INTRODUCTION

In the last decades of the nineteenth century and the first decades of the twentieth, whites in the American South worked to rebuild the regime of white supremacy that the Civil War had upended. They enacted laws that disfranchised and segregated African Americans. They created a criminal justice system that re-enslaved many in convict leasing programs and state-run penal farms. And they illegally lynched and legally executed—sometimes in front of audiences of thousands—Black people.

The relationship between legal executions and white supremacy was not as straightforward as we might expect, however. Materially, the connection was clear. Nearly 75 percent of all those executed in the former Confederate states from 1877 to 1936 were Black men, a reflection of whites’ low regard for the value of Black lives (Espy and Smykla Reference Espy and Smykla2004).Footnote 1 And yet the white supremacy driving the use of the death penalty in the South was not always seamlessly conveyed in newspaper reporting about executions. Through a comprehensive analysis of sixty years of execution coverage in the Atlanta Constitution and the New Orleans Picayune (after 1914, the New Orleans Times-Picayune), I show how the legal and religious rituals performed during executions—and their representation by journalists to the wider public—would sometimes reinforce an image of African Americans as legally, spiritually, and politically similar to their white counterparts.Footnote 2 The opportunity to make a final statement gave the condemned an opportunity to be heard, to object, to tell their side of the story—indicators of their status as rights-bearing members of the political community that was punishing them. Religious sermons given by ministers and hymns sung by execution audiences, meanwhile, underwrote a vision of the condemned as candidates for heaven. Journalists of these two leading newspapers of the “New South”Footnote 3 sometimes depicted Black defendants as members of communities that would mourn their loss and bearers of rights that the state was bound to respect.

Over time, as white supremacy moved from a paternalistic to a radical, violent form and the social and political status of African Americans in Southern society deteriorated,Footnote 4 newspaper coverage of Black men’s executions shrank. As radical white supremacy took hold in the 1890s, and the rate at which whites lynched Black men soared, the median length of articles describing the legal executions of Black men plummeted 75 percent, from sixteen paragraphs to four. In brief articles, journalists announced their executions in clinical, subdued tones. The men put to death by the state increasingly appeared as neither sympathetic souls nor bloodthirsty beasts, but as ciphers, nonentities that the state was dispatching with little fanfare. When applied to African Americans, capital punishment increasingly seemed like a dry, technical procedure.

No such change occurred in coverage of white men’s executions in the Constitution and the (Times-)Picayune. Throughout the sixty years following the end of Reconstruction, coverage of their deaths was comparatively robust. Editors and journalists paid more attention to their executions, covering them more often and at greater length. Perhaps most notably, reporters sometimes depicted the white men who died at the hands of the state as tragic heroes who faced their deaths with admirable courage and dignity. The racial differences in execution coverage became even more pronounced over time. When the median execution story for Black defendants plummeted to four paragraphs in the mid-1890s, it spiked to seventy-seven for white defendants (Figure 1). As evidence of Black men’s political and social ties disappeared from execution coverage, reports of white men’s executions continued to quote their voices directly and note the names of the family members and friends they were leaving behind, reminders that these men belonged to political, religious, and social communities.

Figure 1. Median Length of Execution Coverage in the Atlanta Constitution and the New Orleans (Times-)Picayune, 1866–1936.

In what follows, I argue that execution coverage of Black and white men during this sixty-year period played an important and underrecognized role in what historian Grace Elizabeth Hale (Reference Hale1998) has called the late nineteenth and early twentieth century national project of “making whiteness.” Executions in the South disproportionately killed Black men. But execution coverage in two of the South’s leading newspapers lavished attention on white men who met their fate with courage and dignity. As coverage of Black men’s executions shrank in length and thinned in substance, the death penalty became a punishment that respected and reinforced the “whiteness” of the men whose lives it took.

SENTIMENTAL EXECUTION NARRATIVES OF WHITE MEN, 1877–1906

In the post-Reconstruction South, journalists covered the executions of white men whose crimes had garnered widespread attention in articles that regularly topped one hundred paragraphs. In their reporting, the condemned would become the protagonists of a sentimental narrative, sympathetic souls who met their fate bravely. The men in these accounts appeared not as beasts who could only be subdued by force, but as responsible persons whose humanity was recognized, even honored, during the very act of putting them to death.

In some ways, these sentimental execution narratives reflected a vision of the condemned set forth in the philosophical writings of Enlightenment philosopher Immanuel Kant. For Kant, justice—not public safety—requires the death penalty. One who commits a murder must “duly receive what his actions are worth” (Reference Kant1965, 102). Under this retributive rationale for punishment, the state must treat the offender as a morally accountable person capable of willing punishable acts. To withhold punishment is to unjustly deny the offender’s status as a mature human being. But while the offender’s status as a moral being may require his death, it also requires that the punishment not be cruelly implemented. While an execution is an act of political erasure, a loss of “civil personality,” Kant insists that it “be kept entirely free of any maltreatment that would make an abomination of the humanity residing in the person suffering it” (Reference Kant1965, 102).

This Kantian vision of the condemned was compatible with the widespread embrace of Christianity and Victorian gender norms in Southern culture. Since the first British settlements in North America, a Christian concern with the state of the soul on the brink of death had been central to execution rituals (Cohen Reference Cohen1993; Halttunen Reference Halttunen2000; Banner Reference Banner2002). In the sermons given at execution sites and the commercially sold broadsides that offered accounts of capital crimes and punishments, writers emphasized the accountability of the condemned to a divine moral order. The condemned had an interior self, a soul, that was both blameworthy and, if penitent, worthy of God’s grace. Such rhetoric was common in Southern executions in the late nineteenth century. While religious fervor in the South had waned after the Civil War, a white Protestantism that “tended toward fundamentalism, evangelism, and other-worldliness” grew substantially in the post-Reconstruction era (Williamson Reference Williamson1986). Reporters lavished attention on the state of a condemned man’s soul. In its coverage of Thomas Woolfolk’s execution on the Georgia gallows in 1890, the Constitution reproduced the man’s prayer to “Thou Omnipotent Being who presides over all things,” asking him to “have mercy on my soul, which I now entrust to Thy keeping. Make it pure and clean. God bless my sisters. Bless those who have gone before me. Forgive all those who have abused me, and accept my soul, for Jesus sake.” The reporter noted that the speech was “audible to all who were within a hundred yards of the scaffold, and many a tear was seen. Woolfolk was calm throughout his appeal for heavenly mercy, but was deeply affected” (“Ten Victims” 1890, 1). By emphasizing the space allocated to religious rituals at Woolfolk’s execution, the Constitution highlighted the deference authorities paid to his soul, and thus his humanity.

Sentimental execution narratives also reflected a preoccupation with Victorian ideas about manhood that were widespread in the New South (Williamson Reference Williamson1986).Footnote 5 An execution had the potential to mark a man with infamy. But reporters’ execution coverage portrayed death at the hands of the state as an opportunity to display their courage and act honorably. In its coverage of Arthur Schneider’s 1896 execution, the Picayune wrote of his bravery with barely concealed admiration. Several onlookers had underestimated Schneider, the reporter wrote, predicting that he would unravel emotionally atop the gallows. They were quickly “undeceived.” Schneider kissed a cross offered to him, “and a dead silence momentarily fell upon the multitude, so simple, and conclusive was the proof that in his dire extremity Arthur Schneider remembered his utterance of the night before, ‘I will die like a man, out of respect to my dear father, who is a solider in far-away Germany’” (“Arthur Schneider” 1896, 11). When Jon W. Dutton was executed in Cartersville, Georgia, in 1893, the Constitution noted that he brought copies of a “book of his life written by himself” (presumably a stack of broadsides) to his execution and that authorities permitted him to sell them to the crowd to raise money for the support of his wife and children in Alabama. Having accomplished this task, he was able to go to his death “readily and firmly. There was not a tremor about him as he put his feet upon the trap” (“Choked to Death” 1893, 3).

