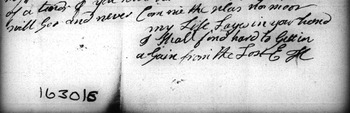

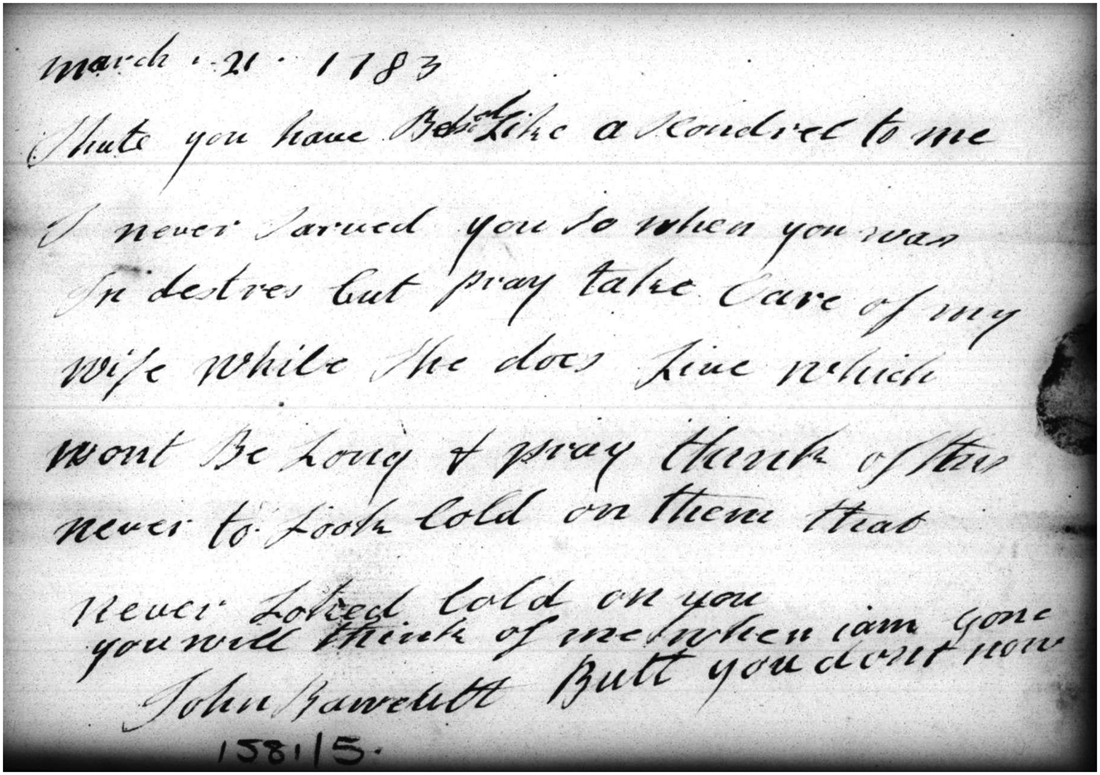

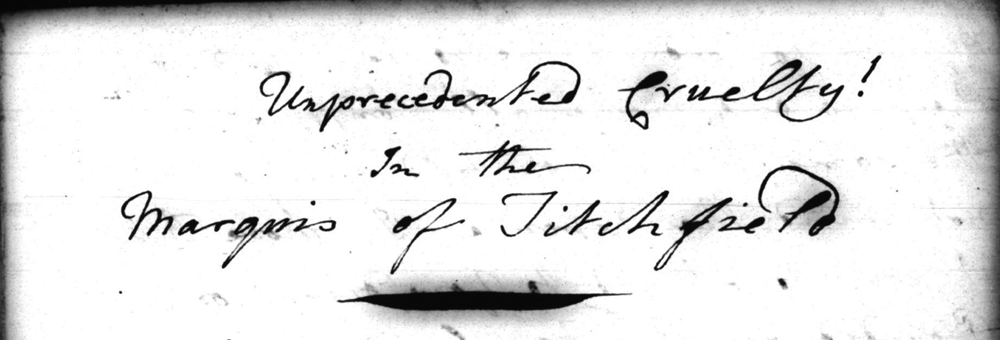

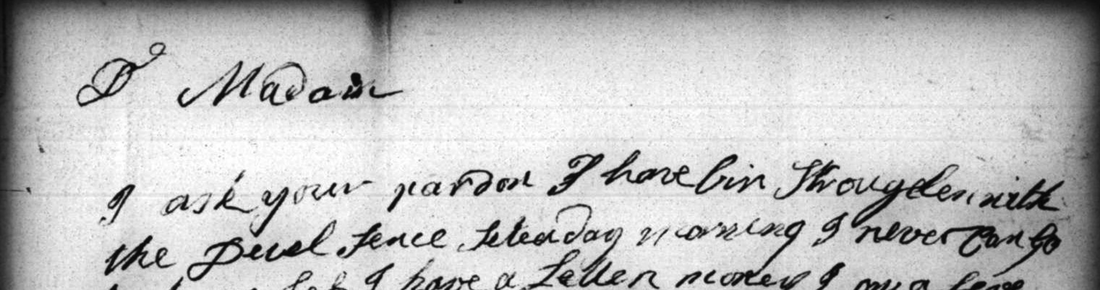

On 21 March 1783, John Bawcutt, an impoverished hostler lodging in an alehouse in Piccadilly, wrote two letters, one for his employer and one for a friend.Footnote 1 He folded them twice, wrote the name and location of the recipients on the back, and sealed each with a splodge of wax. When, three days later, Bawcutt was discovered hanging in his room, these letter were found ‘upon the Table’, along with his pocketbook.Footnote 2 ‘Shute you have BehavedLike a scondrel to me’, begins the letter to his employer.Footnote 3 ‘I never scorned you so when you was In destres…pray think of this never to look cold on them that never Loked cold on you you will think of me when i am gone Butt you dont now.’Footnote 4 Bawcutt's writing is steady but ‘unschooled’; the lack of punctuation gives his letter a breathless quality. The last three lines are scrunched into the bottom of the page, as he seemingly ran out of space (see Figure 1). The other letter is similarly crammed with his emotive, urgent writing, though less damning in tone.Footnote 5 These two letters are the only surviving documents written by this troubled man. They are complex, moving testimonies to the suffering and emotions of a particular individual, but are also fairly typical of suicide letters in this period, both in content and form. These important documents have not only been underused by historians, but few have considered their emotional content. Indeed, previous work has examined these documents from a literary perspective, and seen these letters as ‘elaborate performance[s]’.Footnote 6 This article adds a more historical, material approach; while firmly recognizing the potential mutability of meaning expressed in letters, and acknowledging the discursive conventions illuminated by other scholars, it explores these documents chiefly as personal attempts to communicate suffering, embedded in physical materials.

Figure 1. John Bawcutt's suicide letter to his employer, LL ref: WACWIC652230141. Copyright: Dean and Chapter of Westminster.

Historians’ lack of engagement with these textual objects is rooted, partly, in the field's prioritization of other epistemological inquiries. As Róisín Healy notes, the historiography has been characterized by a ‘focus on attitudes to suicide at the expense of empirical investigations’ – and at the expense of investigations which engage with suicidal emotions and experiences.Footnote 7 The field's most seminal work – Michael Macdonald and Terence Murphy's Sleepless souls – is a metanarrative about a shift in legal, religious, and cultural positions on suicide.Footnote 8 Their focus on ‘changes in attitudes and responses’, and argument that suicide was secularized and medicalized over the early modern period, have set the agenda for most subsequent anglophone histories.Footnote 9 R. A. Houston's important Punishing the dead?, ‘the result of two decades of mulling over’ Sleepless souls, similarly concentrated not on the ‘meaning of suicide’ to ‘the people who die’, but on ‘the attitudes and behaviour of those who interact with the self-murderer after death’.Footnote 10 Given this primary focus on ‘attitudes’, it is unsurprising that suicide letters, written by ‘the people who die’, have been somewhat overlooked. Of a 366-page monograph, Macdonald and Murphy allocate just ten pages to them.Footnote 11 R. A. Houston casts his eye over a single example, and studies by Jeffrey Watt, Donna Andrew, and Georgiana Laragy also pay them fairly limited attention.Footnote 12 Though this is understandable, given their focus on other important areas of inquiry which have helped to lay the foundation for the history of suicide, more needs to be done to understand these documents.

