Introduction

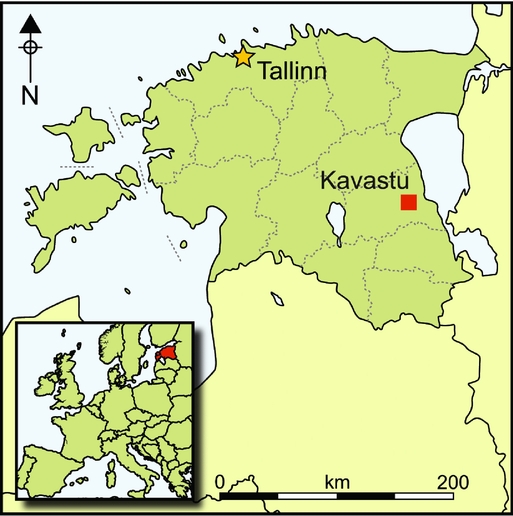

Imported goods have attracted the attention of scholars for many years. They indicate the directions and intensities of foreign contacts as well as concepts of value and prestige in the past. Well-known examples are the imports from Rome found beyond the limits of the Empire, especially in Northern Europe. The archaeological evidence for such goods and contacts across Europe is not evenly distributed, and differences between regions are considerable. While some areas, such as Scandinavia and Central Europe, provide an abundant record of Roman imports, others, such as the northern regions of the Baltics, clearly lie on the periphery of the Empire, and significantly fewer examples have been recorded. In this context, a unique group of bronze objects comprising a Roman lamp and four pieces of bronze deposited in a peat bog in Kavastu (Estonia) was investigated to address questions of the biography, function and chronology of imported goods in peripheral regions.

Igor Kopytoff's (Reference Kopytoff and Appadurai1986) ground-breaking paper on artefact biographies has for decades influenced scholars dealing with the life-history of archaeological objects and sites (e.g. Bradley Reference Bradley1990; Holtorf Reference Holtorf1998, Reference Holtorf2002; Gosden & Marshall Reference Gosden and Marshall1999; Fontijn Reference Fontijn2002; Joy Reference Joy2009). Several previous studies have emphasised the long-term use of rare, foreign and prestigious luxury items (Lillios Reference Lillios1999; Härke Reference Härke, Theuws and Nelson2000; Whitley Reference Whitley2002; Eckhardt & Williams Reference Eckardt, Williams and Williams2003), and the importance of reconstructing the biographies of hoarded objects to provide more nuanced and better substantiated interpretations of those finds (Lund & Mellheim Reference Lund and Melheim2011; Hall Reference Hall2012; Dietrich Reference Dietrich2014). These studies have widened our understanding of the processes behind creating and collecting valuable objects, their origins and life-cycles. They have raised questions regarding the internal chronology of the objects deposited together, and also the potential for multiple functions and meanings within material culture in general.

Several scientific methods were combined in order to create a biography for the Kavastu bronze lamp, and to develop a more robust interpretation for this find in the context of the eastern Baltic Iron Age. The results show that an analysis that relies purely on the chronology and typology of imported goods omits important information that contributes to the final interpretation of the find, and traditional approaches to such artefacts can be misleading. We demonstrate the relevance of multidisciplinary analysis in material culture studies, particularly for rare items with few local archaeological parallels.

The Kavastu bronze lamp and its parallels

The Kavastu bronze lamp was first described and published by Richard Hausmann (Reference Hausmann1905). It is a large bronze lamp with two nozzles and volute decorations (Figure 1), weighing 1245g. Two fragments of possibly Roman objects (lamp-stands?) and two bronze bars, perhaps raw material, were found with the lamp.

Figure 1. The Kavastu bronze deposit: a Roman lamp and four bronze bars, with a close-up of the analysed residue in situ.

The deposit was recovered during peat-cutting around 1m deep on the bank of River Emajõgi in Kavastu (Kawwast) (Figure 2), southern Estonia in 1902 (Hausmann Reference Hausmann1905). The initial description of the discovery notes several animal bones in the area, although it is specifically reported that recognisable human bones were not observed.

Figure 2. The nineteenth-century map of Kavastu (EAA1384-1-12-1. Планъ имения Кавастъ, map from the Estonian National Archives) on an Estonian Land Board relief map with a contemporary peat cutting area (торф ями in Russian) marked in red.

