The timing and mechanisms of the development of today’s treeless landscapes in the North Atlantic islands have important implications for establishing the nature of human–woodland interaction in landscapes of settlement (Dugmore et al. Reference Dugmore, Church, Buckland, Edwards, Lawson, McGovern, Panagiotakopulu, Simpson, Skidmore and Sveinbjarnardóttir2005; Church et al. Reference Church, Dugmore, Mairs, Millard, Cook, Sveinbjarnardóttir, Ascough, Newton and Roucoux2007a). Understanding the history of deforestation also helps us to understand past and present-day trajectories of environmental change, and to set conservation priorities and carbon management strategies (Bennett et al. Reference Bennett, Bunting and Fossitt1997; Lawson et al. Reference Lawson, Church, McGovern, Arge, Woollett, Edwards, Gathorne-Hardy, Dugmore, Cook, Mairs, Thomson and Sveinbjarnardόttir2005; SNH 2014). Deforestation had profound long-term effects for farming communities in the North Atlantic region, ultimately reducing the area of land suitable for agriculture through soil erosion or the spread of blanket bog, and creating challenges for fuel and timber procurement strategies. It is often suggested that the introduction of agriculture by the first farming groups in the Neolithic period (c. 3800–3600 cal bc) in the Western Isles, Orkney and Shetland, and later (9th–11th centuries cal ad) by Norse settlers in the Faroes, Iceland, and Greenland, led swiftly to widespread deforestation (eg, McGovern et al. Reference McGovern, Bigelow, Amorosi and Russell1988; Bennett et al. Reference Bennett, Bunting and Fossitt1997; Dickson Reference Dickson2000; Diamond Reference Diamond2005; Dugmore et al. Reference Dugmore, Church, Buckland, Edwards, Lawson, McGovern, Panagiotakopulu, Simpson, Skidmore and Sveinbjarnardóttir2005). However, palynological evidence from many parts of the region suggests that woodland decline was often more protracted, with woodlands surviving in some locations for many centuries or millennia (Edwards et al. Reference Edwards, Mulder, Lomax, Whittington and Hirons2000; Church et al. Reference Church, Dugmore, Mairs, Millard, Cook, Sveinbjarnardóttir, Ascough, Newton and Roucoux2007a; Lawson et al. Reference Lawson, Gathorne-Hardy, Church, Newton, Edwards and Dugmore2007b; Schofield & Edwards Reference Schofield and Edwards2011; Farrell et al. Reference Farrell, Bunting, Lee and Thomas2014).

The Western Isles (also known as the Outer Hebrides) represent a key island group for examining the nature of the earliest farmers’ interactions with woodlands in the North Atlantic region. As the southernmost archipelago of the North Atlantic Islands, the Western Isles are positioned at one end of an environmental gradient extending from the temperate conditions in Atlantic Scotland to the arctic conditions of Greenland, and they were amongst the earliest islands of the region to have been settled by farmers. Contrary to modern perceptions of the marginality of the Western Isles, they preserve one of the largest and best-preserved concentrations of Neolithic and Bronze Age monuments and agricultural features in north-west Europe. At Calanais on Lewis these features include stone circles, stone alignments, standing stones and chambered cairns, cultivation beds, stone field boundaries, palaeosols, and clearance cairns (Cowie Reference Cowie1994; Ashmore Reference Ashmore1995; Reference Ashmore2016; Coles et al. Reference Coles, Church, Harding and Inglis1998; Johnson et al. Reference Johnson, Flitcroft and Coles2000). The most impressive of the surviving monuments is Calanais I, a large stone circle with cruciform stone alignments, where the major phase of construction and use was in the late Neolithic–Bronze Age (c. 3000–1700 cal bc: Ashmore Reference Ashmore1995; Reference Ashmore2016). Survey and excavation within the wider Calanais landscape have also revealed settlement evidence ranging from prehistoric hut circles to post-medieval ‘blackhouses’ (Coles Reference Coles1993a; Reference Coles1993b; Coles & Burgess Reference Coles and Burgess1994). The encroachment of peat over these sites has reduced modern interference, aiding preservation, and, fortuitously, providing material suitable for palaeoenvironmental sampling. The richness of the evidence base therefore supports detailed research into the history of human-environment interactions.

Though the present landscapes of the Western Isles are open and virtually tree-less, palaeoenvironmental evidence suggests that during the Mesolithic period (c. 9600–4000 cal bc) the islands supported substantial birch-hazel woodlands (Bennett et al. Reference Bennett, Bunting and Fossitt1997; Church Reference Church2006). The chronology and causes of the deforestation have been much debated, with palynological evidence suggesting that both the initial woodland coverage and subsequent woodland decline were spatially and temporally variable (Brayshay & Edwards Reference Brayshay and Edwards1996; Fossitt Reference Fossitt1996; Edwards et al. Reference Edwards, Mulder, Lomax, Whittington and Hirons2000; Fyfe et al. Reference Fyfe, Twiddle, Sugita, Gaillard, Barratt, Caseldine, Dodson, Edwards, Farrell, Froyd, Grant, Huckerby, Innes, Shaw and Waller2013). It has also been suggested that there was a degree of economic continuity between Mesolithic and Neolithic lifestyles in the region (Armit & Finlayson Reference Armit and Finlayson1992, 67; Thomas Reference Thomas1999, 7–17; Reference Thomas2013, 402) and hence woodland impacts (eg, Edwards Reference Edwards1996). Therefore, the extent to which Neolithic communities in the Western Isles were responsible for the woodland decline remains uncertain.

This paper presents new archaeological and palaeoenvironmental data from Aird Calanais, a site within the Calanais landscape that spans the period of use of the Calanais stones. We consider the timing, causes and significance of deforestation both locally (Aird Calanais) and regionally (Western Isles and beyond), starting with the new evidence from Aird Calanais, and then developing a new synthesis of plant macrofossil and pollen evidence from the Western Isles and a review of comparable data from the wider North Atlantic region. The following research questions are addressed:

1. How and when was the archaeological material at Aird Calanais formed?

2. What were the timing, nature and mechanisms of deforestation in the Calanais landscape?

3. What does the regional plant macrofossil and pollen evidence reveal about the timing, extent, and mechanisms for woodland decline in the Western Isles?

4. What implications does the evidence from the Western Isles have for understanding the interactions between first farmers and woodlands in the North Atlantic region?

