Introduction

Internationally, it is recognised that adapting to life in a care home environment can be an emotional, complex and upsetting occasion for older people as well as their families (Ellis, Reference Ellis2010; Brandburg et al., Reference Brandburg, Symes, Mastel-Smith, Hersch and Walsh2013; Sury et al., Reference Sury, Burns and Brodaty2013; Ryan and McKenna, Reference Ryan and McKenna2015;). There is a paucity of research that considers the experiences of individuals in the initial weeks after entry to a care home.

Numerous factors can influence the adaption and adjustment process for older people when relocating to a care home (Bradshaw et al., Reference Bradshaw, Playford and Riazi2012; Brownie et al., Reference Brownie, Horstmanshof and Garbutt2014; Križaj et al., Reference Križaj, Warren and Slade2018; Moore and Ryan, Reference Moore and Ryan2017). Some research studies have identified that older people may experience a loss of autonomy, independence and identity, making adaptation to life in a care more challenging. Moreover, older people often struggle to adhere to the routine and rules of the care home environment (Cooney, Reference Cooney2012; Bradshaw et al., Reference Bradshaw, Playford and Riazi2012; Brandburg et al., Reference Brandburg, Symes, Mastel-Smith, Hersch and Walsh2013; Rieldl et al., Reference Riedl, Mantovan and Them2013; Ericson-Lidman et al., Reference Ericson-Lidman, Larsson and Norberg2014). Several research studies convey that care home environments can be restrictive with a lack of privacy, have limited opportunity for social interaction and have regimented practices (Tsai and Tsai Reference Tsai and Tsai2008; Bradshaw et al., Reference Bradshaw, Playford and Riazi2012; Cooney Reference Cooney2012; Križaj et al., Reference Križaj, Warren and Slade2018). Maintaining continuity between the older person's past and present role has been identified as an important factor in the adaptation process after entry to a care home (Bradshaw et al., Reference Bradshaw, Playford and Riazi2012; Minhat et al., Reference Minhat, Rahmah and Khadijah2013; Brownie et al., Reference Brownie, Horstmanshof and Garbutt2014; Križaj et al., Reference Križaj, Warren and Slade2018). There is also evidence to suggest that individuals may experience a greater sense of freedom, be able to regain some of their independence and feel less of a burden to others (Bradshaw et al., Reference Bradshaw, Playford and Riazi2012; Sullivan and Willis, Reference Sullivan and Willis2018). Furthermore, research from older people's perspectives suggests that when faced with upsetting situations, older people attempt to preserve goals, values and relationships, and adapt by using cognitive coping mechanisms, as well as employing practical strategies including maintaining social roles and activities, and receiving support from close ongoing relationships (Tanner, Reference Tanner2010; Clarke and Bennett, Reference Clarke and Bennett2013).

The transition to a care home environment therefore represents a uniquely significant experience for older people. Brandburg (Reference Brandburg2007) described three identifiable processes associated with the transition to life in a care home: (a) the ‘initial reaction’ or emotional response to the move which is not dependent on whether the admission is planned or unplanned; (b) ‘transitional influences’ such as life experience and the meaning attached to the relocation; and (c) ‘adjustment’, where the individual comes to terms with moving, The second and third stages, transitional influences and adjustment, interact and interplay during the process of transition. As a result, older adults are in a dynamic process of adjusting and readjusting as they interact with various transitional influences such as the formation of new relationships with residents and staff. The end of adjustment occurs when the resident comes to terms with living in a care home, has developed new relationships, maintained old friendships and reflected on their new home environment. According to Brandburg (Reference Brandburg2007), the final ‘acceptance’ phase usually occurs between six and 12 months post-admission. This marks the end of the transition period when new residents finally accept living in the nursing home. Contrastingly, Bridges (Reference Bridges2004) defined transition as a psychological reorientation with three distinct phases: (a) endings that involve letting go and experiencing loss in some form; (b) a neutral zone that is an in-between phase, usually associated with uncertainty; and (c) the new beginning that may involve a new focus or new identity. Furthermore, the ‘transition’ process has been defined as occurring as a result of change in a person's life continuing until adaptation occurs, producing fundamental changes to an individual's role or identity (Porter and Ganong, Reference Porter and Ganong2005; Wiersma and Dupuis, Reference Wiersma and Dupuis2010; Paddock et al., Reference Paddock, Brown Wilson, Walshe and Todd2019).

Brownie et al. (Reference Brownie, Horstmanshof and Garbutt2014) undertook a systematic literature review to identify the factors that impact on residents’ transition and psychological adaptation to long-term care facilities. The review was informed by the concept of home, and Bridges’ (Reference Bridges2004) three stages of transition framework. Bridges’ framework provided conceptual models for better understanding of the needs and aspirations of older people who are in the process of this late-life transition. They identified 19 observational, descriptive and cross-sectional studies exploring older peoples’ views about their experiences relocating and adjusting to life in a care home. The majority of studies were undertaken within the first two weeks after entry to the home (Iwasiw et al., Reference Iwasiw, Goldenberg, Macmaster, McCutcheon and Bol1996; Wilson, Reference Wilson1997; Lee, Reference Lee1999, Reference Lee2001, Reference Lee2010; Heliker and Scholler-Jaquish, Reference Heliker and Scholler-Jaquish2006; Keister, Reference Keister2006; Komatsu et al., Reference Komatsu, Hamahata and Magilvy2007; Walker et al., Reference Walker, Curry and Hogstel2007; Saunders and Heliker, Reference Saunders and Heliker2008; Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Popejoy and Radina2010; Walker and McNamara, Reference Walker and McNamara2013). Two studies were undertaken within the one- to two-month period post-placement (Wilson, Reference Wilson1997; Komatsu et al., Reference Komatsu, Hamahata and Magilvy2007) and another study collected data at monthly intervals up to six months after placement (Saunders and Heliker, Reference Saunders and Heliker2008). Positive adaptation was reported to be influenced by older people being able to retain personal possessions, continue valued social relationships and establish new relationships within the care facility. A qualitative metasynthesis undertaken by Sullivan and Williams (Reference Sullivan and Williams2017) reviewed eight studies of older adults’ transition experiences to long-term care facilities, guided by Meleis's (Reference Meleis2010) Theory of Transition. Three themes were identified: loss requiring mourning, stability sought by gaining autonomy and acceptance when inner balance is achieved. A more recent systematic review undertaken by Fitzpatrick and Tzouvara (Reference Fitzpatrick and Tzouvara2019) sought to understand what factors facilitate and inhibit the transition for older people who have relocated to a long-term care facility informed by Meleis's Theory of Transition. Data synthesis of 34 studies using a variety of terms, timelines and study designs identified that transition featured potential personal and community-focused facilitators and inhibitors which were mapped to four themes: resilience of the older person, interpersonal connections and relationships, this is my new home and the care facility as an organisation.

