Introduction

Psychiatric disorders affect one in five people (Charlson et al., Reference Charlson, van Ommeren, Flaxman, Cornett, Whiteford and Saxena2019). The aetiology of psychiatric disorders involves interaction of genetic, environment and lifestyle behaviours (Kraemer et al., Reference Kraemer, Stice, Kazdin, Offord and Kupfer2001). Even though genetic components might be significant contributors to many psychiatric disease, increasing empirical evidence have shown that adverse early-life environment, starting in utero or even before, may increase the lifetime risk of mental health problems (Tegethoff et al., Reference Tegethoff, Greene, Olsen, Schaffner and Meinlschmidt2011). Research on prenatal origins of those diseases would provide important knowledge for developing more effective prevention strategies, which may open a new era of disease control for mental health problems (O'Donnell and Meaney, Reference O'Donnell and Meaney2017).

Migraine is the most common chronic neurovascular disorder, ranking the second leading cause of years of life with disability (Vos et al., Reference Vos, Abajobir, Abate, Abbafati, Abbas, Abd-Allah, Abdulkader, Abdulle, Abebo and Abera2017; Dodick, Reference Dodick2018). Women are three times more likely to experience migraine than men, and are predominantly affected during their childbearing years (Burch et al., Reference Burch, Rizzoli and Loder2018). There is growing concern of the long-term mental health problems in the children born to mothers with migraine (Evans et al., Reference Evans, Shipton and Keenan2005; Kaasbøll et al., Reference Kaasbøll, Lydersen and Indredavik2012; Güngen et al., Reference Güngen, Aras, Gül, Acar, Ayaz, Alagöz and Acar2017). Children of mothers with migraine had more psychological and behavioural problems that were assessed through questionnaires in several previous studies (Evans et al., Reference Evans, Shipton and Keenan2005; Kaasbøll et al., Reference Kaasbøll, Lydersen and Indredavik2012; Güngen et al., Reference Güngen, Aras, Gül, Acar, Ayaz, Alagöz and Acar2017). It was suggested that maternal migraine may affect offspring psychiatric disorders via altered intrauterine environment in the central nervous system (Burch, Reference Burch2020). If this hypothesis holds true, we should expect that maternal migraine would be associated with a higher risk of psychiatric disorders in offspring. Only one study examined maternal migraine and bipolar disorder in offspring (Sucksdorff et al., Reference Sucksdorff, Brown, Chudal, Heinimaa, Suominen and Sourander2016). To our knowledge, no research has provided a comprehensive evaluation of the mental health outcomes of these children exposed to maternal migraine.

We hypothesised that maternal migraine could affect the fetal brain development and consequently mental health in offspring throughout the lifespan (Gandal et al., Reference Gandal, Haney, Parikshak, Leppa, Ramaswami, Hartl, Schork, Appadurai, Buil and Werge2018). The aim of this study was to investigate the association of maternal migraine with any or specific psychiatric disorders in offspring, taking into account the timing of maternal migraine diagnosis and a number of other factors that may affect the association (McLaughlin et al., Reference McLaughlin, Gadermann, Hwang, Sampson, Al-Hamzawi, Andrade, Angermeyer, Benjet, Bromet and Bruffaerts2012; Skajaa et al., Reference Skajaa, Szepligeti, Xue, Sorensen, Ehrenstein, Eisele and Adelborg2019).

Methods

Study population

We conducted a nationwide cohort study using data from the Danish national registers (Lynge et al., Reference Lynge, Sandegaard and Rebolj2011; Mors et al., Reference Mors, Perto and Mortensen2011; Wallach Kildemoes et al., Reference Wallach Kildemoes, Toft Sørensen and Hallas2011; Schmidt et al., Reference Schmidt, Schmidt, Sandegaard, Ehrenstein, Pedersen and Sørensen2015; Bliddal et al., Reference Bliddal, Broe, Pottegard, Olsen and Langhoff-Roos2018). In Denmark, all live births have a unique personal identification number that permits an accurate linkage of individual-level data. We identified all singleton live births from 1 January 1978 to 31 December 2012 (n = 2 105 712) from the Danish Medical Birth Registry (Bliddal et al., Reference Bliddal, Broe, Pottegard, Olsen and Langhoff-Roos2018) and excluded 461 children who had missing or extreme gestational age (<154 days or >315 days), 86 children without information on sex, 28 611 children with chromosomal abnormalities and 6769 children without links to their fathers. The final analysis included 2 069 785 children. We followed them from birth until the date of the first diagnoses of any psychiatric disorders, emigration, death or end of follow-up (31 December 2016), whichever came first. The Danish Data Protection Agency and the Danish Health Data Authority approved this study.

