The aim of the preceding holistic account of the Attalid fiscal system has been to recast the so-called liberal or bourgeois monarchy as a line of administrative savants, who won an empire not by the spear but by making the cultural reproduction of local constituencies, the elite of the gymnasium, the polis community, and emergent civic organisms in rural Anatolia, all depend on efficient taxation. When we view the Attalid kingdom from this perspective, the kings themselves fade out of view – just as they do on their own coin types.Footnote 1 Yet, if we follow the taxes back to the metropole, the relationship between culture and power only increases in salience. For we find the Attalids taking a hyperactive role in collecting, curating, producing, and circulating cultural artifacts.Footnote 2 From the Library of Pergamon to the Academy of Athens, tax revenues funded the Attalids’ spending spree on culture. Taxes allowed the Attalids to capture pride of place in the archaeological record of Panhellenic centers such as Delphi and Delos. In addition, the manner in which the citadel of Pergamon and its hinterland were developed with the proceeds of empire also represented a cultural statement to would-be subjects. No picture of Attalid political economy can be complete without a consideration of the role of culture in determining the outcome of the Settlement of Apameia. In other words, did the cultural pageantry and positioning of the Attalids contribute to the ideological integration of the new state?

According to a standard reference article on the dynasty, cultural ideology masked real weakness, while monuments and bibliophilic lore have obscured the fact that Pergamon controlled neither its destiny nor its notional territory.Footnote 3 Again, the scale, costliness, and prestige of Pergamene cultural output would seem to belie such pessimism about its material basis. Yet the subject of an Attalid Kulturpolitik, of a commitment to “culture as policy,” has largely been approached as a matter of understanding the subtlety, even genius with which these unpedigreed latecomers to royalty constructed authentic Hellenic cultural credentials, not only by patronizing Athens and the Panhellenic sites of Old Greece but by cleverly building bridges of fictive kinship to Arkadia and coopting the Muses of Thespiai.Footnote 4 Meanwhile, in Anatolia itself, we risk losing track of the kind of local reception that postcolonial scholarship has recovered for the other multiethnic kingdoms such as Ptolemaic Egypt and the Seleukid Near East. And yet it is this internal, Graeco-Anatolian – in ancient terms – Asian audience that counts for assessing the impact of the cultural content of Attalid imperialism. However, unlike Hellenistic Egypt and the Near East, Anatolia was home to both indigenous Greeks and indigenous non-Greeks. Here, the encounter with the subaltern was strange and unique. In fact, mutual intelligibility was unparalleled, especially since a large population of Phrygians spoke the Indo-European language closest to Greek.Footnote 5 Therefore, neither inauthenticity nor cultural appropriation is a suitable lens through which to view the Attalids. In the Mysian context, Greek identity was also bound to take its own forms, distinct from those of the mainland and the islands of the Aegean. Helpfully, by providing a cultural profile of the Greeks of the kingdom’s geographical core, recent studies of the Classical polis network of the Kaikos Valley and of collective memory and cult in Pergamon under the Gongylids shed light on specifically local resonances of the Telephos myth.Footnote 6 We must also consider what particular currents of Panhellenism issuing forth from the Library may have meant for an audience of East Greeks. For all their connections abroad, the Attalids could not afford to ignore cultural dialogue with the Greeks at home.

On the other side of the ledger, the extent to which the Attalids acted like Anatolian kings has been seriously underappreciated in accounts of their rise. In fact, the Anatolian substrate of Attalid cultural identity is rarely investigated beyond takedown references to the mixed parentage of Philetairos: his mother was a Paphlagonian of ill repute, and his father, on shaky onomastic grounds, is usually counted a Macedonian. In the Classical period, the lords of the Kaikos Valley had been Greeks and Persians, but the population was a mix of Greeks, who have left us a few Atticizing grave stelai, and, presumably, a silent majority of Anatolians.Footnote 7 In the Bronze Age, the region had lacked the Aegean connections of the Milesia or the Troad.Footnote 8 We must recall that for Herodotus Pergamon was not one of the eleven Aeolian poleis, and that for Xenophon, the citadel was still “Pergamon of Mysia.”Footnote 9 Of course, the muted Hellenism of early Pergamon informs the idea that the Attalids “emerged from the sidelines of history to become one of the dazzling centres of antiquity.”Footnote 10 Cruelly, the Anatolian cultural background of the Attalids is thereby rendered invisible when it should help us explain how Pergamon transformed itself from vassal to continental empire, adroitly governing both the coastal poleis and the inland ethnê and demoi. Measured against the coastal cities of the deltas of the great Anatolian rivers – Smyrna on the Hermos, Ephesus on the Kayster, and Miletus on the Maeander – early Pergamon is often rated a Hellenic backwater. Yet it was no accident that a city-state on the margins of two cultural spheres emerged with an empire. The Attalids represent a culturally “bilingual,” distinctly Anatolian response to the diasporic Graeco-Macedonian model of empire. This was not a settler state, and the Attalids were not “chameleon kings,” who manipulated local expectations.Footnote 11 In a groundbreaking study, Ann Kuttner has shown that the creative incongruity of Pergamene eclecticism in art and architecture is riven with Anatolian materials, motifs, and topophilia. As she points out, the Attalids continually proclaimed themselves something other than Hellenes.Footnote 12

The goal of this chapter is to take stock of the Attalids’ cultural diplomacy to their own people. This means taking seriously the dynasty’s claim to rule a place called Asia, which is part of, but also apart from, Hellas. That claim is voiced already in an epigram of Philetairos, inscribed at Pergamon on an Olympic victory monument, which makes a distinction between Hellenes and Asians.Footnote 13 Yet we find the programmatic statement reflected in the 184/3 decree of Telmessos in Lycia, a document for the scramble that pitted the Attalids against Anatolian rivals from Bithynia and Galatia. The inscription recounts that Eumenes II, savior and benefactor, declared war and undertook danger “not only on behalf of those ruled by him, but also on behalf of the other inhabitants of Asia.”Footnote 14 Asia was the theater of war. The population of Asia looked to Eumenes for salvation. We can understand the ease with which such Pan-Asianism coexisted with Hellenizing tendencies only if we recognize the Attalids as the heirs of Anatolian kings such as Mausolus of Caria and Croesus of Lydia, occupying the same geographical niche defined by East Greece and the Anatolian steppe. We must avoid reducing the cultural universalism of the Attalids to an antithesis of Greeks and barbarians. This is the temptation of the mythic allegory of the Gigantomachy on the Great Altar and of the historical analogies of the Little Barbarians on the Athenian acropolis.Footnote 15 In mainland Greece, the Attalids joined the Aetolians and others in portraying victory over the Gauls as a replay of the triumph of a united Hellas over the Persians. Unsurprisingly, at Athens, Attalos I catered to the Athenian version of the mythic cycle, which also juxtaposed Trojans and Greeks, as well as Amazons and Greeks. Meanwhile, in their own kingdom, the Attalids invested in the prestigious legacy of Troy and leaned heavily on the support of Aeolian cities allegedly founded by Amazons. Therefore, we begin by investigating the intellectual orientation of the official Panhellenism of the Library of Pergamon, in order to reconstruct a few of the lineaments of the cultural dialogue between the Attalids and the Greeks of Asia Minor. Next, we consider ancient perceptions of the capital as an Anatolian royal city rather than an inauthentic polis, first, from the perspective of its tumulus burials and, second, from the vantage of its mountaintop palace and urban plan. Pergamene Panhellenism, then, emerges as the particularistic expression of the civilization of cis-Tauric Asia. Finally, we reevaluate the relationship of culture to power in Attalid interactions with new or potential subjects in the highlands of central and southern Anatolia. In places like Galatia and Pisidia, we come to see Pergamene Panhellenism as a truly universalistic expression: civilization in cis-Tauric Asia.

The Library of Pergamon

The Attalids had always courted intellectuals, but Eumenes II was the first to attract an academic superstar to the capital, the Stoic philosopher and literary critic Crates of Mallos. Crates arrived at an opportune moment: the physical setting of the Library, wherever it was, now took shape amid a flurry of book buying and book production on the city’s famous parchment.Footnote 16 In addition, an entire cast of Pergamene intellectuals now found themselves working for much higher stakes. As a Stoic, Crates must have cherished the opportunity to steer an ascendant king and the population of his new empire toward virtue and harmony with nature. He is best known for his work on the text of Homer, especially allegorical and lexical exegesis in pursuit of knowledge of the cosmos. For the Stoics, such knowledge on the global scale directly informed ethics on the local.Footnote 17 However, we sorely lack any idea of the librarian’s position on the ethical relationship of a wise man to his community of origin (patris). Yet the issue was a central concern of the Early Stoa, treated at length by Zeno of Citium in his Politeia. Building on Cynic critiques of norm and convention, Stoic cosmopolitanism reconsidered the act of political affiliation. Meanwhile, Pergamon’s territorial monarchy was faced with the task of securing commitments from subjects whose primary affiliation remained the conventional one, the community of origin.