Adaptation to care home life is a process that occurs over a period. Part of understanding this process requires recognition of variances in the responses of older adults. Care home residents are often marginalised and excluded from research (Backhouse et al., Reference Backhouse, Kenkmann, Lane, Penhale, Poland and Killett2016). Moreover, there is a paucity of research that takes into consideration the relocation process, incorporating residents’ experiences with the move (Sussman and Dupuis, Reference Sussman and Dupuis2012).

This paper is part of an overarching research study which aims to increase our understanding of how older adults make the transition from living at home to a care home over the course of 12 months, at four discrete time-points: prior to or within three days of admission and at three time-points after the move (four to six weeks, four to five months and 12 months). The findings from the first time-point indicate that older people making the move to a care home are ‘at the mercy’ of families, health and social care practitioners, and care home staff (O'Neill et al., Reference O'Neill, Ryan, Tracey and Laird2020).

The main limitation of the current body of literature is the dearth of studies on the experiences of the older person in the initial weeks following the move to a care home. The purpose of gathering data at this critical time-point is to elucidate the ways in which older people cope with the many changes associated with the move to a care home, e.g. leaving home and being separated from family, friends and communities. This initial post-placement time period often follows a time of crisis, an acute illness or a period of hospitalisation (Wilson, Reference Wilson1997; O'Neill et al., Reference O'Neill, Ryan, Tracey and Laird2020). The way in which individuals are supported (or not) during this time period may have a bearing on their adaptation to life in the care home further down the line. This paper therefore focuses on the four- to six-week period after the move. The knowledge gained from this study has the potential to inform care delivery and policy in determining the initial and ongoing support needs of individuals during this critical time period.

Care home

In this research study, the term ‘care home’ is used to encompass both residential and nursing homes. A residential care home provides residential accommodation with both board and personal care for persons by reason of old age and infirmity, disablement, past or present dependence on alcohol or drugs, or past or present mental disorder. They do not provide nursing care. A nursing home is any premises used or intended to be used for the reception of and the provision of nursing for persons suffering from any illness or infirmity. Some homes are registered to care for both people in need of residential and nursing care (Regulation and Quality Improvement Authority, 2020).

Methodology

Aim

Consistent with grounded theory methodology, the researcher did not identify specific objectives for the study but rather began data collection with a broad aim. To this end, the overall aim of this study was to explore individuals’ experiences of moving into a care home with a specific focus on the four to six weeks post-placement period of adjustment.

Study design

A grounded theory approach, consistent with the work of Strauss and Corbin (Reference Strauss and Corbin1990, Reference Strauss and Corbin1998), was chosen as it facilitated the development of a new perspective on the experiences of older people in the early weeks after moving to a care home. Grounded theory is recommended when investigating social problems or situations to which people must adapt (Corbin and Strauss, Reference Corbin and Strauss2008; Morse et al., Reference Morse, Stern, Corbin, Bowers, Charmaz and Clarke2009; Maz, Reference Maz2013). Grounded theory is an ideal methodology to understand actions and processes through transitions (Morse, Reference Morse2009), and has been used by qualitative researchers to study processes engaged in by service users (Grant et al., Reference Grant, Brutscher, Kirk, Butler and Wooding2009) and family care-givers (Bull and McShane, Reference Bull and McShane2008; Holtslander and Duggleby, Reference Holtslander and Duggleby2009; Munhall, Reference Munhall2012). A semi-structured interview schedule was designed to stimulate discussion of individuals’ perceptions, thoughts and feelings about their early experiences of living a care home.

Participants and recruitment

Purposive sampling was used in the initial stages of recruitment and data collection. Thereafter, and consistent with grounded theory methodology, theoretical sampling was employed to recruit a sample of 17 individuals identified by care managers within older peoples’ community teams and by waiting lists held by care home managers within a large Health and Social Care Trust in the United Kingdom. The Trust provides health and social care services to a population of approximately 300,000 people. All nursing (N = 21) and residential homes (N = 4) caring for older people within the study site were registered with the regulatory body and the sample was drawn from this list. The care homes (N = 8) selected were located within both rural and urban areas. Community care managers and care home managers had identified potential individuals who met the study's inclusion criteria in that participants were aware that the move was permanent and they achieved a score of 24 or above on the Mini-Mental State Examination (Folstein et al., Reference Folstein, Folstein and Mchugh1975). The researcher (MON) obtained written consent and individual face-to-face interviews were arranged at a time and place convenient for each participant. Only one older person invited to do so refused to participate in the study.

