INTRODUCTION

The enteric protozoan parasite Cryptosporidium is an important cause of diarrhoeal disease in young mammals, particularly humans and ruminants. In immunocompetent individuals infections are self-limiting, characterized by mild, moderate, or severe acute symptoms [Reference Tzipori and Ward1]. In contrast, immunocompromised patients can suffer severe chronic or recurring cryptosporidiosis that can be fatal. One of the two most important agents of human cryptosporidiosis is the zoonotic species Cryptosporidium parvum which can infect a large range of hosts but is a major parasite of calves, goat kids and lambs. The other is Cryptosporidium hominis which is chiefly restricted to human hosts [Reference Cacció2].

Ireland has one of the highest reported incidence rates of cryptosporidiosis in Europe, with between 8·7 and 14·4 cases/100 000 population a year since 2004 [3]. A previous study found that C. parvum was by far the most common species in Ireland, accounting for about 80% of all human cases [Reference Zintl4]. Sequence analysis of the highly polymorphic GP60 locus revealed that 99% of the C. parvum population belonged to the zoonotic allele family IIa. The dominant allele IIaA18G3R1 accounted for about 63% of all IIa isolates.

In the present study we aimed to further investigate the parasite population structure in Ireland by including a larger sample set of sporadic human cryptosporidiosis cases in the GP60 analysis. Availability of 249 C. parvum isolates collected from Irish patients over a decade (from 2000 to 2009) provided a unique opportunity to determine whether predominant genotypes are being replaced as the population becomes immune to a particular subtype. Furthermore, it was determined whether there were seasonal, regional, gender-, or age-specific differences in the occurrence of GP60 subtypes and how the GP60 subtype distribution in Irish patients compares to the published literature. Finally we investigated the usefulness of two other variable loci, MS1 and ML1 for the characterization of the parasite's molecular epidemiology in Ireland.

METHODS

Irish C. parvum isolates collected between 2000 and 2009

C. parvum isolates from 2000, 2005, 2006 and 2007 were randomly selected from a sample bank collected during a previous study [Reference Zintl4]. DNA from C. parvum-positive stool samples collected in 2008 and 2009 were made available by the UK Cryptosporidium Reference Laboratory, Wales (CRU) once ethical approval had been obtained from the relevant hospital boards. All isolates had originally been submitted to Irish hospitals where they had been confirmed as Cryptosporidium-positive and then been sent either to the CRU or the UCD Veterinary Sciences Centre for identification. Basic epidemiological information including date of sample collection, patient age, sex and county of residence was available for all samples collected between 2005 and 2009 but not for 2000.

Subtyping of C. parvum isolates

C. parvum isolates (n=170) were subtyped by sequence analysis of the 60-kDa glycoprotein encoding gene fragment (GP60) [Reference Peng5–Reference Chalmers7]. In addition, 79 further samples that had been analysed at this locus during a previous study [Reference Zintl4] were also included in the analysis. A subset of 127 samples (all collected in 2008 and 2009) was analysed by fragment size analysis at two further micro- and minisatellite regions: the 12-bp repeat region MS1 situated in the HSP70 locus [Reference Mallon8, Reference Xiao, Ryan, Fayer and Xiao9] and ML1, a GAG repeat region first described by Cacciò et al. [Reference Cacciò10].

The primer sequences and protocols for all three nested PCR reactions are provided in Table 1. All PCR reactions were performed in a total volume of 50 μl containing 2 μl unquantified DNA template (in the primary PCR) and 1 μl primary PCR product (in the nested PCR), 1× PCR buffer (GoTaq Flexi, Promega, USA), 200 μm of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 0·2 μm of the forward and reverse primers, 20 μg non-acetylated BSA (Sigma, USA) and 2·5 U Taq polymerase (GoTaq Flexi, Promega). MgCl2 concentrations of 3 mm were used in the GP60 PCR protocol and 1·5 mm in the ML1 and MS1 protocols. Positive (purified C. parvum DNA) and negative (master mix without a DNA template) controls were included in each batch of PCR amplification reactions. For GP60 analysis, PCR products were purified using the QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen, USA) and sequenced (GATC Biotech AG, Germany). The sequences were edited manually, compared with published sequences using NCBI Blast and aligned with the ClustalW sequence alignment programme to identify the GP60 allele family. Within the IIa family subtypes were identified using the nomenclature proposed by Sulaiman et al. [Reference Sulaiman11].

