1. Introduction

In the 30 years after the Second World War, one of the most remarkable features of politics in advanced economies was the constant expansion of the welfare state. The trend toward ever more generous and encompassing social protection came to a halt with the economic crises in the 1970s. As governments ushered in an “era of permanent austerity” (Pierson, Reference Pierson1996), the focus shifted from welfare state expansion toward cost containment and retrenchment. The concomitant structural change toward a postindustrial economy changed the economic context conditions and social policy. Rising new social risks revealed institutional frictions in a consumption-oriented welfare state built on the premise of an industrial society (Taylor-Gooby, Reference Taylor-Gooby2004; Bonoli, Reference Bonoli2007; Armingeon and Bonoli, Reference Armingeon and Bonoli2007).

In order to cope with new social risks, governments have been forced to recalibrate social policy toward a more investment-oriented welfare state by incorporating new policy instruments, such as active labor market policy (ALMP), family policies, and educational policies (Morel et al., Reference Morel, Palier and Palme2012; Hemerijck, Reference Hemerijck2013; Beramendi et al., Reference Beramendi, Häusermann, Kitschelt and Kriesi2015).Footnote 1 Extant research has demonstrated that these social investment policies are highly popular and allow for affordable credit-claiming (Ansell, Reference Ansell2010; Bonoli, Reference Bonoli2013; Busemeyer and Garritzmann, Reference Busemeyer and Garritzmann2017; Neimanns et al., Reference Neimanns, Busemeyer and Garritzmann2018). However, despite their apparent popularity, welfare state recalibration often resembles a “political uphill battle” (Hemerijck, Reference Hemerijck2018), and many countries have not fully embarked on a social investment path (Morel et al., Reference Morel, Palier and Palme2012; Bouget et al., Reference Bouget, Frazer, Marlier, Sabato and Vanhercke2015). Why is welfare state recalibration so difficult?

In times of limited resources, policymakers face tough choices about how to recalibrate the welfare state. Hard fiscal constraints combined with rising new social demands have transformed welfare state politics from a positive- to a zero-sum game (Levy, Reference Levy1999; Häusermann, Reference Häusermann2010). Governments struggle to increase spending on new social policies while maintaining traditional social protection systems. Consequently, welfare state reforms since the 1990s have often increased spending on some social policies at the cost of others (Bürgisser, Reference Bürgisser2019). As austerity became the dominant macroeconomic policy response to the Great Recession in post-crisis Europe, policymakers’ room for fiscal maneuver has been even further reduced. This has put distributive conflicts center stage, as most government social spending is highly popular among the broader public (Häusermann et al., Reference Häusermann, Pinggera, Ares and Enggist2021).

We argue that welfare state recalibration under austerity is complicated because citizens, on average, do not strongly prioritize social investment over social consumption. Existing research on support for social investment mainly studies attitudes toward individual social policies or individual policy fields and does not capture the numerous trade-offs inherent in the multidimensional recalibration of the welfare state in times of austerity. This is unrealistic because the debate among policymakers and scholars alike is not anymore about more or less welfare state spending per se but the relative importance of different social policies. We thus shift the focus from citizens’ social policy positions toward their social policy priorities, contributing to an emerging literature studying attitudes toward policy trade-offs (Busemeyer and Garritzmann, Reference Busemeyer and Garritzmann2017; Neimanns et al., Reference Neimanns, Busemeyer and Garritzmann2018; Häusermann et al., Reference Häusermann, Kurer and Traber2018; Armingeon and Bürgisser, Reference Armingeon and Bürgisser2021; Bremer and Bürgisser, Reference Bremer and Bürgisser2022; Häusermann et al., Reference Häusermann, Pinggera, Ares and Enggist2021). Unlike previous research, we move beyond a few narrow social policy trade-offs and adopt a “macro-perspective”: we ask what policy priorities citizens have regarding the multidimensional recalibration of the welfare state and study trade-offs within and across the most relevant social policy fields simultaneously.

Traditional, unidimensional survey questions only capture citizen's unconstrained policy position net of their importance. However, policy priorities result from both positions and importance, which are vitally important in times of tight budget constraints. Using novel data from two survey experiments conducted in Germany, Italy, and the United Kingdom in 2018, we study how citizens evaluate reform proposals when forced to choose between several highly popular social policies. First, we use split-sample experiments to tease out differences in citizens’ policy positions and priorities toward different social investment policies (education, active labor market policies, and childcare). Second, we use a conjoint survey experiment that simultaneously varies spending on multiple social policy areas (pensions, education, passive and active labor market policies, childcare and child benefits) to determine the public's multidimensional priorities regarding welfare state recalibration. We employ a novel method to analyze results from this conjoint experiment to shed light on how citizens evaluate and prioritize different forms of welfare state recalibration in times of austerity.

The results reveal that citizens’ policy positions and policy priorities are profoundly different. The split experiment shows that unconstrained support for social investment in three different policy areas is very high (policy position), but support drops substantially when citizens are confronted with constraining trade-offs (policy priorities). The conjoint experiment taps into multidimensional priorities and indicates that, apart from education, social investment is not a priority. More specifically, we demonstrate that narrow policy constituencies could play a crucial role in blocking welfare state recalibration. Specific social policies create their own support coalitions because citizens’ narrow self-interest shapes their social policy priorities: people react strongly to cuts in spending from which they benefit. Our findings show which policy constituencies prefer which type of welfare recalibration and how strongly they resist welfare state retrenchment in specific social policy fields. For example, retired individuals prioritize pension spending more compared to other respondents, while people with children prioritize family policies more than others. In times of limited resources, these policy constituencies divide existing political coalitions, and, therefore, there is no clear social investment coalition that pushes for welfare state recalibration.