METHODOLOGY

Field methods

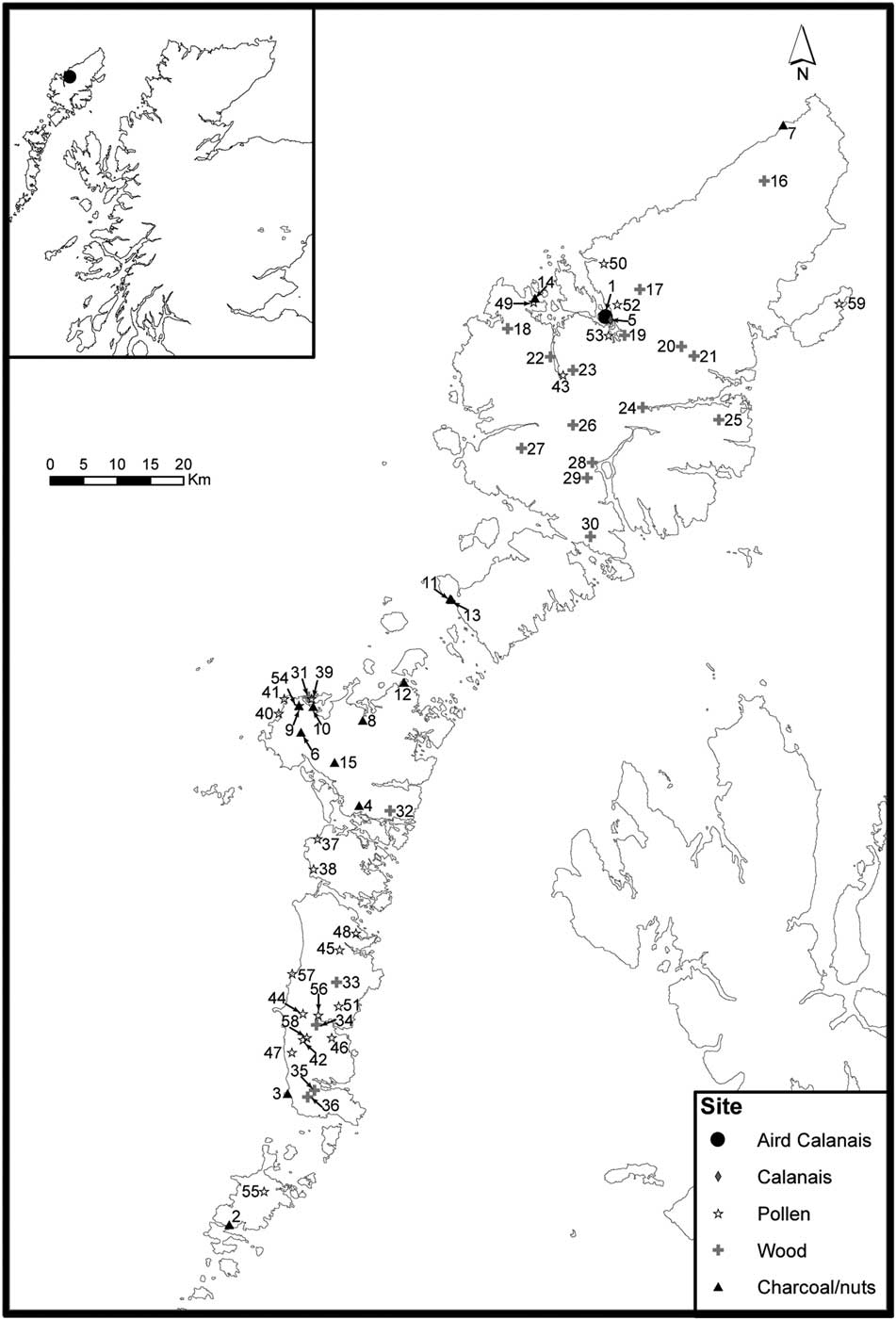

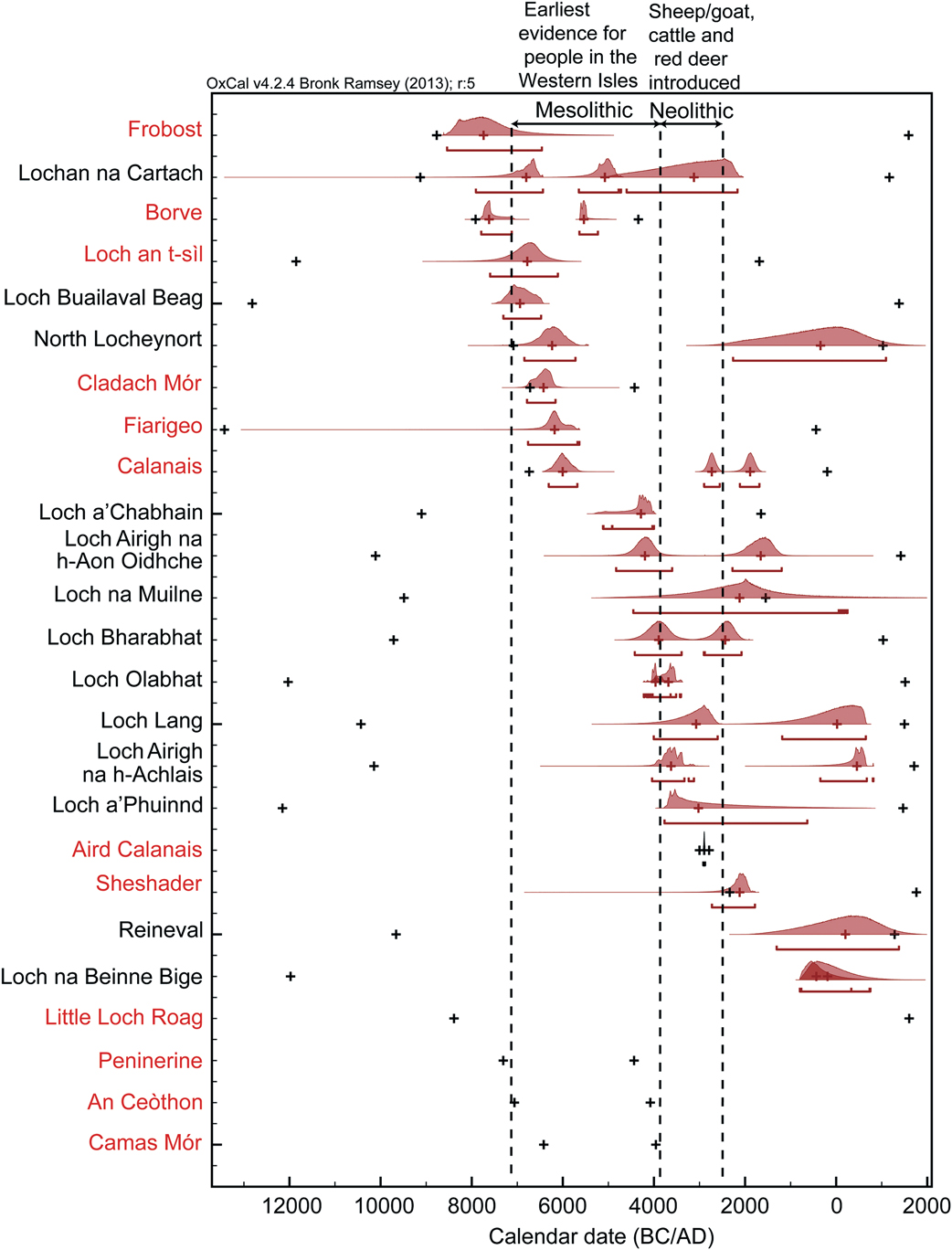

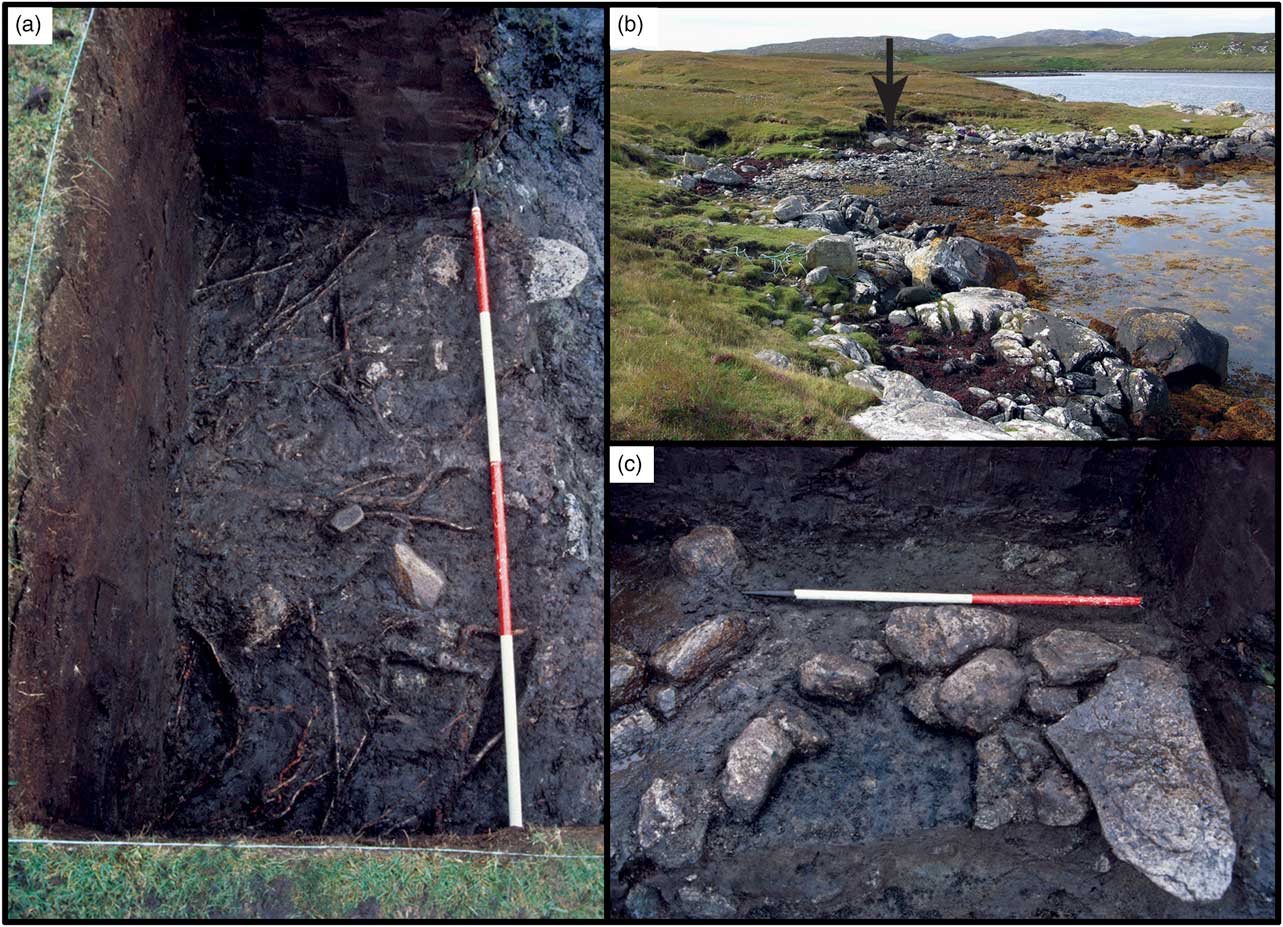

In 1997, Mr Simon Fraser of Calanais village discovered a possible anthropogenic feature within a coastal peat bank on the edge of East Loch Roag, at Aird Calanais, less than 1 km from the main Calanais I monument (NGR: NB 206 335; Figs 1–3). The site comprised a charcoal lens enclosed by a semi-circular stone alignment, which was overlain by an extensive wood layer. These features were buried under approximately 1.1 m of peat and lay directly above a palaeosol.

Fig. 1 Location of the Western Isles & Aird Calanais, showing the position of the excavation trench in relation to East Loch Roag, the main stone circle site at Calanais I, & the Calanais-3 pollen sampling site

Fig. 3 (a) The late Neolithic wood layer [3], after the removal of the layer of peat containing occasional twigs [4], from the south; (b) The landscape setting of Aird Calanais in relation to East Loch Roag, from the west. The arrow shows the location of the excavation; (c) the early Neolithic hearth [11], from the south

The eroding section was cleaned, drawn and photographed prior to excavation, following standard archaeological excavation procedures (Fig. 4). The semi-circular stone alignment extended approximately 0.9 × 0.6 m into the section. A 2 × 1 m trench was excavated to allow a thorough investigation of this feature. The wood layer, associated contexts and the charcoal fill of the semi-circular stone alignment were collected in their entirety (100% sampling: Jones Reference Jones1991), and bulk samples were taken from the remaining contexts (total sampling: Jones Reference Jones1991). A column sample was taken approximately 30 cm back from the main trench and was stored at 4°C prior to laboratory sub-sampling.

Fig. 4 Excavation drawings from Aird Calanais: (a) north-facing section, showing column sample location (C1); (b) north-facing section through archaeological features; (c) plan of the late Neolithic hearth prior to excavation, showing position of sections AB [(b)] & CD [(a)]

Laboratory methods

A summary of the methodologies employed is provided below. For a full description please see Appendix S1 online.

The stratigraphy and soil colour of the column sample were described (Munsell Color 1975; Rural Development Service 2006), and loss-on-ignition was measured on contiguous 1 cm3 sub-samples at 550°C for 4 hours (Heiri et al. Reference Heiri, Lotter and Lemcke2001). The volume-specific magnetic susceptibility (κ) of air-dried and sieved (2 mm) sediment was measured using a Bartington MS2G Single Frequency Sensor (Dearing Reference Dearing1994; Bartington Instruments Ltd nd). Following Kenward et al. (Reference Kenward, Hall and Jones1980), 200 ml sub-samples from archaeological contexts 3, 5, and 8 were wet-processed using four sieves (1 mm to 125 μm) to extract uncarbonised palaeo-environmental material. The remaining bulk samples were then processed in the Environmental Archaeology laboratories of Durham University, following Uig Landscape Project archaeobotanical protocols (see Nesbitt et al. Reference Nesbitt, Church and Gilmour2011, 38–40), using microscopy up to ×600 magnification.

Pollen samples from the column sample were taken from the main stratigraphic phases of the site to assess whether there was a woodland decline contemporary with the archaeological site. The samples were prepared following standard techniques (Moore et al. Reference Moore, Webb and Collinson1991) and coprophilous fungal spores were also recorded (van Geel et al. Reference van Geel, Buurman, Brinkkemper, Schelvis, Aptroot, van Reenen and Hakbijl2003). Samples were counted to a minimum of 300 TLP and a maximum of 326 TLP (total land pollen: Rull Reference Rull1987) at ×400 or ×1000 magnification. Pollen grain damage was recorded following Wilmshurst and McGlone (Reference Wilmshurst and McGlone2005).

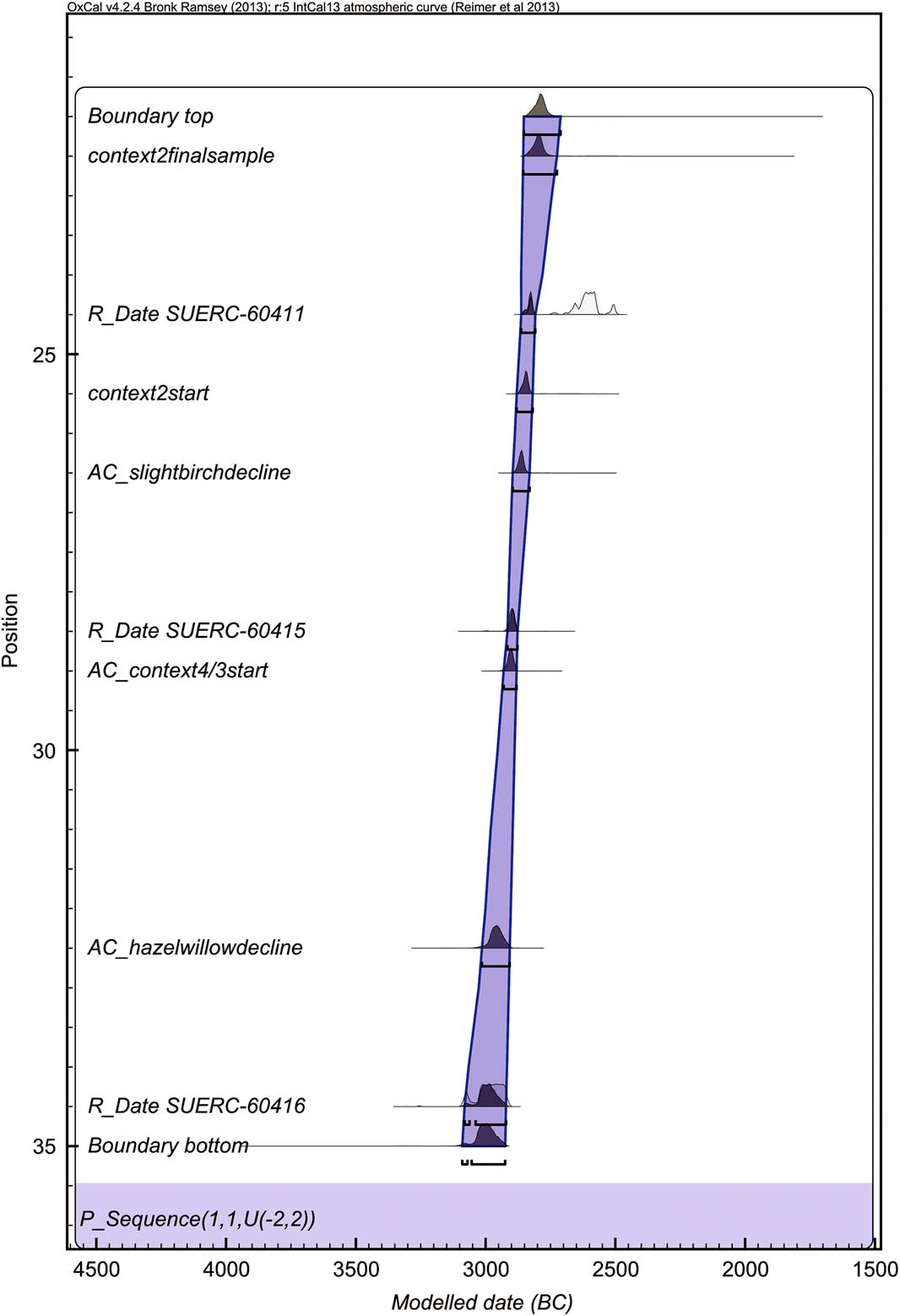

Two single-entity plant macrofossils from key archaeological contexts and three 1 cm3 bulk peat samples from the column sample were submitted for AMS radiocarbon dating at the Scottish Universities Environmental Research Centre (Table 1). Dates were calibrated and a Bayesian ‘P_Sequence’ age-depth model created for the pollen sequence using IntCal13 (Reimer et al. Reference Reimer, Bard, Bayliss, Beck, Blackwell, Bronk Ramsey, Grootes, Guilderson, Haflidason, Hajdas, HattŽ, Heaton, Hoffmann, Hogg, Hughen, Kaiser, Kromer, Manning, Niu, Reimer, Richards, Scott, Southon, Staff, Turney and Plicht2013) in OxCal v 4.2.4 (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2009; see below). Due to the mixed nature of the earliest organic soil horizon (archaeological context [6]; see below), the base of the peat (archaeological context [5]) was used as the lowest boundary in this model.

Table 1 radiocarbon dates from aird calanais

Combined and calibrated using Oxcal v.4.2.4 (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2009) using Intcal13 (Reimer et al. Reference Reimer, Bard, Bayliss, Beck, Blackwell, Bronk Ramsey, Grootes, Guilderson, Haflidason, Hajdas, HattŽ, Heaton, Hoffmann, Hogg, Hughen, Kaiser, Kromer, Manning, Niu, Reimer, Richards, Scott, Southon, Staff, Turney and Plicht2013). The calibrated radiocarbon dates produced using the Oxcal p-sequence age-depth model for the column sample are asterisked (*) and shown in brackets after the unmodelled ranges

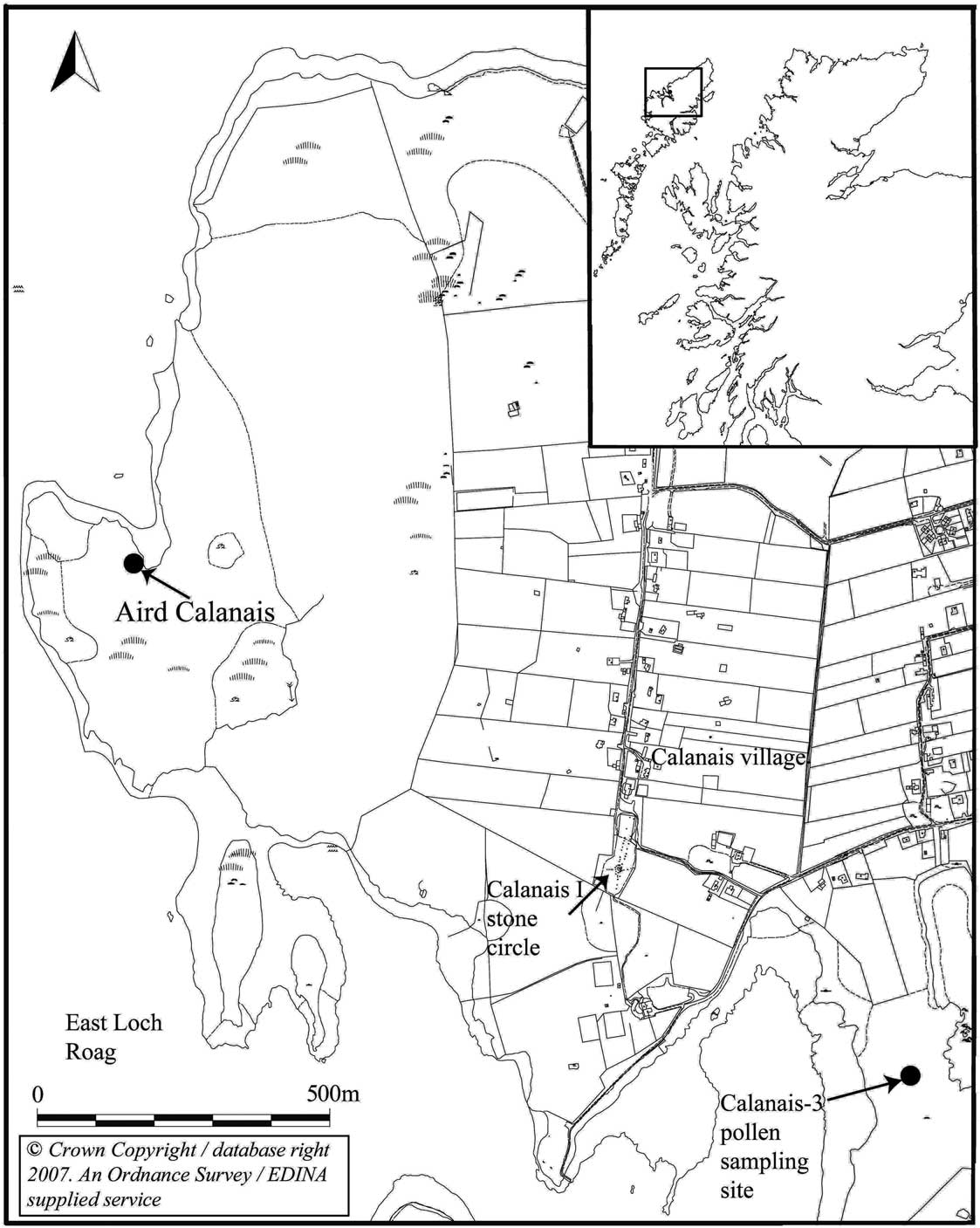

Synthesis of plant macrofossil data

A database of charred remains from trees and shrubs (charcoal, seeds, fruits, nuts) from Neolithic sites in the Western Isles was compiled by searching through relevant literature, with unpublished reports also obtained from relevant individuals. Radiocarbon-dated wood layers within peat sequences were synthesised from Bohncke (Reference Bohncke1988), Fossitt (Reference Fossitt1996), Rees and Church (Reference Rees and Church2000), and Wilkins (Reference Wilkins1984).