Similar lamps have been recovered from Pompeii and Herculaneum (Valenza Reference Valenza and Annecchino1977: 159, tab. LXXII: 8; Conticello de’ Spagnolis & De Carolis Reference Conticello De’ Spagnolis and De Carolis1988: 41–45, tab. 3), including in and around the destruction layer of AD 70–79. Parallels are also known from the first-century BC Mahdia shipwreck, discovered in the waters of Tunisia (Fuchs Reference Fuchs1963: 30, tabs 43–44; Parker Reference Parker1992: nos 621, 252). Most of these examples have a handle, and sometimes also a short stand attached to the bottom. According to Conticello de’ Spagnolis and De Carolis (Reference Conticello De’ Spagnolis and De Carolis1983: 16–17, Reference Conticello De’ Spagnolis and De Carolis1988: 41), such lamps were in use in the Roman Empire until at least the second century AD. Bronze lamps were, however, luxury items, even in the Roman Empire where clay lamps were more commonly used. Bronze exemplars were rare, expensive, used on special occasions and for much longer periods, especially north of the Alps (Goethert & Werner Reference Goethert and Werner1997: 182). Two very similar (although slightly smaller) lamps are known in Central Europe, in Moravia (Czech Republic), a stray find at Bílovice near Kostelec; and a second listed in a burial inventory in the princely grave at Mušov (Schránil Reference Schránil1928: 268, tab. LV: 18; Droberjar Reference Droberjar2002: 114–15, 192; Tejral Reference Tejral, Friesinger and Stuppner2004: 339). Besides the Kavastu lamp, no other Roman bronze lamps have been found either in Scandinavia or in the Baltic countries.

Imports from Rome in Northern Europe

Imports from Rome are not rare in Northern Europe. Scandinavia, especially its southern regions, has an abundance of material of both Imperial and provincial Roman origin, from jewellery to coins, and glass and metal vessels (Eggers Reference Eggers1951; Lund Hansen Reference Lund Hansen1987). These places were clearly in direct and indirect contact with the Romans. This is also indicated by written sources and the presence of Roman goods in famous Scandinavian ‘booty’ deposits (Ilkjær Reference Ilkjær2000; Jørgensen et al. Reference Jørgensen, Storgaard and Thomsen2003).

The situation is somewhat different in the eastern Baltic. Poland and Lithuania were important to the Roman Empire due to the amber trade, but also due to their proximity to Roman activities (Bursche Reference Bursche1992; Michelbertas Reference Michelbertas2001; Bliujienė Reference Bliujienė2011; Zapolska Reference Zapolska and Holmes2012). Thousands of coins and other Roman and provincial goods have been found in these regions, but the density of finds decreases significantly towards the north. Around 500 Roman coins were found in Latvia with four certain coin hoards (Ginters Reference Ginters1936; Urtāns Reference Urtāns1977: 133–37; Ducmane & Ozoliņa Reference Ducmane and Ozoliņa2009). In Estonia, the majority of imported items are gold foil and glass beads (Lang Reference Lang2007: 257); very few sites have Roman bronze goods. Around 100 Roman coins have been discovered in Estonia, with three certain coin hoards (Kiudsoo Reference Kiudsoo2013). In Finland, only 20 coins are recorded, with three bronze drinking vessels (Eggers Reference Eggers1951: 158, nos 2256–58; Kivikoski Reference Kivikoski1961: 117; Talvio Reference Talvio1982; Salo Reference Salo, Laaksonen, Pärssinen and Sillanpää1984: 218–19).

In this context, the discovery of a Roman bronze lamp in Estonia is remarkable. The closest find in terms of function is a simple, single-nozzled clay lamp from Kapseda in Latvia (Ginters Reference Ginters1936; Moora Reference Moora1938: 586–87, fig. 86). Other than these two, there are no prehistoric oil lamps in the eastern Baltic archaeological material, except the shallow, ceramic bowls from the Stone Age known as `blubber lamps'. Thus, the Kavastu bronze lamp is unique: it is the only such find in the Baltic Sea area and the largest single Roman bronze object in the north-eastern Baltic.

The existing biography for the Kavastu lamp

Lamps similar to that from Kavastu were made and used in the Roman Empire from the late first century BC to the second century AD. Taking this as a terminus post quem, the lamp might have been deposited after the first–second centuries AD. This would, however, dismiss long-distance trade networks and long-term (re-)use of objects over vast geographic and cultural distances, which make correlating the time of production with final deposition problematic.

