2014; Weston et al. Reference Weston, Barney and DiTommaso2005), although grazing by cattle and sheep has been reported (DiTommaso et al. Reference DiTommaso, Lawlor and Darbyshire2005b; Tewksbury et al. Reference Tewksbury, Casagrande and Gassmann2002). Because established Vincetoxicum populations are difficult to eradicate, severe infestations can decrease the land value of fields and pastures (AD, personal observation). Vincetoxicum infestations may also interfere with land use goals in areas managed for nonagricultural purposes. For example, vines of V. rossicum have been observed to weigh down small trees planted at restoration sites in Ontario (Christensen Reference Christensen1998). The number of breeding grassland birds decreased with increasing V. rossicum cover in a habitat managed for grassland birds in New York (DiTommaso et al. Reference DiTommaso, Lawlor and Darbyshire2005b). The foliage of Vincetoxicum species is typically unpalatable to herbivores native to North America, such as white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus Zimmermann) (Lawlor Reference Lawlor2003). Most visitors to an urban park felt that a V. rossicum infestation detracted from the aesthetic value of the park (Livingstone et al. Reference Livingstone, Cadotte and Isaac2018). In its introduced North American range, V. rossicum colonizes a variety of habitats within the urban matrix, ranging from lawns and gardens to remnants of natural ecosystems (Cadotte et al. Reference Cadotte, Yasui, Livingstone and MacIvor2017; Potgieter and Cadotte Reference Potgieter and Cadotte2020). Control of this aggressive weed is a major issue in Toronto, Ontario (Potgieter and Cadotte Reference Potgieter and Cadotte2020; Potgieter et al. Reference Potgieter, Shrestha and Cadotte2021).

Vincetoxicum plants offer some benefits. For example, they have traditionally been used for medicinal purposes in Europe. Vincetoxicum hirundinaria has been administered as an emetic, diuretic, or anti-tumor agent (Duke Reference Duke2002, p. 325; Tanner and Wiegrebe Reference Tanner and Wiegrebe1993; Uphof 1968, p. 168). Extracts from Vincetoxicum species, including V. hirundinaria, exhibit antifeedant activity against the phytophagous larvae of the Colorado potato beetle (Leptinotarsa decemlineata Say) and Egyptian cotton leafworm (Spodoptera littoralis Boisduval) (Guzel et al. Reference Guzel, Pavela and Kokdil2015; Pavela Reference Pavela2010). Despite these possible uses, Vincetoxicum invasion should generally be considered deleterious.

Distribution

Vincetoxicum rossicum is native to Ukraine and southwestern Russia (DiTommaso et al. Reference DiTommaso, Lawlor and Darbyshire2005b; Figure 5A). This species has been anthropogenically introduced to other areas of Europe (see “Invasion History”; Markgraf Reference Markgraf1971). It is naturalized in Norway (Bjureke Reference Bjureke2007; Lauvanger and Borgen Reference Lauvanger and Borgen1998). Introductions to Belgium, Denmark, Finland, Germany, the Netherlands, and Sweden have also been reported (Gassmann 2022b; Global Biodiversity Information Facility 2022b). In North America, V. rossicum has been reported in the U.S. states of Connecticut, Indiana, Massachusetts, Michigan, Missouri, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, and Pennsylvania (Gassmann 2022b; USDA-NRCS 2021). It has been reported in the Canadian provinces of British Columbia (but not persisting), Ontario, and Quebec (Gassmann 2022b; USDA-NRCS 2021). There has been one report of V. rossicum in Nigeria (Global Biodiversity Information Facility 2022b).

Vincetoxicum nigrum is native to southwestern Europe, including Portugal, Spain, France, and Italy (DiTommaso et al. Reference DiTommaso, Lawlor and Darbyshire2005b; Figure 5B). Naturalized in the Netherlands (Markgraf Reference Markgraf1972), this species is also present in Belgium (Gassmann 2022a; Global Biodiversity Information Facility 2022a). There are occasional reports from Albania, the Bahamas, Bulgaria, Colombia, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Germany, Iran, Mexico, Norway, Russia, Sweden, Tanzania, Turkey, and Ukraine (Global Biodiversity Information Facility 2022a; Petrova Reference Petrova2010). In North America, V. nigrum has been reported in the U.S. states of California, Connecticut, Illinois, Indiana, Kansas, Kentucky, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Vermont, and Wisconsin (Gassmann 2022a; USDA-NRCS 2021). The single population reported in California has apparently died out (Milbrath and Biazzo Reference Milbrath and Biazzo2016), so the current distribution in the United States likely extends no farther west than Kansas and Nebraska. Vincetoxicum nigrum is present in the Canadian provinces of Ontario and Quebec (Gassmann 2022a; USDA-NRCS 2021).

Vincetoxicum hirundinaria is widespread in its native Eurasian range but not strongly invasive like V. rossicum and V. nigrum. Records of V. hirundinaria in North America are often misidentifications: many of these specimens are correctly identified as V. rossicum. The misidentifications reflect confusion over nomenclature or potentially the white-flowered mutant of V. rossicum (see “Name and Taxonomy”; “Description”). Although V. hirundinaria has been reported in New York and Michigan, USA, and Ontario, Canada (USDA-NRCS 2021), it is likely that most of these reports represent garden specimens with the exception of a 1904 collection involving a garden escape (Pringle Reference Pringle1973; Sheeley and Raynal Reference Sheeley and Raynal1996).

Habitat

According to the Köppen-Geiger classification, V. rossicum most frequently inhabits Dfa (cold, no dry season, hot summer) and Dfb (cold, no dry season, warm summer) climate types (Supplementary Figure S1A). Vincetoxicum nigrum most frequently inhabits BSk (arid, steppe, cold), Csa (temperate, dry summer, hot summer), Csb (temperate, dry summer, warm summer), Cfa (temperate, no dry season, hot summer), Cfb (temperate, no dry season, warm summer), Dfa, and Dfb climate types (Supplementary Figure S1B).

In their introduced North American ranges, V. rossicum and V. nigrum behave as generalists with respect to climate and habitat type. Kricsfalusy and Miller (Reference Kricsfalusy and Miller2010) characterized V. rossicum’s North American range as similar in temperature but wetter than its native range in Ukraine and Russia. In both ranges, V. rossicum tends to inhabit semi-open scrub or woodland habitats on calcareous soils (Kricsfalusy and Miller Reference Kricsfalusy and Miller2010). However, V. rossicum populations in North America occupy a wider variety of light environments and soil types (Kricsfalusy and Miller Reference Kricsfalusy and Miller2010). Vincetoxicum nigrum may inhabit cooler and wetter habitats in North America than in southwestern Europe (DiTommaso et al. Reference DiTommaso, Lawlor and Darbyshire2005b). In both species, cold temperatures are tolerated well but typically associated with phenological delays (see “Growth and Development: Stress Tolerance”; “Growth and Development: Phenology”). Vincetoxicum species tolerate a wide range of moisture levels, but permanently waterlogged soils are not suitable (see “Growth and Development: Stress Tolerance”). These species primarily inhabit upland habitats, including exposed habitats with highly variable water availability (DiTommaso et al. Reference DiTommaso, Lawlor and Darbyshire2005b). Based on a survey of V. rossicum populations in Ontario, Dickinson et al. (Reference Dickinson, Bourchier, Fulthorpe, Shen, Jones and Smith2021) reported that aboveground biomass production was positively correlated with precipitation but not strongly associated with habitat type or abiotic soil variables.