When suicide letters are used, there is a tendency for scholars to look at them from a literary perspective, which sees these documents as performative or fictive. While this has been fruitful for building a picture of the discursive contexts and textual conventions of these letters, and for considering their reception, the letters’ role in communicating real people's emotions has been overlooked. The key scholars – Macdonald and Murphy, as cultural historians, and Eric Parisot, a literary historian – see them as texts separated from their materiality and position within their author's social networks. This is because they are interested in practices of discursive self-fashioning within the letters, and in how they functioned when they were quoted in contemporary newspapers, as sometimes occurred. This is clearest in discussions of the differences between real suicide letters and potentially ‘bogus’ examples constructed by journalists. Macdonald and Murphy argue that distinguishing between them is ‘of little consequence’, because they are interested purely in ‘the literary models and rhetorical conventions that suicide notes employed’.Footnote 13 Parisot agrees, arguing that ‘focusing on questions of legitimacy only serves to understate the suicide note as an elaborate performance, framed and understood within a codified set of sentimental literary postures’.Footnote 14 But for a study that takes a more historical approach, and which is interested in the emotional experiences of suicidal people, it is important whether a suicide note was fake or genuine. Crucially, a purely literary perspective can also lead scholars to overlook the fact that real suicide letters always began as material objects; they were not a formless ‘literary substitute for speech and gesture’.Footnote 15 Even Victor Bailey, who commendably values suicide letters for what they reveal about the experiences of the suicidal in Victorian Hull, pursues a ‘contents analysis’, seeing them only as texts.Footnote 16 However, we cannot properly understand suicide letters without appreciating their materiality: their form, their structure, and the contexts of their creation. Thus, while Parisot and Macdonald and Murphy have illuminated the literary conventions activated in suicide letters, this article explores the material practices by which these letters were created.

In doing so, this article builds upon historians’ work that has long advocated for the materiality of texts. Scholars have shown that ‘meaning was generated by material as well as textual forms’, with handwriting, spacing, and the use of paper and seals all affecting how a letter was conveyed.Footnote 17 These scholars have also explored how emotion was communicated materially within letters, looking at how ‘emotional debris’, such as ink blots or scrawls, were left on the paper.Footnote 18 This article combines a ‘material’ approach with an appreciation for the emotionality of these documents. Considering the growth of the history of emotions, it is surprising that historians of suicide have remained focused on cultural attitudes or, if they do examine suicide letters, have been inclined to see them as ‘performative’ literary fictions, rather than testaments to people's emotional experiences.Footnote 19 Undoubtedly, there can be performative aspects to any act of speech or writing.Footnote 20 As a genre, letters can condition certain types of formal expression. Overall, however, this article adopts Rob Boddice's view that historians – being appreciative of cultural, social, and linguistic period contexts – should, to a fair degree, ‘take historical actors at their word’, respecting their expressions of emotion.Footnote 21 We should value these documents for the personal and situated affective truth they convey.

Of the thirty original letters used in this article, ten were written by members of the skilled working classes (such as artisans), and eleven by members of the lower working classes (such as manual labourers). Two were left by members of the upper classes, and three by those of middling status.Footnote 22 They can thus also offer a glimpse into the emotional writing practices of the ‘lower orders’. In mostly focusing on the writings of this group, and in seeking to privilege their perspectives as suicidal authors, this article feeds into a broader move within social and cultural history which Tim Hitchcock has described as a ‘new history from below’.Footnote 23 Countering the ‘process of refocusing away from the experience of the poor’ that occurred in the historiography of the 1980s and 1990s, historians have, in more recent years, demonstrated the rich social and emotional lives of the lower classes, which can be recovered in sources like pauper letters, court records, and settlement examinations.Footnote 24 This history has illuminated the complex affective lives of ordinary people. Indeed, the records created by or in interaction with the institutions that dealt with the poor, like parishes and workhouses, have been studied closely by historians seeking to better understand their lives, with work on pauper letters, in particular, delving into the ways in which the poor articulated their own experiences in writing.Footnote 25 Thomas Sokoll's work on the ‘orality’ of these letters, and his interest in issues of authorship and expression, has been important in developing our understanding of poor people's practices of self-authorship.Footnote 26 Wider developments in oral history, and considerations of the processes of giving testimony and the privileging of marginalized perspectives, are also part of the broader context for this study.Footnote 27 Notably, some of the work on eighteenth- and nineteenth-century poverty has also fruitfully engaged with issues of materiality. Houston has, for example, explored both the linguistic content and physicality of peasant petitions to landlords, while Steven King has studied workhouse inmates’ letters, including documents sewn with thread, ‘not as flat texts but as objects’.Footnote 28 This study, using textual objects also often preserved by the operation of the law, builds upon this important work.

The letters used here were written between 1716 and 1855; from the mid-eighteenth century, an average of two letters are located in each decade, with the notable exception of twelve in the 1780s.Footnote 29 In part, such documents have been underused because they are fairly rare, requiring extensive archival research; of 985 inquests (from 1700 to 1855) examined by the author, less than 3 per cent (twenty-three cases) contained suicide letters or full transcriptions.Footnote 30 Of the thirty letters, twenty were discovered as original documents within inquest files.Footnote 31 An additional six were found transcribed within the inquests, perhaps because the family kept the original, or because the ‘letter’ was written on a fixed medium such as a wall. Another four were found in family or other papers. Twenty-four of the letters were written in London, and one each in Maidstone, Maidenhead, Hull, Glinton (near Peterborough), Saffron Walden, and Dumfries. Aside from the great quantity of London inquests, the metropole is so over-represented because London coroners were particularly inclined to keep original letters. Suicide letters are mentioned in inquests in other locations – such as Cambridgeshire – but were not retained.Footnote 32 London also had higher literacy rates, making its population more able to write suicide letters.Footnote 33 Most people left a single letter; within this sample, three people left two. It should be noted that, of the thirty, twenty-three were written by men, a gender discrepancy reflective of the wider demographic suicide incidence.Footnote 34 Perhaps due to the limited sample size, significant gender differences in content or form are generally not detectable.

Most manuscript suicide letters have survived because they were preserved in the inquests that were carried out into suspected suicides. Although not the main focus here, given the substantial body of work that has explored legal responses to suicide and the rise and eventual dominance of insanity verdicts by the late eighteenth century, this article offers some insights into how suicide letters affected the sanity verdicts given at these inquests, increasing the chance of someone being pronounced a sane and thus criminally culpable felo de se.Footnote 35 It also gives evidence of how these letters were found, and how they ended up at the coronial courts. In so doing, it contributes to a wider historiography that has richly detailed the medico-legal response to suicide, while remaining more focused on the experiences of the suicidal.

Manuscript letters are the principal focus here, as they are very likely genuine (i.e. not forged by journalists). However, they will be complemented with suicide letters in other forms. First, this article draws upon an additional four letters found within printed collections; provenance has been established, even if they are not manuscripts.Footnote 36 Secondly, this article makes some use of suicide letters located in contemporary newspapers. For, while I disagree with Bailey that we can merely ‘assume’ that every newspaper example is genuine, Macdonald and Murphy's un-footnoted suggestion that ‘editors and writers were particularly fond of inventing’ suicide notes is not supported by the evidence.Footnote 37 Although it is important to flag discussions of printed examples, it would therefore be wrong to discount them all, because newspaper publication is the only way many of these important egodocuments have survived.Footnote 38 Furthermore, newspapers captured key instances of suicide notes written on non-moveable materials such as walls, which can provide insights into the wider and complex materiality of these texts.

This article will examine the process of writing and leaving a suicide letter, and explore how people used space and materials in order to communicate. It will then look closer at the textual and functional character of suicide letters, arguing that – rather than being general statements to the world – these letters were usually embedded in dialogues with specific people. Lastly, using Igor Kopytoff's notion of the ‘biography’ of objects, it will consider the afterlives of suicide letters, both intentional and unintentional.Footnote 39 Overall, it will argue that we gain a better sense of suicidal people's thoughts and emotions if we see their letters as material artefacts as well as texts. They were, indeed, objects used to materialize real people's suffering.

