They say we must never forget Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the Daigo Fukuryūmaru, Fukushima…. But for the vast majority of us who did not directly experience those events ourselves, this slogan is an impossible command. Nevertheless, we continue to refresh our individual experience and memory through continuous contact with monuments.

—Takashi Arai (photographer, Fukushima Prefecture)Japan has been called an “earthquake nation.” According to art historian Gennifer Weisenfeld (Reference Weisenfeld2012, 13), disasters have historically served as a transformative force in Japan, influencing not just society and politics, but art and culture as well. Yet, as Peter Duus (Reference Duus and Kingston2012, 175) enjoins us to remember, disasters are also always within the country's “living memory” due to their frequency. Certainly, one such disaster, both transformative and still very much alive in national memory, occurred on March 11, 2011, when Japan experienced the largest earthquake in its recorded history. This magnitude 9.0 quake devastated the northeastern Tōhoku region of the main island of Honshū, crumbling buildings and causing widespread landslides and fires. More terrifying yet was the tsunami it triggered some forty minutes later that sent fifteen-meter-high waves surging inland as far as ten kilometers, washing away everything in their path—vehicles, buildings, lives (Gill, Steger, and Slater Reference Gill, Steger, Slater, Gill, Steger and Slater2013, 3–6). Due to its sudden and destructive power, the 3.11 “Triple Disaster” (so named to include the earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear meltdown) quickly began to be discussed in Japanese media using the discourse of sōteigai or the “unimaginable” (Creighton Reference Creighton2014, 112).

When news of the tsunami first broke, the subsequent deluge of on-the-ground YouTube videos allowed anyone to distribute images online, contributing to what art historian Michio Hayashi (Reference Hayashi, Morse and Havinga2015, 171) labels the “rapid and unstoppable spectacularization of 3/11.” Foreign press pictures documenting the affected sites went after the “photographic effect” that accentuates tragedy and fear in order to sell papers or generate online views (Figueroa Reference Figueroa, Geilhorn and Iwata-Weickgenannt2017, 60–61). Meanwhile, Japanese disaster photography, which rarely draws attention to the suffering of individual victims, chose instead to employ metaphor when attempting to capture the disastrous events (Morse and Havinga Reference Morse, Havinga, Morse and Havinga2015, 148). A central issue informing disaster representation is therefore what constitutes a “proper” temporal, spatial, or affective distance from the original event. Testimonies from the epicenter are often regarded as the most “authentic,” and photographer Arai Takashi's epigraph that beings this article questions how those with no direct experience of 3.11 can memorialize the event. And this is the sentiment of a Tokyo-based photographer embedded in and taking pictures of Fukushima following the disaster.

More crucially, in their volume Fukushima and the Arts, editors Barbara Geilhorn and Kristina Iwata-Weickgenannt (Reference Geilhorn and Iwata-Weickgenannt2017) ask how should and how could the arts respond to such a catastrophe? Scholars observe that technology has played a key role in responses to 3.11. Marylin Ivy (Reference Ivy, Morse and Havinga2015, 191) notes the enduring power of cellphone pictures and family albums after the Triple Disaster, yet the intertwining of technology, documentation, response, and memorialization goes even further. This is a fact noted by Alexis Dudden (Reference Dudden2012, 349) in relation to the widespread usage of Twitter and blogging platforms to document the unfolding crisis of Fukushima, and by Theodore C. Bestor (Reference Bestor2013, 766) when reporting on the Reischauer Institute's efforts to archive as much digital media related to the event as possible. In Japan, earthquakes and tsunami have also served as the inspiration for a popular series of video games.

This article centers on an analysis of the eponymous first game in the Zettai Zetsumei Toshi series (ZZT; literally “The Desperate City,” but known in North America as Disaster Report). Originally developed in Japan for Sony's PlayStation 2 home console in 2002, the game was subsequently fully localized and released in North America as Disaster Report and in Europe as SOS: The Final Escape in 2003.Footnote 1 In this series of survival action-adventure video games, players assume the role of a disaster victim and must use limited resources to navigate and escape from earthquake- and tsunami-stricken Japanese cities while rescuing other computer-controlled survivors and scavenging for tools and equipment.

When discussing video games, it is tempting to rely on the axiom that the medium is uniquely equipped to affectively engage players owing to its interactivity and immersion. In this formation, video games, with their divergent narrative paths, customizable characters, and multiple endings, become superior to all other “passive” forms of media consumption. However, these hallmarks of gameic interactivity could equally be thought of as a natural extension of what cognitive grammar approaches to literature regard as “fictive simulation,” or the ways in which our mind actively anticipates and simulates meaning from written texts (Harrison et al. Reference Harrison, Nuttal, Stockwell, Yuan, Harrison, Nuttal, Stockwell and Yuan2014, 13). This theory suggests that reading literary texts, or watching films, is not nearly as “passive” as commonly thought. Far from isolating video games from other media, game texts can teach us valuable lessons about how to engage with other kinds of narratives, including literature and film, both “high-culture” forms that have previously dominated the focus of academic thinking about representation and trauma.

As a scholar of modern Japanese literature and popular culture, I analyze games as texts that comment on complex social and personal issues prevalent in Japanese society, including traumas. It is likely impossible to speak of how a particular video game might affect all users. Emotional engagement with a virtual world or virtual characters is incredibly complex, dependent on a variety of factors, and highly personalized. Ethnographies centering on the responses of real-life Japanese players to a particular game are instructive, but often necessarily limited in size and scope.Footnote 2 They at times also homogenize the plurality of narrative and emotional experiences, not to mention the more customizable aspects that define the medium, in an attempt to distill a game down to a single, universal affective mode. When discussing artistic responses to 3.11, Hayashi (Reference Hayashi, Morse and Havinga2015, 177) reminds us that, in fact, nothing could be “more treacherous” than reinforcing the existence of a collective understanding of the disaster.

Instead, artistic representations of disaster should strive to capture “not only visible, but also invisible things” (quoted in Figueroa Reference Figueroa, Geilhorn and Iwata-Weickgenannt2017, 67). This is the opinion of photographer Imai Tomoki, who reflects on his own art photos from Fukushima and discusses the difficulty of capturing radiation on film, something invisible to the naked eye. Invisibility is not limited to radioactive particles. Indeed, media coverage of 3.11 sought to make invisible and flatten nuanced differences among victims and their testimonies in order to make the event more relatable for those outside of it and produce an image of unified national sentiment (Hayashi Reference Hayashi, Morse and Havinga2015, 167). Hayashi argues, “So many art projects and visual representations dealing with the disasters of 3/11 aimed at alleviating the pain of the survivors, reemphasizing community spirit … or offering audiences more hopeful visions of the future” (169).