Symbolically, as a vast store of cultural prestige, the Library contributed to the power of the dynasty. As a self-proclaimed kritikos, Crates busied himself with the creation of a classical literary canon.Footnote 18 This put the Attalids in direct competition with the Ptolemies of Alexandria. Emulation of Athens aside, Pergamon became a center of cultural production in its own right. For example, one suspects that the Library produced a royally commissioned, specifically Pergamene edition of Homer.Footnote 19 Yet if the Library, under the stewardship of Crates, made a distinctive ideological contribution to the maintenance of an empire, which, as I have argued, promoted local, civic identities and institutions, it managed to do so by blunting the hardest edges of Stoic cosmopolitanism. Early Stoicism had inherited a critical stance on the patris from Diogenes the Cynic. The radical stance of an early Stoic named Aristo recalls the view of Diogenes. Aristo is cited for the claim that “the fatherland [patris] does not exist by nature.”Footnote 20 And for a Stoic, what does not exist by nature is of no concern. Aristo, however, was a dissident, and Zeno and his immediate successors, principally Chrysippus, counseled politically active men. In principle, the true polis of wise men stretched beyond the boundaries of any particular city. In fact, the achievement of the ultimate goal (telos) of Stoicism entailed the dissolution of each individual city-state. That the true foreigner (xenos) was the morally bad was a belief held by Zeno, who placed virtue over institutions.Footnote 21 The realization of that telos, though, was safely set in the distant future. For the contemporary Stoic sage, to live a cosmopolitan life was to emigrate to the court of a king, even an enlightened barbarian, in order to promote virtue among the greatest number of people. Nevertheless, Chrysippean doctrine suggests the possibility of serving the fatherland and privileging its citizenship, if only as a worst-case scenario for a sage rendered immobile by circumstance. These ideas may have caused some embarrassment for later thinkers of the Middle Stoa, but they formed part of the intellectual background of Crates of Mallos. Later, too, arrived the more humanistic cosmopolitanism of universal community. The Stoicism of Crates would seem to have taken membership in the polis for granted, but harbored doubts about its citizens’ common destiny.Footnote 22

A more traditional attitude is in evidence in the writings of Arkesilaos of Pitane, an Academic and a client of Eumenes I, who began an epigram for a fallen friend from inland Anatolia, crying, “Far, far away are Phrygia and sacred Thyateira, your native land (patris), Menodoros, son of Kadanos.”Footnote 23 Plainly, no Pergamene school of thought existed.Footnote 24 Moreover, Stoicism seems to have gravitated back toward practical ethics under Panaetius, said to have been a student of Crates.Footnote 25 Rather, it is noteworthy that the intellectual climate of the Library contained an element of ambivalence about the more exclusive claims of the community of origin on an individual, even if the identity of the average Attalid subject remained rooted in place. Yet a different strain of scholarship, alive and well in the same Library, responded directly to that silent majority’s firm sense of place. This was what Rudolph Pfeiffer once termed “the new antiquarianism” of Pergamon, associated with periegetic art historians such as Antigonos of Karystos and Polemon of Ilion. Polemon deserves close attention, since we know enough about his oeuvre to try to reconstruct its target audience. Born a subject of the Attalids, he is widely believed to have been present at their court.Footnote 26 Like the Attalids, he was honored at Delphi, which he adorned with a history of its treasuries.Footnote 27 He too was deeply familiar with the tribes of Athens and the city’s acropolis, as well as cities such as Sikyon, dear to Pergamon. Yet the Panhellenism of an author nicknamed Helladikos encompassed scores of cities with little or no direct connection to the kings.

The titles and fragments of the works of Polemon point to an abiding interest in the histories of individual cities.Footnote 28 For example, he wrote books on the cities of the regions of Phocis, Lakedaimon, and Pontos. For each city, the antiquarian recorded genealogies, laws, institutions, festivals, and local lore. He wrote in an old, popular tradition, which had survived for centuries, usually alongside, but occasionally mixed in with the historiography of political affairs and military events.Footnote 29 Polemon aimed to distinguish himself from certain rivals in Alexandria by using autopsy to claim more accurate knowledge. He traveled to these locations and studied their monuments and inscriptions. One can imagine that the realia of his traveler’s accounts resonated with readers’ lived experiences and ritualized memories, perhaps more so than the erudite poems of the library-bound Callimachus.Footnote 30 The Attalids were famous for collecting art, and research such as Polemon’s will have lent their prize pieces robust object histories, a context that stuck to the statues accumulating in Pergamon through purchase and spoliation. In fact, in the presentation of art in the citadel’s sanctuary of Athena Polias, the Attalids pointed proudly to objects’ provenance, appropriating prestige without denying individual cities their own histories. The island polis of Aegina, under Attalid rule from 206, is a case in point. In the Pergamene sanctuary, two images from Aegina were juxtaposed side by side, one a classical work of the Aeginetan sculptor Onatas, in the Severe Style, the other, a Hellenistic sculpture by the Boeotian Theron, but inscribed, “(The image is) from Aegina” (I.Pergamon 48–49). The juxtaposition of old and new artifacts, in different styles, both from Aegina, gestured toward the particularity of that city’s history, continually unfolding. The local histories of Polemon, like the statues of Aegina, belonged to a Panhellenic cultural patrimony, now under Attalid management. As Kuttner points out, from our perspective, the notion of a common patrimony of the Greeks sits in tension with the Attalids’ admiration for historically located pedigree and respect for original place.Footnote 31

Polemon’s literary output can be considered a response to a crisis of Greek identity, even a reaction against the unmooring tendencies of conquest-driven migration and Stoic cosmopolitanism.Footnote 32 He wrote auto-ethnography for a Panhellenic public. The modern label “antiquarianism” misleadingly implies pedantry; these writings invoked the deep past to buttress contemporary attachments to communities of origin. The figure of Polemon is an important clue about the specific character of Pergamene Panhellenism, which reaffirmed local differences for imperialist aims. One can detect the ideology as early as the reign of Philetairos, who when dedicating in Thespiai and Aigai, employed each city’s local dialect.Footnote 33 With the increase in their power, the Attalids were able not only to deploy local knowledge but to expropriate it, occasionally right along with the hard currency of cultural artifacts. The paradoxical, even jarring effects of this policy are evident in the signal case of Athens. Attalos I could not convince a certain Lakydes, head of the Academy, to join his court. In an extraordinary gesture for a royal patron, Attalos bowed to the primacy of the place: the king built a garden in Athens for the use of the philosophers, known as the Lakydeion.Footnote 34 From Athens, the Attalids were also not at liberty to remove colossal masterpieces such as the Athena Parthenos or Promachos. In a novel twist, they made copies for their own acropolis.Footnote 35 Close study of the cult and sanctuary of Athena Polias, as well as that of Demeter and Kore further down the slope, shows Athenian influence but not slavish imitation. Imperial Pergamon evoked, honored, and emulated, but, contrary to a scholarly cliché, never claimed to replace or supersede Athens.Footnote 36

The Panhellenism of Polemon’s work is also noteworthy for its geographical limits. The Greek world, for Polemon, was a much smaller place than the effectively limitless domain once envisioned by Isocrates. The fourth-century philosopher had argued that education and acculturation could produce Hellenes, and by the second century, that vision was a reality. When Antiochos IV invaded Egypt, he was able to pick out the Greek residents of the polis of Naukratis, in order to award them each a gold stater.Footnote 37 Polemon, however, did not go looking for Greeks in Egypt. Whereas Polybius, for example, took the entire inhabited world (oikoumenê) as the stage of his history, or the narratives of earlier periegetes such as Herodotus and Hecataeus of Miletus wandered off into barbarian lands, Polemon’s setting was an anachronistic vision of the confines of Hellenism.Footnote 38 As is often remarked, he restricted himself to studies of the Greeks of the mainland, the Aegean islands, Sicily, Magna Graecia, and, indeed, East Greece. For a Hellenistic intellectual, these were noticeably parochial interests. The exceptions, Carthage and Caria, seem to prove the rule, since their earlier histories had been so intertwined with the Greeks.Footnote 39 Polemon’s project highlighted the differences between cities, celebrating the peculiarities of sanctuaries. Yet it also drew a boundary around a comfortably antiquated version of the Hellenic world, one which the Attalids now targeted for support.