I

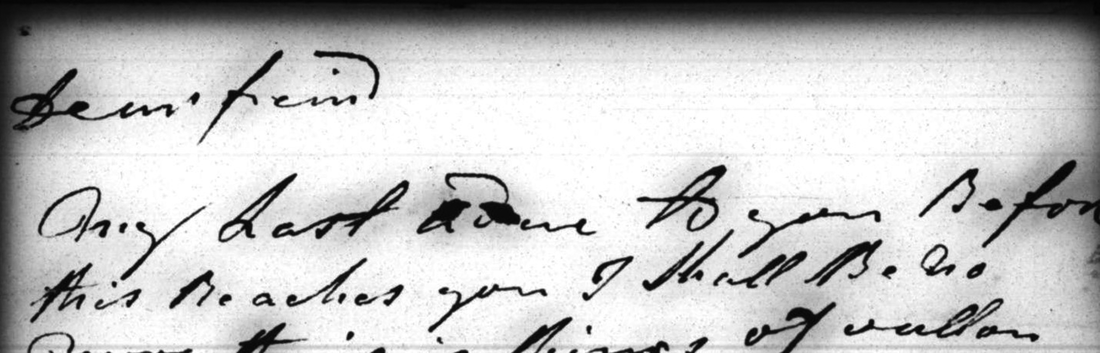

First, it is worth considering the spaces in which people wrote and left suicide letters. Susan Whyman, in her discussion of letter-writing practices among the poor and middling classes, notes that individuals were flexible in finding spaces in which to write, which were often less than ideal.Footnote 40 This is evidenced by the suicidal authors, who wrote their letters in haylofts, cramped lodging-rooms, and even – in the case of James Holt – a pub.Footnote 41 Yet, there was also something particular about suicide letter-writing. Whyman shows that ordinary letter-writers did ‘not expect privacy’, but most of these authors explicitly sought out solitary spaces. With the exception of Holt, they seem to have composed their documents alone. For, even when these writers had to find materials in other people's spaces, they retired to somewhere secluded. John Cuttle, the duchess of Portland's butler, went down to his colleague's room on the morning of his suicide in 1776, and ‘asked for Pen Ink and Paper’ which he ‘took away’. After his death, a letter was ‘found upon the Table in [the] Deced's room Sealed up and Addressed to her Grace the Dutchess of Portland in [the] Deced's hand writing’.Footnote 42 Written alone, the wax seal further secured the privacy of the letter's content.Footnote 43 Similarly, in 1782, Thomas Holman, lodging in a widow's pub in Covent Garden, asked ‘for a Pen and Ink’ from the bar-worker, and took them to his room. The next day, his door was found locked on the inside and, when his friends broke it down, they discovered his poisoned body, along with ‘two Letters Sealed under the Hat’ on his table. He had not only written his letters in seclusion and secured them with wax, but even hidden them – ‘Sealed’ under a Hat, in his friend's notable phrase – from the immediate view of entrants, perhaps in the hope that the recipient would also conceal them from the coronial authorities who were, as discussed more below, more likely to give felo de se verdicts in cases involving suicide letters.Footnote 44 Holman certainly had some desire to manage who learnt about his death, instructing his friend to ‘Keep my untimely Death a Secert’, but telling the woman who had rejected him to ‘Let My friends know my unhappy fate.’Footnote 45 He intended his letters to be read posthumously, beginning one of his letters ‘My Last adrese to you Before this Reaches you I Shall Be no More.’Footnote 46 Harriet Shelley, who killed herself in 1816, similarly began her letter by asserting that ‘When you read this letr. I shall be [no] more an inhabitant of this miserable world’, while Thomas Stafford, an army captain who killed himself in 1716, called himself ‘a dead friend’.Footnote 47 Like all letters, suicide notes ‘st[ood] in for face-to-face conversation’, but they also went one step further; as suicide was a taboo, and illegal, these letters allowed for the posthumous expression of particularly difficult, even forbidden, feelings of a desire for a self-inflicted death.Footnote 48 It is therefore unsurprising that suicidal people often sought out private spaces not only in which to die, but in which to write.

Suicidal people also used these spaces to place their letters in interactions with other materials, including their bodies. As in the cases above, it was common for letters to be left on a table in people's rooms, presumably because they would be easily found – and also, perhaps, because they were written there. The letter of Mary Bankes, a servant who was discovered hanging in her room in 1769, was found ‘upon a Table’ there, while Edward Henney, also discovered hanging in his room in London in 1782, was similarly found with a ‘Letter upon a Board before the Deced folded up and directed to whom it may concern.’Footnote 49 In such cases, suicide letters became ‘inscriptions that accompan[ied] an act’, able to explain why incomers were confronted with a corpse.Footnote 50 Such organization of the suicidal space was noted in newspapers. Reporting on Benjamin Robert Haydon's suicide in 1846, Reading Mercury wrote of ‘the extraordinary and careful arrangement of the room and the articles therein’, containing ‘packets of letters addressed to several persons’, his diary ‘open at the concluding page’ – reading ‘God forgive me! Amen’ – and his dead body.Footnote 51 Haydon's suicide was thus arranged in relation to his final messages to those he had known and loved.

People not only left their suicide letters on top of other objects, but inside them. Through this, they protected their contents, but also put them into intimate dialogue with other materials. Sometimes, people placed letters in their pockets. John Cook, a butler who drowned himself in 1798, left his coat ‘over the rails’ that encircled Hyde Park Bason, and ‘in the Coat pockets [two passers-by] found two Letters open’.Footnote 52 Though these letters were directed at his former employer, Cook also intended them ‘To be Published’.Footnote 53 By placing them in a communal space, Cook inserted them into the public sphere, using his coat to clearly align them with his nearby body; consequently, he also identified himself. Other authors placed their letters in their gloves. Isaac Brown, a soldier who hanged himself from the ‘bow of a tree’ in Hyde Park in 1811, had written a letter ‘which was found in one of [his] gloves directed to his wife’.Footnote 54 By leaving it on his body, he escaped an in-person encounter, but still ensured that it would probably reach her, though passing through others’ hands. As postage was costly in this period, this also allowed poorer people's letters to reach loved ones for free.Footnote 55 Some authors used both pockets and gloves, endowing both with meaning. In 1837, the Monmouthshire Merlin described the suicide of Charles Stuart M'Vegh, a medical student who shot himself. As it explained, ‘four letters were found in his pocket, taking leave of various friends’; an additional letter was discovered in the glove of a lover who had rejected him – which he ‘had about him’ – reading ‘Leave this glove on me in the grave.’Footnote 56 It was common for people to be buried wearing gloves, but there was a deeper, unsettling symbolism in burying a ‘self-murdered’ man with the glove of the woman who had rejected him, especially given the significance of gloves in courtship rituals, which could signify ‘winning a lady's hand’.Footnote 57

Authors thus used suicide letters to communicate with and through different materials. This could still happen when letters were sent rather than left, for they could be conveyed with other objects. In 1716, Stafford, mentioned above, sent a long suicide letter to a colleague, Captain Martell, along with his:

writing Box, the key of whch is here

Inclosed, In that part of the Box that holds the pens and Ink, you'l find my

Purse wth 29: Guineas; in the other, my Pockett Book relateing to paying the

Regiment, &c.Footnote 58

Stafford also sent a trunk containing cheques for his soldiers. He thus used this letter to settle his occupational affairs; he apologized for causing this trouble, ‘but when I consider it will be the last; I readily ghess it will be forgiven’.Footnote 59 Crucially, though, he also sent something else:

I beg you'l take yor fine New Hatt –

again, it is in the Top of my Trunk –

But has never been worn. I am very –

Sorry you put yousel to that Expence

for soe Miserable a Creature as I amFootnote 60

In returning Martell's gift, Stafford was settling his affairs, but he was also articulating his misery and sense of unworthiness. Though this letter traversed a great distance – Dumfries to Lancashire – it remained carefully aligned with other meaningful objects that communicated Stafford's sadness and sense of estrangement.

Suicide letters were related, in complex ways, to space and other materials. Occasionally, space itself was harnessed to create a final message. In 1849, The Welshman reported on the suicide of Andrew Turnball in Carlisle gaol, who wrote a message on his cell walls with his only writing-tool: ‘a burnt stick’.Footnote 61 Given his lack of letter-materials, Turnbull creatively turned to the use of space to express a variety of distinct thoughts; his cell became his paper. Below the window, he wrote that ‘The two Hoggs are guilty – I am innocent; I will not come into the hands of man’, and above the fireplace, he expressed that ‘I commit my soul to God that gave it me – take my body to my father's burying place.’Footnote 62 Above his bed, he finally addressed his wife and child, writing: ‘My dear, you and I were lovely, but I am torn from thy breast; don't weep for me. Jemimah, my dearest, my heart's delight and treasure, I am innocent – I die with pleasure – we'll meet again with pleasure…God bless you all.’Footnote 63 Someone looking over the room would have seen the progression of this ‘muralized’ letter, beginning with his cry for exoneration, and ending with a farewell to his family above his bed, a resting place.Footnote 64

Others also deftly used space to ‘speak’. In 1797, The Monthly Magazine reported that James Doe, a potter, drowned himself in Sea-Mill Dock in Bristol. In one of the surrounding, abandoned tenements, his suicide ‘diary’ was discovered on the walls, ‘well written with a black-lead pencil’.Footnote 65 This diary-letter spanned the four days from the 11th to the 14th of September, and was mostly written in the attic, with one part at the bottom of the staircase, and the final entry ‘in a lower room’.Footnote 66 Doe thus literally filled the house with his words, finishing at its bottom, where he seemingly wrote his final entry before leaving to die. It appears that Doe used mural visualization in order to document and ‘see’ his thoughts. For his diary-letter was a mixture of personal reflections and religious maxims, written as he was ‘fasting and praying’. In one part, he expressed that he was ‘invested of a strong desire of life, and dreadful fear of approaching God's bar’.Footnote 67 In another, however, he wrote that suicide ‘must be my fate – I have no other relief’, and finally ended with resignation: ‘Oh Lord, how weary I am of life! If my acquaintance should happen to see the writing, he will remember, perhaps, the hand of an old former acquaintance.’Footnote 68 This final sentence indicates that Doe was aware of the semi-publicity of his message, even believing that his handwriting might identify him.

Indeed, while these messages were written privately, suicidal authors knew that space could be used to broadcast a semi-public message. Such was the case with James Greffess, a tallow chandler in Maidstone, who hanged himself in 1783. As his colleague explained at his inquest, Greffess wrote a message on the workshop's shutters: ‘This rash Action was done my Master and Mistress not being satisfied my not being able to do my Business my Wife and Children being in great distress and could not bear to see them go to the Workhouse.’Footnote 69 In writing it on the building's very fabric, Greffess used space to explicitly connect his suicide to his employers’ maltreatment; unlike a paper letter, which could be discarded, Greffess's words had to be scrubbed off. It therefore actively materialized his conflict with his employers, which other colleagues could read.