My central argument is that playing Disaster Report, or a game like it, gives us storytelling and simulative tools to help make visible the marginal “victims” and “narratives” of survival that are often erased under the collective rhetoric of national trauma. As I will show, this occurs in Disaster Report at two main levels: first, through a game narrative that does not simply reinforce dominant governmental soundbites, but anticipates Japanese reactions to the corporatist and deeply entrenched political hierarchy of postwar Japan that emerged in the aftermath of the nuclear meltdown; and, second, via gameplay mechanisms that communicate a sense of victimhood to the player while emphasizing individualized stories of survival and personal decision making on the part of the player. I pay particular attention throughout this article to disaster photography, as its presence within the larger interactive framework of the game further strengthens the process of meaning-making when players revisit their own “virtual memories” of survival as captured through in-game pictures. If events like 3.11 must exist simultaneously in national collective memory and the individual memories of those who experienced it, then video games that allow players to “live” as someone else at the character level and inhabit an emotional circumstance with which they may be entirely unaccustomed represent one possible way that we can reintroduce individual, personalized narratives of survival into a disaster as far-reaching as 3.11.

A Social Narrative of Survival for “Generation Zero”

It was three days after the Great East Japan Earthquake (Higashi Nihon Daishinsai) that a small studio named Irem quietly cancelled development of its latest video game. The software in question was Summer Memories, the fourth entry in its popular Zettai Zetsumei Toshi series. Irem, like any entertainment publisher attempting to market a resonant work in the face of a national tragedy, made the logical choice to cancel development out of respect for the victims. While the game's designer and series creator Kujō Kazuma has since resumed development on an updated version of the game for PlayStation 4, his comments about the cancellation evidence a general unease with placing entertainment works about trauma at the same level as real-world suffering and mourning.Footnote 3 He states, “This may sound imprudent, but what we were trying to simulate in our game actually happened in reality on March 11.… After seeing the effects of the earthquake and tsunami, it just became impossible to set a release date for that title” (quoted in Parish Reference Parish2012).

While a game such as Disaster Report, crafted nearly ten years prior to 3.11, can never provide an accurate representation of what it is like to experience an event such as the Great East Japan Earthquake, there is still much to learn from a pop culture exploration of catastrophe. When Disaster Report was first released in 2002, its socially relevant narrative capitalized on established tropes of both disaster fiction and the survival genre of video games. Anime scholar Susan Napier (Reference Napier1993, 330) identifies what she terms “secure horror,” or disaster stories and films in Japan that feature definitive narrative closure and an optimistic ending where evil is ultimately defeated. This approach was made famous globally by Honda Ishiriō’s classic 1954 monster movie Gojira (1956, Godzilla, King of the Monsters!). Many video games use the visuality of “secure horror” in the service of a larger narrative about a monster or alien invasion, or choose to express disaster as a monster, alien, or otherwise supernatural force that players must defeat. This is the case dating back at least to 1987 and the original Final Fantasy role-playing game (Square). Thus, while Disaster Report fits into this pop culture trajectory, the game renders the earthquake in non-allegorical terms, and further links the disaster to Japanese corporate malpractice with ecocritical overtones throughout the game's narrative. In this way, the fiction of Disaster Report has something to say both about the Triple Disaster and what Japanese cultural critic Uno Tsunehiro (Reference Tsunehiro2008) identifies as a “new” trend in Japanese pop culture narratives following the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001.

The game begins in the then near-future on June 21, 2005. Players control twenty-five-year-old newspaper journalist Sudō Masayuki, who is on his way to begin a new job assignment at the local newspaper (see figure 1). The game starts aboard an automated train as Masayuki heads from the airport to his new home of Capital City, a metropolis built atop a manmade island.Footnote 4 It is during this train ride that shindo 6 levels of ground motion strike (the equivalent of a magnitude 8.0 or 9.0 earthquake), collapsing bridges, crumbling buildings, and sending the entire island gradually sinking into the Pacific Ocean. Over the next three days (roughly ten hours of playtime), Masayuki must safely traverse the sinking city and make his way to an evacuation zone while avoiding obstacles and rescuing other survivors.

Figure 1. Sudō Masayuki rests on a street corner beside Higa Natsumi. © Granzella Inc.

One such survivor is twenty-year-old college student Aizawa Mari, whom players rescue from a hanging train car early in the game. Mari becomes Masayuki's companion throughout the majority of the escape until a branching point in the narrative where players must decide either to travel with Mari to her apartment to rescue her dog Gen, or alternatively team up with another survivor, high school student Higa Natsumi, as she attempts to reunite with her lost brother. In the interest of full disclosure, during my playthrough I chose to rescue the dog. Another non-player character central both to the story and to my conclusion about disaster photography is thirty-year-old freelance photojournalist Jinnai Kōji. Jinnai is a former employee of the local newspaper and has stayed behind to document the disaster. In the process, he uncovers information about a potential conspiracy related to the earthquake.

Towards the end of the game, the earthquake is revealed to have been caused by human negligence rather than forces of nature. In the game's fiction, beginning in 1985, the prime minister of Japan along with Hatta Takumi, director of the Ministry's Land Development Department, initiated a plan to reclaim land deep under the ocean and convert it into a stable foundation on which entire cities could be built. To do this, they utilized a new cutting-edge technology known as the Honeycomb-Caisson Method, and after ten years of construction, what began as a tiny spur of rock near Hirasaki Island in N Prefecture was reborn as Capital City.

The game ends with a rooftop confrontation atop the Capital City Central Tower as the heroes (Masayuki, photojournalist Jinnai, and either Mari or Natsumi depending on the narrative branch selected by the player) attempt to signal a rescue chopper but are confronted by Hatta and his armed goons. Journalist Jinnai is shot and killed by Hatta, who falls off the skyscraper to his death. Disaster Report features seven different game endings—some optimistic, others tragic—depending on the choices made throughout the game's multiform narrative.

Uno Tsunehiro (Reference Tsunehiro2008, 13) argues for a rupture between an “old imaginative power” (furui sōzōryoku) and a “contemporary imaginative power” in Japanese pop culture narratives (gendai no sōzōryoku). This “old imaginative power” was widespread between 1995 and 2001 and can be found in representative works from the period, such as Anno Hideaki's Neon Genesis Evangelion (1995–96). These narratives drew on the social and political climate of 1990s Japan, which saw the bursting of the bubble economy and the domestic terrorism of the Tokyo subway sarin gas attack in 1995 (14). Consequently, Uno argues that these works reflect a sense of general helplessness felt by the Japanese people. Specifically, individual character agency, or the ability to “do” or to “not do” something (suru/shinai), was replaced in these mid-1990s narratives with an imposed worldview where a seemingly intractable situation was outside anyone's control (“it is” or “it isn't”—dearu/dewanai; 18).