Vincetoxicum rossicum is often found on calcareous soils, including shallow soils over limestone bedrock as well as deeper soils (DiTommaso et al. Reference DiTommaso, Lawlor and Darbyshire2005b; Kricsfalusy and Miller Reference Kricsfalusy and Miller2010; Weston et al. Reference Weston, Barney and DiTommaso2005). In New York, Douglass (Reference Douglass2008) reported that soils colonized by V. rossicum (pH 5.2 to 7.6) had higher levels of calcium (Ca) and aluminum (Al) than soils colonized by V. nigrum (pH 5.2 to 7.2). Soils colonized by V. rossicum had a slightly higher average pH compared with V. nigrum (6.8 relative to 6.0). In a study combining soil measurements with data retrieved from the Soil Survey Geographic Database, Magidow et al. (Reference Magidow, DiTommaso, Westbrook, Kwok, Ketterings and Milbrath2022) found that V. rossicum colonized soils with higher mean pH than soils colonized by V. nigrum in the northeastern United States and southeastern Canada. However, soil characteristics (pH, fertility, texture, and taxonomy) varied widely across the ranges of both species (Magidow et al. Reference Magidow, DiTommaso, Westbrook, Kwok, Ketterings and Milbrath2022). Common garden and growth chamber experiments have provided only weak support for the hypothesis that V. rossicum and V. nigrum perform best on different soils (Magidow et al. Reference Magidow, DiTommaso, Ketterings, Mohler and Milbrath2013). Soil factors do not appear to limit range expansion in V. rossicum (Sanderson et al. Reference Sanderson, Day and Antunes2015).

At smaller spatial scales, light and disturbance are important influences on species distributions. Vincetoxicum rossicum and V. nigrum both inhabit high-light environments, including fields, habitat edges, and waste areas (DiTommaso et al. Reference DiTommaso, Lawlor and Darbyshire2005b). Vincetoxicum rossicum is also frequently found in forest understories, whereas V. nigrum is less common in understory habitats (Alred et al. Reference Alred, Hufbauer and Szűcs2022b; Averill et al. Reference Averill, DiTommaso, Mohler and Milbrath2011; Milbrath et al. Reference Milbrath, Davis and Biazzo2017), even though both species have the photosynthetic capacity to tolerate low light (Averill et al. Reference Averill, DiTommaso, Whitlow and Milbrath2016). Vincetoxicum nigrum often occupies shaded environments in its native European range (Averill et al. Reference Averill, DiTommaso, Mohler and Milbrath2011). In both species, light limitation can reduce establishment, growth, and reproductive potential (see “Growth and Development: Ecophysiology”). Vincetoxicum species are not problematic in highly disturbed habitats like tilled crop fields (DiTommaso et al. Reference DiTommaso, Lawlor and Darbyshire2005b). Vincetoxicum populations cannot survive under frequent, extreme disturbance because these perennials may remain vegetative for several years before flowering (see “Life-Form and Life History”). Averill et al. (Reference Averill, DiTommaso, Mohler and Milbrath2010) tested V. rossicum establishment and growth in two old fields under strong disturbance treatments (herbicide or herbicide plus tillage) or weak disturbance treatments (mowing or no disturbance). At one site, establishment was increased under weak disturbance relative to strong disturbance. However, total biomass at both sites was increased under strong disturbance relative to weak disturbance. These data suggest a possible trade-off between initial establishment and subsequent growth, in addition to illustrating the effects of small-scale habitat characteristics on Vincetoxicum competitiveness within the introduced range.

Invasion History

Vincetoxicum nigrum, V. rossicum, and V. hirundinaria are all native to Europe, with the native distribution of V. hirundinaria also including parts of Asia and Africa (see “Distribution”; Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew 2021). In addition, V. nigrum and V. rossicum have invaded areas of Europe to which they are not native (see “Distribution”). For example, a population of V. nigrum (native to southwestern Europe) was found to be established in Bulgaria in 2009 (Petrova Reference Petrova2010). It is naturalized in the Netherlands and is considered a garden escape in Belgium (Global Biodiversity Information Facility 2022a; Markgraf Reference Markgraf1972; Ronse Reference Ronse2013). Markgraf (Reference Markgraf1971) noted that V. rossicum has been grown in gardens in Central and Western Europe since at least the 1800s, with some escapes reported. Vincetoxicum rossicum was anthropogenically introduced to Norway before 1865, although misidentified as V. hirundinaria, and is now considered invasive there (Bjureke Reference Bjureke2007; Lauvanger and Borgen Reference Lauvanger and Borgen1998).

The early history of Vincetoxicum in North America is obscured by inconsistent nomenclature and the fact that escapes did not immediately lead to explosive population growth. Vincetoxicum nigrum appears to have been introduced first, with most early herbarium specimens (beginning in Massachusetts, USA, in 1854) collected in or near gardens (Sheeley and Raynal Reference Sheeley and Raynal1996). The fifth edition of Gray’s Manual of Botany (Gray Reference Gray1868, p. 399) described V. nigrum as “a weed escaping from gardens” around Cambridge, MA. It may have been brought into Ontario as early as 1861 from the Botanic Garden at Cambridge, MA (Pringle Reference Pringle1973). Early herbarium records and descriptions of V. rossicum (mistakenly labeled Cynanchum medium R. Br. in early years) (Sheeley and Raynal Reference Sheeley and Raynal1996) suggest a similar invasion pathway. These records include the Canadian provinces of British Columbia in 1885 (which did not persist) and Ontario in 1889, and New York, USA, in 1897 (Moore Reference Moore1959; Sheeley and Raynal Reference Sheeley and Raynal1996). Reports of V. rossicum in Canada and the northeastern United States remained sporadic until the second half of the 20th century (Sheeley and Raynal Reference Sheeley and Raynal1996). The third species, V. hirundinaria, has generated fewer records in North America. The seventh edition of Gray’s Manual of Botany (Gray Reference Gray, Robinson and Fernald1908, p. 667) reported that this species [as Cynanchum vincetoxicum (L.) Pers.] had escaped from cultivation in southern Ontario, although it apparently has not persisted (Pringle Reference Pringle1973). The earliest herbarium specimen found by Sheeley and Raynal (Reference Sheeley and Raynal1996) was collected in New York in 1916.