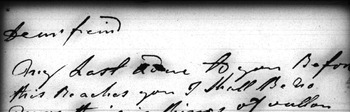

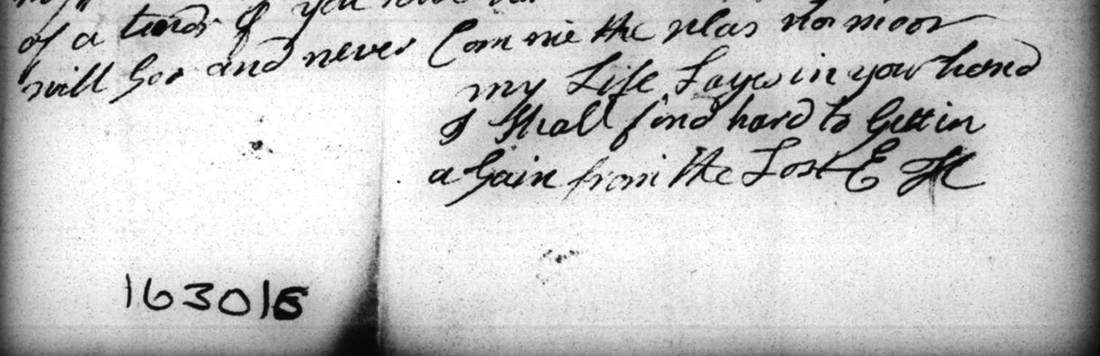

In paper letters too – which were much more common – the spatiality and materiality of paper were used to convey meaning. Most suicide letters were wedded to the epistolary form, suggesting that their authors saw them as letters. Of the twenty-eight manuscript paper letters, a majority of sixteen used letter-paper of a standard size, in which one large leaf (usually bought in a four-leaf ‘quire’) was folded twice over, and cut or torn to produce eight pages.Footnote 70 Another nine people used smaller pieces, or occasionally pages of a larger size. Perhaps this was all they had to hand, or they only needed a certain amount of space. As with other types of letter, most were folded and addressed on the front, and often sealed with wax. As we can see with Mary Wainwright Atherstone's letter of c. 1830 (see Figure 2), this created a particular form of progression over the epistolary space, and allowed for a considerable amount of writing to be enclosed in a small, secured packet, not requiring an envelope, as was conventional at this time.Footnote 71 Some examples were written on other forms of paper; Morris Williams's message was written on the back of a tattered bill.Footnote 72 However, these were exceptional.

Figure 2. Mary Wainwright Atherstone's suicide letter to her husband, folded and sealed, Somerset Heritage Centre, SHC DD/SAS/G3016/5/18. Reproduced with kind permission of the Somerset Archaeological and Natural History Society and the South West Heritage Trust.

While authors broadly followed the conventions of epistolary materiality, they could also be creative in their use of established materials. Though we have no surviving manuscript examples – mainly because this practice was not widespread until the mid-nineteenth century – three of the newspaper letters from this time were reportedly written on black-edged mourning-paper.Footnote 73 The joint letter of Elizabeth Williams and Charles William Duckett, who killed themselves in London in 1844, reportedly had ‘deep black borders’.Footnote 74 Black borders were particularly wide during the first year of mourning, suggesting that Williams and Duckett were explicitly prefiguring a sense of grief. Black wax seals, and black-bordered envelopes, were also supposedly used.Footnote 75 Of course, newspapers may have included these details to emphasize the death-act, or these materials may simply have been to hand; equally, though, these cases indicate that epistolary mourning conventions could be utilized to articulate a sense of grief.

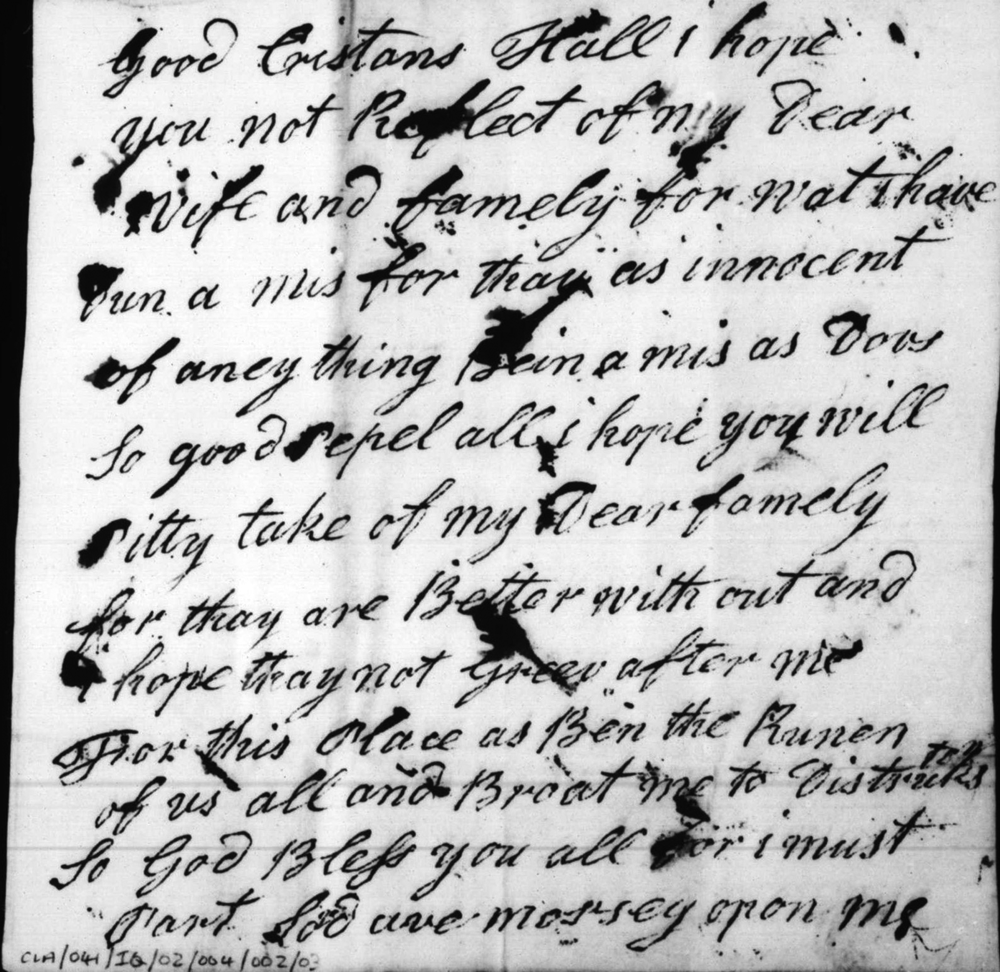

Suicidal authors could also be creative in their use of a page's space. In Cook's letter – mentioned above – he made an unusual use of space at the opening to express his outrage. While the rest of his text mostly filled his columns, Cook centred the opening of his letter, as if at the beginning of a play, pamphlet or newspaper article: ‘Unprecedented Cruelty! / In the / Marquis of Titchfield’ (see Figure 3).Footnote 76 As such, he combined epistolary and dramatic forms to articulate his severe mistreatment. Contrastingly, E. H., an impoverished woman who drowned herself in Hyde Park Bason in 1782, used space at the end of her letter in a way that emphasized her finishing words. While she wrote most of the letter across the page's breadth, the last three lines occupied little more than half (Figure 4). The reader is thus drawn to them, and ultimately to E. H.'s anguished final plea, that:

Figure 3. The opening of John Cook's suicide letter, Cook, LL ref: WACWIC652380829. Copyright: Dean and Chapter of Westminster.

Figure 4. The end of E. H.'s suicide letter, LL ref: WACWIC652230559. Copyright: Dean and Chapter of Westminster.

In her other suicide letter, E. H. did not do this, indicating that she may have reworked epistolary conventions to accentuate this particular ending, and thus the reader's direct relation to her distress.

In other cases, letter-writers seemingly battled against the space – or lack of space – on their page. Daybell notes that letter-writers often used space to ‘exhibit due deference to a recipient of superior social standing, while fuller letters…filling the entire page and continuing in the margins indicate[d] less social rigidity, and perhaps more emotional or sentimental reasons for writing’.Footnote 78 Certainly, the crammed nature of some letters indicates the great emotional significance of their words: in attempting to fit as much they could onto a page, authors showed their need to ‘speak’. In both his small letters, Bawcutt (discussed at the beginning) packed in his words as he reached the page's end. In the clearest example of this, in his letter to a friend, these words were about his wife's care. Bawcutt asked him to ‘show [a person] this Letter & if he won[t] Let hur have som [money?] ishall think him as Bad as the Rest pray do what you can for my Wife’.Footnote 79 This was vital to him; Bawcutt felt that ‘my going to Prison has been the death [of me] and will be the death of hur tow’, so he wanted others to help her.Footnote 80 Though the material worked against him, he thus fought against the space's limits.

