Introduction

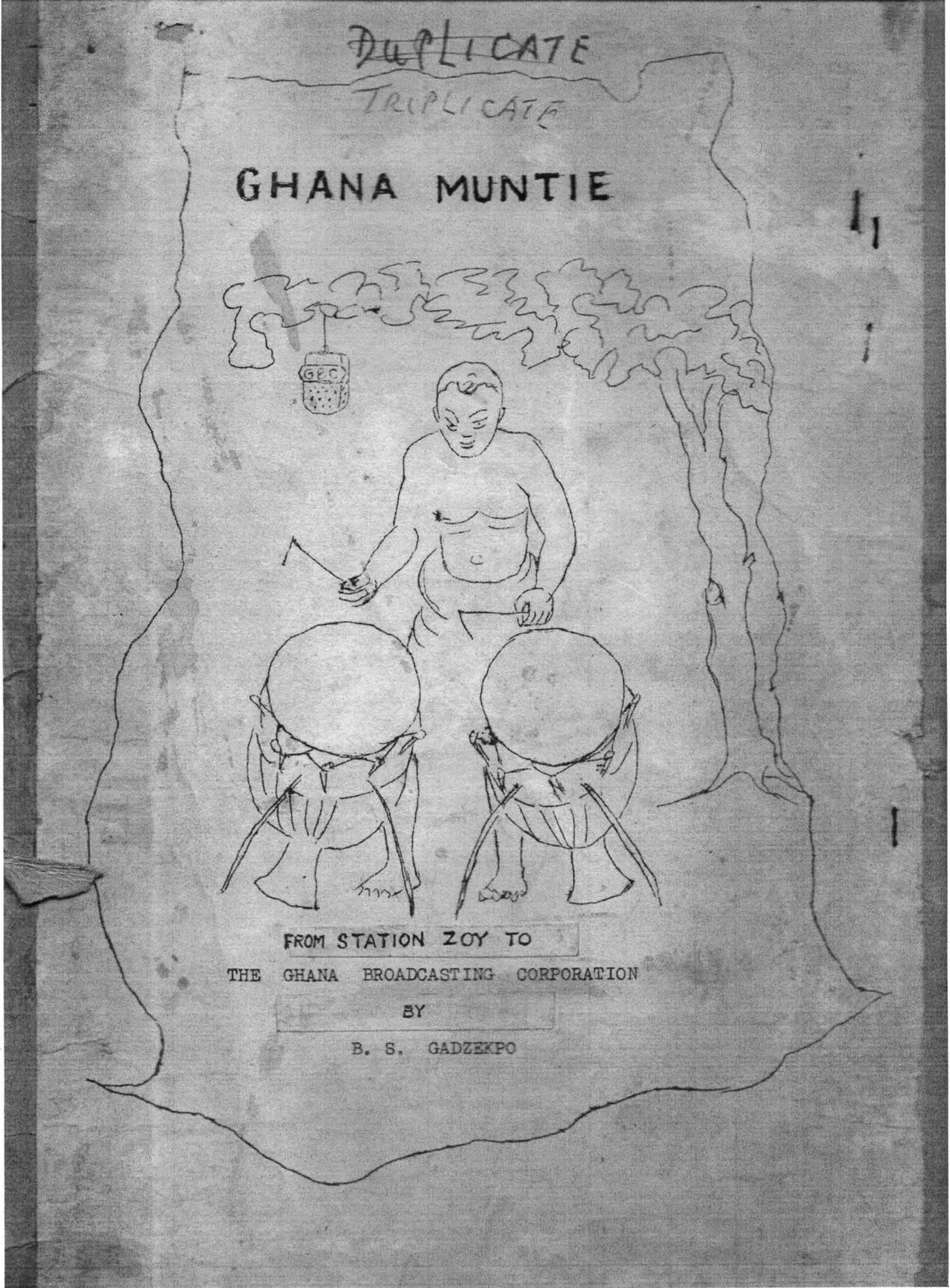

In his insightful piece on the historical value of the works of little-known Africans, David Killingray (Reference Killingray2010: 5) notes how ‘serendipity and surprise occasionally contribute to the work of the historian’ and how ‘a chance discovery of crucial documents … can set the adrenalin pulsating’. For me that ‘eureka moment’ occurred in 2014 when a combination of deep personal and academic curiosity about my grand-uncle – Bernard Senedzi Gadzekpo – resulted in the discovery of his radio memoir, ‘Ghana muntie: from Station ZOY to the Ghana Broadcasting Corporation’. The unpublished manuscript and other documents had been left languishing in a cupboard until I paid them a visit. B. S. Gadzekpo, as he was known in family circles, was a pioneer broadcaster with a long and distinguished service in radio, straddling both the colonial and postcolonial era in Ghana (Figure 1).

Figure 1 B. S. Gadzekpo. Note: All figures reproduced in this article are taken from B. S. Gadzekpo's unpublished manuscript ‘Ghana muntie’.