Synthesis of palynological data

Palynological evidence from the Western Isles was collated from existing reviews (Church Reference Church2006; Edwards et al. Reference Edwards, Mulder, Lomax, Whittington and Hirons2000) and more recent published sources (see Table 4). Records with significant hiatuses, no data after 6000 cal bc, or fewer than two reliable radiocarbon dates were excluded. A total of 24 records remained for analysis.

A standardised method was used to identity the timing and amplitude of the decline in tree pollen in the different records and to estimate the date of each woodland decline (for full details see Appendix S1). Following Bronk Ramsey (Reference Bronk Ramsey2008) and Blockley et al. (Reference Blockley, Bronk Ramsey, Lane and Lotter2008) and using OxCal v4.2.4 (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2009), new Bayesian P_sequence age-depth models were created for each sequence. The calibrated ages of the identified woodland declines were estimated by incorporating the depths of these points within the models. Asterisks (*) are used throughout this paper to indicate interpolated rather than raw radiocarbon determinations.

RESEARCH QUESTION 1: HOW & WHEN WAS THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL MATERIAL AT AIRD CALANAIS FORMED?

Five major stratigraphic phases were identified at Aird Calanais (Table 2; Fig. 4). A summary of the results and discussion of the main phases of the site excavation (Phases 2–4) is provided below, with a full description provided in Appendix S2.

Table 2 summary of the contexts, phases & dates of the excavated horizons at aird calanais

Asterisks (*) are used to indicate interpolated rather than raw radiocarbon determinations

Phase 1: the earliest natural horizons

These comprise a green-grey boulder clay [12], overlain by a brown sandy-silt containing sand and gravel lenses [13].

Phase 2: (the late Mesolithic palaeosol)

This is the earliest organic soil horizon at the site: a very dark-grey clayey-silt containing occasional charcoal flecks [6]. The pollen from this layer (Figs 5 & 6) was poorly preserved, was relatively poor in arboreal pollen (birch: Betula sp., hazel-type: Corylus-type) and rich in Heather (Calluna vulgaris (L.) Hull), meadowsweets (Filipendula sp.), and fern spores that are typical in early Holocene lake sediment records from the Western Isles (eg, Fossitt Reference Fossitt1996). Though the pollen preservation in the uppermost sample from this context was sufficient for vegetation reconstruction, owing to the poor preservation, the pollen data from the three lowest samples are probably not a reliable guide to the palaeovegetation. However, the poor preservation itself is consistent with the interpretation of this context as a palaeosol.

Fig. 5 Sedimentological & selected palynological data for the column sample from Aird Calanais. Magnetic susceptibility was recorded as volume-specific κ. The percentages were calculated as a percentage of total land pollen (TLP). A dot indicates the presence of a taxon at less than 1%. The lowermost three pollen samples are drawn with dashed lines as they are considered to be separate from the main stratigraphic sequence & were very poorly preserved; see text for details. Rare taxa not shown on this diagram are listed in Table S1 (Criteria: taxa not shown in the diagram are only present in 1–3 samples & always at <2%. Sorbus also meets these criteria but remains in the diagram because it is pertinent to the discussion of deforestation). Indet.: Indeterminate pollen (includes degraded/crumpled/concealed & corroded pollen); t.: type

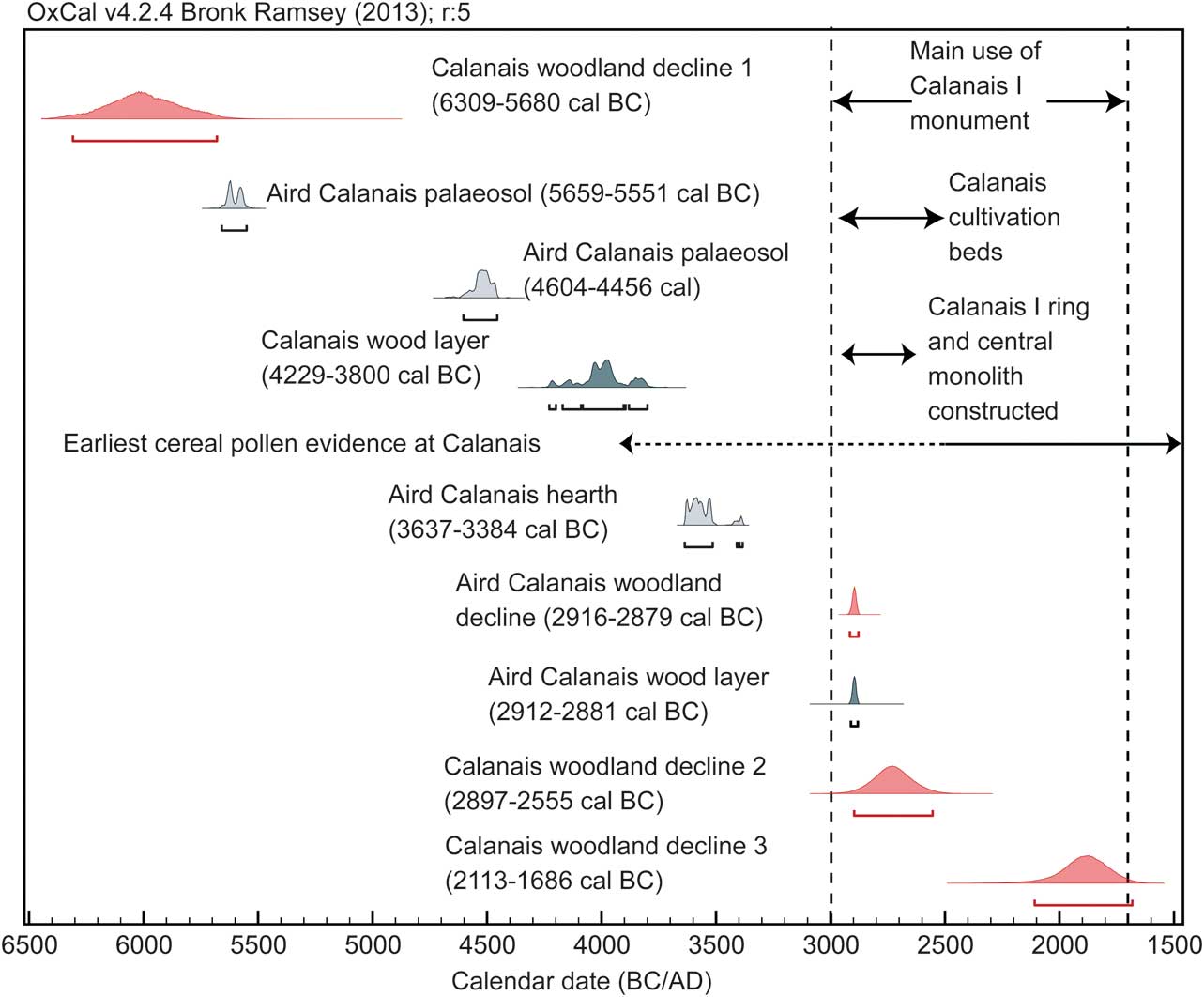

Fig. 6 Oxcal P_sequence model for the radiocarbon dates from the Aird Calanais column sample, showing the modelled dates for the key features of the pollen curve. The dates were modelled within OxCal v 4.2.4 (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2009) using IntCal13 (Reimer et al. Reference Reimer, Bard, Bayliss, Beck, Blackwell, Bronk Ramsey, Grootes, Guilderson, Haflidason, Hajdas, HattŽ, Heaton, Hoffmann, Hogg, Hughen, Kaiser, Kromer, Manning, Niu, Reimer, Richards, Scott, Southon, Staff, Turney and Plicht2013)

The bulk sample contained just three carbonised hazel (Corylus avellana L.) nutshell fragments and 28 charcoal fragments, which were predominantly willow/poplar (Salicaceae: most likely willow, which is present in the pollen samples), together with some birch (Table 3). Two of the carbonised hazel nutshell fragments produced late Mesolithic dates (5659–5551 cal bc and 4604–4456 cal bc; see Table 1). These single entity dates from short-lived material date precisely the year in which the hazelnuts grew. The large interval between them suggests that this soil developed over a long duration.

Table 3 environmental remains from the aird calanais bulk and wet-processed samples

F: fragment; nt: nutshell fragment; n: nutlet; a: achene; c: caryopsis; s: seed; fs: fungal sclerotia; rw: roundwood; rt: rootwood; t: timber; (not p to b): not pith to bark; (p to b): pith to bark. Numbers refer to total counts and letters (a=e) to relative abundance on a scale from a (lowest) to e (highest). Remains from the wet-processed samples are shown as total counts/200 ml or relative abundance/200 ml. *: counts estimated using a sub-sample

The arboreal pollen percentages in the uppermost sample from this context are consistent with the possibility that the charcoal and hazelnuts originated in the woodlands around the site (in Scottish peats arboreal pollen typically represents vegetation within c. 300 m of the site: cf. Bunting Reference Bunting2002; cf. Waller et al. Reference Waller, Binney, Bunting and Armitage2005). It is unclear whether they were deposited as a result of human agency or natural processes: no artefacts or archaeological features were found, and it is possible that the nutshell and charcoal were charred in wildfires (cf. Tipping Reference Tipping1996; Reference Tipping2004). However, considering the relatively wet climate in the Western Isles and the rarity of wild fires today, human-made fires are a more convincing explanation for the origin of the charred plant remains (Moore Reference Moore1996; Ashmore Reference Ashmore2016, 982). The charcoal may be fuel waste and the nutshell may have been discarded onto a fire after the kernels had been consumed (Bishop et al. Reference Bishop, Church and Rowley-Conwy2014). The horizon may therefore represent one of the very few archaeological sites of Mesolithic date known in the Western Isles (cf. Gregory et al. Reference Gregory, Murphy, Church, Edwards, Guttmann and Simpson2005; Simpson et al. Reference Simpson, Murphy and Gregory2006; see Table 5). The burnt remains were probably mixed within the palaeosol by bioturbation, because no discrete burning lenses were identified.

Phase 3: early Neolithic contexts

Phase 3 represents a coherent, semi-circular stone hearth structure [7] and associated layers [10, 11, 8], which directly overlay the palaeosol [6] (Figs 3 & 4). The abrupt demarcation between the late Mesolithic palaeosol and the hearth suggests that the early Neolithic soils were eroded in this location. The semi-circular structure was constructed of medium-sized angular stones (see Fig. 3c), and although approximately half of it had been eroded prior to excavation, it clearly resembled a hearth. The hearth was filled by a well-preserved charcoal layer [10] – the lower hearth fill – which was dominated by willow/poplar charcoal (>50% of the assemblage), together with birch (30%) and hazel (10–20%) charcoal. Radiocarbon-dated birch leaf buds date the deposit to 3637–3384 cal bc.

Three factors suggest that the hearth represents a single period of use. First, there was no stratigraphic break within the charcoal deposit, suggesting a single burning episode. Secondly, the hearth was of rough construction and could have been made rapidly using stone gathered from the immediate vicinity. There was no evidence of hearth slabs or cutting to create a stable surface for repeated use. This is very different to the multiple-use hearths on Neolithic domestic sites in Atlantic Scotland, which are normally carefully constructed using large stone slabs (eg, Scott Reference Scott1950; Ritchie Reference Ritchie1983; Crone Reference Crone1993a; Branigan & Foster Reference Branigan and Foster1995; Mills et al. Reference Mills, Armit, Edwards, Grinter and Mulder2004; Thomas & Lee Reference Thomas and Lee2012). Thirdly, edible plant remains and turf/peat fuel remnants (eg, carbonised seeds from heathy plants) which are usually recovered from Neolithic settlements in the region (Church et al. Reference Church, Peters and Batt2007b; Bishop et al. Reference Bishop, Church and Rowley-Conwy2009) were absent. Instead, native deciduous branches and timber were used as fuel in the hearth. Therefore, the hearth appears to have been a single-use fire, deriving from the opportunistic gathering of wood from the local environment.

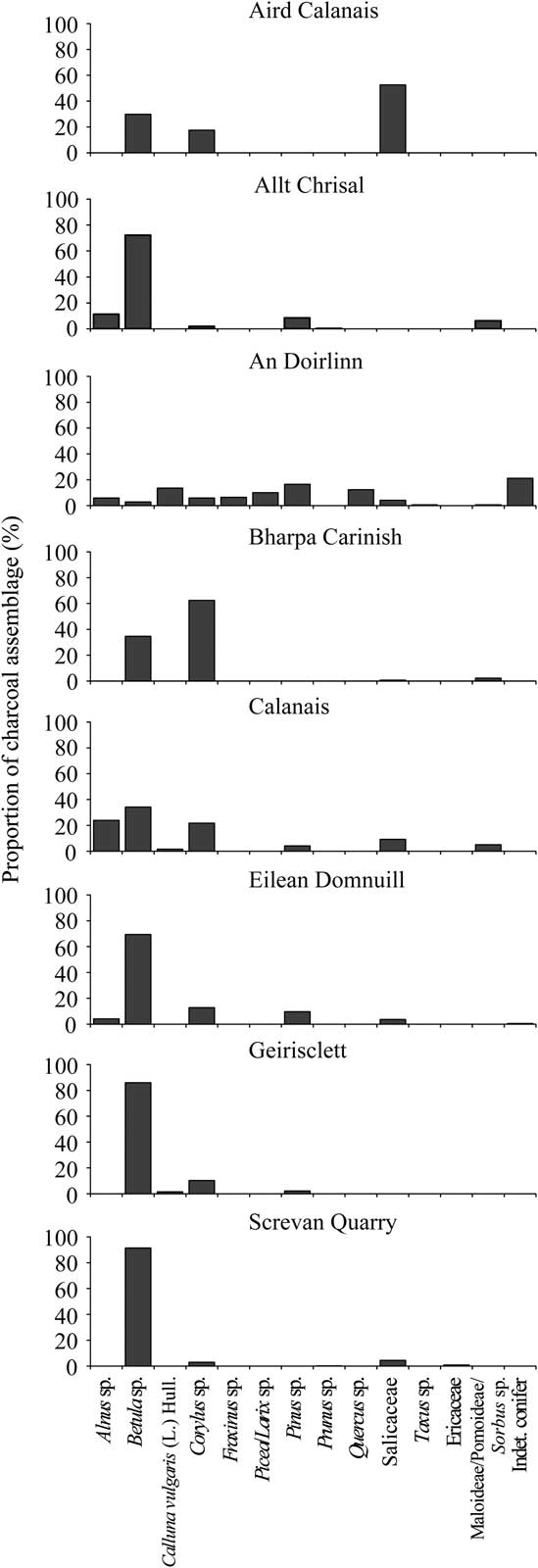

The willow-dominated firewood collected and burnt at Aird Calanais differs from the general fuel procurement strategy across the Western Isles, which is predominantly birch or hazel firewood (see Table 5; Fig. 7). This probably reflects its unusual nature as a single-use hearth relating to a specific activity, whereas the other assemblages are from settlements or monuments, so derive from longer-term use and a greater range of activities. Unfortunately, the fragmented nature of the charcoal assemblage (only six fragments had complete transverse sections from pith to bark) precludes a more detailed examination of the wood selection (eg, diameter selection) or woodland management strategies (eg, coppicing: cf. Out et al. Reference Out, Vermeeren and Hänninen2013) that may have been occurring at Aird Calanais.

