Human beings have moved from place to place since time immemorial. The reasons for and the duration of these migrations put extraordinary stress on individuals and their families. Such stress may not be related to an increase in mental illness for all conditions or to the same extent across all migrant groups. In this paper, we provide an overview of some observations in the field of migration and mental health, hypothesise why some individuals and groups are more vulnerable to psychiatric conditions, and consider the impact of migration experiences on provision of services and care.

Migration

Migration is the process of social change whereby an individual moves from one cultural setting to another for the purposes of settling down either permanently or for a prolonged period. Such a shift can be for any number of reasons, commonly economic, political or educational betterment. The process is inevitably stressful and stress can lead to mental illness.

The preparation the migrants undertake, their acceptance by the new host community and the process of migration itself are some of the macro-factors in the origin of mental disorders. The micro-factors include personality traits, psychological robustness, cultural identity, and the social support and acceptance of others in their own ethnic group.

Migration to the UK has had many peaks. In the 20th century there were several: the first was the refugee influx during and surrounding the Second World War; the second occurred in the 1960s, when able-bodied young men and women were recruited from the former colonies in order to fill jobs created by the belated expansion of the post-war economy. A decade later, following the upheaval in East Africa, a large number of individuals migrated with their families, en masse.

Migrants can be classified using several different criteria – such as legal definition. There needs to be a distinction between actual settlers and migrant workers. The reasons for migration as defined by Rack (1982) include both ‘push’ and ‘pull’ factors. Settlers, as well as political exiles, asylum seekers and refugees, may well have to deal with very stringent legal procedures, which will test their psychological stamina. If there are conditions akin to war, refugees may even face rougher times. Factors like language, communication and social networks will play a role in the processes of dealing with initial adversity, settling down and assimilation.