At the heart of every sentimental execution narrative was the assumption that condemned men’s lives had value. That which made the condemned in these narratives seem sympathetic—their mental resolve in the face of enormous stress, their sense of duty to their female dependents—reinforced an understanding of them as men paying a debt they owed with dignity and honor. And it reinforced a vision of the state as an entity that took individuals seriously, treating them not as means to an end but as ends in themselves. To be sure, not every execution of a white man was the occasion for a long, sentimental execution narrative. But execution reporting humanized condemned white men by noting everything from the family and friends who visited them in their final days to the final words they spoke upon the gallows to the location of the funerals that would be held for them.

COVERAGE OF BLACK MEN’S EXECUTIONS, 1877–1906

While journalists for the Constitution and the Picayune often portrayed condemned white men sympathetically, their coverage of Black men’s executions was fraught with a mix of sentiments that reflected the unsettled status of African Americans in the post-Reconstruction South. During Reconstruction, Black men had held elected and appointed offices in state and federal governments. But over the course of the 1870s and 1880s, Southern Democrats came to power in states across the South and ended the experiment in biracial governance that had followed the Civil War. As Black men were being ousted from political power, white attitudes toward them varied. A small minority of “racial liberals” did not want to drive Black people out of political life and were, as historian Joel Williamson has put it, “deeply impressed with the progress that black people had made under Northern leadership during Reconstruction” (1986, 71). Most whites, though, were racial paternalists. They cast African Americans as permanently childlike and therefore unfit for self-governance yet entitled to a place in society that benevolent whites would define. While racial paternalism justified the excommunication of Black men from the political sphere, it nevertheless recognized a common humanity shared by white and Black people. In the 1890s, however, the political climate changed. In response to the moral and economic insecurity created by the South’s transformation into a modern society, a radical, violent form of white supremacy took hold among Southern whites. Black people became the scapegoats for feelings of white dispossession. Whites increasingly regarded them not as children but as dangerous animals who, without the bonds of slavery, were wreaking havoc on white civilization, most notoriously in the form of Black men raping white women (Williamson Reference Williamson1986).Footnote 6 To read coverage of Black men’s executions in these newspapers in the 1870s, 1880s, and 1890s is to encounter a range of white perspectives on formerly enslaved people—sometimes sympathetic, frequently hostile, and often contradictory.

The Atlanta Constitution’s coverage of the 1883 execution of John Bailey and Henry Wimbish in Macon, Georgia, demonstrates how the techniques that reporters used to humanize white men could sometimes shape their coverage of Black men’s executions. Writing in the early 1880s, when radical white supremacy was not as entrenched as it would become the following decade, the reporter for the Constitution portrayed the two men as members of a political and spiritual community. The article described the morning of execution day in melodramatic terms. “The prisoners slept well last night,” readers learned, and “with the coming of dawn, they appeared to be in happy spirits, and seemed joyful over the idea that this was their last on earth. For them the sun of this world would rise no more.” Bailey and Wimbish seemed, as white men in sentimental execution narratives often did, otherworldly. Their happiness suggested a peaceful acceptance of their mortality that is generally unfamiliar to the living. In a scene that reads like an inversion of Christ’s exit from his tomb and ascension into heaven, the two men “walked forth” and “ascended” the gallows in “white shrouds.” In front of a mixed race, intergenerational crowd of six thousand, Bailey spoke of his soul: “Calmly, intelligently, in well chosen words, he professed the belief that his sins were forgiven and his final redemption assured. Bailey betrayed no nervousness, but conducted himself entirely as if he felt the full reality of the hour, and that in a few moments he would be ushered into eternity.” Wimbish was less composed, the paper noted, his voice shouting more than speaking at times, but his message was also one of confidence in his salvation: “Soon the trigger will spring and my soul will fly into eternity and I will rest safely in the arms of Jesus. Fellow-citizens, prepare to meet me at the great hour, that time which no man can escape.” The reporter noted that the African Americans in the crowd responded by shouting “Amen” and “Glory be to God” (“Two Necks Broken” 1883, 1).

The focus of the men’s final words—and the article in general—was on the souls of these two men, but the political subtext of the occasion was unmistakable. Wimbish, after all, referred to those in the interracial crowd as “fellow-citizens.” Here, nearly fifteen years after the ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment, was an uncontested assertion of the constitutional guarantee of Black citizenship and belonging in a public ceremony produced by Southern whites. The clothing the men wore also signified their belonging. In the days leading up to their execution, the newspaper noted, the owner of a local clothing establishment measured them for suits. “Hats were also furnished them” and “Jailer Foster gave them a clean shirt apiece.” Here and elsewhere, the paper would even go so far as to reproduce the suit sizes (a thirty-six vest, thirty-two waist, and thirty pant length for Bailey; thirty-five, thirty-one, and thirty-one for Wimbish). In an era when few Black men could afford tailored suits, an execution was a perverse occasion for presenting the men as respectable, dignified citizens (“Two Necks Broken” 1883, 1).

In addition to portraying the condemned as humans and citizens, reporters portrayed them as “grievable,” that is, as beings whose value to others was keenly felt, and whose loss would inspire mourning (Butler Reference Butler2009). Reporters could signal a condemned man’s “grievability” with something as simple as mentioning the friends and family members who visited and comforted him in his final days. In Bailey’s and Wimbish’s execution, for instance, the newspaper reported that the men’s wives had spent three hours with them on the day before their execution. When the men were hanged, moreover, the newspaper noted the emotional response of the women and the broader Black community that had come to witness their deaths: As the trap fell and “the forms of the two unfortunates dangled in the air,” the newspaper noted, a “loud moan went forth from the crowd of negroes, and wild shrieks of woe and agony, coming from the wives of the hanged culprits, who were present and witnessed the terrible fate of their husbands.” The event that had begun with a “mournful march to the gallows” would end with the women taking charge of their husbands’ remains and ensuring that they would be given “a decent burial” (“Two Necks Broken” 1883, 1).

The spiritual counsel given to condemned men in their final weeks, the presence of those who loved them at their executions, the deference to their voices on the gallows, the custom of purchasing suits and food for them—all of these standard dimensions of executions made sympathetic journalistic accounts of their deaths possible. William Johnson was executed in Louisiana in 1890, as radical white supremacy was beginning to take hold in the South. At this precarious moment, the Picayune offered a humanizing portrait of Johnson, declaring him genuinely transformed by a “radical change wrought in him by religion,” one that filled him with an admirable “intrepidity at the end.” When the sheriff read the death warrant, the paper marveled, Johnson

seemed as determined as ever, but not indifferent as before. He had grown to realize that he was to die, that it would be painful, that an awful mystery was about to be entered, and that life would suddenly go out of his body in less than an hour. Yet knowing these, he controlled himself and showed a fortitude which has seldom been witnessed at an execution.

