Countee Cullen's stock has experienced an appreciable decline since the publication of his first volume of poetry, Color, in 1925. Cullen may have begun his career as one of the most promising young stars of the Harlem Renaissance—Alain Locke anointed him “a genius!” in an influential early review of his work (“Color” 14)—but now he stands on the margins of most critical accounts of the period. To take just one notable example: in his sweeping history of the literary institutions that defined 1920s Harlem, The Harlem Renaissance in Black and White (1995), George Hutchinson declares that Cullen was “never the ‘dominant’ presence” in important African American periodicals like Opportunity, “let alone in the Harlem Renaissance” as a whole (189). More recent critics, in an effort to reckon with the harsh criticism leveled at Cullen from the late 1920s onward, attribute the poet's precipitous fall to the way his initial widespread success aligned him with a feminized popular culture at odds with the masculine forms of “racial authenticity” promoted by other Harlem Renaissance writers (Kuenz 513). They also cite his lack of an explicit political agenda, his apparently “safe” poetic messaging (Molesworth, “Countee Cullen's Reputation” 68).Footnote 1 Yet another, much less examined reason has to do with how Cullen eschewed those modernist signs that have become increasingly central to the study of the Harlem Renaissance, refusing to adopt, either for himself or for his poetry, the early twentieth century's lexicon of the “new.”Footnote 2

Looking to dispense with the associations of docility and servitude that clung to the stereotype of the “Old Negro,” the New Negro movement from which the Harlem Renaissance grew came with clear commitments to this lexicon.Footnote 3 As Nathan Huggins suggests, the movement drew on the rhetoric of novelty and rupture that pervaded many other radical cultural movements from the first decades of the twentieth century in order to stage its own break with the past and to install “a New Negro, a new man” (7). Analyzing the vocabulary of Hubert H. Harrison's period-marking When Africa Awakes (1920), Gerald Early makes a similar observation: “‘New situation,’ ‘new ideas,’ ‘new conceptions,’ ‘new demands’—whatever all of this might be . . . , certainly the post–World War I era is being defined by the African American's ‘newness’” (32). But as much early commentary already attests, Cullen never had much interest in such “newness.” Introducing Cullen's selection of poems in The Book of American Negro Poetry (1922), James Weldon Johnson sets up Cullen as an exemplar of New Negro achievement while also admitting that he is a poet belonging to the “classic line” and that “the modern innovators have had no influence on him” (219). Wallace Thurman, commenting on Color in 1927, put the matter even more bluntly: “although Mr. Cullen can say things beautifully and impressively, he really has nothing new to say, nor no new way in which to say it” (“Nephews” 298). And pronouncements along these lines continue to inflect much later critical portraits, which likewise tend to portray Cullen as being embarrassingly “out of step with his age” (Baker, Afro-American Poetics 52).Footnote 4

This essay makes no attempt to contest the view of Cullen as an untimely poet. Rather, my aim is to reevaluate both the meaning and the value of his anachronistic stance by tracing it back to decadence—the fin-de-siècle aesthetic that courts decline through excess and overindulgence. Cullen's nineteenth-century ethos is frequently ascribed to a general sort of Romanticism.Footnote 5 But lurking beneath this Romanticism is a specifically decadent version of the poet that, as David Levering Lewis once noted, is always “declining, decaying, and dying in his poetry” (When Harlem 76). This is the Cullen who eagerly wrote letters to his fellow Francophile and possible lover Harold Jackman about the alluring prose of Gustave Flaubert and Théophile Gautier and who insisted that others write his name “Countée,” with an accent over the first e (Molesworth, And Bid Him 51, 25). This is the Cullen who provocatively cited Oscar Wilde—at this point a figure still cloaked in much controversy from his “gross indecency” conviction at the end of the previous century—in an essay he wrote for a graduate course at Harvard.Footnote 6 To be sure, Cullen could be repelled by the sort of uninhibited behavior that typically accompanies decadence. His handling of decadent tropes is therefore characterized by the same ambivalence with which he treats the other indulgences—for Cullen, paganism and sexuality—appearing in his verse.Footnote 7 However, in strategically falling back onto the explicitly outdated language of decadence, the poet also found a means of contesting some of the more stifling conventions then crystallizing around the New Negro movement, including its tendency to jettison the past in the name of the new.

