Introduction

Physical activity has been promoted as a means of improving cognition, mood, behaviour and physical condition for care home residents, notably those living with dementia. However, attempts to implement it have tended to be limited, short term and difficult to sustain (Bowes et al., Reference Bowes, Dawson, Jepson and McCabe2013). We set out in the exploratory research reported here to explore the cultural contexts of physical activity within care homes,Footnote 1 to identify constraints and facilitators for change. We begin the paper by considering the wider contexts of physical activity in older age and the cultural location of care homes and physical activity within them, before proceeding to detailed discussion of our qualitative research in five care homes.

Interest in care home cultures, and their significance for understanding many aspects of life in care homes, has increased. Killett et al. (Reference Killett, Burns, Kelly, Brooker, Bowes, La Fontaine, Latham, Wilson and O'Neill2016) trace this interest back to early literature on dementia care, such as Kitwood and Benson (Reference Kitwood and Benson1995). They then link their discussion to work on organisational cultures such as Schein (Reference Schein1990). The present paper develops discussion of care home cultures into the particular area of physical activity. In doing so, it draws on the theoretical work of classic anthropologists such as Geertz (Reference Geertz2017), who saw culture as fundamental to social life, providing ways of seeing the world that then guide actions, including interpersonal interactions and the workings of organisations. We link this classic theory with more recent discussion of cultural ageing, notably Phoenix and Tulle (Reference Phoenix, Tulle, Piggin, Mansfield and Weed2017) and Higgs and Gilleard (Reference Higgs and Gilleard2014), in line with Twigg and Martin's (Reference Twigg and Martin2015) characterisation of cultural gerontology.

Our focus on culture does not imply that it is deterministic. Cultural factors need to be considered alongside other social determinants of health: according to Dahlgren and Whitehead's (Reference Dahlgren and Whitehead1991) ‘rainbow model’ of these, cultural factors appear in the outer layer, providing part of the overarching frame within which health is influenced. Like them, we see culture as part of the key framework for influencing activity and experience, and note that it interacts with individual, social and community factors. Their discussion of cultural factors focuses primarily on minority ethnicity: our discussion goes further than this in considering cultural issues relating to ageing, dementia and care homes. We will argue that cultural factors are not necessarily consistent or widely shared, but dynamic, diverse and contested.

Background

Physical activity in older age

Benefits of physical activity for older people are widely promoted, principally on health grounds. Phoenix and Tulle (Reference Phoenix, Tulle, Piggin, Mansfield and Weed2017) have argued, however, that physical activity is increasingly considered both a cultural and a personal dimension of ageing. They reference multi-disciplinary research focusing on the contexts of physical activity, what people do and their experiences of it. They see physical activity as a means for older people to take greater control over their ageing, and define it for themselves, potentially resisting perceptions of relentless physical and mental decline. They highlight many cultural assumptions that prevail around older people's physical activity, including the notion that sedentariness in older age can be a marker of privilege and wealth (Tulle, Reference Tulle2014). They conclude that recent encouragement of physical activity in older age can be seen as an aspect of societal attempts to control a problematic ageing population, but also that physical activity can be a means whereby older people can themselves exert greater control over their lives. Thus, contextualised in societal attitudes to ageing, experiences and expressions of physical activity emerge as profoundly culturally influenced.

Further evidence of this can be seen in literature relating to the management of risk in the care of older people. Clarke and Mantle (Reference Clarke and Mantle2016), drawing on Alaszewski et al. (Reference Alaszewski, Harrison and Manthorpe1998), emphasise that a focus on risk avoidance can prevent older people having opportunities to move about or engage in physical activity because all presumed risks are seen as negative and to be avoided. An approach that supports people to take reasonable risks can have opposite effects, permitting them to move about in a care setting when provided with the support they need. The range of attitudes depends on different meanings being applied to ‘risk’, and is thus culturally embedded.

Cultural factors have been cited by researchers trying to explain why many older people tend to be sedentary (Harvey et al., Reference Harvey, Chastin and Skelton2015) and do not engage in physical activity. For example, the survey by Crombie et al. (Reference Crombie, Irvine, Williams, McGinnis, Slane, Alder and McMurdo2004) found that although most older respondents (aged 65–84) saw the health benefits of physical activity, more than half did very little or none. Their beliefs about what they needed to do diverged from norms suggested by health practitioners. Crombie et al. (Reference Crombie, Irvine, Williams, McGinnis, Slane, Alder and McMurdo2004) conclude that belief – cultural – change was needed to increase physical activity among this group. The Australian study by Booth et al. (Reference Booth, Owen, Bauman, Clavisi and Leslie2000) identified further contextual cultural factors, including the set-up of neighbourhoods, the accessibility of facilities for older people, and whether a person had a supportive and sociable network. Research in California by Santariano et al. (Reference Santariano, Haight and Tager2000) similarly found that older people's explanations for their lack of physical activity included living alone, limited resources and lack of interest.

Further support for the need to understand physical activity of older adults in its cultural context appears in cross-national comparative research. Examples include Gomes et al. (Reference Gomes, Figueiredo, Teixeira, Poveda, Paul, Santos-Silva and Costa2017), who find significant variation between European countries in the extent of physical inactivity, and the systematic review by Sun et al. (Reference Sun, Norman and White2013) which, despite identifying difficulties of measurement, suggests that there are significant differences in older people's physical activity in different countries, and also changing patterns over time in particular countries.