Since its introduction on the continent in the 1920s, radio has been integral to the socio-cultural and political life of Africans. The iconic image of a family gathered around a radio set is a familiar one, often used to convey the centrality of the technology to the communal lives of Africans. Chikowero (Reference Chikowero, Bloom, Miescher and Manuh2014: 114) argues that radio ‘embodied multiply articulated ideologies of power, modernity and status’ and accuses it of being a ‘dubious tool of colonial assault’. The medium's complicated history has seen it deployed by both colonial and postcolonial governments in a multiplicity of ways – a tool for enlightenment, advanced administration, education, entertainment, propaganda, modernization, nation building, unity, development and democratization (Ansah Reference Ansah1985; Larkin Reference Larkin2008; Smyth Reference Smyth, Bloom, Miescher and Manuh2014; Chikowero Reference Chikowero, Bloom, Miescher and Manuh2014; Akrofi-Quarcoo and Gadzekpo Reference Akrofi-Quarcoo and Gadzekpo2020). Today, it remains the foremost conduit to news and information for ordinary people.Footnote 1

Despite its historical and contemporary importance, the literature on the development of radio, especially in West Africa, is scanty. In Ghana, where radio was introduced in 1935 and considered the most developed in the sub-region, there are surprisingly few published histories beyond book chapters or sections in more general media histories. Unpublished theses (Graettinger Reference Graettinger1977; Last Reference Last1980; Pratt Reference Pratt2013) and special write-ups, such as Ansah's (Reference Ansah1985) historical essay marking the golden jubilee of the Ghana Broadcasting Corporation (GBC) and Head and Kugblenu's (Reference Head and Kugblenu1978) article on Radio One, are useful but insufficient to provide a fuller historical trajectory of radio in Ghana. The paucity of historical material makes the fortuitous find of B. S. Gadzekpo's unpublished radio memoir especially significant as it provides us with a personalized version of the first three decades and more of radio in Ghana.

Gadzekpo was a prolific writer and a creative who in the mid-1950s retold Eʋe folktales for West African Voices, a literary programme broadcast on the BBC Overseas Service (Smith Reference Smith and Smith2018). Though singled out in this article, the autobiographical account of his experience in radio was by no means the only witness to his intellectual output. I discovered other unpublished manuscripts, such as ‘Principles of translation (with particular reference to translation from English into Gold Coast languages and vice versa)’, co-authored with his radio colleague Joseph Ghartey, and ‘The Eʋe language: its growth and some peculiarities’. Included in the cache of unpublished writings were poems in both English and Eʋe (Gadzekpo's first language), an Eʋe manuscript titled Metso tɔgbinye ɖo,Footnote 2 and a piece of paper on which he noted the existence of other manuscripts – ‘My life’, an autobiography, and a biography he had written on Vinɔkɔ Akpalu, the renowned Anlo-Eʋe composer. While the biography of Akpalu has been traced and is being prepared for publication, the autobiography appears to have been misplaced.

Gadzekpo also published books in Eʋe such as Akagla Kple Wɔdegbee (Reference Gadzekpo1949a), Ewɔtɔ Ku, Ɛdulali (Reference Gadzekpo1949b) and Yedzefe Mɔzɔla (Reference Gadzekpo1948)Footnote 3 – the latter was a translation of Thomas Mofolo's allegory ‘The traveller of the east’. His published English-language guide on how to produce local-language music programmes titled Some Hints on the Production of Vernacular Music Broadcast Programmes (Reference Gadzekpo1955) was particularly well received. Archival evidence shows that he got a congratulatory letter from James Millar, the Director of Broadcasting of the Gold Coast Broadcasting Service (GCBS), who described it as ‘a useful document to circulate … and particularly to newcomers to the service’.Footnote 4 It was also lauded in the minutes of a GCBS programme meeting where it was noted that the publication had ‘raised considerable interest with a dozen copies ordered by Nigeria and Uganda and enquiries from others, who saw a reference in a London circular letter’.Footnote 5

This impressive evidence of knowledge production by a non-academic establishes Gadzekpo as an important but largely overlooked local intellectual deserving of scholarly attention. He illustrates the long tradition, dating to the nineteenth century, of literate Africans, particularly teachers in British colonies, collecting or producing ethnographic and historical texts (Jézéquel Reference Jézéquel, Lawrance, Osborn and Roberts2006). Gadzekpo's radio memoir in particular warrants attention as a primary document with which we can make new meaning of how the second ever radio station established in West Africa – Station ZOY – functioned in the colonial period and developed into Radio Ghana. Written as a positioned account of his life in public broadcasting, the memoir provides a subjective but valuable construction of the historical trajectory of radio.

In this article I demonstrate how the personal experiences contained in Gadzekpo's unpublished manuscript foreground African broadcasters in the history of radio and position them as ‘intermediaries’ who, to co-opt Lawrance et al. (Reference Lawrance, Osborn, Roberts, Lawrance, Osborn and Roberts2006: 4), ‘bridged the linguistic and cultural gaps that separated European colonial officials from subject populations by managing the collection and distribution of information’. I also show how this autobiographical account provides a counter-narrative on momentous events such as World War Two by drawing attention to the ‘battles’ fought by Africans behind and beyond the microphone. While the memoir is specific to the Ghanaian experience, it offers insights into the complex realities of Africa's mutable encounter with radio and the strategic role played by local intellectuals in fulfilling its modernization mission during and after the colonial period. Extracts of the memoir are available in the print and online version of Africa. The full text is available as supplementary material published with this article and available via <https://doi.org/10.1017/S0001972021000012>.

