Within the broader context of population aging, the rates of low vision among older adults is steadily increasing (Watson, Reference Watson2001). Low vision is defined as a permanent loss of vision that cannot be corrected with conventional glasses, contact lenses, or medical or surgical procedures, and interferes “with the performance of common age-appropriate seeing tasks” (Vision Rehabilitation Evidence Based Review Team, 2005, p. 10). Macular degeneration, glaucoma, and diabetic retinopathy are among the most prevalent eye conditions affecting older adults, with such conditions often collectively referred to as age-related vision loss (ARVL) (Watson, Reference Watson2001).

ARVL has a profound impact on social participation and occupational engagement, a term that encompasses both the performance of everyday activities and the meaning associated with them (Townsend & Polatajko, Reference Townsend and Polatajko2007), of older adults with low vision. For example, older adults with low vision experience restrictions in relation to their participation in self-care activities such as dressing, eating, medication management, and shopping (Berger & Porell, Reference Berger and Porell2008; Grue et al., Reference Grue, Ranhoff, Noro, Finne-Soveri, Jensdottir and Ljunggren2008; Knudtson, Klein, Klein, Cruickshanks, & Lee, Reference Knudtson, Klein, Klein, Cruickshanks and Lee2011). Further, the literature supports a negative impact of low vision on leisure participation as well as paid or voluntary work (Alma et al., Reference Alma, Van der Mei, Melis-Dankers, Van Tilburg, Groothoff and Suurmeijer2011; Boerner & Wang, Reference Boerner and Wang2010). Lastly, the literature supports a strong link between ARVL and compromised community mobility (Laliberte Rudman & Durdle, Reference Laliberte Rudman and Durdle2008; McGrath, Laliberte Rudman, Trentham, Polgar, & Spafford, Reference McGrath, Laliberte Rudman, Trentham, Polgar and Spafford2017). In turn, these restrictions on participation and engagement have been linked to a variety of negative outcomes, including an increased risk of falls, an increased probability of transitioning to a nursing home, social isolation, depression, and compromised quality of life (Harada et al., Reference Harada, Nishiwaki, Michikawa, Kikuchi, Iwasawa and Nakano2008; Laitinen et al., Reference Laitinen, Sainio, Koskinen, Rudanko, Laatikainen and Aromaa2007; Laliberte Rudman & Durdle, Reference Laliberte Rudman and Durdle2008).

To support their continued engagement in meaningful occupation or everyday activities, older adults with vision loss are commonly prescribed low vision assistive devices (LVADs) (Laliberte Rudman, Huot, Klinger, Leipert, & Spafford, Reference Laliberte Rudman, Huot, Klinger, Leipert and Spafford2010; Moore & Miller, Reference Moore and Miller2003). LVADs are defined as “any item, piece of equipment, or product system, whether acquired commercially, modified, or customized, that is used to increase, maintain, or improve the functional visual capabilities of an individual with a disability” (Copolillo, Reference Copolillo and Soderback2009, p. 147). LVADs fall under the broader umbrella of assistive technology (AT).

According to the literature, when AT is selected, accepted, and used appropriately by older adults with ARVL, it has the potential to enhance personal safety (McGrath & Astell, Reference McGrath and Astell2017), promote social and community participation (Fok, Polgar, Shaw, & Jutai, Reference Fok, Polgar, Shaw and Jutai2011), support aging in place (McCreadie & Tinker, Reference McCreadie and Tinker2005), and enhance occupational engagement (McGrath & Astell, Reference McGrath and Astell2017). Unfortunately, despite the benefits of LVADs, the literature suggests that an overwhelming number of older adults with ARVL never acquire the technologies recommended or abandon them within approximately 4 months of acquisition (Strong, Jutai, Bevers, Hartley, & Plotkin, Reference Strong, Jutai, Bevers, Hartley and Plotkin2003). For example, in their scoping review Lorenzini and Wittich (Reference Lorenzini and Wittich2020) aimed to determine those factors including, demographic, physical, psycho-social, device-related, environmental, and interventional, that were associated with the (non-)use of magnifying low vision aids. A summary of the selected articles (n = 21), found high variability, ranging between 2.3 and 50 per cent, for (non-)use of magnifying low vision aids.

Although there has been considerable research focused on how various economic, practical, aesthetic, and psychosocial factors (Davenport, Mann, & Lutz, Reference Davenport, Mann and Lutz2012; McCreadie & Tinker, Reference McCreadie and Tinker2005; Peek et al., Reference Peek, Wouters, Van Hoof, Luijkx, Boeije and Vrijhoef2014) influence technology adoption and use by older adults, few studies have focused on technology adoption among older adults with low vision, with a few notable exceptions (Copolillo & Teitelman, Reference Copolillo and Teitelman2005; McGrath & Astell, Reference McGrath and Astell2017). For example, in their critical ethnographic study of 10 older adults with ARVL, McGrath and Astell (Reference McGrath and Astell2017) found that the incorporation of LVADs into daily life provided the participants with feelings of independence, safety, and insurance while further supporting engagement in meaningful activities and providing validation of their disability. Conversely, the authors also unpacked various barriers to technology acquisition and use including practical limitations such as cost, inadequate training, usability limitations, a lack of awareness of low vision rehabilitation services including what LVADs are available to support occupational engagement, a fear of being taken advantage of when using obvious markers of vision loss, such as the white cane, and the desire to preserve a self-image consistent with independence and self-reliance, which was often in conflict with the image portrayed by using particular LVADs.

Despite increasing evidence that environmental forces such as social stigma and economic conditions shape AT use amongst older adults, there has been little attention to the discursive environment. Discourses are vital to attend to given that the way objects, such as AT, and subjects, such as aging persons, are constructed through policy, organizational, media, and other types of texts influences not only how aging individuals understand themselves and how to best manage aging, but also broader social perceptions regarding what types of support should be provided for aging citizens (Laliberte Rudman & Molke, Reference Laliberte Rudman and Molke2009; Rozanova, Reference Rozanova2010). In particular, newspapers are an important media source for older adults and are influential in the social construction of aging (Fraser, Kenyon, Lagacé, Wittich, & Southall, Reference Fraser, Kenyon, Lagacé, Wittich and Southall2016; Ylänne, Williams, & Wadleigh, Reference Ylänne, Williams and Wadleigh2010).