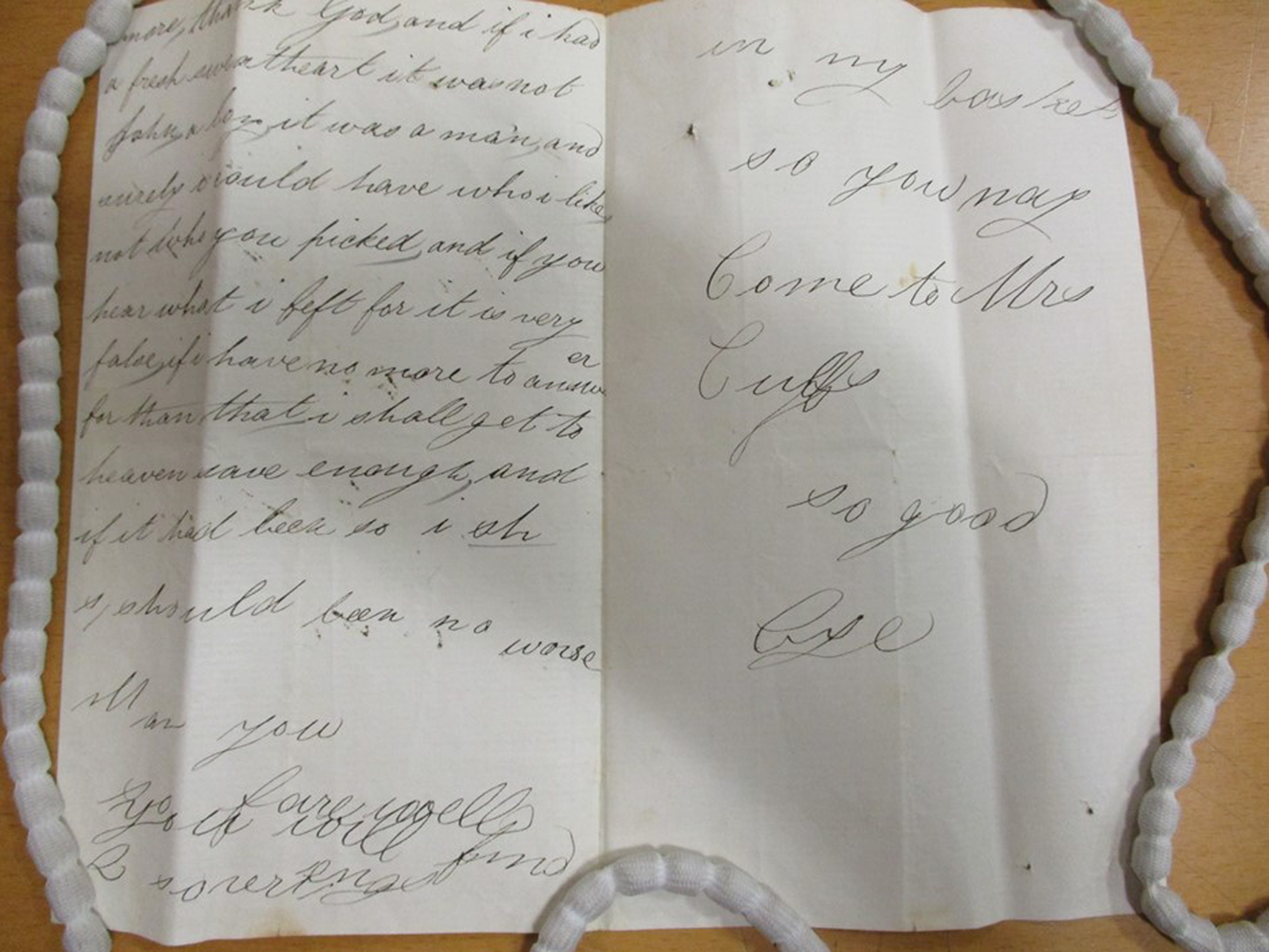

In other cases, authors battled both the page's space, their writing-tools, and even the materiality of their own bodies. William Bull, a labourer who hanged himself in London in 1791, left his suicide letter spattered with ink blots. He was an ‘unschooled’ writer who potentially struggled with his quill (see Figure 5). The blots may have also, however, been caused by tears.Footnote 81 Such bodily materiality is manifest in the letter of Susannah Crampton, a twenty-year-old dismissed chemist's servant who poisoned herself in Glinton in 1855. She left a long suicide letter which, as she began to be affected by the laudanum, degenerated before her. Crampton lost a grip of the space that she had, previously, precisely filled with her words; her letters became large and disordered as she began to lose consciousness (see Figure 6). This is a startling, poignant example of a person's need to communicate, even as they fought against their own body and the paper before them.

Figure 5. William Bull's suicide letter, covered in ink blots, William Bull, 6 January 1791, City of London Inquisitions, London Metropolitan Archives, MS: CLA/041/IQ/02/004, LL ref: LMCLIC650040009. Copyright: London Metropolitan Archives, City of London.

Figure 6. Susannah Crampton's suicide letter, Susannah Crampton, 18 September 1855, Peterborough Inquisitions, Peterborough Archives, box V6277, PCI 151. Photograph: Sophie Michell. Copyright: Peterborough Archives.

II

The majority of suicide letters were, like most letters, directed to specific people.Footnote 82 Macdonald, Murphy, and Parisot are captivated by the notion of press publication, and the idea that suicide letters were literary ‘performance[s] mounted before a mixed crowd of intimates and unknowns’, in which ‘suicides could choose which part of the house they played to’.Footnote 83 Macdonald and Murphy argue that, by the 1770s, the suicide letter was an established ‘literary subgenre’.Footnote 84 However, as he acknowledges, Parisot only found twenty-two letters in London newspapers and magazines from 1750 to 1779.Footnote 85 This rarity is even truer of the provincial press. Within a database of nearly 250,000 Welsh newspaper articles from 1804 to 1850, I have found only sixty-seven printed suicide letters; they therefore appeared in less than three in every 10,000 articles.Footnote 86 Further, in the manuscript letters used here, there is only one instance of a person asking for their letter to be published – and one, notably, explicitly requesting that her letter ‘May not be advetsd in the Noue [News]’.Footnote 87 Parisot highlights the social nature of suicide notes, and the ‘communal ties’ they drew upon, but still sees these in terms of ‘devices of literary self-fashioning’.Footnote 88 Instead, I would emphasize that the social ties that suicidal authors invoked were really experienced by them.

Over three-quarters of the manuscript letters were addressed to specific people or groups of people.Footnote 89 Letters have ‘strong structural conventions’, usually beginning with ‘address’, and then progressing to ‘salutation, ‘business’, farewell’, and ‘signature’.Footnote 90 Broadly, suicide letters reflected these conventions, and opened with addresses: ‘Dear Bet’, ‘Dear friend’, ‘Dr Madam’, ‘Dearest Lydia’.Footnote 91 In fact, after ‘God’, ‘dear’ was the most common word in the letters. Some opening addresses might seem unusual – such as Bankes's beginning, ‘Mrs Brocker you your husband & mrs Cane by name’ – but, as Tony Fairman explains in discussing pauper letters, less experienced writers like Bankes often began letters with such formally unconventional openings.Footnote 92 However, even these writers often made attempts to obey the visual conventions of opening addresses. E. H. opened a letter with ‘Dr Madam’, leaving a space before continuing onto another line (see Figure 7). The more experienced, but certainly not highly educated, Holman also did the same (see Figure 8). In this way, most suicide letters were not only addressed to specific people, but in ways which were formally comprehensible to their intended readers.

Figure 7. The opening of E. H.'s letter, LL ref: WACWIC652230559. Copyright: Dean and Chapter of Westminster.

Figure 8. The opening of Thomas Holman's letter, LL ref: WACWIC652220335. Copyright: Dean and Chapter of Westminster.

Mostly, these readers were known to the authors. As Bruce Redford notes, contemporary letters were intimately related to ‘conversation’, complementing and substituting interpersonal discourse.Footnote 93 Though suicide letters also represented a conversation's end, we must recognize them as parts of pre-existing dialogues, because that is how they functioned for the authors. The letters reference past and present circumstances, relationships and conversations; they were material and textual objects completely embedded in people's intimate interpersonal lives.