Our findings have several important implications. Substantively, they suggest that distributive conflicts in mature welfare states have become highly fragmented and are more about the distribution and protection of resources to specific groups than general support for the welfare state. Contributing to existing research (e.g. Busemeyer and Garritzmann, Reference Busemeyer and Garritzmann2017; Häusermann et al., Reference Häusermann, Pinggera, Ares and Enggist2021), we show which groups most strongly resist welfare state recalibration, and which trade-offs are most contentious. Successful welfare state reforms need to be carefully crafted, including compensation to these policy constituencies that see their benefits at risk. Methodologically, our findings show that simple unidimensional preference questions exclusively capture an individual's policy position. They do not allow for inferences about respondents’ policy priorities toward the multidimensional nature of welfare state recalibration. Our study uses two experimental approaches to capture such priorities. In particular, we propose a new way to conduct and analyze conjoint experiments in order to shift the focus of public opinion research from positions toward priorities, and this approach could be applied to other policy fields to study salient trade-offs.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. First, we briefly review the existing literature and develop the theoretical expectations about the preferred forms of welfare state recalibration. The second part describes the two survey experiments, and the third part presents the results. The final section concludes with a discussion of the broader implications of the findings.

2. Public opinion on welfare state recalibration

2.1 From unidimensional positions to multidimensional priorities

Extant literature has shown that social policy preferences cluster along different dimensions, i.e., preferences toward social investment and social consumption are distinct (Fossati and Häusermann, Reference Fossati and Häusermann2014; Garritzmann et al., Reference Garritzmann, Busemeyer and Neimanns2018). Much like support for the welfare state in general, social consumption and social investment are highly popular (Ansell, Reference Ansell2010; Roosma et al., Reference Roosma, Gelissen and Oorschot2013; Neimanns et al., Reference Neimanns, Busemeyer and Garritzmann2018; Häusermann et al., Reference Häusermann, Pinggera, Ares and Enggist2021). This high support for social consumption and social investment is also corroborated by our survey results in Figure 1 (for more details on the survey, see the research design section). Citizens are strongly in favor of governments providing a safety net when people become ill, old, or unemployed (social consumption) but they also want governments to support people getting better education and new jobs (social investment). Neimanns et al. (Reference Neimanns, Busemeyer and Garritzmann2018) even show that social investment is far more popular than social consumption, arguing that social investment appeals to a broad coalition of well-educated middle class voters and is a valence issue.

Fig. 1. Support for social investment and social consumption. Notes: Level of (dis-)agreement to the statement that “the government should provide a safety net when people become ill, old, or unemployed” (left panel) and that “the government should support people to get better education and new jobs” (right panel).

However, despite the popularity of social investment, welfare state recalibration is politically difficult (Hemerijck, Reference Hemerijck2018). Austerity is a decisive factor why many countries have not recalibrated their welfare state toward social investment, particularly in Southern Europe (Bouget et al., Reference Bouget, Frazer, Marlier, Sabato and Vanhercke2015). Limited resources do not allow for across-the-board increases in welfare state spending and force governments to make tough choices. Due to political and economic reasons, they often cannot increase taxes or government debt to finance welfare state expansion on the scale common in the post-war period. On the one hand, government debt is seen as an illegitimate way to finance social policy spending, especially since the European sovereign debt crisis (Blyth, Reference Blyth2013; Barnes and Hicks, Reference Barnes and Hicks2018). On the other hand, governments’ ability to tax effectively has eroded over the past decades, either due to ineffective tax authorities, high capital mobility, or sophisticated tax evasion schemes (Zucman, Reference Zucman2015).

As it is almost impossible to increase social spending on all policies in times of permanent austerity (Pierson, Reference Pierson1996), research has begun to study public opinion trade-offs. Boeri et al. (Reference Boeri, Börsch-Supan and Tabellini2001) demonstrated that support for unemployment benefits and pension spending is lower once citizens learn how much they have to pay for it through higher contributions or taxes. Likewise, more recent studies indicated that support for education and family policy spending does not reach a majority when citizens are confronted with the necessity to cut pensions or unemployment benefits in exchange (Busemeyer and Garritzmann, Reference Busemeyer and Garritzmann2017; Neimanns et al., Reference Neimanns, Busemeyer and Garritzmann2018). Finally, other research has studied multidimensional trade-offs within specific social policy fields, such as pensions or labor market policy (Gallego and Marx, Reference Gallego and Marx2017; Häusermann et al., Reference Häusermann, Kurer and Traber2018). While these studies have significantly advanced our knowledge on the relevance of policy trade-offs, welfare state recalibration is a more complex and broader endeavor. We still lack coherent information on two-dimensional trade-offs across the whole range of social policy trade-offs and how they influence support levels. In addition, research studying multidimensional trade-offs has exclusively focused on single policy fields. They only allow us to gauge the relative popularity of one or two social policy areas and fall short of capturing the true multidimensional nature of welfare state recalibration. Ample research has demonstrated that welfare state reforms increasingly combine multiple policy areas simultaneously (Seeleib-Kaiser, Reference Seeleib-Kaiser2008; Häusermann, Reference Häusermann2012; Hemerijck, Reference Hemerijck2017). Therefore, we adopt a macro-perspective and study how citizens evaluate six different social policies against each other and weigh the trade-offs associated with welfare state recalibration across social policy fields.

2.2 Welfare state recalibration and the public's social policy priorities

In this paper, we focus on trade-offs between the most relevant social policies in a context of austerity: pensions, education, active and passive labor market policies, and childcare and child benefits. We argue that policymakers have to balance trade-offs across multiple social policy areas and craft reform packages that prioritize some policies over others. Are citizens ready to reduce spending on pensions to increase spending on education and childcare? Are citizens willing to pay for childcare by lowering child benefits? Do citizens prioritize labor market policies over childcare?

In principle, support for social investment is very high among the wider public. However, we expect that this broad support substantially declines when people have to evaluate trade-offs associated with welfare state recalibration. Trade-offs often occur between equally cherished policies, forcing people to weigh the benefits and costs in question carefully. The way they make this evaluation should differ across individuals (see below), but we expect the average support for social investment to drop when trade-offs are mentioned. The diffuse and broad support coalition for social investment (Neimanns et al., Reference Neimanns, Busemeyer and Garritzmann2018) might particularly easily fall apart in light of social policy trade-offs with clearly defined beneficiaries.

Hypothesis 1. Support for social investment declines and is not a priority when it entails trade-offs with other social policies.

