Introduction

On its own, the explosion of a political corruption scandal is no novelty. Novelty only arises when high-level politicians are investigated, charges laid, trials take place, and judges hand down hard sentences. It reaches new heights when the convicted come from the party wielding power, the same party that holds a coalition majority in Congress and is responsible for the appointment of the heads of investigating and prosecuting agencies as well as approximately 80 per cent of the deciding court's judges. Place this extraordinary scandal-cum-conviction in a developing country burdened by legacies of corruption and impunity and you have one of the most striking political corruption trials in recent history and a very rare democratic event indeed.

Criminal case 470, popularly known as the Mensalão (literally, ‘big monthly payment’), shocked Brazilians and surprised the international community. Over two dozen officials, including high-level politicians, public administrators and businessmen, received prison sentences and six-figure fines for a money-laundering-cum-legislative-vote-buying operation. The media, Congress and audit institutions investigated; the federal public prosecutor's office (Ministério Público Federal) prosecuted and the Supreme Court handed down stiff sentences. Brazil accomplished what few democracies have managed to do: guarantee procedural justice and ex post enforcement, independent of partisan power dynamics.

This article examines the Mensalão trial, its uniqueness and implications. The case raises three interconnected questions, namely, (a) what is its distinctiveness? (b) does its relative success evince a departure in the treatment of corruption cases in Brazil? And, if so, (c) what are the implications of this departure? This article provides answers to these three questions, and responds in a resoundingly affirmative manner to the idea that the Mensalão is both distinct and a departure from the status quo.

The article is divided into three different sections. The aim of the first section is to recount the story of the Mensalão, a trial with so many twists and turns it seemed to have lost even expert observers of Brazilian politics. We provide political context and examine the Mensalão from scandal, to criminal case, convictions, appeals, sentencing, and closure.

The second section considers why the Mensalão succeeded where so many other previous instances of high-level corruption have come of naught. Contrary to those who look askance and treat the Mensalão as an ideological, media-driven anomaly, we argue that the case's relative successes were not media-driven but rather crime-driven. It was the crime of buying legislation through payoffs to citizen representatives, a crime whose gravity is readily understood by citizens, that drove an overwhelming institutional response and corresponding media coverage. Congressional investigations could not be quashed, and investigations by a phalanx of accountability institutions followed by a sensational trial led to persistent media coverage. In other words, it was institutional responses to a vivid and egregious crime, and to the Mensalão's continuous cascade of sub-scandals, that generated unyielding media coverage, not a right-leaning media or justice system.

The third section analyses the implications of the Mensalão trial. Overall, we argue that the Mensalão is a signpost of institutional learning and growing democratic maturity. A significant victory over high-level impunity, we detail how the trial itself created distinct legal and jurisprudential advances for the prosecution of high-level corruption cases in Brazil. Some of these advances have been decisive in the successful (and as of this writing, ongoing) prosecution of the Petrolão scandal, which revolves around years of corrupt contracts at the state oil company, Petrobrás.

In short, the experience of the Mensalão serves to buttress the findings of a growing body of literature, that ‘accretive’ improvements to Brazil's accountability and transparency institutions are beginning to pay dividends.Footnote 1 As Praça and Taylor observe, these changes have occurred primarily ‘at the margins’, but have cumulatively had an important impact on institutional dispositions towards corruption and impunity. Growing maturity is what we would hope to expect from a nation whose principal accountability institutions, such as the public prosecutor's office (Ministério Público) and independent audit courts (Tribunais de Contas), only came into being in 1988.

In sum, the article raises the question of whether Brazil is, more than a quarter of a century after the country implemented a new constitution, entering into a stronger, more enduring relationship with the rule of law.

It is clear that this question may seem impertinent in the face of subsequent corruption scandals and recent protests in Brazil. As of this writing, the Petrolão scandal shows that corruption is just as common as ever, a claim we do not dispute in this article. We do, however, contend that state institutions in Brazil are becoming more willing and better equipped to reveal, investigate and prosecute corruption. As during the 2013 protests, when citizens contested spending for mega-events, the poor provision of basic social services and police abuses, these protests speak more about state-society interactions and the quality of public services than about ‘controlling the state’, particularly high-level impunity, which is our focus here.

Despite the legitimate concerns surrounding social policy and corruption in Brazil, a significant number of policy-related works published over the last few years suggest that Brazil's relationship with the rule of law is indeed prospering. Scholars have pointed to ‘autocatalytic incrementalism’ in the strengthening of the country's accountability institutions.Footnote 2 Others have argued that checks on presidential power imposed through vigorous electoral competition and institutional constraints have fostered Brazil's relative stability and institutional continuity.Footnote 3 Still others have argued that Brazil's fragmented multiparty system has provided incentives to expand and strengthen transparency mechanisms.Footnote 4 Even policy-based research has cast light on the surprising success of well-implemented social policies that, theoretically, should have served as fodder for clientelistic networks.Footnote 5 This article builds on this cautiously optimistic literature through an inductive analysis of Brazil's greatest corruption scandal to date.

The Scandal and Trial of the Mensalão

After winning the presidency on his fourth consecutive attempt, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva came to power in 2003 lacking a parliamentary partisan majority. The Workers’ Party (Partido dos Trabalhadores, PT) held less than 20 per cent of seats in Congress. Come his second year, however, Lula had managed to assemble a broad, ideologically heterogeneous base of support among 12 parties.

This support came with steep costs. Leading members of Lula's factionalised PT had clamoured for power upon assuming office, occupying cabinet posts and positions that, theoretically, should have been apportioned among a large, ideologically heterogeneous coalition of allied parties.Footnote 6 Lula over-rewarded the PT with cabinet and bureaucratic posts in order to entice hardliners to vote for pension and tax reforms.

Given this broad ideological diversity, the need to cement coalitional support through cabinet appointments and patronage became critical. Yet, over-rewarding the PT had deprived President Lula of these political currencies. In their stead, the government ostensibly deemed cash payments, approximately US$ 12,000 per month to members of the coalition, the most expeditious means of guaranteeing that bills survived the legislative process intact. In sum, the Mensalão resulted from a disproportionate cabinet that unduly privileged the PT and a heterogeneous, oversized coalition that demanded more resources than the government was legally able to provide.Footnote 7

Revelations of the Mensalão scheme broke in May 2005. It was a disgruntled deputy in the lower house, Roberto Jefferson of the Partido Trabalhista Brasileiro (PTB), abandoned as an ally of the PT because of his involvement in a kickback scheme with the National Mail Service, who affirmed the existence of what he termed a ‘Mensalão’. It appears that the PT never thought Jefferson's threats of revealing a legislative vote-buying scheme would be credible.