To explore this, we must consider why individuals left suicide letters. Most commonly, it was to give some explanation for their suicide.Footnote 94 Within this, authors had an opportunity to express their pain to loved ones. In a society that generally condemned suicide, explanations could also be justifications. Before she drowned herself, Shelley left a long, emotional letter to her sister, in which she explained that ‘Too wretched to exert myself lowered in the opinion of everyone why should I drag on a miserable existence embittered by past recollections & not one ray of hope to rest on for the future.’Footnote 95 Later in the letter, she expressed regret: ‘dear amiable woman that I had never left you oh! That I had always taken your advice. I might have lived long & happy but weak & unsteady have rushed on my own destruction.’Footnote 96 In so doing, Shelley referenced past conversations with her sister, with the ‘advice’ that she had been given – but not ‘taken’ – a spectral presence in the exchange. In a society that drew connections between sin and femaleness, and conditioned women to accept suffering and self-sacrifice, it is unsurprising that this sort of self-blame was more common in women's letters, appearing in two out of seven letters (compared to three out of twenty-three letters left by men). Notably, though, men and women were similarly likely to blame others for their deaths, with nearly half (eleven) of the men's letters, and just over half (four) of the women's letters blaming others for their suicides. Thus, while women were more likely to self-blame, overall, they were still more likely to blame others than themselves.

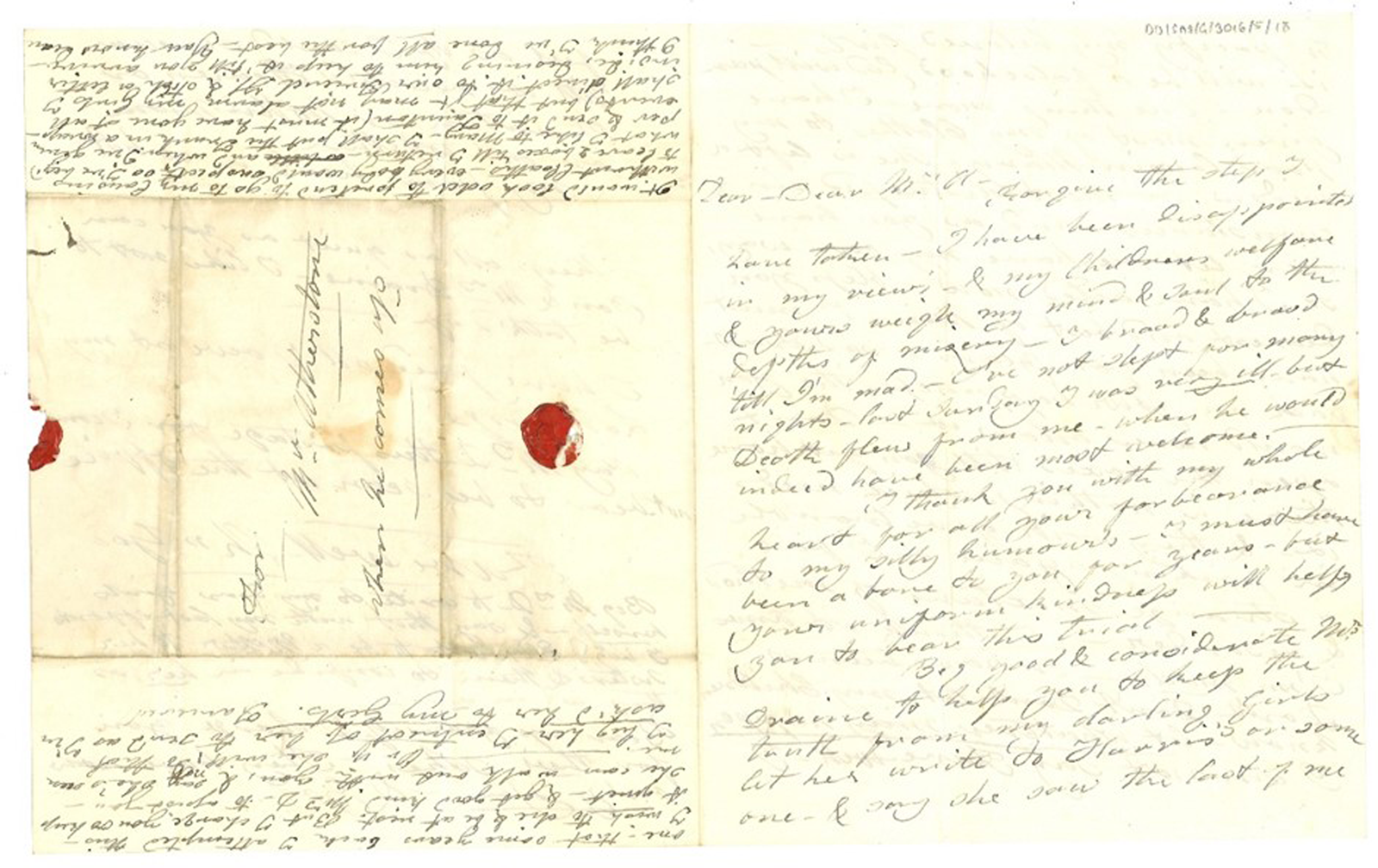

Atherstone similarly alluded to past interactions in attempting to explain her suicide to her husband. After describing how ‘I brood & brood ‘till I'm mad’, she expressed that ‘I thank you with my whole heart for all your forbearance to my silly humours – I must have been a bore to you for years – ’.Footnote 97 Atherstone thus saw this letter as the final piece in a long line of difficult interactions; this reference to ‘years’ of ‘silly humours’ also stood in for a fuller account. Sometimes, letters alluded to more recent situations. Holman, mentioned above, left one of his suicide letters to his landlady Elizabeth Cave, to explain that he had ‘Sacrificed a Life for the Love of you…I hope god will forgive me for the rashness of my Crime But [I] Could never Bear to Se you in the Arms of anather Man.’Footnote 98 As Cave clarified at his inquest, Holman ‘often talked to her about his wish to Marry her’, but she had ‘answered him that she did not intend to Marry for she had enough to do to take care of her Family’.Footnote 99 Holman's letter was thus the last piece in their dialogue, which Cave justified at court, maintaining that she ‘never gave the Deceased any encouragement respecting Marriage’.Footnote 100

Within Holman's ‘explanation’, there lay a barely hidden allocation of blame. Indeed, many suicide letters were inserted into blameful dialogues, with nearly half the letters being accusatory.Footnote 101 One of the most vituperative examples was Cook's letter, directed at his former employer the marquis of Titchfield. Although Cook also sought a public audience, this letter functioned as the final part of their antagonistic dialogue, stemming from the marquis's decision to dismiss Cook and accuse him of wrongdoing. Cook addressed the marquis throughout, writing: ‘you Promis'd me your Support. You Promis'd me £120 pr. Year, you Promis'd to Provide for me If I did not Succeed; Neither Promise did you fulfill…You Ruin'd me for Ever O fie! O fie!…you Rob'd me of the greatest Treasure man can Enjoy.’Footnote 102 Clearly referencing the specificities of the business that had passed between them, he used this final letter to speak to his ‘better’ in bold, frank terms.

The dialogues within which blameful suicide letters were embedded are especially clear when we have access to a wider epistolary thread. Although his replies are lost, the letters which Mary Wollstonecraft sent to her lover, Gilbert Imlay, before she wrote her intended final letter of 1795, have survived.Footnote 103 In them, Wollstonecraft's successive attempts to provoke compassion and push Imlay to meet with her can be seen. In the penultimate letter, Wollstonecraft refers to his ‘last unkind letter’, and talks of her ‘extreme anguish’ and desperation that he will ‘see me once more’.Footnote 104 Wollstonecraft's next (and also her suicide) letter – which begins ‘I write to you now on my knees’, and in which she hopes that he may ‘never know by experience what you have made me endure’ – is thus clearly embedded within a specific dialogue.Footnote 105

In other letters, attempts to give instructions about the distribution of property, the processes of burial, the care of loved ones, or even the reader's future conduct were also enmeshed within specific emotional, discursive, and material relationships. Instructions appeared in nearly two-thirds of the letters.Footnote 106 The most common instructions related to the author's property. In such cases, suicide letters partly functioned as wills, offering an informal way to bestow goods. George Davis, an impoverished carpenter who poisoned himself in London in 1796, wrote to his friend that:

I shall have

the Keyes of my Box & Chest with you & desire that You

will take it upon yourself to keep it and do as you like

with my Chest & to also you may call for them as there

will be Letters at Mr Tannel Handcocks & your receiving

them for they will not be of aney use to me.Footnote 107

Davis knew the reader well – he was his ‘friend’ – and was clearly implanted within the same social networks; there is assumed knowledge about who and where Handcocks is, and about his ‘Box & Chest’. This letter is not an ‘elaborate performance’ replete with literary artifice, but rather part of a specific conversation about the minutiae of Davis's material life.Footnote 108 The same is true when letter-writers gave instructions about their bodies and funerals. Stafford expressed to his colleague and friend that:

I hope, and doubt not, but you'l have that reguard to a dead friend,

and the rest of the Choar to a Brother Officer, as to Insist upon a

decent Buryall, and in such place as you shall think proper,

notwithstanding the Clergy, and their Creatures may object agst it. – Footnote 109

Again, Stafford knew his reader well, appealing to his ‘reguard to a dead friend’. In hoping that his friend would ‘Insist’ on a proper burial against the presumed resistance of the church – in 1716, most suicides were buried in unconsecrated grounds, and even if someone was not decreed felo de se, there could be resistance to giving them a proper religious burial – Stafford made reference to a strong friendship that would hopefully help him even beyond death.Footnote 110

For, while suicide letters were generally the last part of an interpersonal dialogue, they often also dealt with the posthumous future. Undoubtedly, some letter-writers explicitly ended the conversation. Richard Coulthard, a book-keeper who cut his throat in 1785, wrote to his father that he should ‘forget your most unworthy Son’.Footnote 111 Similarly, Bull hoped that his family would ‘not Greeve after me’.Footnote 112 However, though they were saying goodbye, others projected their relationship with the addressee into the future. Atherstone asked that her husband would ‘Forgive the steps I have taken’, thus envisaging a sort of post-mortem interaction between them.Footnote 113 Bawcutt, mentioned above, imagined that his reader would ‘think of me when I am gone’.Footnote 114 Others supposedly went even further. In 1771, the Craftsman or Say's Weekly Journal reported on the suicide of Philip James O'Neil, an Irishman living in London. At the end of one of his many letters, addressed to a ‘Friend’, Bingham Ellison Esq., O'Neil wrote that ‘If I should chance to get into the Elysian Fields, I will keep you a good place’, thus envisaging a reunion of the two men, and the continuation of their relationship.Footnote 115 This conversation was not so much over, as hopefully consigned to another time and space.