Care home cultures

Older people living in care homes are increasingly impaired and, in particular, levels of cognitive impairment are rising (Matthews et al., Reference Matthews, Arthur, Barnes, Bond, Jagger, Robinson and Brayne2013; Information Services Division, NHS Scotland, 2018). The care home population therefore includes some of the most marginalised people in modern societies, who experience culturally driven stigma attached to their ageing, their dementia and other impairments, and their perceived deficits, including that of being apparently unable to sustain independent life. Higgs and Gilleard (Reference Higgs and Gilleard2014) suggest that ‘fourth agers’, that is, people who are experiencing ‘real’ old age with its expectations of decrepitude and dependency, and who may be living in care homes, are at a lifestage in which they are ‘ageing without agency’, in which their lives are managed by others and not by themselves. They see this perspective as dominant and culturally embedded, as well as reflected in research literature whose emphasis is on the high costs and perceived social burden of this population. They echo Gubrium and Holstein (Reference Gubrium and Holstein1999), who observe that the idea of a nursing home provides a particular frame for representing aged bodies as decaying and therefore, by implication, not physically active.

Research conducted within care homes, however, also indicates some different thinking. Killett et al. (Reference Killett, Burns, Kelly, Brooker, Bowes, La Fontaine, Latham, Wilson and O'Neill2016) found that within care homes, there was variation in terms of whether the predominant cultures were task-focused (cf. Lee-Treweek, Reference Lee-Treweek1997) or people-focused (cf. Strandås et al., Reference Strandås, Wackerhausen and Bondas2019): where they were people-focused, quality of life for the residents appeared to be better. Other work (Poyner, Reference Poyner2018) indicates that some care staff are committed to delivering person-centred care, even where there is pressure within the care homes to emphasise timely completion of tasks. Furthermore, McColgan (Reference McColgan2005) demonstrates that care home residents with dementia may work to maintain their control and privacy in their efforts to identify and maintain a particular seat in a care home lounge, illustrating agency beyond that described by Higgs and Gilleard (Reference Higgs and Gilleard2014).

That care home cultures are varied and experience change and resistance coming from various quarters indicates the complex challenges of effecting cultural change. Within a care home, culture is continuously negotiated through everyday interactions; staff may be resisting or supporting the predominant culture, which may in turn be more or less responsive to individual needs; residents may resist dominant practice and exercise their own choices in often small and subtle, but nevertheless significant, ways. Promoting cultural change therefore requires an understanding of care home cultures as varied and dynamic, and an appreciation that residents and staff are active agents.

Physical activity in care homes

Attempts to promote physical activity in care homes have been driven by evidence of benefit, such as preventing falls. For people with dementia, recent research predominantly conducted in care homes has found increasingly that physical activity can assist with performance of activities of daily living (ADLs), thus helping maintain independence, and indications (though little evidence) that it may also improve cognition (Forbes et al., Reference Forbes, Forbes, Blake, Thiessen and Forbes2015). Recent policy and practice have also emphasised potential benefit. For example, the Scottish Care Inspectorate's (2015) Care About Physical Activity (CAPA) Guidance promotes the perceived need for people in care homes to be more physically active. The Alzheimer's Society (2019) promotes physical activity for people with dementia, including those with ‘later stages’ of dementia, whilst cautioning that people should not over-exert themselves. These initiatives generally treat physical activity as an ‘add on’ to everyday life. Exceptionally, there is a focus on promoting increased movement in a more integrated fashion, referring, for example, to encouraging participation in ADLs, as the CAPA guidance does.

Our scoping review (Bowes et al., Reference Bowes, Dawson, Jepson and McCabe2013) included research with service providers, which suggested the merits of a broader conceptualisation of physical activity, encompassing everyday moving about and everyday tasks, as well as more formally organised activities. In the research reported here, this perspective was adopted to enable an overview of all movement in care homes, extending the predominant focus in literature on ‘physical activity’ conceptualised in a rather compartmentalised manner. We consider movement in its context, as part of daily life in which care home culture is expressed and negotiated and in which staff and residents are actively engaged, whilst also reflecting terminology used by participants and by other researchers.

Movement cultures in care homes: the paper

Accordingly, this paper rests on the following premises. Physical activity in older age is influenced by wider cultures relating to ageing, and what older individuals are expected to do/capable of doing. These cultures form a context in which care homes, whose residents are among those most impaired as they age, exist. Physical activity has been promoted as desirable in older age, including for people in care homes. Despite strong contextual cultures which suggest care home residents are passive and ‘done to’, there is evidence that they, along with those who work there, are actively engaged in negotiating care home cultures. The paper pursues understanding of what movement is already occurring, its place in care home cultures, and the ways in which residents, staff and others connected to care homes negotiate it.

Methods

We aimed to achieve a multi-perspective understanding of movement in care homes through exploring perspectives of those involved, i.e. residents, staff (including ‘domestic’ staff) and others who came to the care home, including family members. Their perspectives and experiences were ascertained through interviews, conducted within the care homes. We had planned to observe physical activity in communal areas of the care homes, but the Social Care Ethics Committee felt this would be too intrusive. Instead, the multiple perspectives provided in the interviews were used to build an overview. The interviews were supplemented by field notes taken by the interviewers concerning the ambience of the care home, and any particular issues on the days of fieldwork.

