Introduction

In the United Kingdom, complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) therapies are predominantly delivered and accessed in the private sector, but they have long had a foothold in the public sector. Homeopathic hospitals have always been part of the National Health Service (NHS) and 40% of GPs referred to CAM therapies at the turn of the century (Thomas et al., Reference Thomas, Nicholl and Fall2001). The UK coalition government appears to want to encourage more access to CAM in the NHS (Secretary of State for Health, 2010), thus increasing the availability of CAM for those patients who cannot afford to access it in the private sector. However, truly equal access depends on the equivalence of the services being delivered in the public and private sectors. To explore the equivalence of CAM delivery across sectors, we wished to compare practitioners’ experiences of working in the NHS and private practice and we chose to focus our research on acupuncture.

According to a major European survey, 7.8 million people in the United Kingdom suffer from chronic pain, 35% of whom experience pain all the time and 12% of whom use acupuncture (Breivik et al., Reference Breivik, Collett, Ventafridda, Cohen and Gallacher2006). Acupuncture is currently available in the NHS via physiotherapy departments, hospital pain clinics, and primary care (Dale, Reference Dale1997; Thomas et al., Reference Thomas, Coleman and Nicholl2003). There is evidence that acupuncture is safe (White et al., Reference White, Hayhoe, Hart and Ernst2001), cost-effective (Wonderling et al., Reference Wonderling, Vickers, Grieve and McCarney2004; Ratcliffe et al., Reference Ratcliffe, Thomas, MacPherson and Brazier2006; Willich et al., Reference Willich, Reinhold, Selim, Jena, Brinkhaus and Witt2006), and effective for a range of painful conditions, including chronic lower back pain (Furlan et al., Reference Furlan, van Tulder, Cherkin, Tsukayama, Lao, Koes and Berman2005; Manheimer et al., Reference Manheimer, White, Berman, Forys and Ernst2005), neck pain (Trinh et al., Reference Trinh, Graham, Gross, Goldsmith, Wang, Cameron and Kay2006), shoulder pain (Green et al., Reference Green, Buchbinder and Hetrick2005), migraine (Linde et al., Reference Linde, Allais, Brinkhaus, Manheimer, Vickers and White2009a), and headache (Linde et al., Reference Linde, Allais, Brinkhaus, Manheimer, Vickers and White2009b). This evidence base has been formally recognised for some conditions, for example, acupuncture was officially recommended in the UK's National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence's (NICE) clinical guidelines for managing non-specific persistent lower back pain in primary care (Savigny et al., Reference Savigny, Kuntze, Watson, Underwood, Ritchie, Cotterell, Hill, Browne, Buchanan, Coffey, Dixon, Drummond, Flanagan, Greenough, Griffiths, Halliday-Bell, Hettinga, Vogel and Walsh2009). However, the major UK-based randomized controlled trial of acupuncture for back pain was conducted in a private sector environment (Thomas et al., Reference Thomas, MacPherson, Thorpe, Brazier, Fitter, Campbell, Roman, Walters and Nicholl2006), and this raises questions about the translation of evidence from one sector to another: To what extent is the acupuncture being delivered in the NHS the same as the acupuncture that has been evaluated and researched in the private sector?

To date, there have been few studies comparing NHS and private practice acupuncture in particular or CAM therapies more generally. Acupuncture can be seen as a complex intervention in which practitioners emphasise the therapeutic relationship and see themselves as providing individualised care (MacPherson et al., Reference MacPherson, Thorpe and Thomas2006a) and lifestyle/self-help advice (MacPherson et al., Reference MacPherson, Thorpe and Thomas2006a; MacPherson and Thomas, Reference MacPherson and Thomas2008). Acupuncturists deliver care in the context of their individual theoretical perspectives (eg, Western or traditional Chinese medicine; Hughes et al., Reference Hughes, Goldbart, Fairhurst and Knowles2007) and the wider power relations that exist between acupuncture and orthodox biomedicine (Saks, Reference Saks1992; Dew, Reference Dew2000). The actual ways in which acupuncturists currently deliver acupuncture care to patients in the NHS in comparison with the private sector has not been explored in depth, although evidence from studies of patients’ experiences suggests that there may be differences. CAM use in private practice is mainly self-directed directly by patients (MacPherson et al., Reference MacPherson, Sinclair-Lian and Thomas2006b), whereas GPs may play a role in referring patients to NHS-based CAM services. Although NHS patients are generally positive about accessing CAM in what is perceived as a safe environment (Shaw et al., Reference Shaw, Thompson and Sharp2006; Evans et al., Reference Evans, Shaw, Sharp, Thompson, Falk, Turton and Thompson2007), differences in patients’ experiences of acupuncture between the NHS and private practice have been identified, for example, in relation to holistic care (Paterson and Britten, Reference Paterson and Britten2008).