Exposure

Information on maternal migraine before childbirth was obtained from the Danish National Patient Register (DNPR) and the Danish National Prescription Registry (Lynge et al., Reference Lynge, Sandegaard and Rebolj2011; Wallach Kildemoes et al., Reference Wallach Kildemoes, Toft Sørensen and Hallas2011). The DNPR contains data on hospital admissions since 1977 and visits to outpatient clinics since 1995. Diagnoses for migraine are defined according to the International Classification of Diseases, Eight Revision (ICD-8) (1973 to 1993) code: 346 and the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) (1994 and onwards) code: G43 (Schmidt et al., Reference Schmidt, Schmidt, Sandegaard, Ehrenstein, Pedersen and Sørensen2015; Adelborg et al., Reference Adelborg, Szépligeti, Holland-Bill, Ehrenstein, Horváth-Puhó, Henderson and Sørensen2018). A migraine case was also defined when the individual had at least two redeemed prescriptions for migraine-specific treatment (Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) codes: N02CC (triptans) and N02CA (ergotamine)) (Skajaa et al., Reference Skajaa, Szepligeti, Xue, Sorensen, Ehrenstein, Eisele and Adelborg2019). The index date of exposure was the date of the first diagnosis of migraine or the first date of the redeemed prescription, whichever came first.

The outcome of interest

Information on psychiatric disorders was obtained from the DNPR and the Danish Psychiatric Central Research Register (Mors et al., Reference Mors, Perto and Mortensen2011; Schmidt et al., Reference Schmidt, Schmidt, Sandegaard, Ehrenstein, Pedersen and Sørensen2015). Our primary outcome was the first diagnosis of a psychiatric disorder using ICD codes (ICD-8 codes from 1977 to 1993: 290–315; ICD-10 codes from 1994: F00-F99), which was further categorised into the following specific diagnostic groups: (1) schizophrenia and related disorders; (2) mood disorders; (3) neurotic, stress-related and somatoform disorders; (4) eating disorders; (5) specific personality disorders; (6) intellectual disability; (7) persasive developmental disorders; (8) behavioural and emotional disorders with onset usually occurring in childhood and adolescence (online Supplementary Table 1). When investigating the specific psychiatric disorders, we defined the date of onset as the first day of each specific psychiatric disorder diagnosis, irrespective of other previous psychiatric disorder diagnoses, if existed (Köhler-Forsberg et al., Reference Köhler-Forsberg, Petersen, Gasse, Mortensen, Dalsgaard, Yolken, Mors and Benros2019).

Covariates

Based on previous research (McGrath et al., Reference McGrath, Petersen, Agerbo, Mors, Mortensen and Pedersen2014; Nilsson et al., Reference Nilsson, Laursen, Hjorthøj, Thorup and Nordentoft2017), the following variables were considered as potential confounders: sex of the child (male, female), calendar period of birth (a 5-year interval during 1978–2012), parity (1, 2, or ⩾3), maternal age at birth (⩽25, 26–30, 31–35, ⩾36 years), paternal age at birth (⩽25, 26–30, 31–35, ⩾36 years), maternal country of origin (Denmark, other countries), maternal education level (0–9, 10–14, ⩾15 years), maternal cohabitation status (yes, no), maternal psychiatric disorder history (yes, no), paternal psychiatric disorder history (yes, no) and maternal cardiovascular disease (ICD-8 codes: 390–459; ICD-10 codes: I00-I78) (yes, no). The information for maternal education and origin of country was obtained from the Danish Integrated Database for Longitudinal Labor Market Research (Petersson et al., Reference Petersson, Baadsgaard and Thygesen2011).

Statistical analysis

We used Cox proportional hazards regression model to estimate the hazard ratio (HR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) for the association of maternal migraine with the risk of any or specific psychiatric disorders in offspring. Treating deaths from causes other than psychiatric disorders as competing events, we performed competing risk analysis to estimate cumulative incidences in exposed and unexposed offspring.

In model 1, we adjusted for sex and calendar year of birth. In model 2, we additionally adjusted for parity, parental age at birth, maternal education level, maternal income, maternal origin, maternal cohabitation, paternal migraine, parental psychiatric disorders before the childbirth and maternal cardiovascular disease. In addition, we tested whether the association between maternal migraine and the risk of psychiatric disorders in offspring varied by the sex of the child. We also separated the analyses according to offspring's attained age of psychiatric disorders. Age groups were set using cut-off points that captured potentially relevant development periods: 0–9 years (childhood), 10–18 years (adolescence) and > = 19 years (early adulthood) (Svahn et al., Reference Svahn, Hargreave, Nielsen, Plessen, Jensen, Kjaer and Jensen2015).

