The relationship between word and image in later medieval art is a complex subject and fruitful for debate. The sequences of late medieval wall paintings in two churches in South Wales throw light on several aspects of this complexity. In order to engage with them, it is necessary to place their use of explicit and implicit text in a wider context.

It is no longer tenable to regard the visual imagery in the medieval church as libri laicorum, books for the illiterate. Stained glass, tomb carvings and wall paintings are far too complex and contain far too much text to justify this assumption. Athene Reiss has argued that wall paintings do not do what a book would have done: they do not present doctrine effectively, they do not tell stories coherently. Rather, they are designed primarily to stimulate devotion.Footnote 1 It is, however, possible to argue that, while wall paintings are not designed to act as text, they do respond to an awareness of text. Textual sources may in turn explain the coherent thinking behind apparently random choices of subjects for wall paintings. These sources may appear as text in the paintings, or they may be implicit, and they may reflect instruction or devotion.

There was clearly an awareness of the importance of written sources, even among those who did not have the skill to decode the written word. While the dissemination of texts through reading and reciting is difficult to track, it should not be underestimated.Footnote 2 There was a wide range of gradations from ‘litteratus’ to ‘illiteratus’, with implications for the relationship between visual and verbal communication. F H Bäuml describes what he calls ‘the social function of literacy’, ‘the use of literacy by those who were themselves illiterate’.Footnote 3 The culture of oral performance in Wales means that verbal dissemination of texts is even more likely. While wall paintings are, of all forms of religious art, probably the closest to the perspective of the ordinary parishioner, we should not assume that murals were disconnected from these diverse levels of literacy and the dissemination of literate culture. It has even been suggested that visual imagery could at times be too complicated even for the clergy, let alone their parishioners.Footnote 4 There is also surprisingly little evidence of connections between visual imagery (wall paintings in particular) and later medieval sermons, in England at least.Footnote 5 Miriam Gill has argued that this is in part at least a reflection of the nature of the surviving evidence. She cites some examples where parallels can be found, as well as numerous examples of wall paintings incorporating text in Latin and English.Footnote 6 Beverley Kienzle has also provided examples of the use of ‘visual images, whether real objects or imaginary scenes’ by Italian preachers.Footnote 7

Nevertheless, the purpose and function of text for the medieval viewer remains uncertain. What was the point of a Latin tag saying ‘Gula’ over a clearly identifiable depiction of the sin of greed (fig 1)? Was it simply to add weight to the image, to stress its importance? Was it to flatter the viewer by suggesting their literacy? Were medieval viewers capable of identifying familiar text (working from the image to the text, rather than the modern use of text to identify images) even if they could not decode unfamiliar text? In the case of prayers and invocations embedded in visual depictions, was the intended reader/viewer not the congregation but God?Footnote 8

Fig 1. Greed, from the Seven Deadly Sins at Llancarfan, with a Latin caption ‘Gula’. Photograph: © St Cadoc’s Church, Llancarfan.

In discussing the relationship between text and visual imagery, we need to be aware that while the majority of medieval viewers were not ‘literate’ in the modern sense of being able to decode unfamiliar text, they belonged to what Brian Stock called ‘textual communities’.Footnote 9 While Stock is speaking of an earlier period, the concept is still valid. Members of a textual community are aware of the importance of text. None of them may be literate in the modern sense, but they have the skill of recognising text and recognising that it has meaning. That meaning may be communicated orally, but it is essentially rooted in and validated by the written word. Consuming the written word was thus not a private but a social activity, what Kelly and Thompson describe as a ‘nexus of cultural practice’.Footnote 10 The contemplation of the written word was considered to be of value even for the illiterate. At the end of the Welsh Life of St Margaret of Antioch she promises certain salvation to those who copy, read or look at the Life, as well as to those who dedicate churches to her.Footnote 11

Meanwhile, images functioned as guides through text, as aids to meditations shaped by text, and as triggers for the memory of text (which could have been heard rather than read). They are more than aides-mémoire: visual ‘reading’ is non-linear, communicating complex concepts simultaneously. As Reginald Pecock pointed out in his Repressor of Overmuch Blaming the Clergy,

the iȝe siȝt schewith and bringith into the ymaginacioun and into the mynde withynne in the heed of a man myche mater and long mater sooner, and with lasse labour and traueil and peine, than the heering of the eere dooth.

Pecock goes on to point out that images (on the walls of a church, for example) can be viewed simultaneously and can be seen at any time, without the need to access books.Footnote 12

Awareness of text could be bolstered by other forms of multimedia production. It is over a century since Eleanor Hammond called for a better understanding of the relationship between medieval poetry and the visual arts, but much still needs to be done.Footnote 13 Lydgate is well known for his poetry accompanying visual imagery, but both Hammond and Claire Sponsler have suggested that some at least of his poetry may have been intended to be read aloud while a tapestry or wall painting was being viewed or during a mimed performance, although, as Hammond admits, we have no evidence for this.Footnote 14 Hammond even suggested that shorter versions of some of the verse romances might have been performed to accompany the ‘sotleties’, tableaux in pastry or sugar presented at the close of each course in the most lavish medieval banquets.Footnote 15 Jennifer Floyd has challenged this in the specific context of Lydgate’s St George poem, which she suggests could all have been accommodated in the hangings for the Armourers’ Hall, but the general argument is still valid.Footnote 16 As some recent theorists of the semiotics of communication have repeatedly emphasised, multimodality and performance art are not a modern invention.Footnote 17