Cullen's most ambitious attempt at deploying decadence as a means of recovering this past comes in the form of his 1927 Copper Sun. Indeed, the title of this volume evokes at once the racial issues that preoccupied the poet earlier in the 1920s—“copper sun” as a symbol of a distant and perhaps unreachable Africa in his famous poem “Heritage”—and the decadent mood now hanging over his poetry—“copper sun” as an image of decline, the last light of a dying day. This volume thus provides special insight into how Cullen situates his poetry at the intersection of the Harlem Renaissance and fin-de-siècle decadence. The last several years have seen concerted efforts in literary scholarship to expand each of these fields.Footnote 8 A few recent studies have even begun to explore the convergence of these two movements in the work of Harlem writers like Richard Bruce Nugent, Carl Van Vechten, and Wallace Thurman (Mendelssohn; Murray 179–90; Glick). But if Cullen has yet to play a substantial role in these conversations, it is because there is still a need to better understand the various positions that make up the larger tradition of African American decadence. I outline some of these positions below, using as a starting point W. E. B. Du Bois's early engagements with Anglo-European aestheticism. I then turn to focus on how Cullen's place within this decadent tradition can be initially gleaned by examining his collaboration with Charles Cullen, the illustrator for Copper Sun. Ultimately, however, I argue that Cullen develops his own brand of “Harlem decadence”—one that calls into question the temporal modes available under the Harlem Renaissance as a “renaissance” by conjuring up a more discordant and decadent view of history.

Du Bois, Decadence, and the New Negro

In adopting a nineteenth-century decadent aesthetic for the twentieth century, Cullen was taking his cues, at least in part, from his mentor W. E. B. Du Bois. That Du Bois factors in here at all is likely surprising given his staunch resistance to this aesthetic throughout the 1920s (which did much to spur on a second generation of Harlem decadents who defined themselves in opposition to his standards of Black middle-class taste). Nevertheless, one of Du Bois's most important early works, The Souls of Black Folk (1903), starts by forging a connection between an emergent African American culture and the tradition of Anglo-European decadence. Each chapter of Du Bois's book begins with an epigraph that juxtaposes a passage of verse with a phrase of music; the very first of these pairs a poem from the English aesthete Arthur Symons with the African American spiritual “Nobody Knows the Trouble I've Seen” (fig. 1).

Fig. 1. The epigraph from the first chapter of Du Bois's The Souls of Black Folk. Arthur Symons's poem, here untitled, is “The Crying Water” (1903).

As one critic has recently put it, “Not all of the verse choices in Souls are as lyric or white or odd as the opening selection from Arthur Symons” (V. Jackson 102). Yet, as odd as this choice may at first appear, it should not detract from the important work Symons is doing for Du Bois in this context. Most immediately, the “life long crying” of Symons's sea heightens the sense of constant struggle traditionally associated with “Sorrow Songs” such as “Nobody Knows.”Footnote 9 Moreover, the decadent images through which Symons's speaker expresses a longing for worldly transcendence (“Till the last moon droop and the last tide fail, / And the fire of the end . . .”) underscore Du Bois's emphasis in this first chapter on African Americans’ “spiritual strivings” in the face of racial oppression. The lyrics of “Nobody Knows” rely on a similar tension between earthly struggle and spiritual deliverance:

Finally, these thematic resonances aid in one of the larger aims of Souls, which is to assert the value of African American culture as culture; and here Symons's status as a practitioner of aestheticism proves especially useful to Du Bois, who, in foregrounding the parallels between Symons's decadent poem and this Black folk song, implicitly makes the case that the latter belongs to the same realm of high art as the former.Footnote 10

Through such parallels, Souls opens up the possibility of a modern African American aesthetic that constitutes itself in relation to an earlier decadence. However, Du Bois's decision to do so through Symons also places certain limitations on this relationship from the very start. As Vincent Sherry demonstrates, Symons's greatest significance to literary history has to do with the way he suppressed decadence by transforming it into a less controversial, and more adaptable, form of “symbolism.” In rewriting his 1893 aestheticist manifesto “The Decadent Movement in Literature” as The Symbolist Movement in Literature in 1899, Symons explicitly exchanged the former term for the latter; he also stripped his earlier decadent philosophy of its troubling associations with corruption, decay, and impermanence in order to preserve only its emphasis on a transcendent, spiritual dimension that can be accessed through well-constructed symbols (Sherry 4–14). That Du Bois chooses to engage with the tradition of aestheticism, but only through the sterilized decadence of Symons, in turn reveals his own concerns about being too closely aligned with decadence qua decadence. These were concerns that Du Bois in fact regularly returned to throughout his career, including more than two decades later, in his review of Locke's generation-defining Harlem Renaissance anthology, The New Negro: An Interpretation (1925). There, Du Bois writes admonishingly of Locke's project: “Mr. Locke has been newly seized with the idea that Beauty rather than Propaganda should be the object of Negro art and literature. . . . If Mr. Locke's thesis is insistent upon too much it is going to turn the Negro Renaissance into decadence” (“New Negro” 140–41).