Biographical information

B. S. Gadzekpo was born in Lomé, Togo on 26 September 1905 and died on 23 June 1989 at the age of eighty-three. When he was just three years old, his father, a produce buyer for Messrs F. A. Swanzy, enrolled him in the Bremen Mission Nursery School in Vodza, their ancestral home; this was rather unusual for the times. Gadzekpo continued his early missionary education first at Keta Bremen (Presbyterian) Mission School and then at the Akropong Teacher Training College (1924–26). Founded by the Basel missionaries in 1848, the Akropong Teacher Training College has the distinction of being the first institution of higher learning in Ghana. Consequently, Gadzekpo's early career was as a trained teacher at the Keta Roman Catholic School for six years and later at the Eʋe (now Evangelical) Presbyterian Church School for another ten years. The change in his career path occurred in 1943 when he was seconded to the Information Department to work as a vernacular announcer on Station ZOY, which had been established in 1935. World War Two was still raging at the time and educated Africans who were well versed in local languages were needed to translate news and information for the populace. The colonial authorities found teachers particularly attractive because they had credibility within their communities (Ansah Reference Ansah1985) and could bridge the language gap. Gadzekpo quotes John Wilson, head of the Education Department, as observing that teachers made the ‘best linguists to speak to the people in their languages’. Research by Miescher (Reference Miescher2005), Larkin (Reference Larkin2008) and Skinner (Reference Skinner2015) affirms the high esteem in which teachers, particularly mission-educated ones such as Gadzekpo, were held during the colonial period and the expectations placed on them by church and colonial authorities to bring ‘enlightenment’ to their societies. Ironically, teachers were also distrusted by these same authorities, who were suspicious of their political activism and the undue influence they wielded within their communities. As Skinner (Reference Skinner2015) notes, teachers tended to belong to grass-roots political movements and were disproportionately represented in colonial legislatures (for example, they made up 30 per cent of the Gold Coast legislature of 1954).

Gadzekpo was a quietly ambitious man of considerable achievement who exemplified the Presbyterian ethic of piety, hard work, discipline, diligence and moderation (Miescher Reference Miescher2005). Despite his accomplishments he was reputed to often espouse dictums such as ‘there is more room at the top’ and ‘determination is half the battle’,Footnote 6 and reportedly remarked in a speech on the occasion of his seventy-seventh birthday that ‘I could have done much better’. Gadzekpo's quest for self-improvement propelled him at different moments to combine work with studies, enrolling as a private student to earn a Cambridge School Certificate, a certificate from Victoria College of Music, and the London Matriculation. Crowning his educational achievements was his graduation from the Ghana School of Law at sixty-four years of age.