Another view of this Panhellenic audience, with its strong local loyalties, emerges from a Polybian vignette about a boxing match at Olympia. It took place on the eve of the Third Macedonian War, as Greece faced the prospect of the destruction of the old geopolitical order at the hands of Rome. The story also highlights popular antipathy for kings. The match pitted a reigning champion named Kleitomachos against a challenger, Aristomachos, whom Ptolemy VI had trained for the occasion. Hungry for an upset, the Olympic crowd began by cheering on the underdog Aristomachos. Polybius describes Kleitomachos on his heels, nearly vanquished, pleading with the crowd, “Did they think he himself was not fighting fairly, or were they not aware that Kleitomachos was now fighting for the glory of the Greeks and Aristomachos for that of King Ptolemy? Would they prefer to see an Egyptian conquer the Greeks and win the Olympic crown, or to hear a Theban and Boeotian proclaimed by the herald as victor in the men’s boxing match?”Footnote 40 In an instant, the two competitors, confirmed Hellenes insofar as they had managed to enter an Olympic boxing ring, assumed different, oppositional ethnic identities. The speech ignited the crowd, which carried the Boeotian champion to victory over his Egyptian challenger. The incident does more than simply demonstrate the celerity with which a mob can descend into the humiliation of a perceived outsider; it also captures a specific, popular notion of Hellenicity at a critical juncture in the political history of the ancient Mediterranean. After a century and a half of increased migration and the forging of polyglot monarchies on the eastern lands of Alexander’s conquests, the claims of the community of origin were as strong as ever. The determinant criteria for belonging to the community of Hellenes, at least the one conjured up during the Olympic bout, were backward-looking: identification with an ancestral polis, an ethnos, and a particular place in Old Greece. Idle curiosity did not bring us the methodologically rigorous antiquarianism of Polemon, but rather popular prejudice about the distinctiveness of a homeland. Polemon’s agenda is thus entirely Attalid in that these self-proclaimed stewards of the Greek cultural heritage evince an acute interest in topographic authenticity.

They shared that interest with another second-century intellectual, the historian Demetrios of Skepsis in the Troad. He has been imagined as an “independent country squire,” for Diogenes Laertes calls him a wealthy and noble man, who also may have had access to a first-rate local library – Neleos of Skepsis was purported to have once been in possession of Aristotle’s books.Footnote 41 Unsurprisingly, Demetrios seems to have taken pride in his native city and participated in its rivalry with nearby Ilion for pride of place in Homeric lore.Footnote 42 Yet his ancient reputation implies a broader stature both in the Attalid kingdom and in the world of letters. He practiced textual criticism of Homer and topographic exegesis. He delighted in distinguishing spatial homonyms and, like Polemon, could boast of autopsy, pointing to the very hill on which the Judgment of Paris took place. In fact, Strabo, delving into the hydronymy of Mount Ida, urges his reader to trust Demetrios, a local person with experience of the terrain.Footnote 43 The geographer made great use of the scholar, whom Diogenes Laertes also praises as an excellent philologos.Footnote 44 Just as Demetrios’ fragments bear witness to an awareness of Attalid affairs and high politics, it can confidently be assumed that his ideas circulated in the emerging Library of the capital, even if he worked from home.Footnote 45 Moreover, his creation, the Trojan Catalogue (Τρωικὸς διάκοσμος), a mammoth commentary of 30 books on the 62-line description of Troy’s federative army (Iliad 2.816–77), Anatolian history as much as local, provided the Attalids – true Trojans on his reckoning – with a model for their pan-Asian empire.

Demetrios’ sprawling study was an attempt to organize the populations and lands of the Anatolian peninsula into a coherent whole. His description of his work as a diakosmos (ordering) implies as much.Footnote 46 On the one hand, his interests were restricted to the substance of the Homeric account, the subject of the exegesis. On the other hand, one senses that Homer’s lines were felt to be an inadequate ethnography of contemporary Anatolia. Demetrios needed to account for entire peoples and regions, features of his world that seemed to be sorely missing from the poem. A further mystery was the origin of the toponym Asia itself, which Demetrios located squarely within Attalid territory, in Maeonia-Lydia.Footnote 47 To the bedeviling problem of where to draw the line between Trojans and non-Trojan allies, Demetrios offered an intriguing solution. Modern Homeric philology tends to posit a single Trojan contingent, made up of bands of warriors native to the various cities of the Troad, coupled with five allied contingents from distinct geographical zones. These were the likes of Hektor’s Trojans and Aeneas’ Dardanians, in other words, the true Trojans. Demetrios, by contrast, seems to have divided the Trojan core, at least, into nine so-called dynasties. Where did Pergamon fit in? Interestingly, whereas the future site of the city and indeed the entire Homeric Mysia, on the basis of the primary text of Homer’s epic alone, can be assigned to allied units, in Demetrios’ exegesis, the Kaikos Valley and its Telephid rulers belong to the Trojan core. His Trojans ruled “up to the Kaikos.”Footnote 48 Yet adding the Attalids’ ancestors to Priam’s kingdom was clearly a stretch. Strabo even seems to waver in his endorsement of Demetrios’ schema, uncertain of the existence of the ninth dynasty, which belonged to Eurypylos son of Telephos, lord of the Kaikos. In an earlier part of the epic cycle, Achilles and company had mistaken Telephos’ Teuthrania for Troy. Was it Troy after all? Pergamon was indeed an alternate name for Priam’s citadel. Strabo’s hesitation may also have stemmed from the fact that among the nine dynastic captains, only Eurypylos arrived at Troy after the events described in the Iliad. The Odyssey knows of the event, but a scholiast states that Priam was obliged to convince Eurypylos to enter the war as the allied king of Mysia.Footnote 49

A centuries-old tradition had linked the houses of Telephos and Priam: the mother of Eurypylos was Astyoche, a Trojan princess, and Andromache bore Pergamos, the eponymous founder of the city. The Attalids have been justly accused of constructing mythological links to the winning side of the war as well. In a grotesque twist, Neoptolemos fathered Pergamos, and the position of the stoa of Attalos I at Delphi seems to have stressed the Aeacid connection.Footnote 50 Equally ancient must have been the tradition of Telephos’ Arkadian origins, which provided the Attalids with a prestigious link to Herakles (and Alexander). What is new in the work of Demetrios of Skepsis is the identification of the Attalids’ forefathers as primeval Trojans. This anchored the dynasty to the rest of Anatolia – not just the Kaikos Valley.Footnote 51 The Attalids now gained access to the deep, pan-Anatolian past to which Demetrios was determined to award cultural primacy. Many mountains were called Ida, but it was the one in the Troad, he argued, on which Zeus had been born. It was a daring argument, mounted against the authority of fifth-century Athenian tragedy. What was the proof? Demetrios took a characteristically empiricist tack, declaring that the rites of Rhea (Cybele) were indigenous to the Troad and Phrygia alone. Any claim to the contrary was mythology, he declared, not history.Footnote 52

So much had changed since Trojans in Phrygian dress had graced the tragic stages and red-figure pots of Athens. As is well known, Homer depicts a war between Achaeans and Trojans, not Greeks and barbarians. Those categories had yet to be developed. It took the events of the Persian Wars to initiate a change in self-perception that recast the Trojans in the role of eastern, in the case of Paris, specifically Phrygian barbarians.Footnote 53 Inevitably, the idealized civilization of Priam’s kingdom militated against any such downgrade. It has even proven possible to regard the Ilioupersis (Sack of Troy) depicted on the northern metopes of the Parthenon as a cautionary tale in hubris for imperial Athens.Footnote 54 However, it is difficult to deny that the fifth-century Athenians inflated their participation in the mythological war of the epic cycle to match their leading role in recent history’s clash with Persia. The conflation of Troy with Persia followed suit. In the agora, the iconographic program of the Painted Stoa was the first to juxtapose the Battle of Marathon with Ilioupersis. Later, on the Periklean acropolis, in addition to the Parthenon metopes, one can point to a colossal bronze “Trojan Horse” set up in the sanctuary of Artemis Brauronia, stocked with local, Athenian heroes. If in this montage, the acropolis of Athens came to stand in for the citadel of Troy, this was of a piece with Athenian attempts to claim their own primacy in the Troad by rescripting the Aeolian and Ionian migrations.Footnote 55 In other words, not only were the Trojans barbarians, by this account, but their occupation of Ilion was illegitimate.