Table 1. Details of the nested and hemi-nested PCR protocols used for multi-locus molecular analysis of C. parvum isolates

The number of repeats at the MS1 and ML1 loci were determined by using 6-FAM-labelled internal primers (5′ end) and analysing the amplified fragments on an Applied Biosystems Genetic Analyser (3130 xl) with the aid of GeneMapper Software (Applied Biosystems, USA). In order to confirm fragment size analysis results, ten MS1 and ML1 amplicons each were also purified and sequenced.

Statistical analysis

Temporal, regional, sex- and age-specific differences in the relative number of GP60 subtypes in samples collected between 2005 and 2009 were analysed using χ2 analysis. No epidemiological data were available for samples collected during 2000 except that they originated from Connaught. Consequently GP60 subtypes identified for this year were only included in the annual and regional comparisons.

RESULTS

GP60 genotypes

All GP60 genotypes analysed during this study belonged to subtype family IIa. Within this family a total of 16 alleles were identified (Table 2). IIaA18G3R1 was the predominant subtype accounting for 58% of all cases. The next most common genotypes were IIaA20G3R1 (12%), IIaA15G2R1 (9·6%) and IIaA19G3R1 (4·8%). Seven subtypes were only identified once or twice during the course of the study. A plot of the number of TCA/TCG repeats in the GP60 locus revealed a bell-shaped distribution, with a peak at 21 repeats (Fig. 1 a). All isolates only had one copy of the ACATCA sequences (designated as R1). Ten samples (4%) failed to amplify in the GP60 region. Moreover, two samples provided poor sequence information and could not be identified to genotype level.

Fig. 1. Number of GP60 TCA/TCG repeats in sporadic human cryptosporidiosis cases in the current study (a) and in other published work in areas where C. parvum (b) and C. hominis (c) predominated compared to the number of GP60 repeats in cattle reported worldwide (d) (data compiled as described in the text).

Table 2. IIa GP60 subtypes identified in the present study and reported from human and livestock cases