Within the Canadian context, a small but growing body of contemporary literature has focused on how aging is addressed in newspapers. Many of these studies have focused on how discourses of “positive” aging have been addressed, highlighting critical implications such as enhanced exclusion and discrimination towards aging individuals who experience dependency and disability (Laliberte Rudman, Reference Laliberte Rudman2006; Laliberte Rudman, Huot, & Dennhardt, Reference Laliberte Rudman, Huot and Dennhardt2009; Laliberte Rudman & Molke, Reference Laliberte Rudman and Molke2009; Rozanova, Reference Rozanova2006, Reference Rozanova2010; Wada, Clarke, & Rozanova, Reference Wada, Clarke and Rozanova2015). Of relevance to our study, Fraser et al. (Reference Fraser, Kenyon, Lagacé, Wittich and Southall2016) conducted a critical discourse analysis of texts in one Canadian newspaper that addressed age-related chronic conditions and AT use. These authors found that negative ageist stereotypes were taken up in ways that created a dichotomy such that assistive devices were portrayed as helpful in achieving the ideal of autonomy, but, given their associations with stereotypes of vulnerability and decline, were used in limited or concealed ways. Our study extends the analysis of Canadian newspapers, drawing articles from six sources, to critically examine how aging persons with vision loss and AT were constructed, and the possibilities for technology use and occupation promoted and marginalized.

Methodology and Methods

Critical discourse analysis (CDA) provides a means to unpack how objects and subjects are constructed within texts, and to critically consider implications of discourses for “possibilities for being and doing” (Laliberte Rudman & Dennhardt, Reference Laliberte Rudman, Dennhardt, Nayar and Stanley2014, p. 138). Informed by critical theoretical perspectives, CDA seeks to understand and deconstruct discourse as a social practice embedded within power relations. Deconstruction involves looking beyond the surface features and content of texts to uncover and problematize underlying beliefs and assumptions (Ballinger & Cheek, Reference Ballinger, Cheek, Finlay and Ballinger2006). Thus, CDA aims to raise awareness of how social issues have come to be dominantly understood and addressed at individual to societal levels, with a focus on resulting exclusion and inequities.

Although there are multiple approaches to CDA, the approach used is always guided by specific critical theoretical perspectives (Fairclough, Reference Fairclough2013; Laliberte Rudman & Dennhardt, Reference Laliberte Rudman, Dennhardt, Nayar and Stanley2014). The present CDA, informed by critical disability and occupational perspectives, sought to unpack if and how ableist and ageist assumptions influenced how aging adults with vision loss and AT were dominantly constructed. A critical disability perspective conceptualizes disability as resulting from complex transactions of impairments and disabling environmental features (Hosking, Reference Hosking2008), countering a more dominant biomedical frame that locates disability within individual-level impairments and associated deficiencies (McGrath et al., Reference McGrath, Laliberte Rudman, Trentham, Polgar and Spafford2017). In turn, analysis attended to if and how disabilities experienced by aging subjects with vision loss were constructed in ways that promoted problem and solution frames focused on individual deficiencies tied to being “disabled” and “old”, or whether they also attended to social, cultural, economic, and other environmental features. We also attended to what characteristics of aging subjects were idealized and stigmatized, as well as how AT was positioned; for example, as enabling independence or as stigmatizing. We layered in a critical occupational perspective, specifically the concept of occupational possibilities (Laliberte Rudman, Reference Laliberte Rudman2010), to give particular attention to what forms of doing or occupations were promoted as ideal and possible through the use of AT for aging adults with vision loss, as well as what occupations were negated or never mentioned.

Data Collection

Newspaper articles were focused on, because Canadians of varying socio-economic statuses and genders access newspapers. Furthermore, newspapers are the most frequently accessed type of media by older Canadian adults (National Audience Databank, 2013; News Media Canada, 2018). The Vividata database was used to identify Canadian newspapers with the greatest readership of older adults, excluding those published in French. This resulted in the selection of six newspapers: The Toronto Star, Globe & Mail, National Post, The Toronto Sun, Vancouver Sun, and The Hamilton Spectator. All selected newspapers had significant coverage in the Factiva and Lexis-Nexis Academic databases. Search terms related to older adults, ARVL, and AT were used to conduct a search spanning the time period from January 1, 2000 to May 25, 2019, resulting in an initial sample of 7,289 newspaper articles.

A two-phase process of article selection was used, in which articles were randomly assigned to a group of six researchers and each article was screened by two researchers. The inclusion criteria initially included articles that: were written in English; addressed a type of ARVL (macular degeneration, diabetic retinopathy, and/or glaucoma); related to persons 55 years of age and older, “baby boomers”, and/or “older adults”; and addressed AT use. However, the criteria related to ARVL was broadened to include articles addressing vision loss attributed to or occurring with aging, as it was found that articles often did not incorporate diagnostic terms. Articles were excluded if the focus was on animals, other forms of impairment or disability, or juvenile vision loss, or if they were obituaries or movie/book reviews. The first phase, a title screen, resulted in a refined sample of 1,867 articles. The second phase, a full text screen, resulted in a final sample of 51 articles. As databases did not include visual images, microfilms of articles were collected as available in a library archive, with 31 articles having accompanying microfilms.

Data Analysis

In order to optimize rigour and coherence (Ballinger, Reference Ballinger, Finlay and Ballinger2006), data analysis followed recommendations put forth by Laliberte Rudman and Dennhardt (Reference Laliberte Rudman, Dennhardt, Nayar and Stanley2014) and explicitly incorporated guiding critical theoretical perspectives. Although described in three distinct phases, the process was, in fact, iterative and non-linear, including multiple readings of articles. Systematic documentation of analytical processes and emerging insights, as well as reflexive notes pertaining to reactions to articles, was conducted.

The first phase involved open reading of the articles and free note writing. Notes included first impressions and reactions to content, function, form, and visual elements. The second phase involved article assignment to three pairs of researchers for theory-informed reading in which focused reading and analytical note taking for each article was guided by a data analysis sheet informed by critical disability and occupational perspectives. For example, guiding questions included: what kind of assumptions about disability are integrated, what environmental barriers presenting challenges to occupations for aging persons with vision loss are addressed, what types of identity characteristics are presented as ideal/non-ideal for aging subjects, and what benefits/drawbacks are connected to AT use? This phase of analysis also included attention to linguistic features, such as common verbs, adjectives, and nouns. The third phase focused on cross-text analysis. During this stage, articles, along with their completed data analysis sheets, were compared with one another to investigate “similarities, variations, contrasts, repetitions, connections, contradictions, and absences in content, form and function across texts” (Laliberte Rudman & Dennhardt, Reference Laliberte Rudman, Dennhardt, Nayar and Stanley2014, p. 146). Iterative conduct of these three phases resulted in identification of key discursive threads.