Although we expect average support to decline drastically for all social policy fields once we introduce trade-offs, there should be differences across social policies. First, the average citizen should be more supportive of increasing spending in fields that benefit many people because they are more likely to profit from it. Conversely, the average citizen should react most sensitively to retrenchment in those fields. This involves spending on both social consumption and social investment. For example, pension spending is likely the most popular form of social spending because most people expect to retire and to receive a pension at some point. Similarly, education is a central pillar of the welfare state that directly affects many people. Labor market policies and family policies, in contrast, benefit a smaller group of recipients.Footnote 2

Apart from sheer group size, a second relevant dimension is “deservingness” perceptions. The literature shows that particular social groups are seen as more or less “deserving” of welfare state support (van Oorschot, Reference van Oorschot2006). For example, elderly people are considered most deserving because retiring is common, and they have earned their right to be supported by having worked and contributed to society. In stark contrast, the unemployed are seen as much less deserving. There is a significant stigma associated with unemployment, which is often seen as a result of one's passivity or unwillingness to find a job and a failure to contribute to society (Jensen and Petersen, Reference Jensen and Petersen2017).

Although deservingness perceptions may reflect the size of a particular welfare state constituency, they also tap into normative considerations, which help distinguishing support for groups that are equal in size. There is little literature on deservingness perceptions of families, but we assume that they are seen as more deserving than the unemployed. In contrast to retirement, having children is still a choice, albeit less stigmatized than being unemployed. Therefore, we expect that citizens have social policy priorities based on the size and the deservingness of the beneficiary group.

Hypothesis 2. Pension and education have a higher priority than family policies, which, in turn, have a higher priority than labor market policies.

These priorities should influence the extent to which support for social investment drops in two-dimensional trade-offs, but they should also influence support for multidimensional welfare state reforms. Areas that citizens prioritize involve social consumption (e.g., pension) and social investment policies (e.g., education), reducing overall support for recalibration toward a social investment welfare state.

2.3 Heterogeneous priorities: the importance of policy constituencies

The way that individuals respond to trade-offs should also vary across individuals. Citizens do not only evaluate policies based on their expected aggregate effects, but they also consider their pocketbook consequences. An extensive literature on unidimensional policy preferences has highlighted important predictors such as income, class, education, socioeconomic status, and political ideology. In particular, the literature emphasizes material self-interest (income and risks) as a primary source of preference formation (Meltzer and Richard, Reference Meltzer and Richard1981; Rehm, Reference Rehm2011). However, trade-offs involved in welfare state recalibration often occur between two equally cherished policies. Broad material self-interest may, therefore, be less relevant to explain social policy priorities in trade-off settings.

We expect that distributive conflicts in mature welfare states have become more about distributing resources to narrow groups than about support for the welfare state in general (see also, Busemeyer and Neimanns 2017; Busemeyer and Garritzmann, Reference Busemeyer and Garritzmann2017). Welfare states are multidimensional entities from which individuals benefit in various ways. Building on the policy feedback literature (e.g., Pierson 1993), we expect that specific social policies create their support coalitions, which we call policy constituencies. While policy constituencies may generally not have a higher position for policies they directly benefit from, they should have a higher priority for “their” policies. When fiscal constraints come to bite, trade-offs between different social policies are exacerbated. In this context, citizens should be primarily interested in protecting the services and benefits they directly benefit from.

Overall, specific policy constituencies should react more strongly to trade-offs that affect them (more or less) directly. Citizens thus are likely to prioritize those policies where they expect to be net beneficiaries (see also Rehm, Reference Rehm2011). In some cases, these policy constituencies are neatly defined. Having young children should make individuals more sensitive to trade-offs that involve a reduction of family policies. Similarly, labor market outsiders should have a keen interest in protecting unemployment benefits and training for the unemployed that help improve their situation directly (see also, Rueda 2007; Schwander and Häusermann 2013; Vlandas 2020). Finally, retired people should be more sensitive to changes in pension spending and less interested in trade-offs that involve policies that do not affect them anymore (e.g., family policy). In other instances, policy constituencies are fuzzy. Education benefits a large and diverse group of people, including university students, young adolescents in school or vocational training, and parents with children. Moreover, education is an investment in human capital. Its benefits are often uncertain and mainly accrue in the future. This should create a diffuse support coalition for education with only small constituency-specific effects.

Hypothesis 3. Policy constituencies prioritize policies from which they benefit more than people not benefiting from these policies.

3. Research design

We fielded a survey in three large European countries in 2018: Germany, Italy, and the United Kingdom (UK) to test our expectations. The countries represent major European economies with advanced welfare states, including different varieties of capitalism (Hall and Soskice, Reference Hall and Soskice2001) and different welfare state regimes (Esping-Andersen, Reference Esping-Andersen1990). They spend different resources on different social policies, which gives us sufficient variation to check whether individual countries drive our results. In each country, we recruited 1200 respondents from a pool of eligible voters through large online panels provided by Qualtrics. The sample was representative of all eligible voters based on gender and age.Footnote 3

To assess citizens’ multidimensional social policy priorities, we used two different survey experiments that we developed to overcome problems with conventional surveys studying one- or two-dimensional trade-offs. First, we use a split-sample experiment to measure individuals’ support for social investment given different kinds of trade-offs, allowing us to zoom into trade-offs within and across policy fields to gauge support for welfare state recalibration. Second, we use a conjoint survey experiment that simultaneously varies six forms of social spending to measure the public's macro priorities across the full range of social policies. Both experiments impose austerity to avoid “free lunches” where a respondent can support spending increases on all social policies. This permits us to assess which social policies they prioritize over others. We only focus on social policy priorities because increasing revenues through taxes or government debt are often difficult. Moreover, we want to study attitudes toward direct recalibration, i.e., shifting resources from one social policy field to another, and not indirect recalibration through welfare state expansion financed by tax or debt increases.

3.1 Split-sample experiment

To test how respondents perceive and react to salient trade-offs associated with welfare state recalibration, we confronted respondents with a series of questions that measure individuals’ support for three social investment policies. Respondents were randomly assigned to four different groups, including one control group and three treatment groups.Footnote 4

In each group, respondents evaluated three statements about spending on education, active labor market policies, and childcare. For each statement, respondents in the control group were presented with traditional, one-dimensional questions, while the treatment groups were confronted with statements that raised awareness for different two-dimensional trade-offs. Subsequently, they were asked to what extent they agree or disagree with these statements. This allows us to analyze the extent to which specific social policy trade-offs are more acceptable to respondents than others.