As we have seen, the conception of Demetrios of Skepsis was entirely different. It served Hellenistic Pergamon’s imperial needs, not those of classical Athens. In Demetrios’ conception, Trojans claimed primacy in the Troad, and Pergamenes were counted among their ranks. Ties of kinship bound them to Phrygians, construed as a population of primordial Anatolians. Demetrios’ work brings into focus the multifaceted character of the Trojan connection in Attalid cultural politics, which represented far more than a means of currying favor with the Romans.Footnote 56 Indeed, Ilion was the fulcrum by which the Attalids made themselves kinsmen of the descendants of Aeneas. In 205, we find Ilion and Pergamon set side by side as signatories to the Roman-brokered Treaty of Phoinike. The dynasty’s benefactions at Ilion and other interests in the Troad are well documented.Footnote 57 Yet at the very same time, Attalos I effected the transfer of the cult of Idaean Cybele to Rome from a seat in Pessinous, the ancient Phrygian cult center. Gruen has written of the way in which the Trojan lineage allowed the Romans to acquire a character “distinct from that of the Greeks but solidly within the Greek construct.”Footnote 58 In an analogous fashion, the same lineage gave the Attalids a purchase on a distinct, Anatolian identity, now firmly embedded in the Homeric matrix. Troy was a bridge to Rome, but also to Pessinous.

The Attalids’ stake in the glory of Troy was then of critical importance to their imperial project and no mere window dressing. It may be that a hint of their Trojan affinity is admitted by the historical narrative presented on the Athenian acropolis in the form of the dedication known as the Little Barbarians. In the reconstruction of Andrew Stewart, the Attalid monument presented a universal history, unfolding from the beginning to the present, a series of challenges to the civilizational order: Giants, Amazons, Persians, and, finally, Galatians. The Attalids could rely on a local tradition of assimilating the enemy of the hour to the Persian barbarian, as well as a Panhellenic one that likened the Galatian bands to Xerxes’ army.Footnote 59 For Stewart, the dedication “created a Pergamene-Periklean alliance across time and space to defeat the entire gamut of civilization’s foes.”Footnote 60 Yet the Trojans were conspicuously absent from the rogues’ gallery. By contrast, the Periklean prototype, as represented by the Parthenon metopes and the Stoa Poikile, included an Ilioupersis. The sack of Troy was later represented on highly visible temples such as the Argive Heraion and the temple of Asklepios at Epidauros, and the iconography reemerged in the Troad itself at Ilion and Chrysa.Footnote 61 The Attalids seem to have taken part in the construction of the new Athenaion at Ilion, which, ironically or not, featured an Ilioupersis on its metopes with Trojans in eastern garb.Footnote 62 We have no way of knowing what, if any, role Pergamene artisans or patrons had in the selection of the theme for the Athenaion. Its appearance, unusual in the Hellenistic period, must be related to the special relationship of the Troad to the Homeric past, especially at a time when Iliadic tourism was booming. On the other hand, we know that the Attalids did not evoke a Trojan theme among their dedications on the Athenian acropolis. This may have been because they saw themselves as the successors of Priam, as civilized a king as any who had ever lived.

The Attalid Way of Death

Faced as they were with the task of ruling a vast and diverse Anatolian territory, the Attalids’ choice to play the part of Priam’s heirs makes perfect sense. Like Priam’s rule, they could argue, theirs too was just and rightful. Likening their empire to the Trojans’ alliance, moreover, would have promoted an ideology of consent and cast a shadow over coercive measures. In the archaeological record, one can detect an allusion to the glory of the heroes of Troy in the form of a series of burial mounds (tumuli) scattered around the periphery of the city of Pergamon. Most of the tumuli of Pergamon are Hellenistic, built in the third and second centuries BCE.Footnote 63 In fact, adjacent to the city’s gate, the early second-century fortification wall of Eumenes II sliced through a third-century tumulus encasing a chamber tomb, effectively incorporating it into the bulwark. Since Archaic times, the names – and cults – of Homeric heroes had been associated with particular hilltops, natural and man-made. On his way through the Troad, Alexander had visited a certain mound then known as the tomb of Achilles.Footnote 64 Under the Attalids, the citizens of Ilion undertook a major public works project at the site now known to archaeologists as the Neolithic settlement of Sivritepe. They artificially increased the height of the mound, from 5 to 13 m, an intervention that was sure to capture the imagination of would-be pilgrims. The site was soon roundly recognized as the Tumulus of Achilles.Footnote 65 Now, at just this moment, members of the ruling clique of Pergamon were burying themselves in tumuli. Surely, one impression conveyed by the choice of tomb type was the desire to assert Trojan filiation. Were the tombs, then, just one more baldly transparent effort to invent tradition? Quite the opposite: the tumuli fit into a well-documented Anatolian tradition, which informs us about the Attalids’ cultural identity and helps explain their success.

With just a glance over the tumulus field at Pergamon, one notices both considerable diversity in mortuary practice, but also the unique grandeur of the Yığma Tepe tomb (Fig. 6.1) Given their number, differences in size and in the nature of the excavated grave goods, it must have been the case that kings and nonroyal elites alike shared this burial custom. The smaller tumuli, such as Tumuli 2 and 3, have a diameter of ca. 30 m and are braced by a low stone wall called a krepis. Both lack a burial chamber and contain only an andesite sarcophagus buried below ground level. Grave goods from Tumulus 3 are modest compared with those of Tumulus 2, which include a golden oak-leaf wreath. Another significant example is the tumulus on the saddle of the Ilyas Tepe, facing the east side of the acropolis. It is also just 37 m in diameter (5 m tall), but it contains a dromos (entry corridor) and an elaborate, Macedonian-style chamber tomb covered with a barrel vault. Yet the subterranean burial in a stone sarcophagus recalls the rite practiced by the builders of Tumuli 2 and 3.Footnote 66 The occupant of the tomb is thought to be an important general of the third-century reign of Attalos I. None, though, matches the grandeur of Yığma Tepe, which is 158 m across, 35 m tall, and surrounded by a deep ditch, the very source of its material, a cavity that enhances the visual impact of the mound. Despite several attempts to find it by digging and with geophysical prospection, a burial chamber has never been located, but a monumental krepis, without an entrance, has been exposed. New excavations have uncovered thin rows of stones above and perpendicular to it, which may be late additions to the monument. Ceramic finds from the excavations of the early twentieth century, taken together with the style of the masonry, offer a provisional date in the second BCE. An important clue for the identification of the occupant of the tomb is the orientation of the Yığma Tepe along an axis that joins both the west side of the Temple of Athena and the stairway of the Great Altar, over 3 km away. The city-builders Eumenes II or Attalos II are therefore the most likely candidates. Given its unique size and suggestive spatial context, the fact that we await the hard proof need not deter us from an analysis of the tumulus as a royal burial monument.Footnote 67

Figure 6.1 Yığma Tepe.

Comparison of the Attalid tumulus tradition with the burial customs of the major Hellenistic dynasties is instructive. The Ptolemies, we know, were interred and displayed alongside the body of Alexander inside a mausoleum known as the Sema or Soma. That building lay within the segregated royal quarter of the city of Alexandria, attached to a complex that also included the Library and the Museum. The monument housed Alexander’s cult as well as the dynasty’s. With this novelty, the Ptolemies clearly broke with pharaonic precedents, but in good Egyptian fashion, they had themselves mummified.Footnote 68 While aided by archaeology, our picture of the Seleukid practice is in fact less complete. We know that Antiochos I built a sacred precinct for the remains of his father Seleukos I, known as the Nikatoreion, set within the palace district of Seleukeia Pieria. The precinct contained a large, non-standard Doric temple that covered a crypt, in which, it has been conjectured, Seleukos I’s descendants joined him in death. This combination of precinct, temple, and, therefore, posthumous ruler cult, all housed within a palace district, was repeated in breakaway Bactria at Ai Khanoum. It seems to represent the Seleukid way of death.Footnote 69 In the case of the Antigonids of Macedon, direct testimony is lacking. However, it seems very likely that they were buried in tumuli. Certainly, several of their Temenid predecessors were buried in chamber tombs under the Great Tumulus of the royal necropolis, which was not attached to the palace, but lay on the outskirts of Vergina/Aigai. Though the necropolis of Pergamon has not (yet) produced the exposed architectural facades of the conventional Macedonian tomb, shared features include the barrel vault on Ilyas Tepe, the common krepis, and the wreath of Tumulus 2.Footnote 70 The fundamental point of similarity between Pergamon and Macedonia is a consistent if not continuous tradition of tumulus building, which the powerful, almost by default, make their own. In Macedonia, we can trace it from the Iron Age mounds at Vergina to the proliferation of large (50–100 m wide) tumuli at Hellenistic Pella.Footnote 71