The public was not just impressed by the illegality of the Mensalão or the exorbitant payments, hundreds of times the average monthly salary paid to Brazilian workers (approximately US$ 350 dollars per month at the time), but also the sprawling reach of the scheme and the fact that the PT, which for years had staked its electability on ethics and transparency, was at the centre of allegations. Jefferson described an elaborate congressional vote-buying scheme in which officials laundered fake loans from state-owned banks through publicity agencies to then buy the votes of legislators. The PT's defence was that the money was simply caixa dois, literally, an ‘unofficial cash till’, which is Brazilian vernacular for common under-the-table electoral accounting practices, but nonetheless illegal.

In the wake of revelations, President Lula's most powerful minister, Chief-of-Staff José Dirceu, resigned. Congress then revoked the parliamentary seats of Dirceu, and federal deputies Jefferson and Pedro Corrêa, among other officials involved in the scandal. With a presidential election on the horizon in 2006, the opposition leveraged the scandal to keep it in the headlines. No campaign emerged in favour of impeachment; Lula was still highly popular and it appeared that the opposition hoped instead for ‘death by a thousand cuts’.

Mustering the votes of both opposition legislators and angry members of the government's majority base, a congressional inquiry began one month after the initial revelations in June 2005. Media coverage was intense. The government made several attempts to quash the investigation in Congress and, even though the president and rapporteur of the inquiry commission were part of the president's majority coalition, the investigation nonetheless prospered with the support of both the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate.

Numerous agencies assisted legislators in their investigations, including the Brazilian audit court (Tribunal de Contas da União), and multiple agencies whose highest authorities were directly appointed by the president, such as the federal police (Polícia Federal), the federal public prosecutor's office (Ministério Público), the federal revenue service (Receita Federal), the central bank, and the Bank of Brazil. The congressional committee responsible for investigations also hired forensic accountants to hunt-down illicit streams of money. A year after the scandal had broken and despite the dominant position of the government coalition, Congress issued a final report affirming the existence of the Mensalão and implicating scores of public and private officials.

In April 2006 Congress officially handed over investigations to the federal public prosecutor's office, which recommended indictment. Lula was not formally accused. Even if evidence had existed, implicating a popular president was both legally and reputationally risky for the public prosecutor's office, especially given that most evidence was circumstantial. Charges against José Dirceu, Lula's chief-of-staff and arguably the second most powerful person in Brazil at the time, might be viewed as implying a certain amount of guilt-by-association, damage enough for any president.

Prosecutors worked hand-in-hand with the recently reformed and professionalised federal police in order to organise evidence for trial, and even before Congress had formalised its final report, the public prosecutor's office had brought its case before the Supreme Court in March 2006, asking (unsuccessfully) for the preventive detention of 14 suspects, including Dirceu and several of the PT's most venerated leaders. Lax traditions of habeas corpus in BrazilFootnote 8 ensured that suspects remained free until the case had been decided.

Despite the swirling scandal, Lula won a second presidential term later that year. The victory was not altogether surprising. As Lúcio Rennó explains, voters punished Lula in the first round of voting, forcing a run-off, and the PT lost seats.Footnote 9 But voters ‘came home’ to support the president in the second round. Not only did the alternative opposition candidate appear to be too ideologically distant from voter preferences, but as Wendy Hunter and Timothy Power have shown, Lula's social programmes, especially Bolsa Família, a conditional cash transfer programme, helped the incumbent president carry the day among the more populous lower-income strata.Footnote 10

The Supreme Court began proceedings against 40 defendants in August 2007. Evidence gathered by investigatory agencies along with witness testimonies resulted in 69,000 pages (147 volumes) to be analysed. The size of the case owed itself not only to the scope of the Mensalão, which implicated over three dozen public and private officials, but also to the fact that the constitution provides for special standing (foro privilegiado) for high-level officials.Footnote 11 Special standing grants officials a greater number of witnesses and numerous opportunities for clarification and appeal, all of which tend to extend proceedings. Some believed that the defendants would benefit from Brazil's relatively short statutes of limitations and that the trial would ‘end in pizza’, the general tendency of corruption investigations in Brazil to end in a cordial consensus to do nothing.

But abetted by the gravity of the case and media attention, prosecution gradually inched forward. Indeed, the Mensalão seemed to stoke a flurry of accountability-enhancing initiatives inside and outside government. The most celebrated of these was the 2010 Clean Slate Law (Ficha Limpa), which ultimately outlawed the election of politicians with criminal records. Signed by 1.3 million citizens, the Ficha Limpa law was a citizen-born ‘popular initiative’ that became statute despite the resistance of many powerful politicians. A freedom of information law, originally promised by President Lula da Silva one year after the Mensalão, also made its way through Congress from 2009 to 2011.Footnote 12

The Ficha Limpa indicated that there was a clear popular thirst for greater accountability in government. Yet countervailing those who sought punishment for the mensaleiros was a small group of naysayers, led by Brazil's stratospherically popular president, Lula da Silva. Lula dismissed the criminal case as a fiction and a political witch-hunt. His actions indicated, however, that he nonetheless had much to lose from its due prosecution. During the run-up to the most decisive part of the trial in early 2012, Lula paid visits to at least five of the 11 Supreme Court justices, all of whom had been appointed during the president's two terms.Footnote 13 Lula's visits to Supreme Court justices nevertheless backfired. News of the encounters appeared in the media, and Supreme Court Justice Gilmar Mendes revealed that Lula had even used blackmail, threatening to air questionable expenses the justice had incurred on a trip to Germany earlier that year.

Yet even though Lula's efforts came of naught, legacies of impunity and the PT's hold on government seemed to weigh against the Mensalão trial. It is certainly clear that Brazilians expected little in the way of justice. As charges were being read prior to judgment, a survey by Data Folha showed that 73 per cent of Brazilians thought the mensaleiros should go to prison, but only 11 per cent believed they would be punished.Footnote 14 Lengthy proceedings had suggested as much. The trial started more than seven years after initial revelations of the Mensalão, in August 2012.