Whereas in 1903 Du Bois connected African American culture to Anglo-European aestheticism as a way of asserting its value, in 1925 he worried that an aestheticist notion of “Beauty” was distracting Locke and his contributors—Cullen among them—from the more important work of racial “Propaganda.”Footnote 11 Such a criticism highlights Du Bois's developing role in the 1920s as the New Negro hardliner who accepted nothing from the movement that was not expressly tied to the mission of racial advancement—that is, the carving out of a “new path” by an “advance guard” of elite African American artists and intellectuals that he describes in Souls (8). Here, it should be noted that much of Locke's writing in The New Negro is actually in lockstep with Du Bois when it comes to his ideas on racial uplift. But in focusing this project so intently on art, Locke also threatens to deviate from the agreed-upon “path”: in his foreword to The New Negro, for example, Locke proclaims that the “talents of the race” need to devote themselves to “creative self-expression” and not just to what he calls “racial journalism” (x); in another essay titled “Negro Youth Speaks,” he even implicitly validates an aestheticist, art-for-art's-sake platform when he describes how a newer generation is making art without much concern for either “racial expression” or “the setting of artistic values with primary regard for moral effect” (47).Footnote 12 From Du Bois's perspective, the problem with such a position was at least twofold: first, that Locke's aesthetic interests do not establish a relationship between “proper art” and “proper development” (Brown 52) and, second, that a commitment to aesthetic autonomy divorced from any interest in advancement or progress exposes the New Negro to the willful declines and corrupting influences of “decadence.”

Du Bois's observation here was accurate in the sense that a younger generation of Harlem Renaissance writers had begun adopting this aestheticist posture in ways that stepped far outside his vision. Indeed, by the second half of the 1920s, a decadent subculture had emerged in Harlem that fully embraced the figure of the dandy as well as the forms of queerness typically associated with this figure. In doing so, this group even broke with Locke, whose “unspoken editorial rules” demanded that one must “elide those ‘decadent’ displays of eroticism” in order to portray the New Negro as both well-mannered and hardworking (Pinkerton 106–07). But as Elisa Glick argues, Harlem's dandies should not just be seen as “the condensation of African American anxieties around racial uplift”—they should be recognized for the “political challenge” they brought to a movement that often policed sexual respectability as an extension of racial respectability (415).Footnote 13 And in this respect, there were few writers as challenging as Nugent, whose inclusion in The New Negro provided him with his initial aestheticist credentials. Nugent caused an outright scandal the following year with his “Smoke, Lilies and Jade,” which first appeared in Wallace Thurman's short-lived little magazine, Fire!!, in 1926.Footnote 14 The story, now credited as the first openly gay text of the Harlem Renaissance, focuses on a young Black aesthete named Alex who is torn between his two lovers: a Black woman named Melva and a white man whom Alex calls “Beauty” (Schwarz 40). However, after a dream in which Alex meets and kisses both lovers in a field of calla lilies, he comes to the realization that he does not have to choose—which leads to a culminating scene, rendered in Nugent's trademark plumes of free indirect discourse, where all three individuals come together:

Melva had said . . . don't make me blush again . . . and kissed him . . . and the street had been blue . . . one can love two at the same time . . . Melva had kissed him . . . one can . . . and the street had been blue . . . one can . . . and the room was clouded with blue smoke . . . drifting vapors of smoke and thoughts . . . Beauty's hair was so black . . . and soft . . . blue smoke from an ivory holder . . . was that why he loved Beauty . . . one can . . . or because his body was beautiful . . . and white and warm . . . or because his eyes . . . one can love . . . (Nugent 87; ellipses in source here and below)

Michèle Mendelssohn claims that Alex's resolution in this final passage—“one can love two at the same time”—announces Nugent's rejection of the either-or logic that informs all binary identities (260).Footnote 15 The point is an especially important one for a reading of Nugent as the decadent descendent of the New Negro: in making space for “Beauty,” Nugent specifically reverses Du Bois's critique of Locke, suggesting that the challenging queerness of this story is aimed at opening up conceptions of the New Negro beyond the narrow identity categories on which it was often based.

Along with this provocative embrace of “Beauty,” Nugent also trades in the sanitized decadence of Du Bois's Symons for a different, and more overtly decadent, literary citation: Oscar Wilde. There are a number of authors drifting through Nugent's “Smoke, Lilies and Jade,” but Wilde is the one who floats most frequently into Alex's thoughts. Early in the story, Alex, after thinking about finding a job, considers how he much prefers to just “lay and smoke and meet friends at night . . . to argue and read Wilde . . . Freud . . . Boccacio and Schnitzler . . . ” (Nugent 77). And after his mother chastises him for his general lack of motivation, he reflects: “it was hard to believe in one's self after that . . . did Wilde's parents or Shelley's or Goya's talk to them like that . . .” (78). And again Wilde comes to mind as he sets out to walk the streets:

. . . to wander in the night was wonderful . . . myriads of inquisitive lights . . . curiously prying into the dark . . . and fading unsatisfied . . . he passed a woman . . . she was not beautiful . . . and he was sad because she did not weep that she would never be beautiful . . . was it Wilde who had said . . . a cigarette is the most perfect pleasure because it leaves one unsatisfied . . . (Nugent 78)

Nugent's references to “Wilde” across these different moments signal not just a kind of decadent posturing (the lying about and smoking with which the story commences) but also a strident directionlessness (Alex's wandering out in the streets) that amounts to another decadent critique of Du Bois, this time dissenting from his adamant belief in “progress.” In other words, it is with these citations of Wilde that the story exchanges the Du Boisian notion of racial advancement with a decadent wilting-in-place through which Nugent advocates for an Alex who does not need to progress or change—who is perfectly acceptable just as he is.