Following their initial introductions, V. rossicum and V. nigrum did not become major problems in North America for many decades. This long lag phase has been followed by a period of rapid expansion. Kricsfalusy and Miller (Reference Kricsfalusy and Miller2008) formalized these observations for V. rossicum in the Toronto, Ontario, area. They found that the lag phase lasted nearly a century and that V. rossicum invasion followed an exponential trajectory from 2000 to 2005. More qualitative observations of larger-scale trends indicate that V. rossicum and V. nigrum were well established in some areas (but not particularly common) by the mid-20th century (Sheeley and Raynal Reference Sheeley and Raynal1996). These species became increasingly prevalent in subsequent decades, especially at the end of the 20th century and in the 21st century (DiTommaso et al. Reference DiTommaso, Lawlor and Darbyshire2005b; Douglass et al. Reference Douglass, Weston and DiTommaso2009). Several factors may have contributed to increasing range and population expansion rates. Positive associations between population size and expansion rate (e.g., larger populations produce more seeds) should occur when resources are available and environmental conditions are suitable. During the lag phase, Vincetoxicum species may have increased their ability to compete for resources and thrive under North American environmental conditions. This process may have involved evolutionary changes to the genotypes introduced from Europe (Douglass et al. Reference Douglass, Weston and DiTommaso2009). Adaptive evolution could help explain the wide climatic ranges occupied by Vincetoxicum species in North America (see “Habitat”). Because V. rossicum and V. nigrum were already well established in North America by the time that their rapid expansion began attracting major concern, research and management efforts have focused on limiting environmental and economic injury rather than pursuing eradication, except in Minnesota, USA (Minnesota Department of Agriculture 2021).

Life-Form and Life History

Vincetoxicum species are herbaceous perennial vines that reproduce by seed (Figure 6). Based on North American studies, single-stemmed seedlings typically emerge in spring, although autumn germination can also occur from the seedbank (DiTommaso et al. Reference DiTommaso, Lawlor and Darbyshire2005b; Milbrath et al. Reference Milbrath, Davis and Biazzo2017). Survival rates for seedlings (and older plants) may be high, especially outside of heavily shaded forest habitats (Milbrath et al. Reference Milbrath, Davis and Biazzo2017). High survival rates may be facilitated by resource allocation strategies that initially emphasize resource acquisition and storage. Although it is possible for flowering and follicle production to occur in the first or second years under semi-natural conditions (Averill et al. Reference Averill, DiTommaso, Mohler and Milbrath2010; Magidow et al. Reference Magidow, DiTommaso, Ketterings, Mohler and Milbrath2013), flowering typically does not occur for several years (see “Reproduction: Population Dynamics”; Milbrath et al. Reference Milbrath, Davis and Biazzo2017). During the pre-flowering juvenile period, V. rossicum plants grow slowly and store resources belowground (Averill et al. Reference Averill, DiTommaso, Mohler and Milbrath2010; McKague and Cappuccino Reference McKague and Cappuccino2005; Milbrath et al. Reference Milbrath, Davis and Biazzo2017). Gradual resource accumulation may be particularly important in shaded or otherwise low-resource environments, but the long juvenile period is not unique to a particular habitat type (Averill et al. Reference Averill, DiTommaso, Mohler and Milbrath2010). In any competitive environment, V. rossicum may benefit from delaying reproduction until energy reserves are sufficient. Prolonged juvenile periods also occur in V. nigrum, although young V. nigrum plants are more likely to flower and produce follicles than young V. rossicum plants (Magidow et al. Reference Magidow, DiTommaso, Ketterings, Mohler and Milbrath2013; Milbrath Reference Milbrath2008; Milbrath et al. Reference Milbrath, Davis and Biazzo2017). The interspecific difference in time to flowering appears to be associated with increased root allocation in V. rossicum relative to V. nigrum (Milbrath et al. Reference Milbrath, Davis and Biazzo2017). Once a plant begins flowering, it may continue for many years. Individual plants are long-lived (life span unknown; Milbrath et al. Reference Milbrath, Davis and Biazzo2017), and populations may persist indefinitely (>70 yr; Sheeley and Raynal Reference Sheeley and Raynal1996).

Figure 6. (A) Seeds of Vincetoxicum nigrum (left) and Vincetoxicum rossicum (right). (B) Seedlings (with seed coats) and older vegetative juveniles of V. rossicum. (C) Vegetative juveniles of Vincetoxicum rossicum. (D) Individual Vincetoxicum rossicum plant with multiple stems. (E) Senesced Vincetoxicum rossicum stems and spring regrowth. (F) Follicle dehiscence in Vincetoxicum rossicum. (Photo credits: (A and D) Scott Morris; (B) Kristine Averill; (C and E) Jeromy Biazzo; (F) Larissa Smith.)

Each year, Vincetoxicum stems senesce in late summer or early autumn (DiTommaso et al. Reference DiTommaso, Lawlor and Darbyshire2005b). Belowground organs overwinter. In the next growing season, one to several new stems sprout from buds on the root crown (DiTommaso et al. Reference DiTommaso, Lawlor and Darbyshire2005b; Milbrath et al. Reference Milbrath, Davis and Biazzo2017). In productive environments, older plants produce more stems than young plants (Milbrath et al. Reference Milbrath, Davis and Biazzo2017). Averill et al. (Reference Averill, DiTommaso, Mohler and Milbrath2011) demonstrated this phenomenon in both V. rossicum and V. nigrum clumps (i.e., single genets or multiple genets in the case of polyembryony; see “Reproduction: Seed Production and Dispersal”). Stem numbers increased more quickly in old fields (−0.02 to 2.1 stems clump−1 yr−1 for V. rossicum and −0.01 to 4.6 stems clump−1 yr−1 for V. nigrum) than in forests (−0.01 to 0.8 stems clump−1 yr−1 for V. rossicum). Older plants may have up to 25 stems (Milbrath et al. Reference Milbrath, DiTommaso, Biazzo and Morris2016, Reference Milbrath, Davis and Biazzo2017). However, under high densities, individual plants may only possess a single stem (LRM, unpublished data). Increases in stem number can facilitate proportional increases in per-plant biomass or seed production (Averill et al. Reference Averill, DiTommaso, Mohler and Milbrath2011), or these trends can be decoupled (e.g., under disturbance; Milbrath et al. Reference Milbrath, DiTommaso, Biazzo and Morris2016). Depending on their length and the availability of supports, Vincetoxicum stems may be erect or scrambling, twining, or climbing (DiTommaso et al. Reference DiTommaso, Lawlor and Darbyshire2005b). In hedgerow and woodland-edge habitats, V. rossicum can reportedly climb to heights of 2 to 3 m (Cappuccino et al. Reference Cappuccino, Mackay and Eisner2002). The climbing habit aids seed dispersal and increases the competitive (i.e., shading) and physical effects of vines on support plants.