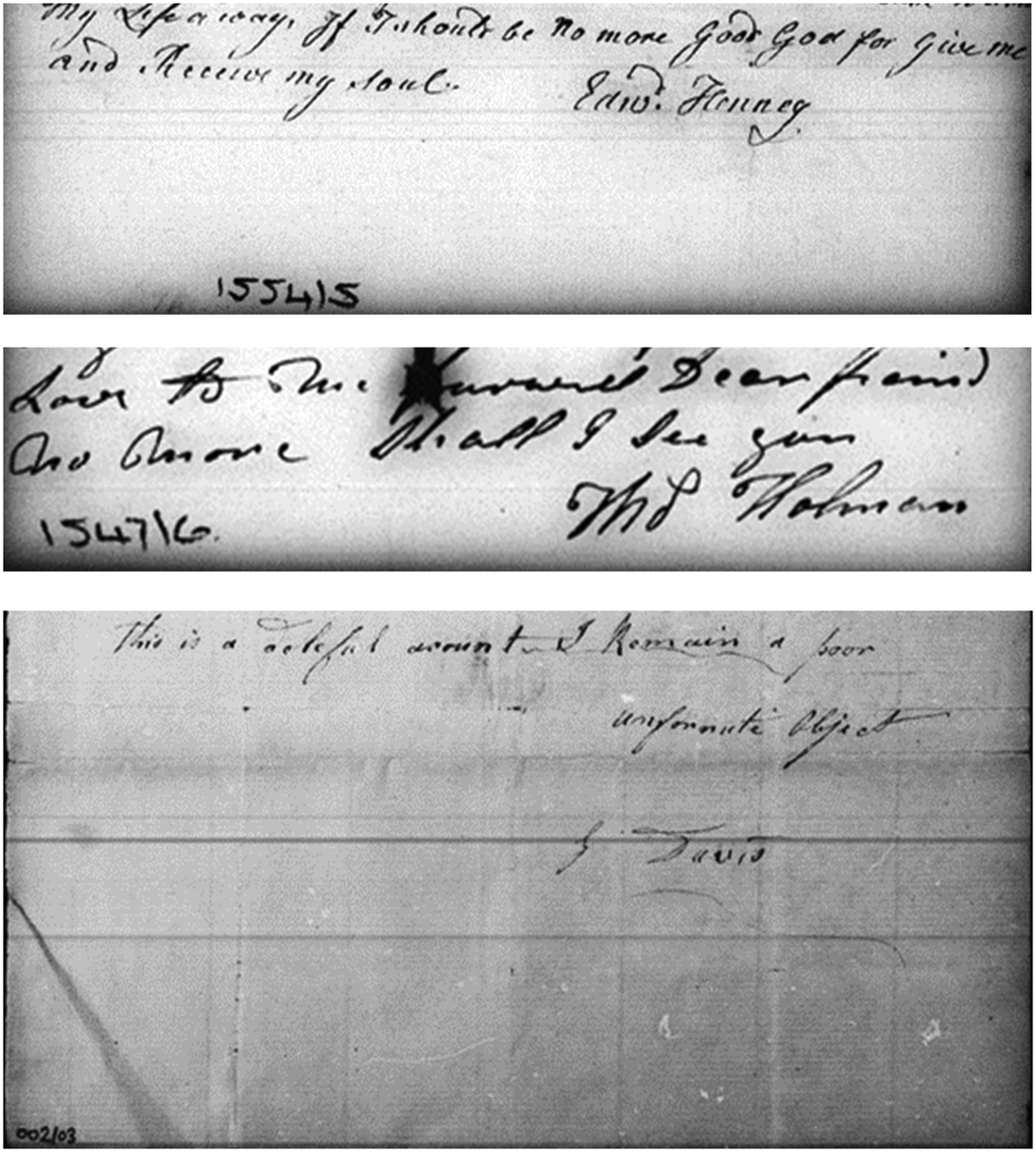

As with their addresses, when ending their letters, most authors reaffirmed their epistolary status, explicitly signing their farewells. In the context of suicides, which generally prompted inquests, individuals may have also signed their names to enhance their letter's credibility; note how Bankes wrote ‘this I Sine with my dien hand’.Footnote 116 Almost two-thirds of the manuscript letters feature finishing signatures.Footnote 117 As was customary, most people signed their names in the bottom-right corner, as seen in the case of letters by Henney, Holman, and Davis (see Figure 9). Notably, seven people put an epithet at the beginning or end of their signature: ‘James Holt sufferer’, ‘the lost E. H.’, ‘the unhapy Jacob Miers’, ‘the unfortunate Harriet S.’.Footnote 118 In this period, it was usual to sign off with a customary epithet such as ‘your humble servant’ or ‘your loving friend’.Footnote 119 Here, however, this convention was altered to emphasize the writer's pain. Such adaptions demonstrate how suicidal people used, but also creatively modified, the epistolary form to create powerful, emotive documents suited to communicating their distress and suffering to specific persons.

Figure 9. Finishing signatures of the letters of Edward Henney (LL ref: WACWIC652220407), Thomas Holman (LL ref: WACWIC652220335), and George Davis (MS: CLA/041/IQ/02/009, LL ref: LMCLIC650090011). Copyright: Dean and Chapter of Westminster and London Metropolitan Archives, City of London.

In thinking about the epistolary practices that suicidal authors employed, it is worth briefly considering the issue of others’ reception. The suicide letters demonstrate a socially diverse culture of literacy and epistolary practice, not only terms of the author's use of literacy, but in terms of the expectation, projected in the letters, that the reader could receive the information communicated within. Occasional instructions to remain silent about their suicidal death, or emotionally charged discussions of specific personal interactions, clearly envisaged an unmediated line of communication, though it is of course possible that the contents of suicide letters could be passed on to other, illiterate persons.Footnote 120 Though it is not the main focus of this article, receiving a suicide letter could be a deeply emotional experience, which could assuage or deepen grief. For example, in 1800, in a letter to her brother on the occasion of her other brother's suicide, an unnamed woman described him leaving ‘a most affecting letter…[which] will convince you it would have been impossible (even if he had preserved his senses) ever to have been happy again in this World and that I am sure will reconcile you to his loss’.Footnote 121 These writings were made letters, in part, by the expectation of reception, and while this is beyond the scope of this article, the personal, rather than journalistic, reception of suicide letters presents a worthy area of future research.

III

Though they represented important acts of self-authorship, suicide notes thus had social and material afterlives beyond the author's death. Kopytoff proposes a ‘biography’ of objects, arguing that there are successive ‘ages’ in a thing's ‘life’, from, for example, construction to exchange to use to memorialization.Footnote 122 Sometimes, a letter's posthumous ‘biography’ or ‘afterlife’ was clearly envisaged by the author, the text being constructed to influence social and legal processes. Such was the case with J. L. Davis, a forty-year-old failed dentist in Essex, who killed himself in 1816. He contended that ‘I go to bed in the hopes of not opening my eyes again in this World & I write this just to say as much & to arouse the Jury…that this is as clear a case of felo de se as ever took place.’Footnote 123 A felo de se inquest verdict was given in cases where the deceased was deemed to be sane and therefore criminally culpable for their suicide. While, by this date, well over 90 per cent of suicides were given the alternative non compos mentis (‘insane’) verdict, the jury in Davis's case ruled him a felo de se.Footnote 124 Davis's letter undoubtedly influenced this decision. It is unclear why he wrote it; perhaps he wanted to be thought of as sensible, or sought to disinherit his family of his property – a family which consisted of four siblings, with whom he was, as an acquaintance described, ‘not on good terms’ – a potential consequence of this verdict. Regardless, Davis envisaged an active afterlife for his letter.Footnote 125

Suicide letters were used to influence the coroner's court in other ways, though the intention was not usually so explicit. Since the inquest documents were formulaic in reporting verdicts, we must examine the newspapers. In 1846, Monmouthshire Merlin reported the suicide of Emmeline Fullilove, a twenty-year-old London compositor's wife. She left a letter in which she explained that her abusive, philandering husband had caused her death, writing ‘let him know that my last dying curse was that he may rot and die a despised wretch as he is’.Footnote 126 The words of dying people were often invested with power, and this letter clearly had a significant effect upon the court, for, ‘At the request of the jury’, her husband ‘received a severe lecture from the Coroner, who told him he ought to reflect, as long as he lived, on the base and heartless conduct to his late wife’.Footnote 127 The jury even ‘regretted that they could not send him to prison’.Footnote 128 Perhaps Fullilove had envisaged this ‘afterlife’ for her letter – she had predicted that ‘Judgement will someday overtake’ her husband.Footnote 129 Equally, however, this letter, addressed to her mother, may have assumed an unforeseen afterlife.