Despite the delay and popular expectations of sham justice, the Supreme Court handed down harsh verdicts in December 2012, less than half a year after the actual trial had begun. Televised and widely watched, the trial highlighted the confrontations of two Supreme Court justices, Joaquim Barbosa and Ricardo Lewandowski, who took opposite sides on virtually every decision. Barbosa, the trial's ‘reporting justice’, responsible for reviewing the evidence and confirming charges, was the Supreme Court's first and only black justice. Barbosa rose from humble origins to spend his career defending ‘fundamental rights’ as a prosecutor in the office of Brazil's powerful public prosecutor's office. Lewandowski was the trial's ‘revising justice’, responsible for assessing the pre-trial decisions of Barbosa. In contrast to his colleague, Lewandowski had spent most of his professional career as a judge in wealthy São Paulo state. The vituperative exchanges between these two justices on the floor of the court, which were aired regularly on nightly newscasts, proved a distinctive feature of the case. These exchanges evoked two sides of Brazil: one in which privilege had always defended its own kind, the other, a marginalised Brazil hungry for justice and an end to impunity. Barbosa quickly rose to prominence, gaining pop-star status for his righteousness, candour and unorthodox interpretations of the law.

When Barbosa's camp prevailed, 25 of the original 40 defendants were found guilty. These included President Lula's most trusted minister, José Dirceu, as well as the former director of the state-controlled Bank of Brazil, three directors from Brazil's Rural Bank, 13 legislators, and eight private intermediaries. In all, prison sentences for the mensaleiros totalled 283 years and Reais$ 22 million (about US$ 10 million dollars at the time).Footnote 15 The scale of sentences is surely one of the most distinctive features of the Mensalão. Lula was implicated by the Mensalão's principal money-launderer and financier, Marcos Valério, and seemingly unfulfilled promises were made to investigate.

Surprisingly, guilty verdicts appeared to have hardly caused a stir of optimism; scepticism remained as to whether convictions would lead to real punishment. Signs were not promising. At the end of the trial, in December 2012, the Supreme Court ordered the immediate repeal of indicted legislators’ mandates, as per Article 55 of the 1988 Constitution. Yet government-allied leaders in the chamber of deputies refused to abide by the order on the grounds that Article 15 of the Constitution grants Congress the prerogative to repeal mandates after all appeals are exhausted. A stalemate ensued between Congress and the Supreme Court that ultimately maintained the congressional seats of the remaining mensaleiros until late 2013.

Congress also began a campaign of institutional intimidation, tabling several legislative proposals that threatened to neuter ex post accountability institutions in Brazil. Constitutional amendment 37 aimed to limit the investigative power of the public prosecutor's office and amendment 33 proposed to subject constitutional decisions by the Supreme Court to higher vote thresholds and conditional approvals by Congress. An inter-branch standoff ensued.

June 2013's historic protests appeared to help resolve the stalemate. Subsequent to the protests, legislative threats disappeared, proving no more than parliamentary swaggering. In their stead, several promising pieces of legislation moved forward. In November 2013 Congress abrogated the constitutionally protected ‘secret vote’ on ethical violations, by passing constitutional amendment 43/2013, which determined whether to repeal a parliamentarian's seat. The secret vote on ethics violation had been notoriously abused as a means of exculpating malfeasance in Congress. It had come to symbolise the worst of Brazilian politics, a sort of pact of impunity. Furthermore, a constitutional amendment aiming to automatically strip a parliamentarian of his mandate in cases of administrative improbity passed the Senate in September 2013.Footnote 16 This measure was subsequently approved by a special committee in the Chamber of Deputies in February 2014, but has since stalled.

In the final analysis, it was not Congress that cast doubt on the outcome of the Mensalão, but rather the Supreme Court itself. Almost nine months after the trial, in September 2013, the court decided by just one vote to admit a category of appeals called embargos infringentes (infringing embargoes). The appeals permit defendants a new vote on criminal counts where at least four of the Supreme Court's 11 justices vote against a guilty verdict. Germane to the court's archaic internal regimen (from 1980), there was reason to believe that these embargoes contravened elements of newer laws on judicial procedure (Laws 8.038 from 1990 and 9.868 from 1999, specifically). As Justice Joaquim Barbosa was fond of saying throughout the trial, ‘justice delayed is justice denied’.

Yet just as citizens seemed to be losing hope in whether the Mensalão convictions could be transformed into hard sentences, the protagonist of the trial and president of the Supreme Court, Joaquim Barbosa, gave the order for sentences to be carried out on 15 November 2013. Emblematically, Barbosa chose the day of the Proclamation of the Brazilian Republic. The unprecedented spectacle of indicted politicians being escorted onto federal police jets and checking into prisons confirmed the successful prosecution of the Mensalão. Adding to the drama was the growing realisation that one of the indicted, a PT party member and former head of the Bank of Brazil, Henrique Pizzolato, had executed an escape plan worthy of a Hollywood production. Slipping over the Paraguayan border, Pizzolato fled to Argentina, Spain and finally Italy, where he was captured possessing his deceased brother's identity, large bank accounts and million dollar houses on the Spanish coast.

Despite allegations that the assets were compatible with his personal income, the actions of Pizzolato seemed to blow apart the carefully cultivated image that PT leaders such as Dirceu and José Genoíno, former president of the PT, had attempted to convey. When these politicians checked into their respective prisons, they did so with raised fists, symbolising the claim that they were ‘political prisoners’ who, while acquiescing to the decision of the justice system, were ultimately innocent and had no need to be ashamed. In contrast to the stoic defiance of PT leaders, Pizzolato had apparently been planning his escape since 2007. In effect, his criminal behaviour was a tacit admission of wrongdoing, an embarrassment to the party.

Pizzolato's flight from justice was not the only post-trial novelty. Convicted members of the PT, including Dirceu and Genoíno, began online fundraising to pay the hefty fines imposed as part of their sentences. Donations flooded in. The former treasurer of PT, Delúbio Soares, managed to raise more than R$ 600,000 (about US$ 280,000) in a single day. Surplus donations went to convicted comrades, until all fines of the core PT political cadre had been effectively paid off through crowd funding. Intimating that some of the funds might be laundered or otherwise illegal, Supreme Court Justice Gilmar Mendes appealed to the public prosecutor's office for an investigation into their provenance. Questioning the origin of funds appeared to be the right thing to do; funds used to defend members of the PT during the actual trial had been usurped from public money earmarked for financing political parties.Footnote 17

The infringing embargo appeals were ultimately heard in February 2014. Thanks to the introduction of two new justices, Luis Roberto Barroso and Teori Zavascki, eight convicted mensaleiros had their charges of criminal conspiracy reversed, which reduced their sentences. In March 2014, money-laundering convictions for two other former deputies were also withdrawn. While the infringing embargoes may raise questions about the need for reforms to the Brazilian justice system, they are legitimate appeals under the current system.