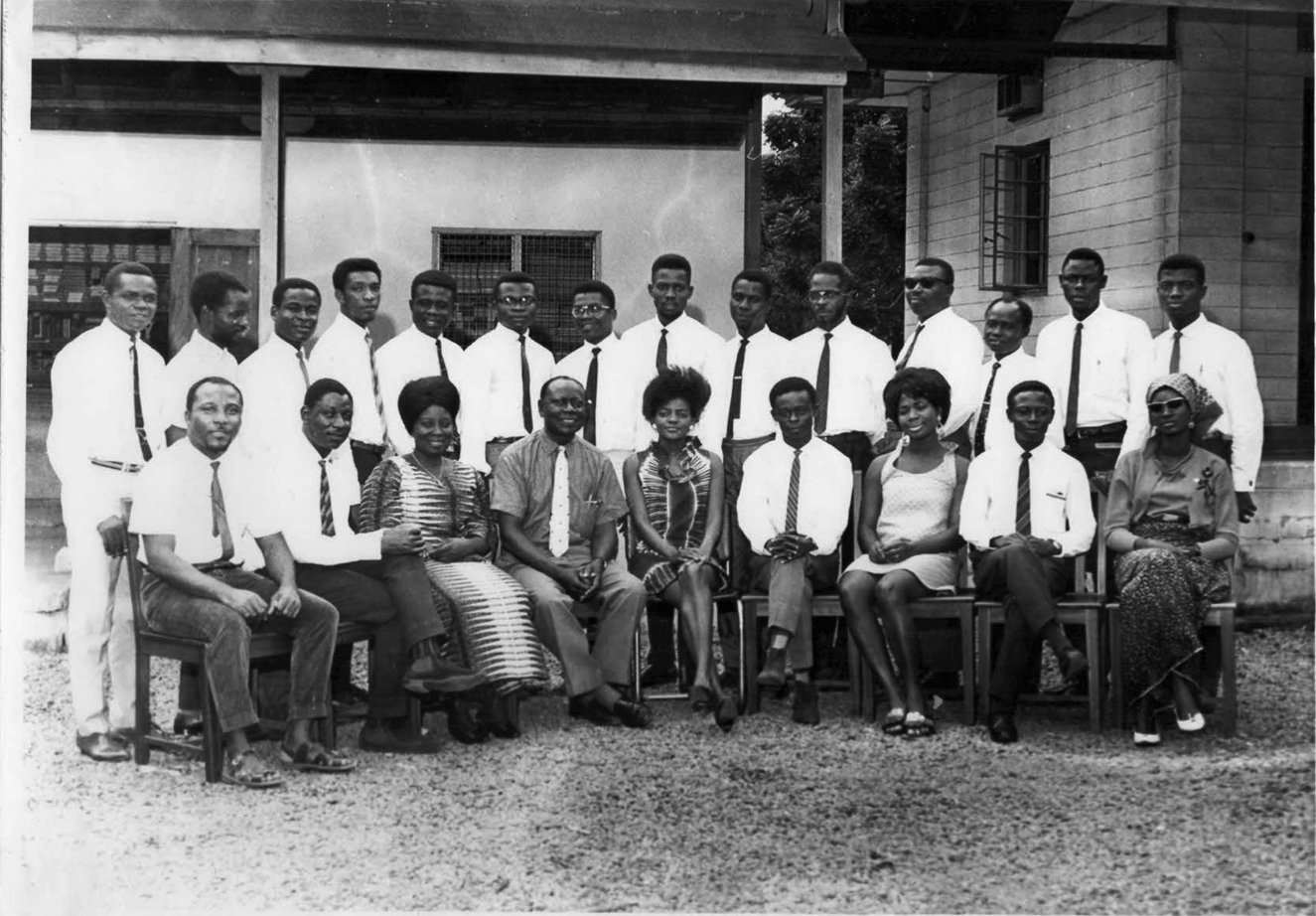

Gadzekpo's career track record reveals the same fortitude. Five years after he joined Station ZOY he won a scholarship to train in radio programme production technique at the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) and in linguistics at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), University of London. Upon his return he was appointed as programme assistant in the Broadcasting Department and rose through the ranks to become Controller of Programmes at GBC before attaining the mandatory retirement age of sixty in 1965. So valued was his experience that he was contracted to assist in the training of programme personnel, having helped to establish the Programme Training School in the first place (Figure 2). This extended his broadcasting career for another six years, until 1971.

Figure 2 Gadzekpo (fourth from left) with colleagues at the Training School in 1968.

A man of varied interests and talents, Gadzekpo's hobbies ranged from writing, sketching and drawing building plans to playing the harmonica and listening to classical music.Footnote 7 He was quoted as observing in a letter to a friend that ‘sometimes I think I am a gifted artist; at another it seems I could have done better as a lawyer; at other times it seems I have missed the profession of a surveyor, or an architect, or an educationist’.Footnote 8

Although he was unable to publish his autobiography and radio memoir, Gadzekpo's contributions to cultural and intellectual life did not go unnoticed in his lifetime. The biography read at his funeral narrated how he had been asked by a publisher who admired him to provide his life history and a photograph to be included in a compilation on local ‘celebrities’, but he had declined, reasoning that:

Much as I would wish my life history to be read, I have often thought that the monument of a ‘celebrity’ should be erected not in his lifetime but after his death by his admirers. Recent events in our country have shown that those whose praises amount to ‘Hosanna to the son of David’ regret in the end when the very voices which sang their praises change the tune to ‘Crucify him, crucify him.’ If I deserve a monument it would be a greater honour for me if it is erected in my death than in my lifetime, to be demolished before my very eyes.Footnote 9

It is not exactly clear when the offer to celebrate Gadzekpo in print was made and what motivated his refusal. Modesty could be a reason, but his reticence could stem from the socio-political instability of the times and the complexities of his work environment. GBC was complicit in the making and unmaking of governments. Starting with the 1966 coup d’état against Kwame Nkrumah, through a series of military coups in 1972, 1979 and 1981, the studios of GBC were always taken over by coup plotters and the national broadcaster was compromised into producing new narratives that vilified overthrown governments, while legitimizing new ones. Unlike other Akropong-trained contemporaries who were involved in the Ablɔɖe (‘freedom’ in Eʋe) political movement (Skinner Reference Skinner2015), Gadzekpo steered clear of politics and weathered the political storms of Ghana quite well.