In consultation with Adolf Furtwängler, Hausmann (Reference Hausmann1905: 65) identified the lamp as an Imperial product, made in the first century AD, in the region that is now Italy. Chemical analysis of the metal content of the lamp and three of the bars indicated that each item originated from different artefacts, due to considerable variations in alloy content (Table 1). Hausmann noted problems with the chronology of the deposit, arguing that the alloy contents of the bronze bars, especially their high lead content compared to local material in use from the second half of the first millennium AD, show that some of the objects might belong to a much later period, perhaps even to the turn of the second millennium AD (Hausmann Reference Hausmann1905: 68–73).

Table 1. Alloy content of artefacts in the Kavastu bronze deposit (after Hausmann Reference Hausmann1905: 68–69).

Despite Hausmann's conclusions, the find was discussed in the context of the Roman Iron Age (AD 50–450) in all subsequent archaeological publications (Moora et al. Reference Moora, Laid, Mägiste and Kruus1936: 93; Jaanits et al. Reference Jaanits, Laul, Lõugas and Tõnisson1982: fig. 159; Lang Reference Lang2007: 257). The lamp was regarded as an example of a Roman import: a manifestation of foreign contacts with the northern periphery during the Roman Iron Age. This somewhat superficial scholarship relied on the artefact-based chronology of the lamp, ignoring Hausmann's analysis.

Further scientific analysis: enriching the biography

The Kavastu deposit was the subject of renewed research focus in relation to a PhD project (Oras Reference Oras2015). When the hoard was discovered in 1902, the Estonian territory was part of the Tsarist Russian Empire. Despite being discovered in Estonia, after initial study the find was sent to the Riga Dome Museum in Latvia, and later to the National History Museum of Latvia, where it is now stored. No detailed records concerning the cleaning, conservation, storage or display of the lamp have been identified. On first inspection of the lamp, it was evident that fuel residue remained intact in the nozzle, providing an opportunity to obtain new insights into the life-cycle of the lamp and its relationship with the bronze bars. When and where was the lamp last used for lighting? What is the residue used as a fuel and is it of northern origin? What is the date of the deposition and does it coincide with the artefact chronology of such lamps? Does the direct dating of the fuel correlate with Hausmann's estimation based on metallurgical analysis?

Residue analysis

The nature of the fuel residue was determined in order to estimate the possible region(s) where the lamp had been used. A detailed analytical protocol is presented in the online supplementary material; a partial gas chromatogram showing the results is presented in Figure 3. The sample is characterised by a narrow, monomodal distribution of n-alkanoic acids ranging from C12 to C22 in carbon number, with an even over odd preference dominated by an n-C16 homologue. Several monounsaturated C18 n-alkanoic acids are also present at a relatively high concentration, and C7–C9 diacids are observed, with the C9 diacid (azelaic acid) present at the highest concentration. The threo- and erythro-stereoisomers of 9,10-dihydroxyoctadecanoic acid elute at 26.0 and 26.4 min, respectively. A trace concentration of 24-ethylcholest-5-en-3β-ol (β-sitosterol) was present (not shown), but no cholest-5-en-3β-ol (cholesterol) was detected. The carbon number distribution of the n-alkanoic acid homologues, combined with the presence of β-sitosterol, albeit at a trace concentration, and the absence of any detectable cholesterol, may be interpreted as evidence of a higher plant origin for the lamp residue (Killops & Killops Reference Killops and Killops2005). The presence of azelaic acid and 9,10-dihydroxyoctadecanoic acid may be explained as oxidation products of octadec-9-enoic acid (most probably oleic acid; Regert et al. Reference Regert, Bland, Dudd, Van Bergen and Evershed1998), indicating that this component would have been present at a much higher concentration (most probably the dominant n-alkanoic acid moiety) at the time of the lamp's use.

Figure 3. Partial gas chromatogram of the trimethylsilylated lipid extract from the fuel residue from the Kavastu bronze lamp. Free n-alkanoic acids are denoted by filled circles, with x:y giving the carbon chain length x and degree of unsaturation y.