While one of the sub-headlines in the Picayune’s account of Johnson’s execution referred to him as “one more guilty man … made an example to deter others from evil deeds,” the bulk of the coverage was instead focused on Johnson’s spiritual maturity. “Stood it like a man,” Johnson said just before the trap fell, his last words a “triumphant ring” to the reporter who recorded them (“Executed” 1890, 6). At a moment when Black men were increasingly represented as soulless beasts, Johnson’s spiritual triumph on the gallows challenged the premises of radical white supremacy. Black men in stories like this one were Christians, not beasts.

Other reports in this period anticipated or promoted the rise of radical white supremacy by portraying Black men in demeaning and dehumanizing ways. When Charles Tommey was executed in Georgia in 1877, the Constitution described him as “weighing from 190 to 200 pounds, and about six feet, three or four inches high, well-built and ferocious looking, showing great strength and brutal passion,” drawing conclusions about the man’s deportment from the study of his body (“A Life” 1877, 1). The Picayune described John Alexander in bovine and simian terms: “with a bull neck and round head. In appearance he displayed typical African features—flat nose, projecting jaw, protruding lips, retreating forehead, woolly hair, and Black complexion” (“Dropped Dead” 1885, 3). Writing about the execution of George Morris, the newspaper’s reporter told readers that his dark eyes “gleamed with passion and his lips trembled with the force of the ungovernable instincts that raged within him” (“Death” 1877, 2). Sometimes the coverage of a condemned Black man’s body reinforced racist logic in unexpected ways. Hardy Hamilton, the Constitution reported, “was a stalwart and handsome negro of rather light complexion and of apparently more than unusual intelligence. His face was prepossessing, and he had no appearance of being a cold-blooded murderer” (“Hardy Hamilton Pays” 1889, 1). This “flattery,” of course, reinforced broader norms about the relationship between a dark physique and intractable criminality. In 1898, near the high-water mark of radical white supremacy, the Picayune described Antoine Richard, the leader of a trio of Black highwaymen, as having “inherited the blood-thirsty nature of his African ancestors” (“St. Charles” 1898, 6).

In this type of reporting, the primary purpose of the executions of Black men seemed to be striking fear into the hearts of the Black population. Charles Tommey’s “dying advice” in 1877 was to “the colored people … to do better” (“A Life” 1877, 1). In 1882, Jesse Williams “spoke for ten minutes warning his colored brethren to lead better lives” (“Williams’s Wring” 1882, 5). While Allen Fuller’s execution was held in private, authorities decided to put his body on display for the public after he was cut down from the gallows. For an hour following the execution, a single-file line of people, Black and white, snaked into and out of the jail yard to see Fuller’s remains. “It is believed that the viewing of the remains by the crowd will serve to impress on the negroes the fact that the law will be carried out,” the Constitution explained (“Allen Fuller’s Neck” 1900, 3). In turning Fuller’s body into an object lesson exclusively for African Americans, the newspaper reinforced a vision of the Black population as criminally inclined and governed by fear rather than morality. In December of 1905, nine months before rumors of a crisis of Black men raping white women would lead to the massacre of at least two dozen African Americans in Atlanta, the sheriff of Fulton County, Georgia, oversaw the execution of Jim Walker. He used the occasion to stoke the myth of the Black rapist that preoccupied the minds of white southerners in an age of radical white supremacy. “You colored men must understand that you cannot pollute our white women; that you cannot lay your hands upon them,” the sheriff told Walker and—via the Constitution—the “people of [Walker’s] race” (“Crime’s Penalty” 1905, 7).

Reporters sometimes linked Black criminality to the demise of chattel slavery. To the Atlanta Constitution journalist who covered the 1892 hanging of Sherman Brookins, it was no coincidence that the condemned man had been named for the Union General William Tecumseh Sherman. His violent nature, the Constitution speculated, “may have been some subtle effect left by that great moving mass of humanity, Sherman’s army, which caused that restless spirit in Sherman Brookins; causing him to wander to and fro in the earth. It may also have caused him to follow as he did deviltry as a vocation and rascality as an avocation” (“Down” 1891, 2). In its coverage of William George’s execution in Louisiana in 1886, the Picayune attributed the condemned man’s violence to an uppity nature that had its origin in emancipation. The paper traced George’s personal history as a “pioneer emigrant” from post-Civil War Louisiana to Kansas, where he became a “Pension Agent, preacher, and would-be leader of his race” before returning to Louisiana. Freedom, the paper implied, imbued George with a kind of self-image that encouraged lawlessness: he was “one of the many colored people who have of late come to grief because a little learning is a dangerous thing” (“The Hangman’s Harvest” 1886, 1). In moments like these, journalists linked Black crime not only to racial difference but also to Northern victory in the Civil War.

Execution reporting could also reinforce an image of Black men as incapable of the moral and spiritual work necessary for redemption. Newspapers marveled at the nonchalance of Black men on the cusp of execution. Sang Armor, the Constitution reported, spent the morning of his execution “unconcernedly eating peanuts” (“The Gallows” 1881, 1). Likewise, William George, a Picayune reporter noted, was “as cheerful as any person could be who was going to make an ordinary pleasure trip.” George’s lack of respect for the occasion suggested a spiritual shallowness that the newspaper claimed was common among African Americans. George’s confident assertion that he was “heavenward,” the journalist told readers, was “the same old story that used to gratify and excite the colored crowds before executions were ordered to be private” (“The Hangman’s Harvest” 1886, 1). From the perspective of white reporters like this one, African Americans’ religiosity was a marker of their collective immaturity. In one 1897 execution story, the Constitution wrote that Terrell Hudson went to his death “a driveling and maundering idiot” who “could not have told his name, the date of his birth, the hour of the day, or the day of the month.” The newspaper blamed the religious fervor of Hudson’s family. His relatives’ “groaning and moaning” was like “chloroform” to reason and proper penitence. “[A]ll were in a frame of mind which is best described by the exultant shriek of one of the ministers, who said: ‘You’se in heaven now, Terrell. De angels is a carrin’ your soul straight to God. You’se in de glory of de light of de blessed Lam’. Jes’ wait for us. We’re a-comin’” (“Hudson’s Neck” 1897, 5). Such mockery undermined Christianity as a domain in which Black people might claim equality with white people.Footnote 7

While some execution reports humanized Black men and others demonized them, coverage that did both was common. While some articles were strikingly sympathetic to the condemned and others nakedly hostile to them, the majority fell somewhere between the two poles, offering contradictory constructions of condemned men. For instance, one can find in the same article the racist description of a condemned man’s physique and the sympathetic rendering of that same man’s efforts to reconcile with the family of his murder victim. In 1890, the Constitution reported that Bob Hill, sentenced to death for the murder of a white store owner during a robbery, arrived at the site of his hanging without having tended to his soul. The “burly, thick-set, brutal looking negro” had “little concern for his crime or his approaching end,” the newspaper noted. The ministers “of both races” who had visited him in his cell declared him a “vile rebel” on the morning of his execution. On the execution platform, however, when Sheriff Shurley asked Hill if he had any final words, the condemned man responded, “I hope you’ll all meet me in a better world.” The sheriff seemed moved. “You have hopes then, Bob?” the sheriff asked in a “kindly” manner. When Hill said he did, the sheriff responded encouragingly: “That is very gratifying, Bob.” Even more gratifying to the sheriff was what came next. Hill publicly asked his victim’s brother for forgiveness. The brother stepped forward, and “after some hesitation, replied, ‘I’ll try to forgive you, Bob’” (“The Rope Route” 1890, 1). In the course of the article, Hill transforms from a “vile rebel” who was narrowly saved from a lynching to a remorseful man who has received hope for forgiveness from his victim’s brother.