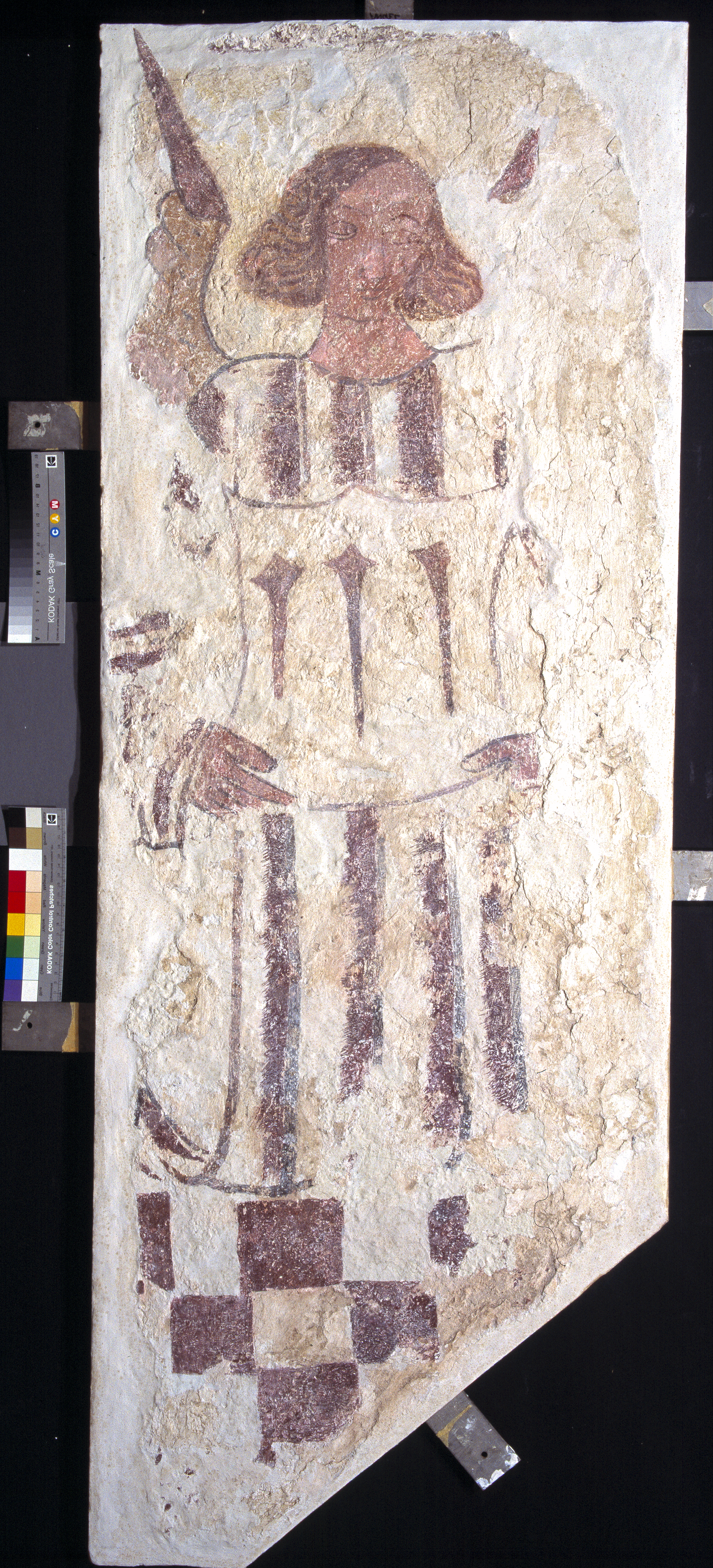

If medieval viewers were literate in the sense of being aware of the meaning and significance of text, we need to consider how far their choice of visual images (in church and elsewhere) was informed by textual sources that they knew even if they could not read them. The stories from the Golden Legend and from mystery plays clearly informed much church decoration. These need not, however, have been transmitted through writing: they were part of the oral tradition, dependent on memory and capable of infinite variation.Footnote 18 More specifically, the concept of implicit text can be used to suggest a structuring principle underlying more complex visual sequences and schemes combining multiple images: this could be a specific literary text or collation or an overarching theme from a core text such as the Bible, which draws together a number of visual themes. The wall paintings from the ruined church at Llandeilo Talybont in western Glamorgan, now recreated at the Welsh National History Museum in St Fagan’s, have embedded text and captions below some individual paintings. Others, though, seem to take their inspiration from the medieval liturgy without actually repeating the textual source.Footnote 19 The main sequence of paintings is a reflection on the story of the Crucifixion told through the Instruments of the Passion (fig 2).

Fig 2. Angel bearing a shield with the three nails of the Crucifixion, from the church at Llandeilo Talybont. Photograph: © Amgueddfa Genedlaethol Cymru/National Museum of Wales.

Underlying this is presumably one of the many medieval meditations on the Instruments, applying them to individual sins and shortcomings.Footnote 20 Llandeilo Talybont was in a Welsh-speaking area and there are no surviving Welsh versions of meditations like the English ‘O Vernicle’: this is not to say, though, that they did not exist, in written form or in the oral tradition. Devotion to the Instruments was deeply rooted in late medieval Welsh piety. Poets who went on pilgrimage to Rome spoke of the relics of the Crucifixion they saw there, including the pillar where Christ was tied to be scourged, nine thorns from the Crown of Thorns, the sponge and a piece of the True Cross. Virtually all of them mentioned the Vernicle, described by Robert Leiaf as ‘a picture of Christ’s face made by his own sweat’.Footnote 21 Tomas ab Ieuan ap Rhys’s poem to the Holy Rood of Llangynwyd, described by Christine James as ‘a compressed Crucifixion narrative’, tells much of the story through the implements involved.Footnote 22