For authors were ultimately not in control of their letters’ afterlives. Even if they were not so explicit as Davis, just by writing a suicide letter, people increased their chance of being decreed felones de se. As noted, while only 2 per cent of people by the 1790s were classed felo de se, over one fifth of the letter-writers were pronounced thus.Footnote 130 Of course, this sample size is small, but it indicates that people who left a suicide letter were ten times more likely to be classed felo de se. By writing her letter, Crampton, discussed above, became one of the very few felones de se at the late date of 1855. In her somewhat confused letter, Crampton wrote that ‘if I had a fresh sweetheart it was not John, a boy, it was a man and surely I could have who I like not who you picked…I have no more to announce for then that I shall get to heaven save enough.’Footnote 131 Perhaps it was Crampton's wilfulness – seemingly claiming that she should be able to pick her suitors – or her assumption of Godly forgiveness that incensed the jury to give this exceptional verdict. It seems unlikely that this was her intention, but in writing suicide letters, some people seemingly endangered their status as non compos mentis by giving voice to the intentionality of their act.Footnote 132 Macdonald and Murphy have noted that, by the late eighteenth century, felo de se verdicts were often reserved for ‘marginal members of the community’ such as ‘criminals’ and ‘people in disgrace’, as a de facto punishment for these acts rather than their suicide itself.Footnote 133 Though they did not necessarily commit a crime, in writing letters that showed a certain shamefacedness, evidenced disgrace, and perhaps angered the community, as in Crampton's case, suicidal authors arguably increased the chance of this punitive use of felo de se verdicts. Others, like Davis above, left such explicit written declarations of their sanity that it was impossible for juries to give non compos mentis verdicts. However, it should be noted that, in other cases, personal writings were used by the courts to evidence mental affliction, and support a non compos mentis verdict. While it is often unclear exactly how juries responded to suicide letters – for the majority of the manuscript letters used here, the accompanying inquest evidences little in-court discussion of the suicide letters, beyond confirming they were in the hand of the deceased – some inquests indicate that they were used in this way. In the inquest into William Platt's death, a letter he wrote shortly before his suicide was thought to ‘plainly she[w] he was in a state of despondency which deranged his mind’.Footnote 134 Thus, while leaving a suicide letter decreased the chance of a non compos mentis verdict, these objects could also be used to demonstrate insanity.

After death, authors also had little control over whether their suicide letters were published. Cook failed in his publication request. His adversary, the marquis, was a wealthy and influential man and, although Cook's letter was ‘read in Court’, it was thus never printed. The marquis's attorney even contested its account, claiming that, ‘being dissatisfied with his Conduct’, the marquis had ‘discharged him…and from that and divers subsequent Occurrences his Mind was distracted…he became deranged’.Footnote 135 When letters were published in the press, the documents could also be changed and distorted – a reason for scholarly caution. In his suicide letter of 1772, Jacob Miers, who killed himself in London, wrote that he was ‘in my sences and to senceble of the Most horid Crime I am ago into Comit to’.Footnote 136 However, when this was reported by the Middlesex Journal or Universal Evening Post, it claimed that he wrote that he was ‘in my right mind and senses when I did the Deed’.Footnote 137 Not only, then, did they correct his grammatical and orthographic errors, but they somewhat altered the sense of his words. Although publication has preserved lost letters, it always changed them, giving them new form, endowing new meanings, and stripping materiality away.

Authors also had little control over the longer, archival afterlives of their letters. For letters uninvolved in inquests, chance, and the whims of descendants, were key. Atherstone's husband kept her letter and, with a pile of family papers, bequeathed it to his daughter (who later gave these papers to the Somersetshire archives). This was, as he explained to his daughter, to leave them ‘for my vindication’ at a time when ‘slander may attack my name’.Footnote 138 For Atherstone had publicly criticized her husband's conduct, and written a (lost) autobiography attacking him. In her suicide letter, Atherstone had asked her husband to keep her suicide a secret ‘from my darling Girls [her daughters]’.Footnote 139 Not only did he tell them, but he thus kept the letter as evidence of his wife's ‘insanity’, which protected him against the ‘desperate misrepresentations & sheer inventions’ which she allegedly circulated.Footnote 140 Subsequently, her husband also, however, lost control of the letter's ‘afterlife’. Today, utterly separated from the relationships of this family, we might have a different reading than that envisioned by Edwin. Atherstone's letter has been preserved in a series featuring many other familial letters: between her and a friend; Edwin and his daughter; and even Edwin and his lover, Hannah West.Footnote 141 Placed in this archival context, aligned with some stories, and separated from others long lost, this object takes on new and particular meanings.Footnote 142

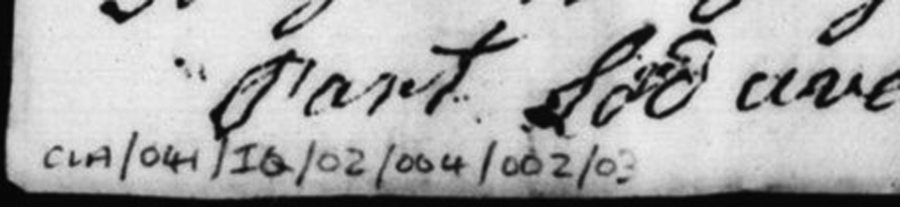

In the case of letters preserved in inquest files, they have been placed in certain material relationships not only with the legal documents concerning their author's death, but the deaths of many others. They are serialized, acquiring numbers that place them into particular institutional and bureaucratic contexts. Such chronological serialization can invite researchers to draw connections between or through different documents. In being numbered, the letters have also been altered, modern pencil encroaching upon them (see Figure 10). The ‘Table’ upon which a letter was found has been lost or disintegrated; instead, the letter is opened upon a plastic desk, put into relationships with modern technologies. Crucially, the pre-1800 letters preserved by the Westminster and City of London coroners have also been digitized by London Lives, thus taking on a new form in cyberspace.Footnote 143 Though this is in many ways positive and democratizing, and incredibly useful to this study, such digitization can work against the achievements of the ‘material turn’: ‘with digitization the archive is once again what it used to be: texts rather than physical objects’.Footnote 144 The notes are de-spatialized, and re-presented on a flat screen, where casual observers are divorced from a sense of size, colour, and tactility. For the authors, their letters were physical as well as textual objects, and it is crucial that, in an age of digitization, we remember that.Footnote 145

Figure 10. Extract from William Bull's letter, Bull, MS: CLA/041/IQ/02/004, LL ref: LMCLIC650040009. Copyright: London Metropolitan Archives, City of London.

It is also crucial that, in such an age, we respect the role and placedness of these sensitive sources. If we only see them as ‘elaborate performances’, or even as pixelated images we might casually flip through on a website, we are in danger of stripping them of their significance within real people's emotional and material lives.Footnote 146 This article has shown that suicidal people were creative and resourceful in using space and materiality in order to communicate. It has also argued that suicide notes were fundamentally epistolary documents, generally addressed to known people and engaged in specific dialogues, which also have the potential to illuminate the emotional experiences of the poor and marginalized. A suicide letter, ‘Found upon a Table’ hundreds of years ago, should never be divorced from the material, social, and emotional networks in which it was completely and utterly embedded.

Acknowledgements

I am indebted to my supervisor, Elizabeth Foyster, for her invaluable guidance and encouragement. I want also to thank Elsa Minns, Niall Dilucia, Michael Forrester, and Silvia Sbaraini for their extremely helpful suggestions. I am particularly grateful to Sophie Michell for showing and sending me her photograph of Susannah Crompton's suicide note, which she found during her Ph.D. research (‘Dynamics of death: the Victorian coroner's court, 1855–1905’, The Open University, forthcoming). I am also extremely grateful to the archivists at the Westminster Abbey Muniment Room, the Somerset Archives, Peterborough Archives, and the London Metropolitan Archives for allowing me to reproduce their items, and for the team at London Lives for allowing me to use their photographs. I also would like to offer my sincere gratitude to the two anonymous reviewers for their incredibly useful comments, and to Emma Griffin and the editorial team at the Historical Journal.

Funding Statement

Funded by The Wolfson Foundation (no grant number as it is a charity) and by an archival research grant from Clare College Cambridge.