As migraine is a chronic disease and there might be a lag in time for diagnosis (Weatherall, Reference Weatherall2015), we took into consideration the timing of diagnosis (diagnosis before the childbirth, < = 2 years after the childbirth, 2–5 years after the childbirth, 5–10 years after the childbirth and >10 years after the childbirth) in separate analyses. We explored whether the risk for psychiatric disorders was different among children born to mothers with the following a priori defined mutually exclusive categories: no migraine and psychiatric disorders (referent), migraine, psychiatric disorders and migraine with psychiatric disorders (the joint effect).

We did several sensitivity analyses. First, in order to examine potential mediating effects of neonatal complications (Higgins et al., Reference Higgins, Birnie, Chambers, Wilson, Caes, Clark, Lynch, Stinson and Campbell-Yeo2015), we performed the analyses after excluding children with preterm birth (<37 gestation weeks), low birth weight (<2500 g) and low Apgar score at 5 min (<7), to see whether the associations would be changed significantly, compared to those overall estimates. Second, due to the change on ICD codes (ICD-10 was adopted since 1994 in Denmark) and the migraine identification strategy (both outpatient diagnosis and prescription registry were available since 1995), we restricted the analysis to offspring born after 1996. Third, owing to the availability of data on maternal smoking (since 1991) and maternal pregnancy body mass index (since 2004), we restricted subanalyses to offspring born after 1991 and 2004, respectively. Fourth, to deal with the problems of missing values on covariates (i.e. maternal education level and cohabitation status), we consequently applied multiple imputation procedure by chained equations to impute ten replications to handle missing values of the confounders. Fifth, to capture the effect of migraine episodes during pregnancy, we additionally performed the analyses by further dividing exposure time window into two periods: prior to index prganncy and during index pregnancy. Lastly, to better evaluate the mediation effect, we conducted a mediation analysis to determine the proportion of the association between maternal migraine and psychiatric disorders in offspring that was mediated by the potential mediators (preterm birth, low birth weight and low Apgar score at 5 min). The mediators were assessed through multivariable logistic regression models of the outcome and the mediators; these results were then combined to estimate direct and indirect effects (via the mediators), adjusted for all the covariates as in model 2 (VanderWeele, Reference VanderWeele2016; Kim and VanderWeele, Reference Kim and VanderWeele2019). This mediation method assume that the covariates adjusted could adequately control exposure-outcome, mediator-outcome and exposure-mediator confounding (VanderWeele, Reference VanderWeele2016). The proportion mediated was calculated as log (natural indirect relationship)/log (total relationship). The mediation analyses were conducted using the PARAMED package in STATA. All statistical analyses were performed using STATA, version 15.1 (StataCorp).

Results

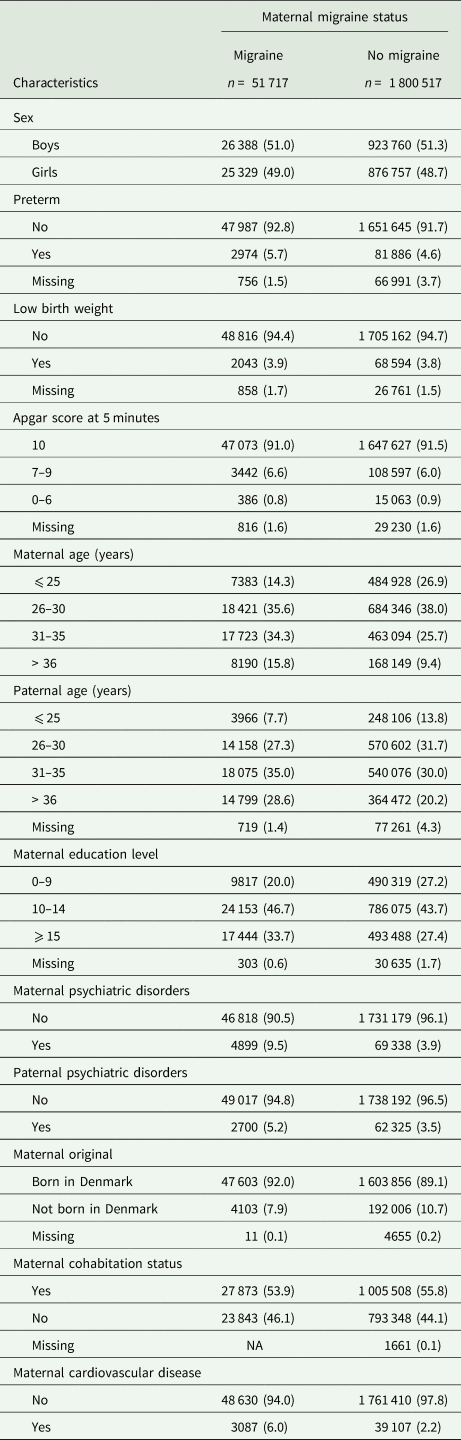

Among 2 069 785 participants, 51 717 (2.5%) were born to mothers with migraine. The proportion of offspring born to mothers diagnosed with migraine increased over time (online Supplementary Fig. S1). Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of children in the exposed and unexposed groups. Compared with unexposed offspring, exposed offspring were more likely to be born preterm, had low birth weight and older parents. Mothers of exposed offspring tended to have a higher level of education, a higher prevalence of comorbid psychiatric disorders or cardiovascular diseases.