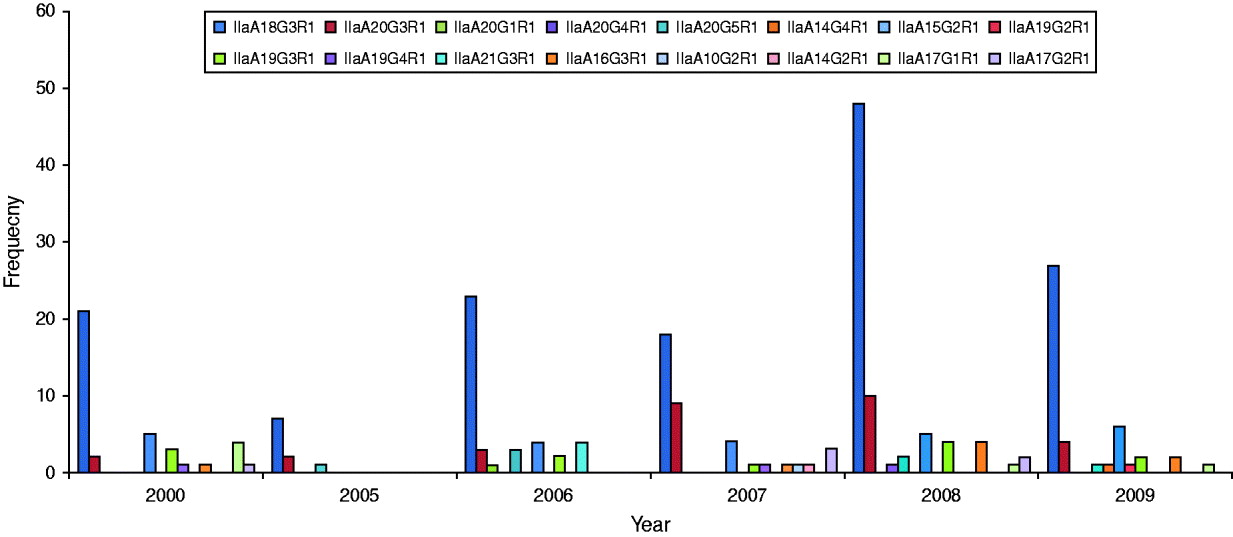

Annual and seasonal occurrence of GP60 subtypes

GP60 genotypes recorded in each year are presented in Figure 2. Predominant subtype IIaA18G3R1 accounted for about 58% in all years except in 2007 when it was only 46%, while genotype IIaA20G3R1 was unusually high making up 23% of all cases. Unusual genotypes, that were only identified once or twice throughout the study period, occurred in most years but were most common in 2007. GP60 subtype IIaA21G3R1 was only recorded in 2006 where it accounted for 10% of all analysed samples. These four cases occurred throughout the year (the samples were collected in February, March, April, and November) in children aged <10 years that were resident in the southeast of the island (two in Munster and two in Leinster). These annual differences in genotype distribution were statistically significant (χ2=131·9, d.f.=75, P<0·005).

Fig. 2. Annual distribution of GP60 subtypes (χ2=131·9, d.f.=75, P<0·005).