Fig. 7 Summary of the main species present in Neolithic charcoal assemblages in the Western Isles. The proportion of each taxa was calculated for each assemblage with fragment counts & masses (see Table 6), as the overall percentages based on both methods are approximately equal (Chabal Reference Chabal1990; Miller Reference Miller1985, 4)

The stone layer [11] and upper hearth fill [8] may represent deliberate anthropogenic deposits, perhaps to cover the fire at the end of its use. The sedimentology and archaeobotanical species composition of the upper hearth fill [8] (Table 3) were similar to those of the late Mesolithic palaeosol [6], and the charcoal fragments were abraded, perhaps due to redeposition. This suggests that the upper hearth fill may have been deliberately extracted from the palaeosol to dampen down the fire at the end of its use.

Phase 4: late Neolithic contexts

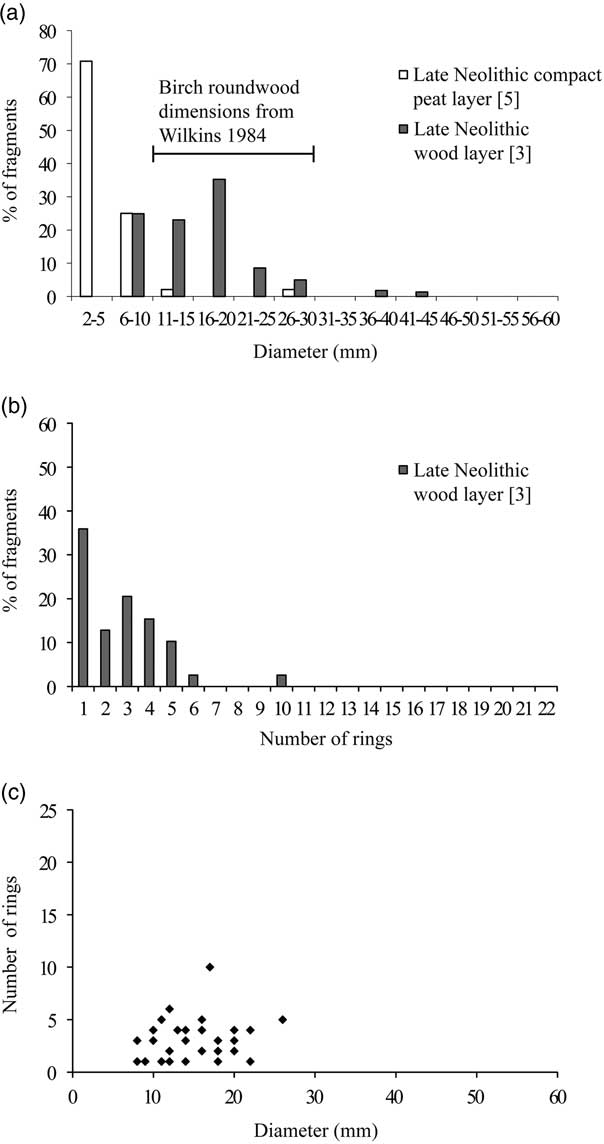

Phase 4 is interpreted as the remains of a phase of major woodland decline. Immediately above the hearth was a layer of compact clay-rich peat containing occasional wood fragments [5], overlain by a distinct layer of intact twigs and bark [3] (Fig. 3a). Both the wood layer [3] and compact peat [5] contained birch roundwood (Table 3), which was of a small diameter (2–44 mm) and young age (1–10 years; Fig. 8). The combined date of two 1-year old birch twigs from the wood layer [3] was 2912–2881 cal bc (late Neolithic).

Fig. 8 Age and diameter of wood remains from Aird Calanais: (a) birch roundwood (pith to bark) diameters from contexts 3 & 5. A bar has been placed on the chart to indicate the main range of the birch diameters in the wood layers recorded by Wilkins (Reference Wilkins1984); (b) birch roundwood (pith to bark) ring counts from the late Neolithic wood layer (context 3); (c) scatter plot of birch roundwood (pith to bark) ring counts & diameters from the late Neolithic wood layer (context 3). The categories & scales for the graphs are the same as used in Out et al. (Reference Out, Vermeeren and Hänninen2013), to allow ease of comparison with their age/diameter models for woodland management. Some of the rings of the measured wood fragments could not be counted due to poor preservation, & consequently these fragments are shown on graph (a), but not on graph (c)

The late Neolithic wood layer [3] covered most of the trench, with the exception of the eastern side of the eroded edge of section A–B, and extended into the trench edges (Figs 3 & 4). The abundance of the wood varied across the excavated horizon, from dense concentrations to more sparsely scattered twigs. The wood layer [3] was overlain by a thin layer of peat containing occasional twigs [4]. Throughout most of the trench, [3] and [4] were visible as distinct layers, but where [3] was relatively thin, for example in the column sample, the boundary between these contexts was indistinct and they were recorded as [4/3].

Two factors suggest that the wood layer [3] was formed during the main period of woodland decline at the site. First, [3] extended beyond the excavated area and appears to have been composed entirely of birch, which the pollen evidence from the column shows was the main taxa in the woodland surrounding the site at the time the wood layer formed (Fig. 5). At the base of the late Neolithic wood layer (*2916–2878 cal bc), birch was as high as 73%, with smaller quantities of hazel-type (Corylus-type), willow (Salix sp.), and other tree/shrub taxa also present, and heather moderately abundant. Secondly, the wood layer was contemporary with a decline in birch in the on-site pollen record, which suggests that the extent of birch woodland was reduced after the wood layer had been deposited. Arboreal pollen declined rapidly in the late Neolithic from 78% at the base of the late Neolithic wood layer ([4/3], phase 4: *2931–2881 cal bc) to 16% at the base of the hagged peat ([2], phase 5: *2863–2809 cal bc), and finally to 5% at the top of the analysed pollen sequence (*2856–2726 cal bc) (Fig. 5).

Several factors suggest that the layer was not an anthropogenic deposit of wood. The wood was preserved in wet conditions and there was no evidence for burning. The absence of timber fragments (Table 3) or shaped or cut roundwood (cf. Boyd Reference Boyd1988, 613) and the lack of coherent structural arrangement of the wood, together with the lack of artefacts or archaeological features shows that this layer did not form part of a structure, such as a collapsed roof, floor, or trackway. Thus, the horizon appears to contain a natural accumulation of wood that was fortuitously preserved in waterlogged conditions.

The similarity of the layer to other peat deposits containing birch remains on Lewis (Wilkins Reference Wilkins1984) supports this conclusion. Wilkins (ibid., 254) notes that the birch branches,‘were usually found in a horizontal layer near the bottom of the peat … The material gave a distinct impression of fallen branches which had become buried rather than roots in situ in the peat … In some cases the layer was very dense and the most recent episode of peat cutting had exposed an extensive platform of tangled wood’.

Wilkins observed no stumps of birch. The absence of birch stumps in Lewisian peats suggests that peat formation was not directly responsible for the death of the birch trees at these sites, but rather, birch branches from trees growing close to the peat were deposited and subsequently preserved within it. Pine (Pinus sp.), by contrast, is represented in Neolithic peats on Lewis predominantly by stumps. It appears to have directly colonised the peat, most likely during more favourable drier bog-surface conditions, before being preserved as the bog accumulated (Edvardsson et al. Reference Edvardsson, Linderson, Rundgren and Hammarlund2012).

There is evidence that climatic deterioration played an important role in woodland decline at Aird Calanais. Peat had already begun to accumulate prior to the formation of the wood layer and the preservation of the wood and water fleas (Cladocera; Duigan & Birks Reference Duigan and Birks2000) within this layer indicates the development of areas of standing water, which could have increased the mortality of standing trees and inhibited the recruitment of new tree/shrub seedlings (Wilkins Reference Wilkins1984, 256). A gradual increase in grass (Poaceae) and sedge (Cyperaceae) pollen at the expense of buttercup (Ranunculus sp.), Carrot family (Apiaceae), and ferns, and the macrofossil record of increasing abundance of rush (Juncus sp.) seeds (Table 3), suggests a gradual expansion of wet acid heath and peat. Increased precipitation is documented from other proxy records elsewhere in Northern Scotland for the period c. 3100–2400 cal bc (Tipping & Tisdall Reference Tipping and Tisdall2004, 74–6). As well as potentially killing or preventing the recolonisation of the trees in waterlogged areas, an increase in wetness would have improved conditions for the preservation of birch branches within the peat (Fossitt Reference Fossitt1996, 193).

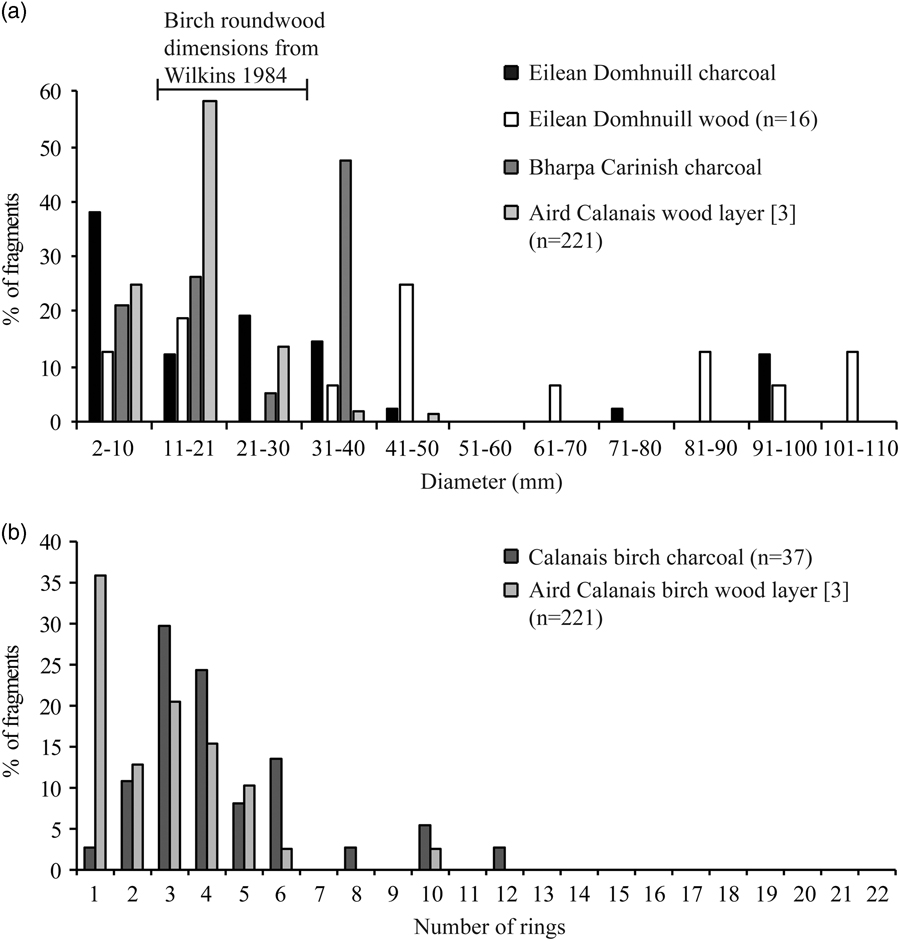

However, it is not possible to exclude the involvement of people in the formation of this deposit at Aird Calanais. First, whilst there was no evidence for cut marks on the branches examined, it is possible that people felled the tree trunks on which the branches grew. Secondly, the ring curvature and age and diameter profiles of the wood from the horizon shows that it is neither the remains of a single birch shrub, nor is it a random selection of birch branches from the local woodland: there were no timber fragments (ie, remains from medium and large diameter branches and trunks) or definite rootwood fragments (Table 3). The branch age and size data was not normally distributed. The size/age ranges of the branches are tightly clustered with no branches over 10 years old or greater than 45 mm in diameter (Fig. 8). The wood remains were primarily less than 2 cm in diameter, so it is not possible to identify if the assemblage was derived from managed woodlands (eg, by coppicing; Out et al. Reference Out, Vermeeren and Hänninen2013). However, the absence of larger (>45 mm diameter) and older branches (>10 years) could suggest that people selectively removed these branches, perhaps for construction purposes, as suggested by the archaeobotanical evidence from other sites in the region. At Eilean Domnuill, for instance, the uncarbonised birch roundwood remains (mostly structural post/stake remains) were predominantly greater than 40 mm in diameter, whereas the charcoal (representing firewood remnants) from Eilean Domnuill, Bharpa Carinish, and Calanais, mostly consisted of small branches of less than 40 mm diameter (Fig. 9a–b; Crone Reference Crone1993b; Reference Crone2000).

Fig. 9 (a) birch roundwood (pith to bark) diameters for wood & charcoal assemblages in the Western Isles with >10 measured fragments. A bar has been placed on the chart to indicate the main range of the birch diameters in the wood layers recorded by Wilkins (Reference Wilkins1984); (b) birch roundwood ring counts for wood and charcoal assemblages in the Western Isles with >10 recorded fragments

Overall, the evidence suggests that the wood layer at Aird Calanais was probably a natural layer of branches that was deposited as a result of woodland decline around the site. The wood layer may have been exploited by Neolithic people, perhaps as a source of construction materials.

Phase 5: most recent deposits

These comprise the hagged peat [2] and the peaty topsoil and turf [1]. The peat reached a depth of 105 cm and immediately overlay the wood layer [3].

RESEARCH QUESTION 2: WHAT WERE THE TIMING, NATURE, & MECHANISMS OF DEFORESTATION IN THE CALANAIS LANDSCAPE?

The earliest evidence for woodland decline in the Calanais landscape (6309–5680 cal bc) was identified in a previously published pollen record, Calanais-3, a peat column taken approximately 0.5 km from the main Calanais monument (Figs 1 & 10; Bohncke Reference Bohncke1988; Bohncke et al. Reference Bohncke, Ashmore and Tipping2016). The decline is correlated with an increase in microcharcoal. As with the charred plant macrofossils recovered from the palaeosol at Aird Calanais, this could represent Mesolithic hunter-gatherer activity (Bohncke Reference Bohncke1988; Edwards Reference Edwards1996), or could relate to natural fires (Tipping Reference Tipping1996). However, as Bohncke et al. (Reference Bohncke, Ashmore and Tipping2016, 833) note: ‘There need have been no causal relation between the loss of Betula and burning because charcoal fragments may have become more common in the peat as the Betula canopy was reduced’. For instance, it is possible that the microcharcoal was derived from Mesolithic hearths (Edwards Reference Edwards1996, 31). Whether or not the Mesolithic woodland decline had an anthropogenic origin, vegetation management to attract deer for hunting was probably not responsible (contra Bohncke Reference Bohncke1988) because there is currently no evidence for Mesolithic deer in the Western Isles (see below; Bishop et al. Reference Bishop, Church and Rowley-Conwy2015, 67–8).