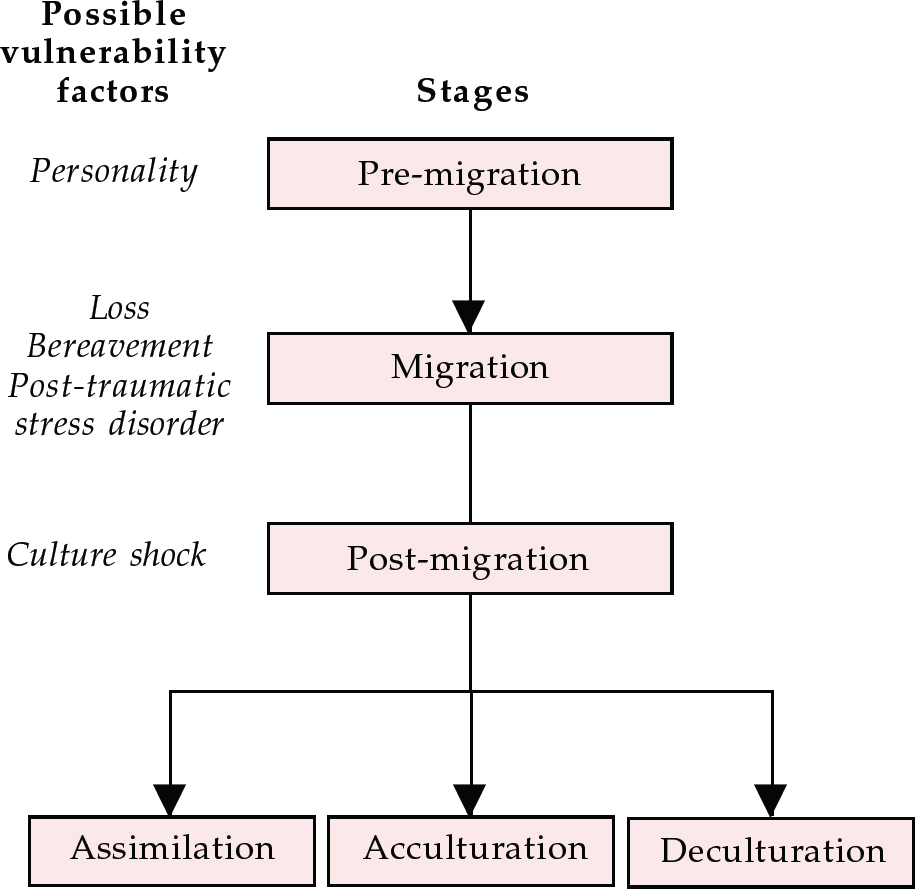

The migratory process can be seen as three stages. The first, pre-migration, is when the individuals decide to migrate and plan the move. The second involves the process of migration itself and the physical transition from one place to another, involving all the necessary psychological and social steps. The third stage, post-migration, is when the individuals deal with the social and cultural frameworks of the new society, learn new roles and become interested in transforming their group (see Fig. 1). Primary migrants may be followed by others. Once they have settled down and had children, the second generation is not a generation of migrants, but it will have some similar experiences in terms of cultural identity and stress.

We must advise a note of caution here. Although we are using the terms ‘migrant’, ‘migration’ and ‘psychological disorders’, these do not explain the heterogeneity inherent within each setting. Not all migrants have the same experiences or even the same reasons for migration and certainly the new societies' responses are not likely to be similar either.

We shall now review some of the key studies related to specific psychiatric conditions and highlight some key assessment and treatment strategies.

Schizophrenia

Ödegaard (1932) reported that migrant Norwegians to the USA had higher rates of schizophrenia (with a peak occurring 10–12 years post-migration). This study has been cited frequently as indicating that all migrant groups have high rates of schizophrenia. Sashidharan (1993) argues cogently that this model should not be applied to other ethnic minority groups in the UK without critical evaluation.

Several studies in the 1980s and 1990s showed that rates of schizophrenia were higher among migrant groups to the UK compared to native Whites (see Bhugra, 2000, for a review). Cochrane & Bal (1987) observed that migrants had higher rates of admission than the native population. Similar high rates of schizophrenia have been reported among the migrant populations from The Netherlands (Reference Selten and SijbenSelten & Sijben, 1994). Whether rates reported are from admission or community, some common themes emerge. First, incidence of schizophrenia in the African–Caribbean population is 2.5–14.6 times higher than in the White population (Reference Harrison, Owens and HoltonHarrison et al, 1988, Reference Harrison, Glazebrook and Brewin1997). Second, the rates among Asians are not as elevated and are not consistently high. King et al (1994) reported that the rates among Asians were no different from those in the White population from the same catchment area.

The key difference between these two studies was that, while King et al collected their data from an area where population density of Asians was thinner, Bhugra et al (1997) collected data from the London Borough of Ealing where, in the Southall catchment area, Asians form 50% of the population.

A number of hypotheses may be put forward to explain these high rates, some of which are listed in Box 1 and examined below. Hypotheses 1–4 were postulated by Cochrane & Bal (1987); Hypothesis 6 is discussed in the section Ethnic density v. social isolation.

Box 1. Six hypotheses for the higher incidence of schizophrenia in migrant groups

-

1 Sending countries have high rates of schizophrenia

-

2 People with schizophrenia are predisposed to migrate

-

3 Migration produces stress, which can initiate schizophrenia

-

4 Migrants are misdiagnosed with schizophrenia

-

5 Different symptom patterns are presented by migrants

-

6 Increased population density of ethnic migrant groups can show elevated rates of schizophrenia

Hypothesis 1: Factors in countries of origin

For a considerable period it was believed that the countries from which the individuals had migrated had high rates of schizophrenia, thereby suggesting a biological vulnerability leading to the illness. Until the 1990s very few studies had looked at the rates in sending countries, especially the Caribbean. With the Determinants of Outcome in Severe Mental Disorders (DOSMD) study (Reference Jablensky, Sartorius and ErnbergJablensky et al, 1992) and studies from Jamaica (Reference Hickling and Rodgers-JohnsonHickling & Rodgers-Johnson 1995), Trinidad (Reference Bhugra, Hilwig and HoseinBhugra et al, 1996) and Barbados (Reference Mahy, Mallett and LeffMahy et al, 1999), it was observed that rates of narrow-definition schizophrenia were not elevated compared with populations who had migrated. This suggests that biological causation is less likely, although biological vulnerability to environmental exposures cannot entirely be ruled out. Biological factors such as neurodevelopmental abnormalities, pregnancy and birth complications, and genetic vulnerability have not been reported consistently as having different prevalence in ethnic groups.