Key Discursive Threads

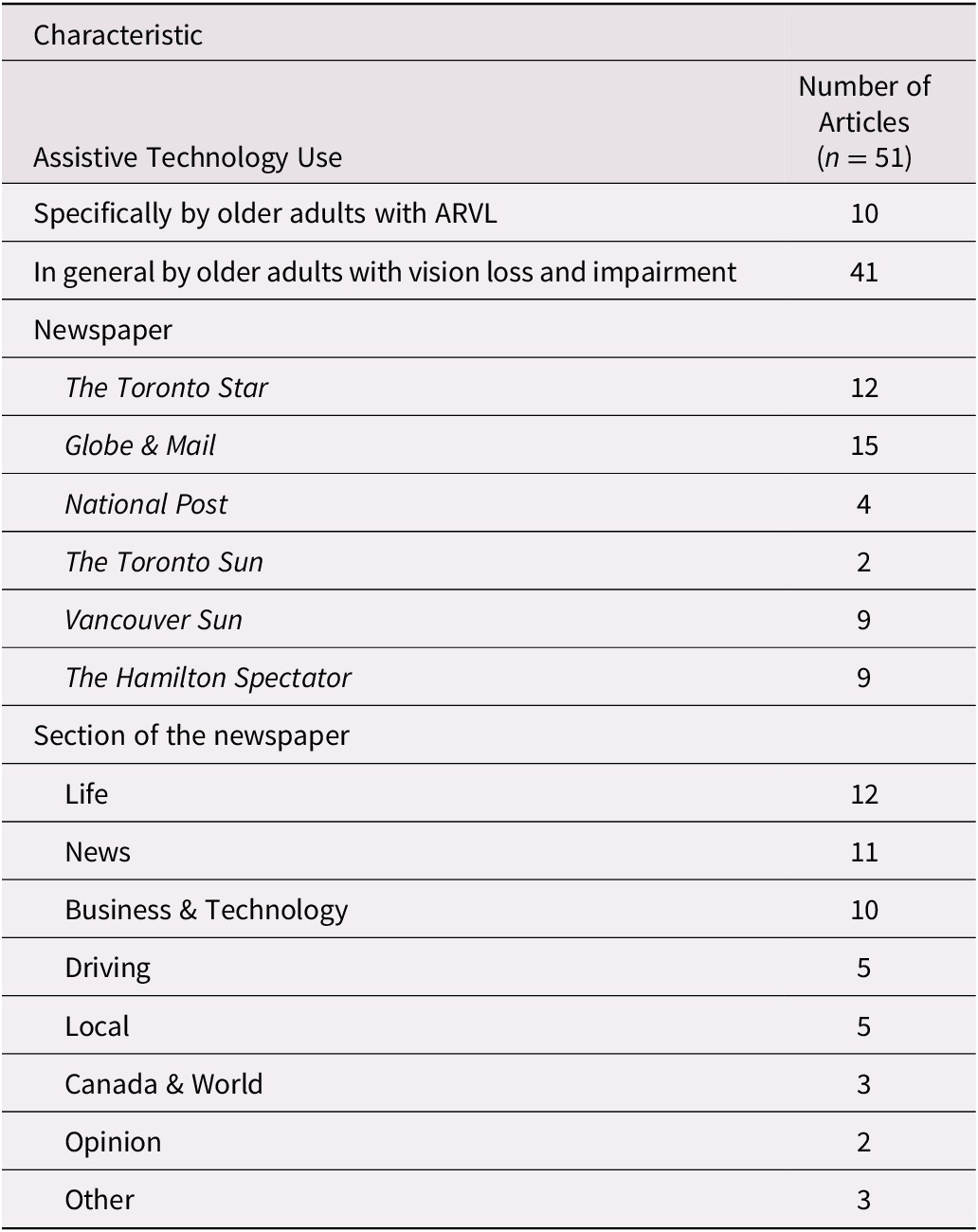

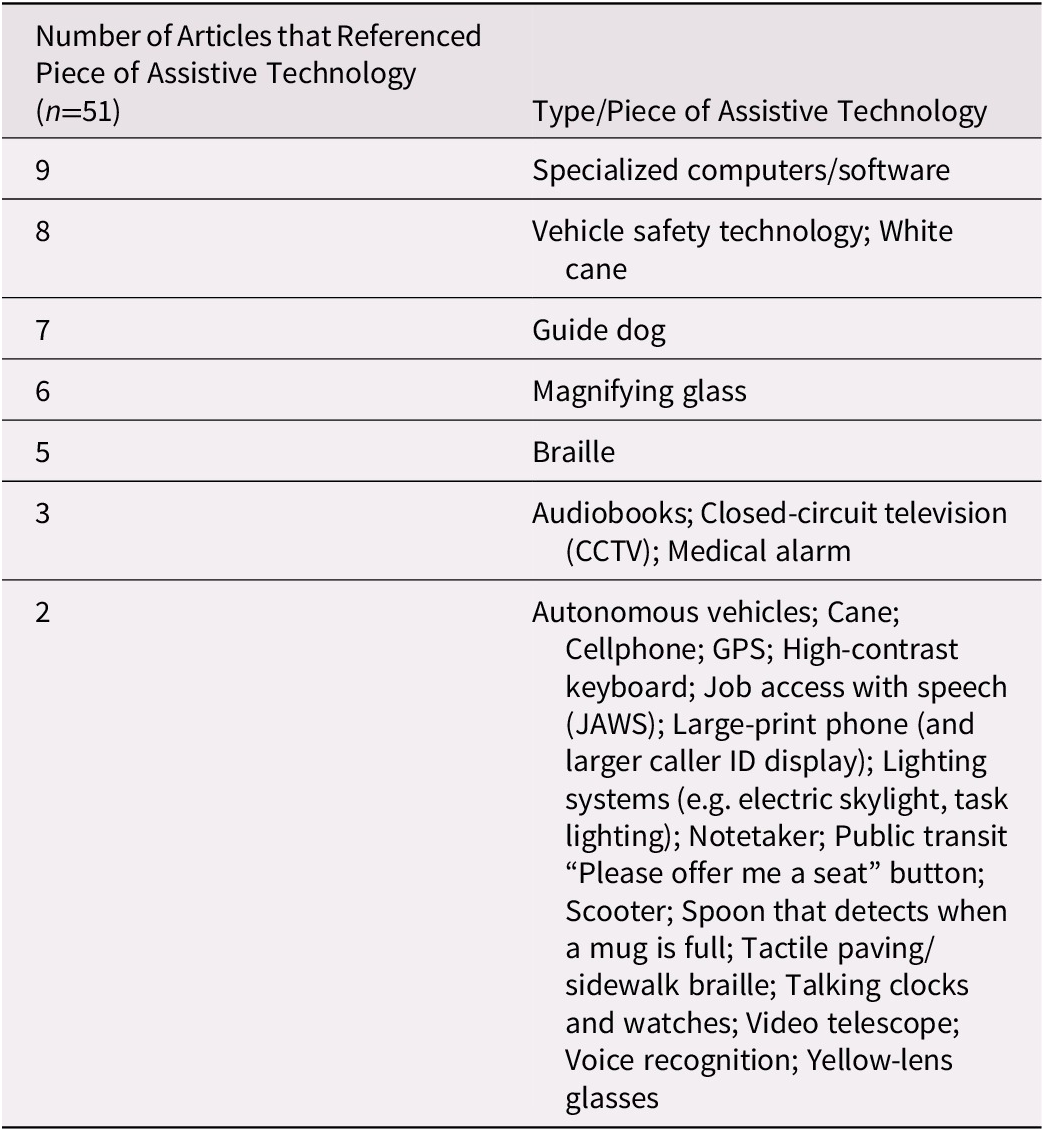

Descriptive characteristics of the 51 included articles are provided in Table 1. Most included articles were published in the Globe and Mail and The Toronto Star, and were found in the Life, News, and Business & Technology sections. As listed in Table 2, a wide range of types of AT were addressed in articles, with the five most common being specialized computers and software (e.g. Job Access with Speech [JAWS]), white canes, vehicle safety technology (e.g. parking sensors, blind spot warning systems, lane departure warning systems), guide dogs, and magnifying glasses.

Table 1. Characteristics of articles