In other stories, the contradictory imagining of the condemned man was not part of a “once was lost, now am found” story of transformation. It was instead the result of the tension between reporters’ racism and the cultural script of sin and redemption that had historically shaped execution narratives. Take, for instance, coverage of the execution of Leonidas Johnson, who in 1884 had narrowly avoided a lynching in Georgia after having been accused of raping a white woman, the wife of a “well to do farmer.” The Constitution initially described Johnson as a beast, “low and compactly built, a stubborn eye and a neck thick and short like that of a bull, a heart as Black as the ace of spades…. Petty thief, burglar, escaped convict, rapist, and meat for the gallows—he was all these.” The reporter described his execution as if it were a commercial attraction. Ten thousand spectators had shown up for the event, the Constitution said, including “boys and girls, and even the merest toddlers who could stump around the scene.” The commodification of Johnson’s death would not end when he stopped breathing, readers learned. His body would be turned over “to do service in the case of science on the dissecting tables of the Georgia Eclectic medical college.” It would be “pickl[ed] until winter when the students will get a carve at it” (“Into Eternity” 1884, 1, 5).

And yet the cultural script of executions—with its allocation of time for the condemned man to speak—introduced an element of unpredictability into the execution spectacle that temporarily humanized Johnson in front of the crowd that was so eager to see him die. Johnson asked how many of the spectators sympathized with his plight and looked disappointed when only about a dozen people held up their hands to indicate that they did. And yet as officials led the crowd in a hymn, the people’s attitude toward Johnson showed signs of change. When Johnson’s deep bass voice sang “This the way I long have sought,/and mourned because I found it not,” the newspaper reported, “a feeling of astonishment overspread the crowd.” The reporter described a wave of “half sympathy” felt by the crowd for Johnson as he sang, “Nothing but sin have I to give./Nothing but love shall I receive’” (“Into Eternity” 1884, 1). In this moment, what had been a thinly veiled lynching became reminiscent of an execution in Puritan New England, when ministers encouraged crowds to see the condemned as an embodiment of the sinful humanity that lay within them all (Halttunen Reference Halttunen2000). Johnson became more than mere “meat for the gallows.” The logic of white supremacy was interrupted, its binaries muddied. Such ambiguity abounded in execution reporting. A story that ridiculed African Americans’ cognitive and moral faculties could simultaneously reinforce a fundamental dignity that resided within them and entitled them to sympathy and even compassion.

BLACK AGENCY, WHITE ANXIETY

Anxiety about the political opportunities that execution rituals afforded the condemned was sometimes evident in newspaper coverage of their executions. Since the eighteenth century, published narratives of Black crime and punishment have revealed white discomfort with Black people’s presence in American society. Crime narratives—especially those involving rape—revealed the fear of violent political rebellion people of African descent inspired (Slotkin Reference Slotkin1973). Widely circulating accounts of the antebellum executions of free and enslaved African Americans, moreover, gave Black people on the verge of execution a public presence that was denied to them in life. Literary scholar Jeannine Marie DeLombard argues that climbing up the stairs to the gallows perversely signified an “extraordinary ascension from the civil death of the slave (or the civil slavery of the free African American) into legal personhood” (Reference DeLombard2012, 92). As much as crime, punishment could be an occasion for displays of Black agency that white supremacist regimes normally worked to suppress.

The 1883 execution of Taylor Bryant in Georgia illustrates how challenging it was for white authorities to control the meanings of executions. Bryant had been sentenced to death for the prototypical lynching crime of raping a white woman. At his sentencing, the Constitution reported, the judge had called him an “unmitigated brute” who was driven by “animal passions” and “unfit to live.” The newspaper adopted this view of Bryant, describing him as a “wretch” with “the face of a hardened criminal …whose wayward life led through a variety of crime to this dismal doom.” Nonetheless, the newspaper reported details that undermined its portrayal of Bryant as a beast. Bryant refused to play the role assigned to him on the gallows. “You look on me as vile, but I am pure in heart,” he told the mixed-race crowd of six thousand who had gathered to witness his execution. He declared his innocence of the crime for which he was being put to death and named white racism, rather than Black crime, as the reason why he had been “brought … on this stage to die.” “When anything is done it is laid on the poor niggers,” he bluntly said to the crowd before going on to describe his experience witnessing, as a twelve-year-old boy, two white men murdering with impunity a Black man in a riverboat. When he named one of the men as the son of a prominent local doctor, some in the crowd shouted back at him, calling his accusation “a damned lie.” What could not be denied, though, was Bryant’s “nothing left to lose” resistance to white supremacy. The newspaper even conceded, with a kind of perplexed admiration, that his “speech was remarkably distinct and emphatic in every particular. He spoke very correctly and had rather less than usual of the ‘hallelujah lick’ in his remarks” (“Taylor Bryant’s Throat” 1883, 1). The “unmitigated brute” was, according to the newspaper’s own journalist, a stereotype-defying speaker of “correct” English.

The newspaper’s coverage of the African American witnesses of the execution was equally contradictory. At the beginning and end of the story, the Constitution described them as drunk on whisky, “especially talkative,” and manifesting an “unfeeling curiosity which usually characterizes such occasions.” And yet after he addressed the crowd, the reporter noted, an African American minister, Reverend J.H. Hall

then said that the prisoner wanted the crowd to sing for him. He gave out line by line the familiar hymn… Hundreds of the crowd joined in the song, the doomed man singing clearly and calmly with the rest. As the music rang through the pines several negro women began to shout, and one negro man screamed out, ‘You see Jesus on de cross! He say its finished. He say it suffice. Glory!”

When the minister asked the crowd to pray, “a thousand heads were uncovered in an instant and clear above the silent thousands rose a beautiful prayer from the lips of the Black minister” (“Taylor Bryant’s Throat” 1883, 1).

As public events in which Black ministers shared execution platforms with white sheriffs and stood before interracial crowds, the executions of Black men stood as a glaring exception to the Jim Crow segregation laws that whites were enacting across the region. Under the cover of a hard-to-assail Christian religious authority, African Americans could challenge radical white supremacy at events that were intended to strengthen it. Indeed, historian Michael Trotti has characterized the atmosphere at some executions of Black men as “revivals,” arguing that when they cried out or prayed in unison at executions, Black witnesses claimed a “public and vocal role of authority” and undermined the radical white supremacy on which Jim Crow laws were built (2011, 209).Footnote 8

Indeed, the reporting of Taylor Bryant’s execution reveals a tension between a white fantasy of Black inferiority and a reality of Black political potential. The journalist seemed to want to frame the execution in ways that reinforced white supremacy. He depicted the Black criminal as beastly. He portrayed the Black community as uncivilized and unruly, yet ultimately disorganized and apolitical. But Bryant’s eloquence and sincerity was impossible to ignore. Black witnesses to the execution, meanwhile, seemed energized by Bryant’s assertion of the limits of white execution violence (“My body will die but my peace is made with God and I am going to him,” he said at one point). They doffed their hats for Bryant, sang in unison, and shouted encouraging words. Their potential political solidarity with Bryant is evident to the critical eye despite the reporter’s efforts to dismiss them as imbibers of Black, “hallelujah lick” religiosity (“Taylor Bryant’s Throat” 1883, 1). When one member of Bryant’s community yelled out that “Jesus say it suffice,” he was doing more than offering words of consolation. By reminding all in attendance that Jesus died for Bryant’s sins, he was challenging the radical white supremacist premise that Black people were beasts. Beasts could never be the candidates for heaven that Black execution witnesses insisted that the condemned were.