Ethics

Ethical approval for the study was obtained through the Ethics Filter Committee of Ulster University, the Office for Research Ethics Committees Northern Ireland, and the Clinical and Social Care Governance Committee of the Health Care Trust. The Code of Ethics of the International Council of Nurses (2006) has underpinned all aspects of ethical considerations for this study which relate to the protection of vulnerable adults, participants’ information, consent, autonomy and confidentiality. A distress protocol was developed, and a system of referral and escalation put into place taking due cognisance of the Protection of Vulnerable Adults guidelines (Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety, 2006), for implementation should any participant become distressed during interview. The interviews were conducted by the first author who is an experienced mental health nurse and can identify early signs of distress. In addition, participants were asked if there was someone she or he would like to have present during the interview, or who could be a contact person in a case of distress. In the event, no participant became distressed. Some gave emotional responses during the interviews. In adherence to the protocol, the interviewer and participant talked about this, and in each case, the participant wanted the interview to proceed, and indeed felt that talking about their experiences was supportive. The care home manager was informed after the interview if the participant had become upset during the interview. The interviewer did not leave the participant until he or she was content. Informed consent was provided by each participant who agreed to take part in the study with an additional clause giving consent to use a digital recorder for the interviews. Assurances of confidentiality and anonymity were provided and supported by the allocation of pseudonyms in the presentation of the study and its findings.

Data collection

Individual face-to-face interviews were arranged at a time convenient for each participant. All interviews were conducted between May 2017 and October 2018. Semi-structured interviews were used to generate discussion that would illuminate ongoing experiences and perspectives from 17 individuals who had moved into a care home. The individual interviews were conducted in private rooms in the eight different care homes. The audio-taped interviews were transcribed verbatim with each interview lasting approximately 60 minutes. Consistent with a grounded theory approach, the semi-structured interviews provided both focus and flexibility (Corbin and Strauss, Reference Corbin and Strauss2008). Simultaneous data collection and constant comparative analysis were repeated until data saturation was accomplished along with the advancement of theoretical concepts and the development of a core category. As data collection proceeded and the basis of a theory began to emerge, it became necessary to theoretically sample older people in residential and rural care homes as interim findings indicated something diverse about the experiences of older people in care homes within the urban environment. Strauss and Corbin (Reference Strauss and Corbin1998: 201) have described theoretical sampling as a means to ‘maximise opportunities to discover variations among concepts and to densify categories in terms of their properties and dimensions’. Therefore, potential participants moving to these types of care homes were invited to take part in the study. The process of theoretical sampling continued until the emerging concepts and categories reached saturation.

The interview schedule evolved commensurate with category and sub-category dimensions using the grounded theory approach. Prompts were used to generate discussion and included:

• Tell me about how you are getting on since you moved into the care home?

• Tell me about how you keep in contact with your family and friends at home?

• How has your life changed since living in this care home?

• Can you tell me about any concerns and/or worries you may have about living here now?

• Prompts on physical, psychological and social wellbeing since admission.