As of this article's final revision, most of the public officials involved in the Mensalão have already served one-sixth of their sentences, which under Brazilian law means they are legally entitled to petition for more moderate sentences, such as semi-open nightly incarceration (regime semiaberto). These more moderate sentences are based on clear criteria, such as good behaviour and work in prison. This point is worth emphasising; for better or for worse, real or potential adjustments to criminal sentences are not based on favours or the power of the accused, but rather on formal rules and procedures that regulate the right of appeal. This is what is referred to as a ‘progressive [as in “incremental”] appeals system’.Footnote 18 That is, after the sentenced complete one-sixth of their respective terms, the court commutes the sentence based on behavioural criteria. For this reason, some convicted criminals receive adjustments in their sentences while others do not (see the appendix for specific information regarding the nature of the crime, the range of sentences established in the criminal code, the sentences handed down, their final sentences, and the type of sentence each received).

For instance, the former presidential chief-of-staff, José Dirceu, was convicted to seven years and nine months of imprisonment in a semi-open regime (nightly incarceration), plus a fine of approximately R$ 1 million for the charge of active corruption (having coordinated the scheme). After spending one year and four months (one-sixth of his sentence) in semi-open regime, Dirceu became entitled to request that his sentence be commuted. Based on behavioural indicators, the Supreme Court accepted this appeal, which in turn permitted Dirceu to spend the remainder of his sentence in home confinement. The former PT treasurer, Delúbio Soares, benefited from an analogous procedure. In the case of the former president of the PT, José Genoíno, the court conceded to a petition for an alternative sentence because of Genoíno's severe health problems.

In contrast to the above sentences for politicians, private sector conspirators such as the publicist Marcos Valério and the banker Kátia Rabello received sentences of approximately 37 and 15 years of hard time. Yet the longer sentences of private sector accomplices can be explained by a broader set of crimes, most of which were applied numerous times, and the fact that the accused left behind much clearer evidence of their criminal involvement. Marcos Valério, for example, was convicted of active corruption, tax evasion, criminal conspiracy, money laundering and embezzlement, totalling more than 37 years of prison.

This caveat still does not dispel the question of whether Brazilian law promotes impunity for politicians. Many see the ultimate approval of the embargo infringentes appeals in February 2014 as an absurdity, giving a ‘second chance’ to defendants when seven of the court's 11 justices (64 per cent) voted for conviction. Still others are frustrated that strangers, friends and family paid the fines of prominent politicians. Not only is the legality questionable, they argue, but it also seems to nullify any attendant lesson of the penalty.

The question of Brazil's lax appeals system and penal code aside, perhaps the most disheartening aftermath of the Mensalão was Barbosa's premature departure from the court, made official in July 2014. Mandatory retirement was slated for 2024, but the Justice alleged that he was ‘tired’. Others cited constant threats as the key motivating factor. What is clear is that Barbosa's prospects in the court subsequent to the Mensalão did not appear felicitous. Following the retirement of several like-minded colleagues, including Justices Cezar Peluso and Carlos Ayres Britto, and facing less sympathetic newcomers and a court led by his nemesis, Ricardo Lewandowski, Barbosa simply found himself outflanked. This Justice's precocious retirement may yet serve to elevate and preserve his achievements in the collective consciousness, establishing an ideal, if not legal then moral legacy that will hang heavily over future courts.

Indeed, Barbosa's legacy may already have inspired judges such as Sergio Moro, who have zealously prosecuted those involved in the Petrolão scandal. Even Barbosa's nemesis and current president of the Supreme Court, Ricardo Lewandowski, acknowledges that recent trends among Brazil's courts constitute ‘a revolution’.Footnote 19 It is hard to see how any of this might have come to pass without the incredible precedents set by the Mensalão. Regardless of what might be said about the lenient penal code or appeal system, the Mensalão proved to be the harshest indictment and single largest tally of political corruption convictions in Brazilian history to date.

Explanations to Account for the Mensalão's Success

What can explain this departure with legacies of political impunity, where top power brokers from the chief executive's party were systematically investigated, tried, charged and sentenced by the very prosecutors and judges they appointed? This is especially puzzling for a presidential regime, where the difficulty of removing the chief executive means that presidents typically exercise strong influence over both their parties and the executive at large. Here, procedural justice and the action of other checks and balance institutions took its full course, humiliating and humbling powerful politicians.

Several aspects of the Mensalão were unquestionably unique, including the scope of the scandal, the composition of the court and the protagonism of Justice Joaquim Barbosa. Yet Barbosa's role should not be made out to be more than it was; the Mensalão was more than the trial, it was also the persistent, pre-trial, focus by investigators and prosecutors, which featured uncommon coordination and cooperation.

It hardly bears affirming that constant attention to the Mensalão, by the public, the media and Brazil's criminal justice system, had much to do with the case's success. Salience is key, because it triggers reputational concerns of those involved and gives transparency to advances or attempts to extinguish investigation or prosecution. But what can account for the incredible amount of attention the Mensalão received? It is this question to which the following discussion turns.

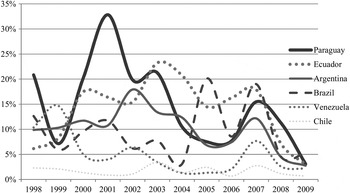

There is no debating the distinctiveness of the Mensalão for Brazilian citizens. Figure 1 shows public responses to the ‘most important problem’ question over a period of a decade in a sample of Latin American countries. The only point at which Brazilians distinguished corruption as the most important problem was in 2005 when the Mensalão scandal exploded into the news, and again in 2007 when court proceedings began. At these points, Brazilians were only surpassed by Ecuadoreans and Paraguayans in viewing corruption as their country's most important problem (refer to Figure 1).

Figure 1. Percentage of Respondents Viewing Corruption as the Country's Most Important Problem, South America

Corruption had always been viewed as a problem yet rarely stood in the way of impunity in the past. The Mensalão somehow altered the calculus, transfixing public attention. The following pages assess what made the Mensalão so distinct as to hold public attention for over half a decade, one of the key explanations for why the case received priority treatment within Brazil's legal system.