And Nugent was not the only member of the Harlem Renaissance who belonged to this more audacious cult of Oscar Wilde—Van Vechten and Thurman deserve to be counted here as well. As Alex Murray notes, Van Vechten, who is perhaps best known as a promoter of Harlem Renaissance art and literature, was also “at the forefront” of the 1920s renewed “vogue for all things 1890s” (180).Footnote 16 In fact, Van Vechten's first novel, Peter Whiffle (1922), concerns a narrator, named “Carl Van Vechten,” who in recounting the titular Peter's efforts to become a great decadent writer is literally led back to the hotel where Wilde died and to his tomb in Père Lachaise cemetery (55). Also relevant is Van Vechten's controversial Nigger Heaven (1926), which, in its effort to portray a decadent “inversion of values” through exotic scenes of Harlem nightlife, reveals how this sort of decadence could easily slide over into the white exploitation of primitivized Black spectacle (Huggins 98).Footnote 17 With respect to decadence's race relations, Thurman's work is much more sophisticated. His notorious roman à clef, Infants of the Spring (1932), centers on Raymond Taylor (Thurman's character) and the bohemian Harlem studio he dubs “Niggeratti Manor.” One of Raymond's roommates, Paul Arabian (modeled on Nugent), fashions himself as a Wildean who is highly conscious of the identity conflicts brought about by his aestheticism: “Being a Negro, he feels that his chances for excessive notoriety à la Wilde are slim. Thus the exaggerated poses and extreme mannerisms. Since he can't be white, he will be a most unusual Negro” (59). To be sure, the novel is as much a parody of such decadent tendencies as it is a tribute: one of Raymond's much less self-aware roommates, Eustace Savoy, goes so far in making himself up in the style of white, “mid-Victorian” beauty that he falls victim to an “unidentified scalp disease [that] rendered him bald on the right side of his head” (22). And yet, even the novel's sharpest instances of satire are themselves evidence of the extent to which, during the later 1920s, Harlem had become newly engulfed in an old decadence.

Cullen and Cullen

Still, Countee Cullen, the onetime poet laureate of the Harlem Renaissance, hardly seems to belong among the decadent denizens of Raymond's studio.Footnote 18 For one, Cullen had a close relationship with Du Bois that only grew closer, if also more complicated, in the years following Color.Footnote 19 Moreover, he possessed a lifelong desire for academic achievement that generally kept him from indulging in the outlandish behaviors celebrated by Thurman and the other members of Harlem's Wilde cult. As A. B. Christa Schwarz points out, it was Cullen's reputation for both academic success and good manners—the way he was set up from the very beginning of his literary career “as the embodiment of the virtues of the Talented Tenth”—that led to his lifelong “exercise of self-censorship” on the matter of his homosexual relationships (49, 51). And it is for this reason that same-sex desire only ever manifests in his poetry as a kind of “omnipresent absence” to be communicated through a complex series of “ellipses or codes” (51). It is perhaps not surprising, then, that Cullen's turn toward the aesthetics of decadence in the second half of the 1920s was both a subtle and ambivalent one marked by his oblique references to an already heavily coded decadent discourse.

A term paper Cullen wrote at Harvard in the spring of 1926—notably, after the publication of Color but before Copper Sun—showcases something of the overall approach here. The paper is a defense of Walter Pater's method of art criticism, which centers on the amount of pleasure the critic is able to derive from a particular art object. The choice of topics is itself somewhat unexpected given Pater's reputation as the scandalous Oxford don who led his students into a life of decadent hedonism—and thus perhaps reflects Cullen's struggle with the boundaries of academic acceptability as they were being drawn for him. Yet Cullen also makes a concerted effort throughout his paper to avoid making any specific pronouncements on Pater's decadence; just as Pater discreetly discusses the theme of decadent homosexuality within his criticism through the coded language of the “Renaissance,” Cullen only ever addresses Pater's quest for critical “pleasure” in the terms of his “Romanticism” (“Walter Pater” 3).Footnote 20 This circumvention of decadence becomes even more patent toward the conclusion of the essay, when Cullen arrives at Pater's most famous (and decadent) student, “the brilliant but ephemeral Oscar Wilde,” who Cullen says is “steeped in the romanticism of his sire” (10). Here, Cullen is clearly at pains to place some distance between himself and Wilde: he accuses Wilde of having no “restraint” and calls his paradoxical form of writing an example of “Impressionism at its unique worst” (10). But, interestingly, he also doubles back on this disavowal by ultimately using Wilde's ideas about the necessary subjectivity of criticism to validate how, with Pater, “the critical act became synonymous with the creative act” (11).