Invasive Vincetoxicum species are effective competitors and tolerant of interspecific competition. Their life cycles are relatively slow. They tolerate only moderate disturbance and stress. For these reasons, they are best classified as Competitors in the C-S-R (Competitor, Stress tolerator, Ruderal) framework (Averill et al. Reference Averill, DiTommaso, Mohler and Milbrath2010; Grime Reference Grime1977).

Dispersal and Establishment

Vincetoxicum rossicum and V. nigrum reproduce exclusively by producing seeds, which are primarily wind dispersed. Wind-dispersed seeds typically travel short to moderate distances. Cappuccino et al. (Reference Cappuccino, Mackay and Eisner2002) found that V. rossicum seeds traveled up to 18 m, with 50% of seeds traveling less than 2.5 m from the release point (release height: 1.5 m; windspeed: 11.2 km h−1). Seed weight was negatively associated with dispersal distance. Large seeds sometime achieved better germination and growth than small seeds; however, the relationships between seed weight and dispersibility or quality are weak enough that any trade-off between dispersibility and quality is probably unimportant at the local scale (Ladd and Cappuccino Reference Ladd and Cappuccino2005). Release height is a more important influence on dispersal distance. Seeds released from 0.75 m landed 4.4 ± 3.3 m (mean ± SD) from the release point in V. nigrum and 4.7 ± 3.5 m from the release point in V. rossicum, whereas seeds released from 2 m landed an average of 12.6 ± 9.6 m and 17.1 ± 12.1 m from the release point, respectively (DiTommaso et al. Reference DiTommaso, Stokes, Cordeau, Milbrath and Whitlow2018). The maximum dispersal distances (2-m release height) were 72.1 m for V. nigrum and 79.6 m for V. rossicum. This interspecific difference reflected the fact that V. nigrum seeds are heavier. Long-distance wind dispersal of V. nigrum seeds could require the combination of a high release point and a strong wind (DiTommaso et al. Reference DiTommaso, Stokes, Cordeau, Milbrath and Whitlow2018). Other seed-dispersal mechanisms are less common than wind dispersal. There are many anecdotal reports of animal dispersal, including dispersal by white-tailed deer (O. virginianus; DiTommaso et al. Reference DiTommaso, Stokes, Cordeau, Milbrath and Whitlow2018) and dispersal along hiking trails (Sandilands Reference Sandilands2013). Longer-distance transport is mostly anthropogenic. Vincetoxicum species have historically been transported deliberately as ornamentals and presumably continue to be transported inadvertently (see “Invasion Pathways”).

Within their bioclimatic envelopes (see “Habitat”), V. rossicum and V. nigrum are limited by competition from resident plant species. Greenhouse and growth chamber experiments have shown that competition against A. syriaca, Canada goldenrod (Solidago canadensis L.), and quackgrass [Elymus repens (L.) Gould] can substantially reduce Vincetoxicum performance (Blanchard et al. Reference Blanchard, Barney, Averill, Mohler and DiTommaso2010; Jackson and Amatangelo Reference Jackson and Amatangelo2021; Milbrath et al. Reference Milbrath, Biazzo, DiTommaso and Morris2019a; Sanderson and Antunes Reference Sanderson and Antunes2013). Research on V. nigrum has demonstrated that competitive responses are shaped by competitive environments over evolutionary time (Atwood and Meyerson Reference Atwood and Meyerson2011). Competitive environments also matter at smaller, more ecological spatiotemporal scales: in general, plant community invasibility depends on numerous determinants of resource supply and demand (Davis et al. Reference Davis, Grime and Thompson2000). However, some habitats invaded by V. rossicum and V. nigrum lack characteristics likely to promote resource surpluses, such as high disturbance levels (Averill et al. Reference Averill, DiTommaso, Mohler and Milbrath2010; DiTommaso et al. Reference DiTommaso, Lawlor and Darbyshire2005b).

Several factors may be helpful in explaining why V. rossicum and V. nigrum are so invasive. First, these species can survive and reproduce in low-resource environments (see “Life-Form and Life History”; “Growth and Development: Ecophysiology”). Second, positive density-dependent effects (e.g., plants twining together into a light-extinguishing mat) may help suppress allospecific competitors (see “Reproduction: Population Dynamics”). Third, their fitness is typically not limited by herbivores or pathogens in North America (enemy release; see “Management Options: Biological”). Vincetoxicum species contain phenanthroindolizidine alkaloids, notably (−)-antofine, in their seeds, leaves/stems, and roots (Capo and Saa Reference Capo and Saa1989; Gibson et al. Reference Gibson, Krasnoff, Biazzo and Milbrath2011, Reference Gibson, Vaughan and Milbrath2015; Mogg et al. Reference Mogg, Petit, Cappuccino, Durst, McKague, Foster, Yack, Arnason and Smith2008; Stærk et al. Reference Stærk, Christensen, Lemmich, Duus, Olsen and Jaroszewski2000). Vincetoxicum rossicum contains higher concentrations of (−)-antofine than V. nigrum; roots have higher concentrations than stems; and seeds, seedlings, and young plants of V. rossicum contain higher concentrations than adult plant roots (Gibson et al. Reference Gibson, Krasnoff, Biazzo and Milbrath2011, Reference Gibson, Vaughan and Milbrath2015). These compounds are highly cytotoxic, as demonstrated in experiments with human cancer cells (Stærk et al. Reference Stærk, Christensen, Lemmich, Duus, Olsen and Jaroszewski2000, Reference Stærk, Lykkeberg, Christensen, Budnik, Abe and Jaroszewski2002; Tanner and Wiegrebe Reference Tanner and Wiegrebe1993). Phenanthroindolizidine alkaloids, which appear to be rare in the Asclepiadoideae, could contribute to invasiveness by reducing palatability to herbivores in the introduced range (Liede-Schumann et al. Reference Liede-Schumann, Khanum, Mumtaz, Gherghel and Pahlevani2016). Mogg et al. (Reference Mogg, Petit, Cappuccino, Durst, McKague, Foster, Yack, Arnason and Smith2008) and Gibson et al. (Reference Gibson, Krasnoff, Biazzo and Milbrath2011) found that (−)-antofine from V. rossicum extracts exhibited antibacterial and especially antifungal activity. Mogg et al. (Reference Mogg, Petit, Cappuccino, Durst, McKague, Foster, Yack, Arnason and Smith2008) also reported insect antifeedant activity, which was not attributable to (−)-antofine. Similarly, other Vincetoxicum species contain alkaloids that deter feeding by nonspecialist insects (Kathuria and Kaushik Reference Kathuria and Kaushik2005; Verma et al. Reference Verma, Ramakrishnan, Mulchandani and Chadha1986).