An initial visit to the care home introduced the researcher, and set up an interview with the manager(s). Front-line staff, residents and family care-givers were recruited purposively by the researcher during a subsequent visit, following provision of information about the project. Managers were not made aware of which staff members, residents or family members were taking part in the research and were not involved in their recruitment, beyond helping circulate the information for potential participants. Researchers were trained to assess the capacity of residents to give informed consent, and conducted an assessment for each interviewee.Footnote 2 All those who took part were assessed as capable of providing informed consent, and this was confirmed during interviews using process consent (Dewing, Reference Dewing2002). Each interview involved one participant and the interviewer, and each participant took part in one face-to-face interview lasting between 20 and 60 minutes.

Table 1 lists the number of interviews achieved in each care home according to category of respondents.

Table 1. Interviews completed

The five care homes included were located in Scotland (two) and England (three). They ranged in size from 27 to 85 residents, and all included specialist provision for people with dementia. All were owned and run by care companies and included residents who were publicly and privately funded. They were recruited using publicly available information to identify homes located in either country which cared for people living with dementia, and were purposively sampled for variation in size.

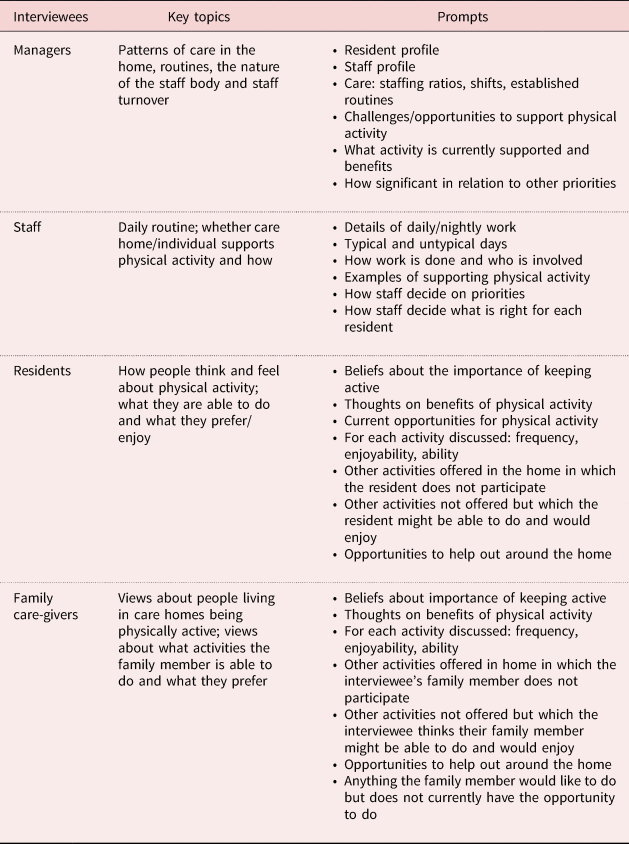

The interviews were concerned with respondents’ observations and experiences of physical activity within the care home. Table 2 provides an overview of the interview topics covered with each category of interviewee.

Table 2. Interview topics and prompts

The interviews were conducted by skilled researchers (AD, CGA and RJ) who sought to ascertain the views of the different categories of respondents, emphasising people's own views about movement, without pre-empting responses. The topic guide was used to stimulate conversation, starting with a general perspective on life in the care home, and moving on to consider movement. Interviewers allowed respondents to speak about movement in their own way, and used a variety of terms – ‘physical activity’, ‘movement’, ‘moving around’ – to enable respondents’ own representations of movement.

Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Data were collated and managed using Excel spreadsheets. Following the recommendations of Braun and Clark (Reference Braun and Clarke2006) for thematic analysis, all the authors read early transcripts in an iterative process to inform later interviews and to sharpen the focus of the interviews onto movement in the care homes. In terms of informing further interviews, early in the fieldwork process we identified a list of prompts (Table 2) to ensure we obtained detailed information on movement opportunities, barriers to movement and opportunities for increasing it. Activity supported, potential activity and activity not supported were all included, and different relevant tasks, times, opportunities, ideas and practices were considered.

Thus, the interview schedule contained a list of initial topics, used as theoretically driven initial codes (Braun and Clark, Reference Braun and Clarke2006). Once the interviews were complete, the transcripts were coded by the research team members using the initially identified codes, with additional emerging codes inductively added to the list as they emerged from the data. Codes were then considered across the care homes, comparing them and identifying the kinds of variability that existed to identify organising themes for the analytical account which follows. For example, one of the initial codes identified concerned the role of people outside the care home in supporting or facilitating movement. Following the coding process, this code, when linked with other, related codes, distilled into a discussion of the theme of boundaries of the care home and how these were negotiated and crossed (or not crossed) in relation to movement. Data saturation was reached with no new themes emerging towards the end of the analytical process. The account of movement in the context of care home cultures that follows thus emerged directly from this analytical process.

Validity, reliability and rigour of data and analysis were assured through processes of team working, checking back, interrogating negative cases and building data saturation to support the interpretations given (Morse, Reference Morse, Denzin and Lincoln2018). We acknowledge that, as in all qualitative, interpretive research, other interpretations may be possible: however, the care taken to interrogate the data thoroughly gives us confidence in the interpretations offered in the paper.