The frequency with which reporters would comment on the deportment of African Americans who witnessed executions suggests that the threat of Black political consciousness preoccupied many whites. When Black people came “flocking in on horseback from all parts of the country” to be present for the 1882 executions of Sterling Ben and Terence Achille in Louisiana, the Picayune made it a point to tell readers that as “the hour for the execution arrived a number of deputy sheriffs were appointed by Sheriff Gordy and placed in the most convenient positions to preserve order and quell the slightest disturbance” (“Execution in St. Mary” 1882, 2). And when the state hanged the brothers Albert and Charles Goodman in 1884, the Picayune nervously noted that the Black population was unhappy with the execution, feeling as if the state was overzealously targeting its own and that the evidence of the brothers’ guilt was too thin. Fear of a rescue attempt was so great that white men slept in the jail with guns at the ready on the night before the execution. Such coverage reveals white anxiety about the potential for Black rebellion. The papers sometimes tried to diffuse that anxiety. Ultimately, the reporter told the Picayune’s reader, Black anger about the Goodman brothers was nothing but “braggadocio and whisky.” One Black man said he was “going to get rough,” but, the reporter joked, “[a]s he was not seen around the execution it is supposed that the bottle of whisky was rough on him only” (“Execution in St. Bernard 1884, 8). In such mockery, though, the discerning reader can sense a more complex reality of white fear of Black resistance.

FLATTENING THE NARRATIVE, 1907–1936

I have argued that tension over the status of African Americans in the South shaped coverage of their executions in the first three decades following Reconstruction. While anti-Black racism infected Southern white journalists’ reporting on Black executions, it could at times be upstaged by the traditional attention reporters paid to questions of agency, moral responsibility, and grievability. Materially, these executions annihilated Black people. Symbolically, however, they were not guaranteed to reinforce racial hierarchies.