Hypothesis 2: Predisposition to migrate

The process of ‘selective’ migration has been put forward as a plausible hypothesis to explain the high incidence rates of schizophrenia among migrants, in that more vulnerable people are more restless and rootless. This superficially attractive hypothesis cannot be supported, on several accounts. First, high rates of schizophrenia are found in second generation rather than original migrants. Bhugra et al (1997) reported significantly different rates among older Asian females who were not primary migrants, thereby making it less likely that illness had predisposed them to move. Second, the physical process of migration and dealing with official immigration procedures is such a difficult and stressful task that individuals with schizophrenia are unlikely to complete it. Third, if this were the case, rates would be high among all migrant groups, which they are clearly not.

Hypothesis 3: Migratory stress

The key question here is whether migration itself acts as a stressor and produces elevated rates of schizophrenia, or whether the stressors occur later. If it were a straightforward association then rates of common mental disorders will be elevated among all migrant groups, which is clearly not the case (see below). Furthermore, as Ödegaard (1932) had demonstrated, rates of schizophrenia were elevated more than 10–12 years after migration, thus making it less likely that the actual process of migration is contributory. The finding of raised rates in the second generation but not in the first also argues against this.

However, the stress and chronic difficulties of living in societies where racism is present both at individual and institutional levels may well contribute to ongoing distress. These factors may also interact with social class, poverty, poor social capital, unemployment and poor housing. For example, Bhugra et al (1997) showed that 80% of the African–Caribbeans in their sample of cases of first-onset schizophrenia were unemployed, compared with 40% of Whites and Asians. However, such differential rates of unemployment and high rates of schizophrenia among African–Caribbeans may not be causally related and the high rates of unemployment cannot be explained away by general unemployment only.

Hypothesis 4: Misdiagnosis

The notion that misdiagnosis alone can explain the high rates of schizophrenia among the African–Caribbeans has caught the public and professional imaginations. However, this belief cannot be true. If misdiagnosis is the sole explanation, why is it that Asians are not misdiagnosed as readily, bearing in mind language differences? By using standardised definitions and assessments, as well as operational criteria in research, researchers should be able to reduce any discrepancy in diagnosis. As the same criteria are used in the sending countries, it would be likely that patients in those countries are being misdiagnosed too, and if they are not, why not?

Hypothesis 5: Symptom patterns

A key hypothesis that has been excluded from Cochrane & Bal's (1987) list is that of symptom patterns of schizophrenia. There is considerable evidence from DOSMD that there are indeed cultural differences between inception rates of narrow- and broad-definition schizophrenias (Reference Jablensky, Sartorius and ErnbergJablensky et al, 1992). Rates of narrow-definition schizophrenia vary across cultures within a very narrow band. It is possible that these two subtypes of schizophrenia and different migrant groups show different increases in specific symptoms.

Common mental disorders

The findings on prevalence of common mental disorders across different ethnic and migrant populations are equivocal. In the UK, Murray & Williams (1986) reported that Asian men were more likely to consult a general practitioner (GP) than White British men, although they reported fewer long-standing illnesses and less emotional distress. In contrast, no differences were found between Asian and White women. Cochrane & Stopes-Roe (1981) reported that rates of emotional disorders were lower among patients of Indian and Pakistani origins compared with Whites. Maveras & Bebbington (1988) reported that Greek Cypriots in London had higher rates of anxiety than White UK-born Londoners but had a similar rate to Greeks in Athens, whereas White Londoners had higher rates of depression. Gillam et al (1989) reported that White British people consulted a GP more frequently for GP-defined psychological problems and consultation rates for psychiatric problems were lowest in Caribbean and Asian women.

Nazroo (1997) reported that in a community survey, rates of anxiety were lower in Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi, Chinese and Caribbean women when compared with White British or White Irish females. Similarly, rates of depressive neurosis did not differ significantly across different ethnic groups. However, irrespective of clinical scores, Indian, Pakistani and Caribbean individuals were more likely to have visited a GP in the previous month. Jacob et al (1998) reported from their GP surgery sample that 30% of Asian women had common mental disorders, which were not dissimilar to those reported by White British women. On balance it would appear that rates of common mental disorders among ethnic minorities are not raised across all groups and both genders when compared with White groups. This would suggest that either these populations are psychologically robust or their expressions of distress are different.