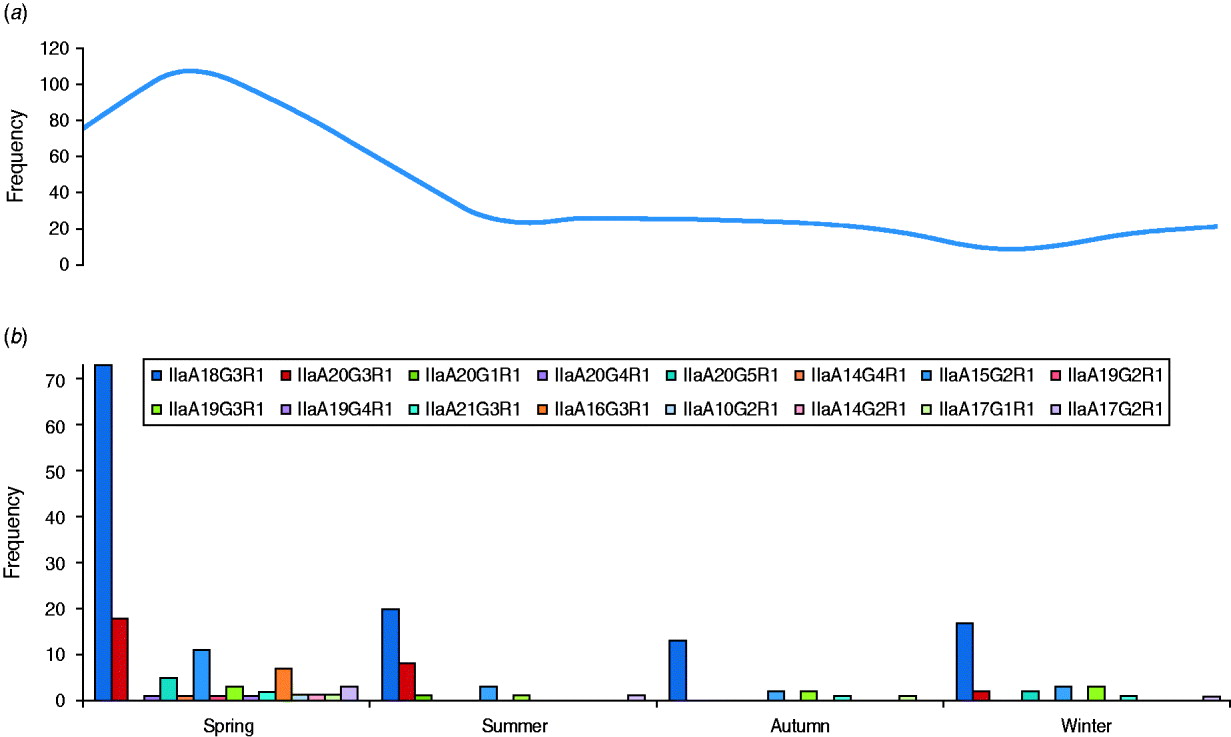

The GP60 subtypes detected each season (between 2005 and 2009) are presented together with the average seasonal incidence of cryptosporidiosis according to figures provided by the Health Protection Surveillance Centre (HPSC, 2008) (Fig. 3). The proportion of the dominant subtype IIaA18G3R1 was slightly lower than average during spring (56%), increased during the summer and peaked in autumn (68% of all analysed samples). The second most frequent genotype, IIaA20G3R1, was most common during the summer months (23·5%) but rare or absent during the second half of the year. In contrast, genotype IIaA19G3R1 was mainly observed in autumn and winter (10% of all typed cases) but was rare in spring (2·3%) or summer (2·9%). Seven out of the total of 16 GP60 subtypes were only identified during the spring. Overall these seasonal shifts were not statistically significant (χ2=60·9, d.f.=45, P=0·06).

Fig. 3. Average number of (a) cryptosporidiosis cases and (b) GP60 genotypes per season (2005–2009) (χ2=60·9; d.f.=45, P=0·06).

Regional distribution of GP60 subtypes

In order to detect regional differences in the occurrence of genotypes, GP60 typing results were pooled for the years 2000 and 2005–2009 and presented separately for each province: Leinster in the east, Munster in the southwest and Connaught in the west of Ireland (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. GP60 subtypes in (a) Connaught, (b) Munster and (c) Leinster (χ2=121·1, d.f.=30, P<0·005).

IIaA18G3R1 was the dominant genotype in all provinces (accounting for 40% of all isolates typed in Leinster, 57% of all isolates typed in Connaught and 70% of all isolates from Munster) followed by IIaA20G3R1 in Leinster (24%), and Munster (13%). In Connaught subtype IIaA15G2R1 was just as common as IIaA20G3R1 (each made up about 12%). In Leinster IIaA15G2R1 accounted for 8% of all typed cases, while in Munster it occurred only rarely (4%). GP60 subtype IIaA21G3R1 was recorded in Leinster (8%) and Munster (4%), but was absent from Connaught. Of the seven less common genotypes, four were recorded in Connaught. The regional differences were statistically significant (χ2=121·1, d.f.=30, P<0·005).

Age- and sex-specific prevalence of GP60 subtypes

There were no significant differences in the occurrence of GP60 genotypes in male and female patients (χ2=23·1, d.f.=15, P=0·07). Coincident with the typical age profile of cryptosporidiosis in the overall population, over 70% of all typed cases occurred in children aged <5 years, which made a comparison of the prevalence of GP60 subtypes by patient age problematic. Overall the pattern of GP60 subtypes in each age group appeared to be similar except that allele IIaA15G2R1 was significantly more common in infants (17·4%) and children aged <5 years (5·6%) than in older children (3·8%) and adults (none recorded) (χ2=99·9, d.f.=75, P<0·05).