Napier (Reference Napier1993, 334) identifies a similar tendency even earlier, noting that Komatsu Sakyō’s 1973 science fiction novel Nippon Chinbotsu (Japan Sinks), in which Japan is destroyed by multiple disasters, can be read as the “secure horror” genre, but that “the film's action and ending are downbeat, emphasizing loss over success.” Napier suggests that the 1973 film adaptation of Nippon Chinbotsu “allowed its audience the melancholy pleasure of mourning the passing of traditional Japanese society.” She labels the film an “elegy to a lost Japan” (335). Game designer Kujō notes that the sinking of Capital Island was heavily influenced by Nippon Chinbotsu and the manga series Survival (1976–78) by Saitō Takao (Parish Reference Parish2012; Szczepaniak Reference Szczepaniak2012). It is no surprise then that themes prevalent in Japanese disaster narratives, such as the erosion of traditional values and skepticism towards governmental power and corporate success, are firmly on-screen in Disaster Report.

In their book Japan Copes with Calamity, Gill, Steger, and Slater (Reference Gill, Steger, Slater, Gill, Steger and Slater2013, 15) note the importance of framing narratives in the process of coping with and rationalizing disaster: framing narratives are “shared explanations of situations that are often too terrible and/or too complex to be easily grasped and rendered.” Historically in Japan, religion and the supernatural have often served as the framing narrative in cases of natural disaster. However, in the aftermath of the Great East Japan Earthquake, the two dominant framing narratives that emerged were that of the tensai or “natural disaster” and the jinsai or “manmade disaster.” The “natural” disasters of the earthquake and tsunami were quickly contrasted with the “manmade” Level 7 meltdown of the Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant in Fukushima Prefecture that came to be attributed to negligence and a cover-up by the Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO). In addition, those local communities that had accepted nuclear power plants in return for large subsidies were also criticized in the aftermath of Fukushima (19–20).

I read the Honeycomb-Caisson technology used in Disaster Report as an analog for nuclear power. Construction reports, newspaper clippings, and other personal documents can be found scattered within the various in-game environments, and they serve to fill the player in on background information about this technological breakthrough. The player learns that the Honeycomb-Caisson method stands as a testament to the ingenuity of the Japanese government to develop and harness new and transformative technologies. In much the same way, the immense energy beneath the surface of Japan that causes the disasters in Nippon Chinbotsu is almost prided in the novel as if it “were somehow a positive cultural attribute” (Napier Reference Napier1993, 349). In his discussion of Japan's fraught relationship with nuclear energy, Yoshimi Shun'ya argues that the country's aversion to nuclear power was gradually altered through events like the Osaka Expo of 1970 that was powered with General Electric's nuclear reactor at the Tsuruga plant. National events such as this showcased the utility of nuclear power and subtly worked to erase the memories of Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and the Lucky Dragon No. 5 fishing boat that was caught in US H-bomb tests in 1954 (Yoshimi Reference Yoshimi Shun'ya and Loh2012, 328, 329). We see this same lauding of a promising, yet dangerous, new technology at play in the governmental rhetoric inside Disaster Report.

However, the metaphor of the Honeycomb-Caisson method reinscribes the destructive nature of nuclear energy in much the same way that the Daiichi plant meltdown did for Japanese residents and the global community. By placing the gameic island's disaster within a larger conspiracy of governmental malpractice, the social narrative in Disaster Report deftly pairs environmental concerns and political opposition with the game's take on a Hollywood-style disaster movie. As Alexis Dudden (Reference Dudden2012, 355) writes, “TEPCO's falsifications together with the government's fumbling obfuscated the explosions’ poisoning of parts of the nation's food chain, groundwater, and streams, not to mention the Pacific Ocean.” These same sorts of ecological concerns are revealed in the game as Masayuki and Mari discover that contaminated waste is a byproduct of the Honeycomb-Caisson technology. The Land Development Department has been knowingly dumping this toxic waste into the Kiser River for ten years during construction of the island, slowly causing the bedrock to erode and making the area more susceptible to earthquakes. As is common with real-world protests against nuclear energy, local residents in the game had complained to the government to no avail, prompting anti-island activists to occupy the airport and threaten a class-action lawsuit.

In the face of natural destruction and seemingly intractable governmental corruption and malpractice, what is the hero of a disaster video game to do? Uno (Reference Tsunehiro2008) posits that the terrorist attacks on New York's World Trade Center on September 11, 2001, gave birth to what he terms “generation zero” (zero nendai; or roughly 2000–08) and its new, “contemporary” form of imaginative power that has influenced pop culture narratives since then. Uno characterizes this period with works such as the film adaptation of Takami Koushun's novel Battle Royale (2000) and the wildly popular manga series Death Note (2003–06) by Ohba Tsugumi and Obata Takeshi (20–21). Both of these pop culture works emerged in the aftermath of 9/11 and were imbued with a newfound “sense of survival” (savaivu-kan). Generation zero characters, and by extension the fans themselves, came to embody the idea that one had to collect one's strength and make a decision to act when faced with a difficult situation, even if this meant hurting others or breaking societal rules (23). The narrative of Disaster Report incorporates a resonant political critique that aligns with Uno's description of the pessimistic narratives of “old imaginative power,” where a “society gone wrong” (machigatta shakai) values technological innovation, corporate profits, and political influence over the safety of its citizenry (21). However, the gameplay structures of Disaster Report actualize Uno's criteria of cultural works from generation zero. Not only does the game clearly express the “sense of survival” integral to Uno's thesis, but it also gives players agency to make difficult choices within a system of constraints.

Limited Engagement

When discussing “theatrical” or staged art photography representing the 3.11 Triple Disaster, Hayashi contends that it need not be dismissed as false or secondary to realist portrayals in the documentary mode. While artificial, he suggests that this type of framing “paradoxically conjures up that experience's heightened sensory confusion and lack of analytical distance” (Hayashi Reference Hayashi, Morse and Havinga2015, 167). This notion evokes the traumatic experience for Freud (Reference Freud, Dufresne and Richter2011, 60) in his Beyond the Pleasure Principle, which is reproduced repetitively precisely because of the deferral of understanding at the time of trauma. Like theatrical photography, Disaster Report is a similarly staged simulacrum of earthquake survival, but one that retains the experience of asynchronicity, inherent to trauma, through a process of design-by-subtraction that I term “limited engagement.”

Game studies scholar Ian Bogost (Reference Bogost2011, 19) argues that if video games are to foster empathy for real-world situations, then players should be cast as the “downtrodden rather than the larger, more … powerful [characters].” One of the primary examples he cites in support of this form of gameic empathy is a Japanese-made PlayStation 2 adventure game titled Ico (Team Ico, 2001), in which a young boy with horns must help a princess escape a haunted castle. Director Ueda Fumito's game is played with minimal dialogue. Since Ico, the titular horned boy, and princess Yorda speak different languages (represented to the player through gibberish), the player must press a button to have Ico utter a simple “wait” or “follow” command to Yorda—seemingly the only point of communication between them. Yorda is unable to climb many obstacles by herself, so a central gameplay mechanic involves helping her traverse the environment and holding her hand while leading her through the game's various areas and puzzles. When shadow creatures manifest to recapture the princess, Ico is armed with only a stick to fend off these overpowering enemies.