Table 1 shows the complete list of statements. All statements are relative to the status quo and do not quantify the specific trade-offs. This simplification allows us to run the same experiment in several countries. To reduce complexity and cognitive exhaustion for the respondents, we limited the trade-offs to those theoretically most interesting. We always included an intra-field trade-off (e.g., ALMP versus PLMP, childcare versus child benefits). Additionally, we always introduced a trade-off between pension and childcare spending because these two are among the most popular forms of consumption and investment spending. Finally, in the case of education, we also introduce a trade-off with ALMP.

Table 1. Design of the split sample experiment

3.2 Conjoint experiment

Welfare state recalibration often involves multidimensional trade-offs across several policy fields simultaneously. To study priorities in a multidimensional setting, we designed a conjoint survey experiment that focuses on social policy trade-offs across several social policy fields. Conjoint survey experiments are useful to elicit priorities because they require respondents to evaluate entire policy packages rather than individual measures (Hainmueller et al., Reference Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto2014). In our case, we evaluate the priorities that individuals attach to different social policies by forcing respondents to simultaneously make decisions based on the position and the intensity of their position toward multiple policies. Instead of asking respondents directly, we use the conjoint experiment to indirectly force respondents to reveal their social policy priorities. This allows us to capture priorities in one analysis rather than triangulating between results from different split-sample experiments jointly, as done above.

Specifically, our survey asked respondents to evaluate various reform proposals regarding changes to government spending in a set of choice tasks. Each task presented respondents with two profiles of possible welfare state reforms, and they were asked five times (i) to choose between two fiscal packages (“choice” variable) and to (ii) indicate how likely they are to support each of the packages (“rating” variable). The profiles comprised six attributes corresponding to core elements of welfare state spending, and each attribute could take on a set of discrete and pre-defined levels, representing different spending options. The profiles were then generated randomly, i.e., they contained a fixed number of attributes, which were shown to respondents in random order and with a random display of an attribute level.Footnote 5

To reduce complexity and avoid cognitive exhaustion, we had to limit the number of attributes and levels. Concretely, the reform profiles contained six attributes (as shown in Table 2), chosen to represent two different dimensions of government social spending, namely social investment and social consumption. Education, childcare services, and training for the unemployed (ALMP) are proxies for social investment spending. Pensions, child benefits, and unemployment benefits (PLMP) are proxies for social consumption spending. The profiles did not include health care because of vast country differences in healthcare funding, making comparisons difficult, and spending on health care has both an investment and consumption element.

Table 2. Attributes and levels of the conjoint experiment

We included three levels for each spending attribute (increase, decrease, no change). In a fully randomized setting, there would be 729 combinations. However, to focus on trade-offs and priorities and avoid “free lunches” where respondents can favor spending increases on all social policies, we force respondents to decide which social policies they prioritize over others. We achieve this by showing respondents only zero-sum reform proposals, i.e., we only allow combinations in which any given expenditure increase in one attribute is matched with an expenditure decrease in another attribute. This imposes austerity: it does not give respondents the option to choose expansionary reforms and makes the trade-offs inherent in welfare state recalibration under fiscal constraints explicit.

Respondents may disagree with these restrictions. Some respondents may want to increase spending on all social policies, while others may want to decrease spending on all of them. However, the zero-sum reform proposals allow us to tease out respondents’ policy priorities on welfare state recalibration in times of austerity, when a (more or less) budget-neutral reform is politically most likely.Footnote 6 Consequently, we exclude 588 combinations and are left with 141 possible combinations. Importantly, the likelihood that a given level appears in combination with another level is still the same as if there were no restrictions because logical inconsistencies were uniformly deleted. This crucial feature of our design stems from the fact that each attribute includes three symmetrical levels across all attributes (increase, decrease, no change). Each package is randomly created within this subset of consistent packages and has the same likelihood to occur.

We calculate two main variables of interest from the conjoint experiment. First, we identify the causal effect of individual attribute levels on the support for the entire policy package compared to the baseline attribute level. To this end, we estimate the average marginal component effect (AMCE) of a change in the value of one of the six dimensions on the probability that the respondent chooses the reform proposal. This “choice” variable is binary: 1 if a reform proposal is chosen and 0 if not chosen. We estimate the AMCEs using linear probability models and regress the dependent variable on dummy variables for level (where the status quo is the baseline for each dummy). The ACME incorporates both the position and the importance that individuals assign to each attribute level (Bansak et al., Reference Bansak, Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto2020) and, therefore, captures what we conceptually understand as policy priorities. Second, we follow Leeper et al. (Reference Leeper, Hobolt and Tilley2020) and measure subgroup differences by calculating recommendations by calculating conditional marginal means for all levels of our attributes. Marginal means measure how favorable respondents are to a given feature of our reform package, which allows us to analyze differences across policy and party constituencies.

To estimate the AMCEs and marginal means, we use Ridge regression. Standard conjoint experiments have dimensions that are independent and fully randomized. Spending trade-offs are not independent by design: under austerity, increasing expenditure on one policy requires decreasing expenditure on another policy. Therefore, each attribute's value depends on the other attributes to ensure a fully balanced reform. To account for these dependencies, we use a novel approach that uses ridge regression. Ridge regression is a standard regularization method that Hoerl and Kennard (Reference Hoerl and Kennard1970) proposed to address design-based super collinearity and that Horiuchi et al. (Reference Horiuchi, Smith and Yamamoto2018) also used for conjoint analysis. To estimate the AMCEs, we use the R package glmnet, and we rely on bootstrapping to calculate non-parametric confidence intervals. This approach allows us to make inferences about the effect of an attribute changing from one value to another, averaging over the randomization distribution of our 141 profiles. We explain the method and rationale further in Appendix D. Moreover, we discuss several robustness tests at the end of the results section, which did not change the results.