Allelopathy has been proposed as a fourth explanation for successful Vincetoxicum invasion of occupied niches. Cappuccino (Reference Cappuccino2004) indicated that V. rossicum extracts inhibited radish (Raphanus sativus L.) seed germination in addition to exhibiting antifungal activity. Such data suggest that tissue leachates or root exudates from Vincetoxicum invaders could affect native plants both directly (inhibition) and indirectly (altered rhizosphere communities). The cytotoxic alkaloids may act as “novel weapons” (sensu Callaway and Ridenour Reference Callaway and Ridenour2004), promoting invasiveness. Similarly, Douglass et al. (Reference Douglass, Weston and Wolfe2011) found that V. rossicum and V. nigrum root exudates could reduce the germination and growth of some indicator species in laboratory tests (in one case, root exudates increased growth). Vincetoxicum tissue leachates had inhibitory, neutral, or stimulatory effects, depending on the indicator species (Douglass et al. Reference Douglass, Weston and Wolfe2011). Gibson et al. (Reference Gibson, Krasnoff, Biazzo and Milbrath2011) found that native Apocynaceae were more sensitive to (−)-antofine than V. rossicum and V. nigrum. However, Gibson et al. (Reference Gibson, Vaughan and Milbrath2015) reported that (−)-antofine degrades rapidly under ambient conditions and its allelopathic activity is greatly reduced in nonsterile soil. In addition, the concentrations of (−)-antofine in V. rossicum and V. nigrum root exudates were too low for significant biological activity, although the authors did not rule out (−)-antofine accumulation in the rhizosphere (Gibson et al. Reference Gibson, Vaughan and Milbrath2015). While high concentrations of (−)-antofine in seeds and seedlings might contribute to establishment, it is not clear that allelopathy plays a role in Vincetoxicum invasions.

Invasion Risk

Foster et al. (Reference Foster, Kharouba and Smith2022) developed MaxEnt and spatial dispersal models for V. rossicum across its invasion history in North America (10-yr intervals, 1890 to 2020). This analysis suggested that the North American distribution of V. rossicum was largely a function of dispersal in the early stages of invasion. Environmental constraints played a more important role in later stages. Foster et al. (Reference Foster, Kharouba and Smith2022) concluded that V. rossicum may have reached environmental equilibrium and that its geographic distribution may be stabilizing, but noted caveats related to the period of reference, spatial scale, and potential for dispersal limitation or local adaptation.

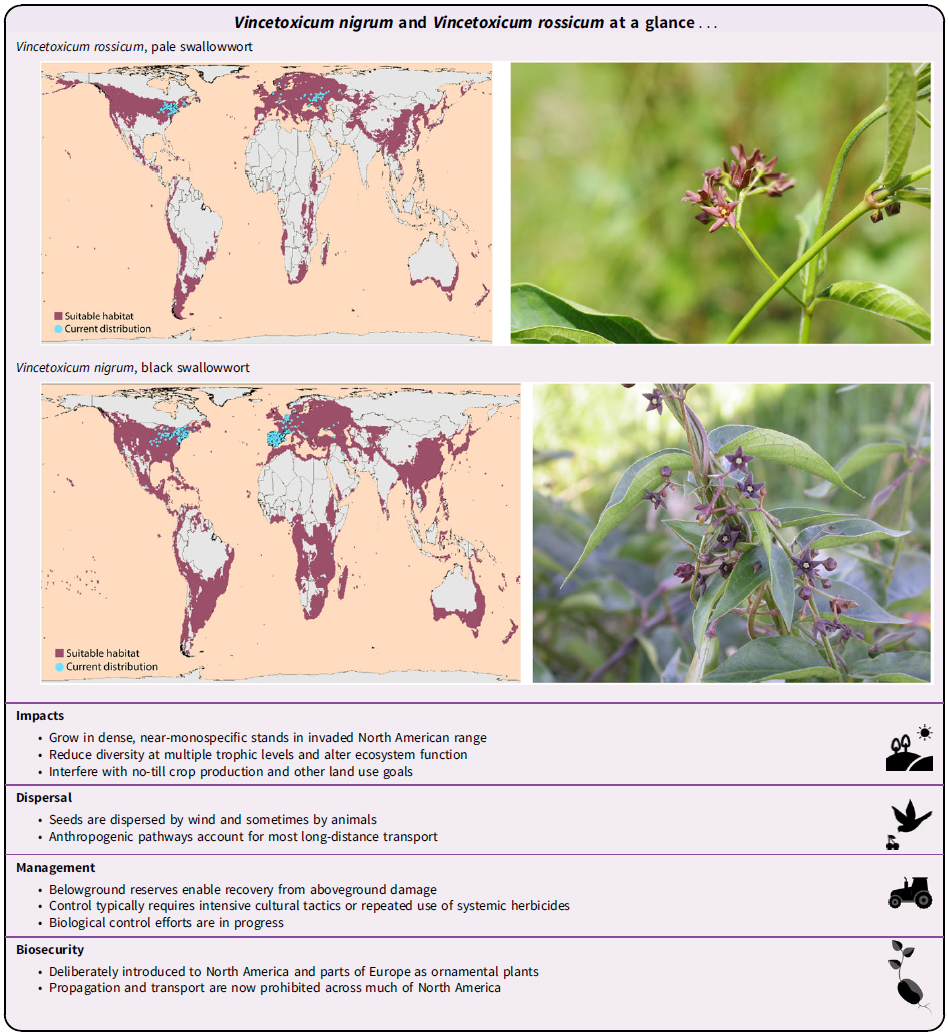

To our knowledge, potential distributions of V. rossicum and V. nigrum have not previously been modeled at a global scale. We developed CLIMEX models to identify regions of the world that are potentially suitable for V. rossicum and V. nigrum persistence under current climate. CLIMEX software (v. 4, Hearne Software, Melbourne, Australia) determines potential species distributions based on model parameters that describe how the species respond to climate. Model parameters reflect experimental data (when available) and species occurrence records. Our models were based on responses to temperature and precipitation; we did not explicitly account for factors such as land use or biotic constraints. Modeling methods are described in Supplementary Appendix S1, and model parameters are given in Supplementary Tables S2 and S3.

The CLIMEX models showed that the potential distributions of V. rossicum and V. nigrum are much larger than their current distributions (Figure 7). For example, the projected distribution of V. rossicum includes the northern half of the continental United States, and the projected distribution of V. nigrum includes most of the continental United States. Most areas of Europe are potentially suitable for both species. These results suggest that substantial range expansions are possible for both species.

Figure 7. Climatic suitability for (A) Vincetoxicum rossicum and (B) Vincetoxicum nigrum. CLIMEX models were based on temperature and precipitation (see Supplementary Appendix S1). According to these models, unshaded areas are not suitable for Vincetoxicum population growth, yellow areas are somewhat suitable, and red areas are highly suitable. Current species distributions are also shown with blue dots (Global Biodiversity Information Facility 2022a, 2022b).

Any discrepancies between our conclusions and those of Foster et al. (Reference Foster, Kharouba and Smith2022) could reflect the different goals, methods, and spatiotemporal scales of the two analyses. As different approaches provide different insights, it is useful to construct diverse models to develop a consensus picture of invasion risk. Further modeling efforts should also seek to develop high-resolution maps that account for additional influences on distribution (e.g., biotic constraints) and future climate change.