Note. ARVL = age-related vision loss.

Table 2. Assistive technology presented in the newspaper articles

Note. Assistive technologies that were referenced by only one article are not included in this list.

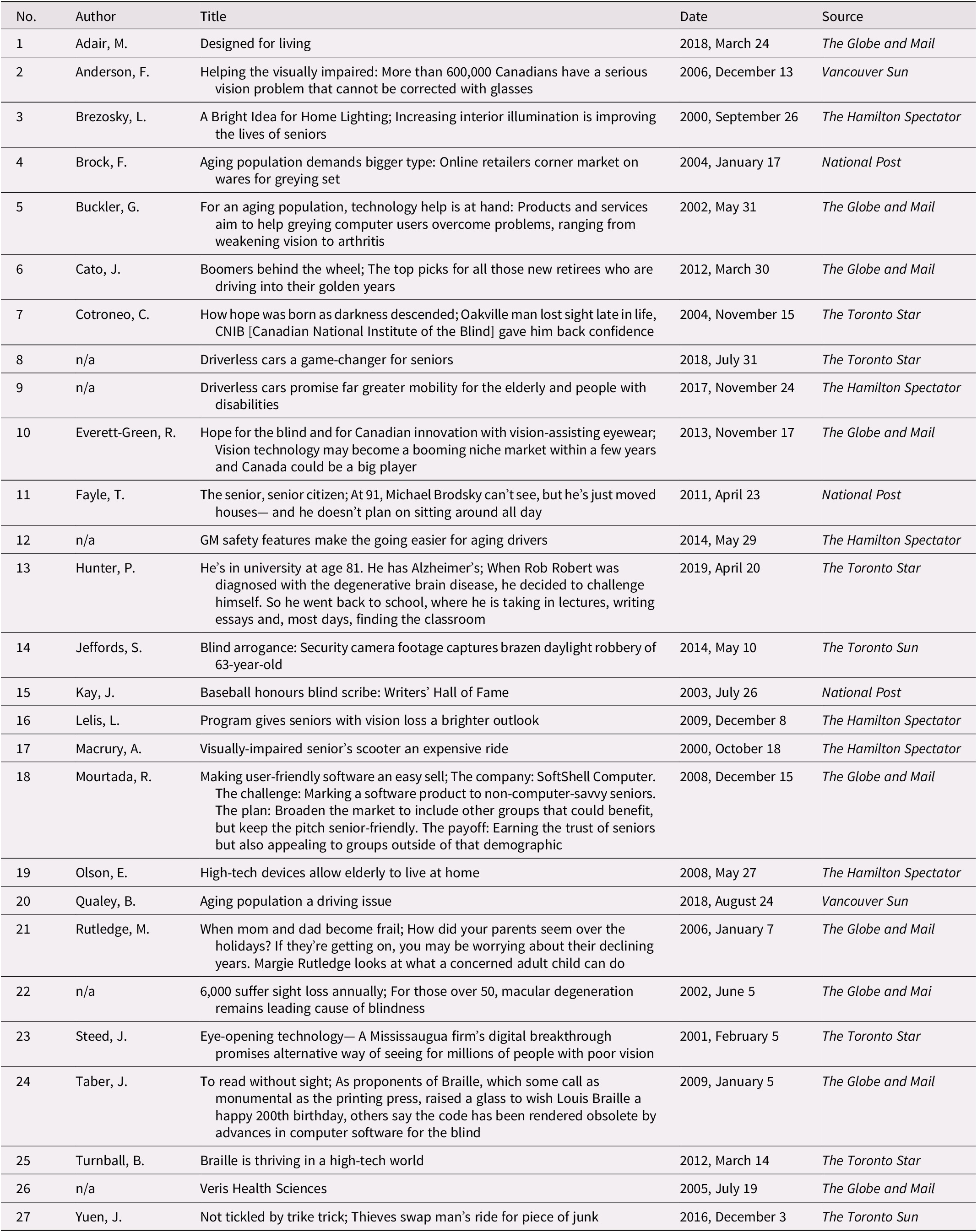

In total, four main discursive threads resulted from this CDA including: (1) vision loss framed as resulting in disability and tragedy, (2) assistive technology positioned as the means of maintaining independence, (3) occupations idealized as possible through assistive technology, and (4) assistive technology positioned as a consumer product. Representative excerpts and images are referenced by coded numbers (see Table 3, which identifies the referenced articles).