4. Results

4.1 Two-dimensional priorities of welfare state recalibration

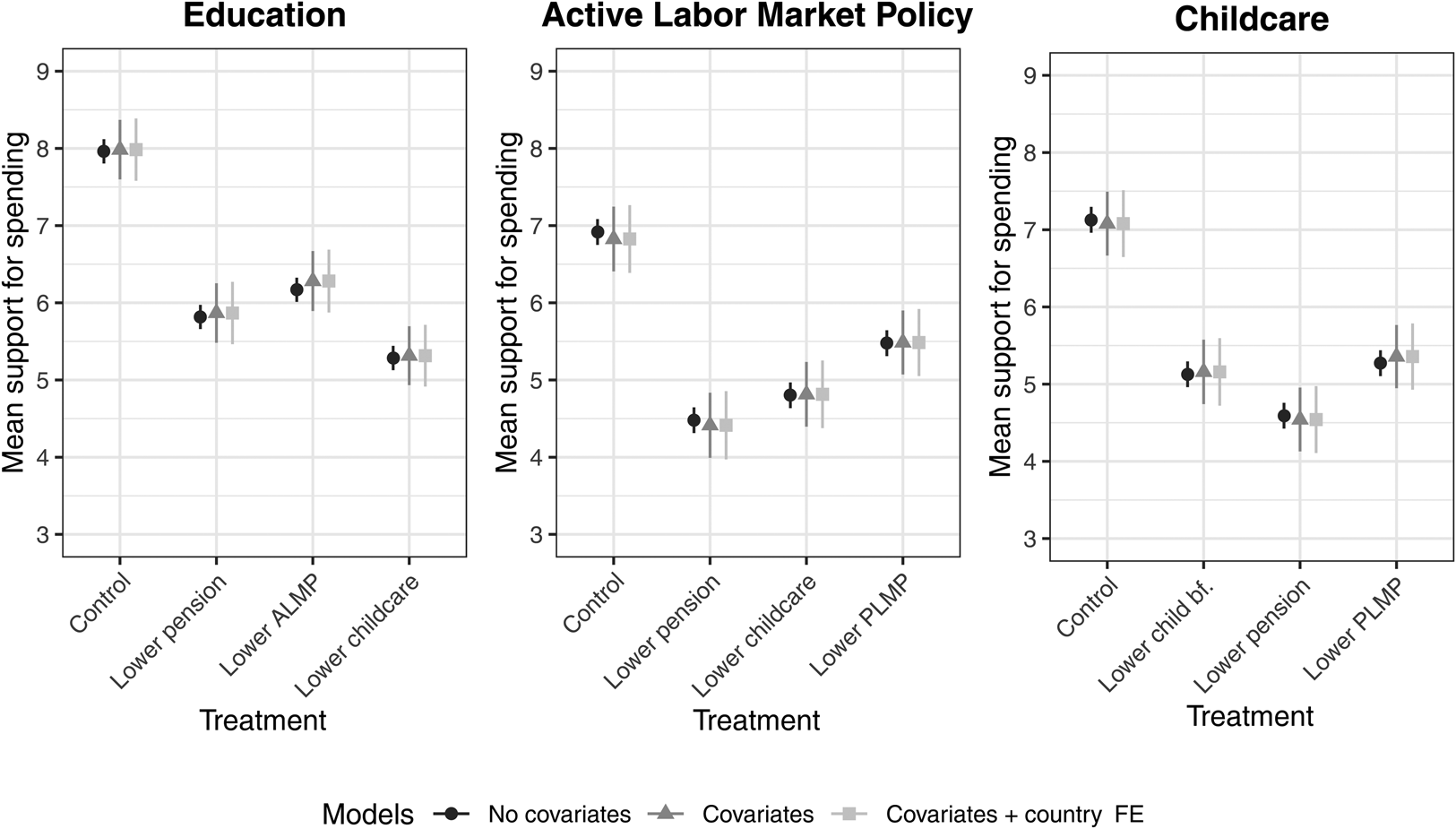

To study how respondents react to specific trade-offs, we use results from the split-sample experiment. We first graphically present the predicted mean support (on a scale from 0 to 10) and 95 percent confidence intervals based on OLS regressions. Figure 2 shows the predicted support for spending increases in three social policy fields without a trade-off (control group) and with three different trade-offs (treatment groups). To test the robustness of our findings, we control for several covariates (e.g., age, sex, occupational classes, income, education, employment status, partisanship, parents with children) and include country-fixed effects.

Fig. 2. Average support for spending increases by treatment and model, pooled. Notes: Predicted mean support and 95 percent confidence intervals based on OLS regressions. The dependent variable is scaled from 0 to 10. Covariates are age, gender, education, occupation, work contract, partisanship, and having young children.

In line with Figure 1, the results show high levels of support for social investment policies in an unconstrained setting. However, it is implausible that governments do not face any fiscal constraints and can increase spending on all social policies. Therefore, we forced respondents to make a distributional choice between similarly cherished social policies. Overall, and in line with existing research on trade-offs (Busemeyer and Garritzmann, Reference Busemeyer and Garritzmann2017; Neimanns et al., Reference Neimanns, Busemeyer and Garritzmann2018; Häusermann et al., Reference Häusermann, Pinggera, Ares and Enggist2021), our results indicate that the widespread support for social investment tumbles once we introduce trade-offs. These treatment effects are large and significant for all three policy fields. Moreover, the results are robust to the inclusion of covariates and country-fixed effects.

To estimate the share of respondents who support spending increases, we transform the 0–10 response scale into a binary variable. Responses from six to ten are counted as agreement, while responses from zero to five are counted as disagreement/neutral. Education is the most popular social investment policy. The average level of support for education is about 8.0, implying that around 88 percent of the respondents agree that the government should increase spending on education. ALMP and childcare enjoy slightly lower but still widespread support with mean support levels of 6.9 (73 percent) and 7.1 (75 percent), respectively.