Findings

Our presentation of the findings reflects the core themes that emerged from the data analysis. Together, they build a description and understanding of how movement is played out in care home cultures, that is, how it is underpinned by values, facilitated or constrained by boundaries, performed in everyday actions and interactions, and contextualised in the organisation.

Beliefs and values

Beliefs and values about movement in older age were expressed in all five care homes. In all of them, there was a range of views. Predominantly, there was a belief among staff that older age, and particularly having dementia, made movement challenging:

I worked upstairs it was quite difficult to keep them interested because of their dementia. It is slightly different needs. (CS1Footnote 3)

Residents’ physical and cognitive limitations were presented as barriers to be overcome, with a clear default to speaking about limitation rather than capacity or ability:

We used to play carpet bowls and do all sorts within the home, but I am afraid his dementia is progressing and his ability to function has reduced. (AF1)

They will not do a great lot, but it is giving them the opportunity to wash themselves instead of you taking over and just assuming that they cannot wash themselves – give them the opportunity… (AS3)

Some staff and relatives went further, perceiving movement as inherently risky, and seeing risk as a barrier to promoting it. With dementia, there were suggestions that risks automatically increased:

We do have to keep people downstairs sometimes because they constantly walk up the stairs, which would be a massive risk if they went up and somebody did not go with them and they attempted to come down. (BS1)

You have to be watchful. They need to be guided. Probably with dementia they need individual [attention]. (BF2)

Movement was in some cases simply not something that staff were thinking about, and when they did consider it, they thought of it as an ‘extra’, somehow separate from day-to-day life or something for which others, such as activity co-ordinators, were responsible. In these examples, staff referred to visiting facilitators, and a manager perceived this issue, considering implications for different attitudes that she tried to promote among staff:

There could be an entertainer in, or the girl who does the exercises might come in, or someone from the Alzheimer's Society in, or they could be out somewhere to a tea dance or something like that. (AM1)

We constantly need to work with our staff because activities should be part of their daily routine/as part of their daily job role. Whereas, at times they see it as the activities person who really is responsible for that. Simply, instead of using a wheelchair for quickness, walk slowly to and from the dining room or to and from the toilet and this is all mobility. I do not want them to see that activity is some sort of special activity that they need to do. (DM1)

The emphasis on everyday movement in the manager's comment is unusual.

In a minority of cases, staff considered possibilities rather than limitations and thought of risk not as something to be avoided, but as something that could be managed. These staff tended to emphasise capacity rather than limitation:

I try telling them that they have to [do] something and if they help me it will be quicker and it will be good for them and they will be doing some activity. Sometimes it is okay, but it depends. (DS4)

Their capabilities are limited, but if they are only doing a little bit it is better than doing nothing. (CS1)

At the same time, all the care homes at managerial level (such as DM1, above) and amongst staff emphasised the importance of movement for residents, most often in relation to health benefits, but also self-esteem, quality of life, independence and dignity.

Residents and relatives also recognised the benefits of movement, as these examples indicate, emphasising the maintenance of physical condition:

It is important to get exercise physically because if you just sit about and you are not doing very much I think you tire more easily. (ER1)

My daughter is always moving his legs and telling him to feel his toes. We do that with him every time we are here … It makes us feel better if we see him absolutely doing something as opposed to just getting in and out of his zombie-like [routine]. (EF1)

It was clear that in some cases, this perspective had spread strongly through the staff group, whereas in others, attempts to promote these views had been less successful. This manager compared two care homes:

Where I was previously their idea of activities is providing a couple of hours three times a week. Since I came here to work I can see the benefits of what they provide … seven days in a week, especially for people with dementia is vital. Busy minds are happy minds. (BM3)

Staff felt in some cases that women and men needed to be engaged differently, e.g. suggesting that women might enjoy helping with laundry or mealtimes, whereas men might prefer gardening: the reflection of wider societal stereotypes and expectations of gender roles is obvious here:

They have actually started a men's afternoon on the Thursday, which I think is great … They had it for men only because my husband was a man's man – football, fishing, work and sports. (AR1)

I might like sewing, knitting and crocheting. [Man's name] might not like any of those. He might like making models. We have tubes that connect together that the men seem to like to do – plumbing type things/putting pipes together. (BM3)

Residents were keen to retain their mobility, which they saw as linked with retaining their independence, whilst acknowledging issues:

I am really comfy at the moment. I have been round the corner for my round of walks and have done my exercises. (DR4)

I had a stent put in there for my heart … I can still do it, but I do not like to push myself too much in case I make myself bad, if you know what I mean – make myself poorly. (AR2)

There was also resistance to some kinds of movement. For example, in care home A, the manager considered that residents who had set tables and prepared meals all their lives were ready now for someone else to do that – possibilities that appropriate movement for these residents might be getting involved with daily chores seemed limited. This attitude was also displayed by staff, indicating low expectations:

Some residents’ attitude is no, they have done their fair share of housework and they are not going to do any … A lot of them will say they have done years of that and cannot be bothered to do that now. They [staff] would say that why should the resident be doing it, they are 85 years old and they should not be making a bed. They do not see that they might want to do it. (AM1)

Residents themselves might also respond negatively to the suggestion of helping with household tasks. One, for example, opined:

I could not think of anything more boring. (CR3)