Data analysis

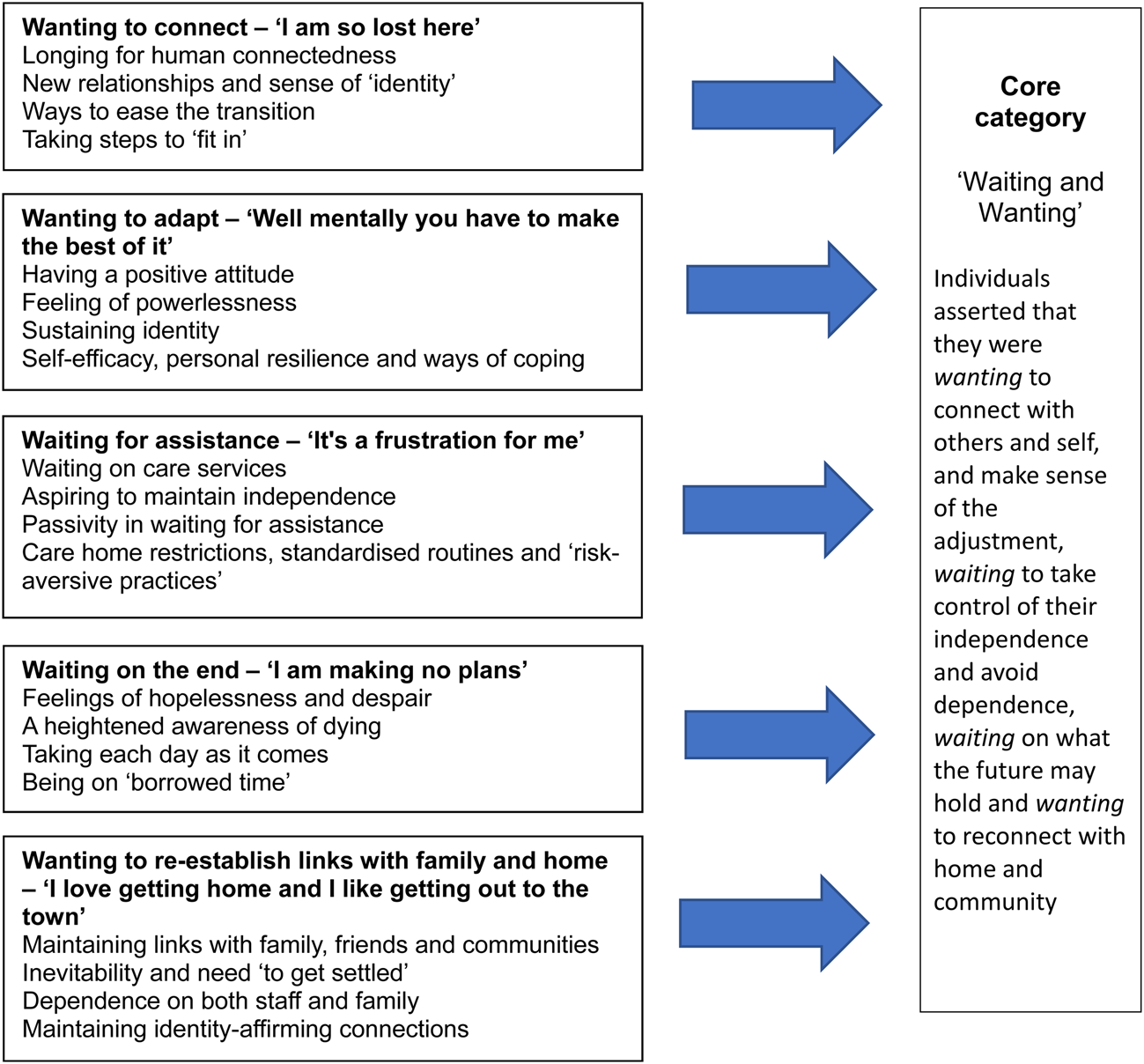

The interviews were recorded and checked to ensure the rigour of the data collection procedures. NVivo 12 qualitative data analysis program software (QSR International, 2018) facilitated the organisation, management and retrieval of transcribed interviews and field notes, and provided tools for coding, categorising and linking qualitative data. Constant comparative analysis underpinned data analysis and data management techniques. Repeated ideas, concepts or elements became apparent, and were tagged with codes extracted from the data. Grouping of codes into concepts and then into categories was undertaken after more data collection and review. As analysis progressed, coding moved towards being ‘selective’, focusing on those codes which related to emergent main categories. In the final stage of coding, the process of identifying and choosing the core category occurred by systematically connecting it to other categories and validating those similarities and relationships (Strauss and Corbin, Reference Strauss and Corbin1998). The concept of ‘Waiting and Wanting’ ‘emerged from the final analysis (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Diagram illustrating relationship of major categories to each other and to the core category.

Ensuring rigour

Numerous strategies were employed to ensure the rigour of the study. The study was conducted with an awareness and application of the underlying principles of the authenticity criteria developed by Nolan et al. (Reference Nolan, Hanson, Magnusson and Anderson2003) and further developed in care homes research by Wilson and Clissett (Reference Wilson and Clissett2011). In the grounded theory approach, validity depends on theoretical sensitivity, which refers to the ability to give meaning to data and the capacity to understand the sources of theoretical sensitivity (Strauss and Corbin, Reference Strauss and Corbin1990, Reference Strauss and Corbin1998). The initial interviews were recorded and checked to ensure the rigour of the data collection procedures. The constant comparative analysis of emerging data facilitated the verification of findings and minimised the likelihood of personal bias. The process of theoretical sampling continued until the emerging concepts and categories reached saturation. During the open and axial coding stages, two members of the research team (MON and AT) independently viewed the original uncoded manuscripts and confirmed themes, thus ensuring that interpretations represented the experiences of the individuals. After the selective coding process, trustworthiness of the data was enhanced by all the research team who reviewed themes and discussed alternative interpretations of the data to maximise credibility, dependability and confirmability (Lincoln and Guba, Reference Lincoln and Guba1985). In keeping with one of the tenets of grounded theory (Corbin and Strauss, Reference Corbin and Strauss2008), individuals’ own language at all levels of coding was used to further ground theory construction and add to the credibility of findings.

Findings

Profile of individuals

The 17 individuals who participated in this study comprised ten women and seven men with an average age of 83.3 years. Seven of the individuals were transferred from hospital to the care home and the others were relocated directly from their home. The majority of the individuals (N = 13) were living alone at the time of admission while the minority (N = 4) lived with spouse/family members.

The main reasons cited for prompting the relocation to a care home was deterioration in physical health (N = 11), recent bereavement (N = 3) and no-one to take care of me/changing family circumstances (N = 3). Only four of the 17 participants stated that they had made the decision to move to a care home, and of these four, only two were able to move to the care home of their choice. Demographic details of individuals and reason for admission are outlined in Table 1.

Table 1. Characteristics of the interviewees and details of admission

Note: GP: general practitioner.

From concepts to categories

This paper reports key findings pertaining to the experiences of 17 older people within the four- to six-week post-placement period in a care home. Data analysis revealed the following five distinct categories: (a) wanting to connect – ‘I am so lost here’, (b) wanting to adapt – ‘Well mentally you have to make the best of it’, (c) waiting for assistance – ‘it's a frustration for me’, (d) ‘waiting on the end’ – I am making no plans’ and (e) wanting to re-establish links with family and home – ‘I love getting home and I like getting out to the town’. Together these five categories formed the basis of the core category ‘Waiting and Wanting’ which encapsulates the overall experiences of adjusting to life in a care home, for the men and women in this study. Individuals asserted that they were wanting to connect with others and self, and make sense of the adjustment, waiting to take control of their independence and avoid dependence, waiting on what the future may hold and wanting to reconnect with home and community. Figure 1 shows the relationship of major categories to each other and to the core category.

Wanting to connect – ‘I am so lost here’

Undeniably moving to a care home where the future might appear uncertain is regarded as one of the most daunting and difficult challenges an individual can face in their later life. Some individuals were experiencing a longing for human connectedness in their new environment:

I have been doing nothing here, I just sit here and wait for people to come and visit me. (Mona)

Others felt out of place, citing other resident's cognitive impairment and frailty as a fundamental obstacle to social engagement:

I am so lost here, it's not me, it's not home and it's so big, I don't really know where I am at now. It is very hard to find your way. Some of them, but not all of them are beyond making friends, they are not sick, they're old, so they're not good anymore, you have to take your pick. (Ellen)

For some individuals the importance of forming new relationships was seen as being crucial to one's sense of ‘identity’ and ‘connectedness’ to people within their new home:

I am just friendly with everyone. I like being friends with people and that is very important to me as I am coming in here as an outsider. (Tracey)

I know I didn't expect to settle quickly, but it's taking a bit longer than I thought it would. I was a bit disappointed when I came because I didn't know any people and I thought that I would. But I've got to know some people now, but I still want to go home. (David)

It was apparent that for some individuals their ‘sense of self’ was enhanced or reduced through their interaction with and observations of other residents and their reactions to others’ behaviour:

It's not home. Everybody says the same, it's great and all that but it's not your own. There's an old lady I met since I came in, she likes me and every morning I must get up and wave to her in the dining room. I suppose when you look at it there are people far worse off than me. Some of them can't even hold the cup up in their hands. (Bernadette)

I'm not really settled here. You see there is no-one here that I could honestly feel that I could be friends with … so that's it. (Charles)

It was evident that care home staff were primarily perceived as providers of health care delivery only and not as people with whom to develop relationships:

Well they only come in to do tasks and go out again. You don't develop a relationship with them. (Sean)

Some individuals wanted to ‘ease the transition’ to living in the care home by spending parts of the day outside the home with family:

I suppose I will have to get settled here I have no choice. My sister comes and takes me out for a while every day so thank god for that. I have to get out of here even just for a while. I know that I have to get used to it in here, but it would be too long for me if I had to spend the whole day in here every day. (Molly)

It is evident that maintaining one's identity and autonomy are considered significant factors in an older person's experience of moving into a care home. Some participants were taking steps to ‘fit in’ and ‘feel their way’ within this new environment:

I suppose you just have to get on with people, well if you don't it is bad, but thank god I do. I don't go down and sit all day in the big room looking at TV. That's not my thing. And maybe they think I should, but I go down every so often so that they don't think that I'm not mixing. But when I go down there's only two or three of them there sound asleep, so I come back up again. And the others must do the same. (Anne)

Wanting to adapt – ‘Well mentally you have to make the best of it’

Having a positive attitude towards care home admission can be supported by hospital staff who discussed with one participant, Gerard, the necessity for the move. They provided him with information about the home and discussed the practicalities of the move, thus making it easier for him to become accustomed to a new way of living in the future:

Oh, I love it here I really do. I was told by the staff in the hospital that when you go over to [care home] you will love it. They are a sort of family here you know. Everybody speaks to each other and they are all good to each other. I do tell them that too you know. (Gerard)

There was a sense of individuals making the new home meaningful by bringing in possessions and photographs to symbolise their identity. Continued identification with such meaningful symbols helped to sustain identity:

I suppose I am starting to get used to it now a bit. I am trying anyhow. It is very different you know from being at home with your own people. I have brought some photos here now as well and my bed throws, I like them. I would have liked to bring more but you really don't have much room you know. (Isobel)

Individuals expressed their own sense of self-efficacy, personal resilience and ways of coping with adjusting to life in the care home, by taking ‘one day at a time’ and mentally ‘making the best of it’:

Well I always take it one day at a time and thank god it's been good so far. It's the best way to take it, you know, because I wouldn't be doing as well as I'm doing otherwise, you see, I would miss things from home. Well I do a lot of thinking but sure that's no harm. (Anne)

You have to try and accept being here you know but it is very hard, really hard … it's psychological, but you feel like you are at the end of the road, you know. Well mentally you have to make the best of it that's the main thing. Firstly, settle into the illness, clear your head and your mind and you will get by, otherwise, you would just be depressed. (Andrew)

A strong part of facing reality for some individuals involved resisting having decisions taken away from them, proposing to fight for their independence and sense of identity:

My life has to change. I cannot leave everything to the doctors. I have to get myself better then I will think differently. I am not thinking properly now, I'm not right yet, I feel scared of everything. I'm not there yet, I have to say to myself that I can still have a life. (Ellen)

Some Individuals were moving towards acceptance of being in a care home, often accompanied by tears as the reality dawned on them that they would not be returning to their home:

Well, you know, I hope I will settle. Some nights I would sit down and have a wee cry to myself. I know now that I have to stay in here because I can't stay on my own. I'm reconciled to that now … I have to be. (Bernadette)

Others were putting on a brave face for the care home staff and their family:

It's easier to smile than cry. You've a lot to answer for after you've cried, you know, was that necessary … well I have to put on a brave face for my wife and the people here. You see my wife she has been through so much in the past year and she has never failed me. I would fail her if I broke down … and the staff well you see they expect you just to get on with it, pull yourself together like. (Sean)

Other individuals were self-assured in the decision they had made to move to a care home. Reflecting on the positive elements of the relocation, opportunities were identified to form new relationships, gain staff support with aspects of care, and pursue former hobbies and activities:

Life is sort of different now. I am content now; I will not be going anywhere else … They let you do what you want and don't force you to do anything, I like that … you see that's me … Moving here is the right decision for me. I know now that I had to leave the house. At the end of the day it is only bricks and mortar. (Gerard)

Yeah, it's good to get someone to do something for you. It takes the pressure off me. I feel safe here. I like going out for a walk … you know I am just happy with the little things. (Tracey)

However, some individuals considered their self-determination at risk because they felt restricted by care home routines and practices which was experienced as a feeling of powerlessness:

I do think that there are too many rules when you are living here. It is a big change for me to live away from my home and my life. I am not sure if it is a good change … I suppose time will tell. (Andrew)

Waiting for assistance – ‘It's a frustration for me’

Individuals talked about how having to wait on care services had a negative effect on their individuality and independence, and curtailed them from making the progress they would have liked:

The stroke nurse who was to do the swallowing test never came. She was to sign me off for swallowing so that I could eat bread … You see I am very determined to be as independent as I can be? I would love to be able to walk to the toilet on my own. I would just like more progress. Every time I get a chance to walk and work at my arm, I take it, I do all the physio exercises that I am told. (Therese)

I am lost without my glasses because reading is very important to me so without them … well what else can you do? I read all my life and I miss that. I hope that they get here soon. The fella tested my eyes weeks ago, but I haven't heard a word about it since. I'm just wondering what's happening and that they have been ordered because I need them. (Tracey)

Aspiring to maintain independent physical function was important to some individuals who were happy with improvements in their health following physiotherapy and self-governed exercise routines, while others were frustrated about losing progress made while in hospital, making them more dependent on staff for assistance:

They got me walking in hospital, but they don't do that here. I have never been up walking and they don't give you physio … and it's awful when they let you go on ringing that bell and just ignore you, and you have been waiting for over an hour and nothing happens. I have had to phone my family to tell them to phone the home and ask them to answer the bell! (Andrew)

I've just been plodding along day to day, it's the same day well every day really, I feel trapped. I have to depend on so many people. Just even to get out of bed. My wife does my physio when she comes in, especially my legs. (Sean)