Bogost is not alone in singling out these Japanese games for praise. Fellow game studies scholar Miguel Sicart (Reference Sicart2009, 215) finds in Shadow of the Colossus (Team Ico, 2005, Wanda to Kyozō), the spiritual sequel to Ico, an open form of gameplay that leaves ethical reasoning to the players, rather than imposing an overarching good-evil structure. For this reason, Sicart views Shadow of the Colossus as an exemplary game that validates players as moral agents within their own play sessions. Similarly, Brian Upton (Reference Upton2015, 268) also cites Ico as a case study where the gameplay and narrative play align with “powerful results.”Footnote 5

It is telling that Bogost, Sicart, and Upton—three scholars from outside Asian studies—all gravitate to the same Japanese games to validate their various arguments about the expressive potential of the medium. What make these titles memorable from a gameplay perspective are the ways in which they strip away many classic video game “superpowers” in order to convey a sense of unadulterated exploration or survival to the player. In much the same way as Uno's “generation zero” narratives, these games serve as prime examples of a Japanese design strategy that entices players specifically by casting them as underdogs against seemingly insurmountable odds.

Throughout this article, I use the term “limited engagement” to refer to a constellation of gameplay features designed to communicate a sense of vulnerability to the player through subtracting character skills, limiting in-game items and narrative possibilities, or deliberately controlling the pace and progression of gameplay. The word “limited” is not intended as a pejorative remark. Rather, Japanese video games have a long history of implementing simulative “limitations” to great immersive effect. The strategy gained public attention with its implementation in the Japanese survival-horror series Resident Evil (Capcom, 1996, Baiohazādo). In that game, the central goal of escaping from a mansion while avoiding flesh-eating zombies is made all the more difficult due to the deliberate scarcity of ammunition and in-game healing items scattered throughout the environments.

Permanently or temporarily disempowering characters not only heightens the challenge of gameplay, but also is an effective means for subverting the tropes of traditionally hyper-strong, hyper-masculine, and seemingly invincible video game protagonists. Limited engagement strategies further function as a form of “amplification through simplification,” a process suggested by comic artist and theorist Scott McCloud (Reference McCloud1993, 30–31), where abstracting an image could serve to increase identification and amplify emotional resonance for a wide swath of readers. In the section that follows, I examine three main implementations of limited engagement strategies that I argue alter the positionality and scale of the game experience, forcing the player to “live” the earthquake from within by reducing the catastrophe to an interactive human scale that makes manifest the “lives” and “testimonies” of virtual survivors.

Surviving at the Margins

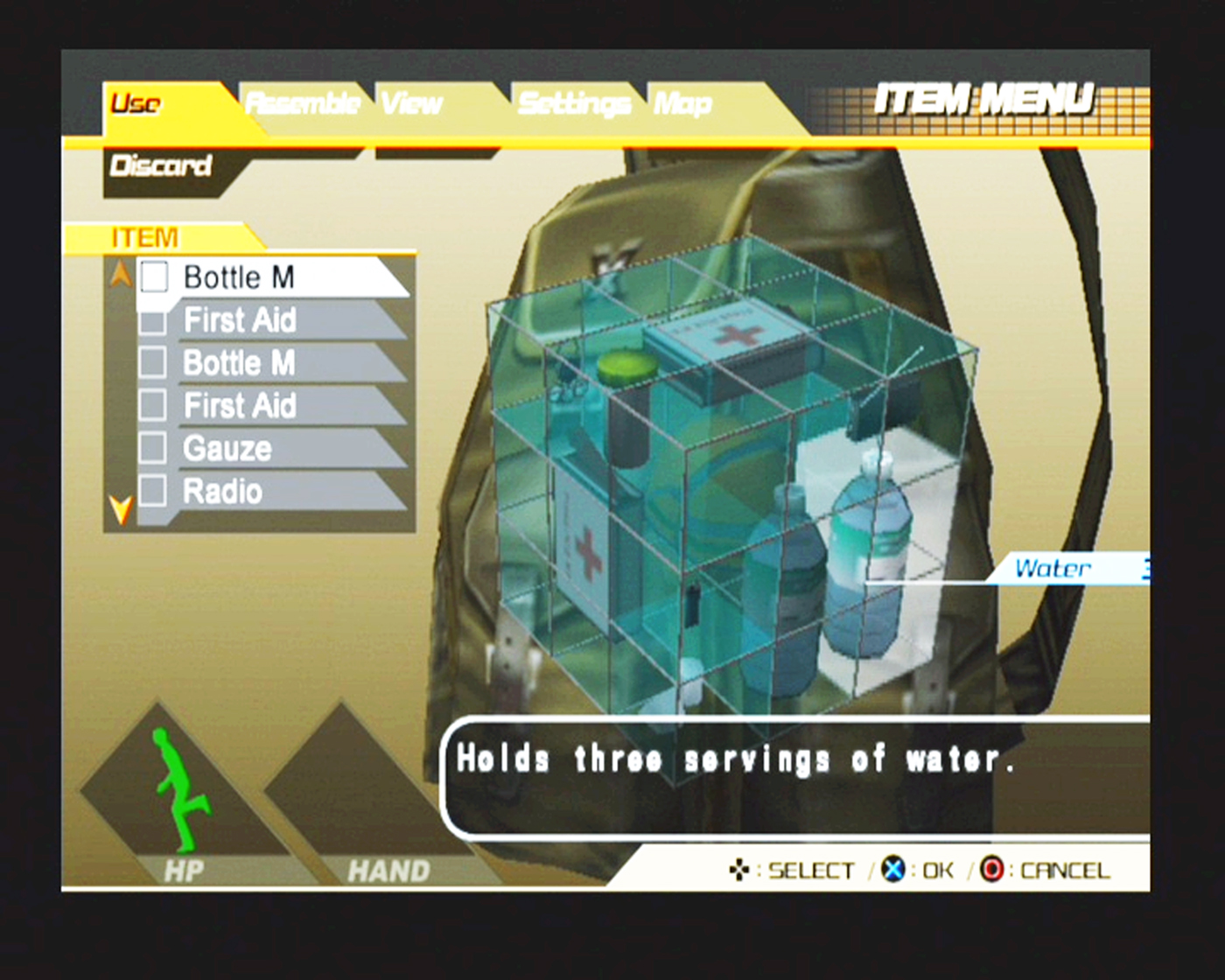

Pop culture depictions of catastrophe, such as Hollywood-made disaster movies, often include the spectacle of mass citywide destruction and images of dead bodies. Seeing the destruction of recognizable landmarks on a mass scale is one of the perverse joys of disaster entertainment and photography (Weisenfeld Reference Weisenfeld2012, 80–81). Disaster Report also features collapsing buildings, falling rubble, and the occasional cadaver (see figure 2). However, apart from the game's opening cinematic, which showcases the large-scale destruction of Capital City as the earthquake hits, the subsequent survival experience is remarkably personal: Masayuki and Mari move on foot together through damaged buildings, duck underneath debris, and help each other over cracks in the environment. The game lets us experience individual acts of survival in three main ways: first, through showcasing real-world survival practices; second, through elevating the narratives of individual survivors within the game; and finally, by letting players craft their own individualized stories. Taken together, these three examples of limited engagement make visible the myriad individual responses to disaster trauma that are often omitted in Hollywood-style pop culture narratives.