The PT's character reversal

From a historical-institutional perspective, one might venture that the incredible disconnect between the PT's traditional reputation for discipline, transparency and ethics, on the one hand, and the crime of the Mensalão, on the other, stoked curiosity and disbelief, leading to unrelenting attention.Footnote 20 The PT had historically been seen as a rare refuge of probity in a party system widely distrusted as opportunistic, if not venal. A poll undertaken in 1997 showed that only 4 per cent of electors saw the PT as the ‘most corrupt party’.Footnote 21 This number increased to 27 per cent in the wake of the Mensalão, when the same poll was conducted in 2006. What makes the PT's authorship of the Mensalão even harder to fathom is the fact that Lula had vigorously supported the strengthening of accountability institutions. As Matthew Taylor ventures, these institutions ‘achieved critical mass’ during the beginning of his first presidential term.Footnote 22 As a hypocritical rupture with this commitment, the Mensalão inspired disbelief, anger, blame-seeking, and in turn a maelstrom of attention from news media, the criminal justice system, and the Brazilian public more generally. This attention helped drive investigations and prosecutions forward.

A conspiracy from the Right

An alternative explanation, relying on an ideological rationale, posits that the Mensalão was not distinct at all, but rather pitted a left-leaning president against a relatively conservative media, Congress and criminal justice system, all out for blood. The goal of incriminating the PT drove each of these actors to unrelentingly pursue the case's successful prosecution.

Brazil's media has long been vilified by parts of the Left as a P-I-G, which stands for Partido de Imprensa Golpista (Party of a Pro-Coup Press). In this view, the P-I-G had always found the prospect of a PT government odious, especially because Lula had promised to make media reform a priority. The P-I-G was supposedly exploiting an opportunity to help incriminate and possibly expel the Workers’ Party from office.

This rationale, however, does not appear to be supported by extant empirical evidence. Citing several content analyses, Taylor Boas asserts that, ‘candidates of the left-wing Partido do Trabalhadores … including Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva … have received even-handed treatment in the 2000s.’Footnote 23 Content analyses by Eduardo Nunomura, among others, have found that coverage by the Folha de São Paulo, Brazil's largest daily by circulation and often considered centrist or centre-right, was comparably critical of Lula during the Mensalão as it was of Fernando Henrique Cardoso during lesser imbroglios.Footnote 24 Moreover, Folha cited members of the PT in the news nearly three times more than opposition party politicos, which may suggest that media outlets gave PT officials due opportunities to defend themselves. Even an analysis of ‘Jornal Nacional’, Globo's nightly television newscast, found inconclusive results on the question of bias against the PT.Footnote 25 It may be true that the media did not focus on the systemic roots of the Mensalão, but focused instead on the ‘moral’ aspects of the crime.Footnote 26 But that seems true of most media coverage; the shame of scandal sells better than analyses of how institutions misalign political incentives.

Rather than being a media witch-hunt, prodigious coverage of the Mensalão appears to be a testament to the scandal's institutional staying-power. Most congressional investigations in Brazil are quashed by the ruling coalition before they get started. As Alfred Montero notes, accountability in Brazil has often depended on ‘the right configuration of political forces in the legislature or the advent of embarrassing scandals that shock the system into reform’.Footnote 27 Yet attempts to suppress congressional investigations into the Mensalão came to naught. As investigation and prosecution continued unabated, the news machine kept churning. Nunomura notes that investigations kept leading to more and more ‘sub-scandals’,Footnote 28 which drove new lines of media production connected to the Mensalão and hence ever more coverage. In other words, the media covered the Mensalão not because of some conspiratorial agenda but primarily because the scandal, investigation and prosecution kept making news. The same is occurring with the Petrolão scandal; new revelations are seemingly spilled with each passing day, fuelling ever more media coverage.

As for the argument that a right-leaning justice system was hungering for PT blood, it is true that Lula had reformed elements of the justice system a year earlier, in 2004. This reform imposed onerous changes on the Ministry of Justice, the federal police and checks on the discretion of judges through the newly established National Council of Justice (Conselho Nacional de Justiça). From this perspective, the attention devoted to the Mensalão was as much ideological bias as it was retribution through a ‘flexing of muscles’ by the newly reformed criminal justice system.

Yet one must also take into account who runs this system. The Minister of Justice, who controls the federal police, is nominated by the president. The same is true for the head of the public prosecutor's office. Close to four-fifths of the Supreme Court was appointed by PT presidents. Why would the very officials appointed by the PT be driven by an ideological agenda against them? In sum, the criminal justice system before and after the Mensalão was not being run by the opposition, but rather by officials selected by the PT. In this light, a story of ideological antagonism by the criminal justice system is hardly compelling.

Finally, the promotion of Brazil's judges along their career paths occurs in a self-selected and hierarchical manner, which tends to protect them from ideological capture.Footnote 29 It is true that a minority of judges on Brazil's Supreme Court are associated with the political projects of certain presidents, but this observation should only strengthen the case against a potential PT bias in the court.

An egregious crime

A final ideational rationale may be able to account for why the Mensalão was so distinct as to transfix public attention for over half a decade. The idea here is that the nature of the crime explains the attention that drove Mensalão investigations and prosecutions forward.

Considered analytically, legislative vote-buying is a particularly egregious crime in a democracy because it subverts the representative process, the core raison d’être of the legislature, at the root. It is quite unlike the more commonplace forms of corruption, such as bribery, embezzlement, tax evasion, or misuses of office, public resources, or political finance.

Some have compared the Mensalão with other crimes perpetrated in Brazil. The Mensalão Mineiro is the clearest parallel. But this scandal clearly serves as a false equivalent; whereas the Mensalão Mineiro implicated former Partido da Social Democracia Brasileira (PSDB) Governor of Minas Gerais, Eduardo Azevedo, for misusing public resources and illegal campaign contributions, these were alleged electoral crimes in one state jurisdiction (Minas Gerais). The PT's Mensalão, by contrast, was a national legislative vote-buying scheme that made vote-buying with public money ‘business as usual’, a categorically different crime.

From a legal and normative standpoint, both legislative vote-buying and electoral vote-buying (purchasing the votes of citizens) are serious political crimes. Yet the latter is typically confined to individual voting districts or parts thereof. What is distinctive about legislative vote-buying is that it corrupts democracy at the aggregate, where decisions are taken. It erodes confidence not only in the legislature, but also within the highest levels of government. By outright purchasing party votes in a coalition, the operators of the Mensalão effectively negated the voting preferences of citizens, exposed papier-mâché party-platforms, and bought public policy to suit their own designs.