Invasion Pathways

Many reported introductions of V. rossicum, V. nigrum, and V. hirundinaria to new continents and regions have been deliberate (see “Invasion History”). These species were primarily introduced to North America as ornamental plants that escaped from gardens repeatedly and in multiple locations (Sheeley and Raynal Reference Sheeley and Raynal1996). Cultivation is now uncommon and sometimes prohibited in North America (Supplementary Table S1). Garden escapes have occurred to a lesser extent in Europe (Lauvanger and Borgen Reference Lauvanger and Borgen1998; Ronse Reference Ronse2013), where Vincetoxicum species are less likely to have large advantages over competitors. Long-distance Vincetoxicum transport may also occur inadvertently. Contamination in the nursery trade is one possibility (DiTommaso et al. Reference DiTommaso, Lawlor and Darbyshire2005b). This mode of transport could easily bridge continents, although frequent intercontinental transport seems unlikely to have occurred given the reduced genetic diversity of V. rossicum and V. nigrum in North America relative to Europe (Bon et al. Reference Bon, Jeanneau, Jones, Milbrath, Sforza and Dolgovskaya2010). Other plausible vectors for seed transport include vehicles, machinery, and hay (Cadotte et al. Reference Cadotte, Yasui, Livingstone and MacIvor2017; Plant Conservation Alliance’s Alien Plant Working Group 2006). Although non-anthropogenic mechanisms like wind dispersal usually operate over short or medium distances (see “Dispersal and Establishment”), they could allow infrequent long-distance transport. Seeds of horseweed [Conyza canadensis (L.) Cronquist] may travel very long distances by entering the planetary boundary layer (Shields et al. Reference Shields, Dauer, VanGessel and Neumann2006). Seeds of V. rossicum and V. nigrum might likewise achieve occasional long-distance transport when release height and wind speed are high (DiTommaso et al. Reference DiTommaso, Stokes, Cordeau, Milbrath and Whitlow2018). Given that V. rossicum is considered rare and even endangered in some parts of its native range, it is unlikely that the Russia–Ukraine conflict will affect its invasiveness in the region.

Growth and Development

Morphology

The competitiveness of Vincetoxicum species is influenced by resource allocation patterns. Both V. rossicum and V. nigrum rely on root reserves for overwintering and recovery from damage (DiTommaso et al. Reference DiTommaso, Lawlor and Darbyshire2005b). Root allocation allows gradual resource accumulation and thereby supports competitiveness and fitness (see “Life-Form and Life History”). Root-to-shoot ratios are typically higher in V. rossicum than in V. nigrum (Milbrath et al. Reference Milbrath, DiTommaso, Biazzo and Morris2016). For V. rossicum, Averill et al. (Reference Averill, DiTommaso, Mohler and Milbrath2010) reported root-to-shoot ratios of 2.6 and 3.5 (two sites, two seasons after sowing). McKague and Cappuccino (Reference McKague and Cappuccino2005) reported root-to-shoot ratios of nearly 1 in mature V. rossicum and greater than 3 in seedlings.

Root-to-shoot ratios are sensitive to abiotic and biotic environments. Milbrath (Reference Milbrath2008) reported high root-to-shoot ratios in V. rossicum (1.9 in mature plants and greater than 3 in seedlings), relative to consistently low ratios in V. nigrum (less than 1) under high light (488 to 916 μmol s−1 m−2). Under low light (12 to 25 μmol s−1 m−2), there was no interspecific difference. DiTommaso et al. (Reference DiTommaso, Averill, Qin, Ho, Westbrook and Mohler2021) reported a root-to-shoot ratio of 1.4 in V. rossicum and 0.5 for V. nigrum under sufficient soil moisture. Soil moisture deficit increased these root-to-shoot ratios to 3.0 in V. rossicum and 1.2 in V. nigrum. Cappuccino (Reference Cappuccino2004) reported that root-to-shoot ratios were marginally greater in smaller patches of V. rossicum relative to larger patches (plants in larger patches produced more vegetative biomass). Root-to-shoot ratios in V. rossicum may be higher under interspecific competition than intraspecific competition (Blanchard et al. Reference Blanchard, Barney, Averill, Mohler and DiTommaso2010). Sanderson and Antunes (Reference Sanderson and Antunes2013) found that competition for nutrients against S. canadensis increased the root-to-shoot ratio of V. rossicum by 40% (1.72 to 2.41) relative to V. rossicum grown alone. Conversely, competition against V. rossicum did not significantly increase the root-to-shoot ratio of S. canadensis. Taken together, these data indicate that plasticity in resource allocation represents an important component of V. rossicum’s response to competition.

Stress Tolerance

Vincetoxicum rossicum and V. nigrum overwinter as seeds and by perennating buds on the root crown (DiTommaso et al. Reference DiTommaso, Lawlor and Darbyshire2005b). Overwintering belowground allows V. rossicum to survive very cold temperatures, including minimum temperatures of −35 C in Ontario (Dickinson and Royer Reference Dickinson and Royer2014, p. 40; Dickinson et al. Reference Dickinson, Bourchier, Fulthorpe, Shen, Jones and Smith2021). Crown buds sprout at the beginning of the growing season or after aboveground damage, such as from spring frosts or stem removal (DiTommaso et al. Reference DiTommaso, Lawlor and Darbyshire2005b; McKague and Cappuccino Reference McKague and Cappuccino2005; LRM, personal observation). Regrowth from axillary buds also allows for tolerance to damage, especially under high light (see “Management Options: Cultural”).

Vincetoxicum species can tolerate seasonal (not prolonged) flooding, but do not occupy wetlands (DiTommaso et al. Reference DiTommaso, Lawlor and Darbyshire2005b; Lawlor Reference Lawlor2002). Vincetoxicum rossicum establishment may be reduced in poorly drained soil (Averill et al. Reference Averill, DiTommaso, Mohler and Milbrath2010). In a greenhouse experiment, V. rossicum height and V. nigrum biomass were reduced by recurring drought (Joline and DiTommaso Reference Joline and DiTommaso2016). Another greenhouse experiment showed that drought reduced growth (height, number of nodes, and biomass production) and reproduction, especially in V. rossicum (DiTommaso et al. Reference DiTommaso, Averill, Qin, Ho, Westbrook and Mohler2021). Vincetoxicum nigrum maintained higher rates of shoot growth and reproduction under drought (DiTommaso et al. Reference DiTommaso, Averill, Qin, Ho, Westbrook and Mohler2021). In a field study of V. hirundinaria in Sweden, supplemental watering (324 mm in addition to 130-mm rainfall) increased follicle (but not flower) production in the treatment year and the following year (Ågren et al. Reference Ågren, Ehrlén and Solbreck2008). Like water availability, soil pH does not narrowly constrain Vincetoxicum distributions (see “Habitat”) but can affect performance. For example, some authors have reported reduced biomass under low pH (Magidow et al. Reference Magidow, DiTommaso, Ketterings, Mohler and Milbrath2013; Sanderson et al. Reference Sanderson, Day and Antunes2015). The presence of Vincetoxicum species in urban environments and along roadsides (Cadotte et al. Reference Cadotte, Yasui, Livingstone and MacIvor2017; DiTommaso et al. Reference DiTommaso, Lawlor and Darbyshire2005b; Potgieter and Cadotte Reference Potgieter and Cadotte2020) might be facilitated by a tolerance to salinity or chemical toxins, but this hypothesis requires experimental testing.