Figure 2. Masayuki mimics the real-world earthquake preparedness drill of “drop, cover, and hold on” amidst citywide destruction. © Granzella Inc.

Health systems, which convey to the player the declining or increasing vitality of the main character(s), have existed since the advent of video games. Most conventional action-adventure video games feature a health gauge visible onscreen to communicate character well-being to the player. The standard green HP (Health Points) bar for overall health (visible in figure 2) depletes as Masayuki tumbles to the ground during in-game aftershocks or is hit by falling debris. However, unique to Disaster Report is a second system for conveying vulnerability—a gauge immediately underneath the green HP bar comprised of a series of blue squares (see, again, figure 2). This is a QP (Quench Points) gauge, and it measures Masayuki's hydration levels. Squares from the QP gauge diminish as Masayuki exerts himself physically. The game requires a deliberately slow default walking pace. More strenuous activities, such as pulling oneself up from a ledge or sprinting a few city blocks, quickly deplete the gauge. Players must constantly monitor both physical well-being and hydration levels while playing. While the HP gauge can be replenished by using accumulated bandages and first-aid kits, QP can only be “refilled” by drinking fresh water. Throughout the game, players must constantly look for drinking fountains, sinks, and water trucks from which to quench their thirst. Drinking water becomes doubly important as it provides the only opportunity for players to save their game progress to their memory cards. It is in this unique gameplay mechanic that Disaster Report not only communicates the fragility of the human body but also ties itself to the specific importance of fresh water in survival situations, particularly after the Great East Japan Earthquake.

As Brigitte Steger (Reference Steger, Gill, Steger and Slater2013, 60–62) explains, finding fresh spring water sources became of paramount importance after the Tōhoku earthquake as the water supply to many local towns became cut off. Water had to be drawn by hand from wells and then always boiled either on propane stoves or outdoor fires to kill bacteria. Disaster Report honors the importance of water within a survival situation. Rather than provide abundant sources of drinking water, the game forces players to carefully and strategically monitor their actions and physical exertions since the location of the next water source is never known. Restricting water sources is one of the main ways Disaster Report fosters limited engagement. Hastily drinking contaminated water to refill your QP gauge will deplete health and make Masayuki ill. It is only by locating a water purifier, or independently scavenging the various parts necessary to craft the item, that dirty water can be made potable within the game.

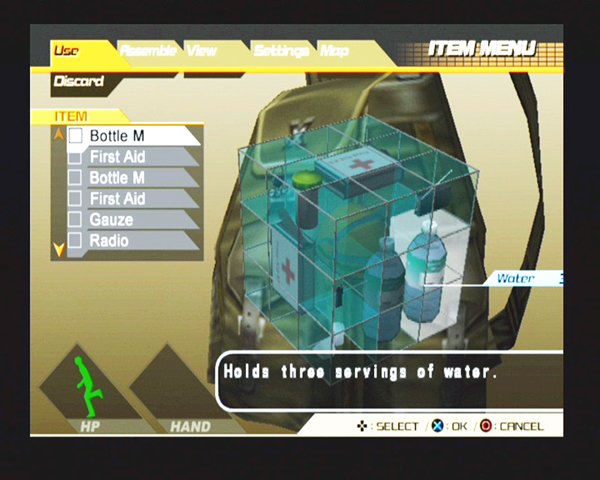

As the game progresses, Masayuki can collect various sizes of plastic bottles that can be used to transport water throughout the journey or be given to other companions (see figure 3). Maintaining not just Masayuki's personal hydration level but also the levels of his companions becomes another central goal of gameplay. Looking after your friends directly influences the degree to which the computer-controlled allies will “bond” with you, so it is in your best interest to continually offer water to your companions rather than guzzling it all for yourself.

Figure 3. Inventory management is carried out by storing or removing items from Masayuki's backpack. This bag contains two plastic bottles each with three servings of fresh water. © Granzella Inc.

Game researcher T. L. Taylor (Reference Taylor2006, 154) rightly notes, “We do not shed culture when we go online and enter game worlds, nor do designers create these incredible spaces in a vacuum.” Video games ask us to interact with a variety of social and personal stories. These avatar interactions structure the expanded narrative of Disaster Report that gives weight to the testimonies of individual survivors. In one memorable gameplay section, Masayuki must carry the injured editor-in-chief of the local newspaper on his back as the group makes its way to a shelter site in the repurposed May Stadium. Moving through the now evacuated sports stadium as the editor-in-chief tells his personal story of survival, players see the abandoned cots and water trucks used to aid victims. The scene evokes the real-world emergency shelters in the affected regions of Tōhoku where “sleeping on cold, hardwood floors, with little privacy and personal space, was immensely stressful” (Gill et al. Reference Gill, Steger, Slater, Gill, Steger and Slater2013, 9).

Throughout the game, Masayuki meets other ancillary characters whose personal accounts of survival color and add variety to the game. Whether these computer-controlled characters are discussing the difficulty of maintaining personal hygiene in a disaster zone (“Where am I going to live? Whatever. All I know is I'm taking a long, hot bath.”) or pleading with Masayuki to locate a lost family member, this second gameic strategy uses choreographed interactions between in-game survivors to offer highly personal, small-scale narratives that destabilize or at least reframe the nationalistic impulse of perseverance or “ganbaru” that emerged as a rallying cry for Japan in the immediate aftermath of the quake.

Indeed, while disasters are always localized phenomena, the idea of the modern “imagined community” has increased the sense of national ownership over trauma through collective narratives and publicly circulated images. This is an observation echoed by Theodore C. Bestor (Reference Bestor2013, 769), who adopts Arjun Appadurai's and Igor Kopytoff's framework of “cultural biographies” to discuss how 3.11 can be understood through “sets of expected or expectable events, images, responses, and resolutions.” In Disaster Report, these piecemeal stories from survivors become of equal importance for fashioning a larger narrative about what happened during the moment of trauma. This is a common rhetorical device used in Japanese atomic bomb literature, where a variety of individual testimonies are often included alongside that of the central protagonist, suggesting that no single narrative of survival should be regarded as representative (Orbaugh Reference Orbaugh2007, 212).