While Nugent, Van Vechten, and Thurman all make obvious their decadent ties by explicitly placing themselves in an aesthetic genealogy that led back to Wilde, Cullen follows more closely after Pater in choosing to employ a series of linguistic displacements and rhetorical sleights of hand. In Copper Sun, this strategy of indirection manifests in the way the volume displaces its most overt claims to decadence onto another Cullen—Charles Cullen, the book's illustrator. Countee and Charles Cullen were not related. However, readers often assumed that they were, which effectively provided the former Cullen with a kind of authorial avatar—another version of the poet's self—through which he could announce the volume's more decadent themes.Footnote 21 Countee's decision to collaborate with this other Cullen immediately brought a provocative aestheticism to the volume: a popular illustrator of Harlem Renaissance texts, Charles Cullen worked in a distinctive style that updated the decadent line drawings of Aubrey Beardsley with touches of 1920s art deco. His illustrations were featured alongside Nugent's stories in Fire!!, and they decorated the pages of other experimental Harlem Renaissance collections like Ebony and Topaz (1927). But, as Caroline Goeser observes, some of Cullen's most daring images can be found in Copper Sun (93). A prime example comes from the drawing that introduces the section “At Cambridge” (fig. 2)—the title of which is itself a nod to the place where Cullen the poet was reading decadent authors like Pater and Wilde. The illustration, which depicts one male figure in the act of prostrating himself before another during some sort of religious ritual, shows how Cullen fills in Beardsley's black-and-white templates to conjure racialized bodies; it also exemplifies the way his drawings mingle spirituality and sex, with the positioning of the two figures highly suggestive of a sexual relationship (and one with more than a hint of the sadomasochism usually found in Beardsley's artwork).

Fig. 2. The illustration by Charles Cullen that introduces the section “At Cambridge” in Countee Cullen's Copper Sun.

The illustration provides a useful starting point for reading Cullen's poetry, where similar themes are rendered, albeit with a much greater sense of reserve and propriety. The first section's appositely titled “Timid Lover” is representative.Footnote 22 This poem begins with a rather conventional proclamation of love:

Soon afterward, however, the speaker declares that this relationship cannot take place, though not for lack of romantic interest:

The poem then ends with the speaker's commitment to a kind of silent devotion, what Thomas Wirth describes as a “hidden love” (53):

Such a conclusion at first appears to be one of sexual renunciation, which also seems to suggest that the invocation of spirituality has to do with how this particular relationship violates some religious law. Yet the ambiguous syntax of the first line—which can be read as both a declaration (“So must I”) and the start of a question (“So must I?”)—points to a more complicated reading, one that is enhanced by the way the poem's final lines combine this transgressive sexual attraction with spirituality: the love interest is the “acolyte” of this ritual, and what is being offered in this relationship is deemed to be “holy.” In short, this love, though prohibited, is divine. The tension recalls Ellis Hanson's thesis on how nineteenth-century decadents “explored with considerable daring the relationship between sexuality and religion” (21).Footnote 23 According to Hanson, these authors perceived that religion, through the particular ways in which it organizes and denies sexual experience, frequently “excites and exploits the very desires it claims to disavow” (23). The conclusion of “Timid Lover” features exactly this sort of exciting denial, where the refusal of sexual contact appears as a tantalizing extension of the same act, the offering of “holy fruit.”