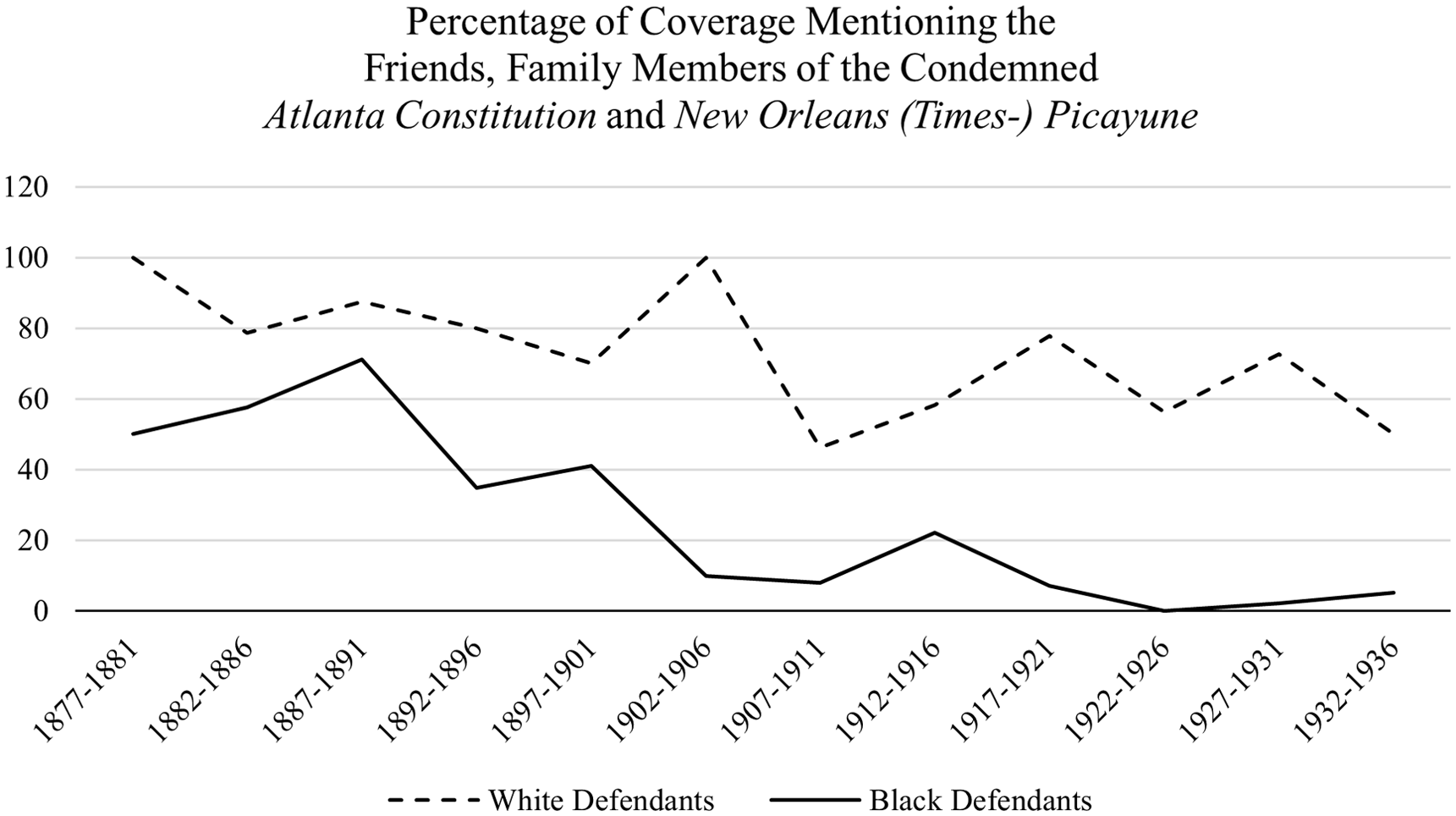

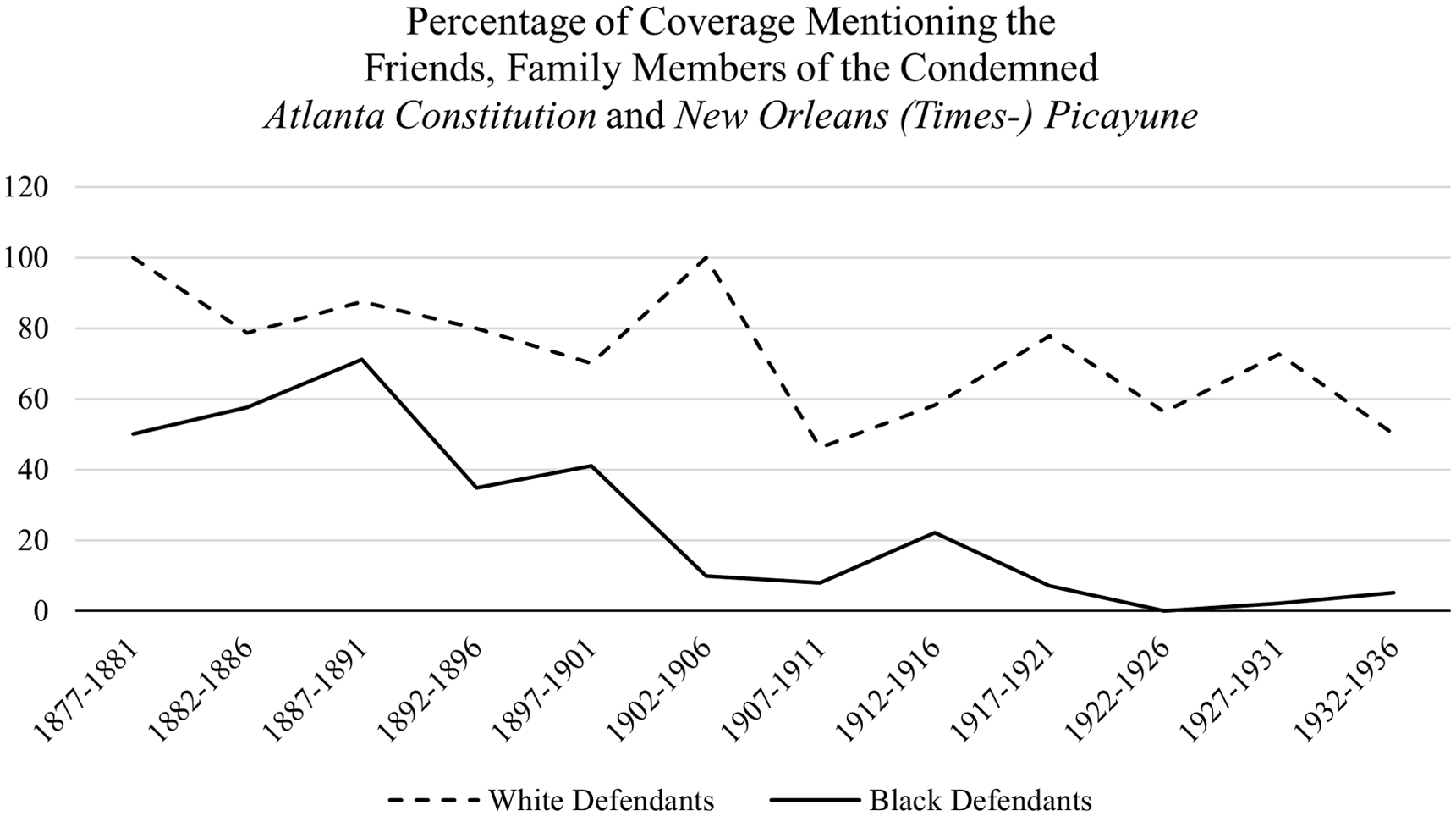

Toward the end of that period, from the mid-1890s to the mid-1900s, execution reporting changed as radical white supremacy reached the height of its influence in Southern life. The median length of articles covering Black men’s executions shrank 75 percent in the 1890s as radical white supremacy took hold—from 16 paragraphs to four. As the amount of attention to Black men’s executions shrank, elements of execution stories that had served to humanize them often disappeared altogether. The voices of condemned Black men became scarce in execution reporting. In the late 1880s and early 1890s, journalists quoted Black defendants in 74 percent of their execution stories. By the first decade of the twentieth century, the rate at which those men’s voices appeared in execution coverage had fallen nearly 60 percent to 13 percent (Figure 2). Even more dramatic was the disappearance of the family and friends of condemned Black men from execution coverage. Until the 1890s, mentions of condemned Black men’s friends and family appeared in 50 to 71 percent of execution reporting. In the first decade of the twentieth century, the percentage of articles mentioning loved ones fell to 8 percent (Figure 3). To be sure, the decline of these humanizing details in execution reporting about condemned Black men was not perfectly linear and has some notable exceptions (a noticeable rebound in the 1920s of articles that quote condemned, for instance). But the median length of articles remained short—as low as two paragraphs and as high as four and a half—even in periods where these details were more prevalent. Some articles announcing the executions of Black men were only one sentence long.

Figure 2. Percentage of Execution Coverage Quoting the Condemned Person in the Atlanta Constitution and the New Orleans (Times-)Picayune.

Figure 3. Percentage of Execution Coverage Mentioning the Friends and Family Members of the Condemned Person in the Atlanta Constitution and the New Orleans (Times-)Picayune.

By the time Georgia executed Charlie Jasper in 1920, a more bare-bones approach to the coverage of African American men’s executions had taken hold in the Constitution and the Times-Picayune. The story about his execution that the Constitution published was headlined “Negro Pays Penalty of Crime on Gallows” and read, in its entirety,

Charlie Jasper, negro, who was convicted less than a month ago, charged with assaulting a white woman near Grant Park, paid the penalty for his crime on the gallows in the Fulton county tower Friday morning.

Jasper made a full confession at his trial which took place several days ago. The screams of the victime [sic] attracted City Detective Moseley, who rushed to the scene and shot and wounded the negro as he tried to escape. He was later carried to Grady Hospital and then to the Tower. (“Negro Pays” 1920, 4)

The account of Jasper’s execution was typical of stories announcing the executions of Black men in the first decades of the twentieth century. His voice is absent. The reporter made no mention of his family or friends. Both the crime and the punishment are described in an unsensational way. Sometimes accounts of Black men’s executions in the Constitution and the Times-Picayune went beyond the basics and would mention that a defendant had asserted his innocence while being strapped into the chair or had words of advice to deter other young (and presumably Black) men. But they rarely elaborated upon the emotional effect that being condemned to death had on him or his family. They almost never included a photograph of the man. And headlines for these executions rarely included the defendant’s name, denoting him instead by his race (“Negro”), his crime, or some combination thereof (“Negro Slayer”).

When coverage of Black men’s executions was longer, it was often because they were executed on the same day as a white man and were briefly noted in stories primarily focused on the white defendant. For instance, when Herbert Fennell, a Black man, was put to death by Georgia in 1927, the Constitution briefly noted his execution in a thirty-two-paragraph article that centered almost entirely on the execution of a white man, Mell Gore (McCusker Reference McCusker1927). An analogous kind of disparate treatment can be seen in the Times-Picayune’s coverage of Ito Jacques’s execution. Along with three white men, Jacques—a Black man—was executed for the murder of a white grocer during a bank robbery. The paper printed separate photographs of each of the three white men, but not Jacques. For readers of the newspaper, he died faceless (“Four Bandits Die” 1932). The absence of Jacques’s face captures the broader substantive changes in how newspapers covered the executions of African Americans. Once presented as members of communities that would mourn their loss, condemned Black men increasingly appeared in reporting as ciphers.