The gravity of this crime, and the ability of the public to grasp its meaning, partly explain why so few legislative vote-buying scandals have come to light around the world; they either occur rarely, or politicians collude to keep them secret. It also helps explain why they tend not to go away quietly.

The ubiquity of high-level impunity

‘Equality before the law’ is an oft-touted but seldom realised ideal. Implicated high-level officials frequently need not appear before the law; resignations or wilful blindness ensure that investigations do not move forward and pardons spare officials from humiliating trials. When high officials do receive sentences, they are usually unequal to those suffered by common citizens or lower-ranking public servants.

The tendency of the political elite to pardon those of their own ilk is as commonplace as it is institutionalised; as Zachary Elkins shows, 89 per cent of all constitutions enumerate a power of executive pardon.Footnote 30 The United States is a classic perpetrator of high-level impunity. From Watergate to the Iran Contra Scandal and the commuted sentence of Lewis ‘Scooter’ Libby, US presidents have used and abused the power of pardon.

While pardons do not obstruct legal processes, although they may end them, they instil civic cynicism and waste taxpayer money by rendering investigations and prosecutions redundant. Pardons are not just limited to the United States; they are international. Former president of France, Jacques Chirac (1995–2007), received an indictment in 2011 for illicit enrichment as mayor of Paris from 1977 to 1995.Footnote 31 The courts suspended the politician's prison sentence due to health concerns and by virtue of Chirac's status as a former president.

Pardons are one form of impunity. The other is a system that simply cannot arrive at guilty verdicts, either because it lacks coordination, independence or the procedural rules of the game are stacked in favour of well-resourced individuals. The only credible allegations of legislative vote-buying that have arisen over the last decade, in the Argentine Senate under former president Fernando de la Rúa (1999–2001) and in India's Parliament to secure a United States-India nuclear deal in 2008, resulted in no witnesses stepping forward in the former and a botched investigation in the latter.

While Brazil's courts generally do not lack for independence,Footnote 32 protections and procedures have contributed greatly to impunity.Footnote 33 Resourceful defendants can benefit from generous procedural privileges such as easily dispensed writs of habeas corpus and multiple opportunities to appeal. Court backlogs mean that most officials have simply run out the clock, employing delaying tactics, interlocutory and final appeals of regular and constitutional varieties, to invoke the statute of limitations.Footnote 34 Matthew Taylor calculates that of 130 cases of political improbity filed with the Supreme Court from 1988 to 2007, only six were heard and none resulted in a conviction.Footnote 35

Despite changes, Brazil's rules continue to promote impunity. The Mensalão Mineiro is a case-in-point. Brazil's rules of special standing (foro privilegiado) stipulate that officials who resign from their posts are no longer subject to being tried by the country's highest courts. This rule is applied unevenly, with the Mensalão being one case in which it was partly ignored. Critics impugned the Supreme Court's decision not to try a former governor of Minas Gerais from the PSDB, a rival of the PT. The defendant, Eduardo Azevedo, resigned as a federal senator in 2014 in order to disqualify himself from special standing and therewith judgment by the Supreme Court. Azevedo's case, first revealed in 1998, was nearly ready to go to trial, but now returns to a lower court and processing starts anew, implying that justice might be delayed. Even if eventually convicted, parole is nearly guaranteed, and university-educated prisoners receive special treatment. In short, the widely held thesis that Brazil's protections for the accused have overcompensated for the harsh treatment individuals suffered under the rules of the last dictatorship (1964–85) appears warranted.

Yet although systems around the world may facilitate impunity among high-level officials, the successful prosecution of high-level officials is becoming more common. The Mensalão represents one among several recent cases that signal a possible movement towards greater high-level accountability. In Israel, former Prime Minister, Ehud Olmert (2006–09), was recently convicted for corruption and sentenced to six years in jail in addition to sizable fines. In Peru, President Alberto Fujimori (1990–2000) was condemned to eight years behind bars, his fourth sentence. Fujimori will likely spend the rest of his life in prison. High-level politicians in Hong Kong and Indonesia have also suffered precedent-breaking convictions over the past years.Footnote 36 In none of these cases, however, nor in cases where legislative vote-buying has been alleged, were the convicted brought to justice when the political party associated with their office held power. This anomaly is truly what makes the Mensalão so distinctive, and undeniably suggests that Brazil's accountability institutions are moving forward.

Legal and Political Advances and Implications of the Mensalão trial

Having examined the Mensalão from scandal to sentencing, provided alternative explanations to account for its relative successes and discussed the case within the context of high-level impunity, the remaining sections analyse the advances and implications of the Mensalão in legal and political terms. The Mensalão investigation illustrated new approaches towards investigation, prosecution, conducting trials and sentencing that may portend lasting impacts.

In terms of trials, one only need contrast the Mensalão with the 1994 trial of former president Fernando Collor de Mello to understand how justice in Brazil has departed from the past. During the ‘Collorgate’ trial, legal experts and the press questioned the public prosecutor's office's investigations; key evidence gathered by the federal police was thrown out on technical grounds and, critically, court proceedings were hidden from the public eye (televised proceedings became law in 2002). In other words, informational asymmetries, coordination problems and possible political meddling tainted the trial. Although four of the seven accused did receive prison sentences, a judgment of ‘insufficient evidence’ spared the president from charges of grand corruption.

While unrelenting public attention, abetted by televised proceedings and salient procedural transparency, undeniably influenced the Mensalão's outcome, the structure of several legal decisions probably made the difference between a conviction and an acquittal.

A first jurisprudential advance has to do with how trials of high-level corruption are conducted. According to the constitution, only high officials enjoy the privilege of being tried by the Supreme Court (STF). The same is not true of bank managers and publicists, who were also implicated as central figures in the Mensalão. The STF nevertheless decided to judge everyone together; the precedent had been set during President Collor's 1992–94 trial and the Mensalão proceedings leveraged a similar logic. A second distinctive decision was the strategy of breaking up sets of criminal charges, corruption, conspiracy, money laundering, and misuse of public funds, among others, into monolithic voting blocks, as opposed to judging each defendant on each charge in turn. This innovation saved considerable time, much to the chagrin of the defence counsel, whose strategies included delaying the trial as long as possible in order to invoke the statute of limitations. Third, and most importantly, the majority decision parted waters from traditional legal treatments of political corruption in Brazil by ostensibly embracing the German jurist Claus Roxin's ‘dominion of the fact theory’ (domínio do fato).Footnote 37 Roughly stated, the theory stipulates the crime of responsibility in a hierarchical fashion and tends to be more amenable to indirect evidence. In this sense, a majority of the STF's judges deemed the burden and convergence of circumstantial evidence, as opposed to damning direct evidence, as sufficient to convict. In other words, corruption was inferred without a smoking gun.