In summary, acupuncture is a safe and relatively cost-effective treatment for pain and can be conceptualised as a complex intervention. This project aimed to identify similarities and differences between private practice and NHS in practitioners’ experiences of delivering acupuncture to treat pain, with a view to informing our understanding of the relationship between the research evidence and clinical practice. This will also allow us to identify any differences that exist between these two clinical environments, which could affect patients’ experiences of acupuncture and their clinical outcomes. A qualitative approach was chosen to enable an in-depth and open exploration of the topic.

Methodology

Design

This study was based on face-to-face semi-structured interviews and inductive thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006). Ethics approval was received from the Southampton and South West Hampshire Research Ethics Committee (B) (Reference number 07/HO504/196).

Procedure

The search functions on the websites of two acupuncture associations (the British Acupuncture Council and the Acupuncture Association of Chartered Physiotherapists) were used to identify acupuncturists in Hampshire. A letter and information pack were sent to randomly selected acupuncturists, and those who expressed interest in participating were contacted by the researcher to establish whether they fitted the inclusion criteria (practised acupuncture within the last two years, over 18, fluent in English). Acupuncturists were also asked what sector they worked in and how long they had been practising acupuncture. Respondents were then purposively sampled in an attempt to interview a similar number of acupuncturists from the public and private sectors with some recently qualified and some more experienced acupuncturists. Recruitment stopped when no new themes were raised in interviews with acupuncturists in private practice and no more acupuncturists practicing only in the NHS could be recruited from the local area.

Each participant took part in a single semi-structured face-to-face interview with a student researcher (N.A.) between January and March 2009. The topic guide consisted of a series of open-ended questions. Set opening and closing questions were supplemented by questions probing specific aspects of practice to be used only if the topic was not initiated by the interviewee (Table 1). The approach to interviewing was a neutral, realist perspective where all information was taken as new and at face value. Interviews lasted between 24 and 77 min (median = 49 min), were audio-recorded, and transcribed verbatim with identifiable details removed and names replaced by pseudonyms. Transcripts (and quotations below) were annotated with (N), (P), or (B) representing, respectively, working in the NHS, Private sector, or Both sectors.

Table 1 Topic guide for semi-structured interviews

NHS = National Health Services.

Participants

Sixteen acupuncturists (14 women, 2 men) were interviewed: seven worked only in the private sector, three worked only in the NHS, and six had experience in both the sectors. Table 2 summarises the participants’ characteristics.

Table 2 Participants’ characteristics by health-care sector

NHS = National Health Services; CAM = complementary and alternative medicine.

Note: ×Indicates no participants working in that sector had that characteristic. ✓Indicates at least one participant working in that sector had that characteristic.

Data analysis

An inductive thematic analysis was undertaken following the steps suggested by Braun and Clarke (Reference Braun and Clarke2006). Analysis began as soon as the first three interviews had been completed. In Phase 1 (familiarisation), all transcripts were read numerous times and recordings were listened to extensively. In Phase 2 (coding), the lead analyst worked through the first three transcripts and generated low-level open codes (labels) that described each phrase. Similar codes were then grouped into categories and subcategories, which were applied to the remaining transcripts. In Phase 3 (searching for themes), categories and subcategories were reviewed and potential themes were identified. Table 3 shows the relationship between codes, subcategories, categories, and themes. In Phase 4 (reviewing themes), candidate themes were checked against the categories, subcategories, and transcripts, and modified where necessary to ensure a good fit (instances of ‘bad fit’ were deliberately sought out to inform this process). In Phase 5 (theme definition), themes were named concisely, defined clearly in relation to each other, and related back to the research question: talk about the NHS and private sector was compared for each theme. In Phase 6 (write-up), a storyline was developed that summarised the themes in relation to the research question and eloquent and/or typical quotes were selected to illustrate key points.