In other cases, they were more positive. This resident, as reported by a manager, had surprised herself with the improvement movement had brought:

She was not able to stand and use her legs, but with doing her daily exercise … she has actually built up the leg muscles now so that she can stand to transfer and stand to walk maybe four or five steps, which is amazing and she is so chuffed with being able to do that. (CM2)

Boundaries

All the care homes had some links with people and organisations beyond their walls, such as visiting staff, community members and organisations, friends and relatives of residents. They could be considered as being at the centre of networks of relationships that reached outwards to varying extents. Managers and staff from three care homes identified these examples:

There is an organisation … coming down next week and they are going to be planting out in the garden … We have had a lot of different schools that have come in and done a lot of stuff. You saw the mural out in the garden and that was done by the [name] school and they actually built all the planters. We are very lucky that we have forged these links with these people. (CM2)

We do have a lot of activities people coming in. We have a lot of singers come in. Yesterday we had [organisation name], which is quite good. She plays some music and she has a great big parachute-thing and she makes them lift it up and things like that … Last week we had a panto. (AS2)

We have people come here (students, kids) – they have a lot in here compared to my previous home, this home is brilliant. (DS4)

The last example is of a staff member who particularly valued the external input.

However, those inside care homes had varying perceptions of external, visiting staff who were sometimes engaged to facilitate movement. Sometimes they were welcomed, sometimes seen as rather a nuisance or distraction, but always as having a particular role concerned with movement, brought in as a special activity from the outside world, an import to the culture of the care home.

Others who came into the care homes included residents’ visitors, family or friends. Several care homes reported that visitors took residents on outings, some of which involved movement, such as walks. This resident enjoyed her daughter's visits, which provided opportunities to move about:

AR1: My daughter visits almost every day. She is very good.

Interviewer: Do you go out together?

AR1: Sometimes, yes, we just have a little walk around.

In some cases, visitors could be perceived as disruptive to the routine:

There is probably one resident who has a solid routine because the rest have visitors that come and that mixes up your routine … I just mean if you were to set to do something say morning aerobics with them, you could not do it. (ES4)

Staff represented outings as positive and beneficial to residents, though they did not often see the movement dimension as part of the benefits. They were more likely to refer to stimulation and sociability than to movement. They also noted that the visitors were able to do things with residents for which staff simply did not have time:

The activity co-ordinator also involves them [relatives and friends] … She encourages them; she has an excellent rapport with the relatives also and they quite often come and help her out or help with their own relatives or loved ones. If they do an outing, they are also there to escort and to help. (DM1)

Volunteers were seldom mentioned, but were identified as additional links with the external environment.

Both residents and staff could cross the physical boundary of the care home, and potentially be involved in movement outwith the building but there were differences between residents that were able to cross boundaries and those that were not:

Now that it is summer and sometimes a bit nicer sometimes I will take a few of the mobile ones down to the garden leaving some of them in their chairs. (ES4)

Staff, of course, crossed the boundary every day, to and from their workplace. Their jobs were represented as being physical, involving hard work and they did not discuss additional movement beyond their work.

Residents appeared to be largely dependent on others for getting away from the care homes, such as through outings with their visitors (above) or through organised outings to places of interest or community facilities such as local parks:

Sometimes we take the residents down. There is a park that is a five-minute walk away – it is a really big park with a pond. When the weather gets nicer some staff will come in (even on their day off – I have done it) and take one or two residents down to the park and feed the birds. (CS4)

I still go to the church. It is pretty near, but you have to go by taxi sometimes … My friend asked and said she would come and get me, but I said that quite often I get a taxi because it puts people out sometimes. She takes me home though. I would not want her to miss it because I was late. (ER1)

The weather was also often a perceived boundary for staff and residents, reflecting risk aversion, and conceptualisations of residents as vulnerable. Going outside was conditional in these examples:

We are hoping to get good weather to take a walk round the … park, which is not far from here. (ER1)

Yes, when it is nice the residents can go out. It is a secure garden … If it is warm enough then we go outside. It is as it goes along here. (BS1)

Furthermore, the work pressures on staff meant that, whilst they could welcome residents being able to go out, organising trips was additional and complicated work which they experienced as burdensome:

The activity team … might have activities organised for the morning where they can take people out somewhere, but there are 60 residents in the building so it is staggered depending on the activity. For instance, this week they were going [out] so they will have limited space in the minibus depending on who is walking and who is in a wheelchair. (ES3)

That is what the activities team is there for, but it is often the same people that go. A lot of our residents, it will cause more anxiety so then they often get, I am not going to say forgotten about, but they are more likely to do activities that we run here, as opposed to going along the hall [i.e. going out]. (ES4)

There were a few examples of more positive orientations towards boundary crossing, and taking advantage of external opportunities to support residents; for example:

They were getting a little bit agitated so one of the carers has taken him to the shop for a walk to, hopefully, distract. This happens quite often and usually a short walk to the shops will settle him; satisfy his craving for what he wants to do – for him wanting to go out. (BS1)