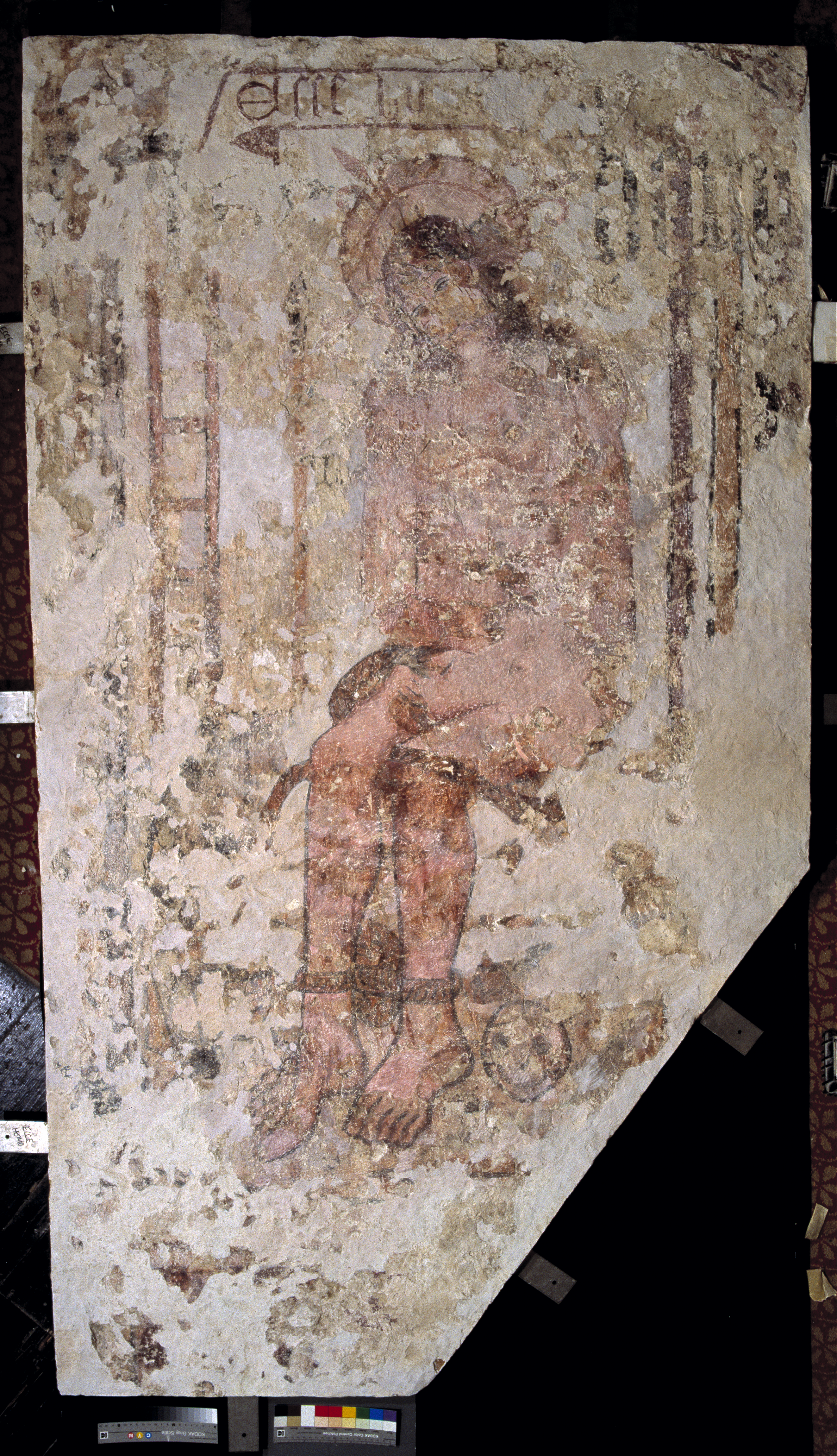

The Llandeilo Talybont wall paintings suggest other underlying textual sources as well. Two of the surviving paintings resonate with readings from the Holy Week liturgy. The scene over the window in the north wall shows Christ crowned with thorns, with two grotesque heads spitting at him. In the Biblical accounts of this episode Christ was blindfolded, but in the Llandeilo Talybont wall painting his sorrowful eyes gaze directly at the viewer. This has parallels elsewhere, and the very direct gaze of the eyes engages the viewer (fig 3).Footnote 23 It can also be seen as a reference to the passage from Isaiah 50:6, read on the Monday of Holy Week:

I gave my back to the smiters, and my cheeks to them that plucked off the hair; I hid not my face from shame and spitting.

Fig 3. The Mocking of Christ, from Llandeilo Talybont. Photograph: © Amgueddfa Genedlaethol Cymru/National Museum of Wales.

To the south of the south aisle altar is another painting that resonates with the Old Testament readings for Holy Week. It depicts the Bound Christ or Sessio, Christ with hands and feet tied, seated waiting for crucifixion (fig 4). The connection here is less clear, but it could be linked either with the reading from Isaiah 53:3–7, which describes the ‘suffering servant’, or with the Lamentations of Jeremiah, which also formed part of the Holy Week liturgy.Footnote 24 It may be (although the modern reconstruction of the paintings does not reflect this) that others of the original wall paintings might have continued the same sequence with other reflections on the prophecies or other Holy Week readings. The combination of meditation on the Instruments and reflection on the readings does not fall into an obvious sequence around the church, but may nevertheless have offered scope for a journey (or several journeys) around the paintings, something conceptually and physically more complex than the more recently-devised Stations of the Cross.

Fig 4. The Bound Christ, from Llandeilo Talybont. Photograph: © Amgueddfa Genedlaethol Cymru/National Museum of Wales.