Table 3 The relationship between codes, sub-categories, categories, and themes

Findings

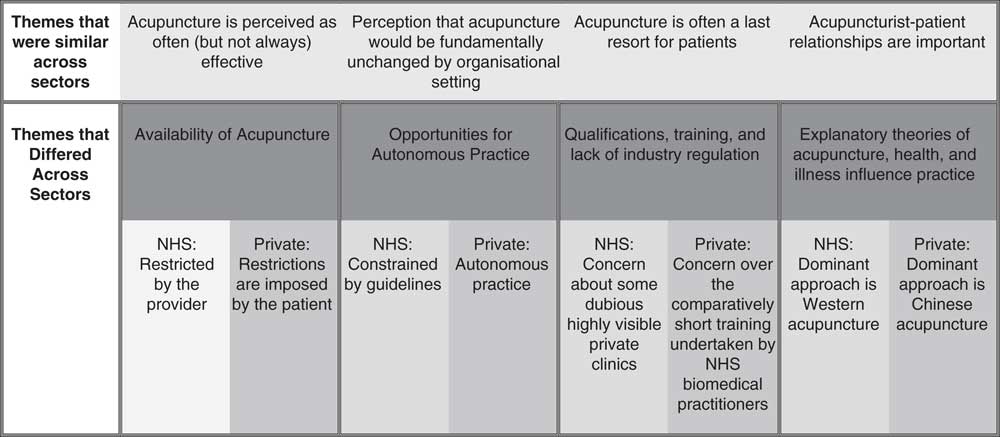

Eight themes were identified and are summarised in Figure 1. The interviewees talked in broadly similar ways across the NHS and private practice in relation to four themes; differences were identified in relation to the other four themes.

Figure 1 Thematic similarities and differences between the National Health Service and Private Practice

Similarities between NHS and private practice

The Perceived Effectiveness of Acupuncture was reported consistently across public and private sector practice. All practitioners typically reported that over half of patients obtained effective pain relief from acupuncture: ‘60% of my patients get 50% or more relief from acupuncture in the pain clinic’ (Annie, B). Acupuncture was seen to have additional effects beyond pain relief (eg, better sleep, relaxation, tiredness) in both the sectors. Dramatic examples of the effects of acupuncture were related by practitioners across both the sectors, but these were described as rare: ‘this lady had taken 6 months off work, was bent double and I just gave her one treatment and she walked out’ (Julie, P). Despite getting good results often, practitioners acknowledged that acupuncture is not effective for all patients and found it very difficult to predict in advance who would or would not respond well to treatment, and how long the effects of treatment would last. Factors commonly thought to predict positive responses include younger age, acute (rather than chronic) pain, and an immediate response to needle insertion. Patient expectation was not thought to predict response: ‘some of the best results have been in the really skeptical’ (Steph, N).

Practitioners felt that they did (or would) deliver acupuncture in broadly the same way in the NHS or in private practice: there was a Perception that acupuncture is fundamentally unchanged by health-care sector. They also typically favoured the provision of acupuncture in both the sectors. Multi-sector practitioners reported treating patients in exactly the same way in each setting, although they qualified their statements by reference to time constraints within their NHS practice.

I would practise the same way, with the same system and techniques. I do practise a small amount privately and I think the only difference is that in private practice I would have more time to spend with patients. (Harriet, B.)

Single-sector practitioners believe that they would treat in exactly the same way if they were to practise in another sector, for example, Gemma (P) said ‘It will be exactly the same treatment [in the NHS] but in half the time, you'll have 20 minutes instead of 40 minutes’. Some single-sector practitioners also attended to time as a limiting factor: private practitioners expressed concern over time constraints in the NHS, and NHS practitioners believed that they would have more time with each patient in private. Three broad similarities were identified in the ways in which acupuncturists perceived and delivered acupuncture across sectors.

-

1) Practitioners universally treated patients in accordance with their training, and this involved taking detailed histories, performing physical examinations, considering lifestyle and wider factors, and developing individualised treatment plans. (The manner in which these activities were accomplished did vary between sectors and is discussed later.)

-

2) Practitioners universally believed that acupuncture is a safe intervention with minimal side effects and a good alternative to long-term medication: a view that is sustained by the current evidence base.

-

3) Needling time was typically 20 min, and although there were variations (from ‘in and out’ to ‘up to 30 min’) these did not relate to sector.