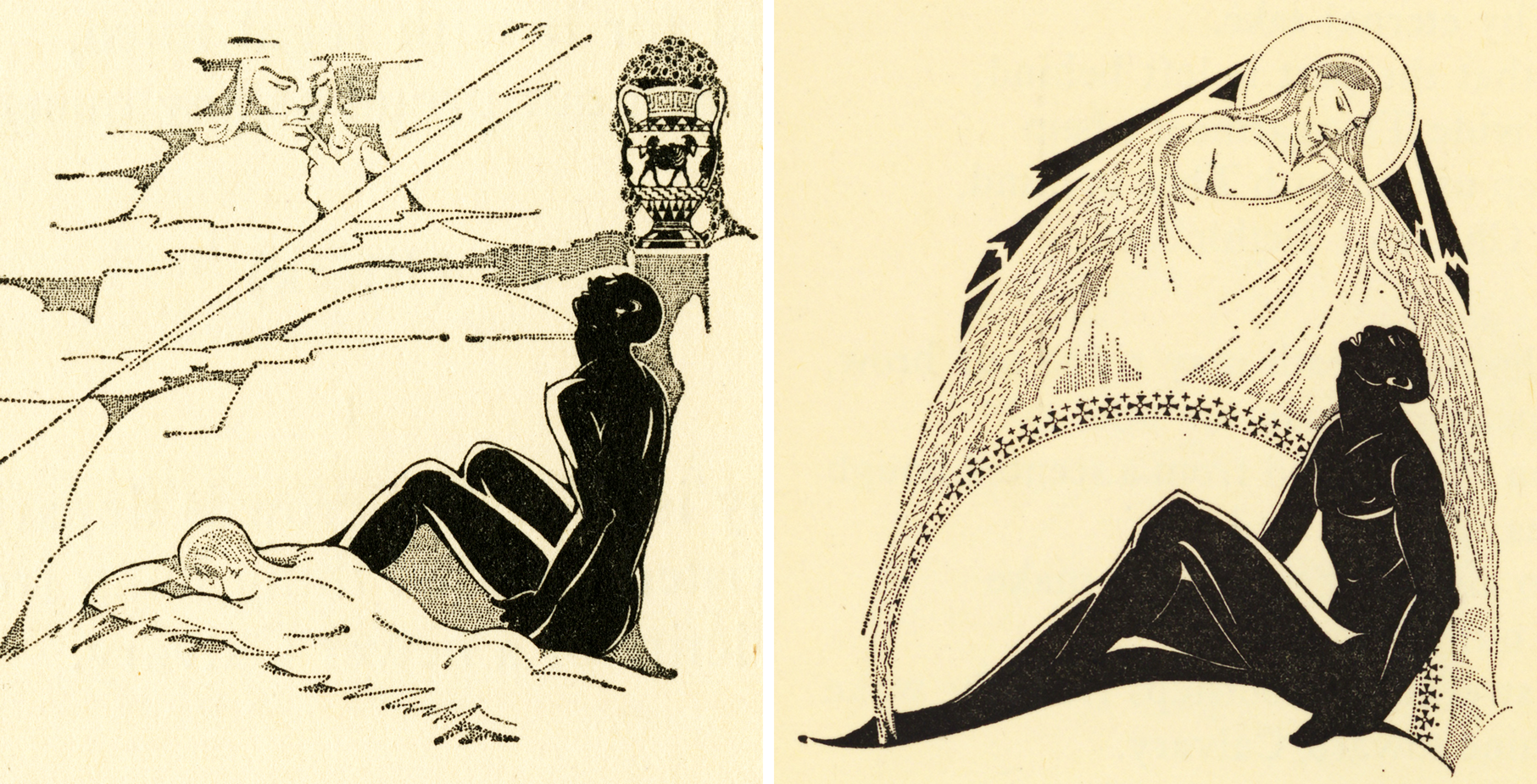

Two of Charles Cullen's other illustrations from the first section of Copper Sun further support such a reading. The first depicts two nude male figures—one Black and one white—with the first throwing his head back in agony and the second burying his face in shame (fig. 3). The body language suggests the racial dynamic of Black pain and white guilt. But the decadent overtones also link this agony/shame dichotomy to the volume's sexual themes. In this sense, the scene is not much different from that of “Timid Lover,” where sexual desire—a desire that, with this image, is more clearly labeled as both queer and interracial—is met with pauses and renunciation. A colossal, godlike being looms over the two men in the drawing, his apparent judgment of the love placed in the foreground of the image materialized in the lightning bolt sent down from the heavens to divide the scene. However, just as in “Timid Lover,” the sense of religious condemnation that emerges here is eventually reversed. With respect to Charles Cullen's illustrations, this reversal takes place with the next drawing (fig. 4), which appears just two pages later, in the same position on the page, signaling that this new image can be seen as a progression of, or a replacement for, the first. The second image features the same Black figure, seated in almost the exact same position as before. But the posture now reads less as agony or pain and more as sexual ecstasy; a white Christ figure, with a halo illuminated behind his head, descends from above to lovingly embrace the man below. The two figures face each other with a sense of adoration that, in addition to resolving the earlier agony/shame dynamic, serves to affirm the homoerotically charged spiritualism presented in Cullen's verse.

Figs. 3 and 4. Illustrations by Charles Cullen from the “Color” section of Countee Cullen's Copper Sun.

Taken together, these last two illustrations stand to illuminate the other queer love poems found in Copper Sun. These poems generally operate through what Jeremy Braddock identifies as Cullen's “conjectural poetics,” a mode of lyric address in which the gender of the lover is intentionally elided by the poem's speaker, thereby making space for the emergence of queer romantic possibility. Such a possibility is the central theme of “Nocturne,” the poem that directly follows “Timid Lover” in the collection. Here, the speaker tells an ungendered lover to concoct lies—“I am in the mood for lies”—so as to make the world lovelier than it appears (Cullen, Copper Sun 21). Such “lying” resonates with the aesthetics of decadence on at least two levels: first, as Alex from Nugent's “Smoke, Lilies and Jade” has already demonstrated, the languid repose of lying represents the signal posture of decadence in its rejection of productivity; and, second, as Wilde famously argued in the Intentions (1891) essays Cullen cited in his Harvard paper, lying—meaning in this case “to deceive”—is a creative act essential to all forms of art (the purpose of which, as Wilde sees it, is to transform nature into artifice).Footnote 24 In “Nocturne,” Cullen's speaker specifically draws on this sort of deceitful artifice in order to build a new world without definite answers, or even definite identities:

The conclusion of the poem is therefore one of queer consummation that overturns the hesitancy found in “Timid Lover” by refusing to seek out any details about the romantic encounter at hand (“I will not ask you How nor Why”).