Actions and interactions

As they conducted their work, staff engaged in interaction with residents and with each other, and aspects of movement culture can be seen expressed, affirmed and contested during these interactions. There was variation in the extent to which staff engaged with residents in ways other than the direct delivery of physical care. In some cases, staff considered it important and as an integral part of life in the care home for them to engage with residents more personally and socially, engaging in conversation during care processes, and sometimes making a particular point of seeking out conversation and interaction, e.g. during afternoons. These kinds of interactions were linked with staff having good knowledge of residents, their backgrounds and interests, and taking a more individualised approach to their interactions, stressed in this quote from a family member:

If you concluded that physical exercise was a good idea and then people tried to make, say, [name] do physical exercise it could do more harm than good depending on his state of mind at that time. One has to depend a lot on the expertise and professionalism of the carers to gauge his mood … While physical exercise could be a terrific idea it would not necessarily be a good idea on any given day. (AF3)

In this case, the staff were perceived as sensitively responding to the resident and picking the right moment to encourage movement. Further examples could be seen where staff encouraged movement through joining in day-to-day activities, such as visits to the shops (see the example above from BS1 of boundary crossing) or care home chores, as in this example:

Sometimes when we are done I might ask someone if they want to fold some napkins. One of the ladies does sometimes wipe the tables down, but that is rare. … Another lady last week wanted to do some sweeping up so I went and got the broom and she swept up. (BS2)

Examples of staff who took such a person-centred approach to care and support could be found in all the care homes, suggesting the exercise of choice about the quality of interactions, whatever the dominant values.

With a focus on residents as individuals could also come resistance to movement, whereby staff would say that residents had rights and that they could not force them to do things they did not wish to do (including movement):

We ask him and one of the other mobile residents if they want to go down to the garden when we are taking people there and they say no. You cannot force people to do that. (ES4)

Some people that I have had in my unit would never want to [go] outside. No matter what you do they would refuse absolutely to go out. They are actually really happy being indoors and spending time on their own. They have capacity so I do not impose on someone like that. (ES3)

The fundamental staff skill that emerged through these comments was that of responsiveness to individual residents, building relationships with them and, through those relationships, sometimes supporting increased movement:

It is having the skill to get people involved in what is going on and making things happen for them because it is a long day sitting doing nothing, even if you are just talking to them. (CS1)

I bring in the trolley with cups and juice and keep everybody hydrated. Again, those that can we give them a cup and the ones that need help, we will help. (CS4)

Some staff found interaction with residents difficult, especially residents who were cognitively impaired. Their views of people with cognitive impairment, which emphasised incapacity, clearly influenced their notions of appropriate movement for people perceived in this way. People with dementia could be left out of activities, and therefore move about less, because they were seen as difficult to engage, as in these examples:

We ask them what they would like to do whether they would like to sing, a quiz or ‘play your cards right’, but there are only certain ones who will do it because of the level of dementia, again. Some are quite eager to do [activities] all the time whereas others will just sit there and will not participate in anything no matter what we do. (AS2)

I have not really thought about asking a resident to come and help set the table … It is hard with dementia. I cannot think of any of my residents that would be able to. (CS4)

Staff perceptions of residents influenced their inclinations to interact or not to interact with them, as well as the nature of interactions. For example, residents who were less inclined to ‘join in’ with activities could be represented as difficult, notwithstanding the interpretation given above of staff permitting residents to exercise their own choices. Thus, perceptions of residents as unable to be mobile, combined with risk-aversion as previously noted, could exclude them not only from movement but also from the interaction linked to it.

In other cases, staff felt that additional engagement with residents was burdensome, and a distraction from their core work tasks, especially where there was a routine approach to these. Similarly, movement that was not built into the routine was perceived as a problem, though not in this instance an insurmountable one:

After lunch the laundry has usually come up so I usually go round with laundry. If there are no activities, I usually take one lady who likes to be kept busy to walk with me and the trolley. She is a wanderer and so it is better she is wandering with me. (ES4)

Linked to these observations are findings on residents’ frustration and anxiety, which was reported widely. In two care homes (A and B) movement was seen as a good way of helping with this:

Less behaviour, less agitation. If they are more active they are not thinking about anything else. They are not getting agitated; they are not thinking about home; they do not want to go home and they are not constantly asking about relatives. It keeps their skills up and it keeps their strength. (AM1)

While they are busy and active you are reducing the risks of slips, trips and falls, hazards and the agitation for them. Because it is a dementia setting you have a group of people who may all be wander-some then you physically need to keep them busy and keep them active. (BM3)

In care home C, the manager reported that a lot of frustration and anxiety was an indicator of problems with the care being delivered, seeing it in a much more holistic manner: in this care home, physical activity was also seen as an integral part of daily life:

Every single thing that they do is an activity and it is raising that perception of it. (CM2)

Residents did not necessarily conform to care staff expectations. They would not automatically do as care staff wanted them to, e.g. resisting getting involved in household chores (see above) and being reluctant to move about the home, preferring to spend their time in their rooms. They had their own views on the extent to which they were able to move about. They might view themselves and other residents as inactive:

We are developing into a sofa society. Everyone seems to fall asleep quite easily because we are lacking in exercise physically because people are older themselves. (ER1)

One resident talked about moving through the different rooms in the home, as if following the sun:

I either go in there or there is the other part that I come into … Yes, that is more or less it with the sun here and then through there. (BR2)

Whilst residents in general lacked active roles in the care homes, and their voices did not influence policy, practice and activities in any formal way, they did nevertheless exercise individual preferences and make their views known, if only by resistance or refusal, for example:

We got a new lady in about two months ago and I thought we were going to have to get her involved in drying the dishes or something like that. We have tried to get her to help set the tables after breakfast and lunch, but no. (AS2)

In the eyes of the staff member, this was a challenge, an example of interaction efforts not working and therefore movement not happening. For the resident, it may indicate the exercise of agency and making a choice about movement. There was no evidence of other efforts to ascertain what her preferences might have been.