Practitioners in both the sectors report that many patients access acupuncture as a last resort, frequently in desperation as no other treatment has been effective: ‘if it's long standing stuff people are just so sick of everything and they're so sick of taking pills specifically and the fact that no-one else seems to be able to do anything for them that they'll give anything a go’ (Hannah, P). Acupuncture can also be a last resort for some practitioners. Although some physiotherapists used acupuncture as a first-line treatment, others preferred to use their manipulation skills first or to use acupuncture in a supportive role to control pain sufficiently to enable them to perform other therapies.

Acupuncturist–patient relationships were important to practitioners across both the sectors. Practitioners referred to the therapeutic importance of listening to and getting to know the patient, especially given that many take up acupuncture as a last resort and have had negative experiences of other health-care professionals. Diagnosis was one means to listen to and get to know patients, as it frequently incorporated comprehensive investigation of contributing factors, such as lifestyle and emotional health. Practitioners hoped that by establishing a rapport patients would be confident and trust them and would tolerate the time it can take for acupuncture to work: ‘without rapport, the patient isn't likely to continue a long enough course of treatment’ (Barbara, P). Some practitioners in the private sector implied that spending time with patients was important for building a rapport: ‘we have plenty of time, GP maybe 5 minutes, we talking customer 15 minutes, we treat customer first treatment maybe 45 minutes, one hour’ (Mei, P). However, several NHS practitioners did find time to develop a rapport and explore patients’ experiences more holistically: ‘I spend a lot of time talking about their lifestyle, their mood, their thoughts, their feelings’ (Annie, B). Time constraints were associated with subtle differences in the therapeutic relationship across sectors and are discussed below (‘opportunities for autonomous practice’).

Differences between NHS and private practice

Participants talked about how the availability of acupuncture differs considerably between sectors. In the NHS, policies were imposed by Trusts in the form of guidelines, which limited the type of conditions to be treated with acupuncture (almost exclusively pain), duration of each treatment (typically 20 min per session), frequency of sessions (typically once per week), and overall course duration (typically six sessions, although one Trust was described as not limiting duration in this way). More drastically, the availability of acupuncture on any basis was also limited, in that some NHS Trusts had withdrawn all funding for acupuncture: ‘Very sadly it was withdrawn, it was a financial decision, several years ago. I can only do it privately because I work in a trust that won't finance it.’ (Florence, B). In the private sector, the access to acupuncture was limited by the patient's ability or willingness to pay and this was thought to make some patients expect quick positive results: ‘[some patients are] not very patient about how many treatments they are prepared to pay for’ (Barbara, P). Some practitioners thought that paying for treatments had positive effects, encouraging patients to value their care and to co-operate with lifestyle advice. However, negative consequences were also acknowledged and some cross-sector practitioners valued the limits imposed by the NHS, as they provided certainty for both patients and practitioners: ‘[in the NHS] I don't have to worry about whether they can afford it or not […] [In the private sector] you don't have the luxury of the patient having a six week course’ (Annie, B). Interestingly, some cross-sector practitioners talked about working with the different constraints imposed on availability in each sector to try to maximise benefit for their patients. Florence talked about how providing some acupuncture in the NHS at least allowed patients to try it before committing to paying for it in the private sector. Christine talked about working in a different way to maximise the number of patients she could treat within each session available to her in the NHS.

[My NHS practice is like] a hamster wheel, where you get them in, you get them set up, the next one arrives, you get them in you get them set up. You let the other one free, they clear the room, you bring the next one in. (Christine, B)

Differences in availability were closely linked to differences in opportunities for autonomous practice, which could translate into differences in the co-treatments delivered, as well as more subtle differences in the therapeutic relationship and the perceived effectiveness of acupuncture. These differences were seen as a consequence of the constraints imposed by the NHS that were not present in private practice. Practitioners in both the sectors had some autonomy to incorporate other therapies alongside acupuncture: ‘I call it [acupuncture] a tool in my toolbox’ (Harriet, B). However, choice of additional therapies varied across sectors and was related to time available and whether therapies were sanctioned (or not) within the NHS. In private practice, practitioners typically used herbs, aromatherapy, reflexology, nutritional advice, and homeopathy. In the NHS, practitioners tended to apply more mainstream approaches and concentrate on physiotherapy and hydrotherapy. More subtly, NHS constraints on treatment duration and frequency meant that acupuncturists in the NHS were less able to make collaborative and individualised decisions with patients about a course of treatment. Restricting treatment to painful conditions made it difficult to practise holistically and to treat co-morbid conditions, as well as pain. Some practitioners felt that NHS constraints limited the effectiveness of acupuncture as short session times were thought to inhibit the ability to develop patient rapport. This problem could be lessened if patients had more than one painful condition, which provided a rationale for acupuncturists in the NHS to deliver twice as many treatments: ‘and often, funnily enough, that's what makes the difference because they have that prolonged amount of treatment’ (Pauline, N).