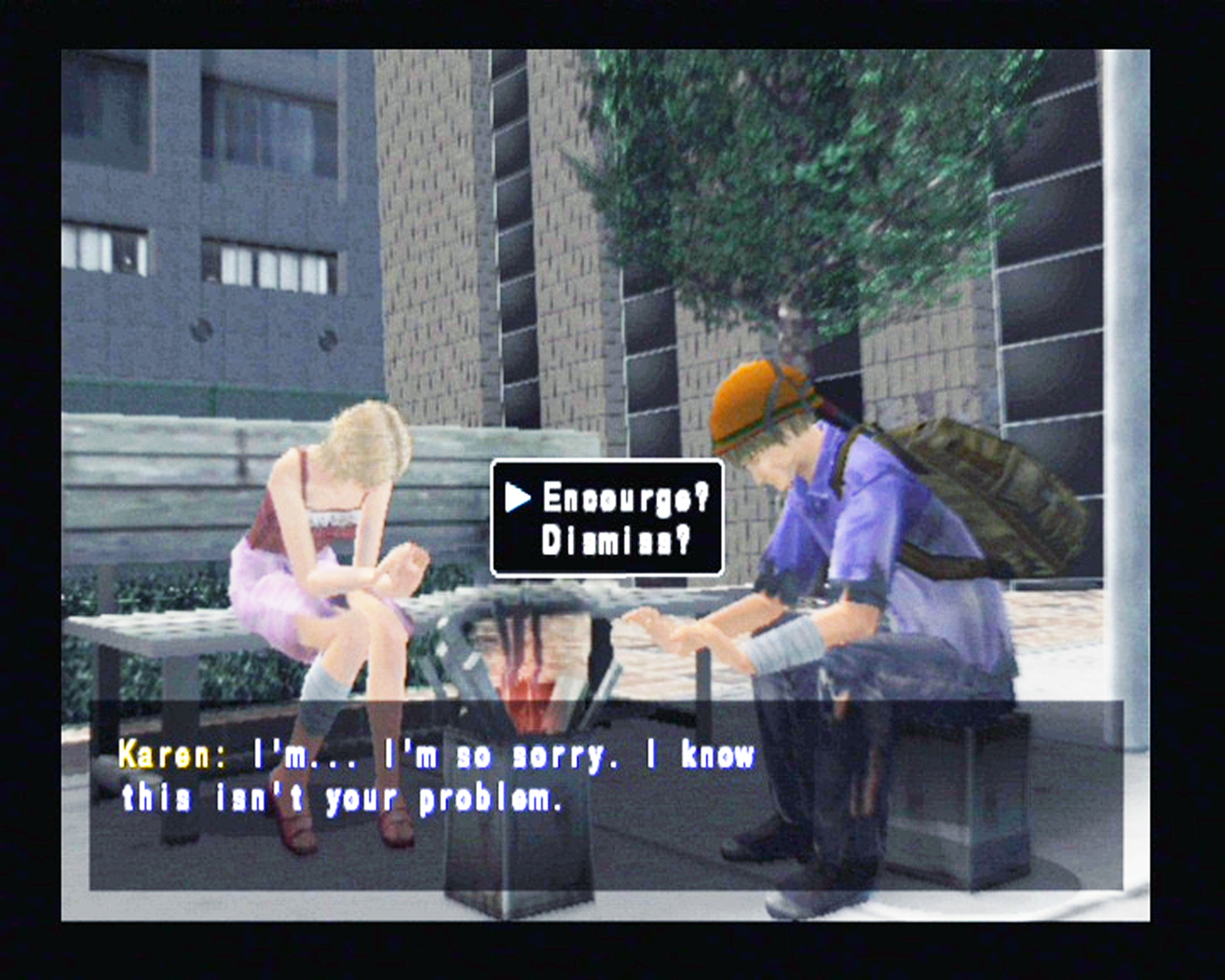

Finally, Disaster Report encourages players to make sense of their own survival experience within the game through a multiform narrative with different outcomes depending on the player's interaction with the other non-player characters. When discussing how trauma is interpreted, science historian Ruth Leys (Reference Leys2000, 282) argues that Freud's intention was to present trauma as a “psychical” or “historical truth” whose meaning had to be reconstructed and deciphered. In several moments, the player must either verbally encourage or discourage a virtual companion about his or her chance of making it out alive (see figure 4). This narrative malleability continues to the game's climax atop the Capital City Tower. Disaster Report includes two main ending variations that draw on existing disaster genre tropes of overcoming and sacrifice. In the “happy ending,” Masayuki and Mari are rescued by helicopter following the death of Land Minister Hatta. The game concludes with Masayuki vowing to write up the exposé with Jinnai's research and photographs once returning to the mainland. The more tragic ending has Masayuki and Mari climb a ladder to the roof of the building just in time to see the rescue chopper depart without them. With nowhere left to go, the couple embrace as the tower slowly sinks into the ocean.

Figure 4. Players must choose whether to encourage or dismiss other characters and whether to act in their own self-interest or in the name of shared survival. © Granzella Inc.

By including game endings where both characters escape, or both tragically die, Disaster Report strips away the sense of superiority and complacency commonly felt when engaging with entertainment representations of disaster. If players have made it to this ending scene, then this is because during a decisive moment earlier in the game, they chose to save their friends. At a point near the end of the game, Masayuki locates a rescue boat at Windrunner Park. Since the captain is set to leave in a few minutes, players must decide whether to board the vessel themselves or return to retrieve their friends, knowing that the boat will likely be gone when the group returns. If the player chooses to abandon his or her friends and ride to safety, the playthrough ends at that point and the credits roll. The game does not advocate for either outcome. Rather, these sorts of individual choices and personal narratives are necessary and validated within the complex survival simulation of Disaster Report.

Real-World Survival and a Debate over Imaginative Power

Game designer Kujō Kazuma was profoundly affected by the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake that devastated the city of Kobe in 1995: “The Hanshin Earthquake happened after I had already left [university], but I had friends who died because of that earthquake, and it made me realize the horrors of earthquakes. Earthquakes are much more of a threat and a reality than monsters and aliens and I felt that it was a theme that fit games” (quoted in Parish Reference Parish2012).

Kujō’s comments suggest a tension between designing a mass-market video game as both an escapist piece of entertainment and an educational tribute to lives lost in the Kobe disaster. Every time a massive earthquake has struck Japan during the series’ development cycle, first with 3.11 and again on April 14 and 16 of 2016 when massive earthquakes struck Kumamoto Prefecture in the southernmost island of Kyūshū, it has reignited controversy over whether future Disaster Report games should be cancelled or come to market. This debate is of course not limited to video games. Lorie Brau (Reference Brau, Geilhorn and Iwata-Weickgenannt2017, 179), for example, writes about a similar controversy that arose after the food manga series Oishinbo featured a storyline about a main character developing a nosebleed after visiting the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant.