Tempting as it is to interpret the Pergamene tumuli as little more than a claim to Macedonian identity, shoring up the link to Alexander that was tenuous at best, we risk overstating the importance of a single point of reference among many. Moreover, by positing diffusion from Macedon, we mistake correlation for causation.Footnote 72 It is important to understand that in this respect, the Macedonians themselves were just one party to a heritage from prehistoric southeastern Europe. The neighboring Thracians were another, and as they moved from the central Balkans eastward, the practice spread into the region of modern Kırklareli in the Thracian Chersonnese.Footnote 73 With another Iron Age migration, that of the population that came to be known as the Phrygians, the tomb type appeared around Gordion.Footnote 74 To try to pick apart the issue of influence hundreds of years later is next to impossible, though Barbara Schmidt-Dounas has suggested that it was, in fact, Anatolia that influenced the growth in the size of the later tumuli of Macedonia.Footnote 75 In short, for an Attalid subject, a tumulus did not read as Macedonian. In Anatolia itself, an impressive number of models for the Yığma Tepe were available. The landscape was saturated with tumuli – from the fuzzy eastern border inland to the boundaries of the coastal city-states. They flanked the capitals of earlier Anatolian empires such as royal Phrygia and Lydia, and had more recently become a defining feature of the Granikos Valley in the Troad. Because these are highly durable monuments, an ancient viewer saw an accretion of tumuli from different periods. Their dates of construction, only a minority of which have been established by modern excavation, were hardly discernible in antiquity. Yet significantly, a chronological synopsis of the tumulus tradition in Anatolia demonstrates continuity of practice. It also provides a broader context for interpretation.

The earliest point of reference for the Yığma Tepe is indeed the tumulus field at Gordion, capital of Iron Age Phrygia, filled with some 240 examples.Footnote 76 The Phrygians began building them in the ninth century BCE and increased their size and the richness of their contents in the eighth. If the number of such tombs seems to diminish in the sixth century BCE, Hellenistic examples have also been recorded at Gordion.Footnote 77 Now dated ca. 740 BCE, the most monumental of all is Tumulus MM, a royal burial consisting of a wooden chamber covered by a tumulus 53 m high and 300 m in diameter. In the second century BCE, it lay in a part of Galatia that bordered Attalid territory, but one can also find Phrygian tumuli in areas directly under Pergamene control. For example, in the late eighth or early seventh century BCE, Phrygians had built a spectacular series of tumuli far from Gordion, on the piedmont above the plain of Elmalı (Bayındır), in the southern Milyas.Footnote 78 Similarly, in western Phrygia, a recent survey identified 65 tumuli, most of which cannot be dated without excavation. The painted Taşlık tumulus exhibits Phrygo-Lydian architecture, but may date to the Achaemenid period, as does the painted tomb at Tatarlı. On the other hand, the find-rich Kocakızlar Tumulus, 80 m in diameter and erected in open country 3 km from the site of Midaion, is Hellenistic.Footnote 79 After the collapse of the Phrygian state, Lydian royals and elites adapted the practice to their own architectural traditions in the second quarter of the sixth century BCE.Footnote 80 Certain Lydian tumuli possess a krepis. Ten kilometers from Sardis is a field known today as the Bin Tepe (“thousand hills”); around 100 tumuli have been identified at Bin Tepe, and 500 in greater Lydia. Of these 600, only 54 have been dated to within a century. While several of the largest and most prominent, such as Kocamutaf Tepe, associated with king Alyattes, date to the period of Mermnad rule, the tumulus tradition is best represented in Lydia during the first century of the Achaemenid period.Footnote 81 At the same time, tumuli of the Lydian style appeared at Delpınar in Persian-controlled Pisdia.Footnote 82 The Achaemenid period also witnessed the proliferation of tumuli in Troad’s Granikos Valley, such as the one at Kızöldün, dated ca. 500–490 BCE, the source of the Polyxena sarcophagus. These seem to belong to a mixed milieu of Anatolian, Greek, and Persian estate-holders. Once they were dispossessed of their lands, these sites were largely abandoned.Footnote 83

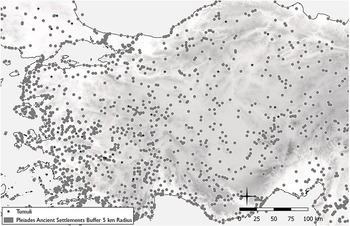

Clearly, dramatic shifts in the historical center of power affected the distribution of tumuli. A succession of empires left their mark on the landscape. The Attalids, it seems, as heirs to one of the petty fiefs of the Persian period, picked up where the likes of the Gongylids left off. Yet high political history hardly explains the ubiquity, durability, and historical continuity of the phenomenon. Salvage archaeology in contemporary Turkey, driven by the twin threats of economic development and looting, provides a reasonably random sample. The last 26 years of accidental discoveries has produced 43 excavated tumuli. Chronologically, they run the gamut from Iron Age to Late Roman. Significantly, 18, or 42%, have been dated to the Hellenistic period. Their spatial distribution is very broad, with a clustering in the upper Maeander and Lykos river valleys, which Ute Kelp has related to Attalid influence and even a possible refoundation of Hierapolis.Footnote 84 Another discernible pattern is that the tumuli seldom lie within a 5-km radius of recorded settlements (Map 6.1). Whether they belong to rural estate holders or to rulers residing in nearby towns and cities, the tumuli do seem to promote claims of land possession.Footnote 85 In political terms, they also present the face of power to wayfarers traversing a demarcated territory.

Map 6.1 Tumuli recorded in salvage excavations (Müze Çalışmaları ve Kurtarma Kazıları Sempozyumu Yayınları, 1990–2016) and ancient settlements in the Pleiades data set (pleiades.stoa.org).

From the Aegean to the Euphrates, a dense scatter of tumuli emerged over the course of the first millenium BCE. Ultimately, Pergamon’s tumuli belong to what can be termed an Anatolian koinê of burial practices.Footnote 86 In burial, the Attalids behaved precisely as their regional rivals did. The salvage results proffer a more or less approximate idea of the likely appearance of royal or princely Bithynian, Galatian, and indeed Pontic tumuli. At Üçtepeler, for example, near Bithynian Izmit (Nicomedia), excavations have revealed a late Hellenistic tumulus 75 m across and 12 m high, containing a vaulted burial chamber and a dromos – a strong candidate for a Bithynian royal tomb.Footnote 87 Philetairos’ native Paphlagonia recently produced a roughly contemporaneous tumulus with a painted burial chamber, at Selmanlar.Footnote 88 It is now well understood that the Galatians abandoned La Tène burial practice for the Anatolian tumulus.Footnote 89 At Karalar (Blucium), an inscription identifies the tomb’s occupant as Deiotarus the Younger. Galatian tumuli have also been investigated outside Gordion and at Yalacık, near Ankara.Footnote 90 The Mithridatids are a fascinating case because they vacillated between Greek, Persian, and Anatolian traditions. Down to ca. 180 BCE, the kings of Pontos were laid to rest in the rock-cut tombs of the royal necropolis of Amaseia. With the transfer of the capital to Sinope under Pharnakes I, a change occurs, and it has been conjectured that later kings, including Mithridates VI, were buried in tumuli.Footnote 91 The results of the excavation of a Hellenistic tumulus at Arafat Tepesi, 50 km from Çorum, as well as data from an intensive survey of the hinterland of Sinope, render the idea quite plausible.Footnote 92 The spectacular monuments of Orontid Commagene also belong in our reckoning, but so too those of Cappadocia. While no Ariarathid royal burial is securely identified, the stone tumulus at Avanos in Nevşehir province is a candidate, while salvage excavations have dated two more Cappadocian mounds to the Hellenistic period.Footnote 93