It is also possible that a series of texts underlies the sequence of wall paintings recently rediscovered in the church at Llancarfan in the Vale of Glamorgan (fig 5). These include a massive St George and the Dragon, a Death figure dragging a fashionably-dressed young man out through a window towards the churchyard, an idiosyncratic set of the Seven Deadly Sins and a damaged set of the Seven Corporal Acts of Mercy.Footnote 25

Fig 5. Death and the Gallant, St George and the Seven Deadly Sins at Llancarfan. Photograph: © St Cadoc’s Church, Llancarfan.

These paintings all have parallels elsewhere: the figures of Death and the Gallant, for example, are part of the late medieval tradition of the macabre and the memento mori and are directly comparable with the surviving Death and the Gallant at Newark (Notts) and the lost painting in the Hungerford chapel in Salisbury Cathedral (fig 6).Footnote 26

Fig 6. Death and the Gallant at Llancarfan. Photograph: © St Cadoc’s Church, Llancarfan.

There is text incorporated in the Llancarfan paintings. The Sins are neatly captioned (in Latin): Superbia, Gula, Accidie and so on; however, it is possible to suggest more specific literary sources that underlie the way in which they are presented in combination here.

Elucidating the possible connections between the paintings discovered so far at Llancarfan requires that they be placed in a tentative chronological sequence. Dating the paintings has been the subject of some debate. The costume of the Gallant and of the figures in the St George and the Sins suggest a date in the later part of the fifteenth century, possibly in the 1460s or 1470s. Jane Rutherfoord has suggested that features of St George’s armour indicate an earlier date, possibly in the 1440s;Footnote 27 however, there are other features indicative of both earlier and later dates. Tobias Capwell has identified the saddle and crest as distinctive types dating from the fourteenth century. He has also pointed out that the armour has been rather freely interpreted, indicating that the artist may not have been trying to represent the armour of his own time. He suggests that ‘what we may have here is a late fifteenth-century artist purposely attempting to represent an old-fashioned armour design … a sense of St George as a larger than life hero galloping out of the distant past’.Footnote 28

Heraldic evidence above the figure of St George suggests an even later date. The shield with three swans on a black background probably represents the arms of the local Bawdrip family of Penmark Place, about a mile south of Llancarfan. Thomas Bawdrip of Penmark married Jenet Raglan of Garnllwyd, a small mansion to the north of Llancarfan village, probably in the 1480s or 1490s. The wall painting could commemorate the wedding, although there is no evidence for a specific family connection with the cult of the saint. A date as late as the 1490s might suggest a connection with Prince Arthur, son of Henry vii, who was installed as a Knight of the Garter in 1491. His personal emblem was a single ostrich feather (rather than the triple feathers more familiar as the emblem of the English princes of Wales) and there is a single ostrich feather on the head-dress of St George’s horse.Footnote 29 This date would, however, be unlikely given the style of some of the costumes, and we may settle for a date in the third quarter of the fifteenth century.

All the paintings are clearly on the same layer of limewash, and are therefore of roughly the same date, but at least two different painters were involved, and the dating may therefore be slightly different. From the layout, with the castle in the St George painting constrained to respect the space in which the Death and the Gallant stands, it seems that the latter is the earliest. The St George and the Sins appear to be by the same painter: the style of drawing and the distinctive costumes of some of the figures are very similar. The simplest assumption, then, would be that the Death and the Gallant came first, the St George followed it, then the Sins and the Acts of Mercy were added, possibly as a commentary: the Sins to be avoided if one wished to avoid the young man’s fate, the Acts as a parallel to the heroic virtues displayed by St George.

There is, however, a more subtle connection between the Death and the Gallant and the Sins, a connection depending on a text that does not appear in the paintings but may nevertheless be implicit in their design. This is the fifteenth-century satirical poem that begins

lYKe as grete wateres encresyn in to floodes fele

So that narowe forthes may hem nat susteyn

Ryght so pryde unclosyd may not concele

These new wretchednesses that causeth us to co[m]pleyn.Footnote 30

The poem goes on to attack the sin of pride in the ‘Galauntes’ – the young men of England who, having been defeated and expelled from France, have brought back with them corrupt French fashions in clothing – and to link their pride with the Seven Deadly Sins. It presumably dates from some point towards the end of the Hundred Years’ War, around 1450. In condemning (imported) fashion as a source of sin, it represents a popular theme in later fourteenth- and fifteenth-century poetry. As a topos, it could usefully be manipulated to attack both extravagant courtiers and members of the lower classes who were subverting social order by trying to imitate their betters.Footnote 31

The specific poem under consideration here, explicitly linking the ‘Galaunt’ and his corrupt fashions in clothing with the Sins, was clearly a popular take on this theme. It survives in three manuscript versions (with considerable variation): Trinity College, Cambridge ms R.3. 21; English College in Rome, ms A. 347; and Yale University, Beinecke Library, Takamiya Deposit 94.Footnote 32 All of these are composite volumes, including a range of other texts, religious, historical and scientific.Footnote 33 The incorporation of the poem in these three volumes suggests its popularity, while the number of variants suggests other copies may have been lost. Some of the variants could be accounted for by copying from individual sheets that have become disarranged, but others are more difficult to explain, and it is possible that they derive from versions written down from memory, further testifying to the wider currency of the poem. The poem was also printed in four separate editions by Wynkyn de Worde between about 1510 and the 1520s, suggesting its continuing popularity: its publication must have been seen as a financially-viable enterprise.

While the poem has numerous variants, in both manuscript and printed versions, the section relevant to the Sins is fairly constant. After an introduction bewailing the effects of the sin of pride, the poem presents the Seven Deadly Sins through an acrostic making up the word ‘Galaunt’.