Why did coverage of Black men’s executions shrink in these two newspapers as radical white supremacy took hold across the South? The gradual transformation of executions from public spectacles to private bureaucratic affairs is one potential answer. As early as the 1850s, Southern states passed laws that sought to limit the public’s access to executions. The laws were initially unpopular and difficult to enforce. Executions were exciting events, and many ordinary people felt entitled to witness them firsthand. Some elites, moreover, worried that carrying out death sentences in private would remove a powerful deterrent to Black crime. Others worried that, denied access to executions, whites would turn to lynching to satisfy their desire for public punishment. These concerns put pressure on sheriffs charged with carrying out executions to find ways to maintain them as public or quasi-public events (Trotti Reference Trotti2011). Even after Louisiana and Georgia redoubled its efforts to end public executions with new, stricter legislation in 1884 (Louisiana) and 1893 (Georgia), newspaper reports into the 1910s revealed that some sheriffs continued to flout the law (Pfeifer Reference Pfeifer2004; Trotti Reference Trotti2011). Eventually, though, anxiety about Black execution crowds combined with other factorsFootnote 9 to end the South’s tradition of public executions (Trotti Reference Trotti2011; Kotch Reference Kotch, Wood and Ring2019a; Miller Reference Miller, Wood and Ring2019). By the 1920s, executions in Georgia and Louisiana were consistently carried out in spaces that were fully enclosed. It is tempting to conclude that the transformation of executions into bureaucratic affairs conducted behind closed doors led to shorter, less sensational execution reporting. Without the rituals of public executions and the opportunities they created for dramatic displays from the condemned, their spiritual advisors, or their communities, there was theoretically less for journalists to write about.

And yet reporters still found much to write about when the condemned were white. Well into the 1920s and 1930s, coverage of white men’s executions in the Constitution and the Times-Picayune could take the form of the sentimental execution narratives that flourished in the late nineteenth century. In an article that was sixty paragraphs long, journalist Meigs O. Frost made the Reference Frost1934 executions of John Capaci and George Dallao in Louisiana into a melodrama. He wrote about everything from the “execution-morning consolers” in the upper corridor of the jail who sang hymns to the men to Dallao’s decision to bequeath a little ivory elephant his child had given him to a deputy sheriff who “took it, tears running down his face” (1934, 9). Meanwhile, the Associated Press coverage of the 1931 execution of Burley Adams regaled readers of the Constitution with the “tragic scene” in Adams’s cell as “a strong young man said goodbye to his wife—and walked away to his death. A steel door opened in the death chamber. The watchers saw Adams walk in…. Although several men followed him, he seemed entirely alone in a room full of people. He cast his eyes around the room and sat on the big white throne of death” (“Adams Pays Price” 1931, 6). Both executions were private affairs, but journalists turned condemned white men into tragic heroes and newspaper readers into surrogate witnesses to dramas of life and death. The presence of stories like these teach us that the privatization of executions was perhaps necessary for the changes in Black execution reporting, but it was not sufficient.

To understand the change in Black men’s execution reporting more fully, we need to consider it alongside the rise of lynchings as the dominant mode of lethal punishment visited upon Black people in the South. From the 1870s to the 1920s in Georgia and Louisiana, white mobs lynched African Americans at 1.2 to 2.5 times the rates at which the state executed themFootnote 10 (Figure 4). In the 1890s, public, spectacle lynchings of Black men emerged across the South as a new and especially horrifying form of anti-Black terrorism. Conducted in public in front of crowds that could number into the thousands, the lynchings made whiteness by publicly negating Black people’s status as fellow human beings endowed with legal rights and eternal souls. In the torture they inflicted on their victims, lynch mobs made a mockery of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments and their guarantees of due process and democratic participation in governance. Burning some Black men alive, cutting off others’ tongues and genitals, mobs portrayed African Americans as beings without the capacity to speak for themselves, without a future, without any right to property in their own bodies, without any entitlement to protection by the state (Kaufman-Osborn Reference Kaufman-Osborn, Ogletree and Sarat2006). And by turning lynching victims’ bodies into memorabilia in the form of photographs of the posthumous victim or pieces of their bones, mobs symbolically nullified the Thirteenth Amendment, returning Black people to the status of circulating property (Kaufman-Osborn Reference Kaufman-Osborn, Ogletree and Sarat2006). Lynching, in other words, insisted that Supreme Court justice Roger Taney’s infamous holding in Dred Scott v. Sandford—that people of African descent had “no rights which the white man was bound to respect”—was still good law (1857, 407).

Figure 4. Combined Lethal Punishment rates in Georgia and Louisiana (Per 100,000 People). Source of Execution Data: Watt and Smykla (2002). Source of population data: Gibson and Jung (Reference Gibson and Jung2002). Source of lynching data: Tolnay and Beck (Reference Tolnay and Beck2022).

Public lynchings were more than a form of legal and political excommunication, though. They called into question the existence of their Black scapegoats’ souls. Excluded from scenes of lynching, Black community members could not offer spiritual comfort to the victim or invoke a racially inclusive version of Christianity, one in which they were God’s children too. In their absence, white mobs invoked a version of Christianity that was firmly wedded to radical white supremacy. At its heart was the belief that white racial purity—and violence undertaken to protect it—was holy (Mathews Reference Mathews2018). Seen as demonic pollutants rather than wayward souls, the victims of lynch mobs were often denied the opportunity to repent their sins or pray for their souls. If the mob did let them talk to God, it would sometimes use their words to consecrate the violence visited against them (Kotch Reference Kotch, Wood and Ring2019a).

Public lynchings worked to forge white identity in the era of radical white supremacy. While most lynchings were not public spectacles, those that were had outsized political and cultural significance as events that generated white social solidarity (Hale Reference Hale1998; Wood Reference Wood2009; Smångs Reference Smångs2017). Studying when and where public lynchings occurred, sociologist Mattias Smångs has shown that they were not merely a symptom of radical white supremacy. They “crucially forged the racial imaginations, experiences, relations, and institutions upon which the Jim Crow system rested” (2017, 2). Public lynchings, in other words, “did not signify an existing racial order as much as they gave rise to one,” replacing a form of white racial identification that understood African Americans as children with one that imposed a “rigid exclusionary social boundary” between Black and white. It was no coincidence, he argues, that public lynchings were more common in counties with higher levels of intra-white class tensions or political party differences (2017, 2, 84). By dramatizing the existential threat that Black criminality posed to all whites and vanquishing that threat in a spectacular act of collective violence, public lynchings bridged differences among whites who witnessed them directly or read about them in newspapers.

Executions were far more ambiguous in their construction of Blackness than public lynchings, which violently and ritualistically degraded their Black victims (Harris Reference Harris1984; Wiegman Reference Wiegman1995; Gunning Reference Gunning1996; Hale Reference Hale1998; Markovitz Reference Markovitz2004; Wood Reference Wood2009). This may be why, as radical white supremacy took hold across the South in the 1890s, lynching far exceeded executions as the predominant form of lethal punishment meted out to African Americans. Joel Williamson has argued that the torture and mutilation that characterized lynchings sprang from the idea that “simple hanging was thought to be too noble an end for such a wretch…. Burning, riddling with bullets, mutilation, and exhibition were used both before and after death to demean the victims” (1986, 125). A mob that lynched C.J. Miller in Bardwell, Kentucky in 1893, for instance, explicitly chose a “large log chain” to hang Miller because “rope was ‘a white man’s death’” (Benjamin Reference Benjamin1894, 45, quoted in Wood Reference Wood2009, 42). If an execution-like lynching seemed too soft to lynch mobs, it is likely that actual legal executions seemed even more inappropriate. Execution rituals portrayed the condemned as everything the Black lynching victim was not: rights bearing, self-owning, redeemable, grievable, and protected from capricious violence.