MS1 subtypes

Of a total of 127 isolates from 2008 and 2009, 121 were successfully typed in the MS1 locus. The majority of isolates (97%) were 348 bp in length which was equivalent to 11 repeats of the 12-bp mini-satellite region. Three isolates from 2008 were shorter at 312 bp (equivalent to eight repeats), and one from 2009 was significantly longer with 384 bp (equivalent to 14 repeats). All three samples from 2008 had been collected during August, from 2-year-old children (two male and one female). Two of the children were resident in Connaught (for the third child no address was provided). The 384-bp MS1 isolate identified in 2009 originated from a 1-year-old boy also resident in Connaught. This sample had been collected in May. All four cases were GP60 allele IIaA18G3R1 and ML1-238.

ML1 subtypes

Amplification of the ML1 locus was successful in 125 cryptosporidiosis isolates. Most isolates (97%) belonged to the same ML1 subtype measuring 238 bp with 10 GGA repeats. Four isolates, three from 2008 and one from 2009, had different ML1 alleles; in 2008 there was one 226-bp ML1 subtype (with six microsatellite repeats) and two 250-bp ML1 alleles (with 14 repeats). The three isolates were collected from boys aged <5 years in Connaught during spring and early summer. In 2009 an ML1 subtype that measured 241 bp (with 11 repeats) was isolated from a 14-year-old boy from Connaught. The ML1 226-bp and 241-bp isolates were GP60 subtypes IIaA18G3R1, while one ML1 250 bp was GP60 subtype IIaA20G4R1, and the other one IIaA19G3R1. All four had 348-bp alleles at the MS1 locus.

DISCUSSION

Overall the range of GP60 subtypes detected in this study was very diverse, with a total of 16 different alleles identified, five of which had not been reported from humans before (Table 2). IIaA18G3R1, by far the most common genotype recorded, has previously been identified as the predominant subtype in sporadic cases in humans and cattle in Northern Ireland, Australia and New Zealand [Reference Glaberman12–Reference Thompson20] and was the causative agent of a waterborne outbreak in Northern Ireland in 2000 [Reference Glaberman12] and an outbreak involving direct animal contact in the UK in 2007 [Reference Chalmers and Giles21]. Elsewhere, however, this subtype has only rarely been reported: a single human case in Switzerland [Reference O'Brien, McInnes and Ryan14], and isolated cases in cattle in The Netherlands [Reference Wielinga25], Spain [Reference Quílez37] and Canada [Reference Trotz-Williams41]. Similarly, the next most common subtype in our study, IIaA20G3R1, has previously been reported from Australia and occasionally from the UK. In contrast, IIaA15G2R1, the most widely distributed subtype worldwide and chief agent of zoonotic cryptosporidiosis only accounted for about 10% of all cases.

The GP60 gene encodes the 15- and 40-kDa cell surface glycoproteins both of which are implicated in host cell attachment and invasion and as such are thought to be under host selection [Reference Leav46, Reference Widmer47]. Consequently it would be expected that dominant GP60 subtypes are replaced over time as new subtypes emerge and host populations develop immunity to those that have been in circulation for some time. In contrast, we found that subtype IIaA18G3R1 continued to be the most prominent allele over the 10-year study period from 2000 to 2009. Either the study period was not long enough for a shift in dominant subtypes to become apparent or the immunity against homologous genotypes is either not specific enough or too short-lived to cause a decline in the dominant subtype.

Statistically the year 2007 stands out because of a relatively high prevalence of subtype IIaA20G3R1 and the larger variety of genotypes. In spring of 2007, the first large-scale cryptosporidiosis outbreak, caused chiefly by C. hominis occurred in Ireland [Reference Pelly48]. No doubt increased awareness led to more cases being reported in that year which may have caused a shift in the prominent genotypes as less pathogenic ones that usually go unreported were identified.

During the spring each year, coincident with the annual peak in the overall incidence of human cryptosporidiosis as well as the main calving and lambing seasons, the highest diversity in the GP60 subtypes was observed. On the other hand, two relatively common subtypes, IIaA20G3R1 and IIaA19G3R1 were mostly restricted to the early and latter halves of the year, respectively. There are no previous records of a seasonal segregation of these two subtypes.