Fig. 10 Summary of the dates for the palynological, archaeological, & archaeobotanical evidence in the Calanais landscape. The woodland decline date ranges correspond to those shown in Fig. 11. The radiocarbon dates from the Aird Calanais wood layer & hearth (see also Table 1) & the Calanais wood layer were combined & calibrated using OxCal v 4.2.4 (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2009) using IntCal13 (Reimer et al. Reference Reimer, Bard, Bayliss, Beck, Blackwell, Bronk Ramsey, Grootes, Guilderson, Haflidason, Hajdas, HattŽ, Heaton, Hoffmann, Hogg, Hughen, Kaiser, Kromer, Manning, Niu, Reimer, Richards, Scott, Southon, Staff, Turney and Plicht2013). The dashed line for the cereal pollen at Calanais-3 shows the period when cereal pollen was first present in the sample, but indicates that it was discontinuously present during this period. The solid cereal line for the cereal pollen indicates the period when cereal pollen was continuously present at Calanais-3

After the Mesolithic woodland decline, the woodland regenerated (Fig. 10; Bohncke et al. Reference Bohncke, Ashmore and Tipping2016) before further woodland decline became evident. The decline in birch pollen in the late Neolithic wood layer at Aird Calanais (*2916–2878 cal bc) correlates with the first of two major late Neolithic/Bronze Age birch declines at Calanais-3 (*2897–2555 cal bc; Figs 1 & 10). The data suggest that there was a staged clearance of woodland across the Calanais landscape: the calibrated date range for the start of the late Neolithic woodland decline at Calanais-3 extends much later than the dated decline at Aird Calanais (Fig. 10) and the late Neolithic decline in AP (from 75% to 28%) at Calanais-3 was gradual, extending over a period of several hundred years (c. 2900–2500 cal bc; Bohncke et al. Reference Bohncke, Ashmore and Tipping2016). In contrast, AP values declined from 78% to 16% after the rapid birch decline at Aird Calanais (c. 2900–2800 cal bc) before declining to 5% at c. 2860–2730 cal bc, suggesting that the wood layer marked the final woodland decline at this site. At Calanais-3 there was also a Bronze Age decline, and an early Neolithic wood layer (4229–3800 cal bc), which may represent another decline phase (Fig. 10).

Though natural factors appear to have contributed to woodland decline around Aird Calanais, it is evident that Neolithic people were active in the area prior to the woodland decline. As well as the early Neolithic hearth at Aird Calanais, there is pollen evidence for early Neolithic cereal cultivation in the Calanais landscape (earliest cereal pollen evidence radiocarbon dated to 3875–3605 cal bc: see Fig. 10; Ashmore Reference Ashmore2016, 985). The charcoal recovered from Ashmore’s (Reference Ashmore2016) Calanais I excavations provides evidence for a long period of fuel use (c. 5350–1690 cal bc), showing that people were exploiting the main local trees (mostly birch, hazel, and alder: Alnus sp.) for fuel (Fig. 7 & Table 5). The age profiles of the charcoal fragments suggest that people were primarily using young branches (<10 years old) for firewood rather than whole trees (Fig. 9b; Inglis & Crone Reference Inglis and Crone2016). Such a strategy would have had little impact on the local woodlands because birch, hazel, and alder all coppice well (Rackham Reference Rackham2006, 12) and so the harvesting of young branches would have resulted in regeneration. This is supported by the pollen evidence, which shows that hazel and alder remained relatively stable during the birch decline (Bohncke et al. Reference Bohncke, Ashmore and Tipping2016).

It is likely that other human activities had a greater impact on the woodlands than firewood procurement. There is considerable archaeological evidence for human activity in the Calanais landscape in the first half of the 3rd millennium cal bc, when AP values at Calanais-3 declined from c. 75% to c. 28%, and at Aird Calanais from 78% to 5%. Deforestation at Aird Calanais and Calanais-3 occurred about the same time as the construction of the ring and central monolith at Calanais I (c. 2950–2650 cal bc), as well as the use of cultivation beds (2980–2510 cal bc; Fig. 10), which underlie and therefore pre-date the monument (Ashmore Reference Ashmore2016). Cereal pollen was identified in the Calanais-3 pollen record during the early part of this phase, and later grazing indicators such as Ribwort Plaintain (Plantago lanceolata L.) and grasses (Poaceae) increased (Bohncke Reference Bohncke1988; Bohncke et al. Reference Bohncke, Ashmore and Tipping2016). At Aird Calanais, there is some potential evidence for grazing during the Neolithic, but not for cereal cultivation: Poaceae and Plantago lanceolata/Plantago undiff. pollen increased and spores which may be associated with animal dung (Type HdV-55A, Sordaria-type: van Geel et al. Reference van Geel, Buurman, Brinkkemper, Schelvis, Aptroot, van Reenen and Hakbijl2003) were also sporadically present, but cereal pollen was absent. All of these activities would have reduced woodland coverage: woodland may have been deliberately cleared around the monument or to create new agricultural land, and grazing would have prevented woodland regeneration. The imprecision of the dating evidence (Fig. 10) means that it is not possible to establish which of these activities played a greater role in the woodland clearance. Nevertheless, both Neolithic activities and climatic deterioration contributed to woodland decline.

Despite this substantial woodland decline, minimum AP values remained above 20% throughout the Neolithic at Calanais-3 (Bohncke Reference Bohncke1988; Bohncke et al. Reference Bohncke, Ashmore and Tipping2016; see below). For much of the period c. 3000–2000 cal bc, AP values at Calanais-3 were over 40% and reached a maximum of 75% in the earlier part of this period. This suggests that the landscape around the Calanais I monument was at least partially wooded during the main period of its use (cf. Fossitt Reference Fossitt1994, 373). Sites with wider pollen source areas also show that woodland remained important in North Lewis at this time: at Loch na Beinne Bige, AP values ranged between 75% and 93% and at Loch na Muilne, AP values were between 44% and 78% during the Neolithic (Lomax Reference Lomax1997).

The wooded nature of the Neolithic landscape around Calanais I has significant implications for understanding the way the monument was experienced. It has been suggested that, in contrast to henges which formed a visual barrier between the observer and the surrounding landscape, open stone circles such as Calanais I were deliberately constructed in positions which would allow the observer to see significant landscape features, such as mountains and other monuments (Bradley Reference Bradley1998, 116; Reference Bradley2002, 130), perhaps in relation to movements of the moon (Curtis & Curtis Reference Curtis and Curtis1994; Ashmore Reference Ashmore2016, 1067). Considering the evidence for staged woodland clearance in the Calanais landscape, together with the dynamic nature of woodlands, it is probable that visibility from the monument changed considerably, both seasonally and over decades to centuries (Gillings & Wheatley Reference Gillings and Wheatley2001, 33; Cummings & Whittle Reference Cummings and Whittle2004, 69–71).

The nature of the woodland would have affected visibility from the monument. Woodlands on the Western Isles may have consisted of relatively open scrub (Tipping Reference Tipping1994), and trees of birch, willow, and hazel may have been wind-pruned and shrub-like (< 5m high: Stace Reference Stace2010), particularly in more exposed locations (Green Reference Green1964, 30; Mackenzie Reference Mackenzie2000, 4). Nonetheless, even the presence of scrub-woodland of up to 5m high would have significantly influenced visibility from Calanais I. It is also evident that more substantial trees grew in some locations in Lewis at this time: Wilkins (Reference Wilkins1984) recorded a prehistoric pine trunk that was 6 m long. Moreover, the high tree pollen values in the Calanais-3 core and elsewhere in North Lewis suggest that wind damage was not a major influence on the presence of woodland in this area. Thus, woodland would most likely have concealed important topographical features from view during much of the Neolithic.

This suggests that the wooded surroundings were central to the way Calanais I was experienced. Anthropological studies indicate that trees often provide important metaphors for human lifecycles, fertility, and regeneration, and in many societies trees have been seen as the dwelling places of ancestors and spirits (Austin Reference Austin2000, 75; Noble Reference Noble2006, 97–9). Monuments such as Calanais I may have been deliberately placed within wooded environments because of these types of symbolic associations and beliefs (cf. Austin Reference Austin2000, 75; cf. Cummings & Whittle Reference Cummings and Whittle2004, 71). The extent of landscape openness around other stone circles in Scotland in the late Neolithic/Bronze Age is difficult to identify due to the rarity of pollen sampling in the vicinity of stone circles, but appears to have varied, with some stone circles probably constructed in predominantly open landscapes (eg, the Ring of Brodgar and the Stones of Stenness, West Mainland, Orkney: cf. Jones Reference Jones1979 and Farrell et al. Reference Farrell, Bunting, Lee and Thomas2014; Renfrew Reference Renfrew1979; Ritchie Reference Ritchie1976), enabling landscape features to be seen, and others situated in open to semi-open woodland (eg, Machrie Moor, Arran: Robinson & Dickson Reference Robinson and Dickson1988; Haggarty Reference Haggarty1991), which would probably have concealed the view of significant topographical features. The variability of the environment around these stone circles, and through time, suggests that not all of these monuments were primarily intended as places from which to view these features.

Research Question 3: What does the regional pollen & plant macrofossil evidence reveal about the timing, extent, & mechanisms for woodland decline in the Western Isles?

Timing & extent of woodland decline in the Western Isles: the pollen evidence

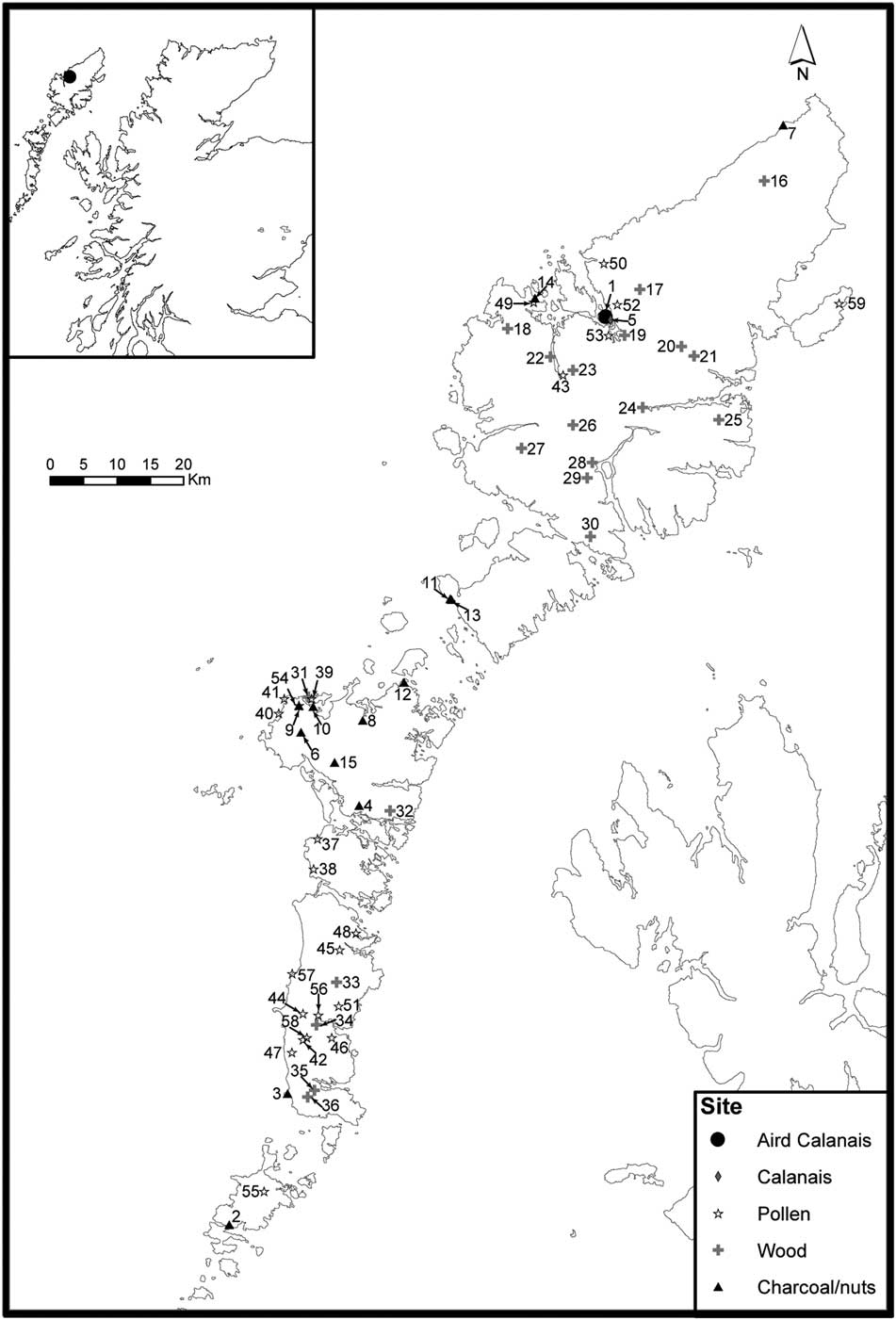

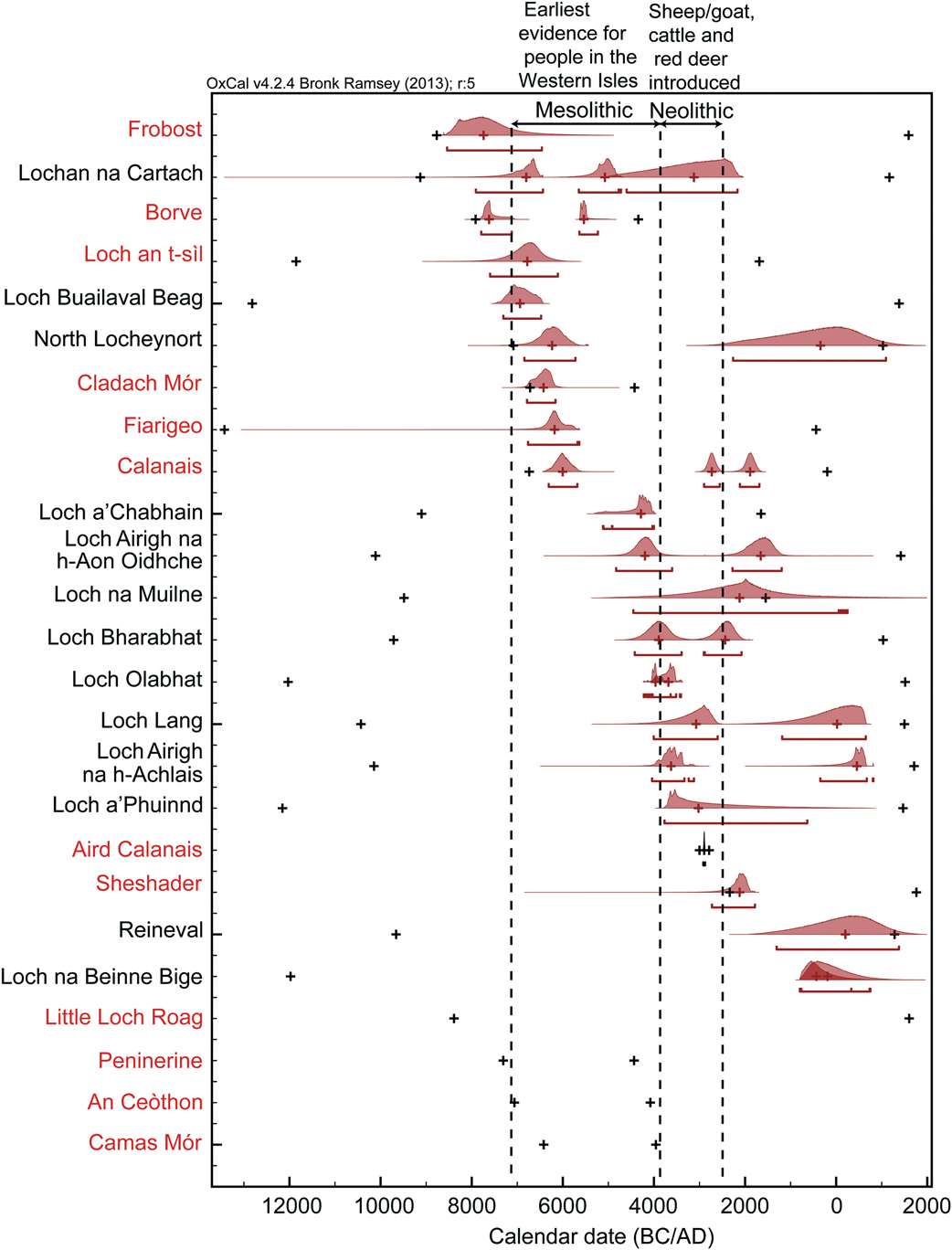

The systematic approach to data synthesis adopted here highlights some of the challenges inherent with the synthesis of palynological data at a regional level. The dates of the main phases of woodland decline in the Western Isles remain imprecise (Fig. 11). The major problem is the poor chronological control on the data, resulting from too few dates, particularly close to the major woodland declines (Parnell et al. Reference Parnell, Buck and Doan2011), and often the imprecision inherent in conventional, rather than AMS, radiocarbon dating. Consequently, many of our modelled dates of woodland decline are associated with large uncertainties.