To be fair, this sample contains a great variety of technical features of construction, size, and placement in the landscape. The tumulus is also an enormous expenditure of wealth, and ostentatious consumption always had a local history and a distinctive role in social structure.Footnote 94 Yet what seems to justify analysis on this scale is Pergamon’s own Pan-Asian political claims – enunciated in the Telmessos decree of 184/3. In death, how did the powerful comport themselves within the political space delineated for “the inhabitants of Asia”? Further, the bird’s-eye view makes plain the stark difference between, on the one hand, Asia (Minor), as construed as the coastal Aegean zone conjoined with inner Anatolia, and, on the other, mainland Greece and the islands. Archaic and Classical Greece witnessed a boom-and-bust cycle of ostentation in burial, the record of which includes tumuli among other forms such as peribolos monuments. Broadly speaking, the fifth century seems to have witnessed restraint in the form of burial. Restraint seems to end, at least in Athens, already during the Peloponnesian War. A new cycle of ostentation began that petered out toward the end of the fourth century. The disappearance of monumental tombs like tumuli from the landscape of Greece is often tenuously attributed to sumptuary laws, though it surely also must reflect the redirection of disposable income toward other ends, such as house-building and public works.Footnote 95 A sharp decline in the number of tumuli can be discerned already ca. 600 BCE.Footnote 96 They disappear from the Kerameikos at Athens and also from the great tumulus fields of Thessaly at Krannon and Pharsalos.Footnote 97 Of course, there are some outliers such as the Macedonian-style Tomb of the Erotes at Eretria, but by and large, the tumulus is not a feature of the landscape in Hellenistic Greece. This contrasts markedly with the situation in East Greece. So what? Here, the tumulus tradition appears to be unbroken. From the archaic period, for instance, comes the sixth-century tumulus at Belevi near Ephesus, as well as the archaic tumuli of Larisa-on-the-Hermos.Footnote 98 Scores have also been detected in surveys of the Ionian cities Klazomenai and Teos.Footnote 99 Classical tumuli are known from the territory of Parion.Footnote 100 A recent salvage excavation investigated the Biçerova tumulus, a fifth-century tomb 2.5 km from Kyme.Footnote 101 Hellenistic examples from Pergamon’s immediate regional context are not lacking. In the second century, at the modern site of Maltepe near ancient Phokaia, a tumulus was founded on the archaic city wall in the second century.Footnote 102 Near the port of Elaia, the Seç Tepe tumulus was also in use at this time.Footnote 103 In Anatolia, Greeks were not outsiders, socially distanced from the rest – though the modern discipline of Classics has often portrayed them this way. A possible royal tomb at Yığma Tepe, therefore, aligns the Attalids not only with Anatolian kings of an earlier age but with the Graeco-Anatolian aristocracy of many neighboring cities.

City as Acropolis

With the conquest and acquisition by award of new territories, as well as a westward push to seize Aegean islands and gain ever more influence at Rome, it is a curious fact that the Attalids never moved their capital, but retained and embellished a mountain redoubt. As the landscape archaeologist Christina Williamson has shown, that mountainous viewshed makes of the lower Kaikos Valley an inward-looking, landed microregion. Indeed, standing atop the peak of Pergamon (329 m asl), the best line of sight points east and inland, up the Kaikos Valley toward modern Kınık and Soma. By contrast, it is only on a very clear day that the sea and the port city of Elaia are visible (Fig. 6.2).Footnote 104 With respect to the urbanism of their capital, then, the Attalids made a distinctive, even suprising choice. In Macedonia of the early fifth century, Archelaus had moved the Argead capital down from Aigai to the coastal estuary at Pella. In time, the polis of Pella was refounded on the so-called Hippodameian grid and appended to a royal residence. While the Ptolemies and the Seleukids both inherited the seats of ancient empires, they chose to stake out new cities according to Greek conventions of space. Further, Alexandria and the Syrian Tetrapolis both hugged the Mediterranean. Even contemporary Anatolian rivals did things differently. Mithridates I shifted his capital from inland Amaseia to the polis of Sinope on the Black Sea; the Bithynian Prousias I refounded Kios as Prousa-on-the-sea.Footnote 105 Logistically, the Attalids certainly could have decamped to Ephesus and ruled from a city that had hosted Antigonids, Ptolemies, and Seleukids. In fact, in recent excavations conducted above the city’s theater (Panayırdağ), a lavish peristyle house on the scale of the Attalids’ Palast V (2,400 m2) has been revealed. The excavator has dated the building to the second century and noted many Pergamene architectural features, suggesting an Attalid governor’s residence, perhaps even a secondary palace.Footnote 106 Yet their capital remained what had been an important sub-satrapal stronghold of the late Persian period, which, as the military history reminds us, retained its defensive value. Less obvious, perhaps, is the ideological value of presenting this vertiginous and asymmetrical urban facade to would-be subjects.

Figure 6.2 View to the southwest of the Kaikos Valley from the acropolis of Pergamon.

Standard accounts of the monumentalization of the Pergamene acropolis underscore the builders’ reverence for Classical Athens.Footnote 107 It was not Philetairos, in fact, but one of his immediate predecessors, Barsine or Lysimachus, who seems to have replaced the cult of Apollo with that of Athena Polias as the central cult of the city. Yet the late fourth-century construction of the sanctuary and temple of Athena Polias, along with the introduction of the Panathenaia festival by the time of Eumenes I, it has been argued, speak to a wider effort to liken Pergamon, supposedly lacking traditions of its own, to storied Athens.Footnote 108 For Schalles, the equation of the two cities in Attalid self-presentation is assured by the time of Attalos I, who reorganized Athena’s terrace.Footnote 109 However, if we zoom out from the sanctuary and consider the cityscape as a whole, the equation breaks down. Athens is a democratic city with an acropolis (Fig. 6.3); Pergamon represents an altogether different, Anatolian, and oligarchic model of urbanism, in which the city is an acropolis (Fig. 6.4).Footnote 110 Astoundingly, the excavated residential quarter (Wohnstadt) is laid out on a slope of about 20–25%, a fine point of comparison to the core of Lydian Sardis, which registers at 16–20%.Footnote 111 As once described by an excavator of Sardis, Pergamon is “a typical Anatolian acropolis town,” built on the spur of a mountain, just like the Lydian royal capital.Footnote 112 Many Lycian cities also seem to cascade down steep hillsides, a type of urbanism that is widely recognized as pre-Greek and indigenous. For example, at Xanthos, major changes in elevation (in sum, over 50 m) separate the city’s various districts. Some 25 m above the lower city stands the palace and dynastic monuments of the so-called Lycian acropolis; at about the same elevation is the public space of the presumed Lycian agora. Another 25 m up the hill, one reaches the citadel of Xanthos, conventionally known as the Roman acropolis, but exhibiting Classical-period remains.Footnote 113

Figure 6.3 Model of ancient Athens.

Moreover, it was not only the siting of the city that evoked Anatolian precedents, but planners’ treatment of the mountainous terrain. To a far greater extent than the prototypical Greek polis, Pergamon was “sculpted” out of towering volcanic rock.Footnote 114 As has long been noted by archaologists, the landscaping of Pergamon’s peak into its several iconic, monumental terraces, a process accelerated if not completed by Eumenes II, finds a close parallel in Sardis.Footnote 115 In the center of the Lydian city (“Acropolis North”), the revetment of the natural spurs of the mountain also created a series of terraces linked together by handsome staircases. Excavation has exposed the Lydian revetment, which consists of the kind of fine ashlar masonry found in royal tombs.Footnote 116 These ashlar terrrace walls were, in a sense, the face of the Lydian royal capital. The best understood of the terraces lie in Sardis sectors Field 49 and ByzFort. The latter is estimated to have enclosed an area of 1.2 ha. While visible from afar, these sculpted bluffs also stand apart from the lower city and its more expansive residential quarters. Yet their connection to the highest point of the acropolis seems assured. A tunnel cut in the bedrock in the valley between ByzFort and Field 49 leads the way. In essence, this regional technique of boldly terracing the mountainside creates dramatic vistas by taking advantage of natural contours. It does not seek to regularize the terrain or organize it modularly. As Nicholas Cahill puts it, “The Lydians, however, treated their sloping ground very differently from the later Greeks.”Footnote 117 Then, when, in the early Hellenistc period, the Sardians finally returned to this area, perhaps already or soon to become denizens of a polis, they recreated the spatial aesthetic of the Lydian period. Current excavations in Field 49 show a remarkable investment in stabilizing and raising the level of the hill with massive subterranean foundations that follow the Lydians’ alignments (Fig. 6.5).Footnote 118 In Sardis as in Pergamon, the geometry of Priene’s fourth-century grid is nowhere to be found, but alongside the grandeur of the untreated rock, it is the sculpted earth and the terrace wall that stand as monuments and showpieces in their own right. It has proven difficult to find a precedent for the urban plan of Lydian Sardis in Anatolia, prompting considerations of Near Eastern influence.Footnote 119 On the other hand, the local vassals of the intervening Achaemenid period offered the Attalids a blueprint for a high-elevation capital.

Figure 6.5 Archaic terrace walls of Sardis, reconstruction drawing by Philip Stinson.