Concerns over qualifications, training, and lack of industry regulation were expressed in both the sectors, but for different reasons. Private practitioners had concerns that the relatively short duration of training often undertaken by biomedical clinicians practising Western acupuncture was insufficient for a profound understanding of the technique, whereas NHS practitioners were concerned over the high degree of variability in private sector clinics located in high-street shops, and their tendency to charge for several sessions upfront. One practitioner argued that some such outlets gave the whole acupuncture industry a bad name: ‘the whole acupuncture profession is tainted’ (Harriet, B). Practitioners in both the sectors referred to the need for industry-wide standards, regulation, and recognised qualifications and codes of conduct.

Practitioners’ explanatory theories of acupuncture, health, and illness influence their practice. As would be expected, there were systematic differences between the practices of acupuncturists trained in the Chinese tradition and those trained in Western acupuncture (Table 4). Practitioners’ explanatory theories stemmed from their training, which, in turn, derived frequently from career orientation. NHS practitioners could access certain acupuncture courses by virtue of their existing biomedical qualifications. They often choose to train in acupuncture to expand their skills, to have a ‘strong armoury in the kitbag’ (Steph, N). Practitioners working in the NHS tend to have very Western-focussed training to which some practitioners add a small degree of Chinese influence. The NHS practitioners who were also physiotherapists used acupuncture as an adjunct to physiotherapy. Fewer private practitioners in our sample had biomedical qualifications and instead tended to have a traditional Chinese training, either traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) or Five-Element acupuncture or a combination. Most saw acupuncture as central to their practice, having chosen to become acupuncturists because of a perceived fit with their desired way of life: ‘I wanted to work with the whole person. Five-Element acupuncture is a way of looking at people as though they were a microcosm of the planet’ (Gemma, P). Private sector practitioners (and some NHS practitioners who were not physiotherapists) offered acupuncture as a primary treatment and saw other therapies as adjunctive.

Table 4 Summary of practitioners’ accounts of Western medical and Chinese approaches to acupuncture

Discussion

We have identified both similarities and differences between NHS and private practice delivery of acupuncture. The most striking similarity was the consistency of perceived effectiveness across sectors, although there was also consensus with regard to the safety of acupuncture and consensus around the perception that, if practising in another sector, an individual practitioner's techniques would be the same. Statutory industry-wide regulation of acupuncturists would be welcomed by acupuncturists in both the sectors for slightly different reasons. Our study also provides evidence from practitioners’ perspectives that there are differences in the acupuncture that patients receive in the NHS and private sector, which confirms and helps to explain findings from studies based on patients’ experiences (Paterson and Britten, Reference Paterson and Britten2008). The major differences, in availability and opportunities for autonomous practice in the NHS and private practice, were seen to stem from the time-related and management constraints imposed on acupuncturists by many NHS Trusts. Some of these differences, for example, in the number and frequency of sessions, in the type of co-treatments, and in the consultation style, might also translate into important differences in patients’ clinical outcomes. These hypotheses receive some support from existing literature (Ezzo et al., Reference Ezzo, Berman, Hadhazy, Jadad, Lao and Singh2000; Di Blasi et al., Reference Di Blasi, Harkness, Ernst, Georgiou and Kleijnen2001; Price et al., Reference Price, Mercer and MacPherson2006; Yuan et al., Reference Yuan, Purepong, Hunter, Kerr, Park, Bradbury and McDonough2009) but need more rigorous testing in future acupuncture studies. Practitioners also felt that acupuncture practice is strongly determined by training in Western or Chinese approaches and their different explanatory models (similar to UK acupuncturists treating Rheumatoid Arthritis; Hughes et al., Reference Hughes, Goldbart, Fairhurst and Knowles2007), and this was confounded with sector in that private practice was dominated by practitioners trained in a Chinese tradition (mainly TCM or Five Elements; Bennetts, Reference Bennetts2007), whereas NHS practitioners were more likely to focus on Western techniques. We have recently conducted a survey confirming that UK acupuncturists trained in Western medical acupuncture are very likely to be working in the NHS, whereas those trained in Chinese approaches are very likely to be working in the private sector (Bishop et al., Reference Bishop, Zaman and Lewith2011). Historically, this makes sense as Western medical acupuncture was developed by clinicians already trained in conventional biomedicine for use as part of their existing clinical practices (White and the editorial board of Acupuncture in Medicine, Reference White2009). Evidence from Germany suggests that an acupuncturist's training and speciality may not affect hard patient outcomes (Witt et al., Reference Witt, Lndtke, Wegscheider and Willich2010), but further work is needed to explore possible effects on the processes and context of care and softer outcomes such as empowerment and satisfaction.