Fig. 11 Dates of major woodland declines in the Western Isles of Scotland, ordered sequentially (the declines were initially ordered from north to south by island but no pattern was observed). The site names highlighted in red are from peat/organic deposits/mires & the site names in black are loch sites. +: the median of the modelled dates for the start & end of each sequence. Dashed lines indicate the approximate start & end of the Mesolithic & Neolithic periods in the Western Isles. The start of the Neolithic marks the first introduction of large herbivores, including red deer, sheep/goat, & cattle into the Western Isles. Where no decline is shown, there was no major decline in woodland as defined in the methodology.

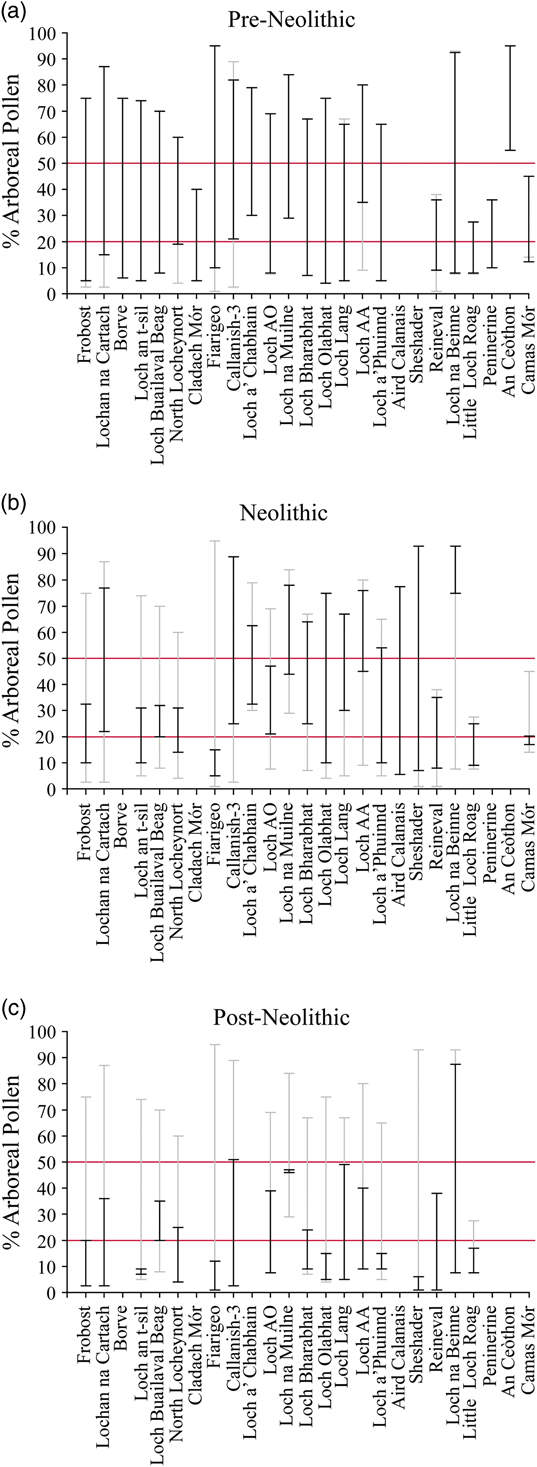

Establishing the spatial coverage and extent of woodland in past environments is also notoriously difficult (eg, Sugita et al. Reference Sugita, Gaillard and Broström1999; Bunting et al. Reference Bunting, Gaillard, Sugita, Middleton and Broström2004; Fyfe et al. Reference Fyfe, Roberts and Woodbridge2010; Reference Fyfe, Twiddle, Sugita, Gaillard, Barratt, Caseldine, Dodson, Edwards, Farrell, Froyd, Grant, Huckerby, Innes, Shaw and Waller2013), particularly in environments that are marginal for woodland (Wilkins Reference Wilkins1984; Fossitt Reference Fossitt1994; Reference Fossitt1996, 192; Gearey & Gilbertson Reference Gearey and Gilbertson1997; Edwards et al. Reference Edwards, Mulder, Lomax, Whittington and Hirons2000; Bunting Reference Bunting2002; Bunting & Farrell Reference Bunting and Farrell2017). Analyses of modern pollen rain have shown that in the relatively open windswept areas of north-west Scotland, a pollen sampling site must be within 50 m of a woodland for percentages of local AP to be higher than background AP levels, and that values as low as 15–20% AP in peat sites could reflect abundant local woodland under these conditions (Bunting Reference Bunting2002). Other analyses of British pollen sites have also demonstrated that high levels of local on-site non-arboreal taxa can mask the true abundance of arboreal pollen in an area (Fyfe et al. Reference Fyfe, Roberts and Woodbridge2010). Conversely, a model-based analysis of 73 British pollen sequences suggested that AP percentages systematically underestimate the extent of landscape openness (Fyfe et al. Reference Fyfe, Twiddle, Sugita, Gaillard, Barratt, Caseldine, Dodson, Edwards, Farrell, Froyd, Grant, Huckerby, Innes, Shaw and Waller2013), a pattern previously noted for other parts of Europe (eg, Sugita et al. Reference Sugita, Gaillard and Broström1999). Consequently, AP values can only be used as a guide for understanding the extent of prehistoric woodland coverage.

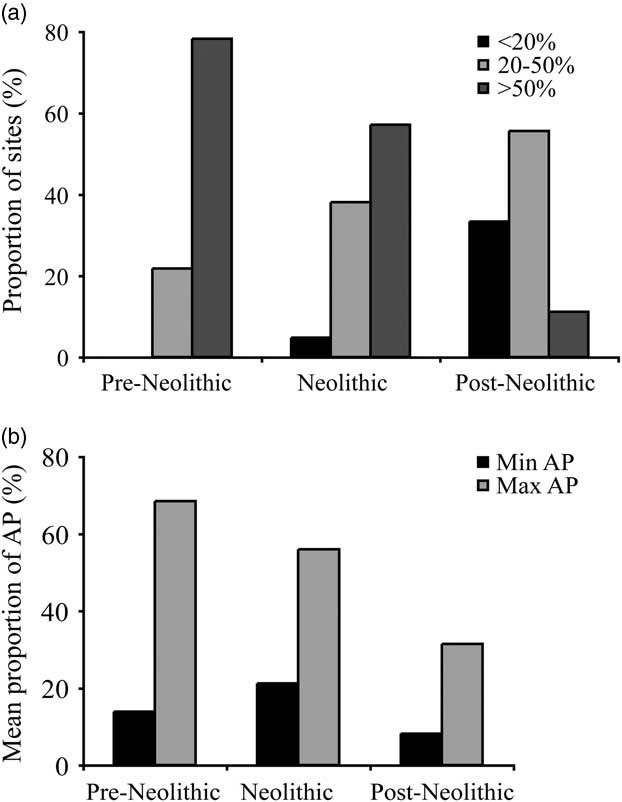

Despite these caveats, our analysis suggests that the majority of the woodland declines were not restricted to the Neolithic in the Western Isles, thus corroborating previous research that has highlighted the temporal variability of woodland decline in the region (Brayshay & Edwards Reference Brayshay and Edwards1996; Fossitt Reference Fossitt1996; Bennett et al. Reference Bennett, Bunting and Fossitt1997; Edwards et al. Reference Edwards, Mulder, Lomax, Whittington and Hirons2000; Fyfe et al. Reference Fyfe, Twiddle, Sugita, Gaillard, Barratt, Caseldine, Dodson, Edwards, Farrell, Froyd, Grant, Huckerby, Innes, Shaw and Waller2013). The first phase of woodland clearance occurred before the Neolithic for at least 50% of the sites, showing that though there is evidence for a major phase of clearance in the Neolithic at several sites, such as at Aird Calanais, Calanais-3, and Loch Olabhat (Fig. 11), much woodland had already been lost before this time. A notable proportion (20%) of the declines in woodland first occurred after the Neolithic period, but most post-Neolithic clearances represent secondary declines of already diminished woodlands.

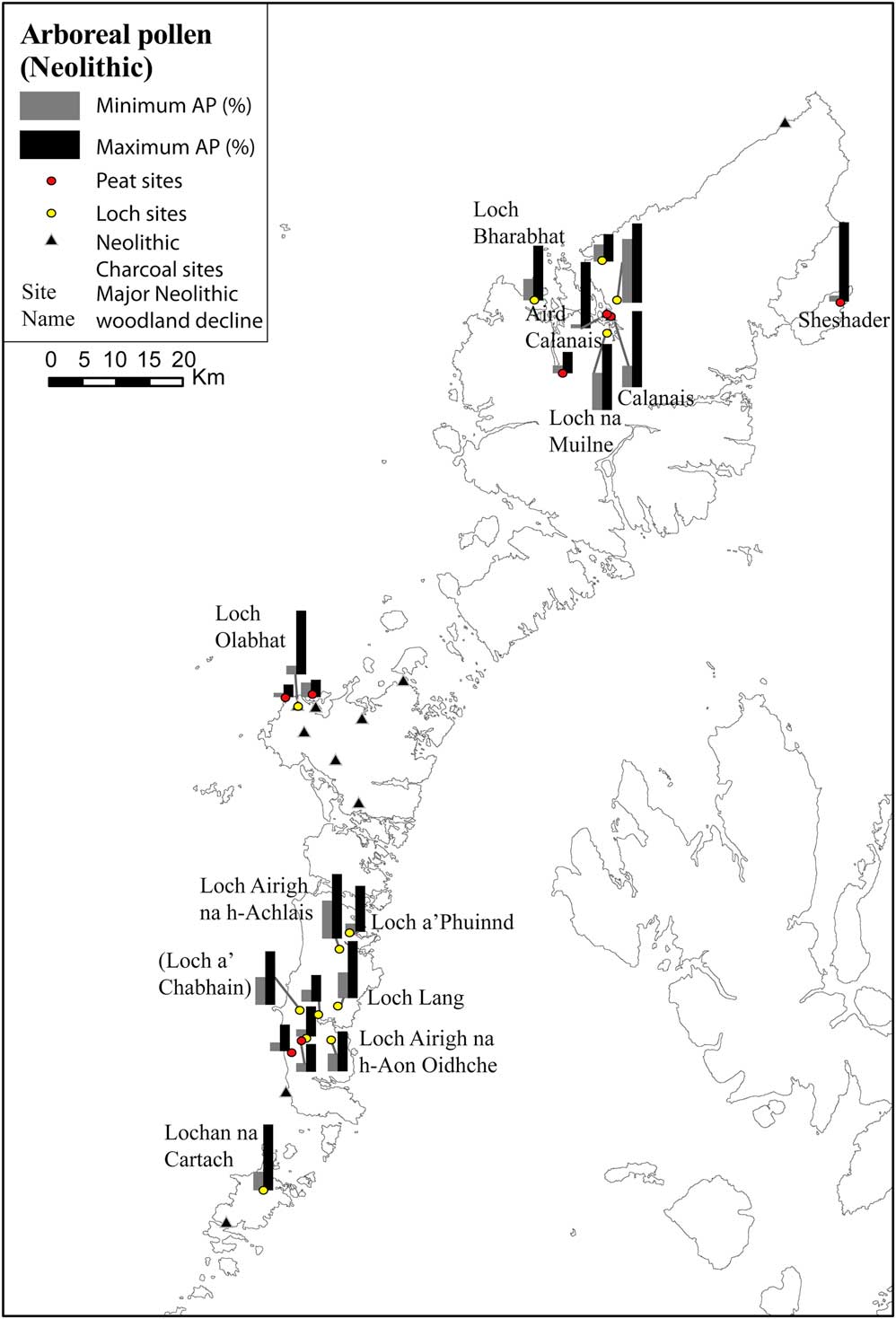

There is no obvious geographical trend in the timing of woodland decline across the Western Isles (Figs 11 & 13). However, all of the major declines at the non-loch sites occurred before c. 1500 cal bc (Fig. 11). This could reflect the location of these sites (areas susceptible to the spread of peat) and their local pollen source area: several of the early declines (Calanais, Aird Calanais, Sheshader, Frobost, Borve, Cladach Mόr) are located towards the bottom of the sample columns, and so the woodland declines may reflect the date of the onset of peat formation around these sites and the consequent reduction in woodland in these areas.

Likewise, there was no clear north-south or east–west trend in terms of minimum and maximum AP values across the Western Isles, nor was there an apparent association between site type (loch vs. non-loch sites) and the minimum and maximum AP values (Fig. 13). However, the pollen records suggest that the nature of woodland decline could vary, from single relatively short declines (e.g. Sheshader, Loch Buailaval Beag, Aird Calanais, Loch Olabhat) or multiple short and/or gradual declines at some sites (e.g. Loch na Beinne Bige, Loch Airigh na h-Aon Oidhche and Calanais) to a slow, progressive decline at others (e.g. Loch a’Phuinnd: see Table 4 for site references), and this variation is not apparent when datasets are aggregated to produce regional syntheses (cf. Fyfe et al. Reference Fyfe, Twiddle, Sugita, Gaillard, Barratt, Caseldine, Dodson, Edwards, Farrell, Froyd, Grant, Huckerby, Innes, Shaw and Waller2013).

Table 4 description of the pollen sites included in the woodland decline event models

With the exception of Loch an t-sìl (which had one radiocarbon date excluded because it produced an agreement index <60%), the radiocarbon dates removed were excluded because they were not included in the original models by the authors (references listed in the table). Site numbers refer to those in Fig. 2

Thus, despite the problems in estimating absolute landscape openness from AP percentages, our analysis (Figs 11–14) shows that: 1) although some woodland remained at most sites in the Neolithic, maximum Neolithic AP percentages were typically much lower than before, suggesting a more restricted woodland coverage than in the Mesolithic; 2) AP continued to decline further after the Neolithic at most sites; and 3) several sites, such as Little Loch Roag, Camas Mόr, and Fiarigeo had very low AP during the Neolithic.