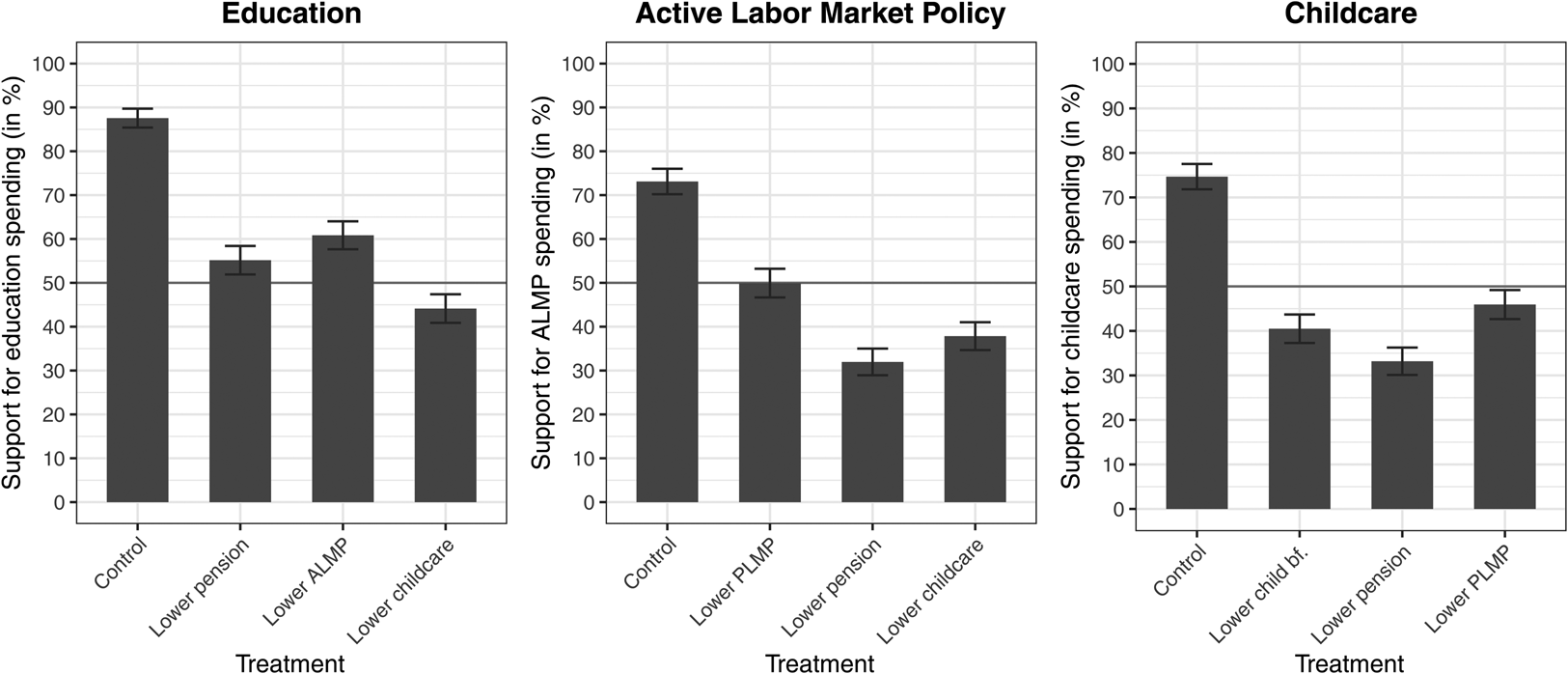

The share of supporters for all social policies drops substantially when trade-offs are introduced, but Figure 3 shows some interesting variations across social policies. First, higher education spending remains relatively popular even when trade-offs are acknowledged. A majority of 61 percent supports education spending if it implies cuts to ALMP. Cuts to childcare are the least popular, with only 44 percent supporting higher education spending. Remarkably, still 55 percent support an expansion if it implies pension cuts. This contrasts with results from (Busemeyer and Garritzmann, Reference Busemeyer and Garritzmann2017), who show that an expansion of education at the cost of pension spending finds no majority support.

Fig. 3. Shareof supporters for spending increases by treatment. Notes: Predicted share of respondents supporting spending increases and 95 percent confidence intervals. The dependent variable (0–10) is transformed into a binary variable (6–10 are counted as support; 0–5 as opposition/neutral).

Second, ALMP spending has a lower priority than education spending, given that support falls more when trade-offs are introduced. However, almost a majority of respondents support higher ALMP spending at the cost of lower PLMP spending, indicating the possibility of recalibrating labor market policy toward activation. Support for ALMP is lower and does not generate a majority when it implies pension cuts (32 percent), the most significant area of social consumption spending, or lower childcare spending (38 percent).

Finally, welfare state recalibration toward childcare does not find a majority, either. The most significant drop in the share of supporters occurs when it implies lower pension spending, indicating that the average citizen is more concerned about protecting pension benefits than helping young families. Contrary to labor market policies, there is no support for an “activation turn” within family policies. Only a minority of respondents (40 percent) are willing to increase childcare spending at the cost of lower child benefits. Interestingly, only 46 percent of respondents support an expansion of childcare when this comes at the costs of unemployment benefits, which is usually a relatively unpopular form of spending.

Overall, the results show that welfare state recalibration is an uphill battle in times of limited resources. In principle, support for education, ALMP, and childcare spending is high, but they are not clear policy priorities in a two-dimensional trade-off setting. Politically, increases in education spending are the most viable. Moreover, a recalibration within some policy fields (from PLMP to ALMP) could be possible but likely contentious. A more pronounced social investment turn by spending fewer resources on pensions is certainly the least preferred and politically most difficult avenue of welfare state recalibration.

4.2 Multidimensional priorities of welfare state recalibration

The results from the split experiment suggest that welfare state recalibration toward social investment is not a priority. However, welfare state reforms often impact several policy fields at the same time. We thus turn toward the conjoint experiment to account for this multidimensionality. Figure 4 shows the AMCEs of increasing or decreasing spending items relative to the baseline (“no change”) on the probability (expressed in percentage points) that a given reform package is supported. The results indicate that the average respondent has clear priorities when confronted with trade-offs across all social policy fields.

Fig. 4. AMCEs from the conjoint survey experiment. Notes: Average component-specific marginal effects (ACMEs) of a change in the value of one dimension on the probability to choose the reform package (“choice” variable).

First, spending on education and pensions is highly popular among the average citizen, even in the context of austerity. Additional pension spending increases the probability that respondents support the overall package by almost five percentage points compared to the status quo, while lower pension spending decreases the overall probability of support by more than seven percentage points. Education spending is only slightly less important to respondents. Lower education spending reduces support by almost four percentage points, whereas additional spending on education increases the support by a similar amount.