The overall incidence data of cryptosporidiosis in Ireland released by the HPSC [3] show an uneven distribution across the country, with fewer cases in the most densely populated and urbanized east (Leinster) and an increase in cases towards the predominantly rural west (Connaught) and the southwest (Munster) which occupies large areas of low population density, but also includes some major urban centres. The east–west differential is also apparent in the importance of livestock farming as a source of income in the southeast, the midlands and the west coast compared to the east. This uneven incidence of cryptosporidiosis across the country was reflected in slight shifts in the occurrence of GP60 subtypes. IIaA18G3R1, although predominant in all regions, was most prevalent in the southwest, while the otherwise ubiquitous genotype IIaA15G2R1 was particularly rare there. In contrast, the west which has probably the lowest influx and efflux rate of people but a high level of agricultural activity had the highest prevalence of IIaA15G2R1 and also the largest diversity of GP60 subtypes. Similar, although much more pronounced spatial clustering of GP60 subtypes has previously been reported for livestock [Reference Alves6, Reference Jex15, Reference Alves26, Reference Enemark49].

It may be expected that sex- and age-specific differences in exposure to cryptosporidiosis and age-dependent susceptibility may be reflected in different GP60 allele prevalences in the two genders and age classes. However, the only notable difference was the relatively higher rate of occurrence of IIaA15G2R1 in infants and children aged <5 years. Although this is the most common genotype in cattle worldwide, it has also been reported from patients without direct livestock contact and is thought to circulate in human populations without frequent zoonotic transmission [Reference Geurden24]. This hypothesis is supported by its presence in very small children.

It has been widely reported that the relative prevalences of the two main human pathogenic species of Cryptosporidium follow typical patterns in different geographical regions. For instance, in Europe and New Zealand, both, C. parvum and C. hominis occur with similar frequency. In contrast, the prevalence of C. hominis by far outweighs that of C. parvum in most studies performed in the USA, Australia, Japan and most developing countries [Reference Xiao, Ryan, Fayer and Xiao9]. While some of this bias may be due to differences in the immune status of the study population (e.g. HIV-positive vs. otherwise healthy individuals), or investigations of outbreak vs. sporadic cases [Reference Feltus31], it is generally accepted that zoonotic transmission plays a greater role in Europe and New Zealand than in countries where C. hominis predominates.