Ffor in thys name Galaunt ye may se expresse

Sevyn lettres for som cause inespeciall

Aftyr the sevyn dedly synnes full of cursydnesse

That maketh mankynde unto the devyll thrall.

Was nat pryde cause of Lucyferes fall

Pryde is now in hell and Galaunt nygheth nere

All England shall wayle that ever came he here.Footnote 34

In some of the manuscript versions (though not in the printed versions), this is introduced with a verse dealing with each sin in one line:

G. for glotony, that began in paradyse

A. for Avaryce that regneth the world thorough

L. for luxury that noryssheth ev[er]y vyce

A. for Accydy that dwelleth in towne and borough

V for Wrathe that seketh both land and forough

N. for noying Envy that dwelleth ev[er]y where

T. for toylous pryde these myscheven our land here.

The poem then continues with a stanza on each of the Sins, using a framework of alliteration to spell the word GALAUNT. In the Trinity College version the Latin name is added on the outer margin, in red, although this does not fit the acrostic structure:

Thow gay galaunt Gloton by thy name Gula

That wt glosyng and gabbyng getest that thow hast

Gyle was thy godfadyr and gelowsy thy dame

In gestyng and rangelyng thy dayes byn wast.

For all thy gloryous getyng age gnaweth fast

Thy glasyn lyfe and glotony be so glewyd in fere

That England may curse that ev[er] thow concevyd were.

For appetytes of avaryce be to hem so amerous Avaricia

Wt ambicion and arrogaunce have they suche affinite

For augores and aventures make hem so debatous

Affying aftyr a state of count[er]fetyd auctoryte

Of aventures and agor mayst thow avaunt the

As a lyen to all goodness in thyne aray doth appere

That England may curse that ev[er] thow bore were.

Luxuria For thy lewde lechery lepeth so fast abowte

That lawe and good love byn almost lorne

For of lust and lesynges lede they suche a rowte

That lassyvyous lechery hath clennes all to torne

These labours fast to lese that other men gat beforne

For lewdnes to these loselles ys so ioynyd in fere

That England may wayle that ev[er] they came here.

Accidia Theyr abho[m]i[n]able accydy accuseth all oure nacion

Owre angelyke abstinence ys now refusyd

For Antecrystes ar many thys new simulacion

Allas that suche myschyef among us shuld be usyd

For accydy and avaryce hath us so now accusyd

That all man[er] adv[er]syte seweth us yere by yere

And England may wayle that ever they came here.

(Here the verses seem to have got out of order in the Trinity ms version: the verse on Envy with its alliterative focus on N should come after the verse on Anger with its focus on U/W.)

Invidia The nobeley of oure nature hath her nysyte devoured

For v[er]ray necessyte nygheth owre desolacion

Hath nat thys new singylnes ouwre prosp[er]yte so noyed

That neglygence noryssheth nede to owre confusion

Thys causeth calamites kynrede cursyd be all hys nacion

For nev[er]thryftes nowghtynes noyeth us so nere

That England may wayle galauntes com[m]yng here.

Ira Thys wast in oure wantones hath wadyd so depe

Wt oure wrechyd weryng ys nat owre wede to torne

For to wyldnes and to wrethe we take now most kepe

In vanyte and in vengeaunce we rek nat what ys lorne.

For wyne and for women and for ware the horne

For Venus dryveth awey virginitie both here and there

That england may wayle of galauntes com[m]yng here.

Superbia For tryfelers and tregetours that tav[er]nes hauntyn

Have temp[er]aunce and troweth so trodyn undyrfoot

Also turmentoures and termagauntes that tresons hydyn

Wt tyrauntes and traytours that be toylous in moot

Tyll these trewants be tryed out trewly ther is no boot

And trysyd to Tyborn and trodyn on the fere

Elles shall England wayle that ev[er] they came here.

The Trinity College ms ends with this verse. In the English College ms, though, and in Wynkyn de Worde’s printed versions, the whole poem ends

O Englonde, remembre thyne olde sadnes

Exyle pryde and relyeve to thy goodnes

That thou may resorte agayne to thy gladnes.

Synne hath consumed this worldes humanyte

Praye god thou may reioyse [in] thyn olde felycyte

And his blessyd modyr as this lande is here dowere

We have no cause to wayle that ever it came here.

(This verse also appears in the Yale University ms, but in what Boffey suggests is a less appropriate position in the middle of the poem.)

In a sermon preached towards the end of the 1490s and printed by Wynkyn de Worde in 1497 and 1502, John Alcock, bishop of Ely, attributed the Galaunt poem to John Lydgate.Footnote 35 The Short title Catalogue (STC) entry for the printed version repeats Alcock’s attribution but there is no other evidence for it, beyond Alcock’s recollection of ‘dayes here before in my youghthe’. It may simply have been Alcock’s assumption, based on the fact that Lydgate also wrote the poem that accompanied the famous Dance of Death at Old St Paul’s, and the figure of the Gallant was familiar as one of the elements of Death and the Gallant, a popular warning image in the same memento mori tradition as the Dance of Death. It may have been Alcock’s ascription that led Stowe to include it in his list of Lydgate’s works. MacCracken, in his edition of the minor secular poems, considered it and rejected it mainly on stylistic grounds. He did suggest the possibility that Alcock may have been remembering not the poem as we now have it but a similar poem by Lydgate.Footnote 36 Gillespie, however, includes the poem in a list of ‘pre-1534 anonymous quartos of works, attributable to Lydgate’.Footnote 37

Lydgate’s reputation has suffered since the seventeenth century, but in the fifteenth century he was one of the most eminent poets of his day, regarded in some circles more highly than even Chaucer and Gower.Footnote 38 He remained one of the most popular (and presumably therefore the most saleable) authors for the early printing industry, with his work receiving both lavish folio printings and smaller portable editions. It seems unlikely on the face of it that, if his authorship of the Galaunt poem was known or even widely assumed, de Worde would not have mentioned it. Nevertheless, it is precisely the kind of highly visualised social and political commentary for which Lydgate was known. It is also worth remembering that fifteenth-century ideas on authorship were different from those encouraged by print culture. While authorship was not unimportant to a medieval readership, it was frequently not identified in individual texts.Footnote 39 Most of the works now identified as by Lydgate in the manuscript books that also include the ‘Galaunt’ poem are not actually specified as being by him in the manuscripts.Footnote 40 Alcock’s recollection of the poem from his ‘youghthe’ and his assumption that it was by Lydgate are further testimony to its wide currency and popularity.