A note on the manuscript

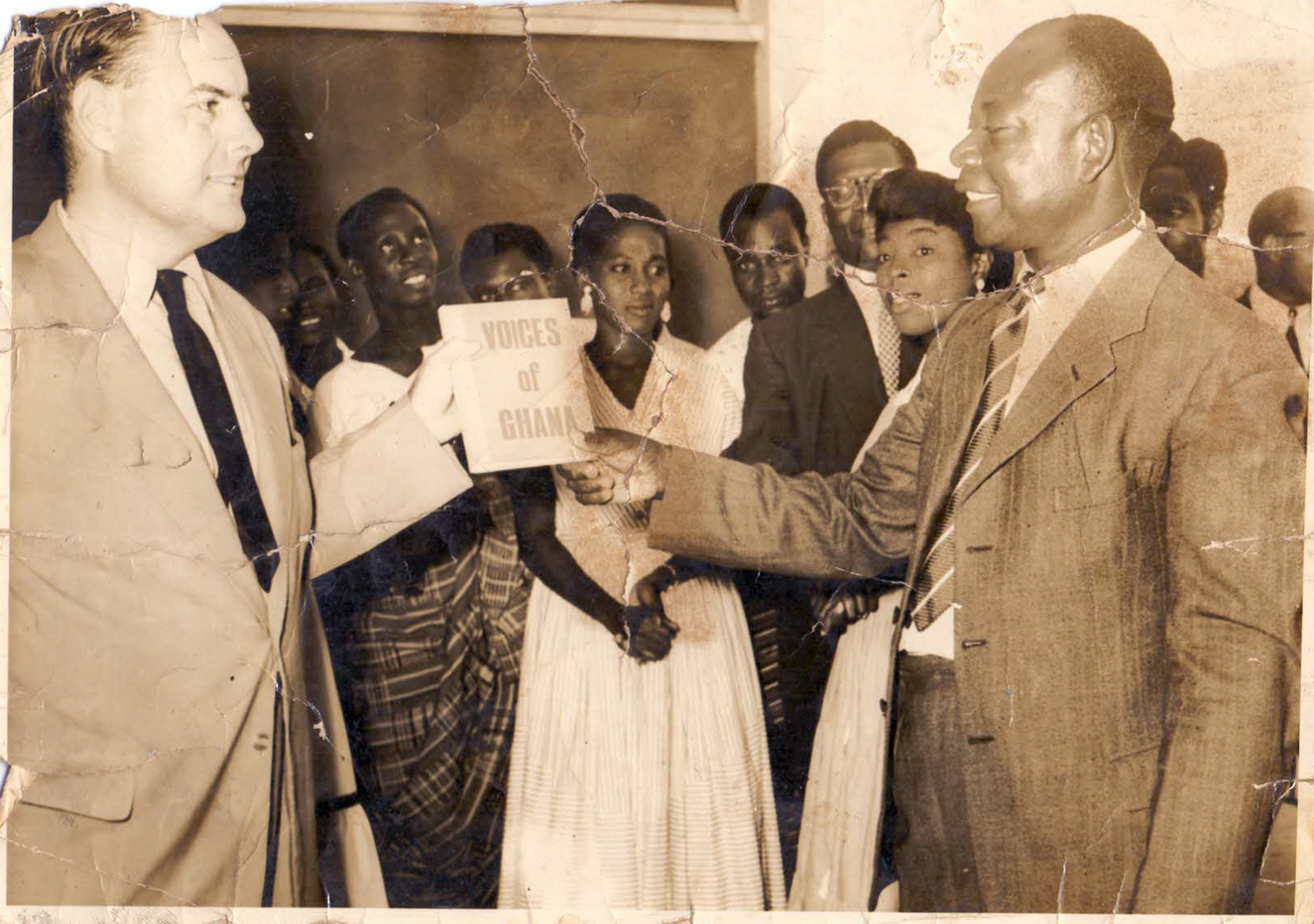

It remains unclear why, after completing this historical account of life in the service of broadcasting, Gadzekpo was unable to publish the memoir before he died some seventeen years later. Correspondence between him and his former boss, Henry V. L. Swanzy, reveals that he had made efforts to get the manuscript published as far back as 1972. Gadzekpo worked closely with Swanzy, who was Head of Programmes at the then Gold Coast Broadcasting Service from 1954 to 1958, following secondment from the BBC (Figure 3). They maintained contact even after Swanzy returned to England to work for the External Services division of the BBC; in a letter dated 23 June 1972, Gadzekpo briefed Swanzy on his retirement from the GBC in 1965 and his new role in training. He also revealed that he was writing a manuscript on broadcasting in Ghana and asked Swanzy to vet the chapter he had written on staff who had been seconded from the BBC to Radio Ghana in the mid-1950s.Footnote 10 Swanzy promptly responded a week later promising to read the chapter and asking if Gadzekpo had found a publisher for the manuscript. A subsequent letter dated 19 August 1972 provided the needed feedback on the manuscript with Swanzy noting that he had ‘ventured to sub-edit here and there’, had toned down ‘too much attention paid’ to him (Swanzy), and had corrected a few factual details. He also advised that the tone of the manuscript was ‘a little too modest and impersonal’, and that what Gadzekpo had written was the story of his life so he ought to bring in ‘more personal things’. He recommended Heinemann Educational as a potential publisher on account of its track record with African writers.Footnote 11 Gadzekpo's response, dated 28 October 1972, explained his preference for a local publisher for two reasons – cost and patronage. He rationalized that he would face economic difficulties publishing with Heinemann, which was UK-based, because of foreign currency controls that would make the book more expensive. He also argued that because the book would be better patronized in Ghana, a local publisher would be preferable. The letter said that the book would be about 150 pages long when published, with fourteen chapters and about a dozen photographs, including of Swanzy and some of his other colleagues.Footnote 12

Figure 3 Henry Swanzy presenting the book Voices of Ghana to B. S. Gadzekpo in 1958.

This exchange confirms Gadzekpo's commitment to seeing his book in print and hints at the precarious nature of publishing during that period – perhaps the reason why he failed to keep a promise to GBC colleagues ‘to set down his 28 years’ experience in broadcasting in the form of a book’ (Gadzekpo Reference Gadzekpo1972).

I found three slightly different versions of a completed manuscript, each with a few missing pages and handwritten edits, each placed within a cover illustrated with a drummer beating talking drums and framed within a map of Ghana. The covers bore the title ‘Ghana muntie: from Station ZOY to the Ghana Broadcasting Corporation’ and the author's name – B. S. Gadzekpo (Figure 4). ‘Ghana muntie’ roughly means ‘Ghana, listen’ in the Akan language. It was the signature tune to news programmes performed in the language of talking drums. Station ZOY was the name of the first relay radio station established in 1935 by Sir Arnold Wienholt Hodson with the call sign ZD4A. Hodson – the Sunshine Governor – was governor of the Gold Coast from 1934 to 1941 but gained his nickname from Sierra Leone, where he had been governor from 1930 to 1934, and established West Africa's first radio station.

Figure 4 Cover of ‘Ghana muntie’.

The manuscript covers the years 1935–72, with 202 typewritten pages comprising sixteen chapters, not fourteen, as Gadzekpo had indicated in his letter to Swanzy. The preliminary sections include a note about the author and a foreword by Eric Adjorlolo, then Deputy Director-General of the GBC. Adjorlolo noted that the only written material on the GBC at that time were various pamphlets and official documents which, in terms of the history of the broadcasting service, ‘only scratched the surface of the medium’.

The arrangement of chapters in the memoir signposts historical events in the life of Ghana, watershed moments in the history of the broadcasting system, and the practices that gave them public meaning. The first chapter – ‘How it all began’ – focuses on Governor Hodson and Frank Byron, his radio engineer. The two worked together in establishing radio in the Falklands in 1929 and in Sierra Leone in 1934. It also provides technical details on the broadcast infrastructure and hardware used in the installation and transmission of Ghana's first radio relay station (Figure 5).

Figure 5 The second Broadcasting House (BH2), built in 1939.