Fig. 12 Minimum & maximum arboreal pollen percentages from pollen sites in the (a) pre-Neolithic, (b) Neolithic, and (c) post-Neolithic (see Table 4 for site details). The OxCal age-depth models were used to estimate the start (4000 cal bc) and end (2500 cal bc) of the Neolithic in each sequence. Black lines denote minimum & maximum pollen percentages for each period, grey lines denote minimum and maximum pollen percentages for each sequence & red lines denote major thresholds of AP (20% & 50%). The sites are ordered sequentially as in Fig. 11, with the earliest dated woodland declines to the left of the chart. LAA: Loch Airigh na h-Achlais. LAO: Loch Airigh na h-Aon Oidhche

Fig. 13 Proportion of arboreal pollen for the Neolithic phases of the pollen sites across the Western Isles (see Table 4), shown in relation to the location of the Neolithic sites with charcoal (Table 6). The site names are given for the sites which have a major Neolithic woodland decline, as shown in Fig. 11. The site of Loch a’ Chabhain is also highlighted here, because though the woodland decline starts at the very end of the Mesolithic phase (Fig. 11), the woodland decline phase extends into the start of the Neolithic (Mulder Reference Mulder1999)

Fig. 14 Summary of the proportion (%) of arboreal pollen from sites across the Western Isles (see Table 4); (a) maximum arboreal pollen values; (b) minimum & maximum arboreal pollen values

Timing & extent of woodland decline in the Western Isles: the archaeobotanical evidence

The Neolithic macrofossil evidence, including the new data from Aird Calanais, demonstrate that Neolithic woodland cover remained more extensive than at present. The predominant fuels exploited (Fig. 7; Table 5) were birch, hazel, and willow/poplar, and coniferous species were scarce (mostly pine, likely representing Scots Pine: Pinus sylvestris L., which is the only native pine in the Western Isles: Mullin & Pankhurst Reference Mullin and Pankhurst1991). All of these woods could have been collected from the woodlands close to the Neolithic sites: birch and/or hazel were the dominant trees/shrubs in the pollen diagrams across the Western Isles, with alder, oak and pine also important in some locations (see Table 4 for references). Willow/poplar were relatively scarce in the pollen diagrams, but considering the relatively poor pollen productivity of willow (Bradshaw Reference Bradshaw1981), it may have been a locally important component of the vegetation. This contrasts with later prehistoric and historic periods of the region, when plant macrofossil suggests that people were reliant on turf, peat and driftwood for primary fuels (Church et al. Reference Church, Peters and Batt2007b) due to the more restricted woodland availability (Figs 12 & 14). Thus, despite the woodland declines, Neolithic woodlands were still sufficiently abundant to provide an adequate fuel source.

Table 5 charred archaeobotanical remains from trees & shrubs recovered from mesolithic & neolithic sites in the western isles of scotland

However, there is some evidence that Neolithic people implemented strategies to deal with the more restricted woodland availability. Soil micromorphological evidence from Neolithic soils, together with the ecology and abundance of ‘weed’ seeds in Neolithic archaeobotanical assemblages from the Western Isles, suggests that other materials were sometimes used for fuels at this time – principally turf, and to a lesser extent dung and peat (Mills et al. Reference Mills, Armit, Edwards, Grinter and Mulder2004; Bishop et al. Reference Bishop, Church and Rowley-Conwy2009). Likewise, the charcoal assemblage from the Neolithic site at An Doirlinn, South Uist, suggests that woodlands were less readily available in this area. The assemblage contained a notable proportion of heather – a small shrub which is less preferable for burning than other larger taxa – and the only evidence for non-native driftwood (spruce/larch: Picea/Larix sp. and possibly yew: Taxus sp.) exploitation for fuel in the Neolithic of the region (Fig. 7; Table 5). The inhabitants of the site also collected deadwood from large branches or trunks of pine (Kabukcu et al. Reference Kabukcu, Jones and Sturt2017).

While driftwood and heather were used at other Neolithic sites in the Western Isles, it seems that it was mostly selected for purposes other than burning. At Eilean Domnuill, North Uist, a single waterlogged post of the non-native species larch (probably driftwood – cf. Dickson Reference Dickson1992) was discovered together with birch and willow stake/post remains and heather twigs (Crone Reference Crone2000). The absence of non-native woods and heather in the charcoal assemblage suggests that though whole driftwood trees were sometimes collected for construction, and heather for thatching, bedding or rope-making, native trees were usually sufficiently abundant for firewood collection in the Neolithic (ibid.).

Mechanisms of woodland decline in the Western Isles

It is difficult to disentangle the different processes contributing to woodland loss in the region (Bennett et al. Reference Bennett, Bunting and Fossitt1997; Edwards et al. Reference Edwards, Mulder, Lomax, Whittington and Hirons2000; Church Reference Church2006). The consequences of multiple short-term and long-term processes – pedogenesis and paludification, climate change, machair development and sea-level rise, and human impacts of different kinds from the Mesolithic onwards – are likely all reflected in the pollen records. The relative importance of these processes at particular sites in the Western Isles have been discussed at length elsewhere (see Table 4 references). However, there are three novel points to be made with reference to potential human impacts in the Neolithic that emerge from our synthesis of pollen and plant macro-fossil data, and from the archaeological record.

First, a range of different Neolithic practices would have caused temporary or small-scale reductions in woodland (cf. Bishop et al. Reference Bishop, Church and Rowley-Conwy2015 on Mesolithic impacts), but not all of these strategies would have resulted in large-scale woodland decline. For example, significant woodland clearances would not have been required for cereal cultivation (Jones Reference Jones2005) because Neolithic cereals were probably grown in small-scale permanent plots close to settlements (Barclay Reference Barclay2003, 148; Bogaard & Jones Reference Bogaard and Jones2007). Clearing forests of mature trees for settlements and arable plots with stone axes or by ring barking would have been challenging, and existing open areas were probably primarily used and expanded where necessary (Brown Reference Brown1997; Bell & Noble Reference Bell and Noble2012, 81). Similarly, Neolithic firewood collection would have had a minimal impact on woodlands. Though birch and hazel were the main species used for fuel (Table 5; Fig. 7), current evidence suggests that Neolithic people were mainly using narrow diameter branches and twigs (<40 mm), rather than trunks or rootwood for firewood (Fig. 9; Boardman Reference Boardman1995, 153; Gale Reference Gale1999; Crone Reference Crone2000, 45; Kabukcu et al. Reference Kabukcu, Jones and Sturt2017). Age and size data from individual charcoal assemblages are not available and so it is not possible to assess whether the firewood was systematically harvested from sustainably-managed woodlands (eg, by coppicing: Out et al. Reference Out, Vermeeren and Hänninen2013). However, as mentioned previously, birch, hazel, willow/poplar and alder all coppice well (Rackham Reference Rackham2006, 12) and so would regenerate if living branches were harvested.

On the other hand, the removal of whole trees for construction may have been a major cause of woodland decline. Whole trees would have been harvested for structural timbers in houses (post-holes are present at several sites), for fencing, and as substructure for semi-artificial islet settlements, for example Eilean Domnhuill (see fig. 9; Crone Reference Crone2000; Mills et al. Reference Mills, Armit, Edwards, Grinter and Mulder2004).

Likewise, the Neolithic introduction of large terrestrial mammals to the Western Isles would have had a major impact on the woodlands (Bennett et al. Reference Bennett, Bunting and Fossitt1997, 137; Mills et al. Reference Mills, Armit, Edwards, Grinter and Mulder2004, 892; cf. Dugmore et al. Reference Dugmore, Church, Buckland, Edwards, Lawson, McGovern, Panagiotakopulu, Simpson, Skidmore and Sveinbjarnardóttir2005; Bohncke et al. Reference Bohncke, Ashmore and Tipping2016). The area possessed no native mammalian fauna, except for pygmy shrews, voles/mice, and hares (Serjeantson Reference Serjeantson1990; Hamilton-Dyer Reference Hamilton-Dyer2005; Fairnell & Barrett Reference Fairnell and Barrett2007), because the 27 km wide channel between the mainland and the Western Isles prevented most terrestrial mammals from colonising naturally. Mesolithic excavations in the region (see Table 5; see also Bishop et al. Reference Bishop, Church and Rowley-Conwy2010; Reference Bishop, Church and Rowley-Conwy2011) have so far produced no evidence for native large herbivores (Hamilton-Dyer Reference Hamilton-Dyer2005; Peter Rowley-Conwy pers. comm.), suggesting that Mesolithic people did not introduce them to the islands. Red and roe deer were present in the Inner Hebrides from the Mesolithic onwards (Kitchener et al. Reference Kitchener, Bonsall and Bartosiewicz2004), but the earliest examples from the Western Isles, (eg, Eilean Domhnuill: 3792–2356 cal bc; Mills et al. Reference Mills, Armit, Edwards, Grinter and Mulder2004) date to the Neolithic (Serjeantson Reference Serjeantson1990; Smith & Mulville Reference Smith and Mulville2004; Finlay Reference Finlay2006; Schulting Reference Schulting2013), when they were probably introduced (Serjeantson Reference Serjeantson1990; Stanton et al. Reference Stanton, Mulville and Bruford2016) together with sheep/goat, cattle, and pigs. With the absence of grazing mammals prior to the introduction of farming, the woodlands of the Western Isles would have been more susceptible to the impacts of Neolithic grazing. Therefore, Neolithic grazing by domesticates and deer would have maintained and expanded woodland clearings on an unprecedented scale (see Fig. 11).

Secondly, while it is tempting to link the Neolithic woodland declines to an increase in human population size after the Mesolithic and a resulting increase in the intensity of land use (Woodbridge et al. Reference Woodbridge, Fyfe, Roberts, Downey, Edinborough and Shennan2014), it is not strictly possible to assess whether Mesolithic populations were smaller than Neolithic/Bronze Age populations, because Mesolithic sites are severely under-represented in the archaeological record. The first Mesolithic site was only identified in 2001 at Northton, Harris (Gregory et al. Reference Gregory, Murphy, Church, Edwards, Guttmann and Simpson2005), and apart from the new archaeobotanical evidence of possible anthropogenic origin at Aird Calanais, there are just five other known Mesolithic sites in the region (Table 5). Rather than indicating a rarity of Mesolithic communities in the area, the scarcity of sites probably reflects the generally ephemeral nature of Mesolithic sites in Scotland (Wickham-Jones Reference Wickham-Jones2004), the difficulty of locating such evidence under thick peat and machair deposits, and the drowning of coastal sites by Holocene relative sea level rise (Edwards Reference Edwards1996, 34; Edwards & Sugden Reference Edwards and Sugden2003, 11). It is possible that the rich marine resources available on the islands could have sustained relatively large Mesolithic populations, as has been suggested for Mesolithic hunter-gatherer communities in southern Scandinavia through analogy with recent sedentary hunter-gatherer groups in North America (Rowley-Conwy Reference Rowley-Conwy1983; Reference Rowley-Conwy2011, 440). Consequently, it is possible that Mesolithic and Neolithic population sizes in the Western Isles were not dissimilar.

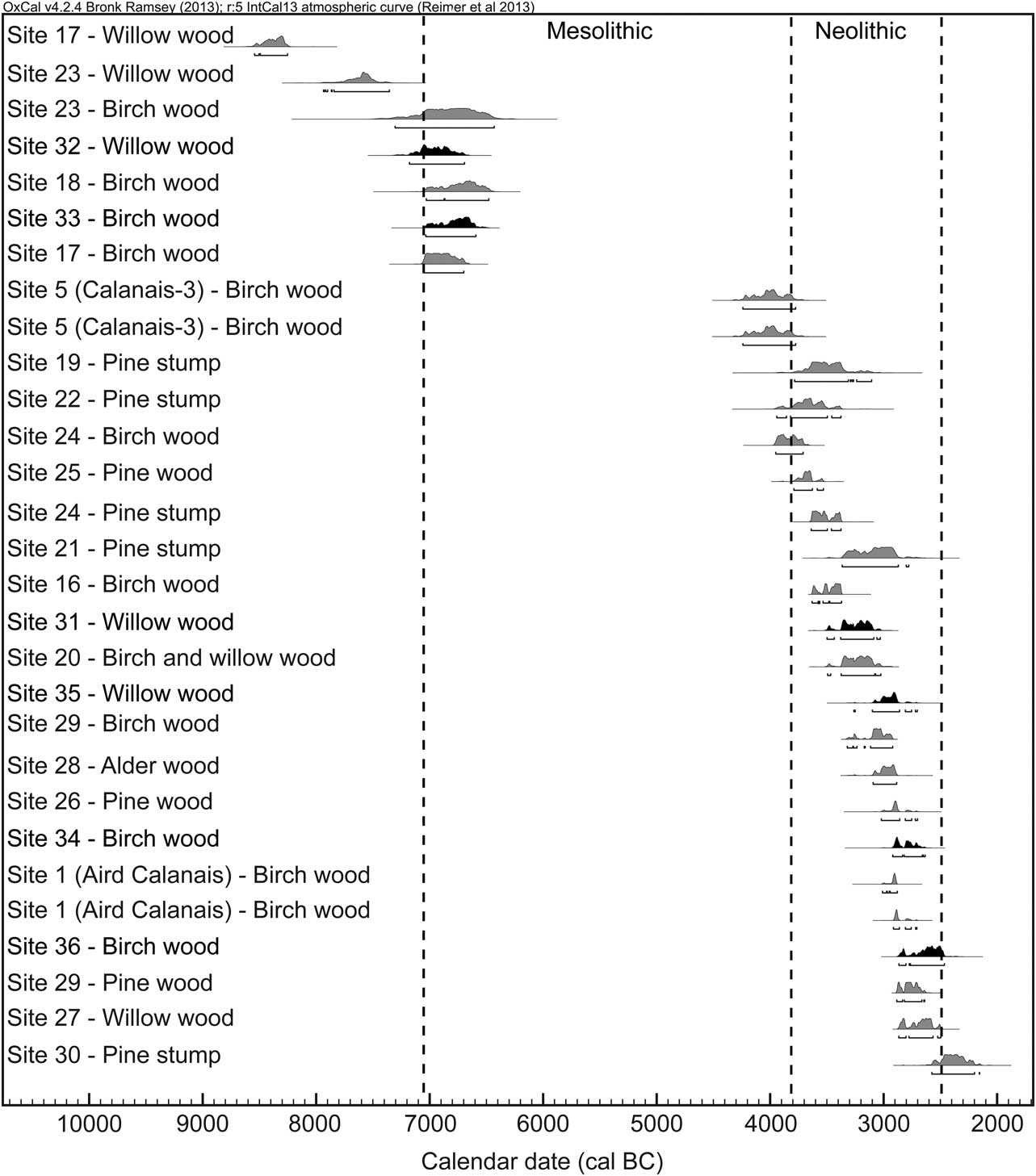

Thirdly, since a large proportion of the woodland declines occurred prior to the Neolithic, the introduction of Neolithic practices cannot have been the only cause of primary woodland decline in this region. Natural climatic and environmental changes, alongside Mesolithic exploitation of woodlands (Edwards Reference Edwards1996; Bishop et al. Reference Bishop, Church and Rowley-Conwy2015) were also important. At least one of the declines (eg, Borve: 7790–7122 cal bc) occurred before the earliest evidence for Mesolithic occupation of the Western Isles (Fig. 11; earliest evidence from Northton, Harris at 7051–6104 cal bc: Gregory et al. Reference Gregory, Murphy, Church, Edwards, Guttmann and Simpson2005; Simpson et al. Reference Simpson, Murphy and Gregory2006; Ascough et al. Reference Ascough, Church and Cook2017), which suggests a natural cause for at least some of the declines. As noted above, many of these early woodland declines may relate to the localised spread of peat around the sampling sites. Indeed, it is notable that a high proportion of the woodland declines (Fig. 11) fall within the two main phases of dated wood preservation within peat (c. 8600–6000 cal bc and c. 4000–2000 cal bc: Figs 11 & 15, Table 6), the latter of which appears to reflect a regional pattern of fossil wood preservation occurring elsewhere in North-west Europe (McGeever & Mitchell Reference McGeever and Mitchell2015). Bennett et al. (Reference Bennett, Bunting and Fossitt1997, 129) similarly observe that ‘trees tend to be preserved when, on a regional scale, woodland is in decline’ and Wilkins (Reference Wilkins1984, 256) proposes that macroscopic wood remains are likely to represent ‘the end of a period of tree cover’. Consequently, the wood layers in peat may provide a proxy for the beginning of particular periods of accelerating blanket peat expansion, reflecting increased bog-surface wetness, perhaps linked to an increasingly wet climate (Fossitt Reference Fossitt1996, 193). The absence of fossil wood within the peat in subsequent periods could reflect the fact that the bog and surrounding area had become too wet for further tree growth (Edvardsson et al. Reference Edvardsson, Linderson, Rundgren and Hammarlund2012), as well as a decline in the availability of local seed sources for recolonisation after the woodland declined (McGeever & Mitchell Reference McGeever and Mitchell2015). Hence blanket peat expansion was most probably responsible for many of the Mesolithic and Neolithic woodland declines.