Table 1. Characteristics of the study population born between 1978 and 2012 at birth according to maternal migraine status

Expresses as frequency (percentage); NA indicates less than three.

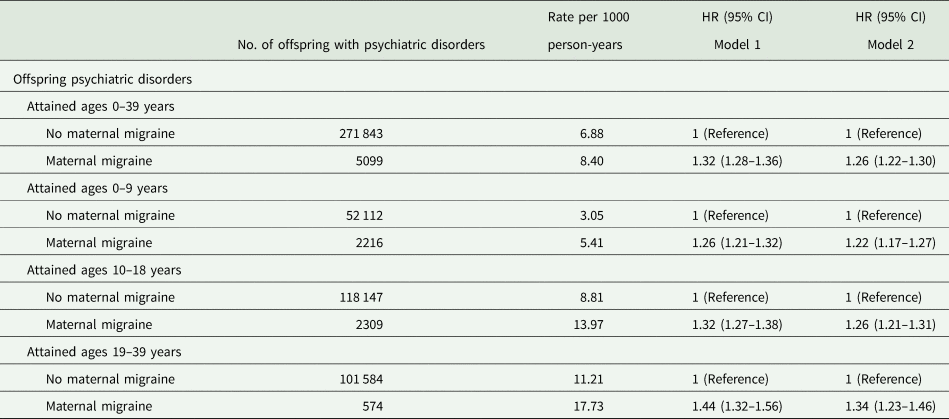

The median follow-up time was 19 years (interquartile range: 11–27 years). 277 063 (13.4%) were diagnosed as having any psychiatric disorders. The cumulative incidence of psychiatric disorders was 38.4% (95% CI, 34.4–43.4) for the exposed offspring and 26.2% (95% CI, 26.0–26.4) for the unexposed offspring (Fig. 1). The crude incidence rates of any psychiatric disroders were 8.40 and 6.88 per 1000 person-years among offspring of mothers with migraine and without migraine, respectively. Compared with the unexposed offspring, exposed offspring had a 26% increased risk of any psychiatric disorders (HR,1.26; 95% CI, 1.22–1.30). There was a tendency that HRs increased with age, with the highest HR (1.34; 95% CI, 1.23–1.46) observed in the early adulthood (Table 2). Stratification by sex of the offspring did not indicate any significant differences (online Supplementary Table 2).

Fig. 1. Cumulative incidence of overall psychiatric disorders among offspring exposed versus unexposed to maternal migraine.

Table 2. Incidence rate and HRs of all psychiatric disorders in offspring according to maternal migraine status

Model 1 adjusted for sex, birth year; Model 2 additionally adjusted for parity, maternal characteristic (age, education level, origin, cohabitation, cardiovascular diseases), paternal age, paternal migraine and parental psychiatric disorders before the childbirth.