Suicidal thoughts and deliberate self-harm

Nazroo (1997) reported that Irish, Caribbean and Pakistani men were more likely to consider that life was not worth living. Among women, however, there were no differences. On comparing these groups according to age and migration, Nazroo found that UK-born individuals (or migrants below the age of 11) of Caribbean, Indian or Pakistani origin were more likely to suffer from anxiety, depression and suicidal thoughts, although in some groups these differences were marginal.

Merrill & Owens (1986) reported that rates of attempted suicide were much higher among Asian women than their White counterparts. Bhugra et al (1999a, b) too found that Asian women aged 18–24 were 2.5 times more likely to attempt suicide. The authors of both studies attributed these findings to increased culture conflict. This culture conflict is attributed to a disparity between traditional and modern attitudes in oneself as well as social and gender role expectations from individuals' significant others.

Eating disorders

Although some studies, for example Mumford & Whitehouse (1988), have demonstrated that rates of bulimia nervosa are higher among Asian girls, as has Nasser (1986) for anorexia among Egyptian girls in London, these findings are not universal. Very little work has been done in the UK on eating disorders in other ethnic groups and both the studies cited above highlight the role of culture conflict in the causation of abnormal eating patterns. It is also possible that such conflict will be raised in geographical areas where ethnic density of the population is greater.

Post-traumatic stress disorder

Eisenbruch (1991) suggests that cultural bereavement, as experienced by refugees, is interlinked with symptoms and experiences of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Depending upon the type and urgency of migration and reasons for such an drastic step, PTSD can prove to be a significant finding across different ethnic groups and migrants. Further research is urgently required among refugees and migrants to understand their culture-specific experiences and explanations in order to deliver appropriate services.

Ethnic density v. social isolation

In common with Murphy (1977), Mintz & Schwartz (1964) and Faris & Denham (1960), we believe that ethnic density, that is, the density of the same ethnic group around an individual, plays a significant role in genesis and maintenance of some types of psychological distress. For example, rates of schizophrenia among Asians may be high in geographical areas where they are scattered and not so high where the Asian population is significant. Social support and low expressed emotion in an ethnically dense environment may act as protective factors in beginning and relapse (as the relapse rates are lower as well). Among African-Caribbeans, both the scattering of the population, and altered cultural and social identity and low self-esteem may contribute to high rates, low and delayed recognition and poor outcome. It would appear from Bhugra et al's (1997) data that African–Caribbean males are more likely to have been separated for longer than 4 years from their fathers and thus patterns of secure attachment and lower self-satisfaction and achievement may also play a role.

It is also likely that in ethnically dense populations, especially where the emphasis is on sociocentrism and collective responsibility, underlying culture conflict is more likely to take centre stage and produce high rates of attempted suicide and suicidal thoughts but not anxiety or depression. In such a setting, cultural identity, self-concept – including self-esteem – and social support are likely to play important roles.

Krupinski (1975) failed to find any impact of ethnic density on rates of psychiatric disorders among migrant groups in Australia. Rates of schizophrenia were lower among Dutch and British groups, but alcoholism was higher in British but rare among Italians and Greeks. Murphy (1968) posited that the rates of psychiatric disorders are lower among migrants in countries where immigrants constitute a larger proportion of the total population. Social change, assimilation and protection in cultural identity may prove to be significant factors.