Care home restrictions, standardised routines and ‘risk-aversive practices’ threatened individuals’ independence and autonomy, and generated frustration and passivity in waiting for assistance:

I like to do as much … well as much as I can for myself. But they don't like it, for me to be independent. The staff will treat you well, but some of them are like the Gestapo … kind of serious, they don't ask you nicely to do something. They sort of demand you do things because we have to sort of answer to their call you know, so you don't want to give them too much reason to be annoyed with you, I don't anyway. (Charles)

It's a frustration for me having to wait on the staff and ringing that bell. Some of the nurses are nice. But if you need help, they aren't in a hurry. I am getting to know who to ask now. (Ellen)

Although I have a Zimmer frame, I still have to have someone to take me to the toilet, I'm not allowed to walk on my own, but I think I'm fit to walk on my own. I feel restricted I think that's my main problem. (David)

Waiting on the end – ‘I am making no plans’

Some individuals expressed feelings of hopelessness and despair about the future, seeing no purpose when their physical, mental and social abilities were diminished:

I am getting to the stage that I don't want to go on. I can't go on like this, I am in a lot of pain. (Mona)

For others these feelings varied; one participant recognised how on admission she wished for death. This was a personal reflection of psychological wellbeing at that time:

I was so down when I first came here. The nurse when she came last week, she said I had changed, that I was getting better … Well less depressed. I know that at first, I was bad, I was trying to write a suicide note, I was scared. (Ellen)

Death was an inevitable part of life for many individuals who often said they were taking each day as it comes and not worrying too much about tomorrow:

I don't know what is going to happen in the future. I always thought that I wouldn't like to die a sudden death. I would like to be ready for death. But other than that, I don't think too far ahead. (Bernadette)

I am making no plans. If I am here tomorrow, then I am here tomorrow and that's it. I have had a good life. Every day I go to bed I say to myself I wonder will you be here in the morning. (Tony)

Accordingly, for some individuals, death and dying framed their present outlook on life. Some spoke about ‘of being on borrowed time’, ‘feeling ready to die’ and some even welcomed it:

I don't see much of a future I don't have anything to look forward to … I look forward to when I would die. I don't think I will last that long; I don't know. Well I have a chest problem and a blood problem. I am happy to go whatever happens. (Charles)

My life is different here. I don't see … well at my age now, I don't see much future except death. I wasn't very well this last while … I was telling them I was going to die. (Jane)

As individuals observed contemporaries’ deaths, a heightened awareness of dying became evident:

The staff here keep it very quiet if someone is ill. I've noticed that when you're waiting for someone to die, there's hints, for example there's the trolley arriving, when you see that you know that someone is seriously ill … But you are disappointed if there's a death here. There was one last week, everyone feels it. There's another lady ill now, it puts us off, and we're not in the same good humour. (David)

For some, experiencing a loss of family created an awareness of their own mortality:

My sister died recently, it was a big loss to me you know but what can you do, if god wants them, he takes them. That's the way … sure, our own day will come. (Isobel)

Wanting to re-establish links with family and home – ‘I love getting home and I like getting out to the town’

Maintaining links with family, friends and communities was important to reinforce a sense of self and to safeguard against a threatened identity or wellbeing:

I have a cousin who comes in … Emily, she comes in. She lives close by, so it is nice to see her. My niece used to come down every day at the beginning, but I hardly see her now. (Mona)

I suppose at my age there isn't much to look forward too, but I look forward to seeing my family coming in. I haven't been out since I came here, it would be nice just to go home for a while to see them and have my dinner. (Isobel)

There was recognition of the inevitability and need ‘to get settled’ in the care home on a gradual basis, while maintaining links with family which was also identified:

I suppose what will help me settle is...well I like to be independent and do my own thing you know...so I hope that I will be able to keep doing that here as I need to keep getting out and about and doing the things that I want. You see I like meeting people, I always have done and going out with my sisters. (Molly)

Individuals experienced a dependence on both staff and family to get out or come into the care home to ‘see family’, ‘see my home’, ‘go to the chapel’, ‘go shopping’ or just ‘be in the garden’:

I haven't been out since I've been here. It's such a bother, I think we will have to wait to the summer to someone brings us out. The staff said it's too cold to go out now … But my niece comes to see me every week and then I have other visitors come too. (Martha)

I would really like to go to the chapel, but I can't go on my own. Well not at present with my foot … but I could go out in a wheelchair if someone would take me. I don't think there is anybody that would do that here. (Isobel)

I haven't been out home since I came here. They probably think that it would upset me too much … I like my family coming to visit. I would like to get outside to be in the fresh air and to get out for a run home to see the house and the neighbours. (Andrew)

Most individuals expressed the view that they wanted to maintain social contacts outside the care home to maintain identity-affirming connections and be part of the community:

I love getting home and I like getting out to the town you know. I just like to see if there is any building going on or what's happening in the town. (Tracey)

A lot of people come at the beginning to see you when you move into the home, but it tails off after that. My nephew took me out to tea that was good. I like getting out, it is a nice change. My other niece will be back to see me this coming week. (Therese)

Discussion

As there is limited research that incorporates residents’ experiences during the initial weeks following entry to a care home (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Woo and Mackenzie2002; Fraher and Coffey, Reference Fraher and Coffey2011; Johnson and Bibbo, Reference Johnson and Bibbo2014; Sussman and Dupuis, Reference Sussman and Dupuis2014), this study set out to explore older peoples’ experiences of the first four to six weeks following the move. Five distinct categories captured the experience of the four- to six-week post-placement period. These were: (a) wanting to connect – ‘I am so lost here’, (b) wanting to adapt – ‘Well mentally you have to make the best of it’, (c) waiting for assistance – ‘it's a frustration for me’, (d) ‘waiting on the end’ – I am making no plans’ and (e) wanting to re-establish links with family and home – ‘I love getting home and I like getting out to the town’. Together these five categories formed the basis of the core category ‘Waiting and Wanting’ which encapsulates the perceived transitional experiences of the men and women in the study. The core category of ‘Waiting and Wanting’ provides descriptions of individuals experiences of ‘wanting’ to reconnect with their family, friends, home and community, and ‘waiting’ to make sense of the process of adaptation, while taking control of their lives and avoiding dependence. The core category connects to emergent categories which encompassed descriptions of individuals’ senses of identity, connectedness with others, autonomy and caring practices.