Second, spending on labor market policies is not a priority in the context of austerity and sharp trade-offs. Given that expansionary reforms are impossible, respondents do not favor increasing spending on labor market policies, which would necessitate cuts in other areas. In particular, citizens react negatively to increasing spending on PLMP, which reduces support by around seven percentage points. ALMP spending is less unpopular, but it still reduces the support for a given reform proposal by 2.5 percentage points. Interestingly, the pattern reverses when it comes to decreasing spending on labor market policies. Lower ALMP spending increases support, whereas lower PLMP spending does not affect support. In sum, spending on the unemployed has a low priority for the average citizen. The average respondent is less supportive of reducing spending on ALMP than PLMP, but they certainly do not want to increase ALMP spending, either. Hence, the unemployed are likely viewed as less deserving than other social groups that benefit from the welfare state.

Third, family policies have a relatively small influence on the probability that respondents support a given package. On average, respondents oppose increasing spending increases on child benefits, while decreasing these benefits does not affect overall support. Surprisingly, neither an increase nor decrease in childcare affects overall support, indicating that they do not matter for evaluating policy packages. The average respondent seems ambivalent about family policies, except that increasing child benefits negatively influences reform support.

Overall, the results are consistent with the findings from the split-sample experiment. They suggest that citizens have clear social policy priorities in the context of austerity. First, they care most about broad policies that many respondents benefit from and thus attach a high priority to pension and education spending. Second, labor market policies enjoy only a low priority among citizens, as evidenced by the adverse effects of higher spending on such policies. The average citizen is especially opposed to higher PLMP spending. Third, the small to non-existent effects of family policies indicate that citizens attach a medium priority to family policies. They are more popular than labor market policies but less popular than pensions and education.

4.3 Relative priorities across policy constituencies

Welfare state politics is often influenced by small groups who benefit from specific policies. As theorized above, there are reasons to believe that the support for different social policies varies across policy constituencies due to narrow self-interest. To operationalize these policy constituencies, we identify the people most likely to benefit from specific social policies. We define the retired as the main policy-constituency for pensions, students and people with children for education, the labor market outsiders for both types of labor market policy, and people with young children for both types of family policy. We infer these characteristics from a battery of socio-demographic questions asked in the survey, and the operationalization of all independent variables is detailed in Appendix A.

Following our theoretical expectations, we calculate the marginal means for the policy constituencies compared to everyone else. Table 3 shows the marginal means for each dimension for the constituency and the non-constituency, the difference between the two, and whether this difference is statistically significant. The results show that specific policy constituencies react more sensitively to changes that involve specific policies from which they benefit directly. They are more likely to support additional social spending than the average citizen when existing policies benefit them directly, and they are more likely to withdraw support if the reform involves cuts in “their” policies.

Table 3. Estimated marginal means of policy constituencies versus non-constituencies

Note: * ${\rm p}< 0.05$![]() ; constituencies are the retired for pension, the people in education and with children for education, the outsiders for PLMP and ALMP, and having young children for child benefits and childcare.

; constituencies are the retired for pension, the people in education and with children for education, the outsiders for PLMP and ALMP, and having young children for child benefits and childcare.

First, the marginal mean of increasing pension spending is 0.094 higher for retired respondents than non-retired. In other words, retired people have a 9.4 percentage point higher probability of supporting the reform if it includes an increase in pension spending than people who are not retired. Similarly, when a reform decreases pension spending, retired people have a 10.5 percentage point lower probability of support than non-retired people. These differences are statistically significant and substantial. Retired people will strongly oppose any cuts in pension spending. Going beyond the table, Figure 5 shows the marginal means for a selection of other conjoint attributes. Due to their higher support for pensions, it indicates that the retired are more likely to prioritize cuts in unemployment benefits than non-retired people when forced to make a choice.

Fig. 5. Estimated marginal means of policy constituencies versus non-constituencies. Notes: Estimated marginal means for the policy constituency versus non-constituency (conjoint “choice” variable). For each graph, only a selected number of dimensions are shown. The complete graphs are included in Appendix G.

Second, the constituency effects for education are smaller than for pensions. For education, the policy constituency has a one percentage point higher probability of supporting the reform if it includes an increase in education spending than the non-constituency. In comparison, it has a 1.6 percentage point lower probability of supporting it if it includes a decrease. Since the constituency benefiting from education is relatively diffuse and people who previously benefited from education (e.g., people with a university degree) likely remain supportive of it, it is not surprising that the heterogeneous effects are smaller than for pension spending. Interestingly, however, the policy constituency for education is much less likely to support pension spending increases.

Third, there are substantial differences between labor market outsiders and the rest of the population if the reform proposal increases or decreases PLMP spending. The non-constituency is firmly against an increase, whereas outsiders are much less opposed. Similarly, the non-constituency is much more favorable toward reforms that reduce unemployment benefits than outsiders. We find similar effects for decreasing ALMP spending, but there is no difference in support for increasing ALMP spending. Hence, outsiders are not more favorable toward activation reforms, because they associate them with strict conditionality and workfare policies (Fossati, Reference Fossati2018) or because a diffuse cross-class coalition of employers and the middle classes equally supports activation (Bonoli, Reference Bonoli2013; Schwander, Reference Schwander2020). Outsiders are also much less supportive of increases in pension spending than insiders. They are less likely to receive a secure pension and thus less likely to prioritize such spending.

Finally, people with young children are more supportive of additional spending on childcare and child benefits than all the other respondents. The marginal mean is 0.049 and 0.031, respectively, higher for people with young children than those without. This implies that they have a 4.9 and 3.1 percentage point higher probability of supporting childcare and child benefits, respectively. In contrast, when the reform package includes cutbacks in child benefits or childcare, they are less favorable toward such reforms than people without children. Much like the other narrow constituencies, people with children are concerned about their narrow self-interest when evaluating reforms in times of austerity. They, too, are less supportive of pension spending, but like all other policy constituencies, they are still unwilling to support cuts in pension spending.