This decision not only marks an important break with the type of legal doctrine that spared former President Collor from conviction. It may portend a change in how officials and politicians look at real or potential corruption charges. As Matthew Taylor has noted,Footnote 38 legislators who vote to indict fellow legislators do so at the risk of their personal and political well-being. The Mensalão lowered the bar for establishing criminal charges of corruption, which may in turn encourage greater whistleblowing.

In a different sense, whistleblowing, in response to plea bargains, is quickly becoming a new hallmark of corruption scandals in Brazil. The Mensalão appears to have played a role in two ways. First, the Mensalão's harsh sentencing of private sector intermediaries, such as Marcos Valério (37 years in prison), Ramon Hollerbach (27 years in prison) and Kátia Rabello (14 years in prison) appears to have had an important demonstration effect, compelling plea bargains. Top executives such as Paulo Roberto Costa, the former director of logistics at Petrobrás, have implicated scores of officials thanks to the offer of leniency in exchange for implicating additional conspirators. The harshness of the Mensalão sent a precedent in and of itself. As of this writing, the owner of Brazil and Latin America's largest engineering and contracting company, Marcelo Odebrecht, has been imprisoned for nearly four months, an occurrence that is hardly conceivable anywhere in Latin America let alone in pre-Mensalão Brazil. Second, and perhaps even more important than the harshness of the Mensalão, is the passage of key legislation. The Anti-Corruption Law (12.846) and Criminal Organisations Law (12.850), both enacted in 2013, seem to have forever transformed Brazil's landscape of elite impunity. It is these measures that have contributed towards harsher prospective sentences and the now ubiquitous use of plea bargaining. Even those critical of PT political leadership ought to acknowledge the role presidents have played in helping to strengthen the legal fabric of accountability and transparency, let alone the independence of Brazil's institutions. It seems clear that in the wake of the Mensalão, PT leaders have to some extent sought redemption through filling gaps in Brazil's legal and institutional infrastructure.

The Mensalão and institutional advances

Where Brazil remains weakest is in terms of ex post accountability. Indeed, retributive justice is arguably the single weakest link in the institutional consolidation of new democracies. It is not just the will to prosecute high-level officials that is often missing, but also the capacity. Whereas executive-legislative relations are regular, frequent and practised, the cogs and wheels of investigative and prosecutorial institutions overlap and diverge; their interactions are episodic and less frequent. The coordination of independent investigation and prosecution institutions tends to be where cases fall apart; political interference, and dilemmas born of collective action or coordination roadblocks prevent justice from being done. In short, coordination is more difficult for the pre-trial justice system.

As Taylor and Buranelli observed in 2007, Brazil's ex post accountability deficit does not necessarily have to do with weak institutions, but rather with ineffective coordination.Footnote 39 It is certainly clear that the Supreme Court does not lack independence; it has continuously signalled the limits of executive power.Footnote 40 For instance, whereas the United States Supreme Court has declared the unconstitutionality of approximately 165 federal laws, its Brazilian counterpart has ruled that 200 federal laws be altered on constitutional grounds, and this is just within the last 25 years. Most recently, the Supreme Court voted down a proposal to de-fang the public prosecutor's office by stripping it of its investigatory powers.Footnote 41

Taking Taylor and Buranelli's point into consideration, it is historically accurate to affirm that the investigatory efforts of the federal police have rarely synchronised with those of the federal public prosecutor's office because of institutional overlap, competition and different approaches to enforcement. These problems, as well as divergent agency cultures, are no rarity in executive politics. The Central Intelligence Agency, the Federal Bureau of Investigation, local police and even the United States Marshals frequently get policy wrong due to these very factors. The difference is that US domestic security agencies have learned, over many iterations, during many years, and through the development of institutional mechanisms, to coordinate and get it right most of the time.Footnote 42 Part of the Mensalão's significance resides in successful coordination, which is compelling evidence of institutional learning in one of the most challenging policy domains.

The Mensalão and advances in transparency and information flows

While greater institutional coordination can be explained by Brazil's growing maturity, a process of learning and incremental reform, it also has to do with improved information flows. These flows have increased exponentially in the wake of the Mensalão. High levels of procedural transparency helped feed news media production on the Mensalão, including real-time procedural transparency through televised coverage of Congress and the Supreme Court. Nightly news on the Mensalão fed public demand for further information and signalled to the institutions involved that coordination failures would not be accepted.

Brazil's media kept a vigilant eye on the scandal. Key publications, especially the magazine Veja and the newspaper Folha de São Paulo, are often credited with breaking scandals. But as Manuel Balán's research suggests, it is divisions and internecine competition among and within Brazil's many parties that are responsible for the targeted leaks that result in news exposés.Footnote 43 This dynamic is clearly what kept the Mensalão from being killed in Congress. President Lula's fragmented majority coalition voted to keep inquiry committees alive, which helped guarantee the involvement of the public prosecutor's office and the federal police in the inquiry process. Had a single-party majority been in power, this dynamic would have likely never occurred.

In this sense, Brazil's political system creates strong incentives for information flows. Surrounded by demanding allies, presidents are required to negotiate in public with their coalition partners. Vigorous intra- and inter-party competition helps drag malfeasance into the light, as it did with the Mensalão. Brazil's fragmented coalition presidentialism has had the unanticipated effect of promoting greater procedural transparency. It is because of the size and diversity of cabinets, as many as seven parties and 40 ministerial-type positions, that transparency has become so important to Brazil's presidents.Footnote 44 In short, coalition parties need to be monitored because they do not share the president's priorities, and frequently demonstrate disregard for administrative probity or due process.