Within this study the period of adaptation following the move to the care home was viewed by many individuals as leading to a loss of independence, autonomy, decision-making, meaningful engagement and continuity of former roles. Moreover, the loss of an individual's home life presented a major challenge threatening identity, belonging and sense of self (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Simpson and Froggart2013; Brownie et al., Reference Brownie, Horstmanshof and Garbutt2014; Paddock et al., Reference Paddock, Brown Wilson, Walshe and Todd2019), and for many a sense of belonging was taking time to develop (Lindley and Wallace, Reference Lindley and Wallace2015). Individuals were clearly ‘wanting’ to connect with others in this new environment, and at the same time ‘wanting’ to re-establish links with family and home. Numerous studies have found that leaving home and being separated from family and communities compounds these losses and feelings of isolation (Iwasiw et al., Reference Iwasiw, Goldenberg, Macmaster, McCutcheon and Bol1996; Lee, Reference Lee1999; Bland, Reference Bland2005; Heliker and Scholler-Jaquish, Reference Heliker and Scholler-Jaquish2006; Saunders and Heliker, Reference Saunders and Heliker2008; Fraher and Coffey, Reference Fraher and Coffey2011; Hutchinson et al., Reference Hutchinson, Hersch, Davidson, Chu and Mastel-Smith2011). Adapting to a care home's ‘rules and regulations’ and being subjected to ‘waiting’ for assistance were sources of frustration. The need to ‘learn the ropes’ is an additional source of stress and anxiety for some individuals (Wilson, Reference Wilson1997; Lee, Reference Lee2001; Heliker and Scholler-Jaquish, Reference Heliker and Scholler-Jaquish2006).

Many anxieties, including health and social issues, can affect the adaption and adjustment process for older people after moving to a care home (Bradshaw et al., Reference Bradshaw, Playford and Riazi2012; Brownie et al., Reference Brownie, Horstmanshof and Garbutt2014; Križaj et al., Reference Križaj, Warren and Slade2018). Within this study, some individuals experienced emotional responses in their early weeks of living in the care home, reporting ‘It's hard to find your way’, ‘I am so lost here’. These experiences have been previously identified by Bridges (Reference Bridges2004) when considering the early transition stages of moving to a care home, i.e. an ending; and a period of confusion which can lead to high anxiety levels; and a new beginning. Within this study, individuals whose relocation experience was deemed to be positive, expressed hopeful affirmations ‘Life is sort of different now. I am content now’, ‘Oh, I love it here I really do’. It has been recognised within Brandburg's (Reference Brandburg2007) transition process framework how an initial reaction to the move can be marked by emotional responses, and how personal characteristics, values, the history and admission circumstances can influence transitional experiences thereafter. The findings of this study resonate with the first two stages of Brandburg's (Reference Brandburg2007) transition process framework in that the first stage identifies an initial reaction to the move that is marked by emotional responses; and the second stage as transitional influences, e.g. personal characteristics, values, history and circumstances of admission. Within this context, most individuals within this study identified that adapting to life in a care home was an ongoing process that for the main part they were trying to navigate themselves with little support from care home staff or others. This was perceived by individuals as an upsetting and worrying experience during the four- to six-week adaptation phase of settling into life in a care home.

Meleis's theory of transitions explains how a person relates to their environment and health. A change in health and environment can change how a person perceives his or her role. Furthermore, an individual's response to change can be influenced by internal (attitude, knowledge, cultural beliefs) and external factors (social support, socio-economic status) (Meleis, Reference Meleis2010). Within this study, some individuals spoke about their frustration of ‘waiting for assistance’ from care staff to attend to personal needs and the importance of maintaining their own independence and ‘identity’. They expressed annoyance and resentment that staff were preventing them from doing the things they wanted to do or were taking their independence away by doing things for them that they were able to manage themselves. Such staff behaviour was construed as restrictive and limiting autonomy. These experiences are also echoed in the findings of Paddock et al. (Reference Paddock, Brown Wilson, Walshe and Todd2019), who suggested that institutional restrictions, standardised routines and strict risk management policies can threaten individuals’ independence and autonomy. It has been recognised that when independence is removed from a person's life, an individual can feel defeated, depressed or begin to doubt their own ability to care for themselves (Wiersma and Dupuis, Reference Wiersma and Dupuis2010; Custers et al., Reference Custers, Westerhof, Kuin, Gerritsen and Riksen-Walraven2012). Moreover, low expectations can lead to reduced capabilities and can be self-fulfilling, causing deterioration in health and cognitive ability (Chin and Quine, Reference Chin and Quine2012; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Simpson and Froggart2013; Zamanzadeh et al., Reference Zamanzadeh, Rahmani, Pakpour, Chenoweth and Mohammadi2016) and in the worst case scenario, the loss of independence can lead to the loss of a will to live: ‘I would rather die than live in a care home’ (Österlind et al., Reference Österlind, Ternestedt, Hansebo and Hellström2017). For all the individuals involved in this study, the importance of ‘wanting’ to re-establish links with family and home was identified as an influential factor in moving to a care home. This included the maintaining of relationships with family members and friends as well as the development of new relationships with staff (Saunders and Heliker, Reference Saunders and Heliker2008; Lee, Reference Lee2010; Sussman and Dupuis, Reference Sussman and Dupuis2012; Brandburg et al., Reference Brandburg, Symes, Mastel-Smith, Hersch and Walsh2013; Falk et al., Reference Falk, Wijk, Persson and Falk2013; Ryan and McKenna, Reference Ryan and McKenna2015). Some individuals who were ‘wanting to connect’ with other individuals within the home identified difficulty in developing relationships, citing frailty as an inhibiting factor (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Simpson and Froggart2013). In addition, developing interpersonal relationships with staff was perceived both positively, ‘they treat you like one of their own’, and less favourably, ‘they just do what they have to’, illustrating less-meaningful relationships (Eika et al., Reference Eika, Espnes and Hvalvik2014). The significance of relationships is highlighted within the systematic review of Fitzpatrick and Tzouvara (Reference Fitzpatrick and Tzouvara2019). The authors related potential facilitators and inhibitors that corresponded with Meleis's personal and community transition conditions within the theme of interpersonal connections and relationships for older people. These connections centred on co-residents, care facility staff, family and significant others beyond the care facility. Moreover, when considering how relationships can be created and sustained, the Senses framework of Nolan et al. (Reference Nolan, Brown, Davies, Nolan and Keady2006) identifies six senses that are seen as prerequisites for good relationships within the context of care and service delivery, and that essentially good care can only be delivered when the ‘senses’ are experienced by all the groups involved. The Senses framework recognises the importance of each person in a relationship experiencing a sense of significance and feeling that they matter as a person.