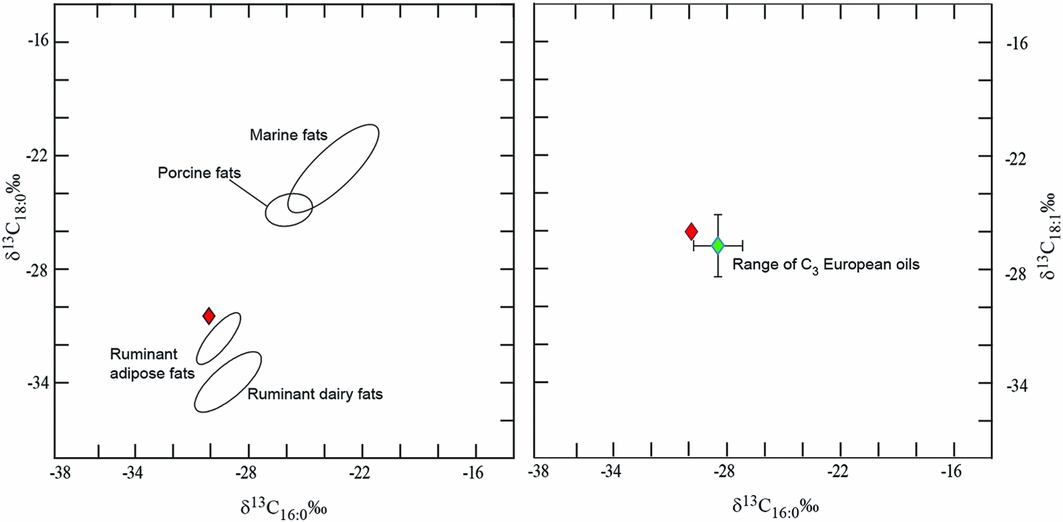

The analysis of the stable carbon isotope signature of single n-alkanoic acids supports the interpretation of a plant-oil-derived fuel for the lamp, with values of C16:0 against C18:1, being consistent with ranges obtained for a range of European C3 oils (Figure 4; Woodbury et al. Reference Woodbury, Evershed and Rossell1998).

Figure 4. Plot of δ13C values of C16:0 against C18:0 (left) and C18:1 (right) n-alkanoic acids, with the plot on the right showing the range of European C3 oils (Woodbury et al. Reference Woodbury, Evershed and Rossell1998) with the Kavastu results marked with red diamonds.

Radiocarbon dating

AMS dating was carried out by the Oxford Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit with two main aims: i) to estimate the date of final use of the lamp and a terminus post quem for its deposition; and ii) to compare the 14C date of the lamp residue with estimations of the date of deposition based on Roman artefact typology and chronology, and with metallurgical analysis presented by Hausmann.

We dated two bulk samples of the carbonised residue and the total lipid extract solvent obtained for the lipid residue analysis. The in situ residue was spatially homogeneous and removed as a single batch from one of the lamp nozzles, later divided into two separate bulk samples. Radiocarbon determinations were obtained using the methods outlined by Brock et al. (Reference Brock, Higham, Ditchfield and Bronk Ramsey2010).

The radiocarbon dates obtained for two bulk samples are presented in Figure 5 and Table 2. Sample OxA-27781 yielded a date of 1561±25 BP, calibrated to AD 427–557 (95.4% probability); sample OxA-32327 provided a date of 1699±33 BP, calibrated to AD 252–410 (95.4% probability). The total lipid extract (OxA-V-2515-13) yielded a much earlier date of 2319±31 BP, calibrated to 430–356 BC (88.4% probability). This discrepant and archaeologically unlikely date is probably due to the insufficient removal of organic solvents (see further discussion in online supplementary material), and cannot date the usage of the lamp for illumination purposes. The two bulk determinations—1699±33 BP and 1561±25 BP—provide a terminus post quem for the deposition of the lamp and the bars.

Figure 5. Calibrated age ranges for the two bulk radiocarbon determinations from the lamp (OxA-27781 and OxA-32327; see data in Table 2). Calibrated using OxCal 4.2 (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2009) and the IntCal13 calibration curve (Reimer et al. Reference Reimer, Bard, Bayliss, Beck, Blackwell, Bronk Ramsey, Buck, Cheng, Edwards, Friedrich, Grootes, Guilderson, Haflidason, Hajdas, Hatté, Heaton, Hoffmann, Hogg, Hughen, Kaiser, Kromer, Manning, Niu, Reimer, Richards, Scott, Southon, Staff, Turney and van der Plicht2013). Range bars are shown at 95.4% probability.