World War Two was central to the memoir. In five chapters, starting with Chapter 2, titled ‘Wired broadcasting service before the war’, Gadzekpo discusses the first four years of radio and the relay of BBC programmes in ‘the pre-war days’. Although the word ‘war’ does not appear in the title of Chapter 3 on ‘The beginning of the Information Department in Ghana’, the chapter contains information on the secondment of Gold Coast teachers and Hausa teachers from Northern Nigeria to help broadcast as part of the war effort. Chapter 4, ‘Programme content during the war’, details on-air content during World War Two, including news in English and Ghanaian languages and ‘talks on some aspects of the war’. The war theme is further expanded in Chapter 5, with the captivating title ‘Battles at the microphone’, in which Gadzekpo describes the diverse ways in which he and his colleagues made their mark on wartime programming on Station ZOY. Chapter 6 completes the war theme, as suggested by the title ‘End of the war and return to civilian life’.

The rest of this autobiographical account covers other developments in his life and radio in Ghana, including a chapter titled ‘Training at the BBC’ (Chapter 7) that chronicles his learning experiences at the BBC and at SOAS and his promotion to programme production upon his return from the UK. He also devotes a chapter (Chapter 8), ‘Music talent hunt’, to his favourite subject – music – in which he details the challenges of identifying and recording indigenous music to play on air in order to keep local audiences glued to the radio after the war. Chapter 9 provides invaluable information on the setting up of a Broadcasting Commission in 1953, chaired by John Grenfell-Williams, which led to the appointment of James Millar as the first Director of Broadcasting and the separation of the station from the Public Relations Department, as well as the building of a new Broadcasting House (Figure 6). Chapter 10 captures the immediate post-independence period, during which an external radio service and a television station were established, and radio sets known as Akasanoma (talking bird) were assembled locally.

Figure 6 The third Broadcasting House (BH3), built in 1957.

Chapters 11, 12, 13 and 14 provide insights into the post-independence evolution in broadcasting in response to social change, including the commercialization of the radio and television service in 1967, the hiring of women news announcers, recruitment of local personnel, the launch of the first broadcasting journal, Ghana Radio Review and TV Times, and expansions in programming, particularly entertainment and local-language programmes. In the penultimate Chapter 15, he focuses on the pervasiveness of radio in the lives of Ghanaians and reflects on almost four decades of broadcasting, the penetration of radio ‘into every nook in the Ghanaian forest’, and its wide-ranging impact on the contemporary lives of Ghanaians. The chapter also discusses radio's role during momentous occasions such as Ghana's day of independence on 6 March 1957 and elections in the country, as well as radio's ongoing education and entertainment mission.

The concluding Chapter 16 pays homage to the professionalization, indigenization and expansion of Ghana's national broadcaster over the years. Titled ‘Self-reliance’, it paints a portrait of a corporation staffed by 4,000 behind-the-scenes and on-air personnel, who since independence continued the work of developing a Ghanaian image for the service through their programming.

Making meaning of ‘Ghana muntie’

Two overarching themes stand out from Gadzekpo's memoir. The first is the contribution and agency of endogenous broadcasters in the early development of radio in Ghana. Of particular importance is how the memoir brings to the fore an overlooked group of media professionals known in the colonial period as Vernacular Announcers (VAs). Gadzekpo pays attention to their remarkable role in meeting early demands for indigenizing a medium essentially designed to advance colonial administration (Matheson Reference Matheson1935). The second is the role World War Two played in shaping the neophyte radio station and the ways in which the local staff supported the war effort through their ingenuity and devotion to radio work.

Radio histories on former British colonies have tended to focus attention on the role of the BBC in the formation of radio culture in Africa (Head Reference Head1979), scarcely dwelling on the part played by local stations such as Station ZOY and the significant contributions of broadcasters who shaped local programming and built African listenership during the colonial period. Written accounts and archival material on radio's early beginnings in Ghana leave no doubt that it was essentially meant to serve as a political and ideological instrument of colonial control (Head Reference Head1979; Karikari Reference Karikari, Barratt and Berger2007; Smyth Reference Smyth, Bloom, Miescher and Manuh2014; Akrofi-Quarcoo and Gadzekpo Reference Akrofi-Quarcoo and Gadzekpo2020). Thus, in the beginning and throughout much of the colonial period, programmes emanated from the Empire Service and the BBC. The speech of Governor Hodson during the launch of Station ZOY on 31 July 1935, portions of which are quoted in Gadzekpo's memoir, reveals the ‘civilizing’ intent of radio (Matheson Reference Matheson1935). Hodson's speech positioned radio as a tool for cultural enlightenment, education and entertainment, as can be discerned from his assertion that:

the new Broadcast Service opens up a new vista of life to all of us who live in Accra … It brings the latest news to our doors. It is very similar to the magic stone we read of in fairy tales – we press a button and are transported to London. Again, we press it and hear a grand opera from Berlin. In fact, nearly the whole world is at our beck and call. You can imagine what an influence this will have from a psychological point of view. Mothers, when the children have been fractious, or when they have had a trying day – cooking and washing clothes, or men who have had a hard day's work, will sit down and listen to first class music which will banish their cares and make them forget all their worries … This reception … concludes with orchestral music from London and any important speeches which are being made by Cabinet Ministers and others at official lunches in England. (Gadzekpo Reference Gadzekpo1972)