Overall, our findings suggest that narrow self-interest strongly influences support for welfare state recalibration.Footnote 7 Policy constituencies strongly support the policies they benefit from. Even policy constituencies that benefit from education spending, ALMP, and childcare are still not more likely to support a reduction in social consumption. In particular, the reluctance to reduce pensions is prevalent across all constituencies, making welfare state recalibration toward social investment in times of austerity unlikely.

5. Robustness checks

Some concerns could be levied against our survey experiments. First, to ensure the validity of our sample, we included attention check and speeding checks, which automatically screened out respondents who paid no attention or sped through the survey (see Appendix B). Second, we used quota sampling based on age and sex, but we also checked that our sample is relatively representative of income and partisanship. Third, we matched the population's demographic characteristics in each country as closely as possible using entropy balancing (Hainmueller, Reference Hainmueller2012), and the results remain substantively the same (Appendix F).

So far, we have exclusively shown pooled results from three different countries. In Appendix E, we show that the general results hold across the three countries. Support for social investment spending declines in all three countries when it entails trade-offs, and priorities are similar in all three countries. Still, there are some minor differences. First, decreasing education spending is less popular in the UK than in the other two countries, while increasing education spending is most popular in Germany. Second, pension spending is relatively more important to respondents in Italy than in the other two countries. In turn, Italian respondents are much less opposed to increasing PLMP spending than respondents in Germany and the UK, while Germans are considerably more opposed to increasing ALMP spending than respondents in the other two countries. Finally, the UK is the only country strongly opposed to increasing child benefits, while family policy has no effect in Italy and Germany.

We also used a set of tests to confirm that the results from the conjoint experiment are robust. First, we conducted a pretest with an opt-in sample from Prolific to analyze whether respondents were cognitively able to process a more complex conjoint task (eight attributes and more specific attribute levels). The results suggested that the design was slightly too complicated and that respondents preferred a simpler design. We simplified the task, which fared well in cognitive pretests. The number of attributes and levels is now well beyond the number where satisficing is a problem (Bansak et al., Reference Bansak, Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto2021). Second, we replicated our conjoint analyses using the “rating” variable instead of the “choice” variable (see Appendix G). Third, we conducted several standard robustness tests in Appendix H (carryover effects, profile order effects, screen size, speeding, choice task round). The tests indicate that the results shown above are robust.

6. Conclusion

Our analysis provides a partial answer to why welfare state recalibration is politically difficult despite the apparent popularity of social investment. Governments have little room for maneuver in times of austerity and find it impossible to cover all social risks equally. Consequently, they face substantial trade-offs when they have to design welfare state reforms that increase spending on some social policies at the expense of others.

While support for all social policies declines sharply when we account for such trade-offs, citizens have clear social policy priorities regarding welfare state recalibration. The split experiment shows that increases in education spending are more popular than increases in childcare spending and ALMP. The latter fail to reach majority support when trade-offs are involved. In particular, decreases in pension spending are politically difficult. According to our results, no trade-off that involves pension spending finds majority support.

The conjoint experiment provides for the first time evidence on citizen's multidimensional social policy priorities. We show that citizens attach a high priority to pensions and education. In contrast, childcare and child benefits only have a minor influence on the probability that respondents support a given reform, implying that they are of medium priority to citizens. Finally, active and passive labor market policies are unpopular in the context of austerity. When forced to choose, the average citizen does not support additional spending on the unemployed if this comes at the cost of lower spending in other areas. Citizens thus attach a low priority to labor market policies.

Overall, we demonstrate that multidimensional welfare state recalibration toward social investment is an uphill battle because citizens do not strongly prioritize social investment over social consumption. Moreover, strong policy constituencies are likely to block many welfare state recalibration attempts, given that citizens react sensitively to changes in policies from which they directly benefit: Pensioners care more about increasing pension spending than working-age people, parents with young children prioritize family policies more strongly, and outsiders attach a greater priority to labor market policies. Therefore, the narrow self-interest of policy constituencies is a strong predictor of their social policy priorities and likely of their political behavior.

There are several important implications of our findings. From a methodological perspective, regular opinion polls consistently overstate the support for policies if respondents do not face the inherent policy trade-offs. We argue that such questions do not allow inferences about respondents’ priorities toward welfare state recalibration. Our paper proposed two experimental strategies to present respondents with realistic trade-offs, which can easily be applied to other policy fields. Furthermore, our results show that the support structure for social investment and social consumption policies varies between and within these respective domains. Thus, it is not enough to use education and pensions as proxies for social investment and consumption, making it crucial to add more nuance to the literature on public opinion towardwelfare state recalibration.

Substantively, our findings show that governments aiming for a social investment turn need to design welfare state reforms carefully. Political conflicts in mature welfare states are more about distributing resources to specific groups than about general support for the welfare state. Especially in times of austerity, welfare state recalibration creates winners and losers. The latter need to be compensated for welfare state reforms to gain political support. A key question for future research is how policy constituencies can be convinced to give up some privileges and support policies that address new social risks. In all likelihood, policymakers confronted with such electoral constraints need to combine material incentives with solidaristic appeals. However, there is also some evidence that governments may be able to generate support for welfare state retrenchment by controlling the political messaging: By framing cuts as fiscally necessary, political actors can sometimes avoid electoral punishment (Barnes and Hicks, Reference Barnes and Hicks2018; Bisgaard and Slothuus, Reference Bisgaard and Slothuus2018). Future research should study how policymakers can use elite cues to make welfare state recalibration politically feasible despite the salient trade-offs emphasized here.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2021.78.

To obtain replication material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/7ERIFH

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge funding from the ERC Project “Political Conflict in Europe in the Shadow of the Great Recession” (Project ID: 338875). Previous versions of this paper were presented at the European University Institute, the annual conference of the Midwest Political Science Association, 2018, the annual conference of the Swiss Political Science Association, 2018, and the annual conference of the Council of European Studies, 2019. We are very grateful for insightful comments and feedback from Giuliano Bonoli, Marius Busemeyer, Julian Garritzmann, Jane Gingrich, Anton Hemerijck, Hanspeter Kriesi, Jason Jordan, and Elias Naumann. Two anonymous reviewers and the editors of the PSRM further helped to improve the manuscript. The usual disclaimers apply.