Fig. 15 Radiocarbon dated sub-fossil wood from peat sequences in the Western Isles (Bohncke Reference Bohncke1988; Fossitt Reference Fossitt1996; Wilkins Reference Wilkins1984), ordered sequentially. The black distributions are the wood layers located on the Uists, Benbecula, and Barra, and the grey distributions are the wood layers located on Lewis and Harris. Site numbers correspond to those shown in Table 5 and Fig. 2.

Table 6 description of the wood sites included in the review

Site numbers refer to those in Fig. 2. Uncalibrated radiocarbon dates were calibrated within Oxcal v 4.2 (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2009) using Intcal13 (Reimer et al. Reference Reimer, Bard, Bayliss, Beck, Blackwell, Bronk Ramsey, Grootes, Guilderson, Haflidason, Hajdas, HattŽ, Heaton, Hoffmann, Hogg, Hughen, Kaiser, Kromer, Manning, Niu, Reimer, Richards, Scott, Southon, Staff, Turney and Plicht2013)

Overall, the available evidence suggests that the frequency and extent of woodlands in the Western Isles began to be reduced in many areas during the Mesolithic and that the woodlands were reduced still further during the Neolithic period. This was most likely primarily a consequence of the direct harvesting of trees for construction purposes and the spread of blanket peat in the Mesolithic and Neolithic, as well as the introduction of grazing mammals in the Neolithic. However, despite the woodland declines, tree populations remained sufficiently abundant for Neolithic fuel procurement. This suggests that though the initiation of Neolithic practices accelerated woodland decline, it was not the introduction of farming per se that destroyed the woodlands.

RESEARCH QUESTION 4: WHAT IMPLICATIONS DOES THE EVIDENCE FROM THE WESTERN ISLES HAVE FOR UNDERSTANDING THE INTERACTIONS BETWEEN FIRST FARMERS & WOODLANDS IN THE NORTH ATLANTIC REGION?

It is often assumed that woodland decline was an automatic consequence of the introduction of farming: hunter-gatherers are often perceived as ecologically skilled managers, whereas farmers are often viewed as inherently ecologically damaging (Austin Reference Austin2000, 72–3; Warren Reference Warren2005, 69). As discussed, deforestation in the Western Isles began prior to the introduction of farming. Therefore, a key question is whether the first farmers were generally responsible for destroying the woodlands as they colonised the North Atlantic region.

The spread of agriculture across the North Atlantic region was initiated within contrasting cultural and social systems – by Neolithic farmers (c. 3800 cal bc) in Atlantic Scotland (Western Isles, Orkney, Shetland) and by Norse settlers in the Faroes, Iceland, and Greenland (9th–11th centuries cal AD). Despite the cultural differences between Neolithic farmers and the Norse, comparable small-scale farming systems, based principally on the husbandry of cattle and sheep/goat (Church et al. Reference Church, Arge, Brewington, McGovern, Woollett, Perdikaris, Lawson, Cook, Amundsen, Harrison, Krivogorskaya and Dunbar2005; Dugmore et al. Reference Dugmore, Church, Buckland, Edwards, Lawson, McGovern, Panagiotakopulu, Simpson, Skidmore and Sveinbjarnardóttir2005; Schulting Reference Schulting2013) and the cultivation of barley (Scotland: Bishop et al. Reference Bishop, Church and Rowley-Conwy2009; Faroe Islands: Church et al. Reference Church, Arge, Brewington, McGovern, Woollett, Perdikaris, Lawson, Cook, Amundsen, Harrison, Krivogorskaya and Dunbar2005; Iceland: Guðmundsson Reference Guðmundsson2009; Zori et al. Reference Zori, Byock, Erlendsson, Martin, Wake and Edwards2013; Bishop & Guðmundsson in prep.) were introduced throughout the area. Climatic and ecological differences across the region allow useful parallels to be drawn between the different environmental settings.

Orkney and Shetland

In contrast to the other areas of the North Atlantic settled by the first farmers, both the Western Isles and Orkney had a pre-existing Mesolithic population for several millennia prior to the introduction of farming (Gregory et al. Reference Gregory, Murphy, Church, Edwards, Guttmann and Simpson2005; Lee & Woodward Reference Lee and Woodward2009; Farrell et al. Reference Farrell, Bunting, Lee and Thomas2014, 230). Current evidence suggests a slightly later settlement for Shetland: the earliest site at West Voe is dated to the late 5th millennium cal bc (Melton Reference Melton2009). As in the Western Isles, the first archaeological evidence for grazing mammals on Orkney and Shetland was not until the 4th millennium cal bc (Schulting Reference Schulting2013, 324; no definite red deer bones were recovered from the earliest sites in the region: West Voe, Shetland: Melton Reference Melton2009 or Links House, Orkney: Dan Lee pers. comm.). This suggests that there were no grazing mammals present in the area prior to the Neolithic. There are hints of potential ‘grazing’ activity in the pollen record on Shetland prior to the 4th millennium cal bc (Bennett et al. Reference Bennett, Boreham, Sharp and Switsur1992), possibly representing Mesolithic human activities yet to be confirmed in the archaeological record. If so, Shetland would not be unique: in both the Western Isles and the Faroe Islands, the earliest evidence for human settlement was observed in palaeoenvironmental records decades before the first archaeological discoveries (Edwards & Sugden Reference Edwards and Sugden2003,11; Church et al. Reference Church, Arge, Edwards, Ascough, Bond, Cook, Dockrill, Dugmore, McGovern, Nesbitt and Simpson2013).

The pattern of deforestation in Orkney and Shetland is comparable to the Western Isles. The decline of the birch-hazel woodlands which covered much of Orkney and Shetland in the early post-glacial was diachronous, with major declines occurring both prior to and after the introduction of agriculture, and with woodland resources remaining available for exploitation in many areas throughout the Neolithic period (Bennett et al. Reference Bennett, Bunting and Fossitt1997; Farrell et al. Reference Farrell, Bunting, Lee and Thomas2014). Open areas suitable for grazing and the cultivation of cereals in small-scale intensive plots (cf. Jones Reference Jones2005) would already have existed within the environment without the need for major clearance, and this may have muted the immediate environmental impact of the introduction of farming.

The woodland exploitation strategies employed by the first farmers in the Northern Isles may also have helped to conserve resources. In Orkney, many of the earliest structures were constructed of timber, but in the later Neolithic there was a shift from wood to stone as a construction material, in spite of the fact that woodlands would have remained available for building timber at this time (Farrell et al. Reference Farrell, Bunting, Lee and Thomas2014). There is also extensive archaeobotanical evidence in Neolithic Orkney for the use of turf/peat as a fuel (Bond Reference Bond2007b, 160; Bishop et al. Reference Bishop, Church and Rowley-Conwy2009, 83; Miller et al. Reference Miller, Ramsay, Alldritt and Bending2016, 498; Rowley-Conwy in prep.) alongside native woods (Dickson Reference Dickson1983; Reference Dickson2000; Bond Reference Bond2007a; Reference Bond2007b; Miller et al. Reference Miller, Ramsay, Alldritt and Bending2016). There is greater evidence for the use of driftwood as a fuel than in the Western Isles, with spruce/larch charcoal recovered from several early and late Neolithic sites on Orkney (Knap of Howar: Dickson Reference Dickson1983; Skara Brae: Dickson Reference Dickson2000; Stonehall Farm: Miller et al. Reference Miller, Ramsay, Alldritt and Bending2016, 499). The implementation of a broad fuel exploitation strategy and the shift away from the use of wood for construction could be viewed as deliberate conservation mechanisms.

Faroe Islands

The earliest evidence for human occupation in Faroe Islands dates to the 4th–6th centuries cal AD. Current evidence suggests that this phase of pre-Norse settlement was small-scale, and perhaps discontinuous, and that the main phase of colonisation was during the Norse period, in the 9th century cal AD (Church et al. Reference Church, Arge, Edwards, Ascough, Bond, Cook, Dockrill, Dugmore, McGovern, Nesbitt and Simpson2013).

The Faroe Islands provide an interesting contrast to the Western Isles because the environmental impact of the introduction of farming was relatively slight. At many sites, there was little vegetation change after the Norse colonisation (Lawson et al. Reference Lawson, Edwards, Church, Newton, Cook, Gathorne-Hardy and Dugmore2008), despite the fact that grazing mammals were introduced for the first time (Dugmore et al. Reference Dugmore, Church, Buckland, Edwards, Lawson, McGovern, Panagiotakopulu, Simpson, Skidmore and Sveinbjarnardóttir2005, 24). This difference can be explained by the fact that the Faroes were already predominantly treeless prior to human settlement: the islands were covered in a mixture of blanket mire, heathland, grassland, and tall herb communities with very little juniper, birch, and willow (Edwards et al. Reference Edwards, Borthwick, Cook, Dugmore, Mairs, Church, Simpson and Adderley2005a; Lawson et al. Reference Lawson, Church, McGovern, Arge, Woollett, Edwards, Gathorne-Hardy, Dugmore, Cook, Mairs, Thomson and Sveinbjarnardόttir2005; Reference Lawson, Edwards, Church, Newton, Cook, Gathorne-Hardy and Dugmore2008). Therefore, the introduction of farming had a very small immediate effect because the relatively treeless environment was less susceptible to degradation by introduced grazing mammals (Lawson et al. Reference Lawson, Church, McGovern, Arge, Woollett, Edwards, Gathorne-Hardy, Dugmore, Cook, Mairs, Thomson and Sveinbjarnardόttir2005; Reference Lawson, Edwards, Church, Newton, Cook, Gathorne-Hardy and Dugmore2008). Indeed, in some areas of the Faroe Islands, tree pollen declined more significantly prior (c. cal AD 250) to the first continuous evidence of human settlement than after it (Hannon et al. Reference Hannon, Bradshaw, Bradshaw, Snowball and Wastegård2005), probably reflecting the natural spread of heathland (Lawson et al. Reference Lawson, Church, Edwards, Cook and Dugmore2007a) and/or climate change (Hannon et al. Reference Hannon, Wastegård, Bradshaw and Bradshaw2001,138; 2005). This supports the suggestion that autogenic soil changes and/or climate change may have played a part in the decline of tree populations in other parts of the North Atlantic region, including the Western Isles (Bennett et al. Reference Bennett, Boreham, Sharp and Switsur1992, 264).

Iceland and Greenland

In contrast to Atlantic Scotland, the Norse settlers in Iceland and Greenland rapidly cleared significant areas of the native birch-willow scrub woodlands during the initial settlement period (eg, Hallsdóttir Reference Hallsdóttir1987; Dugmore et al. Reference Dugmore, Church, Buckland, Edwards, Lawson, McGovern, Panagiotakopulu, Simpson, Skidmore and Sveinbjarnardóttir2005; Hallsdóttir & Caseldine Reference Hallsdóttir and Caseldine2005; Edwards et al. Reference Edwards, Schofield and Mauquoy2008; Gauthier et al. Reference Gauthier, Bichet, Massa, Petit, Vannière and Hervé2010). The difference in the speed and scale of the clearance probably relates to the greater scale of the woodland exploitation employed by the first farmers in Iceland and Greenland: the Norse Icelanders and Greenlanders harvested birch on a large scale for charcoal production and almost exclusively used birch wood for fuel (Church et al. Reference Church, Dugmore, Mairs, Millard, Cook, Sveinbjarnardóttir, Ascough, Newton and Roucoux2007a; Bishop Reference Bishop2008; Bold Reference Bold2012; Mooney Reference Mooney2013; Bishop et al. Reference Bishop, Church, Dugmore, Madsen and Møller2013b; Bishop & Guðmundsson in prep.).

The greater environmental sensitivities of Iceland and Greenland to human impact also played a role in the scale and rapidity of the woodland decline (Dugmore et al. Reference Dugmore, Church, Buckland, Edwards, Lawson, McGovern, Panagiotakopulu, Simpson, Skidmore and Sveinbjarnardóttir2005; Streeter et al. Reference Streeter, Dugmore, Lawson, Erlendsson and Edwards2015). Though Greenland possessed native grazing mammals such as caribou (reindeer: Rangifer tarandus L.), Iceland lacked indigenous grazing mammals. Consequently, Iceland’s woodlands were more susceptible to degradation by introduced domesticates (Dugmore et al. Reference Dugmore, Church, Buckland, Edwards, Lawson, McGovern, Panagiotakopulu, Simpson, Skidmore and Sveinbjarnardóttir2005). Also, in contrast to the Western Isles, people were absent from Iceland and the first Norse settlement areas in Greenland prior to landnám (ibid.), so there was greater need for rapid clearance to create grazing land.

Despite the relatively rapid woodland decline in Iceland after landnám, pollen evidence provides evidence of substantial pre-settlement woodland decline at some sites, and for a considerable degree of local variation in woodland coverage through time: this highlights the role of climatic and environmental factors in woodland decline in the North Atlantic region (Streeter et al. Reference Streeter, Dugmore, Lawson, Erlendsson and Edwards2015). The palynological record also shows that woodland survived for hundreds of years after settlement in some parts of Iceland and Greenland (Dugmore et al. Reference Dugmore, Church, Buckland, Edwards, Lawson, McGovern, Panagiotakopulu, Simpson, Skidmore and Sveinbjarnardóttir2005; Lawson et al. Reference Lawson, Gathorne-Hardy, Church, Newton, Edwards and Dugmore2007b; Schofield & Edwards Reference Schofield and Edwards2011), particularly in the wider environment away from the Norse farms (Streeter et al. Reference Streeter, Dugmore, Lawson, Erlendsson and Edwards2015).