Research has identified that following care home admission, individuals can lose their previous social networks and are unable to create new ones (Zamanzadeh et al., Reference Zamanzadeh, Rahmani, Pakpour, Chenoweth and Mohammadi2016) and are at risk of feeling lonely and isolated (Brownie et al., Reference Brownie, Horstmanshof and Garbutt2014). Moreover, it is recognised that care staff have an important role to play in encouraging new individuals to develop new relationships (Cooney, Reference Cooney2012; Križaj et al., Reference Križaj, Warren and Slade2018). Conversely, Eika et al. (Reference Eika, Espnes and Hvalvik2014) stated that staff lacked awareness about the impact of the transition for the older person and their next of kin when moving to a care home. Moreover, staff must be aware of the feelings surrounding the move for both the individual and their families, such as missing loved ones and loneliness (Ellis and Rawson, Reference Ellis and Rawson2015). Therefore, care home staff and family have the potential to support each individual's identity by maintaining relationships and promoting new social connections. This is in keeping with the guidelines of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2015) which indicate that an individual's care plan should include ordinary activities outside the home to encourage participation in the community, reduce social isolation, and build personal confidence and emotional resilience.

The findings from this study clearly identify that for the majority of individuals the first four- to six-week period following entry to a care home was unsettling, and for some an upsetting experience. This study is significant because the data were collected in the early post-relocation phase and there is limited research that has explored the experiences and perspectives of older people during this crucial time period. Moving home has already been identified as a major life stressor for an older person (Ellis, Reference Ellis2010; Brandburg et al., Reference Brandburg, Symes, Mastel-Smith, Hersch and Walsh2013; Sury et al., Reference Sury, Burns and Brodaty2013; Ryan and McKenna, Reference Ryan and McKenna2015). Our study has identified that individuals report having experienced a loss of autonomy, independence and identity, making adjustment to life in a care more challenging, with individuals trying to cope with new familiarities and care routine practices with little direction or guidance (Bradshaw et al., Reference Bradshaw, Playford and Riazi2012; Cooney, Reference Cooney2012; Brandburg et al., Reference Brandburg, Symes, Mastel-Smith, Hersch and Walsh2013; Rieldl et al., Reference Riedl, Mantovan and Them2013; Ericson-Lidman et al., Reference Ericson-Lidman, Larsson and Norberg2014; Križaj et al., Reference Križaj, Warren and Slade2018).

Conclusion

It is very important that individuals who move to a care home are enabled to lead full and purposeful lives, and to realise their ability and potential. Maintaining continuity between the person's past and present role is an important factor in the adaption process. Within this study, care home staff were primarily perceived as providers of health-care delivery only and not as people with whom to develop relationships. It is important that both care home staff and individuals actively seek out opportunities for engagement with the wider community. Care home managers should be willing to look beyond traditional models of support and seek voluntary/community organisations to undertake personalised social care support. ‘My Home Life’ is an international initiative that aims to promote quality of life and positive change in care homes for older people. Creating a sense of community is at the heart of ‘My Home Life’, not only between residents, relatives and staff but also between care homes and their local communities through community engagement events and inter-generational activities. It is through connection with family and friends, and by engaging with communities, that wellbeing can be enhanced and feelings of ‘Waiting and Wanting’ minimised. Key recommendations from this study include the need to raise awareness of the significance of this critical time period and to amend policy and practice accordingly. This could include the development of a bespoke induction programme for each new resident facilitated by a senior member of the care home staff with overall responsibility for working in partnership with individuals and families, in addition to the broader health and social care team. The uniqueness and intrinsic value of individuals should be acknowledged in partnership with the individual and their relatives that includes their values and preferences in terms of physical and psychological safety and promoting independence. The promotion of maximum independence and rehabilitation should be afforded by all care staff taking account of advice and recommendations from relevant health and social care professionals to support a more positive transition for new residents, relatives and care home staff. Therefore, it is imperative that individual and human rights are safeguarded and actively promoted within the context of services provided by the home and an individual should have access to all the information and advice they need to make informed decisions, including advocacy services.

Limitations of study

It is recognised that 70 per cent of people in care homes have dementia or severe memory problems (Alzheimer's Society, 2019). The exclusion of older people with cognitive impairment may be seen as a limitation of this study. However, as the study was carried out over a 12-month period and relied on participants’ ability to recall and reflect on their experiences in an interview situation, it was important to select participants who would ensure that the residents’ voice was heard as this is often absent from this type of research.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the older people who participated in the study and the care managers and care home managers who assisted with recruitment.

Author contributions

All authors have agreed on the final version and meet all four International Committee of Medical Journal Editors criteria for authorship: substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, and drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content.

Financial support

This work was supported by a Martha McMenamin Scholarship (MON).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Ethical standards

Ethical approval for the study was obtained through the Ethics Filter Committee of Ulster University, the Office for Research Ethics Committees Northern Ireland, and the Clinical and Social Care Governance Committee of the Health Care Trust.