The male figures in three of the Llancarfan Sins – Lust, Accidie and Anger – wear precisely the clothes that were criticised in the poem, short tunics with tightly-fitted waists and skin-tight hose. The Llancarfan sequence of the Sins is, however, idiosyncratic and slightly different from that in the Galaunt poem (fig 7). Envy is subsumed into Avarice, with one image of a man hoarding gold coins. Accidie is represented in its most challenging form, a man driven by the demons of despair to kill himself. This leaves room for another depiction of Sloth (Sompnolentia in the Latin caption), a man lying in bed while the church bell rings (fig 8). In spite of these differences, though, the underlying textual link between the Sins and the Gallant remains clear.

Fig 7. The Seven Deadly Sins at Llancarfan. Accidie is at the top left. Photograph: © St Cadoc’s Church, Llancarfan.

Fig 8. Avaritia and Sompnolentia at Llancarfan. Photograph: © St Cadoc’s Church, Llancarfan.

The survival of the Galaunt poem in so many manuscript and printed versions (albeit in printed versions dated some time after the Llancarfan wall paintings) thus suggests that the poem was both well-known and appealing to a wide audience, and that the link it made between youthful concern for fashion and more serious sin was well known. There is a more tenuous suggestion of a similar link between fashion and individual deadly Sins in the lost Death and the Gallant paintings in the Hungerford chapel of Salisbury cathedral, in which Death says to the Gallant,

Grasles galante in all thy luste and pryde

remembyr that thow schalte onys dye

Here, though, the text appears as part of the painting, in banderoles over the heads of the figures. It cannot be traced elsewhere and seems to have been commissioned specifically for the Hungerford chapel.Footnote 41

The link between the paintings of Death and the Gallant and the Sins at Llancarfan is thus very much part of later medieval thinking, although it is not of course possible to prove that their combination in a single painted scheme was inspired by the actual poem discussed above. There is a possible, if more tenuous, link between the painting of St George and the Sins. In 1515, Richard Pynson published a verse ‘translation’ of Baptista Spagnuoli’s Georgius by the Anglo-Scottish poet Alexander Barclay, who was at that time a monk at Ely.Footnote 42 Barclay and Pynson worked closely together on a range of publications, from literary verse translations to occasional pieces relating to current events.Footnote 43 Barclay’s Life of St George was more a paraphrase of Spagnuoli than a straightforward translation. This was his usual practice: in the preface to his translation of Sebastian Brant’s Ship of Fools he explained

I haue but only drawen into our moder tunge, in rude langage the sentences of the verses as near as the parcyte of my wyt wyl suffer me, some tyme addynge, somtyme detractinge and takinge away such thinges a semeth me necessary and superflue.Footnote 44

As he did with most of his translations from the Latin, he included Spagnuoli’s Latin text as well. The parallel printing facilitates a comparison of the two versions and the identification of Barclay’s amendments. Noticeably among these, in his Life of St George, Barclay pruned out a number of Spagnuoli’s classical references. Towards the end of the story, with the dragon dead, the people of the city converted to Christianity and baptised, Spagnuoli had a lengthy passage comparing the dragon with a list of monsters from classical literature. Barclay omitted this, describing it in a marginal note as ‘hec fabulosa’. He replaced Spagnuoli’s classical comparisons with a sermon preached by George to the king and queen and the people of the city. In this, after instructing the commons to be obedient and the rich to help the poor, he lists the Seven Deadly Sins and advises how they may be avoided.

The sermon begins:Footnote 45

Right noble kynge/and comons that here be

ye know howe god/of his abundaunt grace

Hath you by fayth made bretherne vnto me

Se, ye his lawes with loue and drede imbrace

Whiche if ye do in heuyn shalbe your place

Let no newe doctryne the myndes of you remeue

For fere nor fauour from this your true byleue.

ye that are comons obey your kynge and lorde

Obserue vnto hym loue and fydelyte

Auoyde Rebellyon for certaynely discorde

Expell enuy and slouth moste chefe of all

Where slouth hath place there welth is faynt and small.

After verses encouraging charity, constancy and amity, the sermon returns to the Sins:

Blynde nat your myndes with wretchyd couetyse

Spende nat your ryches in prodygalyte

A meane is mesure attaynynge nat to vyce

Within the boundys of lyberalyte

Leue wrath prouoker of great enormyte

Let nat blynde pryde your meke myndes confounde

Syth it so many hath brought vnto the grounde.

Auoyde vyle venus and lustes corporall

Destruccyon of soule of body and ryches

Mankynde subduynge to maners bestyall

Fle glotony whiche is but bestelynes

Let abstynence expell from you exces

By immoderate dyet: exces and glotony

Man oft is mordrer of his own body.

There is also a nod in the direction of the Corporal Acts of Mercy:

ye ryche helpe them which haue necessyte

Eche socour other suche way s charytable

No man presume more hye than his degree

A lowest place : is oft moste sure and stable

Abyde in vertue be neuer chaungeable

Namely be true to god your heuynly lorde

Thus shall you lyuynge and your byleue accorde.