Ecophysiology

Although both V. rossicum and V. nigrum are physiologically capable of tolerating low-light conditions, V. nigrum mostly occupies high-light sites (Averill et al. Reference Averill, DiTommaso, Mohler and Milbrath2011, Reference Averill, DiTommaso, Whitlow and Milbrath2016). Vincetoxicum rossicum is found in a variety of environments, but generally achieves higher survival, growth, and reproduction under high light (see “Habitat”; “Reproduction: Seed Production and Dispersal”; Hotchkiss et al. Reference Hotchkiss, DiTommaso, Brainard and Mohler2008; Milbrath Reference Milbrath2008; Milbrath et al. Reference Milbrath, Davis and Biazzo2017). Ambient light levels help determine specific leaf area in V. rossicum (Rochette Reference Rochette2019; Yasui Reference Yasui2016). Smith et al. (Reference Smith, DiTommaso, Lehmann and Greipsson2006) reported that V. rossicum plants grown under low light exhibited a classic shade phenotype (taller, thicker stems and larger, thinner leaves) that resulted in an increased tendency to climb over nearby plants. More generally, tall stems and high specific leaf areas may help V. rossicum invade and dominate existing plant communities (Livingstone et al. Reference Livingstone, Isaac and Cadotte2020a).

Vincetoxicum rossicum adopts a “sit-and-wait” strategy in low-light sites under forest canopies (Averill et al. Reference Averill, DiTommaso, Mohler and Milbrath2011, Reference Averill, DiTommaso, Whitlow and Milbrath2016; Hotchkiss et al. Reference Hotchkiss, DiTommaso, Brainard and Mohler2008). These plants can photosynthesize efficiently and store resources belowground until canopy disturbance increases light penetration, enabling substantial aboveground growth and seed production. This strategy can be understood as a special application of the long juvenile phase characteristic of Vincetoxicum species and especially V. rossicum (see “Life-Form and Life History”). The waiting strategy of V. rossicum has been observed at both plant and population scales: a forest population can persist at low density until disturbance releases additional resources (Averill et al. Reference Averill, DiTommaso, Mohler and Milbrath2011; Sheeley Reference Sheeley1992).

Phenology

In eastern Canada and the northeastern United States, seed germination and seedling emergence of V. rossicum and V. nigrum usually occur in a spring flush (often beginning in May) with germination and emergence continuing at decreasing rates through summer and autumn (often ending in October) (Averill et al. Reference Averill, DiTommaso, Mohler and Milbrath2010; DiTommaso et al. Reference DiTommaso, Lawlor and Darbyshire2005b; Milbrath et al. Reference Milbrath, Davis and Biazzo2017). Although not all newly dispersed seeds exhibit dormancy (DiTommaso et al. Reference DiTommaso, Brainard and Webster2005a, 2005b), germination and emergence are rare in the autumn relative to the spring (Milbrath et al. Reference Milbrath, Davis and Biazzo2017). Most autumn-germinating seeds germinate from the seedbank (i.e., they are more than 1 yr old; Milbrath et al. Reference Milbrath, Davis and Biazzo2017). After the establishment year, new shoots often emerge in late April or early May (DiTommaso et al. Reference DiTommaso, Lawlor and Darbyshire2005b). In northern New York, V. rossicum plants attained their maximum heights in late June or early July (Smith et al. Reference Smith, DiTommaso, Lehmann and Greipsson2006); Averill et al. (Reference Averill, DiTommaso, Mohler and Milbrath2011) indicated that maximum stem lengths for both species occurred by August across New York sites.

Flowering and follicle development overlap (DiTommaso et al. Reference DiTommaso, Lawlor and Darbyshire2005b). A generic phenology for V. rossicum and V. nigrum in the northeastern United States would predict most flowering and follicle development between June and early autumn, with seed dispersal beginning in August. The exact timing depends on species, climate, and habitat characteristics. In central and northern New York, flowering of V. rossicum can begin in mid- to late May and peak from late May to late June (Lawlor Reference Lawlor2000; Sheeley Reference Sheeley1992; Smith et al. Reference Smith, DiTommaso, Lehmann and Greipsson2006). Flowering may peak approximately 5 wk after the emergence of shoots (Sheeley Reference Sheeley1992). Follicle production may level off between mid-June and early August, remaining high until early September (Smith et al. Reference Smith, DiTommaso, Lehmann and Greipsson2006). In New York, seed dispersal in open habitats often begins in late July or early August (Lawlor Reference Lawlor2003). In Ontario, V. rossicum flowers from late May or June to August, although plants that resprout after being damaged may flower until the first frost (Christensen Reference Christensen1998; St. Denis and Cappuccino Reference St. Denis and Cappuccino2004). Christensen (Reference Christensen1998) reported that follicle development in southern Ontario occurs between mid-June and mid-August, seed dispersal begins by late August, and stems are dead by the end of September (Christensen Reference Christensen1998). Farther north near Ottawa, Ontario, follicle dehiscence may not begin until September, with seed release continuing through November (Cappuccino et al. Reference Cappuccino, Mackay and Eisner2002). Seed maturation, follicle dehiscence, and senescence are sometimes delayed (2 wk up to 1 mo) in shaded populations of V. rossicum relative to populations under high light (Christensen Reference Christensen1998; Lawlor Reference Lawlor2000; Livingstone et al. Reference Livingstone, Smith, Bourchier, Ryan, Roberto and Cadotte2020b; Milbrath et al. Reference Milbrath, Davis and Biazzo2017).

Within a growing season, the flowering period may be longer in V. nigrum than V. rossicum. Unlike V. rossicum, which may stop flowering as soon as early August in New York, V. nigrum can continue flowering until the first hard frost (Milbrath et al. Reference Milbrath, DiTommaso, Biazzo and Morris2016). Otherwise, phenology is generally similar between the two species. In southeastern New York, flowering of V. nigrum typically begins in mid- to late May, peaks in mid- to late June, and tapers off in July (Lumer and Yost Reference Lumer and Yost1995). Within this region, flowering tends to begin earlier at more southern sites and continue later (into August) at shadier sites (Lumer and Yost Reference Lumer and Yost1995). In the northeastern United States (New York and New England states), V. nigrum seed broadcast begins in late July or early to mid-August but may continue as late as October (Lumer and Yost Reference Lumer and Yost1995; URI CELS Outreach Center n.d.).