Malcolm MacDonald, the Secretary for the Colonies, broadcasting from London to mark the occasion (also quoted in Gadzekpo's memoir), reflected a similar position by assuring Gold Coasters that radio:

would allow you to enjoy the Empire Programmes from Daventry, which the BBC are so far-sightedly maintaining and developing, and also to keep in closer and more immediate touch with what is going on generally in this country and elsewhere in the world. Perhaps, not least important, it will enable you at times to take part with us here in great and moving occasions, such as when His Majesty the King delivered his recent Jubilee Broadcast. These occasions bring home to us the real and intimate community which exists between all the peoples over whom His Majesty reigns. Broadcasting has made it possible for us to get a more vivid impression of that. (Gadzekpo Reference Gadzekpo1972)

Accounts of radio's rapid development following its launch, as described in Gadzekpo's memoir and some of the extant literature (Bourret Reference Bourret1960; Ansah Reference Ansah1985; Holdbrook Reference Holdbrook1985), credit Hodson for his ambitious vision of expanding radio in Ghana right from the start. Even though Gadzekpo did not join the station until seven years after it was established, he includes the early days of radio in his accounts and Hodson's astute recognition of the immense advantage radio held for a society that was mostly oral and in transition. According to Gadzekpo, Sir Arnold dreamed of extending radio to the remotest villages and towns through overhead wires. While this ambition was not immediately achievable, it is instructive that as many as sixteen wired broadcasting stations were opened within four years of radio's introduction to Ghana. Thus, by the time Britain declared war on Germany in 1939, radio already had local audiences and a growing subscriber base. Seven wired broadcasting stations were opened a year before the war, four of which were located in towns that produced wartime raw materials such as bauxite, a fact not lost on Gadzekpo, who speculated that the speed with which radio was expanded in the Gold Coast may have been related to the threat of war and demands from the Provincial Headquarters for radio services.

The memoir confirms other historical accounts of the quick uptake of radio by the local population and the cultivation of radio listenership during the war. According to Gadzekpo, it was the ‘exciting news of the war relayed by the sixteen wired relay stations in existence … that whetted listeners’ appetite for listening’. He observed how there was a significant jump in subscriptions from 350 in 1935 to 4,000 when the last station was opened in 1939. Scholarly estimates suggest that, by the end of the war, radio subscriptions had increased to between 5,850 (Ansah Reference Ansah1985) and 6,045 (Holdbrook Reference Holdbrook1985). During World War Two an estimated 65,000 Gold Coast men served in various services of the British colonial military (Bourret Reference Bourret1960), so naturally there was great demand for news of the war from the local and expatriate communities in the Gold Coast. In an article published in the radio review of the Ghana Broadcasting Service (GBS), Kobla Senayah, who, like Gadzekpo, was an Eʋe VA, observed that the broadcasting service was important ‘to keep the public informed of the day-to-day happenings of the war’ and to provide news of Gold Coast soldiers who were posted to Burma.Footnote 13 In 1940, Station ZOY was provided with a bigger 1.3-kilowatt transmitter to boost the reach of the station, but this soon proved inadequate to cater for wartime information needs. In 1942, a new 5-kilowatt transmitter was installed, allowing the radio station to reach other African countries, especially Congo, where the Free French forces were stationed.

Access to news and information was also extended beyond those who subscribed to the service; similar to what occurred in Nigeria (Larkin Reference Larkin2008), loudspeakers were rigged to radio sets located in collective reception points such as community centres, markets, shops, lorry parks and newly established information bureaus around the country. In a contribution to the Radio Review to mark twenty-five years of radio, Gadzekpo reminisced on how every afternoon people flocked to information bureaus to listen to broadcasts on war news in the local languages.Footnote 14 He credited these bureaus as instrumental in forming radio listening habits and providing VAs with feedback, enabling them to better serve audience needs. His reflections in that article and in his memoir also bear testimony to the efforts of on-air and behind-the-scenes local staff in adapting wartime content to suit the tastes of Ghanaian audiences and rallying their support for the British war effort. During and after the war, it was local broadcasters who held listeners’ attention by inflecting their programmes with culturally relevant anecdotes, jokes and analogies. Gadzekpo contends that, on account of the varied roles they played, it was misleading to describe VAs as mere translators of news. He argued that a better characterization would be as interpreters of news and events, whose job it was to explain happenings to their people in languages they could understand. Since colonial administrators seldom learned local languages, and similar to other African intermediaries working in the colonial bureaucracy, such as clerks and court translators and recorders (Lawrance et al. Reference Lawrance, Osborn, Roberts, Lawrance, Osborn and Roberts2006), VAs were the cultural brokers who acted as intermediaries in the colonizer's interactions with local radio audiences.

It is important to note that the first VAs were employed before the war to translate news from the Empire Service extempore into four principal Gold Coast languages – Twi, Fanti, Ga and Eʋe – for no more than five minutes for each language per day. It was a part-time job at the time and the announcers were mostly full-time teachers. The first batch of VAs were: Mr Kwame Frimpong, a teacher at Government Boys School who was responsible for Twi translations; Mr Wilson, a teacher at the Royal School in Accra for Fanti; and Mr E. W. Adjei, a chief clerk, for Ga. The Reverend Christian Gonzales Baeta, who became Professor Emeritus of the Study of Religions at the University of Ghana, was in charge of Eʋe. Gadzekpo and his colleague Senayah took over Baeta's role three years into the war when a second wave of VAs were employed and seconded to the newly created Information Department. Like Gadzekpo, all ten VAs employed in 1942–43 were experienced and respected certificated teachers. They worked in pairs and were responsible for the four local languages already being broadcast by their predecessors, as well as Hausa, an additional language introduced during the war. Hausa is not an indigenous Ghanaian language but was widely spoken then as it is now as a kind of lingua franca in northern parts of the country and in zongos (areas mostly populated by settlers from the northern Sahel). Hausa became an important language of broadcast because of the high percentage of its speakers from neighbouring countries such as Burkina Faso (then Upper Volta) and Nigeria, who were conscripted into the Gold Coast and West African Frontier Force (WAFF) armies.