In a similar fashion, tweets and anonymous postings on Japan's Ni Channeru (2channel or 2chan) message board forum evidence this ongoing debate over the imaginative power of Japanese visual culture and whether the skills and information received through video game play can transfer outside of the game world. Take, for example, the following two tweets from Japanese gamers made just one day after the Kumamoto quake:

@kon_nosuke—ZZT is called a disaster game. You learn a lot. For me—I was only watching a Let's Play video—but there was a bunch I didn't know. I get the feeling that you study as you play. (Kon Reference Kon2016)

@aoi_shinohara—Earthquakes are frequent, so a game where you learn ways to protect yourself, like ZZT 4, should certainly be released! This type of game is not imprudent, it's important! (Shinohara Reference Shinohara2016)

Both @kon_nosuke and @aoi_shinohara defend the ZZT series due to its potential to educate players about how to best prepare for and survive a natural disaster in real life. This player response was also apparent during the game's initial cancellation after the Tōhoku earthquake. According to Kujō, Irem received some five hundred letters requesting that development be resumed: “About a week after the earthquake we even received a letter from the earthquake and tsunami victim. There was a government employee who wrote saying that they were writing from a disaster struck area but not to cancel the game” (quoted in Parish Reference Parish2012).

According to Kujō, the majority of these letters testified to how “useful” the game series had been for current or past earthquake victims. The director became aware of how players were finding the survival information in the games helpful and gradually tried to incorporate more information into the game's sequels. He states, “When I saw the effects of what happened on March 11, I thought that I could make a game that is even more informative than in the past. And, when I make the next earthquake/disaster game I want to make it a lot more informative than in the past games” (quoted in Parish Reference Parish2012).

However, central to the logic of disaster game design, and video game design more generally, is that players and their avatars must perform gameplay actions that no real victim would ever attempt in a survival situation. One particularly memorable example from ZZT is when Masayuki must slide across a powerline on a clothes hanger to reach a previously inaccessible area of the game map. These actions keep players actively engaged over a multiple-hour-long campaign, but they are also at direct odds with crafting a realist disaster simulation. By the third entry, Kujō had become worried that players might model inappropriate behavior learned from the game in a life-or-death situation, so a disaster prevention specialist was hired as a consultant. However, even while Kujō gestures towards the didactic potential of his series, he also often contradicts himself, pointing out to the gaming press in a 2016 interview, “I'm not making games to educate players about disasters, so I wouldn't change a game's story for the purpose of providing that correct knowledge” (Fukami and Kujō Reference Makoto and Kazuma2016).

Game studies scholar Brian Upton (Reference Upton2015, 266) argues that knowledge that emerges from a video game is “portable” if it “applies not just to the work itself, but to our general grasp of the world and life within it.” Even while establishing this framework, Upton remains largely skeptical about the portability of video game skills, reasoning that most gameplay is designed to be self-contained and most mechanisms do not easily transfer out of the game.

This sentiment is echoed in the majority of tweets and posts surveyed for this article, which provide a more pessimistic take on Disaster Report’s social utility. In a 2chan thread from September 2016 titled, “What Happened to Zettai Zetsumei Toshi 4 and City Shrouded in Shadow?” (“Zettai Zetsumei Toshi 4 to Kyoei Toshi'tte Dō Nattan Da?”) anonymous users expressed discomfort over the game's proximity to actual events in Kumamoto:Footnote 6

Anonymous—ZZT is seriously risky [maji de yabai], so postponing it is the right choice. (Nichanneru 2016a)

Anonymous—When you think about the earthquake, I believe you shouldn't sell the game. (Nichanneru 2016a)

More provocative still is the post from an anonymous user on a separate thread titled “Fear over Zettai Zetsumei Toshi Being Cancelled Again” (“Zettai Zetsumei Toshi Futatabi Hatsubai Chūshi no Osore”) made one day after the April 14 foreshock in Kumamoto. It expressly equates the game with an attack on the nation:

Anonymous—With this sort of thing, if you release the game it's as if you're against the Japanese people [Nihonjin o teki ni mawasu, lit. making enemies of the Japanese people]. (Nichanneru 2016b)

What this debate over the continuation or cancellation of the Disaster Report series evidences is that while it is all fun and games (quite literally) to depict a massive earthquake in a virtual space for entertainment purposes, the implication is that the medium or genre itself must somehow be already imbued with gravitas in order to depict trauma. Otherwise, the representation can be perceived as immoral in the senses of trivializing the seriousness of the event or profiting from the pain of real-world victims. Just as some players might learn real-world survival skills from the game, others could find the content insensitive and off-putting.

Whether Disaster Report then ultimately has a positive or negative impact on players illuminates just how complex and personal representational issues in video games can be. Still, a productive element of this debate is that designers, players, and scholars all willingly enter into dialogue around this issue of imaginative play. If photographer Arai Takashi worries about nuclear catastrophes like Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and Fukushima receding from memory, then the productive tensions exposed in these online debates ensure that the events will remain in focus so long as there are artistic representations made about them.