Table 3. Newspaper articles cited in the text

Vision loss framed as resulting in disability and tragedy

Consistent with a biomedical discourse on impairment as tragedy and loss (Clapton & Kendall, Reference Clapton and Kendall2002), older adults were dominantly constructed as suffering as a result of their vision loss, with this suffering encompassing loss of hope, feelings of fear and grief, and loss of capabilities and meaningful occupational engagement. Quotes from older adults with vision loss drawn into the articles often emphasized aspects of suffering and loss, such as “with the loss of full sight, normal life disappears” (22) and “there is just an overwhelming feeling of being lost and sad” (2). In another article, vison loss is framed as leading to a pervasive sense of fear: “It fell gradually, stealing his vision day by day, over three years, like someone drawing a curtain on the world he knew. ‘Traumatic, traumatic,’ is how he remembers those days in 1995. ‘Even though I heard about people going blind because of diabetes, I never thought it would happen to me…I was hoping that they could rescue me,’ said Heath, 63. But the blood vessels kept exploding, turning his eyes scarlet, battering his retina, ultimately leaving him completely blind. Heath fell prey to panic attacks, constantly fearing the day the lights went out forever” (7).

In many articles, older adults with vision loss were presented as suffering as a result of associated occupational losses. Consistent with a “tragedy” discourse on disability, there was an emphasis on how older adults had to “give up” meaningful activities, with a particular focus on driving: “They are too old to drive safely or cannot see well enough or otherwise have sound reason to fear climbing behind the wheel of a car” (9); “the Ministry of Transportation banning him from driving. His doctor diagnosed him with macular degeneration” (27); "I can no longer drive because of my poor vision…I paid him $550 [for a scooter] and took one home to try it out. I quickly realized it was no good for me, because of my poor vision” (17).

Employment was also depicted as an activity that had to be given up because of vision loss, particularly when vision was described to be a significant component of the job. One article illustrated the experience of a baseball reporter as his eyesight began to fail: "It was absolutely devastating…I cried. I felt sorry for myself. I was going to have to retire. How can you cover baseball if you can’t see?” (15). In another article, a woman diagnosed with macular degeneration was described as losing the ability to complete her work tasks as her vision deteriorated: “Over the years, Diana Dawson gradually lost the ability to see the details in the wedding dresses she had been sewing her whole life. At the bridal shop where she worked, she couldn’t focus on the beading, and as her vision continued to fade, she couldn’t see the fabric well enough to cut it” (16).

AT positioned as the means of maintaining independence

Consistent with a biomedical framing of disability, older adults with vision loss were often depicted as inherently lacking skill or ability. Several articles promoted AT as the solution that would enable older adults to overcome their deficits, maintain their safety, and be independent in performing their desired everyday activities. For example, one article asserted, “There are all kinds of low-vision aids and all kinds of techniques, from talking clocks and watches to large print items and library services that can assist in independent living, that can help those cope with AMD [age-related macular degeneration], even if nothing can be done medically” (22). Inspirational stories of aging adults with vision loss who were able to combat loss and dependency through AT were integrated in ways consistent with the broader societal valorization of independence. For example, one article told the story of a “white cane user” who recently moved into a new home and was continuing to live independently despite his age and vision loss. “His daughter suggested he get a moving company to do the packing for him—he is 91, after all, and blind, but he waved off the idea. ‘I wouldn’t know where anything was if I did that,’ he explains. ‘Easier to pack myself.’ Mr. Brodsky appreciates his son, daughter and grandchildren, but is determined to maintain his independence and control his own destiny. ‘Too much help creates helplessness,’ he says” (11). In the article that described the story of a baseball reporter who had been losing his eyesight for 2 years as mentioned, with the use of magnifying glasses and enlarged texts on his electronics, the 62-year-old remained in his profession and excelled, being voted into the writers’ wing of baseball’s Hall of Fame. Reds third baseman Aaron Boone said, regarding his story, “It’s turned into a sort of inspiration to a lot of people” (15). In these articles, older adults with vision loss were celebrated for their ability to perform their occupations with the use of AT and were portrayed as inspirational as they accepted the use of AT as the means to maintain their independence.

The recurring theme that independence is desirable for older adults with vision loss was further supported by articles that communicated how older adults wish to age in place. A geriatrician and director of regional geriatric programs of Toronto explained, “Seniors tell us they want to age at home with maximum function and quality of life” (21). An 88-year old woman with macular degeneration who did not want a live-in helper had “motion sensors and other devices” installed that allowed her to “live independently for longer” as her family could be alerted of any accidents or illnesses through this technology (19). AT was presented in several articles as allowing older adults with vision loss to remain in their preferred environment by increasing their independence and safety. In an article in which driverless vehicle technology was introduced, older adults were given the opportunity to age in place as a result of newfound freedom in mobility. “People would like to age in place and autonomous vehicles, if we get it right, will increase the freedom to age in place” (8).

AT was often promoted as a tool to enhance the safety of older adults with vision loss, with such safety connected to maintaining independence. One AT designer, knowing that “people with reduced vision use their fingers to orient themselves when cutting vegetables”, promoted safety and independence when cooking by “add[ing] a simple guard to a chef’s knife that makes knicks and cuts avoidable” (1). Another article promoted a new piece of technology, the VisAble Telescope, that can help older adults with ARVL navigate spaces, describing how it “enables people with low vision… to walk safely across the street” (23).

In contrast, a few articles highlighted the limitations of AT in promoting safety and independence, and instead presented AT as an undesirable product that signified disability and vulnerability. These articles were more often found in the News section of the newspaper and illustrated stories of older adults with vision loss who were involved in an unfortunate or negative event, such as being victims of theft. In these articles, AT was associated with stigma as it was a “symbol for blindness” (24) and inherent vulnerability. For example, one article entitled “Blind arrogance: Security camera footage captures brazen daylight robbery of 63-year-old” illustrated an incident in which a 63-year-old man, described as being legally blind, was believed to be a target for robbery because of his use of a white cane. He recalled: “‘I walk with this’…shaking the white cane with a bright red tip. ‘He must have been watching me’” (14). Although the man was utilizing a white cane to achieve independence in community mobilization, he was labelled as vulnerable and dependent because of his use of AT: “‘There is no defence for him, he needs help just to walk and get around’” (14).