In contrast to public lynchings, I argue, newspaper reporting on executions made whiteness in a different and surprising way: not by galvanizing anti-Black sentiment among whites, but by portraying the legal executions of white men as events that honored their humanity. In the outsized coverage of white men’s executions that appeared on the pages of the Constitution and the Picayune, an execution appeared to be everything a lynching was not: a punishment that respected the dignity of those who suffered it. This transformation was most evident in the 1890s and early 1900s, when the median coverage of white men’s executions was between forty and eighty paragraphs long. But while coverage of white men’s executions shrank substantially in the late 1900s and 1910s, they retained their humanizing dimensions. Well into the 1930s, white men who were put to death on the Louisiana gallows and the Georgia electric chair continued to embody the qualities of legal and Christian personhood. As their executions drew near, journalists continued to depict them asserting their honor, seeking redemption, demonstrating fortitude, and finding ways to provide for their families.

From one vantage point, this finding is surprising. The white men put to death in Georgia and Louisiana were often from the lower classes. They had committed terrible crimes, often against more respectable white men. But if we think of execution reporting in the early twentieth century as a site of making whiteness, these portrayals make more sense.Footnote 11 White racial consciousness, as we have seen, had worked to displace white class consciousness and bridge intra-white political divisions. If framed improperly, the violence of white men’s executions might have disrupted the bonds of whiteness, casting an uncomfortable light on poor whites preying on their middle- and upper-class counterparts. By treating condemned white men as fallen humans rather than vicious beasts, journalists protected white social solidarity. The condemned may have done awful deeds, the coverage seemed to say, but they retained an inviolable dignity. Redemption was still possible.

We might interpret this treatment of condemned white men as part of the social capital whites possessed—the “public and psychological wage,” their racial identity garnered for them, as W.E.B. Du Bois put it (Reference DuBois1935, 700). As Mattias Smångs notes, “gentleman” and “lady” lost their class connotations and became markers of whiteness in the Jim Crow South: “a lower-class white man could be a ‘gentleman’ and a lower-class white woman a ‘lady,’ whereas African American men and women could as far as whites were concerned never achieve the honorability or respectability of ‘gentlemen’ or ‘ladies’” (2017, 121). Journalists extended this privilege to a good number of condemned white men. In execution narratives the white criminal sometimes seemed to transform from a bandit into a gentleman. Proximity to death seemed to confer newfound nobility upon him. When Frank DuPre, a former sailor, was put to death on the Atlanta gallows in 1922 for the murder of a security guard during the robbery of a jewelry store, the Constitution made him seem heroic: “He faced his supreme ordeal as he faced the trial for his life, cool, collected, unemotional. In the dreadful walk from the condemned tier to the death cell and up the fatal steps of the scaffold, there was not a suggestion of either a physical or nervous collapse. Whatever his crimes in life may have been, he obeyed implicitly the parting injunction of his heart-broken and half-crazed father, who had pleaded with him to meet death like a man. In the words of the great man of Avon, ‘nothing so became his life as his leaving of it’” (Woodruff Reference Woodruff1922, 1). DuPre and others of his ilk became tragic heroes, their punishments the occasion for reflection on their capacity for goodness. Du Bois once remarked that Southern newspapers “specialized on news that flattered the poor whites and almost utterly ignored the Negro except in crime and ridicule” (1935, 700, quoted in Smångs Reference Smångs2017, 145). In execution articles, white criminals seemed to become the beneficiaries of this white racial uplift. In what should have been the worst of whiteness, readers encountered glimmers of nobility.

CONCLUSION: EXECUTION AS A HIGH-STATUS FORM OF LETHAL PUNISHMENT

Studying the relationship between capital punishment and lynching in the South, historian Seth Kotch has argued that the two were “complementary forms of social control” and “mimetic methods of racial subjugation that [Southerners] at the time saw as in conversation with one another” (Reference Kotch2019b, 18). Lynchings and executions, he writes, “expressed the essential violence at the core of a white supremacist social and political system” and reinforced white social solidarity (2019a, 202). Over time, the two forms of lethal punishment seemed to merge. When executions became private events held inside buildings, elites excluded Black community members from them. As white men gathered to kill Black men without Black witnesses present, executions looked more like lynchings. This may be why, by the 1940s, those writing about vigilante violence in the South observed that the promise of an execution could placate would-be lynch mob members (Ames Reference Ames1942; Myrdal Reference Myrdal1944). Jesse Daniel Ames wrote in a report that “in more than one prevented lynching a bargain was entered into between officers and would-be lynchers before the trial began in which the death penalty was promised as the price of the mob’s dispersal” (1942, 12, quoted in Faber Reference Faber2021, 47–48). In such cases, lynchings were not so much prevented as they were legalized.

Kotch’s focus on the similarities between lynching and capital punishment powerfully explains how the death penalty became a functional surrogate for lynching in an era of modernization. But as executions became private and journalists’ capacity to shape the image of an execution grew, the face of capital punishment changed in important corners of the popular imagination in ways that distinguished it from lynching. Most obviously, the condemned seemed whiter than they actually were. Imagine, for a moment, a daily reader of the Constitution from 1897, when radical white supremacy began its decade-long peak in the South, to 1936, when the last public execution in the United States occurred. During this time, the newspaper reported on the executions of 302 men in Georgia, sixty-one white (20.2 percent) and 241 Black (79.8 percent). But nearly half (45.8 percent) of all the paragraphs reporters wrote in their coverage of these 302 executions would be about the small minority of white men the state put to death. In most of the articles this reader encounters about those white men’s executions, she “hears” their voices and is reminded of their family. She sees images of the faces of one out of every six of them. In contrast, she rarely hears the voices of condemned Black men and is almost never reminded that they are leaving family behind. She will see just three of their 241 faces.

In the image of capital punishment that these newspapers created for readers like this one, an execution was a terrible, awe-inspiring display of the state’s power. It justly punished men who had committed heinous crimes. But in stark contrast to the lynch mob, the state often seemed to take the lives of white men. And when it claimed their lives, it seemed to affirm the value of an inviolable “personhood”—spiritual, legal, political—that lay within them. And rather than ritualistically demonizing and degrading the Black men it put to death, as the mobs who carried out public lynchings did, the state seemed to treat condemned Black men with a kind of technocratic indifference. In newspaper coverage of their executions, condemned Black men increasingly appeared as faceless, interchangeable public safety hazards the state was neutralizing with little fanfare.

By attending only to the material effects of executions and treating them as a functional equivalent of lynching, we overlook the process whereby capital punishment became constructed as an anti-lynching in important corners of the Southern cultural imagination. As newspapers and other widely circulating media like novels and films broadcast a Kantian vision of legal executions, it would become easier for those who wanted to project a modern image of the South to distance capital punishment from lynching, a form of violence that was becoming a source of embarrassment for respectable white Southerners. Executions in the South were so often legal lynchings. Yet in images of white men nobly meeting their deaths, journalists made respect for law and human dignity compatible with the practice of legally strangling and electrocuting human beings to death.