Organisational contexts

All the care homes were experiencing staffing problems, both managerial and frontline, as well as in relation to specialist staff such as activities organisers. Reported problems of under-staffing, staff sickness and staff turnover were commonplace, indicating levels of flux and pressure that seemed to mitigate against attempts to deliver the best possible care (which all the care homes were trying to do). Where pressures on staffing were particularly acute, movement was an issue that could easily be put to one side in favour of perceived ‘essential’ tasks such as personal care and mealtimes:

If they are rushing round and they have not had time, the first thing to go is the activity. They will not let their paperwork go because, obviously, they have to do their paperwork and they will not let charts go. (AM1)

A lot of it depends on the day and if you are fully staffed. You could get more done – we could do more activities if everybody is in. (BS2)

Care homes varied according to whether responsibility for movement fell to one person, such as an activities organiser, whether the whole staff group was expected to take it on, or whether no responsible person or group was identified. Where no-one was specified, this certainly appeared to marginalise movement. This could also occur when one person was specified, especially if they were a visiting staff member. Where it was embedded and seen as everyone's responsibility (as in care homes C and D), and staff understood and explained this, there were more opportunities for residents and they were more likely to engage:

After breakfast we usually have two activities ladies and they usually do something … They do a lot of activities. Today, they went outside because it was beautiful weather. They were playing ball and there was singing. (DS4)

Where care homes had strict routines, these tended not to include movement and to be very focused on care tasks. The imperative would be to ensure residents were ‘lounge-ready’ by a particular time, and hence residents might be hurried to the lounge in a wheelchair, rather than being supported to walk there. Staff accounts of their shifts mostly reflected a standard routine followed every day. Each part of the day could be further broken down into a series of routine tasks:

Then I took her into the bathroom and gave her a nice shower (always communicating); got her dressed, her hair, and her teeth, made her look pretty and took her to the dining room for breakfast … Again, it is the same routine – get things ready, washed, dressed, creamed, teeth and hair – put them on a wheelchair and then again to the lounge. (DS1)

In all the care homes, there was management-level commitment to improving movement. In itself, this could not be seen to have encouraged additional activity, as staff had not necessarily embraced the message. But there are in our data indications that where there had been effective work embedding the commitment, changes were occurring:

We always ask relatives on admission whether they would like mum or dad to have physio. (DM1)

I suppose it is assisting themselves is probably the main thing because even if they are just sitting, the movement of getting a fork or any movement is good movement, and it is the walking up and down to the lounge or dining room. (CS4)

The organisation of space in the care homes could also be seen to constrain or facilitate physical activity, especially in terms of movement around the spaces and whether or not there was accessible outside space. For example, strategically positioned places to sit could support people who could move around for short distances, as compared with a long empty corridor that eventually led to a lounge, too distant for some to reach unaided. In the case of outside space, whether residents could go there without support or whether staff had to find a key, help them through the door and stay with them whilst they were out, clearly made a difference to whether the outside space could be considered an opportunity for movement. The ways in which use of space was managed have to be seen as part of the care home culture, a result of decisions made and practices engaged in: in the care homes included, there were no un-modifiable spatial constraints (such as no outside space at all).

Care home organisations do not, of course, exist in isolation, and are part of a wider policy and regulatory regime. Issues identified included limited resources (with the exception of one well-resourced home), risk management processes, and health and safety regulations. A focus on paperwork was commonly cited as a reason that activities were not undertaken:

It takes so long to do all the care plans. By the time you have done all the books that are in their rooms and all the books in the office that is time could be spent doing activities … that really annoys me – it is so silly. (ES4)

The care homes, however, varied in the way they deployed resources, including what tasks were prioritised, their attitudes to risk management, and their management of health and safety regulations. For example, locking doors was commonly represented as a means of preventing mishaps, whereas in care home E, staff made a point of emphasising that doors were never locked. This manager reflected on the extensive demands on staff, and the duty of managers to help staff deal with these:

As a manager you really have to think outside the box. You have to give the staff the time. It is not just all about care plans, documentation – that is a given – that needs to happen – that is part of who we are, but it is all the extra bits and pieces that we do. (CM2)

Discussion

Our findings on the theme of beliefs and values around movement across the care homes confirm, reflecting the literature, that views about ‘physical activity’ are culturally framed, rather than simply echoing narrow health guidance, for example. They incorporate ideas about dependency of people living in care homes. This in turn implies that movement cannot be approached as a neutral behaviour that can be readily amended. Managers, staff and residents are invested in or resistant to movement in nuanced ways that reflect underlying beliefs and values. They also reflect or contest possibly dominant views, including those of care home management, but also wider societal views about expectations of older men and women and the fourth age. Our findings partially support previous literature on views about movement in older age (such as Phoenix and Tulle, Reference Phoenix, Tulle, Piggin, Mansfield and Weed2017) and ‘fourth age’ cultural expectations (Higgs and Gilleard, Reference Higgs and Gilleard2014), but also provide a more optimistic picture of possibilities for change, identifiable in the varying perspectives.