Occupations idealized as possible through assistive technology

The texts that were examined presented AT as creating particular occupational possibilities for older adults with vision loss; that is, particular types of everyday activities, that aligned with the promotion of independence and the continuation or re-attainment of a “normal life”. Specifically, community mobility and taking care of oneself were emphasized as ideal or desirable occupations for older adults with vision loss to engage in with the support of AT.

Community mobility

The occupation of community mobility, presented in these texts, included navigating the physical environment, whether it be walking around the neighbourhood, taking public transportation, or continuing to drive. One man stated the challenges of mobilizing with vision loss, saying, “Once you get half-blind, you trust what little vision you have. You run into things because you’re still trying to use what little you have left” (7).

In such cases, AT was often offered as a solution for older adults with vision loss to better navigate spaces. AT that was mentioned as supporting community mobility included white canes, guide dogs, scooters, and other technology, such as a GPS, that allowed older adults with vision loss to drive with more ease. The texts often shared stories of individuals successfully navigating their spaces with the help of AT. One success story concerning a man with diabetic retinopathy shared how he is “often seen strolling through the neighbourhood, his cane wagging in front” (7). Another article pictured a man navigating a crosswalk with a white cane to guide himself (2). Other articles highlighted AT features designed to increase safety while driving, such as one article that addressed “active safety technologies, simple access to OnStar services and more spacious cabins” (12) as a means to make driving easier for aging drivers, including those with visual impairments.

Because of a lack of driving and reduced opportunities for community mobility for older adults with vision loss, other occupations were impeded. For example, the texts highlighted the negative implications for social inclusion if the occupation of driving and community mobility were taken away. “Mobility is closely related to loneliness. If you can’t get out of your dwelling in order to buy food or meet a friend for a coffee, then you’re talking about loneliness” (1). The texts asserted that with AT for community mobility, older adults would be “[benefited in numerous ways], including giving them the ability to travel to different places whether for social activity or for appointments” (8).

Taking care of oneself

Self-care was another recurring occupation that was presented as difficult for older adults with vision loss to engage in. AT for self-care included specialty magnifiers and large print or high contrast on electronics that enabled independent performance of activities of daily living (ADL) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL). For example, with the use of AT that increased interior lighting, functional tasks were improved for older adults with vision loss. For example, “Many tenants also rave about lights under kitchen counters that allow them to read recipes and medicine bottles. Even more compliment the lights in the showers” (3).

Some ATs were more elaborate. For example, one article advertised a hand-held telescope that uses “digital technology to enhance sight, with a zoom lens, wide viewing field and high magnification” that could allow older adults with vision loss to “read food and drug labels, look inside their refrigerators and cupboards, and generally carry on a normal life” (23). This same article further supported this discourse by providing readers with an image of a person using a magnifier to increase the size of the text on a prescription medicine bottle, and used bullet points within the article to list other AT devices that could help older adults with low vision to participate in their daily activities.

AT positioned as a consumer product

AT was often illustrated as a desirable consumer product for individuals with low vision. Several articles were found in the Business, Technology, or Driving sections of newspapers, and these articles were presented in a way that sounded similar to an advertisement for AT for older adults with vision loss. Articles referred to the growing aging population and used terms such as “a growing group of customers” (5) and “a huge and growing market” (23) to emphasize the increasing demand for AT. AT was described using statements such as “remarkable” and “special” (13), a “hot product” (10), “sexy”, “beautiful” and “simple” (1), “sophisticated” (25, 11), “stylish, well-designed and fun” (4), and “will help people stay independent and active” (4), largely focusing on the benefits of AT.

AT was often described as a solution to the functional deficits experienced by older adults with vision loss by the creators of AT, or businesses and entrepreneurs advertising AT products. For example, Blair Qualey, President and CEO of the New Car Dealers Association, described the features of a vehicle that older adults with vision problems would benefit from: “digital speedometer/heads-up displays feature large readouts that are easy to spot at a glance, even for those with vision problems” (20). Similarly in another article, John McMahon, President and Chief Executive Officer of Veris Health Sciences, and Michael Hines, President of Veris Ocular Sciences, described the benefits of AT developed through their company for individuals with age-related dry macular degeneration as “new technologies that enhance the health, quality of life and well-being of the patients it serves” (26). In each of these examples, such individuals were positioned as the “expert” who defined the benefits of AT for those with vision loss, whereas the voices of older adults with vision loss were limited, if not excluded altogether. If an image was included as part of these articles, it often was an image of the developers of AT or a representative of a business that endorsed the AT, not of older adults, as the consumers of the AT. For example, the article titled “Making user-friendly software an easy sell” featured a large photo of Stephen Beath and Raul Rupsingh, creators of SoftShell, showcasing the computer software they had created. This article also had a “What the experts say” section which included the opinions of the director of communications at Baycrest Foundation and the executive vice-president of Zoomer Media about how the creators of SoftShell could best market their technology to older adults, with no inclusion of the expertise of the older adults themselves (18).

Discussion

Although discourses addressing aging, vision loss, and AT do not determine how aging individuals will manage vision loss, they “provide morally-laden messages that shape people’s possibilities for being and acting” (Laliberte Rudman, Reference Laliberte Rudman2006, p.181) and influence what comes to be seen as appropriate societal and policy responses to the “problems” of aging (Laliberte Rudman, Reference Laliberte Rudman2006; Rozanova, Reference Rozanova2006). This critical examination of Canadian newspaper articles generated four dominant discursive threads related to the framing of disability and AT, the positioning of aging subjects with vision loss, and the ideals and occupations to be attained through AT. Consistent with a biomedical framing and ableist assumptions (McGrath et al., Reference McGrath, Laliberte Rudman, Trentham, Polgar and Spafford2017), vision loss was presented as resulting in disability and tragedy. Overall, the disability arising from vision loss was largely located in aging subjects’ bodies, with little attention paid to disabling environmental features. Consistent with ageism (Martinson & Berridge, Reference Martinson and Berridge2014), older adults with vision loss were depicted as “at risk” of becoming “old”, given their failing bodily capacity, with oldness marked by dependency, vulnerability, and the inability to carry on a “normal life” and age in place. AT was positioned as providing a solution to be taken up by individual aging adults with vision loss to successfully counter the tragic consequences of disability and their “at risk” bodies. In particular, AT was constructed as a means to enable independence. Consistent with the individualizing of responsibility for “aging well” characteristic of positive aging discourses (Laliberte Rudman, Reference Laliberte Rudman2006; Rozanova, Reference Rozanova2010), AT was commonly framed as a consumer product designed to meet aging adults’ needs. In concert, aging adults were positioned as consumers who should, and could, achieve independence, despite vision loss, through purchasing and using AT. Expertise was primarily located within professionals who designed and recommended AT. Relying on such expertise, ideal aging consumers were constructed as those who take up AT to support engagement in activities most crucial to maintaining independence and avoiding “oldness”.