Moments along these lines can be found in Copper Sun's other poems, too. For example, “Words to My Love,” which comes next in the volume, relies on a similar conjectural strategy. This poem builds to another confident and queer conclusion—and it does so while returning to the spiritual metaphors that animated poems like “Timid Lover.” The final lines of “Words to My Love” announce, “With wine and bread / our feast is spread / let's leave no crumb” (22). Once again the spiritual realm has been made sensual, the Eucharistic “wine and bread” in this poem becoming a central metaphor for these two unspecified lovers’ “feast.” And yet, even though the persons involved in this love remain shrouded behind a veil of obscurity, the love itself is put on bold, sumptuous display (“let's leave no crumb”), suggesting that “Words to My Love” can be understood as the final step in a poetic triptych that moves the volume from its initial “hidden love” toward a much more open and brazen form of queer decadence.

On Harlem and History

The queer love poems in Copper Sun have notable anchor points in the other versions of Black aestheticism discussed earlier in this essay. These poems’ constant searching for the “divine” connects them back to the “spiritual striving” that Du Bois had articulated through Symons's symbolism in The Souls of Black Folk; their pursuit of a queer sensual experience aligns them with the embrace of pleasure and sexuality that characterized a younger generation of Harlem decadents—and that Du Bois and Locke, as leaders of the New Negro old guard, so ardently rejected. To a certain extent, then, Cullen's volume finds its larger significance in the way it brings together these two opposing strands of African American engagement with the literature and culture of fin-de-siècle decadence. And yet, as this final section demonstrates, Copper Sun also achieves its own sense of distinction in its attention to decadence as more than just an aesthetic of either spirituality or excess: in various poems throughout his collection, Cullen marshals a decadent interest in death, decay, and afterlife as a means of resuscitating the kind of moribund past that is capable of both counterbalancing and contesting the historical logic of the Harlem Renaissance itself.

In other words, Cullen employs these macabre themes in order to inject a feeling of historical lateness or afterward into a cultural movement thoroughly consumed by the “new.”Footnote 25 At issue here is the very idea of a “Renaissance”—which, whether used in conjunction with “Harlem” or some other modifier, aims to evoke the kind of social progress commonly associated with the earlier Renaissance of Western civilization (and thus to introduce African American culture into that civilizational narrative). In The New Negro, Locke deploys this term—there he calls it a “Negro Renaissance”—in this way, to mark the “modernity of style” and “originality of substance” through which the New Negro contributes to this larger idea of cultural progress (50, 51). However, this “Renaissance” discourse also promotes a strict focus on new beginnings that tends to divorce the period in question from the other historical moments surrounding it, especially those coming prior to it—a tendency that is symptomatic of the make-it-new thinking of modernism more generally.Footnote 26 And even more capacious terms, like “New Negro movement,” still carry with them the same tendency to stress a progressive or forward-looking history that sacrifices much temporal complexity in its privileging of the “new.” Indeed, as Andreá N. Williams points out in her work on the Harlem Renaissance's prehistory, the writers who adopted this “New Negro” label were often hostile toward preceding generations (and even toward earlier versions of the New Negro) as well as prone to burying the more traumatic elements of the African American collective past (47).

Decadence, on the contrary, has absolutely no qualms about digging up the past—or even bringing back the dead. As the word's etymological roots (de + cadere) suggest, decadence comes with a temporal emphasis on a falling away or decline, the end of things rather than the beginning. However, through its penchant for exploring active scenes of decay and decomposition, decadence also illuminates what we might call an animate past, or a past that refuses to remain, comfortably, in the past. It is an idea neatly embodied in the Baudelairean image of the “carcass,” which defies death by breathing and even singing as a result of its own purification.Footnote 27 Such an unsightly resuscitation of what was once dead contrasts greatly with the search for a “usable past” that had some Harlem Renaissance writers, including at one point Du Bois, turn back to idealized versions of an earlier African folk culture.Footnote 28 This decadent resurrection implies a different kind of rebirth from that of the “Renaissance” in that it stands for a paradoxical afterlife in which the temporal trajectories of declining and rising take place simultaneously. As a historical vision, then, decadence operates by confusing the very sort of binaries upon which a progressive model of history rests—past/present, dead/alive, old/new—and re-presenting them as competing terms that are layered on top of one another in the same, inchoate timeline.Footnote 29 In short, a decadent history is one felt to be fractured and volatile instead of ordered and reliable.