Table 2. Radiocarbon determinations and analytical data for the Kavastu lamp bulk residues. %Yield = pretreated material as a function of the starting weight of the material analysed. %C = carbon present in the combusted sample. Stable isotope ratios are expressed in ‰ relative to vPDB with a mass spectrometric precision of ±0.2‰.

Discussion: a new biography for the Kavastu lamp

The new residue and AMS analyses, in combination with earlier metallurgical studies, make a substantial contribution to reconstructing the biography of the Roman bronze lamp and bars discovered in Kavastu. The lamp is of Roman manufacture, originating in the Mediterranean between the first century BC and the second century AD. The bulk AMS dates indicate that it was used as a source of light for several centuries. We cannot be absolutely certain that the residues analysed reflect different episodes of use separated by several centuries, but they might imply at least two later use-phases for the lamp: around the third–early fifth centuries AD (sample OxA-32327) and around the fifth–sixth centuries AD (OxA-27781). This would support the idea of the long-term use of bronze lamps and their prestige value.

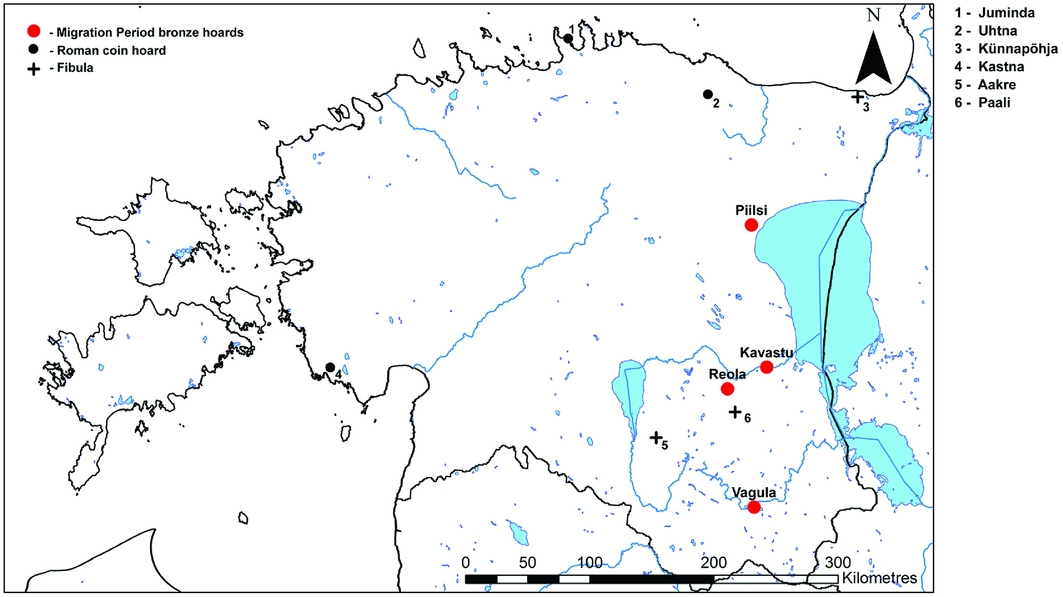

The origin of the fuel residue indicates where the lamp was used for illumination purposes. In the Mediterranean, olive oil was the main fuel used in lamps, potentially with other plant substances or mixed with animal fat (Kimpe et al. Reference Kimpe, Jacobs and Waelkens2001; Colombini et al. Reference Colombini, Modugno and Ribechini2005; Copley et al. Reference Copley, Bland, Rose, Horton and Evershed2005; Garnier et al. Reference Garnier, Rolando, Høtje and Tokarski2009; Steele et al. Reference Steele, Stern and Stott2010), or beeswax (Evershed et al. Reference Evershed, Vaughan, Dudd and Soles1997). In the Kavastu lamp, the fuel was of C3 plant origin, probably olive oil. The importation of olive oil into north-eastern Europe is possible in principle, but we lack any related archaeological finds such as oil amphorae, and there is no identified use of olive oil in any other vessels in the archaeological record. Furthermore, considering that Roman imports are generally rare (mainly glass beads and brooches; see Figure 6), it is unlikely that such a specific commodity as olive oil was imported and indeed used for illumination purposes in this peripheral northern region. Although there are local C3 oil plants available, e.g. flax and hemp, we have no evidence of oil production; their fibres were used in textile production, and, if produced at all, oil was probably consumed as a valuable food substance (Troska & Viires Reference Troska, Viires, Viires and Vunder1998; Moora Reference Moora2007: 23–24, 188–90).