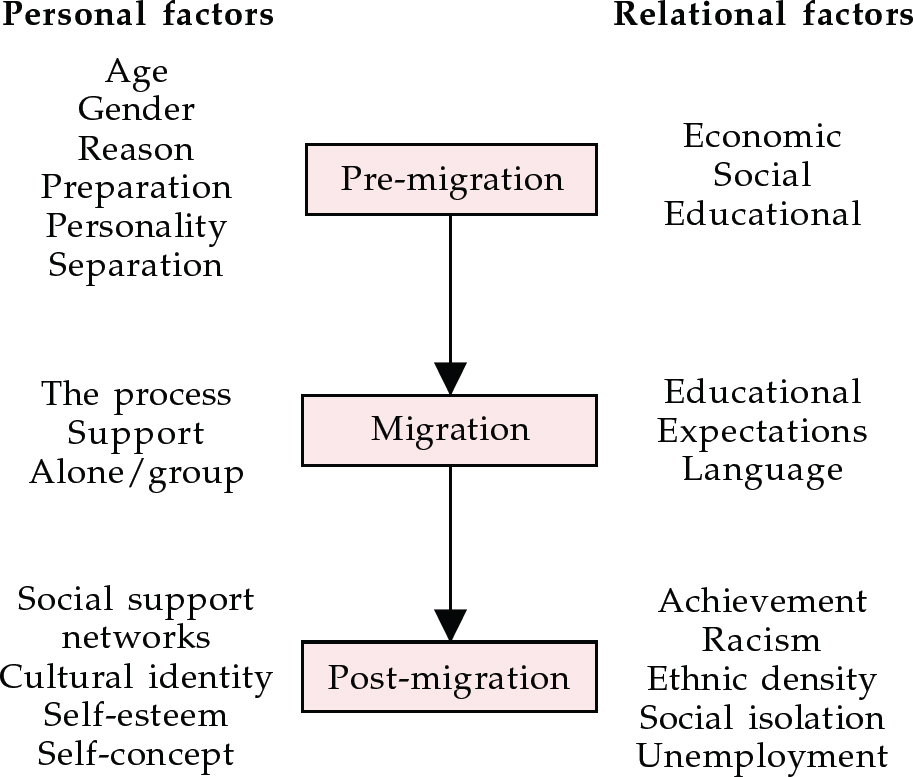

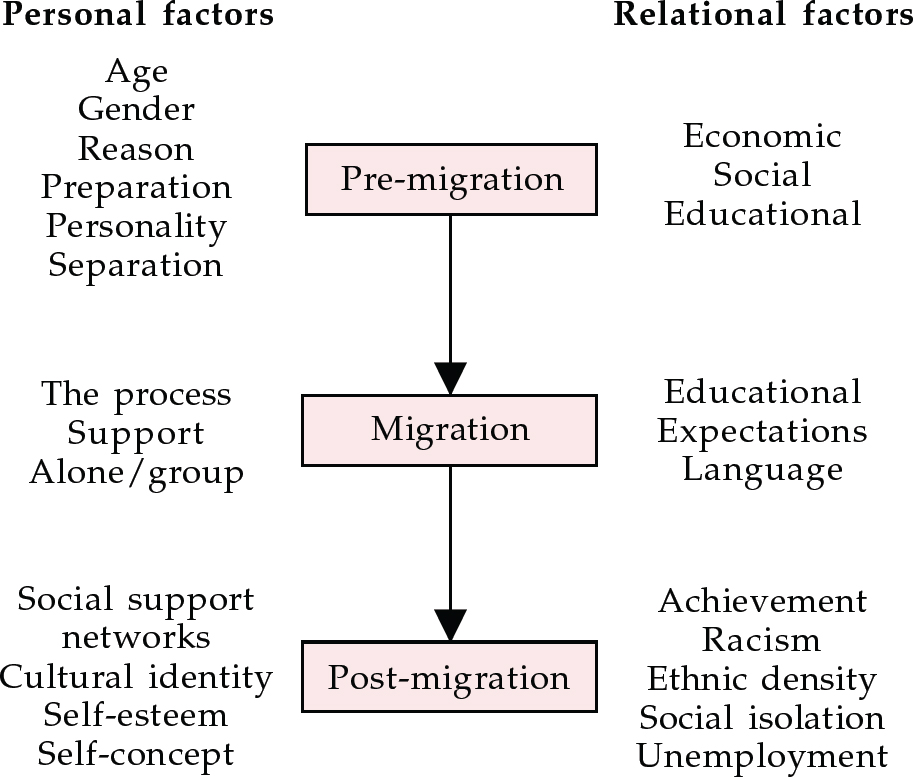

We propose that phases of migration, interlinked with significant life events and chronic ongoing difficulties, as well as personal factors (e.g. self-concept, self-esteem) and relational factors (e.g. social support, cultural identity), must be considered separately and continually (see Fig. 2). In the first phase of migration the psychological distress will be different from that experienced at a later date.