So when the speaker of Cullen's “Nocturne” proclaims at the end of that poem, “I see death drawing nigh to me,” the gesture is not merely one of carpe diem (meaning the speaker sees the end of his own life approaching) but also one of decadent resurrection (the reanimation of a dead past now coming back into view). While Cullen has woven the latter idea throughout Copper Sun, the text most focused on this sort of untimely afterlife is the volume's second poem, “Threnody for a Brown Girl.” This “obituary poem,” as Jean Wagner labels it (321), begins with the speaker telling a grieving audience not to “weep” for the recently deceased girl of the poem's title, as their loss will only be temporary in this instance:

In fact, the speaker assures the girl's mourners that she is “nearer” than they realize by taking the funeral commonplace that death returns us to the earth—“Men daily fret and toil, / staving off death for a season, / Till soil return to soil” (4)—and translating it into a frighteningly vivid picture of the deceased's union with the natural environment through the process of decomposition:

A similar decadent metamorphosis is visualized in the illustration that introduces the entire volume (fig. 5). There, a Black body, in this case a male figure, appears before a setting sun as his feet become rooted down into the ground and his arms grow outward into blossoming tree branches. The image undoubtedly achieves a kind of beauty. And yet, the visual reference here to the mutilated Lavinia in Shakespeare's Titus Andronicus—whose “branches” are amputated after her brutal rape—renders it equally painful and grotesque, reminding us that the kind of resurrection taken up in Cullen's poem is at best an ambivalent affair.Footnote 30

Fig. 5. Charles Cullen's introductory illustration for Countee Cullen's Copper Sun.

This especially decadent version of rebirth—with its disquieting mixture of life and death, blossom and decay, beauty and pain—prepares the way for another important reversal at the end of the poem. In the last stanza, the speaker declares that the “threnody” of the title should be directed not at the recently departed girl but at those who have gathered to mourn her:

On first reading, the living mourners need these “elegies” because they are the ones who are actually suffering this loss, the death of the brown girl. However, the poem also points to another kind of loss here with the mention of individuals “who take the beaten track” in trying to “appease” others with hearts that “lack”: it is a description that, with its undertones of violence and servitude, conjures the specter of slavery. And once uncovered, these historical undertones serve in recasting the poem's previous allusions to a generalized human struggle as imagery specific to life on the southern plantation for African Americans (“fret and toil,” “season,” “soil return to soil”). Such imagery, now redefined, adds another layer to the mourning in the poem at the same time as it lends further clarity to Cullen's decadent project: in this poem and elsewhere throughout his collection, Cullen charges his aesthetic of decadent decay with the task of articulating a particularized African American history where death had a very palpable presence among the living and where the past continued to assert itself well after the fact.

The life-in-death, death-in-life state depicted in “Threnody” therefore contributes to Cullen's larger effort to replace a simplistic, progressive history with the kind of alternative decadent temporalities put on display in Copper Sun's first poem, “From the Dark Tower.” This sonnet, which immediately strikes an unconventional tone with its dark subject matter, begins:

We shall not always plant while others reap

The golden increment of bursting fruit,

Not always countenance, abject and mute,

That lesser men should hold their brothers cheap. (3)

The suggestions of forced labor and devalued human life again place the poem in the historical context of slavery. But this is patently a history—as signaled by the symbol of overripe, “bursting fruit”—in a state of decadent decline. This is the end of the day for the southern plantation. As Houston A. Baker, Jr., points out, the poem also prophesizes the arrival of a “new day” for Black America (Afro-American Poetics 74). On this note, the speaker continues:

Not everlastingly while others sleep

Shall we beguile their limbs with mellow flute,

Not always bend to some more subtle brute;

We were not made to eternally weep. (Cullen, Copper Sun 3)

However, the main provocation here actually lies in how these two days bleed into one another in the “night” of the final sestet:

The night whose sable breast relieves the stark,

White stars is no less lovely being dark,

And there are buds that cannot bloom at all

In light, but crumple, piteous, and fall;

So in the dark we hide the heart that bleeds,

And wait, and tend our agonizing seeds. (3)

These last lines contain Cullen's most concentrated expression of a decadent history: a history caught between two days, in which the end of one day, that of white antebellum slave culture, is simultaneously the start of the next, that of African American emancipation. Indeed, as portrayed in this stanza, these two days—and the apparently discreet historical moments they represent—mingle together in the same dying light rather than follow one another in any sort of orderly, sequential fashion. Such a convoluted history is finally encapsulated in the speaker's decadent “seeds,” which bloom, against nature, in this night's fertile darkness.

Wading into this darkness, Cullen uses his decadent poetry to reveal how the past takes on its own afterlife—an afterlife that disrupts contemporary assertions of the “New Negro” by recalling America's old history of anti-Black racism with disturbing clarity. At the same time, though, the fading light of his Copper Sun illuminates the various possibilities to come out of decomposition and decay. This is the decadent sense that, even while these dead histories linger, other histories, alternative histories, can grip down and take root in the soil made ready by decline. Cullen's untimely adoption of a decadent aesthetic to figure such a history demonstrates, finally, that “decadence” is not so much a literary period belonging to a specific time and place as a historical orientation to be assumed in practically any moment. It also replaces the singular focus on new beginnings that tends to characterize the Harlem Renaissance with an altogether different historical perspective. This is the perspective of a Harlem decadence that is capable of looking backward and forward at once—that is capable of searching out those points of intersection with what, presumably, has already been left to the past.