First, Lycian dynasts were well accustomed to residence in cities built on precipitous slopes that descended from a fortified peak, often containing a necropolis. Just as in Xanthos, we often find important monuments on a level terrace, which is usually not the highest point, but again, set on a spur lower down the mountain. In Xanthos, this is the Lycian acropolis, with its dynastic heroa, palaces, and public buildings. Elsewhere in the same river valley, one finds the same pattern at Tlos and also at Pinara. It is telling that at Pinara the large (ca. 1.7 ha) basileia terrace was once referred to as the “lower acropolis.”Footnote 120 In the east of Lycia, the city of Arykanda controls a steep pass into the plain of Elmalı. The earliest remains show it to have been a minor dynastic center, but one which conforms neatly to the pattern of a lofty fortified acropolis, set high above a city that itself clings to the sides of a mountain. The city grew in importance in the Hellenistic period, and, in fact, it seems that Arykanda received its stunning terraces at about the same time that Pergamon’s were completed (Fig. 6.6).Footnote 121 Second, the Hekatomnids of Caria had provided the Attalids with an obvious model in Halikarnassos, the capital of Mausolus, as well in other cities such as Amyzon. The Hekatomnid influence on Attalid urbanism is glimpsed through Pergamon’s participation in the fourth-century BCE Ionian Renaissance, a cultural program that effectively restored parity between western Anatolia and mainland Greece.Footnote 122 Indeed, the Hekatomnid inheritance is also detectable in many other ways, for example, in the mythological gamesmanship that gave both royal houses an Arkadian pedigree and links to Herakles. Yet as a builder, specifically, Mausolus propagated the technique of using terrain and terrace to give a royal city an iconic facade. His two grand terraces dominated the cityscape of Halikarnassos, one belonging to the Temple of Mars, while the other, twice as large and visible from the island of Kos, supported the Mausolleion.Footnote 123 Another Hekatomnid terracing project has been identified at the sanctuary of Artemis in Amyzon, girding a spur of Mount Latmos. Two terraces joined at an angle form a line 168 m long, comparable to the 160 m of the upper terrace of Pergamon’s theater. However, the visual effect of the rusticated terrace walls at Amyzon is to minimize the impact of the buildings themselves – the propylon, and even the temple.Footnote 124 In this architectural idiom, platform is as significant as superstructure. One can hardly say the same of Classical Athens, the Propylaia, the Parthenon, and the Acropolis.

Figure 6.6 Late Hellenistic terraces at Arykanda.

Gallograeci

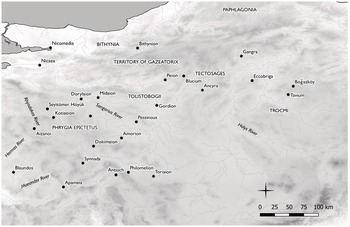

Around 281, a large, migratory movement of Celtic-speaking peoples arrived in the Balkans. Under their leader Brennos, they fought through Macedonian territory and threatened to sack Delphi, where Antigonos Gonatas and a coalition of Greeks featuring Aetolian and Athenian contingents stopped the Celtic advance. Reversing course, two offshoots of the original migration, one under Leonnorios and another under Luturios, set off for Anatolia. With their passage across the Hellespont, in 279/8, they came to be known as the Galatians – the Celts of Anatolia. Bands of Galatian warriors, sometimes serving as mercenaries in the armies of Bithynian, Attalid, and Pontic kings, at other times operating as unattached raiding parties, fought in the nude behind the long, oval shields distinctive of Europe’s La Tène tradition. Torques around their necks, their hair dressed with lime, Asia’s newest barbarians struck fear into the hearts of the city-dwellers of the coast. Down into the 260s, “Galatian war” (πολεμὸς Γαλατικός) was a common experience and a “Galatian fund” (τὰ Γαλατικά) a possible line item in city budgets. Ultimately, most – but not all – of the migrants settled in the central highlands, what had once been the upland core of the Phrygian and Hittite empires.Footnote 125 By then, they had formed three separate tribes. Each group claimed its own loosely defined territory around a regional emporium: the Tolistobogii in the west, holding Gordion; the Trocmi in the east, around Tavium, in the bend of the Halys; and the Tectosages in between, occupying Ancyra. We know that the Celts did not find these lands empty, and archaeology continues to reveal a subtle process of accommodation to preexisting conditions and culture. Beyond convening a pantribal council to try homicide cases once per year, the Galatians seem rarely if ever to have acted as a unified bloc in politics or war. Nevertheless, a capable set of adversaries confronted the Attalids on their eastern flank. As many have pointed out, the Galatians also presented Pergamon with an opportunity to garner much-needed legitimacy. The Attalids needed the Galatians.

This was certainly the case for Attalos I. He was the first king of Pergamon, the first of the dynasty to take the title of basileus and wear the diadem, and indeed the Hellenistic ruler who squeezed the most out of his triumphs over Galatians. Polybius’ eulogy for Attalos reads, “For having conquered the Gauls, the most formidable and warlike nation of Asia, he built upon this foundation, and then first showed he was really a king.”Footnote 126 This account of the birth of the Attalid kingdom as such in the years after 241 is very partial, but also very telling. It occludes the broader context of a breakdown of Seleukid authority beyond the Taurus and perhaps also Pergamon’s enduring vassalage, but it grounds the Attalid kingship in the memory of specific, historical victories over the Galatians girded with myth. This is most evident in several large dedications in the Sanctuary of Athena at Pergamon, which Attalos now remodeled, using free-standing sculpture to depict, it seems, multiple battle scenes featuring Seleukid and Galatian enemies, while the dismembered La Tène-style arms appeared as trophies on the surrounding architecture.Footnote 127 The connection between the Attalid claim to kingship and the Galatian triumphs recorded in Athena’s sanctuary appears so tight that scholars have long dated an alteration to the portrait head known as the Berlin Attalos, an update which may have added its diadem, to a moment not long after the “battle near the source of the Kaikos River against the Tolistoagioi Galatians” (OGIS 276).Footnote 128 Not only was this piece of local history soon internationalized when a team of high-profile Greek sculptors arrived to commemorate them in Pergamon, but Attalos also trumpeted the importance of his victory in the centers of Old Greece, Delos, Athens, and probably also at Delphi. In so doing, he joined other Hellenistic kings in a Panhellenic discourse that cast the Galatians as a barbaric threat to cosmic order. The Battle of the Kaikos has come to be seen by scholars as a kind of “Pergamene Marathon,” in a construct which allegorizes the Attalids as the Athenians and the Galatians as the Persians. On the mainland, that interpretation holds more weight, as Greeks do seem to have interpreted the defense of Delphi in 279 in those terms.Footnote 129 In Asia, by contrast, the nature of events meant that the Galatians’ crossing simply could not fit into the same mythico-historical tradition. Moreover, at home, the goal, as we have seen, was different: not only or even necessarily to burnish Hellenic credentials, but rather to normalize Attalid rule in Asia. For this reason, and because real-life Galatians inhabited the borderlands and surely some of the territory they already claimed, the Attalids’ rhetorical rendering and interactions with the Galatians were more complicated than is usually assumed.

Rhetorically, the fit between the Galatians and the Persians, as expressed, for example, in Hellenistic panegyric, was in fact rather awkward. What kind of barbarian was the Celt? The contemporary answer shades toward tropes of reckless ferocity, mindlessness, and bodily austerity. Barbaric traits, certainly, but hardly an established antithesis of all things Greek. One third-century elegiac poet goes so far as to contrast the effeminate Persian of his purple cloth and tents with the impetuous Galatian who camps in the open air.Footnote 130 The Persians of yore remained an important touchstone in political invective. Opponents could paint a Seleukid, even an Antigonid or Lysimachus as a new Xerxes.Footnote 131 However, the effectiveness of the Persians in a historical analogy drawn to make sense of the Galatians in Anatolia was limited by the fact that one barbarian menace had crossed from Asia and left; whereas the other had crossed into Asia and remained, an event that cried out for explanation. In response, Hellenistic historiography seems to have generated a novel set piece, the unwelcome Crossing of the Gauls, while debating culpability. In multiple source traditions, narratives were built around this critical event. For instance, a chapter heading of Pompeius Trogus reads, “How the Gauls Entered Asia (transierunt in Asiam) and Waged War with Antiochos and the Bithynians.”Footnote 132 In historical memory, the Gauls’ crossing to Asia merited its own treatment, distinct from other episodes. The epithet of that very Antiochos I, namely, Soter (Savior), is elsewhere attributed to his expulsion of the “Galatians who had invaded (esbalein) Asia from Europe.”Footnote 133 One of our earliest and best accounts, that of third-century Nymphis-Memnon of Herakleia Pontika, represents an apologetic perspective on the crossing. Amassed on the European side, the patriotic historian relates, the Gauls had long been harassing Byzantium, which his faithful Herakleia had supported with gold. Earlier, the Gauls had repeatedly attempted to cross, without success.Footnote 134 At last, on terms of an alliance with Herakleia and the other cities of the Northern League, it is stressed, Nicomedes I of Bithynia “transferred the Galatian population to Asia (τὸ Γαλατικὸν πλῆθος εἰς Ἀσίαν διαβιβάζει).” In a case of special pleading, Nymphis-Memnon contends that the inhabitants of Asia (oiketorês Asias) actually benefited from the arrival of the Galatians, who, he claims, supported democracies against kings. Clearly, the singular event of the migration of the Celts across the continental divide resisted assimilation to the Persian invasion. It also left a wound that stung so long as these newcomers menaced “the inhabitants of Asia.”