Holdbrook (Reference Holdbrook1985) maintains that the Gold Coast was the centre of Britain's biggest propaganda initiative in West Africa and that colonial authorities believed effective propaganda among the local population could only work if Africans themselves relayed the information. Smyth (Reference Smyth, Bloom, Miescher and Manuh2014) has also argued that, especially after British defeats in Singapore and attempts to discredit the ideology of imperialism by Germany, mass media such as radio and film became even more important for securing the loyalty of colonial subjects and persuading them that they too stood to lose if Britain were defeated. Gadzekpo's narratives give credence to this, although nowhere in the manuscript did he concede that they were part of the propaganda machinery. Nonetheless, his retelling of what he termed the ‘battles at the microphone’ illuminate how, by carefully selecting news that showed only the progress of the war and accentuating British victories in battle, they were in effect propagandizing.

The memoir also documents how they successfully mobilized the citizenry through wartime talks and appeals for funds in aid of various war charities. The following extracts from the sample text illustrate some of their efforts:

Local news items dealt specifically with the war effort, and in this, we the Announcers were proud that we fought out battles at the microphones. We kept on encouraging the farmers to grow sufficient food, as imported food was no longer available due to the war. We did succeed in this, for there was no serious food shortage in the country during the war.

Our announcements encouraged people in the big towns to contribute to the Spitfires Fund,Footnote 15 which was ably organized by Mr. F. A. B. Johnson, Spitfirehene,Footnote 16 who did not live long to see the effect of the Spitfires on the enemy. Through his enthusiasm, concerts, dances and other activities were organized to raise funds to purchase the aircraft.Footnote 17

In addition to fundraising for the war, VAs found innovative ways to bring war news to their people and consequently were able to cultivate new radio audiences. Twice each week they would broadcast talks on war strategy or weapons, translated from ‘special scripts on the war’ that came from London, or from content they themselves had originated. By translating war terminology and coining new words, they also built the stock of local vocabulary on war. It was in the art of translation and in writing their own talks in those early years that they started indigenizing radio and showcasing their ingenuity. An example of this was a wartime talk Gadzekpo broadcast to encourage listeners to support the war titled ‘Learning from nature’; this drew on the cooperative spirit of ants working together to achieve a common purpose. The animal kingdom also provided VAs with suitable analogies with which to demonstrate how weaponry such as tear gas worked. According to Gadzekpo, ‘[I]t was explained with the behaviour of the puff adder and some other snakes, which squirt poisonous liquid substances into the eyes of their enemies, temporarily blinding them and so enabling them to escape.’

As in all situations of conflict, rumour-mongering was a constant source of concern. During the war, colonial authorities feared that rumours and myths about Germany's military would undermine their efforts (Smyth Reference Smyth, Bloom, Miescher and Manuh2014), so VAs were expected to avoid rumours and dispel them among the populace. Unlike their predecessors, therefore, they were not allowed to broadcast extempore, and so they became skilled translators of English news scripts into their respective local languages. These practices and techniques of translation, some of which are described in Gadzekpo's co-authored manual on the principles of translation, laid the foundations for professional norms relating to local news at the GBC. As Gadzekpo explained, he and his colleagues were aware that they were ‘setting standards’ and ‘contributing directly or indirectly to the development of their languages’.

John Wilson, who rose to the position of head of the Information Department, under whom Gadzekpo worked, validated this claim in a reflective piece titled ‘Those first days of broadcasting’, in which he observed that:

the highest highlight of the last twenty-five years in Ghana broadcasting was the founding and developing of these African language broadcasts, including the work of those news reporters … It meant, in fact that in Ghana there developed a truly indigenous broadcasting, somewhat different from broadcasting anywhere.Footnote 18

Conclusion

The corpus of writings B. S. Gadzekpo produced in his lifetime leads us to conclude that he was one of Ghana's tin-trunk literatiFootnote 19 (Barber Reference Barber and Barber2006), who used his literary skills to assert his culture and document his personal experiences in an attempt to be faithful ‘to history and memory’ (Coates Reference Coates2016: 375). Through ‘Ghana muntie: from Station ZOY to the Ghana Broadcasting Corporation’, he succeeds in situating VAs firmly ‘in the frame of African history’ (Killingray Reference Killingray2010: 6), reminding us that significant actors have been glossed over in historical texts. As Gadzekpo asserts, these pioneers of radio ‘were in [their] own way journalists, playwrights, producers at one time, and artistes at another’. The picture of World War Two Gadzekpo paints, and the memories he shares of his colonial and postcolonial experiences, should invite us to question the complexities of radio's trajectory in Africa and the need for closer scholarly attention to the histories of local-language broadcasting. Importantly, this unpublished manuscript should encourage us to keep digging through our old cupboards and tin trunks in hopes of finding material that would nuance our personal and public histories and make them more complete.

Supplementary material

The complete manuscript, ‘Ghana muntie: from Station ZOY to the Ghana Broadcasting Corporation’ by Bernard Senedzi (B. S.) Gadzekpo is available with this article at <https://doi.org/10.1017/S0001972021000012>.

Acknowledgements

I am indebted to the AfOx-ASC fellowship, which allowed me to spend time at the University of Oxford to complete writing this article. I also thank Confidence Gadzekpo, who gave me access to his father's unpublished manuscript and other papers.