Barclay was not a creative writer: his output consists mostly of translations and paraphrases. He does provide some original material in his prefaces (for example, his recommendation in the introduction to The Ship of Fools that his readers reform their behaviour in order to avoid finding themselves within the ship), but this is arguably different from the addition of a whole new section in the actual text. The idea for a sermon on the Sins may have been his, but it is equally likely that it came from another source or tradition. It cannot, however, be found in other lives of St George: it is not in the Golden Legend version of the story, nor in the South English Legendary. The Legendary completely omits the episode of the dragon.Footnote 46 The Golden Legend limits George’s sermon to an instruction to the king to rule the church, honour the priests, hear their services diligently and have pity on the poor. Lydgate’s poem for the London Armourers’ ‘steyned halle’ is simply a rhyming version of the Golden Legend and Mirk’s Festial is similarly a paraphrase.Footnote 47 The last instruction may link St George with the Seven Corporal Acts of Mercy, but not with the Sins.

However, episodes from saints’ lives can sometimes only be deduced from chance survivals. Depictions of the Cambro-Breton saint Armel often have a ship in the background, and he was the saint Henry Tudor asked for help when threatened with shipwreck. None of the surviving versions of his life involves a ship or a shipwreck, but the image is so pervasive that one suspects an oral tradition that did not reach the written record.Footnote 48 With regard to St George himself, Samantha Riches has suggested that the first scene in the destroyed St George stained glass cycle at Stamford (Lincs), and possibly some of the scenes missing from Dugdale’s record of the glass, may relate to ‘an otherwise lost tradition concerned with the early part of St George’s career’.Footnote 49 Nelson makes the point that Barclay’s translation was not well known, and that the similarities between it and Spenser’s ‘Legend of the Red Cross Knight’ could derive from Spagnuoli’s original or indeed from any one of the other available versions in tapestry or painted cloth.Footnote 50 The sermon about the Sins could equally well derive from another original.

The words that Barclay gives to George appear almost identically in a fragment copied on the flyleaf of a manuscript parchment volume of Lydgate’s Fall of Princes.Footnote 51 Ker has identified this volume as belonging first to Battle Abbey.Footnote 52 It may originally have belonged to the community, but at one point it belonged to the prior, John Neuton or Nuton (who was also the owner of other manuscripts).Footnote 53 It left Battle Abbey some time before the Dissolution, passing through the hands of William Saunders and Thomas, Lord Dacre (1467–1525) and his descendants.Footnote 54 The manuscript dates from the third quarter of the fifteenth century, but the fragment of poetry is in an early sixteenth-century hand.Footnote 55 Specifically, it is an early cursive secretary hand, with no evidence of italic influence. While there are some diagonal strokes, the letters are generally upright, with none of the right-hand slope typical of italic script. The lower-case ‘h’ extends below the writing line but has not lost its shoulder. The flat-topped ‘c’ and ‘a’ without attaching strokes are also typical of the earlier sixteenth century. The rather sprawling style is reminiscent of the poor quality of later fifteenth-century styles (resulting from the blend of court hand and cursive hands), but does not in itself suggest a date earlier than 1500. Finally, the lack of italic influence suggests that the writer had not had a university education.

The parchment leaf on which the poem is copied is much coarser than that used for the main body of the original volume, but the volume has clearly been rebound several times (with the loss of some marginal annotations) and it is not now possible to tell whether the coarser parchment was part of the original format or was added later. The leaf with the fragment about the Sins has ‘Bocas’ at the top in a sixteenth-century hand and ‘George’ upside down at the bottom right of the first page in a hand of c 1700. The annotations suggest that the parchment leaf was part of the original volume by the sixteenth century and that its connection with the life of St George had been identified some time later, but does not help to establish the date of the poem.

In a discussion of flyleaf poems, R H Robbins suggests that they were sometimes composed by the owners of the books, but that many appear in several sources and have been copied in by owners using the flyleaves as a sort of commonplace book.Footnote 56 The poem in Sloane 4031 is very close to the version in Barclay. It does not have the first verse of George’s speech, but it does have an additional verse encouraging rulers to set a good example to their subjects. Poems were frequently copied from printed texts into manuscripts, or incorporated into hybrid volumes of print and manuscript.Footnote 57 A S G Edward, who first identified the Sloane 4031 fragment, suggests that it is unlikely that the additional verse is an interpolation by the person who copied the poem.Footnote 58 He suggests that the source of the Sloane fragment was a more complete version of Barclay’s poem than the one published by Pynson, but this also seems unlikely given the close relationship between Pynson and Barclay. There were, of course, many poems in circulation about the Sins, including the ones by Anthony Woodville, second Earl Rivers, which Caxton seems to have had hopes of publishing.Footnote 59 However, it is at least possible that the fragment came from a longer work linking the Sins with St George and that it was that which inspired Barclay to replace Spagnuoli’s classical monsters with St George’s homily.

There is one more rather tangential connection between the Galaunt, the Sins and St George. At the end of the Galaunt poem in some versions is a reminder that England is ‘Our Lady’s dower’. The connection between England as the Virgin Mary’s dower, St George as England’s patron saint and St George as ‘Our Lady’s knight’ is complex and difficult to disentangle.Footnote 60 A figure identified as the Virgin Mary does appear in the Llancarfan painting of St George: she is to the right of the scene, with flowing hair, dressed in a scarlet cloak and a laced gown, and with her hand raised to bless St George in his endeavours. I have suggested elsewhere that the identification of this figure is not absolutely certain.Footnote 61 It is surprisingly small in contrast with the other figures. One would expect a female saint associated with St George to be St Margaret, another dragon-subduing saint who actually appeared in the Norwich guild play of St George, assisting the hero in his endeavours.Footnote 62 The comparatively small size of the Llancarfan figure suggests a supporting player in the scene, but it does not have Margaret’s identifying cross-staff. It is even possible that a figure of St Margaret seen in a wall painting of St George elsewhere could have been reinterpreted as the Virgin Mary.