Our findings both overlap with and extend those of previous analysis of constructions of aging in Canadian print media. Specifically, these findings affirm the valorization of independence in Western society, including in biomedical models of disability and discourses of positive aging. Critical disability theorists have raised concerns pertaining to how this valorization results in disabled persons being labeled as inherently deficient when “measured against the skills necessary to perform task indicative of the capacity of independent adulthood” (McGrath et al., Reference McGrath, Laliberte Rudman, Trentham, Polgar and Spafford2017, p. 1,933). In a similar manner, maintaining independence is a key marker of “aging well”, and those aging adults who fail to live up to this marker are also labeled as deficient (Martinson & Berridge, Reference Martinson and Berridge2014; Rozanova, Reference Rozanova2010). In the articles analyzed, aging adults with vision loss were presented as “at risk” of dependency, and AT, in turn, was presented as a means for individuals to manage this risk. Although the benefits to be potentially achieved through AT use in the lives of aging adults with AT are important, framing such benefits primarily in relation to the achievement of independence has significant limiting effects. This idealization of independence further perpetuates the stigma associated with dependency, creating few positive identity possibilities for aging adults who face bodily and environmental challenges that cannot be overcome through individual efforts alone (Laliberte Rudman, Reference Laliberte Rudman2006; Martinson & Berridge, Reference Martinson and Berridge2014; McGrath et al., Reference McGrath, Laliberte Rudman, Trentham, Polgar and Spafford2017). Also, the idealization of independence may detract from designing and using AT to support other outcomes, such as experiencing joy or maintaining social connections, which are essential to health and well-being. Ultimately, the continued dominance of discourses that idealize independence perpetuates both ableist and ageist attitudes and practices, further marginalizing aging adults whose life and bodily conditions necessitate interdependency and dependency (McGrath et al., Reference McGrath, Laliberte Rudman, Trentham, Polgar and Spafford2017). As highlighted in a recent commentary addressing the representation of older adults in public discourse during the COVID-19 pandemic, there is need to work against the ways that media perpetuates ageism, given implications for social exclusion and devaluing of older adults (Fraser et al., Reference Fraser, Legace, Bongue, Ndeye, Guyot and Bechard2020).

The valorization of independence also resulted in the occupational possibilities for aging adults with vision loss being narrowly confined in the discourse to occupations deemed crucial for maintaining independence and safety. Although positive aging discourses more broadly promote engagement in a range of occupations that defy negative stereotypes of aging and are held out as a means to achieve youthfulness, many of these occupations such as paid work, consumer-based leisure, and physically demanding exercise (Laliberte Rudman, Reference Laliberte Rudman2006; Laliberte Rudman et al., Reference Laliberte Rudman, Huot and Dennhardt2009; Rozanova, Reference Rozanova2010) were negated or excluded from the articles analyzed. As such, although AT is discursively positioned as offering up occupational possibilities for aging adults with vision loss, such possibilities were constrained in ways underpinned by ableist assumptions of what such adults, given their impairments, can and should do. Moreover, the focus on prioritizing everyday activities essential for maintaining independence aligns with the neoliberal mandate of “minimizing public support, and maximizing individual effort and personal responsibility” (Rozanova, Reference Rozanova2010, p. 220), as well as with a biomedical focus on locating problems and solutions at the level of the individual (McGrath et al., Reference McGrath, Laliberte Rudman, Trentham, Polgar and Spafford2017). This discursive message to focus on activities essential to independence also allies with the results of qualitative research conducted with aging adults with ARVL, which suggest that such aging adults often prioritize everyday activities essential to maintaining aging in place, safety, and caring for the self, progressively giving up community-based leisure, volunteering, and “non-essential” occupations (Desrosiers et al., Reference Desrosiers, Wanet-Defalque, Témisjian, Gresset, Dubois and Renaud2009; Laliberte Rudman et al., Reference Laliberte Rudman, Huot, Klinger, Leipert and Spafford2010; McGrath et al., Reference McGrath, Laliberte Rudman, Trentham, Polgar and Spafford2017). However, narrowing occupational engagement in these ways often has significant negative effects on key health-related outcomes, such as quality of life, social inclusion, and self-rated physical and mental health (Crews & Campbell, Reference Crews and Campbell2001; Horowitz, Reinhardt, & Boerner, Reference Horowitz, Reinhardt and Boerner2005; Mitchell & Bradley, Reference Mitchell and Bradley2006), pointing to the potential negative implications of this discursive thread.

Moreover, at the same time as idealizing independence, these findings show the persistence of negative stereotypes of aging adults with impairments as in need of help, in this case, help based on the expertise of those designing and recommending AT. Health care professionals, marketing teams, entrepreneurs, designers, and researchers were drawn in as experts on the needs of older adults with vision loss, and on how AT can be designed to meet these needs. When older adults’ voices were included, this was often to demonstrate their suffering or need for assistance, confirm their inabilities to maintain particular activities, or bear witness to the benefits of AT. Ageist constructions of older adults with impairments as passive, dependent, incapable, and lacking expertise has been found in other media analyses (Chen, Reference Chen2015; Fraser et al., Reference Fraser, Kenyon, Lagacé, Wittich and Southall2016). The continued persistence of such negative constructions of aging adults who have impairments can, in turn, both reflect and perpetuate practices that disempower older adults in various types of situations and settings (Fraser et al., Reference Fraser, Legace, Bongue, Ndeye, Guyot and Bechard2020). For example, studies addressing discharge planning practices in acute hospital settings suggest that the expertise of health care professionals is often prioritized over the knowledge and preferences of older adult patients (Moats, Reference Moats2006). As another example, a critical interpretive synthesis of research addressing rehabilitation research and practice pertaining to ARVL found that researchers and health professionals were positioned as having the expertise to most accurately determine risks and ascertain risk reduction strategies, whereas aging subjects were presented as unreliable, lacking accurate knowledge, and in need of education and guidance (Laliberte Rudman et al., Reference Laliberte Rudman, Egan, McGrath, Gardner, King and Ceci2016). This discursive positioning of older adults with vision loss, in turn, may create reluctance to seek help from “experts” regarding AT given the potential labeling, discrimination, and disempowerment that could be anticipated (Fraser et al., Reference Fraser, Kenyon, Lagacé, Wittich and Southall2016; Laliberte Rudman et al., Reference Laliberte Rudman, Egan, McGrath, Gardner, King and Ceci2016). In turn, as previously found in qualitative studies, aging adults with vision loss may choose to conceal or minimize the challenges they face in daily life as a means of reducing the risk of being viewed and treated as “old”, even when this results in restricting participation in valued occupations important to health, well-being, and social inclusion (Laliberte Rudman et al., Reference Laliberte Rudman, Huot, Klinger, Leipert and Spafford2010; McGrath et al., Reference McGrath, Laliberte Rudman, Trentham, Polgar and Spafford2017).