In Ireland, C. parvum is much more common than C. hominis [Reference Zintl4]. In addition, all isolates tested in the present study belonged to GP60 allele family IIa. This is the predominant subtype family in ruminants and is most frequently seen in areas with intensive animal production [Reference Alves6, Reference Jex15, Reference Alves26] indicating a high level of zoonotic transmission. However, a comparison of the frequency distribution of the GP60 TCA/TCG repeats of Irish C. parvum isolates with GP60 subtypes recorded in the literature gave astonishing results. Figure 1(b, c) provides frequency distributions of GP60 TCA/TCG repeats of human C. parvum isolates compiled from published data from study areas with predominantly zoonotic (Fig. 1b) and anthroponotic transmission (Fig. 1c), respectively [Reference Alves6, Reference Chalmers7, Reference Sulaiman11–Reference Grinberg19, Reference Hijjawi22, Reference Geurden24–Reference Feltus31, Reference Trotz-Williams41, Reference Peng42, Reference Abe50, Reference Wu51]. Surprisingly, GP60 fragment lengths of the Irish C. parvum population mirror that reported for C. parvum in areas where C. hominis is more common than C. parvum, indicating a predominance of anthroponotic transmission. In contrast, the number of TCA/TCG repeats in C. parvum isolates identified in areas with predominantly zoonotic transmission show two peaks: a major one at 17 repeats, which is the most important one reported from cattle worldwide (Fig. 1d) [Reference Alves6, Reference Chalmers7, Reference O'Brien, McInnes and Ryan14, Reference Ng17, Reference Grinberg19, Reference Thompson20, Reference Nolan23, Reference Wielinga25, Reference Alves26, Reference Soba and Logar28, Reference Brook32–Reference Misic and Abe45, Reference Abe50–Reference Silverlås53], and a minor one at 21 repeats which coincides with the main peak observed in C. parvum isolates from areas where anthroponotic transmission is more common. This is not to say that some genotypes are only zoonotic or anthroponotic (for instance, IIaA15G2R1, the main genotype represented by TCA/TCG repeat 17, is the most common genotype in cattle but is also frequently detected in people without livestock contact, whereas IIaA18G3R1, represented by 21 TCA/TCG repeats, is the most common genotype in humans in areas with anthroponotic transmission, but also predominates infections in cattle in Northern Ireland and some herds in Australia), but that the predominance of different transmission routes may give rise to characteristic patterns of genotype prevalence in a region. The pattern of C. parvum isolates in Ireland indicates a much more important role for human-to-human and indeed human-to-animal transmission of C. parvum than previously thought. As many wastewater treatment plants are not designed to remove or de-activate Cryptosporidium oocysts [Reference Cheng54] and 30% of the population are served by septic tanks many of which are thought to be inefficient or faulty [55], the infection pressure on surface waters from anthroponotic as well as zoonotic sources is probably high. On the other hand, drinking water for both humans and livestock are chiefly extracted from surface waters. As a result humans and animals may be continuously infecting each other, which may help to explain the unusual distribution of GP60 subtypes in Ireland.

In addition to GP60, we characterized a subsample of the human C. parvum isolates using two further loci, MS1 and ML1. Both loci were far too homogenous to be useful for source or geographical tracking, with 97% of all typed isolates belonging to MS1-348 and ML1-238, respectively. For each locus, four isolates had different alleles; however, these were different isolates in the two loci. Moreover, the eight isolates, all of which occurred in Connaught, were not distinguished by any specific GP60 subtype. The three MS1 subtypes observed in this study are equivalent with MS1-328, MS1-364 and MS1-400 identified by Mallon and colleagues [Reference Mallon56] who used different though overlapping reverse primers, which amplified products that are 16 bp longer than ours. The predominant ML1 subtype in this study (ML1-238) was designated C1 by Cacciò et al. [Reference Cacciò10]. This ML1 subtype has been reported from humans and livestock in Europe, the USA, Australia and Japan [Reference Chalmers7, Reference Cacciò10, Reference Wielinga25, Reference Mallon56–Reference Leoni59] in both sporadic and outbreak situations. C2 (or ML1-226) which was only identified once in our study has been reported from several European countries and may be more common in humans than in livestock [Reference Cacciò10, Reference Wielinga25, Reference Leoni59]. The other two ML1 subtypes of 241 bp and 250 bp detected in our study have not been observed before.

In conclusion, IIaA18G3R1 was the predominant C. parvum genotype every year, in every season and in all parts of the country. There was no evidence over the 10-year study period that the predominant genotype was replaced as the population gained immunity. At the same time some significant shifts in the distribution of GP60 genotypes between years and geographical regions were detected. Moreover, our results indicate that the representation of Cryptosporidium transmission cycles as chiefly anthroponotic or zoonotic is an oversimplification as the relative prevalence of C. parvum and C. hominis in Ireland on the one hand and the distribution of GP60 subtypes on the other indicate that although zoonotic transmission no doubt plays a major role, human-to-human and indeed human-to-animal transmission may also be a common occurrence.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the various hospital diagnostic laboratories for making samples available to us. We also thank Carlotta Sacchi for excellent technical support. This work was funded by the Environmental Protection Agency under the STRIVE programme.

DECLARATION OF INTEREST

None.