Figure 6. Map of Roman imported bronze goods and Migration Period bronze hoards in Estonia.

Moreover, the Kavastu lamp and previously mentioned Kapseda ceramic example are the only oil lamps known in the eastern Baltic Iron Age. Local archaeological and ethnographic records suggest that the main sources for heat and illumination in the region were the abundant wood resources. The closest comparisons to oil lamps are the considerably earlier Mesolithic and Early Neolithic ‘blubber lamps’—ceramic bowls in which aquatic or terrestrial animal fat was burnt (e.g. Heron et al. Reference Heron, Andersen, Fischer, Glykou, Hartz, Saul, Steele and Craig2013); similar use of such substances for illumination has also been recorded in local ethnographic material (Troska Reference Troska, Viires and Vunder1998: 331–32). The Kavastu lamp, however, had no traces of marine or mammalian substances. The lamp was clearly an alien commodity in the Nordic regions, and was not used for its original purpose; it travelled so far north for different reasons.

The closest similar lamps were found in the south-eastern corner of the Czech Republic in Central Europe, indicating one possible route through which the Kavastu lamp might have travelled to the eastern Baltic via the Vistula River, which connects Central Europe with the Baltic Sea. There are a few other imported goods from around the Vistula in the corpus of Estonian Roman Iron Age material (Jaanits et al. Reference Jaanits, Laul, Lõugas and Tõnisson1982: 223; Lang Reference Lang2007: 156).

Although a large proportion of Roman imports reached the Baltic Sea region via sea routes, the inland water routes were just as important. Analysis of the origin of imported goods indicated that eastward connections via inland water routes became dominant in the third–fifth centuries AD (Michelbertas Reference Michelbertas2001: 35, 47; Banytė-Rowell Reference Banytė-Rowell and Ritums2004: 21–22; Bliujenė Reference Bliujenė and Curta2011: 171–89, 195; Kiudsoo Reference Kiudsoo and Tammaru2014). Denser connections have also been highlighted between eastern Lithuania and the Carpathian Basin during the fifth century AD (Bliujenė & Curta Reference Bliujenė and Curta2011). The Kavastu deposit was found in eastern Estonia on the banks of the River Emajõgi: the largest water route in south-eastern Estonia. It connects to Lake Peipus—a major water route in north-eastern Europe, linking several larger rivers that lead towards the east, south and north. Given the location of the deposit and its historical background, the lamp probably arrived at Kavastu via eastern routes, as part of active trading networks and connections with south-eastern Europe around the mid first millennium AD (Jaanits et al. Reference Jaanits, Laul, Lõugas and Tõnisson1982: 231–32; Laul Reference Laul2001).

The date on which the lamp arrived in Estonia can be estimated from the new AMS data. At least one of the lamp's use-phases occurred around the third–fifth centuries AD, with a second period of use between the fifth and sixth centuries AD. The lamp was therefore in use (and possibly also in circulation) for several centuries in the regions where olive oil (or similar) was exploited. As the lamp was not used for lighting in the northern regions, it must have arrived in its final location no earlier than the fifth–sixth centuries AD. This interpretation extends the chronology of the lamp in its initial region of manufacture by several centuries, demonstrating the importance of acknowledging possible chronological deviations when considering imported objects.