Mycorrhiza and Bacterial Symbionts

Vincetoxicum species associate with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF), which may improve performance in their introduced range. For example, Smith et al. (Reference Smith, DiTommaso, Lehmann and Greipsson2008) measured high rates of AMF root colonization in V. rossicum field-collected in New York, relative to co-occurring species such as S. canadensis and A. syriaca. Greenhouse experiments showed that soil containing AMF from the field site facilitated V. rossicum survival (relative to sterilized soil) and growth (relative to sterilized soil, sterilized soil reamended with an AMF-free microbial wash, or soil inoculated with an AMF isolate from Alabama, USA). Greipsson and DiTommaso (Reference Greipsson and DiTommaso2006) also observed high rates of root colonization in V. rossicum. Soil invaded by V. rossicum contained four times as many AMF spores as nearby non-invaded soil and had a higher mycorrhizal infectivity potential. Vincetoxicum rossicum has been described as a fungal generalist, associating with AMF (e.g., Rhizophagus spp. and Funneliformis spp.) with which nearby native plants may not associate (Bongard et al. Reference Bongard, Navaranjan, Yan and Fulthorpe2013b). Although V. rossicum may be capable of associating with diverse AMF, observed AMF communities are not always diverse. Dickinson et al. (Reference Dickinson, Bourchier, Fulthorpe, Shen, Jones and Smith2021) observed a low diversity of AMF colonizing V. rossicum roots across 54 sites in southern Ontario: only three species appeared at more than 5% of sites, two of which appeared at all sites. The authors suggested that these AMF species might resist antagonism by other fungal partners and might also resist allelochemicals such as (−)-antofine. Bongard et al. (Reference Bongard, Butler and Fulthorpe2013a) reported that native plants living in close association with V. rossicum were colonized at higher densities and by different AMF communities than native plants living without V. rossicum. Changes to soil AMF communities due to V. rossicum likely develop over multiple growing seasons (Day et al. Reference Day, Antunes and Dunfield2015a). Although V. rossicum often exerts a powerful influence on AMF communities, this influence is not always dominant. Bongard and Fulthorpe (Reference Bongard and Fulthorpe2013) found that garlic mustard [Alliaria petiolata (M. Bieb.) Cavara & Grande] could decrease the density of AMF on V. rossicum, but V. rossicum had less effect on A. petiolata.

Vincetoxicum–soil feedbacks are not exclusively mediated by AMF. Dickinson et al. (Reference Dickinson, Bourchier, Fulthorpe, Shen, Jones and Smith2021) identified 30 endophytes, including 12 known pathogens, whose abundances were positively correlated with aboveground biomass production in V. rossicum. In addition, aboveground biomass was positively correlated with the percentage of the fungal community represented by these 12 known pathogens. The authors suggested that fungal pathogens might promote V. rossicum invasion by negatively affecting competing plants. The authors also noted the presence of dark septate endophytes colonizing V. rossicum; like AMF, dark septate endophytes may provide their hosts with water and nutrients. The results of this field study (Dickinson et al. Reference Dickinson, Bourchier, Fulthorpe, Shen, Jones and Smith2021) were consistent with an earlier report (Day et al. Reference Day, Dunfield and Antunes2016) that V. rossicum can host fungi that increase its total biomass but do not facilitate native species and might even contribute to inhibitory effects on S. canadensis. In S. canadensis, unlike other native species, rhizosphere biota from V. rossicum–invaded soil appear to have a stronger negative effect on biomass than rhizosphere biota from uninvaded soils (Dukes et al. Reference Dukes, Koyama, Dunfield and Antunes2019). In its North American range, V. rossicum does not yet appear to be strongly inhibited by pathogenic fungi (see “Dispersal and Establishment”; “Management Options: Biological”). Despite the presence of pathogenic fungi, soil biota from invaded soils may have a net positive effect on V. rossicum with no evidence of pathogen accumulation over long time periods (100 yr; Day et al. Reference Day, Dunfield and Antunes2015b).

Fewer research projects have focused on bacteria. Thompson et al. (Reference Thompson, Bell and Kao-Kniffin2018) reported that invasion by V. rossicum did not explain much variation in bacterial community composition (unlike fungal community composition), soil respiration, or available soil nitrogen (N). In contrast, Bugiel et al. (Reference Bugiel, Livingstone, Isaac, Fulthorpe and Martin2018) reported that invasion by V. rossicum explained a significant portion of variation in bacterial community composition. Plant–soil feedbacks might also be mediated by the availability of nitrogen and other nutrients, but understanding these feedback mechanisms will require further research on nutrient dynamics in communities invaded by Vincetoxicum species (Liu Reference Liu2020).

Reproduction

Floral Biology

Vincetoxicum rossicum, V. nigrum, and V. hirundinaria (in Finland) can produce seeds by insect-mediated cross-pollination or self-pollination (Leimu Reference Leimu2004; Lumer and Yost Reference Lumer and Yost1995; St. Denis and Cappuccino Reference St. Denis and Cappuccino2004). These species, like other members of the subfamily Asclepiadoideae, have complex floral structures that facilitate insect pollination. Pollen is dispersed in a structure called a pollinarium, which consists of pollinia (sac-shaped masses of pollen grains) from two adjacent anthers connected by sterile structures called the translator (Kunze Reference Kunze1991). A notch in the center of the translator enables pollinarium dispersal by catching onto the proboscis (or perhaps leg) of an insect as the proboscis is removed from a floral nectary (DiTommaso et al. Reference DiTommaso, Lawlor and Darbyshire2005b; Kunze Reference Kunze1991).

In Ontario, up to 25% of naturally growing V. rossicum flowers had been visited by insects, as evidenced by the removal of pollinaria (St. Denis and Cappuccino Reference St. Denis and Cappuccino2004). In New York, Lumer and Yost (Reference Lumer and Yost1995) reported that V. nigrum plants were cross-pollinated exclusively by flies. The flies—mostly small, unspecialized species with short tongues—were apparently attracted by the dark color and strong odor of V. nigrum flowers. At least 14 species visited the flowers, six of which carried pollinia. Although observations of floral visitors in Ontario and New York are typically rare, other researchers have reported visits by flies, ants, bees, wasps, and beetles (Christensen Reference Christensen1998; Maclvor et al. Reference MacIvor, Roberto, Sodhi, Onuferko and Cadotte2017; Milbrath Reference Milbrath2010; St. Denis and Cappuccino Reference St. Denis and Cappuccino2004). Nocturnal visitors are possible but have not been documented if present. In Europe, V. hirundinaria is mainly pollinated by large flies, moths, and bees (Leimu Reference Leimu2004). Further research is needed to clarify which (if any) insects are important pollinators of invasive Vincetoxicum species and how pollinator availability affects population dynamics.