Barclay’s poem is far too late to have inspired the Llancarfan wall paintings. If, however, he was drawing on an earlier tradition linking St George with the Sins, we can look to these two textual traditions to account for the grouping these apparently random representations. Knowledge of and interaction with these – or similar popular devotional and pious texts – would lend a coherence to this otherwise diverse scheme. It is at least possible that we have a succession of texts that ties the paintings of Death and the Gallant, the Sins and St George into a more coherent whole. This (a scenario in which the connections made in these texts inspire both the selection and the combination and ordering of the subjects at Llancarfan) requires rethinking the chronological sequence of painting. Death and the Gallant is clearly the first, stylistically and because of its spatial relationship with St George. This may have inspired the painting of the Sins. It is difficult, though, to see why the Sins were painted so far away from the figure of the Gallant. They are all on the same layer of limewash as the painting of St George, so there cannot have been another painting between them that was initially preserved but later overpainted. The Virgin Mary’s robe overlies the framework of the Sins. The Sins and St George are stylistically very similar and probably by the same painter (or team of painters: Jane Rutherfoord has suggested that the poor quality of the painting of the Princess is because she was painted by an apprentice).Footnote 63 It is quite possible, though, that the concept of a scheme of the Sins and St George may have been conceived as a whole, but painted as funds allowed, with the Sins painted first and the St George added later. Llancarfan was not a wealthy parish, and fund-raising may have taken some time.

All this is, of course, highly speculative. It is impossible to prove that these specific texts inspired the scheme of wall paintings at Llancarfan. There are good reasons to believe that the concept of linking the Galaunt with all the Seven Deadly Sins, as found in the poetic text, was well known. The sermon on the Sins is clearly only one strand in the more varied literature on St George, but is not impossible that this motif used by Barclay was already present in sources circulating in the later fifteenth century. The Galaunt poem was clearly popular, but we have no evidence to link any of the surviving versions with South Wales. It is, of course, possible that someone in Llancarfan may have been aware of a version of the poem through oral transmission, or may have seen a similar sequence of paintings elsewhere. It is similarly difficult to tie the Llandeilo Talybont wall paintings to a specific meditation on the Instruments of the Passion. Nevertheless, the contrast with the Hungerford chapel is clear. At Salisbury, in the elite context of a semi-private chapel, we have texts painted on the walls, chosen from (sometimes quite obscure) parts of the liturgy or possibly commissioned for the purpose. At Llandeilo Talybont and Llancarfan, in two comparatively remote parish churches, we have wall paintings that may reflect texts once seen, or transmitted orally, or ideas part of the matrix of written and oral transmission. We also have the possibility that apparently random assortments of images may be part of a deliberately thought-out scheme.

More remains to be discovered at Llancarfan: there is, for example, surviving medieval painted plaster over the chancel arch, raising the possibility of a Doom painting, and post-Reformation texts in the east part of the south aisle may overlay medieval paint. Paint on the north wall of the south aisle, facing the door, may be a St Christopher. While the recognition of the concept of an implicit text (a literary or liturgical source or form that underpins and makes sense of the presentation or combination of scenes) cannot be identified for all late medieval mural schemes, and indeed may not be relevant to them, there is a sense in which a broader category of subjects could be united by a common text. For example, the image of the Day of Judgement in a Doom painting is thematically linked to the catechetical subjects of the Seven Deadly Sins and Seven Corporal Works of Mercy. The Acts of Mercy derive from the ‘Little Apocalypse’ in the Gospels, most clearly set out in Matthew 25, and Christ’s words, ‘Venite, benedicti Patris mei’ (Come, ye blessed of my father) and ‘Ite, maledicti, in ignem aeternum’ (Go, ye cursed, to everlasting fire), were often quoted in Doom paintings. In the Doom at Trotton (West Sussex), an angel welcoming the saved into Heaven has a speech scroll reading ‘Venite, benedicti’.Footnote 64 If the painting facing the door is a St Christopher, the idea of protection from sudden death would provide a thematic connection with the memento mori aspects of the Death and the Gallant.

In his seminal article on art in the later medieval English parish church, Paul Binski argued for structuring ideas behind the design of altars and rood screens, but was less certain about wall paintings. These, he felt, could be ‘copious chaos’, ‘medleys of commonplaces … Whether and to what extent such medleys had covert structural principles is less clear’.Footnote 65 For all their diversity, it can be suggested that the wall paintings at Llandeilo and Llancarfan are neither random nor incoherent: they reflect a complex process of interaction between public art and public knowledge of texts.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The initial inspiration for this article came from Ian Fell’s discovery of the poem of the Galaunt and Barclay’s verse life of St George. I am grateful to Ian for these and for subsequent discussions; to Tony Parkinson, with whom I worked on the Llandeilo Talybont wall paintings; to David Griffith FSA, for generously discussing and sharing his work on vernacular inscriptions in advance of publication of his Words Beyond Books: vernacular inscriptions in late-medieval England (Brepols, forthcoming); to Toby Capwell FSA, of the Wallace Collection, for a detailed analysis of the armour of St George in the Llancarfan wall painting; to successive incumbents of Llancarfan who have worked with the local community to preserve and interpret the wall paintings there; to Jane Rutherfoord, whose work on the conservation and interpretation of the paintings has added immeasurably to our understanding; and to the anonymous peer reviewer, who seems to have understood my ideas far better than I did.