The dates from the metallurgical studies presented by Hausmann (1905) concur well with the AMS results. The alloy content of the bronze bars indicated that concealment occurred as late as the Viking Age or around the turn of the millennium. There has been considerable development in the metallurgical studies of Roman and early medieval copper alloys, contributing to discussions of artefact origin, technology and chronology in Southern and Western Europe (e.g. Craddock Reference Craddock1978; Dungworth Reference Dungworth1997; Pollard et al. Reference Pollard, Bray, Gosden, Wilson and Hamerow2015), but we still lack similar studies for the eastern Baltic material, and a more current comparison for Hausmann's conclusions. Our AMS results indicate that the date of deposition could be slightly earlier, i.e. sometime around or after the fifth–sixth centuries AD. Although these dates do not exclude later deposition, the archaeological context and associated finds point to an earlier timeframe for the Kavastu deposit. There is a phenomenon of concealing bronze artefacts—mainly ornaments and their fragments—as hoards in the Migration Period (AD 450–550) in eastern Estonia. Most are deposited in watery contexts and close to larger water routes (Figure 6; Oras Reference Oras2010, Reference Oras2015). Examples include a deposit of around 50 bronze ornaments of different dates and provenances found on the Piilsi River bank; the Reola deposit of brooches and bracelets in a peat bog; and the Vagula deposit on the bank of a lake in south-eastern Estonia, containing several bronze ornaments. These bronze hoards indicate a widespread intentional depositional practice occurring around the fifth–sixth centuries AD in eastern Estonia. No similar concealments of bronze are found in later centuries, when most hoards contain either iron or silver objects.

The fact that the lamp was concealed along with metal bars and was not actively used in Northern Europe suggests that it was part of a collection of recyclable raw materials.

Further interpretation of these bronze hoards, and the Kavastu find in particular, is complicated. All indicate the continued importance of bronze as the main production material for valuable items—a tradition going back to the Roman Iron Age (Lang Reference Lang2007). The Piilsi and Kavastu deposits contain items probably intended to be re-cast as new objects, perhaps ornaments. Laul (Reference Laul2001: 211–12) argued that local bronze manufacturing developed in south-eastern Estonia at the end of the Roman Iron Age. Abundant scrap metal finds from subsequent centuries might therefore be the direct result of those local manufacturing capacities and the demand for imported raw material, yet the context of concealment contradicts this practical reasoning. The Kavastu and Reola finds were deposited in a peat bog; records also note bone material recovered nearby (unfortunately not retained). The Vagula deposit was found in a lake, the Piilsi deposit on the bank of a river. Their strikingly similar content and context, geographic location and chronology argue for the importance of bronze, and for eastward trade routes in the Migration Period of the eastern Baltic.

The biography of the lamp reveals the multiple shifting, context-specific values and functions of this single object. Once a prestigious object in the Roman Empire, it provided illumination until the fifth–sixth centuries AD. Exactly why and how the lamp travelled to Northern Europe is difficult to say, but it is perhaps related to the turbulent times of the Migration Period and the fall of the Empire, which coincide with our estimation of when the lamp was deposited. It might have arrived from Southern or Central Europe—where it was still used for illumination—via third parties, as a useful raw material and trading good, appealing to northern admirers of bronze who probably knew nothing about the use of such objects for lighting. In its new context, the lamp was conceived as an important raw material and concealed with similar materials—four bronze bars that were once parts of different artefacts, some perhaps also of foreign origin. This set of bronze objects became regarded as valuable metal to be reworked into bronze ornaments, perceived as prestigious items in the north. For some reason, however, someone decided to hide this collection in a peat bog next to the largest water route in the area. As a result of their action, we have been able to reconstruct the biography of this unique Roman bronze lamp.

Conclusions

The example of the Kavastu bronze deposit from Estonia reveals how the issues of artefact chronology of imported objects and the reconstruction of artefact biographies can be tackled using archaeometry to enrich our understanding of use and chronology. By combining scientific and traditional archaeology methods, we have reconstructed the provenance, the possible travel routes and the phases in the use of the Kavastu bronze lamp over half a millennium, and across thousands of kilometres from the south (the Roman Empire) to the north (east Estonia), highlighting its shifting functions from luxurious illumination to valuable raw material. Further, by combining modern techniques with earlier archaeological analysis, we can make important contributions to our understanding of past material culture.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Catherine Hills and Tamsin O'Connell for all their advice and support, and to Martti Veldi, Maria Smirnova and Tõnno Jonuks for their help with the figures. Thanks are extended to the National History Museum of Latvia. We also thank the staff of the Oxford Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit, University of Oxford, for their careful laboratory work. This research was supported by the institutional research funding IUT20-7 of the Estonian Ministry of Education and Research, and by the European Union through the European Regional Development Fund (Centre of Excellence CECT). The authors wish to thank NERC for partial funding of the mass spectrometry facilities at Bristol (contract number R8/H10/63; www.lsmsf.co.uk), and the Estonian Research Council (grant PUTJD64).

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2016.247