Care homes are, of course, physical entities, but in terms of external individuals and groups who may or may not be engaged with them, our analysis has explored their socially negotiated boundaries, providing additional insights into the cultures of movement and particularly how these may effectively discount potential opportunities for movement that boundary crossing might provide.

The rather limited extent to which the boundaries were crossed in our study suggests cultures leaning towards boundedness of the care homes, whereby residents become ‘marked off’ from society, considered no longer to need or want an integrated position (as in Higgs and Gilleard, Reference Higgs and Gilleard2014 – the fourth age). In terms of movement, this closure appears to reinforce sedentariness, in that residents simply do not go out much and are not expected to do so. Indeed, there are elements of hostility towards going out, not necessarily from individuals, but from the way that the boundaries are set and operated. This closure is further enacted within the care homes, where some residents take part in activities and others do not.

Discussing boundaries, we also established that care homes could be seen as part of a network of wider social and community connections, and that the extent of engagement with these could make a difference to movement in the care homes. This departs from the expectation that care homes are cut off from wider society, and indicates potential resources that could support change. In terms of the Dahlgren and Whitehead (Reference Dahlgren and Whitehead1991) model, care homes and their residents have to be considered as embedded within the full gamut of social determinants of health, including their cultural framing.

Actions and interactions within the care homes are at the core of the cultures, and in observing them, the cultures of movement become especially clear. The values and beliefs can be seen reflected in the ways people work and live their lives. They actively construct and reconstruct their views of the world as they engage in action (including movement) and interaction between staff and residents. This supports the argument that cultures are made in daily life and scrutiny of actions and interactions reveals the role of movement within the care homes at the most immediate level.

Within the interactions, therefore, we can see a range of behaviours and actions that indicate care home cultures are not homogeneous or static, but that people challenge or promote particular behaviours daily. The role of movement – what activity and whether people engage in it – can be seen in our findings being negotiated through the variable relationships that exist in the care homes. It is apparent that relationships and interactions are integral to movement and its role. We observe variations in amounts and kinds of movement in the care homes, but similarities in the kinds of negotiations involved.

Our study, supported by Killett et al. (Reference Killett, Burns, Kelly, Brooker, Bowes, La Fontaine, Latham, Wilson and O'Neill2016), implies that actions and interactions in the care homes are the sites where movement is encouraged or discouraged, facilitated or restricted, enabled or prevented. Actions and interactions draw on the value base within the bounded context, and can confirm or disrupt and challenge it.

Looking at organisational aspects of the care homes, various barriers and facilitators to movement for residents can be identified. The way things are organised is, of course, culturally grounded and influenced, and in turn may reinforce existing cultures or provoke change. We find that organisational factors do influence movement, subject to the underlying contested values, negotiated boundaries, actions and interactions in which the social actors are engaged.

Aspects of care home organisation, such as rigid routines, external regulation and pressure on staffing, could be scapegoated as the fundamental problems in restricted movement. However, our analysis suggests that they are only part of the picture, factors that need to be considered, but which cannot be seen as wholly causative and are certainly framed and influenced by cultural influences. For example, our findings suggest that care homes work with regulation in various ways that make it more or less constraining. Thus, organisational issues, again similarly to Killett et al. (Reference Killett, Burns, Kelly, Brooker, Bowes, La Fontaine, Latham, Wilson and O'Neill2016), could be seen as facilitating or constraining, but they are also influenced by decisions made in the care homes, and the conduct of everyday life.

All these factors contribute to an understanding of care home movement cultures which, we suggest, has to be the starting point for attempts to challenge lack of movement and promote its increase. Lack of such understanding, we suggest, may explain the difficulties in improving movement in care homes identified in our earlier literature review (Bowes et al., Reference Bowes, Dawson, Jepson and McCabe2013).

Conclusion

We have demonstrated that increasing movement is significantly an issue of cultural change. It is possible to identify, and our research has done so, potential facilitators and constraints that may be embedded in the culture of any particular care home. For example, we identified care homes with values committed to person-centredness and embedded movement, and care homes where there was ownership, at least at management level, of movement promotion. Care homes had assets that could be used to support movement, both internally and externally. Constraints were also identified, such as low expectations of resident capacity, focus on routines, closed boundaries of the care home, lack of engagement between staff and residents, and failure to take ownership of movement, seen as a prerogative of specialists, or peripheral to the core business of care. Essentially, both the facilitators and the constraints are embedded in the care home culture.

In considering the implications of these findings for promoting change, we can identify three principles. Firstly, any intervention has to start from an understanding of the local culture of movement. Arguably, the people who know most about this and have the best understanding of it are those who live and work in the care home: any intervention therefore needs to engage directly with these people and involve them in its development. Secondly, the intervention will need to accommodate the different perspectives and experiences that exist within the care home, recognising (and probably challenging) staff practices and ideas, and respecting the wishes and preferences of residents. Thirdly, it will need to engage with existing actions and interactions of staff and residents. The intervention needs to engage and often challenge existing cultures of movement in order to make any lasting difference.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Healthcare Management Trust for funding the research on which this paper is based. We also thank all those who took part in their research for their generosity with their time and thoughtful contributions.

Financial support

This work was supported by the Healthcare Management Trust.