Implications for management

The implications of assessment for migrants have been discussed previously (Reference Bhugra and BhuiBhugra & Bhui, 1997). Duration since the migration, preparation prior to migration and post-migration assimilation, acceptance and deculturation can be the most destructive for the individual. Insidious ongoing racism, with both chronic difficulties and acute difficulties related to racial life events, can be particularly pathogenic in producing various psychiatric conditions. We hypothesise that this operates within a social context: if ethnic density is sparse, with a related paucity of support and other protective factors, the risk of illness will increase. It is very likely that such interactions can contribute not only to symptom formation, but also to persistence of symptoms (see Box 2).

Box 2. Factors to consider in assessing the mental health of migrants

-

• The patient's explanatory models of illness

-

• Carer/patient attitudes to illness

-

• Migration status

-

• Experiences of migration

-

• Migration phase

-

• Adjustment

-

• The host societies' attitudes

-

• Cultural identity

-

• Cultural conflict

-

• Ethnic density

-

• Achievements and expectations

In assessing and planning treatments the clinician must take into account the individual's experiences, expectations of treatment and explanatory models of illness. Assessment of illness, adaptation to illness and attitudes of individual patients and their carers towards prevention of future illness or plans for the future are key aspects if compliance is to improve.

Social support is related to social networks and the clinicians must access these. Kuo & Tsai (1986) suggest that distinction between voluntary migration (and uprooting) and forced resettlement is important. Thus, migration as an individual v. a group is bound to have a major impact on the individual and his or her social functioning and support. The effect of racial stratification combined with ethnic density will influence an individual's functioning.

Liu (1986) suggests that the attributes, as well as the structure, of network support systems have to be seen in the context of the cultural blueprint of a society. At the same time we think that clinicians must take into account the heterogeneity of networks in conjunction with the individual's personality, self-concept, self-esteem and self-sufficiency. The role of culture and the impact of migration on social structures is crucial in understanding social support and social networks. With increased ethnic density, social support may well be more easily available and may work to an individual's advantage in some sociocentric societies and yet may prove to be disadvantageous in others, especially if there is an underlying cultural conflict. The clinician must assess the quality of networks and social support, as well as the type of society and culture that the individuals come from.

Conclusions

Migration remains an enigma for the clinician because not all migrants go through the same experiences and or settle in similar social contexts. They do not all prepare in the same way and their reasons for migration are variable. The process of migration and subsequent cultural and social adjustment also play a key role in the mental health of the individual. Clinicians must take a range of these factors into account when assessing and planning intervention strategies aimed at the individual and his or her social context.

Multiple choice questions

-

1. Migration:

-

a can lead to increase in culture shock

-

b always causes high rates of schizophrenia

-

c can have different impact on different people

-

d can delay onset of mental illness

-

e is one uniform experience.

-

-

2. Regarding schizophrenia:

-

a there are high rates among African– Caribbeans

-

b there are higher rates among all immigrants compared to the native population

-

c high rates in immigrants can be attributed to high rates in the countries of origin

-

d high rates in immigrants are a direct result of stress of migration

-

e high rates can be explained solely by misdiagnosis.

-

-

3. Common mental disorders:

-

a are seen more commonly in all migrant groups

-

b are more common in Asian females than in their White counterparts

-

c can lead to increased admission rates in minorities

-

d can be associated with migration

-

e can cause increased attendance at GP surgeries.

-

-

4. Concerning attempted suicide:

-

a rates are higher among Asian females than White females

-

b rates of suicidal thoughts are higher among Irish males than native British males

-

c African–Caribbean females have high rates compared to Asian females

-

d rates in Asians are not related to mental illness

-

e culture conflict can produce high rates.

-

-

5. In migrants:

-

a social support may act as a protector

-

b voluntary migration may be associated with better social networks

-

c social support and networks should be assessed routinely

-

d adjustment should be assessed

-

e culture shock needs to be assessed.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | T | a | T | a | F | a | T | a | T |

| b | F | b | F | b | F | b | T | b | T |

| c | T | c | F | c | F | c | F | c | T |

| d | F | d | F | d | F | d | T | d | T |

| e | F | e | F | e | T | e | T | e | T |

Fig. 1 Stages of migration

Fig. 2 Factors in migration and psychological distress

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.