Extending beyond previous findings that emphasize how AT is constructed in ways that position it as stigmatizing (Fraser et al., Reference Fraser, Kenyon, Lagacé, Wittich and Southall2016), our analysis illustrates how ageist and ableist discourses emphasizing the fear of “oldness” and incapability intersect with the consumerist agenda promoted through positive aging discourses (Laliberte Rudman, Reference Laliberte Rudman2006). Positive aging discourses aligned with neoliberal downloading of risks and responsibilities onto aging individuals mark out consumption of age-defying products as a means to “buy oneself out of aging” (Rozanova, Reference Rozanova2010, p. 281). In the articles analyzed, although there was some attention given to the potential stigma and vulnerability associated with AT, such technology was more often positioned as providing an aesthetically pleasing and savvy means for aging consumers to buy out of the risk of becoming dependent. Although the shift to a consumerist framing may combat reluctance to use AT arising from its stigmatizing association with “oldness”, placing AT designed to support the health and well-being of aging persons with vision impairment in a consumerist frame may further support the neoliberal retreat of the state from funding programs and services that provide such AT. Moreover, critical attention needs to the paid to the social and health inequities that may be shaped and perpetuated if AT essential to health and well-being of aging adults is increasingly framed and accessed as a consumer product (Laliberte Rudman, Reference Laliberte Rudman2006).

Although we acknowledge that the findings of this study reflect discursive constructions in Canadian newspaper texts published in specific sources over a defined time period, the intent of critical discourse analysis is not to claim de-contextualized generalizability. Rather, the key intent is to deconstruct how an issue has come to be constructed within a specific social context, and to critically consider the implications of dominant constructions for the ways of thinking and acting made possible (Ballinger & Cheek, Reference Ballinger, Cheek, Finlay and Ballinger2006; Laliberte Rudman & Dennhardt, Reference Laliberte Rudman, Dennhardt, Nayar and Stanley2014). Our analysis raises concerns regarding how dominant discursive threads in newspaper texts addressing aging with vision loss and the use of AT perpetuate ageist and ableist attitudes and individualize the responsibility to work towards independence through consumption of AT. We also raise concerns regarding how a narrow focus on activities necessary for independence, tied to self-care and mobility, may bound the development of AT as well as occupational possibilities for aging persons with vision loss. Moreover, given the overlap between our discursive threads and discursive emphases found in several other studies addressing contemporary Canadian media, we contend that it is imperative that critical gerontologists continue to resist the stigmatization of disability and “oldness” and raise awareness of how the increasing individualization of the responsibility for “aging well” serves to perpetuate inequities in late life and justify continued state retreat from needed services and supports.

One key way forward, consistent with the emphases in critical disability scholarship (Charlton, Reference Charlton1998; Mmatli, Reference Mmatli2009), involves greater inclusion of older adults experiencing ARVL in research and development of AT. Involving older adults in processes of defining technology needs and designing technology can not only resist the stigmatization of oldness, but can open up possibilities for designing AT to support a greater range of occupations and outcomes relevant in the lives of older adults, and to enhance the uptake of AT (Astell et al., Reference Astell, Alm, Gowans, Ellis, Dye and Vaughan2009; Merkel & Kucharski, Reference Merkel and Kucharski2019).

Another key way forward involves resisting the valorization of independence and the individualization of disability that is pervasive not only within media, but within research addressing aging and disability more broadly. For example, informed by critical perspectives, gerontological research could increase its focus on the environmental forces that shape and perpetuate disability in late life, generating knowledge that can be used to further promote the creation of age-friendly environments as well as AT (McGrath & Corrado, Reference McGrath and Corrado2019; McGrath et al., Reference McGrath, Laliberte Rudman, Trentham, Polgar and Spafford2017). Moreover, such research could inform positive possibilities for doing and being in later life that are inclusive of interdependence, frailty, and living with risk (Egan et al., Reference Egan, Laliberte Rudman, Ceci, Kessler, McGrath and Gardner2017). Additional CDA studies, combined with attention to the implications of contemporary aging discourses for how aging has come to be understood and addressed at micro to macro levels, can raise critical awareness of how health, social, and occupational inequities are perpetuated amongst aging adults in relation to disability, socio-economic status, gender, and other social markers (Fraser et al., Reference Fraser, Legace, Bongue, Ndeye, Guyot and Bechard2020; Laliberte Rudman, Reference Laliberte Rudman2006; Rozanova, Reference Rozanova2010).

Conclusion

Vision loss in later life has a significant negative impact on the engagement in meaningful occupations by older adults. Although AT is often prescribed to older adults with vision loss, as it has the potential to improve performance of everyday activities, many never acquire AT, or they abandon it shortly after purchase to preserve a desired self-image, as AT is often seen as a marker of disability. Discourses in the media may influence the identities of older adults with vision loss and shape their attitudes towards AT use. This study generated four discursive threads related to aging, vision loss, and AT in Canadian newspapers: vision loss framed as resulting in disability and tragedy, AT positioned as the means of maintaining independence, occupations idealized as possible through AT, and AT positioned as a consumer product. These dominant discourses convey ways in which ageist and ableist societal views are embedded in media constructions of vision loss and AT, fail to present older adults with the lived experience of vision loss as experts, and shape inequities in occupational possibilities for older adults with vision loss.

Acknowledgements

We thank Rachel Chee, Emma Stevenson, and Elliot Tung for their contributions to this study, which was completed as part of a student research project for the Western University MScOT program.

Funding

This work was supported, in part, by funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council Insight Development Grant (Grant File #: 430-2017-00170).