Cognisant of the rent-seeking that occurs within coalition-held ministries, Brazilian presidents have deployed various strategies to augment information flows.Footnote 45 Rousseff's first term saw a wave of transparency reforms. In addition to a new freedom of information law (12.527/11), Congress also enacted a Truth and Reconciliation Commission to deal with abuses committed under military rule (1964–85), an online open-data portal and the government implemented a modernisation of Brazil's award-winning real-time budgetary transparency websites. Rousseff's government made these innovations difficult for ancien régime elements to oppose by signing-up Brazil to assume the co-chair of the 65-country (and growing) Open Government Partnership (OGP), an international initiative in which countries pledge to augment transparency, accountability and participation in government.Footnote 46

The above measures are not mere window-dressing. In terms of legal strength, the new freedom of information (FOI) law ranks among the 20 most rigorous in the world, and a recent evaluation of the federal government's responsiveness to freedom of information requests (in all three powers) resulted in over 80 per cent compliance, a figure that bests the federal governments of countries such as Canada and the United States, both of which have had FOI measures for decades.Footnote 47 In sum, Brazil's transparency infrastructure has grown substantially over the last few decades, facilitating informational flows that can help the country deepen democratic and institutional advances. This new commitment may yet develop into a new hallmark of the country's soft power and regional leadership.

Cleaning up representation

In the wake of the Mensalão scandal and trial, Brazil's representative system experienced sweeping changes. As alluded to in the first section, perhaps the most important advance is a ‘clean slate law’ (Ficha Limpa). Brought to Congress through a direct democratic process, the Ficha Limpa serves as an ethical barrier to political electability by prohibiting those convicted of a crime (on appeal, in an appeals court) from running for office. In the October 2012 municipal elections, this law barred over 850 candidates from standing. While the clean slate law has set up a critical precondition for electability, it does not appear to have dramatically changed the quality of representatives so far. In mid-2013, four out of every ten congressmen was being investigated on criminal charges.Footnote 48

Positively, however, late 2013 saw the passage of a constitutional amendment to eliminate secret voting in Congress. Advocates of this measure sought to ensure that votes taken to expel parliamentarians on grounds of ethical violations did not result in impunity, as was the historical tendency. On this issue, Facebook campaigns proliferated and the non-governmental organisation Avaaz presented a petition to Congress containing 700,000 signatures.Footnote 49 As evinced by these initiatives and 2013 protests, social accountability movements are on the rise. Such movements were instrumental in quashing PT efforts to diminish the independence of regulatory agencies, and stonewalling a proposal to regulate media production through the creation of ‘media councils’ during both of Lula's terms and the first year of the Rousseff presidency.

While an arsenal of accountability and transparency mechanisms is becoming de rigueur for any government, it is no coincidence that this transparency and accountability offensive has emerged during and after the Mensalão trial. As in other countries, major scandals tend to serve as a catalyst of institutional innovation and reform. While it is empirically difficult to establish causal links tracing scandals to reforms, the convergence of transparency reforms and ex ante accountability reforms during the prosecution and aftermath of the Mensalão has obvious correlative value.

Conclusion

As the last section illustrated, new commitments to transparency and accountability in the wake of the Mensalão have helped strengthen ex ante accountability in Brazil. Ex post accountability, the weakest link in any accountability system, has demonstrated vigour with new legislation on anti-corruption, criminal organisations and a new judicial emphasis on prioritising corruption cases. The legal advances of the Mensalão are forcing Brazilian citizens to question the frequent assumption that corruption investigations ‘end in pizza’, with wealth and power always finding a jeitinho or ‘way’ around the law.

In this sense, if not a great leap forward, the Mensalão was a giant step forward in the right direction for a country that began its democratic journey a relatively short time ago. It is a compelling indicator that the country is learning to put its national motto, ‘order and progress’, into practice under the aegis of democracy.

Above all, the Mensalão shows the capacity of Brazil's legal system to remain independent in spite of political dynamics that overwhelmingly appeared to favour impunity. The major decision-makers in the Mensalão trial were appointed by the party in power, including the heads of the federal public prosecutor's office, the federal police and close to 80 per cent of the Supreme Court. In the final analysis, former President Lula's entreaties to at least five Supreme Court justices fell on deaf ears. Twenty-eight defendants received jail sentences or heavy fines, including one of Lula's closest political confidants, his former chief-of-staff, José Dirceu. At the current juncture, it is important to ask whether the independence of Brazil's institutions can be explained by a growing respect towards the rule of law by Brazil's presidents, and concomitant non-interference, or the increasingly insulated independence of Brazil's institutions. The answer appears to be both, further evidence that Brazil's ‘web’ of accountability is quickly maturing.

As of the revising of this article, the Petrolão scandal continues to rage. This case, that has already sent 15 people to prison, including two PT leaders, may yet prove that the Mensalão was indeed the beginning of a trend towards a stronger rule of law in Brazil. It is hard to imagine that these promising developments would have occurred absent the enormous influence of the Mensalão. For the time being, however, the Mensalão remains an outlier within the country's canon of justice. Yet here we have argued that this outlier is emblematic and formative of Brazilian democratic development on three levels. First, the Mensalão made new inroads in strengthening the rule of law, and perhaps no outcome will prove more consequential than the legitimisation of circumstantial and convergent evidence as proof of culpability in political corruption cases. Second, the adept prosecution of mensaleiros is indicative of institutional learning and a growing capacity for inter-agency coordination. Third, the information flows surrounding the investigation, prosecution and trial of the Mensalão puts into full view growing transparency and media independence in Brazil.

Further research on this case and others should focus on the prevalence of legislative vote-buying. Is it a hidden, business-as-usual occurrence in Brazil and other countries? Several other high-level cases of legislative vote-buying have been alleged in Brazil over the years. Clearly, legislative fragmentation and divided governments provide a compelling rationale to suspect cash payoffs in return for legislative support. If cash is part of the governing equation, where does the money come from? Other research needs to analyse the new influence of the anti-corruption and criminal organisations laws (12.846 and 12.850) approved in 2013. In providing protection and rewards for pointing fingers, these laws may have a critical effect on disrupting a long legacy of conspiratorial and ‘pacted’ corruption in Brazil. The Mensalão suggests that Brazil has crossed a political threshold of sorts, and the country's political landscape is clearly experiencing a critical moment of institutional fluidity. Political development is non-linear, and institutional developments, as exemplified by the Mensalão, suggest the need to cautiously qualify, if not re-evaluate, our political generalisations about democracy and the rule of law.

Appendix

Table 1. Individuals Convicted in the Mensalão: Sentences, Punishment, and Fines