Living Photographs and Virtual Memories at Game's End

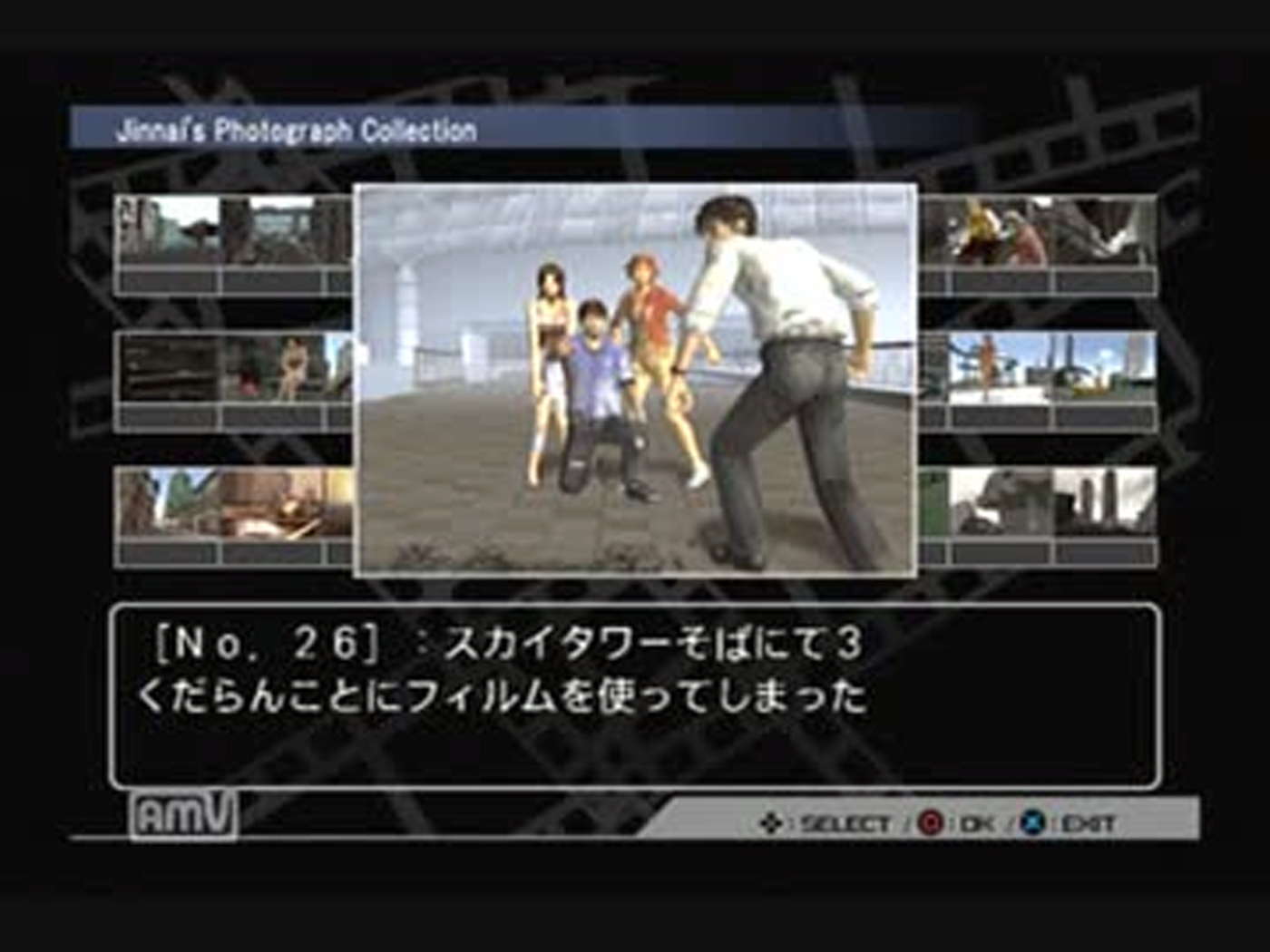

In fleeing Capital City, players strive to make sense of their surroundings, anticipate various outcomes, plan their escape, and problem solve along the way. After players complete a first playthrough of Disaster Report, a new submenu is made available from the start screen. Players now have access to the photos journalist Jinnai Kōji took throughout the narrative up until the point of his death. Unbeknownst to the player, Jinnai was snapping photographs, and these digital stills now function as a photographic tour of the disaster experience from a different character's point of view. There are thirty photographs to view in total, though some can only be unlocked if the game is replayed and different narrative selections are made (see figure 5).

Figure 5. Jinnai Kōji's photograph collection can be viewed once the game is completed. Here, photograph number twenty-six captures Jinnai (foreground) with Masayuki, Mari, and Natsumi in the background next to the Capital City Tower. Jinnai laments wasting film on this silly shot. © Granzella Inc.

At first glance, Jinnai's photographs appear to mimic the souvenirs and postcards featuring imagery that became an integral part of “disaster tourism” after the Great Kantō Earthquake. Just as residents from unaffected areas traveled to Tokyo to view the spectacle of destruction (Weisenfeld Reference Weisenfeld2012, 72, 74), so too do many of these in-game photographs turn their eye to the ruins of Capital City. Photograph number twenty-two is taken from the top of an elevated walkway. The caption reads: “This was an elevated walkway located above a road now replaced by a river of water.” Another photograph, number twenty-three, shows a ruined and evacuated residential district with the caption: “Once a residential area, even damaged, the beauty of the sunset still remains untouched.” Photograph number twenty-eight, taken during the group's escape from May Stadium, reiterates the importance of fresh water and hygiene in the aftermath of a catastrophe. The caption here reads: “Clean drinking water is rare and valuable when disasters like this occur.”

Susan Sontag (Reference Sontag2003, 10) writes that “all photographs wait to be explained or falsified by their captions.” The captions above validate the photographic representations within Disaster Report for their accuracy and emotional weight. They are somber snapshots of destruction and loss that approximate the real-world pictures featured in Anne Nishimura Morse's and Anne E. Havinga's photobook In the Wake: Japanese Photographers Respond to 3/11. For Hayashi (Reference Hayashi, Morse and Havinga2015, 177), the power of 3.11 photography is that it “distinctively inscribes traces of individual situations and actions.” In Disaster Report, this process moves one step further as players inscribe their own actions on the in-game photographs, making it more difficult to subsume these images into a generalized account of natural disaster trauma. The scopophilic pleasure of looking at disaster ruins gives way to the production of empathy as players flip through this photo album now intrinsically linked to their own gameplay experience. These in-game photographs represent a liminal space—players are both present in the pictures, via their avatars, and not. Players both shaped the content in the photographs and also had it scripted for them by a team of game designers.

Certainly, the gameic images under discussion here are simulated and simplified. Yet, my observation resonates with what memory studies scholar Alison Landsberg (Reference Landsberg2004) terms “prosthetic memories,” or implanted memories unrelated to one's lived experience. In her analysis of the famous science fiction films Blade Runner and Total Recall, Landsberg shows how these prosthetic memories, in spite of their artificiality, “feel real and are used productively by the people who wear them” (45). They in fact organize and energize the bodies and subjectivities that take them on. For these reasons, playing through a simulation like Disaster Report might prompt virtual memories and virtual meaning-making just real enough to help the shaking within the game be felt by those outside of it. Landsberg's prosthetic memories highlight these messy interconnections between technology and individual memory. They build on Marianne Hirsch's (Reference Hirsch2012) landmark study of “postmemory” and reinforce one of Jeffrey C. Alexander's (Reference Alexander, Alexander, Eyerman, Giesen, Smelser and Sztompka2004, 9) central assertions from his theory of “cultural trauma” that “imagination informs trauma construction just as much when the reference is to something that has actually occurred as to something that has not.”

It is precisely this capacity of video games to endow imaginary objects with life that represents one of the great advantages of the medium according to Janet Murray (Reference Murray1997, 112) in her foundational text Hamlet on the Holodeck. If mass-scale disasters represented in newspaper photos and YouTube videos represent collective narratives that run the risk of flattening the individual victims and individual narratives therein, then video games offer players the potential to rebuild some of this context by hearing lost voices, inhabiting lost bodies, and experiencing lost narratives, if only in virtual space.

Acknowledgments

I would like to acknowledge the help and support of Millie Creighton, David Edgington, and Franz K. Prichard, all of whom suggested scholarship to strengthen this article. I would also like to thank the anonymous reviewers for pushing my writing and argument to a point of further clarity and for offering valuable feedback about how to better integrate the video game analysis with Asian studies scholarship. Finally, I would like to extend my gratitude to discussant Hyung-Gu Lynn and the presenters at the Association for Asian Studies annual conference who kindly listened to and provided feedback on a presented version of this article.