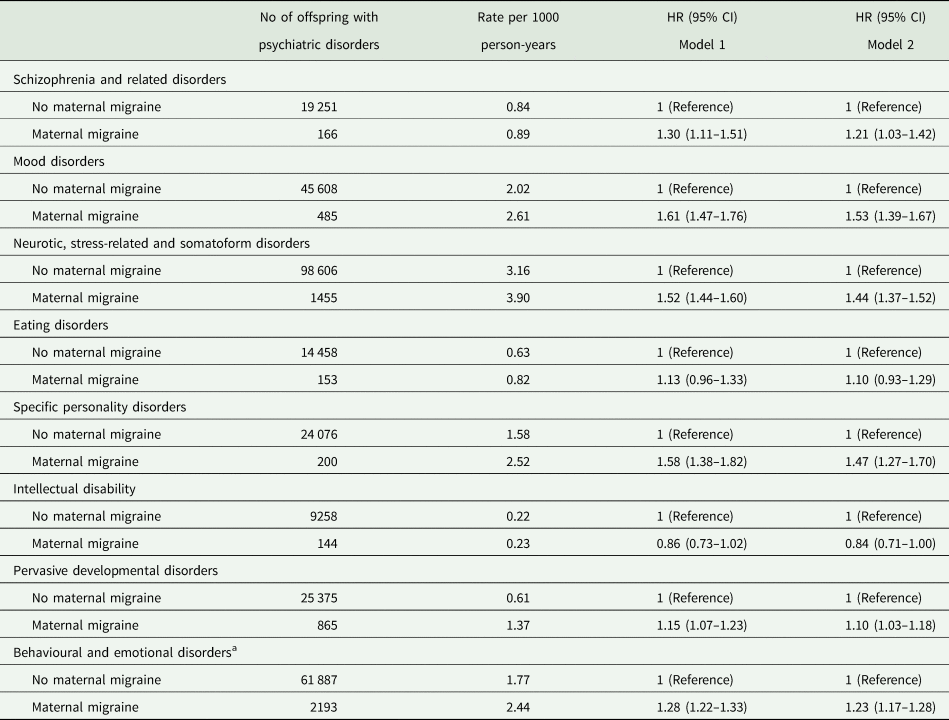

Maternal migraine was associated with most of the specific psychiatric disorders in offspring, for example mood disorders (HR, 1.53; 95% CI, 1.39–1.67), neurotic, stress-related and somatoform disorders (HR, 1.44; 95% CI, 1.37–1.52) and specific personality disorders (HR, 1.47; 95% CI, 1.27–1.70). Maternal migraine was also associated with an increased risk of behavioural and emotional disorders with onset usually during childhood and adolescence (HR, 1.23; 95% CI, 1.17–1.28). Maternal migraine was not associated with intellectual disability (HR, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.71–1.00) or eating disorders (HR, 1.10; 95% CI, 0.93–1.29) in offspring (Table 3).

Table 3. Incidence rate and HR of specific psychiatric disorders in offspring according to maternal migraine status

a Behavioural and emotional disorders with onset usually occurring in childhood and adolescence; Model 1 adjusted for sex, birth year; Model 2 additionally adjusted for parity, maternal characteristic (age, education level, origin, cohabitation, cardiovascular diseases), paternal age, parental psychiatric disorders before the childbirth.