The credibility of our findings is strengthened by the way in which we followed explicit guidelines for thematic analysis and have described our approach transparently in this article. Although we did not recruit a representative sample of acupuncturists, this is consistent with our qualitative approach. Indeed, our sample consisted of those participants who were well placed to inform our research question and included a range of practitioners from different NHS settings (physiotherapy departments, pain clinics, primary care) and different private practice settings (complementary therapy clinics, health and beauty spas, home-based practice). By working iteratively (commencing analysis while interviews were still being conducted) it was possible to highlight areas of interest within early interviews and investigate them more thoroughly in subsequent interviews, which led to the identification of more detailed categories. We would have liked to interview more practitioners working only in the NHS, but unfortunately we were unable to identify many such practitioners within the short time frame of this project. It is therefore possible that had we been able to expand our sample we would have identified additional themes. The entire research team was involved in checking emerging interpretations, which helped to ensure that idiosyncratic interpretations were challenged and modified and that the final report was consistent with the original data. The interviewer's identity as a medical student was known to all the interviewees, and may have resulted in them using more technical language and/or taking an educative stance that would have been less likely with a different interviewer. However, we feel that this dynamic is unlikely to have altered the fundamental substance of the interviewees’ accounts. Acupuncturists perceived few differences in acupuncture delivery across the two sectors, and yet we identified some potentially important differences from their more detailed descriptions. This suggests that future work comparing health-care delivery across different sectors would benefit from an ethnographic approach using observations, as well as interviews.

The differences that we identified between NHS and private practice delivery of acupuncture have implications for the provision of NHS acupuncture and for our application of research findings generated in the private sector. The NHS provision of CAM is not straightforward. Ernst (Reference Ernst2010) found inconsistencies in the rigour with which CAMs are evaluated across NICE guidelines and argued that these therapies should be assessed in the same way as conventional therapies so as to prevent double standards. Franck et al. (Reference Franck, Chantler and Dixon2007) argued that ‘failure [by NICE] to evaluate complementary therapies leads to health inequalities because of uneven access and missed opportunities’ (p. 506). This national inconsistency may be compounded by local NHS management decisions. Our analysis of practitioners’ perspectives adds that even after positive evaluation by NICE, differences and missed opportunities can continue, probably because of the constraints placed on CAM delivery in the NHS and the ways in which this differs between Trusts. The major UK acupuncture study that provided some of the impetus for increasing provision on the NHS was delivered in private sector clinics (Thomas et al., Reference Thomas, MacPherson, Thorpe, Brazier, Fitter, Campbell, Roman, Walters and Nicholl2006). Our analysis suggests that the acupuncture that is currently being delivered in the NHS may differ from that typically delivered in the private sector. Allowing practitioners to develop individualised treatment plans with patients (in relation to treatment frequency and duration) could bring NHS practice closer to what is seen and has been researched in the private sector. Encouraging and enabling more acupuncturists who are trained in Chinese approaches to work in the NHS could also decrease the differences between NHS and private practice acupuncture. Future studies should explore the impact on patients’ clinical outcomes of the different ways and environments in which acupuncture is delivered.

Acknowledgements

We thank all our participants for volunteering to share their experiences with us. The interviews conducted for this project were undertaken by N.A. as part of her University of Southampton Medical Degree and as such expenses (such as travel, transcription) were funded by the Department of Primary Medical Care, University of Southampton School of Medicine. F.L.B. is funded as an Arthritis Research UK Career Development Fellow (Grant 18099). G.T.L.'s post is supported by a grant from the Rufford Maurice Laing Foundation.