In short, the new northern barbarians threatened civilization in Asia, not Greece. Geographically, the concept of a Graeco-Macedonian mainland that was distinct from the continental notion of Asia had emerged in Alexander’s wake.Footnote 135 In the early third century, the painter of the Boscoreale Frescoes had personified the two as opposing female figures, inveterate enemies. Of course, in 279/8, many of those who incurred losses would have counted among them the assault on their dignity as Hellenes. This is precisely what the decree for Sotas from Ionian Priene reports: “It happened that many of the Greek inhabitants of Asia were ruined. They were not able to struggle with the Barbarians (πρὸς τοὺς βαρβάρους ἀνταγωνίζεσθαι).”Footnote 136 Yet the Attalids were not obliged to adopt the same stance – even in triumph. They could, for example, adopt the stance of the Lycians of Tlos. The epigram of Neoptolemos son of Kressos commemorates the defense of the city, perhaps during the initial wave of migration in the 270s and 260s: “I am Neoptolemos son of Kressos. In the Temple of the Three Brothers the citizens of Tlos set (me), glory of my spear. For them, so many Pisidians and [Paeonians] and Agrianians and Galatians I confronted and scattered away.”Footnote 137 For a Greek-speaking Lycian of the Hellenistic period, the Galatians were no more barbarous an enemy than the neighboring Pisidians. Similarly, when Eumenes II addressed the inhabitants of the town of Apollonioucharax in Lydia, with its local milieu of Mysians, the king described the Galatians straightforwardly as “enemies (polemioi).”Footnote 138

In Anatolia, there was nothing to gain by representing the Galatian as the non-Greek foil to the Hellene. Rather, advantage was to be had by entering the fight against the Galatians on the side of all of the inhabitants of Asia, irrespective of cultural identity. A decree from Lycian Telmessos, almost 100 years later than Sotas’ from Ionian Priene, strikes a very different note, though the Galatians are still named as enemies. The Telmessians honor Eumenes II as the city’s savior, who, invoking “the gods,” undertook a war against Prousias I, Ortiagon, and the Galatians, “not only on behalf of those subject to him, but on behalf of all inhabitants of Asia ([ὑπὲρ ἄ]λλων τῶν κατοικούντων τὴν Ἀσίαν).” An Attalid king, just as a Seleukid, could claim to be “king of Asia,” the title that the Suda, for example, applies to Attalos II.Footnote 139 That pseudo-Achaemenid rank required of its holder both a multifaceted cultural politics and a means of projecting power across the conceptual geography of Asia. In Asia, the ideological value of the victories over the Galatians was not Hellenic respectability, but a stronger claim to rule the nebulous territory allotted at Apameia.Footnote 140

The historiography of the Galatians’ crossing evokes the specter of Asia’s salvation from the beginning. Polybius, as preserved by Livy, also depicts the Gauls mounting their campaign from the European side of the Propontis where their cupidity overtook them, as “a desire for crossing into Asia seized them.”Footnote 141 The goal of what scholars take to have been a migration aimed at finding land for about 20,000 people is distorted into an expedition to plunder all of cis-Tauric Asia.Footnote 142 According to Livy, the Galatians divided up the revenues of the entire territory into three (tres partes), with the Trocmi drawing tribute from the Hellespont, the Tolistobogii living off Aeolis and Ionia, and the Tectosages assigned the interior. While it is clear from this account that everyone settled upland, in historical Galatia, the barbarians continued to threaten all of cis-Tauric Asia. Thus, when Polybius praises the Romans for suppressing the Galatians in 189, he explicitly commends them for removing that threat.Footnote 143 In a dramatic reversal, the local heroes of these narratives stand up to the Galatians, especially at places already imbued with meaning in myth, and ultimately eject them from Asia altogether, or at least from the more civilized reaches of its western seaboard. The Attalids vied with other Anatolian rivals for this role. During the War with Achaios, Polybius writes, Attalos I brought yet another band of Gauls over from Europe, the Aigosages. They damaged the cities of the Hellespont and threatened to take Ilion, but were fought off by the citizens of Alexandria Troas. In the end, Prousias freed the cities of the Hellespont from the danger. In effect, by correcting the mistake of Attalos, he reversed that of his forebearer Nicomedes I, giving “a good lesson to the barbarians from Europe in the future not to be overready to cross to Asia.”Footnote 144

The assault of the Aigosages on Ilion in 218 would have recalled an earlier attack on the same city during the initial migration in 279/8. By 218, Ilion seems to have received its sturdy, 2.5–3 m thick fortification wall. On the other hand, Strabo tells us that in 278, the Galatians, fresh from Europe, had reconnoitered Ilion as a potential stronghold. Finding it unwalled, and so unsuitable, they moved on, and the city survived unscathed.Footnote 145 The appearance of two such incidents in our sources may not be a coincidence, but instead an indication of the significance to observers and memory makers of the heroic defense of Troy, perhaps seen as a symbol for the salvation of Asia. In other words, if Ilion could hold, the rest of Asia could also survive the onslaught. This is the implication of a complex of oracles that seems to have circulated in the third century as a series of post eventum interpretations of the Gauls’ crossing. Addressed to the king of Bithynia, one oracle ominously forecast a wave of destruction, but in congratulating “the Hellespont” seems to hint at Ilion’s survival. “O thrice blessed Hellespont, and the divinely built walls of men … by divine commands which [city] the dreadful wolf will frighten under mighty compulsion.”Footnote 146 This oracle may have issued from from the Temple of Apollo in Chalcedon, though it was at some point in Antiquity associated with the name of the Chaonian prophetess Phaennis. Pausanias records her prophecy that an Attalos, ruling in Pergamos, son of a bull and reared by Zeus, would rout the Gauls who had ravaged Asia and harmed those who inhabited its coast.Footnote 147 While we cannot be certain of the precise origin or authorship of these oracles, nor their relationship to each other, together they preserve a precious, near-contemporary perspective on events. The mythic archetype through which the inhabitants of Asia understood the Gallic crossing was the Trojan, not the Persian War, and they called on their kings to play the part of Priam, not Miltiades. In managing the migration, individual kings may have, in certain contexts, claimed to be champions of the Greeks, but they remained the helmsmen of Hellenistic states on Asian soil.

Despite their intercourse with the enemy, the Attalids managed to spread the idea that they were responsible for, as Pausanias puts it, driving the Galatians away from the sea and out of “lower Asia” (κάτω Ἀσίας).Footnote 148 Pausanias’ testimony is what Karl Strobel has envisioned as the official Pergamene version of the settlement of the Galatians after the victory of Attalos I.Footnote 149 This version of events is demonstrably false: not only were individual Celts settled in the urban west of the peninsula, but Galatia as a constellation of tribal polities in central Anatolia in time became a protectorate of the enlarged kingdom of Pergamon.Footnote 150 Yet the important point to note here is that the Attalids’ territorial claim is to parts of Asia that are emptied out of Galatians. That this territorial claim of an Asia without Galatians was foundational for Pergamon is glimpsed on the long, blue marble Base of Philetairos on the island of Delos. Its verse inscription, which seems to have been erected by Attalos I, celebrates the founder’s achievements in war, principally, that “he drove the Galatians far beyond his frontiers (oikeioi horoi).” He did not merely defeat them; he expelled them, defining a border in the process.

This is an exaggeration, since while Philetairos may have skirmished with the Galatians, no major victory on the scale of Antiochos I’s Elephant Battle was ever trumpeted. Further, the verse essentially backdates the birth of the Attalid kingdom by depicting the vassal Philetairos chasing the barbarians beyond borders that were scarcely notional. Yet the rhetoric worked. By Strabo’s writing, it was impossible to conceive of a place as both Pergamene and permanently settled with Galatians.Footnote 151 The geographer describes a two-part process of settlement. First, the Galatians wandered about overrunning Attalid and Bithynian territory, and second, those two monarchies granted them permission to settle in historical Galatia. This neat picture obscures the fact that these dynasties contested each other’s borders and surely competed with Galatian leaders for influence in many places. It also exculpates those who bear the guilt of inviting the Galatians to Asia by crediting them with the creation of a homeland on the periphery of the Mediterranean system.