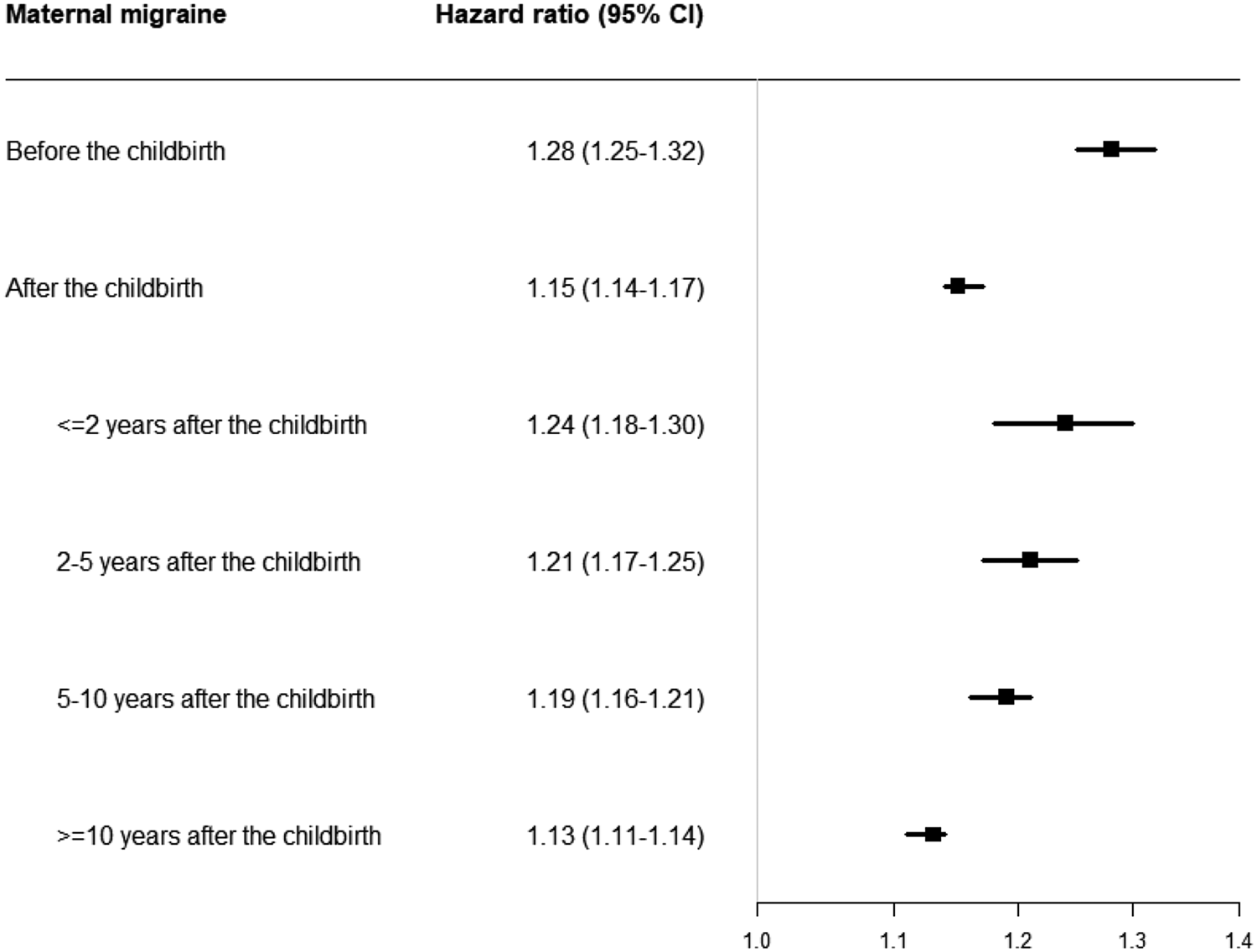

We also observed associations between maternal migraine diagnosed after the childbirth and psychiatric disorders in offspring (HR, 1.15; 95% CI, 1.14–1.17). The overall HR is 1.24 (95% CI, 1.18–1.30) when the mother was diagnosed with migraine within 2 years after the childbirth, which is similar to the HR for prenatal exposure. But the HRs decreased over time in offspring of mothers diagnosed migraine within 2–5 years after the childbirth (HR, 1.21; 95% CI, 1.17–1.25), 5–10 years after the childbirth (HR, 1.19; 95% CI, 1.16–1.21) and more than 10 years after the childbirth (HR, 1.13; 95% CI, 1.11–1.14) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Hazard ratio and 95% CI for overall psychiatric disorders according to the timing of maternal migraine diagnosed.

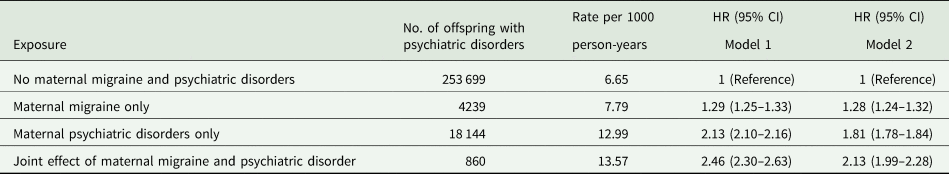

The highest overall risk of psychiatric disorders was observed in offspring of mothers with both migraine and comorbid psychiatric disroders (HR, 2.13; 95% CI, 1.99–2.28), comparing to offspring of mothers with migraine only (HR, 1.28; 95% CI, 1.24–1.32) (Table 4).

Table 4. Joint effect of maternal migraine and maternal psychiatric disorders before the childbirth on psychiatric disorders in offspring

Model 1 adjusted for sex, birth year; Model 2 additionally adjusted for parity, maternal characteristic (age, education level, origin, cohabitation, cardiovascular diseases), paternal age, paternal psychiatric disorders before the childbirth.

When excluding offspring with adverse birth outcomes such as preterm birth, low birth weight and low Apgar score, the estimates remained unchanged (online Supplementary Table 3). Similar associations were observed in the analyses restricted to offspring born after 1991, 1996 or 2004, respectively, and when we use the multiple imputation for missing values of the covariates (online Supplementary Tables 4–7). We observed that the associations between maternal migraine and psychiatric disorders in offspring were similar for maternal migraine diagnosed prior to the index pregnancy and diagnosed during the index pregnancy (online Supplementary Table 8). Adverse birth outcomes probably accounted for only a very small proportion (0.10–1.95%) of the association between maternal migraine and risk of psychiatric disorders (online Supplementary Table 9).

Discussion

In this large population-based cohort study, we found that maternal migraine was associated with an increased risk of any psychiatric disorders in offspring from childhood to early adulthood. Prenatal exposure to maternal migraine was associated with most specific psychiatric disorders, in particular, mood disorders, neurotic, stress-related and somatoform disorders and personality disorders. The highest risk of psychiatric disorders was observed in offspring of mothers with migraine and comorbid psychiatric disorders before childbirth.

Interpretation of results and comparison with other studies

To our knowledge, the association between maternal migraine and risk of psychiatric disorders in offspring has only been investigated in a Finnish Prenatal study of Bipolar disorders (FIPS-B), in which a 1.5-fold risk of bipoloar disorders in offspring was reported (Sucksdorff et al., Reference Sucksdorff, Brown, Chudal, Heinimaa, Suominen and Sourander2016). Consistently, we observed a similar magnitude of association between maternal migraine and mood disorders (including bipolar disorder) in offspring. However, in the Finnish study the information on psychiatric disorders was only available on bipolar disorders (Sucksdorff et al., Reference Sucksdorff, Brown, Chudal, Heinimaa, Suominen and Sourander2016). To our knowledge, our study provided the novel evidence that offspring of mothers with migraine tended to be at an increased risk of any psychiatric disorders, persisting from childhood into early adulthood. Maternal migraine may lead to hypothalamic−pituitary−adrenal dysfunction (Galletti et al., Reference Galletti, Cupini, Corbelli, Calabresi and Sarchielli2009), fluctuating hormone and oxidative stress (Bernecker et al., Reference Bernecker, Ragginer, Fauler, Horejsi, Möller, Zelzer, Lechner, Wallner-Blazek, Weiss and Fazekas2011; Aggarwal et al., Reference Aggarwal, Puri and Puri2012; Neri et al., Reference Neri, Frustaci, Milic, Valdiglesias, Fini, Bonassi and Barbanti2015), which can result in suboptimal intrauterine environment. Changes in the intrauterine environment could have a long-lasting effect on fetal brain development and, thus, increase the susceptibility to psychiatric disorders over the lifespan (Weinstock, Reference Weinstock2005; O'Donnell and Meaney, Reference O'Donnell and Meaney2017). Our study showed that maternal migraine diagnosed after the childbirth, especially diagnosed with migraine within 2 years after the childbirth, was associated with overall increased risk of psychiatric disorders in offspring. This is plausible because migraine may already be present for a period of time before the diagnosis (Wessman et al., Reference Wessman, Terwindt, Kaunisto, Palotie and Ophoff2007). As expected, the effect sizes associated postnatal exposure to maternal migraine decreased over time, supporting the programming effect of intrauterine environment on psychiatric disorders. On the other hand, we could not rule out the possibility that the observed association could be partly explained by the shared environmental risk factors (Sucksdorff et al., Reference Sucksdorff, Brown, Chudal, Heinimaa, Suominen and Sourander2016).

Furthermore, we also observed that maternal migraine was associated with increased risks of most subtypes of psychiatric disorders in offspring, for example, mood disorders, neurotic, stress-related and somatoform disorders. Different types of psychiatric disorders may share common pathogenic mechanisms (Insel and Wang, Reference Insel and Wang2010). For example, similar high level of transcriptomic overlap has been observed among mood disorders, personliaity disorders and pervasive developmental disorders (Gandal et al., Reference Gandal, Haney, Parikshak, Leppa, Ramaswami, Hartl, Schork, Appadurai, Buil and Werge2018). Genome-wide analysis studies have also revealed substantial genetic overlap among different psychiatric disorders (Anttila et al., Reference Anttila, Bulik-Sullivan, Finucane, Walters, Bras, Duncan, Escott-Price, Falcone, Gormley and Malik2018; Martin et al., Reference Martin, Taylor and Lichtenstein2018). Moreover, shared neurocognitive endophenotypes, such as deficits in executive function, processing speed and working memory, have been described in most psychiatric disroders (McTeague et al., Reference McTeague, Goodkind and Etkin2016).

We observed a two-fold increased risk of psychiatric disorders in offspring of mothers with both migraine and comorbid psychiatric disorders before the childbirth. The FIPS-B study also reported that the greatest risk was observed in offspring of parents with comorbid migraine and bipolar disorders (Sucksdorff et al., Reference Sucksdorff, Brown, Chudal, Heinimaa, Suominen and Sourander2016). Even if the biological mechanism of coexisting maternal migraine and psychiatric disorders during pregnancy is unknown, genetic component can contribute to the highest incidence rate of psychiatric disorders in offspring (Wessman et al., Reference Wessman, Terwindt, Kaunisto, Palotie and Ophoff2007). Another possible explanation could be that mothers with co-morbid migraine and psychiatric disorders have a higher level of psychological stress (Minen et al., Reference Minen, De Dhaem, Van Diest, Powers, Schwedt, Lipton and Silbersweig2016). As a result, offspring may be exposed to more severe psychological stress in utero, which is associated with an increased risk of psychiatric disorders (Tegethoff et al., Reference Tegethoff, Greene, Olsen, Schaffner and Meinlschmidt2011; MacKinnon et al., Reference MacKinnon, Kingsbury, Mahedy, Evans and Colman2018). Additionally, if the women diagnosed with migraine before the childbirth, she may exhibit increased circulating concentrations of inflammatory markers and could be aggravated by psychiatric disorders (Vanmolkot and De Hoon, Reference Vanmolkot and De Hoon2007; Saunders et al., Reference Saunders, Nazir, Kamali, Ryan, Evans, Langenecker, Gelenberg and McInnis2014); maternal inflammation has been proposed to play a role in the development of psychiatric disorders in offspring (Estes and McAllister, Reference Estes and McAllister2016). Further studies to elucidate the underlying biological pathways are warranted.

Strengths and limitations of this study

Our study has several strengths. First, the present study is the first to examine the association of maternal migraine and psychiatric disorders in offspring using the entire population in a country (Denmark). The nature of register data minimises the possibility of recall and selection bias. Second, we had detailed information on parental psychiatric disorders, family socioeconomic status and maternal cardiovascular diseases. Adjustment for these potential confounders could allow us to disentangle the effect of maternal migraine on psychiatric disorders in offspring from the effects of these potential confounders. Third, we had a long follow-up with a maximum of age 39 years. Thus, we can investigate not only psychiatric disorders manifested in childhood or adolescence, but also psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia spectrum disorders, mood disorders and adult personality disorders that are often diagnosed in adulthood (Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, Amminger, Aguilar-Gaxiola, Alonso, Lee and Ustun2007).

Our findings should be interpreted with caution due to several limitations. First, as in other observational studies there may still be potential residual confounding that could not be entirely eliminated (Fewell et al., Reference Fewell, Davey Smith and Sterne2007). For example, maternal pre-pregnancy body mass index, a risk factor for offspring psychiatric disorders (Mackay et al., Reference Mackay, Dalman, Karlsson and Gardner2017), might confound the observed association. However, additionally adjusting for pre-pregnancy BMI in women with available data did not change our results (shown in online Supplementary Table 6). Second, migraine was identified using a combination of hospitalisation registers and national prescription system, and the prevalence of migraine in our study is similar to another Danish population study (Le et al., Reference Le, Tfelt-Hansen, Skytthe, Kyvik and Olesen2012). However, the information on outpatient contact and medicine prescription were not available until 1995. This would lead to under diagnosis of maternal migraine before 1995, and some of them could be identified as postnatal migraine after 1995, which may underestimate the effect of prenatal exposure to migraine. Third, we could not rule out possible detection bias (Delgado-Rodriguez and Llorca, Reference Delgado-Rodriguez and Llorca2004). Children whose mothers with migraine are more likely to be in close contact with medical care than the unexposed children because of increased medical awareness, which might increase the opportunities to be diagnosed with psychiatric disorders. However, when investigating the specific psychiatric disorders with onset at different ages, varied risk estimates were observed. Thus, detection bias is unlikely to explain the association of maternal migraine with psychiatric disorders in offspring. Fourth, we chose not to adjust for perinatal factors such as preterm birth and low birth weight, as it has been shown that such adjustment may introduce bias (Hernández-Díaz et al., Reference Hernández-Díaz, Schisterman and Hernán2006). Furthermore, these neonatal characteristics could be potential mediators in the pathway from maternal migraine and psychiatric disorders in offspring (Mathewson et al., Reference Mathewson, Chow, Dobson, Pope, Schmidt and Van Lieshout2017; Skajaa et al., Reference Skajaa, Szepligeti, Xue, Sorensen, Ehrenstein, Eisele and Adelborg2019). Nevertheless, our findings showed that the elevated risk of psychiatric disorders in offspring was not attenuated after excluding chidren of preterm birth, low birth weight or low Apgar score, as shown in the sensitivity analysis.

Conclusion and policy implications

This study provides important information about offspring's mental well-being affected by maternal migraine using data from the Danish national registers. Given the high prevalence of migraine, especially among women at reproductive ages, our finding stands as strong evidence for concrete actions to be better management of women with migraine at reproductive ages and to screen mental health problems in their children.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796021000421.

Data

All data are stored at the secure platform of Denmark Statistics, which is the central authority on Danish Statistics with the mission to collect, compile and publish statistics on the Danish society. Due to restrictions related to Danish law and protecting patient privacy, the combined set of data as used in this study can only be made available through a trusted third party, Statistics Denmark (http://www.dst.dk/en/kontakt).

Acknowledgements

None.

Author contributions

H.W. and H.H.: performed the literature review, conducted data analysis, interpreted findings and drafted the manuscript. F.L. and J.L.: conceptualised ideas, designed and directed analytic strategy, interpreted findings, revised drafts of the manuscript and supervised the study from conception to completion. All other authors: interpreted of data and revised of the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final version.

Financial support

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81703237, No. 81530086, No. 82073570 and No. 81761128035), the Novo Nordisk Foundation (NNF18OC0052029), the Danish Council for Independent Research (DFF-6110-00019B, DFF-9039-00010B and DFF-1030-00012B), the Nordic Cancer Union (R275-A15770), Karen Elise Jensens Fond (2016), Collaborative Innovation Program of Shanghai Municipal Health Commission (2020CXJQ01) and Xinhua Hospital of Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine (2018YJRC03).

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Ethical standards

The study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency (No 2013-41-2569). According to Danish legislation, no informed consent is required for a registry-based study using anonymised data.

Patient and public involvement

No patients were involved in setting the research question or the outcome measures, nor were they involved in developing plans for design or implementation of the study. No patients were asked to advise on interpretation or writing up of results. There are no plans to disseminate the results of the research to study patients or the relevant patient community.